Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Critical Thinking and Moral Education

1988, Thinking: The Journal of Philosophy for Children

Related Papers

Craig Gibson

Mark Weinstein

Peter A Facione

John P. Portelli

Educational Theory

Topoi-an International Review of Philosophy

Clarence Sheffield Jr

Gary Richmond

Critical thinking can help its practitioners understand the issues in society. The authors discuss the method involved in evaluating the validity of arguments and the need for teaching and using critical thinking skills across the curriculum. Introduction Critical thinking, simply stated, is arriving at conclusions based on the legitimacy of one's research. "Legitimacy" is the operative word here, for the critical thinking process eradicates faulty thinking patterns and, in particular, those known as fallacies. Why is this process important in today's teaching climate? With controversies like the 2000 Presidential election, the McVeigh execution, the Megan's Law Internet connection, and, above all, the September 11th tragedy, there can be little doubt that improved critical thinking could provide a means of combating tendencies that might undermine some basic democratic rights on no firmer foundation than raw emotion, popular opinion, ideology and certain infle...

John Eigenauer

Ample literature on the instruction of critical thinking in higher education can help colleges and universities make proper decisions about teaching and assessing critical thinking.

Harvey Siegel

The eighties witnessed a growing accord that the heart of education lies exactly where traditional advocates of a liberal education always said it was-in the processes of inquiry, learning and thinking rather than in the accumulation of disjointed skills and senescent information. By the decade's end the movement to infuse the K-12 and post-secondary curricula with critical thinking (CT) had gained remarkable momentum. This success also raised vexing questions: What exactly are those skills and dispositions which characterize CT? What are some effective ways to teach CT? And how can CT, particularly if it becomes a campus-wide, district-wide or statewide requirement, be assessed? When asked by the individual professor or teacher seeking to introduce CT into her own classroom, such questions are difficult enough. But they take on social, fiscal, and political dimensions when asked by campus curriculum committees, school district offices, boards of education, and the educational t...

RELATED PAPERS

Keira Lowther

Marta Ugarte

Mónica Montoya Ríos

Joris Tieleman

Mondes en développement

Touhami Abdelkhalek

BMC Health Services Research

Shahrukh Khan

Fabrício C Lunardi

Journal of Travel Research

Senija Causevic

Heart, Lung and Circulation

Shakiya Ershad

Point of Care: The Journal of Near-Patient Testing & Technology

Livio Caberlotto

Sarah Veloso

Juan Barajas

Arquivos Brasileiros de Oftalmologia

Cristina Muccioli

ISABEL CRISTINA RODRIGUES FERREIRA

2011 16th IEEE International Conference on Engineering of Complex Computer Systems

Schahram Dustdar

The Lancet Global Health

Christopher Mikton

Molecular Therapy

Fayez Dawood

Revista do Instituto de Medicina Tropical de São Paulo

Maria Augusta Priori Monteiro

Acta Neurologica Scandinavica

David Allen

RELIEF - REVUE ÉLECTRONIQUE DE LITTÉRATURE FRANÇAISE

Camille Richert

Journal of Minerals and Materials Characterization and Engineering

Mohammed Adamu

Howard毕业证文凭霍华德大学本科毕业证书 美国学历学位认证如何办理

Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters

yingsheng zhang

Protoplasma

Orna Liarzi

RISHABH SHUKLA

See More Documents Like This

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

Education's Epistemology: Rationality, Diversity, and Critical Thinking

Professor of Philosophy

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This collection extends and further defends the “reasons conception” of critical thinking that Harvey Siegel has articulated and defended over the last three-plus decades. This conception analyzes and emphasizes both the epistemic quality of candidate beliefs, and the dispositions and character traits that constitute the “critical spirit”, that are central to a proper account of critical thinking; argues that epistemic quality must be understood ultimately in terms of epistemic rationality; defends a conception of rationality that involves both rules and judgment; and argues that critical thinking has normative value over and above its instrumental tie to truth. Siegel also argues, contrary to currently popular multiculturalist thought, for both transcultural and universal philosophical ideals, including those of multiculturalism and critical thinking themselves. Over seventeen chapters, Siegel makes the case for regarding critical thinking, or the cultivation of rationality, as a preeminent educational ideal, and the fostering of it as a fundamental educational aim. A wide range of alternative views are critically examined. Important related topics, including indoctrination, moral education, open-mindedness, testimony, epistemological diversity, and cultural difference are treated. The result is a systematic account and defense of critical thinking, an educational ideal widely proclaimed but seldom submitted to critical scrutiny itself.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- Google Scholar Indexing

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Navigate to any page of this site.

- In the menu, scroll to Add to Home Screen and tap it.

- In the menu, scroll past any icons and tap Add to Home Screen .

Religious Educator Vol. 18 No. 3 · 2017

Critical thinking in religious education, shayne anderson.

Shayne Anderson, "Critical Thinking in Religious Education," Religious Educator 18, no. 3 (2018): 69–81.

Shayne Anderson ( [email protected] ) was an instructor at South Ogden Junior Seminary when this article was published.

A common argument in an increasingly secular world today is that religion poses a threat to world peace and human well-being. Concerning the field of religious education, Andrew Davis, an honorary research fellow at Durham University, argues that religious adherents tend to treat others who do not agree with them with disrespect and hostility and states that efforts to persuade them to behave otherwise would be “profoundly difficult to realize.” [1] Consequently, he believes that religious education should consist only of a moderate form of pluralism. Religious education classes, in his view, should not make claims of one religion having exclusive access to the truth.

Others argue that religious education should consist only of teaching about religion in order to promote more democratic ways of being. [2] Their perception is that religion is yet another distinguishing and divisive tool used by those who seek to discriminate against others, thus impeding the progress of pluralistic democracies. Further, those perceived as religious zealots, so the argument goes, are the least apt to give critical thought to either their own beliefs or the beliefs of others. [3] This reasoning, in which religion and critical thinking are viewed as antithetical, is especially prevalent in popular culture, outside the measured confines of peer-reviewed publishing.

Reasons for why religion and critical thinking might be viewed as incompatible are as varied as the authors who generate the theories. They include the following: religions often claim to contain some amount of absolute truth, an idea in itself that critical theorists oppose; individual religions generally do not teach alternate views, a requisite for critical thinking; and, in critical theory, truth is comprised of “premises all parties accept.” [4] Theorist Oduntan Jawoniyi reduces the argument down to the fact that religious claims of truth “are empirically unverified, unverifiable, and unfalsifiable metaphysical truths.” [5]

One explanation for variations in opinions concerning the place of critical thinking in religious education may be that no consistent definition exists for critical thinking, a concept that stretches across several fields of study. For instance, the field of philosophy has its own nuanced definition of critical thinking, as does the field of psychology. My first aim in this article is to survey a range of definitions in order to settle upon a functional definition that will allow for faith while still fulfilling the objectives of critical thinking, and my second aim is to explore how this definition can apply to religious education in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Defining Critical Thinking

The first definition under consideration comes from a frequently cited website within the domain of critical thinking. Here critical theorists Michael Scriven and Richard Paul endeavor to encapsulate in one definition the wide expanse of critical thinking’s many definitions: “Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/ or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action. In its exemplary form, it is based on universal intellectual values that transcend subject matter divisions: clarity, accuracy, precision, consistency, relevance, sound evidence, good reasons, depth, breadth, and fairness.” [6]

Assessing the definition in parts will allow for a thorough examination, beginning with a look at critical thinking as being active and intellectually disciplined. Such admonitions are repeated often in the scriptures. The thirteenth article of faith teaches that members of the Church “seek after” anything that is “virtuous, lovely, or of good report or praiseworthy.” The Prophet Joseph Smith borrows terminology here from what he calls the “admonition of Paul”—from the book of Philippians, where Paul lists many of the same qualities and then suggests, “Think on these things” (Philippians 4:8).

Common scriptural words that suggest active, skillful, and disciplined thinking include inquiring , pondering , reasoning , and asking . Additional scriptures suggest such things as “study it out in your mind” (D&C 9:8) or “seek learning, even by study and also by faith” (D&C 88:118). Assuredly, the portion of the definition of critical thinking pertaining to intellectual discipline fits well within the objectives of the Church’s education program.

The next part of the definition given by Scriven and Paul includes “conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/ or evaluating information.” The Gospel Teaching and Learning handbook, used by teachers and leaders in the Seminaries and Institutes of Religion program of the Church, sets forth the “fundamentals of gospel teaching and learning.” [7] Included in these fundamentals are (a) identifying doctrines and principles, (b) understanding the meaning of those doctrines and principles, (c) feeling the truth and importance of those doctrines and principles, and (d) applying doctrines and principles. Comparing the definition for critical thinking to the fundamentals of gospel teaching and learning, one can argue that conceptualizing is akin to identifying and analyzing, both of which require the understanding sought for by the previously mentioned fundamentals. Synthesizing and evaluating can be a part of understanding and feeling the importance of a concept. Also, application is found in both the definition and the fundamentals of gospel teaching and learning. It is an integral part of critical thinking and effective religious education within the Church.

Finally, according to this definition, critical thinking assesses “information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action.” This portion of the definition seems equally suited for religious education. So much of religion is based on personal experience and reflection on those experiences. Owing to the personal nature of religious observations, experiences, reflections, and reasoning, adherents often find them difficult to fully explain. This personal experience may be compared to a baseball player who has mastered the art of batting. Intellectually, the player may understand perfectly what must be done, as he or she may have practiced it innumerable times, but when asked to explain it to someone else the player is unable to do so. Such a situation does not detract from the fact that the batter has mastered the art, yet the explanation remains difficult. Additionally, religious experiences are often very personal in nature. Due to the value attributed to those experiences, a person may not choose to share them frequently because of a fear that others will not understand or may even attempt to degrade and minimize those experiences and the feelings associated with them. Thus, even on the occasion when someone attempts to articulate such experiences, they remain unexplained.

In a religious setting, information derived from observation, experience, and communication may come from meeting with others who share religious beliefs. Moroni 6:5 touches on this idea. “And the church [members] did meet together oft, to fast and to pray, and to speak with one another concerning the welfare of their souls.” Congregating has long been a cornerstone of religious experience. Doing so provides members opportunities for observation, experience, reflection, and communication, all of which make up the delicate tapestry of religious belief and behavior.

Adding to the definition given by Scriven and Paul, college professor and author Tim John Moore asserts that another quality important in critical thought is skepticism, verging on agnosticism, toward knowledge—calling into question whether reality can be known for certain. [8] This skepticism carries with it immediate doubt prior to being presented with knowledge. Others have termed it as a “doubtful mentality.” [9] This definition does not seem able to coexist with faith-motivated critical thinking. Many scriptures teach about the importance of faith trumping doubt, the most recognizable among them likely being James 1:5–6: “If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God, that giveth to all men liberally, and upbraideth not; and it shall be given him. But let him ask in faith, nothing wavering. For he that wavereth is like a wave of the sea driven with the wind and tossed.”

Concerning the type of doubt that arises even before learning facts, Dieter F. Uchtdorf of the Church’s First Presidency said, “Doubt your doubts before you doubt your faith.” [10] This admonition indicates that there is an ultimate source of truth, and when our doubts loom large it is better to doubt those doubts instead of doubting God. The Doctrinal Mastery: Core Document , a part of the S&I curriculum introduced in the summer of 2016, states that “God . . . is the source of all truth. . . . He has not yet revealed all truth.” [11] Thus, doubt should be curbed at the point when we do not have all the evidence or answers we seek. Such is the case in the scientific method: a tested hypothesis leads to a theory, and confirmed theories lead to laws. Fortunately, neither hypotheses nor theories are abandoned for lack of proof or the existence of doubt concerning them.

Some within a religious community may be hesitant to apply critical thinking to their own religious beliefs, believing that doing so could weaken their faith. Psychologist Diane Halpern, however, suggests that critical thinking need not carry with it such negative connotations. “In critical thinking , the word critical is not meant to imply ‘finding fault,’ as it might be used in a pejorative way to describe someone who is always making negative comments. It is used instead in the sense of ‘critical’ that involves evaluation or judgement, ideally with the goal of providing useful and accurate feedback that serves to improve the thinking process.” [12] Applying critical thinking need not indicate a lack of faith by a believer—an important point to consider when applying critical thinking to religious education. Critically thinking Christian believers are adhering to the Savior’s commandment to “ask, and it shall be given you; seek, and ye shall find; knock, and it shall be opened unto you” (Matthew 7:7).

Religious believers may be concerned that other critical thinkers have reached an opinion different than theirs. This concern can be addressed by the way critical thinking is defined. Professor of philosophy Jennifer Mulnix writes that “critical thinking, as an intellectual virtue, is not directed at any specific moral ends.” [13] She further explains that critical thinkers do not have a set of beliefs that invariably lead to specific ends, suggesting that two critical thinkers who correctly apply the skills and attitudes of critical thinking to the same subject could hold opposing beliefs. Such critical thinking requires a sort of mental flexibility, a willingness to acknowledge that a person may not be in possession of all the facts. Including such flexibility when defining critical thinking does not disqualify its application to religious education. A religious person can hold beliefs and knowledge while remaining flexible, just as a mathematician holds firm beliefs and knowledge but is willing to accept more and consider alternatives in the light of additional information. In other words, being in possession of facts that a person is unwilling to relinquish does not mean that he or she is unwilling to accept additional facts.

Elder Dallin H. Oaks spoke about the idea of differing conclusions when addressing religious educators. “Because of our knowledge of [the] Plan and other truths that God has revealed, we start with different assumptions than those who do not share our knowledge. As a result, we reach different conclusions on many important subjects that others judge only in terms of their opinions about mortal life.” [14] Each person brings different life experience and knowledge, which they call upon to engage in critical thinking. While both are employing critical-thinking skills, they may be doing so with different facts and differing amounts of facts. All of the facts in consideration may be true, but because of the way those facts are understood, different conclusions are reached. Still, the thinking taking place can be correctly defined as critical.

Another belief included by some in a definition of critical thinking, though at odds with the edifying instruction presented in LDS religious education, is addressed by Rajeswari Mohan, who suggests that to teach using critical thinking would require “a re-understanding of the classroom.” [15] Generally, the understanding that currently exists of the classroom, both inside and outside of religious education, consists of creating an atmosphere of respect and trust, a safe place to learn and grow—something that Mohan calls “cosmopolitan instruction.” [16] In its place Mohan advocates that the classroom become “a site of contestation,” [17] which connotes controversy, argument, and divisiveness. Of course, it is possible to contest a belief, debate, and even disagree while still maintaining trust and respect, but such a teaching atmosphere is what Mohan considers cosmopolitan and, as such, it would require no re-understanding to accomplish it.

Elizabeth Ellsworth described her experience when attempting to employ the type of approach Mohan suggests in her own classroom. [18] In reflecting on the experience, she noted that it exacerbated disagreements between students rather than resolving or solving anything. She summarized what took place by saying, “Rational argument has operated in ways that set up as its opposite an irrational Other.” [19] Rather than having her class engage in discussion and learning, Ellsworth witnessed students who refused to talk because of the fear of retaliation or fear of embarrassment.

Such a situation does not align with D&C 42:14, “If ye receive not the Spirit ye shall not teach.” Additionally, this confrontational atmosphere in the learning environment seems to run counter to the doctrines taught by the Savior. Consider the words of Christ in 3 Nephi 11:29: “I say unto you, he that hath the spirit of contention is not of me, but is of the devil, who is the father of contention, and he stirreth up the hearts of men to contend with anger, one with another.”

Many authors who offer definitions of critical thinking discuss how critical thinking leads to action; one author states, “Criticality requires that one be moved to do something.” [20] President Thomas S. Monson, while a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, said, “The goal of gospel teaching . . . is not to ‘pour information’ into the minds of class members . . . . The aim is to inspire the individual to think about, feel about, and then do something about living gospel principles.” [21] This application is the foundation of the teachings of Jesus Christ, the very purpose of his Atonement, to allow for individuals to change. This change does not solely consist of stopping some behavior but also includes starting new behaviors. Elder Neal A. Maxwell, for example, suggested that many of us could make more spiritual progress “in the realm of the sins of omission . . . than in any other place.” [22]

Critical Thinking Exaggerated

President Boyd K. Packer taught that “tolerance is a virtue, but like all virtues, when exaggerated, it transforms itself into a vice.” [23] This facet of critical thinking whereby critical thinking prompts action must be explained carefully, as it can be exaggerated and transformed into a vice. Mohan described this aspect of critical thinking that moves individuals to action outside of the classroom as having a “goal of transformative political action” aimed at challenging, interrupting, and undercutting “regimes of knowledge.” [24] Pedagogy of the Oppressed author and political activist Paulo Freire taught that this action brought about the “conquest” [25] of an oppressed class in a society over its oppressors. Some would argue that if it does not lead to this kind of contending, transformative action, critical thinking is incomplete. [26]

Transformative action taken by individuals to change themselves is necessary. Yet the idea that one can effect change within the Church, for individuals or the organization itself, by compulsion or coercion in a spirit of conquest can lead to “the heavens [withdrawing] themselves; the Spirit of the Lord [being] grieved” (D&C 121:37). Critical thinking defined to include this contention does not have a place in religious education within the Church.

A balanced definition of critical thinking that allows for faith in things which are hoped for and yet unseen (see Alma 32:21) may look something like this: Critical thinking consists of persistent, effortful, ponderous, and reflective thought devoted to concepts held and introduced through various ways, including experience, inquiry, and reflection. That person then analyzes, evaluates, and attempts to understand how those concepts coincide and interact with existing knowledge, ready to abandon or employ ideas based upon their truthfulness. This contemplation then leads the person to consistent and appropriate actions.

Because of the benefits of critical thinking, some have taken its application to an extreme, allowing it to undermine faith. Addressing a group of college students in 1996, President Gordon B. Hinckley said, “This is such a marvelous season of your lives. It is a time not only of positive thinking but sometimes of critical thinking. Let me urge you to not let your critical thinking override your faith.” [27]

Examples in Doctrine

Despite a potential to undermine faith when applied incorrectly, critical thinking holds too much promise to be abandoned. This is particularly the case for religious education in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Not only do questions and critical thought have an appropriate place in the Church, but as President Dieter F. Uchtdorf has pointed out, the Church would not exist without it. [28] He explains that the doctrinally loaded and foundational experience of the First Vision came as the result of Joseph Smith’s critical thought toward existing churches and a desire to know which he should join. Knowing for ourselves if the church that was restored through Joseph Smith’s efforts is truly the “only true and living church” (D&C 1:30) can be done only by following his lead and “ask[ing] of God” (James 1:5). “Asking questions,” President Uchtdorf said, “isn’t a sign of weakness; it’s a precursor of growth.” [29]

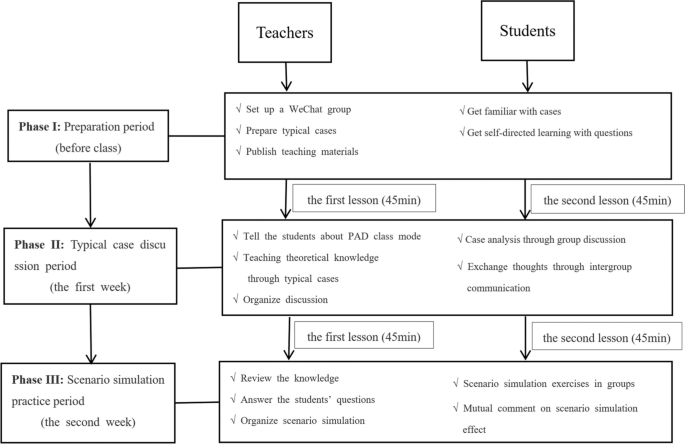

This concept of critically thinking while still acting in faith is illustrated in Alma 32:27–43, when Alma teaches a group of nonbelievers who nonetheless want to know the truth. Table 1 compares Alma’s words with concepts of critical thinking.

Figure 1. Alma and Critical Thinking.

The necessity of exercising faith is a major component of all religion. “For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways, saith the Lord. For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways, and my thoughts than your thoughts” (Isaiah 55:8–9). “Now faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen” (Hebrews 11:1). “I was led by the Spirit, not knowing beforehand the things which I should do” (1 Nephi 4:6). “Look unto me in every thought; doubt not, fear not” (D&C 6:36). The skeptical critic of religion could assert that these statements amount to blind faith or towing the line without a rational or logical reason to do so. Applying critical thinking to such assertions may disclose, ironically, that such approaches are no different than using rational thought.

In Educating Reason , author Harvey Siegel responds to a criticism sometimes waged against critical thinking called the indoctrination objection. His argument provides a means for reconciling faith with logic. In short he observed that critical thinkers have traditionally been opposed to indoctrination of any kind. Over time much has been applied to the perception of, and even the definition of, indoctrination, which now carries with it highly negative connotations of teaching content that is either not true or is taught in such a way that the learner is not provided a way to measure the truthfulness of what is being taught. Yet the fundamental definition of indoctrination is simply to teach.

The indoctrination objection is based on the idea that critical thinkers want to reject all indoctrination, but they cannot do so because critical thinking itself must be taught (indoctrinated). The definition he gives to indoctrination is when students “are led to hold beliefs in such a way that they are prevented from critically inquiring into their legitimacy and the power of the evidence offered in their support; if they hold beliefs in such a way that the beliefs are not open to rational evaluation or assessment.” [32] Siegel delicately defines an indoctrinated belief as “a belief [that] is held non-evidentially.” [33]

It must be acknowledged that children are not born valuing rational thought and evidence; those values must be taught, or indoctrinated. According to Siegel, “If an educational process enhances rationality, on this view, that process is justified.” [34] He later adds that such teaching is not only defensible, but necessary. “We are agreed that such belief-inculcation is desirable and justifiable, and that some of it might have the effect of enhancing the child’s rationality. Should we call it indoctrination? This seems partly, at least, a verbal quibble.” [35]

A teacher is justified in teaching students and a learner is justified in studying if doing so will eventually enhance rationality and if students are allowed to evaluate for themselves what is being taught.

There may even be a period when rationality is put on hold, or the lack of rationality perpetuated, temporarily for the sake of increasing critical thought in the end. This concept of proceeding with learning without first having an established rationale for doing so is the very concept of faith. Just as “faith is not to have a perfect knowledge of things” (Alma 32:21), reasons may not always be understood at first, just as a rational understanding for accepting a teaching is not always given at first. The moment when a learner must accept a teaching without first having a sufficient reason for doing so is faith. Students who continue to engage in the learning process are acting in faith. If the things being taught are true, those things will eventually lead those students to increased rationality and expanded intellect. Such teaching should not detour the student from seeking his or her own personal confirmation. Teaching in a manner that discourages students from establishing their own roots deep into the ground is antithetical to both critical thinking and the purposes of LDS religious education.

Teaching in a way that encourages and invites students to think critically about doctrines reflects not only teaching practices encouraged in today’s religious education within the Church but also doctrines of the Church. The culture and doctrine of the Church seeks to avoid indoctrinating members in the negative or pejorative sense. On the Church’s official Newsroom website is an article explaining what constitutes the doctrines of the Church. Included in that list is this statement: “Individual members are encouraged to independently strive to receive their own spiritual confirmation of the truthfulness of Church doctrine. Moreover, the Church exhorts all people to approach the gospel not only intellectually but with the intellect and the spirit, a process in which reason and faith work together.” [36] More than solely a statement of doctrine on a newsroom website, this concept is bolstered by the words of canonized scripture: “Seek learning, even by study and also by faith” (D&C 88:118). “You have not understood; you have supposed that I would give it unto you, when you took no thought save it was to ask me. But you must study it out in your mind; then you must ask me” (D&C 9:7–8). And finally, from the admonition of Paul, who, after speaking of doctrines, counseled believers to “think on these things” (Philippians 4:8).

The Prophet Joseph Smith addressed the relationship between faith and intellect. “We consider,” he said, “that God has created man with a mind capable of instruction, and a faculty which may be enlarged in proportion to the heed and diligence given to the light communicated from heaven to the intellect; and that the nearer man approaches perfection, the clearer are his views.” [37] In other words, acting in faith, or giving heed and diligence to light communicated from heaven, can enlarge the intellectual faculty and clarify views. Diligence and heed are required in religious education, in which the content being taught is considered irrational by secular society. Amid ridicule by the irreligious, when the intellect is enlarged, the faithful recognize enhanced rationality and clearer views that are never realized by those who are ridiculing. This process continues until full rationality is achieved and the promise of God is fulfilled: “Nothing is secret, that shall not be made manifest; neither any thing hid, that shall not be known” (Luke 8:17). What a promise for a critical thinker!

Critical thinking has the potential to be a powerful tool for educators; that potential does not exclude its use by teachers within the Church. When used appropriately, critical thinking can help students more deeply understand and rely upon the teachings and Atonement of Jesus Christ. The testimony that comes as a result of critical thought can carry students through difficult times and serve as an anchor through crises of faith. As Elder M. Russell Ballard teaches,

Gone are the days when a student asked an honest question and a teacher responded, “Don’t worry about it!” Gone are the days when a student raised a sincere concern and a teacher bore his or her testimony as a response intended to avoid the issue. Gone are the days when students were protected from people who attacked the Church. Fortunately, the Lord provided this timely and timeless counsel to you teachers: “And as all have not faith, seek ye diligently and teach one another words of wisdom; yea, seek ye out of the best books words of wisdom; seek learning, even by study and also by faith.” [38]

Critical thought does not consist of setting aside faith, but rather faith is using critical thought to come to know truth for oneself.

[1] Andrew Davis, “Defending Religious Pluralism for Religious Education,” Ethics and Education 3, no. 5 (November 2010): 190.

[2] Oduntan Jawoniyi, “Religious Education, Critical Thinking, Rational Autonomy, and the Child’s Right to an Open Future,” Religion and Education 39, no. 1 (January 2015): 34–53; and Michael D. Waggoner, “Religion, Education, and Critical Thinking,” Religion and Education 39, no. 3 (September 2012): 233–34.

[3] Waggoner, “Religion, Education, and Critical Thinking,” 233–34.

[4] Duck-Joo Kwak, “Re‐Conceptualizing Critical Thinking for Moral Education in Culturally Plural Societies,” Educational Philosophy and Theory 39, no. 4 (August 2007): 464.

[5] Jawoniyi, “Religious Education,” 46.

[6] Michael Scriven and Richard Paul, quoted in “Defining Critical Thinking,” Foundation for Critical Thinking, http:// www.criticalthinking.org/ pages/ defining-critical-thinking/ 766.

[7] Gospel Teaching and Learning Handbook: A Handbook for Teachers and Leaders in Seminaries and Institutes of Religion (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2012), 39.

[8] Tim John Moore, “Critical Thinking and Disciplinary Thinking: A Continuing Debate,” Higher Education Research & Development 30, no. 3 (June 2011): 261–74.

[9] Ali Mohammad Siahi Atabaki, Narges Keshtiaray, Mohammad Yarmohammadian, “Scrutiny of Critical Thinking Concept,” International Education Studies 8, no. 3 (February 2015): 100.

[10] Dieter F. Uchtdorf, “The Reflection in the Water” (CES fireside for young adults at Brigham Young University, 1 November 2009), https:// www.lds.org/ media-library/ video/ 2009-11-0050-the-reflection-in-the-water?lang=eng#d.

[11] Seminaries and Institutes of Religion, Doctrinal Mastery: Core Document (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2016), 2.

[12] Diane F. Halpern, “Teaching Critical Thinking for Transfer across Domains,” The American Psychologist 53, no. 4 (April 1998): 451.

[13] Jennifer Wilson Mulnix, “Thinking Critically About Critical Thinking,” Educational Philosophy and Theory 44, no. 5 (July 2012): 466.

[14] Dallin H. Oaks, “As He Thinketh in His Heart” (evening with a General Authority, 8 February 2013), https:// www.lds.org/ prophets-and-apostles/ unto-all-the-world/ as-he-thinketh-in-his-heart-?lang=eng.

[15] Rajeswari Mohan, “Dodging the Crossfire: Questions for Postcolonial Pedagogy,” College Literature 19/ 20, vol. 3/ 1 (October 1992–February 1993): 30.

[16] Mohan, “Dodging the Crossfire,” 30.

[17] Mohan, “Dodging the Crossfire,” 30.

[18] Elizabeth Ellsworth, “Why Doesn’t This Feel Empowering? Working through the Repressive Myths of Critical Pedagogy,” Harvard Educational Review 59, no. 3 (September 1989): 297–325.

[19] Ellsworth, “Why Doesn’t This Feel Empowering?,” 301.

[20] Nicholas C. Burbules and Rupert Berk, “Critical Thinking and Critical Pedagogy: Relations, Differences, and Limits,” in Critical Theories in Education , ed. Thomas S. Popkewitz and Lynn Fendler (New York: Routledge, 1999), 45–66.

[21] Thomas S. Monson, in Conference Report, October 1970, 107.

[22] Neal A. Maxwell, “The Precious Promise,” Ensign , April 2004, 45, https:// www.lds.org/ ensign/ 2004/ 04/ the-precious-promise?lang=eng.

[23] Boyd K. Packer, “These Things I Know,” Ensign , May 2013, 8, https:// www.lds.org/ ensign/ 2013/ 05/ these-things-i-know?lang=eng.

[24] Mohan, “Dodging the Crossfire,” 30.

[25] Paulo Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed , trans. Myra Bergman Ramos (New York: Continuum International, 1970).

[26] Donaldo Macedo, introduction to Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed , 11–26.

[27] Gordon B. Hinckley, “Excerpts from Recent Addresses of President Gordon B. Hinckley,” Ensign , October 1996, https:// www.lds.org/ ensign/ 1996/ 10/ excerpts-from-recent-addresses-of-president-gordon-b-hinckley?lang=eng.

[28] Uchtdorf, “The Reflection in the Water.”

[29] Uchtdorf, “The Reflection in the Water.”

[30] Harvey Siegel, “Indoctrination Objection,” in Educating Reason: Rationality, Critical Thinking, and Education (New York: Routledge, 1988), 78–90.

[31] Halpern, “Teaching Critical Thinking for Transfer across Domains,” 451.

[32] Siegel, Educating Reason , 80.

[33] Siegel, Educating Reason , 80.

[34] Siegel, Educating Reason , 81.

[35] Siegel, Educating Reason , 82.

[36] “Approaching Mormon Doctrine,” 4 May 2007, http:// www.mormonnewsroom.org/ article/ approaching-mormon-doctrine.

[37] B. H. Roberts, A Comprehensive History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints , 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1976), 2:8.

[38] M. Russell Ballard, “The Opportunities and Responsibilities of CES Teachers in the 21st Century” (address to CES religious educators, 26 February 2016), https:// www.lds.org/ broadcasts/ article/ evening-with-a-general-authority/ 2016/ 02/ the-opportunities-and-responsibilities-of-ces-teachers-in-the-21st-century?lang=eng&_r=1.

185 Heber J. Grant Building Brigham Young University Provo, UT 84602 801-422-6975

Helpful Links

Religious Education

BYU Studies

Maxwell Institute

Articulos en español

Artigos em português

Connect with Us

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Development and status of moral education research: Visual analysis based on knowledge graph

Jingying chen.

1 School of Marxism, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, China

2 College of Educational Science and Technology, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, China

3 School of Management, Zhejiang University of Technology, Hangzhou, China

Chengliang Wang

4 Department of Education Information Technology, Faculty of Education, East China Normal University, Shanghai, China

Associated Data

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Introduction

Moral education is an educational process of the continuation, construction, and transformation of moral and social norms, and is an important guarantee for the sustainable vitality of human morality.

With bibliometrics applied and VOSviewer and CiteSpace as tools, this paper systematically analyzes 497 articles published in the Social Sciences Citation Index of Web of Science core collection from 2000 to 2022 in the field of moral education research.

By quantifying specific performance information in the field of moral education in terms of authors, journals, organizations and countries, this paper identifies the highly productive authors and organizations, as well as core journals (i.e., the Journal of Moral Education ). A cluster analysis is used to show the knowledge structure, and an evolutionary analysis to present the macro-development trend of moral education.

In this paper, the comprehensive description of the research topics on moral education clarifies the development model and disciplinary prospect of the moral education research, and provides theoretical and practical support for the continuous development and application practice of the moral education research.

1. Introduction

Discussions of morality can be traced back to the ancient Greek period, when Aristotle noted in Nicomachean Ethics that virtue could be divided into intellectual virtue and virtue of character, and that the latter came about as a result of habit, which was people's pursuit of beauty and kindness (Ameriks and Clarke, 2000 ). During the more than two thousand years since then, countless scholars and philosophers have been inspired by Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics and have made in-depth interpretations and explanations of morality and moral phenomena (Kristjánsson, 2006 ). Under the theoretical framework of Aristotelian virtue ethics, this paper attempts to classify and review the development of moral education in K−12 and higher educational systems.

Moral education is a grand concept that involves many disciplines (MacIntyre and Dunne, 2002 ; Kristjánsson, 2021 ). Generally, the essence of moral education is the process by which educators transform certain social thoughts and virtue ethics concepts into the individual thoughts and morals of educatees with certain educational means in social activities and exchanges (Solomon et al., 2001 ). Thus, moral education is mainly the process of moral social inheritance or transmission.

Different from disciplinary education, the value of moral education in practice has been controversial (Peters, 2015 ). Some scholars have questioned the necessity for schools to provide moral education (Stanley, 2003 , 2004 ; Motos, 2010 ); however, more scholars have agreed that schools should supply systematic moral education and have provided corresponding bases for doing so (Hoekema, 2010 ; Wong, 2020 ; Sison and Redín, 2022 ). These scholars have considered that schools have the responsibility and obligation to help students contribute to society in ways that are not limited to the value of social production but that also consider the prosocial value of promoting social goodness from the moral perspective (Hoekema, 2010 ). Meanwhile Sison and Redín ( 2022 ), based on MacIntyre's moral education principle, emphasized the importance of moral education in educational institutions, as an “intrinsic value of an educational institution that instills virtues … [schools should] provide ethical training on par with scientific-objective and technical training” (Sison and Redín, 2022 ; p. 13). Undoubtedly, these disputes have deepened the value and connotation of moral education and have established a close connection between moral education and other disciplines (e.g., business education), which efforts have increased the value placed upon moral education by scholars (Lee, 2022 ). At the same time, the in-depth thinking and scholarly refutation has vigorously promoted moral education studies, transforming the discussion from the necessity of moral education to its contents and purpose.

The battle has been long and arduous for moral education to play an important role in public schools. However, thanks to the efforts of scholars, moral education has become an indispensable part of school education (Leihy and Salazar, 2016 ). Nevertheless, disputes remain on how to implement moral education as well as on its connotation and value (Wong, 2020 ; Lee, 2022 ). The differences remain unclear in the moral educational issues in terms of cultural environments and social backgrounds, and systematic and comprehensive quantitative reviews and analyses are lacking in the moral education literature. Therefore, this paper aims to apply the method of a literature review to systematically organize and further analyze the research on moral education in K−12 and higher educational systems after a comparison and an identification, mainly focusing on the following points:

- We conduct a systematic performance analysis of the research topics on moral education; know the authors, organizations, and countries with high productivity in the field of moral education; and thoroughly uncover the main journals and highly cited studies in this field.

- We reveal the core issues and research status in the field of moral education through a cluster analysis and summarize the research results.

- We provide theoretical and practical support for the subsequent academic research and practice of moral education using evolutionary and keyword-burst analyses to delineate the evolutionary trend of the field.

2. Literature review

Morality can be traced to the origin of human language. In exploring the origin of morality, Tappan ( 1997 ) proposed that morality, as a high-level psychological function, was mediated/regulated by the forms of words, language, and discourse. Per Tappan, as language is a remarkable social medium, the process of social communication and social relations inevitably produce moral function. Tappan also argues that because words, language, and discourse forms are essentially social and cultural phenomena, moral development has always been affected by the specific social, cultural, and historical background in which it occurs.

Morality, as a uniquely human higher mental function, has long been noticed by scholars. In ancient Greece, Socrates incorporated the study of moral ethics into the philosophical system and created his own “philosophy of ethics.” Aristotle further wrote Nicomachean Ethics , which describes the qualities of an ideal or perfect human being: courage, temperance, generosity and magnificence, and possessing a great soul (Ameriks and Clarke, 2000 ). Aristotle provided the most basic definition of virtue ethics, which is considered the systematic origin of virtue ethics (Ferrero and Sison, 2014 ). The morality research has been continuous as human civilized has evolved. For example, Aquinas in the Middle Ages and Machiavelli in the Renaissance built ethical discourse systems (McInerny, 1997 ; Bielskis, 2011 ). However, due to social and historical limitations, the past research on morality has mostly relied on experience, and scholars have mostly discussed morality from the theoretical or philosophical level. Not until the psychologist Wundt established the first psychology laboratory (in 1879) did scholars begin to use modern scientific research methods to discuss morality. Soon thereafter, the research on moral education reached a development peak.

Piaget ( 1932 ) put forward Piaget's Theory of Moral Development based on his observation on children's play, initiating the scientific and systematic research on moral education (Peters, 2015 ). Based on Piaget's research, as well as that of Dewey ( 1959 ) and others, Kohlberg ( 1969 , 1973 ) proposed a more valuable moral theory, namely, that of moral cognitive development, which was later revised and improved. The theory of moral cognitive development states that moral education is intended to help young people learn to justify moral claims correctly and rationally and to develop logical strategies to draw correct inferences from such claims when dealing with moral dilemmas (Kohlberg, 1981 ). Kohlberg's theory attracted great attention in sociology and psychology, and it aroused intense discussion (Mischel, 1971 ; Lickona, 1976 ). Kohlberg's theory was partially overturned in subsequent empirical studies (Kuhn, 1976 ). Nevertheless, as the first systematic and complete theory of moral cognitive development, Kohlberg's theory of moral cognitive development has made an indelible contribution in promoting people's cognition of morality and has successfully caused many scholars to focus on moral education.

The value of Kohlberg's theory of moral cognitive development rested not only in the theory but also in his research method, which provided a perspective for an in-depth understanding of the development of moral thinking. However, because the research design was not entirely rigorous, for example, the subjects used were all male (Aron, 1977 ), the theory also received some criticism and spawned further studies (Gilligan and Attanucci, 1988 ; Rest et al., 1997 ), causing the research on moral development to present a diversified development trend.

The criticism of Kohlberg's moral theory and its development were accompanied by the beginning of the theories of constructivism and humanism. Humanistic theory, in particular, positively affirmed humanity and considered that human nature is kind, rational, positive, and trustworthy. The theory proposes that moral education is required because human environment after birth has many bad factors that hinder the development of human nature's innate potential. However, the basis of moral education is rational, positive, and active humanity, a theory upon which many Chinese and Western scholars have reached an agreement (Slote, 2016 ).

Societal development and changing times have endowed the moral education research with new elements. In the 1980s, a systematic moral education curriculum system emerged in many region's schools (Cheung and Lee, 2010 ). However, the initial practice of moral education was a process of exploration, and the development process was accompanied by many frustrations. For example, in the late 20 th century, many scholars criticized the excessive emphasis placed on moral skills in the process of traditional moral education (Doyle, 1997 ; Lickona, 1999 ). These scholars put forward a new concept of character education to emphasize the specific content (a set of specific values) behind morality: trustworthiness, respect, responsibility, honesty, justice, and fairness (Berreth and Berman, 1997 ; Fenstermacher, 2001 ).