Why Quality Matters

By Bethany Simunich, Ph.D., QM Vice President of Innovation and Research

This piece was written as a response to a growing sense that fears related to loss of academic freedom and creativity are being fueled by misinformation, including articles and blog posts written by individuals who purport to be deeply and experientially familiar with QM and its tools when they are not. It’s my hope that it addresses misunderstandings about what QM is , how it is used , and the intended purpose of QM Rubrics. More broadly, I hope my experience and perspective can promote constructive dialogue about the need for and appropriate use of standards for online course quality.

I remember with painful acuity the first time I taught an online course. Having previously taught the course for years in a face-to-face (F2F) format, when asked if I’d teach it online, I quickly agreed, eager to explore this new-to-me modality. This was over 15 years ago…before many institutions understood the differences (and nuances) of teaching in the online classroom, and way before I understood anything about designing or teaching online courses. I thought my experience teaching the course and passion for the subject matter would be enough, and that the technology I’d need to “migrate” my course online would be relatively simple and straightforward, even for a Luddite like myself. I distinctly remember thinking, “ How hard can it be? ”

Teaching my first online course was, as you’ve likely guessed, very hard — much more difficult than I had anticipated. It remains to this day the biggest “ I didn’t know what I didn’t know ” experience of my career. Prior to teaching online, I had never deliberately and strategically designed a course, nor had any training on how to do so. Moving online, I quickly learned that I couldn’t create a course in the learning management system the same way I had created it for the on-ground classroom. Like most faculty, I “taught how I was taught,” which for me meant: selecting the textbook, creating lectures to augment that text, developing in-class activities to engage with students and allow them to engage with the material, and creating assignments and exams. I had never truly examined if these components supported one another, as well as my pedagogical goals, and I certainly never had to create a well-organized web-based layout for a course. Designing a great online course, I came to realize, was not only a skill set I didn’t yet have, it was also complex and incredibly time-intensive. In person, I could change things quickly and easily, and I never had to purposefully create a web-based learning path for students, or be transparent about the design of the course. Face-to-face design and teaching were concurrent and dynamically intertwined in a way that asynchronous online design and teaching were not.

Consider this : if our habit is to teach as we were taught, what does that mean for those of us who have never taken an online course? Or have never taken a well-designed online course taught by a great online instructor? I had no models. I had never taken an online course or even seen an example of a good one.

I realized too late in the process that teaching online was not simply digitizing and uploading materials from my F2F class. At this point, I didn’t yet know that uploading a bunch of documents doesn’t equal an online course, and when I realized that I couldn’t even create a “bad” online course easily, I was suddenly struck with an uncomfortable feeling of being unmoored in my teaching and frustrated by the lack of guidance and training. I also felt that I had let my students down before the semester even started. I was woefully unprepared.

I spent the next decade or so learning what I could about designing and teaching online courses, and continue to learn more every day. I left full-time teaching and, after taking additional courses and certificates (I had two masters degrees and a doctorate, but had never had a course on instructional design), accepted an entry-level position as an instructional designer. Since that time, I’ve worked with faculty at several institutions, helping design and revise hundreds of online courses. I’ve trained over a dozen instructional designers and led ID teams. I’ve spent many, many years doing faculty development work for online design and teaching, and have created and delivered dozens of workshops, several online courses, and over a hundred conference presentations on online learning topics. I’ve helped with the development of several fully-online degree programs and worked to bring administrators, faculty, and staff together through the entire process. I’ve conducted research focused on many aspects of online learning and spent time learning the history of the field, while keeping abreast of new research. I’ve surveyed, interviewed, and spoken with over 500 online students about their experiences. And I’ve continued to teach online.

Why am I sharing all of this? Because I believe it is crucial to understand the background and experience that anyone who is talking about quality in online learning brings to the table — what time have they spent striving to increase online quality in a variety of ways, in various institutional contexts, and what roles have they performed in implementing quality assurance at scale?

Humanizing Quality Assurance

Too often, we limit the quality assurance conversations to abstract examples that present quality standards as a phantom menace against creativity, while ignoring the actual people that are harmed by a lack of quality assurance efforts and preparation. Allow me to “humanize” quality for a moment. Achieving online quality means successfully addressing a wide range of real-life challenges such as:

- The fantastic face-to-face teacher who is afraid they’ll lose their connection to their students once they move online;

- The instructor who happily eschewed using technology for many years, but now needs it to support their online teaching;

- The faculty member who doesn’t have a clear idea of how to use web-based navigation and organization to create a learning path;

- The instructional designer tasked with revising dozens or hundreds of online courses, none of which may live up to the institutional reputation or the learning quality that students were promised;

- The administrator who has never taught online or learned online, but now leads the decision-making about online strategy;

- The colleague conducting a peer review of an online course who has never taught online themselves, and is required to use a form designed for F2F teaching evaluation;

- The instructional designers and faculty developers who receive panicked calls from faculty the week (or weekend) before the term begins, desperate for help for online courses that were assigned or not thought about until the last minute, and are not yet designed or built;

- The students who feel as though they’re “teaching themselves”, wondering where the professor is, why they aren’t answering emails, and why the course isn’t visible or ready.

I have experienced every single one of these, either as a faculty member or as online learning staff. It is the last one that especially, and regularly, breaks my heart. All of these situations reflect people in scary, frustrating, or terrible situations. These real-life situations are why we need to talk about the quality of the online learning that we offer our students and get beyond misassumptions that elevating quality can only lead to standardized, “cookie-cutter” courses or a curtailment of academic freedom (neither of which I have seen or been provided evidence of).

The Community Experience

While diving into online learning best practices over the past decade, I discovered Quality Matters (QM) — an international nonprofit dedicated to promoting and improving the quality of online education and student learning. If you are reading this, you likely know QM and are working with them in some capacity. In my former roles at higher ed institutions, I personally used and found QM’s tools and resources to be incredibly valuable. In 2020, I decided to join the team and currently serve as QM’s Director of Research and Innovation. But it wasn’t just about the tools and resources, it was about what QM truly is:

An organization founded by faculty and educational staff that creates and provides tools and processes for quality online learning, and whose work is continuously informed and improved by its members.

It was, in fact, the collegial community that first drew me to QM — it differed so much from the other educational organizations I interacted with. Instead of feeling nameless and overwhelmed at a conference, I felt included and mentored. I found a community of people who were passionate about creating the best online learning opportunities we could for students, including so many online faculty and instructional designers who shared their knowledge and tips. I felt connected and respected, even when I was new to online design and teaching.

Unfortunately, these aspects— and so many other important factors — are often lost in the conversations around QM.

The Quality Matters Rubrics

Those deeply familiar with the QM Rubric know that it inherently provides flexibility, laid out well in the Standard’s Annotations, for how the Specific Review Standards can be met. Over the years, I’ve heard many things that “can’t be done” in a course and still meet quality standards.

Some examples include:

- “I can’t include a video to welcome my students”

- “I can’t utilize ungrading”

- “I can’t make this work for my practicum course”

- “This doesn’t apply to my doctoral students”

- “I teach a [hands-on course, math course, science course, public speaking course], so these things don’t apply/can’t be done”

- “I can’t use a flexible, student-inclusive approach to design my course”

- “I can’t make changes to my course while it’s running/after it’s done”

- “This goes against my academic freedom — I can’t create the course I want to create, use the content I want, incorporate elements of small teaching, etc.”

I would say every single one of these is a false assumption, and points to a limited understanding of the Rubric, rather than a limitation of the Rubric itself. I am not saying that it’s impossible that there could be a situation or pedagogical approach that is limited by the Rubric, but I am saying that I have yet to discover one. One of my colleagues, for example, teaches his online course by embracing open pedagogy and allowing the students to co-author the assessment questions, suggest or create activities, curate and share content, and also select specific topics for exploration in the course. Nothing about that instructional approach would be prohibited or hindered by the QM Rubric so long as the intention and/or goal of that type of assignment is apparent to the student.

I understand that it can be easy and tempting to tear down tools for quality assurance…but my experience shows that these tools can help generate ideas for how we can improve and practice good online education. Too often, ill-informed assumptions and opinions steal valuable time from the conversation of “ How can this be done? ” and “ How can we collectively do this better? ” in order to dive into conversations that often result in defensiveness, posturing, and the marginalization of voices and experiences. I would love to spend more time listening, generating possibilities, and co-creating solutions, and much less time defending online quality assurance from hastily-made assumptions. It’s important to understand, though, what the tools can and cannot help us achieve.

The QM Higher Education Rubric is:

- The first rubric developed by faculty specifically for the evaluation of online courses, and developed with the intent of collegiality, continuous improvement, and flexible implementation;

- The only rubric regularly updated by online faculty, distance learning staff, and online experts to reflect the latest in online learning research and pedagogical practice — over 100 independent educators have participated in updating the Rubric, now in its sixth edition;

- A rubric continuously informed and improved based on usage and feedback from its community;

- A tool maintained and supported by an educational nonprofit staffed by 44 truly dedicated people, most of whom are former teachers, instructional designers, and educational staff.

Quality Matters has created a quality assurance tool — five tools , actually — that are usable and adaptable across all disciplines, all institution types, all online modalities, and all class sizes. How is that possible? Because at their core, the QM Rubrics are — more than anything else — flexible .

QM Rubrics:

- Do NOT require or prescribe a particular pedagogical approach or philosophy, specific teaching strategies or methods, and do not dictate types of instructional materials or assessments;

- Provide Annotations that offer a myriad of ways, though not exhaustive, to meet each Standard;

- Provide the opportunity to embed yourself in the student perspective.

In short, you simply cannot create and use inflexible, un-adaptable tools when you are serving over 1,500 unique educational institutions and over 100,000 educators around the globe. If the QM Rubrics were truly rigid, inflexible, or an impingement on creativity and freedom, then we wouldn’t see thousands of QM-Certified courses that span countless disciplines, course types, institutional cultures, faculty, and pedagogical strategies. We wouldn’t see a 99% satisfaction rate by faculty who engage in the QM-Certified review process, or data that shows 98% of faculty who engage with our professional development find the information so valuable, that they take it back to their F2F classroom as well.

It’s important to note, though, that while QM Rubrics reflect well-researched instructional design principles, they’re not a course design checklist, and to see it as such would likely create the assumption that online course design is prescriptive. For faculty who were looking for a design guide, however, and who especially need design assistance during the pandemic, QM developed the publicly available Bridge to Quality Design Guide .

It’s important to view the Rubric through the lens that you are applying it, whether via its original, intended use as a review tool for online quality assurance, or in an adaptation of that use — as a tool for information and ideas as you design your online course. Let me give an example:

Standard 5.3 reads: The instructor’s plan for interacting with learners during the course is clearly stated . If you’re reviewing a course, you’d then look to the Annotation, which provides more information, including having a clear plan for interacting with students in primary ways, such as responding to questions and providing feedback. It provides several, non-exhaustive examples of information that instructors might give to their online students, as well as several examples of where this information is commonly found. It doesn’t prescribe that you adhere to any particular type of grading approach or that you provide a specific type of feedback. It also includes specific information if one is reviewing a Competency-Based Course.

Let’s say that a given course includes information in the syllabus that lets students know that if they email or post a question, they’ll receive a reply within 24 hours during the week and 48 hours on the weekend. Additionally, the instructor lets students know that they can expect to receive feedback on course activities within a week after they submit their work. Students are also informed that their instructor makes the effort to provide feedback within one week so that they can use that feedback to improve their work on the next activity or assessment. The QM-Certified Peer Reviewer in this case isn’t asked if they agree with the policy — they might, for example, feel that a one-week turnaround time is an unreasonable promise, or that they themselves have a 24-hour response time for questions, even on weekends. The Reviewer can provide feedback and suggestions, but they are only evaluating the Standard in terms of whether they, from the student perspective, would understand some important ways their instructor is going to interact with them and respond to their needs in their asynchronous course. This is a great example of how the QM Rubric is not prescriptive… unless one disagrees with the idea that we should let students know when we’ll answer their questions or provide feedback.

However, if you’re adapting the Rubric as a guide for design , you might be inspired to ask colleagues how they think through their policy, and even what approaches seem to work better for the cohort of students that typically take your class. The Annotation provides a bit of the “why” as well, which can also prompt some good reflection as you design. One note, for example, says: “Frequent feedback from the instructor increases learners' sense of engagement in a course. Learners are better able to manage their learning activities when they know upfront when to expect feedback from the instructor.” This cues you into how this Standard is grounded in research and best practices for student engagement, as well as methods to elevate teaching presence. There are a variety of ways to meet this Standard in your online course, and there is no requirement that all policies look the same or be standardized.

Beyond Rubrics

While QM is often synonymous with its Rubrics, QM is actually a comprehensive, multi-faceted quality assurance framework, whose use and implementation are customizable to institutional needs and goals. In addition to the Rubric, QM offers multiple course review options as well as professional development opportunities and a number of publicly available free resources .

Just like there are a variety of ways to use the Rubrics, there’s no “one, right way” to evaluate review quality. QM does offer a pathway for certified, third-party reviews by faculty specifically experienced with online teaching and evaluation — an option rarely presented for face-to-face courses. But those reviews are only one of many ways to meet institutional and student goals for quality. There are also a variety of other review options and pathways available, including:

- Internal reviews that combine institutional standards with QM Standards

- Internal reviews that combine institutional standards with select QM Standards

- “Lite” QM Reviews that focus only on select QM Standards, as determined by the institution or faculty member

- Internal reviews that combine QM Standards with other rubric standards

- Self-reviews done by the faculty teaching the course

All of these options are available, and QM even has a tool to enable this flexibility called My Custom Reviews (MyCR). This tool, like so many of QM’s other resources, is designed to allow institutions to choose what standards they want to use and what processes they want to create for reviewing courses.

If you are engaging with official reviews, here are some important facts you need to know:

- Official Reviews are a collegial, collaborative, faculty-driven process;

- Review teams are made up of three individuals, all of whom have taught a for-credit online or blended course in the last 18 months;

- All Reviewers go through a rigorous professional development process;

- The review process is designed to be diagnostic and collegial, not evaluative and judgmental;

- The subjectivity of human judgment is embedded within the review process. Reviewers are encouraged to discuss and are not led to a forced agreement or unanimous decision;

- Instructors receive three independent pieces of feedback for each standard, which they could choose to apply or not, in a way that works for them and their students.

The Review process is, in fact, more collegial and collaborative than any classroom-based review that I’ve been a part of or witnessed. I often felt it shortchanged a F2F class to have a peer attend a single class session and make judgments from a templated checklist. The QM Peer Review process, on the other hand, begins with the instructor discussing the course, describing the design, their learning goals, their students, and more. As the review is conducted, Reviewers continue the dialogue with the instructor, and ask questions or make suggestions for quick fixes. The Review team itself represents a diversity of experiences and voices, comprised of three online teaching faculty — a great improvement, in my opinion, from the too-often singular review voice of an institutionally-based evaluation of a F2F course.

Quality Matters Implementation

The QM framework, consisting of the Rubric, supporting professional development, and options for internal and certified reviews, are resources, processes, and tools that are implemented by the institution. Quality assurance implementation, however, is often not given the consideration for the change-management initiative that it is, and institutions may experience missteps or disruptions if it’s not created as an inclusive process that reflects the institutional culture and goals. QM doesn’t prescribe how an institution implements the QM tools and resources for quality assurance. An individual faculty member has many choices about how they can use the QM Rubric, engage with professional development, or conduct course reviews. However, the most successful implementations occur when considered in conjunction with the institutional culture and context — including stated goals — and also when the implementation is inclusive, collaborative, and collegial in nature.

Additionally, we’re supporting this work with research to further explore best practices and key drivers in implementing online quality assurance within higher ed institutions. Current findings include choosing the right person/people to lead this effort, making it inclusive from the start, and embracing a bottom-up approach. If you believe that your institution is not meeting faculty, staff, student, and other stakeholder needs with regard to QA implementation, I encourage you to have crucial conversations about implementation efforts, to connect with campus offices and partners that support QA in online learning, and to connect with the resources and training that organizations like QM provide to help in these efforts. Oftentimes, implementation is intrinsically linked with accreditation efforts, and that is an additional place to begin, or continue, the dialogue. QM also provides professional development opportunities, including two free workshops seats for those coordinating implementation efforts, and additional resources to help faculty and institutions decide how implementation would work best on their campus.

The Student Experience

In all of the talk about rubrics, reviews, policies, and implementation, however, it’s important we don’t forget about those who are disadvantaged by lower quality online learning experiences. The human face of quality assurance is equally valid to academically-embedded conversations that never extend to online students. Students are the ones who are disadvantaged by lower-quality online learning experiences and need to be at the heart of the conversation. Consider the following real-life examples:

- The online student who struggled with a midterm assignment but did not reach out to his professor for help. Why? Because he felt like he didn’t really know his professor — he was worried that the professor wasn’t nice, and wouldn’t help. In truth, his professor was kind, engaging, and student-focused… but had never thought about creating an instructor introduction video. The student had never even seen his face or heard his voice.

- The online student who emailed me out of desperation, fearing she was failing her class and couldn’t afford to retake it. She accompanied her emails with screenshots of the course, convinced she was “too dumb” to figure things out. Emails to her instructor had gone unanswered. Looking at the screenshots, I could see her struggles were largely a result of how the course was organized. All the files had been uploaded into a single folder with no directions or guidance. I also discovered the instructor had not been in the course for several weeks.

- The online student who I found in tears in the campus library, devastated about their performance on a midterm exam. They thought they had prepared well by watching the instructor videos (on campus because their home internet did not have the bandwidth to handle the hour+ length of each video). They had read all the materials, highlighted key passages, and made review cards and a study guide. When I asked what they felt had “gone wrong,” they replied: “I didn’t know I wasn’t understanding the material. We had some quizzes, but they hadn’t been graded, so I didn’t know how I was doing. It wasn’t until a few questions into the midterm that I realized I had some big misunderstandings, and I wasn’t thinking about things like I should, but by then it was too late.”

This is the other side of online course standards and policies. It might seem like a great, freeing idea to not be clear with students about expectations, to not approach your design by also thinking about how you’ll connect with and interact with students, to not learn about good organization and navigation, to not tell your students how they can contact you and when they’ll receive a response, to not give students multiple chances and ways to check their understanding and gauge their learning process… but the reality is that not considering best practices such as this frequently disadvantages students .

I ended up meeting with all three of these faculty, and trust me when I say that they absolutely wanted to do the very best for their online students. They didn’t know, however, that it’s important to introduce themselves as an instructor (Standard 1.8), that they needed to consider before the course began how they would interact with students, including responding to questions and providing feedback (Standard 5.3), that navigation and organization are absolutely crucial in online design (Standard 8.1), that posting long videos causes technology and accessibility issues for students, and is often too much information to absorb or review at one time (Standard 8.4), or that online students need multiple opportunities to check their understanding and progress (Standard 3.5), and with prompt feedback.

These were caring, experienced instructors who just didn’t know what they didn’t know .

The Whole Quality Picture

Equally important as what we “don’t know,” is defining what it is we are talking about when we discuss quality — because it’s vital to understand that “quality” is not just one thing . It lies not only in the design of an online course but also in:

- The quality of the content the faculty chooses to create or curate for the course;

- The effectiveness of their teaching (as well as how well they’re supported in that teaching);

- The institutional infrastructure and readiness for quality online learning;

- The preparedness and support of our online students;

- The technology used, including how faculty and learners are supported in using the technology that supports good online learning.

Quality online learning is more than a rubric, or any single tool, and it is a privileged perspective to posit that we should not define what quality means for students, nor create tools and processes to support faculty in improvements that lead to greater quality. Objections fail to address equity, access, student preparedness, and the complex, real-life issues faced when trying to ensure that all students receive a quality learning experience, regardless of whether that course is online or face-to-face. We can’t ignore the very real institutional barriers embedded in the change management it requires to create and implement quality initiatives at scale, nor the reality that many instructional designers know: across the vast landscape of higher education there are, and long have-been, online courses that fail to meet basic student needs, whether for support or learning.

Be Part of the Conversation

I want to make clear that I am not claiming, nor do I believe, that the QM Rubric is perfect and should never be critiqued or improved. If I, or QM, felt that way, we wouldn’t bring together community experts, combined with expansive survey feedback from all our community members, to regularly revise the Rubric. We already intend, for example, to include more information about inclusive and culturally responsive design in the next Rubric revision.

You, as a member of our community, matter! And we want to invite you to share your thoughts. Please feel free to complete this short survey , which can be filled out anonymously. We continuously provide many avenues for the community to share their comments, ideas, and questions, and use that feedback to inform and improve the resources and services we provide. We also have options for individual consultations, and can join the conversation at your campus via a web meeting as well.

Thank you for all you do to ensure high-quality online learning for your students, and thank you, in advance, for sharing your experiences, ideas, and questions with us. I look forward to our continued collaboration and conversation.

Dr. Bethany Simunich is QM’s Director of Research and Innovation. She has worked in higher education for over 20 years and has over 15 years of experience in eLearning research, instructional design and online pedagogy. As QM's Director of Research and Innovation, she helps provide research-based tools, ideas and solutions to enable individuals and institutions to assess and achieve their quality assurance goals. Her research interests include presence in the online classroom, online student and instructor self-efficacy and satisfaction, and outcomes achievement in online courses. Connect with Dr. Simunich on Twitter or LinkedIn .

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- How to improve...

How to improve healthcare improvement—an essay by Mary Dixon-Woods

Read the full collection.

- Related content

- Peer review

- Mary Dixon-Woods , director

- THIS Institute, Cambridge, UK

- director{at}thisinstitute.cam.ac.uk

As improvement practice and research begin to come of age, Mary Dixon-Woods considers the key areas that need attention if we are to reap their benefits

In the NHS, as in health systems worldwide, patients are exposed to risks of avoidable harm 1 and unwarranted variations in quality. 2 3 4 But too often, problems in the quality and safety of healthcare are merely described, even “admired,” 5 rather than fixed; the effort invested in collecting information (which is essential) is not matched by effort in making improvement. The National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death, for example, has raised many of the same concerns in report after report. 6 Catastrophic degradations of organisations and units have recurred throughout the history of the NHS, with depressingly similar features each time. 7 8 9

More resources are clearly necessary to tackle many of these problems. There is no dispute about the preconditions for high quality, safe care: funding, staff, training, buildings, equipment, and other infrastructure. But quality health services depend not just on structures but on processes. 10 Optimising the use of available resources requires continuous improvement of healthcare processes and systems. 5

The NHS has seen many attempts to stimulate organisations to improve using incentive schemes, ranging from pay for performance (the Quality and Outcomes Framework in primary care, for example) to public reporting (such as annual quality accounts). They have had mixed results, and many have had unintended consequences. 11 12 Wanting to improve is not the same as knowing how to do it.

In response, attention has increasingly turned to a set of approaches known as quality improvement (QI). Though a definition of exactly what counts as a QI approach has escaped consensus, QI is often identified with a set of techniques adapted from industrial settings. They include the US Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s Model for Improvement, which, among other things, combines measurement with tests of small change (plan-do-study-act cycles). 8 Other popular approaches include Lean and Six Sigma. QI can also involve specific interventions intended to improve processes and systems, ranging from checklists and “care bundles” of interventions (a set of evidence based practices intended to be done consistently) through to medicines reconciliation and clinical pathways.

QI has been advocated in healthcare for over 30 years 13 ; policies emphasise the need for QI and QI practice is mandated for many healthcare professionals (including junior doctors). Yet the question, “Does quality improvement actually improve quality?” remains surprisingly difficult to answer. 14 The evidence for the benefits of QI is mixed 14 and generally of poor quality. It is important to resolve this unsatisfactory situation. That will require doing more to bring together the practice and the study of improvement, using research to improve improvement, and thinking beyond effectiveness when considering the study and practice of improvement.

Uniting practice and study

The practice and study of improvement need closer integration. Though QI programmes and interventions may be just as consequential for patient wellbeing as drugs, devices, and other biomedical interventions, research about improvement has often been seen as unnecessary or discretionary, 15 16 particularly by some of its more ardent advocates. This is partly because the challenges faced are urgent, and the solutions seem obvious, so just getting on with it seems the right thing to do.

But, as in many other areas of human activity, QI is pervaded by optimism bias. It is particularly affected by the “lovely baby” syndrome, which happens when formal evaluation is eschewed because something looks so good that it is assumed it must work. Five systematic reviews (published 2010-16) reporting on evaluations of Lean and Six Sigma did not identify a single randomised controlled trial. 17 18 19 20 21 A systematic review of redesigning care processes identified no randomised trials. 22 A systematic review of the application of plan-do-study-act in healthcare identified no randomised trials. 23 A systematic review of several QI methods in surgery identified just one randomised trial. 56

The sobering reality is that some well intentioned, initially plausible improvement efforts fail when subjected to more rigorous evaluation. 24 For instance, a controlled study of a large, well resourced programme that supported a group of NHS hospitals to implement the IHI’s Model for Improvement found no differences in the rate of improvement between participating and control organisations. 25 26 Specific interventions may, similarly, not survive the rigours of systematic testing. An example is a programme to reduce hospital admissions from nursing homes that showed promise in a small study in the US, 27 but a later randomised implementation trial found no effect on admissions or emergency department attendances. 28

Some interventions are probably just not worth the effort and opportunity cost: having nurses wear “do not disturb” tabards during drug rounds, is one example. 29 And some QI efforts, perversely, may cause harm—as happened when a multicomponent intervention was found to be associated with an increase rather than a decrease in surgical site infections. 30

Producing sound evidence for the effectiveness of improvement interventions and programmes is likely to require a multipronged approach. More large scale trials and other rigorous studies, with embedded qualitative inquiry, should be a priority for research funders.

Not every study of improvement needs to be a randomised trial. One valuable but underused strategy involves wrapping evaluation around initiatives that are happening anyway, especially when it is possible to take advantage of natural experiments or design roll-outs. 31 Evaluation of the reorganisation of stroke care in London and Manchester 32 and the study of the Matching Michigan programme to reduce central line infections are good examples. 33 34

It would be impossible to externally evaluate every QI project. Critically important therefore will be increasing the rigour with which QI efforts evaluate themselves, as shown by a recent study of an attempt to improve care of frail older people using a “hospital at home” approach in southwest England. 35 This ingeniously designed study found no effect on outcomes and also showed that context matters.

Despite the potential value of high quality evaluation, QI reports are often weak, 18 with, for example, interventions so poorly reported that reproducibility is frustrated. 36 Recent reporting guidelines may help, 37 but some problems are not straightforward to resolve. In particular, current structures for governance and publishing research are not always well suited to QI, including situations where researchers study programmes they have not themselves initiated. Systematic learning from QI needs to improve, which may require fresh thinking about how best to align the goals of practice and study, and to reconcile the needs of different stakeholders. 38

Using research to improve improvement

Research can help to support the practice of improvement in many ways other than evaluation of its effectiveness. One important role lies in creating assets that can be used to improve practice, such as ways to visualise data, analytical methods, and validated measures that assess the aspects of care that most matter to patients and staff. This kind of work could, for example, help to reduce the current vast number of quality measures—there are more than 1200 indicators of structure and process in perioperative care alone. 39

The study of improvement can also identify how improvement practice can get better. For instance, it has become clear that fidelity to the basic principles of improvement methods is a major problem: plan-do-study-act cycles are crucial to many improvement approaches, yet only 20% of the projects that report using the technique have done so properly. 23 Research has also identified problems in measurement—teams trying to do improvement may struggle with definitions, data collection, and interpretation 40 —indicating that this too requires more investment.

Improvement research is particularly important to help cumulate, synthesise, and scale learning so that practice can move forward without reinventing solutions that already exist or reintroducing things that do not work. Such theorising can be highly practical, 41 helping to clarify the mechanisms through which interventions are likely to work, supporting the optimisation of those interventions, and identifying their most appropriate targets. 42

Research can systematise learning from “positive deviance,” approaches that examine individuals, teams, or organisations that show exceptionally good performance. 43 Positive deviance can be used to identify successful designs for clinical processes that other organisations can apply. 44

Crucially, positive deviance can also help to characterise the features of high performing contexts and ensure that the right lessons are learnt. For example, a distinguishing feature of many high performing organisations, including many currently rated as outstanding by the Care Quality Commission, is that they use structured methods of continuous quality improvement. But studies of high performing settings, such as the Southmead maternity unit in Bristol, indicate that although continuous improvement is key to their success, a specific branded improvement method is not necessary. 45 This and other work shows that not all improvement needs to involve a well defined QI intervention, and not everything requires a discrete project with formal plan-do-study-act cycles.

More broadly, research has shown that QI is just one contributor to improving quality and safety. Organisations in many industries display similar variations to healthcare organisations, including large and persistent differences in performance and productivity between seemingly similar enterprises. 46 Important work, some of it experimental, is beginning to show that it is the quality of their management practices that distinguishes them. 47 These practices include continuous quality improvement as well as skills training, human resources, and operational management, for example. QI without the right contextual support is likely to have limited impact.

Beyond effectiveness

Important as they are, evaluations of the approaches and interventions in individual improvement programmes cannot answer every pertinent question about improvement. 48 Other key questions concern the values and assumptions intrinsic to QI.

Consider the “product dominant” logic in many healthcare improvement efforts, which assumes that one party makes a product and conveys it to a consumer. 49 Paul Batalden, one of the early pioneers of QI in healthcare, proposes that we need instead a “service dominant” logic, which assumes that health is co-produced with patients. 49

More broadly, we must interrogate how problems of quality and safety are identified, defined, and selected for attention by whom, through which power structures, and with what consequences. Why, for instance, is so much attention given to individual professional behaviour when systems are likely to be a more productive focus? 50 Why have quality and safety in mental illness and learning disability received less attention in practice, policy, and research 51 despite high morbidity and mortality and evidence of both serious harm and failures of organisational learning? The concern extends to why the topic of social inequities in healthcare improvement has remained so muted 52 and to the choice of subjects for study. Why is it, for example, that interventions like education and training, which have important roles in quality and safety and are undertaken at vast scale, are often treated as undeserving of evaluation or research?

How QI is organised institutionally also demands attention. It is often conducted as a highly local, almost artisan activity, with each organisation painstakingly working out its own solution for each problem. Much improvement work is conducted by professionals in training, often in the form of small, time limited projects conducted for accreditation. But working in this isolated way means a lack of critical mass to support the right kinds of expertise, such as the technical skill in human factors or ergonomics necessary to engineer a process or devise a safety solution. Having hundreds of organisations all trying to do their own thing also means much waste, and the absence of harmonisation across basic processes introduces inefficiencies and risks. 14

A better approach to the interorganisational nature of health service provision requires solving the “problem of many hands.” 53 We need ways to agree which kinds of sector-wide challenges need standardisation and interoperability; which solutions can be left to local customisation at implementation; and which should be developed entirely locally. 14 Better development of solutions and interventions is likely to require more use of prototyping, modelling and simulation, and testing in different scenarios and under different conditions, 14 ideally through coordinated, large scale efforts that incorporate high quality evaluation.

Finally, an approach that goes beyond effectiveness can also help in recognising the essential role of the professions in healthcare improvement. The past half century has seen a dramatic redefining of the role and status of the healthcare professions in health systems 54 : unprecedented external accountability, oversight, and surveillance are now the norm. But policy makers would do well to recognise how much more can be achieved through professional coalitions of the willing than through too many imposed, compliance focused diktats. Research is now showing how the professions can be hugely important institutional forces for good. 54 55 In particular, the professions have a unique and invaluable role in working as advocates for improvement, creating alliances with patients, providing training and education, contributing expertise and wisdom, coordinating improvement efforts, and giving political voice for problems that need to be solved at system level (such as, for example, equipment design).

Improvement efforts are critical to securing the future of the NHS. But they need an evidence base. Without sound evaluation, patients may be deprived of benefit, resources and energy may be wasted on ineffective QI interventions or on interventions that distribute risks unfairly, and organisations are left unable to make good decisions about trade-offs given their many competing priorities. The study of improvement has an important role in developing an evidence-base and in exploring questions beyond effectiveness alone, and in particular showing the need to establish improvement as a collective endeavour that can benefit from professional leadership.

Mary Dixon-Woods is the Health Foundation professor of healthcare improvement studies and director of The Healthcare Improvement Studies (THIS) Institute at the University of Cambridge, funded by the Health Foundation. Co-editor-in-chief of BMJ Quality and Safety , she is an honorary fellow of the Royal College of General Practitioners and the Royal College of Physicians. This article is based largely on the Harveian oration she gave at the RCP on 18 October 2018, in the year of the college’s 500th anniversary. The oration is available here: http://www.clinmed.rcpjournal.org/content/19/1/47 and the video version here: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/events/harveian-oration-and-dinner-2018

This article is one of a series commissioned by The BMJ based on ideas generated by a joint editorial group with members from the Health Foundation and The BMJ , including a patient/carer. The BMJ retained full editorial control over external peer review, editing, and publication. Open access fees and The BMJ ’s quality improvement editor post are funded by the Health Foundation.

Competing interests: I have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and a statement is available here: https://www.bmj.com/about-bmj/advisory-panels/editorial-advisory-board/mary-dixonwoods

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; not externally peer reviewed.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

- Neuburger J ,

- Hutchings A ,

- Stewart K ,

- Buckingham R

- Castelli A ,

- Verzulli R ,

- Allwood D ,

- Sunstein CR

- Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership

- Shortell SM

- Martin GP ,

- Dixon-Woods M

- Donabedian A

- Himmelstein DU ,

- Woolhandler S

- Woolhandler S ,

- Himmelstein DU

- Dixon-Woods M ,

- Ioannidis JPA ,

- Marshall M ,

- Pronovost P ,

- Glasgow JM ,

- Scott-Caziewell JR ,

- Nicolay CR ,

- Deblois S ,

- Moraros J ,

- Lemstra M ,

- Amaratunga T ,

- Dobranowski J

- van Leijen-Zeelenberg JE ,

- Elissen AMJ ,

- Taylor MJ ,

- McNicholas C ,

- Nicolay C ,

- Morgan DJ ,

- Diekema DJ ,

- Sepkowitz K ,

- Perencevich EN

- Benning A ,

- Ouslander JG ,

- Huckfeldt P ,

- Westbrook JI ,

- Hooper TD ,

- Middleton S ,

- Anthony T ,

- Murray BW ,

- Sum-Ping JT ,

- Portela MC ,

- Pronovost PJ ,

- Woodcock T ,

- Ramsay AIG ,

- Hoffman A ,

- Richardson A ,

- Hibbert P ,

- Matching Michigan Collaboration & Writing Committee

- Tarrant C ,

- Pearson M ,

- Hemsley A ,

- Blackwell R ,

- Custerson L

- Goodman D ,

- Watson SI ,

- Taylor CA ,

- Chazapis M ,

- Gilhooly D ,

- Liberati EG ,

- Davidoff F ,

- Leviton L ,

- Johnston M ,

- Abraham C ,

- “Psychological Theory” Group

- Clay-Williams R ,

- Braithwaite J

- Bradley EH ,

- Willars J ,

- Mahajan A ,

- Aveling EL ,

- Thibaut BI ,

- Ramtale SC ,

- Boozary AS ,

- Shojania KG

- Pronovost PJ

- Armstrong N ,

- Herbert G ,

- Purkayastha S ,

- Greenhalgh A ,

Importance and seven principles of quality management

Checked : Mark A. , Abigail C.

Latest Update 20 Jan, 2024

Table of content

- Quality management: what exactly?

The importance of quality management for the company

The basic principles of quality management, the seven principles of quality management, 1 - customer orientation, 2 - management responsibility (leadership), 3 - staff involvement, 4 - process approach, 5 – improvement, 6 - evidence-based decision making, 7 - management of relations with interested parties.

Quality management is the process by which a company seeks to achieve its quality objectives. But how important is it really? Our article gives you an explanation.

Quality management: what exactly?

It is the set of strategies implemented by a company in order to establish a quality approach within it. This approach aims, for its part, to improve the quality of organization and production. To do this, it seeks to optimize the quality of management, products, and services offered to customers or the employee environment.

The ISO 9001 quality management approach calls on strategies, equipment, and actors who contribute to the implementation of concrete improvement actions. Therefore, these actions and the resources involved constitute the quality management system (QMS), governed by the ISO 9001 standard.

The quality management system represents a pillar of growth for the company. The reason is simple: its effectiveness is largely based on this system. It is indeed this process that allows the company to have an efficient organization in which employees participate in achieving development objectives. This quality approach is also essential to set up a service that meets customer expectations and achieves a high level of satisfaction.

In a word, quality management is the pivot of the company's competitiveness. Without this system, it will be difficult for him to make a profit from his activity and optimize his profits. Therefore, the development of an effective quality management system is crucial for any company that wishes to evolve in its environment.

An effective quality approach revolves around the seven principles set out in the ISO 9001 standard. Indeed, these principles are considered to be the main factors for the success of a QMS.

The ISO 9001: 2015 standards on quality management systems are based on general principles. There are 7 quality management principles are used, compared to 8 for the 2008 edition. These principles are developed in 2.3 of ISO 9000: 2015 ("Quality management systems - Essential principles and vocabulary"); part of this information is included in annex B of ISO 9001: 2015. This article uses these standards to present the "philosophy" of management principles. Each principle is illustrated with a quote for ease of understanding.

The titles are those of ISO / DIS 9000: 2014; they should not change in the final version. Some are obvious and natural, and all show common sense.

- Client orientation

- Management responsibility

- Staff involvement

- Process approach

- Improvement

- Evidence-based decision making

- Management of relations with interested parties

To convince you of the merits of this approach, let's imagine these seven principles, but taken in reverse:

- Customer operations

- Impassibility of management

- Staff impairment

- Rambling approach

- Deterioration

- Heads-up decision

- Disengagement from relationships with interested parties

There is only one boss: the customer. And he can fire all the staff, from the manager to the employee, simply by spending his money elsewhere. The challenge of this principle is to satisfy the customer to build customer loyalty. This is all the more important since today, with social networks and the internet in general; the customer can express his dissatisfaction/delight and be heard by everyone, immediately. What demolish the image of an organization or, on the contrary, forge an excellent reputation.

To strengthen its customer orientation, the organization must work on its customers' expectations: identify them (and even anticipate them) and make every effort to ensure that the products/services offered to meet them. Quality management must take an interest in customer needs in order to understand them better and set up services that adapt to their expectations.

The performance of a company depends on managers' ability to mobilize collective intelligence for the achievement of the objectives set.

In addition to not investing all of the company's profits in the renovation of its bachelor apartment, management is expected to:

- Define the direction of the body

- Ensures the availability of resources to achieve the objectives

- Involve staff

Thus, the body knows where it should go, has the means, and the desire.

Employee involvement:

Employee involvement and motivation are the pillars of the company's performance and growth.

The title of this principle is reductive:

In addition to being involved (due to its management's great work), the staff must be competent and feel valued. It is really a question of considering the individual under the blue of work. In this spirit, recognition must be expressed by communicating on the added value of the work of the staff and the initiatives taken. Personal skills need to be developed, which will improve the skills of the organization as a whole.

Managing resources and activities as a global process make it possible to obtain a more precise vision of its performance. Having a process approach means considering the activity of the organism as a set of correlated sub-activities. In this model, each process takes into account input data and produces output data. This data can go from one process to another. This approach makes it easier to tackle the different activities, their management, their needs, their objectives. It is, of course, natural that a company organizes itself in services, each managing processes.

We Will Write an Essay for You Quickly

This involves maintaining development actions continuously in order to improve the performance of the company constantly. The organization must constantly seek to improve (the famous continuous improvement), at least to maintain its performance levels, ideally to progress. Improvement applies to the principles already set out: the improvement of customer satisfaction and improvement of process performance. In ISO9001: 2015, reducing risks, seizing opportunities, or even correcting non-conformities are all sources of improvement.

The objective is to pay particular attention to the elements and factual results.

The idea is to reduce the inevitable uncertainty when making decisions by relying on objective data, where we look at the causes to understand the effects.

Supplier Relations is finding a way to maintain a strong relationship with suppliers.

The stakeholders include all factors that influence or are influenced by the organization's activities. They include, in particular: suppliers, bankers, regulation, and even the ISO9001 standard. It is by communicating with interested parties and taking their requirements into account that the organization will be able to improve its performance.

Have you any questions? Let us know in the comment box. And for business essay, don’t hesitate to contact us.

Looking for a Skilled Essay Writer?

- Ohio State University Bachelor's degree

No reviews yet, be the first to write your comment

Write your review

Thanks for review.

It will be published after moderation

Latest News

What happens in the brain when learning?

10 min read

20 Jan, 2024

How Relativism Promotes Pluralism and Tolerance

Everything you need to know about short-term memory

Why Is Quality Important for a Business?

- Small Business

- Business Communications & Etiquette

- Importance of Business Communication

- ')" data-event="social share" data-info="Pinterest" aria-label="Share on Pinterest">

- ')" data-event="social share" data-info="Reddit" aria-label="Share on Reddit">

- ')" data-event="social share" data-info="Flipboard" aria-label="Share on Flipboard">

What Are the Benefits of a Company With a Well-Executed Branding Strategy?

Penetration pricing advantages over skim pricing, what core competencies give an organization competitive advantage.

- The Advantages of Supply Chain Management Systems

- Marketing Environment & Competitor Analysis

With so many options available to customers, you may be wondering whether or not quality still matters. The answer is a resounding “yes,” and quality isn’t just about offering a product or service that exceeds the standard, but it’s also about the reputation you gain for consistently delivering a customer experience that is “above and beyond.” Managing quality is crucial for small businesses.

Quality products help to maintain customer satisfaction and loyalty and reduce the risk and cost of replacing faulty goods. Companies can build a reputation for quality by gaining accreditation with a recognized quality standard.

Meet Customer Expectations

Regardless of what industry you’re involved in, your customers aren’t going to choose you solely based on price, but often on quality. In fact, studies have shown that customers will pay more for a product or service that they think is made well or exceeds the standard. Your customers expect you to deliver quality products.

Quality is Critical to Satisfied Customers

If you fail to meet customers' expectation, they will quickly look for alternatives. Quality is critical to satisfying your customers and retaining their loyalty so they continue to buy from you in the future. Quality products make an important contribution to long-term revenue and profitability. They also enable you to charge and maintain higher prices.

Quality is a key differentiator in a crowded market. It’s the reason that Apple can price its iPhone higher than any other mobile phone in the industry – because the company has established a long history of delivering superior products.

Establish Your Reputation

Quality reflects on your company’s reputation. The growing importance of social media means that customers and prospects can easily share both favorable opinions and criticism of your product quality on forums, product review sites and social networking sites, such as Facebook and Twitter. A strong reputation for quality can be an important differentiator in markets that are very competitive. Poor quality or product failure that results in a product recall campaign can lead to negative publicity and damage your reputation.

If your business consistently delivers what it promises, your customers are much more likely to sing your praises on social media platforms. This not only helps drive your brand awareness, but it also creates the much-desired FOMO effect, which stands for “Fear of Missing Out.” Social-media users that see your company’s strong reputation will want to become part of the product or service you’re offering, which can boost your sales.

Meet or Exceed Industry Standards

Adherence to a recognized quality standard may be essential for dealing with certain customers or complying with legislation. Public-sector companies, for example, may insist that their suppliers achieve accreditation with quality standards. If you sell products in regulated markets, such as health care, food or electrical goods, you must be able to comply with health and safety standards designed to protect consumers.

Accredited quality control systems play a crucial role in complying with those standards. Accreditation can also help you win new customers or enter new markets by giving prospects independent confirmation of your company’s ability to supply quality products.

Manage Costs Effectively

Poor quality increases costs. If you do not have an effective quality-control system in place, you may incur the cost of analyzing nonconforming goods or services to determine the root causes and retesting products after reworking them.

In some cases, you may have to scrap defective products and pay additional production costs to replace them. If defective products reach customers, you will have to pay for returns and replacements and, in serious cases, you could incur legal costs for failure to comply with customer or industry standards.

- Reputation Management: Why a Great Company Reputation is Important

- Entrepreneur: 7 Ways Quality Boosts Business That Quantity Can’t Match

- CMO: Consumers Say They Will Pay More For a Better Experience

Sampson Quain is an experienced content writer with a wide range of expertise in small business, digital marketing, SEO marketing, SEM marketing, and social media outreach. He has written primarily for the EHow brand of Demand Studios as well as business strategy sites such as Digital Authority.

Related Articles

How to upload crisp facebook profile pictures for companies, retail industry and vendor relations, describe the factors used by marketers to position products, importance of containing quality costs, quality control of exports, what does elasticity mean in a company, what steps do companies take to maximize profit or minimize loss, quality management system goals & objectives, the importance of continuous improvement in marketing, most popular.

- 1 How to Upload Crisp Facebook Profile Pictures for Companies

- 2 Retail Industry and Vendor Relations

- 3 Describe the Factors Used by Marketers to Position Products

- 4 Importance of Containing Quality Costs

Essay on Quality Control of Products: Top 13 Essays

After reading this essay you will learn about:- 1. Meaning and Definitions of Quality Control 2. Quality Control Organisation 3. Advantages of Quality Control 4. Quality Control for Export 5. Indian Standard Institution 6. Quality Assurance 7. Causes of Quality Failures 8. Economics of Quality 9. Product Quality Analysis 10. Quality Planning 11. Quality Improvement 12. Quality Management System 13. Role of Top Management.

- Essay on the Role of Top Management towards Quality

Essay # 1. Meaning and Definitions of Quality Control :

Quality control in its simplest term, is the control of quality during manufacturing. Both quality control and inspection are used to assure quality. Inspection is a determining function which determines raw materials, supplies, parts or finished products etc. as acceptable or unacceptable.

As control becomes effective, the need for inspection decreases. Quality control determines the cause for variations in the characteristics of products and gives solutions by which these variations can be controlled. It is economic in its purpose, objective in its procedure, dynamic in its operation and helpful in its treatment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Since variations in raw materials have large effects on the quality of in-process materials, quality control includes statistical sampling and testing before acceptance. It also includes the examination of quality characteristics in finished products so as to assure satisfactory outgoing quality.

Cooperation between the quality control group and other departments such as production, planning and inspection is of vital importance. With proper managerial support and co-operation the quality control programme will be more successful.

Definitions :

In current quality control theory and practice, the meaning of “Quality” is closely allied to cost and customer needs. “Quality” may simply be defined as fitness for purpose at lowest cost.

“Quality” of any product is regarded as the degree to which it fulfills the requirements of the customer. “Quality” means degree of perfection. Quality is not absolute but it can only be judged or realized by comparing with standards. It can be determined by some characteristics namely, design, size, material, chemical composition, mechanical functioning, workmanship, finishing and other properties.

Quality of a product depends upon the application of materials, men, machines and manufacturing conditions. The systematic control of these factors is the quality control. The quality of a product differs greatly due to these factors. For example, a skilled worker will produce products of better quality and a less skilled worker will produce poor quality products.

Similarly better machines and better materials with satisfactory manufacturing conditions produce a better quality product. Thus, it is clear that to control the quality of product various factors which are responsible for quality are required to be controlled properly.

In the words of Alford and Beatly, “quality control” may be broadly defined as that “Industrial management technique by means of which products of uniform acceptable quality are manufactured.” Quality control is concerned with making things right rather than discovering and rejecting those made wrong.

“It may also be defined as the function or collection of duties which must be performed throughout the organisation in order to achieve its quality objective” or in the other words ‘Quality is every body’s business and not only the duty of the persons in the Inspection Staff.

Concluding, we can say that quality control is a technique of management for achieving required standard of products.

Factors Affecting Quality :

In addition to men, materials, machines and manufacturing conditions there are some other factors which affect the quality of product as given below:

(i) Market Research i.e. demand of purchaser.

(ii) Money i.e. capability to invest.

(iii) Management i.e. Management policies for quality level.

(iv) Production methods and product design.

Apart from these, poor packing, inappropriate transportation and poor after sales service are the areas which can cause damage to a company’s quality image. There are cases where goods of acceptable quality before transportation were downgraded on receipt by the retailer just because they had been damaged in transportation.

Modern quality control begins with an evaluation of the customer’s requirements and has a part to play at every stage from goods manufactured right through sales to a customer, who remains satisfied.

Essay # 2. Quality Control Organisation :

Over the years, the status of the quality control organisation changed from a function merely responsible for detecting inferior or standard material to a function that establishes what are termed preventive programmes.

These programmes are designed to detect quality problems in the design stage or at any point in the manufacturing process and to follow up on corrective action.

Immediate responsibility for quality products rest with the manufacturing departments. All the activities concerning product quality are usually brought together in the organisation which may be known as inspection, quality control, quality assurance department or any other similar name.

Quality control is a staff activity since it serves the line or production department by assisting them in managing quality. Since the quality control function has authority delegated by management to evaluate material produced by the manufacturing department, it should not be in a position to control or dictate to the quality activity.

The quality control organisation depending upon the type of product, method of quality is sufficient enough to carry out following activities:

1. Inspection of raw material, product or processes.

2. Salvage inspection to determine rejected part and assembly disposition.

3. Records and reports maintenance.

4. Statistical quality control.

5. Gauges for inspection.

6. Design for quality control and inspection.

7. Quality control system maintenance and development.

Functions of Quality Control Department :

Quality control department has the following important functions to perform:

1. Only the products of uniform and standard quality are allowed to be sold.

2. To suggest methods and ways to prevent the manufacturing difficulties.

3. To reject the defective goods so that the products of poor quality may not reach to the customers.

4. To find out the points where the control is breaking down and investigates the causes of it.

5. To correct the rejected goods, if it is possible. This procedure is known as rehabilitation of defective goods.

Essay # 3. Advantages of Quality Control :

There are many advantages by controlling the product quality.

Some of them are listed below:

1. Quality of product is improved which in turn increases sales.

2. Scrap rejection and rework are minimised thus reducing wastage. So the cost of manufacturing reduces.

3. Good quality product improves reputation.

4. Inspection cost reduces to a great extent.

5. Uniformity in quality can be achieved.

6. Improvement in manufacturer and consumer relations.

7. Improvement in technical knowledge and engineering data for process development and manufacturing design.

Essay # 4. Quality Control for Export :

Today we need foreign exchange for our requirements and for repayment of our debts and services. If our products are expensive and are of sub-standard quality then the customers abroad will not buy goods from us.

Therefore, we must be able to supply goods which may meet the requirements of foreign buyers. For this purpose quality and good packing determines to a large extent the continued acceptability of the product.

At present some organisations lite Export Inspection Council of India, the Indian Standards Institution, the Indian Society of Quality Control and the Indian Institute of Foreign Trade are helping about this problem of quality control.

Implementation of the Export Act 1963 and the work of Export Inspection Council (set up under Export Act) have helped in planned approach towards quality control. The advice of Export Inspection Council is very helpful for pre-shipment inspection of exportable goods.

These organisations have been authorised to issue a “Certificate of Quality” after satisfying themselves that the goods fulfill the minimum standards of quality laid down or that they are of the quality claimed by the exporter.

Essay # 5. Indian Standard Institution (I.S.I. Renamed as B.I.S.) :

To protect the interest of the consumers, Indian Standard Institution is serving in India. In most of the western countries, consumers nave formed their own associations to protect their interest. In some countries these associations, receive official support and guidance.

I.S.I, serves the consumers through Certification Marks Scheme. Under this scheme I.S.I, has been vested with the authority to grant licenses to manufacturers to apply the I.S.I, mark on their products in token of their conformity to the desired Indian Standards.

To control the quality, I.S.I, inspectors carry out sudden inspections of the factories of the licensee. Inspectors may check the incoming raw materials, outgoing finished products and may carry out necessary tests at different levels of control during production.

Thus I.S.I, mark gives guarantee to the purchaser that the goods with this mark have been manufactured under a well-defined system of quality control. From first April 1987 it has been renamed as Bureau of Indian Standards.

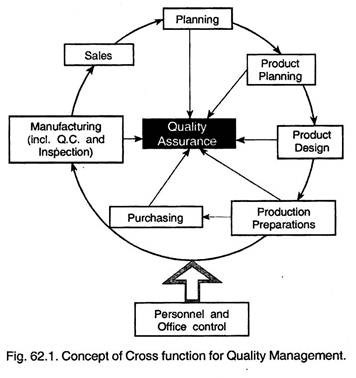

Essay # 6. Quality Assurance :

Inspection, quality control and quality assurance:.

Inspection is a process of sorting good from a lot. Whereas Quality Control is aimed at prevention of defects at the very source, relies on effective feedback system, and procedure for corrective action.

In Quality control programme, inspection data are used to take prompt corrective action to check the defects. For this purpose, detailed studies are conducted to find out that from where the defect is originated, and how to prevent it, may it be at manufacturing, design, purchase of raw materials, despatch or storage stage.

Quality Assurance means to provide the necessary confidence to the customer as well as to top management that all concerned are carrying out their job effectively and that the product quality is as per customer’s satisfaction with economy. Quality products can be produced only when all the departments fully participate and co-operate.

Presently, customers demand for higher quality and reliability. It has been felt that even a single defect whatever may be the reasons, result in economic loss.

These reasons have necessitated the need for total quality and reliability programmes to cover wide spectrum of functions and various areas of product design, production system design through various states of material, manufacture and commitment to efficient maintenance and operation of the system as a whole. This is necessary for quality assurance and reliability of the product. This assures the continuous failure free system to the customers.

Responsibilities of Quality Assurance Department :

i. Plan, develop and establish Quality policies.

ii. To assure that products of prescribed specification reaches to the customers.

iii. Regularly evaluate the effectiveness of the Quality programmes.

iv. Conduct studies and investigations related to the quality problems.

v. Liaise with different department, in and outside the organisation.

vi. Organise training programmes on quality.

vii. Plan and coordinate vendor quality surveys and evaluate their results.

viii. Develop Quality assurance system and regularly evaluate its effectiveness.

Quality Assurance System :

Quality assurance system should be developed incorporating the following aspects:

i. Formulate the quality control and manufacturing procedures.

ii. Percentage checking be decided.

iii. Procedures and norms for plant performances as regards to quality be developed.

iv. Rejection analysis and immediate feed-back system for corrective action.

v. Prepare a manual for quality assurance.

vi. Formulate plans for quality improvement, quality motivation and quality awareness in the entire organisation.

Essay # 7. Causes of Quality Failures :

Quality failures occur due to various causes, most of them are because of lack of involvement of men concerned with the quality. Studies have indicated that more than 50% of quality failures are due to human errors at various levels, such as understanding of customer’s requirements, manufacturing, inspection, testing, packaging and design etc.

Error affecting quality can be classified into following categories :

(a) Error Due to Inadvertence:

These are due to lack of knowledge of the product, and continue due to lack of information about quality deficiency. Such mistakes can be controlled, if a system for feedback is developed in which quality performance results are analysed in a regular and timely manner.

(b) Errors Due to Lack of Technique:

These errors are due to lack of knowledge, skill, technique etc. In such cases performance of ‘better’ operation are compared with those of ‘poor’ or ‘defect prone’ operations, and the process adopted by them are studied and reasons for errors are investigated.

(c) Willful Errors:

Sometimes quality is compromised due to early delivery schedules, reduction in cost, safety etc.

Reduction of Errors by Improved Motivation :

Quality motivational programmes are developed for getting quality product from the line staff so that they take interest in improving the quality. Motivational programmes are designed after identifying the sources/reasons of failures.

Operators are motivated by designing a campaign to secure alertness, awareness and new actions, and by observing the managers for their behaviours or reactions on any quality problem. Campaign can be launched through mass meetings, quality posters, exhibition of quality deficiencies etc.

Campaign may also invite operators to participate in analysing the causes of defects or the failure on the part of operation and/or systems. Trainings are very helpful in making the operators aware of the technological does and don’ts and the purpose behind each operation.

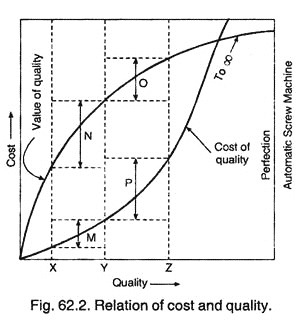

Essay # 8. Economics of Quality :

The good economic performance is the most essential for survival and growth of any organisation in the highly competitive environment. Therefore, one of the most common objections of every organisation is to attain excellence in its economic performance. The single most important factor which leads to good economic performance is the ‘quality’ of its products or services.

Therefore, in order to achieve economy, quality management system must contribute towards the establishment of customer-oriented quality discipline in the marketing, design, engineering, procurement, production, inspection, testing and other related servicing functions.