An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Elsevier - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Analysis of the COVID-19 impacts on employment and unemployment across the multi-dimensional social disadvantaged areas

This is the study of economic impacts in the context of social disadvantage. It specifically considers economic conditions in regions with pre-existing inequalities and examines labor market outcomes in already socially vulnerable areas. The economic outcomes remain relatively unexplored by the studies on the COVID-19 impacts. To fill the gap, we study the relationship between the pandemic-caused economic recession and vulnerable communities in the unprecedented times. More marginalized regions may have broader economic damages related to the pandemic. First, based on a literature review, we delineate areas with high social disadvantage. These areas have multiple factors associated with various dimensions of vulnerability which existed pre-COVID-19. We term these places “ multi-dimensional social disadvantaged areas ”. Second, we compare employment and unemployment rates between areas with high and low disadvantage. We integrate geospatial science with the exploration of social factors associated with disadvantage across counties in Tennessee which is part of coronavirus “red zone” states of the US southern Sunbelt region. We disagree with a misleading label of COVID-19 as the “great equalizer”. During COVID-19, marginalized regions experience disproportionate economic impacts. The negative effect of social disadvantage on pandemic-caused economic outcomes is supported by several lines of evidence. We find that both urban and rural areas may be vulnerable to the broad social and economic damages. The study contributes to current research on economic impacts of the COVID-19 outbreak and social distributions of economic vulnerability. The results can help inform post-COVID recovery interventions strategies to reduce COVID-19-related economic vulnerability burdens.

1. Introduction: social disadvantage

Pandemics create severe disruptions to a functioning society. The economic and social disruptions intersect in complex ways and affect physical and mental health and illness ( Wu et al, 2020 ). Additionally, loss of jobs, wages, housing, or health insurance, as well as disruption to health care, hospital avoidance, postponement of planned medical treatment increase mortality, e.g., premature deaths ( Kiang et al., 2020 ; Petterson et al., 2020 ). The COVID-19, misleadingly labelled the “great equalizer” implies everyone is equally vulnerable to the virus, and that the economic activity of almost everyone is similarly impacted regardless of social status ( Jones & Jones, 2020 ). We set out to answer whether economic vulnerability is equally distributed during the COVID-19-caused economic recession or whether is it based on structural disadvantages? Is the social distribution of economic vulnerability magnified in regions with pre-existing social disparities, thus, creating new forms of inequalities? Knowledge of what areas experience the greater economic burden will help identify the most economically vulnerable communities relevant to post-COVID recovery interventions ( Qian and Fan, 2020 ).

Current studies on the impacts of COVID-19 largely focus on medical aspects including the COVID diagnosis and treatment ( Cai et al., 2020 ; Kass et al., 2020 ; O’Hearn et al., 2021 ; Price-Haywood et al., 2020 ). Non-medical urban research primarily concentrates on the impact of COVID on cities by studying factors related to environmental quality including meteorological parameters, and air and water quality ( Sharifi and Khavarian-Garmsir, 2020 ). COVID-related socio-economic impacts on cities are relatively less well studied, especially during the later stages of the recession.

Many pre-pandemic disparities unfold during COVID-19. To illustrate, residents of Black and Latino communities are suffering disproportionately higher unemployment rates, greater mortality due to the COVID-19 ( Thebault, Tran, & Williams, 2020 ; Wade, 2020 ), higher hospitalizations ( O’Hearn et al., 2021 ) and financial troubles. In contrast, some attributes make persons and communities more resilient. In China’s context, these include higher worker education and family economic status, membership in Communist Party, state-sector employment, and other traditional markers. These factors protect people from the pandemic-related financial stress and diminish its adverse economic effects ( Qian and Fan, 2020 ). Building on these recent studies on economic impacts, this social justice research focuses on areas with pre-existing social disadvantages. We study the role of social disadvantage and its impact on labor market during the COVID.

The distribution of economic vulnerability may potentially be related to COVID-19 conditions including those of economic burdens for people living in the pandemic epicenters ( Creţan and Light, 2020 ). Similarly, socio-economic disruptions create “a characteristic mosaic pattern in the region” ( Krzysztofik et al., 2020 , p. 583). The disruptions are strongly correlated with the spatial distribution of the COVID-19-related health effects. This study is set in Tennessee which is part of coronavirus “red zone” states of the US southern Sunbelt region. It is among the U.S. states with the highest rates of cases per capita, with 137,829 cases per 1 million people, or the 6th highest as of August 13, 2021 ( Worldometers, 2020 ; https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/us/ ). The study seeks to explore the impacts of social disadvantage on economy. The impact is measured by employment and unemployment in unprecedented times in the US context of prolonged disruptions to the health system, society, and economy intersecting in complex ways ( Kiang et al., 2020 ). We answer the following questions: (1) Do communities with high social disadvantage already burdened pre-COVID-19 by the lack of income, healthcare access, lacking resources, have less jobs available during the COVID-19 pandemic? (2) Do these areas simultaneously experience higher unemployment compared with other areas in the context of the pandemic?

The paper is organized as follows: Section 1 introduces the topic, provides the background information on social disadvantage and a brief description of the study implementation. It further discusses the links between employment and unemployment, and coronavirus, respectively, and introduces the study area. Section 2 describes in detail materials and methods used in the study. Section 3 provides the theory and calculations. Section 4 reports the results, and Section 5 offers a discussion. Finally, the paper concludes with conclusions found in Section 6 .

1.1. Background

Certain socio-economic and demographic conditions burden some communities more than others including racial and ethnic minorities, lower-income groups, and rural residents. The conditions include lacking economic opportunities and other inequalities ( Petterson et al., 2020 ) caused by social environment. Prior to the pandemic, it was challenging to live in areas with high social disadvantage where residents already have increased vulnerability to poor health due to greater psychosocial stress such as discrimination, unhealthy behaviors, and poorer health status ( Hajat et al., 2015 ). This is true for poor, marginalized communities elsewhere as spatial segregation of disadvantaged and marginalized communities decreases life opportunities for their members who have limited relationships with broader communities ( Méreiné-Berki et al., 2021 ). Within the context of studying disadvantaged urban communities, a recent work by Creţan et al. (2020) focused on the everyday manifestations of contemporary stigmatization of the urban poor using the case study of the Roma people who have been historically subject to state discrimination, ghettoization, inadequate access to education, housing, and the labor market for many decades in the past in multicultural urban societies of Central and Eastern Europe. The inequalities may persist and even increase if left unaddressed during pandemics ( Wade, 2020 ) leading to stark COVID-19-related health and economic disparities. Indeed, during the COVID-19, economic impacts of the pandemic disproportionately affect marginalized groups. The impact of coronavirus was harsh for those people as many of the already existing disparities unfold during COVID-19: black communities in the United States are disproportionately affected by higher death rates due to the COVID-19 virus ( Thebault et al., 2020 ), unemployment, and financial stress. Other growing COVID-19 research similarly suggests that elsewhere outside of the United States, areas that were disadvantaged prior to the pandemic with high rates of poverty and unemployment tended to be affected the strongest by the COVID-19 with the largest concentration of cases, while other spatially segregated ethnicity-based communities (e.g., the Roma) that have been vulnerable decades prior to COVID-19, saw an increase in the existing discrimination and stigmatization experiencing greater marginalization even during the current COVID-19 pandemic period ( Crețan & Light, 2020 ).

To achieve greater economic stability, and secure a dynamic labor market, countries in the global north and south for several decades have been increasing service employment much of which is low wage. The recent book Corona and Work around the Globe ( Eckert and Hentschke, 2020 ) describes the tremendous impact of the pandemic on human life and livelihoods as it sheds light on various experiences of workers during COVID-19 in various countries. Among the dramatically different cases worldwide, Germany which for decades has been promoting the low-wage sector to combat unemployment, provides a good example. The official approach to handling a disease differed substantially depending on whether the infected individuals were working people from the low- or upper-wage sector of the economy: applying a strict lockdown to the entire high-rise building where ethnic workers lived and preventing them from going to work in the former case and granting permission to work from home in the latter ( Mayer-Ahuja, 2020 ). The plight of the agricultural migrant workers who come to Germany from Eastern and Southeastern Europe, subjected during the pandemic to low wages or no payments and poor working and living conditions, however, is shared among the workers of low-wage sector across all countries who are more likely to get infected due to higher exposure and direct contact, but often experience unfair treatment based on ethnicity, migration and class status.

In yet another case set in the U.K., disadvantaged households have experienced intensified disadvantage during the COVID-19 as they could not access vital necessities, already stretched for resources pre-COVID-19. As provision of services or employment was discontinued due to their closure, disadvantaged households had significant impacts on their income level, mental health and wellbeing, education, nutrition, and domestic violence. In the absence of the key support of public institutions including schools, community centers, and social services, care for the most vulnerable members such as elderly, children, the disabled, have been absorbed by households ( Bear et al., 2020 ).

Another aspect experienced by workers during the pandemic is the total loss of earnings which is especially harsh in places with precarious employment even under normal circumstances. Informal workers in India who represent the vast majority of working population (over 93%), with no social security benefits and absent job security, experienced prolonged periods of time of no work due to lockdown and suspended transport services preventing them from getting to their workplaces, many on the verge of starvation ( Banerjee, 2020 ). This study looks into this aspect of COVID-19 economic impacts and confirms the findings of the growing COVID-19 research.

However, not only the poorest and marginalized people, but also marginalized regions are more likely to suffer from broader social and economic damages related to the pandemic compared with more privileged areas ( Creţan and Light, 2020 ; Krzysztofik et al., 2020 ). When disadvantages combine, it may lead to environment-driven COVID-19-related disparities in health. Besides a direct health effect, disadvantaged communities are disproportionally experiencing other side effects of COVID-19 such as negative labor market outcomes including forced unemployment, loss of income and social isolation. Studies found the extreme vulnerability of cities and urban areas exposed during the global pandemic ( Batty, 2020 ; Gössling et al., 2020 ). We argue that rural areas may be equally vulnerable to the broad range of social and economic damages if there is a spatial concentration of factors related to various dimensions of vulnerability.

This study is situated in the context of social disadvantage. Prior studies developed the methodology of the delineation of disadvantaged residential communities proxied by low-income workers ( Antipova, 2020 ). Disadvantaged low-income workers can be defined as those with inadequate access to material and social resources in the study area. However, this is a narrow approach which uses only a single dimension of a disadvantage, that of worker low earnings and misses other social inequality indicators. Accordingly, an approach adopted in this study identifies areas where socio-economic and demographic attributes each associated with multiple dimensions of social disadvantage are spatially co-locating. Spatial segregation of disadvantaged and marginalized communities decreases life opportunities for their members who have limited relationships with wider communities ( Méreiné-Berki et al., 2021 ). We identify these attributes based on a thorough literature review. Thus, we simultaneously consider multiple factors associated with disadvantage capturing a multi-dimensional social disadvantage. To meet the objective, we integrate geospatial science with the exploration of predictive geographic and social factors associated with disadvantage across counties in TN. The geospatial analysis includes point interpolation within the Geographic Information System (GIS) environment for the generation of a surface from a sample of social disadvantage values. This allowed us to visualize the spatial extent of disadvantaged communities. The focus is on labor market outcomes which are important indicators of society well-being. We study the association between pre-existing inequalities and COVID-19-related employment and unemployment rates. Thus, we identify the role of social disadvantage on labor market conditions in the context of the ongoing pandemic-caused economic recession.

Prior research determined the key metrics of social disadvantage. Conditions contributing to various aspects of disadvantage include poverty, occupations with low earnings, low rent, segregation and discrimination-related residential concentrations of minorities, and exposure to poor air quality ( Bullard, 2000 ). The recent COVID-19-related literature focuses on the separate effect of minorities, Hispanics, crowded households, dense areas, obesity, poverty, air pollution exposure and identifies those as important COVID-19 health risk factors ( Finch & Hernández Finch, 2020 ; Golestaneh et al., 2020 ; Han et al., 2020 ; Millett et al., 2020 ). These community-level variables result in neighborhood disadvantage comprising sub-standard housing quality, crowded conditions, poverty- and violence-caused stress which combined increase the risk of disease and other negative outcomes in life among socially disadvantaged groups ( Malhotra et al., 2014 ). The demographic and socio-economic attributes selected to represent the various aspects of social disadvantage in this research include minorities and ethnicities, poverty, housing crowdedness, educational attainment, underlying population health conditions, and pre-COVID-19 unemployment which may collectively drive a greater vulnerability to the COVID-19 infection and mortality as well as loss in employment and higher unemployment. It is challenging to isolate the separate effects of the multiple risk factors. By “critically analyzing the theoretically intended meaning of a concept” ( Song et al., 2013 ), a composite variable can be created to logically represent a multi-dimensional social disadvantage .

The following subsection briefly describes study implementation. First, we locate areas of disadvantage where multiple factors associated with various aspects of disadvantage co-locate spatially and term these places “multi-dimensional social disadvantaged areas”. Then, we examine how employment and unemployment were impacted in these already socially vulnerable areas. We map geographical inequalities in employment and unemployment rates during the period of COVID-19-related economic recession. For the first objective, we identify socially disadvantaged counties within TN which is part of coronavirus “red zone” states of the US southern Sunbelt region applying consistent criteria. For the second objective, we compare employment and unemployment outcomes between areas with high and low disadvantage.

1.1.1. Employment and coronavirus

This subsection discusses the role of employment and how it was impacted by the COVID-19-caused economic recession. The literature recognizes the complex interrelationship between employment and overall health and well-being. Negative COVID-19 impacts on urban economy include loss of citizens' income, while movement restrictions and ‘stay home’ measures adversely impacted tourism and hospitality and small- and medium sized businesses due to the closure of markets, food outlets and social spaces ( Wilkinson et al., 2020 ).

Millions of essential or blue-collar workers are still doing their jobs out of necessity and because they cannot telecommute and work jobs that cannot be done from home and have higher exposure to the virus. Some racial groups disproportionally have jobs that do not allow them to work from home and where social distancing is a challenge. Prior studies find that workplaces of low-income individuals tend to be close to their residential spaces, and disproportionately concentrated in lower-wage industries such as hospitality and retail services ( Antipova, 2020 ). These industries commonly represent essential services experiencing higher exposure to the COVID virus through workplaces. At the same time, minorities and lower-income groups often live in inner-ring suburbs with older housing and aging infrastructure ( Antipova, 2020 ) in multiunit structures and in multigenerational households which inhibit the ability to practice social distancing increasing the risks of disease occurrence and deaths ( Qualls et al., 2017 ). In addition, minorities and lower-income groups have fewer options for protecting both their health and economic well-being ( Gould and Wilson, 2020 ). Nearly two-thirds of Hispanic people (64.5%) considered at high risk for coronavirus live with at least one person who is unable to work from home, compared to 56.5% of black and less than half (47%) of white Americans, according to a recent study ( Selden and Berdahl, 2020 ).

Despite the pandemic-induced layoffs, job hires have occurred by major retailers such as Walmart and e-commerce giant Amazon, and takeout and delivery-based services such as Domino’s Pizza and Papa John’s which may become permanent positions. These workplaces may match the job skill sets of low-income residents of vulnerable communities. However, oftentimes many low-income workers benefitted less, even when jobs were created during the COVID-19. To illustrate, big technology companies (i.e., communication services: Netflix, Tencent, Facebook, T-Mobile; information technology: Microsoft, Nvidia, Apple, Zoom Video, PayPal, Shopify; consumer discretionary: Amazon, Tesla, Alibaba, etc.) prospered in the pandemic with the financial success measured by equity value added ( Financial Times, 2020 ). Workers who lost jobs in low-income segment such as hospitality sector may be hired by retailers such as Kroger or CVS. However, many others from the communities with high social disadvantage may not have a skill set needed at technology firms that benefit from the working from home trend and hire skilled workers including software engineers and product designers. Cross-industry employment shifts plays a minor role in total job creation, while employer-specific factors primarily account for job reallocation ( Barrero et al., 2020 ).

1.1.2. Unemployment and coronavirus

This subsection discusses how unemployment was impacted by the COVID-19-caused economic recession. An economic recession occurs when there is a substantial drop in overall economic activity diffused throughout the economy for longer than a few months. While past recessions were driven by an inherently economic or financial shock, the current recession is caused by a public health crisis ( Weinstock, 2020 ). COVID-19 caused a drop in consumer demand across all industrial sectors resulting in economic recession and massive unemployment where not only hourly workers but salaried professionals lost their jobs ( Petterson et al., 2020 ). A range of factors contributed to the spatial variation in economic damage including the share of jobs in industries delivering non-essential services to in-person customers ( Dey and Loewenstein, 2020 ), declines in personal consumption caused by individual fears of contracting COVID-19 ( Goolsbee and Syverson, 2020 ), and the implementation of social policies including stay-at-home orders and business shutdowns ( Gupta et al., 2020 ).

Unemployment rate is defined as a percentage of unemployed workers in the total labor force. The rate is published monthly by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) which uses both the establishment data (captured by the Current Employment Statistics program) and household surveys (Current Population Survey) to generate the labor market data ( Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 2020b ). A person is unemployed if they were not employed during the survey’s reference week and who had actively searched for a job in the 4-week period ending with the reference week, and were presently available for work ( BLS, 2020b ).

Caused by the COVID-19, the unemployment rate reached a peak in April 2020 at 14.7% nationwide, an unprecedented joblessness amount since employment data collection started in 1948. It exceeded the previous peaks during the Great Recession and after ( Falk et al., 2020 ). The official unemployment rate may have been over 20%, since the actual level of joblessness could have been understated due to local unemployment rate measurement errors ( Coibion et al., 2020 ). In addition, the unemployment rate was understated due to a geographically widespread misclassification of those who was not at work but considered employed and non-inclusion of labor force non-participants who still counted as employed ( Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 2020a ). Further, the COVID-19 caused the rapid rate of change in unemployment at the national level challenging accurate forecast of the monthly unemployment rate ( Weinstock, 2020 ).

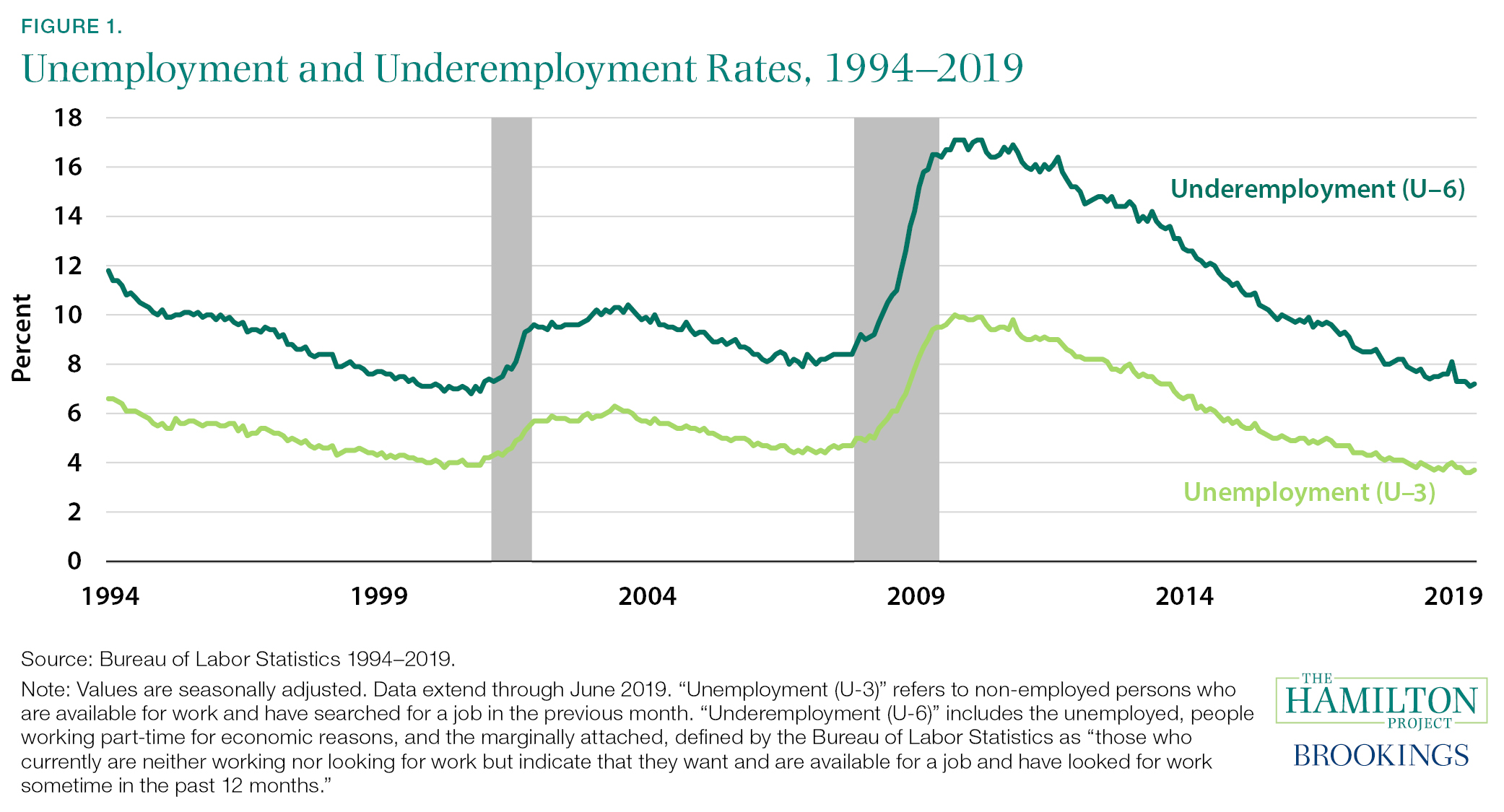

Overall, current unemployment (using the most recently available county-level data at the time of writing for December 2020) is still elevated and is almost twice as high as it was back in February 2020 which represented the business cycle peak with the peak of payroll employment. March 2020 was the first month of the subsequent current economic recession as declared by The National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER, 2020) caused by the COVID-19 pandemic which turned out the worst downturn after the Great Recession. As Fig. 1 shows using the Current Population Survey data (Series ID: LNS14000000) from the BLS, during the prior recessions the unemployment rate rose gradually reaching its peak, and in the pandemic-caused recession it increased unprecedentedly to its peak over one month, from March 2020 to April 2020 by 10.3% (from 3.5% in February 2020 to 4.4% in March 2020 to 14.7% in April). After that, the rate declined as workers continued to return to work to 6.3% in December 2020.

U.S. Historical unemployment rate for workers 16 years and over, January 1948 to December 2020, % (seasonally adjusted).

Some communities can absorb the impact of economic downturns due to more favorable economic and social factors protecting residents from adversity. Yet other communities are witnessing the effect of rising unemployment in the time of COVID-19. Loss of income and livelihood has further effects: as wages drop, more people are forced into poverty while simultaneously people's health is impacted. Unemployment impacts all-cause mortality. Fig. 2 presents the dynamics of unemployment distribution across counties in TN for the selected months. Shown are pre-COVID-19 unemployment rates as of August 2019 ( Fig. 2 a), followed by May 2020 ( Fig. 2 b) where even the lowest levels of unemployment exceed the highest rates of the pre-pandemic period even in wealthy counties around Nashville (seen in the legend entries), August 2020 ( Fig. 2 c), and September 2020 ( Fig. 2 d). The overall unemployment abates somewhat during the later stage, and the general spatial pattern resembles that of the pre-COVID-19 period with higher unemployment concentrated in the southwestern corner of the state around Memphis.

Dynamics of unemployment rate across counties in TN for selected months: (a) August 2019, (b) May 2020; (c) August 2020; (d) September 2020.

1.1.3. Study area

Tennessee is home to large cities including Nashville (the county seat), Memphis, Knoxville and Chattanooga. Despite urban diversified economy, there was a steep decline in the number of international and domestic tourists impacting urban economy. Among cities listed above, Memphis, located in Shelby County, is a shrinking city with a declining population base. Urban shrinkage makes cities more vulnerable due to very negative impacts on urban economy. Shrinking cities are characterized by higher unemployment rates, depopulation (as people with higher economic and social status leave elsewhere), and a higher share of older people (increasing a share of individuals with underlying health conditions) ( Haase et al., 2014 ; Hartt 2019 ; Hoekveld 2012 ; Krzysztofik et al., 2020 ). The shrinking cities have higher exposure to extreme socioeconomic phenomena, including financial stress due to the decreases in the city’s budget. Decreasing budget in its turn has further urban development implications since implementation of some plans deemed of lesser priority such as environmental and cultural may be delayed and cancelled altogether ( Kunzmann, 2020 ; Sharifi and Khavarian-Garmsir, 2020 ).

Tennessee is one of the US southern Sunbelt states which had infection surges since summer 2020 due to the aggressive push for economy opening by then-President Trump administration. The pandemic has affected unemployment for every state in the United States ( Falk et al., 2020 ). Fig. 3 portrays selected industries impacted by the economic recession in Tennessee using seasonally adjusted data on employees on nonfarm payrolls for November 2019 (as a base period), September–November 2020. Unemployment rates concentrate disproportionately in sectors providing in-person non-essential services where some demographic groups are overrepresented. This results in substantially higher unemployment rates for those workers ( Cortes and Forsythe, 2020 ; Fairlie, 2020 ). Accordingly, it can be seen in Fig. 3 that in Tennessee, among the reported industries, leisure and hospitality has suffered the most, followed by jobs in government, education and health services, professional and business services, and trade, transportation, utilities. There was a slight increase in jobs in financial activities from 2019 to 2020 ( Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), 2020a ). The hardest hit industries tend to employ demographic groups such as women, minorities, low-income workers, and younger workers who have experienced greater job losses ( Murray and Olivares, 2020 ).

Employees on nonfarm payrolls by selected industry sector, seasonally adjusted, in TN.

2. Materials and methods

In the absence of fine-scale monthly data on employment and unemployment, we sourced county-level data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) to track monthly changes in employment and unemployment in Tennessee (retrieved from https://www.bls.gov/lau/ ). Labor force data were extracted from this official primary source.

We used a comparative assessment approach to analyze the COVID-19-based labor market outcomes including the rates of COVID-19-related employment and unemployment attributable to social disadvantage conditions. For this, we stratify data based on community disadvantage status, and combine data in a comparative assessment framework. We proceed and identify disadvantaged communities using the methodology described below. Next, we test the hypothesis that in areas with high social disadvantage where more essential workers are more likely to reside, the unemployment is higher while employment opportunities are lower by comparing unemployment and employment rates within these communities to those of more privileged communities.

3. Theory/calculation

We focus on the areas where the multiple risk factors identified in the recent literature co-locate spatially and term these places “ multi-dimensional social disadvantaged areas ”. We carried out a rigorous literature review of the variables to stand in for social disadvantage in this research. The following demographic and socio-economic factors have been selected to represent community’s vulnerability: (1) Minorities and ethnicity; (2) Crowded households; (3) Poverty; (4) Education; (5) Underlying medical conditions (obesity); and (6) Unemployment. For the 1st variable, minorities and ethnicity , we used percent minority population and Hispanic ethnicity as studies commonly use race and ethnicity as vulnerability metrics (as explained in Section 2 Background information). For the 2nd variable, crowded households , we used percent households that are multigenerational as an indicator of crowdedness, and thus, indicating area’s disadvantage with a high share of such households. For the 3rd variable, poverty , we chose percent of households below 100% of federal poverty level which is also known as the poverty line. It is an economic measure of income. The poverty guidelines are updated annually by the US Department of Health and Human Services to indicate the minimum income needed by a family for housing, food, clothing, transportation, and other basic necessities and to determine eligibility for certain welfare benefits. This measure was used because less affluent and less privileged households have fewer means and less access to various resources to cope with the effects of financial crises ( Pfeffer et al., 2013 ). Low-income households may be especially vulnerable to wage losses during the outbreak ( Qian and Fan, 2020 ). For the 4th variable, education , we used percent of population with less than high school diploma since lower educational attainment is an indicator of poverty and thus captures social disadvantage, while workers with better education have higher economic resilience when challenged with a large-scaled social shock ( Cutler et al., 2015 ; Kalleberg, 2011 ). For the 5th variable, underlying medical conditions , we used percent population with obesity as the top risk for COVID-19-related hospitalization. Supported by several lines of evidence, both domestically and internationally, obesity may predispose to more severe COVID-19 outcomes ( O’Hearn et al., 2021 ). Finally, for the 6th variable, unemployment , unemployment rate (averaged from August 2019 to January 2020 to adjust for seasonality) was used as a marker of overall vulnerability as it is linked to overall mortality. Further, regions with higher unemployment are more susceptible to business-cycle fluctuations, and thus, are more socially and economically vulnerable.

These socio-economic and demographic attributes (minority population, Hispanic ethnicity, federal poverty level, crowded households, adult obesity, lower educational attainment, and unemployment) have been used in this research to create a composite variable to represent a multi-dimensional social disadvantage (also referred to as vulnerability). Due to different variances in the original variables, we standardized them to prevent a disproportionate impact which may be caused by any one original variable with a large variance. The z-score transformation was applied by averaging the original variables and computing z scores with a mean of 0 and values ranging from negative to positive numbers ( Song et al., 2013 ).

Thus, the original variables were converted to z-scores to preserve the distribution of the raw scores and to ensure the equal contributions of the original variables. Next, we created a composite variable capturing a multi-dimensional social disadvantage. It was calculated by summing standardized z-scores of the original risk factors. The higher value can be interpreted as higher disadvantage while the lower value means more privileged communities. Based on the frequency distribution of values of the composite variable, we established a cut-off value for the composite variable to designate communities with high or low exposure to social disadvantage. We used the following method to determine the cut-off value of the composite variable. The values greater than 3.38 correspond to 1 standard deviation above the mean (or, the 88th percentile in the value distribution) indicating communities in the top 12 percent of social disadvantage and therefore, a higher share of factors contributing to disadvantage. This value was used to differentiate communities according to their disadvantage status. We identified twelve counties with high social disadvantage (N high = 12), and other counties represent more privileged communities (N low = 83). To test whether the taken approach correctly identifies disadvantaged communities, we conducted a Wilcoxon two-sample test for the variables of interest ( Table 1 ). We report the results of the estimates in the following section. The above socio-economic and demographic population characteristics come from the 2018 American Community Survey (ACS) 5-year data, an annual nationwide survey conducted by the US Census Bureau, available for various geographic units and applied for areal units within the study area ( U. S. Census Bureau, 2020 ).

Descriptive statistics.

The basic descriptive demographic and socio-economic characteristics of the TN population are shown in Table 1 . It includes the summaries for communities with high and low social disadvantage allowing to compare the variables of interest between these communities. The following variables are reported: percent African American, percent Hispanic, median income, percent of people over 25 years who are less than high school graduates, estimated percent of obese adults, percent households below 100% of federal poverty level, and percent of multi-generation households. The factors comprising social disadvantage were statistically significantly different than those extant in more privileged counties. Compared with the general TN population, the disadvantaged cohort was generally more likely to be of non-Hispanic Black race; more impoverished; with less educational attainment, more obese, and had more households with crowded conditions.

To visualize social disadvantage and show how it varies across the space, we used our sample of social disadvantage measurements and created a surface of social disadvantage within the study area using the Geographic Information System (GIS). The interpolated surface was derived from an Inverse Distance Weighted technique ( Watson and Philip, 1985 ). Fig. 4 presents the surface illustrating that both urban and rural counties in Tennessee are subject to social disadvantage.

Social disadvantage within the study area.

We examined how unemployment changed from August 2019 to December 2020. Currently, all counties have substantially higher unemployment compared with that prior to COVID. Fig. 5 presents the results of the Nonparametric One-Way ANOVA test showing the distribution of Wilcoxon scores for unemployment rate for all counties in Tennessee combined, regardless of social disadvantage status, for 17 months. A statistically significant difference is found for unemployment rates between the pre-COVID period and the period since April 2020, with current unemployment rates although decreased but still significantly higher compared with those prior to the recession.

Nonparametric One-Way ANOVA and distribution of Wilcoxon scores for unemployment rate for all counties combined for 17 months (August 2019–October 2020), regardless of social disadvantage status.

We compared employment and unemployment rates for Tennessee counties stratified by the type of social disadvantage separately for each month. Fig. 6 presents the average employment and unemployment rates by community disadvantage from August 2019 to December 2020 in a graphical form. The results of the non-parametric Wilcoxon test for employment and unemployment rates are presented in Table 2 . Pre-COVID and before the unemployment peak in April 2020, communities with high social disadvantage consistently had less jobs and greater unemployment, which we tested statistically and found a significant difference for both outcomes of the labor market between communities by their disadvantage status ( Table 2 ). Shown in Table 2 , in April and May 2020, during the peak of unemployment and immediately after, unemployment rates observed in both types of communities were high with no statistical difference. In June, the differences again became prominent, when there were more jobs available in more advantaged areas and employment rate remained consistently greater in areas with less disadvantage. Also in June, unemployment rate remained consistently greater in areas with higher disadvantage. This month saw the greater difference in both outcomes since the COVID-19 than pre-pandemic (supported by higher p-values). Compared with all TN population, residents of disadvantaged counties had less jobs available and were more likely to be unemployed during all periods except for April and May.

Mean employment and unemployment stratified by community disadvantage status.

Wilcoxon Two-Sample Test: Distribution of Wilcoxon scores in employment and unemployment rates by community disadvantage status by month (August 2019–December 2020).

We examined the percent change in both labor market outcomes. Fig. 7 presents the percent change in mean employment ( Fig. 7 a), and mean unemployment by community disadvantage ( Fig. 7 b). The percent change in employment and unemployment was relatively small in both types of community during the pre-COVID period. However, the overall fluctuations in both conditions were greater in communities with high social disadvantage (evidenced by a greater range between ups and downs for disadvantaged communities shown with the black-colored symbols). On the other hand, employment and unemployment were more stable in more privileged communities (shown with the grey-colored symbols in the Fig. 7 ). During the unemployment peak in April 2020, the change in percent employment was −11.5 points from the previous month even in more advantaged counties, while the unemployment in April increased by 10.42 percentage points in disadvantaged counties.

Percent change in (a) mean employment; (b) mean unemployment by community disadvantage.

We show how various factors of social disadvantage intersect and combined impact economic vulnerability measured by unemployment rate. Fig. 8 reports the link between unemployment and social disadvantage pre-COVID (unemployment rate was averaged over August 2019–January 2020 in Fig. 8 a), and during COVID (unemployment rate for November 2020 is shown in Fig. 8 b). During the COVID pandemic, its impact is even stronger as evidenced by a greater slope of the line of fit, larger coefficients, and a greater R-squared value ( Fig. 8 b). The strong relationship between these factors of social disadvantage and economic outcomes in COVID-19 might inform post-COVID recovery intervention strategies to reduce COVID-19-related economic vulnerability burdens. For example, in the light of findings on socio-economic and demographic subpopulations at a higher risk for economic damages, prioritization of economic relief distribution might be based on community disadvantage status targeting individuals from areas with existing inequalities to increase economic resilience of marginalized communities.

Unemployment and Social disadvantage: (a) pre-COVID (averaged August 2019–January 2020); (b) during COVID (November 2020).

5. Discussion

Current studies on the impacts of COVID-19 tend to focus on medical aspects while non-medical urban research mostly analyzes the role of environmental quality. To better understand the full effects of pandemics on communities and minimize the various impacts as well as to improved response, other aspects need to be examined. This includes studying less researched themes including socio-economic impacts consisting of both social impacts and social factors making individuals and communities less resilient and more vulnerable to the effects of the COVID. Additionally, economic impacts of the pandemic-caused recession so far remain relatively underexplored and need to be investigated ( Sharifi and Khavarian-Garmsir, 2020 ).

Communities are often severely segregated along wealth and social lines in developing and developed world ( Wilkinson et al., 2020 ). We study the role of social factors and the impact of the COVID on labor market conditions in Tennessee. Specifically, we studied the impacts of social environment on employment and unemployment through the concept of a multi-dimensional social disadvantage by using geospatial science.

A recent study identified factors which can make a community more vulnerable to the pandemic’s effects using as a case study the province of Silesia in Poland, one of the largest industrial and mining regions in Europe. Specialized functions such as mining-oriented industries, large care centers, polycentricity, and urban shrinkage make communities most at risk due to very negative impacts on urban economy ( Krzysztofik et al., 2020 ). Since vulnerability is always very context-specific, we found a combination of different causal factors of social disadvantage captured by a composite variable making communities most at risk during the COVID reflected in broader social and economic outcomes. In creating a composite variable to capture social disadvantage logically and meaningfully, the following variables were used: % African American, % Hispanic, % below 100% federal poverty level, % population with less than high school diploma (an indicator of poverty), % multi-generation households (an indicator of crowdedness), % estimated obese adults reporting to be obese with the BMI 30 or greater, % unemployed. The proposed method can be generalized beyond the study area and used as a tool by policy makers using consistent criteria for the delineation of areas carrying a greater risk for the more severe impact by the pandemic due to co-existence and co-location of the multi-dimensional social disadvantage factors which are more likely to experience further socio-economic disruptions.

Current urban research on COVID economic impacts found that some cities are more vulnerable than others and are most at risk. Cities with an undiversified economic structure with industries where a large number of workers are shoulder-to-shoulder share cramped spaces for a prolonged time and where social distancing is challenging (e.g., meat-packing and poultry processing plants), cities relying on tourism as well as cities that have large care centers, polycentric cities, and shrinking cities are the most vulnerable to negative impacts on urban economy. The urban hotel market, city tax revenues, citizens' income, tourism and hospitality, small- and medium sized firms, urban food supply chain, and migrant workers are all impacted ( Krzysztofik et al., 2020 ). Other recent studies similarly concluded that the COVID has revealed the extreme vulnerability of cities and urban areas disrupting tourism and affecting supply chains in cities ( Batty, 2020 ; Gössling et al., 2020 ). We support this statement but also find that rural areas can experience a broad range of social and economic damages related to COVID.

Before and during the COVID-19 period, money laundering, limitations of economic development, environmental pollution and uncontrolled deforestation, population displacement, institutional incompetence, and corruption of political elites have been debated including corruption and conflagration in Bucharest before the pandemic ( Creţan & O’Brien, 2020 ), as well as other contestations on selling masks and different medical products highlighted in different countries during the pandemic period. Following catalytic events, the affected community may respond to long-held concerns with demands to address these problems bringing about important changes to the systems. Marginalized stigmatized minorities may effectively overcome discriminatory laws, higher poverty and other constraints and influence public opinion and politics in their favor through collective action via various strategies including protests against corruption and the inaction of the political leaders in Romania in 2015 forcing the resignation of the Government, and protests in the US in the aftermath of police violence against black people have been documented ( Creţan & O’Brien, 2020 ; Fryer, 2019 ). During the COVID-19, the non-payment of wages and poor working and living conditions caused seasonal workers in Germany to protest against this unfair treatment, however, generating low coverage in the national press ( Mayer-Ahuja, 2020 ).

6. Conclusions

Some socio-economic and demographic conditions consistently and significantly impact some communities more often than others, particularly based on ethnic minority status, low income, and rural location. The conditions include systemic issues such as fragmented health care system (within which some individuals do not get health care in a timely fashion), racism and structural disparities in education, income, wealth, a consistent lack of economic opportunity, environmental factors, transportation and housing ( Petterson et al., 2020 ). These factors interact in complex ways resulting in persisting social environment-driven health and other inequalities which if left unaddressed will only increase.

Respectively, among policies goals across the Global North enhancing wellbeing and social mobility for disadvantaged and marginalized families, creating socially mixed, heterogeneous neighborhoods (that is, desegregation) is promoted to avoid spatial segregation based on racial and ethnic membership and class while supporting social cohesion ( Méreiné-Berki et al., 2021 ). Importantly, a marginalized community is not a homogeneous group as the lived experience of disadvantage within the communities is variegated: respectively, policies to improve socio-spatial integration and addressing the various causes of extreme poverty including social, economic, and cultural that improve social equity have been suggested since desegregation on its own is insufficient (( Méreiné-Berki et al., 2021 ). Sustainable planning may mitigate consequences of urban sprawl noted in the urban studies literature including urban blight which is the greatest in poorest areas entrapping the low-income residents in the inner city where they have only limited regional mobility and access to job opportunities at the urban edge. Understanding the links between a development of a metropolitan-wide blight remediation strategy toward a sustainable urban form and welfare enhancing among the disadvantaged populations needs to be further investigated.

During public health crises, the importance of the central role of the community has been highlighted especially when some state-based social services may be less available due to lockdown. Rather than inventing new solutions, voluntary informal social networks that have been generated by communities utilize local assets and resources ( Bear et al., 2020 ). Community-based initiatives may rely on the voluntary sector, faith- and charities-based organizations, and social enterprises for various services including help with visiting housebound people, or using them as a distribution hub for food distribution to families in need.

In conclusion, in this study, we situated the research on economic impacts of the COVID in the broader context of social disadvantage with findings both domestically and from other countries in line with those in our study. The earlier misleading view of the global epidemic representing a systematic disadvantage that may affect and limit everyone’s economic activity, with any socioeconomic status or from any geographic location, was rejected. Our finding indicates that certain factors may increase people's vulnerability to the financial stress related to COVID-19. We find support that the social distribution of economic vulnerability is magnified in regions with pre-existing social disparities, creating new forms of disparity ( Qian and Fan, 2020 ).

This work was supported by the UTHSC/UofM SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 Research CORNET (Collaboration Research Network) Award.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Anzhelika Antipova: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

- Antipova A. Analysis of Commuting Distances of Low-Income Workers in Memphis Metropolitan Area. TN. Sustainability. 2020; 12 (3):1209. doi: 10.3390/su12031209. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Banerjee S. In: Corona and work around the Globe. Eckert A., Hentschke F., editors. De Gruyter; Berlin, Boston: 2020. Skill, informality, and work in pandemic times: Insights from India; pp. III–IX. 2020. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barrero J.M., Bloom N., Davis S.J. COVID-19 also a reallocation shock. 2020. https://bfi.uchicago.edu/wp-content/uploads/BFI_WP_202059.pdf Working paper NO. 2020-59. At:

- Batty M. The coronavirus crisis: What will the post-pandemic city look like? Environ. Plan. B: Urban Anal. City Sci. 2020; 47 (4):547–552. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bear L., James D., Simpson N., Alexander E., Bhogal J.K., Bowers R.E., Cannell F., Lohiya A.G., Koch I., Laws M., Lenhard J.F., Long N.J., Pearson A., Samanani F., Wuerth M., Vicol O., Vieira J., Watt C., Whittle C., Zidaru-Barbulescu T. In: Corona and work around the Globe. Eckert A., Hentschke F., editors. De Gruyter; Berlin, Boston: 2020. Changing care networks in the United Kingdom; pp. VVIII–VVX. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bullard R. Westview Press; 2000. Dumping in Dixie: Race, class, and environmental quality, third edition: Bullard, Robert D.: 9780813367927: Amazon.com: Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Economic news release. State employment and unemployment —NOVEMBER 2020. December 18, 2020. 2020. https://www.bls.gov/news.release/laus.nr0.htm USDL-20-2267. At:

- Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Frequently asked questions: The impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on the Employment Situation for April 2020. 2020. https://www.bls.gov/cps/employment-situation-covid19-faq-april-2020.pdf May 8, 2020. At:

- Cai Q., et al. Obesity and COVID-19 severity in a designated hospital in shenzhen, China. Diabetes Care. 2020; 43 (7):1392–1398. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Coibion O., Gorodnichenko Y., Weber M. NBER working paper No. 27017. 2020. Labor markets during the COVID-19 crisis: A preliminary view. April 2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cortes G.M., Forsythe E. Upjohn Institute Working Paper; May 2020. The heterogeneous labor market impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Creţan R., Light D. COVID-19 in Romania: Transnational labour, geopolitics, and the Roma ‘outsiders. Eurasian Geography and Economics. 2020; 61 (4–5):559–572. [ Google Scholar ]

- Creţan R., Málovics G., Méreiné-Berki B. On the perpetuation and contestation of racial stigma: Urban Roma in a disadvantaged neighbourhood of Szeged. Geographica Pannonica. 2020; 24 (4):294–310. [ Google Scholar ]

- Creţan R., O’Brien T. Corruption and conflagration: (in)justice and protest in bucharest after the colectiv fire. Urban Geography. 2020; 41 (3):368–388. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2019.1664252. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cutler D.M., Huang W., Lleras-Muney A. When does education matter? The protective effect of education for cohorts graduating in bad times. Social Science & Medicine. 2015; 127 :63–73. 2015. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dey M., Loewenstein M.A. How many workers are employed in sectors directly affected by COVID-19 shutdowns, where do they work, and how much do they earn? Monthly Labor Review. April 2020 https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2020/article/covid-19-shutdowns.htm [ Google Scholar ]

- Eckert A., Hentschke F. Andreas Eckert and Felicitas Hentschke. De Gruyter; Berlin, Boston: 2020. Introduction: Corona and work around the Globe". Corona and work around the Globe; pp. XVII–XXII. 2020. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fairlie R. NBER working paper No. 27309, June 2020. 2020. The impact of covid-19 on small business owners: Evidence of early-stage losses from the April 2020 current population survey. [ Google Scholar ]

- Falk G., Carter J.A., Nicchitta I.A., Nyhof E.C., Romero P.D. Unemployment rates during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020. https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R46554.pdf Brief. Nov. 2020. Prepared by the Congressional Research Service (CRS). CRS Report R46554. At:

- Financial Times “Prospering in the pandemic: The top 100 companies,” 18 June. 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/844ed28c-8074-4856-bde0-20f3bf4cd8f0 At:

- Finch W.H., Hernández Finch M.E. Poverty and covid-19: Rates of incidence and deaths in the United States during the first 10 Weeks of the pandemic. Front. Sociol. 2020; 5 :1–10. June. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fryer R.G.J. An empirical analysis of racial differences in police use of force. Journal of Political Economy. 2019; 127 (3):1210–1261. [ Google Scholar ]

- Golestaneh L., et al. The association of race and COVID-19 mortality. EClinicalMedicine. 2020; 25 :100455. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goolsbee A., Syverson C. NBER working paper No. 27432. June 2020. Fear, lockdown, and diversion: Comparing drivers of pandemic economic decline 2020. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gössling S., Scott D., Hall C.M. Pandemics, tourism and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism. 2020:1–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gould E., Wilson V. 2020. Black workers face two of the most lethal preexisting conditions for coronavirus — racism and economic inequality. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gupta S., et al. NBER working paper No. 2780. May 2020. Effects of social distancing policy on labor market outcomes. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Haase A., Rink D., Grossmann K., Bernt M., Mykhnenko V. Conceptualizing urban shrinkage. Environment and Planning A. 2014; 46 (7):1519–1534. doi: 10.1068/a46269. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hajat A., Hsia C., O’Neill M.S. Vol. 2. Springer; 2015. Socioeconomic disparities and air pollution exposure: A global review; pp. 440–450. (Current environmental health reports). 4. 01-Dec. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Han J., Meyer B.D., Sullivan J.X. 2020. Income and poverty in the COVID-19 pandemic. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hartt M. The prevalence of prosperous shrinking cities. Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 2019; 109 (5):1651–1670. doi: 10.1080/24694452.2019.1580132. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hoekveld J.J. Time-space relations and the differences between shrinking regions. Built Environment. 2012; 38 (2):179–195. doi: 10.2148/benv.38.2.179. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jones B.L., Jones J.S. Gov. Cuomo is wrong, covid-19 is anything but an equalizer. Washington Post. 2020 https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2020/04/05/gov-cuomo-is-wrong-covid-19-is-anything-an-equalizer/ Accessed from. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kalleberg A.L. Russell Sage Foundation; New York, NY: 2011. Good jobs, bad jobs: The rise of polarized and precarious employment systems in the United States, 1970s-2000s. 2011. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kass D.A., Duggal P., Cingolani O. Obesity could shift severe COVID-19 disease to younger ages. Lancet. 2020; 395 (10236):1544–1545. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kiang M.V., Irizarry R.A., Buckee C.O., Balsari S. Every body counts: Measuring mortality from the COVID-19 pandemic. Annals of Internal Medicine. Sep. 2020:M20–M3100. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Krzysztofik R., Kantor-Pietraga I., Spórna T. Spatial and functional dimensions of the COVID-19 epidemic in Poland. Eurasian Geography and Economics. 2020; 61 (4–5):573–586. 10.1080/15387216.2020.1783337. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kunzmann K.R. Smart cities after covid-19: Ten narratives. disP - Plan. Rev. 2020; 56 (2):20–31. [ Google Scholar ]

- Malhotra K., Baltrus P., Zhang S., Mcroy L., Immergluck L.C., Rust G. Geographic and racial variation in asthma prevalence and emergency department use among Medicaid-enrolled children in 14 southern states. Journal of Asthma. 2014; 51 (9):913–921. Nov. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mayer-Ahuja N. In: Corona and work around the Globe. Eckert A., Hentschke F., editors. De Gruyter; Berlin, Boston: 2020. Solidarity’ in times of Corona? Of migrant Ghettos, low-wage heroines, and empty public coffers; pp. XVII–XXII. 2020. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Méreiné-Berki B., Málovics G., Crețan R. “You become one with the place”: Social mixing, social capital, and the lived experience of urban desegregation in the Roma community. Cities. 2021; 117 :103302. [ Google Scholar ]

- Millett G.A., et al. Assessing differential impacts of COVID-19 on black communities. Annals of Epidemiology. 2020; 47 :37–44. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murray S., Olivares E. 2020. Job losses during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic: Stay-at-home orders, industry composition, and administrative capacity (June 18, 2020) https://ssrn.com/abstract=3633502 Available at SSRN: [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- O’Hearn M., Liu J., Cudhea F., Micha R., Mozaffarian D. Coronavirus disease 2019 hospitalizations attributable to cardiometabolic conditions in the United States: A comparative risk assessment analysis. Journal of the American Heart Association. 2021 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.019259. https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/abs/10.1161/JAHA.120.019259 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Petterson S., Westfall J.M., Miller B.F. Well Being Trust; 2020. Projected deaths of despair from COVID-19. Well being trust. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pfeffer T., Danziger S., Schoeni R.F. Wealth disparities before and after the great recession. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2013; 650 (1):98–123. 2013. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Price-Haywood E.G., et al. Hospitalization and mortality among black patients and white patients with Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020; 382 (26):2534–2543. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Qian Y., Fan W. Research in social stratification and mobility. JAI Press; 2020. Who loses income during the COVID-19 outbreak? Evidence from China. [ Google Scholar ]

- Qualls N., et al. Community mitigation guidelines to prevent pandemic influenza — United States, 2017. MMWR. Recomm. Reports. Apr. 2017; 66 (1):1–34. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Selden T.M., Berdahl T.A. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities in health risk, employment, and household composition. Health Affairs. Sep. 2020; 39 (9):1624–1632. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sharifi A., Khavarian-Garmsir A.R. The COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on cities and major lessons for urban planning, design, and management. The Science of the Total Environment. 2020; 749 :1–3. 2020. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Song M.K., Lin F.C., Ward S.E., Fine J.P. Composite variables: When and how. Nursing Research. Jan. 2013; 62 (1):45–49. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- The National Bureau of Economic Research https://www.nber.org/cycles.html At:

- Thebault Reis, Tran Andrew Ba, Williams Vanessa. “African Americans are at higher risk of deathfrom coronavirus”, The Washington Post, 07-Apr-2020. The Washington Post. 2020 https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/04/07/coronavirus-is-infecting-killing-black-americans-an-alarmingly-high-rate-post-analysis-shows/ [ Google Scholar ]

- U. S. Census Bureau 2018 American Community Survey (ACS 2018 5-year) 2020. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data.html [Online]. Available:

- Wade L. An unequal blow. Science. 2020; 368 (6492):700–703. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Watson D.F., Philip G.M. A refinement of Inverse distance weighted interpolation. Geo-Processing. 1985; 2 :315–327. [ Google Scholar ]

- Weinstock L.R. Prepared by the congressional research service (CRS). CRS report IN11460. 2020. COVID-19: How quickly will unemployment recover? https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11460 AT: [ Google Scholar ]

- Wilkinson A., Ali H., Bedford J., Boonyabancha S., Connolly C., Conteh A., Dean L., Decorte F., Dercon B., Dias S., Dodman D., Duijsens R., D’Urzo S., Eamer G., Earle L., Gupte J., Frediani A.A., Hasan A., Hawkins K.…Whittaker L. Local response in health emergencies: Key considerations for addressing the COVID-19 pandemic in informal urban settlements. Environment and Urbanization. 2020; 32 (2):503–522. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/ [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Worldometers COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. 2020. https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/us/ At:

- Wu D., Yu L., Yang T., Cottrell R., Peng S., Guo W., Jiang S. The Impacts of Uncertainty Stress on Mental Disorders of Chinese College Students: Evidence From a Nationwide Study. Frontiers in Psychology. 2020; 11 :243. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

A Crisis of Long-Term Unemployment Is Looming in the U.S.

- Ofer Sharone

How biases trap qualified job seekers in a cycle of rejection — and how to help them break free.

The stigma of long-term unemployment can be profound and long-lasting. As the United States eases out of the Covid-19 pandemic, it needs better approaches to LTU compared to the Great Recession. But research shows that stubborn biases among hiring managers can make the lived experiences of jobseekers distressing, leading to a vicious cycle of diminished emotional well-being that can make it all but impossible to land a role. Instead of sticking with the standard ways of helping the LTU, however, a pilot program that uses a wider, sociologically-oriented lens can help jobseekers understand that their inability to land a gig isn’t their fault. This can help people go easier on themselves which, ultimately, can make it more likely that they’ll find a new position.

Covid-19 has ravaged employment in the United States, from temporary furloughs to outright layoffs. Currently, over 4 million Americans have been out of work for six months or more , including an estimated 1.5 million workers in white-collar occupations, according to my calculations. Though the overall unemployment rate is down from its peak last spring, the percent of the unemployed who are long-term unemployed (LTU) keeps increasing and is currently at over 40%, a level of LTU comparable to the Great Recession but otherwise unseen in the U.S. in over 60 years.

- Ofer Sharone is an expert on long-term unemployment and the author of the book Flawed System/Flawed Self: Job Searching and Unemployment Experiences (University of Chicago Press). Sharone received his PhD in sociology from the University of California Berkeley, his JD from Harvard Law School, and is currently an associate professor of sociology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Partner Center

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Featured articles

- Virtual Issues

- Browse content in B - History of Economic Thought, Methodology, and Heterodox Approaches

- Browse content in B4 - Economic Methodology

- B49 - Other

- Browse content in C - Mathematical and Quantitative Methods

- Browse content in C0 - General

- C01 - Econometrics

- Browse content in C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods and Methodology: General

- C10 - General

- C11 - Bayesian Analysis: General

- C12 - Hypothesis Testing: General

- C13 - Estimation: General

- C14 - Semiparametric and Nonparametric Methods: General

- C15 - Statistical Simulation Methods: General

- Browse content in C2 - Single Equation Models; Single Variables

- C21 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions

- C22 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes

- C23 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- C26 - Instrumental Variables (IV) Estimation

- Browse content in C3 - Multiple or Simultaneous Equation Models; Multiple Variables

- C31 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions; Social Interaction Models

- C33 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- C34 - Truncated and Censored Models; Switching Regression Models

- C35 - Discrete Regression and Qualitative Choice Models; Discrete Regressors; Proportions

- C36 - Instrumental Variables (IV) Estimation

- Browse content in C4 - Econometric and Statistical Methods: Special Topics

- C41 - Duration Analysis; Optimal Timing Strategies

- C44 - Operations Research; Statistical Decision Theory

- Browse content in C5 - Econometric Modeling

- C50 - General

- C51 - Model Construction and Estimation

- C52 - Model Evaluation, Validation, and Selection

- C53 - Forecasting and Prediction Methods; Simulation Methods

- C55 - Large Data Sets: Modeling and Analysis

- C57 - Econometrics of Games and Auctions

- Browse content in C6 - Mathematical Methods; Programming Models; Mathematical and Simulation Modeling

- C61 - Optimization Techniques; Programming Models; Dynamic Analysis

- C62 - Existence and Stability Conditions of Equilibrium

- C63 - Computational Techniques; Simulation Modeling

- C67 - Input-Output Models

- Browse content in C7 - Game Theory and Bargaining Theory

- C70 - General

- C72 - Noncooperative Games

- C73 - Stochastic and Dynamic Games; Evolutionary Games; Repeated Games

- C78 - Bargaining Theory; Matching Theory

- Browse content in C8 - Data Collection and Data Estimation Methodology; Computer Programs

- C83 - Survey Methods; Sampling Methods

- Browse content in C9 - Design of Experiments

- C90 - General

- C91 - Laboratory, Individual Behavior

- C92 - Laboratory, Group Behavior

- C93 - Field Experiments

- Browse content in D - Microeconomics

- Browse content in D0 - General

- D01 - Microeconomic Behavior: Underlying Principles

- D02 - Institutions: Design, Formation, Operations, and Impact

- D03 - Behavioral Microeconomics: Underlying Principles

- Browse content in D1 - Household Behavior and Family Economics

- D11 - Consumer Economics: Theory

- D12 - Consumer Economics: Empirical Analysis

- D13 - Household Production and Intrahousehold Allocation

- D14 - Household Saving; Personal Finance

- D15 - Intertemporal Household Choice: Life Cycle Models and Saving

- D18 - Consumer Protection

- Browse content in D2 - Production and Organizations

- D21 - Firm Behavior: Theory

- D22 - Firm Behavior: Empirical Analysis

- D23 - Organizational Behavior; Transaction Costs; Property Rights

- D24 - Production; Cost; Capital; Capital, Total Factor, and Multifactor Productivity; Capacity

- D25 - Intertemporal Firm Choice: Investment, Capacity, and Financing

- D29 - Other

- Browse content in D3 - Distribution

- D30 - General

- D31 - Personal Income, Wealth, and Their Distributions

- Browse content in D4 - Market Structure, Pricing, and Design

- D40 - General

- D41 - Perfect Competition

- D42 - Monopoly

- D43 - Oligopoly and Other Forms of Market Imperfection

- D44 - Auctions

- D47 - Market Design

- Browse content in D5 - General Equilibrium and Disequilibrium

- D50 - General

- D51 - Exchange and Production Economies

- D52 - Incomplete Markets

- D53 - Financial Markets

- D57 - Input-Output Tables and Analysis

- D58 - Computable and Other Applied General Equilibrium Models

- Browse content in D6 - Welfare Economics

- D60 - General

- D61 - Allocative Efficiency; Cost-Benefit Analysis

- D62 - Externalities

- D63 - Equity, Justice, Inequality, and Other Normative Criteria and Measurement

- D64 - Altruism; Philanthropy

- Browse content in D7 - Analysis of Collective Decision-Making

- D70 - General

- D71 - Social Choice; Clubs; Committees; Associations

- D72 - Political Processes: Rent-seeking, Lobbying, Elections, Legislatures, and Voting Behavior

- D73 - Bureaucracy; Administrative Processes in Public Organizations; Corruption

- D74 - Conflict; Conflict Resolution; Alliances; Revolutions

- D78 - Positive Analysis of Policy Formulation and Implementation

- Browse content in D8 - Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty

- D80 - General

- D81 - Criteria for Decision-Making under Risk and Uncertainty

- D82 - Asymmetric and Private Information; Mechanism Design

- D83 - Search; Learning; Information and Knowledge; Communication; Belief; Unawareness

- D84 - Expectations; Speculations

- D85 - Network Formation and Analysis: Theory

- D86 - Economics of Contract: Theory

- Browse content in D9 - Micro-Based Behavioral Economics

- D90 - General

- D91 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making

- D92 - Intertemporal Firm Choice, Investment, Capacity, and Financing

- Browse content in E - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Browse content in E0 - General

- E03 - Behavioral Macroeconomics

- Browse content in E1 - General Aggregative Models

- E10 - General

- E12 - Keynes; Keynesian; Post-Keynesian

- E13 - Neoclassical

- E17 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Investment, Labor Markets, and Informal Economy

- E20 - General

- E21 - Consumption; Saving; Wealth

- E22 - Investment; Capital; Intangible Capital; Capacity

- E23 - Production

- E24 - Employment; Unemployment; Wages; Intergenerational Income Distribution; Aggregate Human Capital; Aggregate Labor Productivity

- E25 - Aggregate Factor Income Distribution

- E26 - Informal Economy; Underground Economy

- E27 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E3 - Prices, Business Fluctuations, and Cycles

- E30 - General

- E31 - Price Level; Inflation; Deflation

- E32 - Business Fluctuations; Cycles

- Browse content in E4 - Money and Interest Rates

- E40 - General

- E41 - Demand for Money

- E42 - Monetary Systems; Standards; Regimes; Government and the Monetary System; Payment Systems

- E43 - Interest Rates: Determination, Term Structure, and Effects

- E44 - Financial Markets and the Macroeconomy

- E49 - Other

- Browse content in E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and Credit

- E50 - General

- E51 - Money Supply; Credit; Money Multipliers

- E52 - Monetary Policy

- E58 - Central Banks and Their Policies

- Browse content in E6 - Macroeconomic Policy, Macroeconomic Aspects of Public Finance, and General Outlook

- E60 - General

- E61 - Policy Objectives; Policy Designs and Consistency; Policy Coordination

- E62 - Fiscal Policy

- E65 - Studies of Particular Policy Episodes

- Browse content in E7 - Macro-Based Behavioral Economics

- E70 - General

- E71 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on the Macro Economy

- Browse content in F - International Economics

- Browse content in F1 - Trade

- F10 - General

- F11 - Neoclassical Models of Trade

- F12 - Models of Trade with Imperfect Competition and Scale Economies; Fragmentation

- F13 - Trade Policy; International Trade Organizations

- F14 - Empirical Studies of Trade

- F15 - Economic Integration

- F16 - Trade and Labor Market Interactions

- F17 - Trade Forecasting and Simulation

- F18 - Trade and Environment

- F19 - Other

- Browse content in F2 - International Factor Movements and International Business

- F22 - International Migration

- F23 - Multinational Firms; International Business

- Browse content in F3 - International Finance

- F30 - General

- F31 - Foreign Exchange

- F32 - Current Account Adjustment; Short-Term Capital Movements

- F33 - International Monetary Arrangements and Institutions

- F34 - International Lending and Debt Problems

- F36 - Financial Aspects of Economic Integration

- Browse content in F4 - Macroeconomic Aspects of International Trade and Finance

- F40 - General

- F41 - Open Economy Macroeconomics

- F42 - International Policy Coordination and Transmission

- F43 - Economic Growth of Open Economies

- F44 - International Business Cycles

- Browse content in F5 - International Relations, National Security, and International Political Economy

- F50 - General

- F53 - International Agreements and Observance; International Organizations

- Browse content in F6 - Economic Impacts of Globalization

- F60 - General

- F63 - Economic Development

- F64 - Environment

- F65 - Finance

- Browse content in G - Financial Economics

- Browse content in G0 - General

- G01 - Financial Crises

- G02 - Behavioral Finance: Underlying Principles

- Browse content in G1 - General Financial Markets

- G10 - General

- G11 - Portfolio Choice; Investment Decisions

- G12 - Asset Pricing; Trading volume; Bond Interest Rates

- G13 - Contingent Pricing; Futures Pricing

- G14 - Information and Market Efficiency; Event Studies; Insider Trading

- G15 - International Financial Markets

- G18 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G2 - Financial Institutions and Services

- G20 - General

- G21 - Banks; Depository Institutions; Micro Finance Institutions; Mortgages

- G22 - Insurance; Insurance Companies; Actuarial Studies

- G23 - Non-bank Financial Institutions; Financial Instruments; Institutional Investors

- G24 - Investment Banking; Venture Capital; Brokerage; Ratings and Ratings Agencies

- G28 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G3 - Corporate Finance and Governance

- G30 - General

- G31 - Capital Budgeting; Fixed Investment and Inventory Studies; Capacity

- G32 - Financing Policy; Financial Risk and Risk Management; Capital and Ownership Structure; Value of Firms; Goodwill

- G33 - Bankruptcy; Liquidation

- G34 - Mergers; Acquisitions; Restructuring; Corporate Governance

- G38 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G4 - Behavioral Finance

- G40 - General

- G41 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making in Financial Markets

- Browse content in H - Public Economics

- Browse content in H0 - General

- H00 - General

- Browse content in H1 - Structure and Scope of Government

- H11 - Structure, Scope, and Performance of Government

- Browse content in H2 - Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H20 - General

- H21 - Efficiency; Optimal Taxation

- H23 - Externalities; Redistributive Effects; Environmental Taxes and Subsidies

- H24 - Personal Income and Other Nonbusiness Taxes and Subsidies; includes inheritance and gift taxes

- H25 - Business Taxes and Subsidies

- H26 - Tax Evasion and Avoidance

- Browse content in H3 - Fiscal Policies and Behavior of Economic Agents

- H30 - General

- H31 - Household

- Browse content in H4 - Publicly Provided Goods

- H41 - Public Goods

- Browse content in H5 - National Government Expenditures and Related Policies

- H50 - General

- H51 - Government Expenditures and Health

- H52 - Government Expenditures and Education

- H53 - Government Expenditures and Welfare Programs