- About the Hub

- Announcements

- Faculty Experts Guide

- Subscribe to the newsletter

Explore by Topic

- Arts+Culture

- Politics+Society

- Science+Technology

- Student Life

- University News

- Voices+Opinion

- About Hub at Work

- Gazette Archive

- Benefits+Perks

- Health+Well-Being

- Current Issue

- About the Magazine

- Past Issues

- Support Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Subscribe to the Magazine

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

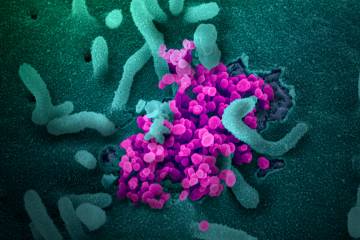

Credit: Getty Images

What is social distancing and how can it slow the spread of COVID-19?

Read the latest guidance from cdc and johns hopkins experts on measures to curtail the coronavirus outbreak.

By Katie Pearce

To slow the spread of COVID-19 through U.S. communities, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has encouraged Americans to practice "social distancing" measures. But what is social distancing, and how is it practiced?

For more information on the latest guidance, the Hub compiled information from the CDC and from Johns Hopkins experts Caitlin Rivers , an epidemiologist from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, and Tom Inglesby , the center's director. Here's what they had to say.

What is social distancing?

Social distancing is a public health practice that aims to prevent sick people from coming in close contact with healthy people in order to reduce opportunities for disease transmission. It can include large-scale measures like canceling group events or closing public spaces, as well as individual decisions such as avoiding crowds.

With COVID-19, the goal of social distancing right now is to slow down the outbreak in order to reduce the chance of infection among high-risk populations and to reduce the burden on health care systems and workers. Experts describe this as "flattening the curve," which generally refers to the potential success of social distancing measures to prevent surges in illness that could overwhelm health care systems.

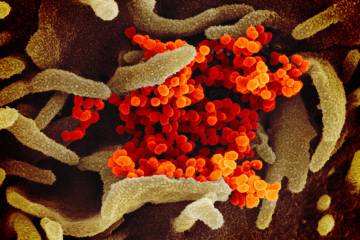

Image credit : Siouxsie Wiles and Toby Morris / Wikimedia Commons

"The goal of social distancing in the U.S. should be to lower the pace and extent of spread of COVID-19 in any given city or community," Inglesby wrote recently on Twitter . "If that can happen, then there will be less people with disease, and less people needing hospitalization and ventilators at any one time."

How do I practice social distancing?

The CDC defines social distancing as it applies to COVID-19 as "remaining out of congregrate settings, avoiding mass gatherings, and maintaining distance (approximately 6 feet or 2 meters) from others when possible."

This means, says Rivers, "no hugs, no handshakes."

It's particularly important—and perhaps obvious—to maintain that same 6-foot distance from anyone who is demonstrating signs of illness, including coughing, sneezing, or fever.

Along with physical distance, proper hand-washing is important for protecting not only yourself but others around you—because the virus can be spread even without symptoms.

"Don't wait for evidence that there's circulation [of COVID-19] in your community," says Rivers. "Go ahead and step up that hand-washing right now because it really does help to reduce transmission."

She recommends washing hands any time you enter from outdoors to indoors, before you eat, and before you spend time with people who are more vulnerable to the effects of COVID-19, including older adults and those with serious chronic medical conditions. ( See full CDC guidance on hand-washing techniques here .)

On the broader scale, a number of actions taken in recent days are designed to encourage social distancing, including:

- Schools, colleges, and universities suspending in-person classes and converting to remote online instruction

- Cities canceling events, including sporting events, festivals, and parades

- Workplaces encouraging or mandating flexible work options, including telecommuting

- Organizations and businesses canceling large gatherings, including conferences

- Houses of worship suspending services

"Community interventions like event closures play an important role," Rivers says, "but individual behavior changes are even more important. Individual actions are humble but powerful."

Does social distancing work?

Experts point to lessons from history that indicate these measures work, including those from the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic. A 2007 PNAS study found that cities that deployed multiple interventions at an early phase of the pandemic—such as closing schools and banning public gatherings—had significantly lower death rates.

The do's and don'ts of 'social distancing'

A chart of the 1918 spanish flu shows why social distancing works.

Although Inglesby says the concept has little modern precedent at a large scale, he points to an early study, not yet peer reviewed, showing the different experience of peak coronavirus rates for two Chinese cities. The city of Guangzhou, which implemented disease control measures early into the outbreak, had significantly lower numbers of hospitalizations from COVID-19 on its peak day than the city of Wuhan, which put measures in place a month into the outbreak.

Inglesby says people shouldn't fret about a "perfect" approach to social distancing: "It's a big country and we will need partial solutions that fit into different communities. A 75% solution to a social distancing measure may be all that is possible … [which] is a lot better than 0%, or forcing a 100% solution that will fail."

What are other ways to limit the spread of disease?

Other public health measures could include isolation and quarantine. According to the CDC's latest guidance:

Isolation refers to the separation of a person or people known or reasonably believed to be infected or contagious from those who are not infected in order to prevent spread of the disease. Isolation may be voluntary, or compelled by governmental or public health authorities.

Quarantine in general means the separation of a person or people reasonably believed to have been exposed to a communicable disease but not yet symptomatic from others who have not been so exposed in order to prevent the possible spread of the disease. With COVID-19, the CDC has recommended a 14-day period to monitor for symptoms.

The CDC offers more details on which populations face greater risks, and specific cautionary measures they should take.

Posted in Health

Tagged public health , global health , coronavirus

Related Content

Serum stopgap could slow COVID-19 spread

Study: COVID-19 symptoms start about five days after exposure

Hopkins experts present latest coronavirus information on Capitol Hill

Map tracks coronavirus outbreak

You might also like, news network.

- Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Get Email Updates

- Submit an Announcement

- Submit an Event

- Privacy Statement

- Accessibility

Discover JHU

- About the University

- Schools & Divisions

- Academic Programs

- Plan a Visit

- my.JohnsHopkins.edu

- © 2024 Johns Hopkins University . All rights reserved.

- University Communications

- 3910 Keswick Rd., Suite N2600, Baltimore, MD

- X Facebook LinkedIn YouTube Instagram

Social distancing: What it is and why it’s the best tool we have to fight the coronavirus

Professor of Medicine, Boston University

Disclosure statement

Thomas Perls does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Boston University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation US.

View all partners

- Bahasa Indonesia

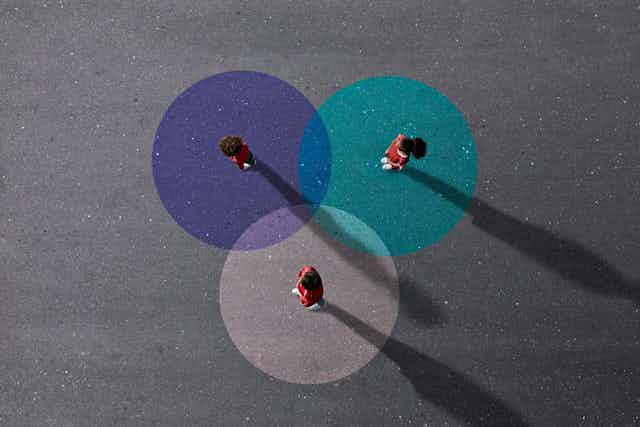

As the coronavirus spreads into more and more communities, public health officials are placing responsibility on individuals to help slow the pandemic. Social distancing is the way to do it. Geriatrician Thomas Perls explains how this crucial tool works.

What is social distancing?

Social distancing is a tool public health officials recommend to slow the spread of a disease that is being passed from person to person. Simply put, it means that people stay far enough away from each other so that the coronavirus – or any pathogen – cannot spread from one person to another.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention describes social distancing as staying away from mass gatherings and keeping a distance of 6 feet or 2 meters – about one body length – away from other people. In New York City, for example, theaters have closed temporarily , many conventions around the world are being canceled and schools are closing all across the U.S. I’ve stopped taking the train during rush hour. Now I either work from home or drive in with my wife, or I take the train during off-hours so I can maintain the 6-foot distance.

Social distancing also means not touching other people, and that includes handshakes. Physical touch is the most likely way a person will catch the coronavirus and the easiest way to spread it. Remember, keep that 6-foot distance and don’t touch.

Social distancing can never prevent 100% of transmissions, but by following these simple rules, individuals can play a critical role in slowing the spread of the coronavirus. If the number of cases isn’t kept below what the health care system can handle at any one time – called flattening the curve – hospitals could become overwhelmed, leading to unnecessary deaths and suffering.

There are a few other terms besides social distancing that you are likely to hear. One is “self-quarantine.” This means staying put, isolating yourself from others because there is a reasonable possibility you have been exposed to someone with the virus.

Another is “mandatory quarantine.” A mandatory quarantine occurs when government authorities indicate that a person must stay in one place, for instance their home or a facility, for 14 days. Mandatory quarantines can be ordered for people who test negative for the virus, but have likely been exposed . Officials have imposed mandatory quarantines in the U.S. for people on cruise ships and those traveling from Hubei province, China .

Why does social distancing work?

If done correctly and on a large scale, social distancing breaks or slows the chain of transmission from person to person. People can spread the coronavirus for at least five days before they show symptoms . Social distancing limits the number of people an infected person comes into contact with – and potentially spreads the virus to – before they even realize they have the coronavirus.

It’s very important to take a possibility of exposure seriously and quarantine yourself. According to recently published research, self-quarantine should last 14 days to cover the period of time during which a person could reasonably present with symptoms of COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. If after two weeks they still don’t have symptoms, then it’s reasonable to end the quarantine. Shorter quarantine periods could happen for asymptomatic people as tests to rule out the virus become widely available.

Why is social distancing so crucial?

At the moment, it’s the only tool available to fight the spread of the coronavirus.

Experts estimate that a vaccine is 12 to 18 months away . For now, there are no drugs available that can slow down a coronavirus infection.

Without a way to make people better once they fall sick or make them less contiguous, the only effective tactic is making sure hospital-level care is available to those who need it. The way to do that is to slow or stop the spread of the virus and decrease the number of cases at any one time.

Who should do it?

Everyone must practice social distancing in order to prevent a tidal wave of cases. I am a geriatrician who cares for the most vulnerable people: frail older adults . Certainly, such individuals should be doing all they can to protect themselves, diligently practicing social distancing and significantly changing their public ways until this pandemic blows over. People who are not frail need to do all they can to protect those who are, by helping to minimize their exposure to COVID-19.

If the public as a whole takes social distancing seriously, overwhelming the medical system could be avoided. Much of how the coronavirus pandemic unfolds in the U.S. will come down to individuals’ choices.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter .]

- Public health

- Coronavirus

- Coronavirus transmission

- Social distancing

Project Offier - Diversity & Inclusion

Senior Lecturer - Earth System Science

Sydney Horizon Educators (Identified)

Deputy Social Media Producer

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

The Ethics of Social Distancing

Nicholas G. Evans thinks through the tangle of rights and wrongs

If you’re reading this piece as it comes out, there’s a good chance you are reading it at home. That’s because you’re engaged, like so many of us, in social distancing as part of the broader response to coronavirus disease 2019, or COVID-19. As of the 8 th of May, 2020, 3.8 million people have been confirmed with the disease, and more than 261,000 have died. Of those deaths, more than a quarter have occurred in the United States.

Social distancing is an integral part of our response to this pandemic. Nonetheless, particular instances of social distancing, of which they are many, require some kind of ethical justification. That’s because like most public health measures, social distancing measures can interfere with individual freedoms, and cause harm. In this short essay I’ll ask what social distancing entails, why it raises ethical issues, and then finally what kind of social distancing measures are justified.

What is Social Distancing?

We’re all probably at the stage of knowing social distancing when we see it, because we’re living it day to day. But unlike quarantine -- the confinement of persons who are suspected to have been exposed to the disease -- social distancing isn’t well defined as a practice. That’s because social distancing isn’t a single thing. In fact, the use of “social distancing” as a catch all is fairly recent: in their 2004 planning for a return of SARS or a similar disease, for example, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention refer to “ measures to increase social distance ,” rather than “social distancing,” and those measures are extremely varied. The term social distancing seems to appear a few years later in the context of pandemic influenza , which gives you an idea of how recent the term is. That’s not to say that social distancing practices themselves are new. Jason Schwartz’s account of the turn to biomedical responses in public health shows us that until relatively recently, social distancing measures -- and “nonpharmaceutical interventions” in general -- were more or less all of public health.

Social distancing then, describes a wide range of practices. It includes stay-at-home orders by governments, which may be more or less enforced through curfews and travel restrictions; the shuttering of businesses, schools, and government offices; banning or restricting public gatherings; the use of masks in public; and the 6-foot separation recommendation many of you are familiar with in the case of COVID-19. These measures are merely physically distancing us. They are intended to remove points of interaction between us, and in particular between different subgroups of our community, to prevent a communicable disease from spreading between groups. Stopping people within families, for example, getting sick off each other is very labour intensive. But stopping transmission between families either through shared workspaces or schools can be effective at breaking chains of transmission in society.

Social distancing practices arguably include the design of social institutions, or even our environments. Mandated sick leave policies , among other employment rights, are effective forms of social distancing, and have been found to reduce flu infection rates. Urban architecture may also provide social distance: Bogotá is opening new bike lanes to further reduce the number on commuters on public transit, allowing individuals who can to use bicycles stay apart rather than use transit where they can be infected or transmit COVID-19 -- which also makes transit safer for those who can’t ride. People have been planning the physical shape of communities around infectious disease even before the advent of germ theory, such as Frank Olmstead’s design of Central Park.

Why Does Social Distancing Raise Ethical Issues?

Before dealing with the current controversy and its distinctive political elements, it’s worth asking why social distancing might raise ethical issues. The main reason it that social distancing can entail what the public health ethics literature sometimes refers to as a <href="#LibLimConCenTasPubHeaEth">liberty-limiting or liberty-restricting measures. That is, enacting public health measures that constitute social distancing can harm people, or infringe upon their freedoms in important ways.

Public health ethics hasn’t paid a lot of attention to social distancing measures, however. I think this is because social distancing differs from other public health measures in terms of the kinds of liberties it infringes upon. Quarantine is the paradigm of a liberty-limiting measure, because it directly and obviously restricts an individual’s freedom of movement in the name of public health. Rights to freedom of movement are recognised as fundamental human rights , though they aren’t unlimited in their scope. Moreover, insofar as our rights to freedom of movement constitutes a right to be free from interference in our movement, quarantine clearly infringes upon our freedom in some important way. So it requires a compelling justification.

On its face, social distancing doesn’t seem quite so bad. After all, social distancing need not require anyone to force you to stay at home. It might in some cases, but it’s definitely not an essential feature of social distancing measures. In some cases, social distancing might be effective without directly interfering with your movement at all. I’m sure a lot of you are currently familiar with the feeling that no one needs to force you to stay home, because there’s not really anywhere to go right now.

But I think that feeling points to a way social distancing impacts us in an important way, albeit one that is a little less obvious than quarantine (which involves locking someone or even many someones up). Applied broadly enough, and for enough time, social distancing can damage our ability to form communities, and limit our opportunities. It reveals that freedom of movement and freedom of association are, in small but deeply important ways, positive or welfare rights. That is, we have a right to community, and to travel, because doing so is deeply important for humans. We obviously don’t have absolute latitude in the kinds of community we can form (especially if others don’t want to form community with us!), but we have some minimal claim that is currently being infringed upon.

Moreover, the way these liberties were infringed upon -- particularly for people whose communities didn’t take the problem seriously at first, and then suddenly “ Cancelled Everything ”, this may seem like a form of domination . That is, the way some social distancing measures have been enacted has revealed the degree to which our employers, government, and other powerful actors in our lives have the arbitrary ability to close off our options, and potentially leave us without any recourse.

Social Distancing Kills

Social distancing can also hurt you. Again, not every measure we can use to increase social distance, and not every way of implementing the same measure, hurts us to the same degree. But social distancing can and does harm individuals. Those harms can be direct or indirect; proximate or long-term.

Direct and proximate harms of social distancing arise because social distancing itself is hurting them right now. These are the people who can’t get seen because acute care centres are closed, physicians aren’t taking new places, and getting care over the phone is hard. They are the folks who are having cardiac events and can’t get help. They might also be people form whom home is not safe, and now have nowhere else to go, including victims of domestic abuse. These are the people for whom the infringements and potential domination above is harming them in clear-cut ways.

Some are being indirectly harmed by social distancing arrangements right now. These are the “essential personnel” who are still expected to be on the job, but may lack the support that allows them to stay home if they are sick without losing their job, or who aren’t given appropriate protective gear. These are the people who we can’t afford to lose, and sometimes don’t permit to be socially distanced because they fulfil important roles in society. But they can be harmed just in case they’re expected to shoulder risk on our behalf in a way that isn’t a fair or proportionate form of sharing risk in society. Many of the ways they are put at risk, moreover -- access to paid leave, hazard pay, and protective gear -- are failures of our social institutions that predate COVID-19, often by decades.

People may be directly harmed by social distancing, but experience it as a slow burn. These are folks who won’t get screening fast enough to catch that cancer in its earliest stages, or who will live with chronic pain because they couldn’t get access to a physical therapist. Shutting down elective medical procedures will -- has -- harm people. It just won’t do it today, or tomorrow, but sometime in the future.

Finally, there are the people who are indirectly harmed by social distancing, over a long period of time. Some will struggle to make ends meet for years, even decades, because of the aggregate toll of social distancing and a slow recovery -- the folks caught up in the projected 15% unemployment in the USA for April 2020 who, even if only temporary, will be harmed. We know that income disparities and injustices kill; those who suffer the most deprivation under social distancing might weather this storm, but in doing so may borrow against the end of their life to get by.

The Ethics of Social Distancing: More Than a Binary

This is, then, where the rubber hits the road. Social distancing has clear benefits, and COVID-19 is an incredibly dangerous global pandemic. These measures slow the progress of the disease which takes pressure off the medical system, and reduces the overall number of infections. It could save millions of lives in the long run. It also has indirect benefits just as it has indirect harms: in the US, for example, road deaths are down.

On the other hand, it infringes on our liberties and imposes harms. It, moreover, arguably imposes harms, directly or indirectly, on some of the most vulnerable groups in society. The folks who benefit most from social distancing are people like me, and my colleagues in public health who have stable jobs that allow us to work from home. Folks who can’t work from home are the most at risk , and benefit the least from these measures.

Social distancing measures thus need to be necessary and effective in responding to the threat we face, proportionate, and minimally invasive and harmful relative to other options. What does that look like?

To start, the ongoing debate between social distancing and “reopening the economy” is false choice. That’s because social distancing isn’t one thing, and so we can layer measures, or not, as the need arises and as evidence dictates. But it’s also false choice because simply arguing based on the restrictiveness of social distancing measures -- between “Cancel Everything” and rescinding all measures that increase social distance -- ignores that in many cases the harms of social distancing can be ameliorated with appropriate policies. Not all, but many of the potential harms of social distancing measures are not endogenous to the measures themselves. People can, and should be supported during this time.

Finding ethically justified social distancing measures necessarily entails those supports. The reasons for this are broad. For the consequentialists, and particularly maximisers, the reasons are easy. Presented with a series of options, we ought to take the one that maximises expected global value (whatever we take that to be). Neither simply shutting down everything without support for those who might be harmed by social distancing, nor shutting down nothing/reopening, are going to top a maximiser’s list. Piecewise choices between two terrible options are false choices. Moreover, failing to maximise expected value, for those who subscribe to this, is unethical no matter how you slice it. It may be less unethical to shut everything down without these support measures, but it is still not maximising expected value and thus still fails to meet the demands of ethics.

For the deontologists among us, things can be a bit more varied. With the exception of the most devoted libertarians, however, it seems like most would subscribe to theories that mean that if it doesn’t cost us much (or anything), we ought to take on small risks to prevent others from coming to serious harm -- call this a limited “no means to harm” principle. This same principle, however, means that we should take on some costs (say, through the government) to prevent the most serious harms of social distancing.

Moreover, respecting others means understanding that for some, going to work might not be instrumentally irrational. It’s so easy for me to say, as an academic who can work from home (from anywhere, really), that all things considered I should stay home. But if I was faced with a set of choices that entailed either a nonzero, but potentially low chance of getting sick, and -- given at my age, the chances of dying from COVID-19 are quite low -- a nonzero but potentially low chance of progressing to serious disease and dying from COVID-19 if I am infected; or almost certainly losing my housing (and my family losing their housing) and other basic needs. There are lots of people in that situation, and if we’re committed to respecting the agency of others it seems like we should respect those people by giving them a reason to stay home that they can endorse.

It’s thus likely that most people would be committed to social distancing measures that support not just the most vulnerable, but everyone as they aid in defeating COVID-19 by staying home and staying apart. That mechanism has been achieved to greater or lesser degrees by different countries. But its clear there are basics that need to be in place as we go forward.

Ethical Social Distancing

The most obvious measures are those that reduce the time social distancing measures must be in force. This means comprehensive, accurate testing; ongoing contact tracing and monitoring; increased hospital capacities to pull the threshold of disaster back; and accurate seroprevalence studies to work out who has had the virus, so we have a better picture of where we are globally.

Less obvious, at least if you read the rapidly proliferating “roadmaps to reopening”, is attending to the most vulnerable in society. It is well understood that marginalised populations can become reservoirs for a disease because they are insufficiently protected. Sterling Johnson and Leo Beletsky have outlined how supporting harm reduction facilities can protect individuals suffering from substance abuse disorder and other diseases of despair, and support the pandemic response effort by preventing those marginalised communities from contracting and transmitting COVID-19. This is not only to the considerable benefit of those populations, but will also deprive the disease of places to lurk in our communities -- which, if we allow it, will only increase the time we live under comprehensive social distancing.

The next is to expand our concept of “frontline workers”, and support all those on all the front lines through hazard pay, more protective equipment and infection control, and better testing. I am referring to healthcare workers, yes, but also grocery store clerks, take out delivery drivers, food service workers, agricultural workers, workers on critical infrastructure, and major industries that we cannot or should not close. It is fashionable to refer to this outbreak as if it were a war. If that is true than the person at the grocery store or on a farm is as much on the front lines as a nurse, and -- assuming you enjoy eating as much as you enjoy hospitals -- deserves the same protection.

Next, propping up individuals and families whose economic futures hang in the balance should be done with minimal burden. In the USA, the $1200 individual pay-out has been slow to arrive , and is almost certainly insufficient given the length social distancing measures may last. In Australia, the JobKeeper program has been hampered by confusion and delays , some of which are part of the decades-long tradition of administrative hurdles introduced by conservative approaches to welfare. It is true that crisis demands we cut red tape, but we need to be cutting the right red tape, such as protecting people from entering into poverty, and ideally lifting people out of poverty to avoid the attendant and severe public health costs.

This goes the same for local businesses are threatened by the shutdown. The administrative hurdles presented by small business loans, globally, should be cut. The overall savings, if any, those hurdles imposed are almost certainly less than the benefits of preventing local economies from collapsing before the end of the ongoing shutdown.

Social distancing is absolutely necessary to stem the tide of COVID-19, and if some models are to be believed it could be years before those restrictions can be lifted indefinitely. Lots of people will suffer and die without it, but lots of people will suffer and die through it as well. There is no reason to choose one of those groups over the other, and ethical public health response requires attending to both. We don’t lack the skill or resources to accomplish this, only the political will. As such, we have an obligation to provide the most comprehensive support we can during this crisis.

Nicholas G. Evans is Assistant Professor of Philosophy at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. He maintains an active research program on the ethics of infectious disease, with a focus on clinical and public health decision making during disease pandemics. His edited volume, Ebola’s Message: Public Health and Medicine in the 21st Century focuses on the clinical, political, and bioethical impact of EVD.

You might also like...

The Transgender-Rights Issue

Of Our Great Propensity to the Absurd and Marvellous

The Art and Style of Crosswords

Woman as Resource: A Reply to Catharine MacKinnon

Women, Men and Criminal Justice

Philosophia

What Is the Philosophy of Madness?

Who Is Feminism For?

Subscribe to The Philosophers' Magazine for exclusive content and access to 20 years of back issues.

Most popular.

The Fact/Opinion Distinction

The Meaning of "Asshole"

Want to Be Good at Philosophy? Study Maths and Science

Do Animals Have Free Will?

Can Psychologists Tell Us Anything About Morality?

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 18 January 2021

Effects of social distancing on the spreading of COVID-19 inferred from mobile phone data

- Hamid Khataee 1 ,

- Istvan Scheuring 2 , 3 ,

- Andras Czirok 4 , 5 &

- Zoltan Neufeld 1

Scientific Reports volume 11 , Article number: 1661 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

13k Accesses

37 Citations

130 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Applied mathematics

- Infectious diseases

A better understanding of how the COVID-19 pandemic responds to social distancing efforts is required for the control of future outbreaks and to calibrate partial lock-downs. We present quantitative relationships between key parameters characterizing the COVID-19 epidemiology and social distancing efforts of nine selected European countries. Epidemiological parameters were extracted from the number of daily deaths data, while mitigation efforts are estimated from mobile phone tracking data. The decrease of the basic reproductive number ( \(R_0\) ) as well as the duration of the initial exponential expansion phase of the epidemic strongly correlates with the magnitude of mobility reduction. Utilizing these relationships we decipher the relative impact of the timing and the extent of social distancing on the total death burden of the pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Non-compulsory measures sufficiently reduced human mobility in Tokyo during the COVID-19 epidemic

Fine-grained data reveal segregated mobility networks and opportunities for local containment of COVID-19

Impacts of social distancing policies on mobility and COVID-19 case growth in the US

Introduction.

The COVID-19 pandemic started in late 2019 and within a few months it spread around the World infecting 9 million people, out of which half a million succumbed to the disease. As of June 2020, the transmission of the disease is still progressing in many countries, especially in the American continent. While there have been big regional differences in the extent of the pandemic, in most countries of Europe and Asia the initial exponential growth has gradually transitioned into a decaying phase 8 . An epidemic outbreak can recede either due to reduction of the transmission probability across contacts, or due to a gradual build up of immunity within the population. According to currently available immunological data 1 , 2 at most locations only a relatively small fraction of the population was infected, typically well below 10%, thus the receding disease mostly reflects changes in social behavior and the associated reduction in disease transmission. Changes in social behavior can include state-mandated control measures as well as voluntary reduction of social interactions. However, especially with the view of potential future outbreaks, it is important to better understand how the timing and extent of social distancing impacted the dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Previous studies estimated the effect of social distancing on the dynamics of COVID-19 pandemic either by direct data analysis or by modeling methods 7 , 15 , 16 , 17 . A statistical analysis of the number of diagnosed cases, deaths and patients in intensive care units (ICU) in Italy and Spain have indicated that the epidemic started to decrease only after the introduction of strict lock-down action 3 . This was especially visible in Italy, where the final strict social distancing has been reached in a number of consecutive steps. A statistically more comprehensive analysis of hospitalized and ICU patients in France identified a 77% decrease in the growth rate of these numbers after the introduction of the lock-down 4 . The comparison of social distancing efforts in China, South Korea, Italy, France, Iran and USA 5 revealed that the initial doubling time of identified cases was about 2 days which was prolonged substantially by the various restrictions introduced in these countries. Epidemic models are widely used to estimate how various intervention strategies affect the transmission rate, however, the quantitative relationship between social interventions and epidemic parameters are hardly known 6 , 7 .

In this paper, we quantitatively characterise the time course of the COVID-19 pandemic using daily death data from nine selected European countries 8 . Statistical data on COVID-19-related deaths are considered to be more robust than that of daily cases of new infections. The latter is affected by the number of tests performed as well as by the testing strategy – e.g. its restriction to symptomatic patients – which may be highly variable across countries and often changes during the course of the epidemic. The time course of daily deaths can be considered as a more reliable indirect delayed indicator of daily infections. We thus do not address apparent differences in the case fatality ratio, and restrict our focus to the recorded COVID-19-associated death toll.

Our choice of countries was motivated by the requirements that each of these countries (i) had a relatively large disease-associated death toll (i.e. typically above 10/day and more than 2000 overall) so we can assume that the deterministic component of the epidemic dynamics dominates over random fluctuations. (ii) The selected countries spent a suitably long time in the decaying phase of the epidemic, thus allowing its precise characterisation. Based on these two criteria, we analysed data from the following, socio-economically similar countries, each implementing a somewhat distinct social distancing response: Italy, Spain, France, UK, Germany, Switzerland, Netherlands, Belgium and Sweden.

To characterise social distancing responses we used mobile phone mobility trend data from Apple Inc. 9 . Our aim is to quantitatively determine the characteristic features of the progression of the epidemic, such as initial growth rate, timing of the peak, and final decay rate and investigate how these parameters are determined by the timing and strictness of social distancing measures. We demonstrate that the overall death burden of the epidemic can be well explained by both the timing and extent of social distancing, often organized voluntarily well in advance of the state-mandated lock-down, and present quantitative relationships between changes in epidemiological parameters and mobile phone mobility data.

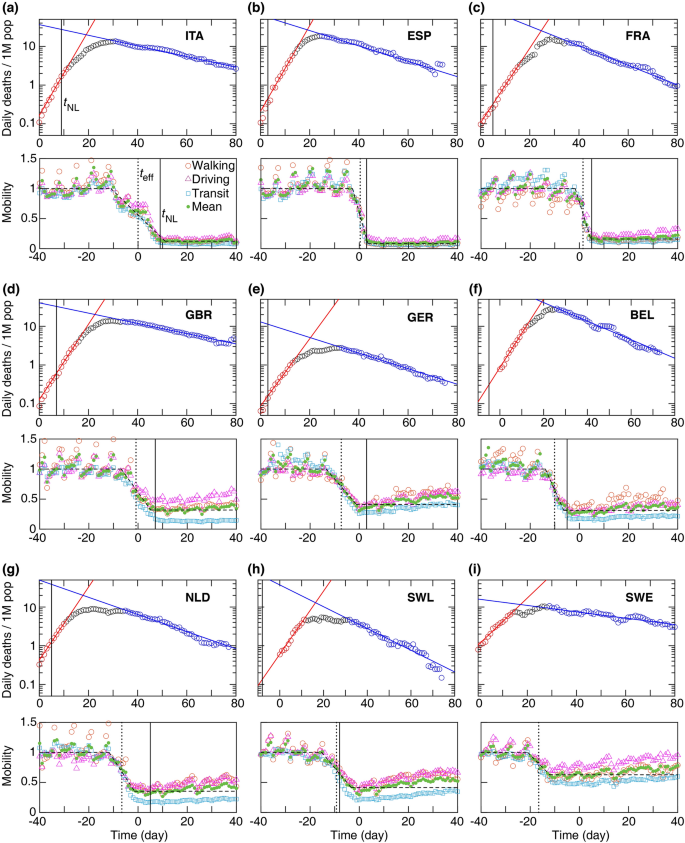

Characterization of the epidemic

Daily COVID-19 death data, D ( t ), is presented in Fig. 1 for the nine countries analysed. We selected the t = 0 reference time point as the date when the daily death rate first exceeded 5 deaths. In each country D ( t ) indicates the presence of a well defined exponential growth phase, followed by a crossover region and later an exponential decay stage. The initial growth and final decay regions are characterized by fitting the exponential \({\tilde{D}}(t)\) as

where the fitted functions are distinguished from the actual time series using a tilde. \(R_0\) is the basic reproductive number (i.e. number of new secondary infections caused by a single infected in a fully susceptible population) based on a simple SIR dynamics 10 and \(\gamma \) is the inverse average duration of the infectious period. For calculating the basic reproductive number we use \(\gamma = 0.1\; \text{day}^{-1}\) . The exact value of \(\gamma \) is somewhat uncertain at present 11 , 12 , however our analysis and results do not rely on the value of this parameter or on any modelling assumption regarding the disease dynamics.

To characterize the growth and decay phases, the values of \(R_{0_1}\) and \(R_{0_2}\) are approximated, respectively, by fitting Eq. ( 1 ) to the death data points (see Fig. 1 ). Least-squares fitting of Eq. ( 1 ) was performed using Mathematica (version 11, Wolfram Research, Inc.) routine NonlinearModelFit; see Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. The initial growth rate \(R_{0_1}\) is similar in the selected countries except in Sweden where it is substantially lower. This difference may reflect weaker social mixing, different cultural habits or a somewhat lower population density – an interesting problem outside of the scope of this report. The reproductive number in the decaying phase \(R_{0_2}\) is more variable across the different countries: in particular the decay is significantly slower in Sweden and somewhat slower in the UK.

A third parameter characterizes the transition from the growth to decay phases, i.e., the peak of the epidemic in terms of deaths. We define \((t_c,{\tilde{D}}_c)\) as the intersection point of the two fitted exponential functions. This is a more robust estimator than the actual maximum in daily deaths \(D_c\) as at the time of transition daily deaths can exhibit a plateau, hence the value and location of the maximum is sensitive to stochastic fluctuations. The gradual transition from exponential growth to decay in the actual data D ( t ) can be due to gradual implementation of social distancing as well as to the case-to-case variability of the time elapsed from infection to death.

The total death toll of the disease can be estimated analytically using the three parameters \(\alpha _1=(R_{0_1}-1)\gamma \) , \(\alpha _2=(1-R_{0_2})\gamma \) and \({\tilde{D}}_c\) as

Approximations by Eq. ( 2 ) are compared with the actual total death toll, \(D_{\text{tot}}\) , calculated as the area under death data points added to the area under the decaying curve (blue curve in Fig. 1 ) approaching zero. As Fig. 2 demonstrates, despite the substantial variation in death toll among the nine countries, it can be fairly well estimated by the expression ( 2 ). Specifically, details of the cross-over region, which do not fit well to the two exponential functions, contribute only around 10% to the overall death toll, while variations in the three epidemiological parameters ( \(R_{0_1}, R_{0_2}, t_c\) ) can change the death burden by an order of magnitude.

Daily death and mobility data for 9 European countries ( a – i ). Time 0 corresponds to the day when a country first reported \(\ge \) 5 daily deaths. Top: Growth and decay phases (red and blue lines) were fitted using Eq. ( 1 ) to the data points visually highlighted by red and blue, respectively. Vertical line: national lock-down date \(t_{\text{NL}}\) . Bottom: Mobile phone tracking data, normalized by the average values before the epidemic ( \(M_1\) ). Quantitative parameters were extracted by a fit (dashed line) to the mean mobility data (green circles, average of walking, driving, and transit data) calculated using Eq. ( 3 ). Dotted vertical line indicates the effective lock-down date \(t_{\text{eff}}\) calculated using Eq. ( 4 ). Fit parameters are summarised in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 .

Analytical estimate of the total number of COVID-19 deaths \({\tilde{D}}_{\text{tot}}\) versus \(D_{\text{tot}}\) , the actual total death toll ( a ). ( b ) The same data are presented as per million (1M) population. The dashed and solid lines represent the identity and a linear regression, respectively. The slope of the linear regression is \(0.85 \pm 0.01\) ( a ) and \(0.84 \pm 0.02\) ( b ). Pearson coefficients of determination are ( a ) \(r^2 = 0.99\) \((p < 0.001)\) and ( b ) \(r^2 = 0.98\) \((p < 0.001)\) . Statistical data analysis was performed using MATLAB (version 2017b, The MathWorks, Inc.).

Characterization of social distancing

The timing and strictness of the often voluntary social distancing is quantified from the average mobility data (green circles in Fig. 1 ), by fitting the following piece-wise linear function:

where \(M_1\) and \(M_2\) are the average mobility levels before and after social distancing (i.e., before \(t_1\) and after \(t_2\) ), respectively. To fit Eq. ( 3 ) to the mobility data, we used the data recorded over 90 days starting from 13-January-2020. The mobility data show a relative daily volume of requests made to Apple Maps for directions by transportation type per country compared to a baseline volume on 13-January-2020. Data is sent from users’ devices to the Apple Maps service and is associated with randomised rotating identifiers so that Apple does not have a profile of individual movements and searches. The availability of data in a particular country is subject to a number of factors, including minimum thresholds for direction requests made per day. A day is defined as midnight-to-midnight, US Pacific time 9 . Although the mobility data may have bias in the mobility signal, it may have relatively little direct effect on data reported for the countries studied here. In the 90-day period considered in this study, the data indicates the mobility levels before and after implementing the social distancing. For clarity, to set a unique time-scale for the mobility data for all the countries, we added more data points after \(t_2\) in Fig. 1 . These additional data points were not used in the fitting. The walking, driving and transit data are first averaged, then Eq. ( 3 ) was fitted to the average mobility level using Mathematica routine NonlinearModelFit. The fitted values of \(t_1, M_1, t_2\) , and \(M_2\) are listed in Supplementary Table 3. The mobility data with average pre-pandemic value scaled to unity, \(M(t)/M_1\) , is shown in Fig. 1 . We characterize the extent of social distancing by the ratio \(\mu =M_2/M_1<1\) . A strict restriction of social interaction is expected to be reflected as \(\mu \approx 0\) .

Using the fitted parameters \(t_1\) and \(t_2\) obtained from Eq. ( 3 ), an effective social distancing date is approximated. The mobility data shows a transition period in dropping the mobility level due to the social distancing. We define the midpoint of this transition period as an approximation for the average date when the social distancing becomes effective, given by:

The Supplementary Table 3 summaries the approximated \(t_{\text{eff}}\) . It is noteworthy that \(t_{\text{eff}}\) often preceded the official national lock-down \(t_{\text{NL}}\) .

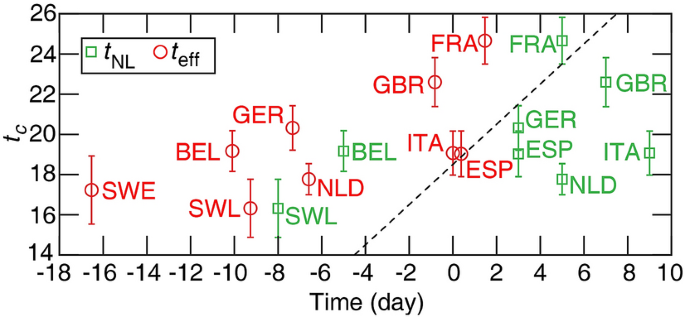

The effect of social distancing on epidemic parameters

Next, we investigate how the timing and extent of the social distancing changes the epidemic parameters, and as a consequence, the total death toll. First, we note that surprisingly neither the date of the official national lock-down \(t_{\text{NL}}\) nor the effective date of social distancing predicts well – in itself – the time of the epidemic peak \(t_c\) (Fig. 3 ). As the average time between infection and succumbing to COVID-19 is 18 days 13 , a delay of approximately 18 days is expected (dashed line in Fig. 3 ) between the introduction of social distancing and the change in the trend of the daily death count. Instead, we find that the time to the peak from the official national lock-down \(t_c-t_{\text{NL}}\) varies in a range from 10 days in Italy to more than 3 weeks in case of Switzerland, and the time from the change in mobility to the peak, \(t_c-t_{\text{eff}}\) , ranges from 19 days (Italy and Spain) up to 34 days (Sweden) as shown in Table. 1 .

The time of the peak in daily deaths \(t_c\) versus the official national lock-down date \(t_{\text{NL}}\) and the effective social distancing date \(t_{\text{eff}}\) . The correlation is weak with \(r^2= 0.45\) ( \(p = 0.06\) ) for \(t_{\text{eff}}\) , and \(r^2=0.12\) ( \(p = 0.37\) ) for \(t_{\text{NL}}\) . Neither correlations are statistically significant. Dashed line: time (identity line) with a delay of 18.5 days. Error bars indicate standard error (SE).

Furthermore, neither the time of the peak \(t_c\) nor the parameters characterising the time and strength of social distancing \(t_{\text{eff}}, t_{\text{NL}}\) , \(\mu \) correlates—as a single parameter—well with the total number of deaths (Fig. 4 ). For example, Belgium registers a very high per capita death toll despite an early official lock-down, 5 days before the reference time \(t=0\) , and even earlier change is observed in mobility data ( \(t_{\text{eff}} = -10\) days). On the other hand, a moderate social distancing in Germany, indicated by the mobility ratio \(\mu = 0.4\) , led to the lowest death toll within this group of countries. Thus, we decided to investigate more carefully how social distancing affects the three epidemic parameters \(R_{0_1}\) , \(R_{0_2}\) and \({\tilde{D}}_c\) —with the hypothesis that the non-linear, multi-factor relationship ( 2 ) effectively masks correlations between the death toll and any single control parameter.

Actual total number of deaths per million (1M) population versus mean \(t_{\text{c}}\) , the peak time of daily deaths ( a ), \(t_{\text{NL}}\) national lock-down date ( b ), \(t_{\text{eff}}\) effective lock-down date ( c ), and \(1 - \mu \) , the relative mobility drop ( d ). Pearson correlation coefficients are ( a ) \(r^2 = 0.01\) ( \(p = 0.77\) ), ( b ) \(r^2 = 0.06\) ( \(p = 0.52\) ), ( c ) \(r^2 = 0.002\) ( \(p = 0.92\) ), and ( d ) \(r^2 = 0.04\) \((p = 0.62)\) indicating that there is no statistically significant correlation among these epidemic characteristics.

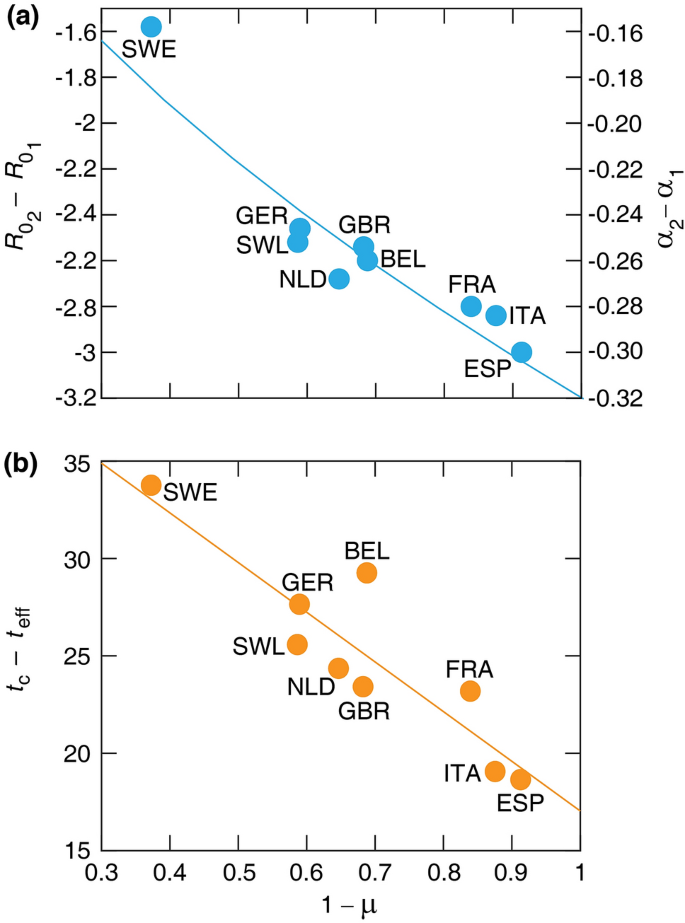

As Fig. 5 indicates, we found two strong relationships between the epidemiological parameters and measures of social distancing. Figure 5 a indicates a strong positive correlation between the drop in basic reproductive number, \(R_{0_1}-R_{0_2}\) and the restriction of mobility \(\mu \) . The relationship can be well approximated by the quantitative formula:

with \(\rho =0.56 \pm 0.09\) and \(\zeta = 3.18 \pm 0.11\) . Furthermore, the time elapsed between the peak and the social distancing, \(t_c-t_{\text{eff}}\) , correlates negatively with the severity of the mobility restrictions (Fig. 5 b) as

where \(\tau _0 = 17.04 \pm 1.62\) days is comparable with the mean value of the time from infection to death in fatal COVID-19 disease 13 , and \(\eta =1.50 \pm 0.40\) is the factor characterizing the lengthening of the delay for less severe reduction of mobility. Thus, the peak follows strict lock-downs (small \(\mu \) as in Italy and Spain) by around 18 days. For less restrictive social distancing ( \(\mu \approx 0.6\) as in Sweden), however, the peak can be delayed by as much as 5 weeks. This delay is of crucial importance, as the peak of the daily death toll \({\tilde{D}}_c\) is determined as

where \({\tilde{D}}(t_{\text{eff}})\) is a natural measure of how early the social distancing took place relative to the dynamics of the epidemic. As \({\tilde{D}}(t)\) is the exponential fit equation ( 1 ) instead of the actual daily death count D ( t ), unfortunately it is difficult to know in real-time. The country-specific values of \({\tilde{D}}(t_{\text{eff}})\) are listed in Table 2 .

Relationships between key parameters of the COVID-19 pandemics and mobility data. ( a ) Change of basic reproductive number \(R_{0_2} - R_{0_1}\) (left axis) and \(\alpha _2 - \alpha _1\) (right axis) versus the mobility drop \(1 - \mu \) . Solid line indicates a power-law fit \(-\zeta (1- \mu )^\rho \) , where \(\zeta = 3.18 \pm 0.11\) and \(\rho =0.56\pm 0.09\) . \(r^2=0.85\) , \((p = 0.0005)\) . ( b ) Elapsed time between the epidemic peak and the effective lock-down, \(t_c - t_{\text{eff}}\) , versus the mobility drop \(1 - \mu \) . Solid line indicates the linear fit Eq. ( 6 ), where \(\tau _0 = 17.04 \pm 1.62\) and \(\eta = 1.50 \pm 0.40\) .

Our analysis thus indicates that social distancing has two effects: it reduces the basic reproduction number of the infection as expected, and shortens the time required for the epidemic to peak. This latter effect is unexpected, as changes in behavior should reduce transmission immediately, which, after a fixed delay – involving manifestation of symptoms and in a fraction of the patients death – should also appear in the daily death toll D ( t ). We propose that the increased time between the peak and the time of the social distancing may indicate the presence of subpopulations in which the disease continues to propagate with the initial reproduction number \(R_{0_1}\) . In these populations the transmission is eventually blocked, not by the overall social distancing efforts within the society, but by some other means. As a potential mechanism, we suggest that the local outbreak can reach such a magnitude that it either triggers an intervention or allows the establishment of herd immunity. Prominent examples of such events that collectively expand the duration of the initial growth phase are outbreaks in nursing homes, meat processing plants, warehouses and prisons – which become more likely when the overall social distancing is weak. Furthermore, weak overall social distancing could also fail to protect and segregate these vulnerable subpopulations specifically, thus increase the effective size of such subpopulations.

In this paper we analysed the interdependence of epidemic and mobility data and identified a quantitative relation between parameters of social distancing and key characteristics of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our sample consisted of 9 European countries where suitable data was available at current time. We found that the total death toll does not correlate well with any single parameter such as the timing of the official lock-down or the strictness of social distancing extracted from mobile phone location data. The total death toll, however, could be well estimated by a non-linear combination of three parameters: exponents characterising (i) the initial exponential growth rate (or reproductive number, \(R_{0_1}\) ) and (ii) the final decay rate of the epidemic, \(R_{0_2}\) , and (iii) the peak death rate \({\tilde{D}}_c\) which separates the two stages. The initial growth rate is an intrinsic parameter which may vary somewhat across different countries, but is not affected by control measures or social responses to the pandemic. Based on our data analysis we find that the two remaining parameters, \(R_{0_2}\) and \({\tilde{D}}_c\) can be related to the timing ( \(t_{\text{eff}}\) ) and strength ( \(\mu \) ) of social distancing.

Since the estimated daily death toll at the peak increases exponentially with the difference between the effective lock-down time ( \(t_{\text{eff}}\) ) and time of the peak ( \(t_c\) ), small changes in \(t_c-t_{\text{eff}}\) can yield substantial differences in the total death toll. The per capita values of \({{\tilde{D}}}(t_{\text{eff}})\) are fairly similar: within the range 0.1-0.16 for 7 of the countries analysed, suggesting that social distancing started at similar stages of the epidemic. The important exception is Germany, where a much smaller value of 0.02 corresponds to roughly a week earlier response. According to the analysis presented here, this explains the substantially lower German death toll, in spite of the relatively moderate social distancing. The slightly higher value of \({{\tilde{D}}}(t_{\text{eff}})\) /population in Spain (0.23) was compensated by a strict lock-down (lower \(\mu \) ).

The higher death toll in Belgium cannot be explained by the proposed set of parameters ( \(R_{0_1}, D(t_{\text{eff}}), \mu \) ) as all three values are close to the average of the sample. This anomaly can be traced to Fig. 5 (b), where the deviation of the Belgian data point from the fitted curve indicates that the peak of the epidemic was delayed by approximately 4 days compared to what could be expected based on the proxy measure for social distancing \(\mu \) . While the high Belgian death toll is often attributed to the different methodology of recording COVID-19 related fatalities, including suspected deaths which were not confirmed by lab analysis, such a difference in methodology cannot explain the markedly high time distance between the effective date of social distancing ( \(t_{\text{eff}}\) ) and the epidemic peak ( \(t_{c}\) ); see Fig. 5 (b). As we propose that \(t_c-t_{\text{eff}}\) reflects the presence of subpopulations in which the disease can spread unmitigated by social distancing efforts, we suggest that such groups were relatively larger in Belgium than in the other countries within our sample.

While in the case of Sweden the initial growth rate was the slowest and even the timing ( \(D(t_{\text{eff}})\) ) was similar to other countries the weakness of the mobility restriction (i.e. large \(\mu \) ) led to high death toll resulting from a strongly delayed peak. We would like to emphasize, that this delay was unexpected at the time of social distancing efforts, and still unaccounted by the typical SIR-based epidemiological models 10 .

In the case of the UK the timing of the social distancing ( \(D(t_{\text{eff}})\) ) is similar to other countries, however the mobility restriction appears to be weaker (i.e. higher \(\mu \) ) compared to similar countries (Spain, Italy and France) which results in a slower decay of the epidemic.

The phone mobility data is an indirect measure of the social distancing and disease transmission probabilities. However, it can be compared to more traditional measures in the Netherlands, where a study directly determined the number of daily personal interactions before and after the lock-down. Using questionnaires, the study identified a 71% decrease in interactions on average, which is fairly close to the 65% drop estimated from the phone mobility data 14 . While mobile phone tracking data thus can characterize the relatively early stages of social distancing efforts, it may be less useful to detect more subtle efforts like wearing masks or staggered working shifts at later stages of the pandemic.

In conclusion, we demonstrated a quantitative relation between social distancing efforts and statistical parameters describing the current COVID-19 pandemic. We identified an unexpected extension of the exponential growth phase when social distancing efforts are weak, which can substantially increase the death toll of the disease. Future studies are required to extend this analysis to countries with a markedly different socio-economical arrangements.

Data availability

The datasets analysed in the manuscript are publicly available, see References 8 , 9 .

Brotons, C., Serrano, J., Fernandez, D., Garcia-Ramos, C., Ichazo, B., Lemaire, J., Montenegro, P. et al . Seroprevalence against COVID-19 and follow-up of suspected cases in primary health care in Spain. medRxiv (2020).

Jacqui, W. Covid-19: surveys indicate low infection level in community. BMJ 369 , m1992 (2020).

Google Scholar

Tobías, A. Evaluation of the lockdowns for the SARS-CoV-2 epidemic in Italy and Spain after one month follow up. Sci. Total Environ. 725 , 138539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138539 (2020).

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Salje, H., Kiem, C. T., Lefrancq, N., et al . Estimating the burden of SARS-CoV-2 in France [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 13]. Science . https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abc3517 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hsiang, S. et al. The effect of large-scale anti-contagion policies on the COVID-19 pandemic. Nature . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2404-8 (2020).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Flaxman, S. et al. Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2405-7 (2020).

Giordano, G. et al. Modelling the COVID-19 epidemic and implementation of population-wide interventions in Italy. Nat. Med. 26 , 855–860. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0883-7 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ritchie, H., Ortiz-Ospina, E., Beltekian, D., Mathieu, E., Hasell, J., Macdonald, B., Giattino, C., \& Roser, M. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Published online at OurWorldInData.org. https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus (2020).

https://www.apple.com/covid19/mobility .

Anderson, R. M. & May, R. M. Infectious Diseases of Humans: Dynamics and Control (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1992).

Bi, Q., Wu, Y, Mei, S., et al. Epidemiology and transmission of COVID-19 in 391 cases and 1286 of their close contacts in Shenzhen, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. . https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30287-5 (2020).

He, X., Lau, E. H. Y., Wu, P., et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 26 , 672–675. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5 (2020).

Zhou, F., Yu, T., Du, R., et al . Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study [published correction appears in Lancet. 2020 Mar 28;395(10229):1038]. Lancet 395 (10229):1054–1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Backer, J. A., Mollema, L., Klinkenberg, D., van der Klis, F. R., de Melker, H. E., van den Hof, S. & Wallinga, J. The impact of physical distancing measures against COVID-19 transmission on contacts and mixing patterns in the Netherlands: repeated cross-sectional surveys. medRxiv . https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.18.20101501 (2020).

Article Google Scholar

Kucharski, A. J. et al. Early dynamics of transmission and control of COVID-19: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 20 (5), 553–558 (2020).

Neufeld, Z., Khataee, H., & Czirok, A. Targeted adaptive isolation strategy for COVID-19 pandemic. Infect. Dis. Model. 5 , 357–361 (2020).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Dandekar, R. A., Henderson, S.G., Jansen, M., Moka, S., Nazarathy, Y., Rackauckas, C., Taylor, P. G., & Vuorinen, A. Safe blues: a method for estimation and control in the fight against COVID-19. medRxiv . https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.04.20090258. (2020).

Download references

Acknowledgements

IS was supported by GINOP 2.3.2-15-2016-00057 and the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (OTKA, K128289). AC was supported by the Hungarian Scientific Research Fund (OTKA, ANN 132225).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Mathematics and Physics, The University of Queensland, St. Lucia, Brisbane, QLD 4072, Australia

Hamid Khataee & Zoltan Neufeld

Evolutionary Systems Research Group, Centre for Ecological Research, Tihany, 8237, Hungary

Istvan Scheuring

MTA-ELTE Theoretical Biology and Evolutionary Ecology Research Group, Eotvos University, Budapest, 1117, Hungary

Department of Biological Physics, Eotvos University, Budapest, 1053, Hungary

Andras Czirok

Department of Anatomy and Cell Biology, University of Kansas Medical Center, Kansas City, KS, 66160, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the data analysis and to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Zoltan Neufeld .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Khataee, H., Scheuring, I., Czirok, A. et al. Effects of social distancing on the spreading of COVID-19 inferred from mobile phone data. Sci Rep 11 , 1661 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81308-2

Download citation

Received : 02 September 2020

Accepted : 21 December 2020

Published : 18 January 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81308-2

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Impact of national culture on the severity of the covid-19 pandemic.

- Yasheng Chen

- Mohammad Islam Biswas

Current Psychology (2023)

Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the pediatric infectious disease landscape

- Moshe Shmueli

- Idan Lendner

- Shalom Ben-Shimol

European Journal of Pediatrics (2023)

Human behaviour, NPI and mobility reduction effects on COVID-19 transmission in different countries of the world

- Zahra Mohammadi

- Monica Gabriela Cojocaru

- Edward Wolfgang Thommes

BMC Public Health (2022)

Novel mobility index tracks COVID-19 transmission following stay-at-home orders

- Peter Hyunwuk Her

- Sahar Saeed

- Sahir R Bhatnagar

Scientific Reports (2022)

Scheduling Diagnostic Testing Kit Deliveries with the Mothership and Drone Routing Problem

- Hyung Jin Park

- Reza Mirjalili

- Gino J. Lim

Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems (2022)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: AI and Robotics newsletter — what matters in AI and robotics research, free to your inbox weekly.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

We Need Social Solidarity, Not Just Social Distancing

To combat the coronavirus, Americans need to do more than secure their own safety.

By Eric Klinenberg

Dr. Klinenberg is a sociologist.

Social distancing — canceling large gatherings, closing schools and offices, quarantining individuals and even sequestering entire cities or neighborhoods — seems to be the best way to slow the spread of the coronavirus. But it’s a crude and costly public health strategy. Shuttering shared spaces and institutions means families lose child care, wages and social support. What’s more, it’s insufficient to protect the older, sick, homeless and isolated people who are most vulnerable to the virus. They need extra care and attention to survive, not society’s back.

I learned this firsthand while studying another recent health crisis , the great Chicago heat wave of 1995. In that event, as in so many other American disasters, social isolation was a leading risk factor and social connections made the difference between life and death.

In Chicago, social isolation among older people in poor, segregated and abandoned neighborhoods made the heat wave far more lethal than it should have been. Some 739 people died during one deadly week in July, even though saving them required little more than a cold bath or exposure to air-conditioning. There was plenty of water and artificial cooling available in the city that week. For the truly disadvantaged, however, social contact was in short supply.

Good governments can mitigate damage during health crises by communicating clearly and honestly with the public and providing extra service and support to those in need. But as the heat settled into Chicago, the mayor focused more on public relations than public health. He neglected to issue an official emergency or call in additional paramedics until it was too late. He publicly challenged the medical examiner’s reports that hundreds were dying from heat. In news conferences, he insisted that his administration was doing everything possible. His health service commissioner blamed those who died for neglecting to take care of themselves.

It’s chilling, how familiar this seems. And it’s disturbing, how little we’ve heard about helping the people and places most threatened by the coronavirus, about the ways in which, amid so much isolation, we can offer a hand.

In addition to social distancing, societies have often drawn on another resource to survive disasters and pandemics: social solidarity, or the interdependence between individuals and across groups. This an essential tool for combating infectious diseases and other collective threats. Solidarity motivates us to promote public health, not just our own personal security. It keeps us from hoarding medicine, toughing out a cold in the workplace or sending a sick child to school. It compels us to let a ship of stranded people dock in our safe harbors, to knock on our older neighbor’s door.

Social solidarity leads to policies that benefit public well-being, even if it costs some individuals more. Consider paid sick leave. When governments guarantee it (as most developed democracies do), it can be a burden for employers and businesses. The United States does not guarantee it, and as a consequence many low-wage American workers, even in the food service industry , are on the job when they’re contagiously ill.

It’s an open question whether Americans have enough social solidarity to stave off the worst possibilities of the coronavirus pandemic. There’s ample reason to be skeptical. We’re politically divided, socially fragmented, skeptical of one another’s basic facts and news sources. The federal government has failed to prepare for the crisis. The president and his staff have repeatedly dissembled about the mounting dangers to our health and security. Distrust and confusion are rampant. In this context, people take extreme measures to protect themselves and their families. Concern for the common good diminishes. We put ourselves, not America, first.

But crises can be switching points for states and societies, and the coronavirus pandemic could well be the moment when the United States rediscovers its better, collective self. Ordinary Americans, regardless of age or party, already have abundant will to promote public health and protect the most vulnerable. Although only a fraction of us are old, sick or fragile, nearly all of us love and care for someone who is.

Today Americans everywhere are worried about the fate of friends and family members. Without stronger solidarity and better leadership, though, millions of our neighbors may not get the support they need.

We’re not likely to get better leadership from the Trump administration, but there’s a lot we can do to build social solidarity. Develop lists of local volunteers who can contact vulnerable neighbors. Provide them companionship. Help them order food and medications. Recruit teenagers and college students to teach digital communications skills to older people with distant relatives and to deliver groceries to those too weak or anxious to shop. Call the nearest homeless shelter or food pantry and ask if it needs anything.

Why not begin right now?

Eric Klinenberg ( @EricKlinenberg ) is a professor in the social sciences at New York University and the author of “Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Us Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram .

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- Backchannel

- Newsletters

- WIRED Insider

- WIRED Consulting

Hilda Bastian

Social Distancing Has Become the Norm. What Have We Learned?

United States federal guidelines for social distancing expired last week, though there’s no indication of consensus over when and to what extent policies should be relaxed around the nation. White House coronavirus coordinator Deborah Birx had said just the previous weekend that social distancing measures would “ be with us through the summer .” Though the current advice from the White House is that there should be a “ downward trajectory ” for 14 days before easing up, about half the nation’s governors have moved toward rollbacks of their interventions—while rates of infection and death in their states are often stable or increasing.

In an ideal world, science would show us how to avoid further chaos, or at least how to minimize it. But the total impact of social distancing measures, in terms of their benefits and harms to public health, remains uncertain. So what, exactly, should be done? I’m a meta-scientist, which means I do research on research; and my expertise is in evaluating evidence behind health claims. I believe it can be helpful to take a step back from these debates, from time to time, and consider what is actually known, unknown, and becoming-known on important questions. Let’s do just that for social distancing.

“Social distancing” is, in fact, an umbrella term that comprises several very complex interventions for keeping healthy people spaced apart from anyone who could be infectious. Measures range from telling people to avoid crowds to issuing wholesale stay-at-home orders, with just about endless variations and possible combinations. Each of these may work to differing degrees, and they come with varying social and economic costs. When we ask whether social distancing “works,” we’re collapsing all these boundaries.

In general, once it’s clear the spread of a new virus as dangerous as this one has not been contained by testing and contact tracing, and for which there isn’t any treatment or vaccine, more drastic forms of social distancing are the only options left to slow it down. But the body of knowledge about social distancing in all its forms is changing rapidly in real time, as the pandemic brings a blizzard of new data, research, and analysis. Say anything on some subjects, and there’s quite a good chance it could be out of date in hours, if not minutes.

Here’s what I think we know right now.

First, on the question of large gatherings, and the degree to which their prohibition slows viral spread. Covid-19 outbreaks appear to have spiraled out from large religious meetings both in South Korea and in France , each resulting in thousands of infections. A soccer match was at the epicenter of Italy’s devastating wave. When even one large event draws in people from far and wide, with SARS-CoV-2 circulating, the virus can break out of containment in a region. Indeed, shutting down such gatherings may have saved some parts of the US from the worst during the catastrophic 1918–1920 influenza pandemic. Cities deploying multiple distancing interventions a century ago had lower death rates , though few of them maintained these restrictions for longer than 6 weeks in 1918. Avoiding crowded living conditions , though, isn’t always feasible.

Got a coronavirus-related news tip? Send it to us at [email protected] .

What about travel restrictions? A systematic review of research on their deployment to prevent the spread of influenza looked at 20 studies conducted through May 2014. The link between travel and contagion appeared to be significant: When there was more travel, for example around Thanksgiving, more people got influenza; in contrast, when air travel decreased after 9/11, the rate of influenza decreased. Taken together, the studies suggest that domestic travel restrictions can delay influenza outbreaks for about a week; while international border closures may extend that window to 2 months.

Data from the Covid-19 pandemic might change the balance of evidence here. Restricting travel from Wuhan around Chinese Lunar New Year was seen as a success in helping to stop the spread of the coronavirus across China. A modeling study based on Wuhan data concluded that if international travel restrictions were combined with contact tracing and quarantine, it might be possible to keep the disease under control. Several countries may try to last the distance to a vaccine this way. Australia and New Zealand, for example, may allow cross-border travel only within their shared bubble of well-controlled infection rates; and perhaps to other countries in the region, too, if they become and stay Covid-19-free.

By Meghan Herbst

The question of school closures has been especially contentious, given the major social costs of the intervention. In New York City , where more than 173,000 people have now been diagnosed with Covid-19, and there have been more than 18,000 confirmed or probably associated deaths, local politicians resisted taking this step until mid-March . Do we know for sure that shutting schools can help? In fact, this is the element of social distancing that has been studied the most: A systematic review just undertaken for the World Health Organization analyzed 101 studies on the matter. In aggregate, these showed that closing schools may not do much to slow down an epidemic, while it can create a childcare crisis, among other added harms. This absence of clear benefit comes despite the fact that the studies in question looked at influenza outbreaks, where children are a major source of spread and can be affected significantly by illness. The role of children in the spread of Covid-19 is much less clear: They don’t appear to get as sick as adults do, though there are reports of their being contagious even without symptoms. On the other hand, influenza outbreaks don’t threaten health systems in the same way Covid-19 has.