Learn more about Charles Dickens:

- Dickens Fast Facts

- Dickens Biography

- Dickens' Novels

- Dickens' Characters

- Illustrating Dickens

- Dickens' London

- Mapping Dickens

- Dickens & Christmas

- Family and Friends

- Dickens in America

- Dickens' Journalism

- Dickens on Stage

- Dickens on Film

- Reading Dickens

- Dickens Glossary

- Dickens Quotes

- Bibliography

- Dickens Collection

- About this Site

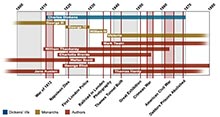

Dickens Timelines

Discover Dickens' life and work depicted graphically .

Catherine Dickens

Catherine (Hogarth) Dickens (1815-1879) - Charles Dickens' wife, with whom he fathered 10 children. She was born in Scotland on May 19, 1815 and came to England with her family in 1834. Catherine was the daughter of George Hogarth , editor of the Evening Chronicle where Dickens was a young journalist. They were married on April 2, 1836 in St. Luke's Church, Chelsea and honeymooned in Chalk, near Chatham.

Charles was undoubtably in love at the outset but his feelings for Catherine wained as the family grew. With the birth of their last child in 1852 Dickens found Catherine an increasingly incompetent mother and housekeeper ( Johnson, 1952, p. 905-909 ) . Their separation, in 1858, was much publicized and rumors of Dickens unfaithfulness abounded, which he vehemently denied in public. Dickens and Catherine had little correspondence after the break, Catherine moving to a house in London with oldest son, Charley , and Dickens retreating to Gads Hill in Kent with Catherine's sister, Georgina , and all of the children except Charlie remaining with him. On her deathbed in 1879 she gave her collection of Dickens' letters to daughter Kate instructing her to " Give these to the British Museum, that the world may know he loved me once " ( Schlicke, 1999, p. 153-157 ) .

Katherine is buried at Highgate Cemetery , London.

Read a letter from Dickens to John Forster concerning separation from Catherine.

What Shall We Have for Dinner?

Around 1850 Catherine released a collection of recipes and bills of fare for dinners for from two to eighteen people. The book, published by Bradbury and Evans, was called What Shall We Have for Dinner? and was written under the pen name Lady Maria Clutterbuck. Charles Dickens wrote the introduction using Maria's voice ( Nayder, 2011, p. 186-189 ) . The book is referred to as the source of Christmas dinner in Thomas Keneally's novel The Dickens Boy .

Amazon.com: The Other Dickens: A Life of Catherine Hogarth by Lillian Nayder

The Life of Charles Dickens

An illustrated hypertext biography of charles dickens, childhood and education.

- The Law and Early Jounalism

- Early Novels

- Middle Years

- Later Years

At this point the family consisted of Charles, older sister Fanny , younger brothers Alfred and Frederick , and younger sister Letitia . Everyone except Charles and Fanny went to live in the Marshalsea with their parents. Fanny was boarding at the Royal Academy of Music, and Charles initially lodged with a landlady in Camden Town in north London. This proved to be too long a walk every day to the blacking factory and his family in the Marshalsea, so a room was found for him on Lant Street in Southwark near the prison.

Young Charles, who dreamed of growing up a gentleman, found these dreams dashed working alongside common boys at the blacking factory and later wrote "It is wonderful to me how I could have been so easily cast away at such an age." Dickens shared this painful part of his childhood through the story of David Copperfield although no one realized it was autobiographical until related by biographer John Forster after Dickens' death ( Forster, 1899, v. 1, p. 22-39 ) .

Charles was to further his education at Wellington House Academy , a school run by the harsh schoolmaster William Jones , a man who delighted in corporal punishment and who Dickens later described as " by far the most ignorant man I have ever had the pleasure to know ". Charles would spend nearly three years, aged 12-15, at Wellington House, leaving in the spring of 1827 ( Slater, 2009, p. 25-27 ) . Many of his experiences at school, and the masters who taught there, would later find their way into his fiction.

The Law and Early Journalism

Charles had been fascinated with the theatre since childhood and often attended the theatre to break the monotony of reporting on parliamentary proceedings. He wrote to George Bartley, manager of the Covent Garden Theatre, in 1832 asking for an audition, which was granted. On the day of the audition Charles was ill with a bad cold and inflammation of the face and missed the appointment. He wrote to Bartley explaining the illness and that he would apply for another audition next season. He would later marvel at how near he came to a very different sort of life ( Ackroyd, 1990, p. 139-140 ) .

Dickens, writing feverishly, as well as holding down the job of a reporter, now found himself in the throes of romance. He became a regular visitor to the Hogarth household and soon proposed marriage, which Catherine quickly accepted ( Slater, 2009, p. 47 ) . They were married at St. Luke's church, Chelsea on April 2, 1836. Two months previous his collection of short stories was published in book form by John Macrone entitled Sketches by Boz with illustrations by popular artist George Cruikshank ( Ackroyd, 1990, p. 174 ) . Dickens' pseudonym Boz came from his younger brother Augustus's through-the-nose pronunciation of his own nickname, Moses.

The Early Novels

Upon returning home he penned the promised travel book, American Notes , a rather unflattering description of America, and followed that with Martin Chuzzlewit , published in monthly parts, in which the protagonist goes to America and is subjected to the same sort of puffed up, mercenary people Dickens found there. The story was not well received and did not sell well ( Patten, 1978, p. 133 ) . Neither had Barnaby Rudge ( Schlicke, 1999, p. 33 ) , and Dickens felt that perhaps his lamp had gone out.

Dickens found himself in dire financial straits. He had borrowed heavily from his publishers for the American trip and his family continued to grow with their fifth child, son Francis , on the way. His feckless father was borrowing money in Charles' name behind his back. He needed an idea for a new book that would satisfy his pecuniary problems ( Slater, 2009, p. 215-220 ) .

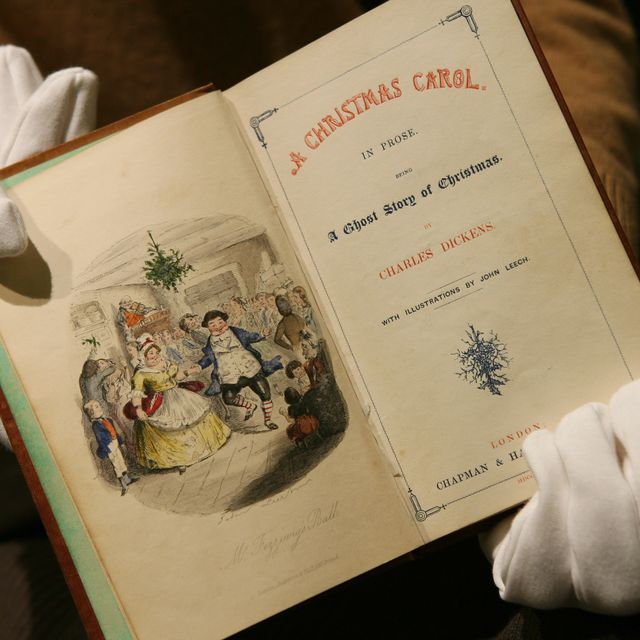

The seeds for the story that became A Christmas Carol were planted in Dickens' mind during a trip to Manchester to deliver a speech in support of education. Thoughts of education as a remedy for crime and poverty, along with scenes he had recently witnessed at the Field Lane Ragged School , caused Dickens to resolve to " strike a sledge hammer blow " for the poor ( Ackroyd, 1990, p. 408-409 ) . As the idea for the story took shape and the writing began in earnest, Dickens became engrossed in the book. He wrote that as the tale unfolded he " wept and laughed, and wept again' and that he 'walked about the black streets of London fifteen or twenty miles many a night when all sober folks had gone to bed " ( Forster, 1899, v. 1, p. 326 ) . Dickens was at odds with Chapman and Hall over the low receipts from Martin Chuzzlewit and decided to self-publish the book, overspending on color illustrations and lavish binding and then setting the cost low so that everyone could afford it ( Slater, 2009, p. 220 ) . The book was an instant success but royalties were low after production costs were paid .

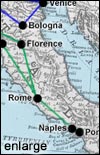

Serialization of Martin Chuzzlewit came to a conclusion in July, 1844, and Dickens conceived of the idea of another travel book; this time he would go to Italy ( Ackroyd, 1990, p. 426 ) . The family spent a year in Italy, first in Genoa, and then traveling through the southern part of the country. He wrote the second of his Christmas Books, The Chimes ( Slater, 2009, p. 230-231 ) , while in Genoa and sent his adventures home in the form of letters which were published in the Daily News . These were collected into a single volume entitled Pictures from Italy in May, 1846 ( Davis, 1999, p. 318 ) .

During the 1840s Dickens, with a troupe of friends and family in tow, began acting in amateur theatricals in London and across Britain. Charles worked tirelessly as actor and stage manager and often adjusted scenes, assisted carpenters, invented costumes, devised playbills, and generally oversaw the entire production of the performances ( Forster, 1899, v. 1, p. 436 ) . The Dickens' amateur troupe even performed twice for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert ( Davis, 1999, p. 4 ) .

The Middle Years

In 1839 the Dickens family moved from Doughty Street to a larger home at Devonshire Terrace near Regent's Park . The family continued to grow with the addition of sons Alfred (1845), Sydney (1847), and Henry (1849).

Dickens continued to write a book for the Christmas season every year. After A Christmas Carol (1843), and The Chimes (1844), he followed with The Cricket on the Hearth (1845), The Battle of Life (1846), and The Haunted Man and the Ghost's Bargain (1848). All of these sold well at the time of publication but none endured as A Christmas Carol has ( Schlicke, 1999, p. 97 ) .

Dickens had begun writing an autobiography in the late 1840s that he shared with his friend and future biographer, John Forster ( Forster, 1899, v. 1, p. 22 ) . He found the writing too painful and opted instead to work his story into the fictional account of David Copperfield , which he later described as his personal favorite among his novels ( David Copperfield , p. xii ) . The story was serialized from May 1849 until November 1850. During the writing of Copperfield the tireless Dickens began another venture, a weekly magazine called Household Words . Charles worked as editor as well as contributor with additional pieces supplied by other writers. Also during the writing of Copperfield Catherine gave birth to a daughter, named for David Copperfield's wife Dora ( Slater, 2009, p. 312 ) . Dora , sickly from birth, died at 8 months old ( Ackroyd, 1990, p. 627-628 ) .

Dickens followed David Copperfield with what many consider one of his finest novels, Bleak House ( Davis, 1999, p. 35 ) . Dickens used his previous experience as a court reporter to tell the story of a prolonged case in the Courts of Chancery. During the writing of Bleak House Catherine gave birth to a son, Edward (1852), nicknamed Plorn. Edward would be last of Charles and Catherine's children and the family moved again, this time to Tavistock House . Following Bleak House Dickens serialized his next book, Hard Times , in his weekly magazine, Household Words . Following Hard Times Dickens returned to the painful childhood memory of his father's imprisonment for debt with the story of Little Dorrit . Amy Dorrit's father, William , was a prisoner in the Marshalsea debtor's prison and Amy was born there.

During the 1850s Charles and Catherine's marriage started to show signs of trouble. Dickens grew increasingly dissatisfied with Catherine whom, after giving birth to ten children, had grown quite stout and lethargic. She was increasingly unable to keep up with her energetic husband ( Schlicke, 1999, p. 155 ) . The problem came to a head when Dickens became enthralled with a young actress he met during one of his amateur theatricals, Ellen Ternan . Charles and Catherine were separated in 1858 and caused a public stir mostly contributed to by Dickens' desire to exonerate himself ( Johnson, 1952, p. 922-925 ) . All of the Dickens children, with exception of Charley , would live with their father, as would Catherine's sister, Georgina . The relationship with Ternan, the depth of which is still being debated ( Ackroyd, 1990, p. 914-918 ) , would continue the rest of Dickens' life.

Dickens and his children now moved into the mansion Gads Hill Place in Kent that he had purchased in 1856 near his childhood home of Chatham. As a boy, Dickens would walk by the impressive house, built in 1780, with his father who told him that with hard work he could someday live in such a splendid mansion ( Forster, 1899, v. 1, p. 6 ) . In 1864 Dickens received, from actor friend Charles Fechter, a two-story Swiss chalet that Dickens had installed across the road from Gads Hill with a tunnel under the road for access ( Ackroyd, 1990, p. 955-956 ) . Dickens wrote his his final works in his study on the top floor of the chalet.

The separation with Catherine also caused a rift between Dickens and his publishers, Bradbury and Evans . Bradbury and Evans also published the popular magazine Punch . When they refused to publish Dickens' personal statement , his explanation for the recent separation, Charles was furious and refused to have further dealings with them. He ceased publication of his weekly magazine, Household Words , continuing it under a new name, All the Year Round , and with his old publishers, Chapman and Hall ( Kaplan, 1988, p. 395-401 ) .

In the 1850s Dickens began reading excerpts of his books in public, first for charity, and, beginning in 1858, for profit. These readings proved extremely popular with the public and Dickens continued them for the rest of his life. The readings included excerpts from his Christmas books , David Copperfield , and Nicholas Nickleby , with A Christmas Carol , for which he wrote a condensed verion , and The Trial from Pickwick being the most popular ( Davis, 1999, p. 328 ) . He later included the dramatic murder of Nancy by Bill Sikes in Oliver Twist , the performance of which took a toll on Dickens' fragile health ( Johnson, 1952, p. 1144 ) .

The Later Years

In May, 1864, Dickens began publication of what would be his last completed novel. Published in monthly installments, Our Mutual Friend touches the familiar theme of the evils and corruption that the love of money brings. Poor health causing perhaps a stutter in his usual creative genius, Dickens found beginning the novel difficult, he wrote to Forster "Although I have not been wanting in industry, I have been wanting in invention" ( Letters, 1998, v. 10, p. 414 ) . After finally finding his footing, the monthly installments did not sell well despite a massive advertising blitz ( Patten, 1978, p. 307-308 ) .

On the 9th of June, 1865, traveling back from France with Ellen Ternan and her mother, and with the latest installment of Our Mutual Friend , the train in which they were traveling was involved in an accident in Staplehurst, Kent. Many were killed but Dickens and his companions escaped serious injury although Dickens was severely shaken. Three years later he wrote that he still experienced " vague rushes of terror even riding in hansom cabs " ( Johnson, 1952, p. 1018-1021 ) .

In the late 1850s Dickens began to contemplate a second visit to America , tempted by the money he could make by extending his public readings there. Despite pleas not to go from friends and family because of increasingly ill health ( Johnson, 1952, p. 1070 ) , he finally decided to go and arrived in Boston on November 19, 1867. The original plan called for a visit to Chicago and as far west as St. Louis. Because of ill health and bad weather this idea was scrapped and Dickens did not venture from the northeastern states ( Slater, 2009, p. 580 ) . He stayed for 5 months and gave 76 extremely popular performances for which he earned, after expenses, an incredible £19,000 ( Schlicke, 1999, p. 17 ) .

Dickens returned home in May, 1868, somewhat revitalized during the sea voyage, to a full load of work. He immediately plunged back into editing All the Year Round and, in October, began a farewell reading tour of Britain that included a new, very passionate, and physically taxing, performance of the murder of Nancy from Oliver Twist ( Davis, 1999, p. 353 ) .

Monthly publication of what was to be his last novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood , began in April, 1870. On the evening of June 8, 1870, Dickens, after working on the latest installment of Drood that morning in the chalet at Gads Hill , suffered a stroke and died the next day ( Ackroyd, 1990, p. 1076-1079 ) . The Mystery of Edwin Drood was exactly half finished and the mystery is unsolved to this day .

Dickens had wished to be buried, without fanfare, in a small cemetery in Rochester, but the Nation would not allow it. He was laid to rest in Poet's Corner, Westminster Abbey, the flowers from thousands of mourners overflowing the open grave ( Forster, 1899, v. 2, p. 513 ) .

Affiliate Links Disclosure The Charles Dickens Page is a member of affiliate programs at Amazon and Zazzle. This means that there are links that take users to sites where products that we recommend are offered for sale. If purchases are made on these sites The Charles Dickens Page receives a small commission.

A Tale of Two Cities

By charles dickens, a tale of two cities quiz 1.

- 1 Which two cities does the title refer to? London and Rome London and Paris Paris and Berlin London and Liverpool

- 2 Mr. Lorry is a barrister banker mail-coach driver solicitor

- 3 What is the message that Mr. Lorry sends via the messenger from Tellson's Bank? "recalled to life" "turn around" "abort mission" "continue as planned"

- 4 Who delivers the message to Mr. Lorry? Jerry Cruncher Dr. Manette Mr. Stryver Sydney Carton

- 5 What does Mr. Lorry tell Lucie Manette? She is to be tried for treason Her father is still alive She is his daughter She has inherited a large sum of money

- 6 How long was Doctor Manette imprisoned in the Bastille? a day 8 years 18 years 25 years

- 7 What does Gaspard write on the wall in wine and mud? wine blood his name i am hungry

- 8 What is the name that Defarge called himself and the other revolutionaries? Henri Jacques Baptiste Jann

- 9 What hobby did Dr. Manette pick up in prison? blacksmithing shoemaking novel-writing knitting

- 10 In what year does this novel begin? 1783 1775 1793 1767

- 11 What is Charles Darnay tried for in England? murder petty theft robbery treason

- 12 Why is Darnay acquitted? he proves that he is not French he resembles Carton he has an alibi he has a brilliant defense lawyer

- 13 Which gentleman does not want to marry Lucie? Mr. Lorry Mr. Stryver Sydney Carton Charles Darnay

- 14 Where do Darnay and Carton go together after the trial? the Manettes' house a tavern the Thames Paris

- 15 Where in London do the Manettes live? Fleet Street Whitefriars Soho Kensington

- 16 What does Miss Pross call Lucie Manette? "a golden-haired doll" "daughter" "my Ladybird" "sweetheart"

- 17 What is the most noticeable feature of the Manettes' house? the sunniness of the front room the musty smell the resounding echoes from the street its proximity to Temple Bar

- 18 How many books is the novel divided into? three five two seven

- 19 What does Lucie think the echoes in her house mean? she should shut her front door people are coming to intrude in her family's life the walls are too thin Soho is urbanizing very fast

- 20 What does "Monseigneur" mean? "my man" "the king" "the man" "my lord"

- 21 What does not happen on the Marquis's way home in his carriage? he refuses to erect a gravestone for a woman's husband he stops for a meal he runs over a little boy he gives Defarge a coin

- 22 Monseigneur is Dr. Manette's brother Charles Darnay's uncle Lucie's husband Charles Darnay's father

- 23 Charles Darnay does not help tumble the Bastille sympathize with the peasants's plight renounce his aristocratic title get persecuted by the French lower class

- 24 Monseigneur is murdered by Charles Darnay Mr. Lorry someone who calls himself Jacques Dr. Manette

- 25 Charles Darnay's moonlighting profession is street cleaner lawyer "resurrection-man" teacher

A Tale of Two Cities Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for A Tale of Two Cities is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

The Dover Road 1775

The driver carried a gun to protect himself from highwaymen and robbers.

Look at the Attorney generals opening and closing statements in ch 3 and list 3 examples of hyperbole. What is the effect of the hyperbole how much do you trust his statements?

What does Mr.lorry mean when he says that he is a man of business?

Mr. Lorry's initial introduction of himself as the representative of Tellson's Bank hence a man of business.

Study Guide for A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities study guide contains a biography of Charles Dickens, literature essays, a complete e-text, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About A Tale of Two Cities

- A Tale of Two Cities Summary

- A Tale of Two Cities Video

- Character List

Essays for A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens.

- Resurrection

- In the Absence of Hate

- Light vs. Dark Throughout A Tale of Two Cities

- Violence in A Tale of Two Cities

- Mirror Images: Sydney Carton and Charles Darnay

Lesson Plan for A Tale of Two Cities

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to A Tale of Two Cities

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- A Tale of Two Cities Bibliography

E-Text of A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities e-text contains the full text of A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens.

- Book I, Chapters 1-4

- Book I, Chapters 5-6

- Book II, Chapters 1-9

- Book II, Chapters 10-14

- Book II, Chapters 15-24

Wikipedia Entries for A Tale of Two Cities

- Introduction

- Publication history

Charles Dickens

- Classic Literature

- Classic Authors

Charles Dickens Biography

Dickens, Charles John Huffam (1812-1870), probably the best-known and, to many people, the greatest English novelist of the 19th century. A moralist, satirist, and social reformer, Dickens crafted complex plots and striking characters that capture the panorama of English society.

Dickens's novels criticize the injustices of his time, especially the brutal treatment of the poor in a society sharply divided by differences of wealth. But he presents this criticism through the lives of characters that seem to live and breathe. Paradoxically, they often do so by being flamboyantly larger than life: The 20th-century poet and critic T. S. Eliot wrote, "Dickens's characters are real because there is no one like them." Yet though these characters range through the sentimental, grotesque, and humorous, few authors match Dickens's psychological realism and depth. Dickens's novels rank among the funniest and most gripping ever written, among the most passionate and persuasive on the topic of social justice, and among the most psychologically telling and insightful works of fiction. They are also some of the most masterful works in terms of artistic form, including narrative structure, repeated motifs, consistent imagery, juxtaposition of symbols, stylization of characters and settings, and command of language.

Dickens established (and made profitable) the method of first publishing novels in serial instalments in monthly magazines. He thereby reached a larger audience including those who could only afford their reading on such an instalment plan. This form of publication soon became popular with other writers in Britain and the United States.

II Early Years

Dickens was born in Portsmouth, on England's southern coast. His father was a clerk in the British Navy pay office a respectable position, but with little social status. His paternal grandparents, a steward (property manager) and a housekeeper, possessed even less status, having been servants, and Dickens later concealed their background. Dickens's mother supposedly came from a more respectable family. Yet two years before Dickens's birth, his mother's father was caught embezzling and fled to Europe, never to return.

The family's increasing poverty forced Dickens out of school at age 12 to work in Warren's Blacking Warehouse, a shoe-polish factory, where the other working boys mocked him as "the young gentleman." His father was then imprisoned for debt. The humiliations of his father's imprisonment and his labor in the blacking factory formed Dickens's greatest wound and became his deepest secret. He could not confide them even to his wife, although they provide the unacknowledged foundation of his fiction.

Soon after his father's release from prison, Dickens got a better job as errand boy in law offices. He taught himself shorthand to get an even better job later as a court stenographer and as a reporter in Parliament. At the same time, Dickens, who had a reporter's eye for transcribing the life around him, especially anything comic or odd, submitted short sketches to obscure magazines. The first published sketch, "A Dinner at Poplar Walk" (later retitled "Mr. Minns and His Cousin") brought tears to Dickens's eyes when he discovered it in the pages of The Monthly Magazine in 1833. From then on his sketches, which appeared under the pen name "Boz" (rhymes with "rose") in The Evening Chronicle, earned him a modest reputation. Boz originated as a childhood nickname for Dickens's younger brother Augustus.

Dickens became a regular visitor at the home of George Hogarth, editor of The Evening Chronicle, and in 1835 became engaged to Hogarth's daughter Catherine. Publication of the collected Sketches by Boz in 1836 gave Dickens sufficient income to marry Catherine Hogarth that year. The marriage proved unhappy.

III Literary Career

Soon after Sketches by Boz appeared, the fledgling publishing firm of Chapman and Hall approached Dickens to write a story in monthly instalments. The publisher intended the story as a backdrop for a series of woodcuts by the then-famous artist Robert Seymour, who had originated the idea for the story. With characteristic confidence, Dickens, although younger and relatively unknown, successfully insisted that Seymour's pictures illustrate his own story instead. After the first instalment, Dickens wrote to the artist he had displaced to correct a drawing he felt was not faithful enough to his prose. Seymour made the change, went into his backyard, and expressed his displeasure by blowing his brains out. Dickens and his publishers simply pressed on with a new artist. The comic novel, The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, appeared serially in 1836 and 1837 and was first published in book form The Pickwick Papers in 1837.

The runaway success of The Pickwick Papers , as it is generally known today, clinched Dickens's fame. There were Pickwick coats and Pickwick cigars, and the plump, spectacled hero, Samuel Pickwick, became a national figure. Four years later, Dickens's readers found Dolly Varden, the heroine of Barnaby Rudge (1841), so irresistible that they named a waltz, a rose, and even a trout for her. The widespread familiarity today with Ebenezer Scrooge and his proverbial hard-heartedness from A Christmas Carol (1843) demonstrate that Dickens's characters live on in the popular imagination.

Dickens published 15 novels, one of which was left unfinished at his death. These novels are, in order of publication with serialization dates given first: The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club (1836-1837; 1837); The Adventures of Oliver Twist (1837-1839; 1838); The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby (1838-1839; 1839); The Old Curiosity Shop (1840-1841; 1841); Barnaby Rudge (1841); Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit (1843-1844; 1844); Dombey and Son (1846-1848; 1848); The Personal History of David Copperfield (1849-1850; 1850); Bleak House (1852-1853; 1853); Hard Times (1854); Little Dorrit (1855-1857; 1857); A Tale of Two Cities (1859); Great Expectations (1860-1861; 1861); Our Mutual Friend (1864-1865; 1865); and The Mystery of Edwin Drood (unfinished; 1870).

Through his fiction Dickens did much to highlight the worst abuses of 19th-century society and to prick the public conscience. But running through the main plot of the novels are a host of subplots concerning fascinating and sometime ludicrous minor characters. Much of the humor of the novels derives from Dickens's descriptions of these characters and from his ability to capture their speech mannerisms and idiosyncratic traits.

A Early Fiction

Dickens was influenced by the reading of his youth and even by the stories his nursemaid created, such as the continuing saga of Captain Murderer. These childhood stories, as well as the melodramas and pantomimes he saw in the theater as a boy, fired Dickens's imagination throughout his life. His favorite boyhood readings included picaresque novels such as Don Quixote by Spanish writer Miguel de Cervantes and Tom Jones by English novelist Henry Fielding, as well as the Arabian Nights. In these long comic works, a roguish hero's exploits and adventures loosely link a series of stories.

The Pickwick Papers , for example, is a wandering comic epic in which Samuel Pickwick acts as a plump and cheerful Don Quixote, and Sam Weller as a cockney version of Quixote's knowing servant, Sancho Panza. The novel's preposterous characters, high spirits, and absurd adventures delighted readers.

After Pickwick, Dickens plunged into a bleaker world. In Oliver Twist , he traces an orphan's progress from the workhouse to the criminal slums of London. Nicholas Nickleby , his next novel, combines the darkness of Oliver Twist with the sunlight of Pickwick. Rascality and crime are part of its jubilant mirth.

The Old Curiosity Shop broke hearts across Britain and North America when it first appeared. Later readers, however, have found it excessively sentimental, especially the pathos surrounding the death of its child-heroine Little Nell. Dickens's next two works proved less popular with the public.

Barnaby Rudge , Dickens's first historical novel, revolves around anti-Catholic riots that broke out in London in 1780. The events in Martin Chuzzlewit become a vehicle for the novel's theme: selfishness and its evils. The characters, especially the Chuzzlewit family, present a multitude of perspectives on greed and unscrupulous self-interest. Dickens wrote it after a trip to the United States in 1842.

B Mature Fiction

Many critics have cited Dombey and Son as the work in which Dickens's style matures and he succeeds in bringing multiple episodes together in a tight narrative. Set in the world of railroad-building during the 1840s, Dombey and Son looks at the social effects of the profit-driven approach to business. The novel was immediately successful.

Dickens always considered David Copperfield to be his best novel and the one he most liked. The beginning seems to be autobiographical, with David's childhood experiences recalling Dickens's own in the blacking factory. The unifying theme of the book is the "undisciplined heart" of the young David, which leads to all his mistakes, including the greatest of them, his mistaken first marriage.

Bleak House ushers in Dickens's final period as a satirist and social critic. A court case involving an inheritance forms the mainspring of the plot, and ultimately connects all of the characters in the novel. The dominant image in the book is fog, which envelops, entangles, veils, and obscures. The fog stands for the law, the courts, vested interests, and corrupt institutions. Dickens had a long-standing dislike of the legal system and protracted lawsuits from his days as a reporter in the courts.

A novel about industry, Hard Times , followed Bleak House in 1854. In Hard Times , Dickens satirizes the theories of political economists through exaggerated characters such as Mr. Bounderby, the self-made man motivated by greed, and Mr. Gradgrind, the schoolmaster who emphasizes facts and figures over all else. In Bounderby's mines, lives are ground down; in Gradgrind's classroom, imagination and feelings are strangled.

The pervading image of Little Dorrit is the jail. Dickens's memory of his own father's time in debtors' prison adds an autobiographical touch to the novel. Little Dorrit also contains Dickens's invention of the Circumlocution Office, the archetype of all bureaucracies, where nothing ever gets done. Through this critique and others, such as the circular legal system in Bleak House , Dickens also investigated the ways in which art makes meaning and the workings of his own narrative style.

A Tale of Two Cities is set in London and Paris during the French Revolution (1789-1799). It stands out among the novels as a work driven by incident and event rather than by character and is critical both of the violence of the mob and of the abuses of the aristocracy, which prompted the revolution. The successful Tale of Two Cities was soon followed by Great Expectations , which marked a return to the more familiar Dickensian style of character-driven narrative. Its main character, Pip, tells his own story. Pip's "great expectations" are to lead an idle life of luxury. Through Pip, Dickens exposes that ideal as false.

Dickens's last complete novel is the dark and powerful Our Mutual Friend . A tale of greed and obsession, it takes place in an ill-lit and dirty London, with images of darkness and decay throughout. Only 6 of the 12 intended parts of Edwin Drood had been completed by the time Dickens died. He intended it as a mystery story concerning the disappearance of the title character.

IV Final Years

The end of Dickens's life was emotionally scarred by his separation from his dutiful wife, Catherine, as the result of his involvement with a young actress, Ellen Ternan. Catherine bore him ten children during their 22-year marriage, but he found her increasingly dull and unsympathetic. Against the advice of editors, Dickens published a letter vehemently justifying his actions to his readers, who would otherwise have known nothing about them.

Following the separation, Dickens continued his hectic schedule of novel, story, essay, and letter writing (his collected letters alone stretch thousands of pages); reform activities; amateur theatricals and readings; in addition to nightly social engagements and long midnight walks through London. His energy had always seemed to his friends inhuman, but he maintained this activity in his later years in disregard of failing health. Dickens died of a stroke shortly after his farewell reading tour, while writing The Mystery of Edwin Drood .

V Achievement

Dickens's social critique in his novels was sharp and pointed. As his biographer Edgar Johnson observed in Charles Dickens: His Tragedy and Triumph (1952), Dickens's criticism was aimed not just at "the cruelty of the workhouse and the foundling asylum, the enslavement of human beings in mines and factories, the hideous evil of slums where crime simmered and proliferated, the injustices of the law, and the cynical corruption of the lawmakers" but also at "the great evil permeating every field of human endeavour: the entire structure of exploitation on which the social order was founded."

British writer George Orwell felt that Dickens was not a revolutionary, however, despite his criticism of society's ills. Orwell points out that Dickens "has no constructive suggestions, not even a clear grasp of the nature of the society he is attacking, only an emotional perception that something is wrong." That instinctive feeling becomes so moving in the novels because Dickens made the injustices he hated concrete and specific, not abstract and general. His readers feel the abuses of 19th-century society as real through the life of his characters. Underlying and reinforcing that illusion of reality, however, is a rich and complicated system of symbolic imagery resulting from superb artistry.

Through his characters, Dickens also touched a range of readers, which was perhaps his greatest talent. As his friend John Forster wrote, his stories enthralled "judges on the bench and boys in the street" alike. The illiterate, often too poor to buy instalments themselves, pooled their pennies and got someone to read aloud to them.

Near the end of the serialization of The Old Curiosity Shop , crowds thronged to a New York pier to await the ship from London carrying the latest instalment. As it came to the dock people roared, "Is Little Nell dead?" The pathetic death of the novel's child-heroine, Nell Trent, became one of the most celebrated scenes in 19th-century fiction. Such public concern over Little Nell's end guaranteed that Dickens's social message would be heard, not only by his avid readers, but also by those in power.

Dickens was a careful craftsman, with a strong sense of design; his books were strictly outlined. Any current notions that Dickens's novels are long because he was paid by the word, or sloppy because he wrote them under pressure of monthly deadlines, are simply untrue. What organizes Dickens's stories is sometimes not apparent at first glance, although it makes sense in novels that emphasize character. It is the logic of psychology, the tensions and contradictions of our drives and emotions, which Dickens plumbed, laying side by side the best and the worst of the human heart. This is a very different logic from the order of realism that rests on common sense. Dickens detested common sense, seeing in its seeming obviousness a form of tyranny.

The theater was a crucial influence on Dickens's work. As a young man Dickens tried to go on stage, but he missed his audition because of a cold. Not only did Dickens later write comic plays, melodramas, and libretti (words for musical dramas), he was also often involved in amateur theatricals for good causes, and spent his last two decades reading his own stories to packed audiences. Dickens's readings were as much a sensation in England and America as was his writing, and they proved as profitable. The readings revealed the part of the man that made him a practiced magician and hypnotist as well.

Dickens's love of the theatrical makes his works lend themselves readily to media adaptations. Motion-picture or television versions exist for almost every one of them. A Christmas Carol was one of the earliest to be adapted, first appearing as the silent film Scrooge (1901), directed by Walter R. Booth. The most notable adaptations include A Christmas Carol (1938), directed by Edwin L. Marin and starring Reginald Owen, and, probably the most famous of all, A Christmas Carol (1951), directed by Brian Desmond Hart and starring Alastair Sim. A later production titled Scrooged (1988) was directed by Richard Donner and starred Bill Murray. David Lean directed the most famous of the many versions of Great Expectations (1946). The film Oliver! (1968), a musical based on Oliver Twist and directed by Carol Reed, won six Academy Awards. Nowadays people are probably more familiar with the many BBC television miniseries productions of Dickens's works.

Contributed By: Laurie Langbauer, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. Professor of English, University of North Carolina. Author of Novels of Everyday Life: The Series in English Fiction, 1850-1930.

Charles Dickens Knowledge Quiz

In honor of Charles Dickens, here is a little quiz about his life and work. This Charles Dickens knowledge quiz is going to be very informative and interesting as you take these questions. We hope you are able to answer most if not all the questions correctly about this legend. So, we should not waste time any further and jump into it. Best of luck to you with this test, guys.

Where was Dickens born?

London, England

Portsmouth, England

Edinburgh, Scotland

Cardiff, Wales

Rate this question:

How many children did Dickens have?

Ten Children

Twelve Children

Six Children

Four Children

Which of these titles did Dickens write?

Martin Cheesewiz

Great Exaltations

The Prince and The Pauper

Barnaby Rudge

Our Mutual Friend

The Mystery of Satis House

Dombey and Son

The Life and Adventures of Thomas Knuckleboy

Which of these Dickens heroes recieves a large fortune from a mysterious benefactor?

Eugene Wrayburn

Arthur Clennam

Philip Pirrip "Pip"

Nicholas Nickleby

Which of these Dickens heroines was born and raised in debtors' prison?

Bella Wilfur

Esther Summerson

Estella Havisham

How many spirits visit Ebenezer Scrooge in Dickens' famous work A Christmas Carol?

Two Spirits

Five Spirits

Three Spirits

A character in the TV miniseries adaptation of Elizabeth Gaskell's Cranford recommends his favorite Dickens novel and says, "I defy you not to roar!" Which novel is he speaking about?

The Pickwick Papers

Oliver Twist

Martin Chuzzlewit

The Old Curiosity Shop

Which Bleak House character uses phrases such as "brimstone beast" and "shake me up"?

Mr. Smallweed

Mr. Tulkinghorn

Which of these surnames was not used by Charles Dickens in one of his novels

Pennyfeather

Which famous children's author was once an unwanted houseguest at Dickens' house?

Beatrix Potter

Lewis Carroll

J.M. Barrie

Hans Christian Andersen

How old was Charles Dickens when he died?

75 years old

40 years old

58 years old

48 years old

Which of these was a pen name occasionally used by Dickens?

What was the name of charles dickens' wife, in which year was charles dickens born, what was dickens' full name .

Charles John Harmon Dickens

Charles Joseph Hughes Dickens

Charles Oliver Nicholas Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens

Quiz Review Timeline +

Our quizzes are rigorously reviewed, monitored and continuously updated by our expert board to maintain accuracy, relevance, and timeliness.

- Current Version

- May 21, 2023 Quiz Edited by ProProfs Editorial Team

- Jan 31, 2012 Quiz Created by OldFashionedChar

Related Topics

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Robert Frost

- William Shakespeare

Featured Quizzes

Popular Topics

- Actor Quizzes

- Actress Quizzes

- Author Quizzes

- Business People Quizzes

- Historical Person Quizzes

- Musician Quizzes

- Painter Quizzes

- Poet Quizzes

- Politician Quizzes

- Scientist Quizzes

- Singer Quizzes

- Sports Person Quizzes

Related Quizzes

Wait! Here's an interesting quiz for you.

The best free cultural &

educational media on the web

- Online Courses

- Certificates

- Degrees & Mini-Degrees

- Audio Books

An Animated Introduction to Charles Dickens’ Life & Literary Works

in Animation , Literature | June 21st, 2016 Leave a Comment

The social role of the writer changes from generation to generation, but at no time in the history of literary culture have novelists and poets faced more competition for the attention of their readers than they do today. Before visual media took over as the primary means of storytelling, however, many writers enjoyed the measure of fame now given to film and pop music stars. Or at least they did in the age of Charles Dickens , whose tireless self-promotion and populist sentiments endeared him to the public and made him one of the most famous men of his day.

Dickens was “a great showman” says Alain de Botton above in his School of Life introduction to the author of Great Expectations , Oliver Twist , A Tale of Two Cities , and too many more great books to name. (Find them in our collections of Free eBooks and Free Audio Books .) He was a natural celebrity before radio and television and, to the dismay of his more high-minded colleagues, “entertainment was at the heart of what Dickens was up to.”

But Dickens used his public platform not only to advance his career, but also to “get us interested in some pretty serious things: the evils of an industrializing society, the working conditions in factories, child labor, vicious social snobbery, the maddening inefficiencies of government bureaucracy.” Then and now, these are hardly subjects readers want to be reminded of. And yet, then as now, great storytellers can make us care despite our apathy and desire for escapist pleasure. And few writers have made readers care more than Dickens.

His “genius was to discover that the big ambitions to educate a society about its failings didn’t have to be opposed to what his critics called ‘fun’—racy plots, a chatty style, clownish characters, weepy moments, and happy endings.” Yet Dickens didn’t only seek to educate, de Botton argues; he “believed that writing could play a big role in fixing the problems of the world.” In this he was not entirely wrong, despite the anti-political sentiments of so many aesthetes who have argued otherwise, from Oscar Wilde to W.H. Auden .

Though he opposed many working class movements and had no “coherent doctrine” of social change, says Hugh Cunningham , professor of social history at the University of Kent , Dickens “helped create a climate of opinion” by emotionally moving people to sympathize with the poor and to take action in controversies already raging in the zeitgeist. In this role, Dickens preceded dozens of writers who—like himself—began their careers in journalism and sought through fiction to motivate complacent readers: naturalist novelists like Emile Zola, Stephen Crane, and Theodore Dreiser, and muckraking realists like Upton Sinclair all owe something to Dickens’ mode of social protest through novel-writing.

De Botton goes on in his introduction to explain some of the biographical origins of Dickens’ sympathy for the afflicted, including his own time spent as a child laborer and his father’s confinement in debtor’s prison. The conditions Dickens and his characters endured are unimaginable to most privileged readers, but not to millions of people in poverty around the world who still live under the kind of squalid oppression the Victorian poor suffered. Whether any author in the 21st century can bring the same kind of sympathetic attention to their lives that Dickens did in his time is debatable, but De Botton uses Dickens’ example to argue that art and entertainment can “seduce” us into compassion and taking action for others.

Related Content:

Download 55 Free Online Literature Courses: From Dante and Milton to Kerouac and Tolkien

Celebrate the 200th Birthday of Charles Dickens with Free Movies, eBooks and Audio Books

An Animated Introduction to Jane Austen

Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Life & Literature Introduced in a Monty Python-Style Animation

What Are Literature, Philosophy & History For? Alain de Botton Explains with Monty Python-Style Videos

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

by Josh Jones | Permalink | Comments (0) |

Related posts:

Comments (0).

Be the first to comment.

Add a comment

Leave a reply.

Name (required)

Email (required)

XHTML: You can use these tags: <a href="" title=""> <abbr title=""> <acronym title=""> <b> <blockquote cite=""> <cite> <code> <del datetime=""> <em> <i> <q cite=""> <s> <strike> <strong>

Click here to cancel reply.

- 1,700 Free Online Courses

- 200 Online Certificate Programs

- 100+ Online Degree & Mini-Degree Programs

- 1,150 Free Movies

- 1,000 Free Audio Books

- 150+ Best Podcasts

- 800 Free eBooks

- 200 Free Textbooks

- 300 Free Language Lessons

- 150 Free Business Courses

- Free K-12 Education

- Get Our Daily Email

Free Courses

- Art & Art History

- Classics/Ancient World

- Computer Science

- Data Science

- Engineering

- Environment

- Political Science

- Writing & Journalism

- All 1500 Free Courses

- 1000+ MOOCs & Certificate Courses

Receive our Daily Email

Free updates, get our daily email.

Get the best cultural and educational resources on the web curated for you in a daily email. We never spam. Unsubscribe at any time.

FOLLOW ON SOCIAL MEDIA

Free Movies

- 1150 Free Movies Online

- Free Film Noir

- Silent Films

- Documentaries

- Martial Arts/Kung Fu

- Free Hitchcock Films

- Free Charlie Chaplin

- Free John Wayne Movies

- Free Tarkovsky Films

- Free Dziga Vertov

- Free Oscar Winners

- Free Language Lessons

- All Languages

Free eBooks

- 700 Free eBooks

- Free Philosophy eBooks

- The Harvard Classics

- Philip K. Dick Stories

- Neil Gaiman Stories

- David Foster Wallace Stories & Essays

- Hemingway Stories

- Great Gatsby & Other Fitzgerald Novels

- HP Lovecraft

- Edgar Allan Poe

- Free Alice Munro Stories

- Jennifer Egan Stories

- George Saunders Stories

- Hunter S. Thompson Essays

- Joan Didion Essays

- Gabriel Garcia Marquez Stories

- David Sedaris Stories

- Stephen King

- Golden Age Comics

- Free Books by UC Press

- Life Changing Books

Free Audio Books

- 700 Free Audio Books

- Free Audio Books: Fiction

- Free Audio Books: Poetry

- Free Audio Books: Non-Fiction

Free Textbooks

- Free Physics Textbooks

- Free Computer Science Textbooks

- Free Math Textbooks

K-12 Resources

- Free Video Lessons

- Web Resources by Subject

- Quality YouTube Channels

- Teacher Resources

- All Free Kids Resources

Free Art & Images

- All Art Images & Books

- The Rijksmuseum

- Smithsonian

- The Guggenheim

- The National Gallery

- The Whitney

- LA County Museum

- Stanford University

- British Library

- Google Art Project

- French Revolution

- Getty Images

- Guggenheim Art Books

- Met Art Books

- Getty Art Books

- New York Public Library Maps

- Museum of New Zealand

- Smarthistory

- Coloring Books

- All Bach Organ Works

- All of Bach

- 80,000 Classical Music Scores

- Free Classical Music

- Live Classical Music

- 9,000 Grateful Dead Concerts

- Alan Lomax Blues & Folk Archive

Writing Tips

- William Zinsser

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Toni Morrison

- Margaret Atwood

- David Ogilvy

- Billy Wilder

- All posts by date

Personal Finance

- Open Personal Finance

- Amazon Kindle

- Architecture

- Artificial Intelligence

- Beat & Tweets

- Comics/Cartoons

- Current Affairs

- English Language

- Entrepreneurship

- Food & Drink

- Graduation Speech

- How to Learn for Free

- Internet Archive

- Language Lessons

- Most Popular

- Neuroscience

- Photography

- Pretty Much Pop

- Productivity

- UC Berkeley

- Uncategorized

- Video - Arts & Culture

- Video - Politics/Society

- Video - Science

- Video Games

Great Lectures

- Michel Foucault

- Sun Ra at UC Berkeley

- Richard Feynman

- Joseph Campbell

- Jorge Luis Borges

- Leonard Bernstein

- Richard Dawkins

- Buckminster Fuller

- Walter Kaufmann on Existentialism

- Jacques Lacan

- Roland Barthes

- Nobel Lectures by Writers

- Bertrand Russell

- Oxford Philosophy Lectures

Receive our newsletter!

Open Culture scours the web for the best educational media. We find the free courses and audio books you need, the language lessons & educational videos you want, and plenty of enlightenment in between.

Great Recordings

- T.S. Eliot Reads Waste Land

- Sylvia Plath - Ariel

- Joyce Reads Ulysses

- Joyce - Finnegans Wake

- Patti Smith Reads Virginia Woolf

- Albert Einstein

- Charles Bukowski

- Bill Murray

- Fitzgerald Reads Shakespeare

- William Faulkner

- Flannery O'Connor

- Tolkien - The Hobbit

- Allen Ginsberg - Howl

- Dylan Thomas

- Anne Sexton

- John Cheever

- David Foster Wallace

Book Lists By

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Ernest Hemingway

- F. Scott Fitzgerald

- Allen Ginsberg

- Patti Smith

- Henry Miller

- Christopher Hitchens

- Joseph Brodsky

- Donald Barthelme

- David Bowie

- Samuel Beckett

- Art Garfunkel

- Marilyn Monroe

- Picks by Female Creatives

- Zadie Smith & Gary Shteyngart

- Lynda Barry

Favorite Movies

- Kurosawa's 100

- David Lynch

- Werner Herzog

- Woody Allen

- Wes Anderson

- Luis Buñuel

- Roger Ebert

- Susan Sontag

- Scorsese Foreign Films

- Philosophy Films

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- August 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

- August 2008

- February 2008

- January 2008

- December 2007

- November 2007

- October 2007

- September 2007

- August 2007

- February 2007

- January 2007

- December 2006

- November 2006

- October 2006

- September 2006

©2006-2024 Open Culture, LLC. All rights reserved.

- Advertise with Us

- Copyright Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Charles Dickens Wrote 'A Christmas Carol' in Only Six Weeks

Dickens was struggling financially

Dickens began to write what would become A Christmas Carol in October 1843. He was determined to get the book out in time for Christmas that year, giving him a very short window to work in. However, the pressing schedule wasn't solely motivated by authorial inspiration — Dickens also had a desperate need for money.

At the time, Dickens' writing career was in a slump. He'd had hits like The Old Curiosity Shop , but his current serialized novel, The Life and Adventures of Martin Chuzzlewit , wasn't selling well. His publishers wanted to decrease his pay from £200 to £150 per month, which would have been devastating. Dickens was in debt and had a family to support. Not only was he married with a fifth child on the way, his father was also in a financial drain.

Dickens figured a successful Christmas book could net him around £1,000. Yet though his goal wasn't to pen a timeless work of art, his dire financial situation prompted him to get the book done.

Dickens wanted to represent the less fortunate

While money was admittedly a factor in Dickens writing A Christmas Carol , but he also had a message to convey about Victorian society and how it treated its most desperate members. Early in 1843, Dickens had read a parliamentary report about children in the workforce, which contained testimony from young laborers about their long days, low wages, and dangerous working conditions.

Having worked in a factory himself as a boy due to his family's straitened circumstances, Dickens always felt a kinship with those who were struggling, particularly children. The parliamentary report made him want to write a pamphlet titled "An Appeal to the People of England on behalf of the Poor Man’s Child." Yet a few days later he changed his mind, noting in a letter on March 10, 1843, that he'd put off the pamphlet because he had other means in mind with "twenty thousand times the force" of this initial approach.

Later in 1843, Dickens visited schools for the poor in the slums (called "ragged schools" in reference to the worn clothes of many attendees), where he encountered children who lived as thieves and prostitutes to survive. In October, he traveled to Manchester to give a speech on the importance of education for every class. Soon after this talk, he had the idea for A Christmas Carol — a book that showed the challenges faced by the poor, and how more generosity could lessen their burdens.

READ MORE: The Secret Relationship That Charles Dickens Tried to Hide

Tiny Tim was inspired by Dickens' family members

Dickens began writing A Christmas Carol in October and finished the story, which came in at less than 30,000 words, six weeks later. Writing a full story in this manner was new for him, as his other novels had been serialized over months and years. The method may have helped him craft a stronger story.

To create Tiny Tim, the ailing young boy who's a primary catalyst for Ebenezer Scrooge changing his miserly ways, Dickens drew on the lives of two family members: a sickly younger brother who'd been known as Tiny Fred and a nephew, Henry Burnett Jr., who was disabled. Dickens had seen his nephew on his Manchester visit and had noted some of the difficulties the boy faced.

In addition to Tiny Tim, Dickens incorporated a glimpse of the devastation he witnessed in real life. Scrooge discovers a feral boy (Ignorance) and girl (Want) under the cloak of the visiting Ghost of Christmas Present. The two are described as "wretched, abject, frightful, hideous, miserable." When Scrooge asks if they can be helped, the spirit throws the miser's earlier words back at him, asking, "Are there no prisons? Are there no workhouses?"

The book was sold out by Christmas

Some books need to build a following, but A Christmas Carol was an immediate success. The debut print run of 6,000 copies, which arrived on December 19, sold out in a week. The timing was ripe for a Christmas book to take off, as Christmas trees were being popularized by Prince Albert and Queen Victoria , and Christmas cards soon arrived on the scene.

However, there was something special about A Christmas Carol beyond its connection to the zeitgeist. Dickens would write other books and articles at Christmastime in the following years, yet those works — among which are The Chimes and The Cricket on the Hearth — are mostly forgotten today.

Despite Carol 's success, Dickens didn't get his hoped-for financial windfall. Instead of £1,000, he received about £250, a big disappointment. The books were beautiful, with red cloth binding, gilt-edged pages and colored illustrations. But book sales weren't enough to cover the costs of production, which had included an array of last-minute changes insisted upon by Dickens.

Dickens did 127 readings of the novel

A Christmas Carol has been adapted countless times. Soon after the book was published, unauthorized stage versions appeared (sadly, given his financial troubles, Dickens usually didn't make any money from these). And the story's often been filmed, with versions ranging from the silent era to later ones with the Muppets, Bill Murray and Toni Braxton .

Many are familiar with A Christmas Carol as Dickens' most famous book because they've seen one of these adaptations of the tale. But Dickens also did his own adapting when he read the story in public. The first public reading of A Christmas Carol was held in 1853. That was for charity, but Dickens also gave paid readings; between 1853 and 1870 he offered 127 performances of A Christmas Carol .

After hearing a Carol reading by Dickens in Boston on Christmas Eve in 1867, a businessman decided to close his factory for Christmas. He also provided all of his workers with a turkey, just like Scrooge. This demonstrates how these readings helped spread the message — and renown — of A Christmas Carol . It's another reason why the name Charles Dickens is forever linked with Christmas and his famous novel, A Christmas Carol .

Famous Authors & Writers

A Huge Shakespeare Mystery, Solved

9 Surprising Facts About Truman Capote

William Shakespeare

How Did Shakespeare Die?

Meet Stand-Up Comedy Pioneer Charles Farrar Browne

Francis Scott Key

Christine de Pisan

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

10 Famous Langston Hughes Poems

5 Crowning Achievements of Maya Angelou

10 Black Authors Who Shaped Literary History

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

name dickens's series of employment prior to his successful writing career. shoe factory, clerk at a lawyer's office, stenographer, newspaper reporter. wife. catherine hogarth. number of children. 10. wife's first sister. mary Hogarth (died at 17) wife's youngest sister.

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like When was Great Expectations written?, Where was Charles Dickens born?, When was Charles Dickens born? and more.

Charles Dickens Biography Answer Key. 22 terms. rowana25. 2nd Edition • ISBN: 9780312676506 Lawrence Scanlon, Renee H. Shea, Robin Dissin Aufses. 1st Edition • ISBN: 9780312388065 Carol Jago, Lawrence Scanlon, Renee H. Shea, Robin Dissin Aufses. 3rd Edition • ISBN: 9780538450485 Darlene Smith-Worthington, Sue Jefferson.

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like When Charles was 12, where did he work?, Why did Charles get to work as soon as he could?, Why did Charles leave Washingon Academy? and more.

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like where was Dickens born?, when was dickens born?, who were his parents? and more.

How many successful tours did Dickens make in England, Scotland, and Ireland? 4 successful tours, 1.)1858-59 2.)1861-63 3.)1866-67 4.)1869-70. When did Dickens and his wife separate? What happened?

Start studying Charles Dickens Biography. Learn vocabulary, terms, and more with flashcards, games, and other study tools.

Charles John Huffam Dickens (/ ˈ d ɪ k ɪ n z /; 7 February 1812 - 9 June 1870) was an English novelist and social critic who created some of the world's best-known fictional characters, and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian era. His works enjoyed unprecedented popularity during his lifetime and, by the 20th century, critics and scholars had recognised him as a ...

Charles Dickens (born February 7, 1812, Portsmouth, Hampshire, England—died June 9, 1870, Gad's Hill, near Chatham, Kent) was an English novelist, generally considered the greatest of the Victorian era. His many volumes include such works as A Christmas Carol, David Copperfield, Bleak House, A Tale of Two Cities, Great Expectations, and Our ...

Charles Dickens Biography. Charles Dickens was born on February 7, 1812, in Portsea, England. His parents were middle-class, but they suffered financially as a result of living beyond their means. When Dickens was twelve years old, his family's dire straits forced him to quit school and work in a blacking factory (where shoe polish was ...

Charles Dickens was a British author, journalist, editor, illustrator, and social commentator who wrote the beloved classics Oliver Twist, A Christmas Carol, and Great Expectations. His books were ...

Catherine Dickens. (1815-1879) - Charles Dickens' wife, with whom he fathered 10 children. She was born in Scotland on May 19, 1815 and came to England with her family in 1834. Catherine was the daughter of George Hogarth, editor of the Evening Chronicle where Dickens was a young journalist.

Charles Dickens Biography. The title of Charles Dickens' novel Hard Times is an apt description of his early life and youth. Born February 7, 1812, the boy was one of eight children. His formal education was scanty, but as a child Charles spent much of his time reading and listening to the stories told by his grandmother.

In A Christmas Carol, he lashes out against the greed and corruption of the Victorian rich, symbolized by Scrooge prior to his redemption, and celebrates the selflessness and virtue of the poor, represented by the Cratchit family. He even examines the seamier underbelly of London, showing us a scene in the bowels of London as workers divvy up ...

A Tale of Two Cities study guide contains a biography of Charles Dickens, literature essays, a complete e-text, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis. About A Tale of Two Cities; A Tale of Two Cities Summary; A Tale of Two Cities Video; Character List; Glossary; Read the Study Guide for A Tale of Two Cities…

Charles Dickens was born in Portsmouth, England, in 1812, and spent his early years at Chatham, in Kent. In 1823, the family moved to London, where his father, in straightened circumstances, was eventually committed to Marshalsea Prison for debt. While his parents and siblings lived in the debtor's prison, Charles was sent to work at Warren ...

Charles Dickens Biography. Dickens, Charles John Huffam (1812-1870), probably the best-known and, to many people, the greatest English novelist of the 19th century. A moralist, satirist, and social reformer, Dickens crafted complex plots and striking characters that capture the panorama of English society.

Charles Dickens Biography & Background on Oliver Twist Historical Context: The English Poor Laws Suggestions for Further Reading ... Throughout the novel, Dickens uses Oliver's character to challenge the Victorian idea that paupers and criminals are already evil at birth, arguing instead that a corrupt environment is the source of vice. At ...

Correct Answer. B. Amy Dorrit. Explanation. Amy Dorrit is the correct answer because she was born and raised in debtors' prison. In Charles Dickens' novel "Little Dorrit," Amy Dorrit's father was imprisoned for debt, and she was born and spent her early years in the Marshalsea debtors' prison.

Dickens was "a great showman" says Alain de Botton above in his School of Life introduction to the author of Great Expectations, Oliver Twist, A Tale of Two Cities, and too many more great books to name. (Find them in our collections of Free eBooks and Free Audio Books .) He was a natural celebrity before radio and ...

Dickens began writing A Christmas Carol in October and finished the story, which came in at less than 30,000 words, six weeks later. Writing a full story in this manner was new for him, as his ...

Becoming Dickens tells the story of how an ambitious young Londoner became England's greatest novelist. In following the twists and turns of Charles Dickens's early career, Robert Douglas-Fairhurst examines a remarkable double transformation: in reinventing himself Dickens reinvented the form of the novel. It was a high-stakes gamble, and Dickens never forgot how differently things could ...

Quiz. Great Expectations at a Glance. Book Summary. About Great Expectations. Character List. Summary and Analysis. Chapters 1-3. Chapters 4-6. Chapters 7-9.