- Journal of College Student Development

Identity Development Theories in Student Affairs: Origins, Current Status, and New Approaches

- Vasti Torres , Susan R. Jones , Kristen A. Renn

- Johns Hopkins University Press

- Volume 50, Number 6, November/December 2009

- pp. 577-596

- 10.1353/csd.0.0102

- View Citation

Additional Information

Project MUSE Mission

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Professional identity development: a review of the higher education

This study examined the extant higher education literature on the development of professional identities (PID). Through a systematic review approach 20 articles were identified that discussed in some way professional identity development in higher education journals. These papers drew on varied theories, pedagogies and learning strategies; however, most did not make a strong connection to PID. Further research is needed to better understand the tensions between personal and professional values, structural and power influences, discipline versus generic, and the role of workplace learning on PID.

Related Papers

Studies in Higher Education

Rob Macklin , Franziska Trede

This study examined the extant higher education literature on the development of professional identities. Through a systematic review approach 20 articles were identified that discussed in some way professional identity development in higher education journals. These articles drew on varied theories, pedagogies and learning strategies; however, most did not make a strong connection to professional identities. Further research is needed to better understand the tensions between personal and professional values, structural and power influences, discipline versus generic education, and the role of workplace learning on professional identities.

Rob Macklin

Bahijah Abas

Amandeep Singh

The academic profession is among a limited number of occupations that have attained the professional status associated with comparatively high levels of prestige, monetary rewards, security, and autonomy. Traits that most professions have in common include a specialized body of knowledge that supports the skills needed to practice the profession, a culture sustained by a professional association, an ethical code for professional practice, recognized authority based on exclusive expertise, and an imperative to serve the public responsibly (Greenwood, 1957; Silva, 2000). Students learn their chosen profession's abstract body of professional knowledge and its associated skills during lengthy degree programs and apprenticeships. Students also observe the behaviors, attitudes, and norms for social interaction prevalent among practitioners of their profession. They interpret their observations in light of their own prior experiences, their goals for the future, and their current sense of who they are and will try on possible professional selves to see how well they fit (Ibarra, 1999). In the process, each student is crafting a sense of identity as a particular type of professional. The period of doctoral preparation is particularly important because although identity is resistant to change, adaptations to one' s sense of self are more likely to occur when one is transitioning to a new role (Cast, 2003; Ibarra, 1999). According to Austin and McDaniels (2006), developing an identity as a professional scholar is an essential task for a doctoral student.

Sofiia Ozhaiska

Proceedings of the INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT CONFERENCE

George Dinu

The study draws on an IPA analysis of 8 interviews, conducted in 3 UK universities (Post/Pre 1992). It explores the perceptions of dual professionals, specifically: what aspects of professionalism are important to them, how they express their professional identity and negotiate it in an academic context. The focus of this paper is chiefly on how dual professionals conceive professionalism and how these beliefs affect their capacity to negotiate themselves in their new HE career. Insight into how these individuals negotiated their professional identities, as they experienced inbound trajectories ranging from peripheral to full membership of a university community is very relevant to those responsible for professional development. The findings may aid fellow academics and university management to consider, develop and create a sense of HE identity and belonging for dual professionals.

Marcelo Borrelli , Mario Carretero

PROF. DR. SUFIANA KHATOON MALIK

The study was conducted to compare practitioners’ perception about professional identity at higher secondary level. The purpose of the study was to equate practitioners’ perception about three components of professional identity (1) Who am I? (2) What is my role? (3) How I should be? The population of the study comprised male and female practitioners teaching at higher secondary level. Data was collected from 633 public and private sector college practitioners through disproportionate stratified sampling technique. Major findings of study were that there was no significant difference in professional identity of public and private sector practitioners; however, private sector college practitioners were found more concerned about improving themselves. It was concluded that the teachers from both sectors had same views about their description as a teachers and their role as a teacher but teachers of private sector were more concerned about how they should be. It was suggested that prac...

WHEN Women's Higher Education Network Annual Conference 2018

Susi Poli , Dr Amy Bonsall

Who am I? A scientist? A researcher? A teacher? A professional? A technician? Based on research, and with ample opportunity for discussion and exploration, get to grips with the complexity of identities in higher education and explore links to career pathways. Feeling as 'the other' even twice: as an individual in Professional Services and as a woman working in the Higher Education sector. This and much more to be explored in this workshop at WHEN, the first network gathering all women in HE.

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Forming Identities in College: A Sociological Approach

- Published: August 2004

- Volume 45 , pages 463–496, ( 2004 )

Cite this article

- Peter Kaufman 1 &

- Kenneth A. Feldman 2

1697 Accesses

61 Citations

9 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Using data from 82 in-depth interviews with a randomly selected sample of college students, we explore how these students are forming felt identities in the following domains: intelligence and knowledgeability, occupation, and cosmopolitanism. We study the formation of students' identities by considering college an arena of social interaction in which the individual comes in contact with a multitude of actors in various settings, emphasizing that through these social interactions the identities of individuals are, in part, constituted. In using a symbolic interactionist approach in our research in conjunction with consideration of the social structural location of colleges in the wider society, we demonstrate the sorts of information and insights that can be gained from a nondevelopmental approach to the study of college student change.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Social Identity Theory

The Role of TikTok in Students’ Health and Wellbeing

Ethan Ramsden & Catherine V. Talbot

Social Constructivism—Jerome Bruner

Antaki, C., Condor, S., and Levine, M. (1996). Social identities in talk: Speakers' own orientations. British Journal of Social Psychology 35 (4): 473–492.

Google Scholar

Bourdieu, P., and Passeron, J. C. (1990). Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture, Sage Publications, London.

Braxton, J. M. (ed.) (2000). Reworking the Student Departure Puzzle, Vanderbilt University Press, Nashville, TN.

Dannefer, D. (1984a). Adult development and social theory: A paradigmatic reappraisal. American Sociological Review 49 (1): 100–116.

Dannefer, D. (1984b). The role of the social in life-span developmental psychology, past and future. American Sociological Review 49 (6): 847–850.

Denzin, N. (1970). The Research Act in Sociology, Butterworth, London.

Dews, C. L. B., and Law, C. L. (ed.) (1995). This Fine Place so Far from Home: Voices of Academics from the Working Class, Temple University Press, Philadelphia.

Dey, I. (1993). Qualitative Data Analysis: A User-Friendly Guide for Social Scientists, Routledge, London.

DiMaggio, P. (1982). Cultural capital and school success: The impact of status culture participation on high school students. American Sociological Review 47 (2): 189–201.

Ethier, K. A., and Deaux, K. (1994). Negotiating social identity when contexts change: Maintaining identification and responding to threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67 (2): 243–251.

Feagin, J., Vera, H., and Imani, N. O. (1996). The Agony of Education: Black Students at White Colleges and Universities, Routledge, New York.

Feldman, K. A. (1972). Some theoretical approaches to the study of change and stability of college students. Review of Educational Research 42 (1): 1–26.

Feldman, K. A., and Newcomb, T. M. (1969). The Impact of College on Students, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

Goffman, E. (1959). Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Doubleday Anchor, Garden City, NY.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Goffman, E. (1967). Interaction Ritual: Essays on Face-to-Face Behavior, Pantheon, New York.

Granfield, R. (1991). Making it by faking it: Working-class students in an elite academic environment. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 20 (3): 331–351.

Hewitt, J. P. (1976). Self and Society: A Symbolic Interactionist Social Psychology, Allyn and Bacon, Boston.

Hogg, M. A., and Abrams, D. (1988). Social Identifications: A Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations and Group Processes, Routledge, London.

Hogg, M. A., Terry, D. J., and White, K. M. (1995). A tale of two theories: A critical comparison of identity theory with social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly 58 (4): 255–269.

Holland, D. C., and Eisenhart, M. A. (1990). Educated in Romance: Women, Achievement and College Culture, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Howard, J. A. (2000). Social psychology of identities. Annual Review of Sociology 26: 367–393.

Jencks, C. (1968). Social stratification and higher education. Harvard Educational Review 38 (2): 277–316.

Jenkins, R. (1996). Social Identity, Routledge, London.

Kaufman, P. (1999). The Production and Reproduction of Middle-Class Identities . Unpublished doctoral dissertation. State University of New York, Stony Brook.

Kaufman, P. (2003). Learning to not labor: How working-class individuals construct middle-class identities. The Sociological Quarterly 44 (3): 481–504.

Kinney, D. A. (1993). From nerds to normals: The recovery of identity among adolescents from middle school to high school. Sociology of Education 66 (1): 21–40.

Knox, W. E., Lindsay, P., and Kolb, M. N. (1993). Does College Make a Difference? Long-Term Changes in Activities and Attitudes, Greenwood Press, Westport, CT.

Lamont, M., and Lareau, A. (1988). Cultural capital: Allusions, gaps and glissandos in recent theoretical developments. Sociological Theory 6 (2): 153–168.

Lofland, J. (1969). Deviance and Identity, Prentice-Hall, Engklewood Cliffs, NJ.

Louis, K. S., and Turner, C. S. (1991). A program of institutional research on graduate education. In: Fetterman, David (ed.), New Directions for Institutional Research: Using Qualitative Methods in Institutional Research (No. 72), Jossey-Bass, San Francisco, pp. 49–64.

Markus, H., and Nurius, P. (1986). Possible selves. American Psychologist 41 (9): 954–969.

Maxwell, J. (1996). Qualitative Research Design: An Interactive Approach, Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

McCall, G. J., and Simmons, J. L. (1978). Identities and Interactions, Free Press, New York.

McMillan, J. H. (1987). Enhancing college students' critical thinking: A review of studies. Research in Higher Education 26 (1): 3–29.

Mead, G. H. (1967). Mind, Self, and Society, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Meyer, J. W. (1970). The charter: Conditions of diffuse socialization in schools. In: Scott, W. Richard (ed.), Social Processes and Social Structure: An Introduction to Sociology, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, pp. 564–578.

Meyer, J. W. (1972). The effects of the institutionalization of colleges in society. In: Feldman, Kenneth A. (ed.), College and Student: Selected Readings in the Social Psychology of Higher Education, Pergamon Press, Elmsford, NY, pp. 109–126.

Meyer, J. W. (1977). The effects of education as an institution. American Journal of Sociology 83 (1): 55–77.

Padilla, F. M. (1997). The Struggle of Latino/a University Students: In Search of a Liberating Education, Routledge, New York.

Pascarella, E. T., and Terenzini, P. T. (1991). How College Affects Students: Findings and Insights from Twenty Years of Research, Jossey-Bass, San Francisco.

Riesman, D., and Jencks, C. (1962). The visibility of the American college. In: Sanford, Nevitt (ed.), A Psychological and Social Interpretation of the Higher Learning, John Wiley & Sons, New York, pp. 74–192.

Rosenberg, M. (1986). Conceiving the Self, Robert E. Krieger Publishing Company, Malabar, FL.

Seidman, I. E. (1991). Interviewing as Qualitative Research, Teachers College Press, New York.

Silver, I. (1996). Role transitions, objects, and identity. Symbolic Interaction 19 (1): 1–20.

Silverman, D. (1993). Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analyzing Talk, Text and Interaction, Sage, London.

Smith, M. B. (1968). The self and cognitive consistency. In: Abelson, R. P., Aronson, E., McGuire, W. J., Newcomb, T. M., Rosenberg, M. J., and Tannenbaum, P. H. (eds.), Theories of Cognitive Consistency: A Sourcebook, Rand McNally, Chicago, pp. 366–372.

Snow, D. A., and Anderson, L. (1987). Identity work among the homeless: The verbal construction and avowal of personal identities. American Journal of Sociology 92 (6): 1336–1371.

Stets, J. E., and Burke, P. J. (2000). Identity theory and social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly 63 (3): 224–237.

Stewart, A. J., and Ostrove, J. M. (1993). Social class, social change, and gender: Working class women at Radcliffe and after. Psychology of Women Quarterly 17 (4): 475–497.

Stone, G. P. (1970). Appearance and the self. In: Stone, G. P., and Faberman, H. A. (eds.), Social Psychology Through Symbolic Interaction, Ginn-Blaisdell, Waltham, MA, pp. 394–414.

Stryker, S., and Burke, P. J. (2000). The past, present and future of an identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly 63 (4): 284–297.

Stryker, S., and Serpe, R. T. (1982). Commitment, identity salience, and role behavior: Theory and research example. In: Ickes, W., and Knowles, E. S. (eds.), Personality, Roles and Social Behavior, Springer-Verlag, New York, pp. 199–218.

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving College: Rethinking the Causes and Cures of Student Attrition (2nd Ed.) , The University of Chicago Press, Chiacgo.

Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., and Wetherell, M. S. (1987). Rediscovering the Social Group: A Self Categorization Theory, Blackwell, Oxford.

Turner, R. H. (1968). The self-conception in social interaction. In: Gordon, C., and Gergen, K. J. (eds.), The Self in Social Interaction, John Wiley & Sons, New York, pp. 93–106.

Weidman, J. C. (1989). Undergraduate socialization: A conceptual approach. In: Smart, J. C. (ed.), Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research ( Vol. 5 ), Agathon Press, New York, pp. 289–322.

Weigert, A. J., Teitge, J. S., and Teitge, D. W. (1986). Society and Identity: Toward a Sociological Psychology, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Sociology, State University of New York at New Paltz, New Paltz, NY, 12561

Peter Kaufman

State University of New York at Stony Brook, USA

Kenneth A. Feldman

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Kaufman, P., Feldman, K.A. Forming Identities in College: A Sociological Approach. Research in Higher Education 45 , 463–496 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1023/B:RIHE.0000032325.56126.29

Download citation

Issue Date : August 2004

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1023/B:RIHE.0000032325.56126.29

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- college effects

- college environment

- peer influence

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, academic identity and “education for sustainable development”: a grounded theory.

- Higher Education Development Centre, University of Otago, Dunedin, New Zealand

The research described in this article set out to explore the nature of higher education institutions’ commitment to teaching for social, environmental and economic justice in the context of the SDGs and to develop a theory of this phenomenon to support further research. The research used grounded theory methodology and took place over a two-month period in 2023. Cases were collected in four universities in New Zealand, India and Sweden and included interviews with individuals, participation in group activities including a higher education policy meeting, seminars and workshops, unplanned informal conversations, institutional policy documents and media analyses in the public domain. Cases were converted to concepts using a constant comparative approach and selective coding reduced 46 concepts to three broad and overlapping interpretations of the data collected, focusing on academic identity, the affective (values-based) character of learning for social, environmental and economic justice, and the imagined, or judged, rather than measured, portrayal of the outcomes or consequences of the efforts of this cultural group in teaching contexts. The grounded theory that derives from these three broad interpretations suggests that reluctance to measure, monitor, assess, evaluate, or research some teaching outcomes is inherent to academic identity as a form of identity protection, and that this protection is essential to preserve the established and preferred identity of academics.

1. Introduction

Many higher education institutions (HEIs) around the world have made some form of commitment to support the achievement of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals agreed by most of the nations on this planet in 2015. 1 For example, more than 1,500 universities from more than 100 countries have submitted portfolios to the 2023 Times Higher Education Impact Rankings ( Times Higher Education, 2023 ). The SDGs and the concept of sustainability relate equally to notions of social, environmental, and economic justice (sometimes described as the triple bottom line of people, planet and profit). It is to be noted that these current commitments built upon long-standing prior HEI commitments related to international agreements following on from the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development 1992, including in particular Agenda 21 ( United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, 1992 ). Institutional commitments to sustainability generally relate to institutional research, teaching and to university campuses (or “campus as role model”). It is also to be noted that, in the context of teaching, some commitments have been made at the individual institutional level; for example, those institutions whose leaders commit via the Talloires Declaration ( Association of University Leaders for a Sustainable Future, 1994 ) to “educate for environmentally responsible citizenship.” Some commitments occur at a national level, including for example Sweden’s commitment made in 2006 that all of its educational institutions will promote sustainable development explored by Finnveden et al. (2020) . The broad field of inquiry known as Education for Sustainable Development (ESD, sometimes as HESD in higher education contexts) provides the disciplinary focus to explore these commitments and, as with all disciplines in higher education, diverse perspectives on how it operates are inherent to its practices. Even so, that education should be for sustainable development and not simply about sustainable development is fundamental to its mission.

ESD practitioners are well aware of many of the challenges involved in utilising the social construct of higher education for social change, substantially reviewed in Barth et al. (2015) . Higher education has had to manage massification (increased registration without similarly increasing funding), its broadly middle-class and privileged nature (potentially undermining its efforts towards social justice), and the market-driven ethos of higher education nowadays. Universities also attract students with a wide range of personal ambitions and expectations. Some students choose to study in academic areas to which sustainability concepts make a natural and compelling contribution. Some students even choose to study programmes designed to educate sustainability professionals. But many students, perhaps most, study subjects for which sustainability has a more challenging or transient contribution. Higher education commitments and societal expectations, however, apply to all students, not only to those who express commitment to sustainability before they arrive. And, naturally, some academics in all disciplines are highly motivated towards sustainability and likely to ensure that their teaching addresses sustainability-related topics; but some less so.

Much effort has been expended by ESD practitioners to develop educational outcomes that may in some way align to institutional contributions to the achievement of the sustainable development goals with focus recently on the development of ESD competencies ( Brundiers et al., 2020 ); competencies that may allow those who learn them to operate in a sustainable society. Relatively little emphasis however has been placed on monitoring, measuring, assessing, evaluating or researching the educational outcomes achieved by university graduates. One of the first research-based indications that higher education was finding the mission of ESD problematic came from institutional research in the USA. The University of Michigan is an institution with a renowned sustainability focus. Using both quantitative and qualitative research approaches directed at student learning, this research found; “… no evidence that, as students move through [the University], they became more concerned about various aspects of sustainability or more committed to acting in environmentally responsible ways, either in the present moment or in their adult lives” ( Schoolman et al., 2016 , p. 498). Research that reflects similar concerns was reviewed by Brown et al. (2019) . Other than these expressions of concern, there is little evidence in the public domain that the mission of ESD is on track in our universities.

The author of the current article has explored institutional efforts and outcomes in the broad contexts of environmental education (EE) and ESD over several decades in several institutions and nations. No doubt all academic researchers believe that their research and their research questions are rather important. The current author is no different but emphasises here an observation that dictates choice of research methodology and the author’s personal role within the research. How humans interact with each other and with other life on our shared planet, and with the physical planet itself, has become in recent years an existential matter for humans and for many other species. Given the extent to which our universities teach people on our planet (for example, high proportions of young people in many nations pass through higher education. India is home to one sixth of the world’s human population and more than 25% of its young people pass through its higher education sector), and the accepted vital role of education in achieving the SDGs, their role needs to be seen as an important contributory factor. In this context, the institution of higher education does need to consider its role in the context of whether higher education teaching is predominantly leading to solutions or is, perhaps, more contributing to the problems that need solutions. This research addresses not the research that universities do, but rather the research that universities might not do, or are reluctant to do, involving the consequences of what they teach on what their students learn. The research described in this article set out to explore the nature of higher education’s commitment to teaching for social, environmental and economic justice in the context of the SDGs and to develop a theory of this phenomenon to support further research. The research occurred in four universities in New Zealand, India and Sweden. Analysis drew from Bourdieusian social theory ( Bourdieu, 1993 ), Kahan’s exploration of the measurement problem in climate-science communication incorporating identity protection ( Kahan, 2015 ) and psychological theories that link experience and affect to behaviour.

2.1. Methodological underpinning

Given the complex nature of the SDGs and of higher education teaching, research in this broad area is unlikely to have an existing and explanatory theoretical foundation, laying as it does at the intersection of many fields of higher education enquiry. Many factors are likely involved in this situation without necessarily being clearly and widely understood or necessarily related to one another. The research needs to consider the relevance of its lines of questioning to these constituent factors and even if the institution of higher education, gatekeeper to our shared conceptualisation of scholarship, is open to such lines of questioning.

Grounded theory developed in the social sciences, whose main epistemological interest is in explaining and predicting behaviour in social interactions. The overarching goal of grounded theory is to develop theory in such circumstances, with an implicit orientation towards action, but an explicit expectation that new theory will emerge though cycles of data collection, inductive analysis and speculation on theory. The constant comparative approach ( Corbin and Strauss, 2008 ) where new data always requires the researcher to compare current inductive imaginations with past theory-building to reassess its utility, is an abiding feature of grounded-theory research. Nevertheless, the extent to which theory emerges from the analysis, or is dependent on the prior knowledge and theoretical grounding of the researcher, is a contested point. Glaser and Strauss (1967) , the two main originators of grounded theory, originally stressed the importance of the researcher developing theoretical sensitivity, so as to be mindful of theoretical possibilities as cases are considered, but not to be highly dependent on prior understanding. Strauss and Corbin (1990) , in later manifestations of grounded theory, emphasised the inevitability of the researcher using their own personal and professional experience as well as knowledge gained from the relevant literature to build new theory. The research described here used grounded theory as perhaps the only research methodology capable of addressing the research question in the complex environment of international higher education and celebrates the past professional experiences of the researcher in international higher education, not to limit possibilities of new theoretical insights but to bring awareness of multiple discourses, incorporating already-rich explanatory insights, to the task. Charmaz and Bryant (2010) emphasise that modern, constructivist interpretations of grounded theory enable researchers to explore tacit meanings and processes in complex social systems and to challenge established explanations of social functioning.

Data contributing to grounded theory in social contexts is, unlike many other qualitative research methods, not based solely on interviews. Each datum is a “case” and may give rise to an individual “concept” that represents a unit of interest. As Corbin and Strauss (2015) emphasise; “ … it is concepts and not people, per se, that are sampled” (p. 135). Cases may include, as examples, interviews with people, interviews with groups, listening or participation in group activities such as conferences, seminars and workshops, informal conversations whether planned or not, publications, fieldnotes incorporating memoranda and reflective commentaries, webpages and press releases. Cases are collected by a process of “theoretical sampling” and are developed by the researcher recording and reflecting on planned and unplanned experiences. Cases are sampled continuously and included in the analysis as planned events, as accidental or coincidental happenings, and as the consequence of further development and refinement of a developing theory needing further and focussed clarification. Importantly, cases are not necessarily built from reoccurring themes or quantifiable circumstances. An individual conversation with a single discussant can have a powerful impact on a developing grounded theory. The iterative processes of data sampling, data analysis and theory development are, theoretically, ongoing until new data ceases to contribute to the development of theory, a situation known as theoretical saturation. As a constructivist approach, data are undoubtably influenced by the researcher’s personal perspectives, experiences, values and geographical settings and the researcher’s developing understanding is essentially reflexive in nature. To some degree, grounded theory must also be somewhat unplanned and opportunistic. It is not possible to describe in advance what sources will be involved, what lines of questioning in interviews or other forms of data collection will be involved, or what experiences will be influential in developing theory. In addition, as this is research based in more than one nation, individual national or individual institutional ethics authorities are not directly applicable. Internationally recognised ethical research principles of research have been adopted in this research, as described by the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council ( UKRI, 2021 ): minimising risks and maximising benefits for individuals and societies; respecting the rights and dignity of individuals and groups; ensuring that, wherever possible, participation is voluntary and appropriately informed; being conducted with integrity and transparency, with clearly defined lines of responsibility and accountability, making conflicts of interest explicit, and maintaining the independence of research. In this study, initially each case description in the author’s field notes included institution and nation, to contextualise the developing concept within it, but after the early stage of iterative data collection and analysis, the process of refining and amalgamating concepts stressed their educational, rather than geo-political contexts and allowed for a high degree of anonymity to be developed and maintained in their further analysis. Concepts described below protect the anonymity of their source, as individual, institution and nation, focusing on the author’s conception of the issue within, rather than its origin. In all cases concepts in this article are written in the author’s words, summarising each case as understood by the author, rather than as quotations attributable to groups, individuals, institutions or nations.

Data analysis starts by considering each case as a potential concept and allocating a code to it. Often a case needs to be broken into smaller constituent parts, each of which can be deeply analysed both as a possible contribution to new theory but also in the light of existing theory identified and understood by the researcher. Similar cases may be labelled with the same code. Coded elements become concepts and multiple concepts may be amalgamated or combined in some way as a higher-order category or phenomenon ( Strauss and Corbin, 1990 ). Although many different ways of exploring the relationships between concepts and categories have been described, Corbin and Strauss (2015) simplified the coding process to the three main features of conditions/circumstances, actions/interactions, and consequences/outcomes, and this simplified coding sequence was used in the research described here. Concepts are initially compared based on the conditions or circumstances in which they occurred. Subsequently concepts are related by their actions or interactions that occurred between them. Only then are concepts compared on the basis of their outcomes or consequences. The final element of grounded theory production is generally identified as “selective coding” and results in combinations of categories, where more than one category exists, to create one cohesive theory, or grounded theory.

Although a wide range of processes can be applied to research to evaluate its quality, the quality of qualitative research and in particular grounded theory is not evaluated according to measures of objectivity and significance, but according to criteria that stress utility and trustworthiness in the context within which the grounded theory has been developed. With reference to Guba and Lincoln (1989) four general types of trustworthiness in qualitative research, it is hoped that the credibility, transferability, dependability and confirmability of this analysis would be reasonable, given the diverse nature of the discussants and places, the past experience of the researcher in HE and ESD, and the ethical processes involved in analysis and reporting. Notably the grounded theory developed in this research takes cases from diverse sources in three different nations and abstracts these to the institution of higher education internationally. Its applicability in any particular nation or institution is necessarily limited. Limitations based on the happenstance of experiencing cases, and therefore of concepts, are inevitable in grounded theory research. Nevertheless, and in line with Thomas (2006) , the credibility of the grounded theory to arise from this analysis is being tested using diverse approaches of peer review and international public debate, including this publication, with expectations that academic readers of this article will look for resonance between it and their own experiences. Transferability and dependability of the analysis are tested, to a degree, by comparison with international literature within this article. Confirmability, in particular, has not been tested but may come later, as others work with, and within, similar groups of higher education people in these and in other nations.

2.2. Data analysis: cases, concepts, categories, and a grounded theory

Case collection for this article took place over a two-month period in 2023. Cases were collected in three nations and four universities. Case collection started in the author’s own institution, a research-intensive public university in New Zealand. Case collection continued in India, initially in a research-intensive public Indian Institute of Technology, involving participation in a policy workshop to which academics interested in India’s higher education expansion programme and university contributions to the Sustainable Development Goals were invited to contribute, and subsequently in a small, private university, with a known focus on equity and related social purposes. The final stages of case collection occurred in Sweden, in a research-intensive university. Reflection on cases and data analysis continued after this two-month period once the author had returned to New Zealand.

Beyond starting in the author’s own institution and nation, choice of nation in which to conduct this research was purposeful.

India has a population of over 1.4 billion and 25% of its young people attend universities. India has more than 1,000 universities, 42,000 higher education colleges, and more than 1.5 million academic staff. India’s 2020 National Education Policy (NEP) expresses an intention to raise its gross enrolment ratio to 50% by 2035, to restructure its education system to match India’s commitment to the Sustainable Development Goals, and to use higher education as a tool for social change, in particular in the context of equity and social justice. India implemented quota-based policies to address caste-based differences in university recruitment in the 20th Century (Reservation) and policies to address gender differences in university participation. Much more is planned.

… “The global education development agenda reflected in the Goal 4 (SDG4) of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by India in 2015 – seeks to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all” by 2030. Such a lofty goal will require the entire education system to be reconfigured to support and foster learning, so that all of the critical targets and goals (SDGs) of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development can be achieved ( NEP, 2020 , p. 3). … The National Education Policy lays particular emphasis on the development of the creative potential of each individual. It is based on the principle that education must develop not only cognitive capacities – both the “foundational capacities” of literacy and numeracy and “higher-order” cognitive capacities, such as critical thinking and problem solving – but also social, ethical, and emotional capacities and dispositions ( NEP, 2020 , p. 4). … 11.8. Towards the attainment of such a holistic and multidisciplinary education, the flexible and innovative curricula of all HEIs shall include credit-based courses and projects in the areas of community engagement and service, environmental education, and value-based education ( NEP, 2020 , p. 37).

Sweden is one of very few nations that has historically legislated that its universities are to educate for sustainable development. Since 2006, higher education institutions (HEIs) in Sweden, should according to the Higher Education Act, promote sustainable development (SD). In 2016, the Swedish Government asked the Swedish Higher Education Authority to evaluate how this role was proceeding. An academic article based on the study’s final report suggested that “Overall, a mixed picture developed. Most HEIs could give examples of programmes or courses where SD was integrated. However, less than half of the HEIs had overarching goals for integration of SD in education or had a systematic follow-up of these goals. Even fewer worked specifically with pedagogy and didactics, teaching and learning methods and environments, sustainability competences or other characters of education for SD. Overall, only 12 out of 47 got a higher judgement” ( Finnveden et al., 2020 , p. 1). The author’s enquiries focus in particular on exploring incidences of the systematic follow-up referred to by Finnveden et al. (2020) .

Arguably, the scale of India, and of its higher education system, suggests that, globally, what happens there in the context of ESD is somewhat more important than what happens in most other individual countries. It seems likely that more than 20% of the world’s academics and higher education students are Indian. Sweden’s historical commitment to promoting sustainable development via its education system makes it internationally recognised as a case of special interest. Despite its scale, New Zealand also has significant aspirations in the context of social justice, its colonial past, and waves of immigration. Although each of New Zealand’s eight universities has significant independence, a range of government measures directs many of their actions, for example, processes aimed at improving Māori and Pacific Islands student enrolment, retention and success (See for example TEC, 2023 , on equity funding). At present, attendance at university does not reflect either Māori aspirations for partnership, endorsed by the nations’ Treaty of Waitangi, or the aspirations of Pacifica people for equitable access to higher education, to the professions, to jobs, and to health care, social support and social inclusion in general. A key issue for Aotearoa New Zealand in the context of its Treaty of Waitangi and notions of partnership is the place of mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) in formal education. Seven professors from one New Zealand university recently questioned parity for mātauranga Māori with other bodies of knowledge, initiating considerable debate within the sector. Another university is addressing claims of institutional racism in these contexts. New Zealand also takes academic freedom seriously. It is legislated for in its Education Act, as is the principal aim of tertiary education of developing intellectual independence ( Shephard, 2020 , 2022 ). New Zealand may be a small nation, but these issues are directly relevant to discourses of ESD and are of international relevance.

Data collection and analysis proceeded in an iterative manner, within the constraints of a journey from New Zealand through India to Sweden and back to New Zealand. Elements of grounded theory methodology, particularly that involving constant comparison between data and developing theory, are difficult to delineate as method and result. Much that relates to method, therefore is interpreted in this analysis as result.

Initially, at a surface level, in each country, cases simply revealed known barriers to ESD, such as academics “ … keeping their heads down” (perhaps resulting in them not teaching for social, environmental or economic justice as anticipated in national and institutional policies) and suggestions by university academics, of schoolteachers “ … not being prepared or trained to teach sustainability” (perhaps as a consequence of university education departments’ practices but resulting in newly recruited HE students perhaps needing more learning than otherwise anticipated). These were initially coded as barriers, but as more cases were added they could be coded with more insight as, for example, lack of research into higher education practices and outcomes. At an early stage, however, in each nation, many cases needed to be coded as relating to values and attitudes, rather than to knowledge and skills. For example, an observation by a discussant who teaches in Development Studies, that students are good at critical thinking in the classroom but do not use their critical thinking skills to overcome typical prejudices. A different discussant confirmed that “Employers think our students are critical thinkers but may not be empathetic to disadvantaged people . ” Another discussant emphasised that “The State cannot legislate for attitudes … . ” Many such cases emphasised that ESD is inherently a quest for affective learning or values, attitudes and dispositions, rather than just for cognitive learning for knowledge and skills.

At particular stages in this enquiry, key events occurred that forced this researcher to re-evaluate the coding on previously assessed cases. For example, one discussant (who was personally highly active in promoting social purposes in their own institution) suggested that (in their experience) some university teachers simply did not identify with, or teach, a social purpose even though they may be, in other respects, very effective academics within their own disciplines. This same discussant confirmed that some institutions did not apply drivers or incentives to direct their academics towards the social purposes espoused by that institution, and (most meaningfully for the researcher) doubted that such academics should feel obliged to be directed by these drivers, even if they existed. This discussant felt strongly that teachers should teach as their conscience directs them to, and that institutions should encourage this to happen. This discussant was verbalizing a concept relating to the behaviours of individual academics and of institutions that appears to stem from the professional identities of individual academics, and the organisational behaviours of academic institutions, that prioritises academic freedom. As a result of this case, many other cases needed to be re-examined and recoded to include aspects of academic identity and academic freedom. School teachers not being prepared or willing to teach sustainability becomes a possible consequence of the expression of academic freedom by academics in education departments (where schoolteachers are trained or educated) and of the organisational behaviour of institutions charged with the responsibility to train or educate schoolteachers. This case also interacted with others to emphasise the complexity of related circumstances in higher education. While this discussant perhaps emphasised the academic freedom of academics and of institutions to teach as they thought fit, other cases emphasised that university teachers or groups of university teachers should not be allowed to teach as they see fit. Some discussants in a group conversation suggested that other academics in their institution were strongly opposed to that group’s experimental and experiential approaches to teach “for” sustainable development and in particular expressed doubt that it was the role of higher education to encourage students to become emotionally attached to ideas such as sustainability, social justice or sustainable development. Discussants in this conversation, on the other hand, felt strongly that becoming emotionally, or affectively, involved with sustainability issues was at the heart of their nation’s commitment to sustainable development and to their institution’s obligations to educate for sustainable development. Supporting this case, other discussants in other institutions shared concerns that academics who become emotionally involved in their teaching are subject to burn-out, and that such academics who teach broader educational objectives, such as sustainability, are highly vulnerable in higher education. Many such conversations implicitly addressed the roles that academics, academic groups and institutions should have and the internal and external drivers that enable, limit or maintain these roles, and collectively identified diverse viewpoints in these regards.

Noticeable within this data was that while many, perhaps most, discussants were happy to reflect on what HE should be doing, and how HE should operate, and what it should achieve, this was generally based on deeply-held beliefs about HE, personal experience within HE, and perceptions of academic and disciplinary identity held by academic people, rather than on particular knowledge of the sustainability-related outcomes or consequences of HE, either in particular circumstances, relating to particular teachers or courses, or collectively, relating to whole institutions. Implicit within concepts such as “Academics in this university simply do not want to learn how best to teach students to be for sustainability” is not a sound evidence base of knowledge that higher education students are not learning to be for sustainability, but a deeply held belief that they should be for sustainability, a concern that at present and on balance they may not be, and an experience-based inference that academics in general do not wish to apply themselves to this end. Implicit within concepts such as “What can higher education give to society in the future? Transmission of information is no longer enough . ” is not a sound evidence base of knowledge that higher education is not currently delivering something more than “Transmission of information” but a strong and personal feeling that this is what is currently, and on balance, happening now. Of course, much within this interpretation depends on how knowledge is perceived in this context. Notably, expressed concerns about: “increasing inequality,” “racism, discrimination, and bullying” ; “ [being] disadvantaged by language, lack of cultural capitol, lack of preparation, lack of support” ; “Higher education need [ing] a substantial and broad change to perform a social purpose” ; and “It [being] difficult to measure or monitor change in values” relate not in particular to individual courses or programmes where sustainability might be a predetermined focus, and where students have elected to study and learn in this context, but to higher education experiences in general.

In some contexts, perhaps knowledge can be contextualised as what personal experience suggests might be the case, but in most HE contexts knowledge claims have higher levels of accountability. In all disciplines, for example, knowledge claims are based on and develop from scholarly research that builds on prior knowledge, contributes to future interpretations through knowledge-based discourse, and is circulated in peer-reviewed publications. Different disciplines have different means to develop disciplinary knowledge and different ways to describe knowledge, but no disciplines base their knowledge claims solely on the deeply held beliefs of practitioners. Advances in knowledge within the disciplines is hard-won. Higher education is not, of course, simply a collection of disciplines, but differences in how the institution of higher education conceptualises its own development, from how it conceptualises the development of disciplines that exist within it, are strongly evident in the concepts that contribute to the present research. A core element of the grounded theory developing here is that much relating to outcomes and consequences within this broad ESD context is not based on knowledge, but on hopes, aspirations, good intentions, assertions, and beliefs about what should happen, and on diverse expressions of the academic identity and mission of individual academics and of universities relating to how these things should come about.

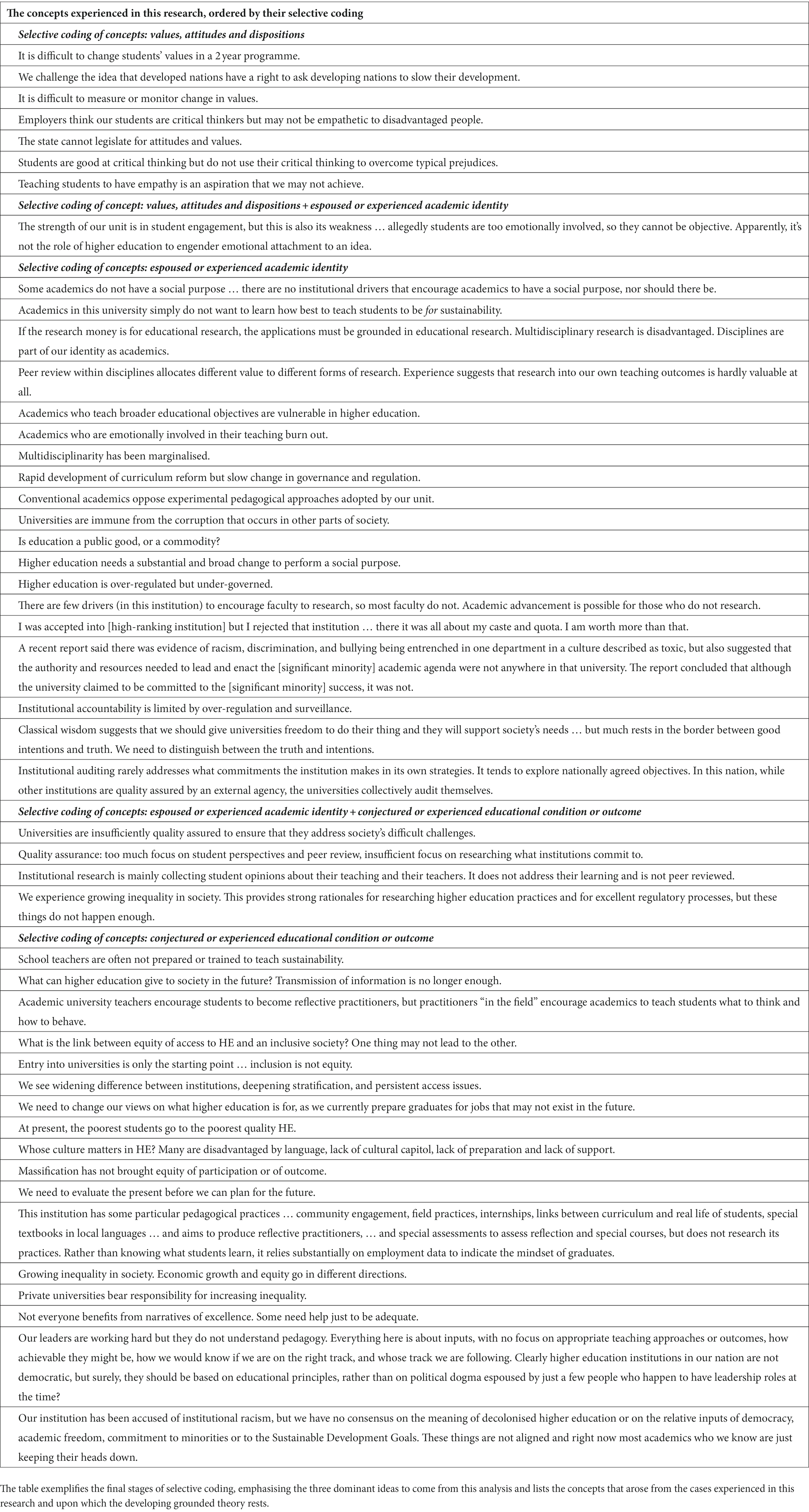

The process of selective coding therefore started with three broad and overlapping interpretations of the data collected. The first focuses on academic identity, or the cultural identity of higher education academics, and perceptions of what people in this cultural group think they or others should do, think they should not do, and think that they actually do and achieve, particularly as these things relate to learning in the affective domain. The second identifies affect and emotion as a central feature of the concepts addressed in this research and of the nature of ESD. The third addresses the imagined, or judged, rather than measured nature of the outcomes or consequences of the efforts of this cultural group, or application of this academic cultural identity, in teaching contexts. Nowhere within this research was an assertion of academic or institutional identity based on a sound knowledge base of what graduate outcomes were being achieved, on balance, in the name of social, environmental and economic justice. Even expressions of lack of sustainability-related achievements were based on assumption, supposition and expressions of barriers to ESD. Expressions of higher education quality in these contexts are based on inputs rather than outcomes. The grounded theory that derives from these three broad interpretations suggests that reluctance to measure, monitor, assess, evaluate or research teaching outcomes (or the consequences of the expression of academic identity in the context of teaching), so as to give expression to ESD, is inherent to this identity as a form of identity protection, and that this protection is essential to preserve the established identity of academics in the face of threats imposed by learning in the affective domain. The grounded theory suggests that academic identity in the context of sustainability focuses on achieving cognitive outcomes, not affective outcomes, and that protection of this identity-ideal requires academics to minimise their engagement with educational outcomes that stress emotional engagement with concepts or ideas (other than those that enhance or protect academic identity itself or, to a degree, that are explicit within particular disciplines or professions), even to the point of being unwilling to explore the emotional or affective outcomes of their teaching, individually or at an institutional level. As a consequence, the institution of higher education is unable to report its teaching-related contribution to sustainability outcomes, at the same time as being able to pronounce its positive contributions to sustainability through its very genuine research and campus-sustainability efforts. Table 1 lists concepts that arose from the cases experienced in this research and upon which the developing grounded theory rests, and the final stage of selective coding, emphasising the three dominant ideas to come from this analysis. Table 1 represents, in effect, one step in a pathway to an integrated set of conceptual hypotheses developed from empirical data (as described by Glaser, 1998 ).

Table 1 . Development of a grounded theory to explain the nature of HEI’s commitment to teaching for social, environmental and economic justice in the context of the SDGs.

4. Discussion

Selective coding of the concepts developed in this research emphasises three concepts that together say much about the nature of HEI’s commitment to teaching for social, environmental and economic justice in the context of the SDGs; academic identity, concerns about affect and emotion as central features of social, environmental and economic justice, and the imagined, or judged, rather than measured nature of the outcomes or consequences of university teaching in this context. Grounded theory seeks to find commonality between these concepts and to progressively develop a theory with explanatory power that could potentially suggest action. The theory that has emerged from this research suggests that reluctance to measure ESD is inherent to the academic identity dominant in higher education as a form of identity protection, essential to preserve the established identity of academics in the face of threats imposed by teaching, and learning, in the affective domain.

It is demonstrably the case that higher education teaching is undertaking ESD and achieving outcomes in this context. An abundance of higher education research and institutional contributions to international collaborations such as the AASHE STARS programme ( STARS, 2023 ) make it clear that many higher education institutions and many individual academics in these institutions are using their teaching to achieve significant sustainability-related outcomes. In addition, an abundance of guidance (see for example, UNESCO, 2017 ) and commitments from academic leaders in higher education institutions (see for example Association of University Leaders for a Sustainable Future, 1994 ) confirms that such actions are significantly promoted and supported in and by the sector. But the concepts explored in this study point to some significant limitations in these efforts and in these outcomes. Concepts such as “Employers think our students are critical thinkers but may not be empathetic to disadvantaged people” and “Teaching students to have empathy is an aspiration that we may not achieve” reinforce the message that ESD is a quest for affective outcomes ( Shephard, 2008 ). “It is difficult to measure or monitor change in values , ” suggests that such affective outcomes are difficult to realise ( Craig et al., 2022 ). “The state cannot legislate for attitudes and values . ” and “Apparently, it’s not the role of higher education to engender emotional attachment to an idea . ” point not only to the challenges of teaching in the affective domain, but also to perceptions of what might be missing in the context of a functional conceptualisation of ESD.

A significant body of research and analysis nowadays suggests that affective attributes provide the link between what people know, what skills people learn to put their knowledge to effect and what people choose to do with the knowledge and skills that they have learned ( Shephard et al., 2015 ). Fishbein and Arjen’s Theory of Reasoned Action and Arjen’s Theory of Planned Behaviour emphasise the extent to which affective attributes contribute to decision making (see Madden et al., 1992 for a comparison). Harari, summarising much academic progress in psychology, suggests that “most human decisions are based on emotional reactions and heuristic shortcuts rather than on rational analysis” ( Harari, 2018 , p. 222). In this context, much ESD research in the last decade has focused on teaching students a range of competencies that explicitly link cognitive and affective attributes, in the hope that those with appropriate competencies will behave in appropriate ways. As defined by Rieckmann (2011) “ Competencies may be characterised as individual dispositions to self-organisation which include cognitive, affective, volitional (with deliberate intention) and motivational elements; they are an interplay of knowledge, capacities and skills, motives and affective dispositions. Consequently, these components are part of each competency, not having to be regarded independently, but in their interaction. Competencies facilitate self-organised action in various complex situations, dependent on the given specific situation and context (p. 4).” ESD practitioners do not agree on the definitions of “disposition” ( Shephard, 2022 ) but few would argue with its essential affective nature or that those who do not successfully learn to be disposed to particular actions are unlikely to perform these actions in challenging circumstances. The concept “Students are good at critical thinking but do not use their critical thinking to overcome typical prejudices” points to academic success in the cognitive domain but academic failure (in the context of education for sustainable development) in at least one conceptualisation of the affective domain of learning. Graduates becoming disposed to particular (sustainability-related) actions is inherent to the difference between education about sustainability and education for sustainability. Recent and more historical research supports this assertion. Recent research on links between academic development support for university teachers and university teachers’ perspectives on how such support affects their teaching, suggested “Educators clearly express that they understand the concept ‘about’ SD, but there are only vague expressions of a developed teaching repertoire to address education ‘for’ SD in their teaching practice” ( Persson et al., 2023 , p. 197). A recent survey of 58,000 schoolteachers conducted by Education International and UNESCO suggests that “Teachers understand the importance of the cognitive, behavioural and socio-emotional learning dimensions across all four themes. However, teachers feel more confident teaching cognitive skills, and less confident and knowledgeable about behavioural learning and socio-emotional perspectives, especially in ESD” ( UNESCO, 2021 , p. 13). Back in 2012, Shephard and Furnari explored what university teachers think about education for sustainability. They identified four significantly and qualitatively different viewpoints, only one of which advocates for sustainability. The other three viewpoints did not, and each had “distinct characteristics that prevent those who own them from using their position within the university to encourage students to act sustainably” ( Shephard and Furnari, 2013 , p. 1,577).

Links between affect, emotion and university learning are embedded in this discourse. The concept “Apparently, it’s not the role of higher education to engender emotional attachment to an idea . ” provides one helpful interpretation of the role of higher education and of issues that higher education teachers may have with not only teaching in the affective domain (a long-standing element of ESD discourse, reviewed by Shephard, 2008 ) but also distinctions between teaching students in general and teaching students to become professionals ( Shephard and Egan, 2018 ). Few will doubt the interplay between affect and emotion (indeed emotion provides a key element of some definitions of affect) or the explicit role of affect in professional learning. Key attributes of all professions are lists of professional values that underpin the profession and, for example, professional medical educators openly teach and assess professional values in medical schools throughout the world (reviewed by Shephard and Egan, 2018 ). The concept “Apparently, it’s not the role of higher education to engender emotional attachment to an idea.” clearly has no hold on medical educators. Medical educators have no issues in role modelling and teaching these professional values, or emotional attachments to ideas, because they are, often, professionals themselves and these ideas are accepted facets of professional identities that need to be taught and managed ( Howe, 2003 ). Similar arguments can no doubt be made with respect to the identities of professional schoolteachers and professional engineers. Perhaps the same arguments apply to sustainability professionals ( Wiek et al., 2011 ), with respect to sustainability values, but not to students in general, most likely enrolled in non-professional courses ( Shephard, 2015 ). Teaching affective outcomes to professional students to whom particular professional values are an accepted attribute of the profession appears to be unproblematic. Teaching sustainability values to non-sustainability professionals is likely as problematic as it appears to be for students in general.

The idea of academic identity is, therefore, important to this analysis. Much research in recent years has focused on academic identity in the context of professional roles and professional identity. The research suggests that who we think we are influences what we do, and that people also become what they are because of what they do and what they experience while doing it. “The relationship is thus complex, reciprocal, unfixed and open to change” ( Watson, 2006 , p. 510). Although this identity discourse emphasises the diversity of academic identity ( Drennan et al., 2017 ) research has tended to focus on situations where identities are under threat, challenging to maintain, or influential in directing action. McCune has studied the issues involved in sustaining identities that encompass deep care for teaching in research-led universities; suggesting that “maintaining engagement with teaching in contemporary higher education is likely to involve identity struggles requiring considerable cognitive and emotional energy on the part of academics … ” ( McCune, 2021 ). McCune’s study identified considerable tensions as academics endeavoured to undertake their diverse academic roles. Participants in that research “ often described considerable stress and talked about putting a lot of thought and effort into understanding and working with these tensions (p. 29).” Nixon (2020) explored the impact of the UK’s higher education’s market-driven order on academic identities to claim that “ Academic identity is now bound into this new order. It is almost impossible to opt out given what is at stake—not just personally and professionally, but institutionally. The stakes are high: increased government funding, increased and enhanced staffing levels, more research students, enhanced facilities and resources, higher national and international profile , etc. Not to compete for these stakes appears to be at best self-defeating and at worst plain perverse: to be ‘professional’ is to enter wholeheartedly into the game; to stay on the sidelines is to be ‘unprofessional.’ For anyone who questions the premises upon which the competitive game is being played the space for maneuverability is highly restricted. The orderly identity denotes ‘professionalism’ and is commensurate with professional advancement and institutional loyalty. It would appear—within the current UK context—to be the only identity available (p. 13).” Nixon summarises some research that suggests that this increasingly conforming identity leads to less time on teaching, poorer quality teaching and research outputs focussed on particular formats, audiences, and outlets. Nixon’s analysis looks beyond the UK to suggest “… the focus on global university rankings is occasioning a more extensive drift towards international conformity (p. 18).” Yang et al. (2022) explored how multiple and fragmented identities of academics are integrated in a culture of performativity. It is necessary, therefore, to reflect on the concept “Apparently, it’s not the role of higher education to engender emotional attachment to an idea . ” through a lens ground by increasing conformity to a competitive market-driven academic identity and the interplay of cognitive and emotional tensions of the academics involved. Clegg and Rowland (2010) examined the interplay between reason and emotion in higher education in the context of an exploration of kindness. They rejected “ the dichotomy between emotion and reason and the associated gendered binaries (p. 719)” but accepted the subversive nature of what they proposed. They suggested that “ what is subversive in thinking about higher education practice through the lens of kindness is that it cannot be regulated or prescribed (p. 719)” but concluded that universities make it hard for academics to be kind ( Clegg and Rowland, 2010 ). Although kindness itself was not a core feature of the concepts explored in the current research, links between emotion, or affect, and academic regulation, or prescription, were.

Academic identity also relates strongly to academic accountability and rationales for academics and their institutions to monitor, measure or research their academic outcomes, rather than simply state what they aim for or what they hope they will be. Although the concepts explored in the current research point to academic unwillingness to embrace this culture of accountability in the context of teaching, there is no doubt that incentives to be impactful, and to measure this impact, are extant also in the context of research. For example, research impact has been an important measure in the UK’s Research Excellence Framework since 2014. Impact contributes to an overall assessment of an institution’s research, and considerable funding and prestige is attached to it. In 2021 impact was assessed using case studies submitted by institutions to demonstrate the nature of the impact that each institution valued. Watermeyer and Tomlinson (2022) extend an international discourse on neoliberal, market-driven rationales for producing evidence of economic and societal impact. These authors suggest that although a designation of being impactful may support a sense of self-worth and be advantageous to an individual academic’s own professional profile, it may also lead to identity dispossession and a sense of being exploited by their universities, which appropriate their impact for positional gain. They identify a culture of competitive accountability and the privileging of “appearance” in rationalisations of the value of publicly funded research ( Watermeyer and Tomlinson, 2022 ).

Some research points specifically to tensions in maintaining an academic identity in sustainability teaching contexts. Hegarty (2008) argues that the identity of academics hinges on them being accepted as “knower with status” (p. 684) and that this runs contrary to their inevitable and challenging position as co-learner in our collective exploration of the relatively new academic enquiry of sustainability. Hegarty also emphasises the collective and individual values, beliefs, traditions and structures inherent to the academic role and contributory to status and hierarchy. To that we should add the demands and power of a profession that has long cherished and promoted peer review as the arbiter of quality. Only the most determined and committed would risk being different in the face of review by peers. Nixon’s diagnosis of “the only identity available” ( Nixon, 2020 , p. 13) is all the more powerful once the expectations of ESD are added to the mix. Conformity to an established academic order is also a conclusion from recent research exploring university teachers’ perspectives on gender, caste, merit and upward social mobility in university functioning, and staffing, in India. Dhawan et al. (2022) propose the presence of a hegemonically created status-quo focused on elitist social control rather than social justice.

The concepts explored in this research, therefore, converge on the nature of ESD as a quest for affective learning outcomes, on the problematic position of affect in an increasingly limited academic identity, and on the reluctance of the academy to research its own teaching practices to discover the extent that ESD learning in the affective domain could be understood and communicated. All three phenomena are well documented in disparate higher education discourses but their convergence in this study has led to the grounded theory proposed here. The grounded theory to emerge from this research suggests that academics’ reluctance to research their teaching practices in ESD contexts is not simply a dislike of being held accountable, but a protective response to circumstances that might otherwise compromise an idealised academic identity. An idealised academic identity neither acknowledges a role in teaching their students whether or not to behave in accordance with social, environmental and economic justice, nor accepts a responsibility to monitor, assess, evaluate, measure or research the impact that their teaching has on these learning outcomes. For individuals to do so would undermine their preferred identity. Not researching their teaching practices, in ESD contexts, could be seen as an abrogation of their academic responsibility in the context of the many promises made by academic leaders on their behalf, but academic reasoning, in their world of high status maintained by peer-review, reasonably identifies such outcomes as inconsequential in comparison with losing credibility within their own academic social domain.

Two inter-related current theories provide support for the grounded theory that holds identity protection as a core element of HEI’s commitment to teaching for social, environmental and economic justice in the context of the SDGs.

Bourdieusian social theory suggests that social groups construct social fields within which social interactions, often of the competitive kind, occur ( Bourdieu, 1993 ). Players or agents in the field are characterised by particular habitus (or combinations of dispositions) and the possession of various forms of capital which are exchanged in social interactions. Dominant players in the field possess the most capital and so are able to direct the rules of the field and are often invested in maintaining the status quo by devising rules that favour them. Insurgents generally have less capital and seek to change the rules, mostly unsuccessfully. As with all hegemonic systems, the rules favour dominant players, but subordinate players enable dominants by accepting the rules as culturally appropriate. Most fields are subject to larger fields which have some capacity to change the rules. (Higher education, as a social field, can be significantly destabilised by government action). Bourdieusian social theory provides a general commentary on education’s tendency to reproduce the values and structures of the society that sponsors it and suggests that harnessing the power of university teaching for social, environmental and economic change will not be easy. Government intervention may change the rules or destabilise the currencies of academic capital but expecting academics to do this themselves appears to be irrational.

While Kahan’s analysis of climate-change denial does not reference Bourdieu, there are commonalities. Kahan asks why intelligent and rational people deny climate change and proposes a form of identity protection as rationale. Kahan’s analysis explores beliefs and suggests that they reflect not only individual’s need to relate to science but also to “enjoy the sense of identity enabled by membership in a community defined by particular cultural commitments” ( Kahan, 2015 , p. 1). In these contexts, Kahan suggests that climate-change deniers rationalise their relative sense of belonging to wider society and to more immediate social groups. They reasonably rationalise that their individual impact on climate change is insignificant, but standing out from their immediate cultural community would have very significant impacts on them as individuals and on their own cultural community. Climate-change denial in this analysis is a highly rational response to protect an individual and collective identity. In the current study, academic disinclination to measure, monitor, assess, evaluate or research the impacts of teaching on the affective, sustainability-related attributes of graduates is similarly a highly rational response to protect individual and collective academic identity. Even so, the theory does suggest that academics make a choice. By this theory most academic people find it more reasonable to mislead their societal sponsors about the impact of their sustainability-related efforts rather than to threaten their own academic identity. By this theory, academic leaders who commit their academic institutions to “educate for environmentally responsible citizenship” or to “create an institutional culture of sustainability,” without establishing evaluative procedures to check that their institution is on track, are particularly implicated in an identity choice far more heinous than climate change denial. Only those on the margins of established academic communities, those with little to lose, and those with extraordinary personal drive towards social, environmental and economic justice will have the personal resources to challenge established academic identity. Even so, attempts to enlighten academia via peer-reviewed analysis in a professional community dominated by peer review appears to be quixotic.

5. Conclusion

The research described in this article set out to explore the nature of higher education’s commitment to teaching for social, environmental and economic justice in the context of the SDGs and to develop a theory of this phenomenon to support further research. The research produced three broad and overlapping interpretations of the data collected; involving the cultural identity of higher education academics, the position of affect as a central feature of ESD, and the imagined rather than measured outcomes of the efforts of this cultural group in teaching contexts. The grounded theory to emerge from this research suggests that academics’ reluctance to research their teaching practices in ESD contexts is a protective response to circumstances that might otherwise compromise their idealised academic identity and personal position within their academic community.

It is to be stressed that this grounded theory is, at this stage, no more than a theory, based on a particular interpretation of data gathered in a far from quantitatively representative manner. It specifically does not suggest that higher education institutions are not meeting teaching-based objectives in the context of the SDGs, but rather emphasises that they cannot know what their impact is, in general, and on balance, so cannot know if their impact is broadly positive, or broadly negative. The theory has significant explanatory power, but whether it can lead to action remains to be seen. According to this grounded theory, progress depends on whether members of the academic community continue to choose to protect their idealised academic identity or decide to address the question of whether our teaching contributes more to the world’s sustainability problems or to their solution.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because the studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required from the participants or the participants’ legal guardians/next of kin in accordance with the national legislation and institutional requirements. Internationally recognised ethical research principles have been adopted in this research, as described by the UK’s Economic and Social Research Council ( UKRI, 2021 ) and as described in detail within the article.

Author contributions

KS: Writing – original draft.