- Contact sales (+234) 08132546417

- Have a questions? [email protected]

- Latest Projects

Project Materials

How to write a good chapter two: literature review.

Click Here to Download Now.

Do You Have New or Fresh Topic? Send Us Your Topic

How to write chapter two of a research pape r.

As is known, within a research paper, there are several types of research and methodologies. One of the most common types used by students is the literature review. In this article, we will be dealing how to write the literature review (Chapter Two) of your research paper.

Although when writing a project, literature review (Chapter Two) seems more straightforward than carrying out experiments or field research, the literature review involves a lot of research and a lot of reading. Also, utmost attention is essential when it comes to developing and referencing the content so that nothing is pointed out as plagiarism.

However, unlike other steps in project writing, it is not necessary to perform the separate theoretical reference part in the review. After all, the work itself will be a theoretical reference, filled with relevant information and views of several authors on the same subject over time.

As it technically has fewer steps and does not need to go to the field or build appraisal projects, the research paper literature review is a great choice for those who have the tightest deadline for delivering the work. But make no mistake, the level of seriousness in research and development itself is as difficult as any other step.

To further facilitate your understanding, we have divided this research methodology into some essential steps and will explain how to do each of them clearly and objectively. Want to know more about it? Read on and check it out!

What is the literature review in a research paper?

To develop a project in any discipline, it is necessary, first, to study everything that other authors have already explored on that subject. This step aims to update the subject for the academic community and to have a basis to support new research. Therefore, it must be done before any other process within the research paper. However, in the literature review (Chapter Two), this step of searching for data and previous work is all the work. That is, you will only develop the theoretical framework.

In general, you will need to choose the topic in question and search for more relevant works and authors that worked around that research idea you want to discuss. As the intention is to make history and update the subject, you will be able to use works from different dates, showing how opinions and views have evolved over time.

Suppose the subject of your research paper is the role of monarchies in 21st-century societies, for example. In that case, you must present a history of how this institution came about, its impact on society, and what roles the institution is currently playing in modern societies. In the end, you can make a more personal conclusion about your vision.

If your topic covered contains a lot of content, you will need to select the most important and relevant and highlight them throughout the work. This is because you will need to reference the entire work. This means that the research paper literature review needs to be filled with citations from other authors. Therefore, it will present references in practically every paragraph.

In order not to make your work uninteresting and repetitive, you should quote differently throughout development. Switching between direct and indirect citations and trying to fit as much content and work as possible will enrich your project and demonstrate to the evaluators how deep you have been in the search.

Within the review, the only part that does not need to be referenced is the conclusion. After all, it will be written as your final and personal view of everything you have read and analyzed.

How to write a literature review?

Here are some practical and easy tips for structuring a quality and compliant research paper literature review!

Introduction

As with any work, the introduction should attract your project readers’ attention and help them understand the basis of the subject that will be worked on. When reading the introduction, you need to be clear to whoever is reading about your research and what it wants to show.

Following the example cited on the theme of monarchies’ roles in the 21st-century societies, the introduction needs to clarify what this type of institution is and why research on it is vital for this area. Also, it would help if you also quoted how the work was developed and the purpose of your literary study.

Basically, you will introduce the subject in such a way that the reader – even without knowing anything about the topic – can read the complete work and grasp the approach, understanding what was done and the meaning of it.

Methodology

Describing the methodology of a literature review is simpler than describing the steps of field research or experiment. In this step, you will need to describe how your research was carried out, where the information was searched, and retrieved.

As you will need to gather a lot of content, searches can be done in books, academic articles, academic publications, old monographs, internet articles, among other reliable sources. The important thing is always to be sure with your supervisor or other teachers about the reliability of each content used. After all, as the entire work is a theoretical reference, choosing unreliable base papers can greatly damage your grade and hinder your approval, putting at risk the quality and integrity of your entire research paper.

Results and conclusion

The results must present clearly and objectively everything that has been observed and collected from studies throughout history on the research’s theme. In this step, you should show the comparisons between authors, like what was the view of the subject before and how it is currently, in an updated way.

You will also be able to show the developments within the theme and the progress of research and discoveries, as well as the conclusions on the issue so far. In the end, you will summarize everything you have read and discovered, and present your final view on the topic.

Also, it is important to demonstrate whether your project objectives have been met and how. The conclusion is the crucial point to convince your reader and examiner of the relevance and importance of all the work you have done for your area or branch, society, or the environment. Therefore, you must present everything clearly and concisely, closing your research paper with a flourish.

In all academic work, bibliographic references are essential. In the academic paper literature review, however, these references will be gathered at the end of the work and throughout the texts.

Citations during the development of the subject must be referenced in accordance with the guideline of your institutions and departments. For each type of reference, there is a rule that depends on the number of words or how you will make it.

Also, in the list of bibliographic references, where you will need to put all the content used, the rules change according to your search source. For internet sources, for example, the way of referencing is different than book sources.

A wrong quote throughout the text or a used work that you forget to put in the references can lead to your project being labeled a plagiarism work, which is a crime and can lead to several consequences. Therefore, studying these standards is essential and determinant for the success of your work’s literature review (Chapter Two).

By adequately studying the rules, dedicating yourself, and putting them into practice, not only will it be easy to develop a successful project, but achieving your dream grade will be closer than you think.

Not What You Were Looking For? Send Us Your Topic

INSTRUCTIONS AFTER PAYMENT

- 1.Your Full name

- 2. Your Active Email Address

- 3. Your Phone Number

- 4. Amount Paid

- 5. Project Topic

- 6. Location you made payment from

» Send the above details to our email; [email protected] or to our support phone number; (+234) 0813 2546 417 . As soon as details are sent and payment is confirmed, your project will be delivered to you within minutes.

Latest Updates

Investment in printing business accountability and profitability, influence of management style on staff performance, leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Advertisements

- Hire A Writer

- Plagiarism Research Clinic

- International Students

- Project Categories

- WHY HIRE A PREMIUM RESEARCHER?

- UPGRADE PLAN

- PROFESSIONAL PLAN

- STANDARD PLAN

- MBA MSC STANDARD PLAN

- MBA MSC PROFESSIONAL PLAN

Project Writers in Nigeria BSc. MSc. PhD

Research Project Writing Website

HOW TO WRITE CHAPTER TWO OF RESEARCH PROJECTS

A practical guide to research writing – chapter two.

Historically, Chapter Two of every academic Research/Project Write up has been Literature Review, and this position has not changed. When preparing your write up for this Chapter, you can title it “Review of Related Literature” or just “Literature Review”.

This is the chapter where you provide detailed explanation of previous researches that has been conducted on your topic of interest. The previous studies that must be selected for this chapter must be academic work/articles published in an internationally reputable journal.

Also, the selected articles must not be more than 10 years old (article publication date to project writing date). For better organization, it has been generally accepted that the arrangement for a good literature review write up follows this order:

2.0 Introduction

2.1 Conceptual Review

2.2 Theoretical Framework

2.3 Empirical review

Summary of Literature/Research Gap

2.0 INTRODUCTION

This serves as the preamble to the chapter alone or preliminary information on the chapter. All the preliminary information that should be provided here should cover just this chapter alone because the project already has a general introduction which is chapter one. It should only reflect the content of this chapter. This is why the introduction for literature review is sometimes optional.

Basically here, you should describe the contents of the chapter in few words

HIRE A PROFESSIONAL PROJECT WRITER

2.1 CONCEPTUAL REVIEW

This section can otherwise be titled “Conceptual Framework”. It must capture all explanations on the concepts that are associated with your research topic in logical order. For example, if your research topic is “A study of the effect of advertisement on firm sales”, your conceptual framework can best follow this order:

2.1 Conceptual Framework

2.1.1 Advertisement

2.1.1.1 Types of Advertisement

2.1.1.2. Advantages of Advertisement

2.1.2 Concept of Firm Sales

2.1.2.1 Factor determining Firm Sales

These concepts must be defined and described from the historical point of view. Topical works and prevailing issues globally, in your continent and nation on the concepts should be presented here. You must be able to provide clear information here that there should be no ambiguity about the variables you are studying.

2.2 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

This can be otherwise titled “Theoretical Review”. This section should contain all previous professional theories and models that have provided explanations on your research topic in the recent past. Yes, related theories and models also falls within the category of past literature for your research write up. Professional theories that are most relevant to your topic should be separately arranged in this section, as seen in the example below:

2.2.1 Jawkwish Theory of Performance

2.2.2 Interstitial Theory of Ranking

2.2.3 Grusse Theory of Social Learning

But the most important thing to note while writing this part is that, apart from making sure that you must do a thorough research and ensure that the most relevant theories for your research topic is selected, your theoretical review must capture some important points which should better reflect in this order for each model:

The proponent of the theory/model, title and year of publication, aim/purpose/structure of the theory, contents and arguments of the theory, findings and conclusions of the theory, criticisms and gaps of the theory, and finally the relevance of the theory to your current research topic.

Best Research Writing eBook

Academic project or thesis or dissertation writing is not an easy academic endeavor. To reach your goal, you must invest time, effort, and a strong desire to succeed. Writing a thesis while also juggling other course work is challenging, but it doesn't have to be an unpleasant process. A dissertation or thesis is one of the most important requirements for any degree, and this book will show you how to create a good research write-up from a high level of abstraction, making your research writing journey much easier. It also includes examples of how and what the contents of each sub-headings should look like for easy research writing. This book will also constitute a step-by-step research writing guide to scholars in all research fields.

2.3 EMPIRICAL REVIEW

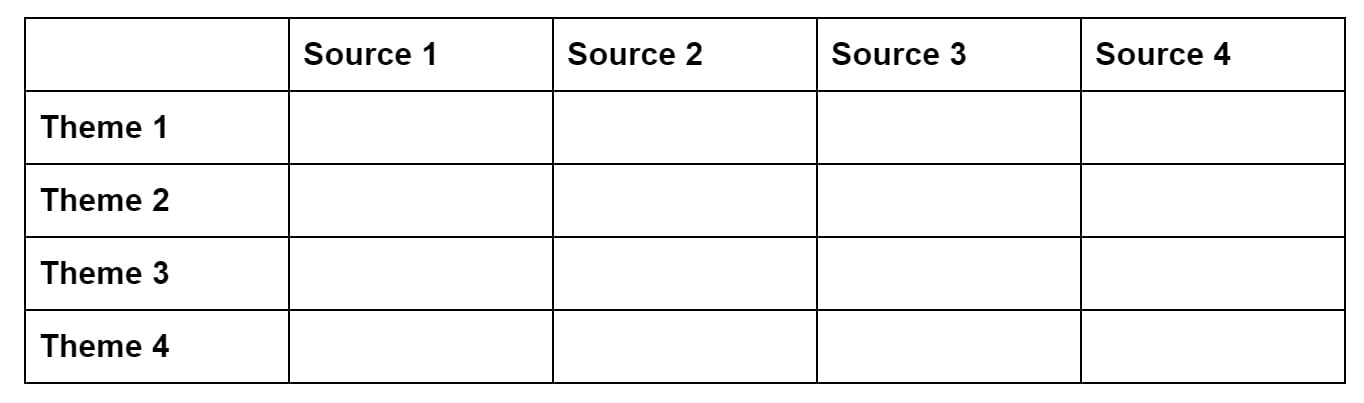

This can be otherwise titled “Empirical Framework”. This is usually described as the critical review of the existing academic works/literature on your research topic. This can be organized or arranged in two different alternative ways when developing your write up:

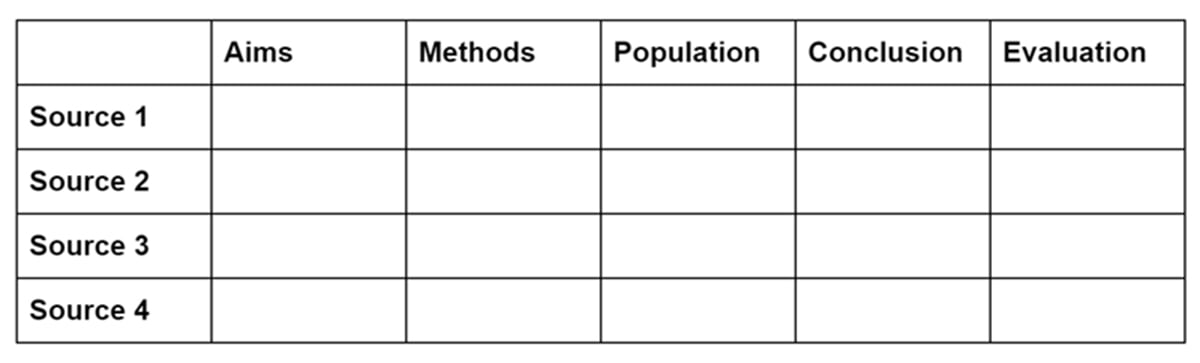

- It can be arranged in a table with heading arranged horizontally in this order: Author name and initials, year and title of publication, aim/objectives, methodology, findings, conclusions, recommendations, research gap. Responses for the above should be provided in spaces provided below in the table for up to 40 articles at least.

- The second option excludes the use of tables but still contains the same information exactly as above for tables. The information is provided in thematic text format with appropriate in-text references. Note that all these points to be included can be directly gotten from the articles except the research gap which requires your critical thinking. Your research gap must identify an important thing(s) the previous research has not done well or not done at all, which your current research intends to do. Although, you should criticize, but constructively while acknowledging areas of perfections and successes of the authors.

Note that every research you critically review must have evident/obvious gaps that your research intends to fill.

SUMMARY OF LITERATURE REVIEW/RESEARCH GAP/GAP ANALYSIS

This is the concluding part of every literature review write up. It provides the summary of the entire content of the whole Chapter. Sometimes, some institutions require that you bring the analysis of all the gaps of the existing literature under review here. Conclusions on the whole existing literature under review should briefly be highlighted in this section.

I trust that this article will help undergraduates and postgraduate researchers in writing a very good Literature Review for your Research/Project/Paper/Thesis, and will also meet the needs of our esteemed readers who has been requesting for a guide on how to write their Chapter Two (Literature Review).

Enjoy, as you develop a good Literature Review for your research!

24 comments

please i want to understand how to write a project. tutorial available?

thanks so now am able to write the chapter two of the research

Thank you for the article,it really guide and educate.

Thank you so much for this vital information which serve as a guide to me in respect to my chapter 2. With so much hope and interest this piece of information will pass across other researchers.

Very helpful, thanks for sharing this for free.

This is fantastic, I commend you for the well job done, this guiedline is so much useful for me, you’ve indeed light up my path to write a good literature review of chapter 2

I Have a doctoral dissertation research and I want to understand the help you can offer for me to move forward. Thanks.

It was indeed helpful. Thanks.

This is helpful

Good it serves a lecture delivered by notable Prof

Very helpful, thanks for be present,

Sir, am confused a bit am writing on the role of social media in creating political awareness and mobilizing political protests (in Nigeria). How my going to do conceptual framework. Thanks

Thanks for educating me better

Thank you so much, the detailed explanation has given me more courage to attain my first class degree, all the way from Gulu Uganda.

Really helpful. Thank you for this.

Sure this page realy guide me on chapter two big thanks i will request more when the need arise

thank you for this article but is this the only option for writing a chapter two for an undergraduate degree project?

Very helpful

Weldone and kudos to you guys

Thanks a lot this has surely helped me in moving ahead in my project

Thanks for this piece of information I really appreciate ✨

Pls how will i see the preamble in my journal or am i going to write it offhand

First of all thanks for the informations provided above. I want to ask is the nature and element of research also included in this chapter

Need proof reading help

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Chat With A professional Writer

Research Methods

Chapter 2 introduction.

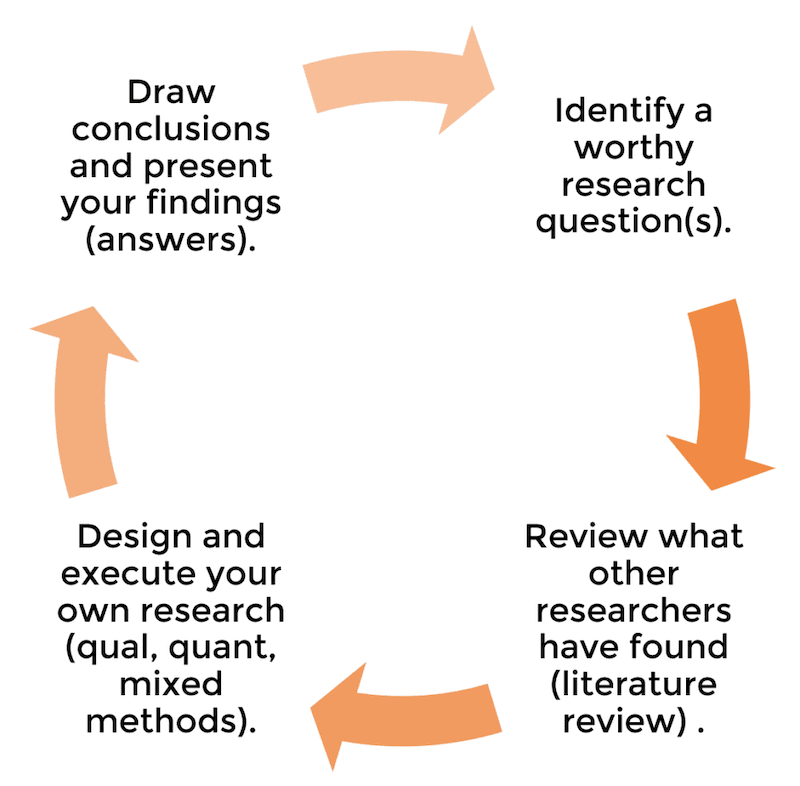

Maybe you have already gained some experience in doing research, for example in your bachelor studies, or as part of your work.

The challenge in conducting academic research at masters level, is that it is multi-faceted.

The types of activities are:

- Finding and reviewing literature on your research topic;

- Designing a research project that will answer your research questions;

- Collecting relevant data from one or more sources;

- Analyzing the data, statistically or otherwise, and

- Writing up and presenting your findings.

Some researchers are strong on some parts but weak on others.

We do not require perfection. But we do require high quality.

Going through all stages of the research project, with the guidance of your supervisor, is a learning process.

The journey is hard at times, but in the end your thesis is considered an academic publication, and we want you to be proud of what you have achieved!

Probably the biggest challenge is, where to begin?

- What will be your topic?

- And once you have selected a topic, what are the questions that you want to answer, and how?

In the first chapter of the book, you will find several views on the nature and scope of business research.

Since a study in business administration derives its relevance from its application to real-life situations, an MBA typically falls in the grey area between applied research and basic research.

The focus of applied research is on finding solutions to problems, and on improving (y)our understanding of existing theories of management.

Applied research that makes use of existing theories, often leads to amendments or refinements of these theories. That is, the applied research feeds back to basic research.

In the early stages of your research, you will feel like you are running around in circles.

You start with an idea for a research topic. Then, after reading literature on the topic, you will revise or refine your idea. And start reading again with a clearer focus ...

A thesis research/project typically consists of two main stages.

The first stage is the research proposal .

Once the research proposal has been approved, you can start with the data collection, analysis and write-up (including conclusions and recommendations).

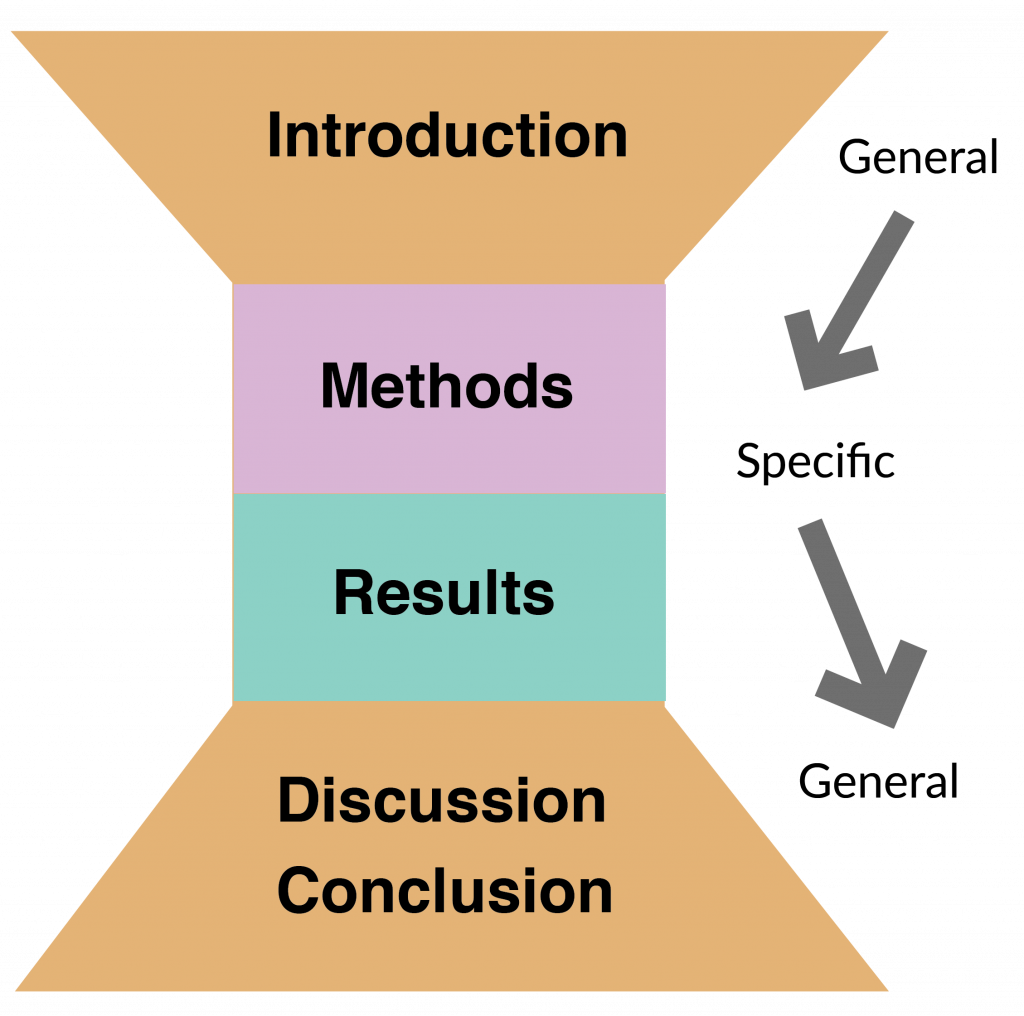

Stage 1, the research proposal consists of he first three chapters of the commonly used five-chapter structure :

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- An introduction to the topic.

- The research questions that you want to answer (and/or hypotheses that you want to test).

- A note on why the research is of academic and/or professional relevance.

- Chapter 2: Literature

- A review of relevant literature on the topic.

- Chapter 3: Methodology

The methodology is at the core of your research. Here, you define how you are going to do the research. What data will be collected, and how?

Your data should allow you to answer your research questions. In the research proposal, you will also provide answers to the questions when and how much . Is it feasible to conduct the research within the given time-frame (say, 3-6 months for a typical master thesis)? And do you have the resources to collect and analyze the data?

In stage 2 you collect and analyze the data, and write the conclusions.

- Chapter 4: Data Analysis and Findings

- Chapter 5: Summary, Conclusions and Recommendations

This video gives a nice overview of the elements of writing a thesis.

How To Write Chapter 2 Of A PhD Thesis Proposal (A Beginner’s Guide)

The second chapter of a PhD thesis proposal in most cases is the literature review. This article provides a practical guide on how to write chapter 2 of a PhD thesis.

Introduction to the chapter

Theoretical review, empirical review, chronological organisation of empirical literature review, thematic organisation of empirical literature review, developing a conceptual framework, research gaps, chapter summary, final thoughts on how to write chapter 2 of a phd thesis proposal.

The format for the literature review chapter is discussed below:

This section is about a paragraph-long and informs the readers on what the chapter will cover.

The theoretical review follows immediately after the introductory section of the chapter.

In this section, the student is expected to review the theories behind his/her topic under investigation. One should discuss who came up with the theory, the main arguments of the theory, and how the theory has been applied to study the problem under investigation.

A given topic may have several theories explaining it. The student should review all those theories but at the end mention the main theory that informs his study while giving justification for the selection of that theory.

Because of the existence of many theories and models developed by other researchers, the student is expected to do some comparative analysis of the theories and models that are applicable to his study.

After discussing the theories and models that inform your study, the student is expected to review empirical studies related to his problem under investigation. Empirical literature refers to original studies that have been done by other studies through data collection and analysis. The conclusions drawn from such studies are based on data rather than theories.

This section requires critical thinking and analysis rather than just stating what the authors did and what they found. The student is expected to critique the studies he is reviewing, while making reference to other similar studies and their findings.

For instance, if two studies on the same topic arrive at contrary conclusions, the student should be able to analyse why the conclusions are different: e.g. the population of study could be different, the methodology used could be different etc.

There are two ways of organising empirical literature: chronological and thematic:

In this method, the empirical literature review is organised by date of publication, starting with the older literature to the most recent literature.

The advantage of using this method is that it shows how the state of knowledge of the problem under investigation has changed over time.

The disadvantage of chronological empirical review is that the flow of discussion is not smooth, because similar studies are discussed separately depending on when they were published.

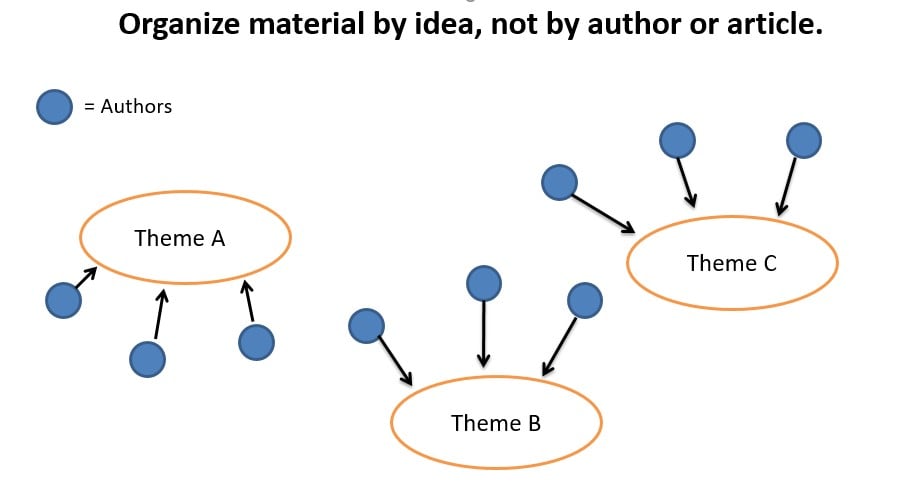

In this method, like studies are discussed together.

The studies are organised based on the variables of the study. Each variable has its own section for discussion. All studies that examined a variable are discussed together, highlighting the consensus amongst the studies, as well as the points of disagreement.

The advantage of this method is that it creates a smooth flow of discussion of the literature. It also makes it easier to identify the research gaps in each variable under investigation.

While the choice between chronological and thematic empirical review varies from one institution to another, the thematic synthesis is most preferred especially for PhD-level programs.

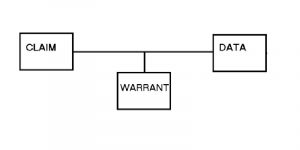

After the theoretical and empirical review, the student is expected to develop his own conceptual framework. A conceptual framework is a diagrammatic representation of the variables of a study and the relationship between those variables.

The conceptual framework is informed by the literature review. Developing a conceptual framework involves three main steps:

- Identify all the variables that will be analysed in your study.

- Specify the relationship between the variables, as informed by the literature review.

- Draw a diagram with the variables and the relationship between them.

The main purpose of conducting literature review is to document what is known and what is not known.

Research gaps are what is not yet known about the topic under investigation.

Your contribution to knowledge will come from addressing what is not yet known.

It is therefore important for PhD students to first review existing literature for their area of study before settling on the final topic.

Additionally, when reviewing literature, the student should review all of the most recent studies to avoid duplicating efforts. Originality is important especially for PhD studies.

There are different types of research gaps:

- Gaps in concepts or variables studied e.g. most studies on maternal health focus on pregnancy and delivery but not on post-partum period. So you conduct a study focusing on the post-partum period.

- Geographical coverage: rural vs. urban or rural vs. urban slums; developed vs. developing countries etc

- Time: past vs. recent

- Demographics: middle class vs. poor communities; males vs. females; educated vs. uneducated etc

- Research design: quantitative vs. qualitative or mixed methods

- Data collection: questionnaires vs. interviews and focus group discussions

- Data analysis techniques: descriptive vs. inferential statistics etc

This section provides a summary of what the chapter is about and highlights the main ideas.

This article provided some guidance on how to write chapter 2 of a PhD thesis proposal as well as the format expected of the chapter by many institutions. The format may vary though and students are advised to refer to the dissertation guidelines of their institutions. Writing the literature review chapter can be the most daunting task of a PhD thesis proposal because it informs chapter 1 of the proposal. For instance, writing the contribution to knowledge section of chapter 1 requires the student to have read and reviewed many articles.

Related post

How To Write Chapter 1 Of A PhD Thesis Proposal (A Practical Guide)

How To Write Chapter 3 Of A PhD Thesis Proposal (A Detailed Guide)

Grace Njeri-Otieno

Grace Njeri-Otieno is a Kenyan, a wife, a mom, and currently a PhD student, among many other balls she juggles. She holds a Bachelors' and Masters' degrees in Economics and has more than 7 years' experience with an INGO. She was inspired to start this site so as to share the lessons learned throughout her PhD journey with other PhD students. Her vision for this site is "to become a go-to resource center for PhD students in all their spheres of learning."

Recent Content

SPSS Tutorial #12: Partial Correlation Analysis in SPSS

Partial correlation is almost similar to Pearson product-moment correlation only that it accounts for the influence of another variable, which is thought to be correlated with the two variables of...

SPSS Tutorial #11: Correlation Analysis in SPSS

In this post, I discuss what correlation is, the two most common types of correlation statistics used (Pearson and Spearman), and how to conduct correlation analysis in SPSS. What is correlation...

- Advertise with us

- Wednesday, April 24, 2024

Most Widely Read Newspaper

PunchNG Menu:

- Special Features

- Sex & Relationship

ID) . '?utm_source=news-flash&utm_medium=web"> Download Punch Lite App

Project Chapter Two: Literature Review and Steps to Writing Empirical Review

Kindly share this story:

- Conceptual review

- Theoretical review,

- Empirical review or review of empirical works of literature/studies, and lastly

- Conclusion or Summary of the literature reviewed.

- Decide on a topic

- Highlight the studies/literature that you will review in the empirical review

- Analyze the works of literature separately.

- Summarize the literature in table or concept map format.

- Synthesize the literature and then proceed to write your empirical review.

All rights reserved. This material, and other digital content on this website, may not be reproduced, published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed in whole or in part without prior express written permission from PUNCH.

Contact: [email protected]

Stay informed and ahead of the curve! Follow The Punch Newspaper on WhatsApp for real-time updates, breaking news, and exclusive content. Don't miss a headline – join now!

Tired of expensive crypto trading fees? There's a better way! Get started with KWIQ and trade crypto for only 1,250naira per dollar. Download the app now!

Latest News

Family holds 41-day prayer for late olubadan, edo cultists kill rival in daughter's presence, abandon getaway car, faan reopens lagos airport runway after dana air incident, nollywood veteran actor, zulu adigwe is dead, finance ministry recovered n57bn mdas’ debts - director.

Bullying: Abuja school shut, victim may sue

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, conse adipiscing elit.

Chapter 2. Research Design

Getting started.

When I teach undergraduates qualitative research methods, the final product of the course is a “research proposal” that incorporates all they have learned and enlists the knowledge they have learned about qualitative research methods in an original design that addresses a particular research question. I highly recommend you think about designing your own research study as you progress through this textbook. Even if you don’t have a study in mind yet, it can be a helpful exercise as you progress through the course. But how to start? How can one design a research study before they even know what research looks like? This chapter will serve as a brief overview of the research design process to orient you to what will be coming in later chapters. Think of it as a “skeleton” of what you will read in more detail in later chapters. Ideally, you will read this chapter both now (in sequence) and later during your reading of the remainder of the text. Do not worry if you have questions the first time you read this chapter. Many things will become clearer as the text advances and as you gain a deeper understanding of all the components of good qualitative research. This is just a preliminary map to get you on the right road.

Research Design Steps

Before you even get started, you will need to have a broad topic of interest in mind. [1] . In my experience, students can confuse this broad topic with the actual research question, so it is important to clearly distinguish the two. And the place to start is the broad topic. It might be, as was the case with me, working-class college students. But what about working-class college students? What’s it like to be one? Why are there so few compared to others? How do colleges assist (or fail to assist) them? What interested me was something I could barely articulate at first and went something like this: “Why was it so difficult and lonely to be me?” And by extension, “Did others share this experience?”

Once you have a general topic, reflect on why this is important to you. Sometimes we connect with a topic and we don’t really know why. Even if you are not willing to share the real underlying reason you are interested in a topic, it is important that you know the deeper reasons that motivate you. Otherwise, it is quite possible that at some point during the research, you will find yourself turned around facing the wrong direction. I have seen it happen many times. The reason is that the research question is not the same thing as the general topic of interest, and if you don’t know the reasons for your interest, you are likely to design a study answering a research question that is beside the point—to you, at least. And this means you will be much less motivated to carry your research to completion.

Researcher Note

Why do you employ qualitative research methods in your area of study? What are the advantages of qualitative research methods for studying mentorship?

Qualitative research methods are a huge opportunity to increase access, equity, inclusion, and social justice. Qualitative research allows us to engage and examine the uniquenesses/nuances within minoritized and dominant identities and our experiences with these identities. Qualitative research allows us to explore a specific topic, and through that exploration, we can link history to experiences and look for patterns or offer up a unique phenomenon. There’s such beauty in being able to tell a particular story, and qualitative research is a great mode for that! For our work, we examined the relationships we typically use the term mentorship for but didn’t feel that was quite the right word. Qualitative research allowed us to pick apart what we did and how we engaged in our relationships, which then allowed us to more accurately describe what was unique about our mentorship relationships, which we ultimately named liberationships ( McAloney and Long 2021) . Qualitative research gave us the means to explore, process, and name our experiences; what a powerful tool!

How do you come up with ideas for what to study (and how to study it)? Where did you get the idea for studying mentorship?

Coming up with ideas for research, for me, is kind of like Googling a question I have, not finding enough information, and then deciding to dig a little deeper to get the answer. The idea to study mentorship actually came up in conversation with my mentorship triad. We were talking in one of our meetings about our relationship—kind of meta, huh? We discussed how we felt that mentorship was not quite the right term for the relationships we had built. One of us asked what was different about our relationships and mentorship. This all happened when I was taking an ethnography course. During the next session of class, we were discussing auto- and duoethnography, and it hit me—let’s explore our version of mentorship, which we later went on to name liberationships ( McAloney and Long 2021 ). The idea and questions came out of being curious and wanting to find an answer. As I continue to research, I see opportunities in questions I have about my work or during conversations that, in our search for answers, end up exposing gaps in the literature. If I can’t find the answer already out there, I can study it.

—Kim McAloney, PhD, College Student Services Administration Ecampus coordinator and instructor

When you have a better idea of why you are interested in what it is that interests you, you may be surprised to learn that the obvious approaches to the topic are not the only ones. For example, let’s say you think you are interested in preserving coastal wildlife. And as a social scientist, you are interested in policies and practices that affect the long-term viability of coastal wildlife, especially around fishing communities. It would be natural then to consider designing a research study around fishing communities and how they manage their ecosystems. But when you really think about it, you realize that what interests you the most is how people whose livelihoods depend on a particular resource act in ways that deplete that resource. Or, even deeper, you contemplate the puzzle, “How do people justify actions that damage their surroundings?” Now, there are many ways to design a study that gets at that broader question, and not all of them are about fishing communities, although that is certainly one way to go. Maybe you could design an interview-based study that includes and compares loggers, fishers, and desert golfers (those who golf in arid lands that require a great deal of wasteful irrigation). Or design a case study around one particular example where resources were completely used up by a community. Without knowing what it is you are really interested in, what motivates your interest in a surface phenomenon, you are unlikely to come up with the appropriate research design.

These first stages of research design are often the most difficult, but have patience . Taking the time to consider why you are going to go through a lot of trouble to get answers will prevent a lot of wasted energy in the future.

There are distinct reasons for pursuing particular research questions, and it is helpful to distinguish between them. First, you may be personally motivated. This is probably the most important and the most often overlooked. What is it about the social world that sparks your curiosity? What bothers you? What answers do you need in order to keep living? For me, I knew I needed to get a handle on what higher education was for before I kept going at it. I needed to understand why I felt so different from my peers and whether this whole “higher education” thing was “for the likes of me” before I could complete my degree. That is the personal motivation question. Your personal motivation might also be political in nature, in that you want to change the world in a particular way. It’s all right to acknowledge this. In fact, it is better to acknowledge it than to hide it.

There are also academic and professional motivations for a particular study. If you are an absolute beginner, these may be difficult to find. We’ll talk more about this when we discuss reviewing the literature. Simply put, you are probably not the only person in the world to have thought about this question or issue and those related to it. So how does your interest area fit into what others have studied? Perhaps there is a good study out there of fishing communities, but no one has quite asked the “justification” question. You are motivated to address this to “fill the gap” in our collective knowledge. And maybe you are really not at all sure of what interests you, but you do know that [insert your topic] interests a lot of people, so you would like to work in this area too. You want to be involved in the academic conversation. That is a professional motivation and a very important one to articulate.

Practical and strategic motivations are a third kind. Perhaps you want to encourage people to take better care of the natural resources around them. If this is also part of your motivation, you will want to design your research project in a way that might have an impact on how people behave in the future. There are many ways to do this, one of which is using qualitative research methods rather than quantitative research methods, as the findings of qualitative research are often easier to communicate to a broader audience than the results of quantitative research. You might even be able to engage the community you are studying in the collecting and analyzing of data, something taboo in quantitative research but actively embraced and encouraged by qualitative researchers. But there are other practical reasons, such as getting “done” with your research in a certain amount of time or having access (or no access) to certain information. There is nothing wrong with considering constraints and opportunities when designing your study. Or maybe one of the practical or strategic goals is about learning competence in this area so that you can demonstrate the ability to conduct interviews and focus groups with future employers. Keeping that in mind will help shape your study and prevent you from getting sidetracked using a technique that you are less invested in learning about.

STOP HERE for a moment

I recommend you write a paragraph (at least) explaining your aims and goals. Include a sentence about each of the following: personal/political goals, practical or professional/academic goals, and practical/strategic goals. Think through how all of the goals are related and can be achieved by this particular research study . If they can’t, have a rethink. Perhaps this is not the best way to go about it.

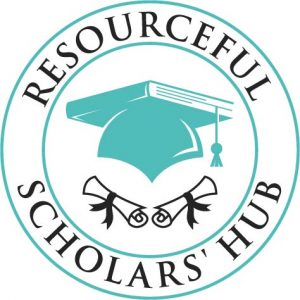

You will also want to be clear about the purpose of your study. “Wait, didn’t we just do this?” you might ask. No! Your goals are not the same as the purpose of the study, although they are related. You can think about purpose lying on a continuum from “ theory ” to “action” (figure 2.1). Sometimes you are doing research to discover new knowledge about the world, while other times you are doing a study because you want to measure an impact or make a difference in the world.

Basic research involves research that is done for the sake of “pure” knowledge—that is, knowledge that, at least at this moment in time, may not have any apparent use or application. Often, and this is very important, knowledge of this kind is later found to be extremely helpful in solving problems. So one way of thinking about basic research is that it is knowledge for which no use is yet known but will probably one day prove to be extremely useful. If you are doing basic research, you do not need to argue its usefulness, as the whole point is that we just don’t know yet what this might be.

Researchers engaged in basic research want to understand how the world operates. They are interested in investigating a phenomenon to get at the nature of reality with regard to that phenomenon. The basic researcher’s purpose is to understand and explain ( Patton 2002:215 ).

Basic research is interested in generating and testing hypotheses about how the world works. Grounded Theory is one approach to qualitative research methods that exemplifies basic research (see chapter 4). Most academic journal articles publish basic research findings. If you are working in academia (e.g., writing your dissertation), the default expectation is that you are conducting basic research.

Applied research in the social sciences is research that addresses human and social problems. Unlike basic research, the researcher has expectations that the research will help contribute to resolving a problem, if only by identifying its contours, history, or context. From my experience, most students have this as their baseline assumption about research. Why do a study if not to make things better? But this is a common mistake. Students and their committee members are often working with default assumptions here—the former thinking about applied research as their purpose, the latter thinking about basic research: “The purpose of applied research is to contribute knowledge that will help people to understand the nature of a problem in order to intervene, thereby allowing human beings to more effectively control their environment. While in basic research the source of questions is the tradition within a scholarly discipline, in applied research the source of questions is in the problems and concerns experienced by people and by policymakers” ( Patton 2002:217 ).

Applied research is less geared toward theory in two ways. First, its questions do not derive from previous literature. For this reason, applied research studies have much more limited literature reviews than those found in basic research (although they make up for this by having much more “background” about the problem). Second, it does not generate theory in the same way as basic research does. The findings of an applied research project may not be generalizable beyond the boundaries of this particular problem or context. The findings are more limited. They are useful now but may be less useful later. This is why basic research remains the default “gold standard” of academic research.

Evaluation research is research that is designed to evaluate or test the effectiveness of specific solutions and programs addressing specific social problems. We already know the problems, and someone has already come up with solutions. There might be a program, say, for first-generation college students on your campus. Does this program work? Are first-generation students who participate in the program more likely to graduate than those who do not? These are the types of questions addressed by evaluation research. There are two types of research within this broader frame; however, one more action-oriented than the next. In summative evaluation , an overall judgment about the effectiveness of a program or policy is made. Should we continue our first-gen program? Is it a good model for other campuses? Because the purpose of such summative evaluation is to measure success and to determine whether this success is scalable (capable of being generalized beyond the specific case), quantitative data is more often used than qualitative data. In our example, we might have “outcomes” data for thousands of students, and we might run various tests to determine if the better outcomes of those in the program are statistically significant so that we can generalize the findings and recommend similar programs elsewhere. Qualitative data in the form of focus groups or interviews can then be used for illustrative purposes, providing more depth to the quantitative analyses. In contrast, formative evaluation attempts to improve a program or policy (to help “form” or shape its effectiveness). Formative evaluations rely more heavily on qualitative data—case studies, interviews, focus groups. The findings are meant not to generalize beyond the particular but to improve this program. If you are a student seeking to improve your qualitative research skills and you do not care about generating basic research, formative evaluation studies might be an attractive option for you to pursue, as there are always local programs that need evaluation and suggestions for improvement. Again, be very clear about your purpose when talking through your research proposal with your committee.

Action research takes a further step beyond evaluation, even formative evaluation, to being part of the solution itself. This is about as far from basic research as one could get and definitely falls beyond the scope of “science,” as conventionally defined. The distinction between action and research is blurry, the research methods are often in constant flux, and the only “findings” are specific to the problem or case at hand and often are findings about the process of intervention itself. Rather than evaluate a program as a whole, action research often seeks to change and improve some particular aspect that may not be working—maybe there is not enough diversity in an organization or maybe women’s voices are muted during meetings and the organization wonders why and would like to change this. In a further step, participatory action research , those women would become part of the research team, attempting to amplify their voices in the organization through participation in the action research. As action research employs methods that involve people in the process, focus groups are quite common.

If you are working on a thesis or dissertation, chances are your committee will expect you to be contributing to fundamental knowledge and theory ( basic research ). If your interests lie more toward the action end of the continuum, however, it is helpful to talk to your committee about this before you get started. Knowing your purpose in advance will help avoid misunderstandings during the later stages of the research process!

The Research Question

Once you have written your paragraph and clarified your purpose and truly know that this study is the best study for you to be doing right now , you are ready to write and refine your actual research question. Know that research questions are often moving targets in qualitative research, that they can be refined up to the very end of data collection and analysis. But you do have to have a working research question at all stages. This is your “anchor” when you get lost in the data. What are you addressing? What are you looking at and why? Your research question guides you through the thicket. It is common to have a whole host of questions about a phenomenon or case, both at the outset and throughout the study, but you should be able to pare it down to no more than two or three sentences when asked. These sentences should both clarify the intent of the research and explain why this is an important question to answer. More on refining your research question can be found in chapter 4.

Chances are, you will have already done some prior reading before coming up with your interest and your questions, but you may not have conducted a systematic literature review. This is the next crucial stage to be completed before venturing further. You don’t want to start collecting data and then realize that someone has already beaten you to the punch. A review of the literature that is already out there will let you know (1) if others have already done the study you are envisioning; (2) if others have done similar studies, which can help you out; and (3) what ideas or concepts are out there that can help you frame your study and make sense of your findings. More on literature reviews can be found in chapter 9.

In addition to reviewing the literature for similar studies to what you are proposing, it can be extremely helpful to find a study that inspires you. This may have absolutely nothing to do with the topic you are interested in but is written so beautifully or organized so interestingly or otherwise speaks to you in such a way that you want to post it somewhere to remind you of what you want to be doing. You might not understand this in the early stages—why would you find a study that has nothing to do with the one you are doing helpful? But trust me, when you are deep into analysis and writing, having an inspirational model in view can help you push through. If you are motivated to do something that might change the world, you probably have read something somewhere that inspired you. Go back to that original inspiration and read it carefully and see how they managed to convey the passion that you so appreciate.

At this stage, you are still just getting started. There are a lot of things to do before setting forth to collect data! You’ll want to consider and choose a research tradition and a set of data-collection techniques that both help you answer your research question and match all your aims and goals. For example, if you really want to help migrant workers speak for themselves, you might draw on feminist theory and participatory action research models. Chapters 3 and 4 will provide you with more information on epistemologies and approaches.

Next, you have to clarify your “units of analysis.” What is the level at which you are focusing your study? Often, the unit in qualitative research methods is individual people, or “human subjects.” But your units of analysis could just as well be organizations (colleges, hospitals) or programs or even whole nations. Think about what it is you want to be saying at the end of your study—are the insights you are hoping to make about people or about organizations or about something else entirely? A unit of analysis can even be a historical period! Every unit of analysis will call for a different kind of data collection and analysis and will produce different kinds of “findings” at the conclusion of your study. [2]

Regardless of what unit of analysis you select, you will probably have to consider the “human subjects” involved in your research. [3] Who are they? What interactions will you have with them—that is, what kind of data will you be collecting? Before answering these questions, define your population of interest and your research setting. Use your research question to help guide you.

Let’s use an example from a real study. In Geographies of Campus Inequality , Benson and Lee ( 2020 ) list three related research questions: “(1) What are the different ways that first-generation students organize their social, extracurricular, and academic activities at selective and highly selective colleges? (2) how do first-generation students sort themselves and get sorted into these different types of campus lives; and (3) how do these different patterns of campus engagement prepare first-generation students for their post-college lives?” (3).

Note that we are jumping into this a bit late, after Benson and Lee have described previous studies (the literature review) and what is known about first-generation college students and what is not known. They want to know about differences within this group, and they are interested in ones attending certain kinds of colleges because those colleges will be sites where academic and extracurricular pressures compete. That is the context for their three related research questions. What is the population of interest here? First-generation college students . What is the research setting? Selective and highly selective colleges . But a host of questions remain. Which students in the real world, which colleges? What about gender, race, and other identity markers? Will the students be asked questions? Are the students still in college, or will they be asked about what college was like for them? Will they be observed? Will they be shadowed? Will they be surveyed? Will they be asked to keep diaries of their time in college? How many students? How many colleges? For how long will they be observed?

Recommendation

Take a moment and write down suggestions for Benson and Lee before continuing on to what they actually did.

Have you written down your own suggestions? Good. Now let’s compare those with what they actually did. Benson and Lee drew on two sources of data: in-depth interviews with sixty-four first-generation students and survey data from a preexisting national survey of students at twenty-eight selective colleges. Let’s ignore the survey for our purposes here and focus on those interviews. The interviews were conducted between 2014 and 2016 at a single selective college, “Hilltop” (a pseudonym ). They employed a “purposive” sampling strategy to ensure an equal number of male-identifying and female-identifying students as well as equal numbers of White, Black, and Latinx students. Each student was interviewed once. Hilltop is a selective liberal arts college in the northeast that enrolls about three thousand students.

How did your suggestions match up to those actually used by the researchers in this study? It is possible your suggestions were too ambitious? Beginning qualitative researchers can often make that mistake. You want a research design that is both effective (it matches your question and goals) and doable. You will never be able to collect data from your entire population of interest (unless your research question is really so narrow to be relevant to very few people!), so you will need to come up with a good sample. Define the criteria for this sample, as Benson and Lee did when deciding to interview an equal number of students by gender and race categories. Define the criteria for your sample setting too. Hilltop is typical for selective colleges. That was a research choice made by Benson and Lee. For more on sampling and sampling choices, see chapter 5.

Benson and Lee chose to employ interviews. If you also would like to include interviews, you have to think about what will be asked in them. Most interview-based research involves an interview guide, a set of questions or question areas that will be asked of each participant. The research question helps you create a relevant interview guide. You want to ask questions whose answers will provide insight into your research question. Again, your research question is the anchor you will continually come back to as you plan for and conduct your study. It may be that once you begin interviewing, you find that people are telling you something totally unexpected, and this makes you rethink your research question. That is fine. Then you have a new anchor. But you always have an anchor. More on interviewing can be found in chapter 11.

Let’s imagine Benson and Lee also observed college students as they went about doing the things college students do, both in the classroom and in the clubs and social activities in which they participate. They would have needed a plan for this. Would they sit in on classes? Which ones and how many? Would they attend club meetings and sports events? Which ones and how many? Would they participate themselves? How would they record their observations? More on observation techniques can be found in both chapters 13 and 14.

At this point, the design is almost complete. You know why you are doing this study, you have a clear research question to guide you, you have identified your population of interest and research setting, and you have a reasonable sample of each. You also have put together a plan for data collection, which might include drafting an interview guide or making plans for observations. And so you know exactly what you will be doing for the next several months (or years!). To put the project into action, there are a few more things necessary before actually going into the field.

First, you will need to make sure you have any necessary supplies, including recording technology. These days, many researchers use their phones to record interviews. Second, you will need to draft a few documents for your participants. These include informed consent forms and recruiting materials, such as posters or email texts, that explain what this study is in clear language. Third, you will draft a research protocol to submit to your institutional review board (IRB) ; this research protocol will include the interview guide (if you are using one), the consent form template, and all examples of recruiting material. Depending on your institution and the details of your study design, it may take weeks or even, in some unfortunate cases, months before you secure IRB approval. Make sure you plan on this time in your project timeline. While you wait, you can continue to review the literature and possibly begin drafting a section on the literature review for your eventual presentation/publication. More on IRB procedures can be found in chapter 8 and more general ethical considerations in chapter 7.

Once you have approval, you can begin!

Research Design Checklist

Before data collection begins, do the following:

- Write a paragraph explaining your aims and goals (personal/political, practical/strategic, professional/academic).

- Define your research question; write two to three sentences that clarify the intent of the research and why this is an important question to answer.

- Review the literature for similar studies that address your research question or similar research questions; think laterally about some literature that might be helpful or illuminating but is not exactly about the same topic.

- Find a written study that inspires you—it may or may not be on the research question you have chosen.

- Consider and choose a research tradition and set of data-collection techniques that (1) help answer your research question and (2) match your aims and goals.

- Define your population of interest and your research setting.

- Define the criteria for your sample (How many? Why these? How will you find them, gain access, and acquire consent?).

- If you are conducting interviews, draft an interview guide.

- If you are making observations, create a plan for observations (sites, times, recording, access).

- Acquire any necessary technology (recording devices/software).

- Draft consent forms that clearly identify the research focus and selection process.

- Create recruiting materials (posters, email, texts).

- Apply for IRB approval (proposal plus consent form plus recruiting materials).

- Block out time for collecting data.

- At the end of the chapter, you will find a " Research Design Checklist " that summarizes the main recommendations made here ↵

- For example, if your focus is society and culture , you might collect data through observation or a case study. If your focus is individual lived experience , you are probably going to be interviewing some people. And if your focus is language and communication , you will probably be analyzing text (written or visual). ( Marshall and Rossman 2016:16 ). ↵

- You may not have any "live" human subjects. There are qualitative research methods that do not require interactions with live human beings - see chapter 16 , "Archival and Historical Sources." But for the most part, you are probably reading this textbook because you are interested in doing research with people. The rest of the chapter will assume this is the case. ↵

One of the primary methodological traditions of inquiry in qualitative research, ethnography is the study of a group or group culture, largely through observational fieldwork supplemented by interviews. It is a form of fieldwork that may include participant-observation data collection. See chapter 14 for a discussion of deep ethnography.

A methodological tradition of inquiry and research design that focuses on an individual case (e.g., setting, institution, or sometimes an individual) in order to explore its complexity, history, and interactive parts. As an approach, it is particularly useful for obtaining a deep appreciation of an issue, event, or phenomenon of interest in its particular context.

The controlling force in research; can be understood as lying on a continuum from basic research (knowledge production) to action research (effecting change).

In its most basic sense, a theory is a story we tell about how the world works that can be tested with empirical evidence. In qualitative research, we use the term in a variety of ways, many of which are different from how they are used by quantitative researchers. Although some qualitative research can be described as “testing theory,” it is more common to “build theory” from the data using inductive reasoning , as done in Grounded Theory . There are so-called “grand theories” that seek to integrate a whole series of findings and stories into an overarching paradigm about how the world works, and much smaller theories or concepts about particular processes and relationships. Theory can even be used to explain particular methodological perspectives or approaches, as in Institutional Ethnography , which is both a way of doing research and a theory about how the world works.

Research that is interested in generating and testing hypotheses about how the world works.

A methodological tradition of inquiry and approach to analyzing qualitative data in which theories emerge from a rigorous and systematic process of induction. This approach was pioneered by the sociologists Glaser and Strauss (1967). The elements of theory generated from comparative analysis of data are, first, conceptual categories and their properties and, second, hypotheses or generalized relations among the categories and their properties – “The constant comparing of many groups draws the [researcher’s] attention to their many similarities and differences. Considering these leads [the researcher] to generate abstract categories and their properties, which, since they emerge from the data, will clearly be important to a theory explaining the kind of behavior under observation.” (36).

An approach to research that is “multimethod in focus, involving an interpretative, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. Qualitative research involves the studied use and collection of a variety of empirical materials – case study, personal experience, introspective, life story, interview, observational, historical, interactional, and visual texts – that describe routine and problematic moments and meanings in individuals’ lives." ( Denzin and Lincoln 2005:2 ). Contrast with quantitative research .

Research that contributes knowledge that will help people to understand the nature of a problem in order to intervene, thereby allowing human beings to more effectively control their environment.

Research that is designed to evaluate or test the effectiveness of specific solutions and programs addressing specific social problems. There are two kinds: summative and formative .

Research in which an overall judgment about the effectiveness of a program or policy is made, often for the purpose of generalizing to other cases or programs. Generally uses qualitative research as a supplement to primary quantitative data analyses. Contrast formative evaluation research .

Research designed to improve a program or policy (to help “form” or shape its effectiveness); relies heavily on qualitative research methods. Contrast summative evaluation research

Research carried out at a particular organizational or community site with the intention of affecting change; often involves research subjects as participants of the study. See also participatory action research .

Research in which both researchers and participants work together to understand a problematic situation and change it for the better.

The level of the focus of analysis (e.g., individual people, organizations, programs, neighborhoods).

The large group of interest to the researcher. Although it will likely be impossible to design a study that incorporates or reaches all members of the population of interest, this should be clearly defined at the outset of a study so that a reasonable sample of the population can be taken. For example, if one is studying working-class college students, the sample may include twenty such students attending a particular college, while the population is “working-class college students.” In quantitative research, clearly defining the general population of interest is a necessary step in generalizing results from a sample. In qualitative research, defining the population is conceptually important for clarity.

A fictional name assigned to give anonymity to a person, group, or place. Pseudonyms are important ways of protecting the identity of research participants while still providing a “human element” in the presentation of qualitative data. There are ethical considerations to be made in selecting pseudonyms; some researchers allow research participants to choose their own.

A requirement for research involving human participants; the documentation of informed consent. In some cases, oral consent or assent may be sufficient, but the default standard is a single-page easy-to-understand form that both the researcher and the participant sign and date. Under federal guidelines, all researchers "shall seek such consent only under circumstances that provide the prospective subject or the representative sufficient opportunity to consider whether or not to participate and that minimize the possibility of coercion or undue influence. The information that is given to the subject or the representative shall be in language understandable to the subject or the representative. No informed consent, whether oral or written, may include any exculpatory language through which the subject or the representative is made to waive or appear to waive any of the subject's rights or releases or appears to release the investigator, the sponsor, the institution, or its agents from liability for negligence" (21 CFR 50.20). Your IRB office will be able to provide a template for use in your study .

An administrative body established to protect the rights and welfare of human research subjects recruited to participate in research activities conducted under the auspices of the institution with which it is affiliated. The IRB is charged with the responsibility of reviewing all research involving human participants. The IRB is concerned with protecting the welfare, rights, and privacy of human subjects. The IRB has the authority to approve, disapprove, monitor, and require modifications in all research activities that fall within its jurisdiction as specified by both the federal regulations and institutional policy.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Make a Literature Review in Research (RRL Example)

What is an RRL in a research paper?

A relevant review of the literature (RRL) is an objective, concise, critical summary of published research literature relevant to a topic being researched in an article. In an RRL, you discuss knowledge and findings from existing literature relevant to your study topic. If there are conflicts or gaps in existing literature, you can also discuss these in your review, as well as how you will confront these missing elements or resolve these issues in your study.

To complete an RRL, you first need to collect relevant literature; this can include online and offline sources. Save all of your applicable resources as you will need to include them in your paper. When looking through these sources, take notes and identify concepts of each source to describe in the review of the literature.

A good RRL does NOT:

A literature review does not simply reference and list all of the material you have cited in your paper.

- Presenting material that is not directly relevant to your study will distract and frustrate the reader and make them lose sight of the purpose of your study.

- Starting a literature review with “A number of scholars have studied the relationship between X and Y” and simply listing who has studied the topic and what each scholar concluded is not going to strengthen your paper.

A good RRL DOES:

- Present a brief typology that orders articles and books into groups to help readers focus on unresolved debates, inconsistencies, tensions, and new questions about a research topic.

- Summarize the most relevant and important aspects of the scientific literature related to your area of research

- Synthesize what has been done in this area of research and by whom, highlight what previous research indicates about a topic, and identify potential gaps and areas of disagreement in the field

- Give the reader an understanding of the background of the field and show which studies are important—and highlight errors in previous studies

How long is a review of the literature for a research paper?

The length of a review of the literature depends on its purpose and target readership and can vary significantly in scope and depth. In a dissertation, thesis, or standalone review of literature, it is usually a full chapter of the text (at least 20 pages). Whereas, a standard research article or school assignment literature review section could only be a few paragraphs in the Introduction section .

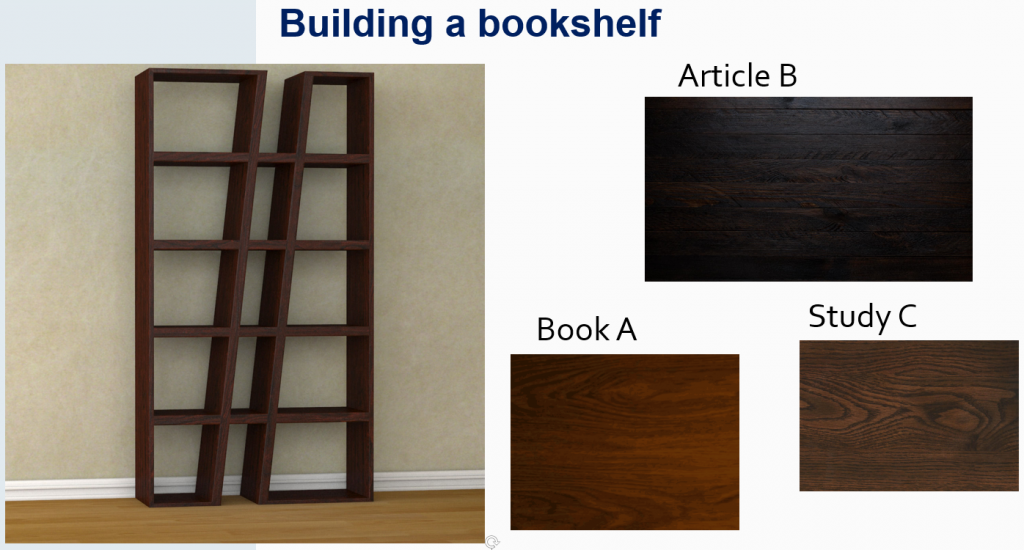

Building Your Literature Review Bookshelf

One way to conceive of a literature review is to think about writing it as you would build a bookshelf. You don’t need to cut each piece by yourself from scratch. Rather, you can take the pieces that other researchers have cut out and put them together to build a framework on which to hang your own “books”—that is, your own study methods, results, and conclusions.

What Makes a Good Literature Review?

The contents of a literature review (RRL) are determined by many factors, including its precise purpose in the article, the degree of consensus with a given theory or tension between competing theories, the length of the article, the number of previous studies existing in the given field, etc. The following are some of the most important elements that a literature review provides.

Historical background for your research

Analyze what has been written about your field of research to highlight what is new and significant in your study—or how the analysis itself contributes to the understanding of this field, even in a small way. Providing a historical background also demonstrates to other researchers and journal editors your competency in discussing theoretical concepts. You should also make sure to understand how to paraphrase scientific literature to avoid plagiarism in your work.

The current context of your research

Discuss central (or peripheral) questions, issues, and debates in the field. Because a field is constantly being updated by new work, you can show where your research fits into this context and explain developments and trends in research.

A discussion of relevant theories and concepts

Theories and concepts should provide the foundation for your research. For example, if you are researching the relationship between ecological environments and human populations, provide models and theories that focus on specific aspects of this connection to contextualize your study. If your study asks a question concerning sustainability, mention a theory or model that underpins this concept. If it concerns invasive species, choose material that is focused in this direction.

Definitions of relevant terminology

In the natural sciences, the meaning of terms is relatively straightforward and consistent. But if you present a term that is obscure or context-specific, you should define the meaning of the term in the Introduction section (if you are introducing a study) or in the summary of the literature being reviewed.

Description of related relevant research

Include a description of related research that shows how your work expands or challenges earlier studies or fills in gaps in previous work. You can use your literature review as evidence of what works, what doesn’t, and what is missing in the field.

Supporting evidence for a practical problem or issue your research is addressing that demonstrates its importance: Referencing related research establishes your area of research as reputable and shows you are building upon previous work that other researchers have deemed significant.

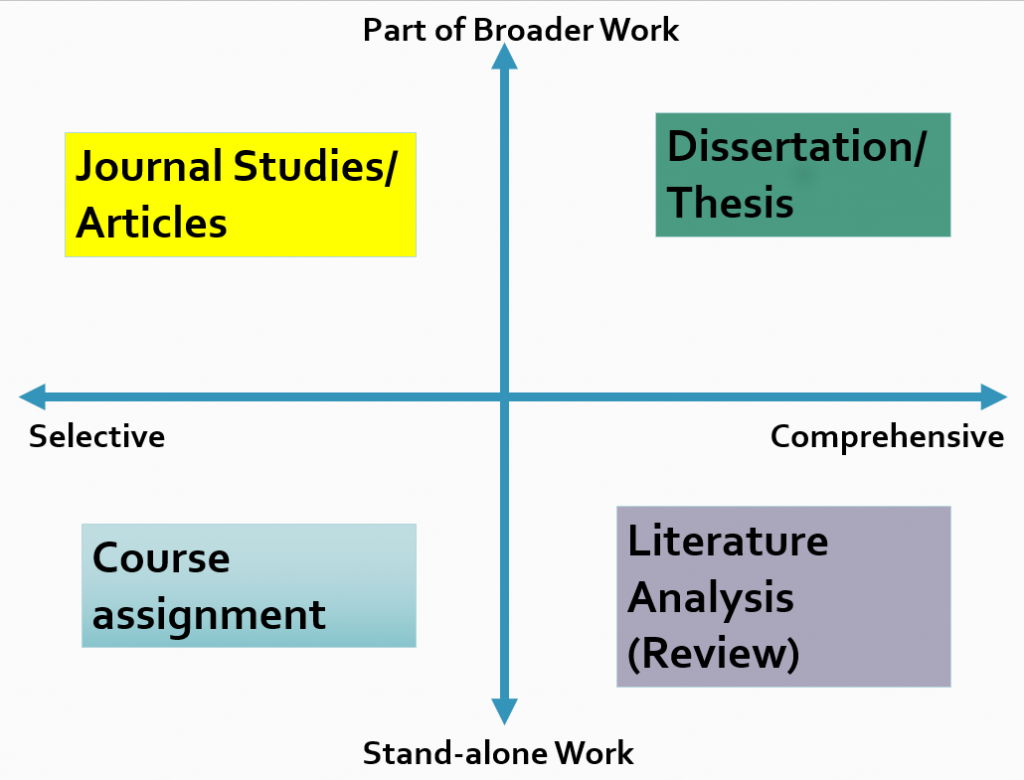

Types of Literature Reviews

Literature reviews can differ in structure, length, amount, and breadth of content included. They can range from selective (a very narrow area of research or only a single work) to comprehensive (a larger amount or range of works). They can also be part of a larger work or stand on their own.

- A course assignment is an example of a selective, stand-alone work. It focuses on a small segment of the literature on a topic and makes up an entire work on its own.

- The literature review in a dissertation or thesis is both comprehensive and helps make up a larger work.

- A majority of journal articles start with a selective literature review to provide context for the research reported in the study; such a literature review is usually included in the Introduction section (but it can also follow the presentation of the results in the Discussion section ).

- Some literature reviews are both comprehensive and stand as a separate work—in this case, the entire article analyzes the literature on a given topic.

Literature Reviews Found in Academic Journals

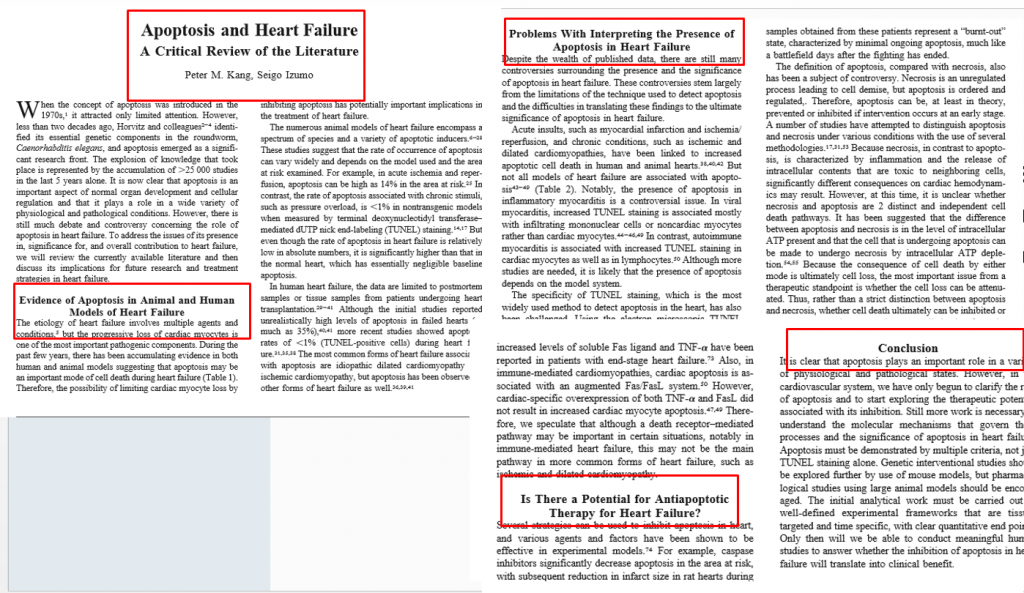

The two types of literature reviews commonly found in journals are those introducing research articles (studies and surveys) and stand-alone literature analyses. They can differ in their scope, length, and specific purpose.

Literature reviews introducing research articles

The literature review found at the beginning of a journal article is used to introduce research related to the specific study and is found in the Introduction section, usually near the end. It is shorter than a stand-alone review because it must be limited to very specific studies and theories that are directly relevant to the current study. Its purpose is to set research precedence and provide support for the study’s theory, methods, results, and/or conclusions. Not all research articles contain an explicit review of the literature, but most do, whether it is a discrete section or indistinguishable from the rest of the Introduction.

How to structure a literature review for an article