- Did You Know?

- Photo Gallery

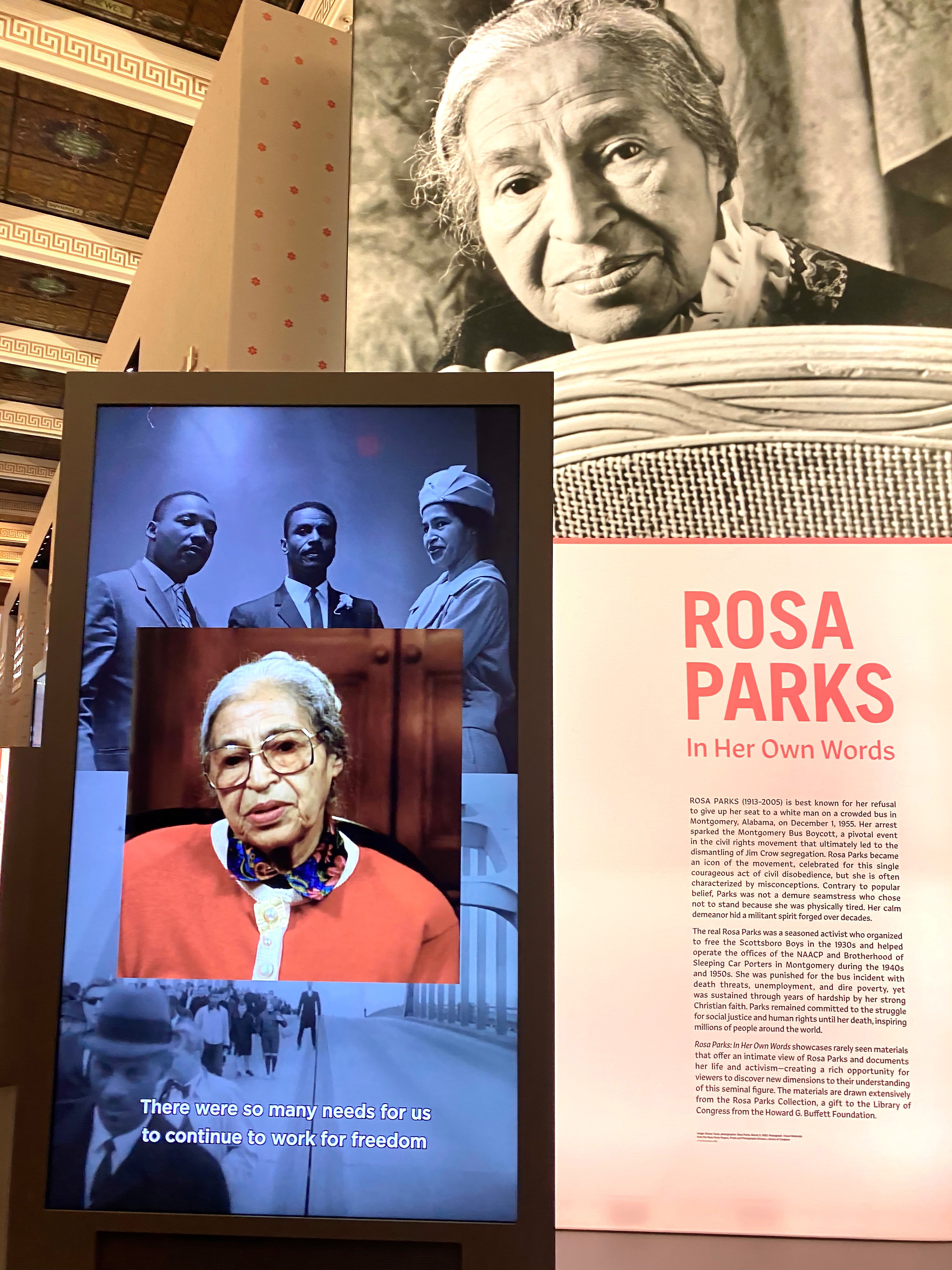

ROSA LOUISE PARKS BIOGRAPHY

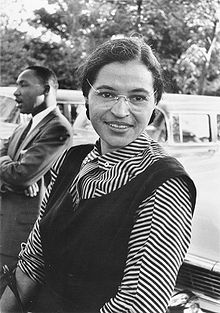

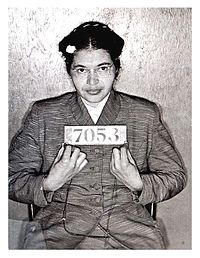

Rosa Louise Parks was nationally recognized as the “mother of the modern day civil rights movement” in America. Her refusal to surrender her seat to a white male passenger on a Montgomery, Alabama bus, December 1, 1955, triggered a wave of protest December 5, 1955 that reverberated throughout the United States. Her quiet courageous act changed America, its view of black people and redirected the course of history.

Mrs. Parks was born Rosa Louise McCauley, February 4, 1913 in Tuskegee, Alabama. She was the first child of James and Leona Edwards McCauley. Her brother, Sylvester McCauley, now deceased, was born August 20, 1915. Later, the family moved to Pine Level, Alabama where Rosa was reared and educated in the rural school. When she completed her education in Pine Level at age eleven, her mother, Leona, enrolled her in Montgomery Industrial School for Girls (Miss White’s School for Girls), a private institution. After finishing Miss White’s School, she went on to Alabama State Teacher’s College High School. She, however, was unable to graduate with her class, because of the illness of her grandmother Rose Edwards and later her death.

As Rosa Parks prepared to return to Alabama State Teacher’s College, her mother also became ill, therefore, she continued to take care of their home and care for her mother while her brother, Sylvester, worked outside of the home. She received her high school diploma in 1934, after her marriage to Raymond Parks, December 18, 1932. Raymond, now deceased was born in Wedowee, Alabama, Randolph County, February 12, 1903, received little formal education due to racial segregation. He was a self-educated person with the assistance of his mother, Geri Parks. His immaculate dress and his thorough knowledge of domestic affairs and current events made most think he was college educated. He supported and encouraged Rosa’s desire to complete her formal education.

Mr. Parks was an early activist in the effort to free the “Scottsboro Boys,” a celebrated case in the 1930′s. Together, Raymond and Rosa worked in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP’s) programs. He was an active member and she served as secretary and later youth leader of the local branch. At the time of her arrest, she was preparing for a major youth conference.

After the arrest of Rosa Parks, black people of Montgomery and sympathizers of other races organized and promoted a boycott of the city bus line that lasted 381 days. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was appointed the spokesperson for the Bus Boycott and taught nonviolence to all participants. Contingent with the protest in Montgomery, others took shape throughout the south and the country. They took form as sit-ins, eat-ins, swim-ins, and similar causes. Thousands of courageous people joined the “protest” to demand equal rights for all people.

Mrs. Parks moved to Detroit, Michigan in 1957. In 1964 she became a deaconess in the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME).

Congressman John Conyers First Congressional District of Michigan employed Mrs. Parks, from 1965 to 1988. In February, 1987, she co-founded the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development with Ms. Elaine Eason Steele in honor of her husband, Raymond (1903-1977). The purpose is to motivate and direct youth not targeted by other programs to achieve their highest potential. Rosa Parks sees the energy of young people as a real force for change. It is among her most treasured themes of human priorities as she speaks to young people of all ages at schools, colleges, and national organizations around the world.

The Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development’s “Pathways to Freedom program, traces the underground railroad into the civil rights movement and beyond. Youth, ages 11 through 17, meet and talk with Mrs. Parks and other national leaders as they participate in educational and historical research throughout the world. They journey primarily by bus as “freedom riders” did in the 1960′s,the theme: “Where have we been? Where are we going?”

As a role model for youth she was stimulated by their enthusiasm to learn as much about her life as possible. A modest person, she always encourages them to research the lives of other contributors to world peace. The Institute and The Rosa Parks Legacy are her legacies to people of good will.

Mrs. Parks received more than forty-three honorary doctorate degrees, including one from SOKA UNIVERSITY, Tokyo Japan, hundreds of plaques, certificates, citations, awards and keys to many cities. Among them are the NAACP’s Spingarn Medal, the UAW’s Social Justice Award, the Martin Luther King, Jr. Non – Violent Peace Prize and the ROSA PARKS PEACE PRIZE in 1994, Stockholm Sweden, to name a few. In September 1996 President William J. Clinton, the forty second President of the United States of America gave Mrs. Parks the MEDAL OF FREEDOM, the highest award given to a civilian citizen.

Published Act no.28 of 1997 designated the first Monday following February 4, as Mrs Rosa Parks’ Day in the state of Michigan, her home state. She is the first living person to be honored with a holiday.

She was voted by Time Magazine as one of the 100 most Influential people of the 20th century. A Museum and Library is being built in her honor, in Montgomery, AL and will open in the fall of the year 2000 (ground breaking April 21, 1998). On September 2, 1998 The Rosa L. Parks Learning Center was dedicated at Botsford Commons, a senior community in Michigan. Through the use of computer technology, youth will mentor seniors on the use of computers. (Mrs. Parks was a member of the first graduating class on November 24, 1998). On September 26, 1998 Mrs. Parks was the recipient of the first International Freedom Conductor’s Award by the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati, Ohio.

She attended her first “State of the Union Address” in January 1999. Mrs. Parks received a unanimous bipartisan standing ovation when President William Jefferson Clinton acknowledged her. Representative Julia Carson of Indianapolis, Indiana introduced H. R. Bill 573 on February 4, 1999, which would award Mrs. Rosa Parks the Congressional Gold Medal of Honor if it passed the House of Representatives and the Senate by a majority. The bill was passed unanimously in the Senate on April 19, and with one descenting vote in the House of Representatives on April 20. President Clinton signed it into law on May 3, 1999. Mrs. Parks was one of only 250 individuals at the time, including the American Red Cross to receive this honor. President George Washington was the first to receive the Congressional Gold Medal of Honor. President Nelson Mandela is also listed among the select few of world leaders who have received the medal.

In the winter of 2000 Mrs. Parks met Pope John-Paul II in St. Louis, MO and read a statement to him asking for racial healing. She received the NAACP Image Award for Best Supporting Actress in the Television series, TOUCHED BY AN ANGEL, “Black like Monica”. Troy State University at Montgomery opened The Rosa Parks Library and Museum on the site where Mrs. Parks was arrested December 1, 1955. It opened on the 45th Anniversary of her arrest and the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

“The Rosa Parks Story” was filmed in Montgomery, Alabama May 2001, an aired February 24, 2002 on the CBS television network. Mrs. Parks continues to receive numerous awards including the very first Lifetime Achievement Award ever given by The Institute for Research on Women & Gender, Stanford University. She received the Gandhi, King, Ikeda award for peace and on October 29, 2003 Mrs. Parks was an International Institute Heritage Hall of fame honoree. On February 4, 2004 Mrs. Parks 91st birthday was celebrated at the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History. On December 21, 2004 the 49th Anniversary of the Mrs. Parks’ arrest was commemorated with a Civil Rights and Hip-Hop Forum at the Franklin Settlement in Detroit, Michigan.

On February 4, 2005 Mrs. Parks’ 92nd birthday was celebrate at Calvary Baptist Church in Detroit, MI. Students from the Detroit Public Schools did “Willing to be Arrested,” a reenactment of Mrs. Parks arrest. February 6, 2005 Mrs. Parks received the first annual Cardinal Dearden Peace Award at Holy Trinity Catholic Church in Detroit, MI. February 19 – 20, composer Hannibal Lokumbe premiered an original symphony “Dear Mrs. Parks.” Mr. Lokumbe did this original work as part of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra’s ” Classical Roots Series.” The beginning of many events that will commemorate the 50th Anniversary of Mrs. Parks’ arrest December 1, 1955.

Mrs. Parks has written four books, Rosa Parks: My Story: by Rosa Parks with Jim Haskins, Quiet Strength by Rosa Parks with Gregory J. Reed, Dear Mrs. Parks: A Dialogue With Today’s Youth by Rosa Parks with Gregory J, Reed, this book received the NAACP’s Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work, (Children’s) in 1996 and her latest book, I AM ROSA PARKS by Rosa Parks with Jim Haskins, for preschoolers.

A quiet exemplification of courage, dignity, and determination; Rosa Parks was a symbol to all to remain free. Rosa Parks made her peaceful transition October 24, 2005.

Find Us On Facebook

REACH THE INSTITUTE

Rosa parks institute for self development.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

By: History.com Editors

Updated: February 20, 2024 | Original: November 9, 2009

Rosa Parks (1913—2005) helped initiate the civil rights movement in the United States when she refused to give up her seat to a white man on a Montgomery, Alabama bus in 1955. Her actions inspired the leaders of the local Black community to organize the Montgomery Bus Boycott . Led by a young Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. , the boycott lasted more than a year—during which Parks not coincidentally lost her job—and ended only when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that bus segregation was unconstitutional. Over the next half-century, Parks became a nationally recognized symbol of dignity and strength in the struggle to end entrenched racial segregation .

Rosa Parks’ Early Life

Rosa Louise McCauley was born in Tuskegee, Alabama , on February 4, 1913. She moved with her parents, James and Leona McCauley, to Pine Level, Alabama, at age 2 to reside with Leona’s parents. Her brother, Sylvester, was born in 1915, and shortly after that her parents separated.

Did you know? When Rosa Parks refused to give up her bus seat in 1955, it wasn’t the first time she’d clashed with driver James Blake. Parks stepped onto his very crowded bus on a chilly day 12 years earlier, paid her fare at the front, then resisted the rule in place for Black people to disembark and re-enter through the back door. She stood her ground until Blake pulled her coat sleeve, enraged, to demand her cooperation. Parks left the bus rather than give in.

Rosa’s mother was a teacher, and the family valued education. Rosa moved to Montgomery, Alabama, at age 11 and eventually attended high school there, a laboratory school at the Alabama State Teachers’ College for Negroes. She left at 16, early in 11th grade, because she needed to care for her dying grandmother and, shortly thereafter, her chronically ill mother. In 1932, at 19, she married Raymond Parks, a self-educated man 10 years her senior who worked as a barber and was a long-time member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People ( NAACP ). He supported Rosa in her efforts to earn her high-school diploma, which she ultimately did the following year.

Rosa Parks: Roots of Activism

Raymond and Rosa, who worked as a seamstress, became respected members of Montgomery’s large African American community. Co-existing with white people in a city governed by “ Jim Crow ” (segregation) laws, however, was fraught with daily frustrations: Black people could attend only certain (inferior) schools, could drink only from specified water fountains and could borrow books only from the “Black” library, among other restrictions.

Although Raymond had previously discouraged her out of fear for her safety, in December 1943, Rosa also joined the Montgomery chapter of the NAACP and became chapter secretary . She worked closely with chapter president Edgar Daniel (E.D.) Nixon. Nixon was a railroad porter known in the city as an advocate for Black people who wanted to register to vote, and also as president of the local branch of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters union .

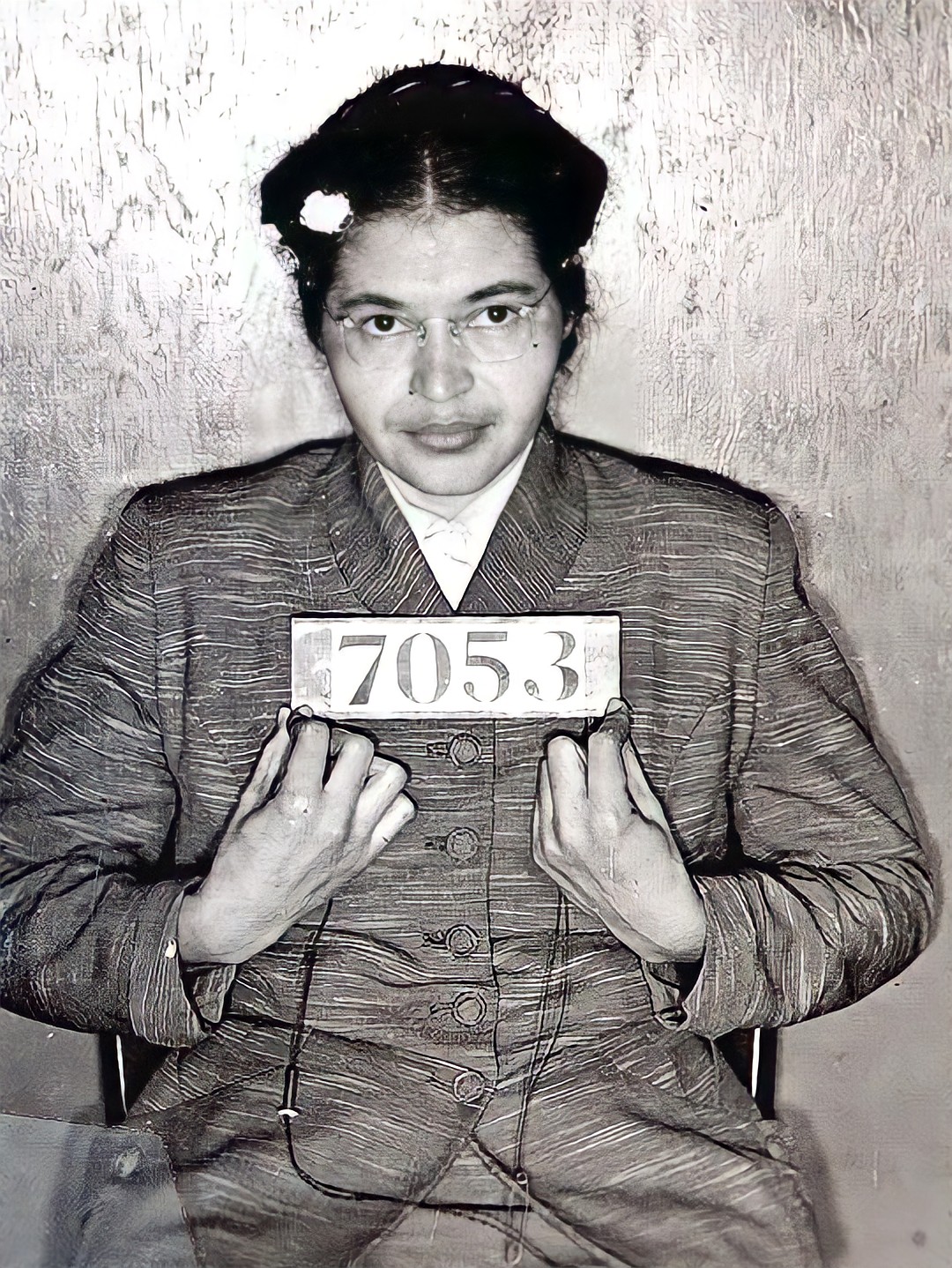

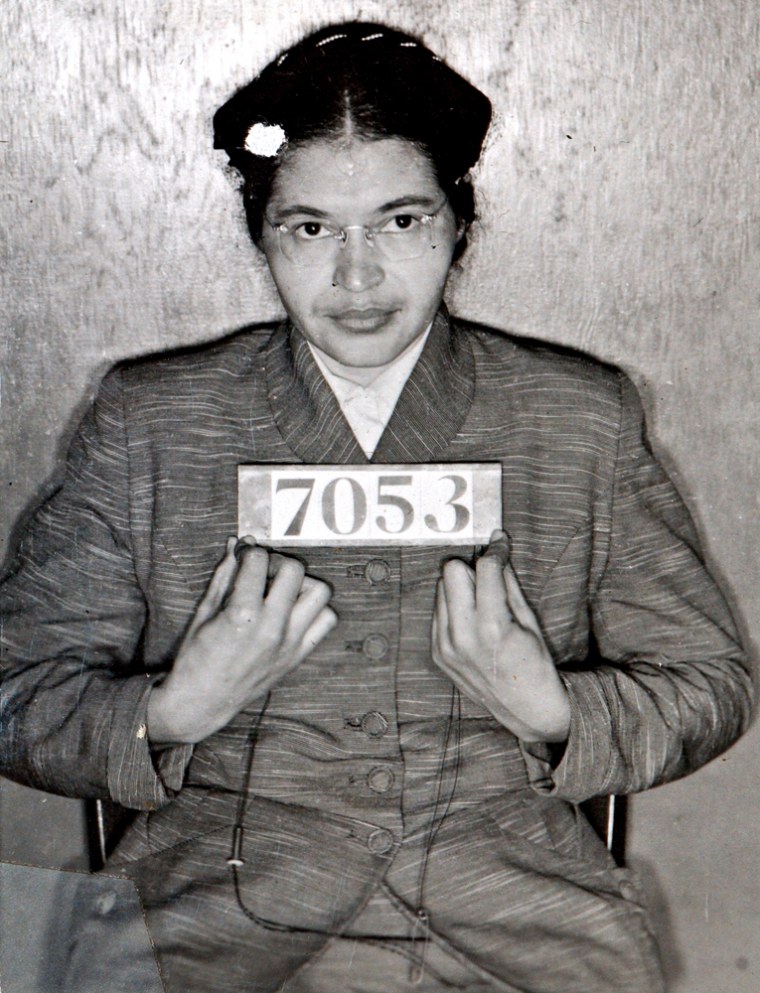

December 1, 1955: Rosa Parks Is Arrested

On Thursday, December 1, 1955, the 42-year-old Rosa Parks was commuting home from a long day of work at the Montgomery Fair department store by bus. Black residents of Montgomery often avoided municipal buses if possible because they found the Negroes-in-back policy so demeaning. Nonetheless, 70 percent or more riders on a typical day were Black, and on this day Rosa Parks was one of them.

Segregation was written into law; the front of a Montgomery bus was reserved for white citizens, and the seats behind them for Black citizens. However, it was only by custom that bus drivers had the authority to ask a Black person to give up a seat for a white rider. There were contradictory Montgomery laws on the books: One said segregation must be enforced, but another, largely ignored, said no person (white or Black) could be asked to give up a seat even if there were no other seat on the bus available.

Nonetheless, at one point on the route, a white man had no seat because all the seats in the designated “white” section were taken. So the driver told the riders in the four seats of the first row of the “colored” section to stand, in effect adding another row to the “white” section. The three others obeyed. Parks did not.

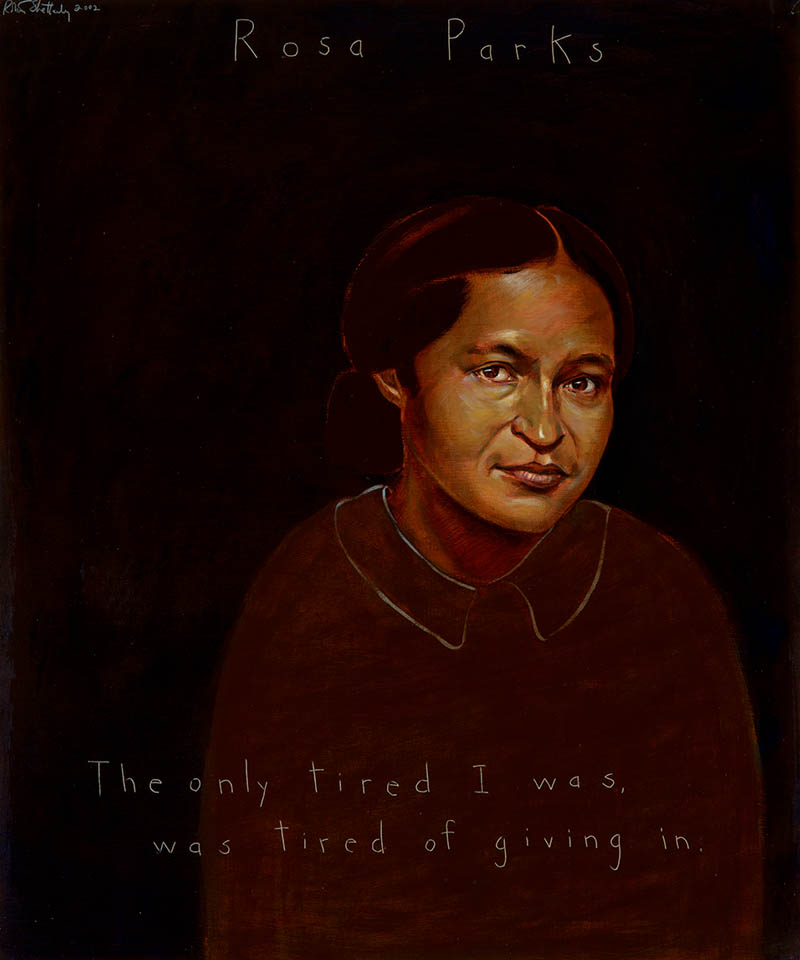

“People always say that I didn’t give up my seat because I was tired,” wrote Parks in her autobiography, “but that isn’t true. I was not tired physically… No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

Eventually, two police officers approached the stopped bus, assessed the situation and placed Parks in custody.

Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott

Although Parks used her one phone call to contact her husband, word of her arrest had spread quickly and E.D. Nixon was there when Parks was released on bail later that evening. Nixon had hoped for years to find a courageous Black person of unquestioned honesty and integrity to become the plaintiff in a case that might become the test of the validity of segregation laws. Sitting in Parks’ home, Nixon convinced Parks—and her husband and mother—that Parks was that plaintiff. Another idea arose as well: The Black population of Montgomery would boycott the buses on the day of Parks’ trial, Monday, December 5. By midnight, 35,000 flyers were being mimeographed to be sent home with Black schoolchildren, informing their parents of the planned boycott.

On December 5, Parks was found guilty of violating segregation laws, given a suspended sentence and fined $10 plus $4 in court costs. Meanwhile, Black participation in the boycott was much larger than even optimists in the community had anticipated. Nixon and some ministers decided to take advantage of the momentum, forming the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA) to manage the boycott, and they elected Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.–new to Montgomery and just 26 years old—as the MIA’s president.

As appeals and related lawsuits wended their way through the courts, all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court , the Montgomery Bus Boycott engendered anger in much of Montgomery’s white population as well as some violence, and Nixon’s and Dr. King’s homes were bombed . The violence didn’t deter the boycotters or their leaders, however, and the drama in Montgomery continued to gain attention from the national and international press.

On November 13, 1956, the Supreme Court ruled that bus segregation was unconstitutional; the boycott ended December 20, a day after the Court’s written order arrived in Montgomery. Parks—who had lost her job and experienced harassment all year—became known as “the mother of the civil rights movement.”

Rosa Parks's Life After the Boycott

Facing continued harassment and threats in the wake of the boycott, Parks, along with her husband and mother, eventually decided to move to Detroit, where Parks’ brother resided. Parks became an administrative aide in the Detroit office of Congressman John Conyers Jr. in 1965, a post she held until her 1988 retirement. Her husband, brother and mother all died of cancer between 1977 and 1979. In 1987, she co-founded the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self-Development, to serve Detroit’s youth.

In the years following her retirement, she traveled to lend her support to civil-rights events and causes and wrote an autobiography, Rosa Parks: My Story . In 1999, Parks was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest honor the United States bestows on a civilian. (Other recipients have included George Washington , Thomas Edison , Betty Ford and Mother Teresa.) When she died at age 92 on October 24, 2005, she became the first woman in the nation’s history to lie in honor at the U.S. Capitol.

HISTORY Vault: Black History

Watch acclaimed Black History documentaries on HISTORY Vault.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

On December 1, 1955, Rosa Parks boarded a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Instead of going to the back of the bus, which was designated for African Americans, she sat in the front. When the bus started to fill up with white passengers, the bus driver asked Parks to move. She refused. Her resistance set in motion one of the largest social movements in history, the Montgomery Bus Boycott .

Rosa Louise McCauley was born on February 4th, 1913 in Tuskegee, Alabama. As a child, she went to an industrial school for girls and later enrolled at Alabama State Teachers College for Negroes (present-day Alabama State University). Unfortunately, Parks was forced to withdraw after her grandmother became ill. Growing up in the segregated South, Parks was frequently confronted with racial discrimination and violence. She became active in the Civil Rights Movement at a young age.

Parks married a local barber by the name of Raymond Parks when she was 19. He was actively fighting to end racial injustice. Together the couple worked with many social justice organizations. Eventually, Rosa was elected secretary of the Montgomery chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

By the time Parks boarded the bus in 1955, she was an established organizer and leader in the Civil Rights Movement in Alabama. Parks not only showed active resistance by refusing to move she also helped organize and plan the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Many have tried to diminish Parks’ role in the boycott by depicting her as a seamstress who simply did not want to move because she was tired. Parks denied the claim and years later revealed her true motivation:

“People always say that I didn’t give up my seat because I was tired, but that isn’t true. I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was forty-two. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

Parks courageous act and the subsequent Montgomery Bus Boycott led to the integration of public transportation in Montgomery. Her actions were not without consequence. She was jailed for refusing to give up her seat and lost her job for participating in the boycott.

After the boycott, Parks and her husband moved to Hampton, Virginia and later permanently settled in Detroit, Michigan. Parks work proved to be invaluable in Detroit’s Civil Rights Movement. She was an active member of several organizations which worked to end inequality in the city. By 1980, after consistently giving to the movement both financially and physically Parks, now widowed, suffered from financial and health troubles. After almost being evicted from her home, local community members and churches came together to support Parks. On October 24th, 2005, at the age of 92, she died of natural causes leaving behind a rich legacy of resistance against racial discrimination and injustice.

- Parks, Rosa. Rosa Parks: My Story. New York: Puffin Books, 1999.

- Theoharis, Jeanne. The Rebellious Life of Mrs.Rosa Parks. New York: Beacon Press, 2014.

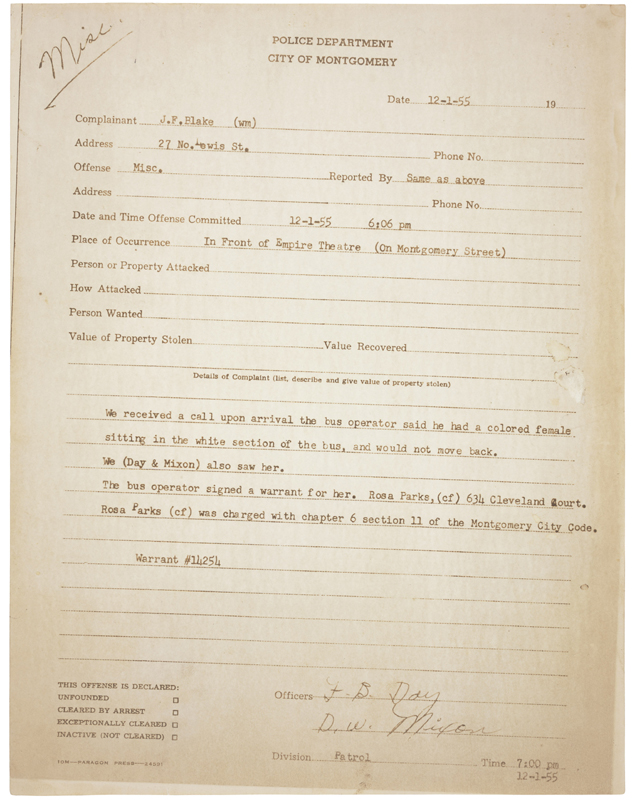

- “An Act of Courage, The Arrest Records of Rosa Parks” National Archives, Accessed 23 March 2017. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/rosa-parks

- PHOTO: Library of Congress

MLA – Norwood, Arlisha. "Rosa Parks." National Women's History Museum. National Women's History Museum, 2017. Date accessed.

Chicago- Norwood, Arlisha. "Rosa Parks." National Women's History Museum. 2017. www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/rosa-parks.

- Robinson, Jo Ann. Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Women Who Started It: The Memoir of Jo Ann Gibson Robison. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1987.

- “Rosa Parks: How I Fought for Civil Rights.” Scholastic Teacher’s Activity Guide. Accessed 23 March 2017.

- “What If: I Don’t Move to the Back of The Bus?” The Henry Ford Foundation : Stories of Innovation, Accessed March 23 2017.

Related Biographies

Stacey Abrams

Abigail Smith Adams

Jane Addams

Toshiko Akiyoshi

Related background, mary church terrell , belva lockwood and the precedents she set for women’s rights, women’s rights lab: black women’s clubs, educational equality & title ix:.

- Member Interviews

- Science & Exploration

- Public Service

- Achiever Universe

- Summit Overview

- About The Academy

- Academy Patrons

- Delegate Alumni

- Directors & Our Team

- Golden Plate Awards Council

- Golden Plate Awardees

- Preparation

- Perseverance

- The American Dream

- Recommended Books

- Find My Role Model

All achievers

Pioneer of civil rights.

Download our free multi-touch iBook The Road to Civil Rights — available for your Mac or iOS device on Apple Books

The Road to Civil Rights iBook takes readers on a journey through one of the most significant periods in America’s history. Travel through the timeline and listen to members of the American Academy of Achievement as they discuss the key events that shaped the future of the country.

Listen to this achiever on What It Takes

What It Takes is an audio podcast produced by the American Academy of Achievement featuring intimate, revealing conversations with influential leaders in the diverse fields of endeavor: public service, science and exploration, sports, technology, business, arts and humanities, and justice.

Two policemen came on the bus, and one asked me if the driver had told me to stand. He wanted to know why I didn’t stand, and I told him I didn’t think I should have to stand up. I asked him, why did they push us around? He said, I don’t know, but the law is the law and you are under arrest.

Most historians date the beginning of the modern civil rights movement in the United States to December 1, 1955. That was the day when an unknown seamstress in Montgomery, Alabama refused to give up her bus seat to a white passenger. This brave woman, Rosa Parks, was arrested and fined for violating a city ordinance, but her lonely act of defiance began a movement that ended legal segregation in America, and made her an inspiration to freedom-loving people everywhere.

Rosa Parks was born Rosa Louise McCauley in Tuskegee, Alabama to James McCauley, a carpenter, and Leona McCauley, a teacher. At the age of two she moved to her grandparents’ farm in Pine Level, Alabama with her mother and younger brother, Sylvester. At the age of 11 she enrolled in the Montgomery Industrial School for Girls, a private school founded by liberal-minded women from the northern United States.

The school’s philosophy of self-worth was consistent with Leona McCauley’s advice to “take advantage of the opportunities, no matter how few they were.” Opportunities were few indeed. “Back then,” Mrs. Parks recalled in an interview, “we didn’t have any civil rights. It was just a matter of survival, of existing from one day to the next. I remember going to sleep as a girl hearing the Klan ride at night and hearing a lynching and being afraid the house would burn down.” In the same interview, she cited her lifelong acquaintance with fear as the reason for her relative fearlessness in deciding to appeal her conviction during the bus boycott. “I didn’t have any special fear,” she said. “It was more of a relief to know that I wasn’t alone.” After attending Alabama State Teachers College, the young Rosa settled in Montgomery, with her husband, Raymond Parks. The couple joined the local chapter of the NAACP and worked quietly for many years to improve the lot of African Americans in the segregated South.

“I worked on numerous cases with the NAACP,” Mrs. Parks recalled, “but we did not get the publicity. There were cases of flogging, peonage, murder, and rape. We didn’t seem to have too many successes. It was more a matter of trying to challenge the powers that be, and to let it be known that we did not wish to continue being second-class citizens.”

The bus incident led to the formation of the Montgomery Improvement Association, led by the young pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The association called for a boycott of the city-owned bus company. The boycott lasted 381 days and brought Mrs. Parks, Dr. King, and their cause to the attention of the world. A Supreme Court decision struck down the Montgomery ordinance under which Mrs. Parks had been fined, and outlawed racial segregation on public transportation.

In 1957, Mrs. Parks and her husband moved to Detroit, Michigan, where Mrs. Parks served on the staff of U.S. Representative John Conyers. The Southern Christian Leadership Council established an annual Rosa Parks Freedom Award in her honor.

After the death of her husband in 1977, Mrs. Parks founded the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self-Development. The Institute sponsors an annual summer program for teenagers called Pathways to Freedom. The young people tour the country in buses, under adult supervision, learning the history of their country and of the civil rights movement. President Clinton presented Rosa Parks with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1996. She received a Congressional Gold Medal in 1999.

When asked if she was happy living in retirement, Rosa Parks replied, “I do the very best I can to look upon life with optimism and hope and looking forward to a better day, but I don’t think there is any such thing as complete happiness. It pains me that there is still a lot of Klan activity and racism. I think when you say you’re happy, you have everything that you need and everything that you want, and nothing more to wish for. I haven’t reached that stage yet.”

Mrs. Parks spent her last years living quietly in Detroit, where she died in 2005 at the age of 92. After her death, her casket was placed in the rotunda of the United States Capitol for two days, so the nation could pay its respects to the woman whose courage had changed the lives of so many. She was the first woman and the second African American to lie in honor at the Capitol, a distinction usually reserved for Presidents of the United States.

View and listen to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s historic “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered on the steps of Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C., August 28, 1963.

Member of the American Academy of Achievement, poet and best-selling author, Maya Angelou shares her interpretation of Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

Rosa Parks, the “Mother of the Civil Rights Movement” was one of the most important citizens of the 20th century. Mrs. Parks was a seamstress in Montgomery, Alabama when, in December of 1955, she refused to give up her seat on a city bus to a white passenger. The bus driver had her arrested. She was tried and convicted of violating a local ordinance.

Her act sparked a citywide boycott of the bus system by blacks that lasted more than a year. The boycott raised an unknown clergyman named Martin Luther King, Jr., to national prominence and resulted in the U.S. Supreme Court decision outlawing segregation on city buses. Over the next four decades, she helped make her fellow Americans aware of the history of the civil rights struggle. This pioneer in the struggle for racial equality was the recipient of innumerable honors, including the Martin Luther King Jr. Nonviolent Peace Prize and the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Her example remains an inspiration to freedom-loving people everywhere.

In 1955, you refused to give up your seat to a white passenger on a public bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Your act inspired the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the event historians call the beginning of the modern Civil Rights Movement. Could you tell us exactly what happened that day?

Rosa Parks: I was arrested on December 1, 1955 for refusing to stand up on the orders of the bus driver, after the white seats had been occupied in the front. And of course, I was not in the front of the bus as many people have written and spoken that I was — that I got on the bus and took the front seat, but I did not. I took a seat that was just back of where the white people were sitting, in fact, the last seat. A man was next to the window, and I took an aisle seat and there were two women across. We went on undisturbed until about the second or third stop when some white people boarded the bus and left one man standing. And when the driver noticed him standing, he told us to stand up and let him have those seats. He referred to them as front seats. And when the other three people — after some hesitancy — stood up, he wanted to know if I was going to stand up, and I told him I was not. And he told me he would have me arrested. And I told him he may do that. And of course, he did. Two policemen came on the bus and one asked me if the driver had told me to stand and I said, “Yes.” And he wanted to know why I didn’t stand, and I told him I didn’t think I should have to stand up. And then I asked him, why did they push us around? And he said, and I quote him, “I don’t know, but the law is the law and you are under arrest.” And with that, I got off the bus, under arrest.

Did they take you down to the police station?

Rosa Parks: Yes. A policeman wanted the driver to swear out a warrant, if he was willing, and he told him that he would sign a warrant when he finished his trip and delivered his passengers, and he would come straight down to the City Hall to sign a warrant against me.

Did he do that?

Rosa Parks: Yes, he did.

Did the public response begin immediately?

Rosa Parks: Actually, it began as soon as it was announced.

It was put in the paper that I had been arrested. Mr. E.D. Nixon was the legal redress chairman of the Montgomery branch of the NAACP, and he made a number of calls during the night, called a number of ministers. I was arrested on a Thursday evening, and on Friday evening is when they had the meeting at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where Dr. Martin Luther King was the pastor. A number of citizens came, and I told them the story and from then on, it became news about my being arrested. My trial was December 5, when they found me guilty. The lawyers Fred Gray and Charles Langford, who represented me, filed an appeal and, of course, I didn’t pay any fine. We set a meeting at the Holt Street Baptist Church on the evening of December 5th, because December 5th was the day the people stayed off in large numbers and did not ride the bus. In fact, most of the buses, I think all of them were just about empty with the exception of maybe very, very few people. When they found out that one day’s protest had kept people off the bus, it came to a vote and unanimously, it was decided that they would not ride the buses anymore until changes for the better were made.

When you refused to stand up, did you have a sense of anger at having to do it?

Rosa Parks: I don’t remember feeling that anger, but I did feel determined to take this as an opportunity to let it be known that I did not want to be treated in that manner and that people have endured it far too long. However, I did not have at the moment of my arrest any idea of how the people would react. And since they reacted favorably, I was willing to go with that. We formed what was known as the Montgomery Improvement Association, on the afternoon of December 5th. Dr. Martin Luther King became very prominent in this movement, so he was chosen as a spokesman and the president of the Montgomery Improvement Association.

What are your thoughts when you look back on that time in your life. Any regrets?

As I look back on those days, it’s just like a dream. The only thing that bothered me was that we waited so long to make this protest and to let it be known wherever we go that all of us should be free and equal and have all opportunities that others should have.

What personal characteristics do you think are most important to accomplish something?

Rosa Parks: I think it’s important to believe in yourself and when you feel like you have the right idea, to stay with it. And of course, it all depends upon the cooperation of the people around. People were very cooperative in getting off the buses. And from that, of course, we went on to other things. I, along with Mrs. Field, who was here with me, organized the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self-Development. Raymond, my husband—he is now deceased—was another person who inspired me, because he believed in freedom and equality himself.

You were married during the bus incident.

Rosa Parks: Yes, I was.

How old were you?

Rosa Parks: When I was arrested, I was 42 years old. There were so many needs for us to continue to work for freedom, because I didn’t think that we should have to be treated in the way we were, just for the sake of white supremacy, because it was designed to make them feel superior, and us feel inferior. That was the whole plan of racially enforced segregation.

What was it like in Montgomery when you were growing up?

Rosa Parks: Back in Montgomery during my growing up there, it was completely legally enforced racial segregation, and of course, I struggled against it for a long time. I felt that it was not right to be deprived of freedom when we were living in the Home of the Brave and Land of the Free. Of course, when I refused to stand up, on the orders of the bus driver, for a white passenger to take the seat, and I was not sitting in the front of the bus, as so many people have said, and neither was my feet hurting, as many people have said. But I made up my mind that I would not give in any longer to legally-imposed racial segregation and of course my arrest brought about the protests for more than a year. And in doing so, Dr. Martin Luther King became prominent because he was the leader of our protests along with many other people. And I’m very glad that this experience I had then brought about a movement that triggered across the United States and in other places.

- 26 photos

Biography Online

Rosa Parks Biography

Parks is famous for her refusal on 1 December 1955, to obey bus driver James Blake’s demand that she relinquish her seat to a white man. Her subsequent arrest and trial for this act of civil disobedience triggered the Montgomery Bus Boycott, one of the largest and most successful mass movements against racial segregation in history, and launched Martin Luther King, Jr ., one of the organisers of the boycott, to the forefront of the civil rights movement. Her role in American history earned her an iconic status in American culture, and her actions have left an enduring legacy for civil rights movements around the world.

Early life Rosa Parks

Rosa Louise McCauley was born in Tuskegee, Alabama, on February 4, 1913. Her ancestors included both Irish-Scottish lineage and also a great grandmother who was a slave. She attended local rural schools, and after the age of 11, the Industrial School for Girls in Montgomery. However, she later had to opt out of school to look after her grandmother.

As a child, Rosa became aware of the segregation which was deeply embedded in Alabama. She experienced deep-rooted racism and became conscious of the different opportunities faced by white and black children. She also recalls seeing a Klu Klux Klan march go past her house – where her father stood outside with a shotgun. Due to the Jim Crow laws, most black voters were effectively disenfranchised.

In 1932, she married Raymond Parks, a barber from Montgomery. He was active in the NAACP, and Rosa Parks became a supporter – helping with fund-raising and other initiatives. She attended meetings defending the rights of black people and seeking to prevent injustice.

Montgomery Bus Boycott

After a day at work at Montgomery Fair department store, Parks boarded the Cleveland Avenue bus at around 6 p.m., Thursday, 1 December 1955, in downtown Montgomery. She paid her fare and sat in an empty seat in the first row of back seats reserved for blacks in the “colored” section, which was near the middle of the bus and directly behind the ten seats reserved for white passengers. Initially, she had not noticed that the bus driver was the same man, James F. Blake, who had left her in the rain in 1943. As the bus travelled along its regular route, all of the white-only seats in the bus filled up. The bus reached the third stop in front of the Empire Theater, and several white passengers boarded.

Following standard practice, the bus driver Blake noted that the front of the bus was filled with white passengers and there were two or three men standing. Therefore, he moved the “colored” section sign behind Parks and demanded that four black people give up their seats in the middle section so that the white passengers could sit. Years later, in recalling the events of the day, Parks said,

“When that white driver stepped back toward us, when he waved his hand and ordered us up and out of our seats, I felt a determination cover my body like a quilt on a winter night.”

“When he saw me still sitting, he asked if I was going to stand up, and I said, ‘No, I’m not.’ And he said, ‘Well, if you don’t stand up, I’m going to have to call the police and have you arrested.’ I said, ‘You may do that.'”

During a 1956 radio interview with Sydney Rogers in West Oakland, Parks was asked why she decided not to vacate her bus seat. Parks said, “I would have to know for once and for all what rights I had as a human being and a citizen of Montgomery, Alabama.”

She also detailed her motivation in her autobiography, My Story:

“ People always say that I didn’t give up my seat because I was tired, but that isn’t true. I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was forty-two. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in. ”

When Parks refused to give up her seat, a police officer arrested her. As the officer took her away, she recalled that she asked, “Why do you push us around?” The officer’s response as she remembered it was, “I don’t know, but the law’s the law, and you’re under arrest.” She later said, “I only knew that, as I was being arrested, that it was the very last time that I would ever ride in humiliation of this kind.”

Parks was charged with a violation of Chapter 6, Section 11 segregation law of the Montgomery City code, even though she technically had not taken up a white-only seat — she had been in a colored section. E.D. Nixon and Clifford Durr bailed Parks out of jail the evening of December 1.

That evening, Nixon conferred with Alabama State College professor Jo Ann Robinson about Parks’ case. Robinson, a member of the Women’s Political Council (WPC), stayed up all night mimeographing over 35,000 handbills announcing a bus boycott. The Women’s Political Council was the first group to officially endorse the boycott.

On Sunday 4th December 1955, plans for the Montgomery Bus Boycott were announced at black churches in the area, and a front-page article in The Montgomery Advertiser helped spread the word. At a church rally that night, attendees unanimously agreed to continue the boycott until they were treated with the level of courtesy they expected, until black drivers were hired, and until seating in the middle of the bus was handled on a first-come basis.

Four days later, Parks was tried on charges of disorderly conduct and violating a local ordinance. The trial lasted 30 minutes. Parks was found guilty and fined $10, plus $4 in court costs. Parks appealed her conviction and formally challenged the legality of racial segregation. In a 1992 interview with National Public Radio’s Lynn Neary, Parks recalled:

“I did not want to be mistreated, I did not want to be deprived of a seat that I had paid for. It was just time… there was opportunity for me to take a stand to express the way I felt about being treated in that manner. I had not planned to get arrested. I had plenty to do without having to end up in jail. But when I had to face that decision, I didn’t hesitate to do so because I felt that we had endured that too long. The more we gave in, the more we complied with that kind of treatment, the more oppressive it became. ”

On Monday 5 December 1955, after the success of the one-day boycott, a group of 16 to 18 people gathered at the Mt. Zion AME Zion Church to discuss boycott strategies. The group agreed that a new organisation was needed to lead the boycott effort if it were to continue. Rev. Ralph David Abernathy suggested the name “Montgomery Improvement Association” (MIA). The name was adopted, and the MIA was formed. Its members elected as their president, a relative newcomer to Montgomery, a young and mostly unknown minister of Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, Dr Martin Luther King, Jr.

That Monday night, 50 leaders of the African American community gathered to discuss the proper actions to be taken in response to Parks’ arrest. E.D. Nixon said, “My God, look what segregation has put in my hands!” Parks was the ideal plaintiff for a test case against city and state segregation laws. While the 15-year-old Claudette Colvin, unwed and pregnant, had been deemed unacceptable to be the center of a civil rights mobilization, King stated that, “Mrs Parks, on the other hand, was regarded as one of the finest citizens of Montgomery—not one of the finest Negro citizens, but one of the finest citizens of Montgomery.” Parks was securely married and employed, possessed a quiet and dignified demeanour, and was politically savvy.

The day of Parks’ trial — Monday, December 5, 1955 — the WPC distributed the 35,000 leaflets. The handbill read, “We are…asking every Negro to stay off the buses Monday in protest of the arrest and trial . . . You can afford to stay out of school for one day. If you work, take a cab, or walk. But please, children and grown-ups, don’t ride the bus at all on Monday. Please stay off the buses Monday.”

Rosa Parks on a bus (Dec 1956) after the segregation law was lifted.

It rained that day, but the black community persevered in their boycott. Some rode in carpools, while others travelled in black-operated cabs that charged the same fare as the bus, 10 cents. Most of the remainder of the 40,000 black commuters walked, some as far as 20 miles. In the end, the boycott lasted for 382 days. Dozens of public buses stood idle for months, severely damaging the bus transit company’s finances until the law requiring segregation on public buses was lifted.

Some segregationists retaliated with terrorism. Black churches were burned or dynamited. Martin Luther King’s home was bombed in the early morning hours of January 30, 1956, and E.D. Nixon’s home was also attacked. However, the black community’s bus boycott marked one of the largest and most successful mass movements against racial segregation. It sparked many other protests, and it catapulted King to the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement.

Through her role in sparking the boycott, Rosa Parks played an important part in internationalising the awareness of the plight of African Americans and the civil rights struggle. King wrote in his 1958 book Stride Toward Freedom that Parks’ arrest was the precipitating factor, rather than the cause, of the protest: “The cause lay deep in the record of similar injustices…. Actually, no one can understand the action of Mrs. Parks unless he realizes that eventually, the cup of endurance runs over, and the human personality cries out, ‘I can take it no longer.'”

The Montgomery bus boycott was also the inspiration for the bus boycott in the township of Alexandria, Eastern Cape of South Africa which was one of the key events in the radicalization of the black majority of that country under the leadership of the African National Congress.

Rosa Parks after boycott

After the boycott, Rosa Parks became an icon and leading spokesperson of the civil rights movement in the US. Immediately after the boycott, she lost her job in a department store. For many years she worked as a seamstress.

In 1965, she was hired by African-American U.S. Representative John Conyers. She worked as his secretary until her retirement in 1988. Conyers remarked of Rosa Parks.

“You treated her with deference because she was so quiet, so serene — just a very special person.” [CNN,2004]

Some of the awards Rosa Parks received.

- She was selected to be one of the people to meet Nelson Mandela on his release from prison in 1994.

- In 1996, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Bill Clinton

- In 1997, she was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal – the highest award of Congress.

Death and funeral

Rosa Parks resided in Detroit until she died at the age of ninety-two on October 24, 2005.

Citation: Pettinger, Tejvan . “ Rosa Parks Biography” , Oxford, UK. www.biographyonline.net. Published 11th Feb 2012. Last updated 13th Feb 2019.

Rosa Parks books

The Rebellious Life of Mrs Rosa Parks at Amazon

Related pages

External links

- Rosa Parks institution

Rosa Parks’ Life After the Montgomery Bus Boycott

Before she became a nationally admired civil rights icon, Rosa Parks’ life consisted of ups and downs that included struggles to support her family and taking new paths in activism.

Decades would pass before Parks' role in the boycott made her a respected figure across the country; between the bus boycott and widespread recognition for her work, Parks' life encompassed both difficulties and triumphs.

Parks and her husband lost their jobs after the boycott

Soon after the Montgomery bus boycott began, Parks lost her job as a tailor's assistant at the Montgomery Fair department store. Her husband Raymond also had to leave his job as a barber at Maxwell Air Force Base because he'd been ordered not to discuss his wife.

Yet the boycott's conclusion didn't make it easy for either of them to get back to earning a living — Parks was too identified with the protest for her or her husband to land another regular job in Alabama.

Parks had been a dedicated volunteer for the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), a local group that had helped coordinate the boycott, but the organization didn't hire her, nor did any other civil rights group. Despite contributions such as traveling to give talks about the boycott to raise funds for the MIA and the NAACP , male leadership did not identify with Parks' needs.

There was also jealousy among locals over the amount of attention Parks had received. In the end, she decided her only choice was to leave Alabama with her husband and mother.

READ MORE: Rosa Parks: Timeline of Her Life, Montgomery Bus Boycott and Death

Her family moved to Detroit, hoping to find work

In 1957, Parks and her family went to Detroit, where her brother and cousin lived. Unfortunately, finding work there still wasn't easy, either. Parks soon headed to Virginia to take a job as a hostess at the Hampton Institute's Holly Tree Inn. But when promised accommodation for her mother and Raymond never came through, Parks returned to Detroit at the end of the 1958 fall semester.

Back in Detroit, Raymond had to go through required training before he could become a barber and Parks could only find piecework sewing jobs. Then she had an operation for an ulcer (a condition that had developed under the stress of the bus boycott), and needed to have a throat tumor removed.

Medical costs and the difficulties of working while ill pushed Parks and her family to the edge. In July 1960, Jet magazine described her as a "tattered rag of her former self — penniless, debt-ridden, ailing with stomach ulcers, and a throat tumor, compressed into two rooms with her husband and mother."

Things finally began to turn around for the Parks family in 1961

Parks had remained involved in the fight for civil rights after moving to Detroit, but she didn't have the college degree required for positions in organizations like the NAACP. And, as in Alabama, no one in the mostly male leadership tried to help her get a job.

Some support came Parks' way, particularly after her problems became more public, and the NAACP ended up paying her hospital bill, which had gone into collection.

By the spring of 1961, her situation was better: Raymond was barbering while she was healthy enough to handle steady work as a seamstress at the Stockton Sewing Company. There she put in 10-hour days and was paid 75 cents for each piece of the aprons and skirts she completed, which added up to enough to live on.

Parks worked closely with Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X

Having worked with Martin Luther King Jr. on the bus boycott, Parks truly admired the civil rights leader. At the Southern Christian Leadership Conference's annual convention in 1962, she saw a man attack King — and experienced how King made sure the attacker faced no retaliation afterward. Following his assassination in 1968, she traveled to Memphis to support a sanitation workers' march that King had been involved in before proceeding to King's funeral.

Yet Parks also found much to appreciate in Malcolm X 's leadership. Her beliefs more closely aligned with Malcolm's, and differed from King's, on the limits of non-violence.

In a 1967 interview, Parks stated, "If we can protect ourselves against violence it’s not actually violence on our part. That’s just self-protection, trying to keep from being victimized with violence."

She eventually got a job as an assistant to Congressman John Conyers

After moving to Detroit and despite her hardships, Parks remained committed to helping her community. She joined neighborhood groups that focused on everything from schools to voter registration.

In 1964 she volunteered for John Conyers' congressional campaign. The candidate appreciated her support and credited her with getting King Jr. to come to Detroit and provide an endorsement. After Conyers won the election, he hired Parks as a receptionist and assistant for his Detroit office. She started in 1965 and remained until her retirement in 1988.

The job was a boon for Parks' financial situation, as it offered a pension and health insurance. And Parks excelled at work that ranged from aiding homeless constituents to joining Conyers in protesting a General Motors decision to close local plants. Plus her past wasn't forgotten; Conyers once remarked, "Rosa Parks was so famous that people would come by my office to meet her, not me."

Years after the boycott, Parks was still a target

Unfortunately, Parks was not always universally admired. For many white people who wanted to maintain the racist status quo, she'd been a hated figure since the Montgomery bus boycott. During that action, they'd made menacing calls and sent death threats. The attacks had been so venomous that Parks' husband Raymond suffered a nervous breakdown.

Though the boycott had ended in 1956, hateful missives continued to be sent to Parks into the 1970s. She was accused of being traitor and of harboring Communist sympathies. (Racists often felt African Americans were not capable of organizing on their own and had to be getting outside help.)

Even working for Conyers, she remained a target; rotten watermelons and hate mail arrived for her at his office when she started there. Yet, as always, such cruel attacks didn't keep Parks from doing her job.

Watch “Rosa Parks: Mother Of A Movement” on History Vault

Black History

Jesse Owens

Alice Coachman

Wilma Rudolph

Tiger Woods

Deb Haaland

10 Famous Langston Hughes Poems

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

Ava DuVernay

Octavia Spencer

Inventor Garrett Morgan’s Lifesaving 1916 Rescue

Get to Know 5 History-Making Black Country Singers

Seamstress, Civil Rights Leader : 1913 – 2005

“the only tired i was, was tired of giving in.”.

Rosa Parks, the matriarch of the civil rights movement, has been described as an old woman who was too tired to give up her seat on a bus to a white person. However, Parks used her autobiography to correct the record. “I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was forty-two.” She also made it clear that “the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.” Parks’s sentiment represented the view of the millions of African Americans, and their allies, who set out to end legal segregation in the mid-1900s.

Parks was born Rosa Louise McCauley, to James McCauley and Leona Edwards McCauley, in Tuskegee, Alabama, on February 4, 1913. Following her parents’ separation, Parks moved with her mother and younger brother to her maternal grandparents’ home in Pine Level, Alabama, just outside of Montgomery. She was educated at Montgomery’s Industrial School for Girls. At age sixteen, Parks suspended her studies to help support her family.

Though Parks was certainly aware of the daily injustices visited upon African Americans through Jim Crow segregation laws, she was not an early activist for racial equality. In 1932, she married Montgomery barber Raymond Parks who was active in the local NAACP chapter. With her husband’s encouragement, Parks completed her high school education in 1933. Parks worked as a seamstress at the Montgomery Fair department store. But it was through a job at Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery that Parks got her first taste of integration.

Parks did not join the NAACP until 1943, when she began serving as secretary to E.D. Nixon, who was the Montgomery chapter president from 1943 to 1957. As Nixon’s secretary, Parks had a front row seat to the various indignities faced by Montgomery’s African American community. In the summer of 1955, as Parks became more deeply committed to the civil rights struggle, she attended a training session at the Highlander Folk School (now the Highlander Center) in Monteagle, Tennessee; the Highlander Folk School, which began to train labor activists, served as a training ground for civil rights activists, including Martin Luther King, Jr . By year’s end, Parks was able to put to use some of the training she’d received in Monteagle.

On December 1, 1955, following her day of work at Montgomery Fair department store, Parks boarded a city bus and took her seat in the “colored” section. As the number of white passengers grew, the bus driver came to the “colored” section (which was determined with the use of a moveable sign placed in the aisle) to move the sign so as to increase the number of seats available to white passengers. It was at that point that Parks decided that she was not going to get up and move to a row behind her. The bus driver called the police, and Parks was arrested for violating Montgomery’s segregation laws.

By December 4, 1955, plans were in place for a one day boycott of the Montgomery city buses. Parks’s trial was December 5, the same day as the one day boycott; she was found guilty of disorderly conduct and violating Montgomery’s segregation law. The boycott, however, was an overwhelming success, because the vast majority of Montgomery’s African American community participated. It led to the creation of the Montgomery Improvement Association (MIA), and a young Martin Luther King, Jr. , was elected as the association’s president. Ultimately, the MIA extended the boycott and the the African American community of Montgomery stayed off city buses until December 20, 1956, following the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Browder v. Gayle , which affirmed a lower court’s ruling that segregated seating on public buses was unconstitutional.

Parks’s arrest took a toll on the Parks family; both Rosa and Raymond Parks ended up unemployed (through a firing and a resignation, respectively). The Parks left Montgomery for Hampton, Virginia in 1957, and then relocated permanently to Detroit, Michigan, where Parks found work as a seamstress. However, following the election of John Conyers to the U.S. House of Representatives, Parks was offered a position as receptionist and secretary in Conyers’ Detroit office. Parks remained with the congressman’s office until her retirement in 1988.

In 1980, following the deaths of her husband (1977), brother (1977) and mother (1979), Parks, along with The Detroit News , and the Detroit Public school system, founded the Rosa L. Parks Scholarship Foundation. Parks also co-founded, with Elaine Steele, the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self Development in 1987. Both organizations remain active, and continue to uphold the legacy of Parks.

Parks’s place in the history of the civil rights movement has been recognized and honored by the nation. She was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1996, as well as the Congressional Gold Medal in 1999, for her role in the civil rights movement.

At the age of ninety-two, she passed away in Detroit. President George W. Bush ordered all U.S. flags to be flown at half-staff in her honor. Parks was also given the honor of lying in state in the rotunda of the U.S. Capitol. She was the first woman and the second African American to lie in state. On February 27, 2013, a statue of Parks was unveiled in the National Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol; that statue had been requested by President Bush on December 1, 2005, the 50th anniversary of Parks’s arrest.

Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) offers a variety of ways to engage with its portraits and portrait subjects. Host an exhibit, use our free lesson plans and educational programs, or engage with a member of the AWTT team or portrait subjects.

AWTT has educational materials and lesson plans that ask students to grapple with truth, justice, and freedom.

Exhibits & Community Engagement

AWTT encourages community engagement programs and exhibits accompanied by public events that stimulate dialogue around citizenship, education, and activism.

Contact Us to Learn How to Bring a Portrait Exhibit to Your Community.

We are looking forward to working with you to help curate your own portrait exhibit. contact us to learn about the availability of the awtt portraits, rental fees, space requirements, shipping, and speaking fees. portraits have a reasonable loan fee which helps to keep the project solvent and accessible to as many people as possible. awtt staff is able help exhibitors to think of creative ways to cover these expenses., americans who tell the truth, hear updates from awtt.

Learn more about our programs and hear about upcoming events to get engaged.

Help Support AWTT

Your donations to AWTT help us promote engaged citizenship. Together we will make a difference.

© 2024 Americans Who Tell The Truth

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

Bring Americans Who Tell the Truth (AWTT) original portraits to your community.

Rosa Parks: Activist. Fighter. Hero.

On a chilly day in 1955, an unremarkable scene unfolded in Alabama that would change American history. Aboard a segregated bus, seamstress Rosa Parks was told to surrender her seat so a white man could sit down. It was a moment that had already played out thousands of times in Montgomery, a Southern city languishing under racist Jim Crow laws. But this time, things didn’t follow the script. Parks refused to move.

It was a decision that changed everything.

Removed from the bus and arrested, Parks became a lightning rod for the racial tensions crackling through the South. Led by Martin Luther King, Jr., Montgomery’s Black community boycotted the bus company for a staggering 381 days. It was African-American activism on a scale the US had never seen. It kickstarted the Civil Rights movement .

And it was all down to one woman.

Born at the nadir of US race relations, Parks grew up in a world where racism was a poisonous fact of life. But rather than keep her head low, she fought back. Even before she boarded that bus, she was an activist; a tireless pursuer of justice. Think you already know the real Rosa Parks? We beg to differ.

Strange Fruit

When Rosa Parks was born Rosa Louise McCauley on February 4, 1913, outside Tuskegee, Alabama, it was into a time and place designed to make her feel worthless. Ever since Reconstruction, the South had existed under Jim Crow Laws, forcing whites and Blacks to inhabit different worlds.

Famously, this meant African-Americans eating at segregated luncheon counters; drinking at segregated fountains; and living in separate communities.

But the discrimination went deeper.

In the world of Parks’s childhood, white people were “Mister or Mrs. Collins” – or whatever – while Black people were “James”, or “Malcolm,” or “Rosa”. As an African-American, you were expected to step off the sidewalk for a white person. To give up your seat on the bus. To never speak back.

Those who refused could find themselves fired from their jobs, left permanently unable to find work.

And that was just in the cities.

Out in the countryside, things could get much worse. When Parks was two years old, her parents’ business went under, her father left, and her mother was forced to move in with her parents – Rose and Sylvester Edwards – in rural Pine Level.

It was from her grandfather that young Rosa would get her first taste of activism. Sylvester Edwards’ had a mixed-race background, outwardly appearing to be white.

Yet his exterior masked a well of trauma.

As a child, Edwards had been a slave on a plantation.

He’d been mistreated even by the lamentable standards of the time, refused food until he nearly starved to death. Now a free man, he hated whites with a passion; refusing to show any deference, and often sitting out on the porch with a shotgun in his lap whenever white folk came nosing around.

It was a defiant, admirable attitude.

It was also one that could’ve gotten him killed.

Jim Crow was also the era of lynchings, when 4,400 people – three quarters of them African-American – were murdered by their white neighbors for the smallest perceived infractions. At their height, these lynchings took place out in the open; attracting huge crowds of smiling whites, who held their children up to get a good look at the mutilated body.

It was murder as a party, a carnival. One with a very clear message for Black people:

You could be next.

The same year Parks moved in with Sylvester and Rose Edwards, the Ku Klux Klan was reborn in Georgia, after four decades lying dormant. By 1916, it had spread to Alabama. By the time Parks was ten, it would boast 150,000 members in her home state.

For Parks, that meant a childhood lived beneath a shadow of violence.

As a girl, she would lie awake at nights, listening as the KKK went riding. She heard lynchings. Once, she even witnessed the Klan parade right past her doorway, a show of strength, of white impunity. On that occasion, Slyvester Edwards stood on the porch, shotgun loaded, calmly surveying the crowd. Just daring them to try something.

Yet, despite this backdrop of fear, Parks didn’t let herself be intimidated.

There’s a great story from when she was a girl, of a white boy who shoved her off the sidewalk. Parks calmly stood up, dusted herself off, and then shoved the white boy onto his ass.

The little wuss burst into tears. His mom shrieked at Rosa, demanding to know why she did that.

Parks calmly replied: “I didn’t want to be pushed, seeing how I was not bothering him at all.”

It’s kinda great that, even from this early age, we can see the fire burning in Rosa Parks. Her refusal to be a second-class citizen.

But make no mistake, it was a hard life. On her way to school, white kids would throw rocks at her. During the summers, she was forced to work all day picking cotton to help her family make ends meet. In short, Rosa Parks’ early life was just that of another poor, Black girl suffering under Jim Crow.

But this time, the system would meet its match.

Rather than let herself be ground down, Parks would wind up being the one who helped tear the whole rotten edifice down.

The Activist

Although she was intelligent, bad luck conspired to leave Rosa Parks with little in the way of formal education. Aged 11, she’d joined Miss White’s Industrial School in Montgomery, which had mostly-white teachers and mostly Black students.

But even this amount of mixing was too much for the city, which closed the school down.

Although Parks would start again at a new school, she’d soon be forced to drop out to care for her dying grandma and ill mother. As a result, the only job adult Parks was able to get was as a seamstress in a shirt factory.

Still, something must’ve gone right, because a year later, in 1932, she was introduced to Raymond Parks.

A barber by trade, Raymond was also lacking in formal education. But that didn’t mean he was stupid. Always well dressed, and always read-up on every subject that mattered, Raymond was sharp as a pin, and he knew it.

In his spare time, he organized defense meetings to try and help the Scottsboro Boys – nine African-American teenagers who’d been falsely accused of raping white women. It was dangerous work, and most meetings took place around a table heavy with loaded guns.

But it was also the coolest thing 19-year old Parks had ever heard.

Raymond completely swept her off her feet. He proposed on their second date and, before the year had ended, the two were married. But if Parks had dreamed of getting involved in Raymond’s activism, her dreams would soon be crushed.

Raymond thought it too dangerous. The whole lot of them might get lynched at any time.

So Parks was forbidden from attending the Scottsboro meetings, instead sitting quietly on the porch as the men talked inside.

Still, Raymond was a supportive husband, encouraging her to earn her high school degree, something she did in 1933. After that, it was a series of menial jobs, the most-significant of which took place on an Army Base.

As it became ever-more apparent that another war was looming, the FDR administration had issued an order desegregating Army bases. When Parks began working as a secretary at Maxwell Field just outside Montgomery, she was shocked at life in a fully integrated environment.

She could sit next to whoever she wanted on the bus. Eat in a mixed canteen. Have white women serve her coffee.

She later claimed:

“You might say Maxwell base opened my eyes to how it could be”.

Yet the moment she stepped off the base every evening, it was back. Back to riding in the “Negro” section of the bus. Back to being a second class citizen. Back to a world where being Black meant always looking over your shoulder. As the decades ticked past and Parks turned 30, Raymond began to thaw on the idea of his wife doing activist work.

In 1943, they both joined NAACP, working long hours as volunteers.

For Parks, this was a crazy time.

NAACP charged her with recording racist violence across Alabama. This meant going out and collecting graphic accounts of beatings, whippings, and rapes doled out by whites.

The most horrific was the Recy Taylor case.

In September, 1944, a married Black woman was abducted by a gang of white men, who blindfolded her and took turns sexually assaulting her. In the aftermath, Parks was sent to take her story, only to be menaced by the local sheriff the entire time she was in town.

Although Parks succeeded in making Recy Taylor national news, she couldn’t change the world she lived in.

An all-white jury dismissed the case in five minutes. Although the names of Taylor’s abusers were known, they never faced justice.

Come 1947, Rosa Parks was famous across Alabama as a fiery activist. She even gave a speech that year at the local NAACP convention, for which she received a standing ovation. But it wouldn’t be her Civil Rights work that would make Parks famous.

It would be a single bus ride.

Waiting for the Spark

In the entire history of the Civil Rights movement, perhaps no other figure comes across as such a petty dick as James F. Blake. A Montgomery bus driver, Blake was charged with enforcing segregation on his vehicle. Or so he’d have you believe.

In reality, drivers were given discretion over how seriously they took these rules.

So while you got some jobsworths who always made Black people surrender their seats to whites, you also got some who turned a blind eye. But not James Blake. To those who’d ridden his bus, Blake was notorious for being a weapons-grade douche.

He forced Black people to come through the front door to pay, then made them get back off again and get back on via the rear door.

Not only that, he sometimes drove off as they were making their way to the back of the bus, leaving them penniless and without a ride in the freezing cold. Congratulations, James Blake. You’re being discussed on a channel that has made videos on Stalin, and you’re still somehow the pettiest tyrant we’ve ever encountered.

Rosa Parks actually had a run-in with Blake during her early days as a NAACP investigator.

In 1943, she boarded his bus through the front door, paid for her ticket, then refused to get back off and go to the rear door. The incident ended with Blake grabbing her arm and shouting at her until Parks ran from the bus. Given what we know of Rosa Parks today, it can seem odd that she was involved in a separate bus incident 12 years earlier.

But that’s only because we’re looking with hindsight.

In 1943, or even in 1952, there was no evidence that the spark for Civil Rights might come from segregated buses. 1943 Parks wasn’t all like “Great! I’ll do this again in a decade and watch the world change!”

It was only in 1953 that activists started to see the potential for buses to become a powderkeg.

That’s because 1953 was the year Baton Rouge showed what could be done. That June, a sudden reversal in bus desegregation in the Louisiana capital exploded into direct action. Black churches organized an 8 day boycott of the bus system, costing the company thousands of dollars.

Although the gains made by the end of the boycott were few, they made activists’ ears prick up across the South.

If it could be done in Baton Rouge, why not in – say – Montgomery?

By now, it was clear something was building below the surface of Southern society, a volcano about to erupt. In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v Board of Education that schools must be desegregated. While this was a victory, it was one met with immediate backlash. Just a year later, 14-year old Emmett Till was lynched in Mississippi for answering back to a white woman.

Clearly, whites were still ready to use violence to keep hold of their privilege.

But by now, the Alabama NAACP was already committed to finding a test case for bus desegregation. They nearly succeeded in November, when teenage Claudette Colvin refused to give up her seat to a white person and was arrested and roughed up.

But NAACP discovered she was both pregnant and unmarried, and decided not to pursue her case. Knowing the broadsides that would be launched against whoever headed the test case, they simply couldn’t risk using someone without a spotless reputation.

Another near-miss was Jo Ann Robinson, an educator from Montgomery.

Not long after the Claudette Colvin thing, Robinson got on a bus and deliberately sat in a “whites only” seat. It seems she was trying to spark a confrontation, to get arrested.

But when the driver started screaming and swearing at her, her nerve broke. She left the bus.

And so December, 1955 arrived with the activist community still waiting for the spark. Still waiting for the test case that would give them their shot to blow Jim Crow wide open.

Fortunately, Rosa Parks was about to become that spark.

Battleground

December 1, 1955 was a chilly day in Montgomery. It was also a busy day, at least if your name was Rosa Parks.

By now, Parks was working in a department store fixing dresses. With Christmas approaching, it was already a busy time, and Parks had her NAACP work on top of that. She spent her entire coffee break making NAACP calls, and her lunch hour meeting with a lawyer to discuss a case.

By the time she left the building at 5pm, she was tired as a dog.

The line at her regular bus stop was crazy, so she ran some errands. By the time she came back, the queue had thinned out a little. A bus pulled up. Parks got on, and took a seat beside a African-American man in the middle section known as “No Man’s Land.”

These were the undesignated seats, the ones theoretically reserved for neither whites nor Blacks.

In practice, though, the drivers would often eject Black people from these rows when whites were forced to stand. Especially if the driver just happened to be an epic dick.

Care to guess who was driving Rosa’s bus that day?

As the bus moved on, it got busier. Two more Black people came to sit in the same row as Parks. Eventually, the bus was so full that a white man was forced to stand. It’s at this point that James Blake did what James Blake did best.

The driver came to the row Parks was sat on, and told all four Black people to move.

When everyone refused, he threatened to call the cops. One by one, the other three wearily stood and went to the back.

But not Rosa.

Instead of leaving, she slid across to the window, showing she had no intention of moving. To this day, it’s uncertain what was going through her head. The Rev. Jesse Jackson once claimed she was thinking of poor, lynched Emmett Till:

“Rosa said she thought about going to the back of the bus. But then she thought about Emmett Till and she couldn’t do it.”

The popular story is that she was just tired – from work, from being treated like garbage. Another view is that Parks was all too aware the NAACP needed its test case, and had decided it would be her.

Blake ordered her to get up. Parks refused. He threatened to call the police, to which she calmly replied:

“You may do that.”

So Blake did.

What’s interesting is that the policemen were just as unhappy with Blake’s bull poop as everyone else. They tried to defuse the situation, but when neither Blake nor Parks would budge,they reluctantly led Rosa Parks away. Parks later said they asked her:

“Why didn’t you just stand up?”

“I don’t know,” she replied, “why do you push us around?”

“I don’t know. The law’s the law.”

After that, it was a trip to the local jail. There, Parks used her phonecall to notify Raymond, who freaked out, terrified she’d be assaulted in her cell. But no. All that happened was that Parks was fingerprinted, and then spent the night behind bars.

As she slept, though, the wheels were already turning.

Through Raymond, NAACP and other groups found out about the arrest. Across the night, some 35,000 flyers were distributed across Montgomery’s Black communities, calling for a bus boycott. Children brought the flyers home from school. Black churches urged their congregations to boycott the buses that Monday.

One of the preachers doing that urging was a 26-year old called Martin Luther King, Jr.

New in town, and virtually unknown even in Alabama, Doctor King had no intentions of becoming a household name.

Yet the stage was now being set for his own dizzying rise to prominence.

By Sunday evening, the citizens of Montgomery were ready. As he went to bed that night, MLK confided that he’d consider the boycott a success if only 60% of Black riders participated. Little could he have known that the real figure would exceed his wildest dreams.

Direct Action

On Monday, December 5, 1955 Rosa Parks went on trial.

The proceedings were fairly undramatic. Parks was fined $10 and ordered to pay $4 court costs – a pretty small sum even in 1955.

But the real action was happening outside.

That morning, Doctor King had awoken to a jaw-dropping sight. Nearly all the buses in Montgomery’s Black areas were empty. Far from stopping at 60% of riders, the boycott had pulled in nearly 100%.

And so began the most-legendary boycott in US history. For 381 days, Montgomery’s Black citizens avoided the buses, using creative means to get to and from work. At first, cabs charged African-American riders only ten cents, but the City passed a spiteful law forcing them to charge a minimum of 45.

So the Black community organized a community taxi system, which made scheduled rides around town, acting like a sort of back-up bus.