Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 19 July 2018

Endometriosis

- Krina T. Zondervan 1 , 2 ,

- Christian M. Becker 1 ,

- Kaori Koga 3 ,

- Stacey A. Missmer 4 , 5 ,

- Robert N. Taylor 6 &

- Paola Viganò 7

Nature Reviews Disease Primers volume 4 , Article number: 9 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

21k Accesses

678 Citations

118 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Infertility

- Inflammation

- Reproductive disorders

- Reproductive techniques

Endometriosis is a common inflammatory disease characterized by the presence of tissue outside the uterus that resembles endometrium, mainly on pelvic organs and tissues. It affects ~5–10% of women in their reproductive years — translating to 176 million women worldwide — and is associated with pelvic pain and infertility. Diagnosis is reliably established only through surgical visualization with histological verification, although ovarian endometrioma and deep nodular forms of disease can be detected through ultrasonography and MRI. Retrograde menstruation is regarded as an important origin of the endometrial deposits, but other factors are involved, including a favourable endocrine and metabolic environment, epithelial–mesenchymal transition and altered immunity and inflammatory responses in genetically susceptible women. Current treatments are dictated by the primary indication (infertility or pelvic pain) and are limited to surgery and hormonal treatments and analgesics with many adverse effects that rarely provide long-term relief. Endometriosis substantially affects the quality of life of women and their families and imposes costs on society similar to those of other chronic conditions such as type 2 diabetes mellitus, Crohn’s disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Future research must focus on understanding the pathogenesis, identifying disease subtypes, developing non-invasive diagnostic methods and targeting non-hormonal treatments that are acceptable to women who wish to conceive.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 1 digital issues and online access to articles

92,52 € per year

only 92,52 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Rethinking mechanisms, diagnosis and management of endometriosis

Real world data on symptomology and diagnostic approaches of 27,840 women living with endometriosis

Endometriosis and chronic pelvic pain have similar impact on women, but time to diagnosis is decreasing: an Australian survey

Marsh, E. E. & Laufer, M. R. Endometriosis in premenarcheal girls who do not have an associated obstructive anomaly. Fertil. Steril. 83 , 758–760 (2005).

PubMed Google Scholar

Halme, J., Hammond, M. G., Hulka, J. F., Raj, S. G. & Talbert, L. M. Retrograde menstruation in healthy women and in patients with endometriosis. Obstet. Gynecol. 64 , 151–154 (1984).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Horton, J. D., Dezee, K. J., Ahnfeldt, E. P. & Wagner, M. Abdominal wall endometriosis: a surgeon’s perspective and review of 445 cases. Am. J. Surg. 196 , 207–212 (2008).

Goldberg, J. & Davis, A. Extrapelvic endometriosis. Semin. Reprod. Med. 35 , 98–101 (2016).

Hirsch, M. et al. Diagnosis and management of endometriosis: a systematic review of international and national guidelines. BJOG 125 , 556–564 (2018).

American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996. Fertil. Steril. 67 , 817–821 (1997).

Google Scholar

Vercellini, P. et al. Association between endometriosis stage, lesion type, patient characteristics and severity of pelvic pain symptoms: a multivariate analysis of over 1000 patients. Hum. Reprod. 22 , 266–271 (2006).

Nnoaham, K. E. et al. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil. Steril. 96 , 366–373.e8 (2011). This paper presents the largest multicentre prospective study to date describing the effects of endometriosis; in women undergoing their first laparoscopy, a significantly reduced physical (but not mental) HRQOL, which was associated with delay in diagnosis, was reported in those with endometriosis compared with endometriosis-free symptomatic and asymptomatic women .

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Peres, L. C. et al. Racial/ethnic differences in the epidemiology of ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis of 12 case-control studies. Int. J. Epidemiol. 47 , 460–472 (2018).

Eskenazi, B. & Warner, M. L. Epidemiology of endometriosis. Obstet. Gynecol. Clin. North Am. 24 , 235–258 (1997).

Buck Louis, G. M. et al. Incidence of endometriosis by study population and diagnostic method: the ENDO study. Fertil. Steril. 96 , 360–365 (2011).

Janssen, E. B., Rijkers, A. C. M., Hoppenbrouwers, K., Meuleman, C. & D’Hooghe, T. M. Prevalence of endometriosis diagnosed by laparoscopy in adolescents with dysmenorrhea or chronic pelvic pain: a systematic review. Hum. Reprod. Update 19 , 570–582 (2013).

Zondervan, K. T., Cardon, L. R. & Kennedy, S. H. What makes a good case–control study? Hum. Reprod. 17 , 1415–1423 (2002).

Adamson, G. D., Kennedy, S. & Hummelshoj, L. Creating solutions in endometriosis: global collaboration through the World Endometriosis Research Foundation. J. Endometr. Pelvic Pain Disord. 2 , 3–6 (2010).

Gemmell, L. C. et al. The management of menopause in women with a history of endometriosis: a systematic review. Hum. Reprod. Update 23 , 481–500 (2017).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Leibson, C. L. et al. Incidence and characterization of diagnosed endometriosis in a geographically defined population. Fertil. Steril. 82 , 314–321 (2004).

Missmer, S. A. Incidence of laparoscopically confirmed endometriosis by demographic, anthropometric, and lifestyle factors. Am. J. Epidemiol. 160 , 784–796 (2004).

Nnoaham, K. E., Webster, P., Kumbang, J., Kennedy, S. H. & Zondervan, K. T. Is early age at menarche a risk factor for endometriosis? A systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies. Fertil. Steril. 98 , 702–712.e6 (2012).

Missmer, S. A. et al. Reproductive history and endometriosis among premenopausal women. Obstet. Gynecol. 104 , 965–974 (2004).

Peterson, C. M. et al. Risk factors associated with endometriosis: importance of study population for characterizing disease in the ENDO Study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 208 , 451.e1–451.e11 (2013).

Prescott, J. et al. A prospective cohort study of endometriosis and subsequent risk of infertility. Hum. Reprod. 31 , 1475–1482 (2016).

Buck Louis, G. M. et al. Women’s reproductive history before the diagnosis of incident endometriosis. J. Womens Health 25 , 1021–1029 (2016).

Farland, L. V. et al. History of breast feeding and risk of incident endometriosis: prospective cohort study. BMJ 358 , j3778 (2017).

Leeners, B., Damaso, F., Ochsenbein-Kölble, N. & Farquhar, C. The effect of pregnancy on endometriosis — facts or fiction? Hum. Reprod. Update 24 , 290–299 (2018).

Shah, D. K., Correia, K. F., Vitonis, A. F. & Missmer, S. A. Body size and endometriosis: results from 20 years of follow-up within the Nurses’ Health Study II prospective cohort. Hum. Reprod. 28 , 1783–1792 (2013).

Farland, L. V. et al. Associations among body size across the life course, adult height and endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 32 , 1732–1742 (2017).

McCann, S. E. et al. Endometriosis and body fat distribution. Obstet. Gynecol. 82 , 545–549 (1993).

Rahmioglu, N. et al. Genome-wide enrichment analysis between endometriosis and obesity-related traits reveals novel susceptibility loci. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24 , 1185–1199 (2015).

de Ridder, C. M. et al. Body fat mass, body fat distribution, and plasma hormones in early puberty in females. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 70 , 888–893 (1990).

Cramer, D. W. The relation of endometriosis to menstrual characteristics, smoking, and exercise. JAMA 255 , 1904–1908 (1986).

Baron, J. A., La Vecchia, C. & Levi, F. The antiestrogenic effect of cigarette smoking in women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 162 , 502–514 (1990).

Ohtake, F., Fujii-Kuriyama, Y., Kawajiri, K. & Kato, S. Cross-talk of dioxin and estrogen receptor signals through the ubiquitin system. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 127 , 102–107 (2011).

Parazzini, F. Selected food intake and risk of endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 19 , 1755–1759 (2004).

Trabert, B., Peters, U., De Roos, A. J., Scholes, D. & Holt, V. L. Diet and risk of endometriosis in a population-based case–control study. Br. J. Nutr. 105 , 459–467 (2010).

Missmer, S. A. et al. A prospective study of dietary fat consumption and endometriosis risk. Hum. Reprod. 25 , 1528–1535 (2010).

Savaris, A. L. & do Amaral, V. F. Nutrient intake, anthropometric data and correlations with the systemic antioxidant capacity of women with pelvic endometriosis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 158 , 314–318 (2011).

Mozaffarian, D. et al. Dietary intake of trans fatty acids and systemic inflammation in women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 79 , 606–612 (2004).

Lebovic, D. I., Mueller, M. D. & Taylor, R. N. Immunobiology of endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 75 , 1–10 (2001).

Rier, S. E. et al. Endometriosis in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) following chronic exposure to 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin. Toxicol. Sci. 21 , 433–441 (1993).

CAS Google Scholar

Smarr, M. M., Kannan, K. & Buck Louis, G. M. Endocrine disrupting chemicals and endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 106 , 959–966 (2016).

Kvaskoff, M. et al. Endometriosis: a high-risk population for major chronic diseases? Hum. Reprod. Update 21 , 500–516 (2015). This article presents a meta-analysis of all data and a critical methodologic review suggesting that patients with endometriosis are at higher risk of ovarian and breast cancers, cutaneous melanoma, asthma and some autoimmune, cardiovascular and atopic diseases and are at decreased risk of cervical cancer .

Benagiano, G., Brosens, I. & Habiba, M. Structural and molecular features of the endomyometrium in endometriosis and adenomyosis. Hum. Reprod. Update 20 , 386–402 (2014).

Kunz, G. et al. Adenomyosis in endometriosis — prevalence and impact on fertility. Evidence from magnetic resonance imaging. Hum. Reprod. 20 , 2309–2316 (2005).

Pearce, C. L. et al. Association between endometriosis and risk of histological subtypes of ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis of case–control studies. Lancet Oncol. 13 , 385–394 (2012).

Kim, H. S., Kim, T. H., Chung, H. H. & Song, Y. S. Risk and prognosis of ovarian cancer in women with endometriosis: a meta-analysis. Br. J. Cancer 110 , 1878–1890 (2014).

Farland, L. V. et al. Endometriosis and the risk of skin cancer: a prospective cohort study. Cancer Causes Control 28 , 1011–1019 (2017).

Sinaii, N. High rates of autoimmune and endocrine disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and atopic diseases among women with endometriosis: a survey analysis. Hum. Reprod. 17 , 2715–2724 (2002).

Nielsen, N. M., Jorgensen, K. T., Pedersen, B. V., Rostgaard, K. & Frisch, M. The co-occurrence of endometriosis with multiple sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjogren syndrome. Hum. Reprod. 26 , 1555–1559 (2011).

Harris, H. R. et al. Endometriosis and the risks of systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis in the Nurses’ Health Study II. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 75 , 1279–1284 (2015).

Mu, F. et al. Association between endometriosis and hypercholesterolemia or hypertensionnovelty and significance. Hypertension 70 , 59–65 (2017).

Nyholt, D. R. et al. Genome-wide association meta-analysis identifies new endometriosis risk loci. Nat. Genet. 44 , 1355–1359 (2012).

Borghese, B., Zondervan, K. T., Abrao, M. S., Chapron, C. & Vaiman, D. Recent insights on the genetics and epigenetics of endometriosis. Clin. Genet. 91 , 254–264 (2017).

Treloar, S. A. et al. Genomewide linkage study in 1,176 affected sister pair families identifies a significant susceptibility locus for endometriosis on chromosome 10q26. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 77 , 365–376 (2005).

Zondervan, K. T. et al. Significant evidence of one or more susceptibility loci for endometriosis with near-Mendelian inheritance on chromosome 7p13–15. Hum. Reprod. 22 , 717–728 (2006).

Rahmioglu, N., Montgomery, G. W. & Zondervan, K. T. Genetics of endometriosis. Womens Health 11 , 577–586 (2015).

Sapkota, Y. et al. Meta-analysis identifies five novel loci associated with endometriosis highlighting key genes involved in hormone metabolism. Nat. Commun. 8 , 15539 (2017).

Lee, S. H. et al. Estimation and partitioning of polygenic variation captured by common SNPs for Alzheimer’s disease, multiple sclerosis and endometriosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22 , 832–841 (2012).

Uimari, O. et al. Genome-wide genetic analyses highlight mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 32 , 780–793 (2017).

Lu, Y. et al. Shared genetics underlying epidemiological association between endometriosis and ovarian cancer. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24 , 5955–5964 (2015).

Painter, J. N. et al. Genetic overlap between endometriosis and endometrial cancer: evidence from cross-disease genetic correlation and GWAS meta-analyses. Cancer Med. 7 , 1978–1987 (2018).

Sapkota, Y. et al. Analysis of potential protein-modifying variants in 9000 endometriosis patients and 150000 controls of European ancestry. Sci. Rep. 7 , 11380 (2017).

Visscher, P. M., Brown, M. A., McCarthy, M. I. & Yang, J. Five years of GWAS discovery. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 90 , 7–24 (2012).

Fung, J. N. et al. The genetic regulation of transcription in human endometrial tissue. Hum. Reprod. 32 , 1–12 (2017).

Becker, C. M. et al. World Endometriosis Research Foundation Endometriosis Phenome and Biobanking Harmonisation Project: I. Surgical phenotype data collection in endometriosis research. Fertil. Steril. 102 , 1213–1222 (2014).

Vitonis, A. F. et al. World Endometriosis Research Foundation Endometriosis Phenome and Biobanking Harmonization Project: II. Clinical and covariate phenotype data collection in endometriosis research. Fertil. Steril. 102 , 1223–1232 (2014).

Rahmioglu, N. et al. World Endometriosis Research Foundation Endometriosis Phenome and Biobanking Harmonization Project: III. Fluid biospecimen collection, processing, and storage in endometriosis research. Fertil. Steril. 102 , 1233–1243 (2014).

Fassbender, A. et al. World Endometriosis Research Foundation Endometriosis Phenome and Biobanking Harmonisation Project: IV. Tissue collection, processing, and storage in endometriosis research. Fertil. Steril. 102 , 1244–1253 (2014).

Wiegand, K. C. et al. ARID1A mutations in endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas. N. Engl. J. Med. 363 , 1532–1543 (2010).

Yamamoto, S., Tsuda, H., Takano, M., Tamai, S. & Matsubara, O. Loss of ARID1A protein expression occurs as an early event in ovarian clear-cell carcinoma development and frequently coexists with PIK3CA mutations. Mod. Pathol. 25 , 615–624 (2011).

Anglesio, M. S. et al. Cancer-associated mutations in endometriosis without cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 376 , 1835–1848 (2017).

Kato, S., Lippman, S. M., Flaherty, K. T. & Kurzrock, R. The conundrum of genetic ‘drivers’ in benign conditions. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 108 , djw036 (2016).

Guo, S.-W. Epigenetics of endometriosis. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 15 , 587–607 (2009).

Wu, Y., Starzinski-Powitz, A. & Guo, S.-W. Trichostatin A, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, attenuates invasiveness and reactivates E-cadherin expression in immortalized endometriotic cells. Reprod. Sci. 14 , 374–382 (2007).

Dyson, M. T. et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis predicts an epigenetic switch for GATA factor expression in endometriosis. PLoS Genet. 10 , e1004158 (2014).

Burney, R. O. et al. MicroRNA expression profiling of eutopic secretory endometrium in women with versus without endometriosis. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 15 , 625–631 (2009).

Saare, M. et al. Challenges in endometriosis miRNA studies — from tissue heterogeneity to disease specific miRNAs. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1863 , 2282–2292 (2017).

Sampson, J. A. Peritoneal endometriosis due to the menstrual dissemination of endometrial tissue into the peritoneal cavity. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 14 , 422–469 (1927).

Vercellini, P. et al. Asymmetry in distribution of diaphragmatic endometriotic lesions: evidence in favour of the menstrual reflux theory. Hum. Reprod. 22 , 2359–2367 (2007).

D’Hooghe, T. M., Bambra, C. S., Raeymaekers, B. M. & Koninckx, P. R. Increased prevalence and recurrence of retrograde menstruation in baboons with spontaneous endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 11 , 2022–2025 (1996).

Witz, C. A., Cho, S., Centonze, V. E., Montoya-Rodriguez, I. A. & Schenken, R. S. Time series analysis of transmesothelial invasion by endometrial stromal and epithelial cells using three-dimensional confocal microscopy. Fertil. Steril. 79 (Suppl. 1), 770–778 (2003).

Reis, F. M., Petraglia, F. & Taylor, R. N. Endometriosis: hormone regulation and clinical consequences of chemotaxis and apoptosis. Hum. Reprod. Update 19 , 406–418 (2013).

Sanchez, A. M. et al. The endometriotic tissue lining the internal surface of endometrioma: hormonal, genetic, epigenetic status, and gene expression profile. Reprod. Sci. 22 , 391–401 (2015).

Borghese, B., Zondervan, K. T., Abrao, M. S., Chapron, C. & Vaiman, D. Recent insights on the genetics and epigenetics of endometriosis. Clin. Genet. 91 , 254–264 (2016).

Meyer, R. Zur Frage der heterotopen Epithelwucherung, insbesondere des Peritonealepithels und in die Ovarien [German]. Virch Arch. Path. Anat. Phys. 250 , 595–610 (1924).

Ferguson, B. R., Bennington, J. L. & Haber, S. L. Histochemistry of mucosubstances and histology of mixed müllerian pelvic lymph node glandular inclusions. Evidence for histogenesis by müllerian metaplasia of coelomic epithelium. Obstet. Gynecol. 33 , 617–625 (1969).

Figueira, P. G. M., Abrão, M. S., Krikun, G. & Taylor, H. Stem cells in endometrium and their role in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1221 , 10–17 (2011).

Du, H. & Taylor, H. S. Contribution of bone marrow-derived stem cells to endometrium and endometriosis. Stem Cells 25 , 2082–2086 (2007).

Gargett, C. E. & Masuda, H. Adult stem cells in the endometrium. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 16 , 818–834 (2010).

Matsuzaki, S. & Darcha, C. Epithelial to mesenchymal transition-like and mesenchymal to epithelial transition-like processes might be involved in the pathogenesis of pelvic endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 27 , 712–721 (2012).

Somigliana, E. et al. Association rate between deep peritoneal endometriosis and other forms of the disease: pathogenetic implications. Hum. Reprod. 19 , 168–171 (2004).

Zheng, W. et al. Initial endometriosis showing direct morphologic evidence of metaplasia in the pathogenesis of ovarian endometriosis. Int. J. Gynecol. Pathol. 24 , 164–172 (2005).

Troncon, J. K. et al. Endometriosis in a patient with mayer-rokitansky-küster-hauser syndrome. Case Rep. Obstet. Gynecol. 2014 , 376231 (2014).

Taguchi, S., Enomoto, Y. & Homma, Y. Bladder endometriosis developed after long-term estrogen therapy for prostate cancer. Int. J. Urol. 19 , 964–965 (2012).

Halban, J. Hysteroadenosis metastatica. Zentralbl. Gyndkoi 7 , 387–391 (1925).

Mechsner, S. et al. Estrogen and progestogen receptor positive endometriotic lesions and disseminated cells in pelvic sentinel lymph nodes of patients with deep infiltrating rectovaginal endometriosis: a pilot study. Hum. Reprod. 23 , 2202–2209 (2008).

Gargett, C. E. et al. Potential role of endometrial stem/progenitor cells in the pathogenesis of early-onset endometriosis. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 20 , 591–598 (2014).

Witz, C. A. et al. Short-term culture of peritoneum explants confirms attachment of endometrium to intact peritoneal mesothelium. Fertil. Steril. 75 , 385–390 (2001).

Zeitoun, K. M. & Bulun, S. E. Aromatase: a key molecule in the pathophysiology of endometriosis and a therapeutic target. Fertil. Steril. 72 , 961–969 (1999).

Pellegrini, C. et al. The expression of estrogen receptors as well as GREB1, c-MYC, and cyclin D1, estrogen-regulated genes implicated in proliferation, is increased in peritoneal endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 98 , 1200–1208 (2012).

Plante, B. J. et al. G protein-coupled estrogen receptor (GPER) expression in normal and abnormal endometrium. Reprod. Sci. 19 , 684–693 (2012).

Han, S. J. et al. Estrogen receptor β modulates apoptosis complexes and the inflammasome to drive the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Cell 163 , 960–974 (2015).

Vercellini, P., Viganò, P., Somigliana, E. & Fedele, L. Endometriosis: pathogenesis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 10 , 261–275 (2013). For this review, the best-quality evidence was selected to describe the performance of diagnostic tools and the effectiveness of approaches to address endometriosis-associated symptoms and infertility .

Patel, B. et al. Role of nuclear progesterone receptor isoforms in uterine pathophysiology. Hum. Reprod. Update 21 , 155–173 (2014).

Al-Sabbagh, M., Lam, E. W.-F. & Brosens, J. J. Mechanisms of endometrial progesterone resistance. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 358 , 208–215 (2012).

La Marca, A., Carducci Artenisio, A., Stabile, G., Rivasi, F. & Volpe, A. Evidence for cycle-dependent expression of follicle-stimulating hormone receptor in human endometrium. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 21 , 303–306 (2005).

Zondervan, K. et al. Beyond endometriosis genome-wide association study: from genomics to phenomics to the patient. Semin. Reprod. Med. 34 , 242–254 (2016).

Jiang, Y., Chen, L., Taylor, R. N., Li, C. & Zhou, X. Physiological and pathological implications of retinoid action in the endometrium. J. Endocrinol. 236 , R169–R188 (2018).

Orvis, G. D. & Behringer, R. R. Cellular mechanisms of Müllerian duct formation in the mouse. Dev. Biol. 306 , 493–504 (2007).

Vigano, P. et al. Time to redefine endometriosis including its pro-fibrotic nature. Hum. Reprod. 33 , 347–352 (2018).

Yu, J. et al. Endometrial stromal decidualization responds reversibly to hormone stimulation and withdrawal. Endocrinology 157 , 2432–2446 (2016).

Yin, X., Pavone, M. E., Lu, Z., Wei, J. & Kim, J. J. Increased activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway compromises decidualization of stromal cells from endometriosis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 97 , E35–E43 (2012).

Du, Y., Liu, X. & Guo, S.-W. Platelets impair natural killer cell reactivity and function in endometriosis through multiple mechanisms. Hum. Reprod. 32 , 1–17 (2017).

Lessey, B., Lebovic, D. & Taylor, R. Eutopic endometrium in women with endometriosis: ground zero for the study of implantation defects. Semin. Reprod. Med. 31 , 109–124 (2013).

Cominelli, A. et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-27 is expressed in CD163+/CD206+ M2 macrophages in the cycling human endometrium and in superficial endometriotic lesions. Mol. Hum. Reprod. 20 , 767–775 (2014).

Takebayashi, A. et al. Subpopulations of macrophages within eutopic endometrium of endometriosis patients. Am. J. Reprod. Immunol. 73 , 221–231 (2015).

Nisenblat, V. et al. Blood biomarkers for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 5 , CD012179 (2016).

Wang, X.-Q. et al. The high level of RANTES in the ectopic milieu recruits macrophages and induces their tolerance in progression of endometriosis. J. Mol. Endocrinol. 45 , 291–299 (2010).

McKinnon, B. D., Kocbek, V., Nirgianakis, K., Bersinger, N. A. & Mueller, M. D. Kinase signalling pathways in endometriosis: potential targets for non-hormonal therapeutics. Hum. Reprod. Update 22 , 382–403 (2016).

Morotti, M., Vincent, K. & Becker, C. M. Mechanisms of pain in endometriosis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 209 , 8–13 (2017).

Berkley, K. J. The pains of endometriosis. Science 308 , 1587–1589 (2005).

Taylor, R. N. & Lebovic, D. I. in Yen and Jaffe’s Reproductive Endocrinology (eds Strauss, J. F. & Barbieri, R. L.) 565–585 (Saunders Elsevier, 2014). This book chapter discusses the diagnosis and management of endometriosis, with a particularly well-referenced review of theories of aetiology and pathogenesis

Gnecco, J. S. et al. Compartmentalized culture of perivascular stroma and endothelial cells in a microfluidic model of the human endometrium. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 45 , 1758–1769 (2017).

Sanchez, A. M. et al. The endometriotic tissue lining the internal surface of endometrioma. Reprod. Sci. 22 , 391–401 (2014).

Ryan, I. P., Schriock, E. D. & Taylor, R. N. Isolation, characterization, and comparison of human endometrial and endometriosis cells in vitro. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 78 , 642–649 (1994).

Greaves, E., Critchley, H. O. D., Horne, A. W. & Saunders, P. T. K. Relevant human tissue resources and laboratory models for use in endometriosis research. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 96 , 644–658 (2017).

Korch, C. et al. DNA profiling analysis of endometrial and ovarian cell lines reveals misidentification, redundancy and contamination. Gynecol. Oncol. 127 , 241–248 (2012).

Grümmer, R. Translational animal models to study endometriosis-associated infertility. Semin. Reprod. Med. 31 , 125–132 (2013). Given the ethical limitations of clinical studies, this is a comprehensive review of the use of animal models to investigate factors contributing to the fertility-compromising effects of endometriosis .

Bruner-Tran, K. L., McConaha, M. E. & Osteen, K. G. in Endometriosis. Science and Practice (eds Giudice, L. C., Evers, J. L. H. & Healy, D. L.) 270–283 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2012).

Mariani, M. et al. The selective vitamin D receptor agonist, elocalcitol, reduces endometriosis development in a mouse model by inhibiting peritoneal inflammation. Hum. Reprod. 27 , 2010–2019 (2012).

Fazleabas, A. in Endometriosis: Science and Practice (eds Giudice, L. C., Evers, J. L. & Healy, D. L.) 285–291 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2012).

Ngô, C. et al. Antiproliferative effects of anastrozole, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil on endometriosis in vitro and in vivo. Fertil. Steril. 94 , 1632–1638.e1 (2010).

Bruner-Tran, K. L., Osteen, K. G. & Duleba, A. J. Simvastatin protects against the development of endometriosis in a nude mouse model. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 94 , 2489–2494 (2009).

Pullen, N. et al. The translational challenge in the development of new and effective therapies for endometriosis: a review of confidence from published preclinical efficacy studies. Hum. Reprod. Update 17 , 791–802 (2011).

Greaves, E. et al. A novel mouse model of endometriosis mimics human phenotype and reveals insights into the inflammatory contribution of shed endometrium. Am. J. Pathol. 184 , 1930–1939 (2014).

Stilley, J. A. W., Woods-Marshall, R., Sutovsky, M., Sutovsky, P. & Sharpe-Timms, K. L. Reduced fecundity in female rats with surgically induced endometriosis and in their daughters: a potential role for tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase 11. Biol. Reprod. 80 , 649–656 (2009).

Zondervan, K. T. Familial aggregation of endometriosis in a large pedigree of rhesus macaques. Hum. Reprod. 19 , 448–455 (2004).

Lebovic, D. I. et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ receptor ligand partially prevents the development of endometrial explants in baboons: a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Endocrinology 151 , 1846–1852 (2010).

D’Hooghe, T. M. Clinical relevance of the baboon as a model for the study of endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 68 , 613–625 (1997).

Fazleabas, A. Progesterone resistance in a baboon model of endometriosis. Semin. Reprod. Med. 28 , 75–80 (2010).

D’Hooghe, T. M. et al. Nonhuman primate models for translational research in endometriosis. Reprod. Sci. 16 , 152–161 (2009).

Chapron, C. et al. Surgical complications of diagnostic and operative gynaecological laparoscopy: a series of 29,966 cases. Hum. Reprod. 13 , 867–872 (1998).

Chung, M. K., Chung, R. R., Gordon, D. & Jennings, C. The evil twins of chronic pelvic pain syndrome: endometriosis and interstitial cystitis. JSLS 6 , 311–314 (2002).

Redwine, D. B. Diaphragmatic endometriosis: diagnosis, surgical management, and long-term results of treatment. Fertil. Steril. 77 , 288–296 (2002).

Fedele, L. et al. Ileocecal endometriosis: clinical and pathogenetic implications of an underdiagnosed condition. Fertil. Steril. 101 , 750–753 (2014).

DiVasta, A. D., Vitonis, A. F., Laufer, M. R. & Missmer, S. A. Spectrum of symptoms in women diagnosed with endometriosis during adolescence versus adulthood. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 218 , 324.e1–324.e11 (2018).

Ballard, K., Lane, H., Hudelist, G., Banerjee, S. & Wright, J. Can specific pain symptoms help in the diagnosis of endometriosis? A cohort study of women with chronic pelvic pain. Fertil. Steril. 94 , 20–27 (2010).

Becker, C. M., Gattrell, W. T., Gude, K. & Singh, S. S. Reevaluating response and failure of medical treatment of endometriosis: a systematic review. Fertil. Steril. 108 , 125–136 (2017).

Brawn, J., Morotti, M., Zondervan, K. T., Becker, C. M. & Vincent, K. Central changes associated with chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. Update 20 , 737–747 (2014).

Morotti, M., Vincent, K., Brawn, J., Zondervan, K. T. & Becker, C. M. Peripheral changes in endometriosis-associated pain. Hum. Reprod. Update 20 , 717–736 (2014).

Brosens, I., Gordts, S. & Benagiano, G. Endometriosis in adolescents is a hidden, progressive and severe disease that deserves attention, not just compassion. Hum. Reprod. 28 , 2026–2031 (2013).

Laufer, M. R., Sanfilippo, J. & Rose, G. Adolescent endometriosis: diagnosis and treatment approaches. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Gynecol. 16 , S3–S11 (2003).

Davis, G. D., Thillet, E. & Lindemann, J. Clinical characteristics of adolescent endometriosis. J. Adolesc. Health 14 , 362–368 (1993).

Saraswat, L. et al. Pregnancy outcomes in women with endometriosis: a national record linkage study. BJOG 124 , 444–452 (2017).

Sanchez, A. M. et al. Is the oocyte quality affected by endometriosis? A review of the literature. J. Ovarian Res. 10 , 43 (2017).

Simón, C. et al. Outcome of patients with endometriosis in assisted reproduction: results from in-vitro fertilization and oocyte donation. Hum. Reprod. 9 , 725–729 (1994).

Senapati, S., Sammel, M. D., Morse, C. & Barnhart, K. T. Impact of endometriosis on in vitro fertilization outcomes: an evaluation of the Society for Assisted Reproductive Technologies Database. Fertil. Steril. 106 , 164–171.e1 (2016).

Taniguchi, F. et al. Analysis of pregnancy outcome and decline of anti-Müllerian hormone after laparoscopic cystectomy for ovarian endometriomas. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 42 , 1534–1540 (2016).

Lessey, B. A. & Kim, J. J. Endometrial receptivity in the eutopic endometrium of women with endometriosis: it is affected, and let me show you why. Fertil. Steril. 108 , 19–27 (2017).

Miravet-Valenciano, J., Ruiz-Alonso, M., Gómez, E. & Garcia-Velasco, J. A. Endometrial receptivity in eutopic endometrium in patients with endometriosis: it is not affected, and let me show you why. Fertil. Steril. 108 , 28–31 (2017).

Díaz, I. et al. Impact of stage iii–iv endometriosis on recipients of sibling oocytes: matched case-control study. Fertil. Steril. 74 , 31–34 (2000).

Prapas, Y. et al. History of endometriosis may adversely affect the outcome in menopausal recipients of sibling oocytes. Reprod. Biomed. Online 25 , 543–548 (2012).

Burney, R. O. et al. Gene expression analysis of endometrium reveals progesterone resistance and candidate susceptibility genes in women with endometriosis. Endocrinology 148 , 3814–3826 (2007).

Dunselman, G. A. J. et al. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 29 , 400–412 (2014). This guideline discusses the management of general endometriosis .

Weijenborg, P. T. M., ter Kuile, M. M. & Jansen, F. W. Intraobserver and interobserver reliability of videotaped laparoscopy evaluations for endometriosis and adhesions. Fertil. Steril. 87 , 373–380 (2007).

Tuttlies, F. et al. ENZIAN-score, a classification of deep infiltrating endometriosis [German]. Zentralbl. Gynakol. 127 , 275–281 (2005).

Johnson, N. P. et al. World Endometriosis Society consensus on the classification of endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 32 , 315–324 (2017).

Nisolle, M. & Donnez, J. Peritoneal endometriosis, ovarian endometriosis, and adenomyotic nodules of the rectovaginal septum are three different entities. Fertil. Steril. 68 , 585–596 (1997).

Fukuda, S. et al. Thoracic endometriosis syndrome: comparison between catamenial pneumothorax or endometriosis-related pneumothorax and catamenial hemoptysis. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 225 , 118–123 (2018).

Rousset-Jablonski, C. et al. Catamenial pneumothorax and endometriosis-related pneumothorax: clinical features and risk factors. Hum. Reprod. 26 , 2322–2329 (2011).

Redwine, D. B. Ovarian endometriosis: a marker for more extensive pelvic and intestinal disease. Fertil. Steril. 72 , 310–315 (1999).

Hudelist, G. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound for non-invasive diagnosis of bowel endometriosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 37 , 257–263 (2011).

Holland, T. K. et al. Ultrasound mapping of pelvic endometriosis: does the location and number of lesions affect the diagnostic accuracy? A multicentre diagnostic accuracy study. BMC Womens Health 13 , 43 (2013).

Noventa, M. et al. Ultrasound techniques in the diagnosis of deep pelvic endometriosis: algorithm based on a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 104 , 366–383.e2 (2015).

Bazot, M. et al. European Society of Urogenital Radiology (ESUR) guidelines: MR imaging of pelvic endometriosis. Eur. Radiol. 27 , 2765–2775 (2016).

Exacoustos, C., Manganaro, L. & Zupi, E. Imaging for the evaluation of endometriosis and adenomyosis. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 28 , 655–681 (2014).

Stratton, P. Diagnostic accuracy of laparoscopy, magnetic resonance imaging, and histopathologic examination for the detection of endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 79 , 1078–1085 (2003).

Kennedy, S. et al. ESHRE guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of endometriosis. Hum. Reprod. 20 , 2698–2704 (2005).

Wykes, C. B., Clark, T. J. & Khan, K. S. REVIEW: Accuracy of laparoscopy in the diagnosis of endometriosis: a systematic quantitative review. BJOG 111 , 1204–1212 (2004).

Balasch, J. et al. Visible and non-visible endometriosis at laparoscopy in fertile and infertile women and in patients with chronic pelvic pain: a prospective study. Hum. Reprod. 11 , 387–391 (1996).

Lessey, B. A., Higdon, H. L., Miller, S. E. & Price, T. A. Intraoperative detection of subtle endometriosis: a novel paradigm for detection and treatment of pelvic pain associated with the loss of peritoneal integrity. J. Vis. Exp. https://doi.org/10.3791/4313 (2012).

Lue, J. R., Pyrzak, A. & Allen, J. Improving accuracy of intraoperative diagnosis of endometriosis: role of firefly in minimal access robotic surgery. J. Minim. Access Surg. 12 , 186–189 (2016).

Practice Committee of American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Treatment of pelvic pain associated with endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 90 , S260–S269 (2008). This article is a guideline for the management of pelvic pain associated with endometriosis .

Duffy, J. M. N. et al. Laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4 , CD011031 (2014).

Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Endometriosis and infertility: a committee opinion. Fertil. Steril. 98 , 591–598 (2012). This paper is a guideline for the management of infertility associated with endometriosis .

Tanbo, T. & Fedorcsak, P. Endometriosis-associated infertility: aspects of pathophysiological mechanisms and treatment options. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 96 , 659–667 (2017).

Osuga, Y. et al. Role of laparoscopy in the treatment of endometriosis-associated infertility. Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 53 , 33–39 (2002).

Hart, R. J., Hickey, M., Maouris, P., Buckett, W. & Garry, R. Excisional surgery versus ablative surgery for ovarian endometriomata. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004992.pub2 (2005).

Benaglia, L. et al. Rate of severe ovarian damage following surgery for endometriomas. Hum. Reprod. 25 , 678–682 (2010).

Vercellini, P. et al. Effect of patient selection on estimate of reproductive success after surgery for rectovaginal endometriosis: literature review. Reprod. Biomed. Online 24 , 389–395 (2012).

Nyangoh Timoh, K., Ballester, M., Bendifallah, S., Fauconnier, A. & Darai, E. Fertility outcomes after laparoscopic partial bladder resection for deep endometriosis: retrospective analysis from two expert centres and review of the literature. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 220 , 12–17 (2018).

Adamson, G. D. & Pasta, D. J. Endometriosis fertility index: the new, validated endometriosis staging system. Fertil. Steril. 94 , 1609–1615 (2010).

Werbrouck, E., Spiessens, C., Meuleman, C. & D’Hooghe, T. No difference in cycle pregnancy rate and in cumulative live-birth rate between women with surgically treated minimal to mild endometriosis and women with unexplained infertility after controlled ovarian hyperstimulation and intrauterine insemination. Fertil. Steril. 86 , 566–571 (2006).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Fertility problems: assessment and treatment. NICE https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg156/chapter/Recommendations#intrauterine-insemination (2013).

de Ziegler, D., Borghese, B. & Chapron, C. Endometriosis and infertility: pathophysiology and management. Lancet 376 , 730–738 (2010).

Steures, P. et al. Prediction of an ongoing pregnancy after intrauterine insemination. Fertil. Steril. 82 , 45–51 (2004).

Reindollar, R. H. et al. A randomized clinical trial to evaluate optimal treatment for unexplained infertility: the fast track and standard treatment (FASTT) trial. Fertil. Steril. 94 , 888–899 (2010).

Eijkemans, M. J. C. et al. Cost-effectiveness of ‘immediate IVF’ versus ‘delayed IVF’: a prospective study. Hum. Reprod. 32 , 999–1008 (2017).

Hamdan, M., Omar, S. Z., Dunselman, G. & Cheong, Y. Influence of endometriosis on assisted reproductive technology outcomes. Obstet. Gynecol. 125 , 79–88 (2015).

Benschop, L., Farquhar, C., van der Poel, N. & Heineman, M. J. Interventions for women with endometrioma prior to assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 11 , CD008571 (2010).

de Ziegler, D. et al. Use of oral contraceptives in women with endometriosis before assisted reproduction treatment improves outcomes. Fertil. Steril. 94 , 2796–2799 (2010).

Donnez, J., García-Solares, J. & Dolmans, M.-M. Fertility preservation in women with ovarian endometriosis. Minerva Ginecol. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0026-4784.18.04229-6 (2018).

Somigliana, E. et al. Surgical excision of endometriomas and ovarian reserve: a systematic review on serum antimüllerian hormone level modifications. Fertil. Steril. 98 , 1531–1538 (2012).

Bianchi, P. H. M. et al. Extensive excision of deep infiltrative endometriosis before in vitro fertilization significantly improves pregnancy rates. J. Minim. Invasive Gynecol. 16 , 174–180 (2009).

Zullo, F. et al. Endometriosis and obstetrics complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fertil. Steril. 108 , 667–672.e5 (2017).

Vigano, P., Corti, L. & Berlanda, N. Beyond infertility: obstetrical and postpartum complications associated with endometriosis and adenomyosis. Fertil. Steril. 104 , 802–812 (2015).

Donnez, J. & Squifflet, J. Complications, pregnancy and recurrence in a prospective series of 500 patients operated on by the shaving technique for deep rectovaginal endometriotic nodules. Hum. Reprod. 25 , 1949–1958 (2010).

Zanelotti, A. & Decherney, A. H. Surgery and endometriosis. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 60 , 477–484 (2017).

Olive, D. L. Medical therapy of endometriosis. Semin. Reprod. Med. 21 , 209–222 (2003).

Harada, T., Momoeda, M., Taketani, Y., Hoshiai, H. & Terakawa, N. Low-dose oral contraceptive pill for dysmenorrhea associated with endometriosis: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial. Fertil. Steril. 90 , 1583–1588 (2008).

Vercellini, P. et al. Treatment of symptomatic rectovaginal endometriosis with an estrogen–progestogen combination versus low-dose norethindrone acetate. Fertil. Steril. 84 , 1375–1387 (2005).

Harada, T. et al. Dienogest is as effective as intranasal buserelin acetate for the relief of pain symptoms associated with endometriosis — a randomized, double-blind, multicenter, controlled trial. Fertil. Steril. 91 , 675–681 (2009).

Casper, R. F. Progestin-only pills may be a better first-line treatment for endometriosis than combined estrogen-progestin contraceptive pills. Fertil. Steril. 107 , 533–536 (2017).

Abou-Setta, A. M., Houston, B., Al-Inany, H. G. & Farquhar, C. Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) for symptomatic endometriosis following surgery. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 1 , CD005072 (2013).

Brown, J., Pan, A. & Hart, R. J. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogues for pain associated with endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 12 , CD008475 (2010).

Sagsveen, M. et al. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogues for endometriosis: bone mineral density. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4 , CD001297 (2003).

Bedaiwy, M. A., Allaire, C. & Alfaraj, S. Long-term medical management of endometriosis with dienogest and with a gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonist and add-back hormone therapy. Fertil. Steril. 107 , 537–548 (2017).

Taylor, H. S. et al. Treatment of endometriosis-associated pain with elagolix, an oral GnRH antagonist. N. Engl. J. Med. 377 , 28–40 (2017).

Hornstein, M. D. An oral GnRH antagonist for endometriosis — a new drug for an old disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 377 , 81–83 (2017).

Bedaiwy, M. A., Alfaraj, S., Yong, P. & Casper, R. New developments in the medical treatment of endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 107 , 555–565 (2017).

Shakiba, K., Bena, J. F., McGill, K. M., Minger, J. & Falcone, T. Surgical treatment of endometriosis. Obstet. Gynecol. 111 , 1285–1292 (2008).

Vercellini, P. Laparoscopic uterosacral ligament resection for dysmenorrhea associated with endometriosis: results of a randomized, controlled trial. Fertil. Steril. 68 , S3 (1997).

Meuleman, C. et al. Surgical treatment of deeply infiltrating endometriosis with colorectal involvement. Hum. Reprod. Update 17 , 311–326 (2011).

Koga, K., Takamura, M., Fujii, T. & Osuga, Y. Prevention of the recurrence of symptom and lesions after conservative surgery for endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 104 , 793–801 (2015).

Gao, X. et al. Health-related quality of life burden of women with endometriosis: a literature review. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 22 , 1787–1797 (2006).

Simoens, S. et al. The burden of endometriosis: costs and quality of life of women with endometriosis and treated in referral centres. Hum. Reprod. 27 , 1292–1299 (2012). This prospective study calculates the average annual costs and HRQOL per woman with endometriosis-associated symptoms, showing it to be similar to other chronic conditions .

Jones, G., Kennedy, S., Barnard, A., Wong, J. & Jenkinson, C. Development of an endometriosis quality-of-life instrument. Obstet. Gynecol. 98 , 258–264 (2001). This study describes the only validated endometriosis-specific quality-of-life outcome tool developed, measuring endometriosis-related health status on five scales. The tool has since been shown to be sensitive to changes in symptoms, making it a useful tool in endometriosis-specific clinical trials .

Jones, G., Jenkinson, C. & Kennedy, S. Development of the short form endometriosis health profile questionnaire: the EHP-5. Qual. Life Res. 13 , 695–704 (2004).

Jones, G., Jenkinson, C. & Kennedy, S. Evaluating the responsiveness of the endometriosis health profile questionnaire: the EHP-30. Qual. Life Res. 13 , 705–713 (2004).

Hirsch, M. et al. Variation in outcome reporting in endometriosis trials: a systematic review. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 214 , 452–464 (2016).

Khan, K. The CROWN Initiative: journal editors invite researchers to develop core outcomes in women’s health. BJOG 123 , 103–104 (2016).

van Nooten, F. E., Cline, J., Elash, C. A., Paty, J. & Reaney, M. Development and content validation of a patient-reported endometriosis pain daily diary. Health Qual. Life Outcomes 16 , 3 (2018).

Rogers, P. A. W. et al. Research priorities for endometriosis. Reprod. Sci. 24 , 202–226 (2017).

Butrick, C. W. Patients with chronic pelvic pain: endometriosis or interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome? JSLS 11 , 182–189 (2007).

Sørlie, T. et al. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100 , 8418–8423 (2003).

Cancer Genome Atlas Network. et al. Comprehensive molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature 490 , 61–70 (2012).

Gupta, D. et al. Endometrial biomarkers for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 4 , CD012165 (2016).

Nisenblat, V. et al. Combination of the non-invasive tests for the diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 7 , CD012281 (2016).

Nisenblat, V., Bossuyt, P. M. M., Farquhar, C., Johnson, N. & Hull, M. L. Imaging modalities for the non-invasive diagnosis of endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2 , CD009591 (2016).

May, K. E. et al. Peripheral biomarkers of endometriosis: a systematic review. Hum. Reprod. Update 16 , 651–674 (2010).

May, K. E., Villar, J., Kirtley, S., Kennedy, S. H. & Becker, C. M. Endometrial alterations in endometriosis: a systematic review of putative biomarkers. Hum. Reprod. Update 17 , 637–653 (2011).

van der Zanden, M. & Nap, A. W. Knowledge of, and treatment strategies for, endometriosis among general practitioners. Reprod. Biomed. Online 32 , 527–531 (2016).

Seear, K. The etiquette of endometriosis: stigmatisation, menstrual concealment and the diagnostic delay. Soc. Sci. Med. 69 , 1220–1227 (2009).

Greene, R., Stratton, P., Cleary, S. D., Ballweg, M. L. & Sinaii, N. Diagnostic experience among 4,334 women reporting surgically diagnosed endometriosis. Fertil. Steril. 91 , 32–39 (2009).

Horne, A. W., Saunders, P. T. K., Abokhrais, I. M. & Hogg, L. Top ten endometriosis research priorities in the UK and Ireland. Lancet 389 , 2191–2192 (2017).

Hans Evers, J. L. H. Is adolescent endometriosis a progressive disease that needs to be diagnosed and treated? Hum. Reprod. 28 , 2023 (2013).

Neal, D. M. & McKenzie, P. J. Putting the pieces together: endometriosis blogs, cognitive authority, and collaborative information behavior. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 99 , 127–134 (2011).

Uno, S. et al. A genome-wide association study identifies genetic variants in the CDKN2BAS locus associated with endometriosis in Japanese. Nat. Genet. 42 , 707–710 (2010).

Painter, J. N. et al. Genome-wide association study identifies a locus at 7p15.2 associated with endometriosis. Nat. Genet. 43 , 51–54 (2011).

Albertsen, H. M., Chettier, R., Farrington, P. & Ward, K. Genome-wide association study link novel loci to endometriosis. PLoS ONE 8 , e58257 (2013).

Steinthorsdottir, V. et al. Common variants upstream of KDR encoding VEGFR2 and in TTC39B associate with endometriosis. Nat. Commun. 7 , 12350 (2016).

Sobalska-Kwapis, M. et al. New variants near RHOJ and C2, HLA-DRA region and susceptibility to endometriosis in the Polish population — the genome-wide association study. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 217 , 106–112 (2017).

Download references

Acknowledgements

R.N.T. acknowledges funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development through grants R01-HD33238, U54-HD37321, U54-HD55787, R01-HD55379, U01-HD66439 and R21-HD78818. S.A.M. is also affiliated with the Boston Center for Endometriosis, Boston Children’s Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Division of Adolescent and Young Adult Medicine, Department of Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School. The authors thank N. Moore (Oxford University Hospitals Foundation Trust, UK) for providing MRI images, D. Barber (Oxford Endometriosis CaRe Centre, UK) for providing ultrasonography pictures and J. Malzahn (Nuffield Department of Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences, University of Oxford, UK) for providing the picture of the histology slide in Fig. 5.

Reviewer information

Nature Reviews Disease Primers thanks I. Brosens, M. J. Canis, S. Ferrero, C. Nezhat, V. Remorgida, M. Simões Abrão and other anonymous referee(s) for the peer review of this work.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Oxford Endometriosis CaRe Centre, Nuffield Department of Women’s & Reproductive Health, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Krina T. Zondervan & Christian M. Becker

Wellcome Centre for Human Genetics, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Krina T. Zondervan

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan

Department of Epidemiology, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA

Stacey A. Missmer

Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, College of Human Medicine, Michigan State University, Grand Rapids, MI, USA

Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Utah School of Medicine, Salt Lake City, UT, USA

Robert N. Taylor

Division of Genetics and Cell Biology, San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milano, Italy

Paola Viganò

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Introduction (K.T.Z.); Epidemiology (S.A.M.); Mechanisms/pathophysiology (R.N.T. and P.V.); Diagnosis, screening and prevention (C.M.B.); Management (K.K.); Quality of life (K.T.Z.); Outlook (K.T.Z.); Overview of the Primer (K.T.Z.).

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Krina T. Zondervan .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

K.T.Z. has received grant funding from the Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council UK, the US NIH, the European Union and the World Endometriosis Research Foundation (WERF). She also has scientific collaborations with, and has received grant funding from, Bayer AG, MDNA Life Sciences, Roche Diagnostics and Volition Rx and has served as a scientific consultant to AbbVie and Roche Diagnostics. She is Secretary of the World Endometriosis Society (WES), the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology (ESHRE) Special Interest Group in Endometriosis and Endometrial Disorders and Wellbeing of Women, and she is Chair of the WES Research Directions Working Group. C.M.B. is a member of the independent data monitoring group for a clinical endometriosis trial by ObsEva. He has received research grants from Bayer AG, MDNA Life Sciences, Volition Rx and Roche Diagnostics as well as from Wellbeing of Women, Medical Research Council UK, the NIH, the UK National Institute for Health Research and the European Union. He is the current Chair of the Endometriosis Guideline Development Group of the ESHRE and was a co-opted member of the Endometriosis Guideline Group by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). K.K. has received grant funding from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports Science and Technology Japan, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Japan, Takeda Research Support and MSD. She has also served as a scientific consultant to Bayer AG. She is an ambassador of the WES and a member of the Guideline Development Group of the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. S.A.M. has received grant funding from the NIH and the Marriott family foundations and has served as an adviser to and has scientific collaborations with AbbVie, Celmatix and Oratel Diagnostics. She is a treasurer of the WES, Secretary of the WERF, Chair of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine Endometriosis Special Interest Group and a member of the NIH Reproductive Medicine Network Data Safety and Monitoring Board. R.N.T. has received grant funding from Bayer AG, Ferring Research Institute, the NIH and Pfizer and has served as a scientific consultant or adviser to AbbVie, Allergan, the NIH, ObsEva SA and the Population Council. He is the immediate past honorary secretary of the WES. P.V. has received grant funding from Bayer AG and Merck Serono and has served as a scientific consultant to Ferring Pharmaceuticals and Roche Diagnostics. She is a board member of the WES.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Related links

WERF Endometriosis Phenome and Biobanking Harmonisation Project: https://endometriosisfoundation.org/ephect/

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Zondervan, K.T., Becker, C.M., Koga, K. et al. Endometriosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 4 , 9 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-018-0008-5

Download citation

Published : 19 July 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41572-018-0008-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Impact of oil-based contrast agents in hysterosalpingography on fertility outcomes in endometriosis: a retrospective cohort study.

- Yingqin Huang

Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology (2024)

Efficacy and safety of a novel pain management device, AT-04, for endometriosis-related pain: study protocol for a phase III randomized controlled trial

- Hiroshi Ishikawa

- Osamu Yoshino

Reproductive Health (2024)

Surge in endometriosis research after decades of underfunding could herald new era for women’s health

- Clare Watson

Nature Medicine (2024)

Mining phase separation-related diagnostic biomarkers for endometriosis through WGCNA and multiple machine learning techniques: a retrospective and nomogram study

- Qiuyi Liang

- Shengmei Yang

Journal of Assisted Reproduction and Genetics (2024)

The roles of chromatin regulatory factors in endometriosis

Quick links.

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Pathophysiology,...

Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of endometriosis

- Related content

- Peer review

- Andrew W Horne , professor of gynaecology and reproductive sciences 1 ,

- Stacey A Missmer , professor of obstetrics, gynaecology, and reproductive biology , adjunct professor of epidemiology 2 3

- 1 EXPPECT Edinburgh and MRC Centre for Reproductive Health, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

- 2 Michigan State University, Grand Rapids, MI, USA

- 3 Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA

- Correspondence to: A W Horne andrew.horne{at}ed.ac.uk

Endometriosis affects approximately 190 million women and people assigned female at birth worldwide. It is a chronic, inflammatory, gynecologic disease marked by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, which in many patients is associated with debilitating painful symptoms. Patients with endometriosis are also at greater risk of infertility, emergence of fatigue, multisite pain, and other comorbidities. Thus, endometriosis is best understood as a condition with variable presentation and effects at multiple life stages. A long diagnostic delay after symptom onset is common, and persistence and recurrence of symptoms despite treatment is common. This review discusses the potential genetic, hormonal, and immunologic factors that lead to endometriosis, with a focus on current diagnostic and management strategies for gynecologists, general practitioners, and clinicians specializing in conditions for which patients with endometriosis are at higher risk. It examines evidence supporting the different surgical, pharmacologic, and non-pharmacologic approaches to treating patients with endometriosis and presents an easy to adopt step-by-step management strategy. As endometriosis is a multisystem disease, patients with the condition should ideally be offered a personalized, multimodal, interdisciplinary treatment approach. A priority for future discovery is determining clinically informative sub-classifications of endometriosis that predict prognosis and enhance treatment prioritization.

Introduction

Endometriosis is a chronic, inflammatory, gynecologic disease marked by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, which affects approximately 10% of women during their reproductive years—190 million women worldwide. 1 In many patients, it is associated with chronic painful symptoms and other comorbidities, including infertility. 2 The health burden of endometriosis includes chronic pain and significant lifetime costs of $27 855 per year per patient, 3 accumulating to annual healthcare costs for endometriosis of approximately $22bn in the US alone and £12.5bn in the UK in treatment, work loss, and healthcare costs. 4 Although more than 50% of adults diagnosed as having endometriosis report onset of severe pelvic pain during adolescence, 5 most young women with endometriosis do not receive timely treatment. Almost 60% of women will see three or more clinicians before a diagnosis of endometriosis is made after an average of seven years with symptoms. 6 Women with endometriosis lose on average 11 hours of work per week, similar to other chronic conditions including type 2 diabetes, Crohn’s disease, and rheumatoid arthritis. 7 Adolescents are at risk of having inadequately remediated symptoms during prime years for social development and life planning, 8 and women must be resilient against inadequately remediated symptoms and emerging comorbidities. Women, healthcare providers, and scientists would benefit from conceptualizing endometriosis as a condition that can affect the whole woman. This includes a better understanding of the risk of subsequent development of autoimmune disease, cancer, and cardiovascular disease and a whole health approach to monitoring and wellbeing. 9

This review is aimed at general practitioners and pediatric specialists who are most likely to interact with patients as signs and symptoms of endometriosis first emerge and from whom early attention and empiric treatment may dramatically shorten the burden; gynecology specialists for whom myths must be dispelled and who must be aware of state of the art knowledge about patient centered treatments; endometriosis specialists who care for women’s endometriosis associated symptoms across the life course; and clinical researchers and scientists who must be inspired to bring their expertise and creativity to answer the fundamental enigmas of endometriosis etiology, informative sub-phenotyping, and novel patient centered treatment.

In this review, we use the terms “woman” and “women.” However, it is important to note that endometriosis can affect all people assigned female at birth.

Sources and selection criteria

We searched PubMed for studies using the term “endometriosis.” We considered all peer reviewed studies published in the English language between 1 January 2010 and 28 February 2022. We also identified references from international guidelines on endometriosis published during this time period. We selected relevant publications outside this timeline on the basis of review of the bibliography. We predefined the priority of study selection for this review according to the level of the evidence (meta-analyses, systematic or scoping reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), prospective cohort studies, case-control studies, cross sectional studies; a priori exclusion of case series and case reports), by sample size (we prioritized studies with larger sample size as well as studies providing precision statistics), by population sampling (we prioritized studies with more diverse populations or with declared sub-population design over narrow population samples), and publication date (we prioritized more recent studies).

Overall quality of evidence

Much of the knowledge on endometriosis is based on concepts in early stages of evidence development or on sparse literature. Many studies include single hospital or clinic population samples with small total sample sizes and disproportionately representing patients presenting with infertility compared with endometriosis associated pain. 10

Beyond the limitations of the existing literature, fundamental problems with the diagnosis of endometriosis must be overcome before we can adequately define endometriosis, its prevalence, biologically and clinically informative sub-phenotypes, and its response to treatment and long term prognosis. 11 The lack of a non-invasive diagnostic modality creates insurmountable diagnostic biases driven by characteristics of those patients who can and those who cannot access a definitive surgical or imaging diagnosis and at what point in their endometriosis journey the condition is diagnosed.

Ovarian endometrioma or deep endometriosis can be diagnosed through imaging if the patient is geographically, economically, and socially able to achieve referral to and evaluation from an experienced imaging specialist. 12 13 For women with superficial peritoneal disease, definitive diagnosis by means of surgical evaluation is limited to those with symptoms deemed sufficiently severe and life affecting and resistant to empiric treatment to justify the inherent risks of surgery. Even among patients with symptoms deemed to have enough of an effect to warrant referral for a surgical evaluation, stigma, 14 disbelief and misperceptions of pain or fertility that can be driven by racism or elitism, 15 and geographic and economic barriers to accessing endometriosis focused surgeons remain.

Beyond access to an appropriate, skilled physician, the wide range of symptoms associated with endometriosis—many of which are stigmatized or normalized 14 16 —reduces the likelihood of referral and increases time to referral to appropriate specialists. 5 6 11 17 The bias in diagnosis itself may be influenced by variations in clinical symptoms among different populations not adequately captured or appreciated by standard clinical definitions or may represent implicit bias in healthcare, leading to an alternate interpretation of the same symptoms affecting the likelihood of diagnosis. This delay to diagnosis affects patients directly, but it also results in most scientific studies capturing patients’ characteristics, biologic samples, and biomarker measurements far into the natural pathophysiologic progression of the disease. Moreover, studies from African and Asian countries are considerably under-represented compared with European and North American countries. 10 High quality studies from these regions and development of a sensitive non-invasive diagnostic tool might alter existing global prevalence and incidence estimates and may reveal a more comprehensive view of what early milieu, signs and symptoms, and long term health outcomes are truly attributable to endometriosis.

Definition, symptoms, and classification

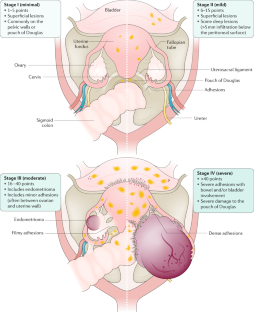

Among women with the condition, endometriosis has a highly heterogeneous presentation of visualized endometriotic lesions, multisystem symptom presentation, and comorbid conditions ( fig 1 ).

Highly varied presentation of endometriosis

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Surgically visualized macro sub-phenotypes of endometriosis

Endometriosis is defined by the presence of endometrium-like epithelium and/or stroma (lesions) outside the endometrium and myometrium, usually with an associated inflammatory process. 18 Most endometriosis is found within the abdominal cavity, and it exists as three subtypes: superficial peritoneal endometriosis (accounting for around 80% of endometriosis), ovarian endometriosis (cysts or “endometrioma”), and deep endometriosis 1 19 ( box 1 ; fig 2 ). All forms of endometriosis can be found together, not solely as separate entities. Although not a subtype, endometriosis situated inside the bowel wall is termed “bowel endometriosis.” It mostly affects the rectosigmoid area, but lesions can also be found in other parts of the gastrointestinal system, including the appendix. Endometriosis involving the detrusor muscle and/or the bladder epithelium is termed “bladder endometriosis.” Extra-abdominal (replacing the older term “extra-pelvic”) endometriosis is used to describe any endometriosis lesions found outside of the abdomen (for example, thoracic endometriosis). 20 Iatrogenic endometriosis describes endometriosis thought to be arising from direct or indirect dissemination of endometrium following surgery (for example, cesarean scar endometriosis).

Nomenclature 18

Superficial peritoneal endometriosis.

Endometrium-like tissue lesions involving the peritoneal surface with multiple appearances

Ovarian endometriosis

Endometrium-like tissue lesions in the form of ovarian cysts containing endometrium-like tissue and dark blood stained fluid (endometrioma or “chocolate cysts”)

Deep endometriosis

Endometrium-like tissue lesions extending on or infiltrating the peritoneal surface (usually nodular, invading into adjacent structures, and associated with fibrosis)

Extra-abdominal endometriosis

Endometrium-like tissue outside the abdominal cavity (for example, thoracic, umbilical, brain endometriosis)

Iatrogenic endometriosis

Direct or indirect dissemination of endometrium following surgery (for example, cesarean scar endometriosis)

Surgical images of endometriosis sub-phenotypes

Adenomyosis is not a sub-phenotype of endometriosis, 21 although it is characterized by endometrial tissue surrounded by smooth muscle cells within the myometrium. 22 Symptoms include dysmenorrhea and heavy menstrual and/or abnormal uterine bleeding, 23 and a heterogeneous adenomyosis presentation is visualized with radiologic imaging or at hysterectomy that lacks an agreed terminology or classification system. 24 25 Evidence is emerging of tissue injury and repair mechanisms mediated by estradiol and inflammation. 25 26

Endometriosis associated symptoms

Endometriosis is often associated with a range of painful symptoms that include chronic pelvic pain (cyclical and non-cyclical), painful periods (dysmenorrhea), painful sex (dyspareunia), and pain on defecation (dyschezia) and urination (dysuria). 1 27 Their severity can range from mild to debilitating. Some women have no symptoms, others have episodic pelvic pain, and still others experience constant pain in multiple body regions. 28 A related observation is that some women transition between these categories, progressing from episodic and localized pain to that which is chronic, complex, and more difficult to treat. Furthermore, women with disease that is anatomically “severe” can have minimal symptoms and women with “minimal” evidence of endometriosis can have severe, life affecting symptoms. 1 19 In common with other chronic pain conditions, women with endometriosis often report experiencing fatigue and depression. Infertility is significantly more common in patients with endometriosis, with a doubling of risk compared with women without endometriosis. 2 Endometriosis is discovered in 30-50% of women who present for assisted reproductive treatment. 29 30

Endometriosis associated or high risk comorbidities

Endometriosis is certainly a multisystem condition, perhaps as a result of common pathogenesis or as a consequence of the chronic endogenous response to the presence of endometriotic lesions. 9 Although pelvic pain is the most common symptom of possible endometriosis, women with endometriosis also have a high risk of co-occurring or evolving multisite pain. 28 Patients with endometriosis have a higher risk of presentation with comorbid chronic pain conditions such as fibromyalgia, 31 32 33 migraines, 34 35 and also rheumatoid arthritis, 33 36 psoriatic arthritis, 37 and osteoarthritis. 36 38 Reports of back, bladder, or bowel pain are prevalent, 16 39 with dyschezia being potentially predictive of endometriosis. 40 Nearly 50% of women with bladder pain syndrome or interstitial cystitis have endometriosis. 41 42 Irritable bowel syndrome is a common co-occurring diagnosis that reinforces the importance of awareness of endometriosis among gastroenterologists. 43 44 45 These conditions may share a common cause, 46 they may arise together owing to shared environmental or genetic factors, and/or the occurrence of comorbid pain conditions could be due to changes in pain perception after repeated sensitization. 47 Research focused on disentangling the overlapping and independent pathways of these frequently co-occurring pain associated conditions is essential. 48 49

Women with endometriosis have a greater risk of presenting with other non-malignant gynecologic diseases, including uterine fibroids and adenomyosis. 50 51 They are also at greater risk of a subsequent diagnosis of malignancies, autoimmune diseases, early natural menopause, and cerebrovascular and cardiovascular conditions. 36 52 53 54 55 56 57 The hypothesized causal mechanisms for endometriosis discussed below are all thought to be enhanced by and/or result in chronic inflammation. Local and systemic chronic inflammation can directly activate afferent nociceptive fibers and promote pelvic pain, 58 although this does not entirely explain the heterogeneity in types and severity of painful symptoms that patients experience. Furthermore, endometriosis induced chronic inflammation and immune dysregulation may also contribute to the endometriosis associated subsequent risk of each of these comorbid conditions. 59 60

Although this multisystem effect reinforces the importance of knowledge of and attention to endometriosis from general practitioners and a myriad specialists for whole healthcare, the most prominent association, and the focus of the greatest volume of comorbidity research, is the elevated risk of ovarian cancer among women with endometriosis. A recent meta-analysis confirmed this association, 53 finding a nearly twofold greater relative risk of ovarian cancer among patients with endometriosis (summary relative risk (SRR) 1.93, 95% confidence interval 1.68 to 2.22; n=24 studies) that was strongest for clear cell (3.44, 2.82 to 4.42; n=5 studies) and endometrioid (2.33, 1.82 to 2.98; n=5 studies) histotypes. However, among these 24 studies, significant evidence existed of both heterogeneity across studies and publication bias (Egger’s and Begg’s P values <0.01). Clinicians need to reinforce that ovarian cancer is rare regardless of women’s endometriosis status 61 : the absolute lifetime risk in the general population is 1.3%, 62 and applying the risk estimate from the meta-analysis (SRR 1.9) gives an absolute lifetime risk for women with endometriosis of 2.5%, which is 1.2% higher than the absolute risk for women without endometriosis and still very low.

We should also recognize that coexisting gynecologic conditions such as adenomyosis and uterine fibroids, 50 as well as associations with endometrial cancer, 53 can be influenced by diagnostic biases and failure to distinguish between diagnoses in women undergoing hysterectomy and those in women with an intact uterus. 11 51 When attempting to infer a causal relation between endometriosis and other conditions, applying rigorous prospective temporality (rather than cross sectional co-occurrence) is particularly important for valid subsequent risk associations. 53 These studies need large study populations with well documented longitudinal data. A large impediment is the lack of routine, harmonized documentation of the characteristics of endometriosis and its absence from international classification of diseases coding. 63 64

Endometriosis classification systems

Several classification, staging, and reporting systems have been developed; 22 systems were published between 1973 and 2021. 65 The three most commonly used systems are the revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine (rASRM) classification (stages I-IV; where stage I is equivalent to “minimal” disease and stage 4 to “severe” disease), the ENZIAN (and newer #ENZIAN) classification, and the Endometriosis Fertility Index (EFI). 66 67 68 69 Many validation studies and reports on the implementation of the different systems have been published. The rASRM system (scored at surgery on the basis of the extent of visualized superficial peritoneal lesions, endometriomas, and adhesions) has been shown to have poor correlation with pain, 70 fertility outcomes, and prognosis, and the ENZIAN system (which additionally includes deep endometriosis) has been shown to have poor correlation with symptoms and infertility. 71 72 73 The EFI is a well validated clinical tool that predicts pregnancy rates after surgical staging of endometriosis, with ongoing evaluation to determine the predictive importance of the individual parameters included in the scoring algorithm as well as the effect of completeness of surgical treatment on pregnancy prediction. 74 Unfortunately, no international agreement exists on how to describe endometriosis or how to classify it. As most systems show no, or very little, correlation with patients’ symptoms and outcomes, this is further evidence of our lack of understanding of the physiology underlying the symptoms associated with endometriosis.

Epidemiology

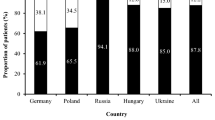

The exact prevalence of endometriosis is unknown given diagnostic delays and barriers, and—perhaps consequently—it is extremely varied depending on the population and the indication for evaluation. A recent meta-analysis identified 69 studies describing the prevalence and/or incidence of endometriosis, among which 26 studies were general population samples, 17 were from regional/national hospitals or insurance claims systems, and the remaining 43 studies were conducted in single clinic or hospital settings. 10 The prevalence reported in general population studies ranged from 0.7% to 8.6%, whereas that reported in single clinic or hospital based studies ranged from 0.2% to 71.4%.

When defined by indications for diagnosis, the prevalence of endometriosis ranged from 15.4% to 71.4% among women with chronic pelvic pain, from 9.0% to 68.0% among women presenting with infertility, and from 3.7% to 43.3% among women undergoing tubal sterilization. Few studies have investigated the incidence and prevalence of endometriosis specifically among adolescents. The reported prevalence of visually confirmed endometriosis among adolescents with pelvic pain ranges from 25% to 100%, with an average of 49% among adolescents with chronic pelvic pain and 75% among those unresponsive to medical treatment. 75 The Ghiasi meta-analysis reported a decrease in recorded prevalence across the past 30 years. 10 Speculating, this may be due to more rapid and more ubiquitous embracing of empiric treatment of symptom, forgoing or delaying definitive imaging or surgical diagnosis, a patient centered approach that has been ratified by the most recent European endometriosis guideline. 13 This hypothesis is supported by a recent report from a large US health system’s electronic medical records database that observed a decline from 2006 through 2015 in incidence rates for endometriosis (from 30.2 per 10 000 person years in 2006 to 17.4 per 10 000 person years in 2015) but an increase in documentation of chronic pelvic pain diagnoses (from 3.0% to 5.6%). 76

Pathophysiology

Heritability and genetics.

Estimates from twin studies suggest 47-51% total heritability of endometriosis, with 26% estimated to be from genetic variation. 77 78 79 To date, nine genome-wide association studies have been reported. 59 The largest study so far, using 17 045 cases and 191 596 controls, has identified 19 single nucleotide polymorphisms, most of which were more strongly associated with rASRM stage III/IV, rather than stage I/II, explaining 1.75% of risk for endometriosis. 80 Consistent with other complex diseases with multifactorial origins, no high penetrance susceptibility genes for endometriosis have yet been identified. 62 The loci discovered to date are almost all located in intergenic regions that are known to play a role in the regulation of expression of target genes yet to be identified. The critical next steps in genetic discovery are to identify additional genes that reveal novel pathophysiological pathways and also emerge to better define the underpinnings of variation in symptoms (in particular, pain types and infertility and treatment response predictors) and also gene expression correlated with comorbid autoimmune, cancer, and cardiovascular conditions. 62