- Mammary Glands

- Fallopian Tubes

- Supporting Ligaments

- Reproductive System

- Gametogenesis

- Placental Development

- Maternal Adaptations

- Menstrual Cycle

- Antenatal Care

- Small for Gestational Age

- Large for Gestational Age

- RBC Isoimmunisation

- Prematurity

- Prolonged Pregnancy

- Multiple Pregnancy

- Miscarriage

- Recurrent Miscarriage

- Ectopic Pregnancy

- Hyperemesis Gravidarum

- Gestational Trophoblastic Disease

- Breech Presentation

- Abnormal lie, Malpresentation and Malposition

- Oligohydramnios

- Polyhydramnios

- Placenta Praevia

- Placental Abruption

- Pre-Eclampsia

- Gestational Diabetes

- Headaches in Pregnancy

- Haematological

- Obstetric Cholestasis

- Thyroid Disease in Pregnancy

- Epilepsy in Pregnancy

- Induction of Labour

- Operative Vaginal Delivery

- Prelabour Rupture of Membranes

- Caesarean Section

- Shoulder Dystocia

- Cord Prolapse

- Uterine Rupture

- Amniotic Fluid Embolism

- Primary PPH

- Secondary PPH

- Psychiatric Disease

- Postpartum Contraception

- Breastfeeding Problems

- Primary Dysmenorrhoea

- Amenorrhoea and Oligomenorrhoea

- Heavy Menstrual Bleeding

- Endometriosis

- Endometrial Cancer

- Adenomyosis

- Cervical Polyps

- Cervical Ectropion

- Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia + Cervical Screening

- Cervical Cancer

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS)

- Ovarian Cysts & Tumours

- Urinary Incontinence

- Genitourinary Prolapses

- Bartholin's Cyst

- Lichen Sclerosus

- Vulval Carcinoma

- Introduction to Infertility

- Female Factor Infertility

- Male Factor Infertility

- Female Genital Mutilation

- Barrier Contraception

- Combined Hormonal

- Progesterone Only Hormonal

- Intrauterine System & Device

- Emergency Contraception

- Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

- Genital Warts

- Genital Herpes

- Trichomonas Vaginalis

- Bacterial Vaginosis

- Vulvovaginal Candidiasis

- Obstetric History

- Gynaecological History

- Sexual History

- Obstetric Examination

- Speculum Examination

- Bimanual Examination

- Amniocentesis

- Chorionic Villus Sampling

- Hysterectomy

- Endometrial Ablation

- Tension-Free Vaginal Tape

- Contraceptive Implant

- Fitting an IUS or IUD

Abnormal Fetal lie, Malpresentation and Malposition

Original Author(s): Anna Mcclune Last updated: 1st December 2018 Revisions: 12

- 1 Definitions

- 2 Risk Factors

- 3.2 Presentation

- 3.3 Position

- 4 Investigations

- 5.1 Abnormal Fetal Lie

- 5.2 Malpresentation

- 5.3 Malposition

The lie, presentation and position of a fetus are important during labour and delivery.

In this article, we will look at the risk factors, examination and management of abnormal fetal lie, malpresentation and malposition.

Definitions

- Longitudinal, transverse or oblique

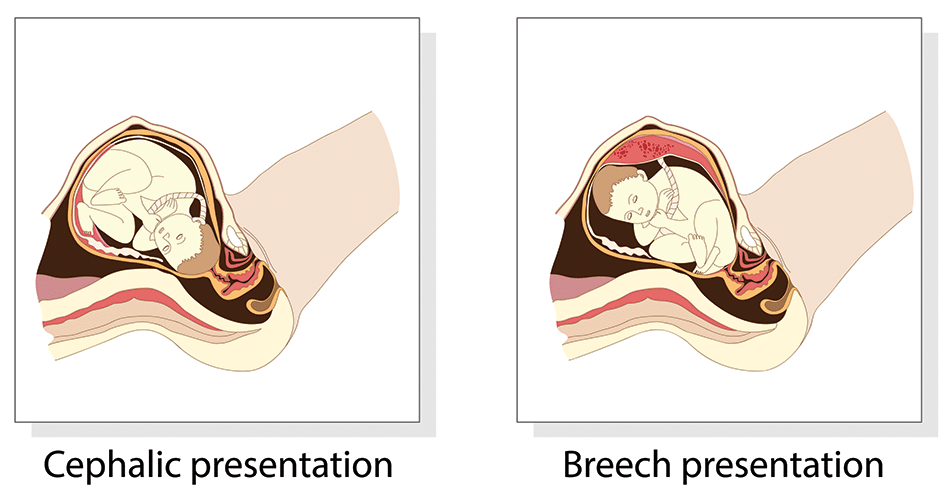

- Cephalic vertex presentation is the most common and is considered the safest

- Other presentations include breech, shoulder, face and brow

- Usually the fetal head engages in the occipito-anterior position (the fetal occiput facing anteriorly) – this is ideal for birth

- Other positions include occipito-posterior and occipito-transverse.

Note: Breech presentation is the most common malpresentation, and is covered in detail here .

Fig 1 – The two most common fetal presentations: cephalic and breech.

Risk Factors

The risk factors for abnormal fetal lie, malpresentation and malposition include:

- Multiple pregnancy

- Uterine abnormalities (e.g fibroids, partial septate uterus)

- Fetal abnormalities

- Placenta praevia

- Primiparity

Identifying Fetal Lie, Presentation and Position

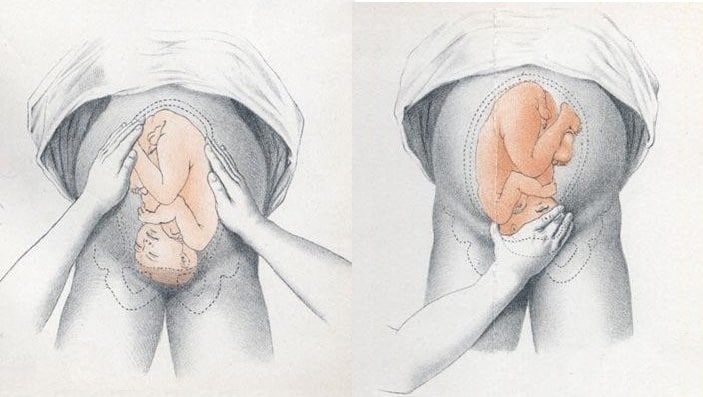

The fetal lie and presentation can usually be identified via abdominal examination. The fetal position is ascertained by vaginal examination.

For more information on the obstetric examination, see here .

- Face the patient’s head

- Place your hands on either side of the uterus and gently apply pressure; one side will feel fuller and firmer – this is the back, and fetal limbs may feel ‘knobbly’ on the opposite side

Presentation

- Palpate the lower uterus (above the symphysis pubis) with the fingers of both hands; the head feels hard and round (cephalic) and the bottom feels soft and triangular (breech)

- You may be able to gently push the fetal head from side to side

The fetal lie and presentation may not be possible to identify if the mother has a high BMI, if she has not emptied her bladder, if the fetus is small or if there is polyhydramnios .

During labour, vaginal examination is used to assess the position of the fetal head (in a cephalic vertex presentation). The landmarks of the fetal head, including the anterior and posterior fontanelles, indicate the position.

Fig 2 – Assessing fetal lie and presentation.

Investigations

Any suspected abnormal fetal lie or malpresentation should be confirmed by an ultrasound scan . This could also demonstrate predisposing uterine or fetal abnormalities.

Abnormal Fetal Lie

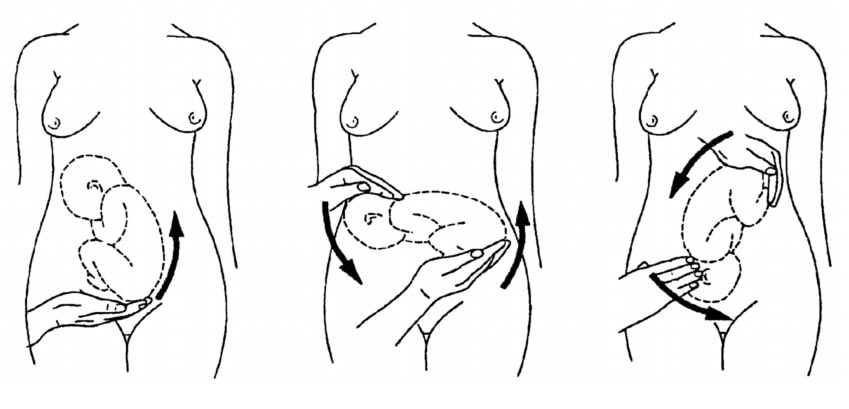

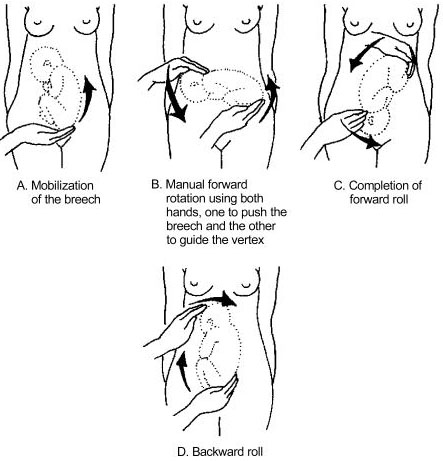

If the fetal lie is abnormal, an external cephalic version (ECV) can be attempted – ideally between 36 and 38 weeks gestation.

ECV is the manipulation of the fetus to a cephalic presentation through the maternal abdomen.

It has an approximate success rate of 50% in primiparous women and 60% in multiparous women. Only 8% of breech presentations will spontaneously revert to cephalic in primiparous women over 36 weeks gestation.

Complications of ECV are rare but include fetal distress , premature rupture of membranes, antepartum haemorrhage (APH) and placental abruption. The risk of an emergency caesarean section (C-section) within 24 hours is around 1 in 200.

ECV is contraindicated in women with a recent APH, ruptured membranes, uterine abnormalities or a previous C-section .

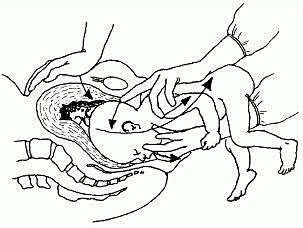

Fig 3 – External cephalic version.

Malpresentation

The management of malpresentation is dependent on the presentation.

- Breech – attempt ECV before labour, vaginal breech delivery or C-section

- Brow – a C-section is necessary

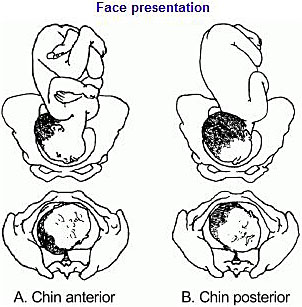

- If the chin is anterior (mento-anterior) a normal labour is possible; however, it is likely to be prolonged and there is an increased risk of a C-section being required

- If the chin is posterior (mento-posterior) then a C-section is necessary

- Shoulder – a C-section is necessary

Malposition

90% of malpositions spontaneously rotate to occipito-anterior as labour progresses. If the fetal head does not rotate, rotation and operative vaginal delivery can be attempted. Alternatively a C-section can be performed.

- Usually the fetal head engages in the occipito-anterior position (the fetal occiput facing anteriorly) - this is ideal for birth

If the fetal lie is abnormal, an external cephalic version (ECV) can be attempted - ideally between 36 and 38 weeks gestation.

- Breech - attempt ECV before labour, vaginal breech delivery or C-section

Found an error? Is our article missing some key information? Make the changes yourself here!

Once you've finished editing, click 'Submit for Review', and your changes will be reviewed by our team before publishing on the site.

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site and to show you relevant advertising. To find out more, read our privacy policy .

Privacy Overview

Fetal Presentation, Position, and Lie (Including Breech Presentation)

- Key Points |

Abnormal fetal lie or presentation may occur due to fetal size, fetal anomalies, uterine structural abnormalities, multiple gestation, or other factors. Diagnosis is by examination or ultrasonography. Management is with physical maneuvers to reposition the fetus, operative vaginal delivery , or cesarean delivery .

Terms that describe the fetus in relation to the uterus, cervix, and maternal pelvis are

Fetal presentation: Fetal part that overlies the maternal pelvic inlet; vertex (cephalic), face, brow, breech, shoulder, funic (umbilical cord), or compound (more than one part, eg, shoulder and hand)

Fetal position: Relation of the presenting part to an anatomic axis; for transverse presentation, occiput anterior, occiput posterior, occiput transverse

Fetal lie: Relation of the fetus to the long axis of the uterus; longitudinal, oblique, or transverse

Normal fetal lie is longitudinal, normal presentation is vertex, and occiput anterior is the most common position.

Abnormal fetal lie, presentation, or position may occur with

Fetopelvic disproportion (fetus too large for the pelvic inlet)

Fetal congenital anomalies

Uterine structural abnormalities (eg, fibroids, synechiae)

Multiple gestation

Several common types of abnormal lie or presentation are discussed here.

Transverse lie

Fetal position is transverse, with the fetal long axis oblique or perpendicular rather than parallel to the maternal long axis. Transverse lie is often accompanied by shoulder presentation, which requires cesarean delivery.

Breech presentation

There are several types of breech presentation.

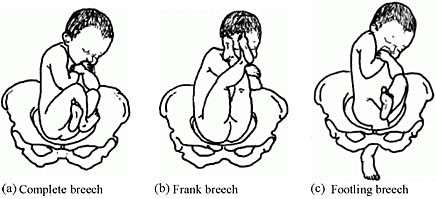

Frank breech: The fetal hips are flexed, and the knees extended (pike position).

Complete breech: The fetus seems to be sitting with hips and knees flexed.

Single or double footling presentation: One or both legs are completely extended and present before the buttocks.

Types of breech presentations

Breech presentation makes delivery difficult ,primarily because the presenting part is a poor dilating wedge. Having a poor dilating wedge can lead to incomplete cervical dilation, because the presenting part is narrower than the head that follows. The head, which is the part with the largest diameter, can then be trapped during delivery.

Additionally, the trapped fetal head can compress the umbilical cord if the fetal umbilicus is visible at the introitus, particularly in primiparas whose pelvic tissues have not been dilated by previous deliveries. Umbilical cord compression may cause fetal hypoxemia.

Predisposing factors for breech presentation include

Preterm labor

Uterine abnormalities

Fetal anomalies

If delivery is vaginal, breech presentation may increase risk of

Umbilical cord prolapse

Birth trauma

Perinatal death

Face or brow presentation

In face presentation, the head is hyperextended, and position is designated by the position of the chin (mentum). When the chin is posterior, the head is less likely to rotate and less likely to deliver vaginally, necessitating cesarean delivery.

Brow presentation usually converts spontaneously to vertex or face presentation.

Occiput posterior position

The most common abnormal position is occiput posterior.

The fetal neck is usually somewhat deflexed; thus, a larger diameter of the head must pass through the pelvis.

Progress may arrest in the second phase of labor. Operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery is often required.

Position and Presentation of the Fetus

If a fetus is in the occiput posterior position, operative vaginal delivery or cesarean delivery is often required.

In breech presentation, the presenting part is a poor dilating wedge, which can cause the head to be trapped during delivery, often compressing the umbilical cord.

For breech presentation, usually do cesarean delivery at 39 weeks or during labor, but external cephalic version is sometimes successful before labor, usually at 37 or 38 weeks.

- Cookie Preferences

Copyright © 2024 Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and its affiliates. All rights reserved.

Variation in fetal presentation

- Report problem with article

- View revision history

Citation, DOI, disclosures and article data

At the time the article was created The Radswiki had no recorded disclosures.

At the time the article was last revised Yuranga Weerakkody had no financial relationships to ineligible companies to disclose.

- Delivery presentations

- Variation in delivary presentation

- Abnormal fetal presentations

There can be many variations in the fetal presentation which is determined by which part of the fetus is projecting towards the internal cervical os . This includes:

cephalic presentation : fetal head presenting towards the internal cervical os, considered normal and occurs in the vast majority of births (~97%); this can have many variations which include

left occipito-anterior (LOA)

left occipito-posterior (LOP)

left occipito-transverse (LOT)

right occipito-anterior (ROA)

right occipito-posterior (ROP)

right occipito-transverse (ROT)

straight occipito-anterior

straight occipito-posterior

breech presentation : fetal rump presenting towards the internal cervical os, this has three main types

frank breech presentation (50-70% of all breech presentation): hips flexed, knees extended (pike position)

complete breech presentation (5-10%): hips flexed, knees flexed (cannonball position)

footling presentation or incomplete (10-30%): one or both hips extended, foot presenting

other, e.g one leg flexed and one leg extended

shoulder presentation

cord presentation : umbilical cord presenting towards the internal cervical os

- 1. Fox AJ, Chapman MG. Longitudinal ultrasound assessment of fetal presentation: a review of 1010 consecutive cases. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;46 (4): 341-4. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2006.00603.x - Pubmed citation

- 2. Merz E, Bahlmann F. Ultrasound in obstetrics and gynecology. Thieme Medical Publishers. (2005) ISBN:1588901475. Read it at Google Books - Find it at Amazon

Incoming Links

- Obstetric curriculum

- Cord presentation

- Polyhydramnios

- Footling presentation

- Normal obstetrics scan (third trimester singleton)

Promoted articles (advertising)

ADVERTISEMENT: Supporters see fewer/no ads

By Section:

- Artificial Intelligence

- Classifications

- Imaging Technology

- Interventional Radiology

- Radiography

- Central Nervous System

- Gastrointestinal

- Gynaecology

- Haematology

- Head & Neck

- Hepatobiliary

- Interventional

- Musculoskeletal

- Paediatrics

- Not Applicable

Radiopaedia.org

- Feature Sponsor

- Expert advisers

Fetal Presentation, Position, and Lie (Including Breech Presentation)

- Variations in Fetal Position and Presentation |

During pregnancy, the fetus can be positioned in many different ways inside the mother's uterus. The fetus may be head up or down or facing the mother's back or front. At first, the fetus can move around easily or shift position as the mother moves. Toward the end of the pregnancy the fetus is larger, has less room to move, and stays in one position. How the fetus is positioned has an important effect on delivery and, for certain positions, a cesarean delivery is necessary. There are medical terms that describe precisely how the fetus is positioned, and identifying the fetal position helps doctors to anticipate potential difficulties during labor and delivery.

Presentation refers to the part of the fetus’s body that leads the way out through the birth canal (called the presenting part). Usually, the head leads the way, but sometimes the buttocks (breech presentation), shoulder, or face leads the way.

Position refers to whether the fetus is facing backward (occiput anterior) or forward (occiput posterior). The occiput is a bone at the back of the baby's head. Therefore, facing backward is called occiput anterior (facing the mother’s back and facing down when the mother lies on her back). Facing forward is called occiput posterior (facing toward the mother's pubic bone and facing up when the mother lies on her back).

Lie refers to the angle of the fetus in relation to the mother and the uterus. Up-and-down (with the baby's spine parallel to mother's spine, called longitudinal) is normal, but sometimes the lie is sideways (transverse) or at an angle (oblique).

For these aspects of fetal positioning, the combination that is the most common, safest, and easiest for the mother to deliver is the following:

Head first (called vertex or cephalic presentation)

Facing backward (occiput anterior position)

Spine parallel to mother's spine (longitudinal lie)

Neck bent forward with chin tucked

Arms folded across the chest

If the fetus is in a different position, lie, or presentation, labor may be more difficult, and a normal vaginal delivery may not be possible.

Variations in fetal presentation, position, or lie may occur when

The fetus is too large for the mother's pelvis (fetopelvic disproportion).

The uterus is abnormally shaped or contains growths such as fibroids .

The fetus has a birth defect .

There is more than one fetus (multiple gestation).

Position and Presentation of the Fetus

Variations in fetal position and presentation.

Some variations in position and presentation that make delivery difficult occur frequently.

Occiput posterior position

In occiput posterior position (sometimes called sunny-side up), the fetus is head first (vertex presentation) but is facing forward (toward the mother's pubic bone—that is, facing up when the mother lies on her back). This is a very common position that is not abnormal, but it makes delivery more difficult than when the fetus is in the occiput anterior position (facing toward the mother's spine—that is facing down when the mother lies on her back).

When a fetus faces up, the neck is often straightened rather than bent,which requires more room for the head to pass through the birth canal. Delivery assisted by a vacuum device or forceps or cesarean delivery may be necessary.

Breech presentation

In breech presentation, the baby's buttocks or sometimes the feet are positioned to deliver first (before the head).

When delivered vaginally, babies that present buttocks first are more at risk of injury or even death than those that present head first.

The reason for the risks to babies in breech presentation is that the baby's hips and buttocks are not as wide as the head. Therefore, when the hips and buttocks pass through the cervix first, the passageway may not be wide enough for the head to pass through. In addition, when the head follows the buttocks, the neck may be bent slightly backwards. The neck being bent backward increases the width required for delivery as compared to when the head is angled forward with the chin tucked, which is the position that is easiest for delivery. Thus, the baby’s body may be delivered and then the head may get caught and not be able to pass through the birth canal. When the baby’s head is caught, this puts pressure on the umbilical cord in the birth canal, so that very little oxygen can reach the baby. Brain damage due to lack of oxygen is more common among breech babies than among those presenting head first.

In a first delivery, these problems may occur more frequently because a woman’s tissues have not been stretched by previous deliveries. Because of risk of injury or even death to the baby, cesarean delivery is preferred when the fetus is in breech presentation, unless the doctor is very experienced with and skilled at delivering breech babies or there is not an adequate facility or equipment to safely perform a cesarean delivery.

Breech presentation is more likely to occur in the following circumstances:

Labor starts too soon (preterm labor).

The uterus is abnormally shaped or contains abnormal growths such as fibroids .

Other presentations

In face presentation, the baby's neck arches back so that the face presents first rather than the top of the head.

In brow presentation, the neck is moderately arched so that the brow presents first.

Usually, fetuses do not stay in a face or brow presentation. These presentations often change to a vertex (top of the head) presentation before or during labor. If they do not, a cesarean delivery is usually recommended.

In transverse lie, the fetus lies horizontally across the birth canal and presents shoulder first. A cesarean delivery is done, unless the fetus is the second in a set of twins. In such a case, the fetus may be turned to be delivered through the vagina.

- Cookie Preferences

Copyright © 2024 Merck & Co., Inc., Rahway, NJ, USA and its affiliates. All rights reserved.

Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

● The curvature of the fetal spine is oriented downward (also called "back down" or dorsoinferior), and the fetal shoulder presents at the cervix ( figure 1 ).

● The curvature of the fetal spine is oriented upward (also called "back up" or dorsosuperior), and the fetal small parts and umbilical cord present at the cervix.

(Note: Lie refers to the long axis of the fetus relative to the longitudinal axis of the uterus; the long axis of the fetus can be transverse to, oblique to, or parallel to [longitudinal lie] the longitudinal axis of the uterus. Presentation refers to the fetal part that directly overlies the pelvic inlet; it is usually cephalic [head] or breech [buttocks] but can be a shoulder, compound [eg, head and hand], or funic [umbilical cord]. Position is the relationship of a nominated site of the presenting part to a denominating location on the maternal pelvis [eg, right occiput anterior].)

An expert resource for medical professionals Provided FREE as a service to women’s health

The Global Library of Women’s Medicine EXPERT – RELIABLE - FREE Over 20,000 resources for health professionals

The Alliance for Global Women’s Medicine A worldwide fellowship of health professionals working together to promote, advocate for and enhance the Welfare of Women everywhere

An Educational Platform for FIGO

The Global Library of Women’s Medicine Clinical guidance and resourses

A vast range of expert online resources. A FREE and entirely CHARITABLE site to support women’s healthcare professionals

The Global Academy of Women’s Medicine Teaching, research and Diplomates Association

- Expert clinical guidance

- Safer motherhood

- Skills videos

- Clinical films

- Special textbooks

- Ambassadors

- Can you help us?

- Introduction

- Definitions

- Complications

- External Cephalic Version

- Management of Labor And Delivery

- Cesarean Delivery

- Perinatal Outcome

- Practice Recommendations

- Study Assessment – Optional

- Your Feedback

This chapter should be cited as follows: Okemo J, Gulavi E, et al , Glob. libr. women's med ., ISSN: 1756-2228; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.414593

The Continuous Textbook of Women’s Medicine Series – Obstetrics Module

Common obstetric conditions

Volume Editor: Professor Sikolia Wanyonyi , Aga Khan University Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya

Abnormal Lie/Presentation

First published: February 2021

Study Assessment Option

By completing 4 multiple-choice questions (randomly selected) after studying this chapter readers can qualify for Continuing Professional Development awards from FIGO plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM See end of chapter for details

INTRODUCTION

The mechanism of labor and delivery, as well as the safety and efficacy, is determined by the specifics of the fetal and maternal pelvic relationship at the onset of labor. Normal labor occurs when regular and painful contractions cause progressive cervical dilatation and effacement, accompanied by descent and expulsion of the fetus. Abnormal labor involves any pattern deviating from that observed in the majority of women who have a spontaneous vaginal delivery and includes:

- Protraction disorders (slower than normal progress);

- Arrest disorders (complete cessation of progress).

Among the causes of abnormal labor is the disproportion between the presenting part of the fetus and the maternal pelvis, which rather than being a true disparity between fetal size and maternal pelvic dimensions, is usually due to a malposition or malpresentation of the fetus.

This chapter reviews how to define, diagnose, and manage the clinical impact of abnormalities of fetal lie and malpresentation with the most commonly occurring being the breech-presenting fetus.

DEFINITIONS

At the onset of labor, the position of the fetus in relation to the birth canal is critical to the route of delivery and, thus, should be determined early. Important relationships include fetal lie, presentation, attitude, and position .

Fetal lie describes the relationship of the fetal long axis to that of the mother. In more than 99% of labors at term, the fetal lie is longitudinal . A transverse lie is less frequent when the fetal and maternal axes may cross at a 90 ° angle, and predisposing factors include multiparity, placenta previa, hydramnios, and uterine anomalies. Occasionally, the fetal and maternal axes may cross at a 45 ° angle, forming an oblique lie .

Fetal presentation

The presenting part is the portion of the fetal body that is either foremost within the birth canal or in closest proximity to it. Thus, in longitudinal lie, the presenting part is either the fetal head or the breech, creating cephalic and breech presentations , respectively. The shoulder is the presenting part when the fetus lies with the long axis transversely.

Commonly the baby lies longitudinally with cephalic presentation. However, in some instances, a fetus may be in breech where the fetal buttocks are the presenting part. Breech fetuses are also referred to as malpresentations. Fetuses that are in a transverse lie may present the fetal back (or shoulders, as in the acromial presentation), small parts (arms and legs), or the umbilical cord (as in a funic presentation) to the pelvic inlet. When the fetal long axis is at an angle to the bony inlet, and no palpable fetal part generally is presenting, the fetus is likely in oblique lie. This lie usually is transitory and occurs during fetal conversion between other lies during labor.

The point of direction is the most dependent portion of the presenting part. In cephalic presentation in a well-flexed fetus, the occiput is the point of direction.

The fetal position refers to the location of the point of direction with reference to the four quadrants of the maternal outlet as viewed by the examiner. Thus, position may be right or left as well as anterior or posterior.

Unstable lie

Refers to the frequent changing of fetal lie and presentation in late pregnancy (usually refers to pregnancies >37 weeks).

Fetal position

Fetal position refers to the relationship of an arbitrarily chosen portion of the fetal presenting part to the right or left side of the birth canal. With each presentation there may be two positions – right or left. The fetal occiput, chin (mentum) and sacrum are the determining points in vertex, face, and breech presentations. Thus:

- left and right occipital presentations

- left and right mental presentations

- left and right sacral presentations.

Fetal attitude

The fetus instinctively forms an ovoid mass that corresponds to the shape of the uterine cavity towards the third trimester, a characteristic posture described as attitude or habitus. The fetus becomes folded upon itself to create a convex back, the head is flexed, and the chin is almost in contact with the chest. The thighs are flexed over the abdomen and the legs are bent at the knees. The arms are usually parallel to the sides or lie across the chest while the umbilical cord fills the space between the extremities. This posture is as a result of fetal growth and accommodation to the uterine cavity. It is possible that the fetal head can become progressively extended from the vertex to face presentation resulting in a change of fetal attitude from convex (flexed) to concave (extended) contour of the vertebral column.

The categories of frank, complete, and incomplete breech presentations differ in their varying relations between the lower extremities and buttocks (Figure 1). With a frank breech, lower extremities are flexed at the hips and extended at the knees, and thus the feet lie close to the head. With a complete breech, both hips are flexed, and one or both knees are also flexed. With an incomplete breech, one or both hips are extended. As a result, one or both feet or knees lie below the breech, such that a foot or knee is lowermost in the birth canal. A footling breech is an incomplete breech with one or both feet below the breech.

Types of breech presentation. Reproduced from WHO 2006, 1 with permission.

The relative incidence of differing fetal and pelvic relations varies with diagnostic and clinical approaches to care.

About 1 in 25 fetuses are breech at the onset of labor and about 1 in 100 are transverse or oblique, also referred to as non-axial. 2

With increasing gestational age, the prevalence of breech presentation decreases. In early pregnancy the fetus is highly mobile within a relatively large volume of amniotic fluid, therefore it is a common finding. The incidence of breech presentation is 20–25% of fetuses at <28 weeks, but only 7–16% at 32 weeks, and only 3–4% at term. 2 , 3

Face and brow presentation are uncommon. Their prevalence compared with other types of malpresentations are shown below. 4

- Occiput posterior – 1/19 deliveries;

- Breech – 1/33 deliveries;

- Face – 1/600–1/800 deliveries;

- Brow – 1/500–1/4000 deliveries;

- Transverse lie – 1/833 deliveries;

- Compound – 1/1500 deliveries.

Transverse lie is often unstable and fetuses in this lie early in pregnancy later convert to a cephalic or breech presentation.

The fetus has a relatively larger head than body during most of the late second and early third trimester, it therefore tends to spend much of its time in breech presentation or in a non-axial lie as it rotates back and forth between cephalic and breech presentations. The relatively large volume of amniotic fluid present facilitates this dynamic presentation.

Abnormal fetal lie is frequently seen in multifetal gestation, especially with the second twin. In women of grand parity, in whom relaxation of the abdominal and uterine musculature tends to occur, a transverse lie may be encountered. Prematurity and macrosomia are also predisposing factors. Distortion of the uterine cavity shape, such as that seen with leiomyomas, prior uterine surgery, or developmental anomalies (Mullerian fusion defects), predisposes to both abnormalities in fetal lie and malpresentations. The location of the placenta also plays a contributing role with fundal and cornual implantation being seen more frequently in breech presentation. Placenta previa is a well-described affiliate for both transverse lie and breech presentation.

Fetuses with congenital anomalies also present with abnormalities in either presentation or lie. It is possibly as a cause (i.e. fitting the uterine cavity optimally) or effect (the fetus with a neuromuscular condition that prevents the normal turning mechanism). The finding of an abnormal lie or malpresentation requires a thorough search for fetal abnormalities. Such abnormalities could include chromosomal (autosomal trisomy) and structural abnormalities (hydrocephalus), as well as syndromes of multiple effects (fetal alcohol syndrome).

In most cases, breech presentation appears to be as a chance occurrence; however, up to 15% may be owing to fetal, maternal, or placental abnormalities. It is commonly thought that a fetus with normal anatomy, activity, amniotic fluid volume, and placental location adopts the cephalic presentation near term because this position is the best fit for the intrauterine space, but if any of these variables is abnormal, then breech presentation is more likely.

Factors associated with breech presentation are shown in Table 1.

Risk factors for breech presentation.

Spontaneous version may occur at any time before delivery, even after 40 weeks of gestation. A prospective longitudinal study using serial ultrasound examinations reported the likelihood of spontaneous version to cephalic presentation after 36 weeks was 25%. 5

In population-based registries, the frequency of breech presentation in a second pregnancy was approximately 2% if the first pregnancy was not a breech presentation and approximately 9% if the first pregnancy was a breech presentation. After two consecutive pregnancies with breech presentation at delivery, the risk of another breech presentation was approximately 25% and this rose to 40% after three consecutive breech deliveries. 6 , 7

In addition, parents who themselves were delivered at term from breech presentation were twice as likely to have their offspring in breech presentation as parents who were delivered in cephalic presentation. This suggests a possible heritable component to fetal presentation. 8

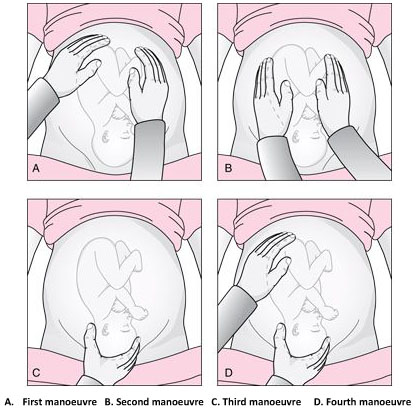

Leopold’s maneuvers

The Leopold’s maneuvers: palpation of fetus in left occiput anterior position. Reproduced from World Health Organization, 2006, 1 with permission.

Abdominal examination can be conducted systematically employing the four maneuvers described by Leopold in 1894. 9 , 10 In obese patients, in polyhydramnios patients or those with anterior placenta, these maneuvers are difficult to perform and interpret.

The first maneuver is to assess the uterine fundus. This allows the identification of fetal lie and determination of which fetal pole, cephalic or podalic – occupies the fundus. In breech presentation, there is a sensation of a large, nodular mass, whereas the head feels hard and round and is more mobile.

The second maneuver is accomplished as the palms are placed on either side of the maternal abdomen, and gentle but deep pressure is exerted. On one side, a hard, resistant structure is felt – the back. On the other, numerous small, irregular, mobile parts are felt – the fetal extremities. By noting whether the back is directed anteriorly, transversely, or posteriorly, fetal orientation can be determined.

The third maneuver aids confirmation of fetal presentation. The thumb and fingers of one hand grasp the lower portion of the maternal abdomen just above the symphysis pubis. If the presenting part is not engaged, a movable mass will be felt, usually the head. The differentiation between head and breech is made as in the first maneuver.

The fourth maneuver helps determine the degree of descent. The examiner faces the mother’s feet, and the fingertips of both hands are positioned on either side of the presenting part. They exert inward pressure and then slide caudad along the axis of the pelvic inlet. In many instances, when the head has descended into the pelvis, the anterior shoulder or the space created by the neck may be differentiated readily from the hard head.

According to Lyndon-Rochelle et al ., 11 experienced clinicians have accurately identified fetal malpresentation using Leopold maneuvers with a high sensitivity 88%, specificity 94%, positive-predictive value 74%, and negative-predictive value 97%.

Vaginal examination

Prelabor diagnosis of fetal presentation is difficult as the presenting part cannot be palpated through a closed cervix. Once labor begins and the cervix dilates, and palpation through vaginal examination is possible. Vertex presentations and their positions are recognized by palpation of the various fetal sutures and fontanels, while face and breech presentations are identified by palpation of facial features or the fetal sacrum and perineum, respectively.

Sonography and radiology

Sonography is the gold standard for identifying fetal presentation. This can be done during antenatal period or intrapartum. In obese women or in women with muscular abdominal walls this is especially important. Compared with digital examinations, sonography for fetal head position determination during second stage labor is more accurate. 12 , 13

COMPLICATIONS

Adverse outcomes in malpresented fetuses are multifactorial. They could be due to either underlying conditions associated with breech presentation (e.g., congenital anomalies, intrauterine growth restriction, preterm birth) or trauma during delivery.

Neonates who were breech in utero are more at risk for mild deformations (e.g., frontal bossing, prominent occiput, upward slant and low-set ears), torticollis, and developmental dysplasia of the hip.

Other obstetric complications include prolapse of the umbilical cord, intrauterine infection, maldevelopment as a result of oligohydramnios, asphyxia, and birth trauma and all are concerns.

Birth trauma especially to the head and cervical spine, is a significant risk to both term and preterm infants who present breech. In cephalic presenting fetuses, the labor process prepares the head for delivery by causing molding which helps the fetus to adapt to the birth canal. Conversely, the after-coming head of the breech fetus must descend and deliver rapidly and without significant change in shape. Therefore, small alterations in the dimensions or shape of the maternal bony pelvis or the attitude of the fetal head may have grave consequences. This process poses greater risk to the preterm infant because of the relative size of the fetal head and body. Trauma to the head is not eliminated by cesarean section; both intracranial and cervical spine trauma may result from entrapment in either the uterine or abdominal incisions.

In resource-limited countries where ultrasound imaging, urgent cesarean delivery, and neonatal intensive care are not readily available, the maternal and perinatal mortality/morbidity associated with transverse lie in labor can be high. Uterine rupture from prolonged labor in a transverse lie is a major reason for maternal/perinatal mortality and morbidity.

EXTERNAL CEPHALIC VERSION

External cephalic version (ECV) is the manual rotation of the fetus from a non-cephalic to a cephalic presentation by manipulation through the maternal abdomen (Figure 3).

External version of breech presentation . Reproduced from WHO 2003 , 14 with permission .

This procedure is usually performed as an elective procedure in women who are not in labor at or near term to improve their chances of having a vaginal cephalic birth. ECV reduces the risk of non-cephalic presentation at birth by approximately 60% (relative risk [RR] 0.42, 95% CI 0.29–0.61) and reduces the risk of cesarean delivery by approximately 40% (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.40–0.82). 7

In a 2008 systematic review of 84 studies including almost 13,000 version attempts at term, the pooled success rate was 58%. 15

A subsequent large series of 2614 ECV attempts over 18 years reported a success rate of 49% and provided more details): 16

- The success rate was 40% in nulliparous women and 64% in parous women.

- After successful ECV, 97% of fetuses remained cephalic at birth, 86% of which were delivered vaginally.

- Spontaneous version to a cephalic presentation occurred after 4.3% of failed attempts, and 2.2% of successfully vertexed cases reverted to breech.

Factors associated with lower ECV success rates include nulliparity, anterior placenta, lateral or cornual placenta, decreased amniotic fluid volume, low birth weight, obesity, posteriorly located fetal spine, frank breech presentation, ruptured membranes.

The following factors should be considered while managing malpresentations: type of malpresentation, gestational age at diagnosis, availability of skilled personnel, institutional resources and protocols and patient factors and preferences.

Breech presentation

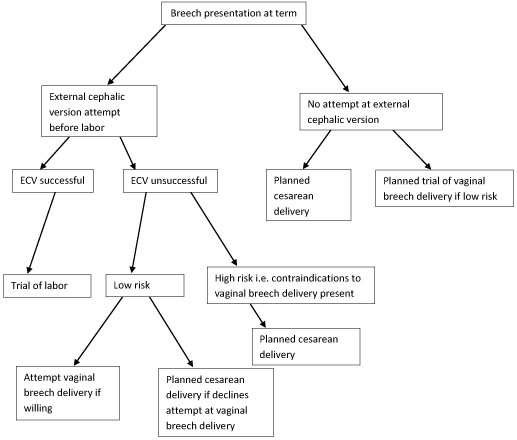

According to a term breech trial, 17 planned cesarean delivery carries a reduced perinatal mortality and early neonatal morbidity for babies with breech presentation at term compared to vaginal breech delivery. When planning a breech vaginal birth, appropriate patient selection and skilled personnel in breech delivery are key in achieving good neonatal outcomes. In appropriately selected patients and skilled personnel in vaginal breech deliveries, perinatal mortality is between 0.8 and 1.7/1000 for planned vaginal breech birth and between 0 and 0.8/1000 for planned cesarean section. 18 , 19 The choice of the route of delivery should therefore be made considering the availability of skilled personnel in conducting breech vaginal delivery; providing competent newborn care; conducting rapid cesarean delivery should need arise and performing ECV if desired; availability of resources for continuous intrapartum fetal heart rate and labor monitoring; patient clinical features, preferences and values; and institutional policies, protocols and resources.

Four approaches to the management of breech presentation are shown in Figure 4: 8

Management of breech presentation. ECV, external cephalic version.

The options available are:

- Attempting external cephalic version (ECV) before labor with a trial of labor if successful and conducting cesarean delivery if unsuccessful.

- Footling or kneeling breech presentation;

- Fetal macrosomia;

- Fetal growth restriction;

- Hyperextended fetal neck in labor;

- Previous cesarean delivery;

- Unavailability of skilled personnel in breech delivery;

- Other contraindications to vaginal delivery like placenta previa, cord prolapse;

- Fetal anomaly that may interfere with vaginal delivery like hydrocephalus.

- Planned cesarean delivery without an attempt at ECV.

- Planned trial of vaginal breech delivery in patients with favorable clinical characteristics for vaginal delivery without an attempt at ECV.

All the four approaches should be discussed in detail with the patient, and in light of all the considerations highlighted above, a safe plan of care agreed upon by both the patient and the clinician in good time.

Transverse and oblique lie

If a diagnosis of transverse/oblique fetal lie is made before onset of labor and there are no contraindications to vaginal birth or ECV, ECV can be attempted at 37 weeks' gestation. If the malpresentation recurs, further attempts at ECV can be made at 38–39 weeks with induction of labor if successful.

ECV can also be attempted in early labor with intact fetal membranes and no contraindications to vaginal birth.

If ECV is declined or is unsuccessful, then planned cesarean section should be arranged after 39 weeks' gestation.

MANAGEMENT OF LABOR AND DELIVERY

Skills to conduct vaginal breech delivery are very important as there are women who may opt for planned vaginal breech birth and even among those who choose planned cesarean delivery, about 10% may go into labor and end up with a vaginal breech delivery. 17 Some implications of cesarean delivery such as need for repeat cesarean deliveries, placental attachment disorders and uterine rupture make vaginal birth more desirable to some individuals. In addition, vaginal birth has advantages such as affordability, quicker recovery, shorter hospital stay, less complications and is more favorable for resource poor settings.

In appropriately selected women, planned vaginal breech birth is not associated with any significant long-term neurological morbidity. Regardless of planned mode of birth, cerebral palsy occurs in approximately 1.5/1,000 breech births, and abnormal neurological development occurs in approximately 3/100. 18 Careful patient selection is very important for good outcomes and it is generally agreed that women who choose to undergo a trial of labor and vaginal breech delivery should be at low risk of complications from vaginal breech delivery. Some contraindications to vaginal breech delivery have been highlighted above.

Women with breech presentation near term, pre- or early-labor ultrasound should be performed to assess type of breech presentation, flexion of the fetal head and fetal growth. If a woman presents in labor and ultrasound is unavailable and has not recently been performed, cesarean section is recommended. Vaginal breech deliveries should only take place in a facility with ability and resources readily available for emergency cesarean delivery should the need arise.

Induction of labor may be considered in carefully selected low-risk women. Augmentation of labor is controversial as poor progress of labor may be a sign of cephalo-pelvic disproportion, however, it may be considered in the event of weak contractions. A cesarean delivery should be performed if there is poor progress of labor despite adequate contractions. Labor analgesia including epidural can be used as needed.

Vaginal breech delivery should be conducted in a facility that is able to carry out continuous electronic fetal heart rate monitoring sufficient personnel to monitor the progress of labor. From the term breech trial, 17 the commonest indications for cesarean section are poor progress of labor (50%) and fetal distress (29%). There is an increased risk of cord compression which causes variable decelerations. Since the fetal head is at the fundus where contractions begin, the incidence of early decelerations arising from head compression is also higher. Due to the irregular contour of the presenting part which presents a high risk of cord prolapse, immediate vaginal examination should be undertaken if membranes rupture to rule out cord prolapse. The frequency of cord prolapse is 1% with frank breech and more than 10% in footling breech. 8

Fetal blood sampling from the buttocks is not recommended. A passive second stage of up to 90 minutes before active pushing is acceptable to allow the breech to descend well into the pelvis. Once active pushing commences, delivery should be accomplished or imminent within 60 minutes. 18

During planned vaginal breech birth, a skilled clinician experienced in vaginal breech birth should supervise the first stage of labor and be present for the active second stage of labor and delivery. Staff required for rapid cesarean section and skilled neonatal resuscitation should be in-hospital during the active second stage of labor.

The optimum maternal position in second stage has not been extensively studied. Episiotomy should be undertaken as needed and only after the fetal anus is visible at the vulva. Breech extraction of the fetus should be avoided. The baby should be allowed to deliver spontaneously with maternal effort only and without any manipulations at least until the level of the umbilicus. A loop of the cord is then pulled to avoid cord compression. After this point, suprapubic pressure can be applied to facilitate flexion of the fetal head and descent.

Delay of arm delivery can be managed by sweeping them across the face and downwards towards in front of the chest or by holding the fetus at the hips or bony pelvis and performing a 180° rotation to deliver the first arm and shoulder and then in the opposite direction so that the other arm and shoulder can be delivered i.e., Lovset’s maneuver (Figure 5).

Lovset’s maneuver. Reproduced from WHO 2006 , 1 with permission .

The fetal head can deliver spontaneously or by the following maneuvers:

- Turning the body to the floor with application of suprapubic pressure to flex the head and neck.

Mauriceau-smellie-veit maneuver . Reproduced from WHO 2003, 14 with permission.

- By use of Piper’s forceps.

- Burns-Marshall maneuver where the baby’s legs and trunk are allowed to hang until the nape of the neck is visible at the mother’s perineum so that its weight exerts gentle downwards and backwards traction to promote flexion of the head. The fetal trunk is then swept in a wide arc over the maternal abdomen by grasping both the feet and maintaining gentle traction; the aftercoming head is slowly born in this process.

If the above methods fail to deliver the fetal head, symphysiotomy and zavanelli maneuver with cesarean section can be attempted. Duhrssen incisions where 1–3 full length incisions are made on an incompletely dilated cervix at the 6, 2 and 10 o’clock positions can be done especially in preterm.

Face presentation

The diagnosis of face presentation is made during vaginal examination where the presenting portion of the fetus is the fetal face between the orbital ridges and the chin. At diagnosis, 60% of all face presentations are mentum anterior, 26% are mentum posterior and 15% are mentum transverse. Since the submentobregmatic (face presentation) and suboccipitobregmatic (vertex presentation) have the same diameter of 9.5 cm, most face presentations can have a successful vaginal birth and not necessarily require cesarean section delivery. 6 The position of a fetus in face presentation helps in guiding the management plan. Over 75% of mentum anterior presentations will have a successful vaginal delivery, whereas it is impossible to have a vaginal birth in mentum posterior position unless it converts spontaneously to mentum anterior position. In mentum posterior position the neck is maximally extended and cannot extend further to deliver beneath the symphysis pubis (Figure 7).

Face presentation. Reproduced from WHO 2003, 14 with permission.

As in breech management, face presentation also requires continuous fetal heart rate monitoring, since abnormalities of fetal heart rate are more common. 5 , 6 In one study , 20 only 14% of pregnancies had normal tracings, 29% developed variable decelerations and 24% had late decelerations. Internal fetal heart rate monitoring with an electrode is not recommended, as it may cause facial and ophthalmic injuries if incorrectly placed. Labor augmentation and cesarean sections are performed as per standard obstetric indications. Vacuum and midforceps delivery should be avoided, but an outlet forceps delivery can be attempted. Attempts to manually convert the face to vertex or to rotate a posterior position to a more favorable anterior mentum position are rarely successful and are associated with high fetal morbidity and mortality, and maternal morbidity, including cord prolapse, uterine rupture, and fetal cervical spine injury with neurological impairment.

Brow presentation

The diagnosis of brow presentation is made during vaginal examination in second stage of labor where the presenting portion of the fetal head is between the orbital ridge and the anterior fontanel.

Brow presentation may be encountered early in labor, but is usually a transitional state and converts to a vertex presentation after the fetal neck flexes. Occasionally, further extension may occur resulting in a face presentation. The majority of brow presentations diagnosed early in labor convert to a more favorable presentation and deliver vaginally. Once brow presentation is confirmed, continuous fetal heart rate monitoring is necessary and labor progress should be monitored closely in order to pick any signs of abnormal labor. Since the brow diameter is large (13.5 cm), persistent brow presentation usually results in prolonged or arrested labor requiring a cesarean delivery. Labor augmentation and instrumental deliveries are therefore not recommended.

CESAREAN DELIVERY

This is an option for women with breech presentation at term to choose cesarean section as their preferred mode of delivery, for those with unsuccessful ECV who do not want to attempt vaginal breech delivery, have contraindications for vaginal breech delivery or in the event that there is no available skilled personnel to safely conduct a vaginal breech delivery. Women should be given enough and accurate information about pros and cons for both planned cesarean section and planned vaginal delivery to help them make an informed decision.

Since the publication of the term breech trial, 17 , 19 there has been a dramatic global shift from selective to planned cesarean delivery for women with breech presentation at term. This study revealed that planned cesarean section carried a reduced perinatal mortality and early neonatal morbidity for babies with breech presentation at term compared to planned vaginal birth (RR 0.33, 95% CI 0.19–0.56). The cesarean delivery rate for breech presentation is now about 70% in European countries, 95% in the United States and within 2 months of the study’s publication, there was a 50–80% increase in rates of cesarean section for breech presentation in The Netherlands.

A planned cesarean delivery should be scheduled at term between 39–41 weeks' gestation to allow maximum time for spontaneous cephalic version and minimize the risk of neonatal respiratory problems. 8 Physical exam and ultrasound should be performed immediately prior to the surgery to confirm the fetal presentation. A detailed consent should be obtained prior to surgery and should include both short- and long-term complications of cesarean section and the alternatives of care that are available. The abdominal and uterine incisions should be sufficiently large to facilitate easy delivery. Thereafter, extraction of the fetus is similar to what is detailed above for vaginal delivery.

Cesarean section for face presentation is indicated for persistent mentum posterior position, mentum transverse and some mentum anterior positions where there is standard indication for cesarean section.

Persistent brow presentation usually necessitates cesarean delivery due to the large presenting diameter that causes arrest or protracted labor.

Transverse/oblique lie

Cesarean section is indicated for patients who present in active labor, in those who decline ECV, following an unsuccessful ECV or in those with contraindications to vaginal birth.

For dorsosuperior (back up) transverse lie, a low transverse incision is made on the uterus and an attempt to grasp the fetal feet with footling breech extraction is made. If this does not succeed, a vertical incision is made to convert the hysterotomy into an inverted T incision.

Dorsoinferior (back down) transverse lie is more difficult to deliver since the fetal feet are hard to grasp. An attempt at intraabdominal version to cephalic or breech presentation can be done if membranes are intact before the uterine incision is made. Another option is to make a vertical uterine incision; however, the disadvantage of this is the risk of uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies.

PERINATAL OUTCOME

Availability of skilled neonatal care at delivery is important for good perinatal outcomes to facilitate resuscitation if needed for all fetal malpresentations. 8 All newborns born from fetal malpresentations require a thorough examination to check for possible injuries resulting from birth or as the cause of the malpresentation.

Neonates who were in face presentation often have facial edema and bruising/ecchymosis from vaginal examinations that usually resolve within 24–48 hours of life and low Apgar scores. Trauma during labor may cause tracheal and laryngeal edema immediately after delivery, which can result in neonatal respiratory distress and difficulties in resuscitative efforts.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

- Diagnosis of unstable lie is made when a varying fetal lie is found on repeated clinical examination in the last month of pregnancy.

- Consider external version to correct lie if not longitudinal.

- Consider ultrasound to exclude mechanical cause.

- Inform woman of need for prompt admission to hospital if membranes rupture or when labor starts.

- If spontaneous rupture of membranes occurs, perform vaginal examination to exclude the presence of a cord or malpresentation.

- If the lie is not longitudinal in labor and cannot be corrected perform cesarean section.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Author(s) statement awaited.

Publishers’ note: We are constantly trying to update and enhance chapters in this Series. So if you have any constructive comments about this chapter please provide them to us by selecting the "Your Feedback" link in the left-hand column.

Online Study Assessment Option All readers who are qualified doctors or allied medical professionals can now automatically receive 2 Continuing Professional Development credits from FIGO plus a Study Completion Certificate from GLOWM for successfully answering 4 multiple choice questions (randomly selected) based on the study of this chapter. Medical students can receive the Study Completion Certificate only.

(To find out more about FIGO’s Continuing Professional Development awards programme CLICK HERE )

I wish to proceed with Study Assessment for this chapter

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience from our website. By using the website or clicking OK we will assume you are happy to receive all cookies from us.

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Volume 99, Issue Suppl 1

- PLD.23 Management of transverse and unstable lie at term

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- R Szaboova ,

- S Sankaran ,

- K Harding ,

- King’s Health Partners, London, UK

Aims To determine current practice and outcomes in women admitted to antenatal ward with diagnosis of transverse or unstable lie.

Background Fetal lie (other than longitudinal) at term may predispose to prolapse of cord or fetal arm and uterine rupture. Local guidelines recommend admission at 37+0 (RCOG guidelines after 37+6 weeks) but give no specific recommendations regarding further management.

Methods A retrospective study was conducted at St Thomas’ Hospital, London from 2009–2012 of all women admitted with unstable/transverse lie. The diagnosis was based on ultrasound examination. Women with placenta praevia and non-singleton deliveries were excluded.

Results Study included 198 cases of unstable/transverse lie. 58% were admitted before 38 weeks. The average length of admission was 7 days (IQR 4–11). There were no cases of cord prolapse or need for an immediate caesarean section from the antenatal ward. 73% of women had a caesarean section at a median gestation of 39+1 weeks (IQR 38+4 – 40+2) although almost half of these (41%) had a cephalic presentation at the time of elective caesarean sections. None of these had an absolute indication for Caesarean section.

Discussion and conclusions The diagnosis of unstable/transverse lie leads to a prolonged inpatient stay and a high Caesarean section rate. From our study and the evidence from the available literature, we recommend delaying admission until at least 38 weeks and awaiting spontaneous version. Future research should focus on the safety of outpatient management with consideration of utilising techniques such as cervical length and fetal fibronectin.

https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2014-306576.324

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

- Getting Pregnant

- Registry Builder

- Baby Products

- Birth Clubs

- See all in Community

- Ovulation Calculator

- How To Get Pregnant

- How To Get Pregnant Fast

- Ovulation Discharge

- Implantation Bleeding

- Ovulation Symptoms

- Pregnancy Symptoms

- Am I Pregnant?

- Pregnancy Tests

- See all in Getting Pregnant

- Due Date Calculator

- Pregnancy Week by Week

- Pregnant Sex

- Weight Gain Tracker

- Signs of Labor

- Morning Sickness

- COVID Vaccine and Pregnancy

- Fetal Weight Chart

- Fetal Development

- Pregnancy Discharge

- Find Out Baby Gender

- Chinese Gender Predictor

- See all in Pregnancy

- Baby Name Generator

- Top Baby Names 2023

- Top Baby Names 2024

- How to Pick a Baby Name

- Most Popular Baby Names

- Baby Names by Letter

- Gender Neutral Names

- Unique Boy Names

- Unique Girl Names

- Top baby names by year

- See all in Baby Names

- Baby Development

- Baby Feeding Guide

- Newborn Sleep

- When Babies Roll Over

- First-Year Baby Costs Calculator

- Postpartum Health

- Baby Poop Chart

- See all in Baby

- Average Weight & Height

- Autism Signs

- Child Growth Chart

- Night Terrors

- Moving from Crib to Bed

- Toddler Feeding Guide

- Potty Training

- Bathing and Grooming

- See all in Toddler

- Height Predictor

- Potty Training: Boys

- Potty training: Girls

- How Much Sleep? (Ages 3+)

- Ready for Preschool?

- Thumb-Sucking

- Gross Motor Skills

- Napping (Ages 2 to 3)

- See all in Child

- Photos: Rashes & Skin Conditions

- Symptom Checker

- Vaccine Scheduler

- Reducing a Fever

- Acetaminophen Dosage Chart

- Constipation in Babies

- Ear Infection Symptoms

- Head Lice 101

- See all in Health

- Second Pregnancy

- Daycare Costs

- Family Finance

- Stay-At-Home Parents

- Breastfeeding Positions

- See all in Family

- Baby Sleep Training

- Preparing For Baby

- My Custom Checklist

- My Registries

- Take the Quiz

- Best Baby Products

- Best Breast Pump

- Best Convertible Car Seat

- Best Infant Car Seat

- Best Baby Bottle

- Best Baby Monitor

- Best Stroller

- Best Diapers

- Best Baby Carrier

- Best Diaper Bag

- Best Highchair

- See all in Baby Products

- Why Pregnant Belly Feels Tight

- Early Signs of Twins

- Teas During Pregnancy

- Baby Head Circumference Chart

- How Many Months Pregnant Am I

- What is a Rainbow Baby

- Braxton Hicks Contractions

- HCG Levels By Week

- When to Take a Pregnancy Test

- Am I Pregnant

- Why is Poop Green

- Can Pregnant Women Eat Shrimp

- Insemination

- UTI During Pregnancy

- Vitamin D Drops

- Best Baby Forumla

- Postpartum Depression

- Low Progesterone During Pregnancy

- Baby Shower

- Baby Shower Games

Breech, posterior, transverse lie: What position is my baby in?

Fetal presentation, or how your baby is situated in your womb at birth, is determined by the body part that's positioned to come out first, and it can affect the way you deliver. At the time of delivery, 97 percent of babies are head-down (cephalic presentation). But there are several other possibilities, including feet or bottom first (breech) as well as sideways (transverse lie) and diagonal (oblique lie).

Fetal presentation and position

During the last trimester of your pregnancy, your provider will check your baby's presentation by feeling your belly to locate the head, bottom, and back. If it's unclear, your provider may do an ultrasound or an internal exam to feel what part of the baby is in your pelvis.

Fetal position refers to whether the baby is facing your spine (anterior position) or facing your belly (posterior position). Fetal position can change often: Your baby may be face up at the beginning of labor and face down at delivery.

Here are the many possibilities for fetal presentation and position in the womb.

Medical illustrations by Jonathan Dimes

Head down, facing down (anterior position)

A baby who is head down and facing your spine is in the anterior position. This is the most common fetal presentation and the easiest position for a vaginal delivery.

This position is also known as "occiput anterior" because the back of your baby's skull (occipital bone) is in the front (anterior) of your pelvis.

Head down, facing up (posterior position)

In the posterior position , your baby is head down and facing your belly. You may also hear it called "sunny-side up" because babies who stay in this position are born facing up. But many babies who are facing up during labor rotate to the easier face down (anterior) position before birth.

Posterior position is formally known as "occiput posterior" because the back of your baby's skull (occipital bone) is in the back (posterior) of your pelvis.

Frank breech

In the frank breech presentation, both the baby's legs are extended so that the feet are up near the face. This is the most common type of breech presentation. Breech babies are difficult to deliver vaginally, so most arrive by c-section .

Some providers will attempt to turn your baby manually to the head down position by applying pressure to your belly. This is called an external cephalic version , and it has a 58 percent success rate for turning breech babies. For more information, see our article on breech birth .

Complete breech

A complete breech is when your baby is bottom down with hips and knees bent in a tuck or cross-legged position. If your baby is in a complete breech, you may feel kicking in your lower abdomen.

Incomplete breech

In an incomplete breech, one of the baby's knees is bent so that the foot is tucked next to the bottom with the other leg extended, positioning that foot closer to the face.

Single footling breech

In the single footling breech presentation, one of the baby's feet is pointed toward your cervix.

Double footling breech

In the double footling breech presentation, both of the baby's feet are pointed toward your cervix.

Transverse lie

In a transverse lie, the baby is lying horizontally in your uterus and may be facing up toward your head or down toward your feet. Babies settle this way less than 1 percent of the time, but it happens more commonly if you're carrying multiples or deliver before your due date.

If your baby stays in a transverse lie until the end of your pregnancy, it can be dangerous for delivery. Your provider will likely schedule a c-section or attempt an external cephalic version , which is highly successful for turning babies in this position.

Oblique lie

In rare cases, your baby may lie diagonally in your uterus, with his rump facing the side of your body at an angle.

Like the transverse lie, this position is more common earlier in pregnancy, and it's likely your provider will intervene if your baby is still in the oblique lie at the end of your third trimester.

Was this article helpful?

What to know if your baby is breech

What's a sunny-side up baby?

What happens to your baby right after birth

How your twins’ fetal positions affect labor and delivery

BabyCenter's editorial team is committed to providing the most helpful and trustworthy pregnancy and parenting information in the world. When creating and updating content, we rely on credible sources: respected health organizations, professional groups of doctors and other experts, and published studies in peer-reviewed journals. We believe you should always know the source of the information you're seeing. Learn more about our editorial and medical review policies .

Ahmad A et al. 2014. Association of fetal position at onset of labor and mode of delivery: A prospective cohort study. Ultrasound in obstetrics & gynecology 43(2):176-182. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23929533 Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Gray CJ and Shanahan MM. 2019. Breech presentation. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448063/ Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Hankins GD. 1990. Transverse lie. American Journal of Perinatology 7(1):66-70. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2131781 Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Medline Plus. 2020. Your baby in the birth canal. U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002060.htm Opens a new window [Accessed September 2021]

Where to go next

Unstable Pelvic Trauma Patient: ED Presentations, Evaluation, and Management

- Jun 3rd, 2023

- Luke Wohlford

- categories: practice updates

Authors: Luke Wohlford, MD (EM Resident Physician, University of Vermont Medical Center) and Joseph Kennedy, MD (EM Attending Physician, University of Vermont Medical Center) // Reviewed by: Summer Chavez, DO, MPH, MPM (EM Attending Physician, University of Houston); Marina Boushra (EM-CCM Attending Physician, Cleveland Clinic Foundation); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

A 35-year-old female with no significant past medical history is brought to the emergency department (ED) by emergency medical services (EMS) from the scene of an apartment fire, where she jumped six stories out of a window to the pavement below. Her initial vital signs are blood pressure 76/54 mmHg, heart rate 128 bpm, temperature 37.0˚ C, respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute, and oxygen saturation 95% on room air. The presenting fingerstick glucose is 108 mg/dL. Her airway is intact, and she has equal bilateral breath sounds. Pulses in all four extremities are weak but intact and symmetric. Her Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) is 14 (3E-5V-6M), and she arrives in a cervical collar placed pre-hospital. A focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) exam is negative, and her secondary survey is notable for a pelvis that is significantly tender to gentle anterior and lateral compression.

How should pelvic fractures be identified in unstable trauma patients?

What is the EM physician’s role in the stabilization of unstable pelvic injuries?

Introduction

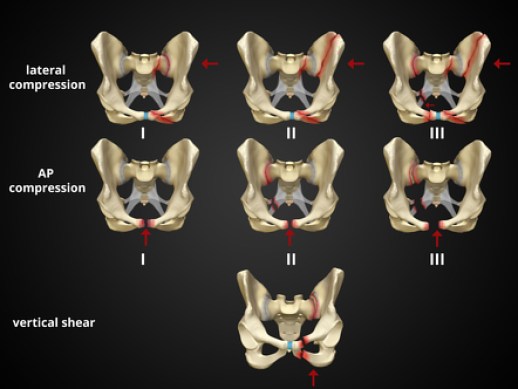

The pelvic ring is made up of the bony ilium, ischium, pubis, and sacrum, which are held together with ligaments. Pelvic fractures can involve disruptions in any of the bony or ligamentous structures of the pelvic ring. Due to the round shape of the pelvic ring, multiple fractures typically occur concurrently. Conceptually, pelvic ring fractures are similar to breaking a hard pretzel. The structures of the ring uniformly experience shearing forces that lead to fractures in at least two discrete locations. While single-bone fractures can occur, they are far less common. Multiple classification systems have been devised to succinctly describe pelvic ring fractures. The Young-Burgess classification is the most common among these. It is generally divided into categories by the suspect traumatic mechanism, including anterior-posterior (AP), lateral compression (LC), and vertical shear fracture. 1 These categories of fractures can be visualized in Figure 1. The AP and LC fractures are further categorized into grades I-III, with grades II and III of each type being mechanically unstable. 2 Vertical shear fractures are also unstable. For a broader overview of pelvic trauma, please review Dr. Lupez’s 2017 article here: http://www.emdocs.net/pelvic-fractures-ed-presentations-management/ .

Figure 1: The Young-Burgess classification of pelvic ring fractures (source: https://radiopaedia.org/cases/37824/studies/39745?lang=us) 3

It is paramount to differentiate the definitions of “hemodynamically unstable” and “mechanically unstable” pelvic fractures. The nuances of fracture patterns and delineating mechanically unstable pelvic fractures from stable ones is less important to the ED. In fact, the World Society of Emergency Surgery (WSES) classification assigns grades I-III depending on their Young-Burgess classification, but any patient hemodynamically unstable from their pelvic fracture is automatically WSES grade IV regardless of their fracture pattern. 4 Patients with pelvic fractures are considered unstable when systolic blood pressure < 90mmHg and heart rate >120bpm, or in those with dyspnea, altered mental status, or skin findings of shock. 4 This is the framework the ED resuscitationist should be operating under, as hemodynamically unstable pelvic trauma patients require a different approach compared to stable patients who will undergo CT, routine pelvic fixation, and definitive surgical repair. Patients with unstable pelvic fractures have high morbidity and mortality. In one series, patients with unstable pelvic fractures had an overall mortality rate of 36%. 5

Initial Evaluation

The key to the initial resuscitation of the unstable pelvic trauma patient is to rapidly identify and treat the most life-threatening pathology. Pelvic ring fractures in adults with healthy bones require high-energy forces, typically motor-vehicle accidents, pedestrian injuries, crush injuries, and falls from height. 6 The clinician must consider traumatic involvement of additional systems, as an estimated 50% of pelvic fractures have concurrent injuries. 6 A primary survey on a trauma patient should reveal deficiencies in airway, breathing, and circulation, which should be rapidly corrected. Identifying and treating the hemodynamically unstable pelvic trauma patient is the focus of the remainder of this article.

If a pelvic binder was placed by EMS, inquire whether this was placed empirically or if mechanical pelvic instability was already elicited. There likely is little benefit to testing pelvic stability with the binder in place even if it was placed empirically, as the binder should not be cleared prior to a pelvic x-ray. Pelvic fractures may not be obvious, especially in the obtunded patient. External clues are not often present, with one study finding only 7.6% of pelvic fractures to be open. 7 Sensitivity for finding a pelvic ring fracture by physical examination approaches 90% but is decreased in patients with GCS < 13. 8

If a pelvic binder was not already placed, gentle anterior compression at the anterior superior iliac spine and lateral compression of the iliac crests can be performed. Pain, movement, or crepitus with these maneuvers are highly concerning for pelvic fractures. Assessment of pelvic stability with lateral and anterior compression should be done a maximum of one time so as to not exacerbate damage from the injury. Limb-length discrepancy is not often apparent in pelvic fractures and would be more suggestive of a femoral fracture or dislocation. Examples of radiographs indicative of pelvic fractures that EM physicians should be familiar with are below in Figures 2, 3, and 4.

Figure 2: Open book pelvic fracture. Note the significant diastasis of the pubic symphysis. Case courtesy of Leonardo Lustoasa and available at https://radiopaedia.org/cases/open-book-pelvic-fracture-4 9

Figure 3: Vertical shear pelvic fracture. Note the widening of the right sacroiliac joint and the pubic symphysis with superior displacement of the right hemipelvis. Case courtesy of Stefan Tigges and available at https://radiopaedia.org/cases/vertical-shear-injury 10

Figure 4: Lateral compression fracture. Note fractures to the left hemipelvis, including fractures of the left superior and inferior pubic rami and left posterior ilium with impaction of the left sacrum. Case courtesy of Stefan Tigges and available at https://radiopaedia.org/cases/lateral-compression-2-pelvic-fracture 11

There is a high rate of concomitant injuries in the pelvis related to these fractures, including bladder rupture, ureteral injury or transection, bowel perforation, rectal injury, and sacral nerve injuries. 12 Patients with pelvic fractures and concerning straddle mechanisms should be thoroughly evaluated for genitourinary injuries. This is less critical in ED management of the unstable pelvic fracture, as the optimal site for identification of rectal or vaginal tears is the operating room.

Resuscitation

The pelvic cavity can contain 4 to 6 liters of blood, so even in an isolated pelvic trauma, multiple units of blood products may be required to achieve hemodynamic stability. 13 Massive transfusion protocols (MTP) are hallmarks of trauma resuscitation, and they are critical to the unstable pelvic fracture patient. Institutional protocols should be utilized, keeping in mind that either whole blood or a 1:1:1 ratio of packed red blood cells, platelets, and fresh frozen plasma are optimal. 14 Given the risk/benefit profile, in the critical and most unstable of pelvic trauma patients tranexamic acid (TXA) 1 g should be considered as adjunctive therapy, followed by infusion, within 3 hours of the injury. Another option is to administer 2 g of TXA without infusion. Data from the CRASH-2 trial suggest that the mortality benefit of TXA exists until 3 hours post-injury and diminishes for every 15-minute delay. 15

If the cause of bleeding is not apparent externally, special attention should be paid to the pelvis, femur, and FAST exam to investigate the areas patients can bleed internally. Unstable patients with positive FAST exams will often go to the operating room expediently depending on the entire clinical picture, so further workup and treatment of pelvic fractures in these scenarios will occur outside of the ED with surgical fixation.