8:30 AM – 5:30 PM, MON – FRI

Dispute Resolution, Litigation, Arbitration

Republic Act No. 11313 or “The Safe Spaces Act” - Addressing Gender-Based Sexual Harassment

On April 17, 2019, the Safe Spaces Act, or previously the “Bawal Bastos” bill, was signed into law.

With the aim of ensuring an individual’s sense of personal space and public safety, the Safe Spaces Act addresses gender-based sexual harassment in public areas such as streets, privately-owned places open to the public, and public utility vehicles, among others. It also extends the protection even to cyberspace, and provides for prohibited acts and their corresponding penalties. Below is a summary of the acts punished under the Safe Spaces Act and their corresponding penalties:

Local government units are mandated to pass ordinances localizing the applicability of the Safe Spaces Act. The Metro Manila Development Authority (MMDA), the Philippine National Police (PNP), and the Women and Children’s Protection Desk (WCPD) of the PNP have been given the task of apprehending violators of the law. With regard to online cases, the task falls on the Anti-Cybercrime Group of the PNP (PNPACG).

In addition to penalizing acts of gender-based sexual harassment in public places, the Safe Spaces Act also expands the 1995 Anti-Sexual Harassment Act. Formerly, sexual harassment was only punished when committed by someone who has authority, influence, or moral ascendancy over the victim. Under the Safe Spaces Act, acts committed between peers, by a subordinate to a superior officer, by a student to a teacher, or by a trainee to a trainer are now covered as punishable sexual harassment.

Click here to read the entire text of RA No. 11313 including the complete list of prohibited acts.

Share This Article

Disclaimer: The information in this website is provided for general informational purposes only. No information contained in this post should be construed as legal advice from Platon Martinez or the individual author, nor is it intended to be a substitute for legal counsel on any subject matter. No reader of this post should act or refrain from acting on the basis of any information included in, or accessible through this post without seeking the appropriate legal or other professional advice on the particular facts and circumstances.

Read These Next

Bureau of immigration’s operations during the enhanced community quarantine period, bir extends anew the period for filing of returns and payment of taxes in light of ecq extension, bir revenue memorandum circular no. 86-2018 (11 october 2018).

6th & 7th Floors Tuscan Building 114 V.A. Rufino Street, Legaspi Village, 1229 Makati City, Philippines

Telephone: +63 2 88674696 Fax: +63 2 88671304

© 2024 Platon Martinez. All rights reserved. Powered by Passion.

- AN EMPIRICAL CRITICAL AND COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE PHILIPPINES’ EMERGENCY PATENT LAWS

- PHILIPPINE JURISPRUDENCE ON THE LACK OF DUE PROCESS ISSUE ARISING FROM THE APPLICATION OF THE DOCTRINE OF PIERCING THE VEIL OF CORPORATE FICTION

- EVALUATING PROPOSALS TO CREATE STRONGER PRIVACY PROTECTIONS FOR VICTIM-SURVIVORS OF HUMAN TRAFFICKING AND MIGRANT SMUGGLING VIS-A-VIS THE CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF SPEECH AND EXPRESSION

- UNDERSTANDING TAXPAYER’S RIGHTS UNDER THE RUN AFTER TAX EVADERS (RATE) PROGRAM

UST Law Review

Leave an Indelible Imprint

R.A. No. 11313: The Safe Spaces Act

On April 2019, the Safe Spaces or “ Bawal Bastos ” law was enacted which seeks to protect any person from gender-based sexual harassment in public spaces. The law seeks to address the many gaps which is not covered by the sexual harassment under the previous legal framework and to promote gender equality wherein persons may be free from duress and any kind of external pressure from doing their ordinary lives.

Of particular importance is the widening of the scope of what constitutes sexual harassment and where it can take place. In sum, the law also contemplates that sexual harassment may also emanate from a colleague and not just from someone in the workplace who is a superior or who has moral ascendancy. In this regard, any person may be an offender if s/he has made a transphobic, sexist comments.

It also contemplates online spaces as part of the “public space”. Before the enactment of this act, sexual harassment may only committed in the workplace, educational or training environment.

The Safe Spaces Act does not, in any way, supersede the Sexual Harassment Act. If the offender qualifies for both offenses under the law, he shall be liable therefor.

Featured Photo by Annie Spratt on Unsplash

Related Posts

R.A. No. 11166: The Philippine HIV and AIDS Policy Act

OCA CIRCULAR NO. 118-2020 (DESTRUCTION OF DANGEROUS DRUGS)

OCA CIRCULAR NO. 130-2020 (RE: VIDEOCONFERENCING HEARINGS)

- More Networks

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- 2024 election

- Kate Middleton

- TikTok’s fate

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

- Gun Violence

Safe spaces, explained

Share this story.

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: Safe spaces, explained

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/50524775/GettyImages-499277772.0.0.jpg)

The term "safe space" often gets thrown around, and mocked, in debates about social justice and free speech on college campuses . To some, safe spaces symbolize the "coddling" of America’s youth, the oversensitivity of modern progressivism, and even a serious threat to free speech.

Take the University of Chicago’s warning to incoming first-year students that made it very clear there would be no safe spaces or trigger warnings.

"Our commitment to academic freedom means that we do not support so-called ‘trigger warnings,’ we do not cancel invited speakers because their topics might prove controversial, and we do not condone the creation of intellectual ‘safe spaces’ where individuals can retreat from ideas and perspectives at odds with their own," reads the letter from Dean of Students Jay Ellison, college newspaper the Chicago Maroon reported this week.

But the term "safe space" also came up recently in a very different context: the horrific mass shooting that killed 49 people at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando. Gay clubs like Pulse are supposed to be "safe spaces," where LGBTQ people can feel welcome and accepted in an often-intolerant world. The violation of that space was a terrible reminder of what that intolerance can lead to.

No space can ever be 100 percent safe — but this is much more true for some groups of people than others. As Vox’s Alex Abad-Santos observed , "The feeling of safety in a gay bar and actual safety are two different things. Though they are connected, there’s no such thing as a safe space for LGBTQ people. LGBTQ people know this better than anyone. We live it, and our history is marred by it."

For people in marginalized groups, psychological safety (or what some would call "coddling") and physical safety are closely related and not easy to separate. That's where the concept of safe spaces is rooted in the first place, and that's why the need to have them is so powerful for so many.

What are safe spaces, and why can they be valuable?

Malcolm Harris has a good brief history of the term "safe space" at Fusion . He cites scholar and activist Moira Kenney’s book Mapping Gay L.A. to explain that the term originated in gay and lesbian bars in the mid-1960s:

With anti-sodomy laws still in effect, a safe space meant somewhere you could be out and in good company — at least until the cops showed up. Gay bars were not "safe" in the sense of being free from risk, nor were they "safe" as in reserved. A safe place was where people could find practical resistance to political and social repression.

This was a time when not only was consensual gay sex against the law in many states but also LGBTQ people couldn’t even dance together or hold hands without risking criminal punishment . Today it's not just legal for same-sex couples to express their affection in public; it’s also much more socially acceptable. But that's unfortunately not true everywhere in the world, much less in the United States.

Even in more tolerant and cosmopolitan areas, though, many LGBTQ people feel they have to maintain a constant background vigilance. "You just learn this behavior where you check the room," Abad-Santos told me. "You know the public places where you can hold your boyfriend's hand, or kiss him, and where you can’t."

So a "safe space" is a place where LGBTQ people don't have to think twice about whether they can show affection for their partners — and whether they can just be themselves.

It's the same basic idea for other groups, like women and people of color, who tend to be less well-represented or well-respected by society at large. People whose voices are quite literally heard less than those of white men, since white men still tend to dominate conversations in media , classrooms , boardrooms , politics , and everyday life .

"For me as a black woman, it's really nice to just go out with other black women sometimes," said Sabrina Stevens, an activist and progressive strategist. "I have to do so much less translation. When you're black around white people, you have to explain every little thing, even with people who are perfectly nice and well-meaning."

You don’t have to explain to other black women why your hair is the way it is, she said, or what a certain word means, or countless other little cultural signifiers. "Everybody has a need to just be able to be themselves somewhere, without having to do that translation and without having to always be on guard to justify yourself."

Stevens describes many different safe spaces that are important to her own life: breastfeeding support groups that are explicitly women-only to help new moms feel more comfortable talking openly about their bodies, or hair salons that function as an informally black-women-only social space as well as a service.

Some safe spaces are intentionally created, like the breastfeeding group. Some groups are exclusive and allow only women or only people of color, for instance, just so that people in those groups can speak more freely about their interests without worrying about whether others will understand what they mean.

Other safe spaces emerge organically, like hair salons, gay clubs, or black churches. The shooting at Mother Emanuel in Charlestown was also a violation of a safe space, which added another layer of devastation to an already terrible crime.

Safe spaces aren't always about literal physical safety from violence; sometimes they're a refuge, a place to relax. Yet emotional states are also physical states. Our mental well-being shapes and is shaped by our neural pathways, our digestive tracts, our muscular tensions, our hormones — especially cortisol, the stress hormone, which is associated with poor health outcomes at consistently high levels. And it causes especially poor health outcomes among groups of people who experience systemic discrimination like racism, which causes the fight-or-flight response to work in low-level, yet incessant, overdrive.

"No one can live in a constant state of vigilance," Stevens said. "Your body is not designed to do that. The need for safe spaces is the need to literally not have your adrenal system constantly firing at full tilt."

Why are safe spaces sometimes controversial?

"Safe spaces" made headlines in a negative way recently when controversy over free speech at Yale erupted over some faculty emails about Halloween costumes and cultural sensitivity. Protests at the University of Missouri also caused controversy over the drastic step of forcing out the president, even though black students were responding to serious racist incidents on campus.

Commentators like Jonathan Chait worry that "political correctness" and "language police" are perverting liberalism. Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt bemoan the " coddling " of students on college campuses, citing anecdotes about "safe space" student groups whose protests have blocked conservative speakers from coming to campus.

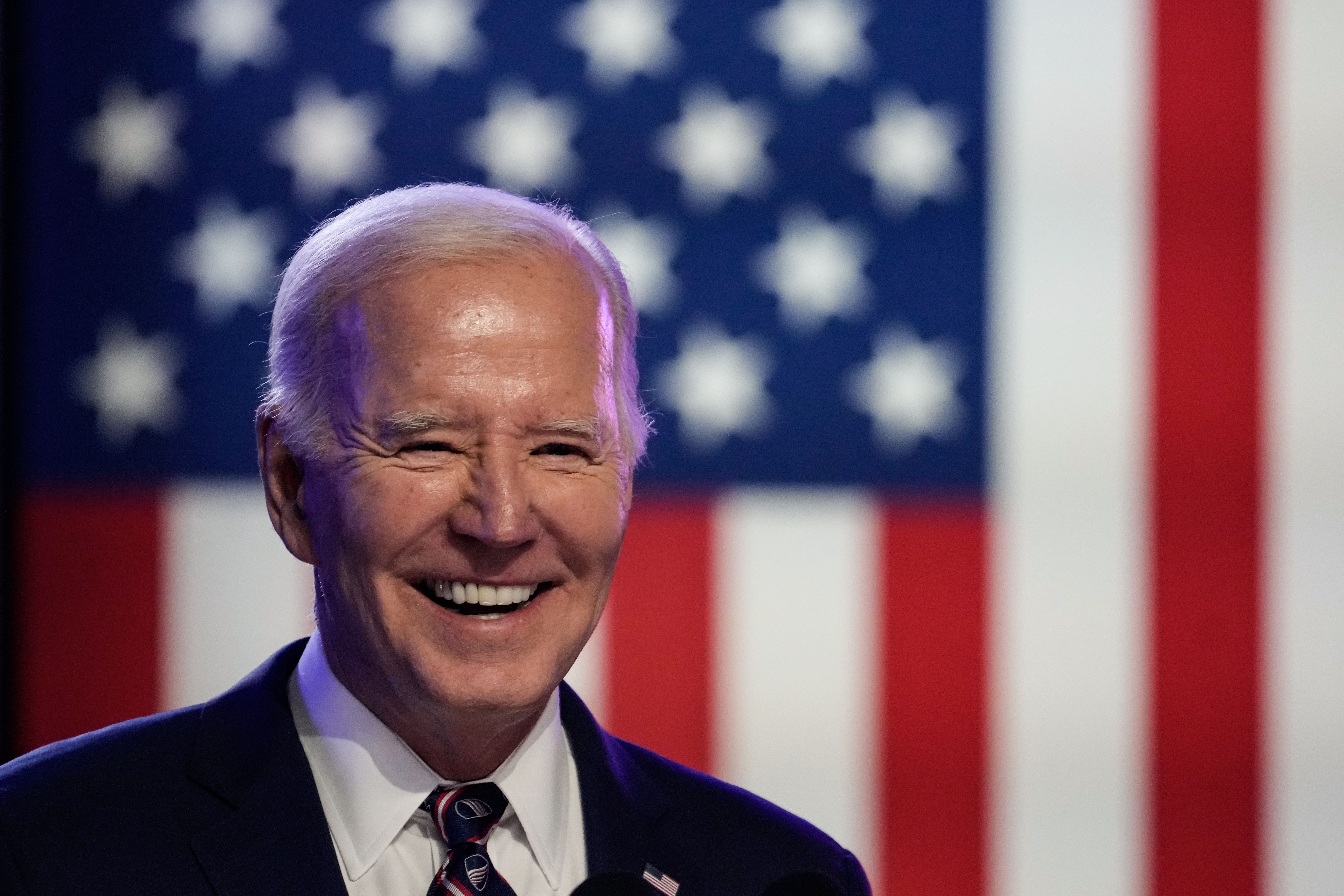

In a recent graduation speech at Howard University, President Obama rebuked these trends:

You can be completely right, and you still are going to have to engage folks who disagree with you. ... So don’t try to shut folks out, don’t try to shut them down, no matter how much you might disagree with them. There's been a trend around the country of trying to get colleges to disinvite speakers with a different point of view, or disrupt a politician’s rally. Don’t do that — no matter how ridiculous or offensive you might find the things that come out of their mouths.

He didn’t use the term "safe space," but some conservative commentators crowed that he had rejected the safe space "culture." On the right, "safe space" has become almost as much of a dirty word as "political correctness."

Some commentators see this culture as worthy of mockery, a sign of liberal intellectual weakness. Some see it as a danger to our society, because we are raising a generation of entitled, infantilized Americans: How will they ever figure out how to toughen up and run the world some day?

Some see "safe space culture" as an even more acute danger — an imminent threat to free speech in a pluralistic society, and even a threat to employment or other ways of life. Some professors say they are terrified that their oversensitive students could force them out of a job.

Others see safe spaces as a threat to social movements they care about, fretting that groupthink could get out of control and cause infighting, shatter unity, and derail important goals. Conor Friedersdorf cautions at the Atlantic that the rhetoric of safety could actually backfire on student activists, and that the often messy work of fighting for social change could be undermined by those who insist on living in a mess-free bubble.

This dynamic can get tense even among groups who consider themselves allies, working toward similar goals. After Black Lives Matter protesters interrupted a presidential forum with Bernie Sanders and Martin O’Malley at the Netroots Nation political conference, the progressive movement erupted into a mini culture war over whether the protest’s tactics were effective or wise, and whose business it really was to judge that.

Finally, a lot of tension over "identity politics" comes from the perception that white men are being discriminated against or at least treated unkindly — that their views are being dismissed simply because of who they are, or that they are being unfairly blamed on a personal level for the problems that marginalized groups face. There’s a perception that "callout culture," or calling people out for saying something problematic or insensitive, has been weaponized, and that a tool intended to curb abuse has itself turned into a tool of abuse .

Should we be worried about safe spaces?

As Amanda Taub wrote for Vox last year, plenty of professors are not terrified of their liberal students — and if their jobs are really so insecure that they could be toppled by student complaints (which are perennial and often unrelated to identity politics), then professors should be a lot more worried about how universities have been steadily disempowering faculty by slashing tenure jobs and relying on poorly paid adjuncts. As Max Fisher noted , sometimes the "PC police" are conservative — and they tend to wield a lot more institutional power than student groups.

Safe spaces also don’t just exist on college campuses, and they’re not just for privileged young people. There’s an argument to be made that we as a society spend way too much time and energy worrying about how students at elite universities choose to spend their time and energy, especially when most of them are young people who are still finding themselves and experimenting with their identities and politics.

Perhaps we should all just relax and trust that the kids will be all right. Perhaps we should also remember that belittling the pain of others is actually an abusive habit , and that emotional safety matters and isn’t something to be mocked. Nor is it always something to be debated, as my colleague Dara Lind noted in an essay on the safe space controversy at Yale.

An op-ed in the Yale Herald was widely mocked for this line: "I don't want to debate. I want to talk about my pain." But given other context from the op-ed, that line makes more sense:

My dad is a really stubborn man. We debate all the time, and I understand the value of hearing differing opinions. But there have been times when I have come to my father crying, when I was emotionally upset, and he heard me regardless of whether or not he agreed with me. He taught me that there is a time for debate, and there is a time for just hearing and acknowledging someone's pain.

Some critics fear that there’s never a time for debate when it comes to safe space culture — that it’s all mushy subjectivity and no analytical rigor , all emotion and no rational perspective. There’s a fear that social justice issues are an impossible minefield of irrationality, that white men in particular can never say anything right, and that marginalized people are always ready to pounce with a new accusation of offense.

But that’s not just a tiresome false choice ; it’s also not true. "There actually is a logic to it — it’s just a logic that people refuse to learn," Stevens said. "You have to be sensitive to and aware of other people and how your actions affect them. That’s a struggle for people who don't typically get asked to do that."

There’s some truth to the argument that safe spaces can sometimes harbor "groupthink," or that they can become toxic or splinter into warring factions. As Harris writes for Fusion:

There are dangers to turning "safe space" into a label of compliance, the way a juice might call itself "organic." One is that, since the ideal is unachievable, people will give up on the aspiration. Another is that it’s alienating to the uninitiated, especially when those in the know come to believe that true respect can only be articulated in their proprietary dialect. A third is, if you’re not careful, the demand for safe space can itself play into existing power relations.

Stevens acknowledges that managing these issues can be tough. "I think there are a lot of situations where people struggle to manage communities well," she said. "It’s very hard when you’re trying to go against the grain and cultivate spaces that don't automatically operate according to the norms that we're used to."

But that’s also true for any community. Strife, power struggles, and difficult social dynamics are a reality almost anywhere you go. And if you’re worried about "groupthink," you might consider taking a look at the broader culture first. Ask yourself: What sort of groupthink have you yourself been subjected to as a result of your own social circles, the area you live in, and the media or social media echo chambers that you consume? White people and other members of dominant cultures have "identity politics" too , even if they don’t acknowledge them as such. In terms of race in the US, white people tend to socialize mostly with other white people, even as they might fret over whether it’s a problem that black schoolchildren "self-segregate" at the lunch table .

Some people get upset because they don’t understand why they can’t be included in a certain group, or why their input on certain issues might not be welcome. A man might ask in good faith whether catcalls are really just "compliments" when women are trying to discuss their own experiences with street harassment, and he might be taken aback when those women get immediately upset or exasperated with him. To him, perhaps he was just asking an innocent question and trying to have an intellectual debate. But to the women, it’s pretty insulting to suggest that their life experiences are up for "debate" — plus they’ve heard remarks like these a hundred times, and nine times out of 10 it just derails the conversation, so they’re just sick of dealing with it.

The question of who belongs and who doesn’t, who is excluded and who isn’t, is a constant worry for most of us. But on top of the personal rejections that everyone faces in life, people in marginalized groups also have to face the feeling that society wasn’t really designed for them; that it considers them an afterthought at best. People in dominant cultural groups are used to rejection, but they’re probably not used to that kind of rejection. And they’re probably not used to being forced to pay attention to all the little social cues and codes that others pick up when trying to navigate a society that isn’t inherently made to fit them.

It’s not easy to deal with shame, hurt feelings, or fear during these kinds of cultural clashes. But particular spaces or identities are rarely the most productive things to blame for the strife. Inside or outside of safe spaces, the real problem is usually a failure of empathy, and the real solution is treating others with humility, respect, and compassion and being willing to learn from our own mistakes.

Correction: An article by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt was originally misattributed to Jonathan Chait.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

At Vox, we believe that clarity is power, and that power shouldn’t only be available to those who can afford to pay. That’s why we keep our work free. Millions rely on Vox’s clear, high-quality journalism to understand the forces shaping today’s world. Support our mission and help keep Vox free for all by making a financial contribution to Vox today.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In The Latest

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

The battle for blame over a deadly terror attack in Moscow

We’re long overdue for an Asian lead on The Bachelor franchise

The House GOP just gave Biden’s campaign a huge gift

Kate Middleton’s cancer diagnosis is part of a frightening global trend

The disappearance of Kate Middleton, explained

3 Body Problem, explained with the help of an astrophysicist

- Have any questions?

- (02) 8579-9170

Safe Spaces Act in the Workplace (R.A. 11313); Gender-Based Sexual Harassment

It is based on the policy of the State to value dignity of every human person and guarantee full respect for human rights. Also, to recognize the role of women in nation-building and ensure the fundamental equality before the law of women and men.

The State also recognizes that both men and women must have equality, security and safety not only in private, but also on the streets, public spaces, online, workplaces and educational and training institutions.

The law also defines gender-based online sexual harassment. It refers to an online conduct targeted at a particular person that causes or likely to cause another mental, emotional or psychological distress, and fear of personal safety, sexual harassment acts including unwanted sexual remarks and comments, threats, uploading or sharing of one’s photos without consent, video and audio recordings, cyberstalking and online identity theft.

Gender-based sexual harassment in the workplace

The crime of gender-based sexual harassment in the workplace includes the following:

- An act or series of acts involving any unwelcome sexual advances, requests or demand for sexual favors or any act of sexual nature, whether done verbally, or physically or through the use of technology such as text messaging or electronic mail or through any other forms of information and communication systems, that has or could have a detrimental effect on the conditions of an individual’s employment or education, job performance or opportunities;

- A conduct of sexual nature and other conduct based on sex affecting the dignity of a person, which is unwelcome, unreasonable, and offensive to the recipient, whether done verbally, physically or through the use of technology such as text messaging or electronic mail or through any other forms of information and communication systems;

- A conduct that is unwelcome and pervasive and creates an intimidating, hostile or humiliating environment for the recipient: Provided, That the crime of gender-based sexual harassment may also be committed between peers and those committed to a superior officer by a subordinate, or to a teacher by a student, or to a trainer by a trainee; and

- Information and communication system refers to a system for generating, sending, receiving, storing or otherwise processing electronic data messages or electronic documents and includes the computer system or other similar devices by or in which data are recorded or stored and any procedure related to the recording or storage of electronic data messages or electronic documents.

Employers or other persons of authority, influence or moral ascendancy in a workplace shall have the duty to prevent, deter, or punish the performance of acts of gender-based sexual harassment in the workplace. Towards this end, the employer or person of authority, influence or moral ascendancy shall:

- Disseminate or post in a conspicuous place a copy of R.A. 11313 to all persons in the workplace;

- Provide measures to prevent gender-based sexual harassment in the workplace, such as the conduct of anti-sexual harassment seminars;

- Create an independent internal mechanism or a committee on decorum and investigation to investigate and address complaints of gender-based sexual harassment which shall:

- Adequately represent the management, the employees from the supervisory rank, the rank-and-file employees, and the union, if any;

- Designate a woman as its head and not less than half of its members should be women;

- Be composed of members who should be impartial and not connected or related to the alleged perpetrator;

- Investigate and decide on the complaints within ten (10) days or less upon receipt thereof;

- Observe due process;

- Protect the complaint from retaliation; and

- Guarantee confidentiality to the greatest extent possible;

- Provide and disseminate, in consultation with all persons in the workplace, a code of conduct or workplace policy which shall:

- Expressly reiterate the prohibition on gender-based sexual harassment;

- Describe the procedures of the internal mechanism created under Section 17 (c) of R.A. 11313; and

- Set administrative penalties

Duties of Employees and Co-Workers

Employees and co-worker shall have the duty to:

- Refrain from committing acts of gender-based sexual harassment;

- Discourage the conduct of gender-based sexual harassment in the workplace;

- Provide emotional or social support to fellow employees, co-workers, colleagues or peers who are victims of gender-based sexual harassment; and

- Report acts of gender-based sexual harassment witnessed in the workplace.

In addition to liabilities for committing acts of gender-based sexual harassment, employers may also be held responsible for:

- Non-implementation of their duties under Section 17 of R.A. 11313, as provided in the penal provisions; or

- Not taking action on reported acts of gender-based sexual harassment committed in the workplace.

Any person who violates subsection (a) of this section, shall upon conviction, be penalized with a fine of not less than Five thousand pesos (PhP5,000.00) nor more than Ten thousand pesos (PhP10,000.00).

Any person who violates subsection (b) of this section, shall upon conviction, be penalized with a fine of not less than Ten thousand pesos (PhP10,000.00) nor more than Fifteen thousand pesos (PhP15,000.00).

Routine Inspection

The Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) for the private sector and the Civil Service Commission (CSC) for the public sector shall conduct yearly spontaneous inspections to ensure compliance of employers and employees with their obligations under R.A. 11313.

Confidentiality

At any stage of the investigation, prosecution and trial of an offense under R.A. 11313, the rights of the victim and the accused who is a minor shall be recognized.

Restraining Order

Where appropriate, the court, even before rendering a final decision, may issue an order directing the perpetrator to stay away from the offended person at a distance specified by the court, or to stay away from the residence, school, place of employment, or any specified place frequented by the offended person.

Related posts

Sexual harassment and its development as women protection in the workplace, relaxation of the rule on mandatory posting of bond in nlrc appeal, execution of the compromise agreement and effect on claim of exemption from labor liability.

‘Safe Spaces Act’ Increases Protections Against Sexual Harassment Online and in Workplaces in Philippines

In April 2019, President Rodrigo Duterte signed into law Republic Act No. 11313 (known as the “Safe Spaces Act”) with the aim of ensuring the equality, security, and safety of every individual, in both private and public spaces, including online and in workplaces.

The law supplements the existing Anti-Sexual Harassment Act of 1995 by broadening the crime of sexual harassment in the workplace to include the following:

- Any act involving any unwelcome sexual advances, requests, or demands for sexual favors or any act of a sexual nature, whether done verbally, physically, or through the use of technology, that has or could have a detrimental effect on the conditions of an individual’s employment, job performance, or opportunities

- Any conduct of a sexual nature or other conduct based on sex affecting the dignity of a person, which is unwelcome, unreasonable, and offensive to the recipient

- Any conduct that is unwelcome and pervasive and creates an intimidating, hostile, or humiliating environment for the recipient

In addition, the law explicitly provides that the crime of gender-based sexual harassment may also be committed between peers, by a subordinate to a superior officer, or by a trainee to a trainer. This widens the scope from that set out in the Anti-Sexual Harassment Act of 1995, which required that for any act to be considered harassment, the offender had to be more senior than the person who was harassed.

Duties of Employers

The law imposes a duty on employers and any other person of authority, influence, or moral ascendancy in the workplace to prevent, deter, or punish acts of gender-based sexual harassment in the workplace. This duty entails disseminating to all persons or posting in a conspicuous place a copy of the applicable law in the workplace, providing measures to prevent gender-based sexual harassment in the workplace, creating an independent internal mechanism or a committee on decorum and investigation to investigate and address complaints, and providing and disseminating a code of conduct or workplace policy. To ensure compliance, the Department of Labor and Employment shall conduct random inspections every year.

Acts of gender-based sexual harassment are punishable by administrative sanctions, without prejudice to other applicable laws. Employers that fail to comply with their duties, including taking action on reported acts of gender-based sexual harassment committed in the workplace, are subject to fines.

Written by Roy Enrico C. Santos and Raya Grace T. Tan of Puyat Jacinto & Santos Law Offices and Roger James of Ogletree Deakins

© 2020 Puyat Jacinto & Santos Law Offices and Ogletree, Deakins, Nash, Smoak & Stewart, P.C.

Fill out the below to receive more information on the Client Portal:

Request webinar recording for ‘safe spaces act’ increases protections against sexual harassment online and in workplaces in philippines, request transcript.

- Full Name *

- Please understand that merely contacting us does not create an attorney-client relationship. We cannot become your lawyers or represent you in any way unless (1) we know that doing so would not create a conflict of interest with any of the clients we represent, and (2) satisfactory arrangements have been made with us for representation. Accordingly, please do not send us any information about any matter that may involve you unless we have agreed that we will be your lawyers and represent your interests and you have received a letter from us to that effect (called an engagement letter). NOTE : Podcast transcripts are reserved for clients (or clients of the firm).

- I agree to the terms of service

Alumni Sign Up

" * " indicates required fields

Rates and Rate Structures

Fill out the form below to receive more information on our rate structures :, fill out the form below to receive more information on od comply:, fill out the form below to share the job ‘safe spaces act’ increases protections against sexual harassment online and in workplaces in philippines.

- Safe Space Act RA11313

Republic of the Philippines

Congress of the Philippines

Metro Manila

Seventeenth Congress

Third Regular Session

Begun and held in Metro Manila, on Monday, the twenty-third day of July, two thousand eighteen

AN ACT DEFINING GENDER-BASED SEXUAL HARASSMENT IN STREETS, PUBLIC SPACES, ONLINE, WORKPLACES, AND EDUCATIONAL OR TRAINING INSTITUTIONS, PROVIDING PROTECTIVE MEASURES AND PRESCRIBING PENALTIES THEREFOR

Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the Philippines in Congress assembled:

Section l . Short Title. – This Act shall be known as the “Safe Spaces Act”.

Sec. 2 . Declaration of Policies. – It is the policy of the State to value the dignity of every human person and guarantee full respect for human rights. It is likewise the policy of the State to recognize the role of women in nation-building and ensure the fundamental equality before the law of women and men. The State also recognizes that both men and women must have equality, security and safety not only in private, but also on the streets, public spaces, online, workplaces and educational and training institutions.

Sec. 3 . Definition of Terms. —As used in this Act;

Catcalling refers to unwanted remarks directed towards a person, commonly done in the form of wolf-whistling and misogynistic, transphobic, homophobic, and sexist slurs;

Employee refers to a person, who in exchange for remuneration, agrees to perform specified services for another person, whether natural or juridical, and whether private or public, who exercises fundamental control over the work, regardless of the term or duration of agreement: Provided, That for the purposes of this law, a person who is detailed to an entity under a subcontracting or secondment agreement shall be considered an employee;

Employer refers to a person who exercises control over an employee: Provided, That for the purpose of this Act, the status or conditions of the latter’s employment or engagement shall be disregarded;

Gender refers to a set of socially ascribed characteristics, norms, roles, attitudes, values and expectations identifying the social behavior of men and women, and the relations between them;

Gender-based online sexual harassment refers to an on the conduct targeted at a particular person that causes or likely to cause another mental, emotional or psychological distress, and fear of personal safety, sexual harassment acts including unwanted sexual remarks and comments, threats, uploading or sharing of one’s photos without consent, video and audio recordings, cyberstalking and online identity theft;

Gender identity and/or expression refers to the personal sense of identity as characterized, among others, by manner of clothing, inclinations, and behavior in relation to masculine or feminine conventions. A person may have a male or female identity with physiological characteristics of the opposite sex, in which case this person is considered transgender;

Public spaces refer to streets and alleys, public parks, schools, buildings, malls, bars, restaurants, transportation terminals, public markets, spaces used as evacuation centers, government offices, public utility vehicles as well as private vehicles covered by app-based transport network services and other recreational spaces such as, but not limited to, cinema halls, theaters and spas; and

Stalking refers to conduct directed at a person involving the repeated visual or physical proximity, non-consensual communication, or a combination thereof that cause or will likely cause a person to fear for one’s own safety or the safety of others, or to suffer emotional distress.

ARTICLE III

Article vii, gender-based streets and public spaces sexual harassment.

Sec . 4 . Gender-Based Streets and Public Spaces Sexual Harassment. – The crimes of gender-based streets and public spaces sexual harassment are committed through any unwanted and uninvited sexual actions or remarks against any person regardless of the motive for committing such action or remarks.

Gender-based streets and public spaces sexual harassment includes catcalling, wolf-whistling, unwanted invitations, misogynistic, transphobic, homophobic and sexist slurs, persistent uninvited comments or gestures on a person’s appearance, relentless requests for personal details, statement of sexual comments and suggestions, public masturbation or flashing of private parts, groping, or any advances, whether verbal or physical, that is unwanted and has threatened one’s sense of personal space and physical safety, and committed in public spaces such as alleys, roads, sidewalks and parks. Acts constitutive of gender-based streets and public spaces sexual harassment are those performed in buildings, schools, churches, restaurants, malls, public washrooms, bars, internet shops, public markets, transportation terminals or public utility vehicles.

Sec. 5 . Gender-Based Sexual Harassment in Restaurants and Cafes, Bars and Clubs, Resorts and Water Parks, Hotels and Casinos, Cinemas, Malls, Buildings and Other Privately-Owned Places Open to the Public. – Restaurants, bars, cinemas, malls, buildings and other privately-owned places open to the public shall adopt a zero-tolerance policy against gender -based streets and public spaces sexual harassment. These establishments are obliged to provide assistance to victims of gender-based sexual harassment by coordinating with local police authorities immediately after gender-based sexual harassment is reported, making CCTV footage available when ordered by the court, and providing a safe gender-sensitive environment to encourage victims to report gender-based sexual harassment at the first instance.

All restaurants, bars, cinemas and other places of recreation shall install in their business establishments clearly-visible warning signs against gender -based public spaces sexual harassment, including the anti- sexual harassment hotline number in bold letters, and shall designate at least one (1) anti-sexual harassment officer to receive gender-based sexual harassment complaints. Security guards in these places may be deputized to apprehend perpetrators caught in flagrante delicto and are required to immediately coordinate with local authorities.

Sec. 6 . Gender-Based Sexual Harassment in Public Utility Vehicles. – In addition to the penalties in this Act, the Land Transportation Office (LTO) may cancel the license of perpetrators found to have committed acts constituting sexual harassment in public utility vehicles, and the Land Transportation Franchising and Regulatory Board (LTFRB) may suspend or revoke the franchise of transportation operators who commit gender-based streets and public spaces sexual harassment acts. Gender-based sexual harassment in public utility vehicles (PUVs) where the perpetrator is the driver of the vehicle shall also constitute a breach of contract of carriage, for the purpose of creating a presumption of negligence on the part of the owner or operator of the vehicle in the selection and supervision of employees and rendering the owner or operator solidarily liable for the offenses of the employee.

Sec. 7 . Gender-Based Sexual Harassment in Streets and Public Spaces Committed by Minors. – In case the offense is committed by a minor, the Department of Social Welfare and Development (DSWD) shall take necessary disciplinary measures as provided for under Republic Act No. 9344, otherwise known as the “Juvenile Justice and Welfare Act of 2006″.

Sec. 8 . Duties of Local Government Units (LGUs). — local government units (LGUs) shall bear prim ary responsibility in enforcing the provisions under Article I of this Act. LGUs shall have the following duties:

Pass an ordinance which shall localize the applicability of this Act within sixty (60) days of its effectivity;

Disseminate or post in conspicuous places a copy of this Act and the corresponding ordinance;

Provide measures to prevent gender-based sexual harassment in educational institutions, such as information campaigns and anti-sexual harassment seminars;

Discourage and impose fines on acts of gender-based sexual harassment as defined in this Act;

Create an anti-sexual harassment hotline; and

Coordinate with the Department of the Interior and Local Government (DILG) on the implementation of this Act.

Sec. 9 . Role of the DILG. – The DILG shall ensure the full implementation of this Act by:

Inspecting LGUs if they have disseminated or posted in conspicuous places a copy of this Act and the corresponding ordinance;

Conducting and disseminating surveys and studies on best practices of LGUs in implementing this Act; and

Providing capacity-building and training activities to build the capability of local government officials to implement this Act in coordination with the Philippine Commission on Women (PCW), the Local Government Academy (LGA) and the Development Academy of the Philippines (DAP).

Sec. 10 . Implementing Bodies for Gender-Based Sexual Harassment in Streets and Public Spaces. – The Metro Manila Development Authority (MMDA), the local units of the Philippine National Police (PNP) for other provinces, and the Women and Children’s Protection Desk (WCPD) of the PNP shall have the authority to apprehend perpetrators and enforce the law: Provided, That they have undergone prior Gender Sensitivity Training (GST). The PCW, DILG and Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT) shall be the national bodies responsible for overseeing the implementation of this Act and formulating policies that will ensure the strict implementation of this Act.

For gender-based streets and public spaces sexual harassment, the MMDA and the local units of the PNP for the provinces shall deputize its enforcers to be Anti-Sexual Harassment Enforcers (ASHE). They shall be deputized to receive complaints on the street and immediately apprehend a perpetrator if caught in flagrante delicto. The perpetrator shall be immediately brought to the nearest PNP station to face charges of the offense committed. The ASHE unit together with the Women’s and Children’s Desk of PNP stations shall keep a ledger of perpetrators who have committed acts prohibited under this Act for purposes of determining if a perpetrator is a first-time, second-time or third-time offender. The DILG shall also ensure that all local government bodies expedite the receipt and processing of complaints by setting up an Anti-Sexual Harassment Desk in all barangay and city halls and to ensure the set-up of CCTVs in major roads, alleys and sidewalks in their respective areas to aid in the filing of cases and gathering of evidence. The DILG, the DSWD in coordination with the Department of Health (DOH) and the PCW shall coordinate if necessary to ensure that victims are provided the proper psychological counsehng support services.

Sec. 11 . Specific Acts and Penalties for Gender-Based Sexual Harassment in Streets and Public Spaces. – The following acts are unlawful and shall be penalized as follows:

For acts such as cursing, wolf-whistling, catcalling, leering and intrusive gazing, taunting, cursing, unwanted invitations, misogynistic, transphobic, homophobic, and sexist slurs, persistent unwanted comments on one’s appearance, relentless requests for one’s personal details such as name, contact and social media details or destination, the use of words, gestures or actions that ridicule on the basis of sex gender or sexual orientation, identity and/or expression including sexist, homophobic, and transphobic statements and slurs, the persistent telling of sexual jokes, use of sexual names, comments and demands, and any statement that has made an invasion on a person’s personal space or threatens the person’s sense of personal safety

The first offense shall be punished by a fine of One thousand pesos (PI,000.00) and community service of twelve hours inclusive of attendance to a Gender Sensitivity Seminar to be conducted by the PNP in coordination with the LGU and the PCW;

The second offense shall be punished by arresto menor (6 to 10 days) or a fine of Three thousand pesos (P3,000.00)

The third offense shall be punished by arresto menor (11 to 30 days) and a fine of Ten thousand pesos (P1O, 000.00).

- For acts such as making offensive body gestures at someone, and exposing private parts for the sexual gratification of the perpetrator with the effect of demeaning, harassing, threatening or intimidating the offended party including flashing of private parts, public masturbation, groping, and similar lewd sexual actions –

The first offense shall be punished by a fine of Ten thousand pesos (P10,000.00) and community service of twelve hours inclusive of attendance to a Gender Sensitivity Seminar, to be conducted by the PNP in coordination with the LGU and the PCW;

The second offense shall be punished by arresto menor (11 to 30 days) or a fine of Fifteen thousand pesos (P15,000.00);

The third offense shall be punished by arresto mayor (1 month and 1 day to 6 months) and a fine of Twenty thousand pesos (P20,000.00).

For acts such as stalking, and any of the acts mentioned in Section 11 paragraphs (a) and (b), when accompanied by touching, pinching or brushing against the body of the offended person; or any touching, pinching, or brushing against the genitalia, face, arms, anus, groin, breasts, inner thighs, face, buttocks or any part of the victim’s body even when not accompanied by acts mentioned in Section 11 paragraphs (a) and (b) –

The first offense shall be punished by arresto menor (11 to 30 days) or a fine of Thirty thousand pesos (P30,000.00), provided that it includes attendance in a Gender Sensitivity Seminar, to be conducted by the PNP in coordination with the LGU and the PCW;

The second offense shall be punished by arresto mayor (1 month and 1 day to 6 months) or a fine of Fifty thousand pesos (P50,000.00);

The third offense shall be punished by arresto mayor in its maximum period or a fine of One hundred thousand pesos (P 100,000.00).

GENDER-BASED ONLINE SEXUAL HARASSMENT

Sec. 12 . Gender-Based Online Sexual Harassment. – Gender-based online sexual harassment includes acts that use information and communications technology in terrorizing and intimidating victims through physical, psychological, and emotional threats, unwanted sexual misogynistic, transphobic, homophobic and sexist remarks and comments online whether publicly or through direct and private messages, invasion of victim’s privacy through cyberstalking and incessant messaging, uploading and sharing without the consent of the victim, any form of media that contains photos, voice, or video with sexual content, any unauthorized recording and sharing of any of the victim’s photos, videos, or any information online, impersonating identities of victims online or posting lies about victims to harm their reputation, or filing false abuse reports to online platforms to silence victims.

Sec. 13 . Implementing Bodies for Gender-Based Online Sexual Harassment. — For gender-based online sexual harassment, the PNP Anti-Cybercrime Group (PNPACG) as the National Operational Support Unit of the PNP is primarily responsible for the implementation of pertinent Philippine laws on cybercrime, shall receive complaints of gender-based online sexual harassment and develop an online mechanism for reporting real-time gender-based online sexual harassment acts and apprehend perpetrators. The Cybercrime Investigation and Coordinating Center (CICC) of the DICT shall also coordinate with the PNPACG to prepare appropriate and effective measures to monitor and penalize gender-based online sexual harassment.

Sec. 14 . Penalties for Gender-Based Online Sexual Harassment. – The penalty of prision correccional in its medium period or a fine of not less than One hundred thousand pesos (P100,000.00) but not more than Five hundred thousand pesos (P500,000.00), or both, at the discretion of the court shall be imposed upon any person found guilty of any gender-based online sexual harassment.

If the perpetrator is a juridical person, its license or franchise shall be automatically deemed revoked, and the persons liable shall be the officers thereof, including the editor or reporter in the case of print media, and the station manager, editor and broadcaster in the case of broadcast media. An alien who commits gender-based online sexual harassment shall be subject to deportation proceedings after serving sentence and payment of fines.

Exemption to acts constitutive and penalized as gender-based online sexual harassment are authorized written orders of the court for any peace officer to use online records or any copy thereof as evidence in any civil, criminal investigation or trial of the crime: Provided, That such written order shall only be issued or granted upon written application and the examination under oath or affirmation of the applicant and the witnesses may produce, and upon showing that there are reasonable grounds to believe that gender-based online sexual harassment has been committed or is about to be committed, and that the evidence to be obtained is essential to the conviction of any person for, or to the solution or prevention of such crime.

Any record, photo or video, or copy thereof of any person that is in violation of the preceding sections shall not be admissible in evidence in any judicial, quasi-judicial, legislative or administrative hearing or investigation.

QUALIFIED GENDER-BASED STREETS, PUBLIC SPACES AND ONLINE SEXUAL HARASSMENT

Sec. 15 . Qualified Gender-Based Streets, Public Spaces and Online Sexual Harassment. – The penalty next higher in degree will be applied in the following cases:

If the act takes place in a common carrier or PUV, including, but not limited to, jeepneys, taxis, tricycles, or app-based transport network vehicle services, where the perpetrator is the driver of the vehicle and the offended party is a passenger:

If the offended party is a minor, a senior citizen, or a person with disability (PWD), or a breastfeeding mother nursing her child;

If the offended party is diagnosed with a mental problem tending to impair consent;

If the perpetrator is a member of the uniformed services, such as the PNP and the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), and the act was perpetrated while the perpetrator was in uniform; and

If the act takes place in the premises of a government agency offering frontline services to the public and the perpetrator is a government employee.

GENDER-BASED SEXUAL HARASSMENT IN THE WORKPLACE

Sec. 16 . Gender-Based Sexual Harassment in the Workplace. – The crime of gender-based sexual harassment in the workplace includes the following:

An act or series of acts involving any unwelcome sexual advances, requests or demand for sexual favors or any act of sexual nature, whether done verbally, physically or through the use of technology such as text messaging or electronic mail or through any other forms of information and communication systems, that has or could have a detrimental effect on the conditions of an individual’s employment or education, job performance or opportunities;

A conduct of sexual nature and other conduct-based on sex affecting the dignity of a person, which is unwelcome, unreasonable, and offensive to the recipient, whether done verbally, physically or through the use of technology such as text messaging or electronic mail or through any other forms of information and communication systems;

A conduct that is unwelcome and pervasive and creates an intimidating, hostile or humiliating environment for the recipient: Provided, That the crime of gender-based sexual harassment may also be committed between peers and those committed to a superior officer by a subordinate, or to a teacher by a student, or to a trainer by a trainee; and

Information and communication system refers to a system for generating, sending, receiving, storing or otherwise processing electronic data messages or electronic documents and includes the computer system or other similar devices by or in which data are recorded or stored and any procedure related to the recording or storage of electronic data messages or electronic documents.

Sec. 17 . Duties of Employers. – Employers or other persons of authority, influence or moral ascendancy in a workplace shall have the duty to prevent, deter, or punish the performance of acts of gender-based sexual harassment in the workplace. Towards this end, the employer or person of authority, influence or moral ascendancy shall:

Disseminate or post in a conspicuous place a copy of this Act to all persons in the workplace;

Provide measures to prevent gender-based sexual harassment in the workplace, such as the conduct of anti-sexual harassment seminars;

Create an independent internal mechanism or a committee on decorum and investigation to investigate and address complaints of gender-based sexual harassment which shall;

Adequately represent the management, the employees from the supervisory rank, the rank-and-file employees, and the union, if any;

Designate a woman as its head and not less than half of its members should be women;

Be composed of members who should be impartial and not connected or related to the alleged perpetrator;

Investigate and decide on the complaints within ten days or less upon receipt thereof;

Observe due process;

Protect the complainant from retaliation; and

Guarantee confidentiality to the greatest extent possible;

Provide and disseminate, in consultation with all persons in the workplace, a code of conduct or workplace policy which shall;

Expressly reiterate the prohibition on gender-based sexual harassment;

Describe the procedures of the internal mechanism created under Section 17(c) of this Act; and

Set administrative penalties.

Sec. 18 . Duties of Employees and Co-Workers Employees and co-workers shall have the duty to:

Refrain from committing acts of gender-based sexual harassment;

Discourage the conduct of gender-based sexual harassment in the workplace;

Provide emotional or social support to fellow employees, co-workers, colleagues or peers who are victims of gender-based sexual harassment; and

Report acts of gender-based sexual harassment witnessed in the workplace.

Sec. 19 . Liability of Employers. – In addition to liabilities for committing acts of gender-based sexual harassment, employers may also be held responsible for:

Non-implementation of their duties under Section 17 of this Act, as provided in the penal provisions: or

Not taking action on reported acts of gender-based sexual harassment committed in the workplace.

Any person who violates subsection (a) of this section, shall upon conviction, be penalized with a fine of not less than Five thousand pesos (P5,000.00) nor more than Ten thousand pesos (P10,000.00).

Any person who violates subsection (b) of this section, shall upon conviction, be penalized with a fine of not less than Ten thousand pesos (P10,000.00) nor more than Fifteen thousand pesos (P 15,000.00).

Sec. 20 . Routine Inspection. – The Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) for the private sector and the Civil Service Commission (CSC) for the public sector shall conduct yearly spontaneous inspections to ensure compliance of employers and employees with their obligations under this Act.

GENDER-BASED SEXUAL HARASSMENT IN EDUCATION AND TRAINING INSTITUTIONS

Sec.21 . Gender Based Sexual Harassment in Educational and Training Institutions. —All schools, whether public or private, shall designate an officer-in-charge to receive complaints regarding violations of this Act, and shall ensure that the victims are provided with a gender-sensitive environment that is both respectful to the victims’ needs and conducive to truth-telling. Every school must adopt and publish grievance procedures to facilitate the filing of complaints by students and faculty members. Even if an individual does not want to file a complaint or does not request that the school take any action on behalf of a student or faculty member and school authorities have knowledge or reasonably know about a possible or impending act of gender -based sexual harassment or sexual violence, the school should promptly investigate to determine the veracity of such information or knowledge and the circumstances under which the act of gender-based sexual harassment or sexual violence were committed, and take appropriate steps to resolve the situation. If a school knows or reasonably should know about acts of gender-based sexual harassment or sexual violence being committed that creates a hostile environment, the school must take immediate action to eliminate the same acts, prevent their recurrence, and address their effects.

Once a perpetrator is found guilty, the educational institution may reserve the right to strip the diploma from the perpetrator or issue an expulsion order.

The Committee on Decorum and Investigation (CODI) of all educational institutions shall address gender-based sexual harassment and online sexual harassment in accordance with the rules and procedures contained in their CODI manual.

Sec. 22 . Duties of School Heads. – School heads shall have the following duties:

Disseminate or post a copy of this Act in a conspicuous place in the educational institution;

Provide measures to prevent gender-based sexual harassment in educational institutions, like information campaigns:

Create an independent internal mechanism or a CODI to investigate and address complaints of gender-based sexual harassment which shall:

Adequately represent the school administration, the trainers, instructors, professors or coaches and students or trainees, students and parents, as the case may be;

Ensure equal representation of persons of diverse sexual orientation, identity and/or expression, in the CODI as far as practicable;

Investigate and decide on complaints within ten (10) days or less upon receipt thereof;

Guarantee confidentiality to the greatest extent possible.

Provide and disseminate, in consultation with all persons in the educational institution, a code of conduct or school policy which shall:

Prescribe the procedures of the internal mechanism created under this Act; and

Sec. 23 . Liability of School Heads. —In addition to liability for committing acts of gender-based sexual harassment, principals, school heads, teachers, instructors, professors, coaches, trainers, or any other person who has authority, influence or moral ascendancy over another in an educational or training institution may also be held responsible for:

Non-implementation of their duties under Section 22 of this Act, as provided in the penal provisions; or

Failure to act on reported acts of gender-based sexual harassment committed in the educational institution.

Any person who violates subsection (b) of this section, shall upon conviction, be penalized with a fine of not less than Ten thousand pesos (P10,000.00) nor more than Fifteen thousand pesos (P15,000.00).

Sec. 24 . Liability of Students. – Minor students who are found to have committed acts of gender-based sexual harassment shall only be held liable for administrative sanctions by the school as stated in their school handbook.

Sec. 25 . Routine Inspection. – The Department of Education (DepEd), the Commission on Higher Education (CHED), and the Technical Education and Skills Development Authority (TESDA) shall conduct regular spontaneous inspections to ensure compliance of school heads with their obligations under this Act.

COMMON PROVISIONS

Sec. 26 . Confidentiality. – At any stage of the investigation, prosecution and trial of an offense under this Act, the rights of the victim and the accused who is a minor shall be recognized.

Sec. 27 . Restraining Order. – Where appropriate, the court, even before rendering a final decision, may issue an order directing the perpetrator to stay away from the offended person at a distance specified by the court, or to stay away from the residence, school, place of employment, or any specified place frequented by the offended person.

Sec. 28 . Remedies and Psychological Counselling. – A victim of gender- based street, public spaces or online sexual harassment may avail of appropriate remedies as provided for under the law as well as psychological counselling services with the aid of the LGU and the DSWD, in coordination with the DOH and the PCW. Any fees to be charged in the course of a victim’s availment of such remedies or psychological counselling services shall be borne by the perpetrator.

Sec. 29 . Administrative Sanctions. —Above penalties are without prejudice to any administrative sanctions that may be imposed if the perpetrator is a government employee.

Sec. 30 . Imposition of Heavier Penalties. – Nothing in this Act shall prevent LGUs from coming up with ordinances that impose heavier penalties for the acts specified herein.

Sec. 31 . Exemptions. —Acts that are legitimate expressions of indigenous culture and tradition, as well as breastfeeding in public shall not be penalized.

FINAL PROVISIONS

Sec. 32 . PNP Women and Children’s Desks. – The women and children’s desks now existing in all police stations shall act on and attend to all complaints covered under this Act. They shall coordinate with ASHE officers on the street, security guards in privately-owned spaces open to the public, and anti-sexual harassment officers in government and private offices or schools in the enforcement of the provisions of this Act.

Sec. 33 . Educational Modules and Awareness Campaigns. – The PCW shall take the lead in a national campaign for the awareness of the law. The PCW shall work hand-in-hand with the DILG and duly accredited women’s groups to ensure all LGUs participate in a sustained information campaign and the DICT to ensure an online campaign that reaches a wide audience of Filipino internet-users. Campaign materials may include posters condemning different forms of gender-based sexual harassment, informing the public of penalties for committing gender-based sexual harassment, and infographics of hotline numbers of authorities.

All schools shall educate students from the elementary to tertiary level about the provisions of this Act and how they can report cases of gender-based streets, public spaces and online sexual harassment committed against them. School courses shall include age -appropriate educational modules against gender-based streets, public spaces and online sexual harassment which shall be developed by the DepEd, the CHED, the TESDA and the PCW.

Sec. 34 . Safety Audits. – LGUs are required to conduct safety audits every three (3) years to assess the efficiency and effectivity of the implementation of this Act within their jurisdiction . Such audits shall be multisectoral and participatory, with consultations undertaken with schools, police officers, and civil society organizations.

Sec. 35 . Appropriations. – Such amounts as may be necessary for the implementation of this Act shall be indicated under the annual General Appropriations Act (GAA). National and local government agencies shall be authorized to utilize their mandatory Gender and Development (GAD) budget, as provided under Republic Act No. 9710, otherwise known as “The Magna Carta of Women” for this purpose. In addition, LGUs may also use their mandatory twenty percent (20%) allocation of their annual internal revenue allotments for local development projects as provided under Section 287 of Republic Act No. 7160, otherwise known as the “Local Government Code of 1991”.

Sec. 36 . Prescriptive Period. – Any action arising from the violation of any of the provisions of this Act shall prescribe as follows:

Offenses committed under Section 11(a) of this Act shall prescribe in one (1) year;

Offenses committed under Section 11(b) of this Act shall prescribe in three (3) years;

Offenses committed under Section 11(c) of this Act shall prescribe in ten (10) years;

Offenses committed under Section 12 of this Act shall be imprescriptible; and

Offenses committed under Sections 16 and 21 of this Act shall prescribe in five (5) years.

Sec. 37 . Joint Congressional Oversight Committee. – There is hereby created a Joint Congressional Oversight Committee to monitor the implementation of this Act and to review the implementing rules and regulations promulgated. The Committee shall be composed of five (5) Senators and five Representatives to be appointed by the Senate President and the Speaker of the House of Representatives, respectively. The Oversight Committee shall be co-chaired by the Chairpersons of the Senate Committee on Women, Children, Family Relations and Gender Equality and the House Committee on Women and Gender Equality.

Sec. 38 . Implementing Rules and Regulations (IRR). – Within ninety (90) days from the effectivity of this Act, the PCW as the lead agency, in coordination with the DILG, the DSWD, the PNP, the Commission on Human Rights (CHR), the DOH, the DOLE, the DepEd, the CHED, the DICT, the TESDA, the MMDA, the LTO, and at least three (3) women’s organizations active on the issues of gender-based violence, shall formulate the implementing rules and regulations (IRR) of this Act.

Sec. 39 . Separability Clause. —If any provision or part hereof is held invalid or unconstitutional, the remaining provisions not affected thereby shall remain valid and subsisting.

Sec. 40 . Repealing Clause. – Any law, presidential decree or issuance, executive order, letter of instruction, administrative order, rule or regulation contrary to or inconsistent with the provisions of this Act is hereby repealed, modified or amended accordingly.

Sec. 41 . Effectivity. – This Act shall take effect fifteen days after its publication in the Official Gazette or in any two (2) newspapers of general circulation in the Philippines.

GLORIA MACAPAGAL-ARROYO

Speaker of the House of Representatives

VICENTE C. SOTTO III

President of the Senate

This Act which is a consolidation of Senate Bill No. 1558 and House Bill No. 8794 was passed by the Senate of the Philippines and the House of Representatives on February 6, 2019.

DANTE ROBERTO G. MALING

Acting Secretary General, House of Representative

MYRA MARIE D. VILLARICA

Secretary of the Senate

Approved: April 17, 2018

RODRIGO ROA DUTERTE

President of the Philippines

- Subscribe Now

[OPINION] Enough is enough: Where are the safe spaces?

Already have Rappler+? Sign in to listen to groundbreaking journalism.

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

![safe space act essay [OPINION] Enough is enough: Where are the safe spaces?](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2021/02/sexual-harassment-school-part1.jpg)

More and more young people have been speaking out in recent years about their experiences of sexual harassment by adults in their campuses. Despite the enactment of progressive laws to protect the youth, the issue of sexual harassment on campuses has grown disturbing over the years. One of these laws is Republic Act No. 11313 or The Safe Spaces Act (Bawal Bastos Law) which “covers all forms of gender-based sexual harassment (GBSH) committed in public spaces, educational or training institutions, workplaces, and online spaces.”

RA 11313 was meant to enhance accountability processes by requiring schools to “take prompt action to eradicate the same actions [of sexual harrassment or violence], prevent their recurrence, and treat their impacts,” but in practice, this seldom transpired as intended.

Recent allegations of sexual abuse at the Philippine High School for the Arts, an instituton that bills itself as a “haven for young artists,” have come to light. Students as young as 11 years old are placed in the care of predators who pose as mentors in a remote area of Mt. Makiling. Stories of abuse are told by students and alumni throughout generations, and they reflect the institution’s callousness and lack of enforcement of our laws. Campus predators should not be accorded the honor of resignation, yet in response to the ongoing student uproar, a predator was asked to merely resign from his post as Admin Officer IV, and unfortunately the issue died down but the predicament remained..

[EDITORIAL] Sagipin ang mga bata

![safe space act essay [EDITORIAL] Sagipin ang mga bata](https://www.rappler.com/tachyon/2022/07/animated-philippine-highschool-for-the-arts-abuse-carousel.jpg?fit=449%2C449)

The restrictions of the Safe Spaces Act were clearly obvious in the PHSA case because it was reliant on how school administrators handled the situation. Because no predator has ever been brought to justice, cases in schools and colleges have steadily risen. To quash the controversy and restore the school’s image, the administrators would simply expel the predator from the premises. The predator need only transfer to a different university to victimize another set of students, while the victims suffer a lifetime of trauma from the incident.

Then recently, in Bacoor National High School-Main Campus, there have been recent reports of sexual harassment as early as the first day of classes. Students claim that incidents like these began in the year 2012; there have also been reports of an entire batch of students victimized by predators. Again, the DepEd issued its standard line of investigating the controversy but with our toothless laws we have and passive and flawed policies governing the conduct of teachers, many of whom, including myself, are not optimistic of its outcomes.

DepEd probes 6 Cavite teachers for alleged sex abuse

Furthermore, despite the transition to the new normal that led to distance learning, campus predators remain present despite online classrooms. Teenage pregnancies, domestic violence, and child sexual exploitation are all on the rise. In 2019, 2,411 girls between the ages of 10 and 14 who were classified as extremely young adolescents gave birth, about seven every day. The PopCom estimated that 70,755 families were headed by minors at the end of 2020. Compared to 2019 data, the number of financial transactions related to the sexual exploitation of children has increased by 2.5 times. Under the anti-poor distance learning program, desperate students sold explicit images and videos online to pay for their education or purchase gadgets for classes. With the youth’s vulnerability and hardships in coping with online classes, it is easy to conclude that campus predators prevailed the past two years.

Besides the aforementioned schools, there have been various campaigns and slogans on the issue of campus predators in the past years. Among them are PSHS-Ilocos, FEU High School, UP Visayas, St. Theresa’s College-QC, Miriam College High School, St. Paul College Pasig, and Marikina Science High School.

However, each case was regarded as a local, school-level problem, and was addressed as such rather than resulting in broader policy changes. Due to the failure of campaigns and the persisting menace, gender justice advocates must adopt a new strategy to weave all the local struggles into a sectoral and national struggle to once and for all stamp out predators and compel the government to take a more proactive stance.

Hontiveros seeks Senate probe into sexual harassment cases in schools

Case in point, the Philippine Teachers Professionalization Act of 1994 and the Code of Ethics for Professional Teachers do not specifically mention gender-based violence and abuse as a reason for license revocation or professional misconduct. It is obvious that these institutions and regulations have failed to safeguard the young from on-campus predators and will continue to fail to do so without reforms.

The instructor’s license should be revoked as part of the punishment. They ought to be placed on a blacklist and prohibited from employment that involves vulnerable sections of the population. They shouldn’t receive any compensation nor benefits. They ought to be locked up in jail for a very long time. Additionally, a national registry of offenders should be established. School gender desks and complaint procedures are insufficient to stop campus predators. However, university administrators want to avoid doing this because they do not want the school’s reputation to be tarnished. The reputation of institutions should not take precedence over the interests of the students.

On top of all of these issues and concerns, another striking aspect of the campaign to rid our campuses of predators is the social stigma that comes with being involved in such a controversy. Very few cases reach the desks of the fiscals because, let’s face it, besides our ailing institutions that have failed to protect the youth, parents, relatives, friends, and classmates have gaslighted the victims into making them think that attaining justice is a far-fetched idea, and that the consequences of fighting back is just too much to handle.

The time is now for victims and advocates to band together and collectively declare, enough is enough. – Rappler.com

Gel Panlilio, 20, is a feminist and member of Samahan ng Progresibong Kabataan.

Add a comment

Please abide by Rappler's commenting guidelines .

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.

How does this make you feel?

Related Topics

Recommended stories, {{ item.sitename }}, {{ item.title }}, sexual assault, how can philippine laws better protect rape victims.

Japanese ex-soldier wins US award for her fight against sexual harassment

‘American Idol’ star Paula Abdul sues producer Nigel Lythgoe for sexual assault

Vin Diesel hit with sexual battery lawsuit by former assistant

Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs accused of 1991 sexual assault in second lawsuit

Checking your Rappler+ subscription...

Upgrade to Rappler+ for exclusive content and unlimited access.

Why is it important to subscribe? Learn more

You are subscribed to Rappler+

Teaching & Learning

- Education Excellence

- Professional development

- Case studies

- Teaching toolkits

- MicroCPD-UCL

- Assessment resources

- Student partnership

- Generative AI Hub

- Community Engaged Learning

- UCL Student Success

Creating safe spaces for students in the classroom

Providing a safe space for students to grow and learn where they feel their voice is heard has a large impact on their learning and well-being. This guide contains tips on how to create this space.

27 April 2020

Holley and Steiner (2005) propose a safe space is:

“The metaphor of the classroom as a ‘safe space’ has emerged as a description of a classroom climate that allows students to feel secure enough to take risks, honestly express their views and share and explore their knowledge, attitudes and behaviours.

Safety in this sense does not refer to physical safety. Instead classroom safe space refers to protection from psychological or emotional harm…

Being safe is not the same as being comfortable. To grow and learn, students must confront issues that make them uncomfortable and force them to struggle with who they are and what they believe.” (p.50)

What are microaggressions?

Sue et al. (2007) define microaggressions as:

“are brief and commonplace daily verbal, behavioural or environmental indignities, whether intentional or unintentional, that communicate hostile, derogatory, or negative racial slights and insults toward people of colour.” (p.271)

Some examples of microaggressions include:

- Inappropriate jokes

- Stereotyping

- Exclusion from groups and/or being dismissed or ignored

- Not learning names

- Denial of racial reality

Whilst microaggressions are typically subtle and interpersonal, macroaggressions are often overt and occur at a systemic level.

Understanding race and racism in higher education

Warmington (2018) states:

“The greatest barrier to addressing race equality in higher education is academia’s refusal to regard race as a legitimate object of scrutiny, either in scholarship or policy. Consequently, there is little recognition of the role played by universities in (re)producing racial injustice.”

It is important to recognise and address the ways in which we as individuals, as well as an institution, ‘contribute to academia’s racialised culture and practices’ (Warmington, 2018).

This is explored in detail in Arday and Mirza’s (2018) work, Dismantling Race in Higher Education . The book contains a collection of essays which explore the ideology of whiteness and the roots of structural racism in the academy.

Understanding the decolonise movement

There are increasing calls to decolonise the university and curriculum across the sector.