4 Case Studies in Fraud: Social Media and Identity Theft

Does over-sharing leave you open to the risk of identity theft.

Generally speaking, social media is a pretty nifty tool for keeping in touch. Platforms including Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and LinkedIn offer us a thousand different ways in which we can remain plugged in at all times.

However, our seemingly endless capacity for sharing, swiping, liking, and retweeting has some negative ramifications, not the least of which is that it opens us up as targets for identity theft.

Identity Theft Over the Years

Identity theft isn’t a new criminal activity; in fact, it’s been around for years. What’s new is the method criminals are using to part people from their sensitive information.

Considering how long identity theft has been a consumer threat, it’s unlikely that we’ll be rid of this inconvenience any time soon.

Living Our Lives Online

The police have been using fake social media accounts in order to conduct surveillance and investigations for years. If the police have gotten so good at it, just imagine how skilled the fraudsters must be who rely on stealing social media users’ identities for a living.

People are often surprised at how simple it is for fraudsters to commit identity theft via social media. However, we seem to forget just how much personal information goes onto social media – our names, location, contact info, and personal details – all of this is more than enough for a skilled fraudster to commit identity theft.

In many cases, a fraudster might not even need any personal information at all.

Case Study #1: The Many Sarah Palins

Former Alaska governor Sarah Palin is no stranger to controversy, nor to impostor Twitter accounts. Back in 2011, Palin’s official Twitter account at the time, AKGovSarahPalin (now @SarahPalinUSA ), found itself increasingly lost in a sea of fake accounts.

In one particularly notable incident, a Palin impersonator tweeted out an open invite to Sarah Palin’s family home for a barbecue. As a result, Palin’s security staff had to be dispatched to her Alaska residence to deter would-be partygoers.

This phenomenon is not limited only to Sarah Palin. Many public figures and politicians, particularly controversial ones like the 2016 presidential candidate Donald Trump, have a host of fake accounts assuming their identity.

Case Study #2: Dr. Jubal Yennie

As demonstrated by the above incident, it doesn’t take much information to impersonate someone via social media. In the case of Dr. Jubal Yennie, all it took was a name and a photo.

In 2013, 18-year-old Ira Trey Quesenberry III, a student of the Sullivan County School District in Sullivan County, Tennessee, created a fake Twitter account using the name and likeness of the district superintendent, Dr. Yennie.

After Quesenberry sent out a series of inappropriate tweets using the account, the real Dr. Yennie contacted the police, who arrested the student for identity theft.

Case Study #3: Facebook Security Scam

While the first two examples were intended as (relatively) harmless pranks, this next instance of social media fraud was specifically designed to separate social media users from their money.

In 2012, a scam involving Facebook developed as an attempt to use social media to steal financial information from users.

Hackers hijacked users’ accounts, impersonating Facebook security. These accounts would then send fake messages to other users, warning them that their account was about to be disabled and instructing the users to click on a link to verify their account. The users would be directed to a false Facebook page that asked them to enter their login info, as well as their credit card information to secure their account.

Case Study #4: Desperate Friends and Family

Another scam circulated on Facebook over the last few years bears some resemblance to more classic scams such as the “Nigerian prince” mail scam, but is designed to be more believable and hit much closer to home.

In this case, a fraudster hacked a user’s Facebook profile, then message one of the user’s friends with something along the lines of:

“Help! I’m traveling outside the country right now, but my bag was stolen, along with all my cash, my phone, and my passport. I’m stranded somewhere in South America. Please, please wire me $500 so I can get home!”

Family members, understandably not wanting to leave their loved ones stranded abroad, have obliged, unwittingly wiring the money to a con artist.

Simple phishing software or malware can swipe users’ account information without their having ever known that they were targeted, thus leaving all of the user’s friends and family vulnerable to such attacks.

How to Defend Against Social Media Fraud

For celebrities, politicians, CEOs, and other well-known individuals, it can be much more difficult to defend against social media impersonators, owing simply to the individual’s notoriety. However, for your everyday user, there are steps that we can take to help prevent this form of fraud.

- Make use of any security settings offered by social media platforms. Examples of these include privacy settings, captcha puzzles, and warning pages informing you that you are being redirected offsite.

- Do not share login info, not even with people you trust. Close friends and family might still accidentally make you vulnerable if they are using your account.

- Be wary of what information you share. Keep your personal info under lock and key, and never give out highly sensitive information like your social security number or driver’s license number.

- Do not reuse passwords. Have a unique password for every account you hold.

- Consider changing inessential info. You don’t have to put your real birthday on Facebook.

- Only accept friend requests from people who seem familiar.

Antivirus software, malware blockers, and firewalls can only do so much. In the end, your discretion is your best line of defense against identity fraud.

You might also enjoy a great Motivational Speaker Video for social media safety tips

Jessica Velasco

Bachelor Finale Joey Graziadei gets Engaged In the highly anticipated Bachelor finale, tensions ran high as Joey had to choose who would get the fi…

Mike Tyson and Jake Paul Fight is Streaming on Netflix

Dodgers’ shohei ohtani reveals he is married, subscribe to the skinny.

The Rise of Mobile Betting Apps in NBA: Convenience and Accessibility

Strategies for building strong and mutually beneficial vendor relationships, happy april fools day: how to avoid getting tricked online, bachelor finale joey graziadei gets engaged, choosing the right case management software: considerations for law firms, adapting to the business landscape: exploring ai learning, construction, engineering, and home improvements, how and why facial recognition technology is safe, the best sports streaming services in the us.

Exploring the determinants of victimization and fear of online identity theft: an empirical study

- Original Article

- Published: 21 July 2022

- Volume 36 , pages 472–497, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Inês Guedes ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4804-9394 1 ,

- Margarida Martins 1 &

- Carla Sofia Cardoso 1

5607 Accesses

8 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The present study aims at understanding what factors contribute to the explanation of online identity theft (OIT) victimization and fear, using the Routine Activity Theory (RAT). Additionally, it tries to uncover the influence of factors such as sociodemographic variables, offline fear of crime, and computer perception skills. Data for the present study were collected from a self-reported online survey administered to a sample of university students and staff ( N = 832, 66% female). Concerning the OIT victimization, binary logistic regression analysis showed that those who do not used credit card had lower odds of becoming an OIT victim, and those who reported visiting risky contents presented higher odds of becoming an OIT victim. Moreover, males were less likely than females of being an OIT victim. In turn, fear of OIT was explained by socioeconomic status (negatively associated), education (positively associated) and by fear of crime in general (positively associated). In addition, subjects who reported more online interaction with strangers were less fearful, and those reported more avoiding behaviors reported higher levels of fear of OIT. Finally, subjects with higher computer skills are less fearful. These results will be discussed in the line of routine activities approach and implications for online preventive behaviors will be outlined.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Online Behaviour and Victimization Study: The Development of an Experimental Research Instrument for Measuring and Explaining Online Behaviour and Cybercrime Victimization

Examining cybercrime victimisation among Turkish women using routine activity theory

Mine Özaşçılar, Can Çalıcı & Zarina Vakhitova

Routine Activities

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The Internet provides unique affordances for criminal activities, especially due to the ease of information dissemination and anonymity of perpetrators. Furthermore, it extends traditional crimes (such as fraud or identity theft) to online offenses or create new types of criminal activity (e.g., malware infection). One of the crimes that can be considered an extension from traditional offenses is the online identity theft (OIT). OIT is considered one of the fastest growing crimes (Holt and Turner 2012 ; Golladay and Holtfreter 2017 ), resulting in relevant financial losses to victims. Knowing what factors might increase the risks of online victimization in general and OIT in particular is crucial. Although there is not one widely accepted definition of identity theft due to its complexity, it can be conceptualized as the “unlawful use of another’s personal identifying information” (Bellah 2001 , p. 222) such as accessing existing credit cards or bank accounts without authorization. Similarly, Koops and Leenes ( 2006 ) define identity theft as the unlawful acquisition and misuse of another individual’s personal information for criminal purposes. Therefore, the information that is obtained by the offender is acquired without the owner’s consent through illegal means. Researchers have been trying to established the factors that affect the likelihood of victimization of OIT. Among the criminological theories that have been used to explain this type of online victimization, Routine Activity Theory (RAT) is one of the most empirically tested (Cohen and Felson 1979 ; Reyns 2013 ; Reyns and Henson 2015 ; Reyns 2015 ; Bossler and Holt 2009 ). Moreover, while the research related to fear of crime in general is vast, the empirical studies aimed at understanding the fear of cybercrime are scarce, especially the fear of OIT. According to the 2019 Special Eurobarometer focusing on the European’s attitudes towards cyber security, although 92% did not report being a victim of identity theft in the last three years, at least two thirds of the sample reported to feel concerned about suffering a victimization of bank card or online banking fraud (67%) and of identity theft (66%). When comparing to the victimization of online crime or even to the fear of general crime, little is known about the online determinants of fear of identity theft.

The present study has two main objectives, namely to analyze the factors that increase (i) the risk of victimization of online identity theft and (ii) the fear and perceived risk of online identity theft. Concretely, the first objective aims at understanding what factors contribute to the explanation of online identity theft victimization , namely the exposure to potential offenders, target suitability and guardianship in the online context. Additionally, it tries to uncover the influence of factors such as sociodemographic variables and computer perception skills. Second, in order to understand what factors are related to fear and perceived risk of online identity theft , the present work will also test the influence of core dimensions of RAT, sociodemographic variables, previous victimization and general fear in those dependent variables.

Concerning the structure through which the present article will be developed, firstly the main crucial concepts and theories (e.g., online identity theft, RAT) will be outlined, followed by the empirical findings on the (i) relationship between RAT, individual variables and victimization of online identity theft and on the (ii) relationship between RAT, individual variables and fear of online identity theft. Next, the methodology of the present study will be described in detail. Finally, the results will be presented and discussed, including the implications of the present study.

- Online identity theft

Identity theft is a term used to classify numerous offenses including fraudulent use of personal information for criminal purposes without individuals’ consent (Reyns 2013 ). Harrell ( 2015 , p. 2) defines identity theft as the “unauthorized use or attempted use of an existing account (such as credit/debit card, savings, telephone, online), the unauthorized use or attempted use of personal information to open a new account or misuse of personal information for a fraudulent purpose such as providing false information to law enforcement”. Accordingly, Copes and Vieraitis ( 2012 ) state that identity theft includes the misuse of another individual’s personal information to commit fraud. Identity theft may or may not be committed through technological and informatic means (Wang et al. 2006 ). Online or cyber identity theft involves the online misappropriation of identity tokens such as email addresses, passwords to access online banking or web-pages (Roberts et al. 2013 ). In the present paper, we define OIT as the illicit and improperly use, via internet, of the personal and financial data which was obtained without prior consent and knowledge by the cyber-criminal. In order to perpetrate this crime, offenders usually employ a mix of Information and Communication Technologies and social engineering, using methods such as hacking, phishing and pharming. Phishing involves attempts to mislead individuals into revealing sensitive information by posing as a legitimate entity such as banks. Hacking is an unauthorized access which may be way of unto itself or for malicious purposes such as spreading malware. Pharming occurs when, through the use of a virus or a similar technique, individual’s browser is hijacked without their knowledge. Therefore, when targets type a legitimate website into the address bar of their browser, the virus will be redirected them to a fake site. In addition to these types of methods, research have been analyzing the relationship between data breaches and identity theft (e.g., Garrison and Ncube 2011 ; Burnes et al. 2020 ). For instance, Tatham ( 2018 ) observed that those who have been impacted by a database breach were 31.7% more likely to experience identity fraud compared to 2.8% of persons not alerted of a data breach. This result can be explained by the fact that the information obtained in a database breach is generally sold online, containing personally identifiable information that can be used to commit identity theft crimes. Therefore, in spite of the relevance of individual online activities, data breaches that target retailers or government entities, for instance, may also increase the risk of online identity theft.

Identity theft is considered one of the most feared, fastest-growing crimes and a public health problem (Burnes et al. 2020 ). In fact, Harrel and Langton ( 2013 ) estimated that the average loss experienced by victims of identity theft was $2183 in 2012. Later, an estimate made by Javelin Strategy and Research showed that the costs of identity theft were near $16 billion (Piquero 2018 ). Besides the financial losses, it has also been observed that, on average, victims spend at least 15–30 h (although it might take several years) solving financial problems related to identity theft. Recently, Golladay and Holtfreter ( 2017 ) analyzed the nonmonetary losses experienced by victims of identity theft through a survey where 3709 individuals reported experiencing some form of identity theft in the past 12 months. The authors found that victims of this crime, as with other forms such as bullying and violence, suffered relevant emotional and physical symptoms. Moreover, that the distress involved in recovering from identity theft could be conceived as a stressor resulting in negative emotions such as depression and anxiety. These results have been consistently reported by other investigations (e.g., Reyns and Randa 2017 ; Li et al. 2019 ; Harrell 2019 ) that found diverse emotional problems such as anxiety, irritation and distress following victimization of (online) identity theft. As we have been seen an increasing in the numbers of victims over the years (Li et al. 2019 ), as well as a set of empirically demonstrated harmful financial and emotional consequences, studying why someone is more prone to be victimized of online identity theft is fundamental. Moreover, it is crucial to understand if individuals fear this type of crime and what are the factors that explain the higher levels of fear of online identity theft. The Routine Activity Theory (or RAT) may help to understand what are the behaviors related to both victimization and fear of OIT.

Routine activity theory

In 1979, Cohen and Felson argued that “structural changes in routine activity patterns can influence crime rates by affecting the convergence in space and time of three minimal elements of direct-contact predatory violations: (1) motivated offenders, (2) suitable targets, and (3) the absence of capable guardians against a violation” (p. 589). Therefore, the RAT was a perspective developed to account for offenses and victimization in the physical world. In the context of cybercrime, authors such as Yar ( 2005 ) and Leukfeldt and Yar ( 2016 ) have been debated the applicability of this framework. In fact, the requirement of offenders and victims converging in time and space for a crime to happen presents a problem when applying the theory to cybercrimes. Gabrowsky ( 2001 ), opposing to ‘transformationists’ like Capeller ( 2001 ) argued that RAT could be applied to crimes in cyberspace since it was just a case of “new wine in old bottles”. In the same direction, Eck and Clark ( 2003 ) suggested that this framework can be useful to explain these types of online crimes since the target and the offender are part of the same geographically dispersed network, and therefore the offender is able to reach the target through network. In accordance, Reyns et al. ( 2011 ) argued that instead of a real-time convergence of victims and offenders within networks, the temporal overlap between them may be lagged for either a short time or a longer period. Therefore, according to RAT, it is expected that online activities—such as banking, shopping, instant messaging or downloading media, might be associated with higher levels of victimization. Moreover, that greater levels of security measures—installing antivirus software, filtering spam email or routinely changing passwords—might decrease opportunities for offenders to access personal information.

Although the RAT has been tested to explain different online forms of victimization such as phishing, hacking, interpersonal violence, malware infection or internet fraud (e.g., Choi 2008 ; Holt and Bossler 2009 ; Marcum et al. 2010 ; Raising et al. 2009 ), few studies have empirically examined OIT victimization from a routine activities’ perspective (e.g., Reyns 2013 ; Reyns and Henson 2015 ; Burnes et al. 2020 ). Furthermore, most studies have not operationalized all of the core dimensions of the theory (i.e. exposure to motivated offenders, target suitability and capable guardianship). Departing from the RAT, and including as well individual variables, we now review the main determinants of victimization and fear of online identity theft.

Determinants of victimization of online crime

Rat core dimensions.

The exposure to risky situations and proximity to offenders (online exposure) is usually conceptualized from the victim’s perspective (Reyns and Henson 2015 ), and have been operationalized through different ways (e.g., ‘the amount of time spent on the internet’ or ‘the amount of time doing specific activities’ Ngo and Paternoster 2011 ; Reyns 2013 ). The results of the studies that explore the relationship between exposure and online victimization are mixed. For instance, Holt and Bossler ( 2013 ) found that internet usage (measured through number of hours per week) did not predict the likelihood of malware infection victimization. Furthermore, in a recent study, Holt et al. ( 2020 ) observed that time spent on specific online activities, such as downloading files and visiting dating websites consistently increased the risk of victimization of malware software infections. This result is consistent with the research employed by Alshalan ( 2006 ) who found that risk exposure (measured through the frequency of using the Internet and duration) was a determinant of victimization of computer virus and cyber-crime. A study by Pratt et al. ( 2010 ) observed that making a purchase online from a website doubled the likelihood of being targeted for online consumer fraud. In turn, Ngo and Paternoster ( 2011 ) found that the number of hours per week that respondents engaged in instant messaging increased the likelihood of experience online harassment by a stranger. However, none of the measures of online routine activities were relevant to phishing victimization. This result was contrary to what was found by Reyns ( 2015 ) who concluded that booking/making reservations, online social networking, online banking and purchasing behaviors were related to phishing. Finally, focusing specifically on OIT, both Reyns ( 2013 ) and Reyns and Henson ( 2015 ) observed that banking and purchasing, as measures of online exposure, positively contributed to OIT victimization. This result was confirmed by a recent study employed by Burnes et al. ( 2020 ). In fact, as the authors concluded, while participating in commercial activities (such as online purchasing) “reflects a major societal innovation and lifestyle shift that has allowed consumers to purchase products conveniently and globally (…) the odds of using an unsecured payment portal or having information exposed in a retail data breach increases” (p. 6).

In the context of cybercrime, target attractiveness is usually operationalized through visiting risky or unprotected websites or divulge personal information online. Even though different studies argue that target suitability is a relevant TAR dimension in explaining online victimization, the results are mixed. For instance, Alshalan ( 2006 ) observed that the more people divulge their credit or debit card number and disseminate their personal information, the more they are at risk of becoming victims of cybercrime. Accordingly, Reyns and Henson ( 2015 ) suggested that having personal information posted online increases victimization of OIT. In 2013, van Wilsem found that spending much time on Internet communication activities increased the risk of victimization including online harassment. Nevertheless, Ngo et al. ( 2020 ) observed that individuals who conduct online banking and plan their travels online had a lower risk of experiencing harassment by a non-stranger. The authors suggest that individuals who conduct these types of activities online were less likely to engage in computer deviance giving the positive relationship between being harassed and deviance online. At the same time, Ngo and Paternoster ( 2011 ) observed that individuals who frequently opened unfamiliar attachments to emails received or frequently opened any file or attachment they received through instant messenger had lower odds of obtaining a computer virus. Lastly, using a sample of 9161 Internet users, Leukfeldt and Yar ( 2016 ) found that only one online activity (targeted browsing, or the search for news or targeted information search) had an effect on identity theft victimization.

Finally, scientific literature has been studying the effects of guardianship on the likelihood of victimization. The online guardianship dimension has been measured through different ways—e.g., shredding personal documents, actively changing account passwords, using antivirus software, deleting emails from unknown senders (Reyns and Henson 2015 ; Ngo and Paternoster 2011 ; Holt and Bossler 2013 ), producing as well mixed results. Holt et al. ( 2020 ) found that having a secured wireless connection decreased the risk of malware victimization. A few years before, explaining the malware victimization, Holt and Bossler ( 2013 ) found that having low-level of computer skills (a measure of lack of guardianship) and using anti-virus software (presence of guardianship) were among the significant predictors of that crime. In turn, Reyns and Henson ( 2015 ) observed that none of the online guardianship measures were relevant to reduce victimization of OIT. One possible explanation is that some victims adopted guardianship routines strategies post to their victimization. Williams ( 2016 ) observed that passive physical guardianship was effective in reducing online identity theft due to the automated form of this type of security when comparing to the others. Moreover, a positive association was found between active personal guardianship and victimization, explained by the post-victimization security reactions. Data collected by Reyns ( 2015 ) suggested a positive relationship between guardianship and victimization for phishing, hacking and malware infection, contrary to what was hypothesized by the author. Accordingly, Williams ( 2016 ) observed that having an anti-virus software was positively related to malware victimization, suggesting that individuals who experienced online victimization were more prone to install this type of software. At the same time, a positive relationship between phishing victimization and deleting emails from unknown senders was observed. Finally, Burnes et al. ( 2020 ) observed that proactive individual behaviors (e.g., shredding personal documents and actively changing account passwords), reduced the likelihood of identity theft.

Individual variables

Numerous research studies have also examined the impact of individual variables on online victimization. Alshalan ( 2006 ) found that gender had an effect on both computer virus victimization and cybercrime victimization, suggesting that males are more victimized than females. Accordingly, Holt and Turner ( 2012 ) and Reyns ( 2013 ) observed that males were at greater risk of identity theft victimization. Conversely, Anderson ( 2006 ) discovered that the estimated risk of experiencing some form of identity theft was 20% more greater for women than for men. Concerning age, while Reyns ( 2013 ) observed that older adults presented higher risk of identity theft victimization, Williams ( 2016 ) and Harrell ( 2015 ) found that younger and middle-aged adults, respectively, reported higher levels of this kind of victimization. Ngo and Paternoster ( 2011 ) observed that each additional year in age decreased the odd of obtaining a computer virus by 2% and of experiencing online defamation by 6%. More recently, Burnes et al. ( 2020 ) observed that individuals between the ages of 39 and 73 were at the highest risk of most types of identity theft, reflecting the socioeconomic capacity and consumption patterns of this generation relative to millennials. Another important result discovered by these authors was that higher educational accomplishment was related with higher risk of existing credit card/bank account identity theft victimization. Accordingly, Reyns ( 2013 ) and Reyns and Henson ( 2015 ) observed that those with higher incomes are most likely to be victimized of OIT. Williams ( 2016 ) showed that social status exhibited a curvilinear association with victimization. Lower and higher status citizens reported highest levels of victimization, while those of average status reported the lowest. Lastly, none of the sociodemographic variables—gender, age, education level, personal or household income and financial assets or possessions explained identity theft victimization in Leukfeldt and Yar’s ( 2005 ) research.

Fear of (online) crime

Fear of crime is considered a serious social problem and has been vastly studied in the last decades (Hale 1996 ). Empirical research has been testing what are the determinants of fearing crime, including individual (e.g., gender, age, social class, education,) and contextual predictors (e.g., incivilities, social cohesion, poor street lighting). Using a wider definition of fear of crime, this construct is conceptualized as a set of three dimensions: the emotional fear of crime, risk perception of victimization and the different behaviors adopted for security reasons (e.g., Gabriel and Greve 2003 ; Liska et al. 1988 ). The emotional fear of crime is a response to crime or symbols associated with it (Ferraro and La Grange 1987 ; Rader et al. 2007 ), different from risk perception which is the likelihood of victimization perceived by an individual (for instance, the likelihood of being a victim of burglary in the next 12 months ). Though they can be related (Mesch 2000 ), the cognitive dimension is distinct from the emotional fear of crime and it refers to an assessment of personal threat or a judgment that individuals make of their risk of victimization. Authors have also been distinguished formless fear from concrete fear. While the first is a generic fear not related to any type of crime, the latter corresponds to specific crimes such as fear of identity theft or fear of robbery (for instance, Keane 1992 ).

Although fear of general crime has been largely studied, limited research has been conducted about fear of online crime and even less on fear of OIT (Henson et al. 2013 ; Virtanen 2017 ; Abdulai 2020 are some exceptions). Hille et al. ( 2015 ) included two main dimensions on the fear of OIT: the fear of financial losses and fear of reputational damage . While the first is the fear of illegal or unethical appropriation and usage of personal and financial data by an unauthorized entity with the goal of getting financial benefits, the second is the fear of misuse of illegally acquired personal data with the objective of impersonation which can cause reputational damage to the victim—for instance, use the victim’s credit card to buy embarrassing products. In the present paper, we follow Hille’s et al. ( 2015 ) definition of fear of OIT.

Exploring fear of OIT is crucial since it is considered one of the most important psychological barriers to consumers (Martin et al. 2017 ), and constitutes a severe threat to the security of online transactions associated with e-commerce services. For instance, Jordan et al. ( 2018 ) explored the impact of fear of identity theft and perceived risk on online purchase intention using a sample of 190 individuals from Slovenia. First, they found a positive correlation between fear of identity theft and perceived risk. Then, they observed that perceived risk decreased the online purchase intention. Now we summarize the main determinants of fear of online crime and the results of the few studies which focused on the explanation of fear of OIT.

Determinants of fear of crime online

Sociodemographic determinants.

Gender is considered the best predictor of fear of crime in general (Hale 1996 ) with women being considered the most fearful group. Under cybercrime research, a set of studies concluded that women are as well the most fearful group, although it depends on concrete crimes. For instance, while Henson et al. ( 2013 ) found higher levels of fear on women of interpersonal violence, Yu ( 2014 ) observed no statistically significant differences between women and men for online identity theft, fraud and virus. Virtanen ( 2017 ) employed an analysis of the fear of eight types of cybercrimes in 28 countries using data from the Special Eurobarometer Survey. The author consistently found that women presented higher levels of fear of cybercrimes comparing to men. Lastly, Roberts et al. ( 2013 ) discovered that gender was not a predictor of fear of OIT which was mainly explained by contextual dimensions and the fear of traditional crime.

Concerning the relationship between age and offline fear of crime, it can be argued that the results are mixed. While some authors found that older people presented higher levels of fear (e.g., Reid and Cornrad 2004 ), others conclude that younger individuals report higher levels of fear when comparing with older adults (e.g., Ziegler and Mitchel 2003 ). In the online context, the relationship between age and fear is also not well established. For instance, Virtanen ( 2017 ) and Henson et al. ( 2013 ) found that younger people fear more online crime comparing to older ones. Roberts et al. ( 2013 ) observed that age (with a positive direction) was the only predictor of fear of OIT but it accounted for less than 1% of the unique variance in fear of OIT and related fraudulent activity. Accordingly, Alshalan ( 2006 ) and Lee et al. ( 2019 ) found that older individuals presented higher levels of fear of online crimes, suggesting that they attribute more value to property and, as a consequence, they fear losing it.

Regarding the impact of socioeconomic status, researchers have been demonstrated that groups with higher disadvantage feel more afraid offline when compared to lesser ones since they present fewer capacity to afford measures to their protection (Hale 1996 ). Accordingly, in the online context, Virtanen ( 2017 ) and Brands and Wilsem ( 2019 ) found that individuals with lower socioeconomic status presented higher levels of fear of online crime, suggesting that less advantage groups might find more difficult to deal with potential costs of an online victimization. In turn, Reisig et al. ( 2009 ) found that those reporting lower levels of socioeconomic status perceived higher levels of risk which, in turn, was associated with online behaviors that reduced the potential likelihood of online theft victimization. Concerning education, typically the literature on traditional fear of crime finds that less educated individuals report higher levels of fear (e.g., Smith and Hill 1991 ). While Alshalan ( 2006 ) and Roberts et al. ( 2013 ) found no direct association between education and general fear of cybercrime, Brands and Wilson ( 2019 ) observed lower levels of fear of online crime in higher educated individuals. On the opposite direction, Akdemir ( 2020 ) found that higher educated individuals reported higher levels of fear of cybercrime comparing to those who were less educated. Accordingly, the author argued that higher educated groups had a higher likelihood of adopting online security measures such as password management (e.g., use of multiple passwords) and elimination of suspect emails.

Previous victimization

The relationship between victimization and fear of traditional crime has been produced mixed results. For instance, Mesch ( 2000 ), Tseloni and Zarafonitou ( 2008 ) and Guedes et al. ( 2018 ) found a positive relationship between perceived risk and victimization. Regarding the relationship between fear of online crime and victimization, the few studies available observed that previous experiences with online crime are important to fear. For instance, Randa ( 2013 ) found that past experiences with cyberbullying increased fear of online crime. Moreover, Alshalan ( 2006 ) also corroborated that previous direct victimizations increased fear of cybercrime, suggesting that the negative consequences of a victimization had a ‘sensitizing effect’ which increased the insecurity on cyberspace. Additionally, Henson et al. ( 2013 ), Virtanen ( 2017 ), Lee et al. ( 2019 ), Brands and Wilsem ( 2019 ) and Abdulai ( 2020 ) suggested that previous online victimization had an impact of fear of online crime. On the contrary, non-significant results were found in Yu’s ( 2014 ) study.

Exposure to online crime and technical skills

The relationship between exposure to online crime and fear has been scarcely investigated. An exception is Roberts and colleagues’ study ( 2013 ) who found that frequency of internet use and use of internet at home where significant predictors of fear of cyber-identity theft and related fraudulent activity. Conversely, Henson et al. ( 2013 ) observed that none of the exposure variables showed statistically significant effects on online fear. Lastly, Virtanen ( 2017 ) showed that frequency of internet use was not associated with fear of cybercrime in models with interactions between gender or social status and victimization. However, the author suggested that the effects of internet use and knowledge of risks were mediated by confidence in one’s abilities. Concerning technical skills, few studies have been investigating if the perception of low technical skills is related with a higher fear of online crime. For instance, Virtanen ( 2017 ) found a negative relationship between these variables, although the author observed that being in the group with the lowest confidence in one’s abilities was not a direct predictor of fear. Finally, Abdulai ( 2020 ) observed that knowledge of cybercrime was not a predictor of fear of becoming a victim of credit/debit card fraud.

Current focus

The present study has the main objective of identifying risk factors both for OIT victimization and fear of OIT (including fear and perceived risk of victimization). Despite some knowledge on the factors associated with several forms of online victimization, there have been relatively few empirical studies on the factors that affect the likelihood of online identity theft. Additionally, existing research rarely addresses all the core dimensions of RAT (online exposure, target suitability and online guardianship). Thus, it is unclear what online activities increase the risk of online identity theft victimization and who are the most targeted individuals in terms of personal characteristics. Furthermore, while the victimization of OIT has been studied in the last years, to what extent and why individuals feel more fearful of OIT has rarely been the focus of scientific research.

Therefore, our investigation is crucial and innovative since: (a) operationalizes all the core concepts included in RAT (online exposure, target suitability and online guardianship) to fully test its prediction of OIT victimization, (b) examines not only the victimization but also the fear and perceived risk of being a victim of OIT; (c) compares the importance of both individual variables and contextual variables both for victimization and fear of this form of victimization.

Data for the current study were collected in 2017 through an online self-report anonymous survey built to explore the variables related to RAT that influenced both the victimization, the perceived risk and the fear of OIT. For that purpose, an email containing the objective of the study and the link of the survey was sent by the University of Porto services to invite students and staff (teaching and non-teaching) to participate in this study. In total, 831 individuals answered the questionnaire.

Dependent variables

In the current study three dependent variables were considered: the OIT victimization, the fear of OIT and the perception of victimization risk concerning the previous referred crime. To measure OIT victimization, respondents were asked: “how many times someone has appropriated, via Internet, personal and financial data without prior consent and knowledge and used them improperly during your lifetime” . Responses varied between 0 to more than 5 times. Lifetime OIT victimization was recoded to a dummy variable (0 = no victimization, 1 = victimization). Fear of OIT was operationalized through an adapted scale of Hille et al. ( 2015 ). This scale conceptualized fear of OIT as having two main dimensions: fear of financial losses and fear of reputational damage. A four-point Likert scale was used to rate the following items varying from 1 (not afraid) to 4 (very afraid): “how fearful do you feel if” … (1) somebody steal your personal and financial data via online? (2) somebody use your personal and financial data via online? (3) somebody damage your reputation based on the illegitimate use of your personal and financial data online?

Concerning the risk perception of victimization related to OIT it was asked the participants to rate in a scale of 1 (not likely) to 5 (very likely) the following items: “ how likely do you think that…” (1) somebody could steal your personal and financial data via online during the next 12 months? (2) somebody could use your personal and financial data via online during the next 12 months? (3) somebody could damage your reputation based on the illegitimate use of your personal and financial data online during the next 12 months? Therefore, perceived risk of OIT was adapted from scale of fear of OIT built by Hille et al. ( 2015 ) and from previous literature that conceptualizes perceived risk as the estimated likelihood of being a victim of crime in the future (e.g., Guedes et al. 2018 ).

Individual characteristics

In order to study how sociodemographic dimensions influenced the dependent variables, insofar as these may be related to patterns of Internet usage and victimization experiences, four individual characteristics of respondents were included: (a) gender (0 = male, 1 = female), (b) age (in years), (c) perceived socioeconomic status (1 = low, 2 = average, 3 = high) and (d) levels of education (1 = up to 4th years of education to 5 = postgraduate studies). Furthermore, a measure of fear of crime offline was included to understand if fear of identity theft online (concrete fear) was influenced by a more general fear of being victimized. The operationalization was based on previous studies and a two item’s measure was undertaken: (a) “How safe do you feel when walking alone in your residential area after dark?” , ( b) How safe do you feel being alone in your home after dark?”.

Three theoretical dimensions from RAT were measured: online exposure to motivated offenders, target suitability, and capable guardianship.

Online exposure

Departing from one of the aims of the present study, analyzing the relationship between exposure and victimization, fear and perceived risk of OIT, respondents were asked a set of questions to measure their online routines. Thus, to examine Internet routine activities, two different measures were used. The first was assessed by the single item “how much time, per day, in average, do you spend online?”, measured in number of hours. Additionally, in an effort to examine specific online routine activities, the frequency of specific online routines activities was rated by participants in a scale of 1 (never) to 5 (always). Following Reyns ( 2013 ), participants were asked “how often do you use the Internet for the ensuing purposes” : (1) online banking or managing finances, (2) e-mail or instant messaging, (3) watching television or listening to the radio, (4) reading online newspapers or news websites, (5) participating in chat rooms or other forums, (6) reading or writing blogs, (7) downloading music, films, or podcasts, (8) social networking (e.g., Facebook, Myspace), (9) for work or study, or (10) buying goods or services (shopping). After performing a factor analysis, the items were aggregated in three main routine activities: (1) financial routines (items 1 and 10), (2) work routines (items 2, and 9), and (3) leisure routines (items 3, 5, 6 and 7). Finally, to understand the types of payments used by respondents, we asked if they used the following forms: home banking, PayPal, credit card, pay safe card, MB Net. Respondents had two response options: ‘yes’ (coded as 1) and ‘no’ (coded as 0).

Target suitability

One of the factors that can increase individual’s likelihood of being victimized (both online and offline) is his or her attractiveness as a potential target (Reyns and Henson 2015 ). In the present study, based on previous works such as those of Paternoster (2011) and Reyns ( 2015 ), online target suitability was measured through the following question: “In the past 12 months have you” : (1) communicated with strangers online, (2) provided personal information to somebody online, (3) opened any unfamiliar attachments to e-mails that they received, (4) clicked on any of the web-links in the emails that they received, (5) opened any file or attachment they received through their instant messengers, (6) clicked on a pop-up message, or (7) visited risky websites . Participants had two response options: ‘yes’ (coded as 1) and ‘no’ (coded as 0). After performing a factor analysis, responses were computed in three indexes: (a) interaction with unknown people (items 1, 2), (b) open dubious links (items 3, 4, 5), and c) visit risky on-line contents (items 6, 7).

Online capable guardianship

Theoretically, higher guardianship might be related to lower levels of victimization in general and victimization of OIT in particular, especially in individuals who protect their personal information through multiple security behaviors. Moreover, it is expected that individuals who fear and perceived more risk of OIT are more prone to adopt these types of security measures. In the present study, to measure the capable guardianship, 13 items based on Williams ( 2016 ) and Ngo and Paternoster’s ( 2011 ) works were used. It was asked participants “For security reasons do you…” (1) avoid online banking, (2) avoid online shopping, (3) use only one computer, (4) use e-mail spam filter, (5) change security settings, (6) use different passwords for different sites, (7) avoid opening emails from people you do not know, (8) visits only trusted websites, (9) has installed and updated antivirus software, (10) installed and upgraded antispyware software, (11) has installed and updated software or hardware firewall, (12) participate in public education workshops on cybercrime, or (13) visits websites aimed at public education on cybercrime. The answers to items were dichotomized (0 = no, 1 = yes) and after a factor analysis they were combined in summated scales corresponding to four types of guardianship: (a) avoiding behaviors (items 1 and 2); (b) Protective software/hardware (items 9, 10, 11); (3) Protective behaviors (items 4, 5, 6); 4) Information (items 12, 13). Additionally, a complementary question to measure the online capable guardianship was included. Therefore, participants had to rate their perception of computer skills ranged between low, medium and high.

Data analysis

Concerning the lifetime OIT victimization, given the dichotomous nature of the variable (0 = no; 1 = yes), binary logistic regression was performed comprising the individual variables but also the variables related to their routine activities.

Moreover, linear regression analysis was executed to analyze the effects of individual and routine activities variables on the dependent variables: fear of crime and risk perception of victimization. In the first model, the individual variables were included to assess their importance in the explanation of each dependent variable (fear and risk). In the second (full) model, contextual variables were added.

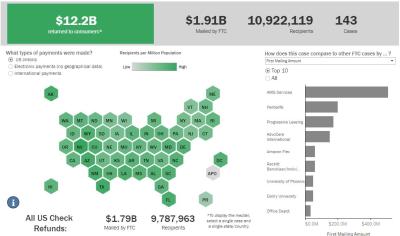

A total sample of 831 subjects completed the online survey. Sixty-six percent were females with a mean age of 27 years. The sociodemographic characteristics of the sample and the descriptive results of the studied variables are presented in Table 1 .

OIT victimization

Table 2 presents the results of the logistic regression when lifetime OIT victimization prevalence was regressed on online exposure, target suitability, capable guardianship, and individual variables. Although the model does not reach statistical significance ( p = 0.068) and Nagelkerk R 2 are relatively modest (0.059) four independent variables reached statistical significance. Considering online exposure, the use of credit card form of payment was significantly related to OIT victimization. Specifically, those who do not used these forms of payment had lower odds (34%) of becoming an OIT victim. In the same direction, the use of paysafecard as form of payment was also significantly ( p = 0.05) related to OIT victimization, suggesting that those who do not use this form of on-line payment had lower odds (59%) of becoming victim. None of the other forms of payment and routine activities (financial, work, and leisure) predicted OIT victimization. In what concerns the variables related to target suitability, only one was significantly related to OIT victimization—visit risky contents ( B = 0.283, OR 1.328)—i.e. those who reported to visit risky contents present higher odds (33%) of becoming an OIT victim. None of the studied variables related to capable guardianship were associated with OIT victimization. Considering the individual variables, gender was significantly associated with OIT victimization, with males being less likely (35%) than females of suffering an OIT victimization. Age, perceived socioeconomic status and education were not related to OIT victimization (Table 2 ).

Fear and risk of OIT

To test the correlates of fear of OIT and risk perception of being a victim of OIT, hierarchical regression analysis was performed (Table 3 ). For each dependent variable, two models were tested. The first model includes the individual variables (gender, age, SES, education, OIT victimization and general fear of crime) to control the effects of these variables on the dependent variables. In the second model (full model) the routine activities variables were added (online exposure, target suitability and capable guardianship variables).

In what concerns fear of OIT, the first model explains 10.8% of the variance. Concretely, gender, SES and general fear of crime are significant predictors of fear of OIT. Thus, females ( B = 0.186), and individuals with low SES ( B = − 0.142) present higher levels of fear of OIT. Interestingly, subjects who report more fear of crime in general also reported more fear of OIT ( B = 0.257). The model II explains 16.4% of the variance. Interaction with strangers, avoiding behaviors and computer skills were the variables significantly associated with fear of OIT. Concretely, subjects who reported more interaction with strangers are less fearful ( B = − 0.176), and those who reported to adopt more avoiding behaviors reported higher levels of fear of OIT ( B = 0.145). Finally subjects with higher computer skills are less fearful ( B = − 114). In the full model the effect of the individual variables is not affected substantially with exception of gender which do not reaches statistical significance but maintains the same direction of the association ( B = 0.105, p = 0.086), and the levels of education which reaches significance ( B = 0.084) with fear of OIT.

Regarding perceived risk of OIT victimization, the first model explains 5.3% of the variance. Concretely, gender ( B = 0.107), age ( B = 0.009), and educational levels ( B = 0.009) are positively associated with perceived risk. Moreover, SES is negatively associated with risk perception ( B = − 0.158). Thus, females, older subjects, those with higher levels of education and low SES perceived more risk of being victims of OIT. The full model (model II) explains 8.6% of the variance. It is observed that financial routines ( B = 0.077), open dubious links ( B = 0.091), and avoiding behaviors ( B = 0.080) are positively related with perceived risk. Inversely, computer skills are negatively correlated ( B = − 0.131) with perceived risk. In the full model the effect of the individual variables is not affected substantially with exception of gender which loses the statistical significance.

The current study tested the risk factors or victimization, fear and perceived risk of online identity theft. Concretely, it tried to uncover how RAT and individual variables were important to the explanation of the above referred dependent variables. Using a sample of 831 college students and staff of the University of Porto, the results suggest that RAT can be partially applied, however, other predictors were stronger in explaining these dependent variables.

Concerning the first dependent variable of the present study—victimization—, it was possible to observe a prevalence of 20% of individuals who reported to be a victim of OIT. Taken into consideration that greater exposure to online activities could be associated with higher likelihood of OIT victimization, it could be expected that individuals who spend more time online would be more victimized. In the present study, we found that time spent online does not appear to impact the risk of being victim of OIT. Nevertheless, this result follows prior studies in different cybercrime victimizations (e.g., Ngo and Paternoster 2011 ; Reyns and Henson 2015 ; Holt and Bossler 2013 ; Ngo et al. 2020 ).

Although the model did not reach statistical significance, it was found that two forms of payment (credit card and paysafecard), reflecting online exposure, and one type of suitable target (visit risky contents) were related to victimization of OIT. Furthermore, none of the measures of capable guardianship explained victimization. Concretely, it was observed that those who did not use credit card as a form of payment had lower odds (34%) of becoming an OIT victim. This result shows that not using credit card might be seen as a protective factor and is consistent with the RAT since individuals who pay on-line and use this type of payment need to insert their credit card details. Therefore, they are more exposed to potential offenders who wish to illegally obtain financial information. Besides the implication of the need to use more secure forms of online payments (e.g., PayPal), this result is especially important since the COVID-19 pandemic had necessarily increased internet usage and online purchasing. Consequently, if no security measures are adopted, these shifts in online behaviors might be exploited by fraudsters and increase victimizations levels. Even though the data from this study was collected before the pandemic, multiple reports and studies showed that cybercrime increased during and after COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, in future studies it would be relevant to understand the development of routine activities adopted by individuals and how these are influencing the levels of cybervictimization.

Contrary to prior studies such as Reyns and Henson ( 2015 ) and Burnes et al. ( 2020 ), banking and purchasing online did not contribute to an increased risk of OIT. When analyzing differences between men and women, a few explanations can be presented to understand this result. Firstly, men reported higher mean levels of financial routines ( X = 2.61) than women ( X = 2.32, p < 0.001). Moreover, men search for more information to protect themselves online and present higher perception of technical skills ( X = 2.21) than females ( X = 1.77, p < 0.001). Therefore, the fact they have more confident in their online skills might influence the relationship between financial activities and OIT victimization. Further research needs better address the relationship between this type of exposure, gender and increased likelihood of victimization of OIT.

Next, one dimension of target suitability in this study, namely visiting risky contents, had an impact in the increased likelihood of victimization. This outcome was expressive since the composite measure including ‘clicked on a pop-up message’ and ‘visited risky websites’ amplified the likelihood of becoming a victim of OIT in 34%. Therefore, risky behaviors such as visiting not very well-known websites might increase the likelihood of OIT victimization. Results concerning the impact of target suitability have been produced mixed-results. For instance, while Leukfeldt and Yar ( 2016 ) found that only one measure of online activity (targeted browsing) had an effect on OIT victimization, Ngo and Paternoster ( 2011 ) observed that click/open links decreased the likelihood of being a victim of computer virus. In Reyns and Henson’s ( 2015 ) study, only posting personal information online was significative in explaining OIT. Nevertheless, our finding shows that increasing technical skills and sensitization on the type of websites visited by individuals might be important to avoid OIT victimization.

Concerning the impact of sociodemographic variables, the only relevant variable was gender. Interestingly, and contrary to what was expecting, males were less likely (36%) than females of being victim of OIT. In fact, this results it at odds with what was found by Holt and Turner ( 2012 ) and Reyns ( 2013 ) which observed higher levels of victimization in males. In turn, Anderson ( 2006 ) observed that females had a 20% higher likelihood of being a victim of OIT and 50% of being a victim of other frauds when comparing to men. One possible explanation for our result is the fact that the higher perception of technical skills reported by men contributed to the decreased possibility of being victimized comparing to women. However, as it was previous mentioned, since the model did not reach statistical significance, it is necessary to analyze the data with precaution. In future studies, it would be important to include other factors that might contribute to the explanation of OIT victimization. For instance, one of the most relevant risk factors that may impact identity theft is the online deviance (Ngo and Paternoster 2011 ; Holt and Turner 2012 ). Previous studies showed that individuals who reported either malicious software infections (Boss and Holt 2009 ) or harassment (Holt and Bossler 2009 ) also reported participation in online deviance. A great deal of research is needed to expand our understanding of RAT, cybercrime and OIT victimization.

We now turn our attention to the results concerning fear and risk of OIT. Although online victimization has been extendedly tested, the same has not been observed in fear and risk perception of OIT. Research has been showing that higher levels of risk perception decrease the likelihood of online purchase intentions (Reisig et al. 2009 ). Moreover, fear of OIT is decreasing consumer trust and confidence in using Internet to conduct business (Roberts et al. 2013 ). Our results attribute partially support to RAT but contribute with novel insights to the understanding of fear and risk perception of OIT.

First, fear was not explained by previous victimization of OIT, confirming the existence of mixed results concerning the relationship between fear and victimization. Instead, and in accordance with Roberts et al. ( 2013 ) the strongest predictor of fear of OIT was general fear of crime. This finding means that individuals who score higher on general fear of crime will present greater fear online. One can argue that dispositional factors such as general fear might be more important than daily internet routines to the understanding of fear of OIT. Studying the relationship between fear of crime, dispositional fear and personality dimensions, Guedes et al. ( 2018 ) found a positive correlation between dispositional fear and fear of crime. This result is in accordance with Gabriel and Greve’s ( 2003 ) theoretical work who argued that fear of concrete situations is related with a more general tendency of experiencing fear. Interestingly, general fear of crime in our sample did not explain risk perception of OIT, suggesting that fear and risk are two different dimensions. Accordingly, while fear of crime is emotional in nature, risk perception is a cognition. In fact, fear of crime is not a perception of the environment, but instead an emotional reaction to the perceived environment (Warr 2000 ), involving a set of different emotions towards the possibility of victimization (Jackson and Gouseti 2012 ). On the other hand, perceived risk is usually conceptualized as a cognitive judgment or an estimate of the risk of victimization (e.g., Ferraro and LaGrange 1987 ). Even though the emotional fear of crime and perceived risk might be highly correlated (e.g., Mesch 2000 ), different predictors explain each type of the dimensions (e.g., Rountree and Land 1996 ; Guedes et al. 2018 ). Therefore, the current results might shed some light to the debate of the multidimensionality of fear of crime.

The second important result is related to the applicability of RAT in the explanation of both fear and risk perception. Concerning fear of OIT, none of the online exposure dimensions of RAT explained fear, as in Henson et al. ( 2013 ). In turn, subjects who reported more interactions with strangers were less fearful. This result can be explained by the fact that interacting with strangers, reflecting the target suitability, might be a routine of individuals who perceive less risk of victimization which, in turn, is positively correlated with fear. Given this intriguing result, more research is needed to understand the impact of target suitability on fear of OIT. Other finding was that those who reported to adopt more avoiding behaviors presented higher levels of fear. Concretely, avoiding online banking and shopping online were predictors of fear of OIT. It is plausible to affirm that these online guardianship dimensions are also proxy measures of the behavioral dimension of fear of crime which, in turn, is generally related either to emotional and cognitive dimensions of the fear of crime in a larger sense. Liska et al. ( 1988 ) observed that fear and constrained social behavior were part of a positive escalating loop, where fear constrained social behavior which, in turn, increased fear. It would be interesting to apply the same model to fear of OIT. Furthermore, as in Virtanen ( 2017 ), we found that subjects with higher computer skills were less fearful and perceived lower risk of victimization. According to Jackson ( 2004 ), worry about crime is related to the seriousness of the consequences of victimization, the likelihood of the event occurring and the ability to control its occurrence. Therefore, one can argue that augmented levels of perception of technical skills might increase the feelings of control over the risk of being victim of OIT. The confidence in individual’s own technical skills was also a predictor of risk perception of OIT, showing the importance of this variable in the present study. Under the applicability of RAT to perceived risk of victimization, it is also important to note that different predictors, comparing to fear, explained risk perception. In fact, one measure of online exposure (financial activities) is positively related to higher levels of perceived risk of victimization. Moreover, open dubious links increase perceived risk of OIT but not the fear of this type of crime. Therefore, these results shed light to the importance of implementing preventive actions and increased knowledge of the risks of online activities since, as it was previously mentioned, higher risk perception of OIT is related to lower levels of online purchase intentions.

Lastly, the present study also intended to analyze the impact of sociodemographic variables on both fear and risk perception of victimization online. Generally, the best predictor of fear of crime offline is gender (Hale 1996 ). However, in the final model of the present study, gender lost its significance in the explanation of fear of OIT. This result is in accordance with others such as Yu ( 2014 ), who observed no statistical significative differences between women and men for OIT, fraud and virus. Moreover, gender was not a predictor of fear of OIT in Roberts et al. ( 2013 ) research. Instead, our findings suggest that education and socioeconomic status are predictors not only of fear but also of risk of OIT. While more educated individuals presented higher levels of fear and risk perception, as in accordance with Akdemir ( 2020 ), lower socioeconomic status predicted both fear and risk of OIT, as in Virtanen ( 2017 ) and Brands and Wilsem ( 2019 ). This result suggests that those individuals are most affected by property-focused victimization and predict more difficulties in dealing with potential costs of that victimization.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge the limitations of the present study. Our data stems from a convenience sample of university population, that includes students and staff of the same educational environment, not allowing generalization to a larger population. While a more diverse and representative population would permit a more diversified experiences and contexts, the positive aspect is that they are a population that uses computer and internet daily. Moreover, previous studies have also utilized samples of college students (e.g., Bossler and Holt 2009 ; Holt and Bossler 2009 ).

Future research can expand to other types of online victimization and increase the list of online activities with the objective of identifying common and specific risk/protective factors associated with cybervictimization. Since in our study individual computer skills were an important predictor of fear and risk of OIT, we suggest a deeper exploration of this variable as a mediator between online exposure and victimization. Finally, qualitative studies on this topic will be very useful to explore the (in)security experiences of the individuals, their online routines, and subjective perception of the risks to which they are exposed and in what activities and contexts. Another important limitation of the present study is the fact that it only relies on individual online activities to understand the victimization of online identity theft. In future studies it would be important to measure if the identity theft victimization occurred due to a data breach which put in risk an individual’s personal/financial information stored by a company or a government. For instance, Burnes et al. ( 2020 ) showed that individuals reporting breached personal information from a company or government were more likely to experience multiple forms of identity theft.

Given the costs associated with cybercrime, and the increasing use and importance of the internet in our daily lives, the identification of risk and protective factors for cybervictimization and fear of cybercrime will be very relevant for prevention strategies.

Anderson, K.B. 2006. Who are the victims of identity theft? The effect of demographics. Journal of Public Policy and Marketing 25 (2): 160–171.

Article Google Scholar

Abdulai, M. 2020. Examining the effect of victimization experience on fear of cybercrime: University student’s experience of credit/debit card fraud. International Journal of Cyber Criminology 14 (1): 157–1754.

Google Scholar

Akdemir, N. 2020. Examining the impact of fear of cybercrime on internet users’ behavioral adaptations, privacy calculus and security intentions. International Journal of Eurasia Social Sciences 11 (40): 606–648.

Alshalan, A. 2006. Cyber-crime fear and victimization: An analysis of a national survey . Mississippi: Mississippi State University.

Bellah, J. 2001. Training: Identity theft. Law and Order 49 (10): 222–226.

Bossler, A.M., and T.J. Holt. 2009. On-line activities, guardianship, and malware infection: An examination of routine activities theory. International Journal of Cyber Criminology 3 (1): 974–2891.

Brands & Wilsem. 2019. Connected and fearful? Exploring fear of online financial crime, Internet behaviour and their relationship. European Journal of Criminology 00: 1–12.

Burnes, D., M. DeLiema, and L. Langton. 2020. Risk and protective factors of identity theft victimization in the United States. Preventive Medicine Reports 17: 1–8.

Capeller, W. 2001. Not such a neat net: Some comments on virtual criminality. Social & Legal Studies 10 (2): 229–242.

Choi, K. 2008. An empirical assessment of an integrated theory of computer crime victimisation. International Journal of Cyber Criminology 2 (1): 308–333.

Cohen, L.E., and M. Felson. 1979. Social change and crime rate trends: A routine activity approach. American Sociological Review 44: 588–608.

Copes, H., and L. Vieraitis, L. 2012. identity theft. In The Oxford handbook of crime and public policy , ed. M. Tonry. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199844654.001.0001

Eck, J.E., and R.V. Clarke. 2003. classifying common police problems: A routine activity approach. Crime Prevention Studies 16: 7–39.

Ferraro, K., and R. LaGrange. 1987. The measurement of fear of crime. Sociological Inquiry 57 (1): 70–97.

Gabriel, U., and W. Greve. 2003. The psychology of fear of crime: Conceptual and methodological Perspectives. British Journal of Criminology 43 (1): 600–614.

Garrison, C.P., and M. Ncube. 2011. A longitudinal analysis of data breaches. Information Management & Computer Security 19 (4): 216–230.

Golladay, K., and K. Holtfreter. 2017. The consequences of identity theft victimization: An examination of emotional and physical health outcomes. Victims & Offenders 12 (5): 741–760.

Grabosky, P. 2001. Virtual criminality: Old wine in new bottles? Social & Legal Studies 10 (2): 243–249.

Guedes, I., S. Domingos, and C. Cardoso. 2018. Fear of crime, personality and trait emotions: An empirical study. European Journal of Criminology 15 (6): 658–679.

Hale, C. 1996. Fear of crime: A review of the literature. International Review of Victimology 4: 79–150.

Harrell, E., and L. Langton. 2013. Victims of identity theft, 2012 (NCJ 243779) . Washington: Bureau of Justice Statistics.

Harrell, E. 2015. Victims of identity theft , 2014, Bureau of Justice Statistics, NCJ 248991.

Harrell, E. 2019. Victims of identity theft , 2016: Bulletin.

Henson, B., B.W. Reyns, and B.S. Fisher. 2013. Fear of crime online? Examining the effect of risk, previous victimization, and exposure on fear of online interpersonal victimization. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 29 (4): 475–497.

Hille, P., G. Walsh, and M. Cleveland. 2015. Consumer fear of online identity theft: Scale development and validation. Journal of Interactive Marketing 30: 1–19.

Holt, T.J., and A.M. Bossler. 2009. Examining the applicability of lifestyle-routine activities theory for cybercrime victimization. Deviant Behavior 30 (1): 1–25.

Holt, T.J., and A.M. Bossler. 2013. Examining the relationship between routine activities and malware infection indicators. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 29 (4): 420–436.

Holt, T.J., and M. Turner. 2012. Examining risks and protective factors of on-line identity theft. Deviant Behavior 33 (4): 308–323.

Holt, T.J., J. van Wilsem, S. van de Weijer, and R. Leukfeldt. 2020. Testing an integrated self-control and routine activities framework to examine malware infection victimization. Social Science Computer Review 38 (2): 187–206.

Jackson, J. 2004. Experience and expression: Social and cultural significance in the fear of crime. British Journal of Criminology 44 (6): 946–966.

Jackson, J., and I. Gouseti (eds). 2012. Fear of crime. In The encyclopedia of theoretical criminology . Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Jordan, G., R. Leskovar, and Marič M. 2018. Impact of fear of identity theft and perceived risk on online purchase intention. Organizacija 51 (2): 146–155.

Keane, C. 1992. Fear of crime in Canada: An examination of concrete and formeless fear of victimization. Canadian Journal of Criminology 34 (2): 215–224.

Koops, B.J., and R.E. Leenes. 2006. ID theft, ID fraud and/or ID-related crime-definitions matter. Datenschutz Und Datensicherheit 30 (9): 553–556.

Lee, S., K. Choi, S. Choi, and E. Englander. 2019. A test of structural model for fear of crime in social networking sites. International Journal of Cybersecurity Intelligence Cybercrime 2 (2): 5–22.

Leukfeldt, E.R., and M. Yar. 2016. Applying routine activity theory to cybercrime: A theoretical and empirical analysis. Deviant Behavior 37 (3): 263–280.

Li, Y., A. Yazdanmehr, J. Wang, and H.R. Rao. 2019. Responding to identity theft: A victimization perspective. Decision Support Systems 121: 13–24.

Liska, A.E., A. Sanchirico, and M.D. Reed. 1988. Fear of crime and constrained behavior: Specifying and estimating a reciprocal effects model. Social Forces 66 (3): 827–837.

Marcum, C., G. Higgins, and M. Ricketts. 2010. Potential factors of online victimization of youth: An examination of adolescent online behaviors utilizing routine activity theory. Deviant Behavior 31 (5): 381–410.

Martin, K.D., A. Borah, and R.W. Palmatier. 2017. Data privacy: Effects on customer and firm performance. Journal of Marketing 81 (1): 36–58.

Mesch, G.S. 2000. Perceptions of risk, lifestyle activities, and fear of crime. Deviant Behavior 21 (1): 47–62.

McNeeley, S. 2015. Lifestyle-routine activities and crime events. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 31 (1): 30–52.

Ngo, F., and R. Paternoster. 2011. Cybercrime victimization: An examination of individual and situational level factors. International Journal of Cyber Criminology 5 (1): 773–793.

Ngo, F., A. Piquero, J. LaPrade, and B. Duong. 2020. Victimization in cyberspace: Is it how long we spend online, what we do online, or what we post online? Criminal Justice Review 45 (4): 430–451.

Piquero, N.L. 2018. White-collar crime is crime: Victims hurt just the same. Criminology & Pub. Pol’y 17: 595.

Pratt, T.C., K. Holtfreter, and M.D. Reisig. 2010. Routine online activity and Internet fraud targeting: Extending the generality of routine activity theory. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 47: 267–296.

Rader, N., D. May, and S. Goodrum. 2007. An empirical assessment of the ‘threat of victimization’: Considering fear of crime, perceived risk, avoidance, and defensive behaviors. Sociological Spectrum: MId-Shouth Sociological Association 27 (5): 475–505.

Randa, R. 2013. The influence of the cyber-social environment on fear of victimization: Cyber bullying and school. Security Journal 26: 331–348.

Reid, L.W., and M. Konrad. 2004. The gender gap in fear of crime: Assessing the interactive effects of gender and perceived risk on fear of crime. Sociological Spectrum 24 (4): 399–425.

Reisig, M.D., T.C. Pratt, and K. Holtfreter. 2009. Perceived risk of internet theft victimisation: Examining the effects of social vulnerability and financial impulsivity. Criminal Justice and Behavior 36 (4): 369–384.

Reyns, B.W. 2013. Online routines and identity theft victimization: Further expanding routine activity theory beyond direct-contact offenses. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 50 (2): 216–238.

Reyns, B.W. 2015. A routine activity perspective on online victimisation: Results from the Canadian General Social Survey. Journal of Financial Crime 22 (4): 396–411.

Reyns, B.W., and B. Henson. 2015. The thief with a thousand faces and the victim with none: Identifying determinants for online identity theft victimization with routine activity theory. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology 60 (10): 1119–1139.

Reyns, B.W., B. Henson, and B.S. Fisher. 2011. Being pursued online: Applying cyberlifestyle–routine activities theory to cyberstalking victimization. Criminal Justice and Behavior 38: 1149–1169.

Reyns, B.W., and R. Randa. 2017. Victim reporting behaviors following identity theft victimization: Results from the National Crime Victimization Survey. Crime & Delinquency 63 (7): 814–838.

Roberts, L.D., D. Indermaur, and C. Spiranovic. 2013. Fear of cyber-identity theft and related fraudulent activity. Psychiatry, Psychology, & Law 20: 315–328.

Rountree, W., and K. Land. 1996. Perceived risk versus fear of crime: Empirical evidence of conceptually distinct reactions in survey data. Social Forces 74 (4): 1353–1376.

Skogan, W., and M. Maxfield. 1981. Coping with crime: Individual and neighborhood reactions . Beverly Hills: Sage.

Smith, L.N., and G.D. Hill. 1991. Perceptions of crime seriousness and fear of crime. Sociological Focus 24 (4): 315–327.

Tatham, M. 2018. “Identity Theft Statistics.” Experian. https://www.experian.com/blogs/ask-experian/identity-theft-statistics/ .

Tseloni, A., and C. Zarafonitou. 2008. Fear of crime and victimization: A multivariate analyses of competing measurements. European Journal of Criminology 5 (4): 387–409.

Van Wilsem, J. 2013. Hacking and harassment—Do they have something in common? Comparing risk factors for online victimization. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 29 (4): 437–453.

Virtanen, S. 2017. Fear of cybercrime in Europe: Examining the effects of victimization and vulnerabilities. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law 24 (3): 323–338.

Wang, W., Y. Yuan, and N. Archer. 2006. A Contextual framework for combating identity theft. IEEE Security and Privacy 4 (2): 30–38.

Warr, M. 1984. Fear of victimization: Why are women and the elderly more afraid? Social Science Quarterly 65 (6): 81–702.

Warr, M. 2000. Fear of crime in the United States: Avenues for research and policy. Measurement and Analysis of Crime and Justice 4: 451–489.

Williams, M. 2016. Guardians upon high: An application of routine activities theory to online identity theft in Europe at the country and individual level. British Journal of Criminology 56: 21–48.

Yar, M. 2005. The Novelty of ‘Cybercrime’: An Assessment in Light of Routine Activity Theory. European Journal of Criminology 2 (4): 407–427.

Yu, S. 2014. Fear of cybercrime among college students in the United States: An exploratory study. International Journal of Cyber Criminology 8 (1): 36.

Ziegler, R., and D. Mitchell. 2003. Aging and fear of crime: An experimental approach to an apparent paradox. Experimental Aging Research 29 (2): 173–187.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Criminology, Faculty of Law, University of Porto, Porto, Portugal

Inês Guedes, Margarida Martins & Carla Sofia Cardoso

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Inês Guedes .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article