News from the Columbia Climate School

How Landing on the Moon Changed Our World

Nicole deRoberts

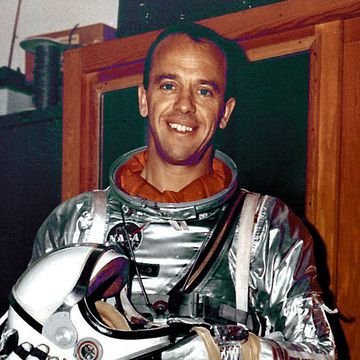

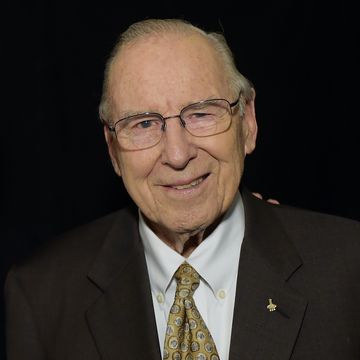

Sean Solomon has served as the director of Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory since 2012. Much of his recent research has focused on the geology and geophysics of the solar system’s inner planets. He was the principal investigator for NASA’s MESSENGER mission , which sent the first spacecraft to orbit Mercury and study the planet’s composition, geology, topography, gravity and magnetic fields, exosphere, magnetosphere, and heliospheric environment.

The beginning of Solomon’s research career coincided with the birth of a new field — planetary science. Below, he explains how Apollo 11 affected the scientific community at that time, how Lamont was involved, and what comes next for lunar exploration.

Solomon discussed these topics and more during a panel discussion entitled “ Small Steps and Giant Leaps: How Apollo 11 Shaped Our Understanding of Earth and Beyond ” on July 17. The event, hosted in celebration of the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 lunar landing, was co-sponsored by the American Geophysical Union and the National Archives.

At what point were you in your career when Apollo 11 landed the first humans on the Moon?

I was a graduate student at MIT, and I was doing a thesis in seismology. However, I had written a paper about the interior structure of the Moon before the Apollo 11 mission. MIT faculty and students were holding discussions about the Moon in advance of the Apollo 11 landing, so we were primed to think about the impact of the mission’s findings.

How did the Moon landing affect you personally?

I was glued to the television set watching the landing and the Moon walks like everybody else. It was a singular event in history for humans to walk on another planetary body. It captivated everyone. The landing and Neil Armstrong’s first steps onto the lunar surface were watched, I would guess, by billions of people on this planet. So, it was a great event for the world’s population to come together and marvel at a profound technological achievement.

In terms of my own work, the mission led to an explosion of new data about the Moon. I included lunar work in my research agenda for a number of years thereafter, using data from all of the Apollo missions, from the findings of sample analyses to the observations from the orbital and surface experiments that Apollo carried.

How did this mission affect the scientific community as a whole?

There was really no field of planetary science in 1969, just a handful of people who called themselves planetary astronomers and studied other worlds through telescopes or with theoretical work. NASA had sent spacecraft to Venus and Mars by the time of Apollo 11, so there were a few people who were working on planetary data, but the space age was less than 12 years old at the time of the first Moon landing. Almost everybody who worked on the scientific return from the Apollo program came from other fields — earth science, chemistry, or physics — and they became lunar scientists. NASA’s investments brought in huge numbers of scientific experts and funded new instruments and labs across the county to create a lunar community that hadn’t been there before.

It’s also important to remember that nearly coincident with the Apollo program was an explosion of robotic missions to explore other parts of the solar system. Within a few years of Apollo 11 we had launched spacecraft to fly by Mars, Venus, Mercury, Jupiter, and Saturn. It was an enormous expansion of our presence in space that was enabled by a healthy NASA built up to conduct the Apollo missions but an agency that also had the budget and the engineering expertise to figure out how to explore the rest of the solar system by spacecraft. The field of planetary science came into its own in those few years after Apollo.

Can you tell me a little bit about Lamont’s involvement with Apollo 11?

Lamont was very heavily involved in the Apollo program and was much more active in planetary research than it is now. There were Lamont scientists who were in line to receive some of the first samples brought back from the Moon. At least equally importantly, Lamont was a leader in the geophysical exploration of the Moon. Over the course of the Apollo missions there were several geophysical experiments, but the one that spanned nearly all of the missions was the passive seismic experiment . And several early Lamont seismologists had teamed together to put that experiment on Apollo, including Maurice Ewing, Frank Press, Gary Latham — the principal investigator — and other team members from Lamont as well.

In later Apollo missions, astronauts measured the heat flowing out from the lunar interior. The Apollo Heat Flow Experiment was led by Marcus Langseth, a Lamont scientist for whom our current research ship is named. Also, during the Apollo 17 mission, there was a gravimeter that was mounted on the astronauts’ rover to measure the variation in lunar gravity over the course of the rover traverse. That experiment was led by Manik Talwani, who by then was the Lamont director.

Ewing was studying seismology in the ocean basins before he was contacted by NASA. How does that relate to studying seismology on the Moon?

Ewing pioneered the use of seismology to study the crust beneath the oceans. He took seismic experiments to a venue where there had never been such experiments before. And with them he showed that oceanic crust is different from continental crust. So when he had the opportunity to send a seismometer to the Moon, it was another chance to make seismic experiments in a new place, just as he had done in the oceans, and he was sure he’d learn something new.

Why is learning about the Moon so important to us?

Landing humans on the Moon and bringing them back safely was a formidable technological challenge. And the time within which that was accomplished was incredibly short. The first human spaceflight was in 1961. Kennedy’s speech announcing that we would go to the Moon before the end of the decade was in 1961. Within only eight years we not only figured out how to send humans to the Moon and get them back, but we actually did it. That was the first time in human history that a person set foot on another planetary body. It’s something that will never happen again.

Apollo also provided our first detailed look at another planetary body. And it showed us how special the Earth-Moon system is. It was the Apollo 11 mission that demonstrated convincingly for the first time how ancient the Moon is — the samples brought back were more than 3 billion years old. We learned that the Moon recorded and illuminated a period of solar system history that we hadn’t begun to appreciate through our study of Earth. There’s no rock record on Earth for the first half billion years, but there is on the Moon. And because the Moon is our satellite, it’s part of our history, too. We learned how violent and chaotic the earliest history of the solar system was. We wouldn’t have gained that perspective without leaving Earth.

How do you think we were able to send humans to the moon so quickly?

As a nation, we put a big priority on meeting the goal that Kennedy set out. And throughout most of the 1960s we had Democratic presidents, Kennedy and Johnson, who were supportive of that program. In the 60s, the funding was there, and America’s reputation was at stake. There were military implications to the control of space. We were in the middle of the Cold War. There were many reasons we put the resources behind the Apollo program. NASA was a pretty daring agency at that time. They were willing to take risks. They didn’t want to risk more human lives than they needed to, but the astronauts were putting their lives on the line. The first astronauts were test pilots, who risked their lives every day over the course of their work; they knew what the risks were. NASA was a different agency back in the 60s than it has been since. Their engineers and managers set their sights high and did what they needed to do to meet schedules. And they had the resources to do it.

How have lunar missions changed from the time of Apollo 11 to present day?

When the Apollo program was underway we were sending two missions a year to different parts of the Moon. There was to have been an Apollo 18, an Apollo 19, and an Apollo 20, but these were expensive missions, and in 1972 the U.S. was spending a lot of money fighting the war in Vietnam. Those missions were cancelled, even though all of the hardware had been built and the astronauts that would fly those missions had been selected, and that decision ended the Apollo program. It was a challenge to devise experiments that could build on Apollo’s legacy and yet be done inexpensively with robotic spacecraft, which were being sent to many other targets — Mars, Venus, Mercury, Jupiter, Saturn, and, a few years later, Uranus and Neptune.

NASA did not return again to the Moon until the 1990s, with the Clementine orbiter — sponsored jointly with the Ballistic Missile Defense Organization — and the Lunar Prospector orbiter. Ten years ago, NASA launched the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, which is still operating at the Moon, and other missions have followed. Space organizations in other countries have also launched lunar missions, including the Soviet Union prior to and even after the Apollo missions, and later Japan, India, China, and Israel. In the U.S. and abroad, there are commercial entities that have their sights set on lunar landing. And earlier this year NASA announced plans to send the first woman and the next man to the Moon by 2024. If that goal is to be met, partnership with the commercial sector will be needed.

What do you hope the takeaway of the reignited interest surrounding the Moon landing will be?

I hope for two takeaway messages. First, the Apollo 11 mission was not only a remarkable technological achievement in the history of our species, but it also marked a “giant leap” in our appreciation of Earth’s place in our planetary system. And second, the Moon today still holds answers to important questions about the early history of our planet, and there remain myriad scientific as well as political and commercial reasons to return.

Related Posts

Army Veteran and Environmental Advocate: A Sustainability Science Student’s Journey to Columbia

In New Jersey’s Ancient Rocks, Hunting for Clues to an Earthquake in 2024

Columbia Beautiful Planet 2024

Celebrate over 50 years of Earth Day with us all month long! Visit our Earth Day website for ideas, resources, and inspiration.

Successful flights to the moon have such significance that their long-term influence and “impact” will not be well understood for many generations. Already it is so great it cannot be entirely described – it’s social, political, economic and so on. The phases of the Moon were depicted some 32,000 years ago. (The vast astrological cycle ) Consequences of the flights and Moon rocks will continue just about as long, 32,000 years. We no longer have an exaggerated military defense which would have protected us from “space aliens” from the Moon, Solar System or other star systems.

This is a great article very informative. But also at the same time doesn’t feel like reading a textbook or database. This article is straight forward but not boring great job guys.

but how did people landing on the moon change our world all together not just about one person, everyone

I need more information about group opinion not just one person

I’m not very smart but I believe that once the Apollo 11 went on the moon, it affected the whole world because there was suddenly a competition to accomplish further?

it was cool i was 7 at the time and i was watching tv with mom and dad. We used to live in Texas and we would non stop eat burgers.

that sounds very American

The article claims that it’s about how the Apollo 11 affected the world but then why isn’t it talking about that?

Thank you for the answers for my assignment

Thanks for this. This is exactly what I need for my monthly project.

Get the Columbia Climate School Newsletter →

- Institutional Repository Home

- Undergraduate Honors Research

- Undergraduate Honors Program - History Department

- Early North America and the United States

The Day the Earth Stood Still: The Apollo 11 Moon Landing and American Civil Religion

Files in this item.

This item appears in the following collection(s):

Your vanderbilt.

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

- International Students

- Parents & Family

- Prospective Students

- Researchers

- Sports Fans

- Visitors & Neighbors

Support the Jean and Alexander Heard Libraries

Gifts to the Libraries support the learning and research needs of the entire Vanderbilt community. Learn more about giving to the Libraries.

Quick Links

- Staff Directory

- Accessibility Services

- Vanderbilt Home

- Privacy Policy

How Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin Were Selected for the Apollo 11 Mission

Flight-obsessed since childhood, the Korean War veterans joined forces in one of the most successful space missions ever, the 1969 moon walk.

Two young men, both born in 1930, shared the same dream: To soar through the skies. The one from New Jersey joined the Air Force and the one from Ohio became a U.S. Navy pilot. Both fought in the Korean War. But it wasn’t until they were brought together that they ended up flying higher than they ever dreamed.

As Armstrong so lyrically captured, that momentous occasion was “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” But no giant leap happens without first finding their space legs.

Aldrin’s graduate school thesis helped him land a job at NASA

Born January 20, 1930, in Montclair, New Jersey, Edwin Eugene Aldrin Jr. (who legally changed his name to his nickname “Buzz,” which he got from his sister who used to pronounce “brother” as “buzzer”) looked up to his U.S. Air Force colonel father and headed to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, where he graduated third in his class in 1951.

Aldrin’s ambition of being a fighter pilot led him to the U.S. Air Force later that year — and he flew F-86 Sabre Jets in 66 combat missions during the Korean War as part of the 51st Fighter Wing. He received a Distinguished Flying Cross for his service.

Even so, he wasn’t done with flying and wanted to apply for test pilot school by earning a master’s degree at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). But his studies led him to a Ph.D. in aeronautics and astronautics.

His graduate school thesis focused on piloted spacecraft coming into close proximity, or “manned orbital rendezvous,” which attracted the attention of NASA while they were recruiting a team to pioneer space flight.

His specialization earned him the nickname “Dr. Rendezvous” and in 1966, he was assigned to the Gemini 12 crew, on which he walked in space for five hours — and took the first selfie in space. Although he was on the back-up crew for Apollo 8, it wasn’t until the Apollo 11 mission came along that all his training, along with his expertise for calculating rendezvous maneuvers, that he became the perfect fit as the lunar module pilot.

The NASA site says that Aldrin was “ideally qualified for this work, and his intellectual inclinations ensured that he carried out these tasks with enthusiasm.”

Armstong became a licensed student pilot at 16

Meanwhile, Armstrong, who was born August 5, 1930, in Wapakoneta, Ohio, on his grandparents’ farm quickly had his eyes on the skies. When he was just two years old, his dad took him to the National Air Races in Cleveland, Ohio, and the toddler became obsessed. By the time he was 15, he was taking flying lessons and became a licensed student pilot at 16 (before he got his driver’s license!).

He went on to study aeronautical engineering at Purdue University on a U.S. Navy scholarship and trained as a Navy pilot. Like Aldrin, he served in the Korean War, and Armstrong flew in 78 combat missions.

Soon he became part of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), an early rendition of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), working various roles, including as an engineer, test pilot and astronaut. When he was transferred to NASA’s Flight Research Center in the 1950s, he became a research pilot and flew more than 200 kinds of aircraft. During that time, he also received his master’s in aerospace engineering from the University of Southern California.

With both the practical training and the post-graduate education, he soon received astronaut status in 1962. In 1966, he was the command pilot of the Gemini VII mission, where he docked the vehicle to the orbiting Agena spacecraft. Despite the emergency landing in the Pacific Ocean, Armstrong’s piloting skills stood out and he was named spacecraft commander for the Apollo 11 .

The Apollo 11 astronauts “felt the weight of the world” upon them

Also on the Apollo 11 mission was Michael Collins , a fighter and test pilot with more than 4,200 hours of flying time before he joined NASA in 1963. He was a pilot on the Gemini X mission in 1966 and became the third U.S. spacewalker. That experience paved the way for him to become the command module pilot on Apollo 11, remaining in lunar orbit to ensure a safe return after Aldrin and Armstrong took their monumental steps.

With their combined flying experience and previous NASA flights, the trio was brought together as “amiable strangers” and put into an “almost frantic” six-month training program, as Collins described . “We were all business. We were all hard work, and we felt the weight of the world upon us.”

That dedication and focus made them the perfect team to successfully land on the moon on July 20, 1969, forever changing the course of how we view our universe.

Mae Jemison

Neil Armstrong

This Is the Crew of the Artemis II Mission

10 Black Pioneers in Aviation Who Broke Barriers

Biography: You Need to Know: Joseph M. Acaba

Ellen Ochoa

Valentina Tereshkova

Alan Shepard

James A. Lovell, Jr.

Michael Collins

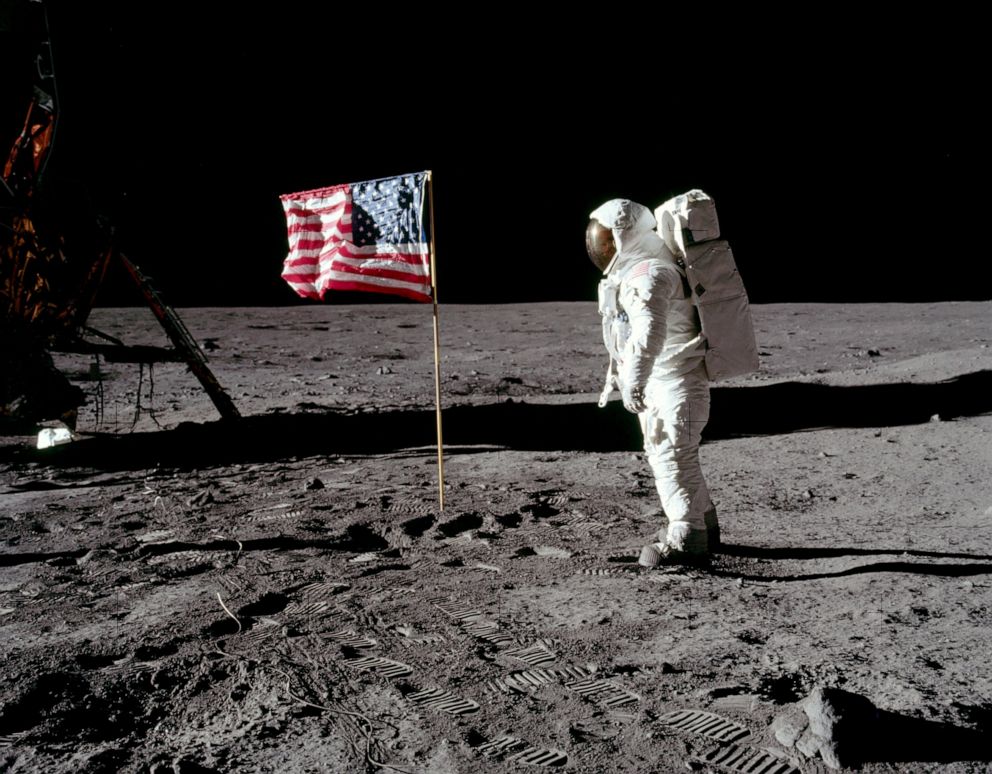

The pilot of the Apollo 11 lunar lander Eagle, Edwin "Buzz" Aldrin was one of the three Apollo 11 astronauts and the second person to set foot on the Moon.

One of the most reproduced NASA images, this photograph of an Apollo 11 astronaut on the Moon shows Buzz Aldrin. Neil Armstrong served as photographer—he can be seen reflected in Aldrin’s visor. Aldrin recalled Armstrong saying, “Stop and turn.” In this spontaneous picture, Aldrin’s arm is raised, perhaps to read the checklist sewn onto his left glove.

The image of Aldrin as Moonman became an iconic symbol of American accomplishment and was reproduced in books, films, television, and items of popular culture.

Custom Image Caption

Astronaut Buzz Aldrin poses for a photograph beside the deployed United States flag during an Apollo 11 Extravehicular Activity (EVA) on the lunar surface. The Lunar Module (LM) is on the left, and the footprints of the astronauts are clearly visible in the soil of the Moon. Astronaut Neil A. Armstrong, commander, took this picture with a 70mm Hasselblad lunar surface camera.

One of the first steps taken on the Moon, this is an image of Buzz Aldrin's bootprint from the Apollo 11 mission. Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin walked on the Moon on July 20, 1969.

Portrait of the prime crew of the Apollo 11 lunar landing mission. From left to right they are: Commander, Neil A. Armstrong, Command Module Pilot, Michael Collins, and Lunar Module Pilot, Buzz Aldrin.

This interior view of the Apollo 11 Lunar Module shows Buzz Aldrin, Jr., lunar module pilot, during the lunar landing mission. This picture was taken by Astronaut Neil Armstrong.

President Richard M. Nixon was in the central Pacific recovery area to welcome the Apollo 11 astronauts aboard the U.S.S. Hornet, prime recovery ship for the historic Apollo 11 lunar landing mission. Already confined to the Mobile Quarantine Facility (MQF) are (left to right) Neil Armstrong, commander; Michael Collins, command module pilot; and Buzz Aldrin, lunar module pilot. Apollo 11 splashed down at 11:49 a.m. (CDT), July 24, 1969, about 812 nautical miles southwest of Hawaii and only 12 nautical miles from the U.S.S. Hornet. The three crew men will remain in the MQF until they arrive at the Manned Spacecraft Center's (MSC) Lunar Receiving Laboratory (LRL). While astronauts Armstrong and Aldrin descended in the Lunar Module (LM) "Eagle" to explore the Sea of Tranquility region of the Moon, astronaut Collins remained with the Command and Service Modules (CSM) "Columbia" in lunar-orbit.

What was it like to be in the command module as the Apollo 11 mission blasted into space? To be one of the first humans to walk on the moon?

Buzz Aldrin, together with Michael Collins, shares his memories of making history.

Aldrin and Apollo 11 in the Collection

Originally, Aldrin was rejected from NASA because he was not a test pilot. However, the following year, applicants with over 1,000 hours of jet aircraft flying time were eligible, and with more than twice that time the former jet fighter pilot was more than qualified.

Aldrin was selected to join NASA's third group of astronauts in October 1963, after completing this graduate degree at MIT. He was the first astronaut with a doctoral degree.

In January 1963, six and a half years before the first Moon landing, Aldrin earned a degree of Doctor of Science from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), for his 311-page thesis “Line-of-Sight Guidance Techniques for Manned Orbital Rendezvous.” At the time he was a Major in the U.S. Air Force and had yet to be selected as an astronaut.

Apollo 11 was not Buzz Aldrin's first spaceflight. He previously traveled to space as part of Gemini XII, when Aldrin performed three EVAs (extravehicular activity, activity outside the spacecraft) including spending over five hours on a spacewalk.

More About Aldrin's Journey

- Get Involved

- Host an Event

Thank you. You have successfully signed up for our newsletter.

Error message, sorry, there was a problem. please ensure your details are valid and try again..

- Free Timed-Entry Passes Required

- Terms of Use

- Sustainability

Apollo 11: Six things we’ve learned since the 1969 lunar landing, and one enduring mystery

By David Ernst — Published on July 19, 2019

Fifty years ago on July 20, millions of Americans and people around the world gathered by their TV sets to witness Neil Armstrong becoming the first human to walk on the surface of the Moon.

In celebration of the anniversary of that historic moment and the Apollo 11 mission, Bates News reached out to Moon expert Noah Petro ’01 . Petro, whose research focuses on the evolution of the lunar crust, is the deputy project scientist for NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter mission.

Petro shared six pieces of information we’ve learned about our closest celestial neighbor since that fateful July day in 1969 — as well as one big lunar mystery we have yet to figure out.

1. The Moon is much older than we thought.

Pre-Apollo, scientists had proposed a variety of ages for the moon, from the hundreds of millions of years into the billions. The Apollo missions helped narrow the range.

“Apollo 11 samples were about 3 billion years old,” Petro says. “Later missions brought back rocks on the order of 4.55 billion years old, reflecting the age of the crust of the Moon.”

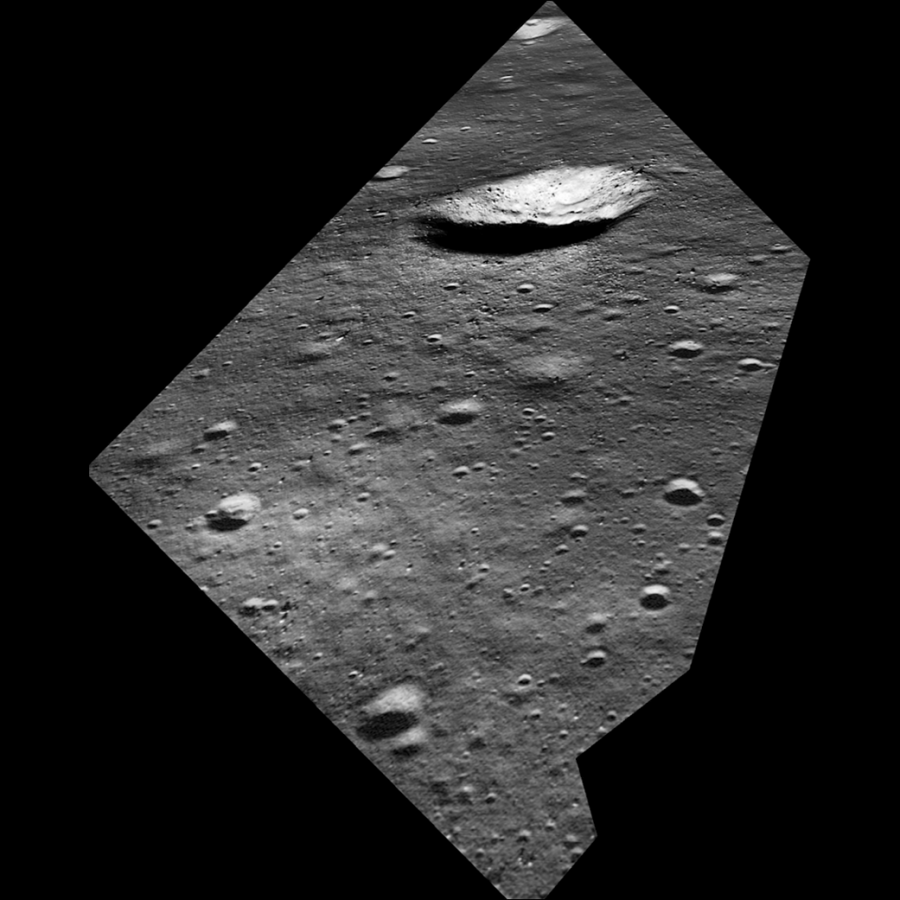

2. The moon’s famous craters come from asteroid impacts.

For decades before the 1969 landing, scientists debated what created the Moon’s many craters. Was it asteroids pounding the surface, or volcanic activity below?

Samples from the Apollo missions proved the former. The Moon doesn’t necessarily attract more asteroids than Earth, but because the Moon doesn’t have much of an atmosphere or processes like erosion, impacts leave conspicuous marks.

And Earth and the Moon have a similar history with asteroids.

“The Moon has pristine crater examples that help us interpret how those huge events shape and reshape planetary surfaces,” Petro says. “We know that early in Earth’s history, large impacts occurred with some frequency, based on the record we see on the Moon.”

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) simulated what Neil Armstrong saw in those final minutes as he guided the Lunar Module to the surface of the Moon. (NASA)

3. The Moon is seismically active.

”Apollo brought seismometers to the surface, allowing us to measure the activity of the Moon,” Petro says. “Apollo 11’s seismometer showed that impacts and moonquakes could actually shake the Moon.”

4. The Moon tells us about other planets.

Without plate tectonics, an atmosphere, and recent volcanoes to move things around, the crust of the Moon is much better preserved than that of Earth and some other planets. Studying the Moon’s essentially unaltered surface has helped scientists understand the rest of the solar system.

”When we look at the surface of a planet or asteroid or comet, we want to know how old it is,” Petro says. “Because we have samples from the Moon, and we know how old various surfaces of the Moon are, we can extrapolate that to other objects based on how many craters are on that surface, to estimate their ages.”

On the day of the 2017 solar eclipse, Noah Petro ’01 represented NASA at a minor league baseball game, the first that he knows of that included an “eclipse break.” (Photograph courtesy NASA/W. Hrybyk)

5. Pilots make good geologists.

The early astronauts, including the Moon-landers, were recruited from the ranks of military test pilots.

“We discovered former fighter pilots could be good field geologists,” Petro says. “All Apollo astronauts received geology training, which helped them collect an amazing suite of samples while on the surface.”

6. There is water in the Moon.

“Samples of volcanic glass were found in 2009 to have a small amount of water in them, changing our view of the Moon from a dry body to one that may have had water in it when it formed,” Petro says.

7. …but we still don’t know how the Moon formed.

“We think a large object struck the Earth early in its history, causing debris to circle the Earth that came together to form the Moon,” Petro says. But scientists don’t have definitive proof.

“We are now observing the formation of planets in other solar systems and using what we know of the Moon to understand how those planets may evolve.”

Officially a lunatic? Check out more of Petro’s work with the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter and its stunning images of later Apollo missions:

Related Content

Showing more content from "Art"

Bates in the News: August 3, 2018

August 3, 2018

In the eclipse’s path, these 10 Bates alumni are totally ready

August 18, 2017

Bates alumni in the eclipse’s path are totally ready for their moment without the sun

April 5, 2024

Recent News

Here are three recent news posts.

Those infamous 1800s pistol duels? They actually served a purpose

April 12, 2024

Picture Story: Celebrating students at Mount David Summit 2024

‘A really amazing thing’: The 2024 Senior Thesis Exhibition has arrived

Subscribe to bates news.

You’ll receive weekly emails with the latest news from Bates.

New subscriber? Please enter your name and e-mail address to receive updates from Bates College. Select the Updates you'd like to receive. You'll receive an e-mail confirmation within an hour.

Current subscriber? If you would like to change your subscriptions, open one of your Bates Update e-mails (BatesNews, Sports Update or Events at Bates) and click on "Change Subscriptions."

- Works & Talks

- Newsletter Sign Up

This essay was originally published in the September 1969 issue of The Objectivist and later anthologized in The Voice of Reason: Essays in Objectivist Thought (1989).

“No matter what discomforts and expenses you had to bear to come here,” said a NASA guide to a group of guests, at the conclusion of a tour of the Space Center on Cape Kennedy, on July 15, 1969, “there will be seven minutes tomorrow morning that will make you feel it was worth it.”

The tour had been arranged for the guests invited by NASA to attend the launching of Apollo 11. As far as I was able to find out, the guests — apart from government officials and foreign dignitaries — were mainly scientists, industrialists, and a few intellectuals who had been selected to represent the American people and culture on this occasion. If this was the standard of selection, I am happy and proud that I was one of these guests.

The NASA tour guide was a slight, stocky, middle-aged man who wore glasses and spoke — through a microphone, at the front of the bus — in the mild, gentle, patient manner of a schoolteacher. He reminded me of television’s Mr. Peepers — until he took off his glasses and I took a closer look at his face: he had unusual, intensely intelligent eyes.

The Space Center is an enormous place that looks like an untouched wilderness cut, incongruously, by a net of clean, new, paved roads: stretches of wild, subtropical growth, an eagle’s nest in a dead tree, an alligator in a stagnant moat — and, scattered at random, in the distance, a few vertical shafts rising from the jungle, slender structures of a shape peculiar to the technology of space, which do not belong to the age of the jungle or even fully to ours.

The discomfort was an inhuman, brain-melting heat. The sky was a sunless spread of glaring white, and the physical objects seemed to glare so that the mere sensation of sight became an effort. We kept plunging into an oven, when the bus stopped and we ran to modern, air-conditioned buildings that looked quietly unobtrusive and militarily efficient, then plunging back into the air-conditioned bus as into a pool. Our guide kept talking and explaining, patiently, courteously, conscientiously, but his heart was not in it, and neither was ours, even though the things he showed us would have been fascinating at any other time. The reason was not the heat; it was as if nothing could register on us, as if we were out of focus, or, rather, focused too intently and irresistibly on the event of the following day.

It was the guide who identified it, when he announced: “And now we’ll show you what you really want to see” — and we were driven to the site of Apollo 11.

The “VIP’s” tumbled out of the bus like tourists and rushed to photograph one another, with the giant rocket a few hundred yards away in the background. But some just stood and looked.

I felt a kind of awe, but it was a purely theoretical awe; I had to remind myself: “This is it,” in order to experience any emotion. Visually it was just another rocket, the kind you can see in any science-fiction movie or on any toy counter: a tall, slender shape of dead, powdery white against the white glare of the sky and the steel lacing of the service tower. There were sharp black lines encircling the white body at intervals — and our guide explained matter-of-factly that these marked the stages that would be burned off in tomorrow’s firings. This made the meaning of the rocket more real for an instant. But the fact that the lunar module, as he told us, was already installed inside the small, slanted part way on top of the rocket, just under the still smaller, barely visible spacecraft itself, would not become fully real; it seemed too small, too far away from us, and, simultaneously, too close: I could not quite integrate it with the parched stubble of grass under our feet, with its wholesomely usual touches of litter, with the psychedelic colors of the shirts on the tourists snapping pictures.

Tomorrow, our guide explained, we would be sitting on bleachers three miles away; he warned us that the sound of the blast would reach us some seconds later than the sight, and assured us that it would be loud, but not unbearable.

I do not know that guide’s actual work at the Space Center, and I do not know by what imperceptible signs he gave me the impression that he was a man in love with his work. It was only that concluding remark of his, later, at the end of the tour, that confirmed my impression. In a certain way, he set, for me, the tone of the entire occasion: the sense of what lay under the surface of the seemingly commonplace activities.

My husband and I were staying in Titusville, a tiny frontier settlement — the frontier of science — built and inhabited predominantly by the Space Center’s employees. It was just like any small town, perhaps a little newer and cleaner — except that ten miles away, across the bluish spread of the Indian River, one could see the foggy, bluish, rectangular shape of the Space Center’s largest structure, the Vehicle Assembly Building, and, a little farther away, two faint vertical shafts: Apollo 11 and its service tower. No matter what one looked at in that town, one could not really see anything else.

I noticed only that Titusville had many churches, too many, and that they had incredible, modernistic forms. Architecturally, they reminded me of the more extreme types of Hollywood drive-ins: a huge, cone-shaped roof, with practically no walls to support it — or an erratic conglomeration of triangles, like a coral bush gone wild — or a fairy-tale candy-house, with S-shaped windows dripping at random like gobs of frosting. I may be mistaken about this, but I had the impression that here, on the doorstep of the future, religion felt out of place and this was the way it was trying to be modern.

Since all the motels of Titusville were crowded beyond capacity, we had rented a room in a private home: as their contribution to the great event, many of the local homeowners had volunteered to help their chamber of commerce with the unprecedented flood of visitors. Our room was in the home of an engineer employed at the Space Center. It was a nice, gracious family, and one might have said a typical small-town family, except for one thing: a quality of cheerful openness, directness, almost innocence — the benevolent, unself-consciously self-confident quality of those who live in the clean, strict, reality-oriented atmosphere of science.

On the morning of July 16, we got up at 3 a.m. in order to reach the NASA Guest Center by 6 a.m., a distance that a car traveled normally in ten minutes. (Special buses were to pick up the guests at that Center, for the trip to the launching.) But Titusville was being engulfed by such a flood of cars that even the police traffic department could not predict whether one would be able to move through the streets that morning. We reached the Guest Center long before sunrise, thanks to the courtesy of our hostess, who drove us there through twisting back streets.

On the shore of the Indian River, we saw cars, trucks, trailers filling every foot of space on both sides of the drive, in the vacant lots, on the lawns, on the river’s sloping embankment. There were tents perched at the edge of the water; there were men and children sleeping on the roofs of station wagons, in the twisted positions of exhaustion; I saw a half-naked man asleep in a hammock strung between a car and a tree. These people had come from all over the country to watch the launching across the river, miles away. (We heard later that the same patient, cheerful human flood had spread through all the small communities around Cape Kennedy that night, and that it numbered one million persons.) I could not understand why these people would have such an intense desire to witness just a few brief moments; some hours later, I understood it.

It was still dark as we drove along the river. The sky and the water were a solid spread of dark blue that seemed soft, cold, and empty. But, framed by the motionless black leaves of the trees on the embankment, two things marked off the identity of the sky and the earth: far above in the sky, there was a single, large star; and on earth, far across the river, two enormous sheaves of white light stood shooting motionlessly into the empty darkness from two tiny upright shafts of crystal that looked like glowing icicles; they were Apollo 11 and its service tower.

It was dark when a caravan of buses set out at 7 A.M. on the journey to the Space Center. The light came slowly, beyond the steam-veiled windows, as we moved laboriously through back streets and back roads. No one asked any questions; there was a kind of tense solemnity about that journey, as if we were caught in the backwash of the enormous discipline of an enormous purpose and were now carried along on the power of an invisible authority.

It was full daylight — a broiling, dusty, hazy daylight — when we stepped out of the buses. The launch site looked big and empty like a desert; the bleachers, made of crude, dried planks, seemed small, precariously fragile and irrelevant, like a hasty footnote. Three miles away, the shaft of Apollo 11 looked a dusty white again, like a tired cigarette planted upright.

The worst part of the trip was that last hour and a quarter, which we spent sitting on wooden planks in the sun. There was a crowd of seven thousand people filling the stands, there was the cool, clear, courteous voice of a loudspeaker rasping into sound every few minutes, keeping us informed of the progress of the countdown (and announcing, somewhat dutifully, the arrival of some prominent government personage, which did not seem worth the effort of turning one’s head to see), but all of it seemed unreal. The full reality was only the vast empty space, above and below, and the tired white cigarette in the distance.

The sun was rolling up and straight at our faces, like a white ball wrapped in dirty cotton. But beyond the haze, the sky was clear — which meant that we would be able to see the whole of the launching, including the firing of the second and third stages.

Let me warn you that television does not give any idea of what we saw. Later, I saw that launching again on color television, and it did not resemble the original.

The loudspeaker began counting the minutes when there were only five left. When I heard: “Three-quarters of a minute,” I was up, standing on the wooden bench, and do not remember hearing the rest.

It began with a large patch of bright, yellow-orange flame shooting sideways from under the base of the rocket. It looked like a normal kind of flame and I felt an instant’s shock of anxiety, as if this were a building on fire. In the next instant the flame and the rocket were hidden by such a sweep of dark red fire that the anxiety vanished: this was not part of any normal experience and could not be integrated with anything. The dark red fire parted into two gigantic wings, as if a hydrant were shooting streams of fire outward and up, toward the zenith — and between the two wings, against a pitch-black sky, the rocket rose slowly, so slowly that it seemed to hang still in the air, a pale cylinder with a blinding oval of white light at the bottom, like an upturned candle with its flame directed at the earth. Then I became aware that this was happening in total silence, because I heard the cries of birds winging frantically away from the flames. The rocket was rising faster, slanting a little, its tense white flame leaving a long, thin spiral of bluish smoke behind it. It had risen into the open blue sky, and the dark red fire had turned into enormous billows of brown smoke, when the sound reached us: it was a long, violent crack, not a rolling sound, but specifically a cracking, grinding sound, as if space were breaking apart, but it seemed irrelevant and unimportant, because it was a sound from the past and the rocket was long since speeding safely out of its reach — though it was strange to realize that only a few seconds had passed. I found myself waving to the rocket involuntarily, I heard people applauding and joined them, grasping our common motive; it was impossible to watch passively, one had to express, by some physical action, a feeling that was not triumph, but more: the feeling that that white object’s unobstructed streak of motion was the only thing that mattered in the universe. The rocket was almost above our heads when a sudden flare of yellow-gold fire seemed to envelop it — I felt a stab of anxiety, the thought that something had gone wrong, then heard a burst of applause and realized that this was the firing of the second stage. When the loud, space-cracking sound reached us, the fire had turned into a small puff of white vapor floating away. At the firing of the third stage, the rocket was barely visible; it seemed to be shrinking and descending; there was a brief spark, a white puff of vapor, a distant crack — and when the white puff dissolved, the rocket was gone.

These were the seven minutes.

What did one feel afterward? An abnormal, tense overconcentration on the commonplace necessities of the immediate moment, such as stumbling over patches of rough gravel, running to find the appropriate guest bus. One had to overconcentrate, because one knew that one did not give a damn about anything, because one had no mind and no motivation left for any immediate action. How do you descend from a state of pure exaltation?

What we had seen, in naked essentials — but in reality, not in a work of art — was the concretized abstraction of man’s greatness.

The meaning of the sight lay in the fact that when those dark red wings of fire flared open, one knew that one was not looking at a normal occurrence, but at a cataclysm which, if unleashed by nature, would have wiped man out of existence — and one knew also that this cataclysm was planned, unleashed, and controlled by man, that this unimaginable power was ruled by his power and, obediently serving his purpose, was making way for a slender, rising craft. One knew that this spectacle was not the product of inanimate nature, like some aurora borealis, or of chance, or of luck, that it was unmistakably human — with “human,’’ for once, meaning grandeur — that a purpose and a long, sustained, disciplined effort had gone to achieve this series of moments, and that man was succeeding, succeeding, succeeding! For once, if only for seven minutes, the worst among those who saw it had to feel — not “How small is man by the side of the Grand Canyon!” — but “How great is man and how safe is nature when he conquers it!”

That we had seen a demonstration of man at his best, no one could doubt — this was the cause of the event’s attraction and of the stunned, numbed state in which it left us. And no one could doubt that we had seen an achievement of man in his capacity as a rational being — an achievement of reason, of logic, of mathematics, of total dedication to the absolutism of reality. How many people would connect these two facts, I do not know.

The next four days were a period torn out of the world’s usual context, like a breathing spell with a sweep of clean air piercing mankind’s lethargic suffocation. For thirty years or longer, the newspapers had featured nothing but disasters, catastrophes, betrayals, the shrinking stature of men, the sordid mess of a collapsing civilization; their voice had become a long, sustained whine, the megaphone of failure, like the sound of an oriental bazaar where leprous beggars, of spirit or matter, compete for attention by displaying their sores. Now, for once, the newspapers were announcing a human achievement, were reporting on a human triumph, were reminding us that man still exists and functions as man.

Those four days conveyed the sense that we were watching a magnificent work of art — a play dramatizing a single theme: the efficacy of man’s mind. One after another, the crucial, dangerous maneuvers of Apollo 11’s flight were carried out according to plan, with what appeared to be an effortless perfection. They reached us in the form of brief, rasping sounds relayed from space to Houston and from Houston to our television screens, sounds interspersed with computerized figures, translated for us by commentators who, for once, by contagion, lost their usual manner of snide equivocation and spoke with compelling clarity.

The most confirmed evader in the worldwide audience could not escape the fact that these sounds announced events taking place far beyond the earth’s atmosphere — that while he moaned about his loneliness and “alienation” and fear of entering an unknown cocktail party, three men were floating in a fragile capsule in the unknown darkness and loneliness of space, with earth and moon suspended like little tennis balls behind and ahead of them, and with their lives suspended on the microscopic threads connecting numbers on their computer panels in consequence of the invisible connections made well in advance by man’s brain — that the more effortless their performance appeared, the more it proclaimed the magnitude of the effort expended to project it and achieve it — that no feelings, wishes, urges, instincts, or lucky “conditioning,” either in these three men or in all those behind them, from highest thinker to lowliest laborer who touched a bolt of that spacecraft, could have achieved this incomparable feat — that we were watching the embodied concretization of a single faculty of man: his rationality.

There was an aura of triumph about the entire mission of Apollo 11, from the perfect launch to the climax. An assurance of success was growing in the wake of the rocket through the four days of its moon-bound flight. No, not because success was guaranteed — it is never guaranteed to man — but because a progression of evidence was displaying the precondition of success: these men know what they are doing.

No event in contemporary history was as thrilling, here on earth, as three moments of the mission’s climax: the moment when, superimposed over the image of a garishly colored imitation-module standing motionless on the television screen, there flashed the words: “Lunar module has landed” — the moment when the faint, gray shape of the actual module came shivering from the moon to the screen — and the moment when the shining white blob which was Neil Armstrong took his immortal first step. At this last, I felt one instant of unhappy fear, wondering what he would say, because he had it in his power to destroy the meaning and the glory of that moment, as the astronauts of Apollo 8 had done in their time. He did not. He made no reference to God; he did not undercut the rationality of his achievement by paying tribute to the forces of its opposite; he spoke of man. “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” So it was.

As to my personal reaction to the entire mission of Apollo 11, I can express it best by paraphrasing a passage from Atlas Shrugged that kept coming back to my mind: “Why did I feel that joyous sense of confidence while watching the mission? In all of its giant course, two aspects pertaining to the inhuman were radiantly absent: the causeless and the purposeless. Every part of the mission was an embodied answer to ‘Why?’ and ‘What for?’ — like the steps of a life-course chosen by the sort of mind I worship. The mission was a moral code enacted in space.”

Now, coming back to earth (as it is at present), I want to answer briefly some questions that will arise in this context. Is it proper for the government to engage in space projects? No, it is not — except insofar as space projects involve military aspects, in which case, and to that extent, it is not merely proper but mandatory. Scientific research as such, however, is not the proper province of the government.

But this is a political issue; it pertains to the money behind the lunar mission or to the method of obtaining that money, and to the project’s administration; it does not affect the nature of the mission as such, it does not alter the fact that this was a superlative technological achievement.

In judging the effectiveness of the various elements involved in any large-scale undertaking of a mixed economy, one must be guided by the question: which elements were the result of coercion and which the result of freedom? It is not coercion, not the physical force or threat of a gun, that created Apollo 11. The scientists, the technologists, the engineers, the astronauts were free men acting of their own choice. The various parts of the spacecraft were produced by private industrial concerns. Of all human activities, science is the field least amenable to force: the facts of reality do not take orders. (This is one of the reasons why science perishes under dictatorships, though technology may survive for a short while.)

It is said that without the “unlimited” resources of the government, such an enormous project would not have been undertaken. No, it would not have been — at this time . But it would have been, when the economy was ready for it. There is a precedent for this situation. The first transcontinental railroad of the United States was built by order of the government, on government subsidies. It was hailed as a great achievement (which, in some respects, it was). But it caused economic dislocations and political evils, for the consequences of which we are paying to this day in many forms.

If the government deserves any credit for the space program, it is only to the extent that it did not act as a government, i.e., did not use coercion in regard to its participants (which it used in regard to its backers, i.e., the taxpayers). And what is relevant in this context (but is not to be taken as a justification or endorsement of a mixed economy) is the fact that of all our government programs, the space program is the cleanest and best: it, at least, has brought the American citizens a return on their forced investment, it has worked for its money, it has earned its keep, which cannot be said about any other program of the government.

There is, however, a shameful element in the ideological motivation (or the publicly alleged motivation) that gave birth to our space program: John F. Kennedy’s notion of a space competition between the United States and Soviet Russia.

A competition presupposes some basic principles held in common by all the competitors, such as the rules of the game in athletics, or the functions of the free market in business. The notion of a competition between the United States and Soviet Russia in any field whatsoever is obscene: they are incommensurable entities, intellectually and morally. What would you think of a competition between a doctor and a murderer to determine who could affect the greatest number of people? Or: a competition between Thomas A. Edison and Al Capone to see who could get rich quicker?

The fundamental significance of Apollo 11’s triumph is not political; it is philosophical; specifically, moral-epistemological.

The lunar landing as such was not a milestone of science, but of technology. Technology is an applied science, i.e., it translates the discoveries of theoretical science into practical application to man’s life. As such, technology is not the first step in the development of a given body of knowledge, but the last; it is not the most difficult step, but it is the ultimate step, the implicit purpose, of man’s quest for knowledge.

The lunar landing was not the greatest achievement of science, but its greatest visible result. The greatest achievements of science are invisible: they take place in a man’s mind; they occur in the form of a connection integrating a broad range of phenomena. The astronaut of an earlier mission who remarked that his spacecraft was driven by Sir Isaac Newton understood this issue. (And if I may be permitted to amend that remark, I would say that Sir Isaac Newton was the copilot of the flight; the pilot was Aristotle.) In this sense, the lunar landing was a first step, a beginning, in regard to the moon, but it was a last step, an end product, in regard to the earth — the end product of a long, intellectual-scientific development.

This does not diminish in any way the intellectual stature, power, or achievement of the technologists and the astronauts; it merely indicates that they were the worthy recipients of an illustrious heritage, who made full use of it by the exercise of their own individual ability. (The fact that man is the only species capable of transmitting knowledge and thus capable of progress, the fact that man can achieve a division of labor, and the fact that large numbers of men are required for a large-scale undertaking, do not mean what some creeps are suggesting: that achievement has become collective.)

I am not implying that all the men who contributed to the flight of Apollo 11 were necessarily rational in every aspect of their lives or convictions. But in their various professional capacities — each to the extent that he did contribute to the mission — they had to act on the principle of strict rationality.

The most inspiring aspect of Apollo 11’s flight was that it made such abstractions as rationality, knowledge, science perceivable in direct, immediate experience. That it involved a landing on another celestial body was like a dramatist’s emphasis on the dimensions of reason’s power: it is not of enormous importance to most people that man lands on the moon, but that man can do it, is.

This was the cause of the world’s response to the flight of Apollo 11.

Frustration is the leitmotif in the lives of most men, particularly today — the frustration of inarticulate desires, with no knowledge of the means to achieve them. In the sight and hearing of a crumbling world, Apollo 11 enacted the story of an audacious purpose, its execution, its triumph, and the means that achieved it — the story and the demonstration of man’s highest potential. Whatever his particular ability or goal, if a man is not to give up his struggle, he needs the reminder that success is possible; if he is not to regard the human species with fear, contempt, or hatred, he needs the spiritual fuel of knowing that man the hero is possible.

This was the meaning and the unidentified motive of the millions of eager, smiling faces that looked up to the flight of Apollo 11 from all over the remnants and ruins of the civilized world. This was the meaning that people sensed, but did not know in conscious terms — and will give up or betray tomorrow. It was the job of their teachers, the intellectuals, to tell them. But it is not what they are being told.

A great event is like an explosion that blasts off pretenses and brings the hidden out to the surface, be it diamonds or muck. The flight of Apollo 11 was “a moment of truth”: it revealed an abyss between the physical sciences and the humanities that has to be measured in terms of interplanetary distances. If the achievements of the physical sciences have to be watched through a telescope, the state of the humanities requires a microscope: there is no historical precedent for the smallness of stature and shabbiness of mind displayed by today’s intellectuals.

In The New York Times of July 21, 1969, there appeared two whole pages devoted to an assortment of reactions to the lunar landing, from all kinds of prominent and semi-prominent people who represent a cross-section of our culture.

It was astonishing to see how many ways people could find to utter variants of the same bromides. Under an overwhelming air of staleness, of pettiness, of musty meanness, the collection revealed the naked essence (and spiritual consequences) of the basic premises ruling today’s culture: irrationalism — altruism — collectivism.

The extent of the hatred for reason was somewhat startling. (And, psychologically, it gave the show away: one does not hate that which one honestly regards as ineffectual.) It was, however, expressed indirectly, in the form of denunciations of technology. (And since technology is the means of bringing the benefits of science to man’s life, judge for yourself the motive and the sincerity of the protestations of concern with human suffering.)

“But the chief reason for assessing the significance of the moon landing negatively, even while the paeans of triumph are sung, is that this tremendous technical achievement represents a defective sense of human values, and of a sense of priorities of our technical culture.” “We are betraying our moral weakness in our very triumphs in technology and economics.” “How can this nation swell and stagger with technological pride when it is so weak, so wicked, so blinded and misdirected in its priorities? While we can send men to the moon or deadly missiles to Moscow or toward Mao, we can’t get foodstuffs across town to starving folks in the teeming ghettos.” “Are things more important than people? I simply do not believe that a program comparable to the moon landing cannot be projected around poverty, the war, crime, and so on.” “If we show the same determination and willingness to commit our resources, we can master the problems of our cities just as we have mastered the challenge of space.” “In this regard, the contemporary triumphs of man’s mind — his ability to translate his dreams of grandeur into awesome accomplishments — are not to be equated with progress, as defined in terms of man’s primary concern with the welfare of the masses of fellow human beings . . . the power of human intelligence which was mobilized to accomplish this feat can also be mobilized to address itself to the ultimate acts of human compassion.” “But, the most wondrous event would be if man could relinquish all the stains and defilements of the untamed mind . . .”

There was one entirely consistent person in that collection, Pablo Picasso, whose statement, in full, was: “It means nothing to me. I have no opinion about it, and I don’t care.” His work has been demonstrating that for years.

The best statement was, surprisingly, that of the playwright Eugene Ionesco, who was perceptive about the nature of his fellow intellectuals. He said, in part:

It’s an extraordinary event of incalculable importance. The sign that it’s so important is that most people aren’t interested in it. They go on discussing riots and strikes and sentimental affairs. The perspectives opened up are enormous, and the absence of interest shows an astonishing lack of goodwill. I have the impression that writers and intellectuals — men of the left — are turning their backs to the event.

This is an honest statement — and the only pathetic (or terrible) thing about it is the fact that the speaker has not observed that “men of the left” are not “most people.”

Now consider the exact, specific meaning of the evil revealed in that collection: it is the moral significance of Apollo 11 that is being ignored; it is the moral stature of the astronauts — and of all the men behind them, and of all achievement — that is being denied. Think of what was required to achieve that mission: think of the unself-pitying effort; the merciless discipline; the courage; the responsibility of relying on one’s judgment; the days, nights and years of unswerving dedication to a goal; the tension of the unbroken maintenance of a full, clear mental focus; and the honesty (honesty means: loyalty to truth, and truth means: the recognition of reality). All these are not regarded as virtues by the altruists and are treated as of no moral significance.

Now perhaps you will grasp the infamous inversion represented by the morality of altruism.

Some people accused me of exaggeration when I said that altruism does not mean mere kindness or generosity, but the sacrifice of the best among men to the worst, the sacrifice of virtues to flaws, of ability to incompetence, of progress to stagnation — and the subordinating of all life and of all values to the claims of anyone’s suffering.

You have seen it enacted in reality.

What else is the meaning of the brazen presumption of those who protest against the mission of Apollo 11, demanding that the money (which is not theirs) be spent, instead, on the relief of poverty?

This is not an old-fashioned protest against mythical tycoons who “exploit” their workers, it is not a protest against the rich, it is not a protest against idle luxury, it is not a plea for some marginal charity, for money that “no one would miss.” It is a protest against science and progress, it is the impertinent demand that man’s mind cease to function, that man’s ability be denied the means to move forward, that achievement stop — because the poor hold a first mortgage on the lives of their betters.

By their own assessment, by demanding that the public support them, these protesters declare that they have not produced enough to support themselves — yet they present a claim on the men whose ability produced so enormous a result as Apollo 11, declaring that it was done at their expense, that the money behind it was taken from them . Led by their spiritual equivalents and spokesmen, they assert a private right to public funds, while denying the public (i.e., the rest of us) the right to any higher, better purpose.

I could remind them that without the technology they damn, there would be no means to support them. I could remind them of the pretechnological centuries when men subsisted in such poverty that they were unable to feed themselves, let alone give assistance to others. I could say that anyone who used one-hundredth of the mental effort used by the smallest of the technicians responsible for Apollo 11 would not be consigned to permanent poverty, not in a free or even semi-free society. I could say it, but I won’t. It is not their practice that I challenge, but their moral premise. Poverty is not a mortgage on the labor of others — misfortune is not a mortgage on achievement — failure is not a mortgage on success — suffering is not a claim check, and its relief is not the goal of existence — man is not a sacrificial animal on anyone’s altar or for anyone’s cause — life is not one huge hospital.

Those who suggest that we substitute a war on poverty for the space program should ask themselves whether the premises and values that form the character of an astronaut would be satisfied by a lifetime of carrying bedpans and teaching the alphabet to the mentally retarded. The answer applies as well to the values and premises of the astronauts’ admirers. Slums are not a substitute for stars.

The question we are constantly hearing today is: why are men able to reach the moon, but unable to solve their social-political problems? This question involves the abyss between the physical sciences and the humanities. The flight of Apollo 11 has made the answer obvious: because, in regard to their social problems, men reject and evade the means that made the lunar landing possible, the only means of solving any problem — reason.

In the field of technology, men cannot permit themselves the kind of mental processes that have been demonstrated by some of the reactions to Apollo 11. In technology, there are no gross irrationalities such as the conclusion that since mankind was united by its enthusiasm for the flight, it can be united by anything (as if the ability to unite were a primary, regardless of purpose or cause). There are, in technology, no evasions of such magnitude as the present chorus of slogans to the effect that Apollo 11’s mission should somehow lead men to peace, goodwill, and the realization that mankind is one big family. What family? With one-third of mankind enslaved under an unspeakable rule of brute force, are we to accept the rulers as members of the family, make terms with them, and sanction the terrible fate of the victims? If so, why are the victims to be expelled from the one big human family? The speakers have no answer. But their implicit answer is: We could make it work somehow, if we wanted to!

In technology, men know that all the wishes and prayers in the world will not change the nature of a grain of sand.

It would not have occurred to the builders of the spacecraft to select its materials without the most minute, exhaustive study of their characteristics and properties. But, in the humanities, every sort of scheme or project is proposed and carried out without a moment’s thought or study of the nature of man. No instrument was installed aboard the spacecraft without a thorough knowledge of the conditions its functions required. All kinds of impossible, contradictory demands are imposed on man in the humanities with no concern for the conditions of existence he requires. No one tore apart the circuits of the spacecraft’s electric system and declared: “It will do the job if it wants to!” This is the standard policy in regard to man. No one chose a type of fuel for Apollo 11 because he “felt like it,” or ignored the results of a test because he “didn’t feel like it,” or programmed a computer with a jumble of random, irrelevant nonsense he “didn’t know why.” These are the standard procedures and criteria accepted in the humanities. No one made a decision affecting the spacecraft by hunch, by whim, or by sudden, inexplicable “intuition.” In the humanities, these methods are regarded as superior to reason. No one proposed a new design for the spacecraft, worked out in every detail, except that it had no provision for rockets or for any means of propulsion. It is the standard practice in the humanities to devise and design social systems controlling every aspect of man’s life, except that no provision is made for the fact that man possesses a mind and that his mind is his means of survival. No one suggested that the flight of Apollo 11 be planned according to the rules of astrology, and its course be charted by the rules of numerology. In the humanities, man’s nature is interpreted according to Freud, and his social course is prescribed by Marx.

But — the practitioners of the humanities protest — we cannot treat man as an inanimate object. The truth of the matter is that they treat man as less than an inanimate object, with less concern, less respect for his nature. If they gave to man’s nature a small fraction of the meticulous, rational study that the scientists are now giving to lunar dust, we would be living in a better world. No, the specific procedures for studying man are not the same as for studying inanimate objects — but the epistemological principles are.

Nothing on earth or beyond it is closed to the power of man’s reason. Yes, reason could solve human problems — but nothing else on earth or beyond it can.

This is the fundamental lesson to be learned from the triumph of Apollo 11. Let us hope that some men will learn it. But it will not be learned by most of today’s intellectuals, since the core and motor of all their incredible constructs is the attempt to establish human tyranny as an escape from what they call “the tyranny” of reason and reality.

If the lesson is learned in time, the flight of Apollo 11 will be the first achievement of a great new age; if not, it will be a glorious last — not forever, but for a long, long time to come.

I want to mention one small incident, an indication of why achievement perishes under altruist-collectivist rule. One of the ugliest aspects of altruism is that it penalizes the good for being the good, and success for being success. We have seen that, too, enacted in reality.

It is obvious that one of the reasons motivating the NASA administrators to achieve a lunar landing was the desire to demonstrate the value of the space program and receive financial appropriations to continue the program’s work. This was fully rational and proper for the managers of a government project: there is no honest way of obtaining public funds except by impressing the public with a project’s actual results. But such a motive involves an old-fashioned kind of innocence; it comes from an implicit free-enterprise context, from the premise that rewards are to be earned by achievement, and that achievement is to be rewarded. Apparently, they had not grasped the modern notion, the basic premise of the welfare state: that rewards are divorced from achievement, that one obtains money from the government by giving nothing in return, and the more one gets, the more one should demand.

The response of Congress to Apollo 11 included some prominent voices who declared that NASA’s appropriations should be cut because the lunar mission has succeeded.(!) The purpose of the years of scientific work is completed, they said, and “national priorities” demand that we now pour more money down the sewers of the war on poverty.

If you want to know the process that embitters, corrupts, and destroys the managers of government projects, you are seeing it in action. I hope that the NASA administrators will be able to withstand it.

As far as “national priorities” are concerned, I want to say the following: we do not have to have a mixed economy, we still have a chance to change our course and thus to survive. But if we do continue down the road of a mixed economy, then let them pour all the millions and billions they can into the space program. If the United States is to commit suicide, let it not be for the sake and support of the worst human elements, the parasites-on-principle, at home and abroad. Let it not be its only epitaph that it died paying its enemies for its own destruction. Let some of its lifeblood go to the support of achievement and the progress of science. The American flag on the moon — or on Mars, or on Jupiter — will, at least, be a worthy monument to what had once been a great country.

About the Author

Related Materials

Buy The Book: The Voice of Reason: Essays in Objectivist Thought

Read: Apollo and Dionysus

What Is Man? Philosophy and Human Nature

Ayn Rand: A Writer’s Life

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Ayn Rand Global

- Ayn Rand Institute eStore

- Ayn Rand University app

Updates From ARI

Copyright © 1985 – 2024 The Ayn Rand Institute (ARI). Reproduction of content and images in whole or in part is prohibited. All rights reserved. ARI is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. Contributions to ARI in the United States are tax-exempt to the extent provided by law. Objectivist Conferences (OCON), Ayn Rand Conference (ARC), Ayn Rand University (ARU) and the Ayn Rand Institute eStore are operated by ARI. Payments to OCON, ARC, ARU or the Ayn Rand Institute eStore do not qualify as tax-deductible contributions to the Ayn Rand Institute. AYN RAND, AYN RAND INSTITUTE, ARI, AYN RAND UNIVERSITY and the AYN RAND device are trademarks of the Ayn Rand Institute. All rights reserved.

Search this site

Around the o menu.

Around the O

50 years later, apollo 11 remains an inspiration for uo researchers.

Shortly after noon on July 20, 1969, the world watched as Neil Armstrong became the first person to set foot on the moon.

The impact of that moment continues to ripple though society and capture the imagination of many. For these University of Oregon faculty members — an astronomer, a product designer and a linguist — the moon landing was a source of inspiration and the basis of research, and it still resonates in their fields to this day.

Scott Fisher , a stronomy lecturer, outreach coordinator and director of the Pine Mountain Observatory :

Q: How did the moon landing affect your field?

A: Astronomers now are still reaping the benefits of Apollo. The generation of my thesis advisors were the kids that were inspired by Apollo. These were the engineers, the technical scientists and the people who wanted to build incredible machines; those are the folks who watched Apollo live. They were in their teens when the program happened.

I know for a fact that Apollo and 1960s-era NASA was a major inspiration for many of the instrument builders and technical staff that I worked with at large telescope facilities before my time at the UO. While Apollo was not directly related to astronomy —other than perhaps some stellar navigation during the crisis of Apollo 13 — it was this oblique support that we’re reaping the benefits of now.

Q: What does it mean to you now?

A: I think I caught the tail-end of the Apollo excitement, but I know now that I would have been, dare I even say, over the moon if I were 10 years older and were in that slightly older generation. I would have been hooked. I can tell because I still am hooked.

As an astronomer, I’m a little bit unusual in that I have a strong engineering slant. I freely admit that I love the machines of science. To me, I enjoy learning about the telescopes , and particularly the technology of the cameras and instruments that are used on them to obtain data, because in my mind I can draw a direct path from the camera that I helped build in grad school to someone who was inspired by Apollo.

Q: Is that the coolest part for you?

A: As an astronomer, it’s pretty cool to still look up the moon and think people walked on that. For me, personally, it’s the technology. I’m just immensely fascinated by the technology, the incredible strides in engineering and technology those folks made with what we would call extremely basic computers. I still find it almost unbelievable that many of the most critical calculations made for Apollo were made by a human .

And think that your phone has more memory in it than every Apollo spaceship that ever flew. I think we should all take a moment and respect what they did with what we would consider such limited technology. But you know what? It worked. That is a fascinating thing.

We all look up, we all appreciate the moon. I see the same moon as somebody in Australia sees — it’s upside down there — and space is the shared experience. I think we can use that in a positive way. Let’s parlay that fascination into something we can all get behind. I think Apollo was a worldwide catalyst that let us, humanity, do just that.

Susan Sokolowski , d irector of the Sports Product Design Program who earlier wrote about the all-female spacewalk that was canceled because of a lack of properly sized spacesuits:

Q: With no female astronauts in 1969, how far has product design come for the U.S. space program since then in terms of incorporating females?

A: There were actually 19 women in the U.S. that trained to be astronauts in the 1960s. They were part of the Women in Space Program . The women completed the same required physiological tests as their male astronaut counterparts. Thirteen of the women passed the requirements, and some even outperformed the men. The program, however, was shut down around 1962.

The space agency did not select any (new) female astronaut candidates until 1978. Sally Ride became the first American woman in space, in 1983. In-flight, she wore identically designed products to her fellow male astronauts . During Apollo days, suits were customized to each astronaut. Today, they are modular, and the parts are put together for each astronaut to create a “portable environment.” In the 1990s, due to budget cuts, some of the smaller-sized parts were discontinued, which makes it more difficult to outfit women properly.

Q: What does it say when the all-female spacewalk canceled because of the lack of sufficient female-specific spacesuits?

A: It says financially and strategically, that NASA is not keen about outfitting a wide variety of body shapes and sizes in space, and that they would rather outfit the “average man.” It also says that there is not an ecosystem in place for R&D teams to have a voice, to relook at the sizing systems for spacesuits. Although women were highlighted in the recent incident, the lack of sizes could also affect men, as the astronauts are more and more ethnically diverse.

Q: What do you think is the coolest thing about landing someone on the moon?

A: There are so many dangers and hazards that astronauts can face. I find it incredibly inspiring that a team of people can rally around an effort that seems impossible and make it successfully happen.

Melissa Baese-Berk , a linguist who has used advanced research techniques to better determine exactly what Neil Armstrong said when he became the first human to set foot on the moon:

Q: What’s the reaction to your research around Neil Armstrong’s famous quote ?

A: It’s been fun to work on because it captures people’s imagination in a way that typical research doesn’t always do. I think one reason why is we’re really, really good at understanding and producing speech, so most of the time, we don’t have misunderstandings, especially in cases where something is highly scripted or highly public.

This quote being so famous and also being a quote that is possibly misunderstood, I think really captures people’s imagination. The fact that there might be an explanation for why he was misunderstood or why he misspoke, depending on your perspective on this, I think both of those things are interesting to people because, from a layman’s perspective, that’s not something you think about happening all that often, misunderstanding or misspeaking.

Q: What prompted you to research the quote?

A: People have tried to look at this quote in a lot of detail, but it was recorded under really not ideal circumstances — 50 years ago from the moon — so it’s not like it’s the best recording quality we’ve ever seen.

The challenge there is you can fight all day back and forth about whether or not he said this. I don’t think we’re going to get a definitive answer from that.

What I like about our study is instead of saying is the “a” there, we took two tacks: which is to say, is it plausible that his utterance could be compatible with both “for” and “for a,” or is it only consistent with one or the other? The other question is: do people misunderstand instances like this, with acoustics that are similar to this? If the answer to both questions is yes, then we come down on a slightly more conclusive answer.

— By Jim Murez, University Communications

Submit Your Story Idea

Subscribe to Around the O

Why the Apollo 11 moon landing conspiracy theories have endured despite being debunked numerous times

Some reportedly believe Stanley Kubrick filmed the landing at Area 51.

Sure, you could believe what people tell you.

Or you could believe that the moon landing was all a stunt pulled off by famous director Stanley Kubrick, who created technology that helped it look like man was pioneering space, according to some conspiracy theorists, who said it was really filmed in Area 51 in Nevada .