- Switch language

- Português do Brasil

The Impact of COVID-19 on Education Experiences of High School Students in Semi-Rural Georgia Open Access

Ashta, jasleen (spring 2021).

Background: The COVID-19 pandemic led to the closure of schools and transition to online learning across the country. High school students, especially those belonging to populations most heavily impacted by the virus, experienced many obstacles and challenges to their education. This study examines the consequences of the pandemic on high school students shortly after the closure of public school buildings, and how these impacts vary by race/ethnicity, gender, grade level, socioeconomic status, and academic performance prior to the pandemic.

Methods: Racial/ethnically and socioeconomically diverse students (n=666) from two high schools in semi-rural Georgia completed a cross-sectional, one-time online survey. Survey results were linked to education and demographic data provided by the school district.

Results: While students largely felt supported by their teachers and school staff and 43% of students believed that they could excel academically during the coronavirus pandemic, approximately 60% expressed academic worry and obstacles to virtual learning, such as unclear expectations from teachers and social isolation. Differences by race/ethnicity, gender, grade level, and socioeconomic status were observed. Hispanic students expressed significantly more academic worry and less confidence in the transition than their peers, while Black students reported less worry despite significantly more technological obstacles than their peers. While female students expressed high satisfaction with school responsiveness and support, they also indicated significantly more academic worry and requested more additional resources than male students. Grade 12 students reported significantly higher levels of academic and career worry than students in lower grade levels. Students eligible for free and reduced lunch expressed significantly more worry and obstacles with online learning than their peers. Non-honors students and low attendance students had 1.6 times higher odds of being worried about grades and graduation compared to honors students and students with regular attendance.

Conclusion: High school students experience differential effects and concerns of the pandemic on their education and career trajectories. COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on the education system has the potential to increase the existing academic achievement gap in the United States. Proactive measures to recover from academic loss in the pandemic must be taken to ensure the healthy development of our youth.

Table of Contents

I. Introduction....................................................................................1

A. Research Questions………………………………………………………………..6

II. Methods………………………………………………………………………………8

A. Study Design…………………………………………………..…………………....8

B. Study Population……………………………………………………….……….….8

C. Data Sources………………………………………………………………...….…..8

D. Data Measures…………………………………………………………..……….…9

E. Analyses……………………………………………………………….………....…13

III. Results…………………………………………………………………………...….16

IV. Discussion…………………………………………………………………………..24

A. Strengths and Limitations………………………………………………….…..28

B. Future Directions……………………………………………………...……….…29

C. Implications………………………………………………………………...……..30

V. References…………………………………………………………………………..32

VI. Tables………………………………………………………………………………..37

About this Master's Thesis

Primary PDF

Supplemental files.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Roadmap to Gaza peace may run through Oslo

Why Democrats, Republicans, who appear at war these days, really need each other

Decline of golden age for American Jews

Rubén Rodriguez/Unsplash

Time to fix American education with race-for-space resolve

Harvard Staff Writer

Paul Reville says COVID-19 school closures have turned a spotlight on inequities and other shortcomings

This is part of our Coronavirus Update series in which Harvard specialists in epidemiology, infectious disease, economics, politics, and other disciplines offer insights into what the latest developments in the COVID-19 outbreak may bring.

As former secretary of education for Massachusetts, Paul Reville is keenly aware of the financial and resource disparities between districts, schools, and individual students. The school closings due to coronavirus concerns have turned a spotlight on those problems and how they contribute to educational and income inequality in the nation. The Gazette talked to Reville, the Francis Keppel Professor of Practice of Educational Policy and Administration at Harvard Graduate School of Education , about the effects of the pandemic on schools and how the experience may inspire an overhaul of the American education system.

Paul Reville

GAZETTE: Schools around the country have closed due to the coronavirus pandemic. Do these massive school closures have any precedent in the history of the United States?

REVILLE: We’ve certainly had school closures in particular jurisdictions after a natural disaster, like in New Orleans after the hurricane. But on this scale? No, certainly not in my lifetime. There were substantial closings in many places during the 1918 Spanish Flu, some as long as four months, but not as widespread as those we’re seeing today. We’re in uncharted territory.

GAZETTE: What lessons did school districts around the country learn from school closures in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, and other similar school closings?

REVILLE: I think the lessons we’ve learned are that it’s good [for school districts] to have a backup system, if they can afford it. I was talking recently with folks in a district in New Hampshire where, because of all the snow days they have in the wintertime, they had already developed a backup online learning system. That made the transition, in this period of school closure, a relatively easy one for them to undertake. They moved seamlessly to online instruction.

Most of our big systems don’t have this sort of backup. Now, however, we’re not only going to have to construct a backup to get through this crisis, but we’re going to have to develop new, permanent systems, redesigned to meet the needs which have been so glaringly exposed in this crisis. For example, we have always had large gaps in students’ learning opportunities after school, weekends, and in the summer. Disadvantaged students suffer the consequences of those gaps more than affluent children, who typically have lots of opportunities to fill in those gaps. I’m hoping that we can learn some things through this crisis about online delivery of not only instruction, but an array of opportunities for learning and support. In this way, we can make the most of the crisis to help redesign better systems of education and child development.

GAZETTE: Is that one of the silver linings of this public health crisis?

REVILLE: In politics we say, “Never lose the opportunity of a crisis.” And in this situation, we don’t simply want to frantically struggle to restore the status quo because the status quo wasn’t operating at an effective level and certainly wasn’t serving all of our children fairly. There are things we can learn in the messiness of adapting through this crisis, which has revealed profound disparities in children’s access to support and opportunities. We should be asking: How do we make our school, education, and child-development systems more individually responsive to the needs of our students? Why not construct a system that meets children where they are and gives them what they need inside and outside of school in order to be successful? Let’s take this opportunity to end the “one size fits all” factory model of education.

GAZETTE: How seriously are students going to be set back by not having formal instruction for at least two months, if not more?

“The best that can come of this is a new paradigm shift in terms of the way in which we look at education, because children’s well-being and success depend on more than just schooling,” Paul Reville said of the current situation. “We need to look holistically, at the entirety of children’s lives.”

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

REVILLE: The first thing to consider is that it’s going to be a variable effect. We tend to regard our school systems uniformly, but actually schools are widely different in their operations and impact on children, just as our students themselves are very different from one another. Children come from very different backgrounds and have very different resources, opportunities, and support outside of school. Now that their entire learning lives, as well as their actual physical lives, are outside of school, those differences and disparities come into vivid view. Some students will be fine during this crisis because they’ll have high-quality learning opportunities, whether it’s formal schooling or informal homeschooling of some kind coupled with various enrichment opportunities. Conversely, other students won’t have access to anything of quality, and as a result will be at an enormous disadvantage. Generally speaking, the most economically challenged in our society will be the most vulnerable in this crisis, and the most advantaged are most likely to survive it without losing too much ground.

GAZETTE: Schools in Massachusetts are closed until May 4. Some people are saying they should remain closed through the end of the school year. What’s your take on this?

REVILLE: That should be a medically based judgment call that will be best made several weeks from now. If there’s evidence to suggest that students and teachers can safely return to school, then I’d say by all means. However, that seems unlikely.

GAZETTE: The digital divide between students has become apparent as schools have increasingly turned to online instruction. What can school systems do to address that gap?

REVILLE: Arguably, this is something that schools should have been doing a long time ago, opening up the whole frontier of out-of-school learning by virtue of making sure that all students have access to the technology and the internet they need in order to be connected in out-of-school hours. Students in certain school districts don’t have those affordances right now because often the school districts don’t have the budget to do this, but federal, state, and local taxpayers are starting to see the imperative for coming together to meet this need.

Twenty-first century learning absolutely requires technology and internet. We can’t leave this to chance or the accident of birth. All of our children should have the technology they need to learn outside of school. Some communities can take it for granted that their children will have such tools. Others who have been unable to afford to level the playing field are now finding ways to step up. Boston, for example, has bought 20,000 Chromebooks and is creating hotspots around the city where children and families can go to get internet access. That’s a great start but, in the long run, I think we can do better than that. At the same time, many communities still need help just to do what Boston has done for its students.

Communities and school districts are going to have to adapt to get students on a level playing field. Otherwise, many students will continue to be at a huge disadvantage. We can see this playing out now as our lower-income and more heterogeneous school districts struggle over whether to proceed with online instruction when not everyone can access it. Shutting down should not be an option. We have to find some middle ground, and that means the state and local school districts are going to have to act urgently and nimbly to fill in the gaps in technology and internet access.

GAZETTE : What can parents can do to help with the homeschooling of their children in the current crisis?

“In this situation, we don’t simply want to frantically struggle to restore the status quo because the status quo wasn’t operating at an effective level and certainly wasn’t serving all of our children fairly.”

More like this

The collective effort

Notes from the new normal

‘If you remain mostly upright, you are doing it well enough’

REVILLE: School districts can be helpful by giving parents guidance about how to constructively use this time. The default in our education system is now homeschooling. Virtually all parents are doing some form of homeschooling, whether they want to or not. And the question is: What resources, support, or capacity do they have to do homeschooling effectively? A lot of parents are struggling with that.

And again, we have widely variable capacity in our families and school systems. Some families have parents home all day, while other parents have to go to work. Some school systems are doing online classes all day long, and the students are fully engaged and have lots of homework, and the parents don’t need to do much. In other cases, there is virtually nothing going on at the school level, and everything falls to the parents. In the meantime, lots of organizations are springing up, offering different kinds of resources such as handbooks and curriculum outlines, while many school systems are coming up with guidance documents to help parents create a positive learning environment in their homes by engaging children in challenging activities so they keep learning.

There are lots of creative things that can be done at home. But the challenge, of course, for parents is that they are contending with working from home, and in other cases, having to leave home to do their jobs. We have to be aware that families are facing myriad challenges right now. If we’re not careful, we risk overloading families. We have to strike a balance between what children need and what families can do, and how you maintain some kind of work-life balance in the home environment. Finally, we must recognize the equity issues in the forced overreliance on homeschooling so that we avoid further disadvantaging the already disadvantaged.

GAZETTE: What has been the biggest surprise for you thus far?

REVILLE: One that’s most striking to me is that because schools are closed, parents and the general public have become more aware than at any time in my memory of the inequities in children’s lives outside of school. Suddenly we see front-page coverage about food deficits, inadequate access to health and mental health, problems with housing stability, and access to educational technology and internet. Those of us in education know these problems have existed forever. What has happened is like a giant tidal wave that came and sucked the water off the ocean floor, revealing all these uncomfortable realities that had been beneath the water from time immemorial. This newfound public awareness of pervasive inequities, I hope, will create a sense of urgency in the public domain. We need to correct for these inequities in order for education to realize its ambitious goals. We need to redesign our systems of child development and education. The most obvious place to start for schools is working on equitable access to educational technology as a way to close the digital-learning gap.

GAZETTE: You’ve talked about some concrete changes that should be considered to level the playing field. But should we be thinking broadly about education in some new way?

REVILLE: The best that can come of this is a new paradigm shift in terms of the way in which we look at education, because children’s well-being and success depend on more than just schooling. We need to look holistically, at the entirety of children’s lives. In order for children to come to school ready to learn, they need a wide array of essential supports and opportunities outside of school. And we haven’t done a very good job of providing these. These education prerequisites go far beyond the purview of school systems, but rather are the responsibility of communities and society at large. In order to learn, children need equal access to health care, food, clean water, stable housing, and out-of-school enrichment opportunities, to name just a few preconditions. We have to reconceptualize the whole job of child development and education, and construct systems that meet children where they are and give them what they need, both inside and outside of school, in order for all of them to have a genuine opportunity to be successful.

Within this coronavirus crisis there is an opportunity to reshape American education. The only precedent in our field was when the Sputnik went up in 1957, and suddenly, Americans became very worried that their educational system wasn’t competitive with that of the Soviet Union. We felt vulnerable, like our defenses were down, like a nation at risk. And we decided to dramatically boost the involvement of the federal government in schooling and to increase and improve our scientific curriculum. We decided to look at education as an important factor in human capital development in this country. Again, in 1983, the report “Nation at Risk” warned of a similar risk: Our education system wasn’t up to the demands of a high-skills/high-knowledge economy.

We tried with our education reforms to build a 21st-century education system, but the results of that movement have been modest. We are still a nation at risk. We need another paradigm shift, where we look at our goals and aspirations for education, which are summed up in phrases like “No Child Left Behind,” “Every Student Succeeds,” and “All Means All,” and figure out how to build a system that has the capacity to deliver on that promise of equity and excellence in education for all of our students, and all means all. We’ve got that opportunity now. I hope we don’t fail to take advantage of it in a misguided rush to restore the status quo.

This interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity.

Share this article

You might like.

Former Palestinian Authority prime minister says strengthening execution of 1993 accords could lead to two-state solution

Political philosopher Harvey C. Mansfield says it all goes back to Aristotle, balance of competing ideas about common good

Franklin Foer recounts receding antisemitism of past 100 years, recent signs of resurgence of hate, historical pattern of scapegoating

College accepts 1,937 to Class of 2028

Students represent 94 countries, all 50 states

Pushing back on DEI ‘orthodoxy’

Panelists support diversity efforts but worry that current model is too narrow, denying institutions the benefit of other voices, ideas

Aspirin cuts liver fat in trial

10 percent reduction seen in small study of disease that affects up to a third of U.S. adults

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 22 September 2023

How does the COVID-19 pandemic influence students’ academic activities? An explorative study in a public university in Bangladesh

- Bijoya Saha 1 ,

- Shah Md Atiqul Haq ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9121-4028 1 &

- Khandaker Jafor Ahmed 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 10 , Article number: 602 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

5093 Accesses

1 Citations

Metrics details

The global impact of the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) has spared no sector, causing significant socioeconomic, demographic, and particularly noteworthy educational repercussions. Among the areas significantly affected, the education systems worldwide have experienced profound changes, especially in countries like Bangladesh. In this context, numerous educational institutions in Bangladesh decided to temporarily suspend classes in situations where a higher risk of infection was perceived. Nevertheless, the tertiary education sector, including public universities, encountered substantial challenges when establishing and maintaining effective online education systems. This research uses a qualitative approach to explore the ways in which the COVID-19 pandemic has influenced the academic pursuits of students enrolled in public universities in Bangladesh. The study involved the participation of 30 students from a public university, who were interviewed in-depth using semi-structured interviews. Data analysis was conducted using thematic analysis. The findings of this study reveal unforeseen disruptions in students’ learning processes (e.g., the closure of libraries, seminars, and dormitories, and the postponement of academic and administrative activities), highlighting the complications associated with online education, particularly the limitations it presents for practical and laboratory-based learning. Additionally, a decline in both energy levels and study hours has been observed, along with an array of physical, mental, and financial challenges that directly correlate with educational activities. These outcomes emphasize the need for a hybrid academic approach within tertiary educational institutions in Bangladesh and other developing nations facing similar sociocultural and socioeconomic contexts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Impact of artificial intelligence on human loss in decision making, laziness and safety in education

Sayed Fayaz Ahmad, Heesup Han, … Antonio Ariza-Montes

Interviews in the social sciences

Eleanor Knott, Aliya Hamid Rao, … Chana Teeger

Infectious disease in an era of global change

Rachel E. Baker, Ayesha S. Mahmud, … C. Jessica E. Metcalf

Introduction and background

The current global issue, the COVID-19 pandemic caused by the novel coronavirus, is impacting both developed and developing nations (World Health Organization [WHO], 2020 ). Many countries have implemented worldwide lockdowns, enforced social isolation measures, bolstered healthcare services, and temporarily closed educational institutions in order to curb the spread of the virus. According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO, 2020a ), the closure of schools, colleges, universities, and other educational establishments due to COVID-19 has impacted over 60% of students worldwide. The pandemic is inflicting significant damage upon the global education sector. University students, in particular, are grappling with notable disruptions to their academic and social lives. The uncertainties surrounding their future goals and careers, coupled with the limitations on social interaction with friends and family (Cao et al., 2020 ), have left them contending with altered living conditions and increased workload demands compared to the time before traditional classroom teaching was suspended. Despite these challenges, the university setting and its associated activities have become the sole familiar constant amidst their otherwise transformed lives (Neuwirth et al., 2021 ). The pandemic’s interference with academic routines has substantially interrupted students’ educational journeys (Charles et al., 2020 ). The shutdown of physical classrooms and the halt of academic operations due to university closures (Jacob et al., 2020 ) have disrupted students’ study routines and performance. Prolonged periods of solitary studying at home have been linked to heightened stress levels (e.g., depression), feelings of cultural isolation (e.g., loneliness), and cognitive disorders (e.g., difficulty in retaining recent and past information) (Meo et al., 2020 ). Many educational institutions have responded to COVID-19 by transitioning from traditional face-to-face instruction to online alternatives to minimize educational disruptions. However, research indicates that students often feel uncomfortable and dissatisfied with online learning methods (Al-Tammemi et al., 2020 ). Beyond the challenges posed by online education, such as limited access to electronic devices, restricted internet connectivity, and high internet costs, students are also faced with adapting to new online assessment techniques and technologies, engaging with instructors, and navigating the complexities of the shift to online delivery (Owusu-Fordjour et al., 2020 ).

Bangladesh, a South Asian developing nation, has also been significantly impacted by COVID-19. To prevent the virus’s spread, the country opted to close its educational institutions, leading to students staying home to maintain social distancing (Institute of Epidemiology Disease Control and Research [IEDCR], 2020 ). The higher education sector in Bangladesh encountered challenges during this period. The closure of educational institutions disrupted students’ learning activities (UNESCO, 2020b ; Al-Tammemi et al., 2020 ). Modern technology tools and software have become the means through which most university students engage in study-related tasks at home during their free time. The shift to online education is seen as a fundamental transformation in higher education in Bangladesh, departing from the traditional academic approach. However, for many teachers and administrators at Bangladeshi institutions, online education is a new frontier. Face-to-face teaching and learning have been the predominant mode at Bangladeshi universities for a long time, making it challenging to embrace the shift to an advanced online environment.

Bangladesh hosts more than 5,000 higher education institutions, encompassing both government and private universities, vocational training centers, and affiliated colleges, with an enrollment of 4 million students (Ahmed, 2020 ). In response to the health crisis, the government introduced emergency online education methods to enable students to continue learning despite temporary school closures. Challenges such as overcrowding, unequal access to technology compared to pre-COVID-19 times, and the difficulties in swift adaptation led to delays, teaching interruptions, and the adoption of extended distance learning. These issues were further exacerbated by the ongoing overcrowding, which posed a risk for the resurgence or spread of COVID-19 if in-person teaching were to resume. Undoubtedly, COVID-19 has left a profound impact on university education in Bangladesh. Despite numerous studies on COVID-19’s impact on a range of topics, the effects on higher academic activities in Bangladesh have received limited research attention. Shahjalal University of Science and Technology (SUST), a public institution and one of Bangladesh’s universities, stands as an example. Given the COVID-19 regulations, this study aims to investigate the effects of online learning on the academic endeavors of university students in Bangladesh. The study also seeks to assess students’ satisfaction with online education, their adaptability to this new format, and their participation in extracurricular activities during the COVID-19 period, in addition to their academic pursuits.

Literature review

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a notable impact on the landscape of online teaching and learning (Aldowah et al., 2019 ; Basilaia and Kvavadze, 2020 ; Khan and Abdou, 2021 ). Notably, Rameez et al. ( 2020 ) emphasize that a critical hurdle faced in Sri Lanka revolves around the lack of virtual teaching and learning proficiency among both educators and students, impeding a smooth educational process. University shutdowns and dormitory quarantines due to COVID-19 have significantly disrupted students’ learning abilities (Burgess and Sievertsen, 2020 ; Kedraka and Kaltsidis, 2020 ). Difficulties have arisen, encompassing challenges related to online lectures, exams, evaluations, reviews, and tutoring. While Kedraka and Kaltsidis ( 2020 ) laud online learning as modern, relevant, suitable, and advantageous, they also underline its drawbacks. Notably, it has led to a substantial loss of student social interaction, interrupting group learning, in-person interactions, and connections with peers and educators (Kedraka and Kaltsidis, 2020 ; Rameez et al., 2020 ).

In the context of higher education institutions in Bangladesh, Khan and Abdou ( 2021 ) propose adopting the flipped classroom method to sustain teaching and learning during the COVID-19 epidemic, an approach echoed in Alam’s ( 2021 ) comparison of pre-and post-pandemic students. Alam’s findings reveal better academic performance among post-pandemic students. Conversely, Biswas et al. ( 2020 ) report a positive attitude toward mobile learning among most students in Bangladesh, finding it effective in bridging knowledge gaps created by the pandemic. Emon et al. ( 2020 ) highlight discontinuities in learning opportunities in Bangladesh, emphasizing the need for technical solutions to maintain effective education systems during the pandemic. Ahmed’s ( 2020 ) study on tertiary students unveils a lack of technology and connectivity, leading to delays in coursework, exams, results, and class promotions. These disruptions have exacerbated student anxiety, frustration, and disappointment. Burgess and Sievertsen ( 2020 ) note students’ concerns about falling behind academically, missing job opportunities, facing post-graduation employment challenges, and enduring emotional pressure.

Rajhans et al. ( 2020 ) observe that the pandemic has driven significant advancements in academies worldwide, particularly in adopting online learning. A similar impact is seen in India’s optometry academic activities, where quick adoption of online learning supports both students and practising optometrists (Stanistreet et al., 2020 ). Consequently, educational events like commencement ceremonies, seminars, and sports have been postponed or canceled (Liguori and Winkler, 2020 ; Sahu, 2020 ; Shrestha et al., 2022 ), necessitating remote work for academic support staff (Abidah et al., 2020 ).

In higher education, teachers play a pivotal role in implementing online learning. The sudden shift to online education due to the pandemic has left some instructors grappling with limited IT skills and a challenge in maintaining the same level of engagement as in face-to-face settings (Meo et al., 2020 ; Wu et al., 2020 ). Furthermore, the transition has led to concerns about effective scheduling, course organization, platform selection, and measuring online education’s impact (Wu et al., 2020 ; Toquero, 2020 ). Zawacki-Richter ( 2021 ) predicts digital advancements in German higher education, driven by the crisis, faculty dedication, and higher expectations.

COVID-19’s influence on education extends to students’ mental well-being. Some students’ inadequate home networks have hindered access to online materials, exacerbating their distress (Akour et al., 2020 ). Mental health challenges stem from various sources, including parental pressures, financial strains, and family losses (Bäuerle et al., 2020 ). Long-term quarantine intensifies psychological and learning challenges, impacting students’ overall performance and study time (Farris et al., 2021 ; Meo et al., 2020 ). Blake et al. ( 2021 ) advocate for colleges to address students’ isolation needs and prepare for long-term effects on student welfare.

With its large population, Bangladesh grapples with challenges in effective technology adoption, especially with online education becoming an alternative system during the pandemic. The overcrowding issue has been exacerbated by the need for distance learning, causing skill transfer difficulties and delays. Given these circumstances, this study delves into how COVID-19 affects online education and Bangladeshi university students’ academic endeavors, offering insights from the students’ perspective. Unlike prior studies focusing on challenges, this research also uncovers opportunities triggered by the pandemic. Such a nuanced view of the impacts of COVID-19 on education will help formulate effective policies and programs to elevate online learning quality in Bangladesh’s higher education.

Methodology

Research design.

This study employs a descriptive research approach, which aims to portray a situation, an individual, or an event and illustrate phenomena’ connections and natural occurrences (Blumberg et al., 2005 ). A qualitative approach was adopted to analyze specific circumstances thoroughly. Grounded theory, developed by Glaser and Strauss in 1967, served as the overarching framework for this research (Denscombe, 2007 ). Grounded theory follows an inductive research approach that refrains from starting with preconceived assumptions and instead generates new questions as insights emerge. This methodology rests upon participants’ perspectives, experiences, and realities (Bytheway, 2018 ).

For this study, in-depth interviews were employed to assess how the recent pandemic impacted students’ academic engagement and the factors related to COVID-19 that influenced their academic activities. This examination sought to understand the pandemic’s implications on students, the facets of these consequences, and which students might be more susceptible to these effects concerning academic performance and engagement. Conducted over the phone, the in-depth interviews featured a relatively small of participants, leading to the choice of a descriptive study design. This design, however, is unable to establish causal relationships, which could be explored and compared using quantitative methodologies. Moreover, the potential influence of the interviewer’s presence during phone interviews was considered.

Study locations, population, and sample

This study delves into the academic challenges encountered by students during the COVID-19 lockdown. Shahjalal University of Science and Technology (SUST), a public university in Bangladesh’s Sylhet district, was purposefully selected for the study due to its high student enrollment. The participants consist of students from diverse disciplines of SUST. Employing purposive sampling, a non-probability sample technique, the research collected qualitative data through volunteers recruited via social media advertisements within a university group on Facebook. Participants were informed of the study’s objectives, and the data collection spanned from September 20 to October 3, 2021, supplemented by additional interviews from December 24 to December 27, 2021, to ensure data saturation. Information from 30 university students was gathered, covering a range of faculties. Table 1 provides an overview of participant’s age, gender, and educational level: 56.7% of participants identified as female, and 43.3% as male. In terms of educational distribution, 87% were enrolled in Bachelor’s degree programs, while 13% were pursuing Master’s degrees. The participants’ ages from 18 to 25 years, with a mean of 21.37 and a standard deviation of 1.99.

Data collection and data analysis

The research team, comprising a graduate student (B.S.) with qualitative research training, a sociology professor (S.M.A.H., PhD) with extensive qualitative and quantitative experience, and a sociology postdoctoral fellow (K.J.A., PhD), handled data collection and analysis. In-depth interviews, facilitated by a semi-structured interview instrument, were employed to gather for this qualitative study. This approach allowed participants to provide substantial insights by responding to open-ended questions on the research topic. The interviews explored the impact of COVID-19 on students’ academic activities, their online learning experiences, and the effects of the pandemic on educational pursuits. Ethical guidelines concerning confidentiality, informed consent, the use of data only for the present study, and non-disclosure were followed throughout the data collection, and the participation was voluntary, and they could withdraw their participation at any time during the research process. Participants were informed about the research through a participation information sheet prior to their involvement, and their consent was obtained in written form through email correspondence. Interviews were carried out in Bengali by the first author (B.S.) phone calls and were recorded. Subsequently, the recorded interviews were promptly transcribed into English using a word processing program.

The collected data underwent thorough analysis involving coding in Microsoft Excel, interpretation, and validation through discussions among the research team. Themes and subthemes emerged during the coding process, guiding the categorization and organization of data. Saturation was achieved after the 30th interview, indicating data sufficiency. The research team, without prior relationship with participants, ensured the reliability and credibility of the analysis through verbatim transcripts, individual and group analysis, and written notes.

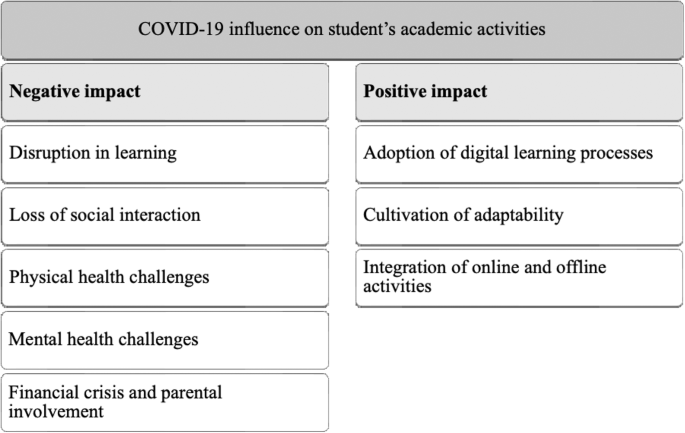

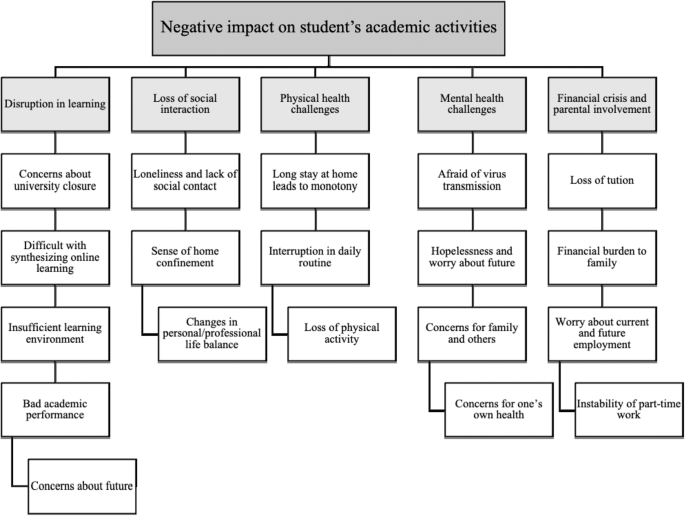

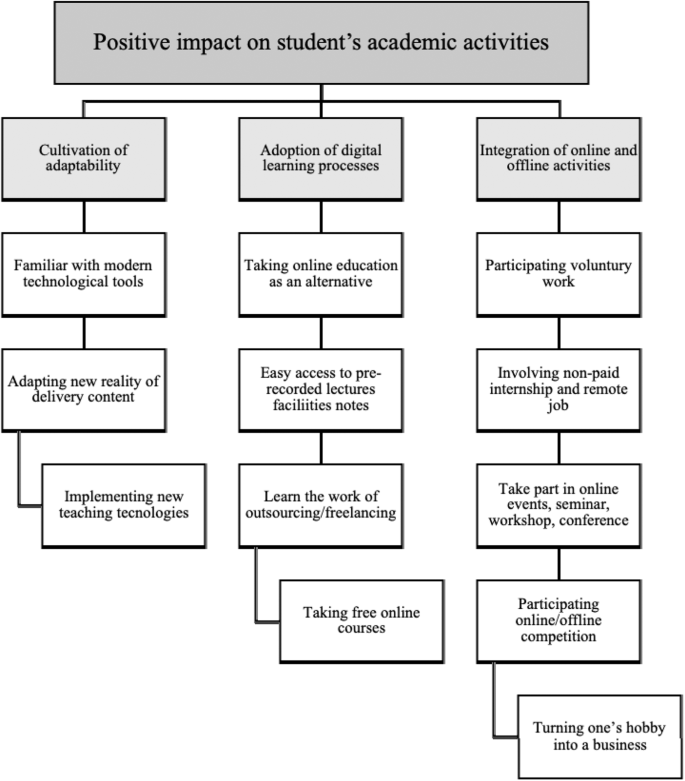

The research identified eight themes (see Fig. 1 ) that characterized two main factors: the negative impact on student academic activities (see Fig. 2 ) and the positive impact on academic activities (see Fig. 3 ). The negative impact encompassed themes such as learning disruption, loss of social interaction, physical and mental health issues, financial struggles, and parental involvement. The positive impact included themes such as digital learning, adaptability, and engagement in online/offline activities. In-depth analyses were conducted for each theme, accompanied by citations indicating the participant’s identification number and gender.

Note: see Figs. 2 and 3 for subthemes of academic activities.

Negative impacts on student’s academic activities.

Positive impact on student’s academic activities.

Negative impact on student’s academic activities

Disruption in learning.

In the early months of 2020, the global spread of COVID-19 prompted the government of Bangladesh to close all educational institutions due to suspicious incidents. Participants unanimously expressed their initial surprise and frustration at the abrupt closure but soon recognized its necessity in the face of the pandemic. Libraries, seminars, and dormitories were immediately shut down. This posed a challenge for students residing on campus, who had quickly departed and lacked access to necessary resources. Academic and administrative activities across these institutions came to a halt. Alongside the strain of crowded classrooms, students voiced discontent, uncertainty, and anxiety about their studies, assessments, and outcomes.

Several participants shared their experiences:

“I used to follow the teachers’ instructions, attend lectures, and complete projects. But now that classes are suspended, my studying has come to a halt. I worry this pause might be prolonged.” (M 7 , M 14 , F 17 )

These students identified various obstacles to effective learning. They found the absence of a structured routine for attending classes and lectures at home demotivating. Although they kept busy with other activities, they noted a decline in their enthusiasm for education. They struggled to retain and apply the knowledge gained from classes, attributing it to the sudden disruption. Limited access to educational materials and books, often left behind in campus dormitories, also hindered their learning progress. Reading from the library, they mentioned, was a costly alternative. As a result, the inability to access essential resources posed a challenge. Furthermore, students found it difficult to concentrate on their studies due to unsuitable home environments, impacting their academic performance.

A participant shared:

“I need a quiet study environment, which I can’t find at home. I used to study at departmental seminars or the library. Even though I’ve been home, I still struggle to concentrate.” (M 1 )

Another student added:

“The university closed shortly after I enrolled. As a result, I missed out on getting to know my peers, professors, and seniors. I couldn’t enjoy the university’s cultural activities and events.” (F 30 )

Several participants said,

“The vast majority of their courses are laboratory-based. Taking these classes online during COVID-19 made them difficult to understand, and even the teachers struggled to understand them.” (M 4, M 19, F 29, F 30 )

Loss of social interaction

Students strongly desired to return to their educational environment and reconnect with peers and professors. Collaborative problem-solving and discussions with batchmates were a common practice, and the absence of in-person interactions disrupted this dynamic. They found comfort in studying together on campus, rather than in isolation at home. The prolonged separation from friends and classmates resulted in a breakdown of peer learning processes. While attempts were made to stay connected through digital means, participants found these interactions lacking in the vibrancy of face-to-face communication. Recalling earlier interactions for study or leisure became challenging, eroding the motivation to learn.

One participant noted:

“Group study is no longer possible due to the pandemic, and my interest in studying has waned. This could pose communication challenges even after the pandemic subsides.” (M 19 )

Others explained:

“I can’t interact with my friends or have the same enjoyment as before due to extended periods at home. This saddens me. It’s made studying with them much harder. I anticipate a communication gap post-pandemic, as we might forget how to engage openly.” (F 12 )

Another student expressed:

“I was admitted to the university, but it closed just a month later. This meant that I didn’t have the chance to get to know my fellow students, teachers, or seniors. I also missed out on the university’s cultural activities, concerts, and festivals.” (F 29 )

Physical health challenges

The participants pointed out that COVID-19 had wide-ranging effects on their daily routines. They noted shifts in sleep patterns, eating habits, and physical activity levels, leading to daytime fatigue, disrupted sleep, reduced appetite, and sedentary behavior, resulting in weight gain. These physical symptoms contributed to a sense of exhaustion, weakness, and overall discomfort. Many participants linked these physical challenges to their waning interest in studying at home, creating a disconnect from their academic pursuits.

One participant shared:

“I have gained weight due to excessive eating and spending all day at home. My body feels heavy, my mind feels foggy, and I experience a mix of happiness and lethargy. Is this is an environment conducive to studying?” (M 4 )

Another student explained:

“I have polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS), which requires a balanced lifestyle. I exercised and ate well on campus, keeping my physical condition in check. But with the shift to remote learning, my routine changed, worsening my physical health. This has affected my concentration on studies, adding to my frustration.” (F 9 )

Mental health challenges

Stress emerged as a prevailing mental health concern among participants. They exhibited heightened anxiety, not only due to the pandemic itself but also concerning their educational commitments. In addition to fears of contracting COVID-19, participants expressed concern about maintaining organization, motivation, and adapting to new learning methods. Worries extended to upcoming courses, exams, result publication, and starting a new academic year. The post-epidemic landscape was also concerned with the potential pressure to expedite course completion. These uncertainties overshadowed the primary goals of their educational journey.

A number of participants found themselves increasingly frustrated when contemplating their future professional aspirations. Their anxiety and anger stemmed from the inability to finish their final year of university as planned. The pandemic further amplified their concerns about securing employment and setting a stable foundation for themselves. They argued that an extended academic year could impede their career opportunities and create challenges in securing a post-graduation job. Moreover, there was a prevailing fear that their relatively advanced age might hinder their employability in Bangladesh.

Several participants elaborated:

“Most government and private sector jobs in Bangladesh have age restrictions. Exam topics often diverge from the academic curriculum. The prolonged academic year due to COVID-19 makes me uncertain about my job prospects. Global economic instability adds to my worries. This anxiety affects my ability to focus, leaving me disinterested in everything, including studying .” (M 16 , M 4 , F 10 )

For female participants, the pressure to marry before completing their education emerged as an additional concern, leading to emotional distress and academic setbacks. Some female participants added:

“Given the uncertainty surrounding when the pandemic would conclude and when we would have the opportunity to complete our studies, our families urged us to consider marriage before finishing our education. This predicament weighed heavily on us, causing a sense of melancholy, and subsequently, academic performance suffered as we grappled with the idea of getting married before our graduation.” (F 17 , F 20 , F 21 , F 10 )

Financial crisis and parental involvement

COVID-19’s economic impact was deeply felt among participants, who relied on part-time jobs or tuition to support themselves. The abrupt halt in academic and work activities severely impacted their financial stability. With local and global economies suffering, family incomes dwindled, making it harder for students to afford internet connectivity and online resources.

“My ability to attend online classes suffered due to my family’s limited finances. I feared my grades would suffer and I might fail courses.” (F 28 )

Additionally, the prolonged closure of institutions resulted in difficult conditions for many students. Financial hardships and familial challenges, such as job loss, reduced income, and parental pressure, further exacerbated students’ emotional distress. Having lost a parent before the pandemic, some students found it even harder to make ends meet.

One participant explained:

“I supported my family and myself with tuition before COVID-19. Losing my father earlier made me the sole provider. But with COVID-19, I had to forfeit my tuition and supporting my family became a struggle.” (M 27 )

Positive impact on student academic activities

Adoption of digital learning processes.

Amidst the challenges posed by the pandemic, integrating technology into education stands out as a significant advantage. The global situation intensified the strong connection between technology and education. The closure of institutions led to a swift transformation of on-campus courses into online formats, turning e-learning into a vital method of instruction. This shift extended beyond content delivery to encompass pedagogy and assessment methods changes. The participants adapted to Zoom, Google Meet, and Google Classroom platforms for attending online lectures. They found pre-recorded classes accessible through online media, simplifying note-taking. Asking questions online became convenient, and submitting online assignments posed no significant hurdles. Many students also embraced the opportunity to engage with the free online courses from platforms such as Coursera, edX, and Future Learn, further enhancing their skill sets.

“Recorded lectures are a boon; I can revisit them whenever I want. I don’t need to focus on note-taking during class since I can easily access the lectures later.” (F 3 )

Another participant noted:

“I enrolled in several free online courses during COVID-19, using platforms such as Coursera, edX, and Future Learn. These tasks boosted my productivity and introduced me to the world of freelancing.” (F 6 )

Cultivation of adaptability

The pandemic propelled digital technologies to the forefront of education. The transition to digital learning required both educators and students to enhance their technological literacy. This shift also paved the way for pedagogy and curriculum design innovation, fostering changes in learning methods and assessment techniques. As a result, a large group of students could simultaneously engage in learning. Forced to embrace technology due to the pandemic, participants improved their digital literacy.

Participants commended the Bangladeshi government’s shift from traditional face-to-face learning to online education as a necessity. They recognized the efficacy of online learning in the local context and found inspiration in mastering new technologies. Many educators sought to improve the effectiveness of online courses, making the most of available resources. Participants gained familiarity with technology tools and demonstrated their adaptability and commitment to mastering new skills.

A male participant said:

“An unexpected opportunity arose amidst the pandemic. Virtual learning was the need of the hour. Adapting to this sophisticated technology was initially challenging, but I eventually became comfortable with the new mode.” (M 29 )

Integration of online and offline activities

The pandemic prompted students to diversify their activities. They devoted time to hobbies such as farming, painting, gardening, and crafts. Engaging in extracurricular activities such as cooking, volunteering, attending religious events, and using social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram became a norm. Some events created uplifting content for social media, using platforms as a potential source of income. Others embarked on online entrepreneurship ventures, reflecting their entrepreneurial spirit. Volunteering became appealing, bridging the gap between virtual and physical engagement.

Two participants shared:

“I wasn’t part of any groups during my student years. However, I joined several volunteer groups during COVID-19. These efforts included both offline initiatives such as distribution of food and masks, online initiatives.” (F 15 , M 18 )

Another participant shared:

“I had time for myself after extensive studying. I explored various creative pursuits, cooked using YouTube recipes, and found joy in them. I am considering a career in cooking.” (F 11 )

Another participant expressed:

“Amidst this time apart, many companies and organizations offer unpaid internships. I have participated in such an internship, attended seminars, conferences, workshops, and events. This period has enriched both my soft and hard skills, and I have participated in various physical and online events.” (M 22 )

The primary objective of this study was to assess the impact of COVID-19 on the academic activities of university students. The study aimed to understand students’ satisfaction with online education during the pandemic, their responses to this learning mode, and their engagement in non-academic activities. The pandemic has significantly disrupted not only regular teaching and learning at our university but also the lives of our students. Amid this outbreak, several students found solace in spending quality time with their families and tackling long-postponed household chores. It is crucial to acknowledge that a diverse range of circumstances, personalities, and coping mechanisms exist within human communities like ours. Despite these variations, the resilience exhibited by the individuals in this study stands out remarkably.

In recent research, educational institutions, particularly public universities, adopted digital online learning and assessment platforms to respond to the pandemic (Blake et al., 2021 ; Wu et al., 2020 ). Consequently, participants in our study discussed their experiences with digital platforms during COVID-19, highlighting both positive and negative impact on academic activities (see Figs. 1 – 3 ).

Our findings demonstrate that online learning offers benefits by enhancing educational flexibility through the accessibility and user-friendliness of digital platforms. These findings align with those of Kedraka and Kaltsidis ( 2020 ), who identified convenience and accessibility as primary advantages of remote learning. Moreover, Burgess and Sievertsen ( 2020 ) emphasized the potential of distance learning and technology-enabled indirect instruction, while Basilaia and Kvavadze ( 2020 ) underscored technology’s role in driving educational adaptation during a pandemic.

According to our study, the pandemic led to students’ significant loss of social connections. Collaborative group study plays a pivotal role in conceptual understanding and academic progress. However, due to the outbreak, students’ routine group study sessions in libraries or on campus, face-to-face interactions, and conversations with peers and educators suffered setbacks. These disruptions might potentially impact their motivation for sustained high-level learning. Participants voiced concerns about online learning, including the absence of human interaction, challenges in maintaining audience engagement, and, most notably, the inability to acquire practical skills. These limitations have been observed previously, indicating that these teaching and learning methods are hindered by constraints in conducting laboratory work, providing hands-on experience, and delivering comprehensive feedback to students, leading to reduced attention spans (Zawacki-Richter, 2021 ).

Likewise, Naciri et al. ( 2020 ) highlighted educators’ difficulties in sustaining student engagement, multitasking during virtual sessions, subpar audio and video quality, and connectivity issues. In our study, students reported that the quality of their internet connection directly influenced their online learning experience. They also expressed frustration at the extended screen time and feelings of fatigue. To address these concerns, experts recommended utilizing tools such as live chat, pop quizzes, virtual whiteboards, polls, and reflections to structure shorter, more interactive sessions.

Consistent with prior research, our recent poll findings suggested that participants were more surprised than disappointed by the swift decision to close educational institutions nationwide. Moreover, the study revealed that the prolonged closure of universities and confinement to homes led to substantial disruptions in students’ learning, aligning with findings from various studies that highlight disturbances in daily routines and studies (Meo et al., 2020 ), limited access to educational resources due to closed libraries, difficulties in learning at home, disruptions in the household environment, and challenges in retaining studied material (Bäuerle et al., 2020 ). All participants expressed some degree of apprehension. Staying at home exacerbated both physical and mental health issues. Study habits suffered, and interest in learning waned. Physical health concerns excessive daytime sleepiness, disrupted nocturnal sleep patterns, decreased appetite, sedentary behavior, weight gain or obesity, as well as feelings of fatigue, dizziness, and listlessness. Toquero ( 2020 ) noted similar issues, outlining the impact of COVID-19 on children’s mental health and educational performance. Delays in examinations, results, and promotions to the next academic level intensified student stress, echoing findings by Sahu ( 2020 ).

As an unintended outcome of the pandemic, online alternatives to traditional higher education have gained prominence, particularly in Bangladesh. However, these methods are not without their limitations. The study identified persistent challenges in Bangladesh’s online education system, including a lack of electronic devices such as laptops, smartphones, computers, and essential tools for online courses. Additionally, limited or absent internet access, expensive mobile data packages or broadband connections, disruptions during online classes due to slow or unstable internet speeds, and frequent power outages in both urban and rural areas hamper the efficacy of online learning. These findings echo prior research (Aldowah et al., 2019 ; Liguori and Winkler, 2020 ).

Amidst the challenges, the study also unveiled positive outcomes in academic pursuits. Students reported spending more time engaging with television, movies, YouTube videos, computer and mobile device gaming, and social networking platforms like Facebook and Instagram compared to pre-pandemic times. Some students even took a break from their studies due to university closures. They capitalized on online platforms such as Coursera, edX, and FutureLearn during their downtime at home, while others embraced hobbies like cooking and drawing. Furthermore, students actively participated in voluntary extracurricular activities, such as freelancing, unpaid internships, remote jobs, virtual conferences, seminars, webinars, workshops, and various competitions. These findings parallel those of Ali ( 2020 ), underscoring students’ varied engagement during the pandemic. In response, students proposed suggestions for enhancing educational operations, including reducing homework loads, minimizing screen time, and improving lecture delivery. Scholars like Ferrel and Ryan ( 2020 ) have recommended reducing cognitive load, enhancing engagement, implementing identity-based access, introducing case-based learning, and employing comprehensive assessments.

In conclusion, this study sheds light on the multifaceted impacts of COVID-19 on university students’ educational experiences. The pandemic prompted an accelerated shift towards digital learning, demonstrating advantages and limitations. Despite the challenges, students exhibited resilience and adaptability. As we navigate these uncharted waters, embracing the positive aspects of technology-enabled education while addressing its challenges will be pivotal for ensuring continued learning excellence.

Bangladesh boasts diverse educational institutions, ranging from colleges and universities to schools and beyond. The widespread repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic have jolted the global academic community. This study delves into how COVID-19 has influenced students’ academic performance, encompassing emotional well-being, physical health, financial circumstances, and social relationships. However, certain aspects of the curriculum, particularly science and technology-focused areas involving online lab assessments and practical courses, present challenges. Despite its adverse effects on academic activities, COVID-19 has ushered in positive outcomes for several students, revealing successful interactions with virtual education and contentment with online learning methods.

This study paves the way for further research to refine the online learning environment in Bangladeshi public universities. The findings indicate that the current strategies employed for online university teaching may lack the motivational impetus required to elevate students’ comprehension levels and actively involve them in the learning process. Consequently, there is room for conducting additional studies to enhance the online learning experience, benefiting both educators and students alike. Higher education institutions need to exert concerted efforts to establish sustainable solutions for Bangladesh’s educational challenges in the post-COVID era. A hybrid learning approach, blending online and offline components, emerges as a potentially effective strategy to navigate future situations akin to COVID-19. A collaborative effort involving governments, organizations, and educators is imperative to bridge educational gaps within this framework. Governments could play a pivotal role by providing ICT training to instructors and students, fostering a more technologically adept academic community.

This research furnishes policymakers with insights to devise strategies that mitigate the detrimental impacts of crises such as pandemics on the educational system. Notwithstanding its limitations, including a confined sample size and the sole focus on a single university within a specific country, the study contributes valuable data. This research serves as a foundation, particularly in a science and technology-focused institution where the transition to online formats is intricate due to the nature of practical courses and lab work. This information could prove invaluable to Bangladesh’s Ministry of Education as it formulates policies to counteract the adverse effects of crises on the educational realm.

Furthermore, this study serves as a springboard for subsequent investigations into the far-reaching implications of COVID-19 on academic engagement. Expanding the scope, larger-scale studies could be conducted in various locations to enrich the data pool. Additionally, considering the perspectives of professors and other stakeholders within higher education is an avenue for future exploration. Employing quantitative research methodologies with substantial sample sizes can ensure the broader applicability of the results. This study offers a multifaceted view of how COVID-19 has permeated students’ academic pursuits, opening doors for comprehensive research and proactive policy-making in education.

Data availability

The data collected from the participants in the study cannot be shared, since participants were explicitly informed during the qualitative data collection process that their information would remain confidential and not be disclosed. Participants provided consent solely for the collection of relevant data for the study.

Abidah A, Hidaayatullaah HN, Simamora RM et al. (2020) The impact of COVID-19 to Indonesian education and its relation to the philosophy of “Merdeka Belajar”. Stud Philos Sci Educ 1(1):38–49. http://scie-journal.com/index.php/SiPoSE

Article Google Scholar

Ahmed M (2020) Tertiary education during COVID-19 and beyond. The Daily Star. https://www.thedailystar.net/opinion/news/tertiary-education-during-covid-19-and-beyond-1897321

Akour A, Al-Tammemi AB, Barakat M et al. (2020) The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and emergency distance teaching on the psychological status of university teachers: a cross-sectional study in Jordan. Am J Trop Med Hygiene 103(6):2391–2399. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.20-0877

Article CAS Google Scholar

Alam GM (2021) Does online technology provide sustainable HE or aggravate diploma disease? Evidence from Bangladesh—a comparison of conditions before and during COVID-19. Technol Soc 66:101677. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2021.101677

Aldowah H, Al-Samarraie H, Ghazal S (2019) How course, contextual, and technological challenges are associated with instructors’ challenges to successfully implement e-learning: a developing country perspective. IEEE Access 7:48792–48806. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2910148

Al-Tammemi AB, Akour A, Alfalah L (2020) Is it just about physical health? An internet-based cross-sectional study exploring the psychological impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on university students in Jordan amid COVID-19 pandemic. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.562213

Ali W (2020) Online and remote learning in higher education institutes: a necessity in light of COVID-19 pandemic. Higher Educ Stud 10(3):16–25

Basilaia G, Kvavadze D (2020) Transition to online education in schools during a SARS-CoV-2 Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Georgia. Pedagog Res 5(4):em0060. https://doi.org/10.29333/pr/7937

Bäuerle A, Skoda EM, Dörrie N et al. (2020) Correspondence psychological support in times of COVID-19: the essen community-based cope concept. J Public Health 42(3):649–650. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa053

Biswas B, Roy SK, Roy F (2020) Students perception of mobile learning during COVID-19 in Bangladesh: University student perspective. Aquademia 4(2):ep20023. https://doi.org/10.29333/aquademia/8443

Blake H, Knight H, Jia R et al. (2021) Students’ views towards SARS-Nov-2 mass asymptomatic testing, social distancing, and self-isolation in a university setting during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(8):4182. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/8/4182

Blumberg B, Cooper DR, Schindler PS (2005) Business research methods. McGraw-Hill, Maidenhead

Google Scholar

Burgess S, Sievertsen HH (2020) Schools, skills, and learning: the impact of COVID-19 on education. https://voxeu.org/article/impact-covid-19-education

Bytheway J (2018) Using grounded theory to explore learners’ perspectives of workplace learning. Int J Work Integrated Learn 19(3):249–259

Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G et al. (2020) The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res 287:112934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Charles NE, Strong SJ, Burns LC et al. (2020) Increased mood disorder symptoms, perceived stress, and alcohol use among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res 296:113706, https://psyarxiv.com/rge9k10.31234/osf.io/rge9k

Denscombe M (2007) The good research guide for small-scale social research projects, 3rd ed. Open University Press, Maidenhead, UK

Emon EKH, Alif AR, Islam MS (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on the institutional education system and its associated students in Bangladesh. Asian J Educ Soc Stud 11(2):34–46. https://doi.org/10.9734/ajess/2020/v11i230288

Farris SR, Grazzi L, Holley M (2021) Online mindfulness may target psychological distress and mental health during COVID-19. Glob Adv Health Med. https://doi.org/10.1177/21649561211002461

Ferrel MN, Ryan JJ (2020) The impact of COVID-19 on medical education. Cureus 12(3):e7492. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7492

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Institute of Epidemiology, Disease Control and Research (IEDCR) (2020) COVID-19 vital statistics. IEDCR, Dhaka. https://iedcr.gov.bd

Jacob ON, Abigeal I, Lydia AE (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on the higher institutions development in Nigeria. Electron Res J Soc Sci Humanit 2:126–135. http://www.eresearchjournal.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/0.-Impact-of-COVID.pdf

Kedraka K, Kaltsidis C (2020) Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on university pedagogy: students’ experiences and consideration. Eur J Educ Stud 7(8):3176. https://doi.org/10.46827/ejes.v7i8.3176

Khan MSH, Abdou BO (2021) Flipped classroom: how higher education institutions (HEIs) of Bangladesh could move forward during COVID-19 pandemic. Soc Sci Humanit Open 4(1):100187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100187

Liguori E, Winkler C (2020) From offline to online: challenges and opportunities for entrepreneurship education following the COVID-19 pandemic. Entrep Educ Pedagogy 3(4):346–351. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515127420916738

Meo SA, Abukhalaf AA, Alomar AA et al. (2020) COVID-19 pandemic: impact of quarantine on medical students’ mental wellbeing and learning behaviors. Pakistan J Med Sci 36(COVID19-S4):S43–S48. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.36.COVID19-S4.2809

Naciri A, Baba MA, Achbani A et al. (2020) Mobile learning in higher education: unavoidable alternative during COVID-19. Academia 4(1):ep20016. https://doi.org/10.29333/aquademia/8227

Neuwirth LS, Jović S, Mukherji BR (2021) Reimagining higher education during and post-COVID-19: challenges and opportunities. J Adult Continuing Educ 27(2):141–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477971420947738

Owusu-Fordjour C, Koomson CK, Hanson D (2020) The impact of COVID-19 on the learning-the perspective of the Ghanaian student. Eur J Educ Stud. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3753586

Rajhans V, Memon U, Patil V et al. (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on academic activities and way forward in Indian Optometry. J Optom 13(4):216–226. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1888429620300558

Rameez A, Fowsar MAM, Lumna N (2020) Impact of COVID-19 on higher education sectors in Sri Lanka: a study based on the South Eastern University of Sri Lanka. J Educ Soc Res 10(6):341–349. http://192.248.66.13/bitstream/123456789/5076/1/12279-Article%20Text-44384-1-10-20201118.pdf

Sahu P (2020) Closure of universities due to Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus 12(4):e7541. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.7541

Shrestha S, Haque S, Dawadi S et al. (2022) Preparations for and practices of online education during the COVID-19 pandemic: a study of Bangladesh and Nepal. Educ Inf Technol 27(1):243–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10659-0

Stanistreet P, Elfert M, Atchoarena D (2020) Education in the age of COVID-19: understanding the consequences. Int Rev Educ 66(5–6):627–633. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-020-09880-9

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Toquero CM (2020) Challenges and opportunities for higher education amid the COVID-19 pandemic: yhe Philippine context. Pedagog Res 5(4):em0063. https://doi.org/10.29333/pr/7947

UNESCO (2020a) Adverse consequences of school closures. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse/consequences

UNESCO (2020b) Education: from disruption to recovery. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse

World Health Organization (WHO) (2020) Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) situation report-1. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronavirus/situationreports/20200121-sitrep-1-2019-ncov.pdf?sfvrsn=20a99c10_4

Wu Y, Xu X, Chen Z et al. (2020) Nervous system involvement after infection with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Brain Behav Immun 87:18–22. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1603.091216

Zawacki-Richter O (2021) The current state and impact of COVID-19 on digital higher education in Germany. Hum Behav Emerg Technol 3(1):218–226. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbe2.238

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Sociology, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet, 3114, Bangladesh

Bijoya Saha & Shah Md Atiqul Haq

The Institute for the Study of International Migration (ISIM), Walsh School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University, 3700 O Street NW, Washington, DC, 20057, USA

Khandaker Jafor Ahmed

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Shah Md Atiqul Haq .

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval.

At the time the study was undertaken, there was no official ethics committee. Since it is crucial that ethical reviews occur before the start of every research, retrospective approval for completed studies like this study is not practicable. To ensure the safety of participants and the validity of the study, the research, nevertheless, complies with accepted ethical standards. Potential conflicts of interest were handled openly, and data management protocols respected anonymity.

Informed consent

Before engaging in the study, participants were informed about the objectives of the study by the interviewer. Furthermore, they were assured that any data they contributed would remain confidential and exclusively used only for the study. Transparency was emphasized in conveying that the study’s results and findings would be disseminated in a published format. As a critical component of ethical research practice, participants were requested to give their informed consent prior to their active involvement in the study.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Saha, B., Atiqul Haq, S.M. & Ahmed, K.J. How does the COVID-19 pandemic influence students’ academic activities? An explorative study in a public university in Bangladesh. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 10 , 602 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02094-y

Download citation

Received : 20 October 2022

Accepted : 06 September 2023

Published : 22 September 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02094-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

COVID-19 has fuelled a global ‘learning poverty’ crisis

The pandemic saw empty classrooms all across the world. Image: REUTERS/Marzio Toniolo

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Joao Pedro Azevedo

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} COVID-19 is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:.

- Before the pandemic, the world was already facing an education crisis.

- Last year, 53% of 10-year-old children in low- and middle-income countries either had failed to learn to read with comprehension or were out of school.

- COVID-19 has exacerbated learning gaps further, taking 1.6 billion students out of school at its peak.

- To mitigate the situation, parents, teachers, students, governments, and development partners must work together to remedy the crisis.

Even before COVID-19 forced a massive closure of schools around the globe, the world was in the middle of a learning crisis that threatened efforts to build human capital—the skills and know-how needed for the jobs of the future. More than half (53 percent) of 10-year-old children in low- and middle-income countries either had failed to learn to read with comprehension or were out of school entirely. This is what we at the World Bank call learning poverty . Recent improvements in Learning Poverty have been extremely slow. If trends of the last 15 years were to be extrapolated, it will take 50 years to halve learning poverty. Last year we proposed a target to cut Learning Poverty by at least half by 2030. This would require doubling or trebling the recent rate of improvement in learning, something difficult but achievable. But now COVID-19 is likely to deepen learning gaps and make this dramatically more difficult.

Have you read?

3 things we can do reverse the ‘covid slide’ in education, this indian state is a model of how to manage education during a pandemic, covid-19 is an opportunity to reset education. here are 4 ways how.

Temporary school closures in more than 180 countries have, at the peak of the pandemic, kept nearly 1.6 billion students out of school ; for about half of those students, school closures are exceeding 7 months. Although most countries have made heroic efforts to put remote and remedial learning strategies in place, learning losses are likely to happen. A recent survey of education officials on government responses to COVID-19 by UNICEF, UNESCO, and the World Bank shows that while countries and regions have responded in various ways, only half of the initiatives are monitoring usage of remote learning (Figure 1, top panel). Moreover, where usage is being monitored, the remote learning is being used by less than half of the student population (Figure 1, bottom panel), and most of those cases are online platforms in high- and middle-income countries.

COVID-19-related school closures are forcing countries even further off track from achieving their learning goals. Students currently in school stand to lose $10 trillion in labor earnings over their working lives. That is almost one-tenth of current global GDP, or half the United States’ annual economic output, or twice the global annual public expenditure on primary and secondary education.

In a recent brief I summarize the findings of three simulation scenarios to gauge potential impacts of the crisis on learning poverty. In the most pessimistic scenario, COVID-related school closures could increase the learning poverty rate in the low- and middle-income countries by 10 percentage points, from 53% to 63%. This 10-percentage-point increase in learning poverty implies that an additional 72 million primary-school-age children could fall into learning poverty , out of a population of 720 million children of primary-school age.