- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to footer

Learning in Room 213

Lessons, Strategies & Digital Courses

Scaffolding Literary Analysis

March 30, 2017 by Room 213 Leave a Comment

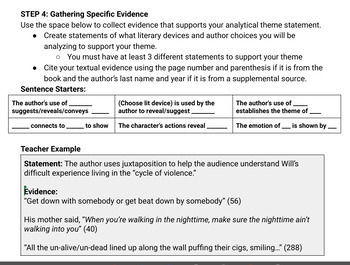

Since I want them to identify author purpose and technique, I look for short, interesting pieces of non-fiction where the writer has used a variety of ways to develop a thesis, ones where they have moved beyond just examples and statistics to the use of analogy or figurative language to push an idea. Always, we look at word choice and its effect.

I do the same with independent reading. Each day we do a short mini-lesson on how authors create meaning, perhaps how they use metaphor. I show them a mentor text; then, they will look for similar techniques in the books they are reading. They will either write a short reflection or discuss what they’ve found with a partner. It’s all really low stakes — rarely for a mark — so students can learn to do a literary analysis without the stress of a poor result.

Focus on skills, not content

Now, regardless of the genre I use, the focus is on the skills the students need to build, not on the text itself. If students can identify how a metaphor affects meaning in a news story or a song, they should be able to do so in a piece of classic literature too.

So, I focus on the skill, find accessible texts to teach them that skill, and then use a gradual release of responsibility to transition them into analyzing more difficult texts. You can read more about this process on a post I wrote called, Teaching Students to Analyze Text.

Before I ask students to become more independent, I do a short lesson on note-taking and using post-it notes effectively. I’ve written about this before ( check it out here ), and can’t stress enough how important this is. We can’t just expect kids to know how to take notes, how to discern what’s good to remember and what isn’t. Taking part of a class to teach them good note-taking skills is time very well spent, and helps you to scaffold literary analysis

Create an environment that encourages risk taking

One of the most important steps in teaching my kids to analyze lit, is setting an environment that allows them to do so. As I said earlier, this stuff is hard, and kids hate to be “wrong” in front of their peers. Therefore, we need to create a climate where they feel safe to make an educated guess, to put forward theories and to be “wrong.”

In order to do this I work hard to show them that there usually is not one “right answer.” In fact, complex texts should be open to multiple interpretations. In order to do this, you need to consider how you respond to student comments. It’s so natural to say “that’s right” or “great answer”, but comments like “that’s an interesting observation. Can you (or anyone else) add to that?” or, “that’s a great point. Does anyone see it differently?” will encourage students and promote the idea that multiple interpretations are desirable.

I start this process by modelling my own thinking when I see a difficult text for the first time. I’ll put a poem or a passage on the smart board, and highlight and underline, question and comment. I do all of this in front of the students. I’ll put forth a theory: I think the author is suggesting… however, I’m not quite sure how this image/idea/point fits in. What do you guys think? This last question is so important. I –the teacher– am asking their advice. I’m not certain and I need to collaborate to get closer to an answer. I will also encourage them to disagree with me — and to provide proof for why they do.

We also spend a lot of time fostering effective group discussions. I put one group in a circle in the middle of the room and give them a topic to discuss, something from the literature we are studying. We start the discussion and I model what good group work looks like. Then we switch it up and try it with another group. I encourage debate and say things like: I agree with Andrew’s point and I’d like to add… Or, I might say I can see why you’d think that, but consider this… Mostly, I encourage kids to use more textual evidence to back up their points.

Be willing to let them work it out

I do a lot of group work when kids are learning to analyze text . They are expected to come to class with notes they take while reading. Then, I put them together and let them hash it out. The question is always the same: what’s the purpose of this chapter/scene/section and how doe the author achieve it? The group meeting allows them to have exploratory discussion, so they can “think it out.” They discover what they know and what they need to figure out. They ask lots of questions. They pull ideas together while building on each one. They refute each other’s ideas in order to fine-tune their thinking on the ideas in the text.

If however, they just can’t get it, or I notice that they have veered too far off the path, I ‘ll give them something to consider, a clue. I’ll tell them to think about it and come back to them later. If they still haven’t figured it out, I’ll give them another clue. If they still can’t get it, I will direct them more specifically.

After the group work, we always reconvene and have a full class discussion. At that point, I already know which group has come up with some insightful observations and so I can direct the discussion by asking them to contribute their ideas. However, I don’t usually start with that group. I’ll first ask a group that’s kinda there and then ask the other group what they can add. It’s a little manipulative, but the class feels like they’re working together rather than me just filling in the blanks for them. And this goes back to the first question–they know I’m never going to stand at the front of the class and give them the answers. They know they have to work to find them. Because of this, I think it’s more likely that they might actually do some of the work.

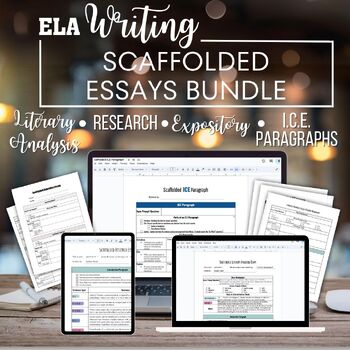

After we’ve done enough of these activities, students will have to show me what they’ve learned in an assessment. I always start with something short — maybe a paragraph that analyzes a quote or a character — and give them some formative feedback. Then, when I think they’re ready, we will write a literary essay.

There’s nothing more satisfying than helping a kid find success in an area that they find difficult. They may never come to love the process of analyzing lit, but they sure will find pride in knowing that they can. I’ve got a ton of exercises and activities that I use to get my kids to think about texts. You’ll find a lot of them here on my blog and also in this bundle of Critical Thinking Activities for Any Text .

Would you like more strategies for teaching analysis? Read this post.

Reader Interactions

March 31, 2017 at 12:42 am

I enjoyed this post and plan to put a lot of it into action. I have a couple of questions, though. First, I noticed that you said that your students "are expected to come to class with notes they take while reading." Do your students reliably complete their assigned reading? At the school where I teach, no teachers assign reading in the standard level classes – the students won't do it, so all reading is done in class, which is time-consuming and often boring. In the honors classes, we do assign reading, but I would say that maybe 20% of the students actually do the reading, 60% look at sparknotes or watch the movie, and 20% don't bother to pretend that they've read at all. Could you write a post about how you get your students to complete their assigned reading?

Second, when you have your students analyzing in small groups rather than as a class, how do you prevent students from arriving at incorrect interpretations? I don't mean different interpretations – I agree that great literature is open to multiple interpretations – but sometimes they come up with an interpretation that completely misses the mark (especially with poetry). I'm sure you catch many errors while walking around, but probably not all. Do you just let them make mistakes?

Thanks for some great ideas!

March 31, 2017 at 9:51 am

Those are great questions, Erin. I will do a follow up post later today!

March 31, 2017 at 6:16 pm

Erin, If you re-read the post, I've added some ideas that deal with your question about incorrect interpretations. I'm also about to publish a new post that deals with your question about reading. Thanks for asking!

March 31, 2017 at 10:47 pm

Thank you! Love your blog!

April 1, 2017 at 1:03 pm

One of the techniques I use to scaffold analysis skills is a good film analysis. After all, they have been watching movies longer than they have been reading, right? By starting in their comfort zone, they can find success early and keep at it when it gets a bit more challenging. I use consistent language when analyzing film for maximum transfer to analyzing lit. What choices did the director make? What effect do they have on the audience? (Costuming is always a great place to start for character analysis.) Two units I have especially loved pairing film analysis with close reading are To Kill a Mockingbird and Romeo and Juliet (1997 version!). Not only do these quality films provide many opportunities for analysis, it also hurts my literary heart just a little less knowing that students at least are getting "the whole story" when we inevitably can't read the entire piece. We are usually alternating between film analysis and lit analysis- which can be tiring, but nearly so much as the human cliff notes song and dance of in class readings! I have been doing this successfully for a couple of years now and cannot believe the difference it has made in my students' understanding. Music videos also work great with poetry and commercials are perfect for rhetorical strategies of speeches!

Thank you so much for addressing this tough skill. I found this post this morning while browsing Pinterest and will be following for more great ideas!

April 2, 2017 at 10:46 am

Great ideas, Sarah. I always start my IB class with viewing Dead Poets Society. After we watch, I assign youtube clips to groups and have them analyze what the director was trying to achieve in the scene and the techniques used to achieve it. Like you, I see it as an accessible way to get them into analysis. Thanks for sharing!

July 4, 2018 at 2:57 pm

This information is really helpful in analysing Scaffolding

July 23, 2018 at 2:30 pm

Great post, I appreciate you and I would like to read your next post. Thanks for sharing this useful information http://bit.do/esgNA

February 19, 2019 at 5:21 am

Hi, Thanks for sharing such a great information. We are leading Scaffolding Australia manufacturer. If you are looking for finest scaffolding services then contact to BSL Australia.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Scaffolding Literary Analysis: Step-by-Step to Reach Success

February 25, 2017 Carla Assessment/feedback , Education , Reading/Writing Workshop , Teaching Techniques 6

Let’s face it — for most students, literary analysis is just plain hard.

And teaching it is even harder.

All too often, when teachers feel pressured to cover curriculum, they focus on teaching content rather than skills, when in actual fact, skills are what our students will take away from our classrooms. We tend to think that students will somehow develop these abilities (through osmosis?) as we teach our content. But the truth is, most students need explicit teaching of skills, which should be taught through our content.

In other words, content knowledge is not the goal — skills are the goal and content is the medium through which we teach those skills. Reading analysis can be difficult to teach, though, and in order to do it well, we need to break it down into small, manageable chunks which we teach and reteach as often as necessary.

Our Language Arts teachers recently noticed that students were having difficulty answering reading comprehension questions. In 7 th grade, for their reading assignments, students were expected to include an opinion, evidence to support their opinion, and an explanation of how that evidence supported their answer. By 12 th grade, they needed to include a thesis statement and several paragraphs of evidence, along with analysis of that evidence. At all grade levels students were struggling with these different components, and our teachers decided that they needed to work together to break down the lessons and scaffold the learning until students could work independently.

An example of teaching literary analysis in 8 th grade:

In 8 th grade, teachers decided that their students should be able to do the following:

- restate the question in their answer

- paraphrase or quote evidence

- make an analysis by referring back to the question, contextualizing, and explaining how their evidence proves their quote

The 8 th grade lessons:

- Students were given a reading response assignment and, along with their teacher, they created a rubric to guide them.

- After they wrote their responses, their teacher, Laura, identified the elements that her students found difficult.

R.A.C.E anchor chart

She gave them a mini-lesson on the different parts of a response (R.A.C.E.). The R.A.C.E. criteria are posted on an anchor chart in the classroom. Anchor charts scaffold the learning by allowing students to refer to them whenever they need them.

- Then Laura asked her students to highlight their work with different colors to identify each part of the R.A.C.E. process.

- After color coding, students needed to self-assess their literary analyses by grading themselves on their previously-created rubric.

Entrance slip to practice restating questions

- In subsequent reading responses, in order to help students learn to independently self-assess and revise their work, students had to highlight their work using the R.A.C.E. criteria. If they noticed that they were missing elements, they were to add them before handing their work in.

- After the students had worked on several responses, Laura asked her students to look back over all of their feedback, identify three opportunities for improvement, and then rewrite their latest response, trying to progress in the areas they’d identified.

Thanks to Laura’s explicit teaching of skills, most of the 8th grade students are now managing to write cohesive, in-depth analyses of their reading.

Teamwork rocks! It’s by working together that our Language Arts teachers are making such an incredible difference. They’re using this type of scaffolding at each grade level, helping students incorporate new skills. In the 9 th grade, students are taught to expand on their responses by including a strong hook in their introduction and by supporting their opinions with two pieces of evidence. Stepping stones are added until, by grade 12, students are comfortable writing a literary analysis paper, fluidly incorporating quotes into their work, and clearly analyzing how the evidence connects to their opinions.

Scaffolding helps students develop a growth mindset — and when they finally master a skill that seemed impossibly difficult at first, they develop self-confidence and begin to take risks. They’re also developing independence: learning to self-assess and revise their work without needing as much feedback from teachers. Although teachers need to put in a lot of time and effort (and have a fair bit of patience!) during the scaffolded lessons, this kind of teaching pays off in the long run. Students are eventually able to work independently, and their assignments are much stronger.

Hi Carla- I enjoyed learning about what 8th grade literary analysis should look like. I often have students to restate their questions and paraphrase but, sometimes second guess what I am asking of my students and worry I am asking too much of them. This post helped me identify where they should be. Thanks for posting such a comprehensive piece.

Thanks for reading Anthony! Our teachers also struggled with the feeling that they’re expectations were too high. Clearly defining what they should expect at each level and then working with the students to make sure they understood the expectations, has made all the difference. Students are feeling successful and confident.

As a former AP literature teacher, I can say that this skill building is essential. Even when they got to me in 11th or 12th grade, I would still need to spend time teaching the nuts and bolts of analysis using various scaffolding methods, TPCASTT. SOAPSTone or DIDDLS, or a few others. The scaffold made it very clear what the student was looking for, and after some handholding and walking through a few of the types, they caught on rather quickly and left the scaffolding behind. You article contains some great tips that I can use with my middle school teachers to help get that skill development started earlier, and to the benefit of our students. Thanks so much!

I’m glad this was helpful to you Tom. We have an amazing group of teachers and they were all working hard to help their students, but they felt frustrated because they didn’t clearly know what was expected at each grade level. Hashing out what students should be able to do at each grade level and to clarify their role in this continuum of learning has helped all of them feel more effective and less frustrated. And our kids are rocking reading responses!

Hi Carla! You write so well. Love your blog posts. This one just shows what is possible when care and imagination come together. I think the strategy is a powerful one and the expectations per grade easily achieved–as you can see. I will share this with my English-teacher friends. #sunchatblogger

Thanks Gillian! Having teacher share their weaknesses and truly collaborate has given incredible results…they’re an inspiring team!

Leave a comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Notify me of followup comments via e-mail. You can also subscribe without commenting.

Copyright © 2024 | MH Purity WordPress Theme by MH Themes

11 Effective Scaffolding Strategies for Secondary ELA

Looking to bridge the learning gaps in your classroom? Help students work through complex topics and texts with effective scaffolding strategies. Learn how to use scaffolded instruction to establish a supportive learning environment where every student has the opportunity to succeed.

I think we can all agree that students come to us with varying learning preferences and abilities. Given the limited time and resource constraints, it can feel like an uphill battle to help every student succeed, especially those who struggle to grasp new concepts.

Enter scaffolded instruction.

Having a strong understanding of scaffolding strategies, including when and how to implement them, is a vital component of success for all students, no matter their age or abilities. These must-know teaching strategies help students go from feeling overwhelmed and wanting to give up to finding the confidence to complete complex tasks successfully.

After reading this post, you’ll better understand how to bring the benefit of scaffolding into your classroom.

What is Scaffolding in Secondary Education?

Much like scaffolding in construction is used to support the building of a structure, scaffolding in education supports skill building and, ultimately, academic achievement. It involves breaking down complex skills into manageable steps to provide guidance and support until students can tackle tasks independently.

This method is vital in navigating the secondary ELA landscape, where students face higher-level reading comprehension, critical thinking, literature analysis, and writing skills. It eases students into gradual progression where they can confidently approach more complex materials and apply higher-level skills.

Scaffolded Learning vs. Differentiated Learning

It’s true that scaffolded learning and differentiated learning are connected, but they are not the same thing. Scaffolded learning provides temporary structured support toward gradual independence around a concept or skill. Differentiated learning focuses on modifying instruction and learning materials to meet individual needs. That said, scaffolding strategies are often employed in support of differentiated instruction.

Whether employed together or individually, these two teaching strategies help you create a more inclusive and effective learning environment for all.

The Benefits of Scaffolded Instruction

There are several benefits of scaffolded instruction in secondary ELA or any classroom, including:

- Fostering a positive and supportive learning environment

- Giving students built-in “check-points” to ask for help

- Empowering teachers to provide additional support as needed

- Encouraging students to build skills gradually while increasing confidence

- Proactively minimizing student learning gaps

- Reducing student frustration, overwhelm, and confusion

- Engaging students in the learning process

- Breaking down complex concepts and tasks into manageable steps

- Laying a foundation for independence and autonomy

- Promoting information retention and a deeper understanding of the material

- Allowing teachers to adapt lessons to meet student’s needs

- Ensuring mastery of foundational skills before moving on to more advanced concepts

Now that you know the benefits, you might be wondering how to effectively incorporate scaffolded instruction into your classroom, bringing me to the part I know you’ve been waiting for.

Scaffolding Strategies for the ELA Classroom

When choosing a scaffolding strategy for your classroom, it’s important to consider the skills and concepts at hand and your student’s needs and abilities. To help you get started, here are some scaffolding strategies I’ve found particularly useful in secondary ELA.

1. Pre-Teach Vocabulary

You never want terminology to be the roadblock for student success. Therefore, it’s helpful to introduce and explain key vocabulary words before delving into new concepts or reading material. Additionally, take time to review the terms in context to deepen student understanding. By pre-teaching vocabulary , you equip students with the necessary language and knowledge needed to comprehend the material at hand.

This strategy enhances their understanding of context and enables a smoother engagement with the content. It is especially beneficial for texts with challenging or subject-specific language, ensuring students can navigate and comprehend the content more effectively.

2. Preview Reading Materials

To ease students into complex reading material, provide opportunities for them to dip their toes into the context before diving in. Previewing reading material involves providing an overview, discussing key themes, or introducing relevant background information. Therefore, students understand what to expect from a text, promoting better comprehension and stronger engagement.

For example, allow students to flip through the text to gauge the structure, language, and content, encouraging them to ask clarifying or curious questions before reading. This will help activate prior knowledge, establish context, and spark interest, making the text more accessible.

For more pre-reading activities, read this post here.

3. Start Short

Whether you’re introducing a new genre, theme, unit, or writing style, consider starting with a shorter assignment first. Maybe that involves reading a short story or poem to familiarize students with a particular genre, writing style, or theme before reading a full-length text. It could also look like having students write a full-length essay in phases and providing feedback after each step before putting it all together.

Not only does this allow you to provide quick and targeted feedback along the way, but it also minimizes student overwhelm and procrastination with larger or longer assignments. Students will have more confidence going into the more complex material.

4. Activate Prior Knowledge

Before diving into a new concept, tap into your students’ prior knowledge. Calling upon what they already know helps establish a sense of connection to and relevance of the material, helping to build confidence and intrinsic motivation. It also sets the stage for a deeper understanding of what they are about to learn.

Try kicking off your lesson with a brief discussion, relevant questions, a KWL chart , or a quick review of previously learned material.

5. Provide Graphic Organizers

Graphic organizers are powerful learning tools that provide visual and structured guidance for students as they learn. These visual note-taking tools help them process information, follow steps, and organize their thoughts before, during, or after learning. It can help students organize their thoughts and grasp the relationship between information, guiding them through anything from text analysis to essay planning.

For example, help students organize their thoughts with Venn diagrams, mind maps, plot diagrams, or flow charts. They can work through the resources in groups, as a class, or independently, allowing you to employ them for various purposes.

Check out my various FREE printable graphic organizers!

6. Support with Visual Aids

While graphic organizers help students process and organize information in a visually structured fashion, it’s not the only way we can support students with visual aids. Charts, video clips, images, and diagrams provide visual cues to help students process and comprehend new information and concepts.

They are also a great tool to ensure you are supporting various learning styles while helping students make connections between visual representations and the content you are teaching. This is a particularly effective scaffolding strategy for struggling students and English language learners.

7. Encourage a Think, Pair, Share Approach

While some scaffolding strategies require planning, this strategy can be implemented on the fly as needed (#convenient). The “Think, pair, share” approach encourages students to activate critical thinking. It involves students individually considering a question or prompt, discussing their thoughts with a partner, and then sharing their ideas with the whole class. Similarly, you can encourage students to engage in a quick “turn and talk” where they share their ideas with their neighbors.

Either way, it promotes collaboration and active participation while enhancing both comprehension and communication skills. This strategy gives them time to work through their thoughts in stages, learn from one another, and minimize the fear of sharing one’s thoughts with the class.

8. Show, Don’t Just Tell

We often tell our students to “show, not tell” in descriptive writing. We can take our own advice when it comes to scaffolding. Sometimes, students need more than verbal explanations, needing to see a concept or skill in action . Modeling is a powerful scaffolding strategy that involves demonstrating a skill or concept before expecting students to try it themselves. Pair modeling with thinking out loud as you walk students through the process to target both auditory and visual learners.

Whether analyzing a poem, annotating a passage, or writing a strong thesis statement, a well-executed model can help students understand the steps they can implement independently.

9. Ask Guiding Questions

Information overload is very much a thing. Therefore, it’s not uncommon for some students to struggle to identify essential information or organize their thoughts. This is especially true for middle-grade learners transitioning away from text-dependent questions and working on developing higher-level thinking and inferential analysis skills.

Posing open-ended questions will help stimulate critical thinking and guide students through the thought process while teaching them what kinds of questions they can ask themselves in future scenarios. Rather than giving students the answers, these guiding questions prompt students to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information independently.

Here is a list of questions you can use to scaffold literary analysis.

10. Teach in a Series of Mini-Lessons

When introducing new and complex concepts to your students, consider breaking them down into smaller, more focused lessons. Each mini-lesson should include instruction, modeling, and guided practice that target specific learning outcomes.

This structure will give students the opportunity to concentrate on one element at a time, making complex concepts more manageable. Meanwhile, you will have opportunities to assess student understanding along the way, providing additional instruction or support as needed before moving on.

11. Utilize Thinking Stems

For some students, the biggest roadblock is figuring out how to articulate their thoughts. They have an idea of what they want to say but need help figuring out how to say it. Providing students with thinking stems in a simple yet effective scaffolding strategy that offers a starting point during discussions or written responses.

Thinking stems serve as a scaffold for students to articulate their thoughts more effectively, helping them overcome the challenge of initiating responses by providing a structured starting point. This strategy promotes critical thinking and communication skills, encouraging students to express their ideas with greater clarity and coherence.

When In Doubt, Chunk It Out

Here’s the bottom line: breaking down complex tasks into smaller, more manageable chunks makes learning more accessible for all students. Whether closely analyzing a text or preparing for a challenging writing assignment, breaking things down and providing guidance along the way helps prevent information overload and supports student understanding.

While it may take a little more time and planning, the results are worth it—trust me. Scaffolding will lead to student confidence, independence, and, ultimately, success. I mean, come on—what more could we ask for?

What scaffolding strategies have you used in your classroom? Share them in a comment below!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Scaffolding Academic Literacy with Low-Proficiency Users of English pp 41–70 Cite as

Scaffolding the Construction of Academic Literacies

- Simon Green 2

- First Online: 01 February 2020

624 Accesses

Green considers key policy questions in the planning of academic literacy instruction in higher education. Green first considers the nature of scaffolding in academic literacy and then considers three questions: Who should receive academic literacy instruction? How discipline-specific should academic literacy instruction be? What focal areas should academic literacy instruction consider? Green argues for universal academic literacy instruction; for discipline-specific instruction; and for instruction that focuses on context, genre and rhetorical practice.

- Universal academic literacy provision

- Discipline-specific instruction

- Literacy context

- Rhetorical practice

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

https://library.leeds.ac.uk/info/1401/academic_skills .

https://www.llc.leeds.ac.uk/ .

https://www.leeds.ac.uk/info/130567/language_centre .

http://www.oaaa.gov.om/Program.aspx#GeneralFoundation .

https://www.cas.edu.om/# .

Angelova, M., & Riazantseva, A. (1999). “If you don’t tell me, how can I know?” A case study of four international students learning to write the U.S. way. Written Communication, 16 (4), 491–525.

Google Scholar

Bakhurst, D., & Shanker, S. (2001). Jerome Bruner: Language, culture, self . London: Sage.

Bawarshi, A. (2003). Genre and the invention of the writer: Reconsidering the place of invention in composition . Logan: Utah State University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Bawarshi, A., & Reiff, M. J. (2010). Genre: An introduction to history, theory, research and pedagogy . West Lafayette, IN: Parlor Press.

Bazerman, C. (2013). A rhetoric of literate action: Literate action (Vol. 1). Anderson, SC: Parlor Press.

Bazerman, C., & Prior, P. (2004). What writing does and how it does it: An introduction to analyzing texts and textual practices . Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Belcher, D. (1994). The apprenticeship approach to advanced academic literacy: Graduate students and their mentors. English for Specific Purposes, 13 (1), 23–34.

Article Google Scholar

Bharuthram, S., & McKenna, S. (2006). A writer-respondent intervention as a means of developing academic literacy. Teaching in Higher Education, 11 (4), 495–507.

Blakeslee, A. M. (1997). Activity, context, interaction, and authority: Learning to write scientific papers in situ. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 11 (2), 125–169.

Braine, G. (1988). Two commentaries on Ruth Spack’s “initiating ESL students into the academic discourse community: How far should we go?” A reader reacts. TESOL Quarterly, 22 (4), 700–702.

Bruce, I. (2008). Academic writing and genre . London: Continuum.

Carter, M. (2007). Ways of knowing, doing, and writing in the disciplines. College Composition and Communication, 58 (3), 385–418.

Casanave, C. (1995). Local interactions: Constructing contexts for composing in a graduate sociology program. In D. Belcher & G. Braine (Eds.), Academic writing in a second language: Essays on research and pedagogy (pp. 83–110). Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing.

Cheng, A. (2008). Analyzing genre exemplars in preparation for writing: The case of an L2 graduate student in the ESP genre-based instructional framework of academic literacy. Applied Linguistics, 29 (1), 50–71.

Cline, Z., & Necochea, J. (2003). Specially designed academic instruction in English (SDAIE): More than just good instruction. Multicultural Perspectives, 5 (1), 18–24.

Clughen, L. (2012). Writing in the disciplines: Building supportive cultures for student writing in UK higher education . Bingley: Emerald.

Connor, U., & Mayberry, S. (1996). Learning discipline-specific academic writing: A case study of a Finnish graduate student in the United States. In E. Ventola & A. Mauranen (Eds.), Academic writing intercultural and textual issues (pp. 231–253). Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Chapter Google Scholar

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (1993). The powers of literacy: A genre approach to teaching writing . London: Falmer.

Coxhead, A. (2000). A new academic word list. TESOL Quarterly, 34 (2), 213–238.

Deane, M., & O’Neill, P. (2011). Writing in the disciplines . London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Devitt, A., Reiff, M. J., & Bawarshi, A. (2004). Scenes of writing: Strategies for composing with genres . New York: Addison Wesley Longman.

Dong, Y. (1996). Learning how to use citations for knowledge transformation: Non-native doctoral students’ dissertation writing in science. Research in the Teaching of English, 30, 428–457.

Dudley-Evans, T. (2001). Team-teaching in EAP: Changes and adaptations in the Birmingham approach. In J. Flowerdew & M. Peacock (Eds.), Research perspectives on English for academic purposes (pp. 225–238). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dudley-Evans, T., & St. John, M. J. (1988). Developments in English for specific purposes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Echevarría, J., Vogt, M. E., & Short, D. (2008). Making content comprehensible for English language learners: The SIOP model . Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Fishman, S. M., & McCarthy, L. (2001). An ESL writer and her discipline-based professor: Making progress even when goals don’t match. Written Communication, 18 (2), 180–228.

Flower, L. (1987). Interpretive acts: Cognition and the construction of discourse. Poetics, 16 (2), 109–130.

Flowerdew, J. (1993). Content-based language instruction in a tertiary setting. English for Specific Purposes, 12 (2), 121–138.

Flowerdew, J. (2000). Discourse community, legitimate peripheral participation, and the nonnative-English-speaking scholar. TESOL Quarterly, 34, 127–150.

Freedman, A. (1987). Learning to write again: Discipline-specific writing at university. Carleton Papers in Applied Language Studies, 4, 95–115.

Freedman, A. (1993). Show and tell? The role of explicit teaching in the learning of new genres. Research in the Teaching of English, 27 (3), 222–251.

Gentil, G. (2005). Commitments to academic biliteracy: Case studies of Francophone university writers. Written Communication, 22 (4), 421–471.

Gosden, H. (1996). Verbal reports of Japanese novices’ research writing practices in English. Journal of Second Language Writing, 5, 109–128.

Green, S. (2013). Novice ESL writers: A longitudinal case-study of the situated academic writing processes of three undergraduates in a TESOL context. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 12 (3), 180–191.

Green, S. (2016). Teaching disciplinary writing as social practice: Moving beyond ‘text-in-context’ designs in UK higher education. Journal of Academic Writing, 6 (1), 98–107.

Gustafsson, M., & Jacobs, C. (2013). Editorial: Student learning and ICLHE—Frameworks and contexts. Journal of Academic Writing, 3 (1), ii–xii.

Heyda, J. (2006). Sentimental education: First year writing as compulsory ritual in US colleges and universities. In L. Ganobscik-Williams (Ed.), Teaching academic writing in UK higher education (pp. 154–166). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hirvela, A. (2004). Connecting reading and writing in second language writing instruction . Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Hyland, K. (2002). Specificity revisited: How far should we go now? English for Specific Purposes, 21 (4), 385–395.

Ivanič, R. (1998). Writing and identity . Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Johns, A. (1988). Two commentaries on Ruth Spack’s “initiating ESL students into the academic discourse community: How far should we go?” Another reader reacts. TESOL Quarterly, 22 (4), 705–707.

Johns, A. (2008). Genre awareness for the novice academic student: An ongoing quest. Language Teaching, 41 (2), 237–252.

Johns, A. (2011). The future of genre in L2 writing: Fundamental, but contested, instructional decisions Journal of Second Language Writing, 20 , 56–68.

Johns, A., Bawarshi, A., Coe, R. M., Hyland, K., Paltridge, B., Reiff, M. J., et al. (2006). Crossing the boundaries of genre studies: Commentaries by experts. Journal of Second Language Writing, 15, 234–249.

Kalantzis, M., & Cope, B. (2012). Literacies . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lea, M. R. (2004). Academic literacies: A pedagogy for course design. Studies in Higher Education, 29 (6), 739–756.

Lea, M. R. (2013). Reclaiming literacies: Competing textual practices in a digital higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 18 (1), 106–118.

Lillis, T. (2001). Student writing: Access, regulation, desire . New York: Routledge.

Lillis, T. (2006). Moving towards an ‘academic literacies’ pedagogy: Dialogues of participation. In L. Ganobscik-Williams (Ed.), Teaching academic writing in UK higher education (pp. 30–45). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Lillis, T., & Scott, M. (2008) Defining academic literacies research: Issues of epistemology, ideology and strategy. Journal of Applied Linguistics, 4 (1), 5–32.

Macken-Horarik, M. (2002). ‘Something to shoot for’: A systemic functionalist approach to teaching genre in secondary school science. In A. Johns (Ed.), Genre in the classroom (pp. 17–42). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Martin, J. (2009). Genre and language learning: A social semiotic perspective. Linguistics and Education, 20 (1), 10–21.

Marx, K., & Engels, F. (1970). The German ideology . London: Lawrence & Wishart.

McCarthy, L. (1987). A stranger in strange lands: A college student writing across the curriculum. Research in the Teaching of English, 21, 233–265.

Medway, P., & Freedman, A. (2003). Genre in the new rhetoric . Abingdon: Taylor & Francis.

Mercer, N. (1995). The guided construction of knowledge: Talk amongst teachers and learners . Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Mitchell, M., & Evison, A. (2006). Exploiting the potential of writing for educational change at Queen Mary, University of London. In L. Ganobscik-Williams (Ed.), Teaching academic writing in UK higher education (pp. 68–84). Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nesi, H., & Gardner, S. (2012). Genres across the disciplines: Student writing in higher education . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Piaget, J. (1977). The essential Piaget . New York: Basic Books.

Sadler, D. R. (2013). Opening up feedback: Teaching learners to see. In S. Merry, M. Price, D. Carless, & M. Taras (Eds.), Reconceptualising feedback in higher education (pp. 54–63). London: Routledge.

Spack, R. (1988a). Initiating ESL students into the academic discourse community: How far should we go? TESOL Quarterly, 22 (1), 29–51.

Spack, R. (1988b). Two commentaries on Ruth Spack’s “initiating ESL students into the academic discourse community: How far should we go?” The author responds to Johns. TESOL Quarterly, 22 (4), 707–708.

Spack, R. (1997). The acquisition of academic literacy in a second language: A longitudinal case study. Written Communication, 14 (1), 3–62.

Susser, B. (1994). Process approaches in ESL/EFL writing instruction. Journal of Second Language Writing, 3 (1), 31–47.

Swales, J. M. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Swales, J. M. (1998). Textography: Toward a contextualization of written academic discourse. Research on Language and Social Interaction, 31 (1), 109–121.

Swales, J. M. (2004). Research genres: Explorations and applications . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tang, R. (2009). A dialogic account of authority in academic writing. In M. Charles, D. Pecorari, & S. Hunston (Eds.), Academic writing: At the interface of corpus and discourse (pp. 170–188). London: Continuum.

Tardy, C. (2005). “It’s like a story”: Rhetorical knowledge development in advanced academic literacy. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 4 (4), 325–339.

Tardy, C. (2009). Building genre knowledge . West Lafayette: Parlor Press.

Tribble, C., & Wingate, U. (2013). From text to corpus: A genre-based approach to academic literacy instruction. System, 41 (2), 307–321.

Turner, J. (2011). Language in the academy: Cultural reflexivity and intercultural dynamics . Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Turner, J. (2018). On writtenness: The cultural politics of academic writing . London: Bloomsbury.

van der Veer, R., & Valsiner, J. (Eds.). (1994). The Vygotsky reader . Oxford: Blackwell.

Verenikina, I. (2008). Scaffolding and learning: Its role in nurturing new learners. In P. Kell, W. Vialle, D. Konza, & G. Vogl (Eds.), Learning and the learner: Exploring learning for new times (pp. 161–180). Wollongong: University of Wollongong.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wertsch, J. V. (1985). Vygotsky and the social formation of mind . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

White, R. V., & Arndt, V. (1991). Process writing . London: Longman.

Wingate, U. (2012). Using academic literacies and genre-based models for academic writing instruction: A ‘literacy’ journey. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 11 (1), 26–37.

Wingate, U. (2015). Academic literacy and student diversity: The case for inclusive practice . Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Woods, D., Bruner, J., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17, 89–100.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Education, University of Leeds, Leeds, West Yorkshire, UK

Simon Green

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Simon Green .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Green, S. (2020). Scaffolding the Construction of Academic Literacies. In: Scaffolding Academic Literacy with Low-Proficiency Users of English. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39095-2_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-39095-2_3

Published : 01 February 2020

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-39094-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-39095-2

eBook Packages : Social Sciences Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Original article

- Open access

- Published: 27 November 2019

Scaffolding argumentative essay writing via reader-response approach: a case study

- Mojgan Rashtchi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7713-9316 1

Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education volume 4 , Article number: 12 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

5840 Accesses

3 Citations

Metrics details

The variety of activities and techniques suggested for improving the writing skill shows that EFL/ESL learners need scaffolding to gain mastery over it. The present study employed the reader-response approach to provide the assistance EFL learners require for writing argumentative essays. Five upper-intermediate EFL learners in a private class participated in the qualitative case study. The participants were not selected from the fields related to the English language and did not have any previous instruction on literary texts. During the treatment that took 20 sessions, each session 2 h, the participants read five short stories. Different classroom activities were used as sources of information, which helped the researcher to collect the required data. The classroom activities consisted of group discussions, writing tasks, and responses to the short stories that helped the learners to reflect on the short stories. Think-aloud protocols helped the researcher to learn about the participants’ mental processes during writing. The semi-structured interviews provided the researcher with the information necessary for a deeper understanding of the efficacy of the classroom procedure. As the results of the study showed, successful writing requires manipulation of meta-cognitive strategies and thought-provoking activities. Although the findings of the study cannot be generalized, they can inspire EFL/ESL teachers and material developers to seek a variety of procedures in their approaches to teaching writing.

Introduction

EFL/ESL learners encounter enormous challenges for mastering the writing skill, which is essential to learning the English language. One source of the problem is traceable to the learners’ inefficiency in self-expression. Usually, language learners do not know how to verbalize their ideas, nor do they know how to organize their thoughts and write about a subject. In writing classes, learners not only should be instructed on the mechanics of writing, but also they should be taught how to use thinking skills. As Kellogg ( 1994 ) argues, “thinking and writing are twins of mental life” (p. 13), and writing requires tasks such as problem-solving, decision-making, and reasoning. Writing about what one knows, as Kellogg argues, is a self-discovery as much as it is one way of communication with others. However, excellence in writing requires excellence in thinking and requires systematic thinking ( Paul, 1993 ). One should be able to arrange one’s thoughts in a progression that makes it accessible to others.

High-quality writing, then, is produced by someone with specific standards for both thinking and writing. As Lipman, Sharp, and Oscanyan ( 1980 ) assert, “if the thinking that goes on in a conversation is densely structured and textured, that which goes in the act of writing can be even more so” (p. 14). For successful writing, student-writers not only should express viewpoints but also they need to provide logical reasons, support their ideas, and organize them. Therefore, one requirement in teaching writing to EFL/ESL learners is to employ techniques and strategies that can enhance the thinking skills of the student-writers. The reader- response approach in the present study was implemented to do so.

Besides, one issue that Iranian EFL learners confront is the difference between the organizational patterns of English and Persian argumentative texts, which magnifies the challenge they encounter while writing. As found by Ahmad Khan Beigi and Ahmadi ( 2011 , p. 177), Persian paragraphs are circular, metaphorical, and follow “Start-Sustain-Turn-Sum” structure, whereas English argumentative essays are straightforward and linear and follow “Claim-Justification-Conclusion or Introduction-Body-Conclusion” pattern. Also, contrary to English students who write “monotopical” essays, which add “unity to the overall paragraph organization”, Iranian students tend to use more than one topic sentence and thus write multi-topical paragraphs as the result of the influence of different organizational patterns of English and Persian (Moradian, Adel, & Tamri, 2014 , p. 62; Rashtchi & Mohammadi, 2017 ). Thus, reflection and response to literary texts were manipulated to help the EFL participants in the present study overcome the two-fold problem they might encounter in argumentative essay writing.

Using literature is by no means a novel idea in ESL/ EFL classes and has been extensively discussed by several scholars in the field (e.g., Gajdusek, 1988 ; Oster, 1989 ; Spack, 1985 ). The present study differs from the previous ones due to its underlying assumption that employing a scaffolded reader-response approach can change writing “from an intuitive, trial-and-error process to a dynamic, interactive and context-sensitive intellectual activity” (Hyland, 2009 , p. 215). In this endeavor, reading short stories and creating personal interpretations could shape the participants’ viewpoints, organize their thoughts, and help them produce compositions that conform to the English language structure.

Literature review

The role and use of literature in teaching writing have been a source of controversy in the studies related to the writing skill. Belcher and Hirvela ( 2000 ) in their comprehensive article about employing literature in L2 composition writing found the manipulation of literary texts in writing classes to be questionable, demanding further exploration despite all efforts to link writing and literature. One way to connect literature and writing is Rosenblatt’s ( 1938 ) reader-response approach that Belcher and Hirvela refer to it as one way, which can reduce the problems of using literature in the classrooms. Spack ( 1985 ) also maintains that in writing classes reading literature encourages learners “to make inferences, to formulate their ideas, and to look closely at a text for evidence to support generalizations” which leads them to think critically (p. 721).

Furthermore, Shafer ( 2013 , p. 39) maintains that if teachers decide to use literature in writing classes, “it should be approached in an inclusive, reader response method so that students have the opportunity to transact with the text and shape it.”

The reader response approach employs literary works in the English language classes and focuses on the reader rather than the text or as Rosenblatt ( 1976 ) conceptualizes, considers a creative role for the reader (p. 42). Therefore, it gives value to the reader as the driving force who can create meaning (Grossman, 2001 ) and provide new interpretations to a literary text. As Smagorinsky ( 2002 ) argues, in the reader-response approach, learners enrich the topic under scrutiny by their “previous experiences” and thus establish an “understanding of themselves, the literature and one another” (p.25). A critical characteristic of the reader-response approach is perspective-taking. According to Chi ( 1999 ), literary texts are not for teaching form and structure; preferably, they are a conduit of encouraging learners to read critically, to extract their understanding of a text, and as Rosenblatt ( 1985 ) maintains, to organize their thoughts and feelings when responding to them. The unique characteristic of the reader response approach, which values the readers’ interpretations of a text due to emotions, concerns, life experiences, and knowledge they have can connect literature and writing.

A review of the related literature shows that the approach has been employed in English language classes to examine its effect on learners’ understanding of literature as well as on developing linguistic and non-linguistic features. For example, Carlisle ( 2000 ) studied the effect of creating reading logs on the participants’ reading a novel while Gonzalez and Courtland ( 2009 ) explored how by the manipulation of the reader-response approach for reading a Spanish novel, the participants could learn the language, appreciate the cultural values, and improve their metacognitive reading strategies. Dhanapal ( 2010 ) reported that using reader-response could enhance the participants’ critical and creative thinking skills. Also, Khatib ( 2011 ) used the approach for enhancing EFL learners’ vocabulary knowledge and reading skills though she could not find a statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups. In another study, Iskhak ( 2015 ) reported that the participants’ personality characteristics and L2 speaking and writing improved as the result of participating in reading a novel and responding to it.

The researcher was particularly interested in examining how the participants’ mental processes after reading and reflecting on literary texts could help them in writing. She used group discussions and personal reflective writings as stimulators of thinking ability that seem to be responsible for creating good-quality essays. Thus, the reader-response was viewed as a starting point that could stimulate reflection, and if scaffolded by group discussions and writing tasks, it could enhance the elements of thinking necessary for providing argumentation in writing. Moreover, the classroom procedure was intended to help the participants adjust their essays to the rules (related to mono-topicality) of English writing. Multiple forms of data collection were employed for the present qualitative case study whose purpose was to describe a “phenomenon and conceptualize it” (Gall, Gall, & Borg, 2003 , p. 439).

Contrary to what is suggested by scholars regarding the occurrence of qualitative studies in natural settings (e.g., Creswell, 2013 ; Dornyei, 2007 ), this research was conducted in a classroom. The justification, according to Gall et al. ( 2003 , p. 438), is that in occasions where “fieldwork is not done, the goal is to learn about the phenomenon from the perspective of those in the field.” Thus, the following research questions were proposed to fulfill the objectives of the study:

RQ1 : How does the reader-response approach operate in writing argumentative essays?

RQ2 : How do the participants proceed with writing argumentative essays after reading short stories?

RQ3 : How do the participants’ essays before and after the treatment compare?

Participants

Participants were five Iranian EFL learners who participated in a private writing class. Table 1 shows their demographic information. As the table shows, they had studied English for several years and had started learning English from childhood.

Meanwhile, all of them were attending language classes in different institutes in Tehran at the upper-intermediate level. However, they asserted that they needed individual instruction in the writing skill. The participants did not have any significant academic encounter with the English literature before the study.

The teacher was the researcher of the study. Her B.A. degree in English language and literature, the literature courses she had passed as the requirements of her M.A. and Ph.D. in Applied Linguistics had provided her with a background in English literature. Additionally, teaching literature courses such as Oral Reproduction of Short Stories, Introduction to English Literature, and English Prose and Poetry in the university where she was a faculty member, had drenched her with the necessary knowledge to instruct the classes. Besides, teaching writing courses for more than 15 years, and publishing papers related to the writing skill gave her insight regarding teaching the skill.

Data collection

The researcher triangulated the study by different types of data obtained from several sources. First, an English proficiency test consisting of 20 vocabulary items, 30 structures, and three reading passages each followed by five comprehension questions extracted from TOEFL Test Preparation Kit ( 1995 ) was used to ensure the participants’ homogeneity regarding the English proficiency level. The reason for using an old version of the test was to control the practice effect, as the participants were familiar with more recent versions.

Also, the participants were expected to write an essay on “ Is capital punishment justified?” as both the pre and post writing tests in 250–300 words which could help the researcher have a clear understanding of their writing ability before and after the treatment. However, the researcher did not intend to go through any inferential statistics, as the study was a qualitative one.

To select a controversial topic of writing which could persuade the student-writers to provide argumentations, the researcher prepared a list of ten topics and asked ten colleagues and ten students to mark the most challenging one. Thirteen of the respondents selected the topic related to capital punishment. Some of the other topics were, “Do we have the right to kill animals ?” “ Education must not be free for everyon e,” and “ Internet access must be limited. ”

A writing rubric (Allen, 2009 ) was used for correcting the essays (Additional file 1 ). The rubric considers four levels (No/Limited Proficiency, Some Proficiency, Proficiency, High Proficiency) across five characteristics of originality, clarity, organization, support, and documentation. The participants’ scores were obtained by adding the points for each level of writing, ranging from 1 for No/Limited Proficiency to 4 for High Proficiency. The researcher and a colleague of hers who had also taught writing classes for about 10 years rated the essays. They negotiated on the merits and shortcomings of each essay and finally agreed on a quality mentioned in the rubric.

The next source of information was students’ reflective responses written after reading the short stories. In these responses, the participants attempted to relate the stories to their personal experiences or write about their feelings, thoughts, and attitudes toward the stories.

Think-aloud protocols were also used as an instrument for data collection. Although according to Bowles ( 2010 , p. 3), “requiring participants to think aloud while they perform a task may affect the task performance and therefore not be a true reflection of normal cognitive processing,” its positive outcome cannot be denied. As Hyland ( 2009 , p. 147) sustains, despite criticisms against think-aloud protocols, they are used extensively in different studies since “the alternative, deducing cognitive processes from observations of behaviour, is less reliable.” Thus, the participants were trained on thinking aloud before the data collection, and then during the study, they were encouraged to report their thought processes while engaged in writing.

Another tool for data collection was a semi-structured interview conducted after completing the circle of reading each short story. The interviews were recorded and analyzed to enable the researcher to explore the participants’ learning experience (Additional file 2 ).

The researcher selected five thought-provoking short stories of high literary merits to initiate class discussions and elicit responses from the participants. The stories were The Lottery (Jackson, 1948 ), The Rocking Horse Winner (Lawrence, 1926 ), The Storm (Malmar, 1944 ), The Last Leaf (Henry, 1907 ), and Clay (Joyce, 1914 ).

Furthermore, the researcher prepared some tasks based on each story to help the participants practice writing and thinking skills (Additional file 3 ). Section A of the tasks required the respondents to organize the sentences according to the sequence of occurrence in the story. Section B asked the students to complete some incomplete sentences with “because,” and Section C consisted of “ WH” questions. Both sections required the learners to think and reason. The participants were expected to complete the three-step tasks after reading each story.

The classes were held in fall 2018. The instruction took 20 sessions, each week, two sessions, and each session 2 h. Before the advancement of the study, the researcher explained the classroom procedure and obtained the participants’ consent regarding the teaching/learning procedure. Then they took the general proficiency and the writing tests to provide the researcher with an estimation of their English language level. In the three subsequent sessions, the researcher gave instructions on English essay writing and discussed the characteristics of an excellent essay. The samples of high-quality and weak essays presented during the instruction could elucidate the characteristics of argumentative essays. The first short story ( The Lottery ) was introduced in session four, which the learners were asked to read before the succeeding session.

In class, first, the researcher asked the participants to take turns and read the story aloud because as Gajdusek ( 1988 ) argues, “many clues to meaning are conveyed by intonation and other expressive devices available” (p. 238). Then some time was allocated to the reflection on the story that could lead to the intellectual involvement of the participants. In the next step, the class followed group discussions through which the learners struggled to verbalize their responses to the story. In this stage, the researcher encouraged talking about viewpoints and emotional states that the learners experienced after reading the story. Following Sumara ( 1995 ), the researcher took part in the discussions to show some of her understanding from the text, although she tried to be concise and give most of the discussion time to the learners. Through comments and questions, the researcher intended to encourage the participants to share ideas with classmates.

After the group discussion, which usually took about 45 min, based on the reader-response treatment, the learners wrote about their feelings and views without trying to stick to the rules of writing such as organization, punctuation, subject-verb agreement, and the like.

In the subsequent session, the researcher asked the student-writers to refer to their notes before doing the tasks. The tasks had a twofold purpose. First, they aimed to help learners organize their thoughts by reflecting on the story. Second, they enabled the learners to relate the stories to their personal experience and understanding. Once the participants completed the tasks, they were invited to agree about a topic more or less related to the theme of the story and start writing a five-paragraph essay. The researcher corrected the essays based on the writing rubric and returned them in the next session (Additional file 1 ). While the learners were involved in writing, each session, the researcher asked two or three of them to participate in the think-aloud process.

The third session was devoted to interviewing the learners. Each interview took about five to 10 min. The participants started re-writing their essays based on the corrections after the researcher explained about their mistakes and errors. Table 2 summarizes the order of presenting the stories and topics attempted in the class.

Table 3 demonstrates the classroom procedure in each session.

The researcher used the data derived from group discussions, reader-responses, think-aloud protocols, and interviews to answer the first and second research questions. For answering the third research question, the quality of the essays written before and after the treatment was compared.

Group discussions

Before reading the first story, the participants were cynical regarding the usefulness of reading literature. They believed that the texts were too complicated; reading them was time-consuming and required skills different from the ones necessary for writing. However, after the first group discussion on The Lottery , they were excited. Some of the comments were:

“ The discussions help us express the feelings and emotions [which were] there inside but couldn’t find their way out, ” “ Classes lower my anxiety,” and “While reading, I felt I was in a different world forgetting [my problems].”

The discussions began with some challenging questions written by the researcher on the board. As the classes proceeded, the participants showed interest in the activity by listening to classmates, expressing viewpoints, and providing arguments. After reading the Lottery , Nima said:

“ I was shocked when I read the story, the name of the story implies something good, but something awful happened … how amazing! ”

Maryam added:

“ It’s like life when you expect good things and bad things happen .”

Azin looked at the story from a different perspective:

“ How selfish people can be, exactly like what happens nowadays, we keep silence until something injures [us].”

And Melika believed:

“ Others’ miseries are a relief for us … how cruel human beings can be, and this is true even in today’s civilized world.”

When reading Clay , Nima said:

“ I was expecting something unusual to happen, something which needs thinking and interpreting , I was sure clay implied something…not expecting .”

Ali asserted that he could understand literature better, could go beyond words, think more profound, and analyze the events in the short stories. The group discussions showed that the participants connected themselves with the stories and characters, and although they were unfamiliar with the English literature, they started appreciating the literary values of the stories.

Another advantage of the classes was the mental relief they caused as reflected in Melika’s words:

“ It is interesting to read about people who do not worry about the messages on their cell phones!”

One crucial point in the class discussions was the improvement of vocabulary knowledge. The participants sought to use words and phrases they had encountered in the stories. They asserted that reading and discussing literary texts helped them remember words with more ease. Besides, the discussions gave them self-confidence in self-expression and overflow of feelings. Maryam emphasized the role of group discussions in shaping her thoughts:

“ They [group discussions] were constructive; made me think and get familiar with others’ views … sometimes you think there is only one way of looking at something … then you find out … issues which you had never thought about before .”

Sharing ideas gave learners the courage to reason, evaluate, justify, agree, and disagree. Expressing agreement and disagreement regarding an issue was an achievement for the learners because it helped them while writing essays.

Another advantage of the group discussions was that they enhanced attention to the details. As the classes proceeded, the participants were conscious of the details mentioned in the stories, and tried to relate them to the plot and characters of the story and tried to infer the meaning they implied. For example, Maryam said:

“ The storm has a double meaning; it refers both to the weather and her inner feelings.”

Melika mentioned:

“ Drooped shoulders show how anxious she was .”

Azin referred to a sentence from the story (But now, alone and with the storm trying to batter its way in, she found it frightening to be so far away from other people) and stated :

“The storm inside her was destroying the image she had built of her life...now she was trying to find someone to stick … watching the imaginary heaven breaking … into pieces.”

The following excerpt is an example from group discussions on Clay to show how the class progressed in answering the leading question: “ How do you feel about Maria ?”

Azin: I think she is an unmarried middle-aged woman … I sympathize with her. Maryam: Why? … … .. why sympathize ? Azin: Because she is not married. Maryam: Is not being married a reason for sympathizing with someone? Melika: No, not marriage … … but loneliness … .. she was very lonely . Ali: Melika is right. Loneliness is too bothering, especially for the old; old age brings worries for people. I always try to show my concern for the elderly. Nima: Good thing to do . But I think some sort of sadness was around her which made me very sad, too…the writer implied kind of nothingness … … after so many years working she had nothing to be happy for. Azin: I do not agree, why nothingness … such is life, 1 day we come [to this world], and 1 day we must go … .this tells us to enjoy life. Maryam: Azin is right. Life is a blessing; we should enjoy every minute of it. Teacher: Let’s try to conclude. Nima … .please, the keywords were loneliness, sadness, marriage, life, and happiness.

Reader-responses

The responses promoted the participants’ focus on the stories. They pointed toward their inner feelings, judgments, preferences, and thoughts about the themes of the stories. They had addressed themselves and the characters and had put themselves in their place. They had used both questions and statements in the responses. Two responses to the Rocking Horse Winner by Maryam and Azin are as follows:

“She had bonny children, yet she felt they had been thrust upon her, and she could not love them.” There are hundreds of people who can’t have children, you are lucky...Sometimes … we cannot realize how lucky we are, I am most [ly] like that … I should not be !”

“ … they had discreet servants, and felt themselves superior to anyone in the neighbourhood.” Feeling you are superior can destroy you … this is what kills human beings. When you think it is your right to have everything and … you forget others … sometimes others deserve but don’t have as much as you .”

Overall, the responses facilitated remembering the sequence of events in the stories. The tasks, together with group discussions, helped the participants organize their thoughts, and thus avoid recursive or cyclical writing. For example, on the first topic, “ The negative role of traditions in our life ,” Melika wrote:

“ Traditions can have both positive and negative roles in our lives. The negative role of traditions is most of the time more dominant though positive roles can be mentioned, as well. The negative role of traditions can cause ignorance, unawareness, and cruelty. Traditions can change the direction of people’s lives and force them to choose ways that are not appropriate. However, traditions can bring about good things, too.”

The writing is recursive as it repeats the idea of negative and positive aspects continuously. However, comparing Melika’s first writing with the last one, “ Superstitions should be abandoned ,” shows her improvement in expressing her idea clearly:

Superstitions are the result of [a] human being’s ignorance. People resort to them when they cannot find solutions to their problems or are not strong enough to face the disasters they encounter.

Additionally, the tasks enhanced reasoning and looking for evidence among the learners. For instance, Ali’s writing on the first topic not only shows his tendency to repeat the same idea but also reveals his lack of reasoning and thus relying on “educated people” and “scholars” to prove himself:

“Educated people never show a tendency toward traditions. Scholars believe that traditions are not scientific, and in today’s world, we must pay attention to scientific findings to solve our problems. The scientific developments help us to be able to live in this modern world.”

However, his introductory paragraph on “the role of motivation in life” showed some argumentation in developing his writing:

“ Motivation seems to have a positive role in our life and can help us to do different activities with less effort and more energy. For example, when we are interested in completing a project, we do not feel tired, but we think about the sense of achievement we will gain .”

Think-aloud protocols

As stated above, think-aloud protocols mainly focused on the participants’ thinking processes while they were engaged in writing. In each writing session, two or three learners participated in the think-aloud procedure. The researcher sat beside one of the participants who had agreed to take part in the thinking protocol. S/he explained the strategies s/he was using or accounted for his/her thought processes. All participants’ voices were recorded by their permission and transcribed for further analysis.

The analyses of the protocols showed that all participants first tried to take a perspective regarding the topic of the writing. The most frequent strategy was self-questioning. They first wrote questions and then answered them. Some questions were, “ What do I think about the topic? Why do I think so? What are my reasons? What is the evidence to support my idea? Are my reasons logical ?” Moreover, they reported that they used mind maps and outlines before beginning to write. Another strategy was using the phrases and words they had extracted and memorized from the texts that, as they asserted, could help them start writing.

Developing an inner dialogue before writing was another strategy used by the participants. Maryam said:

“ I … talk to myself and meanwhile try to write all of the sentences I exchange with myself during the dialogue. Then I organize them .”

Translating from L1, trying to write for an audience and drafting were other strategies used by the participants.

An interesting point mentioned by Maryam, Ali, and Nima was thinking about the stories before writing:

“ … in this way, writing becomes easier .” “ Discovering what you really think about a subject is difficult … I cannot make a decision … but the story is really helpful … it gives direction to my thoughts. ” “ I don’t know how to start my essay, that is why I am trying to review the story in my mind … .”

During the interviews, the participants talked about their learning experience. Their answers to the first interview question showed that they viewed writing a troublesome and challenging activity that needed expertise beyond general proficiency in English. They believed that for effective writing, besides knowledge of the language, learners should learn how to organize their thought processes and transfer them to words. They believed that the classroom procedure gave direction to their thoughts and enabled them to think and write systematically. Some of the advantages of reading literature, as they mentioned, are as follows:

“The use of technology makes me tired; people are always checking something in their cell phones; human relations are weakening … I think reading and sharing ideas is a relief .”

“ Freeing myself from my problems was great … reading stories gave me something different from the routines of life .”

“ The class gave me a reason to talk … something I miss nowadays … I am fed up with reading and writing in the [social network] .”

“ I hate traditional classes they do not give me space to be myself and talk about something different from casual things .”

“ … it was the first time I enjoyed writing because I had ideas to write about. I could [let] myself go.”

Regarding the second question, the learners believed that perspective-taking and organizing ideas were the most demanding tasks while they also maintained that controlling both content and form was difficult. Melika stated:

“ if it were not for grammar, I would have been more comfortable to express myself .”

Moreover, three of the participants (Maryam, Ali, and Nima) pointed to group discussions and mentioned that in the very first sessions, it was difficult for them to express their viewpoints regarding the topic of the discussions, but as the classes continued, they gained the necessary self-confidence. Maryam stated:

“ As the classes started, I was [worried] about my ideas to be irrelevant … I could have seemed funny … but little by little I gained courage to speak out .”

The flow of ideas was considered the most encouraging characteristic of the class (third interview question) for all of the participants. They believed that the short stories were excellent sources of ideas, and responding to them stimulated looking at the themes of the stories from a different perspective. Additionally, listening to classmates was considered encouraging because their opinions inspired confidence, thinking, and appreciation for literature.