What this handout is about

This handout identifies common questions about drama, describes the elements of drama that are most often discussed in theater classes, provides a few strategies for planning and writing an effective drama paper, and identifies various resources for research in theater history and dramatic criticism. We’ll give special attention to writing about productions and performances of plays.

What is drama? And how do you write about it?

When we describe a situation or a person’s behavior as “dramatic,” we usually mean that it is intense, exciting (or excited), striking, or vivid. The works of drama that we study in a classroom share those elements. For example, if you are watching a play in a theatre, feelings of tension and anticipation often arise because you are wondering what will happen between the characters on stage. Will they shoot each other? Will they finally confess their undying love for one another? When you are reading a play, you may have similar questions. Will Oedipus figure out that he was the one who caused the plague by killing his father and sleeping with his mother? Will Hamlet successfully avenge his father’s murder?

For instructors in academic departments—whether their classes are about theatrical literature, theater history, performance studies, acting, or the technical aspects of a production—writing about drama often means explaining what makes the plays we watch or read so exciting. Of course, one particular production of a play may not be as exciting as it’s supposed to be. In fact, it may not be exciting at all. Writing about drama can also involve figuring out why and how a production went wrong.

What’s the difference between plays, productions, and performances?

Talking about plays, productions, and performances can be difficult, especially since there’s so much overlap in the uses of these terms. Although there are some exceptions, usually plays are what’s on the written page. A production of a play is a series of performances, each of which may have its own idiosyncratic features. For example, one production of Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night might set the play in 1940’s Manhattan, and another might set the play on an Alpaca farm in New Zealand. Furthermore, in a particular performance (say, Tuesday night) of that production, the actor playing Malvolio might get fed up with playing the role as an Alpaca herder, shout about the indignity of the whole thing, curse Shakespeare for ever writing the play, and stomp off the stage. See how that works?

Be aware that the above terms are sometimes used interchangeably—but the overlapping elements of each are often the most exciting things to talk about. For example, a series of particularly bad performances might distract from excellent production values: If the actor playing Falstaff repeatedly trips over a lance and falls off the stage, the audience may not notice the spectacular set design behind him. In the same way, a particularly dynamic and inventive script (play) may so bedazzle an audience that they never notice the inept lighting scheme.

A few analyzable elements of plays

Plays have many different elements or aspects, which means that you should have lots of different options for focusing your analysis. Playwrights—writers of plays—are called “wrights” because this word means “builder.” Just as shipwrights build ships, playwrights build plays. A playwright’s raw materials are words, but to create a successful play, they must also think about the performance—about what will be happening on stage with sets, sounds, actors, etc. To put it another way: the words of a play have their meanings within a larger context—the context of the production. When you watch or read a play, think about how all of the parts work (or could work) together.

For the play itself, some important contexts to consider are:

- The time period in which the play was written

- The playwright’s biography and their other writing

- Contemporaneous works of theater (plays written or produced by other artists at roughly the same time)

- The language of the play

Depending on your assignment, you may want to focus on one of these elements exclusively or compare and contrast two or more of them. Keep in mind that any one of these elements may be more than enough for a dissertation, let alone a short reaction paper. Also remember that in most cases, your assignment will ask you to provide some kind of analysis, not simply a plot summary—so don’t think that you can write a paper about A Doll’s House that simply describes the events leading up to Nora’s fateful decision.

Since a number of academic assignments ask you to pay attention to the language of the play and since it might be the most complicated thing to work with, it’s worth looking at a few of the ways you might be asked to deal with it in more detail.

There are countless ways that you can talk about how language works in a play, a production, or a particular performance. Given a choice, you should probably focus on words, phrases, lines, or scenes that really struck you, things that you still remember weeks after reading the play or seeing the performance. You’ll have a much easier time writing about a bit of language that you feel strongly about (love it or hate it).

That said, here are two common ways to talk about how language works in a play:

How characters are constructed by their language

If you have a strong impression of a character, especially if you haven’t seen that character depicted on stage, you probably remember one line or bit of dialogue that really captures who that character is. Playwrights often distinguish their characters with idiosyncratic or at least individualized manners of speaking. Take this example from Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest :

ALGERNON: Did you hear what I was playing, Lane? LANE: I didn’t think it polite to listen, sir. ALGERNON: I’m sorry for that, for your sake. I don’t play accurately—anyone can play accurately—but I play with wonderful expression. As far as the piano is concerned, sentiment is my forte. I keep science for Life. LANE: Yes, sir. ALGERNON: And, speaking of the science of Life, have you got the cucumber sandwiches cut for Lady Bracknell?

This early moment in the play contributes enormously to what the audience thinks about the aristocratic Algernon and his servant, Lane. If you were to talk about language in this scene, you could discuss Lane’s reserved replies: Are they funny? Do they indicate familiarity or sarcasm? How do you react to a servant who replies in that way? Or you could focus on Algernon’s witty responses. Does Algernon really care what Lane thinks? Is he talking more to hear himself? What does that say about how the audience is supposed to see Algernon? Algernon’s manner of speech is part of who his character is. If you are analyzing a particular performance, you might want to comment on the actor’s delivery of these lines: Was his vocal inflection appropriate? Did it show something about the character?

How language contributes to scene and mood

Ancient, medieval, and Renaissance plays often use verbal tricks and nuances to convey the setting and time of the play because performers during these periods didn’t have elaborate special-effects technology to create theatrical illusions. For example, most scenes from Shakespeare’s Macbeth take place at night. The play was originally performed in an open-air theatre in the bright and sunny afternoon. How did Shakespeare communicate the fact that it was night-time in the play? Mainly by starting scenes like this:

BANQUO: How goes the night, boy? FLEANCE: The moon is down; I have not heard the clock. BANQUO: And she goes down at twelve. FLEANCE: I take’t, ’tis later, sir. BANQUO: Hold, take my sword. There’s husbandry in heaven; Their candles are all out. Take thee that too. A heavy summons lies like lead upon me, And yet I would not sleep: merciful powers, Restrain in me the cursed thoughts that nature Gives way to in repose!

Enter MACBETH, and a Servant with a torch

Give me my sword. Who’s there?

Characters entering with torches is a pretty big clue, as is having a character say, “It’s night.” Later in the play, the question, “Who’s there?” recurs a number of times, establishing the illusion that the characters can’t see each other. The sense of encroaching darkness and the general mysteriousness of night contributes to a number of other themes and motifs in the play.

Productions and performances

Productions.

For productions as a whole, some important elements to consider are:

- Venue: How big is the theatre? Is this a professional or amateur acting company? What kind of resources do they have? How does this affect the show?

- Costumes: What is everyone wearing? Is it appropriate to the historical period? Modern? Trendy? Old-fashioned? Does it fit the character? What does their costume make you think about each character? How does this affect the show?

- Set design: What does the set look like? Does it try to create a sense of “realism”? Does it set the play in a particular historical period? What impressions does the set create? Does the set change, and if so, when and why? How does this affect the show?

- Lighting design: Are characters ever in the dark? Are there spotlights? Does light come through windows? From above? From below? Is any tinted or colored light projected? How does this affect the show?

- “Idea” or “concept”: Do the set and lighting designs seem to work together to produce a certain interpretation? Do costumes and other elements seem coordinated? How does this affect the show?

You’ve probably noticed that each of these ends with the question, “How does this affect the show?” That’s because you should be connecting every detail that you analyze back to this question. If a particularly weird costume (like King Henry in scuba gear) suggests something about the character (King Henry has gone off the deep end, literally and figuratively), then you can ask yourself, “Does this add or detract from the show?” (King Henry having an interest in aquatic mammals may not have been what Shakespeare had in mind.)

Performances

For individual performances, you can analyze all the items considered above in light of how they might have been different the night before. For example, some important elements to consider are:

- Individual acting performances: What did the actor playing the part bring to the performance? Was there anything particularly moving about the performance that night that surprised you, that you didn’t imagine from reading the play beforehand (if you did so)?

- Mishaps, flubs, and fire alarms: Did the actors mess up? Did the performance grind to a halt or did it continue?

- Audience reactions: Was there applause? At inappropriate points? Did someone fall asleep and snore loudly in the second act? Did anyone cry? Did anyone walk out in utter outrage?

Response papers

Instructors in drama classes often want to know what you really think. Sometimes they’ll give you very open-ended assignments, allowing you to choose your own topic; this freedom can have its advantages and disadvantages. On the one hand, you may find it easier to express yourself without the pressure of specific guidelines or restrictions. On the other hand, it can be challenging to decide what to write about. The elements and topics listed above may provide you with a jumping-off point for more open-ended assignments. Once you’ve identified a possible area of interest, you can ask yourself questions to further develop your ideas about it and decide whether it might make for a good paper topic. For example, if you were especially interested in the lighting, how did the lighting make you feel? Nervous? Bored? Distracted? It’s usually a good idea to be as specific as possible. You’ll have a much more difficult time if you start out writing about “imagery” or “language” in a play than if you start by writing about that ridiculous face Helena made when she found out Lysander didn’t love her anymore.

If you’re really having trouble getting started, here’s a three point plan for responding to a piece of theater—say, a performance you recently observed:

- Make a list of five or six specific words, images, or moments that caught your attention while you were sitting in your seat.

- Answer one of the following questions: Did any of the words, images, or moments you listed contribute to your enjoyment or loathing of the play? Did any of them seem to add to or detract from any overall theme that the play may have had? Did any of them make you think of something completely different and wholly irrelevant to the play? If so, what connection might there be?

- Write a few sentences about how each of the items you picked out for the second question affected you and/or the play.

This list of ideas can help you begin to develop an analysis of the performance and your own reactions to it.

If you need to do research in the specialized field of performance studies (a branch of communication studies) or want to focus especially closely on poetic or powerful language in a play, see our handout on communication studies and handout on poetry explications . For additional tips on writing about plays as a form of literature, see our handout on writing about fiction .

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Carter, Paul. 1994. The Backstage Handbook: An Illustrated Almanac of Technical Information , 3rd ed. Shelter Island, NY: Broadway Press.

Vandermeer, Philip. 2021. “A to Z Databases: Dramatic Art.” Subject Research Guides, University of North Carolina. Last updated March 3, 2021. https://guides.lib.unc.edu/az.php?a=d&s=1113 .

Worthen, William B. 2010. The Wadsworth Anthology of Drama , 6th ed. Boston: Cengage.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Story in Literary Fiction

- Literary Fictional Story

- Character in Literary Fictional Story

- Narration of Literary Stories

- Desire and Motivation

- Credibility

- Improving Dialogue

- Characterization Improves Dialogue, Motivates Plot, and Enhances Theme

- Techniques for Excellence in Creating Character in Literary Fiction

- How to Change Fiction Writing Style

- Author’s Attitudes

- How Literary Stories Go Wrong

- Preparing to Write the Great Literary Story

- The Anatomy of a Wannabe Literary Fiction Writer

- Victims as Characters in Literary Fiction

- Information and Literary Story Structure

- 1st person POV in Literary Story

- Top Story/Bottom Story

- Strong Voice and Attention to Time

- Humor and Fiction

- Emotional Complexity in Literary Fiction

- Conflict in Literary Fiction

- What Exactly Is a Character-Based Plot?

- Writing in Scene: A Staple for Reader Engagement in Fiction

- Creating Story World (setting) in Literary Fiction

- Perception in Literary Fiction: A Challenge for Better Narration

- Creating Quality Characters in Literary Fiction

- Mastering the Power of a Literary Fictional Story

- Understanding Empathy

- Q & A On Learning to Think About Narration in Literary Fiction To Write Better Stories

- Incorporating Rhythm in Prose Style

- Fiction Writer’s Manual

- A Simple Life

- Gatemouth Willie Brown on Guitar

- The Wreck of the Amtrak’s Silver Service

- The Indelible Myth

- Inside the Matryoshka

- Speaking of the Dead

- The Necklace

- The Golden Flute

- The Amish Girl

- Dr. Greiner’s Day in Court

- The Cart Boy

- The War of the Flies

- Father Ryan

- Suchin’s Escape

- The Stonecutter

- Facing Grace with Gloria

- The Perennial Student

- The Activist

- Curse of a Lonely Heart

- The Miracle of Madame Villard

- On the Road to Yazoo City

- Captain Withers’s Wife

- The Thirteen Nudes of Ernest Goings

- Crossing Over

- Lost Papers

- Sister Carrie

- Graphic story: Homunculus

- Graphic Story: Reddog

- mp3 Short Stories

- The Surgeon’s Wife

- The Spirit of Want

- Guardian of Deceit

- Art Gallery

- Tour of Duty

- Short Fiction of William H. Coles 2000-2016

- The Art of Creating Story

- Illustrated Short Fiction of William H. Coles 2000-2016

- Facing Grace with Gloria and other Stories

- The Necklace and Other Stories

- The Short Fiction of William H. Coles 2001-2011

- The Illustrated Fiction of William H. Coles 2000-2012

- Lee K. Abbott

- Steve Almond

- John Biguenet

- Robert Olen Butler

- Ron Carlson

- Lan Samantha Chang

- D’Ambrosio

- Peter Ho Davies

- Jonathan Dee

- Fred Leebron

- Michael Malone

- Rebecca McClanahan

- Josh Neufeld / Sari Wilson

- Richard North Patterson

- Michael Ray

- Jim Shepard

- Rob Spillman

- Kirby Wilkins

- Susan Yeagley / Kevin Nealon

- Geoffrey Becker

- Julia Glass

- Lori Ostlund

- Lydia Peelle

- Andrew Porter

- Sylvia D. Torti

- Workshop & Tutorial

- Story in Fiction Today

- About Things Literary

- Opening Lines

- Women Authors

- About Style and the Classics

- The Fiction Well

- SILF Gallery

- Book Reviews

- Narration in Literary Fiction: Making the Right Choices, by William H. Coles

- How Humor Works in Fiction, by William H. Coles

- Books on Writing

- Stories for Study

- SILF – Audio mp3 Download

- Books about Writing

- Book Candy TV

- Workshops – I. Choosing a workshop

- Workshops – II. Making the Experience Valuable

- Workshops – III. How to Critique a Manuscript

- Workshops – IV. Workshops and Literary Agents

- Workshops: V. Top-Ten Rules for Fiction Workshops

by William H. Coles

Drama: core thoughts.

Great fiction is surprise, delight, and mastery. Conflict-action-resolution is the writer’s most essential tool. Dramatic writing is more than just revealing prose. Drama in literary fiction is mainly created through:

- a core story premise,

- unique and fully-realized characterization,

- and logical and acceptable motivation.

Drama in literary fiction is choosing well what information is best for the story and then providing that information predominantly in action scenes.

Suspense: feeling of uncertainty, excitement, or worry over how something will turn out.

Suspense contributes to drama, but it is not the sole element of drama in literary fiction. Suspense in literary fiction is the fear of something happening to a character we like or respect, and the character’s personality affects the outcome of plot elements.

Jane books a flight to New York to plead with her estranged husband. Her pilot arrives too intoxicated to fly the plane, successfully covering up his reduced capacities. Jane boards the plane. The pilot ignores the usual preflight checklist. The fuel tanks are less than a quarter full.

Comment. Fear of something happening to a character, and if we like or respect the character, the suspense is heightened. Yet there is a lack in this plot construction of the character-driven element of literary fiction.

Jane calls her clandestine lover to fly her to New York in his small plane to meet with her estranged husband. She has made her lover distraught at her refusal to give up her efforts to patch her marriage. The lover arrives hung over from drowning his sorrows, and fails to complete a preflight checklist. The plane’s fuel tanks have not been refueled.

Comment. This is not a great story but it does show how character-driven plots differ from circumstantial plots. Note how the second scenario also allows for complexities in the resolution that may reveal more about the characters and contribute to the meaning of the story—say, love is the root of disaster. The lover might sacrifice his life for Jane, or visa versa. Again, character generation of plot to create literary fiction. In popular fiction, the resolution may be simply a plane crash or an emergency landing and the arrest of the pilot.

Withheld information

All stories have withheld information. As an author, you can only tell so much. But why an author withholds information contributes to the quality of the story. And when an author chooses to reveal story information is critical to story success; the expectations are different in genre fiction than in literary fiction.

In melodrama (using stereotypical characters; exaggerated descriptions of emotion; and simplistic conflict, and morality) crucial information is withheld to create suspense for a reader. But it is manipulation of the reader. The reader must accept this manipulation too; this reader knows the narrator knows who killed the rector but will accept not knowing until the end of the story to discover a fact. But in literary fiction, all information crucial for the story (this is an author being true to the story and not using the story) is presented for the sole purpose of engaging the reader. Then the reader becomes involved in (and with) the characters resolving their conflicts—not only in being told what is withheld—and the result is a change in the reader, a realization that nothing in their world will ever be the same because of their involvement in the story.

How story information is used—whether delivered or withheld—is the skeleton of how different authors create their own unique stories. Authors of literary stories must not exploit a reader’s interest and involvement through false handling of story facts. Instead, the reader must become involved in the story action and accept character change–and experience change in themselves.

Literary stories are harder to write and require more intense reading than nonliterary stories. A casual reader, not caring about involvement in the story, will prefer stories based on withheld facts—who murdered whom, for example. This reader (and at times all readers will have this goal) does not want to expend effort to become involved in a literary story. This is how most stories are told and enjoyed today. And it is an admirable skill, for an author, to write to this reader effectively. But literary fiction needs to be an alternative choice for readers in the mood to be involved.

Let’s say you write a story about a pregnant teenage girl traveling alone cross-country for an abortion. For many authors, the story may be about the revelation of who fathered the child. And the discovery of this withheld information will delight many readers.

But you could reveal all the circumstances of the pregnancy. What if it were incest and her father raped her, or what if the gym coach at school had seduced her on the trip to the finals in field hockey. Everything is up front. Now you set forth the structure to bring the reader into how the girl will solve her conflict—an unwanted pregnancy by someone she hates. You will reveal her nature and her capabilities. You will find a premise: forced love destroys a normal life, for example. And you will engender understanding in the reader that enlightens, or changes existing thought.

Drama is action

Most beginning writers do not have the instincts to write stories by creating conflict, action and resolution in a series of scenes that present a story happening that will involve the reader. For most part, beginners simple tell story happenings, often with complicated and inflated prose that is static and boring.

Examples of description and showing

Narrative description (telling):

Paul was jealous that Helen could sing with so much passion that others couldn’t take their eyes away from her as she performed.

In scene (showing):

Helen held the floor-stand microphone with both hands. The piano player played the introduction hunched over the keyboard. Helen took a deep breath and sang with a soft breathy voice, her eyes closed until the refrain when her gaze swept the audience of strangers, all watching her. She sang three verses and smiled at the end without a bow. The crowd applauded. Paul approached Helen as she climbed down off the stage. “I wish I could sing like that,” Paul said. “I don’t have your ear for perfection.”

In scene action and showing should be the major portion of a literary story. But it is still true narrative telling, when condensed–and not as a vehicle for asides, and recall and reflection–can be useful to advance the story efficiently.

A) Narrative telling. (Quick, effective.)

The ship sank.

B) In-scene showing. (More story time, more engaging.)

The ocean liner listed, taking on water through the hole the torpedo made in her portside. The bridge shuddered from two explosions in the engine room, and as the crew struggled to release the lifeboats. And the bow disappeared beneath the surface first, soon followed by the hull.

The feeling of momentum must not be lost in a story. The key is learning how to write with action (see also Momentum).

Examples from A Story in Literary Fiction: A Manual for Writers.

Story examples with dramatic elements: Suchin’s Escape , The Miracle of Madame Villard , The Thirteen Nudes of Ernest Goings .

Click here to donate

Read other Essays by William H. Coles

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

3 thoughts on “ Drama ”

Life saver!!!! :)

Pingback: Assignment 3. Create a Literary Story » Literary Fiction Workshop

My work would not be possible withour your help.

Thank you so much, Rachel

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

13.1: Fiction and Drama - types, terms and sample essay

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 225947

WHAT ARE THE MAIN LITERARY FORMS?

The main literary forms are Fiction, Drama & Poetry .

Although each of the three major literary genres, fiction, drama, and poetry are different, they have many elements in common. For example, in all three genres, authors make purposeful use of diction (word choice), employ imagery (significant detail) and each piece of literature has its own unique tone (emotional quality). An important element that you will find in all three genres is theme, the larger meaning(s) the reader derives from the poem, story, novel or play.

Each of the literary genres is distinguished by its form: Fiction is written in sentences and paragraphs. Poetry is written in lines and stanzas. Drama is written in dialogue.

WHY IS KNOWING THEM IMPORTANT?

As you read different forms of literature you will need to know specialized vocabulary to be able to best understand, interpret, and write about what you are reading. Also, how you approach a literary text and what you focus on will depend on its literary form. For instance, fiction and drama are typically anchored by a reader’s engagement with characters while many poems do not contain a character or tell a story. Therefore, plot is often not a factor in a poem . A poem can be an impression or reflection about a person, a place, an experience or an idea.

HOW DO I APPROACH EACH FORM?

KNOW THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF FICTION:

Short Stories are usually defined as being between 2000-6000 words long. Most short stories have at least one “rounded” (developed and complex) character and any number of “flat” (less-developed, simpler) characters. Short stories tend to focus on one major source of conflict and often take place within one basic time period.

Novellas generally run between 50-150 pages, halfway between a story and a novel.

Novels don’t have a prescribed length. Because they are a longer form of fiction, an author has more freedom to work with plot and characters, as well as develop sub-plots and move freely through time. Characters can change and develop over the course of time and the theme(s) can be broader and more intricate than in shorter forms of fiction.

KNOW THE DIFFERENT TYPES AND STRUCTURE OF DRAMA:

Drama Types

Tragedy – generally serious in tone, focusing on a protagonist who experiences an eventual downfall

Comedy – light in tone, employs humor and ends happily

Satire – exaggerated and comic in tone for the purpose of criticism or ridicule

Experimental – can be light or serious in tone. It creates its own style through experimentation with language, characters, plot, etc.

Musical – can be light or serious. The majority of the dialogue is sung rather than spoken.

Drama Structure

Plays are organized into dialogue, scenes and acts. A play can be made up one act or multiple acts. Each act is divided into scenes, in which a character, or characters, come on or off stage and speak their lines. A play can have only one character or many characters. The main character is the protagonist and a character who opposes him/her is the antagonist .

The plots of plays typically follow this pattern:

- Rising Action – complications the protagonist must face, composed of any number of conflicts and crises

- Climax – the peak of the rising action and the turning point for the protagonist

- Falling Action – the movement toward a resolution

COMMONALITIES OF FICTION AND DRAMA TERMS

Both fiction and drama are typically anchored by plot and character. They also contain literary themes as well as having other elements in common, so we will look at literary terms that can be applied to both of these literary forms.

Fiction and Drama Terms

PLOT: Plot is the unfolding of a dramatic situation; it is what happens in the narrative. Be aware that writers of fiction arrange fictional events into patterns. They select these events carefully, they establish causal relationships among events, and they enliven these events with conflict. Therefore, more accurately defined, plot is a pattern of carefully selected, casually related events that contain conflict. There are two general categories of conflict: internal conflict , takes place within the minds of the characters and external conflict , takes place between individuals or between individuals and the world external to the individuals (the forces of nature, human created objects, and environments). The forces in a conflict are usually embodied by characters, the most relevant being the protagonist , the main character, and the antagonist , the opponent of the protagonist (the antagonist is usually a person but can also be a nonhuman force or even an aspect of the protagonist—his or her tendency toward evil and self-destruction for example). QUESTIONS ABOUT PLOT: What conflicts does it dramatize?

CHARACTERS: There are two broad categories of character development: simple and complex. Simple (or “flat”) characters have only one or two personality traits and are easily recognizable as stereotypes—the shrewish wife, the lazy husband, the egomaniac, etc. Complex (or “rounded”) characters have multiple personality traits and therefore resemble real people. They are much harder to understand and describe than simple characters. No single description or interpretation can fully contain them. For the characters in modern fiction, the hero has often been replaced by the antihero , an ordinary, unglamorous person often confused, frustrated and at odds with modern life. QUESTIONS ABOUT CHARACTERS: What is revealed by the characters and how they are portrayed?

THEME: The theme is an idea or point that is central to a story, which can often be summed up in a word or a few words (e.g. loneliness, fate, oppression, rebirth, coming of age; humans in conflict with technology; nostalgia; the dangers of unchecked power). A story may have several themes. Themes often explore historically common or cross-culturally recognizable ideas, such as ethical questions and commentary on the human condition, and are usually implied rather than stated explicitly.

QUESTIONS ABOUT THEME: To help identify themes ask yourself questions such as these:

SYMBOLISM: In the broadest sense, a symbol is something that represents something else. Words, for example, are symbols. But in literature, a symbol is an object that has meaning beyond itself. The object is concrete and the meanings are abstract. QUESTIONS ABOUT SYMBOLS: Not every work uses symbols, and not every character, incident, or object in a work has symbolic value. You should ask fundamental questions in locating and interpreting symbols:

SETTING: The social mores, values, and customs of the world in which the characters live; the physical world; and the time of the action, including historical circumstances.

TONE: The narrator’s predominant attitude toward the subject, whether that subject is a particular setting, an event, a character, or an idea.

POINT OF VIEW: The author’s relationship to his or her fictional world, especially to the minds of the characters. Put another way, point of view is the position from which the story is told. There are four common points of view:

- Omniscient point of view —the author tells the story and assumes complete knowledge of the characters’ actions and thoughts.

- Limited omniscient point of view —the author still narrates the story but restricts his or her revelation—and therefore our knowledge—to the thoughts of just one character.

- First person point of view —one of the characters tells the story, eliminating the author as narrator. The narration is restricted to what one character says he or she observes.

- Objective point of view —the author is the narrator but does not enter the minds of any of the characters. The writer sees them (and lets us see them) as we would in real life.

FORESHADOWING: The anticipation of something, which will happen later. It is often done subtlety with symbols or other indirect devices. We have to use inferential thinking to identify foreshadowing in some stories, and often it occurs on an almost emotional level as we're reading, leading us further into the heart of the story.

EXPOSITION : The opening portion of a story that sets the scene, introduces characters and gives background information we may need to understand the story.

INTERIOR MONOLOGUE : An extended exploration of one character's thoughts told from the inside but as if spoken out loud for the reader to overhear.

STREAM OF CONSCIOUSNESS: A style of presenting thoughts and sense impressions in a lifelike fashion, the way thoughts move freely through the mind, often chaotic or dreamlike.

IRONY: Generally irony makes visible a contrast between appearance and reality. More fully and specifically, it exposes and underscores a contrast between (1) what is and what seems to be, (2) between what is and what ought to be, (3) between what is and what one wishes to be, (4) and between what is and what one expects to be. Incongruity is the method of irony; opposites come suddenly together so that the disparity is obvious.

CLIMAX: The moment of greatest tension when a problem or complication may be resolved or, at least, confronted.

RESolution, CONCLUSION or DENOUEMENT ("untying of the knot"): Brings the problem to some sort of finality, not necessarily a happy ending, but a resolution.

Using the literary vocabulary and questions, let’s analyze a literary text.

Read the memoir, “Learning to Read,” by Jessica Powers which can be located in Chapter 1: Critical Reading in the “Faculty-Written Texts” section. Powers employs many of the elements of fiction in this autobiographical piece. When you have finished reading, answer the questions below.

Questions about plot :

- What is the main conflict in the story?

- What causes the conflict?

- Is the conflict external or internal?

- What is the turning point in the story?

- How is the main conflict resolved?

Questions about character:

- Is the main character simple or complex? Explain.

- What are the traits of the main character? Make a list.

- Does the main character change? Describe.

- What steps does she go through to change? Make a list.

- What does she learn? Describe.

- Does the main character experience an epiphany? Describe.

Questions about theme:

- What does the story show us about human behavior?

- Are there moral issues raised by the story? Describe.

- What does the story tell us about why people change?

Example A sample essay written on fiction (a short story)

Last Name 1

Student Name

Professor name

English 110

Women, Are You Living for Yourself or for a Man?

A woman in her 40s who never marries or has children is often met with concern, suspicion or pity and there is even a pejorative word for her, "spinster." In contrast, a man in his 40s who never marries or has children is often viewed positively as a bachelor or a playboy or simply as a free man. This double standard forces many women to live for others first and themselves second, something a man is never asked to do. This was especially true in the early 1900s when women were discouraged from having careers outside of the home and were encouraged to have their primary focus in life be caring for their husband, children and home. Mary E. Wilkins Freeman the author of the short story "A New England Nun," presented women from this era with a story of a woman who rebels against the usual adherence to duty, submission, and self-sacrifice. Through the story of her main character Louisa, Freeman offers an alternative to the role American society had expected women to play. Freeman proves there are advantages to be had for women who break the bonds of socially created gender roles by declining to get married and have children, and instead create a life entirely their own, one in which they are not tied down by the needs of others and advantageously avoid the negative influence brought on by the judgement and expectations of a man.

Although Louisa's engagement promised security and stability, it is immediately clear that the return of Louisa's long-awaited fiance threatens to destabilize the ordered and serene life she had created for herself. Because her finace Joe Dagget had to work overseas for 14 years, Louisa had a taste of something not many women of her time experienced, socially approved independence. During this time, Louisa became quite content with her solitary life. Louisa developed a passion for caring for her home and did chores because it pleased her, which is a far cry from the feelings most women in that era experienced in caring for a house, husband and children. Upon her fiance's return, the presence of masculinity upsets the ideal environment Louisa had established in her life and Freeman illustrates this when the couple's first reunion ends in chaos. As Joe is leaving Louisa's house, he stumbles over a rug which knocks over her basket of sewing supplies, and as the yarn spools helplessly unravel across the floor Louisa says stiffly to Joe, "Never mind, I'll pick them up after you're gone" (65). As her yarn unravels, Louisa gets a preview of what Joe's presence will do to her life. Louisa's meticulous care for her home and her appreciation for cleanliness and order shows that having a place of her own and maintaining her preferred surroundings gave her a sense of price and placed power and control over her life in her own hands.

Another way marriage threatens Louisa is that it would make her dependent. A stipulation for marriage during the early 20th century that would have had a devastating impact on Louisa's life was that all her treasured possessions would legally become her husband's property. Louisa discovered many of her passions whilst living independently. Among those were her china set that she used daily, her photo albums, her books, her sewing supplies that she grew to call good friends, her dog Caesar, and most of all her home. In addition to the transfer of possessions following matrimony, women also no longer had control over what they did with their time. In Louisa's case, she would be forced to become a servant of both her new husband, his mother, and their future children. Her time would no longer be her own as she would become the cook, laundress, seamstress, and caretaker for others. The independence that Louisa cherished would be replaced with servitude, duty, and dependence on a man she barely knew.

The predominate message for women, yet not for men, is that their lives will be incomplete, empty, and without purpose if they do not marry and have children, trapping some women in miserable lives. Without socially accepted alternatives, some women get married and have children who would be better off doing neither. Shouldn't a person want to take on the challenging task of caring for others rather than producing more unhappy marriages and checked out parents who feel distanced from and resentful of their children? The pressures, however, on women to marry and have children back then persist today, and this needs to change. The ending that Freeman created in her story proposes that some women should choose to live for themselves. After Louisa breaks off her engagement, she sees the endless possibilities for her future, "She gazed ahead, through a long reach of future days strung together like pearls on a rosary, every one like the others, and all smooth and flawless and innocent, and her heart went up in thankfulness" (71). At this point, Louisa is no longer marrying Joe, but she does not perceive life without love or intimacy as any terrible loss. Instead, she sees a life full of freedom and potential.

We mustn't continue to limit the potential of women by making them conform to limited gender roles. An article written by the UN Women's Secretary General for International Women's Day 2017 claims that, "Around the world, tradition, cultural values and religion are being misused to curtail women's rights, to entrench sexism and defend misogynistic practices." Even though women in the 21st century have deviated from being dependent on the financial stability provided by a man, conventional views continue to limit their growth by assigning them to feminine type jobs and denying them leadership positions. In addition to Inequality in the workplace, women are often juggling both work-life and domestic-life. Louisa's story stresses the importance of being a strong woman in a restrictive society and emphasizes the previous rewards that are yours to possess when you alter your path based on your own decisions. The worth of a women should not be judged by marriage and children because the worth of man certainly is not.

Works Citied

Freeman Wilkins, Mary E. "A New England Nun." Great Short Stories by American Women, edited by

Candace Ward, Mineola, N.Y.: Dover Publications, 1996, pp. 61-71.

Guterres, Antonio. "UN Secretary-General's Message for International Women's day." UN Women, 6

Mar. 2017, http://www.unwomen.org/en/news/stori...omens-day-2017 .

How to Dramatize Real Life in Your Writing

by Birgitte Rasine | 10 comments

How do you dramatize non fiction? Isn’t real life already wild and crazy enough? And isn’t that why we have fiction in the first place, so that we can be superheroes and E.S.C.A.P.E. our dull routine realities?

Yes, and yes, BUT. The role of literature, in my and many other authors’ humble yet strong opinion, is, in addition to the obvious benefit of enjoyment and entertainment, to reflect social trends and preserve cultural ideals. To inform, inspire, and innovate. The stories we write and read shape our culture and society, our minds and our lives. This is why I insist with the ferocity of a Category 5 hurricane on quality, beauty, and impact.

Remember when we discussed why we write ? The reason I write is to open minds—including my own. For me, the most potent way to do that is by mixing up fiction and real life.

I'm no good at academic theories—I prefer living breathing examples. So let me tell you about The Visionary .

Image courtesy of LUCITÀ Publishing

Pack It Tight and Give It Time

The Visionary is, to date, my most complex, creative, and insanely challenging work. It's several decades of thought and observation about nearly every aspect of the human experience vacuum-packed into a 12,000-word sardine can. I dramatize only a little.

Short version: It’s a work of dramatic realism (see below for definition) written in poetic prose that explores the nature and role of time, light, and the human capacity for vision, and exhorts us to re-imagine and reconfigure the habits and systems that have rendered us completely blind to our own potential.

Short short version: It's an inspirational critique of modern Western society. (Note how “inspirational” tempers “critique”—the message is, yep we've royally messed up ourselves, our society, the economy, and the planet, but there's hope!)

Long version: You gotta read the book . If you can summarize it better than me I'll send you a box of dark chocolate truffles.

It took me twelve years to finish it, because it took that long for me to amass enough experience, acquire enough knowledge, and attain enough insight and inspiration to be able to craft metaphors powerful and evocative enough for the expansive range of concepts and ideas that this work covers. It took that long to experience and then interweave the real life events that inspired the story among those metaphors, and to give it symmetry and structure that not only made sense and delivered a narrative, but also read and felt poetic. Plus I was busy living all that real life stuff.

Choose Your Poison (or, Form vs Function)

Dramatization takes varied and multiple forms. Docudramas are dramatizations in film or video. In literature we have realism in general, which depicts actual life. We also have magic realism , made famous by Gabriel García Márquez , where magical elements abound in an otherwise realistic environment or world. There’s realistic fiction , which is believable or plausible fiction (zombie, alien romances, and 50 shades of anything need not apply). You might have also heard of the non fiction novel , which employs historical figures and events intertwined with fictional elements; it can also be an autobiographical or semi-autobiographical novel.

When I was searching for the appropriate genre to label The Visionary , I found myself constantly falling through the cracks. So I employed a rarely used term: “dramatic realism.” It's apparently so rare it's not anywhere in the usual literary genre lists you'll find. The one place I found that does list the term couldn't bring itself to express it in a single sentence. So I did. I define dramatic realism as

“literature or creative writing that reflects reality or the real world the way we experience it with all of its subjective implications, and expresses that experience in a dramatic or dramatized, although not fantastical or magical, manner.”

Whew. At least it's one sentence.

Mind you, I put the label on the work after the fact. You don't—ok, some might but I don't—set out to tell a story by selecting the style first. The form needs to fit the function. In this case, had I “chosen” any other genre, it would have either come out reading like an accidental offspring of Dalí and Shakespeare or it would have made Marcel Proust look like Augusto Monterroso .

Plot Your Path and Don't Forget to Live

Bottom writer's line, you have to develop a gut-level feel for the genre and style that your stories call for, regardless of the subject matter or plot. The way to do that is to become familiar with all of the genres and subgenres that have come before you, and to play with them, the way you would in a sandbox. Especially when you're mixing salt and freshwater—fiction and real life, as it were.

My personal advice is, be clear, very clear, on what you are trying to dramatize and why. Dig deep. What is it deep inside that's making you want to express [fill in the blank]? Who are you writing for and why? How do you wish to grow as a writer through this work?

Above all, remember it IS real life you're dramatizing, so that's the first step. Get out there, update your passport, log out of social media, and experience life in all of its maddening, beautiful, intricate simplicity.

And then tell us about it.

What aspect of life have you always wanted to dramatize?

Choose an element of real life or the real world around you and write about it in dramatic realism.

And if you're feeling dramatically unreal, you can write about that too. Just be sure to use some kick-ass metaphors.

Birgitte Rasine

Birgitte Rasine is an author, publisher, and entrepreneur. Her published works include Tsunami: Images of Resilience , The Visionary , The Serpent and the Jaguar , Verse in Arabic , and various short stories including the inspiring The Seventh Crane . She has just finished her first novel for young readers. She also runs LUCITA , a design and communications firm with her own publishing imprint, LUCITA Publishing. You can follow Birgitte on Twitter (@birgitte_rasine), Facebook , Google Plus or Pinterest . Definitely sign up for her entertaining eLetter "The Muse" ! Or you can just become blissfully lost in her online ocean , er, web site.

Join over 450,000 readers who are saying YES to practice. You’ll also get a free copy of our eBook 14 Prompts :

Popular Resources

Book Writing Tips & Guides Creativity & Inspiration Tips Writing Prompts Grammar & Vocab Resources Best Book Writing Software ProWritingAid Review Writing Teacher Resources Publisher Rocket Review Scrivener Review Gifts for Writers

Books By Our Writers

You've got it! Just us where to send your guide.

Enter your email to get our free 10-step guide to becoming a writer.

You've got it! Just us where to send your book.

Enter your first name and email to get our free book, 14 Prompts.

Want to Get Published?

Enter your email to get our free interactive checklist to writing and publishing a book.

✍️ Dramatic Short Story Prompts

Curated with love by Reedsy

We found 47 dramatic stories that match your search 🔦 reset

A long-standing feud erupts during a funeral or wedding.

A plane that's been missing for years suddenly lands at a major airport., subscribe to our prompts newsletter.

Curated writing inspriation delivered to your inbox each week.

A woman drops her wallet on the street, and it falls open. You pick it up and are about to return it to her when you notice a strange picture inside.

As the floor trembles and the walls shake, you know there is only one way to survive., as the sun set, the desert wasteland glowed an eerie red., as you ride your motorcycle off into the sunset, you see something unexpected on the horizon., by the time this party is finished, three people's lives will be changed forever..

Find the perfect editor for your next book

Over 1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Win $250 in our short story competition 🏆

We'll send you 5 prompts each week. Respond with your short story and you could win $250!

Learn more about Reedsy.

The word count limit is 1k - 3k words and the deadline is every Friday.

Bring your short stories to life

Fuse character, story, and conflict with tools in the Reedsy Book Editor. 100% free.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

Home — Essay Samples — Literature — Short Story — Dramatic And Verbal Irony In The Story of an Hour

Dramatic and Verbal Irony in The Story of an Hour

- Categories: Kate Chopin Short Story The Story of An Hour

About this sample

Words: 726 |

Published: Jan 21, 2020

Words: 726 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

In the essay analyzing Kate Chopin's short story "The Story of an Hour," the author delves into the use of irony as a literary technique to support the central theme that "nothing is as it seems." The essay highlights how Chopin employs both situational and verbal irony to underscore the transformation of the protagonist, Mrs. Mallard.

Situational irony is exemplified by Mrs. Mallard's initial reaction to the news of her husband's death. Instead of the expected grief, she experiences an inexplicable sense of happiness. Verbal irony comes into play when Mrs. Mallard exclaims, "Free, Free, Free!" and carries herself with an air of victory. This contrast between her emotional response and societal expectations adds depth to the narrative.

The narrative takes a significant turn with dramatic irony when it is revealed that Mr. Mallard is alive, which leads to Mrs. Mallard's shock and eventual death, attributed to "heart disease-of joy that kills." This twist underscores the story's theme that appearances can be deceiving, challenging the conventional understanding of the characters and their emotions.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Literature

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 999 words

3 pages / 1536 words

1 pages / 2270 words

1.5 pages / 724 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Short Story

Maupassant, Guy de. 'All Over.' Short Stories. Project Gutenberg, www.gutenberg.org/files/3090/3090-h/3090-h.htm#link2H_4_0001.Brigham, John C. 'Perception and Reality: A Historical and Critical Study.' Harvard Theological [...]

Tellez, Hernando. 'Lather and Nothing Else.' Translated by Donald A. Yates, Duke University Press, 2008.Zikaly, Peter. 'You have to make a choice, even when there is nothing to choose from.' (Note: No specific source found, [...]

Poe, Edgar Allan. 'The Fall of House of Usher.'Cortázar, Julio. 'House Taken Over.'Quiroga, Horacio. 'The Feather Pillow.'

Tan, Amy. 'Rules of the Game.' The Joy Luck Club, Vintage Books, 1989, pp. 158-166.

At the beginning of Boccaccio’s Decameron, both the male and female narrators hesitate to discuss the seemingly lewd topic of sexual relations. On Day I, the Florentines discuss various topics, yet only one narrator is brave [...]

Written by master realist Anton Chekhov, "Misery" is the story of an old man’s grief for having lost his son. He keeps looking for somebody with whom to talk about the death of his child. Throughout, the use of the old man's [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Pitch Deck Teardown: Plantee Innovations’ $1.4M seed deck

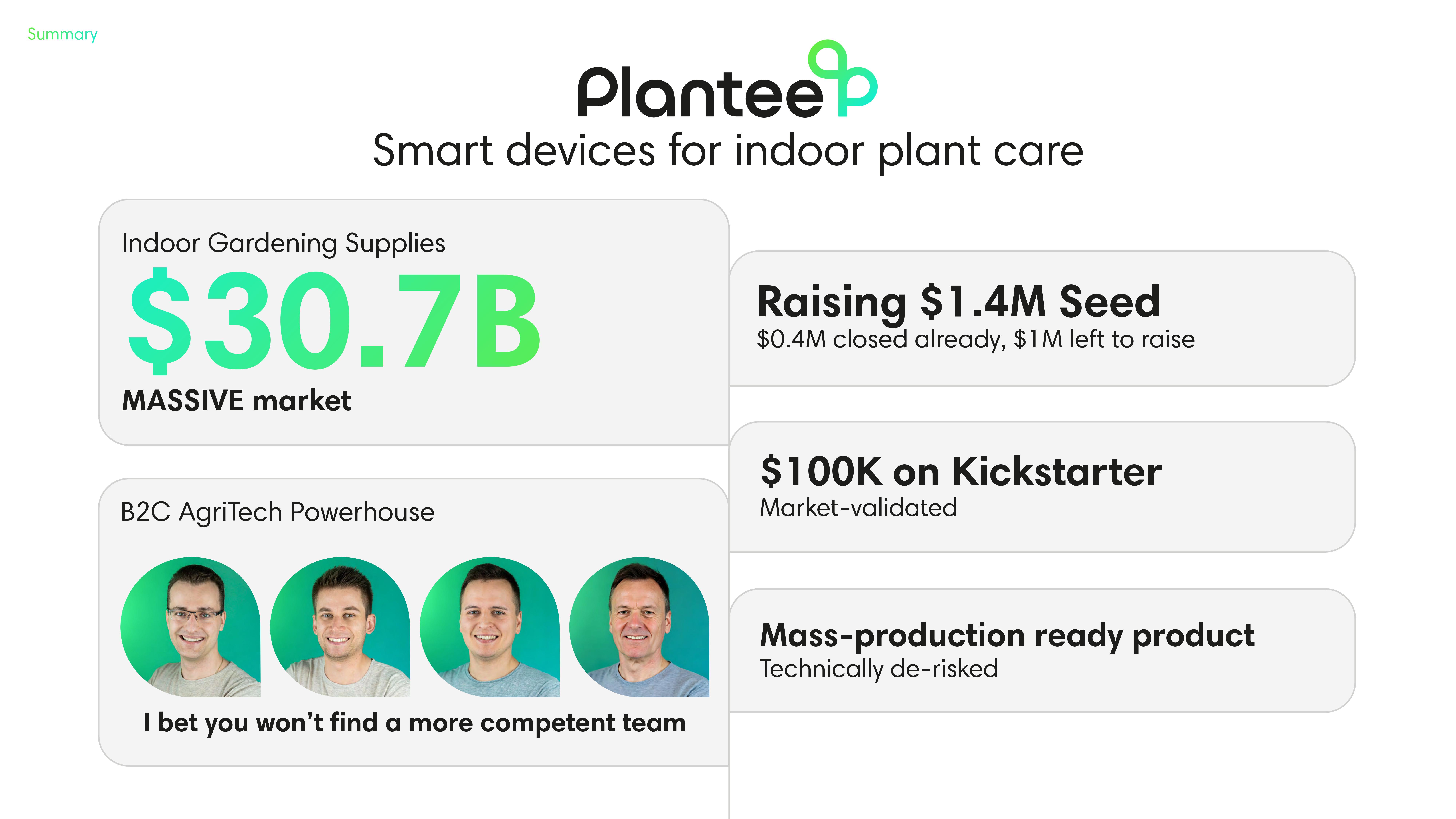

It’s rare that I come across a pitch deck that ticks almost all the boxes. It’s so good, in fact, that I fed Plantee’s deck into an AI tool I built , and it determined there was a 97.7% chance that Plantee would raise money. This tool generally determines that only about 7.5% of all pitch decks are up to scratch, so Plantee’s is positively off the charts.

What the robots didn’t pick up, however, was that Plantee’s Kickstarter campaign was canceled before it was completed, and there are a few other confusing bits as well. Let’s dive in to see what works, and what could be improved.

We’re looking for more unique pitch decks to tear down, so if you want to submit your own, here’s how you can do that .

Slides in this deck

- Cover slide

- Summary slide

- Advisers and investors slide

- Mission slide

- Market validation slide

- Problem slide

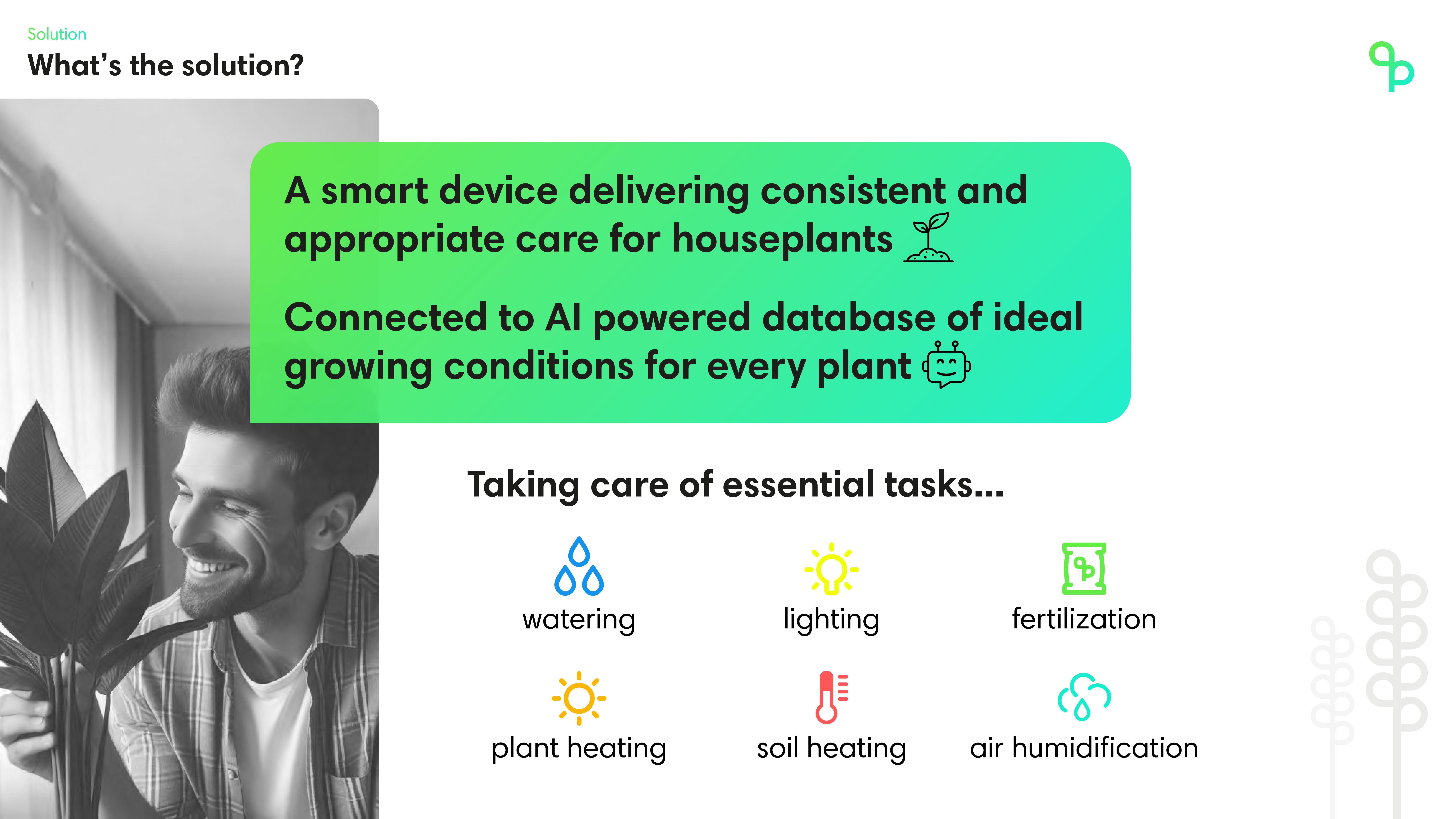

- Solution slide

- Product slide

- Competitive landscape slide

- Traction slide

- Target customer slide

- Market size slide

- Pricing & unit economics slide

- Vision slide

- Ask and Use of Funds slide

- Operating plan slide

- Closing slide

- Appendix slide I: Products in development

- Appendix slide II: Sources and references

Three things to love about Plantee’s pitch deck

It turns out that Plantee’s team has been reading my Pitch Deck Teardowns very carefully indeed, and it shows. The company includes tons of details in its deck.

That’s how you do an introduction!

Slides 1 and 2 together (Slide 1 is at the top of the article) set the stage for an investor to 100% understand the what, why and how of the company:

[Slide 2] A one-page summary to applaud. Image Credits : Plantee

Gotta love a good tech solution

I’ll be the first to admit that I’m a raging nerd, and I love a good gadget. I also love plants; I have dozens all over my apartment, and I can keep most of them alive. As outlined, I love Plantee’s approach to foolproofing plant parenthood.

[Slide 8] Technology, AI and happy plants. Image Credits : Plantee

On the one hand, that’s a relief. On the other, perhaps I’m just a naive and novice plant daddy, but it left me a little confused. I’ve never heard anyone mention air humidification and soil heating. I could be persuaded that these things make a difference, sure, but I’m definitely curious to what degree it’s worth worrying about.

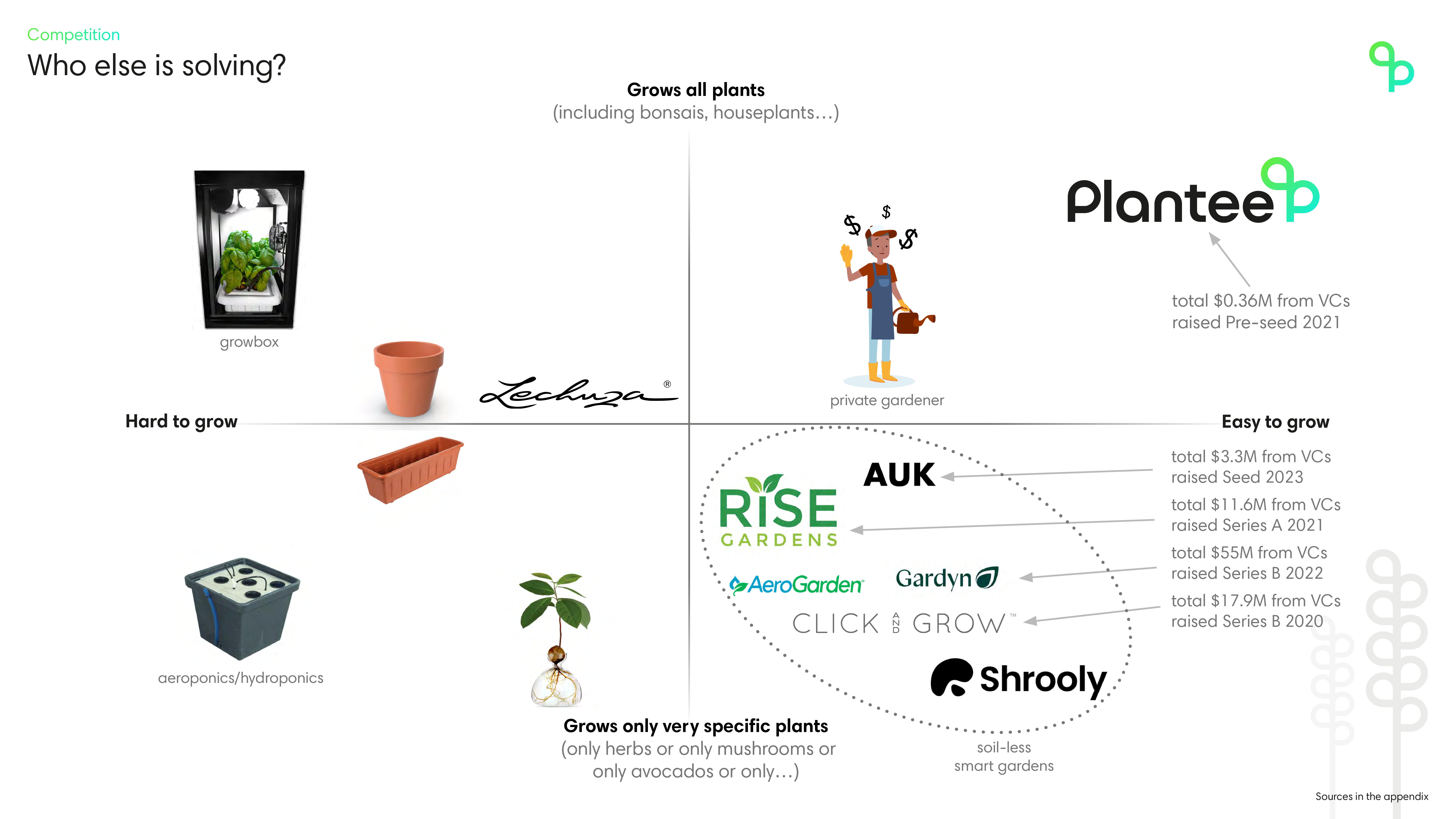

A good competitive landscape

This is a market that doesn’t have many competitors. Seen through one lens, that’s a good thing: It means that there’s a thriving market, and Plantee can see what its competitors are doing well or poorly and position itself accordingly.

[Slide 10] That’s a lot of competitors. Image Credits : Plantee

The other question I have is whether this dichotomy even makes sense. If someone plants a bonsai — a specific use case pitched by the Plantee team — they’re probably not going to repot the plant, which is an interesting challenge. If you’re positioning yourself in the market as a “you can grow anything,” I would assume that you’d want to replant occasionally. The little bonsai tree, however, can grow up to 800 years , so it’s hard to claim that the “grows all plants” argument is that strong of a selling point.

Three things that Plantee could have improved

On first impression, the Plantee deck is pretty extraordinary, and the AI tool gave it a 97% chance of success. As a human investor, I’m less convinced, and I disagree with the AI for a few crucial reasons.

Does it make sense as a product?

I love a good indoor growing system, and there have been many that tried (and failed) in this space. GROW raised $2.4 million back in 2017, before it eventually ground to a halt. I reviewed the $1,000 Abby a couple years ago, which, like Plantee, had pre-sold $100,000 worth of products on Kickstarter, and it was pretty awful . I’ve also built my own hydroponics system for under $150 , which is obviously a lot more work, but it shows that these types of systems don’t have to be expensive.

We review Abby, a sleek one-plant weed farm for your apartment

Plantee is up against some pretty formidable competition. At the low end, for just $40 you can pick up a pod-based hydroponic system. If you want to spend a bit more, Click & Grow has your back . Rise Gardens recently raised a $9 million round . People kill house plants all the time, but most of them are pretty easy to take care of. If you need some help, a quick Google search for “AI plant growing app” gives you dozens of options, most of them free.

My biggest challenge with the Plantee deck isn’t what’s there, but it’s what’s missing: wider context. If you take all the company’s claims at face value, it’s an extraordinary opportunity. However, zoom out a little, and talk to a few plant lovers, and you realize that perhaps there isn’t as big a gap in the market as one might think. It seems that the inherent assumption in the Plantee story is that people who are bad at plants will spend $1,400 on a fancy automatic plant pot.

I’d argue that’s a fallacy and that people who are bad at plants instead get a kitten, or take up watercolors, or get a plastic plant, before they’re wiling to invest four months of car payments on a fancy piece of tech.

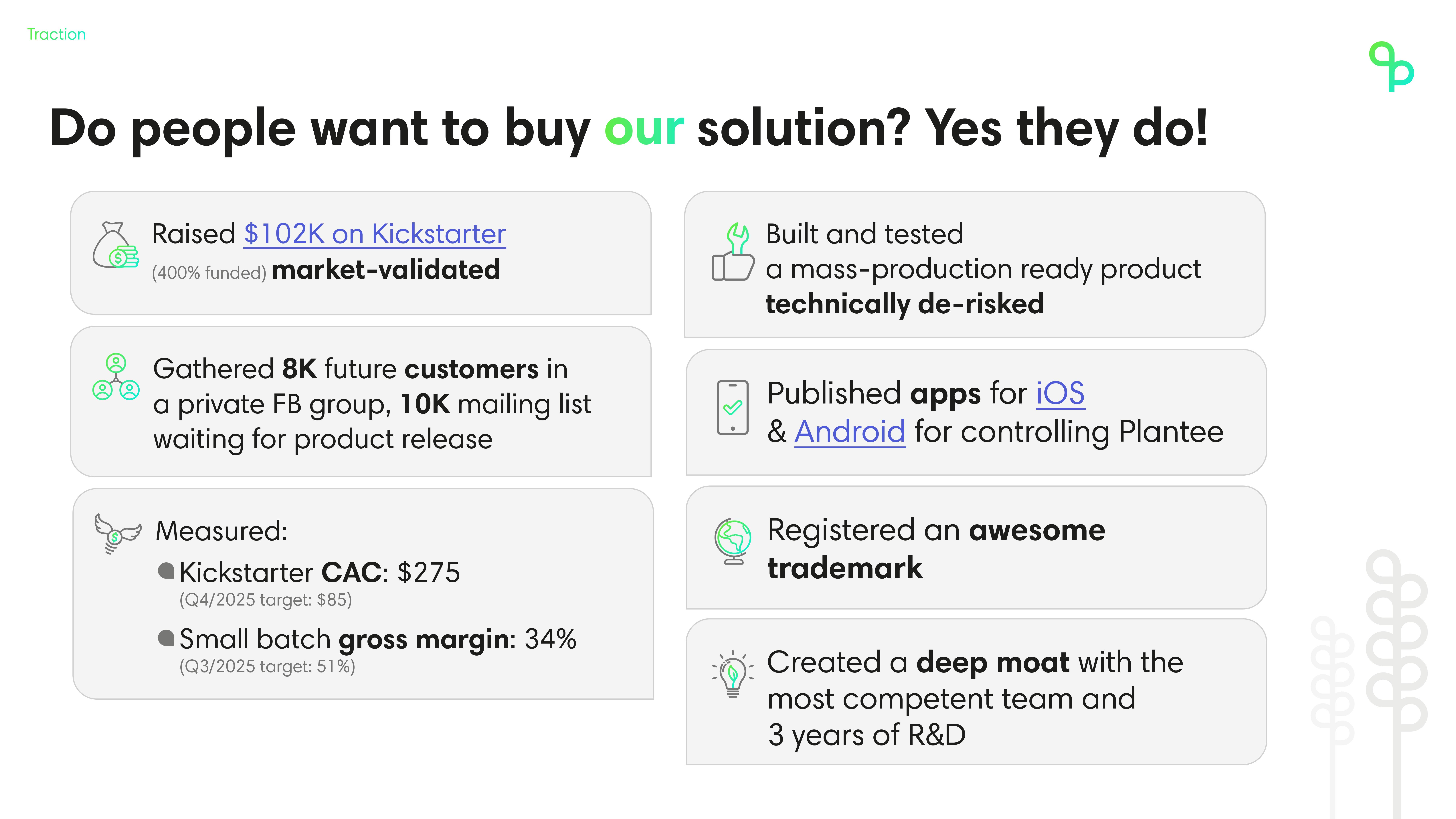

So what happened to that Kickstarter campaign?

[Slide 11] Plantee is arguing front and center that its Kickstarter campaign is part of the market validation. But there’s a catch. Image Credits : Plantee

What happened? Image Credits : Screenshot from Kickstarter

That puts the Plantee team in a strange position: It claims that the Kickstarter campaign proves market validation. And that might be true: The company says it was able to attract its preorder customers for a CAC of $275. By selling 109 units, basic math dictates that the company spent about $30,000 to make $100,000 worth of sales. That’s not too shabby, assuming that there’s enough margin in the product to make that customer acquisition cost make sense.

The problem, however, is that the company doesn’t mention anywhere in the pitch deck that the campaign was canceled, and it doesn’t discuss why it was canceled. It could argue that it never intended to deliver on the Kickstarter campaign and that it was just a marketing test to help confirm whether there was a market for this sort of thing.

I’m not sure that makes sense. Before Plantee’s campaign, EcoQube ( $300,000 funded in 2019 ), GroBox ( $70,000 funded in 2019 ), Herbert ( $280,000 funded in 2019 ) and dozens of others had already been successful, and it’s not fully clear what Plantee learned from this exercise. Since then, a bunch of others have run successful Kickstarter campaigns ( Herbstation , MarsPlanter , GrowChef ).

Put simply, I’m struggling to figure out how the Kickstarter campaign fits into the overall narrative, and by seeming to skirt the issue within the deck, Plantee isn’t doing itself any favors. Perhaps I’m being painfully sensitive after one of my own Kickstarter campaigns went down in flames a decade ago , and eventually took the whole company with it , but personally, I’d include a “so, what happened with the Kickstarter” slide in the appendix to get ahead of that part of the story. Bad news should travel fast.

A little on the dramatic side

I love some good storytelling, don’t get me wrong, but parts of this pitch deck seem to have lost all perspective. Phrases like “never lose another green child,” “It started when my good friend died,” and “stress affecting the mental health of growers” are undoubtedly powerful and emotionally charged, but to those of us who’ve lost a good friend, had serious mental health challenges, or actually lost a human child, it seems pretty tasteless to compare the vast and almost unbearable pain of that with losing a house plant.

[Slide 5] I’m sorry for your loss, Ondra, but this is bordering on bad taste. Image Credits : Plantee.

The full pitch deck

If you want your own pitch deck teardown featured on TechCrunch, here’s more information . Also, check out all our Pitch Deck Teardowns all collected in one handy place for you!

COMMENTS

Drama Reflection Essay (Author Unknown) 4. Kitchen Sink Dramas by Rodolfo Chandler. 5. Love Yourself, Not Your Drama by Crystal Jackson. 6. Shakespeare's Theater: An Essay from the Folger Shakespeare Editions by Barbara Mowat and Paul Werstine. 5 Prompts for Essays About Drama. 1.

This handout identifies common questions about drama, describes the elements of drama that are most often discussed in theater classes, provides a few strategies for planning and writing an effective drama paper, and identifies various resources for research in theater history and dramatic criticism. We'll give special attention to writing ...

Table of contents. Step 1: Reading the text and identifying literary devices. Step 2: Coming up with a thesis. Step 3: Writing a title and introduction. Step 4: Writing the body of the essay. Step 5: Writing a conclusion. Other interesting articles.

Tragic Dramatic Literature. Tragic drama may be defined as a simulation of reality which appears to be somber, with an immerse magnitude, which is expressed to induce a sense of fear or pity with an embellishment of the [...] Pages: 4. Words: 986. We will write a custom essay specifically for you.

Extra Facts. 1) 'Hamlet' was based on an older legend of Amleth. 2) 'Hamlet' is the second most filmed story in the world and the most produced play in the world. 3) Some believe that the play was not written by Shakespeare.

Dramatic Irony in Trifles. Introduction. In Susan Glaspell's play, Trifles, the use of dramatic irony plays a significant role in conveying the story's themes and enhancing the audience's understanding of the characters and their motivations. Dramatic irony occurs when the audience possesses crucial information that the characters are unaware ...

Dramatic writing is more than just revealing prose. Drama in literary fiction is mainly created through: a core story premise, unique and fully-realized characterization, and logical and acceptable motivation. Drama in literary fiction is choosing well what information is best for the story and then providing that information predominantly in ...

Write about a character having a spiritual experience at a concert or a nightclub. Dramatic - 28 stories. Write about a character unknowingly experiencing a "sliding doors" moment. Write your story in two halves; what could have been, and what actually happened. Dramatic - 65 stories.

Lord of The Flies. The Crucible. The Story of An Hour. Langston Hughes. Things Fall Apart. Their Eyes Were Watching God. Write your best essay on Drama - just find, explore and download any essay for free! Examples 👉 Topics 👉 Titles by Samplius.com.

Fiction. KNOW THE DIFFERENT TYPES OF FICTION: Short Stories are usually defined as being between 2000-6000 words long. Most short stories have at least one "rounded" (developed and complex) character and any number of "flat" (less-developed, simpler) characters. Short stories tend to focus on one major source of conflict and often take place within one basic time period.

101 Drama Story Prompts. 1. Long-lost twins find each other. 2. A father deals with the death of his whole family after a tragic accident. 3. A mother struggles with grief after losing her oldest child. 4. A recently divorced man returns to his hometown and reconnects with his childhood sweetheart.

PRACTICE. Choose an element of real life or the real world around you and write about it in dramatic realism. And if you're feeling dramatically unreal, you can write about that too. Just be sure to use some kick-ass metaphors. About the author.

At their core, standard family drama essays are no different from other forms of academic work. They have to rely on the five-paragraph structure and contain an introduction and conclusion. However, in between, there is the space to tell a whole story. Below, you will learn how to develop a dramatic story in an essay. 1. Brainstorm for ideas.

Dramatic Appeal - Essay Sample. When I walked through my front door, the first thing I noticed was the odor. After the odor, I heard the groaning. I remember the occasion quite vividly, although it was ten or eleven years ago. My sister and I had just returned from the park with a neighbor, expecting everything to be normal.

5. A natural disaster destroys the northeastern United States. A woman must travel through a desolate post-apocalyptic New York City to find her son. 6. A podcast host tries to track down a lost love. Write a short story that begins with this first line: "'And that was the last time I saw Peter,' she said tearfully into the mic.

SAMPLE An Introduction to Dramatic Writing. Lesson Aim. Explain the nature and scope of dramatic writing in its broadest context. INTRODUCTION. A genre is the pigeonhole into which your novel or story fits. It might be mainstream, romantic, action and so on. A genre is like a class, form, genus or kind. This course considers the dramatic ...

A narrative essay is one of the most intimidating assignments you can be handed at any level of your education. Where you've previously written argumentative essays that make a point or analytic essays that dissect meaning, a narrative essay asks you to write what is effectively a story.. But unlike a simple work of creative fiction, your narrative essay must have a clear and concrete motif ...

Dramatic Opening Sentences: 25+ Examples and Ideas. June 21, 2018. Admin. by Michael Lydon. It is a truth universally acknowledged, that a single man in possession of a good fortune, must be in want of a wife. -Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice. "Tom!".

Drama Story Ideas Involving Animals. The Stray: A stray dog brings together an estranged family when they decide to adopt it; unknowingly, their lives start changing for the better. Paws for Love: A woman and a man, both lonely and desolate, become friends through their shared affection for a dog in the park.

️ Dramatic Short Story Prompts. Curated with love by Reedsy. Select a genre. Search. We found 47 dramatic stories that match your search 🔦 reset. A long-standing feud erupts during a funeral or wedding. Dramatic. A plane that's been missing for years suddenly lands at a major airport. ...

In the short story, "The Story of an Hour", by Kate Chopin, the author provides two examples of the literary technique of irony to enrich and support the theme, "nothing is as it seems.". Kate Chopin uses both situational and verbal irony in different instances in the story. She uses situational irony to reveal the implausible happiness ...

O'Neil, Patrick. Fiction of Discourse: Reading Narrative Theory. Canada: University of Toronto Press. This essay, "Expressive Writing Dramatic Effect of the Story" is published exclusively on IvyPanda's free essay examples database. You can use it for research and reference purposes to write your own paper.

This essay begins by discussing the situation of blind people in nineteenth-century Europe. It then describes the invention of Braille and the gradual process of its acceptance within blind education. Subsequently, it explores the wide-ranging effects of this invention on blind people's social and cultural lives.

Plantee is up against some pretty formidable competition. At the low end, for just $40 you can pick up a pod-based hydroponic system. If you want to spend a bit more, Click & Grow has your back ...