Legitimacy of the System: Implications of Government-Endorsed Disloyalty

Article sidebar, main article content.

On April 3, 1996, after nearly eighteen years of bombings that left three dead and twenty-nine injured, federal agents arrested Ted Kacyznski, also known as “The Unabomber,” in his isolated cabin in Lincoln, Montana (Brooke). Despite being the longest and most expensive FBI manhunt to date with a record-setting $1 million reward, the search for the mysterious Unabomber was brought to a close only after his younger brother, David Kaczynski, came forward with his suspicions that Ted could be the Unabomber (Graham). David had noticed striking similarities between the “Unabomber’s Manifesto,” published in 1995, and letters his older brother had sent him over the years (Graham).

The public was captivated by this modern betrayal-epic, a “benevolent Cain and Abel” (Glaberson). In an interview, David described the agonizing position he and his wife were placed in, forced to choose between his brother’s life and that of his next victim: “We found ourselves in a position where anything we did could lead to somebody’s death. I can’t tell you what that felt like” (Graham). His decision was praised by many. He was hailed for “doing the only honest thing any sane person could have done” and forty-four-year-old West Hills resident Barbara Frank remarked, “I don’t think I could live with myself knowing a relative was responsible for causing misery and destruction to other people” (Shuster). A somewhat surprised David reported that “not only haven’t we gotten a lot of angry or abusive letters, but we’ve really gotten a lot of letters from people who thanked us for having the courage to do what we did” (Graham). To most, the prospect of another dead victim was enough to justify the brotherly betrayal.

Even so, the actions of the younger Kaczynski were not universally hailed. David Letterman dubbed him “The Unasquealer” and on the Tuesday after the story broke, CNN’s “Talk Back Live” debated “whether he was saint or snitch” (Dowd). Others, like mechanic Dave Kubert, remarked that these situations are “still something to be resolved within the family” (Shuster). Explaining this kind of negative reaction to David Kacyznski’s actions, New York Times reporter Maureen Dowd wrote: “Many Americans subscribe to the sentiment expressed by E. M. Forster: ‘If I had to choose between betraying my country and betraying my friend, I hope I should have the guts to betray my country.’” This disapproving group placed the value of family loyalty—and their disdain for snitching—above not only the million dollar reward, but also above the potential consequences of remaining silent.

David Kaczynski quickly donated the FBI’s reward to the families of his brother’s victims (Brooke). David likely felt that keeping such a reward would be inappropriate, as his actions were motivated by concern for potential victims rather than by personal gain. Imagine the public outcry against the younger Kaczynski had he accepted the FBI’s proverbial thirty pieces of silver. Yet this purchase of betrayal is exactly the type of transaction that occurs every day within the criminal justice system. Criminal informants regularly “flip” on their associates in return for some type of reward—often consisting of heavily reduced sentences. By rewarding those criminals who provide information, the government is encouraging betrayal and sanctioning disloyalty. Regardless of the individual morality of David Kaczynski and of the more self-interested (and numerous) criminal informants, it is worth considering the implications of the justice system’s endorsement of disloyalty and how this endorsement reflects on our societal values and the perceived legitimacy of the legal system.

The negative responses to David Kacyznski’s decision to turn in his brother reflect not only the collective value we place on family loyalty, but also the extreme negative sentiment commonly felt for snitches and informants of all sorts. In the Divine Comedy , Dante reserves the ninth and lowest circle of hell for traitors and betrayers, who are damned instantly from the moment that “any soul becomes a traitor . . . then a demon takes its body away—and keeps that body in his power until its years have run their course completely” (207). At the center of the ninth circle, Dante describes the three-faced Satan who in each mouth “with gnashing teeth . . . tore to bits a sinner,” specifically the infamous traitors Brutus, Cassius, and, worst of all, Judas Iscariot (210). Thus the betrayers of Dante’s past and present (for he places many of his treacherous contemporaries in the frozen lake Cocytus, as well) are given a special place in Hell, closest to the Devil himself. This placement expresses a disdain for disloyalty that extends throughout history.

Columbia law professor George Fletcher acknowledges this deep, negative sentiment in his book, Loyalty: An Essay on the Morality of Relationships , when he writes: “Some of the strongest moral epithets in the English language are reserved for the weak who cannot meet the threshold of loyalty: They commit adultery, betrayal and treason” (8). Fletcher notes that these epithets for “the sin of betrayal” are “worse than murder, worse than incest” and invite “universal scorn” of the traitor (41). Why such a strong response to disloyalty? Fletcher argues that “loyalty enables individuals to grasp the humanity of their fellow citizens and to treat them as bearers of equal rights” (21). Thus, the heavy condemnation of disloyalty serves as a defense mechanism to protect the trust-based, interpersonal relationships that society is built upon. Any actions taken to jeopardize that trust must be considered carefully.

One such action is “snitching” or, more specifically, acting as a criminal informant. In 1999, Fordham law professor Ian Weinstein estimated that “twenty percent of all defendants ally themselves with the prosecutor (and many more try)” (617). Snitching alone destroys trust, but this type of widespread government endorsement of the practice has amplified and institutionalized its consequences. This practice does not just undermine the trust of a single relationship; rather, entire communities are suffering the consequences. Loyola law professor and ex-Federal Public Defender Alexandra Natapoff chronicles this phenomenon in her paper, “Snitching: The Institutional and Communal Consequences.” She argues that “criminally active informants exacerbate a culture in which crime is commonplace and tolerated” and, in communities where “approximately one in twelve men are active informants,” it is no surprise that there is immense damage done to “the fabric of interpersonal trust and psychological security” (687-690). Not only does snitching destroy trust within a community, but its negative consequences also have a severe impact on citizens’ views of the legal system and undermine their confidence that the government is acting in their best interest. Society must believe that institutions such as the legal system legitimately reflect their goals and values; otherwise, the only incentive to obey is fear of punishment.

Why is disloyalty encouraged and rewarded among criminals while elsewhere (e.g., playground tattletales or the police “blue wall of silence”) it is so heavily condemned? Mostly because society fears the harm criminals pose. Due to heavy caseloads and minimal supplementary evidence, collecting informant testimony is often the only way that law enforcement officials can prosecute offenders (Richman 1). As harmful as snitching is to a community, it would be equally unacceptable to let unknown numbers of offenders go unpunished, which, unhelpfully, would also result in a decreased perception of the legal system’s legitimacy.

The practice of using criminal informants clearly reflects the hierarchy of moral values in our society. In his paper, “When Morality Opposes Justice,” American psychologist Jonathan Haidt describes his theory that there are “five psychological systems that provide the foundations for the world’s many moralities” (1). Haidt believes that these five foundations are based on concerns for harm/care, fairness/reciprocity, in-group/loyalty, authority/respect, and purity/sanctity, and that different cultures and groups develop these virtues (2). If we take the legal system’s practice of using criminal informants as an extension of our society’s values (admittedly, a substantial assumption), we can uncover a moral hierarchy. Concerns for harm at the hands of criminals exceed the importance placed on loyalty to a community. The sphere of fairness presents a more complicated issue. On the one hand, informing is justified as it brings criminals to justice and makes them pay for their actions. On the other hand, “any system that rewards cooperation . . . can favor the most culpable defendants,” a phenomenon known as “inverted sentencing” (Richman 1), which throws the fairness of the practice into question. Judging from these observations about our legal system, it seems that of Haidt’s foundations, society’s concern for preventing harm takes precedence over the moral spheres of loyalty and fairness.

Why is this so? And do these conclusions reflect society’s true values, especially considering that a universal disdain for informants implies that loyalty is of no minor significance? In his paper, “Coercive Sentencing,” Michigan law professor Steven Nemerson summarizes the utilitarian influences on our justice system and their use as justification for rewarding cooperating defendants. Nemerson argues that, in its simplest terms, “utilitarianism holds that an act is morally acceptable if it maximizes overall social well-being, measured in terms of people’s happiness” and that “the supplying of information and testimony by defendants and their use as active informants serves to detect and prevent crime,” which increases social well-being (684). With this utilitarian calculus in mind, it is easy to see how crime’s explicit immorality and its obvious negative effects on social happiness justify the overriding importance the legal system places on the moral principle of preventing harm, at the expense of personal loyalties.

However, as the controversy in the Unabomber case demonstrates, not all Americans agree with this ordering, and for them, the legal system fails to reflect their moral values, an extremely dangerous prospect to any society. Also, as Professor Natapoff demonstrates, there are less apparent damages that result from the practice of widespread informant use and the normative message that this practice sends by rewarding disloyalty. Not only does it run the risk of undermining Haidt’s core values of fairness and loyalty, but the communities that suffer from the practice also lose their respect for authority and law enforcement, and thus another of Haidt’s principles (authority/respect) is compromised. The practice of rewarding informants with reduced sentences may be a necessity to the prosecution of many criminals, but the dangers of undermining three out of Haidt’s five foundations for all social values cannot be ignored.

The practice of using criminal informants thus presents something of a moral paradox. Experimental psychologist and author Stephen Pinker observes that most people believe that “not only is it allowable to inflict pain on a person who has broken a moral rule; it is wrong not to, to ‘let them get away with it'” (2). Our justice system is designed to punish those guilty of breaking the law (society’s moral rules) and, in doing so, it employs a number of different tactics, including the rewarding of informants. However, in its efforts to “inflict pain” on criminal offenders, the justice system allows cooperators to “get away with it.” This type of self-defeating paradox is exactly what makes the use of informants such a dangerous practice. In attempting to defend communities from harm, the legal system undermines the interpersonal trust that those groups are based on. From a utilitarian view, it is not even clear if the crime prevented through informant testimony outweighs the informant’s own criminal activity that goes overlooked, or the aforementioned community harm. By striking deals with those criminals who are often the most culpable, the legitimacy of the justice system—which may not even reflect its constituents’ own moral values—is called into question.

The legal system is in many ways sensitive to the same forces as the economy; its power is ultimately based on citizens’ confidence that the system works. That confidence weakens when snitching undermines the essential trust that, as Fletcher said, “enables individuals to grasp the humanity of their fellow citizens” (21). If the use of informants is indeed a necessary evil, it is one that must be handled carefully so that faith in the system does not dwindle.

WORKS CITED

Brooke, James. “Unabomber’s Kin Collect Reward of $1 Million for Turning Him In.” The New York Times . 21 Aug. 1998. 5 Dec. 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/1998/08/21/us/unabomber-s-kin-collect-reward-of-1-million-for-turning-him-in.html.

Dante Alighieri. The Divine Comedy . Trans. Allen Mandelbaum. New York: Everyman’s Library, 1995.

Dowd, Maureen. “Liberties; His Brother’s Keeper.” The New York Times . 11 Apr. 1996. 5 Dec 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/1996/04/11/opinion/liberties-his-brother-s-keeper.html.

Fletcher, Gordon P. Loyalty: An Essay on the Morality of Relationships . New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Graham, Chris. “The Man Who Stopped the Unabomber.” Augusta Free Press . 22 Sept. 2005. 5 Dec. 2008. http://augustafreepress.com/2005/09/22/the-man-who-stopped-the-unabomber/.

Glaberson, William. “Heart of Unabom Trial is Tale of Two Brothers.” The New York Times . 5 Jan. 1998. 5 Dec. 2008. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9F01E6D71430F936A35752C0A96E958260.

Haidt, Jonathan, J. Graham. “When Morality Opposes Justice: Conservatives Have Moral Intuitions That Liberals May Not Recognize.” Social Justice Research 20 (2007): 98-116.

Natapoff, Alexandra. “Snitching: The Institutional and Communal Consequences.” University of Cincinnati Law Review 73 (2004): 645-703.

Nemerson, Steven S. “Coercive Sentencing.” Minnesota Law Review 64 (1980): 669-751.

Pinker, Steven. “The Moral Instinct.” The New York Times Magazine . 13 Jan. 2006. 5 Nov. 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/01/13/magazine/13Psychology-t.html.

Richman, Daniel C. “Cooperating Defendants.” Federal Sentencing Reporter 8.5 (1996): 292-295.

Shuster, Fred. “The Ties That Bind-Or Tough Love?: Readers Step Into Shoes of Man Who Thought His Brother May Be The Elusive Deadly Unabomber.” Los Angeles Daily News . 10 Apr. 1996. TheFreeLibrary. 5 Dec 2008. http://www.thefreelibrary.com/_/print/PrintArticle.aspx?id=83938147.

Weinstein, Ian. “Regulating the Market For Snitches.” Buffalo Law Review 47 (1999): 563-645.

Article Details

- The Nyaaya Guest Blog

- The Nyaaya Weekly

- About Nyaaya

- Our Collaborators

- Samvidhaan Fellowship

- Media Mentions

Feb 9, 2022

Sedition: The conundrum between disloyalty against the government and freedom of speech

Malavika Rajkumar and Kadambari Agarwal

“Sedition has been described as disloyalty in action, and the law considers as sedition all those practices which have for their object to excite discontent or dissatisfaction, to create public disturbance, or to lead to civil war; to bring into hatred or contempt the Sovereign or the Government, the laws or constitutions of the realm, and generally all endeavours to promote public disorder.” – Nazir Khan vs. State Of Delhi 2003 (8) SCC 461.

A relic of India’s colonial past — the law on sedition is defined in Section 124A of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC). From when it was introduced in 1870, the Courts and public alike have deliberated and debated upon the meaning of the word “sedition”, and the evolving jurisprudence has led to the understanding that the following constitutes sedition:

● Exciting Disaffection: Sedition is an attempt or an act to create feelings of hatred or contempt or disaffection (i.e. feelings of disloyalty or enmity) towards the legally appointed Government.

● Inciting Violence: Courts have held in Kedar Nath Singh v State of Bihar that a citizen has a right to criticize or comment against the Government, so long as he does not incite people to violence against the Government or create any public disorder.

● Word, Deed or Action: Sedition can be any act against the Government which may include those which are written, verbal or visual in nature.

If convicted for sedition, one may be charged with imprisonment up to 3 years and/or a fine, or imprisonment for life and/or a fine, or a fine. Before a case of sedition comes to Court, there has to be prior sanction to prosecute a person. This means that the government has to approve and sanction the chargesheet filed by the prosecution lawyers. Since there is only the requirement of sanction for trial, and no pre-arrest requirements for sedition, it leads to multiple arrests and misuse of power by the police. However, there is a large gap between the number of arrests made and the number of persons convicted. For example, as per the data reported by the National Crime Records Bureau in 2017, 228 persons were arrested while 4 persons were convicted on the grounds of sedition.

Seditious Literature

Given below are common scenarios discussed by Courts which may be considered as seditious:

Critiquing Government

Under the law on sedition, authorship, distribution or possession of seditious literature can amount to a convictable offence. In Raghubir Singh v. State of Bihar , it was held that one need not be the author of seditious literature; the mere distribution or circulation of seditious material is also sufficient for an arrest and subsequent conviction, depending on the facts of the case. However, in Romesh Thappar v. State of Madras , it was held that merely authoring one piece of mildly seditious literature does not amount to sedition. Further, in Dr. Vinayak Binayak Sen Pijush Piyush Babun Guha v. State of Chhattisgarh , it was held that possession of seditious literature can also be grounds for punishment under this law.

Slogans and Posters

The law on sedition under the IPC clarifies that comments that merely express disapproval of the measures of the government with the purpose of gaining its alteration through lawful means do not constitute sedition, and neither do comments that are expressing disapproval of administrative, or any other action of the Government. This view was upheld and validated by the judiciary in the case of Sanskar Marathe v. State of Maharashtra and Ors .

Involvement in a banned organization group

Raising slogans or the use of posters can be considered seditious only if there is an attempt/cause for hatred or contempt against the Government or if they lead to violence or public disorder. It was held in Balwant Singh and Anr v. State of Punjab that raising casual slogans which did not elicit any response from any community or person cannot be considered to be sedition.

Cartoons/Drawings

It was held in Arup Bhuyan v. State of Assam and Indra Das v. State of Assam that it is not an act of sedition if a person is merely a member of a banned organisation unless he causes/incites violence or creates public disorder by violence or incitement to violence. The same principle was upheld in Dr. Vinayak Binayak Sen Pijush v. State of Chhattisgarh case, but in this case, it was proved that the appellants had caused violence (such as, damaging police vehicles, attacking members of the armed forces, etc.) through the use of documents (nasality pamphlets, booklets, letters) to cause violence by damaging police vehicles, attacking and killing members of armed forces.

In the famous case of Sanskar Marathe v. State of Maharashtra and Ors . where the cartoonist Aseem Trivedi was booked for sedition, it was held that cartoons, caricatures, visual representations, signs, etc. can be witty, humorous, sarcastic or even express anger, but the right of speech and expression allows one to express one’s indignation towards the Government. As long as the cartoons, etc. do not incite violence or have the tendency to create any public disorder, it is not sedition.

The incidents given above are only an indicative list of acts that have or have not been considered as seditious in nature, but there is a chance that a person may be arrested or convicted under this law for other acts or incidents as well. Every case that appears before the Court, is tested against existing cases like Kedar Nath or Nazir Khan, but primary weightage is given to the facts of the case before the Court.

If you are arrested by the police for sedition, remember to contact a lawyer and request for bail. Many cases such as Sakal v. Union of India have discussed the right to freedom of speech and expression as an inherent right but since there are no pre-arrest requirements, there is a high chance of being arrested for sedition. Multiple lawyers have requested Courts to lay down guidelines or standards for arrest, like in the case of Common Cause v. Union of India requesting mandatory involvement of authorities like the Director General of Police or Magistrate to certify acts of sedition to prevent unwarranted arrests. Despite such requests, there has been no indication so far on any change in the way the colonial era law is going to be dealt with. Multiple discussions are taking place even today on whether this archaic law should be removed, but in the meanwhile, you should take all possible steps to stay safe in this politically charged environment where there is a very thin line between your freedom of speech and expression and the act of sedition.

Malavika Rajkumar is the Content Lead and Kadambari Agarwal is the Research Assistant at Nyaaya, an initiative of Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, New Delhi.

Originally published at https://www.moneycontrol.com .

Have a question you want to ask our legal experts?

Related guest blogs.

February 09 2022

Abuse of Sedition Law

February 14 2022

A Brief Overview of the Prevention of Corruption Act

February 15 2022

Farm Laws: What is Changing in the Agriculture Sector in India

How friendly is your city to lovers.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

8 Disloyalty

- Published: March 2007

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The significance of the norm against disloyalty (and the closely related concept of breach of trust) to our understanding of white-collar crime has been both over- and underestimated in the scholarly literature. On one hand, there are writers, such as Susan Shapiro, who have argued that violation of trust is the defining characteristic of white-collar crime. On the other hand, there are scholars such as John Coffee who have expressed considerable skepticism about the role that breach of trust should play in the criminal law. A more accurate assessment would arrive at a conclusion somewhere between these extremes. While the concept of disloyalty does play a significant role in defining certain key criminal offenses, such as bribery, treason, some acts of insider trading, and some frauds, it has little to do with many other core white collar offenses. This chapter explains the meaning of disloyalty, and foreshadows some of the ways that it plays a role in defining white-collar crime.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Corrections

McCarthyism & the Red Scare: The 2nd Communism Hysteria Phenomenon

McCarthyism appeared in the early 1950s when Senator McCarthy fueled the mass hysteria phenomenon of the second Red Scare that created fear and paranoia of communist infiltration.

In the midst of the Cold War, a US senator from Wisconsin took the meaning of anti-Communism to a new level when he accused federal government employees of being disloyal to the nation due to communist ties. The term McCarthyism is named after Senator McCarthy and is often used synonymously with the height of the second Red Scare. In the early 1950s, the American public was advised to be wary of communist influences lurking across the nation, and it caused mass hysteria. As the Soviet Union was spreading the Communist movement across Eastern and Central Europe and parts of Asia, communist expansion in the West became an increasing threat to the public and national security.

The Birth of McCarthyism

McCarthyism is a term used alongside the period of the second Red Scare that took place between 1947 and 1957. The term is associated with former United States Senator Joseph McCarthy from Wisconsin. McCarthyism refers to the public and falsely or loosely evidenced accusations that deemed federal government employees disloyal to the nation. One of the first uses of McCarthyism was in a Washington Post editorial released in March 1950. A cartoon created by Herbert Block entitled “ You Mean I’m Supposed to Stand on That? ” depicted Republican Senators Styles Bridges, Kenneth S. Wherry, and Robert A. Taft pushing and pulling on an elephant used as a Republican symbol toward a stack of tar buckets. On top of the buckets is a barrel labeled with the phrase McCarthyism holding up a small platform.

Joseph Raymond McCarthy was born in Grand Chute, Wisconsin on November 14, 1908. He attended school periodically but dedicated most of his time to farm labor to help support his family. He enrolled in high school at the age of 19 and completed all four years of coursework within one year. McCarthy enrolled at Marquette University in 1930 with the intention of studying engineering, but later switched to law and graduated in 1935. He went on to pass the Wisconsin bar exam and began a career in the legal field.

McCarthy entered the political arena when he was elected as a circuit judge in 1939. He served in the US Marine Corps during the Second World War and returned to his position following the end of the war. His career as a circuit judge ended when he was elected as a US Senator on behalf of the Republican Party in 1946. McCarthy didn’t stand out as a senator during his first few years. However, he quickly became a notable figure following a speech he gave in Wheeling, West Virginia to the Women’s Republican Club.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

On February 9, 1950, McCarthy gave a speech in Lincoln’s birthday address that warned of communist infiltration within the US government. He did so by stating:

“ While I cannot take the time to name all the men in the State Department who have been named as members of the Communist Party and members of a spy ring, I have here in my hand a list of 205 .”

McCarthy’s claims that he held a list of government officials associated with the Communist Party sparked a mass hysteria phenomenon that fueled the second Red Scare. The American public became extremely fearful of communist involvement, so much so that people lost their jobs and were blacklisted from entering certain organizations and federal government agencies.

The First Red Scare Phenomenon

The late 1940s Red Scare wasn’t the first time that mass paranoia of communism struck the nation. The first Red Scare appeared in 1919 when American socialists and radicals banded together to create the American Communist Party, which was largely influenced by the successful Russian Communist Party and Bolshevik Revolution . The Russian Communist Party created the Comintern , also referred to as the Communist International, to help push the Communist movement forward and establish influences in other parts of Europe. By 1922, two American Communist parties existed and had about 12,000 members.

Over the next decade, the American Communist Party expanded significantly to about 75,000 members. Communist influences within the US caused fear and hostility among the public, especially against immigrants. The first Red Scare led to thousands of individuals being accused of communist or anarchist relations.

The Palmer Raids was one of the most significant events of the first Red Scare, which was conducted by the US Department of Justice and led by J. Edgar Hoover. During the raids, between 3,000 and 10,000 individuals who were suspected of communist, socialist, or anarchist ties were detained. Many individuals who were detained were deported. The actions of the Palmer Raids were deemed constitutional since socialist, communist, and anarchist associations were thought to correlate with advocating for the overthrow of the US government.

Roots of the Second Red Scare

The unstable relationship between the United States and the Soviet Union became more apparent following World War II when political disagreements grew into competition over world power and influence. The heightened tensions between the two forces led to conflicts that threatened a third World War and the spread of Communism – a period known as the Cold War . Although the population of the US reached about 150 million in 1950 and only some 50,000 Americans were members of the Communist Party, the fear that Communism would take over the nation dominated the 1950s.

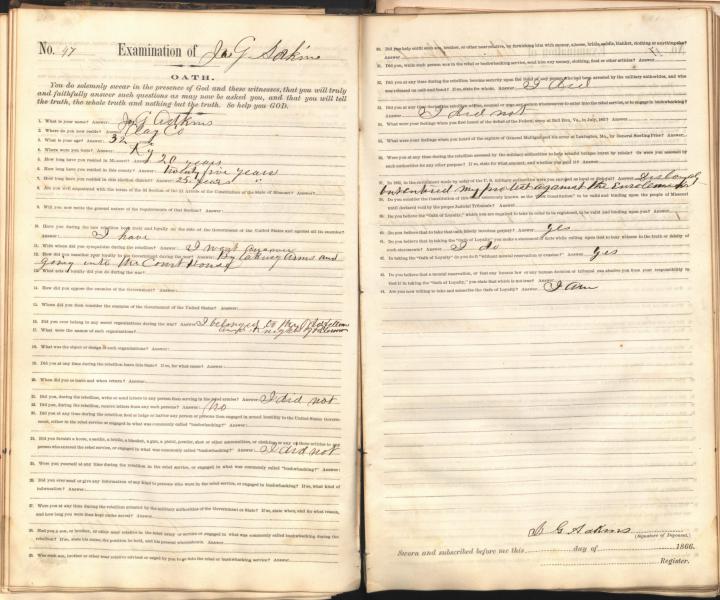

President Harry S. Truman reluctantly decided to launch the Federal Loyalty-Security Program through the signing of Executive Order 9835 to prevent communist infiltration within the US government. The program established loyalty boards, which were allowed to conduct investigations if there was any reasonable doubt that disloyalty existed. The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) was authorized to conduct investigations alongside the loyalty boards to help with the mass amount of inquiries they received on suspected individuals.

Loyalty boards were established in every federal agency and conducted reviews and hearings on federal employees. More than five million federal employees were investigated . Even being suspected of having communist relations or being a sympathizer was enough for people to lose their jobs. Thousands of employees resigned as a result, and several hundred were dismissed. Many of those who were accused had their political and social reputations damaged. Prior to the establishment of the Loyalty Order, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) was created in 1938 to investigate the disloyalty of individuals and organizations. The committee later became an important entity in the disloyalty inquiries and investigations that ensued throughout the 1950s.

The Grip of McCarthyism on the Second Red Scare

Senator McCarthy capitalized on the nation’s paranoia of Communism and used it to gain notoriety. As he stepped onto the scene of anti-Communism by claiming he knew of State Department employees who were involved in communist activities, it heightened the state of fear and paranoia. Many political leaders used it as a way to launch anti-Communism political campaigns to win elections in the early 1950s.

McCarthy took his efforts even further when he started a series of probes for communist infiltration within the State Department, Treasury, and the White House. He also launched an investigation for communist infiltration in the US Army. These probes were highly publicized, and his accusations were often knowingly false or lacked sufficient evidence to be pursued. However, politicians and federal officials avoided confronting McCarthy for his outlandish accusations, fearing that they would be accused of communist subversion and have their reputation damaged.

Influenced by McCarthy’s accusations of federal employee disloyalty, the Ohio General Assembly created the Ohio Un-American Activities Committee to investigate communist influences in the state. The committee was modeled after the HUAC and targeted state and federal government employees, government organizations, and even significant figures in Hollywood. Although many supported the actions the state and federal governments were taking to prevent the spread of Communism, some thought it violated free speech and privacy rights. Soviet spy rings and communists acting in favor of a foreign power did infiltrate federal government operations during World War II and the Cold War.

For example, the Rosenberg trial was a highly controversial case that resulted in the first Americans, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, being executed based on conspiracy to commit espionage during peacetime. The trial began in 1951, just as McCarthy began spewing accusations about government employee disloyalty. It was later determined that Julius was the leader of a Soviet spy ring and recruited and coordinated with other individuals to share secrets of the atomic bomb with the Soviets. Communist infiltration within the US government was present, and it did affect certain outcomes. Soviet spies who infiltrated US government operations were largely responsible for the Soviet Union’s ability to test its first atomic bomb in August 1949. The test came years earlier than what experts had projected for this type of Soviet weapons development.

The Downfall of McCarthyism

The Cold War didn’t end until 1991 along with the dissolution of the Soviet Union, but McCarthyism died out in the mid-1950s. The second Red Scare also dissolved along with McCarthyism. Senator Joseph McCarthy was largely responsible for his own downfall, which began when he launched a series of probes against the US Army for communist subversion as chairman of the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations in 1953. Although he managed to get away with accusing more than 200 federal employees of disloyalty, accusations against the US Army were a longshot.

The committee conducted a series of hearings, known as the Army-McCarthy hearings , which were broadcast on national television. While conducting the hearings, McCarthy was described as acting belligerent and inappropriately. His behavior made it more apparent that his accusations were false, causing him to lose what remaining trust the public had in him.

Adding onto his embarrassing behaviors, the US Army countered the accusations by alleging that McCarthy was abusing his power as he requested special treatment for one of his former employees. This made him a subject of the committee’s investigation and caused him to step down from his position as chairman. In December 1954, McCarthy was censured by the US Senate but kept his position until he died on May 2, 1957. Fear of Communism was still present among the American public following the period of McCarthyism. However, paranoia of communist infiltration and influence reached its highest point when Senator McCarthy launched his highly publicized, witch-hunt-like probes on federal employees between 1950 and 1954.

The Munich Agreement: The Actual Beginning of World War II

By Amy Hayes BA History w/ English minor Amy is a contributing writer with a passion for historical research and the written word. She holds a BA in history from Old Dominion University with a concentration in English. Amy grew up in the historic state of Virginia and quickly became fascinated by the intricate details of how people, places, and things came to be. She specializes in topics on American history, Ancient and Medieval England, law, and the environment.

Frequently Read Together

Gorbachev’s Moscow Spring & the Fall of Communism in Eastern Europe

The Rise of Vladimir Lenin: The Birth of the USSR

The Third International: What was COMINTERN?

About Search

Harry S Truman

Executive order 9835—prescribing procedures for the administration of an employees loyalty program in the executive branch of the government.

WHEREAS each employee of the Government of the United States is endowed with a measure of trusteeship over the democratic processes which are the heart and sinew of the United States; and

WHEREAS it is of vital importance that persons employed in the Federal service be of complete and unswerving loyalty to the United States; and

WHEREAS, although the loyalty of by far the overwhelming majority of all Government employees is beyond question, the presence within the Government service of any disloyal or subversive person constitutes a threat to our democratic processes; and

WHEREAS maximum protection must be afforded the United States against infiltration of disloyal persons into the ranks of its employees, and equal protection from unfounded accusations of disloyalty must be afforded the loyal employees of the Government:

NOW, Therefore, by virtue of the authority vested in me by the Constitution and statutes of the United States, including the Civil Service Act of 1883 (22 Stat. 403), as amended, and section 9A of the act approved August 2, 1939 (18 U.S.C. 61i), and as President and Chief Executive of the United States, it is hereby, in the interest of the internal management of the Government, ordered as follows:

PART I - INVESTIGATION OF APPLICANTS

- Investigations of persons entering the competitive service shall be conducted by the Civil Service Commission, except in such cases as are covered by a special agreement between the Commission and any given department or agency.

- Investigations of persons other than those entering the competitive service shall be conducted by the employing department or agency. Departments and agencies without investigative organizations shall utilize the investigative facilities of the Civil Service Commission.

- Investigations of persons entering the competitive service shall be conducted as expeditiously as possible; provided, however, that if any such investigation is not completed within 18 months from the date on which a person enters actual employment, the condition that his employment is subject to investigation shall expire, except in a case in which the Civil Service Commission has made an initial adjudication of disloyalty and the case continues to be active by reason of an appeal, and it shall then be the responsibility of the employing department or agency to conclude such investigation and make a final determination concerning the loyalty of such person.

- Federal Bureau of Investigation files.

- Civil Service Commission files.

- Military and naval intelligence files.

- The files of any other appropriate government investigative or intelligence agency.

- House Committee on un-American Activities files.

- Local law-enforcement files at the place of residence and employment of the applicant, including municipal, county, and State law-enforcement files.

- Schools and colleges attended by applicant.

- Former employers of applicant.

- References given by applicant.

- Any other appropriate source.

- Whenever derogatory information with respect to loyalty of an applicant is revealed a full investigation shall be conducted. A full field investigation shall also be conducted of those applicants, or of applicants for particular positions, as may be designated by the head of the employing department or agency, such designations to be based on the determination by any such head of the best interests of national security.

PART II - INVESTIGATION OF EMPLOYEES

- He shall be responsible for prescribing and supervising the loyalty determination procedures of his department or agency, in accordance with the provisions of this order, which shall be considered as providing minimum requirements.

- The head of a department or agency which does not have an investigative organization shall utilize the investigative facilities of the Civil Service Commission.

- An officer or employee who is charged with being disloyal shall have a right to an administrative hearing before a loyalty board in the employing department or agency. He may appear before such board personally, accompanied by counsel or representative of his own choosing, and present evidence on his own behalf, through witnesses or by affidavit.

- The officer or employee shall be served with a written notice of such hearing in sufficient time, and shall be informed therein of the nature of the charges against him in sufficient detail, so that he will be enabled to prepare his defense. The charges shall be stated as specifically and completely as, in the discretion of the employing department or agency, security considerations permit, and the officer or employee shall be informed in the notice (1) of his right to reply to such charges in writing within a specified reasonable period of time, (2) of his right to an administrative hearing on such charges before a loyalty board, and (3) of his right to appear before such board personally, to be accompanied by counsel or representative of his own choosing, and to present evidence on his behalf, through witness or by affidavit.

- A recommendation of removal by a loyalty board shall be subject to appeal by the officer or employee affected, prior to his removal, to the head of the employing department or agency or to such person or persons as may be designated by such head, under such regulations as may be prescribed by him, and the decision of the department or agency concerned shall be subject to appeal to the Civil Service Commission’s Loyalty Review Board, hereinafter provided for, for an advisory recommendation.

- The rights of hearing, notice thereof, and appeal therefrom shall be accorded to every officer or employee prior to his removal on grounds of disloyalty, irrespective of tenure, or of manner, method, or nature of appointment, but the head of the employing department or agency may suspend any officer or employee at any time pending a determination with respect to loyalty.

- The loyalty boards of the various departments and agencies shall furnish to the Loyalty Review Board, hereinafter provided for, such reports as may be requested concerning the operation of the loyalty program in any such department or agency.

PART III - RESPONSIBILITIES OF CIVIL SERVICE COMMISSION

- The Board shall have authority to review cases involving persons recommended for dismissal on grounds relating to loyalty by the loyalty board of any department or agency and to make advisory recommendations thereon to the head of the employing department or agency. Such cases may be referred to the Board either by the employing department or agency, or by the officer or employee concerned.

- The Board shall make rules and regulations, not inconsistent with the provisions of this order, deemed necessary to implement statutes and Executive orders relating to employee loyalty.

- Advise all departments and agencies on all problems relating to employee loyalty.

- Disseminate information pertinent to employee loyalty programs.

- Coordinate the employee loyalty policies and procedures of the several departments and agencies.

- Make reports and submit recommendations to the Civil Service Commission for transmission to the President from time to time as may be necessary to the maintenance of the employee loyalty program.

- All executive departments and agencies are directed to furnish to the Civil Service Commission all information appropriate for the establishment and maintenance of the central master index.

- The reports and other investigative material and information developed by the investigating department or agency shall be retained by such department or agency in each case.

- The Loyalty Review Board shall disseminate such information to all departments and agencies.

PART IV - SECURITY MEASURES IN INVESTIGATIONS

- At the request of the head of any department or agency of the executive branch an investigative agency shall make available to such head, personally, all investigative material and information collected by the investigative agency concerning any employee or prospective employee of the requesting department or agency, or shall make such material and information available to any officer or officers designated by such head and approved by the investigative agency.

- Notwithstanding the foregoing requirement, however, the investigative agency may refuse to disclose the names of confidential informants, provided it furnishes sufficient information about such informants on the basis of which the requesting department or agency can make an adequate evaluation of the information furnished by them, and provided it advises the requesting department or agency in writing that it is essential to the protection of the informants or to the investigation of other cases that the identity of the informants not be revealed. Investigative agencies shall not use this discretion to decline to reveal sources of information where such action is not essential.

- Each department and agency of the executive branch should develop and maintain, for the collection and analysis of information relating to the loyalty of its employees and prospective employees, a staff specially trained in security techniques, and an effective security control system for protecting such information generally and for protecting confidential sources of such information particularly.

PART V - STANDARDS

- The standard for the refusal of employment or the removal from employment in an executive department or agency on grounds relating to loyalty shall be that, on all the evidence, reasonable grounds exist for belief that the person involved is disloyal to the Government of the United States.

- Sabotage, espionage, or attempts or preparations therefor, or knowingly associating with spies or saboteurs;

- Treason or sedition or advocacy thereof;

- Advocacy of revolution or force or violence to alter the constitutional form of government of the United States;

- Intentional, unauthorized disclosure to any person, under circumstances which may indicate disloyalty to the United States, of documents or information of a confidential or non-public character obtained by the person making the disclosure as a result of his employment by the Government of the United States;

- Performing or attempting to perform his duties, or otherwise acting, so as to serve the interests of another government in preference to the interests of the United States.

- Membership in, affiliation with or sympathetic association with any foreign or domestic organization, association, movement, group or combination of persons, designated by the Attorney General as totalitarian, fascist, communist, or subversive, or as having adopted a policy of advocating or approving the commission of acts of force or violence to deny other persons their rights under the Constitution of the United States, or as seeking to alter the form of government of the United States by unconstitutional means.

PART VI - MISCELLANEOUS

- The Federal Bureau of Investigation shall check such names against its records of persons concerning whom there is substantial evidence of being within the purview of paragraph 2 of Part V hereof, and shall notify each department and agency of such information.

- Upon receipt of the above-mentioned information from the Federal Bureau of Investigation, each department and agency shall make, or cause to be made by the Civil Service Commission, such investigation of those employees as the head of the department or agency shall deem advisable.

- The Security Advisory Board of the State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee shall draft rules applicable to the handling and transmission of confidential documents and other documents and information which should not be publicly disclosed, and upon approval by the President such rules shall constitute the minimum standards for the handling and transmission of such documents and information, and shall be applicable to all departments and agencies of the executive branch.

- The provisions of this order shall not be applicable to persons summarily removed under the provisions of section 3 of the act of December 17, 1942, 56 Stat. 1053, of the act of July 5, 1946, 60 Stat. 453, or of any other statute conferring the power of summary removal.

- The Secretary of War and the Secretary of the Navy, and the Secretary of the Treasury with respect to the Coast Guard, are hereby directed to continue to enforce and maintain the highest standards of loyalty within the armed services, pursuant to the applicable statutes, the Articles of War, and the Articles for the Government of the Navy.

- This order shall be effective immediately, but compliance with such of its provisions as require the expenditure of funds shall be deferred pending the appropriation of such funds.

- Executive Order No. 9300 of February 5, 1943, is hereby revoked.

Harry S. Truman The White House, March 21, 1947

Harry S Truman, Executive Order 9835—Prescribing Procedures for the Administration of an Employees Loyalty Program in the Executive Branch of the Government Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/node/275962

Filed Under

Simple search of our archives, report a typo.

Loyalty to the Monarchy in Late Medieval and Early Modern Britain, c.1400-1688 pp 231–252 Cite as

Loyalty, Disloyalty, and the Coronation of Charles II

- Edward Legon 3

- First Online: 01 July 2020

295 Accesses

The coronation of Charles II in 1661 was a remarkable spectacle and, as historians have shown, elicited an extraordinary outpouring of loyalty to the new king across the Stuart realms. Not everyone shared this enthusiasm, however. This chapter offers an overview of evidence of hostility to the celebrations and seeks to identify the origins of such sentiment. While, in many cases, dissent connotes the ‘disloyalty’ which was ascribed to it by the new regime, this was clearly not always an accurate interpretation. To be sure, as the reign of Charles II unfolded, there was increasing potential for expressions of alienation from the political and religious settlements to be construed as sedition.

I am very grateful to the following for their advice and support: Ian Atherton, Richard Bell, Alden Gregory, Catherine Hinchliff, Wendy Hitchmough, Jason Peacey, Elaine Tierney, and Sarah Ward. I am particularly grateful to Jack Sargeant, who commented on a draft of this work, and to the anonymous reviewer.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition