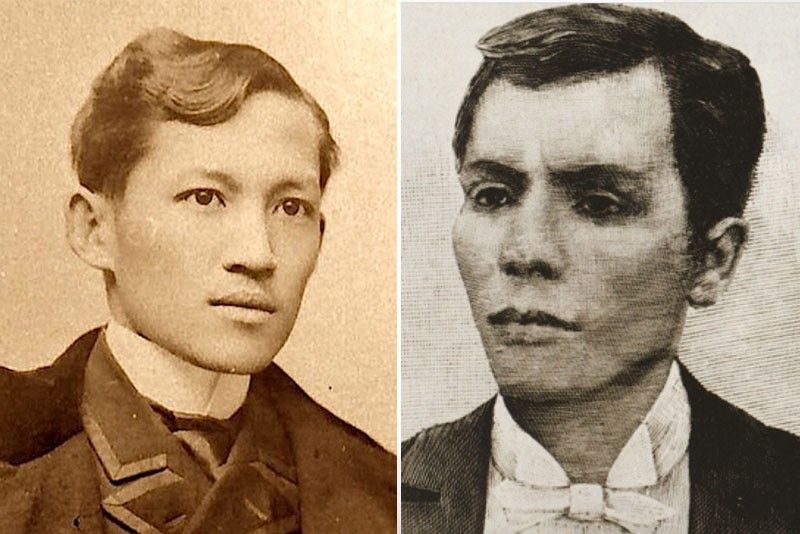

The Death of Jose Rizal

The death of Jose Rizal on December 30, 1896 came right after a kangaroo trial convicted him on all three charges of rebellion, sedition and conspiracy.

December 30th is the death anniversary of Dr. Jose Rizal. The death of Jose Rizal came right after a kangaroo trial convicted him on all three charges of rebellion, sedition and conspiracy. He was guided to his cell in Fort Santiago where he spent his last 24 hours right after the conviction. At 6:00 AM of December 29, 1896, Captain Rafael Dominguez read Jose Rizal’s death sentence and declared that he will be shot at 7:00 AM of the next day in Bagumbayan .

At 8:00 PM of the same day, Jose Rizal had his last supper and informed Captain Dominguez that he had forgiven his enemies including the military judges that condemned him to die. Rizal heard mass at 3:00 in the morning of December 30, 1896, had confession before taking the Holy Communion. He took his last breakfast at 5:30 AM of December 30, 1896 and even had the time to write two letters one for his family while the other letter was for his brother Paciano. This was also the time when his wife, Josephine Bracken and his sister Josefa arrived and bade farewell to Rizal.

Rizal who was dressed in a black suit was a few meters behind his advance guards while moving to his slaughter place and was accompanied by Lt. Luis Taviel de Andrade, two Jesuit priests and more soldiers behind him. The atmosphere was just like any execution by musketry by which the sound of the drums occupied the air. Rizal looked at the sky while walking and mentioned how beautiful that day was.

Rizal was told to stand on a grassy lawn between two lam posts in the Bagumbayan field, looking towards the Manila Bay. He requested the firing squad commander to shoot him facing the firing squad but was ordered to turn his back against the squad of Filipino soldiers of the Spanish army. A backup force of regular Spanish Army troops were on standby to shoot the executioners should they fail to obey the orders of the commander.

Jose Rizal’s execution was carried out when the command “Fuego” was heard and Rizal made an effort to face the firing squad but his bullet riddled body turned to the right and his face directed to the morning sun. Rizal exactly died at 7:03 AM and his last words before he died were those said by Jesus Christ: “consummatum est,” which means, “It is finished.”

Jose Rizal was secretly buried in Paco Cemetery in Manila but no identification was placed in his grave. His sister Narcisa tried to look in every grave site and found freshly turned soil at the Paco cemetery, assuming the burial site as the area where Rizal was buried. She gave a gift to the site caretaker so as to mark the grave with RPJ — the initials of Rizal in reverse.

Related Articles

Related posts.

Join the Discussion Cancel reply

(1861-1896)

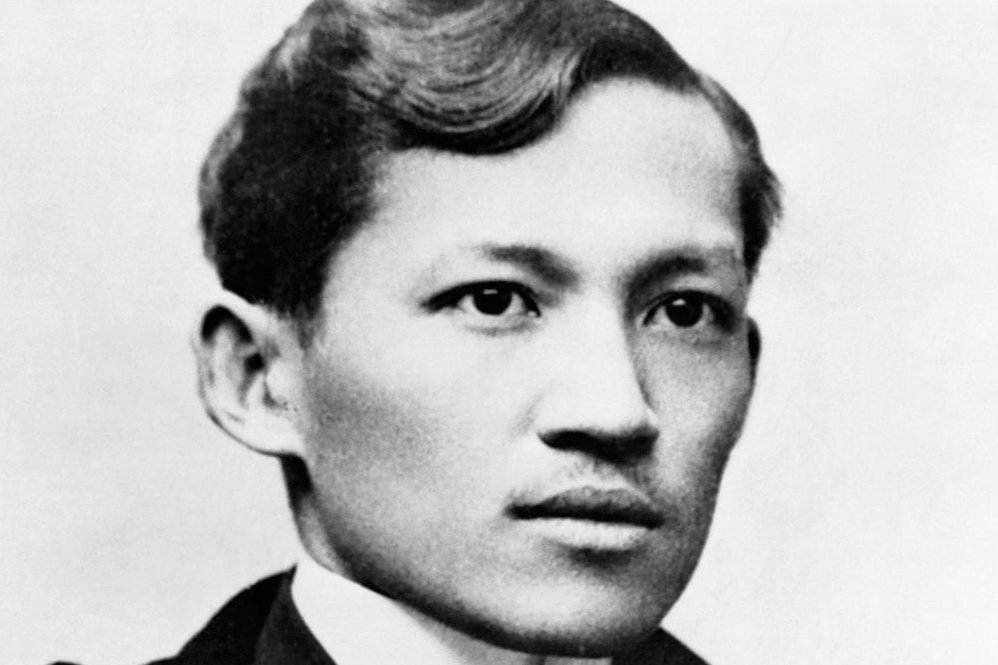

Who Was José Rizal?

While living in Europe, José Rizal wrote about the discrimination that accompanied Spain's colonial rule of his country. He returned to the Philippines in 1892 but was exiled due to his desire for reform. Although he supported peaceful change, Rizal was convicted of sedition and executed on December 30, 1896, at age 35.

On June 19, 1861, José Protasio Rizal Mercado y Alonso Realonda was born in Calamba in the Philippines' Laguna Province. A brilliant student who became proficient in multiple languages, José Rizal studied medicine in Manila. In 1882, he traveled to Spain to complete his medical degree.

Writing and Reform

While in Europe, José Rizal became part of the Propaganda Movement, connecting with other Filipinos who wanted reform. He also wrote his first novel, Noli Me Tangere ( Touch Me Not/The Social Cancer ), a work that detailed the dark aspects of Spain's colonial rule in the Philippines, with particular focus on the role of Catholic friars. The book was banned in the Philippines, though copies were smuggled in. Because of this novel, Rizal's return to the Philippines in 1887 was cut short when he was targeted by police.

Rizal returned to Europe and continued to write, releasing his follow-up novel, El Filibusterismo ( The Reign of Greed ) in 1891. He also published articles in La Solidaridad , a paper aligned with the Propaganda Movement. The reforms Rizal advocated for did not include independence—he called for equal treatment of Filipinos, limiting the power of Spanish friars and representation for the Philippines in the Spanish Cortes (Spain's parliament).

Exile in the Philippines

Rizal returned to the Philippines in 1892, feeling he needed to be in the country to effect change. Although the reform society he founded, the Liga Filipino (Philippine League), supported non-violent action, Rizal was still exiled to Dapitan, on the island of Mindanao. During the four years Rizal was in exile, he practiced medicine and took on students.

Execution and Legacy

In 1895, Rizal asked for permission to travel to Cuba as an army doctor. His request was approved, but in August 1896, Katipunan, a nationalist Filipino society founded by Andres Bonifacio, revolted. Though he had no ties to the group and disapproved of its violent methods, Rizal was arrested shortly thereafter.

After a show trial, Rizal was convicted of sedition and sentenced to death by firing squad. Rizal's public execution was carried out in Manila on December 30, 1896, when he was 35 years old. His execution created more opposition to Spanish rule.

Spain's control of the Philippines ended in 1898, though the country did not gain lasting independence until after World War II. Rizal remains a nationalist icon in the Philippines for helping the country take its first steps toward independence.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Jose Rizal

- Birth Year: 1861

- Birth date: June 19, 1861

- Birth City: Calamba, Laguna Province

- Birth Country: Philippines

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: José Rizal called for peaceful reform of Spain's colonial rule in the Philippines. After his 1896 execution, he became an icon for the nationalist movement.

- Science and Medicine

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- World Politics

- Astrological Sign: Gemini

- University of Madrid

- University of Heidelberg

- University of Santo Tomas

- Nacionalities

- Death Year: 1896

- Death date: December 30, 1896

- Death City: Manila

- Death Country: Philippines

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: José Rizal Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/political-figures/josé-rizal

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: May 3, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- [C]reative genius does not manifest itself solely within the borders of a specific country: it sprouts everywhere; it is like light and air; it belongs to everyone: it is cosmopolitan like space, life and God.

- What is the use of independence if the slaves of today will be the tyrants of tomorrow?

- Tomorrow at seven, I shall be shot; but I am innocent of the crime of rebellion. I am going to die with a tranquil conscience.

Famous Political Figures

Madeleine Albright

These Are the Major 2024 Presidential Candidates

Hillary Clinton

Indira Gandhi

Toussaint L'Ouverture

Vladimir Putin

Kevin McCarthy

Henry Kissinger

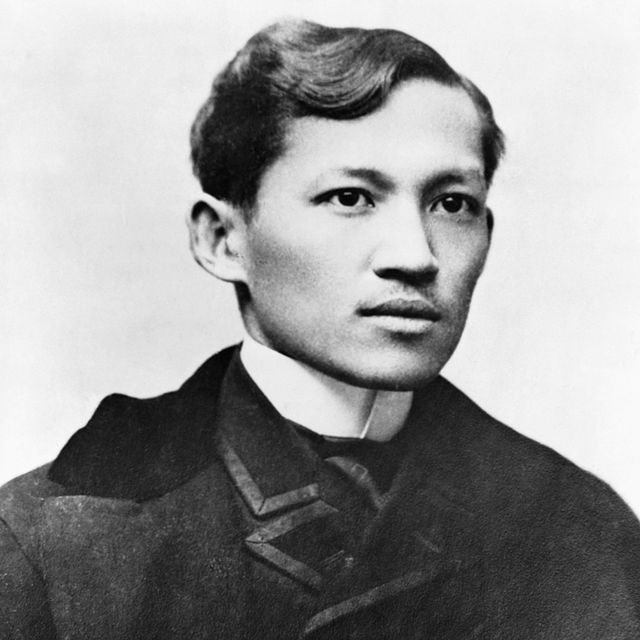

Oppenheimer and Truman Met Once. It Went Badly.

A.P.J. Abdul Kalam

On The Hill

The colourful life and death of josé rizal.

- September 29, 2019

By Maggie Chambers.

José Rizal, former resident of 37 Chalcot Crescent , was a doctor, writer and national hero of the Philippines. An English Heritage blue plaque was erected to him in 1983, and there has long been a statue of him in Primrose Hill Library ’s garden.

He was also suspected of being the father of Hitler.

Because Rizal did a lot in his short life, and led such a colourful existence, there are spurious and overblown rumours which have stuck to him. The Germans, for instance, believed he was a French spy as he travelled widely and could speak 22 languages; and some thought he was gay as he never married, dressed immaculately and was devoted to his mum. The Hitler rumour began after Rizal stayed in the Metropole Hotel, Vienna for a few days. He had a brief affair here, which coincided roughly with the date Hitler would have been conceived, give or take a couple of years. Another fabulous myth is that José Rizal was the man behind the Jack the Ripper murders. The murders coincided with Rizal’s time in Primrose Hill (1888/89) and ended just as he left London for Paris. Rizal was a qualified doctor, and the murderer had obvious medical knowledge, and was in possession of a scalpel.

So who exactly was this José Rizal?

Rizal was born in Calamba in the Philippines, the seventh child in a family of eleven children. After studying land surveying in the Philippines, he became aware that his mother’s eyesight was failing, so decided to specialise in ophthalmology. In 1882 he travelled to Madrid, without his parents’ knowledge or consent, to study medicine at the University of Madrid.

There was a small allowance available for study, but if the family farm in the Philippines had bad harvests, Rizal had to be thrifty, at times going for days without food. In order to take his exams in Madrid, he secretly pawned his sister Saturnina’s ring.

As well as his academic achievements, Rizal was a polymath and mastered a great number of skills in both sciences and the arts. He was a talented sculptor, artist, writer and musician. He carved a statue of the sacred heart whilst a teenager and made works from clay, terracotta, wax and plaster. He was a cartoonist, cartographer, and farmer and excelled in pistol shooting and fencing. The exception was singing, in which he said he ‘sounded like the braying of an ass’.

Rizal wrote two novels: Noli Me Tángere (Touch Me Not), which detailed the darker aspects of Spanish colonialism in the Philippines with particular regard to the role of the Catholic Church and its friars, and his follow-up novel El Filibusterismo (The Reign of Greed) 1891.

He also wrote collections of poetry, plays and essays including an article called ‘The Treatment and Cure of the Bewitched’ which explored treatment methods and explained that witches did not always have to be women, nor were they necessarily old or ugly. Other than the Austrian affair which sparked the Hitler rumour, Rizal was known for his many love affairs. When he was only fourteen he met and became attached to Leonor Rivera. After he left to study in Europe, they wrote to each other in coded letters as her mother didn’t approve of the relationship, fearing Rizal’s reputation as a subversive. On his return, Rizal’s father forbade him to visit Rivera as he didn’t want her family to be put in danger with the authorities. Rivera eventually married an English railway engineer (found for her by her mother), and Rizal was left devastated.

In 1888, Rizal took lodgings at 37 Chalcot Crescent as it was close enough to the British Museum where he wished to study. His landlord was Mr Beckett, the organist of St Paul’s Church in Avenue Road (St Paul’s School on Elsworthy Road evolved from this church).

Beckett had a daughter, Gertrude, whom Rizal admired. But the feelings were not reciprocated, and when he finished his studies, Rizal left her with a clay medallion portrait of herself. He set off for Paris, into the arms of Nelly Boustead, the daughter of a rich British trader, over whom he almost fell into a duel to the death. His final love was an Irish woman living in Hong Kong called Josephine Bracken. Her blind father was a patient of Rizal in his ophthalmology clinic. They fell in love, and would have married but for Rizal refusing to return to the Catholicism, which he had rejected. They had a son who died a few hours after his birth. After Rizal’s death, Bracken set off for the muddy and overgrown expanses of the Philippine revolution’s enemy lines, where she reloaded spent cartridges for the rebels. She died six years later of TB.

Politically, Rizal was a member of the Filipino Propaganda Movement which advocated equal rights and education for Filipinos, representation in the Spanish parliament, and limits on the powers of the friars. His desire was to achieve self-government peacefully, rather than by means of violent revolution.

In 1892 Rizal returned to the Philippines, because in order to effect change he needed to be present in the country. Although not involved in the planning or action of the revolution, he was sympathetic to its causes, and his writings helped to inflame the movement. Although supporting non-violence, Rizal’s novels were enough to get him declared an enemy of the state and he was exiled for four years to Dapitan on the island of Mindanao. There he built a hospital and a school, installed a water supply and taught farming methods. There are three animals named after him that he collected during his time in Dapitan: Apogonia Rizali, a small beetle; Draco Rizali, a species of flying dragon; and Rachophorous Rizali, a toad.

After his release, he was given permission to travel to Cuba to treat yellow fever. He and Josephine left on the ship bound for Cuba, but he was arrested en route. A nationalist Filipino society, the Katipunan, had started a rebellion, and Rizal was suspected, incorrectly, of being allied to them. After a show trial, Rizal was convicted of rebellion, conspiracy and sedition and sentenced to death. He was executed by firing squad in Manilla on 30 December 1896 at the age of 35.

On the evening before he was to be executed, Rizal placed documents in his pockets and shoes, presuming his body would be handed to his family after the execution. His final poem, Mi último adios, was hidden in an oil lamp which was passed to his family along with his remaining few possessions and his burial requests. The firing squad consisted of eight Filipinos armed with Remington rifles. Stationed behind them were eight Spanish soldiers armed with Mausers, with orders to shoot any executioner who failed to carry out his duty.

Only one live bullet was put into the rifles; the rest contained blanks.

Only one live bullet was put into the rifles; the rest contained blanks. They knew of his innocence, and meant to assuage any guilt. His execution photo includes the dog which was the firing squad’s mascot. After he was shot, the dog is said to have run whining around the corpse as a soldier fired a final shot into Rizal’s head to ensure he was dead.

The Spanish authorities buried him in an unmarked grave and the papers Rizal had hidden about his person disintegrated. His sister Narcisi found a guarded graveyard with a freshly dug grave which she knew must be his, and marked the grave RPJ, her brother’s initials in reverse.

A section of vertebrae which was damaged by a bullet was retained by Rizal’s family and is now on display in the Rizal Shrine in Fort Santiago, Manilla.

His last words echoed those of Christ: “Consummatum est”. “It is finished.” Rizal was less a revolutionary than a writer who challenged the colonial status quo. Although his death was ultimately attributed to his writing, his dissenting works did have the effect of destroying Spain’s hold over the Philippines. Two years after his death Spain lost control of the Philippines, but it wasn’t until 1946 that independence was granted.

“One only dies once, and if one does not die well, a good opportunity is lost and will not present itself again. ” José Rizal

“ He who does not know how to look back at where he came from will never get to his destination .” José Rizal

You May Also Like

The Volunteer Phone Box Painter

Fun Things to Do in London

Cinema Sounds and Secrets with Brian Cox

The Life and Legacy of José Rizal: National Hero of the Philippines

Dr. José Rizal, the national hero of the Philippines, is not only admired for possessing intellectual brilliance but also for taking a stand and resisting the Spanish colonial government. While his death sparked a revolution to overthrow the tyranny, Rizal will always be remembered for his compassion towards the Filipino people and the country.

Did you know you can now travel with Culture Trip? Book now and join one of our premium small-group tours to discover the world like never before.

Humble beginnings

José Protasio Rizal Mercado Y Alonso Realonda was born on June 19, 1861 to Francisco Mercado and Teodora Alonzo in the town of Calamba in the province of Laguna. He had nine sisters and one brother. At the early age of three, the future political leader had already learned the English alphabet. And, by the age of five, José could already read and write.

Upon enrolling at the Ateneo Municipal de Manila (now referred to as Ateneo De Manila University ), he dropped the last three names in his full name, after his brother’s advice – hence, being known as José Protasio Rizal. His performance in school was outstanding – winning various poetry contests, impressing his professors with his familiarity of Castilian and other foreign languages, and crafting literary essays that were critical of the Spanish historical accounts of pre-colonial Philippine societies.

A man with multiple professions

While he originally obtained a land surveyor and assessor’s degree in Ateneo, Rizal also took up a preparatory course on law at the University of Santo Tomas (UST). But when he learned that his mother was going blind, he decided to switch to medicine school in UST and later on specialized in ophthalmology. In May 1882, he decided to travel to Madrid in Spain , and earned his Licentiate in Medicine at the Universidad Central de Madrid.

Apart from being known as an expert in the field of medicine, a poet, and an essayist, Rizal exhibited other amazing talents. He knew how to paint, sketch, and make sculptures. Because he lived in Europe for about 10 years, he also became a polyglot – conversant in 22 languages. Aside from poetry and creative writing, Rizal had varying degrees of expertise in architecture, sociology, anthropology, fencing, martial arts, and economics to name a few.

His novels awakened Philippine nationalism

Rizal had been very vocal against the Spanish government, but in a peaceful and progressive manner. For him, “the pen was mightier than the sword.” And through his writings, he exposed the corruption and wrongdoings of government officials as well as the Spanish friars.

While in Barcelona, Rizal contributed essays, poems, allegories, and editorials to the Spanish newspaper, La Solidaridad. Most of his writings, both in his essays and editorials, centered on individual rights and freedom, specifically for the Filipino people . As part of his reforms, he even called for the inclusion of the Philippines to become a province of Spain.

But, among his best works , two novels stood out from the rest – Noli Me Tángere (Touch Me Not) and El Filibusterismo ( The Reign of the Greed).

In both novels, Rizal harshly criticized the Spanish colonial rule in the country and exposed the ills of Philippine society at the time. And because he wrote about the injustices and brutalities of the Spaniards in the country, the authorities banned Filipinos from reading the controversial books. Yet they were not able to ban it completely. As more Filipinos read the books, their eyes opened to the truth that they were suffering unspeakable abuses at the hands of the friars. These two novels by Rizal, now considered his literary masterpieces, are said to have indirectly sparked the Philippine Revolution.

Rizal’s unfateful days

Upon his return to the Philippines, Rizal formed a progressive organization called the La Liga Filipina. This civic movement advocated social reforms through legal means. Now Rizal was considered even more of a threat by the Spanish authorities (alongside his novels and essays), which ultimately led to his exile in Dapitan in northern Mindanao .

This however did not stop him from continuing his plans for reform. While in Dapitan, Rizal built a school, hospital, and water system. He also taught farming and worked on agricultural projects such as using abaca to make ropes.

In 1896, Rizal was granted leave by then Governor-General Blanco, after volunteering to travel to Cuba to serve as doctor to yellow fever victims. But at that time, the Katipunan had a full-blown revolution and Rizal was accused of being associated with the secret militant society. On his way to Cuba, he was arrested in Barcelona and sent back to Manila to stand for trial before the court martial. Rizal was charged with sedition, conspiracy, and rebellion – and therefore, sentenced to death by firing squad.

Days before his execution, Rizal bid farewell to his motherland and countrymen through one of his final letters, entitled Mi último adiós or My Last Farewell. Dr. José Rizal was executed on the morning of December 30, 1896, in what was then called Bagumbayan (now referred to as Luneta). Upon hearing the command to shoot him, he faced the squad and uttered in his final breath: “ Consummatum est” (It is finished). According to historical accounts , only one bullet ended the life of the Filipino martyr and hero.

His legacy lives on

After his death, the Philippine Revolution continued until 1898. And with the assistance of the United States , the Philippines declared its independence from Spain on June 12, 1898. This was the time that the Philippine flag was waved at General Emilio Aguinaldo’s residence in Kawit, Cavite.

Today, Dr. Rizal’s brilliance, compassion, courage, and patriotism are greatly remembered and recognized by the Filipino people. His two novels are continuously being analyzed by students and professionals.

Colleges and universities in the Philippines even require their students to take a subject which centers around the life and works of Rizal. Every year, the Filipinos celebrate Rizal Day – December 30 each year – to commemorate his life and works. Filipinos look back at how his founding of La Liga Filipina and his two novels had an effect on the early beginnings of the Philippine Revolution. The people also recognize his advocacy to achieve liberty through peaceful means rather than violent revolution.

In honor of Rizal, memorials and statues of the national hero can be found not only within the Philippines, but in selected cities around the world. A road in the Chanakyapuri area of New Delhi (India) and in Medan, Indonesia is named after him. The José Rizal Bridge and Rizal Park in the city of Seattle are also dedicated to the late hero.

Within the Philippines, there are streets, towns/cities, a university (Rizal University), and a province named after him. Three species have also been named after Rizal – the Draco rizali (a small lizard, known as a flying dragon), Apogania rizali (a very rare kind of beetle with five horns) and the Rhacophorus rizali (a peculiar frog species).

To commemorate what he did for the country, the Philippines built a memorial park for him – now referred to as Rizal Park, found in Manila . There lies a monument which contains a standing bronze sculpture of Rizal, an obelisk, and a stone base said to contain his remains. The monument stands near the place where he fell during his execution in Luneta.

KEEN TO EXPLORE THE WORLD?

Connect with like-minded people on our premium trips curated by local insiders and with care for the world

Since you are here, we would like to share our vision for the future of travel - and the direction Culture Trip is moving in.

Culture Trip launched in 2011 with a simple yet passionate mission: to inspire people to go beyond their boundaries and experience what makes a place, its people and its culture special and meaningful — and this is still in our DNA today. We are proud that, for more than a decade, millions like you have trusted our award-winning recommendations by people who deeply understand what makes certain places and communities so special.

Increasingly we believe the world needs more meaningful, real-life connections between curious travellers keen to explore the world in a more responsible way. That is why we have intensively curated a collection of premium small-group trips as an invitation to meet and connect with new, like-minded people for once-in-a-lifetime experiences in three categories: Culture Trips, Rail Trips and Private Trips. Our Trips are suitable for both solo travelers, couples and friends who want to explore the world together.

Culture Trips are deeply immersive 5 to 16 days itineraries, that combine authentic local experiences, exciting activities and 4-5* accommodation to look forward to at the end of each day. Our Rail Trips are our most planet-friendly itineraries that invite you to take the scenic route, relax whilst getting under the skin of a destination. Our Private Trips are fully tailored itineraries, curated by our Travel Experts specifically for you, your friends or your family.

We know that many of you worry about the environmental impact of travel and are looking for ways of expanding horizons in ways that do minimal harm - and may even bring benefits. We are committed to go as far as possible in curating our trips with care for the planet. That is why all of our trips are flightless in destination, fully carbon offset - and we have ambitious plans to be net zero in the very near future.

Places to Stay

The most budget-friendly hotels in tagaytay.

The Best Pet-Friendly Hotels in Tagaytay, the Philippines

Where to Stay in Tagaytay, the Philippines, for a Local Experience

Hip Holiday Apartments in the Philippines You'll Want to Call Home

The Best Hotels to Book in the Philippines for Every Traveller

The Best Hotels to Book In Tagaytay for Every Traveller

See & Do

Exhilarating ways to experience the great outdoors in the philippines.

What Are the Best Resorts to Book in the Philippines?

The Best Resorts in Palawan, the Philippines

Bed & Breakfasts in the Philippines

The Best Hotels to Book in Pasay, the Philippines

The Best Hotels to Book in Palawan, the Philippines

Winter sale offers on our trips, incredible savings.

- Post ID: 1000117287

- Sponsored? No

- View Payload

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

The Lost Boy Lloyd

Life is one long vacation

Journeying through Jose Rizal’s Life, Exile, and Death

Posted on June 14, 2011

You see, the Rizals were not really landowners. They were tenants of the Dominicans who owned most of the land in Calamba. According to the Rizals (the Dominicans have their own version of the story), the tenants started to complain about rent increases that did not consider whether the harvest for that season was good or not…

Rizal was not a radical man, but in 1891, he became a spokesman for these tenants whom he advised to trust in the justice and goodness of Mother Spain. The tenants did just that, and the Spanish governor-general, Valeriano Weyler (who became notorious as the Butcher of Cuba), sent soldiers to bodily evict the hardheaded tenants from Calamba…It was a major upheaval for the people of Calamba and also Rizal, who became a marked man not only for his anti-clerical novel, Noli me tangere, but also for being in the center of a major agrarian dispute. –Rizal’s New Calamba in Sabah

Sometimes I cannot make sense of Rizal. Was he happy in Dapitan? In 1893, he wrote Blumentritt and described a typical day:

“I have three houses: a square house, a six-sided house, and an eight-sided house. My mother, my sister Trinidad, and a nephew and I live in the square house; my students—boys who I am teaching math, Spanish and English—and a patient [in the six-sided house]. My chickens live in the six-sided house. From my house, I can hear the murmur of a crystalline rivulet that drops from high rocks. I can see the shore, the sea where I have two small boats or barotos, as they are called here. I have many fruit trees: mangoes, lanzones, guyabanos, batuno, langka, etc. I have rabbits, dogs, cats, etc.

I get up early, at 5 in the morning inspect my fields, feed the chickens, wake up my farm-hands and get them to work. At half past 7, we have breakfast consisting of tea, pastries, cheese, sweets, etc. Then, I hold clinic examining patients and training the poor patients who come to see me. I dress and go to town in my baroto to visit my patients there. I return at noon and have lunch that has been prepared for me. Afterwards I teach the boys until 4 and spend the rest of the afternoon in the fields. At night, I read and study.”

Although Rizal did not live behind bars, Dapitan was not London, Paris, New York or Madrid. Dapitan was literally the boondocks. —Rizal’s poetry in Dapitan

The slow walk to Bagumbayan began at 6:30 a.m. It was a cool, clear morning and Rizal was dressed, appropriately, in black. Black coat, black pants and a black cravat emphasized by his white shirt and waistcoat. He was tied elbow to elbow, but he proudly held up his head, crowned with the signature chistera or bowler hat made famous by Charlie Chaplin…

He made one last request that the soldiers spare his precious head and shoot him in the back toward the heart. When the captain agreed, Rizal shook the hand of Taviel de Andrade and thanked him for the vain effort of defending him.

Meanwhile, a curious Spanish military doctor came and felt Rizal’s pulse and was surprised to find it regular and normal. The Jesuits were the last to leave the condemned man. They raised a crucifix to Rizal’s face and lips, but he turned his head away and silently prepared for death.

As the captain raised his saber in the air, he ordered his men to be ready and shouted, Preparen! The order to aim the rifles followed: Apunten!

Then, in split second before the captain’s saber was brought down with the order to fire Fuego!, Rizal shouted the two last words of Christ, Conssumatum est! (it is done). The shots rang out, the bullets hit their mark and Rizal made that carefully choreographed twist he practiced years before that would make him fall face-up on the ground. –“Oh, what a beautiful morning!”

- Lakbay Jose Rizal@150: Retracing Our National Hero’s Trail

- My First Manila Kid Article: On Traveling and Being Young

- Las Palmas de San Jose: Tuguegarao’s Hideaway

- The New Mabuhay Miles: Life Gets More Rewarding

- Kuala Lumpur

- Philippines

- Netherlands

- Airline News

- Airline Reviews

Select Chapter:

The philippines:a century hence.

Rizal’s “Filipinas Dentro De Cien Años”

Rizal’s “Filipinas Dentro De Cien Años” (translated as “The Philippines within One Hundred Years” or “The Philippines A Century Hence”) is an essay meant to forecast the future of the country within a hundred years. This essay, published in La Solidaridad of Madrid, reflected Rizal’s sentiments about the glorious past of the Philippines, the deterioration of the Philippine economy, and exposed the foundations of the native Filipinos’ sufferings under the cruel Spanish rule. More importantly, Rizal, in the essay, warned Spain as regards the catastrophic end of its domination – a reminder that it was time that Spain realizes that the circumstances that contributed to the French Revolution could have a powerful effect for her on the Philippine islands. Part of the purpose in writing the essay was to promote a sense of nationalism among the Filipinos – to awaken their minds and hearts so they would fight for their rights.

La Solidaridad, the newspaper which serialized Rizal’s Filipinas Dentro De Cien Años

Causes of miseries, 1. spain’s implementation of her military laws.

Because of such policies, the Philippine population decreased significantly. Poverty became more widespread, and f armlands were left to wither. The family as a unit of society was neglected, and overall, every aspect of the life of the Filipino was retarded.

2. Deterioration and disappearance of Filipino indigenous culture

When Spain came with the sword and the cross, it began the gradual destruction of the native Philippine culture. Because of this, the Filipinos started losing confidence in their past and their heritage, became doubtful of their present lifestyle, and eventually lost hope in the future and the preservation of their race. The natives began forgetting who they were – their valued beliefs, religion, songs, poetry, and other forms of customs and traditions.

3. Passivity and submissiveness to the Spanish colonizers

One of the most powerful forces that influenced a culture of silence among the natives were the Spanish friars. Because of the use of force and intimidation, unfairly using God’s name, the Filipinos learned to submit themselves to the will of the foreigners.

Rizal's Forecast

What will become of the Philippines within a century? Will they continue to be a Spanish Colony? Spain was able to colonize the Philippines for 300 years because the Filipinos remained faithful during this time, giving up their liberty and independence, sometimes stunned by the attractive promises or by the friendship offered by the noble and generous people of Spain. Initially, the Filipinos see them as protectors but sooner, they realize that they are exploiters and executers. So if this state of affair continues, what will become of the Philippines within a century? One, the people will start to awaken and if the government of Spain does not change its acts, a revolution will occur. But what exactly is it that the Filipino people like? 1) A Filipino representative in the Spanish Cortes and freedom of expression to cry out against all the abuses; and 2) To practice their human rights. If these happen, the Philippines will remain a colony of Spain, but with more laws and greater liberty. Similarly, the Filipinos will declare themselves ’independent’. Note that Rizal only wanted liberty from Spaniards and not total separation. In his essay, Rizal urges to put freedom in our land through peaceful negotiations with the Spanish Government in Spain. Rizal was confident as he envisioned the awakening of the hearts and opening of the minds of the Filipino people regarding their plight. He ‘prophesied’ that the Philippines will be successful in its revolution against Spain, winning their independence sooner or later. Though lacking in weapons and combat skills, the natives waged war against the colonizers and in 1898, the Americans wrestled with Spain to win the Philippines. Years after Rizal’s death, the Philippines attained its long-awaited freedom — a completion of what he had written in the essay, does not record in its archives any lasting domination by one people over another of different races, of diverse usages and customs, of opposite and divergent ideas. One of the two had to yield and succumb.” Indeed, the essay, The Philippines a Century Hence is as relevant today as it was when it was written over a century ago. Alongside Noli Me Tangere and El Filibusterismo, Rizal shares why we must focus on strengthening the most important backbone of the country – our values, mindsets, and all the beliefs that had shaped our sense of national identity. Additionally, the essay serves as a reminder that we, Filipinos, are historically persevering and strong-minded. The lessons learned from those years of colonization were that all those efforts to keep people uneducated and impoverished, had failed. Nationalism eventually thrived and many of the predictions of Rizal came true. The country became independent after three centuries of abusive Spanish rule and five decades under the Americans.

SOBRE LA INDOLENCIA DE LOS FILIPINOS (The Indolence of the Filipinos)

This is said to be the longest essay written by Rizal, which was published in five installments in the La Solidaridad, from July 15 to September 15, 1890. The essay was described as a defense against the Spaniards who charged that the Filipinos are inherently lazy or indolent. The Indolence of the Filipinos is said to be a study of the causes why the people did not, as was said, work hard during the Spanish regime. Rizal pointed out that long before the coming of the Spaniards, the Filipinos were industrious and hardworking. The Spanish reign brought about a decline in economic activities because of the following causes: First, the establishment of the Galleon Trade cut-off all previous associations of the Philippines with other countries in Asia and the Middle East. As a result, business was only conducted with Spain through Mexico. Because of this, the small businesses and handicraft industries that flourished during the pre-Spanish period gradually disappeared. Second, Spain also extinguished the natives’ love of work because of the implementation of forced labor. Because of the wars between Spain and other countries in Europe as well as the Muslims in Mindanao, the Filipinos were compelled to work in shipyards, roads, and other public works, abandoning agriculture, industry, and commerce. Third, Spain did not protect the people against foreign invaders and pirates. With no arms to defend themselves, the natives were killed, their houses burned, and their lands destroyed. As a result of this, the Filipinos were forced to become nomads, lost interest in cultivating their lands or in rebuilding the industries that were shut down, and simply became submissive to the mercy of God. Fourth, there was a crooked system of education, if it was to be considered an education. What was being taught in the schools were repetitive prayers and other things that could not be used by the students to lead the country to progress. There were no courses in Agriculture, Industry, etc., which were badly needed by the Philippines during those times. Fifth, the Spanish rulers were a bad example to despise manual labor. The officials reported to work at noon and left early, all the while doing nothing in line with their duties. The women were seen constantly followed by servants who dressed them and fanned them – personal things which they ought to have done for themselves. Sixth, gambling was established and widely propagated during those times. Almost everyday there were cockfights, and during feast days, the government officials and friars were the first to engage in all sorts of bets and gambles. Seventh, there was a crooked system of religion. The friars taught the naïve Filipinos that it was easier for a poor man to enter heaven, and so they preferred not to work and remain poor so that they could easily enter heaven after they died. Lastly, the taxes were extremely high, so much so that a huge portion of what they earned went to the government or to the friars. When the object of their labor was removed and they were exploited, they were reduced to inaction. Rizal admitted that the Filipinos did not work so hard because they were wise enough to adjust themselves to the warm, tropical climate. “An hour’s work under that burning sun, in the midst of pernicious influences springing from nature in activity, is equal to a day’s labor in a temperate climate.” He explained, “violent work is not a good thing in tropical countries as it would be parallel to death, destruction, annihilation.” It can clearly be deduced from the writing that the cause of the indolence attributed to our race is Spain: When the Filipinos wanted to study and learn, there were no schools, and if there were any, they lacked sufficient resources and did not present more useful knowledge; when the Filipinos wanted to establish their businesses, there was not enough capital nor protection from the government; when the Filipinos tried to cultivate their lands and establish various industries, they were made to pay enormous taxes and were exploited by the foreign rulers.

LETTER TO THE YOUNG WOMEN OF MALOLOS

Jose Rizal’s legacy to Filipino women is embodied in his famous essay entitled, “To the Young Women of Malolos,” where he addresses all kinds of women – mothers, wives, the unmarried, etc. and expresses everything that he wishes them to keep in mind. On December 12, 1888, a group of 20 women of Malolos petitioned Governor-General Weyler for permission to open a night school so that they may study Spanish under Teodor Sandiko. Fr. Felipe Garcia, a Spanish parish priest in Malolos objected. But the young women courageously sustained their agitation for the establishment of the school. They then presented a petition to Governor Weyler asking that they should be allowed to open a night school (Capino et al, 1977). In the end, their request was granted on the condition that Señorita Guadalupe Reyes should be their teacher. Praising these young women for their bravery, Marcelo H. del Pilar requested Rizal to write a letter commending them for their extraordinary courage. Originally written in Tagalog, Rizal composed this letter on February 22, 1889 when he was in London, in response to the request of del Pilar. We know for a fact that in the past, young women were uneducated because of the principle that they would soon be wives and their primary career is to take care of the home and their children. In this letter, Rizal yearns that women should be granted the same opportunities given to men in terms of education. The salient points contained in this letter are as follows: 1. The rejection of the spiritual authority of the friars – not all of the priests in the country that time embodied the true spirit of Christ and His Church. Most of them were corrupted by worldly desires and used worldly methods to effect change and force discipline among the people. 2. The defense of private judgment 3. Qualities Filipino mothers need to possess – as evidenced by this portion of his letter, Rizal is greatly concerned of the welfare of the Filipino children and the homes they grow up in. 4. Duties and responsibilities of Filipino mothers to their children 5. Duties and responsibilities of a wife to her husband - Rizal states in this portion of his letter how Filipino women ought to be as wives, in order to preserve the identity of the race. 6. Counsel to young women on their choice of a lifetime partner

QUALITIES MOTHERS HAVE TO POSSESS

Rizal enumerates the qualities Filipino mothers have to possess: 1. Be a noble wife - that women must be decent and dignified, submissive, tender and loving to their respective husband. 2. Rear her children in the service of the state – here Rizal gives reference to the women of Sparta who embody this quality. Mothers should teach their children to love God, country and fellowmen. 3. Set standards of behavior for men around her - three things that a wife must instill in the mind of her husband: activity and industry; noble behavior; and worthy sentiments. In as much as the wife is the partner of her husband’s heart and misfortune, Rizal stressed on the following advices to a married woman: aid her husband, share his perils, refrain from causing him worry; and sweeten his moments of affliction.

RIZAL’S ADVICE TO UNMARRIED MEN AND WOMEN

Jose Rizal points out to unmarried women that they should not be easily taken by appearances and looks, because these can be very deceiving. Instead, they should take heed of men’s firmness of character and lofty ideas. Rizal further adds that there are three things that a young woman must look for a man she intends to be her husband: 1. A noble and honored name 2. A manly heart 3. A high spirit incapable of being satisfied with engendering slaves.

In summary, Rizal’s letter “To the Young Women of Malolos,” centers around five major points (Zaide &Zaide, 1999): 1. Filipino mothers should teach their children love of God, country and fellowmen. 2. Filipino mothers should be glad and honored, like Spartan mothers, to offer their sons in defense of their country. 4. Filipino women should educate themselves aside from retaining their good racial values. 5. Faith is not merely reciting prayers and wearing religious pictures. It is living the real Christian way with good morals and manners.

- Southeast Asia

- Philippines - History

JOSE RIZAL’S EXECUTION AND FILIPINO REBELLIONS AGAINST SPAIN

Dr josé rizal and the propagandist movement.

A powerful group of nationalists emerged in the late 19th century. The greatest and most famous of these was Dr José Rizal, doctor of medicine, poet, novelist, sculptor, painter, linguist, naturalist and fencing enthusiast. Executed by the Spanish in 1896, Rizal epitomised the Filipinos' dignified struggle for personal and national freedom. Just before facing the Spanish firing squad, Rizal penned a characteristically calm message of both caution and inspiration to his people: 'I am most anxious for liberties for our country, but I place as a prior condition the education of the people so that our country may have an individuality of its own and make itself worthy of liberties'.

Jose Rizal’s greatest impact on the development of a Filipino national consciousness was his publication of two novels–“Noli Me Tangere” (“Touch Me Not”) in 1886 and “El Filibusterismo” (“The “Reign of Greed”) in 1891. Rizal drew on his personal experiences and depicted the conditions of Spanish rule in the islands, particularly the abuses of the friars. Although the friars had Rizal's books banned, they were smuggled into the Philippines and rapidly gained a wide readership. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Rizal was a leader in the Propagandist Movement. To buttress his defense of the native’s pride and dignity as people, Rizal wrote three significant essays while abroad: The Philippines a Century hence, the Indolence of the Filipinos and the Letter to the Women of Malolos. These writings were his brilliant responses to the vicious attacks against the Indio and his culture. While in Hongkong, Rizal planned the founding of the Liga Filipina, a civil organization and the establishment of a Filipino colony in Borneo. The colony was to be under the protectorate of the North Borneo Company, he was granted permission by the British Governor to establish a settlement on a 190,000 acre property in North Borneo. The colony was to be under the protectorate of the North Borneo Company, with the "same privileges and conditions at those given in the treaty with local Bornean rulers". Governor Eulogio Despujol disapproved the project for obvious and self-serving reasons. He considered the plan impractical and improper that Filipinos would settle and develop foreign territories while the colony itself badly needed such developments. [Source: Jose Rizal University]

See Separate Article on JOSE RIZAL

Other important Propagandists included Graciano Lopez Jaena, a noted orator and pamphleteer who had left the islands for Spain in 1880 after the publication of his satirical short novel, Fray Botod (Brother Fatso), an unflattering portrait of a provincial friar. In 1889 he established a biweekly newspaper in Barcelona, La Solidaridad (Solidarity), which became the principal organ of the Propaganda Movement, having audiences both in Spain and in the islands. Its contributors included Rizal; Dr. Ferdinand Blumentritt, an Austrian geographer and ethnologist whom Rizal had met in Germany; and Marcelo del Pilar, a reformminded lawyer. Del Pilar was active in the antifriar movement in the islands until obliged to flee to Spain in 1888, where he became editor of La Solidaridad and assumed leadership of the Filipino community in Spain. *

The Propaganda Movement languished after Rizal's arrest in 1892 and the collapse of the Liga Filipina. La Solidaridad went out of business in November 1895, and in 1896 both del Pilar and Lopez Jaena died in Barcelona, worn down by poverty and disappointment. An attempt was made to reestablish the Liga Filipina, but the national movement had become split between ilustrado advocates of reform and peaceful evolution (the compromisarios, or compromisers) and a plebeian constituency that wanted revolution and national independence. Because the Spanish refused to allow genuine reform, the initiative quickly passed from the former group to the latter. *

Andres Bonifacio and Katipunan

After Rizal's exile, Andres Bonifacio, a self-educated man of humble origins, founded an aggresive secret society, the Katipunan (KKK) — short for the Kataastaasan Kagalanggalangang Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan (Highest and Most Respected Society of the Sons of the Nation) — in Manila. This organization, modeled in part on Masonic lodges, was committed to winning independence from Spain. Rizal, Lopez Jaena, del Pilar, and other leaders of the Propaganda Movement had been Masons, and Masonry was regarded by the Catholic Church as heretical. The Katipunan, like the Masonic lodges, had secret passwords and ceremonies, and its members were organized into ranks or degrees, each having different colored hoods, special passwords, and secret formulas. New members went through a rigorous initiation, which concluded with the pacto de sangre, or blood compact. [Source: Library of Congress *]

The Katipunan spread gradually from the Tondo district of Manila, where Bonifacio had founded it, to the provinces, and by August 1896 — on the eve of the revolt against Spain — it had some 30,000 members, both men and women. Most of them were members of the lower-and lower-middle-income strata, including peasants. The nationalist movement had effectively moved from the closed circle of prosperous ilustrados to a truly popular base of support. *

According to Lonely Planet: The Katipunan “secretly built a revolutionary government in Manila, with a network of equally clandestine provincial councils. Complete with passwords, masks and coloured sashes denoting rank, the Katipunan's members (both men and women) peaked at an estimated 30, 000 in mid-1896.”

On June 21, 1896. Dr. Pio Valenzuela, Bonifacio’s emissary, visited Rizal in Dapitan and informed him of the plan of the Katipunan to launch a revolution. Rizal objected to Bonifacio’s bold project stating that such would be a veritable suicide. Rizal stressed that the Katipunan leaders should do everything possible to prevent premature flow of native blood. Valenzuela, however, warned Rizal that the Revolution will inevitably break out if the Katipunan would be discovered. Sensing that the revolutionary leaders were dead set on launching their audacious project, Rizal instructed Valenzuela that it would be for the best interests of the Katipunan to get first the support of the rich and influential people of Manila to strengthen their cause. He further suggested that Antonio Luna with his knowledge of military science and tactics, be made to direct the military operations of the Revolution. [Source: Jose Rizal University]

Jose Rizal and the 1896 Uprising

During the early years of the Katipunan, Rizal remained in exile at Dapitan. He had promised the Spanish governor that he would not attempt an escape, which, in that remote part of the country, would have been relatively easy. Such a course of action, however, would have both compromised the moderate reform policy that he still advocated and confirmed the suspicions of the reactionary Spanish. Whether he came to support Philippine independence during his period of exile is difficult to determine. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Rizal retained, to the very end, a faith in the decency of Spanish "men of honor," which made it difficult for him to accept the revolutionary course of the Katipunan. Revolution had broken out in Cuba in February 1895, and Rizal applied to the governor to be sent to that yellow fever-infested island as an army doctor, believing that it was the only way he could keep his word to the governor and yet get out of his exile. His request was granted, and he was preparing to leave for Cuba when the Katipunan revolt broke out in August 1896. An informer had tipped off a Spanish friar about the society's existence, and Bonifacio, his hand forced, proclaimed the revolution, attacking Spanish military installations on August 29, 1896. Rizal was allowed to leave Manila on a Spanish steamship. The governor, however, apparently forced by reactionary elements, ordered Rizal's arrest en route, and he was sent back to Manila to be tried by a military court as an accomplice of the insurrection. *

The rebels were poorly led and had few successes against colonial troops. Only in Cavite Province did they make any headway. Commanded by Emilio Aguinaldo, the twenty-seven-year-old mayor of the town of Cavite who had been a member of the Katipunan since 1895, the rebels defeated Civil Guard and regular colonial troops between August and November 1896 and made the province the center of the revolution. *

According to Lonely Planet: In August 1886, the Spanish got wind of the coming revolution (from a woman's confession to a Spanish friar, according to some accounts) and the Katipunan leaders were forced to flee the capital. Depleted, frustrated and poorly armed, the Katipuneros took stock in nearby Balintawak, a baryo (district) of Caloocan, and voted to launch the revolution regardless. With the cry 'Mabuhay ang Pilipinas!' (Long live the Philippines!), the Philippine Revolution lurched into life following the incident that is now known as the Cry of Balintawak. The shortage of weapons among the Filipinos meant that many fighters were forced to pluck their first gun from the hands of their enemies. So acute was the shortage of ammunition for these weapons that some (many of them children) were given the job of scouring battle sites for empty cartridges. These cartridges would then be painstakingly repacked using homemade gunpowder. [Source: Lonely Planet]

Jose Rizal's Execution

In November 1886, Rizal was arrested for his alleged involvement in 1896 Uprising. After the uprising Rizal’s enemies lost no time in pressing him down. Witnesses that linked him with the revolt were rounded up but these witnessed were not cross examined nor did they face Rizal directly. Rizal was imprisoned in Fort Santiago. In his prison cell, he wrote an untitled poem, now known as "Ultimo Adios" which is considered a masterpiece and a living document expressing not only the hero’s great love of country but also that of all Filipinos.

Under a new governor, who apparently had been sponsored as a hard-line candidate by the religious orders, Rizal was brought before a military court on fabricated charges of involvement with the Katipunan. The events of 1872 repeated themselves. A brief trial was held on December 26 and — with little chance to defend himself — Rizal was found guilty of rebellion, sedition and of forming illegal association and sentenced to death. On December 30, 1896, he was brought out to the Luneta and executed by a firing squad at Bagumbayan Field. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Dec. 30, 1986. 4:00 – 5:00 a.m. : Rizal picks up Imitation of Christ, reads, meditates and then writes in Kempis’ book a dectation to his wife Josephine and by this very act in itself he gives to her their only certificate of marriage. — 5:00 – 6:15 : Rizal washes up, takes breakfast, attends to his personal needs. Writes a letter to his parents. Reads Bible and meditates. Josephine is prohibited by the Spanish officers from seeing Rizal, according to Josephine’s testimony to R. Wildman in 1899. — 6:15 – 7:00 : Rizal walks to the place of execution between Fr. March and Fr. Vilaclara with whom he converses. Keeps looking around as if seeking or expecting to see someone. His last word, said in a loud voice: "It is finished" — 7:00 – 7:03 : Sounds of guns. Rizal vacillates, turns halfway around, falls down backwards and lies on the ground facing the sun. Silence. Shouts of vivas for Spain. [Source: Jose Rizal University ]

Jose Rizal's Final Hours

Dec. 29, 1896. 6:00 – 7:00 a.m. : Sr. S. Mataix asks Rizal’s permission to interview him. Capt. — Dominguez reads death sentence to Rizal. Source of information: cablegram of Mataix to EL Heraldo — De Madrid, "Notes" of Capt. Dominguez and Testimony of Lt. Gallegos. — 7:00 – 8:00 a.m. : Rizal is transferred to his death cell. Fr. Saderra talks briefly with Rizal. Fr. Viza — presents statue of the Sacred hearth of Jesus and medal of Mary. Rizal rejects the letter, saying, "Im little of a Marian, Father." Source: Fr. Viza. — 8:00 – 9:00 a.m. : Rizal is shares his milk and coffee with Fr. Rosell. Lt. Andrade and chief of Artillery come to visit Rizal who thanks each of them. Rizal scribbles a note inviting his family it visit him. Sources: Fr. Rosell and letter of Invitation. — 9:00 – 10:00 a.m. : Sr. Mataix, defying stringent regulation, enters death cell and interviews Rizal in the presence of Fr. Rosell. Later, Gov. Luengo drops in to join the conversation. Sources: Letter of Mataix ti Retana Testimony of Fr. Rosell. — 10:00 – 11:00 a.m. : Fr. Faura persuades Rizal to put down his rancours and order to marry josephine canonically. a heated discussion on religion occurs between them ion the hearing of Fr. Rosell. Sources: El Imparcial and Fr. Rosell . — 11:00 – 12:00 noon. : Rizal talks on "various topics" in a long conversation with Fr. Vilaclara who will later conclude (with Fr. Balaguer, who is not allowed to enter the death cell) that Rizal is either to Prostestant or rationalist who speaks in "a very cold and calculated manner" with a mixture of a "strange piety." No debate or discussion on religion is recorded to have taken place between the Fathers mentioned and Rizal. Sources: El Imarcial and Rizal y su Obra. [Source: Jose Rizal University ]

12:00 – 1:00 p.m. : Rizal reads Bible and Imitation of Christ by Kempis, then meditates. Fr. Balaguer reports to the Archbishop that only a little hope remains that Rizal is going to retract for Rizal was heard saying that he is going to appear tranquilly before God. Sources: Rizal’s habits and Rizal y su Obra. — 1:00 – 2:00 p.m. : Rizal denies (probably, he is allowed to attend to his personal necessities). Source: "Notes" of Capt. Dominguez. — 2:00 – 3:00 p.m. : Rizal confers with Fr. March and Fr. Vilaclara. Sources: "Notes" of Capt. Dominguez in conjunction with the testimonies of Fr. Pi and Fr. Balaguer. — 3:00 – 4:00 p.m. : Rizal reads verses which he had underlined in Eggers german Reader, a book which he is going to hand over to his sisters to be sent to Dr. Blumentritt through F. Stahl. He "writes several letters . . .,with his last dedications," then he "rest for a short." Sources: F. Stahl and F. Blumentritt, Cavana (1956) – Appendix 13, and the "Notes" of Capt. Dominguez. — 4:00 – 5:30 p.m. : Capt. Dominguez is moved with compassion at the sight of Rizal’s kneeling before his mother and asking pardon. Fr. Rosell hears Rizal’s farewell to his sister and his address to those presents eulogizing the cleverness of his nephew. The other sisters come in one by one after the other and to each Rizal’s gives promises to give a book, an alcohol burner, his pair of shoes, an instruction, something to remember. Sources "notes" of Capt. Dominguez and Fr. Rosell, Diaro de Manila. — 5:30 – 6:00 p.m.: The Dean of the Cathedral, admitted on account of his dignity, comes to exchange views with Rizal. Fr. Rosell hears an order given to certain "gentlemen" and "two friars" to leave the chapel at once. Fr. Balaguer leaves Fort Santiago. Sources: Rev. Silvino Lopez-Tuñon, Fr. Rosell, Fr. Serapio Tamayo, and Sworn Statement of Fr. Balaguer. — 6:00 – 7:00 p.m.: Fr. Rosell leaves Fort Santiago and sees Josephine Bracken. Rizal calls for Josephine and then they speak to each for the last time. Sources: Fr. Rosell, El Imparcial, and Testimony of Josephine to R. Wildman in 1899. — 7:00 – 8:00 p.m. : Fr. Faura returns to console Rizal and persuades him once more to trust him and the other professors at the Ateneo. Rizal is emotion-filled and, after remaining some moments in silence, confesses to Fr. Faura. Sources: El Imparcial.

8:00 – 9:00 p.m. : Rizal rakes supper (and, most probably, attends to his personal needs). Then, he receives Bro. Titllot with whom he had a very "tender" (Fr. Balaguer) or "useful" (Fr. Pi) interview. Sources: Separate testimonies of Fr. Balaguer and Fr. Pi on the report of Bro. Titllot; Fisal Castaño. — 9:00 – 10:00 p.m.: Fiscal Castaño exchanges views with Rizal regarding their respective professors. Sources: Fiscal Castaño. — 10:00 – 11:00 p.m. : Rizal manifests strange reaction, asks guards for paper and pen. From rough drafts and copies of his poem recovered in his shoes, the Spaniards come to know that Rizal is writing a poem. Sources: El Imparcial and Ultimo Adios; probably, Fiscal Castaño. — 11:00 – 12:00 midnight: Rizal takes time to his hide his poem inside the alcohol burner. It has to be done during night rather than during daytime because he is watched very carefully. He then writes his last letter to brother Paciano. Sources: Testimonies and circumstantial evidence. — 12:00 – 4:00 a.m. : Rizal sleeps restfully because his confidence in the goodness of God and the justness of his cause gives him astounding serenity and unusual calmness.

Filipino Rebellion After Rizal's Execution

The Philippine independence struggle turned more violent after Rizal's death. It was led first by Andres Bonifacio and later by Emilio Aguinaldo. Emilio Aguinaldo was a peasant worker and an idealist young firebrand. Rizal's death filled the rebels with new determination, but the Katipunan was becoming divided between supporters of Bonifacio, who revealed himself to be an increasingly ineffective leader, and its rising star, Aguinaldo. At a convention held at Tejeros, the Katipunan's headquarters in March 1897, delegates elected Aguinaldo president and demoted Bonifacio to the post of director of the interior. Bonifacio withdrew with his supporters and formed his own government. After fighting broke out between Bonifacio's and Aguinaldo's troops, Bonifacio was arrested, tried, and on May 10, 1897, executed by order of Aguinaldo. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Aguinaldo He extracted some concessions from the Spaniards in 1897 and declared Philippines independence on June, 12, 1898 from the balcony of his home in Cavite and established himself as president of an ill-fated provisional Philippine Republic after Filipinos drove the Spanish from most of the archipelago. Through their revolutionary proclamation, Filipinos claim that the Philippines was the first democratic republic in Asia. In one battle unarmed rebels on the island of Negros tricked the Spanish into retreating by launching an attack with “cannons” made rolled-up palm-leaf mats painted black and “bayonet rifles” constructed from bamboo.

As 1897 wore on, Aguinaldo himself suffered reverses at the hands of Spanish troops, being forced from Cavite in June and retreating to Biak-na-Bato in Bulacan Province. The futility of the struggle was becoming apparent on both sides. Although Spanish troops were able to defeat insurgents on the battlefield, they could not suppress guerrilla activity. In August armistice negotiations were opened between Aguinaldo and a new Spanish governor.

After three years of bloodshed, most of it Filipino, a Spanish-Filipino peace pact was signed in Hong Kong in December, 1897. According to the agreement the Spanish governor of the Philippines would pay Aguinaldo the equivalent of US$800,000, and the rebel leader and his government would go into exile. Aguinaldo established himself in Hong Kong, and the Spanish bought themselves time. Within the year, however, their more than three centuries of rule in the islands would come to an abrupt and unexpected end. *

According to Lonely Planet: “Predictably, the pact's demands satisfied nobody. Promises of reform by the Spanish were broken, as were promises by the Filipinos to stop their revolutionary plotting. The Filipino cause attracted huge support from the Japanese, who tried unsuccessfully to send money and two boatloads of weapons to the exiled revolutionaries in Hong Kong.

When the Spanish-American War broke out in April 1898, Spain’s fleet was easily defeated at Manila. Aguinaldo returned, and his 12,000 troops kept the Spanish forces bottled up in Manila until U.S. troops landed. The Spanish cause was doomed, but the Americans did nothing to accommodate the inclusion of Aguinaldo in the succession. Fighting between American and Filipino troops broke out almost as soon as the Spanish had been defeated. Aguinaldo issued a declaration of independence on June 12, 1898. However, the Treaty of Paris, signed on December 10, 1898, by the United States and Spain, ceded the Philippines, Guam, and Puerto Rico to the United States, recognized Cuban independence, and gave US$20 million to Spain. A revolutionary congress convened at Malolos, north of Manila, promulgated a constitution on January 21, 1899, and inaugurated Aguinaldo as president of the new republic two days later. Hostilities broke out in February 1899, and by March 1901 Aguinaldo had been captured and his forces defeated. Despite Aguinaldo’s call to his compatriots to lay down their arms, insurgent resistance continued until 1903. The Moros, suspicious of both the Christian Filipino insurgents and the Americans, remained largely neutral, but eventually their own armed resistance had to be subjugated, and Moro territory was placed under U.S. military rule until 1914. *

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Philippines Department of Tourism, Compton’s Encyclopedia, The Guardian, National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, and various books, websites and other publications.

Last updated June 2015

- Google+

Page Top

This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been authorized by the copyright owner. Such material is made available in an effort to advance understanding of country or topic discussed in the article. This constitutes 'fair use' of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit. If you wish to use copyrighted material from this site for purposes of your own that go beyond 'fair use', you must obtain permission from the copyright owner. If you are the copyright owner and would like this content removed from factsanddetails.com, please contact me.

Search form

- ADVERTISE here!

- How To Contribute Articles

- How To Use This in Teaching

- To Post Lectures

Sponsored Links

You are here, our free e-learning automated reviewers.

- Mathematics

- Home Economics

- Physical Education

- Music and Arts

- Philippine Studies

- Language Studies

- Social Sciences

- Extracurricular

- Preschool Lessons

- Life Lessons

- AP (Social Studies)

- EsP (Values Education)

Jose Rizal’s Essays and Articles

Refer these to your siblings/children/younger friends:

HOMEPAGE of Free NAT Reviewers by OurHappySchool.com (Online e-Learning Automated Format)

HOMEPAGE of Free UPCAT & other College Entrance Exam Reviewers by OurHappySchool.com (Online e-Learning Automated Format)

Articles in Diariong Tagalog

“El Amor Patrio” (The Love of Country)

This was the first article Rizal wrote in the Spanish soil. Written in the summer of 1882, it was published in Diariong Tagalog in August. He used the pen name “Laong Laan” (ever prepared) as a byline for this article and he sent it to Marcelo H. Del Pilar for Tagalog translation.

Written during the Spanish colonization and reign over the Philippine islands, the article aimed to establish nationalism and patriotism among the natives. Rizal extended his call for the love of country to his fellow compatriots in Spain, for he believed that nationalism should be exercised anywhere a person is.

“Revista De Madrid” (Review of Madrid)

This article written by Rizal on November 29, 1882 wasunfortunatelyreturned to him because Diariong Tagalog had ceased publications for lack of funds.

Articles in La Solidaridad

“Los Agricultores Filipinos” (The Filipino Farmers)

This essay dated March 25, 1889 was the first article of Rizal published in La Solidaridad. In this writing, he depicted the deplorable conditions of the Filipino farmers in the Philippines, hence the backwardness of the country.

“A La Defensa” (To La Defensa)

This was in response to the anti-Filipino writing by Patricio de la Escosura published by La Defensa on March 30, 1889 issue. Written on April 30, 1889, Rizal’s article refuted the views of Escosura, calling the readers’ attention to the insidious influences of the friars to the country.

“Los Viajes” (Travels)

Published in the La Solidaridad on May 15, 1889, this article tackled the rewards gained by the people who are well-traveled to many places in the world.

“La Verdad Para Todos” (The Truth for All)

This was Rizal’s counter to the Spanish charges that the natives were ignorant and depraved. On May 31, 1889, it was published in the La Solidaridad.

"Vicente Barrantes’ Teatro Tagalo”

The first installment of Rizal’s “Vicente Barrantes” was published in the La Solidaridad on June 15, 1889. In this article, Rizal exposed Barrantes’ lack of knowledge on the Tagalog theatrical art.

“Defensa Del Noli”

The manuscripts of the “Defensa del Noli” was written on June 18, 1889. Rizal sent the article to Marcelo H. Del Pilar, wanting it to be published by the end of that month in the La Solidaridad.

“Verdades Nuevas”(New Facts/New Truths)

In this article dated July 31, 1889, Rizal replied to the letter of Vicente Belloc Sanchez which was published on July 4, 1889 in ‘La Patria’, a newspaper in Madrid. Rizal addressed Sanchez’s allegation that provision of reforms to the Philippines would devastate the diplomatic rule of the Catholic friars.

“Una Profanacion” (A Desecration/A Profanation)

Published on July 31, 1889, this article mockingly attacked the friars for refusing to give Christian burial to Mariano Herbosa, Rizal’s brother in law, who died of cholera in May 23, 1889. Being the husband of Lucia Rizal (Jose’s sister), Herbosa was denied of burial in the Catholic cemetery by the priests.

“Crueldad” (Cruelty),

Dated August 15, 1889, this was Rizal’s witty defense of Blumentritt from the libelous attacks of his enemies.

“Diferencias” (Differences)

Published on September 15, 1889, this article countered the biased article entitled “Old Truths” which was printed in La Patria on August 14, 1889. “Old Truths” ridiculed those Filipinos who asked for reforms.

“Inconsequencias” (Inconsequences)

The Spanish Pablo Mir Deas attacked Antonio Luna in the Barcelona newspaper “El Pueblo Soberano”. As Rizal’s defense of Luna, he wrote this article which was published on November 30, 1889.

“Llanto Y Risas” (Tears and Laughter)

Dated November 30, 1889, this article was a condemnation of the racial prejudice of the Spanish against the brown race. Rizal remembered that he earned first prize in a literary contest in 1880. He narrated nonetheless how the Spaniard and mestizo spectators stopped their applause upon noticing that the winner had a brown skin complexion.

“Filipinas Dentro De Cien Anos” (The Philippines within One Hundred Years)

This was serialized in La Solidaridad on September 30, October 31, December 15, 1889 and February 15, 1890. In the articles, Rizal estimated the future of the Philippines in the span of a hundred years and foretold the catastrophic end of Spanish rule in Asia. He ‘prophesied’ Filipinos’ revolution against Spain, winning their independence, but later the Americans would come as the new colonizer

The essay also talked about the glorious past of the Philippines, recounted the deterioration of the economy, and exposed the causes of natives’ sufferings under the cruel Spanish rule. In the essay, he cautioned the Spain as regards the imminent downfall of its domination. He awakened the minds and the hearts of the Filipinos concerning the oppression of the Spaniards and encouraged them to fight for their right.

Part of the essays reads, “History does not record in its annals any lasting domination by one people over another, of different races, of diverse usages and customs, of opposite and divergent ideas. One of the two had to yield and succumb.” The Philippines had regained its long-awaited democracy and liberty some years after Rizal’s death. This was the realization of what the hero envisioned in this essay.

Dated January 15, 1890, this article was the hero’s reply to Governor General Weyler who told the people in Calamba that they “should not allow themselves to be deceived by the vain promises of their ungrateful sons.” The statement was made as a reaction to Rizal’s project of relocating the oppressed and landless Calamba tenants to North Borneo.

“Sobre La Nueva Ortografia De La Lengua Tagala” (On The New Orthography of The Tagalog Language)

Rizal expressed here his advocacy of a new spelling in Tagalog. In this article dated April 15, 1890, he laid down the rules of the new Tagalog orthography and, with modesty and sincerity, gave the credit for the adoption of this new orthography to Dr. Trinidad H. Pardo de Tavera, author of the celebrated work “El Sanscrito en la Lengua Tagala” (Sanskrit in the Tagalog Language) published in Paris, 1884.

“I put this on record,” wrote Rizal, “so that when the history of this orthography is traced, which is already being adopted by the enlightened Tagalists, that what is Caesar’s be given to Caesar. This innovation is due solely to Dr. Pardo de Tavera’s studies on Tagalismo. I was one of its most zealous propagandists.”

“Sobre La Indolencia De Los Filipinas” (The Indolence of the Filipinos)

This logical essay is a proof of the national hero’s historical scholarship. The essay rationally countered the accusations by Spaniards that Filipinos were indolent (lazy) during the Spanish reign. It was published in La Solidaridad in five consecutive issues on July (15 and 31), August (1 and 31) and September 1, 1890.

Rizal argued that Filipinos are innately hardworking prior to the rule of the Spaniards. What brought the decrease in the productive activities of the natives was actually the Spanish colonization. Rizal explained the alleged Filipino indolence by pointing to these factors: 1) the Galleon Trade destroyed the previous links of the Philippines with other countries in Asia and the Middle East, thereby eradicating small local businesses and handicraft industries; 2) the Spanish forced labor compelled the Filipinos to work in shipyards, roads, and other public works, thus abandoning their agricultural farms and industries; 3) many Filipinos became landless and wanderers because Spain did not defend them against pirates and foreign invaders; 4) the system of education offered by the colonizers was impractical as it was mainly about repetitive prayers and had nothing to do with agricultural and industrial technology; 5) the Spaniards were a bad example as negligent officials would come in late and leave early in their offices and Spanish women were always followed by servants; 6) gambling like cockfights was established, promoted, and explicitly practiced by Spanish government officials and friars themselves especially during feast days; 7) the crooked system of religion discouraged the natives to work hard by teaching that it is easier for a poor man to enter heaven; and 8) the very high taxes were discouraging as big part of natives’ earnings would only go to the officials and friars.

Moreover, Rizal explained that Filipinos were just wise in their level of work under topical climate. He explained, “violent work is not a good thing in tropical countries as it is would be parallel to death, destruction, annihilation. Rizal concluded that natives’ supposed indolence was an end-product of the Spanish colonization.

Other Rizal’s articles which were also printed in La Solidaridad were “A La Patria” (November 15, 1889), “Sin Nobre” (Without Name) (February 28, 1890), and “Cosas de Filipinas” (Things about the Philippines) (April 30, 1890).

Historical Commentaries Written in London

This historical commentary was written by Rizal in London on December 6, 1888.

“Acerca de Tawalisi de Ibn Batuta”

This historical commentaryis believed to form part of ‘Notes’ (written incollaboration with A.B. Meyer and F. Blumentritt) on a Chinese code in the Middle Ages, translated from the German by Dr. Hirth. Written on January 7, 1889, the article was about the “Tawalisi” which refers to the northern part of Luzon or to any of the adjoining islands.

It was also in London where Rizal penned the following historical commentaries: “La Political Colonial On Filipinas” (Colonial Policy In The Philippines), “Manila En El Mes De Diciembre” (December , 1872), “Historia De La Familia Rizal De Calamba” (History Of The Rizal Family Of Calamba), and “Los Pueblos Del Archipelago Indico (The People’s Of The Indian Archipelago )

Other Writings in London

“La Vision Del Fray Rodriguez” (The Vision of Fray Rodriguez)

Jose Rizal, upon receipt of the news concerning Fray Rodriguez’ bitter attack on his novel Noli Me Tangere, wrote this defense under his pseudonym “Dimas Alang.” Published in Barcelona, it is a satire depicting a spirited dialogue between the Catholic saint Augustine and Rodriguez. Augustine, in the fiction, told Rodriguez that he (Augustine) was commissioned by God to tell him (Rodriguez) of his stupidity and his penance on earth that he (Rodriguez) shall continue to write more stupidity so that all men may laugh at him. In this pamphlet, Rizal demonstrated his profound knowledge in religion and his biting satire.

“To The Young Women of Malolos”

Originally written in Tagalog, this famous essay directly addressed to the women of Malolos, Bulacan was written by Rizal as a response to Marcelo H. Del Pilar’s request.