How to Write a Conclusion for Research Papers (with Examples)

The conclusion of a research paper is a crucial section that plays a significant role in the overall impact and effectiveness of your research paper. However, this is also the section that typically receives less attention compared to the introduction and the body of the paper. The conclusion serves to provide a concise summary of the key findings, their significance, their implications, and a sense of closure to the study. Discussing how can the findings be applied in real-world scenarios or inform policy, practice, or decision-making is especially valuable to practitioners and policymakers. The research paper conclusion also provides researchers with clear insights and valuable information for their own work, which they can then build on and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

The research paper conclusion should explain the significance of your findings within the broader context of your field. It restates how your results contribute to the existing body of knowledge and whether they confirm or challenge existing theories or hypotheses. Also, by identifying unanswered questions or areas requiring further investigation, your awareness of the broader research landscape can be demonstrated.

Remember to tailor the research paper conclusion to the specific needs and interests of your intended audience, which may include researchers, practitioners, policymakers, or a combination of these.

Table of Contents

What is a conclusion in a research paper, summarizing conclusion, editorial conclusion, externalizing conclusion, importance of a good research paper conclusion, how to write a conclusion for your research paper, research paper conclusion examples.

- How to write a research paper conclusion with Paperpal?

Frequently Asked Questions

A conclusion in a research paper is the final section where you summarize and wrap up your research, presenting the key findings and insights derived from your study. The research paper conclusion is not the place to introduce new information or data that was not discussed in the main body of the paper. When working on how to conclude a research paper, remember to stick to summarizing and interpreting existing content. The research paper conclusion serves the following purposes: 1

- Warn readers of the possible consequences of not attending to the problem.

- Recommend specific course(s) of action.

- Restate key ideas to drive home the ultimate point of your research paper.

- Provide a “take-home” message that you want the readers to remember about your study.

Types of conclusions for research papers

In research papers, the conclusion provides closure to the reader. The type of research paper conclusion you choose depends on the nature of your study, your goals, and your target audience. I provide you with three common types of conclusions:

A summarizing conclusion is the most common type of conclusion in research papers. It involves summarizing the main points, reiterating the research question, and restating the significance of the findings. This common type of research paper conclusion is used across different disciplines.

An editorial conclusion is less common but can be used in research papers that are focused on proposing or advocating for a particular viewpoint or policy. It involves presenting a strong editorial or opinion based on the research findings and offering recommendations or calls to action.

An externalizing conclusion is a type of conclusion that extends the research beyond the scope of the paper by suggesting potential future research directions or discussing the broader implications of the findings. This type of conclusion is often used in more theoretical or exploratory research papers.

Align your conclusion’s tone with the rest of your research paper. Start Writing with Paperpal Now!

The conclusion in a research paper serves several important purposes:

- Offers Implications and Recommendations : Your research paper conclusion is an excellent place to discuss the broader implications of your research and suggest potential areas for further study. It’s also an opportunity to offer practical recommendations based on your findings.

- Provides Closure : A good research paper conclusion provides a sense of closure to your paper. It should leave the reader with a feeling that they have reached the end of a well-structured and thought-provoking research project.

- Leaves a Lasting Impression : Writing a well-crafted research paper conclusion leaves a lasting impression on your readers. It’s your final opportunity to leave them with a new idea, a call to action, or a memorable quote.

Writing a strong conclusion for your research paper is essential to leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here’s a step-by-step process to help you create and know what to put in the conclusion of a research paper: 2

- Research Statement : Begin your research paper conclusion by restating your research statement. This reminds the reader of the main point you’ve been trying to prove throughout your paper. Keep it concise and clear.

- Key Points : Summarize the main arguments and key points you’ve made in your paper. Avoid introducing new information in the research paper conclusion. Instead, provide a concise overview of what you’ve discussed in the body of your paper.

- Address the Research Questions : If your research paper is based on specific research questions or hypotheses, briefly address whether you’ve answered them or achieved your research goals. Discuss the significance of your findings in this context.

- Significance : Highlight the importance of your research and its relevance in the broader context. Explain why your findings matter and how they contribute to the existing knowledge in your field.

- Implications : Explore the practical or theoretical implications of your research. How might your findings impact future research, policy, or real-world applications? Consider the “so what?” question.

- Future Research : Offer suggestions for future research in your area. What questions or aspects remain unanswered or warrant further investigation? This shows that your work opens the door for future exploration.

- Closing Thought : Conclude your research paper conclusion with a thought-provoking or memorable statement. This can leave a lasting impression on your readers and wrap up your paper effectively. Avoid introducing new information or arguments here.

- Proofread and Revise : Carefully proofread your conclusion for grammar, spelling, and clarity. Ensure that your ideas flow smoothly and that your conclusion is coherent and well-structured.

Write your research paper conclusion 2x faster with Paperpal. Try it now!

Remember that a well-crafted research paper conclusion is a reflection of the strength of your research and your ability to communicate its significance effectively. It should leave a lasting impression on your readers and tie together all the threads of your paper. Now you know how to start the conclusion of a research paper and what elements to include to make it impactful, let’s look at a research paper conclusion sample.

How to write a research paper conclusion with Paperpal?

A research paper conclusion is not just a summary of your study, but a synthesis of the key findings that ties the research together and places it in a broader context. A research paper conclusion should be concise, typically around one paragraph in length. However, some complex topics may require a longer conclusion to ensure the reader is left with a clear understanding of the study’s significance. Paperpal, an AI writing assistant trusted by over 800,000 academics globally, can help you write a well-structured conclusion for your research paper.

- Sign Up or Log In: Create a new Paperpal account or login with your details.

- Navigate to Features : Once logged in, head over to the features’ side navigation pane. Click on Templates and you’ll find a suite of generative AI features to help you write better, faster.

- Generate an outline: Under Templates, select ‘Outlines’. Choose ‘Research article’ as your document type.

- Select your section: Since you’re focusing on the conclusion, select this section when prompted.

- Choose your field of study: Identifying your field of study allows Paperpal to provide more targeted suggestions, ensuring the relevance of your conclusion to your specific area of research.

- Provide a brief description of your study: Enter details about your research topic and findings. This information helps Paperpal generate a tailored outline that aligns with your paper’s content.

- Generate the conclusion outline: After entering all necessary details, click on ‘generate’. Paperpal will then create a structured outline for your conclusion, to help you start writing and build upon the outline.

- Write your conclusion: Use the generated outline to build your conclusion. The outline serves as a guide, ensuring you cover all critical aspects of a strong conclusion, from summarizing key findings to highlighting the research’s implications.

- Refine and enhance: Paperpal’s ‘Make Academic’ feature can be particularly useful in the final stages. Select any paragraph of your conclusion and use this feature to elevate the academic tone, ensuring your writing is aligned to the academic journal standards.

By following these steps, Paperpal not only simplifies the process of writing a research paper conclusion but also ensures it is impactful, concise, and aligned with academic standards. Sign up with Paperpal today and write your research paper conclusion 2x faster .

The research paper conclusion is a crucial part of your paper as it provides the final opportunity to leave a strong impression on your readers. In the research paper conclusion, summarize the main points of your research paper by restating your research statement, highlighting the most important findings, addressing the research questions or objectives, explaining the broader context of the study, discussing the significance of your findings, providing recommendations if applicable, and emphasizing the takeaway message. The main purpose of the conclusion is to remind the reader of the main point or argument of your paper and to provide a clear and concise summary of the key findings and their implications. All these elements should feature on your list of what to put in the conclusion of a research paper to create a strong final statement for your work.

A strong conclusion is a critical component of a research paper, as it provides an opportunity to wrap up your arguments, reiterate your main points, and leave a lasting impression on your readers. Here are the key elements of a strong research paper conclusion: 1. Conciseness : A research paper conclusion should be concise and to the point. It should not introduce new information or ideas that were not discussed in the body of the paper. 2. Summarization : The research paper conclusion should be comprehensive enough to give the reader a clear understanding of the research’s main contributions. 3 . Relevance : Ensure that the information included in the research paper conclusion is directly relevant to the research paper’s main topic and objectives; avoid unnecessary details. 4 . Connection to the Introduction : A well-structured research paper conclusion often revisits the key points made in the introduction and shows how the research has addressed the initial questions or objectives. 5. Emphasis : Highlight the significance and implications of your research. Why is your study important? What are the broader implications or applications of your findings? 6 . Call to Action : Include a call to action or a recommendation for future research or action based on your findings.

The length of a research paper conclusion can vary depending on several factors, including the overall length of the paper, the complexity of the research, and the specific journal requirements. While there is no strict rule for the length of a conclusion, but it’s generally advisable to keep it relatively short. A typical research paper conclusion might be around 5-10% of the paper’s total length. For example, if your paper is 10 pages long, the conclusion might be roughly half a page to one page in length.

In general, you do not need to include citations in the research paper conclusion. Citations are typically reserved for the body of the paper to support your arguments and provide evidence for your claims. However, there may be some exceptions to this rule: 1. If you are drawing a direct quote or paraphrasing a specific source in your research paper conclusion, you should include a citation to give proper credit to the original author. 2. If your conclusion refers to or discusses specific research, data, or sources that are crucial to the overall argument, citations can be included to reinforce your conclusion’s validity.

The conclusion of a research paper serves several important purposes: 1. Summarize the Key Points 2. Reinforce the Main Argument 3. Provide Closure 4. Offer Insights or Implications 5. Engage the Reader. 6. Reflect on Limitations

Remember that the primary purpose of the research paper conclusion is to leave a lasting impression on the reader, reinforcing the key points and providing closure to your research. It’s often the last part of the paper that the reader will see, so it should be strong and well-crafted.

- Makar, G., Foltz, C., Lendner, M., & Vaccaro, A. R. (2018). How to write effective discussion and conclusion sections. Clinical spine surgery, 31(8), 345-346.

- Bunton, D. (2005). The structure of PhD conclusion chapters. Journal of English for academic purposes , 4 (3), 207-224.

Paperpal is a comprehensive AI writing toolkit that helps students and researchers achieve 2x the writing in half the time. It leverages 21+ years of STM experience and insights from millions of research articles to provide in-depth academic writing, language editing, and submission readiness support to help you write better, faster.

Get accurate academic translations, rewriting support, grammar checks, vocabulary suggestions, and generative AI assistance that delivers human precision at machine speed. Try for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime starting at US$19 a month to access premium features, including consistency, plagiarism, and 30+ submission readiness checks to help you succeed.

Experience the future of academic writing – Sign up to Paperpal and start writing for free!

Related Reads:

- 5 Reasons for Rejection After Peer Review

- Ethical Research Practices For Research with Human Subjects

7 Ways to Improve Your Academic Writing Process

- Paraphrasing in Academic Writing: Answering Top Author Queries

Preflight For Editorial Desk: The Perfect Hybrid (AI + Human) Assistance Against Compromised Manuscripts

You may also like, what are journal guidelines on using generative ai..., quillbot review: features, pricing, and free alternatives, what is an academic paper types and elements , should you use ai tools like chatgpt for..., publish research papers: 9 steps for successful publications , what are the different types of research papers, how to make translating academic papers less challenging, self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how..., 6 tips for post-doc researchers to take their..., presenting research data effectively through tables and figures.

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and Examples

Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Paper Conclusion

Definition:

A research paper conclusion is the final section of a research paper that summarizes the key findings, significance, and implications of the research. It is the writer’s opportunity to synthesize the information presented in the paper, draw conclusions, and make recommendations for future research or actions.

The conclusion should provide a clear and concise summary of the research paper, reiterating the research question or problem, the main results, and the significance of the findings. It should also discuss the limitations of the study and suggest areas for further research.

Parts of Research Paper Conclusion

The parts of a research paper conclusion typically include:

Restatement of the Thesis

The conclusion should begin by restating the thesis statement from the introduction in a different way. This helps to remind the reader of the main argument or purpose of the research.

Summary of Key Findings

The conclusion should summarize the main findings of the research, highlighting the most important results and conclusions. This section should be brief and to the point.

Implications and Significance

In this section, the researcher should explain the implications and significance of the research findings. This may include discussing the potential impact on the field or industry, highlighting new insights or knowledge gained, or pointing out areas for future research.

Limitations and Recommendations

It is important to acknowledge any limitations or weaknesses of the research and to make recommendations for how these could be addressed in future studies. This shows that the researcher is aware of the potential limitations of their work and is committed to improving the quality of research in their field.

Concluding Statement

The conclusion should end with a strong concluding statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader. This could be a call to action, a recommendation for further research, or a final thought on the topic.

How to Write Research Paper Conclusion

Here are some steps you can follow to write an effective research paper conclusion:

- Restate the research problem or question: Begin by restating the research problem or question that you aimed to answer in your research. This will remind the reader of the purpose of your study.

- Summarize the main points: Summarize the key findings and results of your research. This can be done by highlighting the most important aspects of your research and the evidence that supports them.

- Discuss the implications: Discuss the implications of your findings for the research area and any potential applications of your research. You should also mention any limitations of your research that may affect the interpretation of your findings.

- Provide a conclusion : Provide a concise conclusion that summarizes the main points of your paper and emphasizes the significance of your research. This should be a strong and clear statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

- Offer suggestions for future research: Lastly, offer suggestions for future research that could build on your findings and contribute to further advancements in the field.

Remember that the conclusion should be brief and to the point, while still effectively summarizing the key findings and implications of your research.

Example of Research Paper Conclusion

Here’s an example of a research paper conclusion:

Conclusion :

In conclusion, our study aimed to investigate the relationship between social media use and mental health among college students. Our findings suggest that there is a significant association between social media use and increased levels of anxiety and depression among college students. This highlights the need for increased awareness and education about the potential negative effects of social media use on mental health, particularly among college students.

Despite the limitations of our study, such as the small sample size and self-reported data, our findings have important implications for future research and practice. Future studies should aim to replicate our findings in larger, more diverse samples, and investigate the potential mechanisms underlying the association between social media use and mental health. In addition, interventions should be developed to promote healthy social media use among college students, such as mindfulness-based approaches and social media detox programs.

Overall, our study contributes to the growing body of research on the impact of social media on mental health, and highlights the importance of addressing this issue in the context of higher education. By raising awareness and promoting healthy social media use among college students, we can help to reduce the negative impact of social media on mental health and improve the well-being of young adults.

Purpose of Research Paper Conclusion

The purpose of a research paper conclusion is to provide a summary and synthesis of the key findings, significance, and implications of the research presented in the paper. The conclusion serves as the final opportunity for the writer to convey their message and leave a lasting impression on the reader.

The conclusion should restate the research problem or question, summarize the main results of the research, and explain their significance. It should also acknowledge the limitations of the study and suggest areas for future research or action.

Overall, the purpose of the conclusion is to provide a sense of closure to the research paper and to emphasize the importance of the research and its potential impact. It should leave the reader with a clear understanding of the main findings and why they matter. The conclusion serves as the writer’s opportunity to showcase their contribution to the field and to inspire further research and action.

When to Write Research Paper Conclusion

The conclusion of a research paper should be written after the body of the paper has been completed. It should not be written until the writer has thoroughly analyzed and interpreted their findings and has written a complete and cohesive discussion of the research.

Before writing the conclusion, the writer should review their research paper and consider the key points that they want to convey to the reader. They should also review the research question, hypotheses, and methodology to ensure that they have addressed all of the necessary components of the research.

Once the writer has a clear understanding of the main findings and their significance, they can begin writing the conclusion. The conclusion should be written in a clear and concise manner, and should reiterate the main points of the research while also providing insights and recommendations for future research or action.

Characteristics of Research Paper Conclusion

The characteristics of a research paper conclusion include:

- Clear and concise: The conclusion should be written in a clear and concise manner, summarizing the key findings and their significance.

- Comprehensive: The conclusion should address all of the main points of the research paper, including the research question or problem, the methodology, the main results, and their implications.

- Future-oriented : The conclusion should provide insights and recommendations for future research or action, based on the findings of the research.

- Impressive : The conclusion should leave a lasting impression on the reader, emphasizing the importance of the research and its potential impact.

- Objective : The conclusion should be based on the evidence presented in the research paper, and should avoid personal biases or opinions.

- Unique : The conclusion should be unique to the research paper and should not simply repeat information from the introduction or body of the paper.

Advantages of Research Paper Conclusion

The advantages of a research paper conclusion include:

- Summarizing the key findings : The conclusion provides a summary of the main findings of the research, making it easier for the reader to understand the key points of the study.

- Emphasizing the significance of the research: The conclusion emphasizes the importance of the research and its potential impact, making it more likely that readers will take the research seriously and consider its implications.

- Providing recommendations for future research or action : The conclusion suggests practical recommendations for future research or action, based on the findings of the study.

- Providing closure to the research paper : The conclusion provides a sense of closure to the research paper, tying together the different sections of the paper and leaving a lasting impression on the reader.

- Demonstrating the writer’s contribution to the field : The conclusion provides the writer with an opportunity to showcase their contribution to the field and to inspire further research and action.

Limitations of Research Paper Conclusion

While the conclusion of a research paper has many advantages, it also has some limitations that should be considered, including:

- I nability to address all aspects of the research: Due to the limited space available in the conclusion, it may not be possible to address all aspects of the research in detail.

- Subjectivity : While the conclusion should be objective, it may be influenced by the writer’s personal biases or opinions.

- Lack of new information: The conclusion should not introduce new information that has not been discussed in the body of the research paper.

- Lack of generalizability: The conclusions drawn from the research may not be applicable to other contexts or populations, limiting the generalizability of the study.

- Misinterpretation by the reader: The reader may misinterpret the conclusions drawn from the research, leading to a misunderstanding of the findings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

The discussion section contains the results and outcomes of a study. An effective discussion informs readers what can be learned from your experiment and provides context for the results.

What makes an effective discussion?

When you’re ready to write your discussion, you’ve already introduced the purpose of your study and provided an in-depth description of the methodology. The discussion informs readers about the larger implications of your study based on the results. Highlighting these implications while not overstating the findings can be challenging, especially when you’re submitting to a journal that selects articles based on novelty or potential impact. Regardless of what journal you are submitting to, the discussion section always serves the same purpose: concluding what your study results actually mean.

A successful discussion section puts your findings in context. It should include:

- the results of your research,

- a discussion of related research, and

- a comparison between your results and initial hypothesis.

Tip: Not all journals share the same naming conventions.

You can apply the advice in this article to the conclusion, results or discussion sections of your manuscript.

Our Early Career Researcher community tells us that the conclusion is often considered the most difficult aspect of a manuscript to write. To help, this guide provides questions to ask yourself, a basic structure to model your discussion off of and examples from published manuscripts.

Questions to ask yourself:

- Was my hypothesis correct?

- If my hypothesis is partially correct or entirely different, what can be learned from the results?

- How do the conclusions reshape or add onto the existing knowledge in the field? What does previous research say about the topic?

- Why are the results important or relevant to your audience? Do they add further evidence to a scientific consensus or disprove prior studies?

- How can future research build on these observations? What are the key experiments that must be done?

- What is the “take-home” message you want your reader to leave with?

How to structure a discussion

Trying to fit a complete discussion into a single paragraph can add unnecessary stress to the writing process. If possible, you’ll want to give yourself two or three paragraphs to give the reader a comprehensive understanding of your study as a whole. Here’s one way to structure an effective discussion:

Writing Tips

While the above sections can help you brainstorm and structure your discussion, there are many common mistakes that writers revert to when having difficulties with their paper. Writing a discussion can be a delicate balance between summarizing your results, providing proper context for your research and avoiding introducing new information. Remember that your paper should be both confident and honest about the results!

- Read the journal’s guidelines on the discussion and conclusion sections. If possible, learn about the guidelines before writing the discussion to ensure you’re writing to meet their expectations.

- Begin with a clear statement of the principal findings. This will reinforce the main take-away for the reader and set up the rest of the discussion.

- Explain why the outcomes of your study are important to the reader. Discuss the implications of your findings realistically based on previous literature, highlighting both the strengths and limitations of the research.

- State whether the results prove or disprove your hypothesis. If your hypothesis was disproved, what might be the reasons?

- Introduce new or expanded ways to think about the research question. Indicate what next steps can be taken to further pursue any unresolved questions.

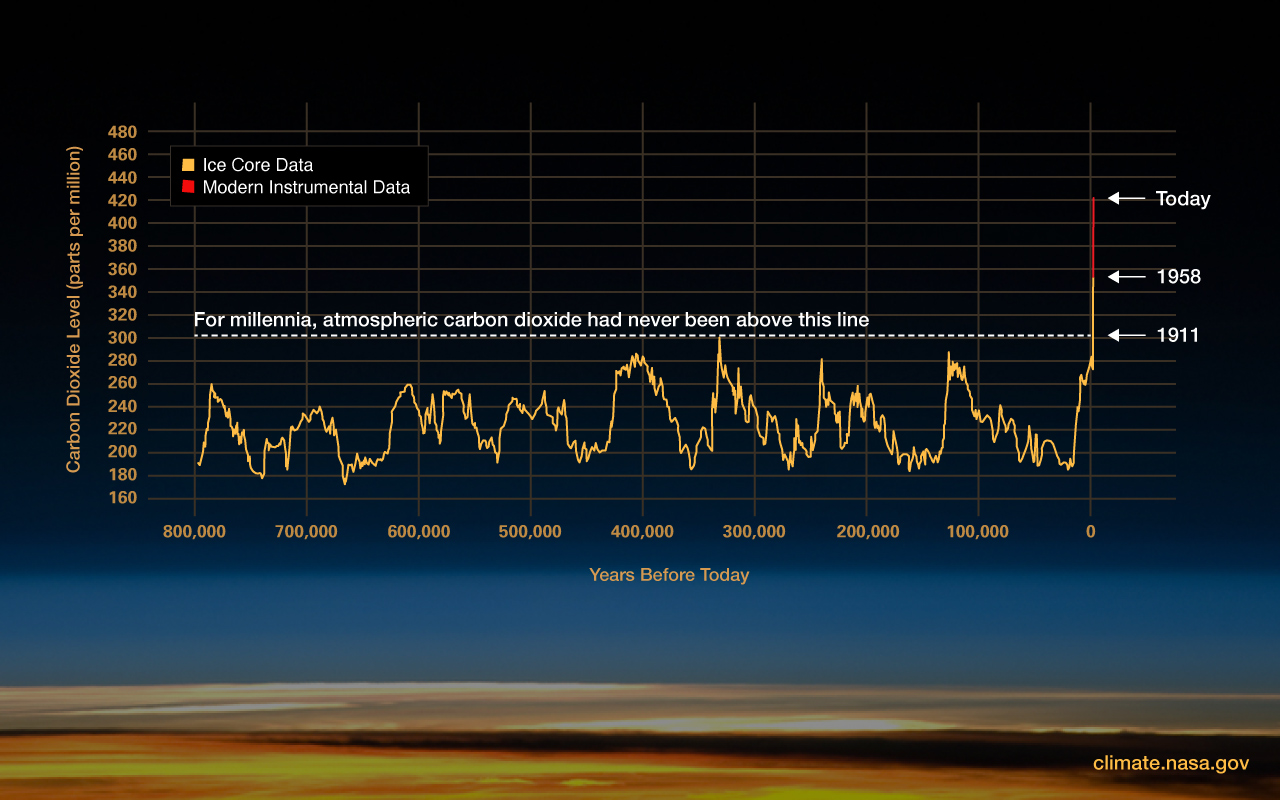

- If dealing with a contemporary or ongoing problem, such as climate change, discuss possible consequences if the problem is avoided.

- Be concise. Adding unnecessary detail can distract from the main findings.

Don’t

- Rewrite your abstract. Statements with “we investigated” or “we studied” generally do not belong in the discussion.

- Include new arguments or evidence not previously discussed. Necessary information and evidence should be introduced in the main body of the paper.

- Apologize. Even if your research contains significant limitations, don’t undermine your authority by including statements that doubt your methodology or execution.

- Shy away from speaking on limitations or negative results. Including limitations and negative results will give readers a complete understanding of the presented research. Potential limitations include sources of potential bias, threats to internal or external validity, barriers to implementing an intervention and other issues inherent to the study design.

- Overstate the importance of your findings. Making grand statements about how a study will fully resolve large questions can lead readers to doubt the success of the research.

Snippets of Effective Discussions:

Consumer-based actions to reduce plastic pollution in rivers: A multi-criteria decision analysis approach

Identifying reliable indicators of fitness in polar bears

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

Join thousands of product people at Insight Out Conf on April 11. Register free.

Insights hub solutions

Analyze data

Uncover deep customer insights with fast, powerful features, store insights, curate and manage insights in one searchable platform, scale research, unlock the potential of customer insights at enterprise scale.

Featured reads

Inspiration

Three things to look forward to at Insight Out

Tips and tricks

Make magic with your customer data in Dovetail

Four ways Dovetail helps Product Managers master continuous product discovery

Events and videos

© Dovetail Research Pty. Ltd.

How to write a strong conclusion for your research paper

Last updated

17 February 2024

Reviewed by

Writing a research paper is a chance to share your knowledge and hypothesis. It's an opportunity to demonstrate your many hours of research and prove your ability to write convincingly.

Ideally, by the end of your research paper, you'll have brought your readers on a journey to reach the conclusions you've pre-determined. However, if you don't stick the landing with a good conclusion, you'll risk losing your reader’s trust.

Writing a strong conclusion for your research paper involves a few important steps, including restating the thesis and summing up everything properly.

Find out what to include and what to avoid, so you can effectively demonstrate your understanding of the topic and prove your expertise.

- Why is a good conclusion important?

A good conclusion can cement your paper in the reader’s mind. Making a strong impression in your introduction can draw your readers in, but it's the conclusion that will inspire them.

- What to include in a research paper conclusion

There are a few specifics you should include in your research paper conclusion. Offer your readers some sense of urgency or consequence by pointing out why they should care about the topic you have covered. Discuss any common problems associated with your topic and provide suggestions as to how these problems can be solved or addressed.

The conclusion should include a restatement of your initial thesis. Thesis statements are strengthened after you’ve presented supporting evidence (as you will have done in the paper), so make a point to reintroduce it at the end.

Finally, recap the main points of your research paper, highlighting the key takeaways you want readers to remember. If you've made multiple points throughout the paper, refer to the ones with the strongest supporting evidence.

- Steps for writing a research paper conclusion

Many writers find the conclusion the most challenging part of any research project . By following these three steps, you'll be prepared to write a conclusion that is effective and concise.

- Step 1: Restate the problem

Always begin by restating the research problem in the conclusion of a research paper. This serves to remind the reader of your hypothesis and refresh them on the main point of the paper.

When restating the problem, take care to avoid using exactly the same words you employed earlier in the paper.

- Step 2: Sum up the paper

After you've restated the problem, sum up the paper by revealing your overall findings. The method for this differs slightly, depending on whether you're crafting an argumentative paper or an empirical paper.

Argumentative paper: Restate your thesis and arguments

Argumentative papers involve introducing a thesis statement early on. In crafting the conclusion for an argumentative paper, always restate the thesis, outlining the way you've developed it throughout the entire paper.

It might be appropriate to mention any counterarguments in the conclusion, so you can demonstrate how your thesis is correct or how the data best supports your main points.

Empirical paper: Summarize research findings

Empirical papers break down a series of research questions. In your conclusion, discuss the findings your research revealed, including any information that surprised you.

Be clear about the conclusions you reached, and explain whether or not you expected to arrive at these particular ones.

- Step 3: Discuss the implications of your research

Argumentative papers and empirical papers also differ in this part of a research paper conclusion. Here are some tips on crafting conclusions for argumentative and empirical papers.

Argumentative paper: Powerful closing statement

In an argumentative paper, you'll have spent a great deal of time expressing the opinions you formed after doing a significant amount of research. Make a strong closing statement in your argumentative paper's conclusion to share the significance of your work.

You can outline the next steps through a bold call to action, or restate how powerful your ideas turned out to be.

Empirical paper: Directions for future research

Empirical papers are broader in scope. They usually cover a variety of aspects and can include several points of view.

To write a good conclusion for an empirical paper, suggest the type of research that could be done in the future, including methods for further investigation or outlining ways other researchers might proceed.

If you feel your research had any limitations, even if they were outside your control, you could mention these in your conclusion.

After you finish outlining your conclusion, ask someone to read it and offer feedback. In any research project you're especially close to, it can be hard to identify problem areas. Having a close friend or someone whose opinion you value read the research paper and provide honest feedback can be invaluable. Take note of any suggested edits and consider incorporating them into your paper if they make sense.

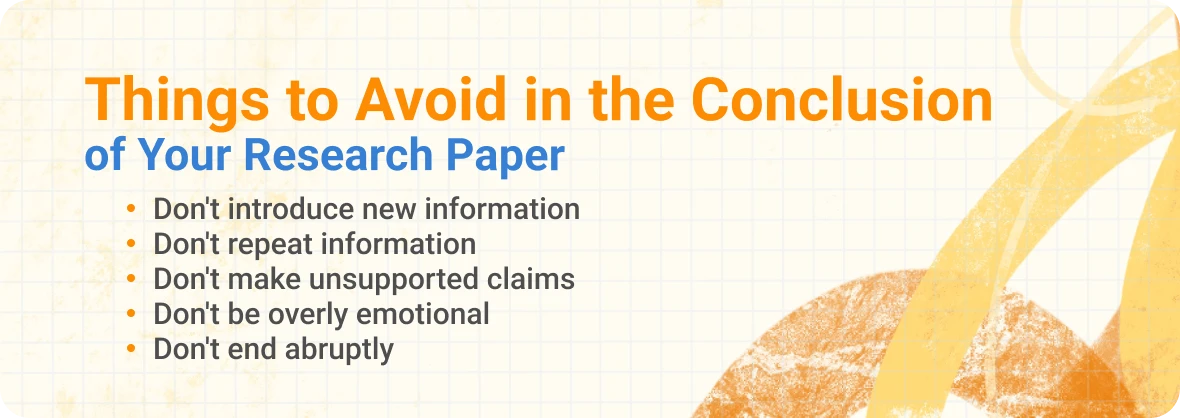

- Things to avoid in a research paper conclusion

Keep these aspects to avoid in mind as you're writing your conclusion and refer to them after you've created an outline.

Dry summary

Writing a memorable, succinct conclusion is arguably more important than a strong introduction. Take care to avoid just rephrasing your main points, and don't fall into the trap of repeating dry facts or citations.

You can provide a new perspective for your readers to think about or contextualize your research. Either way, make the conclusion vibrant and interesting, rather than a rote recitation of your research paper’s highlights.

Clichéd or generic phrasing

Your research paper conclusion should feel fresh and inspiring. Avoid generic phrases like "to sum up" or "in conclusion." These phrases tend to be overused, especially in an academic context and might turn your readers off.

The conclusion also isn't the time to introduce colloquial phrases or informal language. Retain a professional, confident tone consistent throughout your paper’s conclusion so it feels exciting and bold.

New data or evidence

While you should present strong data throughout your paper, the conclusion isn't the place to introduce new evidence. This is because readers are engaged in actively learning as they read through the body of your paper.

By the time they reach the conclusion, they will have formed an opinion one way or the other (hopefully in your favor!). Introducing new evidence in the conclusion will only serve to surprise or frustrate your reader.

Ignoring contradictory evidence

If your research reveals contradictory evidence, don't ignore it in the conclusion. This will damage your credibility as an expert and might even serve to highlight the contradictions.

Be as transparent as possible and admit to any shortcomings in your research, but don't dwell on them for too long.

Ambiguous or unclear resolutions

The point of a research paper conclusion is to provide closure and bring all your ideas together. You should wrap up any arguments you introduced in the paper and tie up any loose ends, while demonstrating why your research and data are strong.

Use direct language in your conclusion and avoid ambiguity. Even if some of the data and sources you cite are inconclusive or contradictory, note this in your conclusion to come across as confident and trustworthy.

- Examples of research paper conclusions

Your research paper should provide a compelling close to the paper as a whole, highlighting your research and hard work. While the conclusion should represent your unique style, these examples offer a starting point:

Ultimately, the data we examined all point to the same conclusion: Encouraging a good work-life balance improves employee productivity and benefits the company overall. The research suggests that when employees feel their personal lives are valued and respected by their employers, they are more likely to be productive when at work. In addition, company turnover tends to be reduced when employees have a balance between their personal and professional lives. While additional research is required to establish ways companies can support employees in creating a stronger work-life balance, it's clear the need is there.

Social media is a primary method of communication among young people. As we've seen in the data presented, most young people in high school use a variety of social media applications at least every hour, including Instagram and Facebook. While social media is an avenue for connection with peers, research increasingly suggests that social media use correlates with body image issues. Young girls with lower self-esteem tend to use social media more often than those who don't log onto social media apps every day. As new applications continue to gain popularity, and as more high school students are given smartphones, more research will be required to measure the effects of prolonged social media use.

What are the different kinds of research paper conclusions?

There are no formal types of research paper conclusions. Ultimately, the conclusion depends on the outline of your paper and the type of research you’re presenting. While some experts note that research papers can end with a new perspective or commentary, most papers should conclude with a combination of both. The most important aspect of a good research paper conclusion is that it accurately represents the body of the paper.

Can I present new arguments in my research paper conclusion?

Research paper conclusions are not the place to introduce new data or arguments. The body of your paper is where you should share research and insights, where the reader is actively absorbing the content. By the time a reader reaches the conclusion of the research paper, they should have formed their opinion. Introducing new arguments in the conclusion can take a reader by surprise, and not in a positive way. It might also serve to frustrate readers.

How long should a research paper conclusion be?

There's no set length for a research paper conclusion. However, it's a good idea not to run on too long, since conclusions are supposed to be succinct. A good rule of thumb is to keep your conclusion around 5 to 10 percent of the paper's total length. If your paper is 10 pages, try to keep your conclusion under one page.

What should I include in a research paper conclusion?

A good research paper conclusion should always include a sense of urgency, so the reader can see how and why the topic should matter to them. You can also note some recommended actions to help fix the problem and some obstacles they might encounter. A conclusion should also remind the reader of the thesis statement, along with the main points you covered in the paper. At the end of the conclusion, add a powerful closing statement that helps cement the paper in the mind of the reader.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 17 February 2024

Last updated: 19 November 2023

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

In a short paper—even a research paper—you don’t need to provide an exhaustive summary as part of your conclusion. But you do need to make some kind of transition between your final body paragraph and your concluding paragraph. This may come in the form of a few sentences of summary. Or it may come in the form of a sentence that brings your readers back to your thesis or main idea and reminds your readers where you began and how far you have traveled.

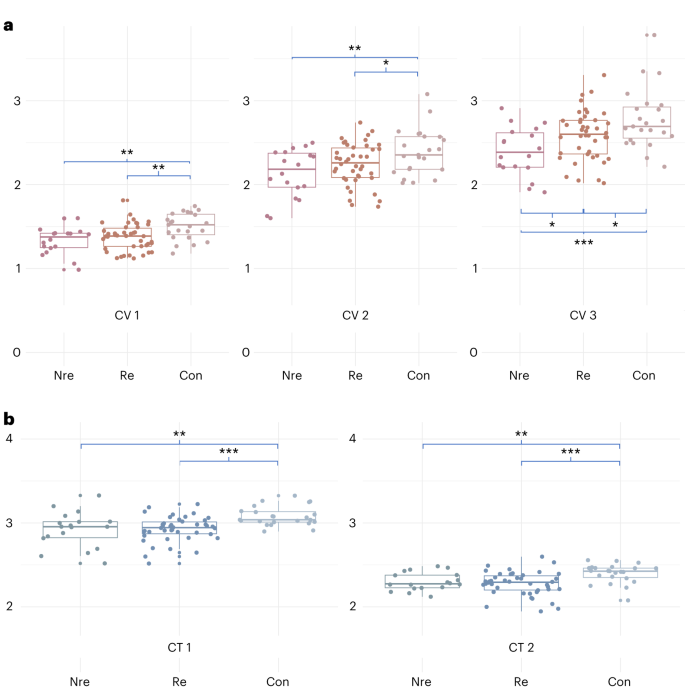

So, for example, in a paper about the relationship between ADHD and rejection sensitivity, Vanessa Roser begins by introducing readers to the fact that researchers have studied the relationship between the two conditions and then provides her explanation of that relationship. Here’s her thesis: “While socialization may indeed be an important factor in RS, I argue that individuals with ADHD may also possess a neurological predisposition to RS that is exacerbated by the differing executive and emotional regulation characteristic of ADHD.”

In her final paragraph, Roser reminds us of where she started by echoing her thesis: “This literature demonstrates that, as with many other conditions, ADHD and RS share a delicately intertwined pattern of neurological similarities that is rooted in the innate biology of an individual’s mind, a connection that cannot be explained in full by the behavioral mediation hypothesis.”

Highlight the “so what”

At the beginning of your paper, you explain to your readers what’s at stake—why they should care about the argument you’re making. In your conclusion, you can bring readers back to those stakes by reminding them why your argument is important in the first place. You can also draft a few sentences that put those stakes into a new or broader context.

In the conclusion to her paper about ADHD and RS, Roser echoes the stakes she established in her introduction—that research into connections between ADHD and RS has led to contradictory results, raising questions about the “behavioral mediation hypothesis.”

She writes, “as with many other conditions, ADHD and RS share a delicately intertwined pattern of neurological similarities that is rooted in the innate biology of an individual’s mind, a connection that cannot be explained in full by the behavioral mediation hypothesis.”

Leave your readers with the “now what”

After the “what” and the “so what,” you should leave your reader with some final thoughts. If you have written a strong introduction, your readers will know why you have been arguing what you have been arguing—and why they should care. And if you’ve made a good case for your thesis, then your readers should be in a position to see things in a new way, understand new questions, or be ready for something that they weren’t ready for before they read your paper.

In her conclusion, Roser offers two “now what” statements. First, she explains that it is important to recognize that the flawed behavioral mediation hypothesis “seems to place a degree of fault on the individual. It implies that individuals with ADHD must have elicited such frequent or intense rejection by virtue of their inadequate social skills, erasing the possibility that they may simply possess a natural sensitivity to emotion.” She then highlights the broader implications for treatment of people with ADHD, noting that recognizing the actual connection between rejection sensitivity and ADHD “has profound implications for understanding how individuals with ADHD might best be treated in educational settings, by counselors, family, peers, or even society as a whole.”

To find your own “now what” for your essay’s conclusion, try asking yourself these questions:

- What can my readers now understand, see in a new light, or grapple with that they would not have understood in the same way before reading my paper? Are we a step closer to understanding a larger phenomenon or to understanding why what was at stake is so important?

- What questions can I now raise that would not have made sense at the beginning of my paper? Questions for further research? Other ways that this topic could be approached?

- Are there other applications for my research? Could my questions be asked about different data in a different context? Could I use my methods to answer a different question?

- What action should be taken in light of this argument? What action do I predict will be taken or could lead to a solution?

- What larger context might my argument be a part of?

What to avoid in your conclusion

- a complete restatement of all that you have said in your paper.

- a substantial counterargument that you do not have space to refute; you should introduce counterarguments before your conclusion.

- an apology for what you have not said. If you need to explain the scope of your paper, you should do this sooner—but don’t apologize for what you have not discussed in your paper.

- fake transitions like “in conclusion” that are followed by sentences that aren’t actually conclusions. (“In conclusion, I have now demonstrated that my thesis is correct.”)

- picture_as_pdf Conclusions

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 9. The Conclusion

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The conclusion is intended to help the reader understand why your research should matter to them after they have finished reading the paper. A conclusion is not merely a summary of the main topics covered or a re-statement of your research problem, but a synthesis of key points and, if applicable, where you recommend new areas for future research. For most college-level research papers, one or two well-developed paragraphs is sufficient for a conclusion, although in some cases, more paragraphs may be required in summarizing key findings and their significance.

Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Conclusions. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

Importance of a Good Conclusion

A well-written conclusion provides you with important opportunities to demonstrate to the reader your understanding of the research problem. These include:

- Presenting the last word on the issues you raised in your paper . Just as the introduction gives a first impression to your reader, the conclusion offers a chance to leave a lasting impression. Do this, for example, by highlighting key findings in your analysis that advance new understanding about the research problem, that are unusual or unexpected, or that have important implications applied to practice.

- Summarizing your thoughts and conveying the larger significance of your study . The conclusion is an opportunity to succinctly re-emphasize the "So What?" question by placing the study within the context of how your research advances past research about the topic.

- Identifying how a gap in the literature has been addressed . The conclusion can be where you describe how a previously identified gap in the literature [described in your literature review section] has been filled by your research.

- Demonstrating the importance of your ideas . Don't be shy. The conclusion offers you the opportunity to elaborate on the impact and significance of your findings. This is particularly important if your study approached examining the research problem from an unusual or innovative perspective.

- Introducing possible new or expanded ways of thinking about the research problem . This does not refer to introducing new information [which should be avoided], but to offer new insight and creative approaches for framing or contextualizing the research problem based on the results of your study.

Bunton, David. “The Structure of PhD Conclusion Chapters.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 4 (July 2005): 207–224; Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Conclusion. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; Conclusions. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8.

Structure and Writing Style

I. General Rules

The function of your paper's conclusion is to restate the main argument . It reminds the reader of the strengths of your main argument(s) and reiterates the most important evidence supporting those argument(s). Do this by stating clearly the context, background, and necessity of pursuing the research problem you investigated in relation to an issue, controversy, or a gap found in the literature. Make sure, however, that your conclusion is not simply a repetitive summary of the findings. This reduces the impact of the argument(s) you have developed in your essay.

When writing the conclusion to your paper, follow these general rules:

- Present your conclusions in clear, simple language. Re-state the purpose of your study, then describe how your findings differ or support those of other studies and why [i.e., what were the unique or new contributions your study made to the overall research about your topic?].

- Do not simply reiterate your findings or the discussion of your results. Provide a synthesis of arguments presented in the paper to show how these converge to address the research problem and the overall objectives of your study.

- Indicate opportunities for future research if you haven't already done so in the discussion section of your paper. Highlighting the need for further research provides the reader with evidence that you have an in-depth awareness of the research problem and that further investigations should take place.

Consider the following points to help ensure your conclusion is presented well:

- If the argument or purpose of your paper is complex, you may need to summarize the argument for your reader.

- If, prior to your conclusion, you have not yet explained the significance of your findings or if you are proceeding inductively, use the end of your paper to describe your main points and explain their significance.

- Move from a detailed to a general level of consideration that returns the topic to the context provided by the introduction or within a new context that emerges from the data.

The conclusion also provides a place for you to persuasively and succinctly restate the research problem, given that the reader has now been presented with all the information about the topic . Depending on the discipline you are writing in, the concluding paragraph may contain your reflections on the evidence presented. However, the nature of being introspective about the research you have conducted will depend on the topic and whether your professor wants you to express your observations in this way.

NOTE : If asked to think introspectively about the topics, do not delve into idle speculation. Being introspective means looking within yourself as an author to try and understand an issue more deeply, not to guess at possible outcomes or make up scenarios not supported by the evidence.

II. Developing a Compelling Conclusion

Although an effective conclusion needs to be clear and succinct, it does not need to be written passively or lack a compelling narrative. Strategies to help you move beyond merely summarizing the key points of your research paper may include any of the following strategies:

- If your essay deals with a critical, contemporary problem, warn readers of the possible consequences of not attending to the problem proactively.

- Recommend a specific course or courses of action that, if adopted, could address a specific problem in practice or in the development of new knowledge.

- Cite a relevant quotation or expert opinion already noted in your paper in order to lend authority and support to the conclusion(s) you have reached [a good place to look is research from your literature review].

- Explain the consequences of your research in a way that elicits action or demonstrates urgency in seeking change.

- Restate a key statistic, fact, or visual image to emphasize the most important finding of your paper.

- If your discipline encourages personal reflection, illustrate your concluding point by drawing from your own life experiences.

- Return to an anecdote, an example, or a quotation that you presented in your introduction, but add further insight derived from the findings of your study; use your interpretation of results to recast it in new or important ways.

- Provide a "take-home" message in the form of a succinct, declarative statement that you want the reader to remember about your study.

III. Problems to Avoid

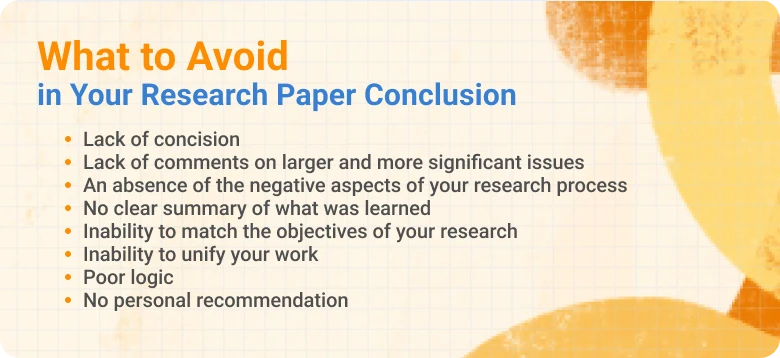

Failure to be concise Your conclusion section should be concise and to the point. Conclusions that are too lengthy often have unnecessary information in them. The conclusion is not the place for details about your methodology or results. Although you should give a summary of what was learned from your research, this summary should be relatively brief, since the emphasis in the conclusion is on the implications, evaluations, insights, and other forms of analysis that you make. Strategies for writing concisely can be found here .

Failure to comment on larger, more significant issues In the introduction, your task was to move from the general [the field of study] to the specific [the research problem]. However, in the conclusion, your task is to move from a specific discussion [your research problem] back to a general discussion [i.e., how your research contributes new understanding or fills an important gap in the literature]. In short, the conclusion is where you should place your research within a larger context [visualize your paper as an hourglass--start with a broad introduction and review of the literature, move to the specific analysis and discussion, conclude with a broad summary of the study's implications and significance].

Failure to reveal problems and negative results Negative aspects of the research process should never be ignored. These are problems, deficiencies, or challenges encountered during your study should be summarized as a way of qualifying your overall conclusions. If you encountered negative or unintended results [i.e., findings that are validated outside the research context in which they were generated], you must report them in the results section and discuss their implications in the discussion section of your paper. In the conclusion, use your summary of the negative results as an opportunity to explain their possible significance and/or how they may form the basis for future research.

Failure to provide a clear summary of what was learned In order to be able to discuss how your research fits within your field of study [and possibly the world at large], you need to summarize briefly and succinctly how it contributes to new knowledge or a new understanding about the research problem. This element of your conclusion may be only a few sentences long.

Failure to match the objectives of your research Often research objectives in the social sciences change while the research is being carried out. This is not a problem unless you forget to go back and refine the original objectives in your introduction. As these changes emerge they must be documented so that they accurately reflect what you were trying to accomplish in your research [not what you thought you might accomplish when you began].

Resist the urge to apologize If you've immersed yourself in studying the research problem, you presumably should know a good deal about it [perhaps even more than your professor!]. Nevertheless, by the time you have finished writing, you may be having some doubts about what you have produced. Repress those doubts! Don't undermine your authority by saying something like, "This is just one approach to examining this problem; there may be other, much better approaches that...." The overall tone of your conclusion should convey confidence to the reader.

Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8; Concluding Paragraphs. College Writing Center at Meramec. St. Louis Community College; Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Conclusions. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Freedman, Leora and Jerry Plotnick. Introductions and Conclusions. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Leibensperger, Summer. Draft Your Conclusion. Academic Center, the University of Houston-Victoria, 2003; Make Your Last Words Count. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin Madison; Miquel, Fuster-Marquez and Carmen Gregori-Signes. “Chapter Six: ‘Last but Not Least:’ Writing the Conclusion of Your Paper.” In Writing an Applied Linguistics Thesis or Dissertation: A Guide to Presenting Empirical Research . John Bitchener, editor. (Basingstoke,UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), pp. 93-105; Tips for Writing a Good Conclusion. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Conclusion. San Francisco Edit, 2003-2008; Writing Conclusions. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Writing: Considering Structure and Organization. Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College.

Writing Tip

Don't Belabor the Obvious!

Avoid phrases like "in conclusion...," "in summary...," or "in closing...." These phrases can be useful, even welcome, in oral presentations. But readers can see by the tell-tale section heading and number of pages remaining to read, when an essay is about to end. You'll irritate your readers if you belabor the obvious.

Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8.

Another Writing Tip

New Insight, Not New Information!

Don't surprise the reader with new information in your conclusion that was never referenced anywhere else in the paper and, as such, the conclusion rarely has citations to sources. If you have new information to present, add it to the discussion or other appropriate section of the paper. Note that, although no actual new information is introduced, the conclusion, along with the discussion section, is where you offer your most "original" contributions in the paper; the conclusion is where you describe the value of your research, demonstrate that you understand the material that you’ve presented, and locate your findings within the larger context of scholarship on the topic, including describing how your research contributes new insights or valuable insight to that scholarship.

Assan, Joseph. "Writing the Conclusion Chapter: The Good, the Bad and the Missing." Liverpool: Development Studies Association (2009): 1-8; Conclusions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina.

- << Previous: Limitations of the Study

- Next: Appendices >>

- Last Updated: Mar 26, 2024 10:40 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

- Research Papers

How to Write a Conclusion for a Research Paper

Last Updated: June 29, 2023 Approved

This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD . Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014. wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. This article received 42 testimonials and 82% of readers who voted found it helpful, earning it our reader-approved status. This article has been viewed 2,256,049 times.

The conclusion of a research paper needs to summarize the content and purpose of the paper without seeming too wooden or dry. Every basic conclusion must share several key elements, but there are also several tactics you can play around with to craft a more effective conclusion and several you should avoid to prevent yourself from weakening your paper's conclusion. Here are some writing tips to keep in mind when creating a conclusion for your next research paper.

Sample Conclusions

Writing a basic conclusion.

- Do not spend a great amount of time or space restating your topic.

- A good research paper will make the importance of your topic apparent, so you do not need to write an elaborate defense of your topic in the conclusion.

- Usually a single sentence is all you need to restate your topic.

- An example would be if you were writing a paper on the epidemiology of infectious disease, you might say something like "Tuberculosis is a widespread infectious disease that affects millions of people worldwide every year."

- Yet another example from the humanities would be a paper about the Italian Renaissance: "The Italian Renaissance was an explosion of art and ideas centered around artists, writers, and thinkers in Florence."

- A thesis is a narrowed, focused view on the topic at hand.

- This statement should be rephrased from the thesis you included in your introduction. It should not be identical or too similar to the sentence you originally used.

- Try re-wording your thesis statement in a way that complements your summary of the topic of your paper in your first sentence of your conclusion.

- An example of a good thesis statement, going back to the paper on tuberculosis, would be "Tuberculosis is a widespread disease that affects millions of people worldwide every year. Due to the alarming rate of the spread of tuberculosis, particularly in poor countries, medical professionals are implementing new strategies for the diagnosis, treatment, and containment of this disease ."

- A good way to go about this is to re-read the topic sentence of each major paragraph or section in the body of your paper.

- Find a way to briefly restate each point mentioned in each topic sentence in your conclusion. Do not repeat any of the supporting details used within your body paragraphs.

- Under most circumstances, you should avoid writing new information in your conclusion. This is especially true if the information is vital to the argument or research presented in your paper.

- For example, in the TB paper you could summarize the information. "Tuberculosis is a widespread disease that affects millions of people worldwide. Due to the alarming rate of the spread of tuberculosis, particularly in poor countries, medical professionals are implementing new strategies for the diagnosis, treatment, and containment of this disease. In developing countries, such as those in Africa and Southeast Asia, the rate of TB infections is soaring. Crowded conditions, poor sanitation, and lack of access to medical care are all compounding factors in the spread of the disease. Medical experts, such as those from the World Health Organization are now starting campaigns to go into communities in developing countries and provide diagnostic testing and treatments. However, the treatments for TB are very harsh and have many side effects. This leads to patient non-compliance and spread of multi-drug resistant strains of the disease."

- Note that this is not needed for all research papers.

- If you already fully explained what the points in your paper mean or why they are significant, you do not need to go into them in much detail in your conclusion. Simply restating your thesis or the significance of your topic should suffice.

- It is always best practice to address important issues and fully explain your points in the body of your paper. The point of a conclusion to a research paper is to summarize your argument for the reader and, perhaps, to call the reader to action if needed.

- Note that a call for action is not essential to all conclusions. A research paper on literary criticism, for instance, is less likely to need a call for action than a paper on the effect that television has on toddlers and young children.

- A paper that is more likely to call readers to action is one that addresses a public or scientific need. Let's go back to our example of tuberculosis. This is a very serious disease that is spreading quickly and with antibiotic-resistant forms.

- A call to action in this research paper would be a follow-up statement that might be along the lines of "Despite new efforts to diagnose and contain the disease, more research is needed to develop new antibiotics that will treat the most resistant strains of tuberculosis and ease the side effects of current treatments."

- For example, if you are writing a history paper, then you might discuss how the historical topic you discussed matters today. If you are writing about a foreign country, then you might use the conclusion to discuss how the information you shared may help readers understand their own country.

Making Your Conclusion as Effective as Possible

- Since this sort of conclusion is so basic, you must aim to synthesize the information rather than merely summarizing it.

- Instead of merely repeating things you already said, rephrase your thesis and supporting points in a way that ties them all together.

- By doing so, you make your research paper seem like a "complete thought" rather than a collection of random and vaguely related ideas.

- Ask a question in your introduction. In your conclusion, restate the question and provide a direct answer.

- Write an anecdote or story in your introduction but do not share the ending. Instead, write the conclusion to the anecdote in the conclusion of your paper.

- For example, if you wanted to get more creative and put a more humanistic spin on a paper on tuberculosis, you might start your introduction with a story about a person with the disease, and refer to that story in your conclusion. For example, you could say something like this before you re-state your thesis in your conclusion: "Patient X was unable to complete the treatment for tuberculosis due to severe side effects and unfortunately succumbed to the disease."

- Use the same concepts and images introduced in your introduction in your conclusion. The images may or may not appear at other points throughout the research paper.

- Include enough information about your topic to back the statement up but do not get too carried away with excess detail.

- If your research did not provide you with a clear-cut answer to a question posed in your thesis, do not be afraid to indicate as much.

- Restate your initial hypothesis and indicate whether you still believe it or if the research you performed has begun swaying your opinion.

- Indicate that an answer may still exist and that further research could shed more light on the topic at hand.

- This may not be appropriate for all types of research papers. Most research papers, such as one on effective treatment for diseases, will have the information to make the case for a particular argument already in the paper.

- A good example of a paper that might ask a question of the reader in the ending is one about a social issue, such as poverty or government policy.

- Ask a question that will directly get at the heart or purpose of the paper. This question is often the same question, or some version of it, that you may have started with when you began your research.

- Make sure that the question can be answered by the evidence presented in your paper.

- If desired you can briefly summarize the answer after stating the question. You could also leave the question hanging for the reader to answer, though.

- Even without a call to action, you can still make a recommendation to your reader.

- For instance, if you are writing about a topic like third-world poverty, you can various ways for the reader to assist in the problem without necessarily calling for more research.

- Another example would be, in a paper about treatment for drug-resistant tuberculosis, you could suggest donating to the World Health Organization or research foundations that are developing new treatments for the disease.

Avoiding Common Pitfalls

- These sayings usually sound stiff, unnatural, or trite when used in writing.

- Moreover, using a phrase like "in conclusion" to begin your conclusion is a little too straightforward and tends to lead to a weak conclusion. A strong conclusion can stand on its own without being labeled as such.

- Always state the main argument or thesis in the introduction. A research paper is an analytical discussion of an academic topic, not a mystery novel.

- A good, effective research paper will allow your reader to follow your main argument from start to finish.

- This is why it is best practice to start your paper with an introduction that states your main argument and to end the paper with a conclusion that re-states your thesis for re-iteration.

- All significant information should be introduced in the body of the paper.

- Supporting evidence expands the topic of your paper by making it appear more detailed. A conclusion should narrow the topic to a more general point.

- A conclusion should only summarize what you have already stated in the body of your paper.

- You may suggest further research or a call to action, but you should not bring in any new evidence or facts in the conclusion.

- Most often, a shift in tone occurs when a research paper with an academic tone gives an emotional or sentimental conclusion.

- Even if the topic of the paper is of personal significance for you, you should not indicate as much in your paper.

- If you want to give your paper a more humanistic slant, you could start and end your paper with a story or anecdote that would give your topic more personal meaning to the reader.

- This tone should be consistent throughout the paper, however.

- Apologetic statements include phrases like "I may not be an expert" or "This is only my opinion."

- Statements like this can usually be avoided by refraining from writing in the first-person.

- Avoid any statements in the first-person. First-person is generally considered to be informal and does not fit with the formal tone of a research paper.

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://owl.english.purdue.edu/owl/resource/724/04/

- ↑ http://www.crlsresearchguide.org/18_Writing_Conclusion.asp

- ↑ http://writing.wisc.edu/Handbook/PlanResearchPaper.html#conclusion

- ↑ http://writingcenter.unc.edu/handouts/conclusions/

- ↑ http://writing2.richmond.edu/writing/wweb/conclude.html

About This Article