An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Trending Articles

- Plasma interleukin-41 serves as a potential diagnostic biomarker for Kawasaki disease. Cai X, et al. Microvasc Res. 2023. PMID: 36682486

- A gut-derived hormone regulates cholesterol metabolism. Hu X, et al. Cell. 2024. PMID: 38503280

- Safety and efficacy of givinostat in boys with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (EPIDYS): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Mercuri E, et al. Lancet Neurol. 2024. PMID: 38508835 Clinical Trial.

- Global, regional, and national burden of disorders affecting the nervous system, 1990-2021: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. GBD 2021 Nervous System Disorders Collaborators. Lancet Neurol. 2024. PMID: 38493795

- Global fertility in 204 countries and territories, 1950-2021, with forecasts to 2100: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. GBD 2021 Fertility and Forecasting Collaborators. Lancet. 2024. PMID: 38521087

Latest Literature

- Am Heart J (1)

- Am J Med (2)

- Arch Phys Med Rehabil (3)

- Cell Metab (1)

- Gastroenterology (3)

- J Am Acad Dermatol (3)

- J Biol Chem (1)

- Lancet (16)

- Nat Commun (32)

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Harvard Library

- Research Guides

- Faculty of Arts & Sciences Libraries

- Identifying Articles

- PubMed at Harvard

- Searching in PubMed

- My NCBI in PubMed

- Utilizing Search Results

- Scenarios in PubMed

Primary Research Article

Review article.

Identifying and creating an APA style citation for your bibliography:

- Author initials are separated by a period

- Multiple authors are separated by commas and an ampersand (&)

- Title format rules change depending on what is referenced

- Double check them for accuracy

Identifying and creating an APA style in-text citation:

- eg. (Smith, 2022) or (Smith & Stevens, 2022)

The structure of this changes depending on whether a direct quote or parenthetical used:

Direct Quote: the citation must follow the quote directly and contain a page number after the date

eg. (Smith, 2022, p.21)

Parenthetical: the page number is not needed

For more information, take a look at Harvard Library's Citation Styles guide !

A primary research article typically contains the following section headings:

"Methods"/"Materials and Methods"/"Experimental Methods"(different journals title this section in different ways)

"Results"

"Discussion"

If you skim the article, you should find additional evidence that an experiment was conducted by the authors themselves.

Primary research articles provide a background on their subject by summarizing previously conducted research, this typically occurs only in the Introduction section of the article.

Review articles do not report new experiments. Rather, they attempt to provide a thorough review of a specific subject by assessing either all or the best available scholarly literature on that topic.

Ways to identify a review article:

- Author(s) summarize and analyze previously published research

- May focus on a specific research question, comparing and contrasting previously published research

- Overview all of the research on a particular topic

- Does not contain "methods" or "results" type sections

- << Previous: Scenarios in PubMed

- Last Updated: Oct 3, 2023 4:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/PubMed

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

- Books, eBooks & Articles

- Databases A-Z

- Primary Sources

- E-Audiobooks

- Videos & Images

- Online Videos

- Images & Artwork

- More resources

- Research Guides

- Library Instruction

- Request Research Guide

- Interlibrary Loan

- Books on Reserve

- Research Assistance

- Writing Lab

- Online Tutoring

- Group Study Sessions

- Turabian/Chicago

- Other Citing Styles

Service Alert

Finding Primary Articles in PubMed: Home

- APA Citations

Finding Primary Articles in PubMed

From the library homepage -- library.surry.edu (opens in new window) -- click on Find Articles .

Click on the letter P or scroll through the list until you see PubMed . To limit to full text articles, click on the PubMed Central link in the PubMed description.

Type in a search for your topic. Press Enter or click the Search button.

You will retrieve a list of articles. To limit to primary research articles, click on Clinical Trial or click More to select other type of trials and original research studies.

You may also limit your article results to Free full text either on the left or you can scan below the article results for Free Article or Free PMC Article .

If the article is available for free, you will see a link to access the article in the upper right of the screen. If you can't find the article text, email Alan Unsworth, Research Librarian , to see if the article may be obtained .

- Next: APA Citations >>

- Last Updated: Nov 9, 2023 2:07 PM

- URL: https://library.surry.edu/pubmed

Literature Searching

In this guide.

- Introduction

- Steps for searching the literature in PubMed

- Step 1 - Formulate a search question

- Step 2- Identify primary concepts and gather synonyms

- Step 3 - Locate subject headings (MeSH)

- Step 4 - Combine concepts using Boolean operators

- Step 5 - Refine search terms and search in PubMed

- Step 6 - Apply limits

Steps for Searching the Literature

Searching is an iterative process and often requires re-evaluation and testing by adding or changing keywords and the ways they relate to each other. To guide your search development, you can follow the search steps below. For more information on each step, navigate to its matching tab on the right menu.

1. Formulate a clear, well-defined, answerable search question

Generally, the basic literature search process begins with formulating a clear, well-defined research question. Asking the right research question is essential to creating an effective search. Your research question(s) must be well-defined and answerable. If the question is too broad, your search will yield more information than you can possibly look through.

2. Identify primary concepts and gather synonyms

Your research question will also help identify the primary search concepts. This will allow you to think about how you want the concepts to relate to each other. Since different authors use different terminology to refer to the same concept, you will need to gather synonyms and all the ways authors might express them. However, it is important to balance the terms so that the synonyms do not go beyond the scope of how you've defined them.

3. Locate subject headings (MeSH)

Subject databases like PubMed use 'controlled vocabularies' made up of subject headings that are preassigned to indexed articles that share a similar topic. These subject headings are organized hierarchically within a family tree of broader and narrower concepts. In PubMed and MEDLINE, the subject headings are called Medical Subject Headings (MeSH). By including MeSH terms in your search, you will not have to think about word variations, word endings, plural or singular forms, or synonyms. Some topics or concepts may even have more than one appropriate MeSH term. There are also times when a topic or concept may not have a MeSH term.

4. Combine concepts using Boolean operators AND/OR

Once you have identified your search concepts, synonyms, and MeSH terms, you'll need to put them together using nesting and Boolean operators (e.g. AND, OR, NOT). Nesting uses parentheses to put search terms into groups. Boolean operators are used to combine similar and different concepts into one query.

5. Refine search terms and search in PubMed

There are various database search tactics you can use, such as field tags to limit the search to certain fields, quotation marks for phrase searching, and proximity operators to search a number of spaces between terms to refine your search terms. The constructed search string is ready to be pasted into PubMed.

6. Apply limits (optional)

If you're getting too many results, you can further refine your search results by using limits on the left box of the results page. Limits allow you to narrow your search by a number of facets such as year, journal name, article type, language, age, etc.

Depending on the nature of the literature review, the complexity and comprehensiveness of the search strategies and the choice of databases can be different. Please contact the Lane Librarians if you have any questions.

The type of information you gather is influenced by the type of information source or database you select to search. Bibliographic databases contain references to published literature, such as journal articles, conference abstracts, books, reports, government and legal publications, and patents. Literature reviews typically synthesis indexed, peer-reviewed articles (i.e. works that generally represent the latest original research and have undergone rigorous expert screening before publication), and gray literature (i.e. materials not formally published by commercial publishers or peer-reviewed journals). PubMed offers a breadth of health sciences literature and is a good starting point to locate journal articles.

What is PubMed?

PubMed is a free search engine accessing primarily the MEDLINE database of references and abstracts on life sciences and biomedical topics. Available to the public online since 1996, PubMed was developed and is maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) , at the U.S. National Library of Medicine (NLM) , located at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) .

MEDLINE is the National Library of Medicine’s (NLM) premier bibliographic database that contains more than 27 million references to journal articles from more than 5,200 worldwide journals in life sciences with a concentration on biomedicine. The Literature Selection Technica Review Committee (LSTRC) reviews and selects journals for MEDLINE based on the research quality and impact of the journals. A distinctive feature of MEDLINE is that the records are indexed with NLM Medical Subject Headings (MeSH).

PubMed also contains citations for PubMed Central (PMC) articles. PMC is a full-text archive that includes articles from journals reviewed and selected by NLM for archiving (current and historical), as well as individual articles collected for archiving in compliance with funder policies. PubMed allows users to search keywords in the bibliographic data, but not the full text of the PMC articles.

How to Access PubMed?

To access PubMed, go to the Lane Library homepage and click PubMed in "Top Resources" on the left. This PubMed link is coded with Find Fulltext @ Lane Library Stanford that links you to Lane's full-text articles online.

- << Previous: Introduction

- Next: Step 1 - Formulate a search question >>

- Last Updated: Jan 9, 2024 10:30 AM

- URL: https://laneguides.stanford.edu/LitSearch

Identifying Primary and Secondary Research Articles

- Primary and Secondary

Primary Research Articles

Primary research articles report on a single study. In the health sciences, primary research articles generally describe the following aspects of the study:

- The study's hypothesis or research question

- Some articles will include information on how participants were recruited or identified, as well as additional information about participants' sex, age, or race/ethnicity

- A "methods" or "methodology" section that describes how the study was performed and what the researchers did

- Results and conclusion section

Secondary Research Articles

Review articles are the most common type of secondary research article in the health sciences. A review article is a summary of previously published research on a topic. Authors who are writing a review article will search databases for previously completed research and summarize or synthesize those articles, as opposed to recruiting participants and performing a new research study.

Specific types of review articles include:

- Systematic Reviews

- Meta-Analysis

- Narrative Reviews

- Integrative Reviews

- Literature Reviews

Review articles often report on the following:

- The hypothesis, research question, or review topic

- Databases searched-- authors should clearly describe where and how they searched for the research included in their reviews

- Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis should provide detailed information on the databases searched and the search strategy the authors used.Selection criteria-- the researchers should describe how they decided which articles to include

- A critical appraisal or evaluation of the quality of the articles included (most frequently included in systematic reviews and meta-analysis)

- Discussion, results, and conclusions

Determining Primary versus Secondary Using the Database Abstract

Information found in PubMed, CINAHL, Scopus, and other databases can help you determine whether the article you're looking at is primary or secondary.

Primary research article abstract

- Note that in the "Objectives" field, the authors describe their single, individual study.

- In the materials and methods section, they describe the number of patients included in the study and how those patients were divided into groups.

- These are all clues that help us determine this abstract is describing is a single, primary research article, as opposed to a literature review.

- Primary Article Abstract

Secondary research/review article abstract

- Note that the words "systematic review" and "meta-analysis" appear in the title of the article

- The objectives field also includes the term "meta-analysis" (a common type of literature review in the health sciences)

- The "Data Source" section includes a list of databases searched

- The "Study Selection" section describes the selection criteria

- These are all clues that help us determine that this abstract is describing a review article, as opposed to a single, primary research article.

- Secondary Research Article

- Primary vs. Secondary Worksheet

Full Text Challenge

Can you determine if the following articles are primary or secondary?

- Last Updated: Feb 17, 2024 5:25 PM

- URL: https://library.usfca.edu/primary-secondary

2130 Fulton Street San Francisco, CA 94117-1080 415-422-5555

- Facebook (link is external)

- Instagram (link is external)

- Twitter (link is external)

- YouTube (link is external)

- Consumer Information

- Privacy Statement

- Web Accessibility

Copyright © 2022 University of San Francisco

Finding Primary Research Articles in the Sciences: Home

- Advanced Search-Databases

- Primary vs. Secondary

- Analyzing a Primary Research Article

- MLA, APA, and Chicago Style

This guide goes over how to find and analyze primary research articles in the sciences (e.g. nutrition, health sciences and nursing, biology, chemistry, physics, sociology, psychology). In addition, the guide explains how to tell the difference between a primary source and a secondary source in scientific subject areas.

If you are looking for how to find primary sources in the humanities and social sciences, such as direct experience accounts in newspapers, diaries, artwork and so forth, please see Finding Primary Sources in the Humanities and Social Sciences .

Recommended Databases

To get started, choose one of the databases below. Once you log in, enter your search terms to start looking for primary articles.

- Link to all Polk State College Library databases

Login Required

You must log in to use library databases and eBooks. When prompted to log in, enter your Passport credentials.

If you have trouble, try resetting your Passport pin , sending an email to [email protected] , or calling the Help Desk at 863.292.3652 .

You can also get help from Ask a Librarian .

Search Tips

Keep your search terms simple.

- No need to type full sentences into the database search box. Limit your search to 2-3 words.

- There is no need to type "research article" into the search box.

Use the "Advanced Search" feature of the database.

- This will allow you to limit your search to only peer reviewed articles or a certain time frame (for example: 2013 or later).

- Click the red tab above for tips on advanced search strategies .

Re-read the assignment guidelines often

- Does this article satisfy the scope of the assignment (e.g. a study focused on nutrition)?

- Does it meet the criteria for the assignment (e.g. an original research article)?

Not finding what you are looking for?

- Ask a Librarian!

Search and Find a Primary Research Article

Are you looking for a primary research journal article if so, that is an article that reports on the results of an original research study conducted by the authors themselves. .

You can use the library's databases to search for primary research articles. A research article will almost always be published in a peer-reviewed journal. Therefore, it is a good idea to limit your results to peer-reviewed articles. Click on the Advanced Search-Databases tab at the top of this guide for instructions.

The following is _not_ primary research:

Review articles are studies that arrive at conclusions after looking over other studies. Therefore, review articles are not primary (think "first") research. There are a variety of review articles, including:

- Literature Reviews

- Systematic Reviews

- Meta-Analyses

- Scoping Reviews

- Topical Reviews

- A review/assessment of the evidence

Having trouble? Look for a method section within the article. If the method section includes the process used to conduct the research, how the data was gathered and analyzed and any limitations or ethical concerns to the study, then it is most likely a primary research article. For example: a research article will describe the number of people (e.g. 175 adults with celiac disease) who participated in the study and who were used to collect data.

If the method section describes how the authors found articles on a topic using search terms or databases , then it is mostly likely a secondary review article and not primary research. If there is no method section, it is not a primary research article.

Other sections in a journal:

Your search may yield these items, too. You can skip these because they are not full write-ups of research:

- Conference Proceedings

- Symposium Publications

Example of a primary research article found in the Library's Academic Search Complete database : (these authors conducted an original research study)

- Lumia et al. (2015) Lumia, M., Takkinen, H., Luukkainen, P., Kaila, M., Lehtinen, J. S., Nwaru, B. I., Tuokkola, J., Niemelä, O., Haapala, A., Ilonen, J., Simell, O., Knip, M., Veijola, R., & Virtanen, S. M. (2015). Food consumption and risk of childhood asthma. Pediatric Allergy & Immunology, 26(8), 789–796. https://doi.org/10.1111/pai.12352

Example of a secondary article found in the Library's Academic Search Complete database : (these authors are reviewing the work of other authors)

- Rachmah et al. (2022) Rachmah, Q., Martiana, T., Mulyono, Paskarini, I., Dwiyanti, E., Widajati, N., Ernawati, M., Ardyanto, Y. D., Tualeka, A. R., Haqi, D. N., Arini, S. Y., & Alayyannur, P. A. (2022). The effectiveness of nutrition and health intervention in workplace setting: A systematic review. Journal of Public Health Research, 11(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2021.2312

How do I know if this article is primary?

You've found an article in the library databases but how do you know if it's primary .

Look for these sections: (terminology may vary)

- abstract - summarizes paper in one paragraph, states the purpose of the study

- methods - explaining how the experiment was conducted (note: if the method section discusses how a search was conducted that is _not_ primary research)

- results - detailing what happened and providing raw data sets (often as tables or graphs)

- conclusions - connecting the results with theories and other research

- references - to previous research or theories that influenced the research

Scan the article you found to see if it includes the sections above. You don't have to read the full article (yet). Look for the clues highlighted in the images below.

Questions? Use Ask a Librarian

- Next: Advanced Search-Databases >>

- Last Updated: Feb 19, 2024 11:55 AM

- URL: https://libguides.polk.edu/primaryresearch

Polk State College is committed to equal access/equal opportunity in its programs, activities, and employment. For additional information, visit polk.edu/compliance .

- University of Michigan Library

- Research Guides

Epidemiology

- Searching PubMed

- Creating a Well-Focused Question

- PubMed - Article Abstract Page

- Searching Other Databases - Embase

- Searching Other Databases - Web of Science

- Literature Reviews This link opens in a new window

- Citation Management

- Evaluating Sources

- Statistical Sources

- Data Visualization

- Tests & Measurement Instruments This link opens in a new window

- Citation Management Programs This link opens in a new window

- Funding Sources for SPH Graduate Students This link opens in a new window

- Research Funding & Grants This link opens in a new window

- National Institutes of Health Public Access Policy (NIHPAP) This link opens in a new window

Why Search PubMed?

PubMed is the free interface for the premier biomedical database, MEDLINE. It was created & is maintained by the National Library of Medicine. PubMed contains both primary & secondary literature. Because it's a free to access, you can use it even when you leave the University of Michigan.

Articles in PubMed are indexed by MeSH ( Me dical S ubject H eadings), terms that have specific definitions within the database & help you to create more focused searches.

Running a Search

Search Results

Your results are listed on the Search Results page.

You can see that there are many results, including some that are not related to the question.

Search Tip - "Search Details"

What if your search results are not quite what you expected or they seem really off-base? On the Advanced page (link right below the search bar), check Search Details , to see how PubMed "translated" your search.

If at least one term for each concept in your search doesn't map to a MeSH term, you should rethink your search terms or contact the library for help.

Look at how some terms were "translated," for example, dietary intake mapped to eating . This is why the search results are so far off topic. We'll need to revise the search.

Revising Your Search

Putting dietary intake and food intake in quotation marks

( "dietary intake" OR "food intake") AND (dairy products OR milk OR cheese OR yogurt)

will restrict this part of the search to those phrases. The phrases won't map to MeSH terms, but may provide a more focused set of results.

And that's exactly what happens.

Because there are still so many results, add United States to the search:

("dietary intake" OR "food intake") AND (dairy products OR milk OR cheese OR yogurt) AND United States

What's on this page

Choose from this list, or scroll down: Why Search PubMed? ; Running a Search ; Search Results ; Revising Your Search ; Focusing Your Search with Filters ; Search Tip - Keeping Recent Articles in Your Search ; and Search Tip - "Search Details" .

Search Tip - Keeping Recent Articles in Your Search

To be sure that you're seeing the most recent articles on your topic in PubMed, change the default (Best Match) to Most Recent.

Focusing Your Search with Filters

F ilters , which can be found on the left side of the Search Results page, can help you focus your search appropriately. Categories include Article types , Publication dates , Species , Languages , & Ages .

- Two filters that are almost always useful are Species / Humans (unless you're looking specifically for animal research) and Language / English . Ages/ Adolescent will also be useful in this search.

- Some filters are always readily available: Article type, Text Availability (which you should ignore while you're at Michigan), Publication dates. Others you must add to the filters list.

- To add Language , Age , & other types of filters, click on the Additional filters link below the filter list. In the box that opens, select the category of filter & then the specific filters. Click the Show button to make the filters appear on the screen. Next choose the filter(s) you want to add.

- When you apply filters, they appear above your search results. You can clear a filter by clicking the name of the filter or the Clear link, or clear all at the top of the results.

- Remember to clear all filters when you do a new search.

Finally, if you want to see more recent articles, add a date filter. Limiting this search to the last 5 years gives 30 results, a reasonable set of results to look through.

A Guide to Biology: Find Primary Articles

- Find Primary Articles

- Find Books and Background Information

- Literature Reviews

- Citing Biology Sources/Citation Management

Journals List: Do We Have this Journal?

When you have a source with a bibliography, you can see if a particular article from the bibliography is available by looking the journal's name up at the link below. Then you can use the volume and date information to navigate to the article. If we don't have access to that journal, we usually can get it from another library.

- Search the Journals List: Do We Have this Journal?

Biology Journals in Print

These print-format journals all publish primary research and review articles in the field of biology.

American Midland Naturalist Genes and Development (most current year; earlier volumes in PMC) Nature Science Wilson Journal of Ornithology

We also subscribe in print to the following biology-related journals and magazines Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development Environmental Ethics Horticulture (current issue on main floor) Loon Minnesota Birding Minnesota Conservation Volunteer National Wildlife New Scientist (current issue on main floor)

Open Access to Biology Research

When searching PubMed, you can narrow the results to "free full text."

For a single source of open access journal articles in the life sciences, this collection from the National Library of Medicine is hard to beat.

- PubMed Central (digital archive of journal literature) This link opens in a new window Free full text scholarly journal archive of literature in the life and health sciences, managed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information at the National Library of Medicine.

Biology Databases

Often you will hear the phrase "primary articles" when starting biology research, meaning articles written by scientists reporting new research. These typically introduce the research with a review of previous research in the introduction, methodology, results, and discussion and/or conclusion. Journals in biology also publish "review articles" that provide a roundup of recent research on a topic in biology. If you are looking for primary articles or review articles in biology and biomedical topics, these databases will be especially useful.

- Biological Science This link opens in a new window Covers research in all areas of biological science, including animal behavior, biomedicine, zoology, ecology, and others. Coverage is from 1982 to the present. Includes abstracts and citations, as well as access to thousands of full text titles.

- PubMed (citations from MEDLINE and other sources) This link opens in a new window PubMed contains more than 30 million citations and abstracts of biomedical literature. Click the "Find it at Gustavus" button to link to the full text or to make an interlibrary loan request. PubMed was developed and is maintained by the National Institutes of Health.

- Web of Science (Web of Knowledge) This link opens in a new window Science Citation Index Expanded, Social Sciences Citation Index, and Arts & Humanities Citation Index of the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI). Besides indexing a wide range of journals in the sciences, social sciences, and history, this resource allows you to search for articles that cite a specific author or published work. Coverage from 1997 to the present. Click on the "Web of Science" tab to limit your search to one or more specific citation databases.

Annual Reviews

These annual books publish review articles - detailed recaps of research on questions in the field. They are an excellent place to gain a sense of the various approaches to a topic and references to the literature that supports it.

Two series are shelved in the general collection under the following call numbers:

- ADVANCES IN MARINE BIOLOGY v. 1, 1963- (QH 91 .A1 A22)

- ADVANCES IN VIRUS RESEARCH v. 1, 1953- (QR 360 .A3)

Also of interest is WILDLIFE MONOGRAPHS. Current volumes are available online ; volumes from 1956 - 2009 are sheved at QL 1 .W54.

The Annual Reviews series online also includes biology-related review articles.

- Annual Review of Biochemistry

- Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology

- Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics

- Annual Review of Entomology

- Annual Review of Genetics

- Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics

- Annual Review of Immunology

- Annual Review of Neuroscience

Other Science Databases

- AGRICOLA This link opens in a new window Citations and abstracts for agricultural publications from the 15th century to the present, including articles from over 600 periodicals, USDA and state experiment station and extension publications, and selected books. Subjects include animal and veterinary sciences, entomology, plant sciences, food and human nutrition, and earth and environmental sciences. Many records are linked to full-text documents online. A resource of the National Agricultural Library.

- Google Scholar This link opens in a new window This search engine points toward scholarly research rather than all Web-based sources. It is stronger in the sciences than in the humanities, with social sciences somewhere in between. One interesting feature of Google Scholar is that in includes a link to sources that cite a particular item. Not all of the articles in Google Scholar are free; the library can obtain many of them for you through Interlibrary loan.

How Do I Get the Actual Articles?

If there isn't a PDF available, look for a "find it" link. That will check to see if it's available through another of our databases. If no full text is available, it will give you an opportunity to request the article from another library. You will have to log in using your Gustavus username and password. It usually takes a day or two. Look for an email that will explain how to download the PDF.

If you're using Google Scholar, look for either a "find it @ Gustavus" link to the right or a "more" link under the reference you're interested in.

- << Previous: Start

- Next: Find Books and Background Information >>

- Last Updated: Feb 15, 2024 3:49 PM

- URL: https://libguides.gustavus.edu/BIO

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Med Res Methodol

Primary versus secondary source of data in observational studies and heterogeneity in meta-analyses of drug effects: a survey of major medical journals

Guillermo prada-ramallal.

1 Department of Preventive Medicine and Public Health, University of Santiago de Compostela, c/ San Francisco s/n, 15786 Santiago de Compostela, A Coruña, Spain

2 Health Research Institute of Santiago de Compostela (Instituto de Investigación Sanitaria de Santiago de Compostela - IDIS), Clinical University Hospital of Santiago de Compostela, 15706 Santiago de Compostela, Spain

Fatima Roque

3 Research Unit for Inland Development, Polytechnic of Guarda (Unidade de Investigação para o Desenvolvimento do Interior - UDI/IPG), 6300-559 Guarda, Portugal

4 Health Sciences Research Centre, University of Beira Interior (Centro de Investigação em Ciências da Saúde - CICS/UBI), 6200-506 Covilhã, Portugal

Maria Teresa Herdeiro

5 Department of Medical Sciences & Institute for Biomedicine – iBiMED, University of Aveiro, 3810-193 Aveiro, Portugal

6 Higher Polytechnic & University Education Co-operative (Cooperativa de Ensino Superior Politécnico e Universitário - CESPU), Institute for Advanced Research & Training in Health Sciences & Technologies, 4585-116 Gandra, Portugal

Bahi Takkouche

7 Consortium for Biomedical Research in Epidemiology & Public Health (CIBER en Epidemiología y Salud Pública – CIBERESP), Santiago de Compostela, Spain

Adolfo Figueiras

Associated data.

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

The data from individual observational studies included in meta-analyses of drug effects are collected either from ad hoc methods (i.e. “primary data”) or databases that were established for non-research purposes (i.e. “secondary data”). The use of secondary sources may be prone to measurement bias and confounding due to over-the-counter and out-of-pocket drug consumption, or non-adherence to treatment. In fact, it has been noted that failing to consider the origin of the data as a potential cause of heterogeneity may change the conclusions of a meta-analysis. We aimed to assess to what extent the origin of data is explored as a source of heterogeneity in meta-analyses of observational studies.

We searched for meta-analyses of drugs effects published between 2012 and 2018 in general and internal medicine journals with an impact factor > 15. We evaluated, when reported, the type of data source (primary vs secondary) used in the individual observational studies included in each meta-analysis, and the exposure- and outcome-related variables included in sensitivity, subgroup or meta-regression analyses.

We found 217 articles, 23 of which fulfilled our eligibility criteria. Eight meta-analyses (8/23, 34.8%) reported the source of data. Three meta-analyses (3/23, 13.0%) included the method of outcome assessment as a variable in the analysis of heterogeneity, and only one compared and discussed the results considering the different sources of data (primary vs secondary).

Conclusions

In meta-analyses of drug effects published in seven high impact general medicine journals, the origin of the data, either primary or secondary, is underexplored as a source of heterogeneity.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12874-018-0561-3) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Specific research questions are ideally answered through tailor-made studies. Although these ad hoc studies provide more accurate and updated data, designing a completely new project may not represent a feasible strategy [ 1 , 2 ]. On the other hand, clinical and administrative databases used for billing and other fiscal purposes (i.e. “secondary data”) are a valuable resource as an alternative to ad hoc methods (i.e. “primary data”) since it is easier and less costly to reuse the information than collecting it anew [ 3 ]. The potential of secondary automated databases for observational epidemiological studies is widely acknowledged; however, their use is not without challenges, and many quality requirements and methodological pitfalls must be considered [ 4 ].

Meta-analysis represents one of the most valuable tools for assessing drug effects as it may lead to the best evidence possible in epidemiology [ 5 ]. Consequently, its use for making relevant clinical and regulatory decisions on the safety and efficacy of drugs is dramatically increasing [ 6 ]. Existence of heterogeneity in a given meta-analysis is a feature that needs to be carefully described by analyzing the possible factors responsible for generating it [ 7 ]. In this regard, the results of a recent study [ 8 ] show that whether the origin of the data (primary vs secondary) is explored as a potential cause of heterogeneity may change the conclusions of a meta-analysis due to an effect modification [ 9 ]. Thus, considering the source of data as a variable in sensitivity and subgroup analyses, or meta-regression analyses, seems crucial to avoid misleading conclusions in meta-analyses of drug effects.

Given the evidence noted [ 8 , 9 ], we surveyed published meta-analyses in a selection of high-impact journals over a 6-year period, to assess to what extent the origin of the data, either primary or secondary, is explored as a source of heterogeneity in meta-analyses of observational studies.

Meta-analysis selection and data collection process

General and internal medicine journals with an impact factor > 15 according to the Web of Science were included in the survey [ 10 ]. This method has been widely used to assess quality as well as publication trends in medical journals [ 11 – 13 ]. The rationale is that meta-analyses published in high impact journals: (1) are likely to be rigorously performed and reported due to the exhaustive editorial process [ 12 , 14 ]; and, (2) in general, exert a higher influence on medical practice due to the major role played by these journals in the dissemination of the new medical evidence [ 14 , 15 ]. We searched MEDLINE on May 2018 using the search terms “meta-analysis” as publication type and “drug” in any field between January 1, 2012 and May 7, 2018 in the New England Journal of Medicine ( NEJM ), Lancet, Journal of the American Medical Association ( JAMA) , British Medical Journal ( BMJ ), JAMA Internal Medicine (JAMA Intern Med) , Annals of Internal Medicine ( Ann Intern Med ), and Nature Reviews Disease Primers (Nat Rev Dis Primers) .

Two investigators (GP-R, FR) independently assessed publications for eligibility. Abstracts were screened and if deemed potentially relevant, full text articles were retrieved. Articles were excluded if they met any of the following conditions: (1) were not a meta-analysis of published studies, (2) no drug effects were evaluated, (3) only randomized clinical trials were included in the meta-analysis (in order to consider observational studies), (4) less than two observational studies were included in the meta-analysis (since with a single study it would not have been possible to calculate a pooled measure). When a meta-analysis included both observational studies and clinical trials, only observational studies were considered.

A data extraction form was developed previously to extract information from articles. Two investigators (GP-R, FR) independently extracted and recorded the information and resolved discrepancies by referring to the original report. If necessary, a third author (AF) was asked to resolve disagreements between the investigators.

When available we extracted the following data from each eligible meta-analysis: first author, publication year, journal, drug(s) exposure and outcome(s); number of individual studies included in the meta-analysis based on each type of data source used (primary vs secondary), for both exposure and outcome assessment; and exposure- and outcome-related variables included in sensitivity, subgroup or meta-regression analyses. We extracted data directly from the tables, figures, text, and supplementary material of the meta-analyses, not from the individual studies.

Assessment of exposure and outcome

We considered “primary data” the information on drug exposure collected directly by the researchers using interviews –personal or by telephone– or self-administered questionnaires. The origin of the data was also considered primary when objective diagnostic methods were used for the determination of drug exposure (e.g. blood test). “Secondary data” are data that were formerly collected for other purposes than that of the study at hand and that were included in databases on drug prescription (e.g. prescription registers, medical records/charts) and dispensing (e.g. computerized pharmacy records, insurance claims databases). Regarding the outcome assessment, we considered primary data when an objective confirmation is available that endorses them (e.g. confirmed by individual medical ad hoc diagnosis, lab test or imaging results). These criteria are based on those commonly used in the risk assessment of bias for observational studies [ 16 – 19 ].

MEDLINE search results yielded 217 articles from the major general medical journals (3 from NEJM , 46 from Lancet , 26 from JAMA , 85 from BMJ , 19 from JAMA Intern Med, 38 from Ann Intern Med, and 0 from Nat Rev Dis Primers ) (see Fig. Fig.1). 1 ). A total of 194 articles were excluded (see list of excluded articles with reasons for exclusion in Additional file 1 ) leaving 23 articles to be examined [ 20 – 42 ]. General characteristics of the 23 included meta-analyses are outlined in Table Table1 1 .

Flow diagram of literature search results

Characteristics of the 23 included meta-analyses

Abbreviations : AABs antibodies against biologic agents, ACEIs , angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors, Ann Intern Med Annals of Internal Medicine , ARBs angiotensin receptor blockers, BMJ British Medical Journal , DPP-4 Dipeptidyl Peptidase-4, GLP-1 glucagon like peptide-1, JAMA Journal of the American Medical Association , MIC minimum inhibitory concentration, NSAIDs non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, SGLT-2 sodium–glucose cotransporter 2, SSRIs selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors

Source of exposure and outcome data

Table Table2 2 summarizes the evidence regarding the type of data source included in each meta-analysis, according to the information presented in the data extraction tables of the article. The information was evaluated taking the study design into account. Only eight meta-analyses [ 21 , 24 , 26 , 31 , 32 , 34 , 38 , 41 ] reported the source of data, three of them [ 31 , 34 , 38 ] reporting mixed sources for both the exposure and outcome assessment. Five meta-analyses [ 21 , 24 , 26 , 32 , 41 ] reported only secondary sources for the exposure assessment, three of them [ 21 , 24 , 41 ] reporting as well only secondary sources for the outcome assessment, while in the other two [ 26 , 32 ] only primary and mixed sources for the outcome assessment were reported respectively.

Reporting of the data source in the data extraction tables of the included meta-analyses

Abbreviations : 1ry number of individual studies in each MA based on primary data sources, 2ry number of individual studies in each MA based on secondary data sources, NR number of individual studies in each MA with not reported data source

a Although the meta-analysis shows the results of methodological quality assessment based on a standardized scale, it does not indicate the type of data source used for each individual observational study included in the meta-analysis

b Cohort with nested case-control analysis

c The meta-analysis reports that most of the included observational studies assessed medication exposure through a review of medical records

d The meta-analysis reports only data from high-quality observational studies

Source of data in the analysis of heterogeneity

All but two [ 20 , 42 ] of the meta-analyses performed subgroup and/or sensitivity analyses. Although three of them [ 23 , 34 , 36 ] considered the methods of outcome assessment – type of diagnostic assay used for Clostridium difficile infection, method of venous thrombosis diagnosis confirmation, and type of scale for psychosis symptoms assessment respectively– as stratification variables, only the second referred to the origin of the data. Only five meta-analyses [ 22 , 28 , 33 , 35 , 39 ] included meta-regression analyses to describe heterogeneity, none of which considered the source of data as an explanatory variable. Other findings for the inclusion of the data source as a variable in the analysis of heterogeneity are presented in Table Table3 3 .

Inclusion of the data source as a variable in the analysis of heterogeneity of the included meta-analyses

Abbreviations : APACHE acute physiology and chronic health evaluation, MIC minimum inhibitory concentration, SSRIs selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, TNF tumor necrosis factor

We finally assessed if the influence of the data origin on the conclusions of the meta-analyses was discussed by their respective authors. We found that only four meta-analyses [ 21 , 31 , 32 , 34 ] noted limitations derived from the type of data source used.

The findings of this research suggest that the origin of the data, either primary or secondary, is underexplored as a source of heterogeneity and an effect modifier in meta-analyses of drug effects published in general medicine journals with high impact. Few meta-analyses reported the source of data and only one [ 34 ] of the articles included in our survey compared and discussed the meta-analysis results considering the different sources of data.

Although it is usual to consider the design of the individual studies (i.e. case-control, cohort or experimental studies) in the analysis of the heterogeneity of a meta-analysis [ 43 , 44 ], the type of data source (primary vs secondary) is still rarely used for this purpose [ 9 , 45 ]. In fact, the current reporting guidelines for meta-analyses, such as MOOSE (Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) [ 18 ] or PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) [ 46 , 47 ], do not recommend that authors specifically report the origin of the data. This is probably due to the close relationship that exists between the study design and the type of data source used, despite the fact that each criterion has its own basis. Performing this additional analysis is a simple task that involves no additional cost. Failure to do so may lead to diverging conclusions [ 8 ].

Conclusions about the effects of a drug that are derived from studies based exclusively on data from secondary sources may be dicey, among other reasons, because no information is collected on consumption of over-the-counter drugs (i.e. drugs that individuals can buy without a prescription) [ 48 ] and/or out-of-pocket expenses for prescription drugs (i.e. costs that individuals pay out of their own cash reserves) [ 49 ]. In the health care and insurance context, out-of-pocket expenses usually refer to deductibles, co-payments or co-insurance. Figure Figure2 2 shows the model that we propose to describe the relationship between the different data records according to their origin, including the possible loss of information (susceptible to be registered only through primary research).

Conceptual model of individual data recording. * Never dispensed. † Absence of dispensing of successive prescriptions (or self-medication) among patients with primary adherence, or inadequate secondary adherence

Failure to take these situations into account may lead to exposure measurement bias [ 48 , 49 ]. Consumption of a drug may be underestimated when only prescription data is used as secondary source without additionally considering unregistered consumption, such as over-the-counter consumption (e.g. oral contraceptives [ 34 , 50 ]), that may only be available from a primary database. Alternatively, this may occur when dispensing data for billing purposes (reimbursement) are used for clinical research, if out-of-pocket expenses are not considered (see Fig. Fig.2). 2 ). The portion of the medical bill that the insurance company does not cover, and that the individual must pay on his own, is unlikely to be recorded. Data on the sale of over-the-counter drugs will also not be available in this scenario.

The reverse situation may also occur and consumption may be overestimated when only prescription data is used, if the prescribed drug is not dispensed by the pharmacist; or when dispensing data is used, if the drug is not really consumed by the patient. While primary non-adherence occurs when the patient does not pick up the medication after the first prescription, secondary non-adherence refers to the absence of dispensing of successive prescriptions among patients with primary adherence, or to inadequate secondary adherence (i.e. ≥20% of time without adequate medication) [ 51 ] (see Fig. Fig.2). 2 ). In some diseases the medication adherence is very low [ 52 – 55 ], with percentages of primary non-adherence (never dispensed) that exceed 30% [ 56 ]. It should be noted that the impact of non-adherence varies from medication to medication. Therefore, it must be defined and measured in the context of a particular therapy [ 57 ].

Moreover, failing to take into consideration the portion of consumption due to over-the-counter and/or out-of-pocket expenses may lead to confounding , as that variable may be related to the socio-economic level and/or to the potential of access to the health system [ 58 ], which are independent risk factors of adverse outcomes of some medications (e.g. myocardial infarction [ 21 , 28 , 30 , 41 ]). Given the presence of high-deductible health plans and the high co-insurance rate for some drugs, cost-sharing may deter clinically vulnerable patients from initiating essential medications, thus negatively affecting patient adherence [ 59 , 60 ].

Outcome misclassification may also give rise to measurement bias and heterogeneity [ 61 ]. This occurs, for example, in the meta-analysis that evaluates the relationship between combined oral contraceptives and the risk of venous thrombosis [ 34 ]. In the studies without objective confirmation of the outcome, the women were classified erroneously regardless of the use of contraceptives. This led to a non-differential misclassification that may have underestimated the drug–outcome relationship, especially when the third generation of progestogen is analysed: Risk ratio (RR) primary data = 6.2 (95% confidence interval (CI) 5.2–7.4), RR secondary data = 3.0 (95% CI 1.7–5.4) [ 34 ].

On the one hand, medical records are often considered as being the best information source for outcome variables. However, they present important limitations in the recording of medications taken by patients [ 62 ]. On the other hand, dispensing records show more detailed data on the measurement of drug exposure. However, they do not record the over-the-counter or out-of-pocket drug consumption at an individual level [ 48 , 49 ], apart from offering unreliable data on outcome variables [ 62 , 63 ].

Limitations

The first limitation of this research is that its findings may not be applicable to journals not included in our survey such as journals with low impact factor. Despite the widespread use of the impact factor metric [ 64 ], this method has inherent weaknesses [ 65 , 66 ]. However, meta-analyses published in high impact general medicine journals are likely to be most rigorously performed and reported due to their greater availability of resources and procedures [ 12 , 14 ]. It is then expected that the overall reporting quality of articles published in other lesser-known journals will be similar. Another limitation would be related to the limited search period . In this sense, and given that the general tendency is the improvement of the methodology of published meta-analyses [ 67 , 68 ], we find no reason to suspect that the adverse conclusions could be different before the period from 2012 to 2018. Although it exceeds the objective of this research, one last limitation may be the inability to reanalyse the included meta-analyses stratifying by the type of data source since our study design restricts the conclusions to the published data of the meta-analyses, which were insufficiently reported , or the number of individual studies in each stratum was insufficient to calculate a pooled measure (see Table Table2 2 ).

Owing to automated capture of data on drug prescription and dispensing that are used for billing and other administration purposes, as well as to the implementation of electronic medical records, secondary databases have generated enormous possibilities. However, neither their limitations, nor the risk of bias that they pose should be overlooked [ 69 ]. Thus, researchers should consider the link between administrative databases and medical records, as well as the advisability of combining secondary and primary data in order to minimize the occurrence of biases due to the use of any of these databases.

No source of heterogeneity in a meta-analysis should ever be considered alone but always as part of an interconnected set of potential questions to be addressed. In particular, the origin of the data, either primary or secondary, is insufficiently explored as a source of heterogeneity in meta-analyses of drug effects, even in those published in high impact general medicine journals. Thus, we believe that authors should systematically include the source of data as an additional variable in subgroup and sensitivity analyses, or meta-regression analyses, and discuss its influence on the meta-analysis results. Likewise, reviewers, editors and future guidelines should also consider the origin of the data as a potential cause of heterogeneity in meta-analyses of observational studies that include both primary and secondary data. Failure to do this may lead to misleading conclusions, with negative effects on clinical and regulatory decisions.

Additional file

Excluded articles. List of articles excluded with reasons for exclusion. (PDF 247 kb)

This study received no funding from the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of data and materials

Abbreviations, authors’ contributions.

AF and GP-R contributed to study conception and design. GP-R, FR and AF contributed to searching, screening, data collection and analyses. GP-R was responsible for drafting the manuscript. FR, MTH, BT and AF provided comments and made several revisions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Guillermo Prada-Ramallal, Email: [email protected] .

Fatima Roque, Email: tp.gpi@euqorf .

Maria Teresa Herdeiro, Email: tp.au@oriedrehaseret .

Bahi Takkouche, Email: [email protected] .

Adolfo Figueiras, Phone: (+34) 981 95 11 92, Email: [email protected] .

Understanding Nursing Research

What is primary research, how can i tell if my article is "primary research", limiting your search to primary research.

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research

- Experimental Design

- Is it a Nursing journal?

- Is it Written by a Nurse?

- Systematic Reviews and Secondary Research

- Quality Improvement Plans

Your Team! College of Education and Human Development and College of Nursing and Health Sciences

Left to Right: Trisha Hernandez, Emily Murphy, Lorin Flores, Aida Almanza-Ferro.

We are the librarians for College of Education and Human Development, and the College of Nursing. We look forward to working with you! To contact us or to make an appointment:

Submit your request and we'll get right back to you!

Or, you can reach out directly. For our email addresses and phone numbers, see the list below:

Aida Almanza-Ferro | [email protected] | 361-825-2356 Lorin Flores | [email protected] | 361-825-2609 Trisha Hernandez | [email protected] |361-825-2687 Emily Sartorius Murphy | [email protected] | 361-825-2610 Librarians are available M-F, 8-5.

The phrase "Primary" can mean something different depending on what subject you're in.

In History , for example, you might hear the phrase "primary sources." This means the researcher is looking for sources that date back to when an event occurred. Primary sources can be a diary, a photograph, or a newspaper clipping.

If this is the kind of research you're looking for, check out this research guide on how to find primary sources:

- Primary Sources

If you're in Nursing or another scientific field you're more likely to hear the phrase "Primary Research."

Primary Research refers to research that was conducted by the author of the article you're reading. So if you're reading an article and in the methodology section the author refers to recruiting participants, identifying a control group, etc. you can be pretty sure the author has conducted the research themselves.

When you're asked to find primary research, you're being asked to find articles describing research that was conducted by the authors.

Check out the video below for an explanation of the differences between primary and secondary research.

To determine if the article you're looking at is considered Primary Research, look for the following:

- In the Abstract, can you find a description of research being conducted?

- Were participants recruited?

- Were surveys distributed?

The main question to ask yourself is "Did the author conduct research, or did they read and synthesize other people's research?"

If you've found an article in CINAHL and you want to know if it's primary research, look under "Publication Type" to see if it's a research article.

This is not always 100% correct, though. To be sure, you should always read the Methodology section to understand what kind of article you're looking at.

If you're using PubMed, you can check the article's Keywords and Abstract for clues to see if the article is primary research, like in the article below:

Or you can check to see if the article includes a "Publication Type" section like this article:

The following Publication Types are usually considered Primary Research:

- Adaptive Clinical Trial

- Clinical Study

- Clinical Trial

- Controlled Clinical Trial

- Equivalence Trial

- Evaluation Studies

- Observational Study

- Pragmatic Clinical Trial

- Randomized Controlled Trial

Remember, you will always need to read the Methodologies section of an article to be sure the article is an example of primary research!

In certain databases you can specify that you're only interested in resources that are considered primary research.

Two of those databases are CINAHL and PubMed, which you can access here:

To limit your results to primary research in CINAHL, check the "Research Article" box on the homepage before you hit "Search"

This check box is helpful, but it isn't 100% correct, so always read the Methodology section of your article to determine what kind of article it is!

If you're conducting a search in PubMed and want to limit your results to a certain kind of article, you can enter your search terms on the homepage and click "Search."

Then, when you're on your results page, use the limiters on the left side of the screen to specify the "Article Type" you're interested in. Under "Article Types" click the "Customize..." link to see the full list of article types available to you.

Check any of the article types you're interested in (don't forget to scroll down on this list!) and then click the blue "Show" button at the bottom of the pop up window.

Now the Article Types you just selected should appear under the Article Types heading. Click on the article types you want to show up in your results list and your results will limit themselves to just those that meet your criteria.

Remember to read the article's Methodology section yourself before deciding whether or not it's Primary Research! These limits are great, but they aren't always 100% accurate.

- Next: Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research >>

- Last Updated: Feb 6, 2024 9:34 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.tamucc.edu/nursingresearch

- Open access

- Published: 16 March 2024

Impact of reimbursement systems on patient care – a systematic review of systematic reviews

- Eva Wagenschieber 1 &

- Dominik Blunck ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8843-2411 1

Health Economics Review volume 14 , Article number: 22 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

295 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

There is not yet sufficient scientific evidence to answer the question of the extent to which different reimbursement systems influence patient care and treatment quality. Due to the asymmetry of information between physicians, health insurers and patients, market-based mechanisms are necessary to ensure the best possible patient care. The aim of this study is to investigate how reimbursement systems influence multiple areas of patient care in form of structure, process and outcome indicators.

For this purpose, a systematic literature review of systematic reviews is conducted in the databases PubMed, Web of Science and the Cochrane Library. The reimbursement systems of salary, bundled payment, fee-for-service and value-based reimbursement are examined. Patient care is divided according to the three dimensions of structure, process, and outcome and evaluated in eight subcategories.

A total of 34 reviews of 971 underlying primary studies are included in this article. International studies identified the greatest effects in categories resource utilization and quality/health outcomes. Pay-for-performance and bundled payments were the most commonly studied models. Among the systems examined, fee-for-service and value-based reimbursement systems have the most positive impact on patient care.

Patient care can be influenced by the choice of reimbursement system. The factors for successful implementation need to be further explored in future research.

The health care system has a variety of payment and reimbursement systems that provide different financial incentives for patient care. Every payment system carries incentives to over- or underprovide care. There is no optimal solution, as there is constant pressure to adapt and reform in order to ensure the best possible quality of care. Health care systems are reaching their financial limits and therefore it is desirable to achieve an increase in efficiency in patient treatment and, for example, to avoid unnecessary interventions [ 1 ]. To achieve this, health policy must ensure a regulatory framework in which health status is also an economic incentive for all actors in the health system, promoting health benefits and reducing economic disincentives.

Physicians have a stronger position in the physician–patient relationship because of the knowledge and information advantage, and problems arise in the provision of care when physicians’ financial interest do not match the patients’ need for treatment [ 2 ]. In addition to medical necessity, economic and financial factors also play a key role in patient treatment. Medical decisions in the inpatient sector are influenced daily by economic requirements, economic considerations, and financial resources, potentially with negative consequences for the quality of treatment and patient safety. In the hospital setting, economization is exemplified in that physicians often feel ethical conflicts and economic goals occur at the expense of adjustments in length of stay, case numbers, and patient selection [ 3 ]. The influence on patient care is examined under four different reimbursement systems: Salary, bundled payment, fee-for-service (FFS), value-based reimbursement. With a fixed salary, remuneration is based solely on the duration of working hours, whereas the type and volume of service, as well as the number of treatment cases or patients enrolled, have no influence on financial income. At the same time, both an advantage and a disadvantage in this reimbursement system is the dependence of the quality of treatment on the intrinsic motivation of the provider [ 2 ]. Bundled payment is the term for payments such as capitation or disease related groups (DRGs). Services are combined and “bundled” for payment during a single patient contact or over a temporal episode. One disadvantage of this reimbursement system is the incentive for health care providers to treat as many patients as possible with as little effort as possible and thus to engage in risk selection. On the other hand, this can increase the incentive for preventive measures on the part of health care providers [ 4 ]. In FFS reimbursement, the provider’s fee is based on the volume of services rendered. Shared-savings payment models are a mix of FFS and a fixed salary where providers participate from savings they achieve in patient care. This creates the disadvantage of FFS reimbursement that service providers will unnecessarily expand the number of services for monetary reasons, resulting in unnecessary care at the expense of payers and potentially patients. On the other hand, (potentially expensive) diseases can be identified and treated earlier through increased preventive measures [ 2 , 5 ]. Value-based reimbursement additionally promotes the quality and success of medical procedures. Remuneration is expanded to the extent that it is linked to predefined quality targets at the levels of transparency, accessibility to care, indication, structure, process or outcome. While value-based reimbursement can promote the intrinsic motivation of providers, care must be taken to ensure that there is no risk selection for patients who can be treated well or that there are no negative spill-over effects into other areas of treatment. Another disadvantage of this reimbursement system is the large number of factors besides medical treatment that contribute to recovery, such as comorbidities or socioeconomic factors [ 1 ].

Other reviews have addressed effects on patient care in outpatient settings [ 6 ] or included studies from developing countries in their evaluations [ 7 ]. Previous studies only focus on specific areas of patient care [ 8 ], are not methodologically designed as a systematic review [ 9 ], focus only on individual specialties [ 10 ] or reimbursement systems [ 11 ] and do not compare the effect of different reimbursement systems. A comprehensive and structured overview, comparing the outcomes of several reimbursement systems on areas of patient care, is missing.

The objective of this paper, thus, is to provide a review of systematic reviews on the relationship between reimbursement systems and patient care. The research question is narrowed down using the PICOS algorithm: Physicians (Population), Reimbursement systems (Intervention), different reimbursement systems or differences over time (Comparison), effects on patient care divided into the parameters structure, process, outcome (Outcome), systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Study type). The aim is to analyze how reimbursement systems affect patient care across countries.

Materials and methods

The systematic review follows the guidelines of the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Metaanalyses) statement [ 12 ], has been performed via the databases PubMed, Web of Science and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews between 02/12/2021 and 22/12/2021 and has been complemented with an additional search on Google Scholar and in the reference lists of relevant studies. The search term was formed by linking keywords and their synonyms from previously published relevant studies on the three aspects of the research questions: impact, reimbursement systems, and patient care (see Table 1 for the full search term for each database).

Inclusion criteria are defined as (a) the paper must be a systematic review or meta-analysis, (b) the countries considered must be industrialized nations, and (c) the effect of payment/reimbursement systems on patient care was examined.

The search period is set to ten years and only studies published in German or English were included. All records were exported to EndNote 20 [ 13 ] and screened by the authors; disagreements were solved by discussion. All studies categorized as “relevant” or “uncertain” in this step were analyzed in full text.

Studies categorized as relevant after full text analysis were included in this work and assessed for study quality using the AMSTAR-2 score, which is a comprehensive questionnaire to assess systematic reviews of (non)randomized trials [ 14 ]. Using the framework of Donabedian, the results are divided into the three dimensions structure, process, outcome [ 15 ] (see Table 2 ). The structure dimension combines the following parameters: “unintended consequences” and “organizational changes”. Unintended consequences are mostly related to changes in risk selection or spill-over effects, whereas organizational changes are related to effects in personnel structures, for example. The dimension of structure is of particular interest for health care authorities as well as payers as it shapes the organizational characteristics of how care is delivered.

The categories “resource utilization”, “access”, and “behavior” are combined under the parameter process. While resource utilization mostly describes changes in readmission rates or length of stay, the access category reflects socioeconomic inequalities in the utilization of health care services. The behavior category includes effects related to intrinsic motivation, preventive services provided by physicians, or documentation of health parameters, among others. The dimension of process defines how providers deliver care as well as the points of contacts for patients.

The outcome dimension, on the other hand, combines the parameters “quality/health outcomes”, “efficiency”, and “economic effects”. Actual changes in mortality, treatment quality, screening or vaccination rates are mapped in the “quality/health outcomes” category. The “efficiency” category deals with the effects on direct savings in the provision of a specific medical service or effects on salaries, whereas the “economic effects” category records effects that are significant for society. The dimension of outcome could be regarded of the main value driver from a patient perspective as it answers to what extent patients’ original need for care is fulfilled. Furthermore, outcomes are of particular interest for payers, as payers commonly decide, for example, what services are reimbursed and therefore potentially have a high interest in a positive cost-outcome-relation.

For all reimbursement systems described, the number of included studies, as well as the examined medical specialties or physician groups and countries in which the interventions are carried out, are also transferred in each case. For each reimbursement system described, it is examined whether it improved or worsened the outcome categories of patient care, whether there were heterogeneous results, or whether no difference was found in the outcome categories before and after the intervention. The frequency reviews found an improvement, worsening, heterogeneous outcome, or no difference for each payment system per outcome category were summarized in a single table. In this study, increases in healthcare utilization, documentation of health parameters, and higher screening rates or lower mortality rates are defined as improvements. A measurable increase in risk selection, negative spill-over effects, longer hospital stays, or higher readmission rates are considered deteriorations in patient care. In the economic categories of efficiency and economic effects, savings in health care spending and total societal spending, respectively, are considered as improvements. Reviews finding heterogeneous results include studies with conflicting findings, because some of the included primary studies find positive results in one category, whereas other primary studies find negative effects or no significant effects at all, leaving the study or respective review with an overall heterogeneous result. It is assumed that health care is optimized by an increase in health care services, shorter lengths of stay, more efficient care, and lower overall societal health care expenditures.

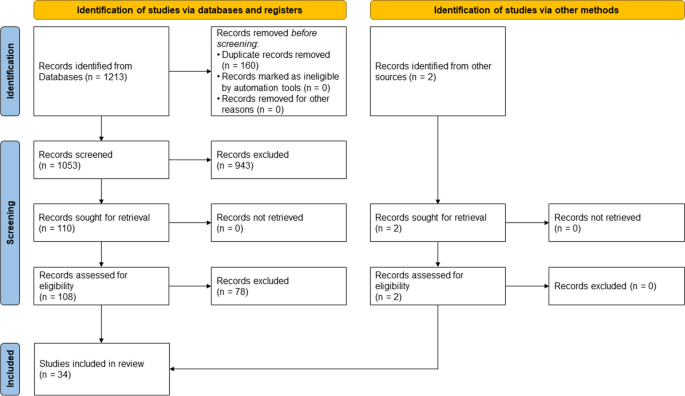

A total of 1,213 hits were identified by the database search on 02/12/2021, with 2 additional hits identified by the search in Google Scholar. After duplicates were removed, 1,053 abstracts were screened by both authors, resulting in 943 hits being initially excluded. The remaining 110 hits were analyzed in full text, whereupon 34 hits were included in this work (see Fig. 1 ).

Overall, the 34 included systematic reviews describe the influences on patient care based on a total of 971 primary studies. Ten of the 34 included reviews are rated as high quality, 16 as moderate quality, and eight as low quality according to the assessment procedure using the AMSTAR-2 questionnaire (see Table 3 ). Some of the identified systematic reviews examined more than one reimbursement system. Therefore, for the sake of clarity, we refer to a total number of 60 studies in the following. Of these, the reimbursement system salary was investigated in four studies, bundled payments in 15, FFS payments in a further eleven studies and value-based reimbursement in a total of 29 studies. Out of the 60 studies 45 were conducted in the USA, 38 in European countries, 28 in the UK, 23 in other countries and 17 in Canada. An overview of the results is provided in Table 4. . In the following, we describe the results of the systematic review regarding Donabedian’s categories of quality: structure, process, and outcome.

Unintended consequences

No unintended consequences in patient care are found for the salary payment system. Studies find heterogeneous results for this category for bundled payments in form of a decrease in treatment volume while there is an increase in risk selection and case complexity [ 16 , 17 ]. An association was found between bundled payments and patient selection based on sociodemographic factors and comorbidities [ 16 ]. Positive changes were noted in indicators that were not included in the FFS model; these were, however, only short-term [ 18 ]. Some reviews find unintended changes after implementation of pay-for-performance models (P4P), a type of value-based reimbursement, in form of risk selection, spill-over effects, protocol-driven and less patient-centered care and neglect of non-incentive indicators [ 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 ]. Some studies find no evidence for a change in patient risk selection in their included primary studies [ 24 , 25 ].

Organizational changes

There are heterogeneous results on the impact on patient care after the introduction of different payment systems. One study reports effects in the form of increasing numbers of physicians per patient and decreasing numbers for bundled payments [ 26 ]. While one review finds heterogeneous results for salary, bundled payment, FFS, and value-based payment for the structural organization of patient care [ 27 ], others find both positive and negative effects for value-based payment as an improvement in care management processes or a worse organization of large hospitals [ 28 , 29 ].

Resource utilization