Conserving Biological Diversity

- Download Full Paper

Subscribe to Global Connection

William y. brown wyb william y. brown former brookings expert.

August 9, 2011

- 16 min read

INTRODUCTION Life first appeared on Earth about 3.8 billion years ago and over time covered the land and sea with microbes, plants and animals. The count of known species now stands at about 1.8 million, and no one would be surprised if over 10 times more exist, still undiscovered. Most humans come from a small group that slipped out of Africa less than 100,000 years ago and spread around the globe, less than one-tenth of a second on a time-scale measured at 1 hour since life first appeared. Despite mankind’s very recent presence, we have eliminated species and pushed many more out of the places they lived. This began with mammoths and other prehistoric animals, but the pace of extinction and displacement has accelerated since permanent settlements were established and machines were invented to improve our lives. E.O. Wilson has estimated that 3 species are lost per hour. Exact numbers are elusive—starting with not knowing how many species there really are to begin with—but the big picture of loss is unmistakable.

CONVENTION ON BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Many national governments have recognized the value of nature and taken steps to conserve it through protected areas and laws that regulate exploitation. A range of international agreements have also been adopted. The most comprehensive in scope of these is the Convention on Biological Diversity (“CBD”), which entered into force on 29 December 1993, and now has 193 parties. The CBD’s preamble notes “the intrinsic value of biological diversity and of the ecological, genetic, social, economic, scientific, educational, cultural, recreational and aesthetic values of biological diversity and its components.” It notes “the importance of biological diversity for evolution and for maintaining life sustaining systems of the biosphere.” And it affirms “that that the conservation of biological diversity is a common concern of humankind.”

The CBD’s effectiveness has been questioned, but representatives stepped forward at the most recent meeting of the Conference of the Parties (COP 10) in Nagoya, Japan, held in October 2010. The parties acknowledged failure to significantly reduce loss of global biodiversity between 2002 and 2010, as the first strategic plan of the CBD prescribed, and they adopted a new strategic plan for 2011–2020 (“Plan”).

The Plan’s vision is “ a world of ‘Living in harmony with nature’ where ‘by 2050, biodiversity is valued, conserved, restored and wisely used, maintaining ecosystem services, sustaining a healthy planet and delivering benefits essential for all people. ’ ” The Plan’s mission is to “take effective and urgent action to halt the loss of biodiversity in order to ensure that by 2020 ecosystems are resilient and continue to provide essential services …” The Plan has 20 “Aichi Targets,” named after the Prefecture whose capital is Nagoya, many with references to accomplishments by 2020. Target 11, for example, states: “By 2020, at least 17 per cent of terrestrial and inland water areas, and 10 per cent of coastal and marine areas, especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and ecosystem services, are conserved …” However, the Plan offers no specific measures to determine whether an area has been “conserved” or not, nor does it commit parties to achieving the targets. The sentiment for action in the Plan is good, but could any informed observer believe the timelines: that global loss of biodiversity will be halted in 9 years, or that mankind collectively will be “living in harmony with nature” 39 years from now?

One important, concrete, and realistic step forward would be to give the people who manage areas of land and water better guidance on how to conserve biological diversity on their properties. More than guidance is needed, of course. Developing nations, where degradation of the natural world is most rapid, are faced with stark, short-term economic choices on resource use, high population growth, and limited educational and governance capability. These realities are fundamental obstacles to conservation that only economic and social advancement can remove, combined with finding nearer-term opportunities for people to conserve biodiversity and make a living at the same time. Yet these obstacles call out for guidance too, because the difficulty of taking actions needed for conservation will depend on what kinds of actions conservation requires.

Land and water managers need an owner’s manual for conservation. Many, whether government, business, or personal owners, have limited background in science, law, or policy and also have responsibilities other than conservation—like making a profit. Unless they know just what to do for conservation, it won’t be done, and yet it is primarily their actions that will determine the future of Earth’s biological diversity. But what does “biological diversity” actually mean?

The term “biological diversity” first appeared in 1968 in a book by Raymond F. Dasmann, A Different Kind of Country , in reference to the richness of living nature that conservationists should protect. It resurfaced in the 1980’s in books, articles and conferences on conservation, and was presented as an alternative to “wildlife management,” whose concepts and practices were seen as over-emphasizing species of fish and other animals that are caught or shot, and as giving too little attention to plants and invertebrate animals and to multi-species ecology. The term biological diversity is defined in the CBD to mean:

“the variability among living organisms from all sources including, inter alia, terrestrial, marine and other aquatic ecosystems and the ecological complexes of which they are part; this includes diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems.”

The key word in this definition is “variability,” which all the other words qualify. The basic concept of this definition was first articulated for “species diversity” and defined through information theory. Its variables are the number of species and the relative abundance of the different species. Species diversity is higher in an area if more species are present. It is also higher if the species present have similar relative abundances, rather than one or a few species dominating in numbers while the others are rare. The CBD definition also includes variability within species and variability of ecosystems. Intraspecific variability is a recognized plus in conservation—for example, the in-breeding and very limited genetic variation in cheetahs is harmful to their conservation. It is also beneficial to have more kinds of ecosystems, such as bogs, mountain meadows, coastal dunes, coral reefs. Overall, we benefit from having more species, more ecosystems types, more genetic variation within species, and a more distributed representation of all these things rather than having them clumped in a few places.

But variability isn’t everything. In misguided efforts to increase species diversity, the CBD definition of biological diversity could be read to promote the introduction of non-native species into an area (although the CBD has separate language inveighing against invasives). The definition could be read to give lower priority to high-latitude ecosystems that have fewer species than the tropics, even though high-latitudes might have species of great ecological and economic significance, such as krill in the Southern Ocean. Not much debate has emerged, however, along these lines because biological diversity has been treated more as a general reference to wild living nature than as something that can be reduced to a formula. Nonetheless, the first objective of the CBD is conservation of biological diversity, and objectives require measures of success. So what might those conservation measures be?

Academic disciplines, like such as conservation biology and landscape ecology, have emerged to address this issue in combination with long-standing research for industries such as fisheries and forestry. The former look mostly at determining what features are best for the ecology of places and the latter typically address what extraction is sustainable. A wealth of information is available on both fronts. Much less has been done to effectively translate work on ecological priorities and sustainability of extraction into practical, relatively simple, guidelines that land and water managers need to conserve their property’s biological diversity. “Best practices” have been developed for many industries, such as principles and criteria of the Forest Stewardship Council and an array of best practices for different fisheries put out by the Food and Agriculture Organization. These are tailored to the uses and places for which they were developed and can be an important component of conservation planning. However, best practices describe a process with do’s and don’ts rather than a measurable vision of what features of biological diversity in a managed area should look like if they are to be considered conserved. A vision is needed. Two different models warrant consideration. One references the “original” features of an area before any disturbance by man, and the other references the features exhibited when the area is used for sustainable provision of goods and services for people. Together, the original condition and sustainable uses can provide the vision and framework needed.

Biological diversity has been diminished at the hand of humankind through habitat fragmentation and reduction, direct over-exploitation, pollution and introduced invasive species. A location’s original condition before this happened is a reference point. Unless an area is undisturbed now, that originial condition must be estimated by using historical information or by reference to related but less disturbed areas believed to have similar, original features. Once the original features are characterized for an area, it can be resurveyed periodically and progress in conserving biological diversity measured as change in the similarity between the original features and the current features.

The original condition isn’t biased by interest in extraction, and it is the condition that usually reflects a long course of evolution and complex ecological relationship tested through time with only the very recent involvement of the human species. The original condition also often has the high variability in species and ecosystems that the CBD defines as biological diversity. An exceptional adjustment to this management of the original condition may be warranted for climate change, because it is on-going and cannot be locally reversed. For example, if a wetland will be permanently submerged through sea level rise and a now dry higher elevation area will become wetland, then this should be accounted for in managing a property overall to approximate its “original” condition.

But conserving biological diversity also must embrace sustainable provision of goods and services for people. Use of biological diversity is an objective of the CBD and many other legal regimes, just as is conservation, and if use were prohibited it would still continue to happen and conservation would suffer from the policy. Biological diversity has provided valuable goods and service for people throughout human existence. These “ecosystem services” are now prominent in many policies and programs for development, and failure to embrace sustainable use of these resources for current human livelihoods would not only diminish standards of living but would undermine political support for long-term resource conservation.

Not every place should be modified by human use. We should strive to keep wild a significant share of those diminishing, genuinely pristine areas of biological diversity on Earth, and the growing number of wilderness parks and sanctuaries on land and sea are contributing to that. But most areas are significantly modified, and can be managed in a way that moves them towards their original condition and also allows resource use. Core objectives in this case include sustainable harvest of target species, such as trees and fish, protection of endangered or threatened species, maintaining balanced amounts of old-growth forest or big fish, preserving unfragmented habitat and corridors for movement, and preventing or managing pollution. The kinds of uses make a difference. Very strict scrutiny and constraints are needed for commercial harvest of trees or fish and any conversion of natural lands for agriculture or settlements, whereas traditional indigenous uses may be intrinsically beneficial to conservation by bringing watchful eyes into an ecosystem.

Policy Recommendations With the discussion above in mind, the following principles are offered for managers with responsibility for conserving the biological diversity of geographic areas of land or water:

Develop a comprehensive plan for conserving the biological diversity of the area. The plan should include goals, objectives, implementing actions, and measures. It should include a system for assuring compliance with plan requirements, and should provide for regular internal and external reviews of compliance and, less frequently, of the plan itself.

Make implementing the conservation plan a significant element in performance reviews of employees whose work affects conservation. This will vary with position. A government director of a national forest might be appraised with respect to the forest as a whole, including monitoring and enforcement of applicable laws. The work of a company manager logging in that forest might be reviewed by his corporate supervisors for implementation and compliance with conservation requirements developed and endorsed by the government director. A logger working in that forest might be reviewed by the company manager for compliance with specific instructions, incorporating conservation, on what and how to cut. People care about keeping jobs and earning as much as they can.

Make sure available information demonstrates that actions will be consistent with conservation objectives before the actions are taken. The burden of proof in natural resource use has often determined whether conservation or over-exploitation occurs. Fishery regulation has been based historically on quotas that regulators are required to develop and substantiate. Number are proposed by them, fishing interests express opposition, and, after the dust of debate settles, over-exploitation happens. Yet the fishing in some geographically designated areas, such as national wildlife refuges in the United States, is presumed closed unless users or managers can demonstrate that the catch will be compatible with conservation, and the fishing allowed in these refuges typically does not deplete the populations that are fished. Existing laws for a given area may not shift burden of proof to users, but private land-owners can voluntarily accept that shift, and laws can be changed.

Don’t mix guidance for conservation with guidance promoting use or benefit-sharing. The objectives of the CBD are, “. . . the conservation of biological diversity, the sustainable use of its components and the fair and equitable sharing of the benefits arising out of the utilization of genetic resources . . .” The CBD parties will continue to pursue all three objectives, but they should not be intertwined with guidance for conservation, which is by itself difficult to define and achieve. If all three objectives are mixed into a single measure, the likely consequence will be confusion on what is needed for conservation.

In respect to any funding for Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD), make conservation of biological diversity a condition for funding, but do not use it to determine the amount of funding. The Cancun Agreements adopted at the 16th Conference of the Parties to the Framework Convention on Climate Change (FCCC) endorsed and expanded the policy of Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD). This included recognizing the role of conservation and sustainable forest management and the “co-benefit” of biodiversity. The Cancun Agreements also set out details for the Green Climate Fund and, in principle, will be the financial mechanism through which developed nations will contribute to developing nations for climate actions on mitigation and adaptation, including those concerning forests. The FCCC parties have agreed to a goal of mobilizing $100 billion per year for this purpose by 2020, and hope that significant additional funding will be available to conserve forests and their biodiversity. However, the primary purpose of REDD is to reduce carbon emissions, and the mainstream discussion on funding levels and offset credits that may be earned through forest investment is tied to the level of reduction in carbon emissions. Furthermore, carbon is an atomic element that can be measured without the problem of subjectivity in definition that is inherent in measuring biological diversity. In the interest of clarity and effective process, conservation of biological diversity should be a condition for REDD funding, but the funding amount is better determined by the amount of greenhouse gas mitigation.

Map features defining the area’s current and original biological diversity. The current features can be determined with a survey. The original features—those present before human disturbance—cannot be exactly determined if the area has been disturbed, but may be estimated using historical information for the area or through reference to other pristine or less disturbed areas believed to have similar, original features. The features mapped should at a minimum include: (a) kind, abundance, and distribution of indicator species and ecosystem types; (b) age structure of harvested species such as trees or fish, (c) endangered or threatened species if present, (d) invasive species; (e) habitat coverage showing any fragmentation; (f) corridors that impede or facilitate movement or spread; (g) sources and levels of any harmful pollutants. The original features might require adjustment in setting management objectives to address future climate change. The data assembled for mapping should be geospatially referenced and entered into a GIS application that can both prepare visual maps of variables and support diverse analyses of the data. Contractors should be engaged if in-house expertise is not adequate. The intensity of detail and choice of methods for surveys will vary with scale, from satellite or aerial imaging combined with ground-truthing for large areas, to ground-based work alone for small areas. The specifics will also vary with the area’s use. For example: An area managed as wilderness would look closely for effects of invasive species, climate change and illegal activities; A logged forest or fishing ground would include detailed information related to harvest. Initial surveys will typically be more detailed than subsequent surveys to monitor change.

Periodically re-map the area and estimate the similarity between current and original features to assess progress in conserving biological diversity. Progress in conservation by this measure will show an increase in similarity over time. A policy of “no-net-loss” would require that the similarity not decrease. Various statistical tools can be used for this now, but finding agreed models and, especially, user-friendly applications for this task should be a priority for funding agencies, institutions and experts concerned with conserving biological diversity. This is a situation where concepts abound and where focus and simplification is needed. The programs offered might be subtle and internally complex, but they should be easy for managers to use and read, and they should have as much endorsement as possible by authorities, including the CBD.

Manage the area to approximate the original features mapped, implement best practices that make sense, and don’t allow unsustainable uses. The map of original features is essentially a blueprint for the area’s modification and management. The specific actions will vary widely between areas, but are techniques and practices for these are well-developed and familiar to a range of experts. Existing and proposed uses with the potential to significantly impede achievement of original features should be closely reviewed, such as logging and fishing, and allowed only if they are determined to be consistent with conservation of biological diversity. These uses should be sustainable for the species and ecosystems impacted, not detrimental to the survival of any associated endangered or threatened species, and consistent with other values such as maintaining some fully protected areas, keeping a share of old-growth forest or big fish, avoiding habitat fragmentation and loss of corridors, and preventing harmful pollution. This review will necessarily require some subjectivity and subtlety and independent technical expertise should be engaged and respected.

Conserving biological diversity is a stated priority not just in the CBD but in the domestic laws of most nations and in the priorities of international, regional, and national development agencies. Furthermore, many conservation projects have been undertaken in connection with economic development initiatives such as roads, dams, and agricultural expansion, sometimes required by development agencies as conditions for loans or grants. But the actual contributions of these projects to conserving biological diversity, and to mitigating environmental impacts associated with construction and land-use change, will be uncertain unless measures such as the principles above are woven into projects by the agencies that oversee and fund them. Having measures doesn’t guarantee success, but lack of measures begs for failure. The principles offered above for conserving biological diversity can certainly be refined, augmented and improved. But if followed, they offer a prescription for the task ahead. We need that.

Global Economy and Development

Daniel S. Hamilton, Joseph P. Quinlan

March 18, 2024

Kevin Dong, Mallie Prytherch, Lily McElwee, Patricia M. Kim, Jude Blanchette, Ryan Hass

March 15, 2024

Tarek Ghani, Juan S. Lozano, Anouk Rigterink, Jacob N. Shapiro

March 13, 2024

- UNESCO's commitment

- Culture and values

- Conservation and sustainable use

- Local, indigenous and scientific knowledge

- Education and awareness

- Ocean Sciences

- UNESCO Biodiversity Portal

- International governance mechanisms

- United Nations Decade on Ecosystem Restoration

- United Nations Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development

- Ocean Biodiversity Information System

Conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity

Biodiversity is currently being lost at up to 1,000 times the natural rate. Some scientists are now referring to the crisis as the ‘Earth’s sixth mass extinction’, comparable to the last great extinction crisis 65 million years ago. These extinctions are irreversible and pose a serious threat to our health and wellbeing. Designation and management of protected areas is the cornerstone of biodiversity conservation. However, despite an increase in the total number of protected areas in the world, biodiversity continues to decline.

An integrated landscape approach to conservation planning plays a key role in ensuring suitable habitats for species. However, many protected areas are not functioning as effectively as originally intended, due in part to limited resources to maintain these areas and/or enforce relevant legal frameworks. In addition, current protected area networks may need to be re-aligned to account for climate change. Efforts to preserve biodiversity must take into account not only the physical environment, but also social and economic systems that are well connected to biodiversity and ecosystem services. For protected areas to contribute effectively to a secure future for biodiversity, there is a need for measures to enhance the representativeness of networks, and to improve management effectiveness.

- Growth in protected areas in many countries is helping to maintain options for the future, but sustainable use and management of territory outside protected areas remains a priority.

- Measures to improve environmental status within conservation areas, combined with landscape-scale approaches, are urgently needed if their efficiency is to be improved.

- Lack of adequate technical and financial resources and capacity can limit the upscaling of innovative solutions, demonstrating further the need for regional and subregional co-operation.

- Capacity building is a key factor in the successful avoidance and reduction of land degradation and informed restoration.

- Capacity development needs should be addressed at three levels: national, provincial and local.

- There is a need for capacity building to enable sources outside government to inform relevant departments and policies on biodiversity (e.g. through consultancies, academia and think tanks).

Sites, connected landscapes and networks

Conserving biodiversity and promoting sustainable use.

UNESCO works on the conservation of biodiversity and the sustainable use of its components through UNESCO designated sites, including biosphere reserves , World Heritage sites and UNESCO Global Geoparks . In 2018, UNESCO designated sites protected over 10 million km 2 , an area equivalent to the size of China. These conservation instruments have adopted policies and strategies that aim to conserve these sites, while supporting the broader objectives of sustainable development. One such example is the policy on the integration of a sustainable development perspective into the processes of the World Heritage Convention.

UNESCO is also the depository of the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance . Countless species of plants and animals depend on these delicate habitats for survival.

The first comprehensive assessment of species that live within World Heritage sites reveals just how critical they are to preserving the diversity of life on Earth.

The MAB Programme and the World Network of Biosphere Reserves: connecting landscapes and reconciling conservation with development

Biosphere reserves are designated under UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere (MAB) Programme and promote solutions reconciling the conservation of biodiversity with its sustainable use at local and regional scales.

This dynamic and interactive network of sites works to foster the harmonious integration of people and nature for sustainable development through participatory dialogue, knowledge sharing, poverty reduction, human wellbeing improvements, respect or cultural values and efforts to improve society’s ability to cope with climate change. Progress has been achieved in connecting landscapes and protected areas through biosphere reserves, however further efforts are needed.

- World Network of Biosphere Reserves (WNBR)

- BIOsphere and Heritage of Lake Chad (BIOPALT)

- Women for Bees - a joint Guerlain and UNESCO programme

- Protecting Great Apes and their habitats

- Ecosystem restoration for sustainable development in Haiti ( Français | Español )

- Green Economy in Biosphere Reserves project in Ghana, Nigeria and Tanzania *

- More activities and projects

and the sustainable use of its components through UNESCO designated sites

Capacity building

Capacity building is needed to provide adequate support to Member States to attain the international biodiversity goals and the SDGs. In some countries, technical, managerial and institutional capacity to define guidelines for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity is inadequate. Additionally, existing institutional and technical capacity is often fragmented and uncoordinated. As new ways of interacting with biodiversity emerge, it is essential that stakeholders are trained and have sufficient capacity to implement new and varied approaches. Further efforts will be needed therefore to facilitate capacity building by fostering learning and leadership skills.

UNESCO is mandated to assist Member States in the design and implementation of national policies on education, culture, science, technology and innovation including biodiversity.

The BIOPALT project: integrated management of ecosystems

More than 30 million people live in the Lake Chad Basin. The site is highly significant in terms of biodiversity and natural and cultural heritage. The cross-border dimension of the basin also presents opportunities for sub-regional integration. The BIOsphere and Heritage of Lake Chad (BIOPALT) project focuses on poverty reduction and peace promotion, and aims to strengthen the capacities of the Lake Chad Basin Commission member states to safeguard and manage sustainably the water resources, socio-ecosystems and cultural resources of the region.

Women for bees: Women’s empowerment and biodiversity conservation

Women for Bees is a state-of-the-art female beekeeping entrepreneurship programme launched by UNESCO and Guerlain. Implemented in UNESCO designated biosphere reserves around the world with the support of the French training centre, the Observatoire Français d’Apidologie (OFA), the programme has actor, film maker and humanitarian activist Angelina Jolie for a Godmother, helping promote its twin objectives of women’s empowerment and biodiversity conservation.

Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) and capacity development

Capacity development is present in all areas of IOC ’s work, at the global programme level as well as within each of its three sub-commissions and the IOC-INDIO regional committee. In 2015, IOC adopted its Capacity Development Strategy. IOC is the custodian agency for SDG 14A.

In collaboration with the International Oceanographic Data and Information Exchange (IODE) , IOC has implemented a network of Regional Training Centres under the OceanTeacher Global Academy (OTGA) project, which has seven such centres around the world (Belgium, Colombia, India, Kenya, Malaysia, Mozambique and Senegal). Through its network of centres, OTGA provides a programme of training courses related to IOC programmes, which contribute to the sustainable management of oceans and coastal areas worldwide. OTGA has developed an e-Learning Platform that hosts all training resources for the training courses and makes them freely available to any interested parties.

Since 2012, 270 scientists from 69 countries have been trained to manage marine biodiversity data, publish data through the Ocean Biogeographic Information System (OBIS) , and perform scientific data analysis for reporting and assessment. Since 1990, IOC West Pacific Regional Training and Research Centres have trained more than 1,000 people in a variety of topics including:

- monitoring the ecological impacts of ocean acidification on coral reef ecosystems,

- harmful algal blooms,

- traditional and molecular taxonomy,

- reef health monitoring, and

- seagrass and mangrove ecology and management.

Most courses take place in a face-to-face classroom environment, however training can also be conducted online using ICTs and the OceanTeacher e-Learning Platform, thereby increasing the number of people reached.

and peace-building through the promotion of green economy and the valorization of the basin's natural resources

Governance and connecting the scales

Governance systems in many countries function as indirect drivers of changes to ecosystems and biodiversity. At present, most policies that address biodiversity are fragmented and target specific. Additionally, the current design of governance, institutions and policies rarely takes into account the diverse values of biodiversity. There are also substantial challenges to the design and implementation of effective transboundary and regional initiatives to halt biodiversity loss, ecosystem degradation, climate change and unsustainable development. Another key challenge to successful policy-making is adequate mobilization of financial resources. Increased funding from both public and private sources, together with innovative financing mechanisms such as ecological fiscal transfers, would help to strengthen institutional capacities.

- Governance options that harness synergies are the best option for achieving the SDGs.

- There is a need to develop engagement and actions with diverse stakeholders in governance through regional cooperation and partnerships with the private sector.

- Mainstreaming biodiversity into development policies, plans and programmes can improve efforts to achieve both the Aichi Targets and the SDGs.

UNESCO works to engage with new governance schemes at all levels through the LINKS Programme , the MAB Programme , the UNESCO-CBD Joint Programme and integrated management of ecosystems linking local to regional scales.

UNESCO supports the integrated management of ecosystems linking local to regional scales, especially through transboundary biosphere reserves, World Heritage sites and UNESCO Global Geoparks. The governance and management of a biosphere reserve places special emphasis on the crucial role that combined knowledge, learning and capacity building play in creating and sustaining a dynamic and mutually beneficial interactions between the conservation and development objectives at local and regional scales.

A transboundary biosphere reserve is defined by the following elements: a shared ecosystem; a common culture and shared traditions, exchanges and cooperation at local level; the will to manage jointly the territory along the bio-sphere reserve values and principles; a political commitment resulting in an official agreement between governmental authorities of the countries concerned. The transboundary biosphere reserve establishes a coordinating structure representative of various administrations and scientific boards, the authorities in charge of the different areas included the protected areas, the representatives of local communities, private sector, and NGOs. A permanent secretariat and a budget are devoted to its functioning. Focal points for co-operation are designated in each country participating.

Transboundary conservation and cooperation

The Trifinio Fraternidad Transboundary Biosphere Reserve is located between El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras. It is the first transboundary biosphere reserve in Central America and represents a major contribution to the implementation of the Mesoamerican Corridor. It includes key biodiversity areas, such as Montecristo National Park and a variety of forest ecosystems.

Trifinio Fraternidad Transboundary Biosphere Reserve (El Salvador/Guatemala/Honduras)

Related items

- Information and communication

- Social and human sciences

- Natural sciences

- Programme implementation

- See more add

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.50(5); 2021 May

How to conserve biological diversity: Perspectives from Ambio

Jeffrey a. mcneely.

Society for Conservation Biology Asia Section, Petchburi, Thailand

Biological diversity (biodiversity for short) provides a powerful example of how a new term can generate substantial international action. The utility of treating genes, species, and ecosystems together emerged in the mid-1980s, highlighted by an international convergence of university researchers, economists, foresters, agroecologists, ethicists, and government resource managers brought together by the visionary Edward O. Wilson (Wilson 1988 ), perhaps inspired by his earlier work on sociobiology (Wilson 1975 ). This broad constituency addressed both the threats to biodiversity and the social, scientific, and economic benefits of its conservation. The next step was a series of discussions organized by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) among governments and non-governmental conservation organizations about how to promote more effective international cooperation to address the problem of biodiversity loss. The climax of this effort was agreement on a Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD 1992 ) at the Rio de Janeiro Earth Summit on 5 June, entered into force on 29 December 1993 (Sayer et al. 2021 ), and has now been ratified by all but one of the UN member countries (ironically, the only non-party is the USA, which played an active role in its negotiation and is deeply affected by its provisions).

One of the innovations of the CBD was the attention given to traditional ecological knowledge (article 8j), a topic that has been well addressed in Ambio . Shortly after the CBD was agreed, Gadgil et al. ( 1993 ) provided detailed examples of the resource management practices of people who have long depended on their local ecosystems for their survival and cultural identity, often supported by their belief systems that give spiritual values to key resource systems such as watershed protection forests. The principles of indigenous rights to resources and the value of traditional knowledge are now in the mainstream of biodiversity conservation, and community-based resource management systems are enhancing the land rights of indigenous peoples in many parts of the world (Doyle 2015 ; Gilbert 2016 ). Gadgil et al. ( 2021 ) have brought this concept up to date, showing that traditional knowledge is still relevant to the modern challenges to conserving biodiversity.

The CBD’s Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011–2020 was highly relevant to protected areas as a major conservation tool (Pimm 2021 ; Sayer et al. 2021 ). Its target 11 called for establishing at least 17% of terrestrial and inland water biomes as protected areas, along with 10% of coastal and marine biomes. These were to be effectively and equitably managed, ecologically representative, and well connected as parts of systems of effective area-based conservation measures that are integrated into wider landscapes and seascapes.

Ambio has provided useful perspectives on how these protected area design issues could be addressed more effectively. Bengtsson et al. ( 2003 ) highlighted some of the limitations of protected areas, which covered just over 11% of the land at that time. Protected areas were considered too static when they need to be more dynamic. A dynamic landscape approach that mimics natural disturbance regimes could include, for example, successional lands that are recovering from over-exploitation; these resemble the territories managed by indigenous peoples such as the shifting cultivation practices described by Gadgil et al. ( 1993 ). Almost a decade later, Hanski ( 2011 ) presented detailed evidence that species can suffer from fragmented landscapes and protected areas are often too small to support viable populations, underlining the CBD target 11 point that connectivity of habitats is essential (also see Bengtsson et al. 2003 ). The importance of landscape connectivity is now in the conservation mainstream, with detailed guidelines prepared by an IUCN international team (Hilty et al. 2020 ).

The protected area design concepts of Hanski ( 2011 ) and Bengtsson et al. ( 2003 ) are now being addressed by governments under the CBD (Maxwell et al. 2020 ). They have adopted the concept of other effective area-based conservation measures (OECM), which are geographically defined areas other than protected areas that are governed and managed in ways that conserve biodiversity and ecosystem services and provide cultural, spiritual, and socio-economic benefits (SCBD 2018 ). They could include many landscapes owned or managed by indigenous peoples.

Today’s environmental, social, economic, and political conditions require innovative responses that are appropriate to the emerging conditions. Climate change is a troubling reality, with floods, fires, heatwaves, and melting polar ice caps contributing new challenges to biodiversity, sustainable development, human health, and the effective management of protected areas. Many environmental problems are worsening, especially the loss of species (at a rate at least 1000 times the background rate—Pimm 2021 ), so conserving biodiversity in the coming decade will need to be well aware of how land management can support national and global efforts to address climate change and adapt to it. Bengtsson et al. ( 2021 ) have shown how some of the guiding concepts have been developed.

The responses to climate change and biodiversity loss provide the necessary ingredients to support a substantial increase in the amount of land, freshwater, and saltwater habitats receiving effective conservation management. It is timely to again follow E.O. Wilson, who has suggested that half of the land and freshwater habitats and at least a third of the coastal and marine habitats should be under biodiversity-oriented spatial planning and management regimes (Wilson 2016 ). This could include protected areas, restoration of degraded lands, other effective habitat management, lands managed by Indigenous peoples, nature-based solutions, urban protected areas, and other conservation-based habitat management as called for by all of the contributors to this Ambio issue.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Bengtsson J, Angelstam P, Elmqvist T, Emanuelsson U, Folke C, Ihse M, Moberg F, Nyström M. Reserves, resilience and dynamic landscapes. Ambio. 2003; 32 :389–396. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447-32.6.389. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bengtsson, J., P. Angelstam, T. Elmqvist, U. Emanuelsson, C. Folke, M. Ihse, F. Moberg, and M. Nyström. 2021. Reserves, resilience and dynamic landscapes 20 years later. 50th Anniversary Collection: Biodiversity conservation. Ambio 50. 10.1007/s13280-020-01477-8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- CBD . The convention on biological diversity. Montreal: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity; 1992. [ Google Scholar ]

- Doyle C. Indigenous peoples, title to territory, rights and resources. New York: Routledge; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gadgil M, Berkes F, Folke C. Indigenous knowledge for biodiversity conservation. Ambio. 1993; 22 :151–156. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gadgil, M., F. Berkes, and C. Folke. 2021. Indigenous knowledge: From local to global. 50th Anniversary Collection: Biodiversity conservation. Ambio 50. 10.1007/s13280-020-01478-7. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Gilbert J. Indigenous peoples’ land rights under international law: From victims to actors. Leiden: Brill; 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hanski I. Habitat loss, the dynamics of biodiversity, and a perspective on conservation. Ambio. 2011; 40 :248–255. doi: 10.1007/s13280-011-0147-3. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hilty J, Worboys G, Keely A, Woodley S, Lauche B, Locke H, Carr M, Pulsford I, et al. Guidelines for conserving connectivity through ecological networks and corridors. Gland: International Union for Conservation of Nature; 2020. [ Google Scholar ]

- Maxwell S, Cazalis V, Dudley N, Hoffmann M, Rodrigues A, Stolton S, Visconti P, Woodley S, Kingston N, et al. Area-based conservation in the twenty-first century. Nature. 2020; 586 :217–227. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2773-z. [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pimm S. What is biodiversity conservation? 50th Anniversary Collection: Biodiversity conservation. Ambio. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s13280-020-01399-5. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sayer, J., C. Margules, and J.A. McNeely. 2021. People and biodiversity in the 21st century. 50th Anniversary Collection: Biodiversity conservation. Ambio 50. 10.1007/s13280-020-01476-9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- SCBD . Protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures. Montreal: Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity; 2018. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wilson EO. Sociobiology: The new synthesis. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1975. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wilson EO, editor. Biodiversity. Washington: National Academy Press; 1988. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wilson EO. Half-earth: Our planet’s fight for survival. New York: Norton; 2016. [ Google Scholar ]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 25 November 2019

Biodiversity’s contributions to sustainable development

- Malgorzata Blicharska 1 na1 ,

- Richard J. Smithers 2 na1 ,

- Grzegorz Mikusiński 3 ,

- Patrik Rönnbäck 1 ,

- Paula A. Harrison 4 ,

- Måns Nilsson 5 &

- William J. Sutherland 6

Nature Sustainability volume 2 , pages 1083–1093 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

7202 Accesses

106 Citations

56 Altmetric

Metrics details

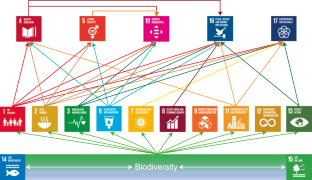

- Developing world

- Sustainability

International concern to develop sustainably challenges us to act upon the inherent links between our economy, society and environment, and is leading to increasing acknowledgement of biodiversity’s importance. This Review discusses the breadth of ways in which biodiversity can support sustainable development. It uses the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as a basis for exploring scientific evidence of the benefits delivered by biodiversity. It focuses on papers that provide examples of how biodiversity components (that is, ecosystems, species and genes) directly deliver benefits that may contribute to the achievement of individual SDGs. It also considers how biodiversity’s direct contributions to fulfilling some SDGs may indirectly support the achievement of other SDGs to which biodiversity does not contribute directly. How the attributes (for example, diversity, abundance or composition) of biodiversity components influence the benefits delivered is also presented, where described by the papers reviewed. While acknowledging potential negative impacts and trade-offs between different benefits, the study concludes that biodiversity may contribute to fulfilment of all SDGs.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

111,21 € per year

only 9,27 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Base map: Esri, DeLorme Publishing Company, Inc.

United Nations (UN/SDG).

Similar content being viewed by others

Mammal responses to global changes in human activity vary by trophic group and landscape

A. Cole Burton, Christopher Beirne, … Roland Kays

Expert review of the science underlying nature-based climate solutions

B. Buma, D. R. Gordon, … S. P. Hamburg

Australian human-induced native forest regeneration carbon offset projects have limited impact on changes in woody vegetation cover and carbon removals

Andrew Macintosh, Don Butler, … Paul Summerfield

World Commission on Environment and Development Our Common Future (Oxford Univ. Press, 1987).

Cardinale, B. J. et al. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 486 , 59–67 (2012). A review of two decades of research on how biodiversity loss influences ecosystem functions and the provision of goods and services .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Norström, A. V. et al. Three necessary conditions for establishing effective Sustainable Development Goals in the Anthropocene. Ecol. Soc. 19 , 8 (2014).

Article Google Scholar

Costanza, R. et al. Twenty years of ecosystem services: how far have we come and how far do we still need to go? Ecosyst. Serv. 28 , 1–16 (2017).

Blicharska, M. et al. Shades of grey challenge practical application of the Cultural Ecosystem Services concept. Ecosyst. Serv. 23 , 55–70 (2017).

Biodiversity and Sustainable Development: Technical Note (UNEP, 2016).

Note of Subsidiary Body on Scientific, Technical and Technological Advice Twenty-first Meeting: Biodiversity and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (SBSTTA, 2017).

Wood, S. L. R. et al. Distilling the role of ecosystem services in the Sustainable Development Goals. Ecosyst. Serv. 29 , 70–82 (2018).

Schultz, M., Tyrrell, T. D. & Ebenhard, T. The 2030 Agenda and Ecosystems - A Discussion Paper on the Links between the Aichi Biodiversity Targets and the Sustainable Development Goals (SwedBio at Stockholm Resilience Centre, 2016).

Summary for Policymakers of the Regional Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for Europe and Central Asia of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES, 2018).

Summary for Policymakers of the Regional Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for Africa of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES, 2018).

Summary for Policymakers of the Regional Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for the Americas of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES, 2018).

Summary for Policymakers of the Regional Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for Asia and the Pacific of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES, 2018).

Summary for Policymakers of the Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES, 2019).

Sachs, J. D. et al. Biodiversity conservation and the Millennium Development Goals. Science 325 , 1502–1503 (2009).

Carrasco, L. R., Chan, J., McGrath, F. L. & Nghiem, L. T. P. Biodiversity conservation in a telecoupled world. Ecol. Soc. 22 , 24 (2017).

Liu, J. An integrated framework for achieving Sustainable Development Goals around the world. Ecol. Econ. Soc. INSEE J. 1 , 11–17 (2018). A study introducing an integrated coupling framework for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals .

Google Scholar

Syrbe, R.-U. & Walz, U. Spatial indicators for the assessment of ecosystem services: Providing, benefiting and connecting areas and landscape metrics. Ecol. Indic. 21 , 80–88 (2012).

Ziter, C., Graves, R. A. & Turner, M. G. How do land-use legacies affect ecosystem services in United States cultural landscapes? Landsc. Ecol. 32 , 2205–2218 (2017).

O’Neill, B. C. et al. IPCC reasons for concern regarding climate change risks. Nat. Clim. Change 7 , 28–37 (2017).

Essl, F. et al. Historical legacies accumulate to shape future biodiversity in an era of rapid global change. Divers. Distrib. 21 , 534–547 (2015).

Raudsepp-Hearne, C. et al. Untangling the environmentalist’s paradox: why is human well-being increasing as ecosystem services degrade? Bioscience 60 , 576–589 (2010).

Gaston, K. J. Global patterns in biodiversity. Nature 405 , 220–227 (2000).

Mayer, A. L., Kauppi, P. E., Angelstam, P. K., Zhang, Y. & Tikka, P. M. Importing timber, exporting ecological impact. Science 308 , 359–360 (2005).

Human Development Report 2016: Human Development for Everyone (United Nations Development Programme, 2016).

Scholes, R. J. & Biggs, R. A biodiversity intactness index. Nature 434 , 45–49 (2005).

Lenzen, M. et al. International trade drives biodiversity threats in developing nations. Nature 486 , 109–112 (2012). A global analysis of the threats posed to biodiversity by international trade .

Moran, D., Petersone, M. & Verones, F. On the suitability of input output analysis for calculating product-specific biodiversity footprints. Ecol. Indic. 60 , 192–201 (2016).

Angelsen, A. et al. Environmental income and rural livelihoods: a global-comparative analysis. World Dev. 64 , S12–S28 (2014).

Abdullah, A. N. M., Stacey, N., Garnett, S. T. & Myers, B. Economic dependence on mangrove forest resources for livelihoods in the Sundarbans, Bangladesh. Forest Policy Econ. 64 , 15–24 (2016).

Keesing, F. et al. Impacts of biodiversity on the emergence and transmission of infectious diseases. Nature 468 , 647–652 (2010). A comprehensive review of the evidence that biodiversity loss affects the transmission of infectious diseases .

Hartig, T., Mang, M. & Evans, G. W. Restorative effects of natural-environment experiences. Environ. Behav. 23 , 3–26 (1991).

Ulrich, R. S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 224 , 420–421 (1984).

van den Bosch, M. & Sang, A. O. Urban natural environments as nature-based solutions for improved public health - a systematic review of reviews. Environ. Res. 158 , 373–384 (2017). A systematic review of the health effects of nature-based solutions .

Veitch, J. et al. Park availability and physical activity, TV time, and overweight and obesity among women: findings from Australia and the United States. Health Place 38 , 96–102 (2016).

Hanski, I. et al. Environmental biodiversity, human microbiota, and allergy are interrelated. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109 , 8334–8339 (2012).

Feng, X. Q. & Astell-Burt, T. Is neighborhood green space protective against associations between child asthma, neighborhood traffic volume and perceived lack of area safety? Multilevel analysis of 4447 Australian children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 14 , 543 (2017).

Cipriani, J. et al. A systematic review of the effects of horticultural therapy on persons with mental health conditions. Occup. Ther. Ment. Health 33 , 47–69 (2017).

Bonan, G. B. Forests and climate change: forcings, feedbacks, and the climate benefits of forests. Science 320 , 1444–1449 (2008).

Griscom, B. W. et al. Natural climate solutions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114 , 11645–11650 (2017). A study identifying and quantifying nature-based solutions to climate change .

Johnson, C. N. et al. Biodiversity losses and conservation responses in the Anthropocene. Science 356 , 270–274 (2017).

Gamfeldt, L. et al. Higher levels of multiple ecosystem services are found in forests with more tree species. Nat. Commun. 4 , 1430 (2013).

Liu, C. L. C., Kuchma, O. & Krutovsky, K. V. Mixed-species versus monocultures in plantation forestry: development, benefits, ecosystem services and perspectives for the future. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 15 , e00419 (2018).

Jones, H. P., Hole, D. G. & Zavaleta, E. S. Harnessing nature to help people adapt to climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 2 , 504–509 (2012).

Pramova, E., Locatelli, B., Djoudi, H. & Somorin, O. A. Forests and trees for social adaptation to climate variability and change. WIREs Clim. Change 3 , 581–596 (2012).

Bullock, A. & Acreman, M. The role of wetlands in the hydrological cycle. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 7 , 358–389 (2003).

Farley, K. A., Jobbágy, E. G. & Jackson, R. B. Effects of afforestation on water yield: a global synthesis with implications for policy. Glob. Change Biol. 11 , 1565–1576 (2005).

Thomas, H. & Nisbet, T. An assessment of the impact of floodplain woodland on flood flows. Water Environ. J. 21 , 114–126 (2007).

Quinton, J. N., Edwards, G. M. & Morgan, R. P. C. The influence of vegetation species and plant properties on runoff and soil erosion: results from a rainfall simulation study in south east Spain. Soil Use Manag. 13 , 143–148 (1997).

Gedan, K. B., Kirwan, M. L., Wolanski, E., Barbier, E. B. & Silliman, B. R. The present and future role of coastal wetland vegetation in protecting shorelines: answering recent challenges to the paradigm. Clim. Change 106 , 7–29 (2011).

Brandon, C. M., Woodruff, J. D., Orton, P. M. & Donnelly, J. P. Evidence for elevated coastal vulnerability following large-scale historical oyster bed harvesting. Earth Surf. Process. Landf. 41 , 1136–1143 (2016).

Ouyang, X. G., Lee, S. Y., Connolly, R. M. & Kainz, M. J. Spatially-explicit valuation of coastal wetlands for cyclone mitigation in Australia and China. Sci. Rep. 8 , 3035 (2018).

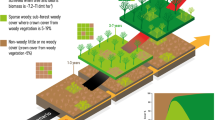

Nawaz, R., McDonald, A. & Postoyko, S. Hydrological performance of a full-scale extensive green roof located in a temperate climate. Ecol. Eng. 82 , 66–80 (2015).

Brandao, C., Cameira, M. D., Valente, F., de Carvalho, R. C. & Paco, T. A. Wet season hydrological performance of green roofs using native species under Mediterranean climate. Ecol. Eng. 102 , 596–611 (2017).

Vijayaraghavan, K. Green roofs: a critical review on the role of components, benefits, limitations and trends. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 57 , 740–752 (2016).

Wong, N. H. et al. The effects of rooftop garden on energy consumption of a commercial building in Singapore. Energy Build. 35 , 353–364 (2003).

Getter, K. L. & Rowe, D. B. The role of extensive green roofs in sustainable development. Hortscience 41 , 1276–1285 (2006).

Guo, Z. W., Zhang, L. & Li, Y. M. Increased dependence of humans on ecosystem services and biodiversity. PloS ONE 5 , e13113 (2010).

Balmford, A. et al. A global perspective on trends in nature-based tourism. PloS Biol. 7 , e1000144 (2009).

Brink, E. et al. Cascades of green: a review of ecosystem-based adaptation in urban areas. Glob. Environ. Change-Hum. Policy Dimens. 36 , 111–123 (2016).

Trepel, M. Assessing the cost-effectiveness of the water purification function of wetlands for environmental planning. Ecol. Complex. 7 , 320–326 (2010).

Shen, Y. Q., Liao, X. C. & Yin, R. S. Measuring the socioeconomic impacts of China’s Natural Forest Protection Program. Environ. Dev. Econ. 11 , 769–788 (2006).

Thrupp, L. A. Linking agricultural biodiversity and food security: the valuable role of agrobiodiversity for sustainable agriculture. Int. Aff. 76 , 283–297 (2000).

Duffy, J. E., Godwin, C. M. & Cardinale, B. J. Biodiversity effects in the wild are common and as strong as key drivers of productivity. Nature 549 , 261–265 (2017).

Worm, B. et al. Impacts of biodiversity loss on ocean ecosystem services. Science 314 , 787–790 (2006). A global analysis revealing the importance of biodiversity for the productivity and stability of marine ecosystems .

Winfree, R. et al. Species turnover promotes the importance of bee diversity for crop pollination at regional scales. Science 359 , 791–793 (2018).

Klein, A. M. et al. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proc. Royal Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 274 , 303–313 (2007).

O’Bryan, C. J. et al. The contribution of predators and scavengers to human well-being. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2 , 229–236 (2018). A comprehensive review of the role of predators in providing a range of benefits for people .

Haddad, N. M., Crutsinger, G. M., Gross, K., Haarstad, J. & Tilman, D. Plant diversity and the stability of foodwebs. Ecol. Lett. 14 , 42–46 (2011).

Chaplin-Kramer, R. & Kremen, C. Pest control experiments show benefits of complexity at landscape and local scales. Ecol. Appl. 22 , 1936–1948 (2012).

Bale, J. S., van Lenteren, J. C. & Bigler, F. Biological control and sustainable food production. Philos. Trans. Royal Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 363 , 761–776 (2008).

Motlhanka, D. M. & Makhabu, S. W. Medicinal and edible wild fruit plants of Botswana as emerging new crop opportunities. J. Med. Plants Res. 5 , 1836–1842 (2011).

Jackson, L. et al. Biodiversity and agricultural sustainagility: from assessment to adaptive management. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2 , 80–87 (2010).

Lachat, C. et al. Dietary species richness as a measure of food biodiversity and nutritional quality of diets. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115 , 127–132 (2018).

Flint, H. J., Scott, K. P., Louis, P. & Duncan, S. H. The role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 9 , 577–589 (2012).

Belkaid, Y. & Hand, T. W. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell 157 , 121–141 (2014).

Atanasov, A. G. et al. Discovery and resupply of pharmacologically active plant-derived natural products: a review. Biotechnol. Adv. 33 , 1582–1614 (2015).

Alves, R. R. N. & Alves, H. N. The faunal drugstore: animal-based remedies used in traditional medicines in Latin America. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 7 , 9 (2011).

Golden, C. D., Fernald, L. C. H., Brashares, J. S., Rasolofoniaina, B. J. R. & Kremen, C. Benefits of wildlife consumption to child nutrition in a biodiversity hotspot. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 108 , 19653–19656 (2011).

Liu, L., Guan, D. S. & Peart, M. R. The morphological structure of leaves and the dust-retaining capability of afforested plants in urban Guangzhou, South China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 19 , 3440–3449 (2012).

Fuller, R. A., Irvine, K. N., Devine-Wright, P., Warren, P. H. & Gaston, K. J. Psychological benefits of greenspace increase with biodiversity. Biol. Lett. 3 , 390–394 (2007).

Hedblom, M., Heyman, E., Antonsson, H. & Gunnarsson, B. Bird song diversity influences young people’s appreciation of urban landscapes. Urban For. Urban Green. 13 , 469–474 (2014).

Cameron, R. W. F., Taylor, J. & Emmett, M. A Hedera green facade - energy performance and saving under different maritime-temperate, winter weather conditions. Build. Environ. 92 , 111–121 (2015).

Lurie-Luke, E. Product and technology innovation: what can biomimicry inspire? Biotechnol. Adv. 32 , 1494–1505 (2014).

Caracciolo, A. B., Topp, E. & Grenni, P. Pharmaceuticals in the environment: biodegradation and effects on natural microbial communities. A review. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 106 , 25–36 (2015).

Megharaj, M., Ramakrishnan, B., Venkateswarlu, K., Sethunathan, N. & Naidu, R. Bioremediation approaches for organic pollutants: a critical perspective. Environ. Int. 37 , 1362–1375 (2011).

Six, J., Frey, S. D., Thiet, R. K. & Batten, K. M. Bacterial and fungal contributions to carbon sequestration in agroecosystems. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 70 , 555–569 (2006).

Martin, T. L., Trevors, J. T. & Kaushik, N. K. Soil microbial diversity, community structure and denitrification in a temperate riparian zone. Biodivers. Conserv. 8 , 1057–1078 (1999).

Cardinale, B. J. Biodiversity improves water quality through niche partitioning. Nature 472 , 86–89 (2011).

Kulshreshtha, A., Agrawal, R., Barar, M. & Saxena, S. A review on bioremediation of heavy metals in contaminated water. IOSR J. Environ. Sci. Toxicol. Food Technol. 8 , 44–50 (2014).

Hewett, D. G. The colonization of sand dunes after stabilization with Marram Grass (Ammophila Arenaria). J. Ecol. 58 , 653–668 (1970).

Di Minin, E., Fraser, I., Slotow, R. & MacMillan, D. C. Understanding heterogeneous preference of tourists for big game species: implications for conservation and management. Animal Conserv. 16 , 249–258 (2013).

Hoffmann, A. A. & Sgro, C. M. Climate change and evolutionary adaptation. Nature 470 , 479–485 (2011).

Ruiz, K. B. et al. Quinoa biodiversity and sustainability for food security under climate change. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 34 , 349–359 (2014).

Muñoz, N., Liu, A., Kan, L., Li, M.-W. & Lam, H.-M. Potential uses of wild germplasms of grain legumes for crop improvement. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18 , 328 (2017).

Burke, M. B., Lobell, D. B. & Guarino, L. Shifts in African crop climates by 2050, and the implications for crop improvement and genetic resources conservation. Glob. Environ. Change-Hum. Policy Dimens. 19 , 317–325 (2009).

Arrieta, J. M., Arnaud-Haond, S. & Duarte, C. M. What lies underneath: conserving the oceans’ genetic resources. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107 , 18318–18324 (2010).

Swanson, T. The reliance of northern economies on southern biodiversity: biodiversity as information. Ecol. Econ. 17 , 1–8 (1996).

David, B., Wolfender, J. L. & Dias, D. A. The pharmaceutical industry and natural products: historical status and new trends. Phytochem. Rev. 14 , 299–315 (2015).

Duncan, G. J., Brooksgunn, J. & Klebanov, P. K. Economic deprivation and early-childhood developments. Child Dev. 65 , 296–318 (1994).

Victora, C. G. et al. Maternal and child undernutrition 2 - Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital. Lancet 371 , 340–357 (2008).

Goodman, J., Hurwitz, M., Park, J. & Smith, J. Heat and Learning (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2018).

Cole, L. B., McPhearson, T., Herzog, C. P. & Russ, A. in Urban Environmental Education Review (eds Russ, A. & Krasny, M. E.) 261–270 (Cornell Univ. Press, 2017).

Kevany, K. & Huisingh, D. A review of progress in empowerment of women in rural water management decision-making processes. J. Clean. Prod. 60 , 53–64 (2013).

Patria, H. D. Uncultivated biodiversity in women’s hand: how to create food sovereignty. Asian J. Women’s Stud. 19 , 148–161 (2013).

Adekola, O., Mitchell, G. & Grainger, A. Inequality and ecosystem services: the value and social distribution of Niger Delta wetland services. Ecosyst. Serv. 12 , 42–54 (2015).

Bogar, S. & Beyer, K. M. Green space, violence, and crime: a systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse 17 , 160–171 (2016).

Schleussner, C. F., Donges, J. F., Donner, R. V. & Schellnhuber, H. J. Armed-conflict risks enhanced by climate-related disasters in ethnically fractionalized countries. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113 , 9216–9221 (2016).

Wischnath, G. & Buhaug, H. Rice or riots: on food production and conflict severity across India. Political Geogr. 43 , 6–15 (2014).

Aspergis, N. Education and democracy: new evidence from 161 countries. Econ. Model. 71 , 59–67 (2018).

McCoy, D., Chigudu, S. & Tillmann, T. Framing the tax and health nexus: a neglected aspect of public health concern. Health Econ. Policy Law 12 , 179–194 (2017).

Truong, C., Trück, S. & Mathew, S. Managing risks from climate impacted hazards – the value of investment flexibility under uncertainty. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 269 , 132–145 (2018).

Lectard, P. & Rougier, E. Can developing countries gain from defying comparative advantage? Distance to comparative advantage, export diversification and sophistication, and the dynamics of specialization. World Dev. 102 , 90–110 (2018).

Ehrlich, P. R. & Ehrlich, A. H. The population bomb revisited. Electron. J. Sustain. Dev 1 , 5–13 (2009).

NRC The State of Canada’s Forests. Annual Report 2017 (Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, 2017).

Rackham, O. Ancient Woodland: Its History, Vegetation and Uses in England (Castlepoint Press, 1983).

Forestry Statistics 2017 (Forestry Commission, 2017).

Mace, G. M. et al. Aiming higher to bend the curve of biodiversity loss. Nat. Sustain. 1 , 448–451 (2018).

Scharlemann, J. P. W. et al. Global Goals Mapping: The Environment-human Landscape. A Contribution Towards the NERC, The Rockefeller Foundation and ESRC Initiative, Towards a Sustainable Earth: Environment-human Systems and the UN Global Goals (Sussex Sustainability Research Programme, University of Sussex and UN Environment World Conservation Monitoring Centre, 2016).

Wolosin, M. Large-scale Forestation for Climate Mitigation: Lessons from South Korea, China, and India (Climate and Land Use Alliance, 2017).

Smithers, R. J., Blicharska, M. & Laurance, W. F. Biodiversity boundaries. Science 353 , 1108 (2016).

Newbold, T. et al. Has land use pushed terrestrial biodiversity beyond the planetary boundary? A global assessment. Science 353 , 288–291 (2016).

Wilson, E. O. Biophilia (Harvard Univ. Press, 1986).

Roe, D. et al. Which components or attributes of biodiversity influence which dimensions of poverty? Environ. Evid. 3 , 3 (2014).

Tanaka, N., Sasaki, Y., Mowjood, M. I. M., Jinadasa, K. B. S. N. & Homchuen, S. Coastal vegetation structures and their functions in tsunami protection: experience of the recent Indian Ocean tsunami. Landsc. Ecol. Eng. 33 , 33–45 (2007).

Mishra, A. et al. Building ex ante resilience of disaster-exposed mountain communities: drawing insights from the Nepal earthquake recovery. Int. J. Disast. Risk Reduct. 22 , 167–178 (2017).

von Wettberg, E. J. B. et al. Ecology and genomics of an important crop wild relative as a prelude to agricultural innovation. Nat. Commun. 9 , 649 (2018).

Ricketts, T. H., Daily, G. C., Ehrlich, P. R. & Michener, C. D. Economic value of tropical forest to coffee production. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101 , 12579–12582 (2004).

Wall, D. H., Nielsen, U. N. & Six, J. Soil biodiversity and human health. Nature 528 , 69–76 (2015).

Beckett, K. P., Freer-Smith, P. H. & Taylor, G. Particulate pollution capture by urban trees: effect of species and windspeed. Glob. Change Biol. 6 , 995–1003 (2000).

Rahman, M. A., Armson, D. & Ennos, A. R. A comparison of the growth and cooling effectiveness of five commonly planted urban tree species. Urban Ecosyst. 18 , 371–389 (2015).

Santos, A. et al. The role of forest in mitigating the impact of atmospheric dust pollution in a mixed landscape. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 24 , 12038–12048 (2017).

Detweiler, M. B. et al. Horticultural therapy: a pilot study on modulating cortisol levels and indices of substance craving, posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and quality of life in veterans. Altern. Ther. Health Med. 21 , 36–41 (2015).

Taylor, M. S., Wheeler, B. W., White, M. P., Economou, T. & Osborne, N. J. Research note: Urban street tree density and antidepressant prescription rates—A cross-sectional study in London, UK. Landsc. Urban Plan. 136 , 174–179 (2015).

Johnson, C., Schweinhart, S. & Buffam, I. Plant species richness enhances nitrogen retention in green roof plots. Ecol. Appl. 26 , 2130–2144 (2016).

Meerburg, B. G. et al. Surface water sanitation and biomass production in a large constructed wetland in the Netherlands. Wetl. Ecol. Manag. 18 , 463–470 (2010).

Osborne, L. L. & Kovacic, D. A. Riparian vegetated buffer strips in water-quality restoration and stream management. Freshw. Biol. 29 , 243–258 (1993).

Verhoeven, J. T. A., Arheimer, B., Yin, C. & Hefting, M. M. Regional and global concerns over wetlands and water quality. Trends Ecol. Evol. 21 , 96–103 (2006).

Brauman, K. A., Freyberg, D. L. & Daily, G. C. Forest structure influences on rainfall partitioning and cloud interception: a comparison of native forest sites in Kona, Hawaii. Agric. For. Meteorol. 150 , 265–275 (2010).

Bailis, R., Drigo, R., Ghilardi, A. & Masera, O. The carbon footprint of traditional woodfuels. Nat. Clim. Change 5 , 266–272 (2015).

Elliott, L. G. et al. Establishment of a bioenergy-focused microalgal culture collection. Algal Res. 1 , 102–113 (2012).

Heinsoo, K., Melts, I., Sammul, M. & Holm, B. The potential of Estonian semi-natural grasslands for bioenergy production. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 137 , 86–92 (2010).

Dornburg, V. et al. Bioenergy revisited: key factors in global potentials of bioenergy. Energy Environ. Sci. 3 , 258–267 (2010).

Wang, Z. H., Zhao, X. X., Yang, J. C. & Song, J. Y. Cooling and energy saving potentials of shade trees and urban lawns in a desert city. Appl. Energy 161 , 437–444 (2016).

Palmer, C. & Di Falco, S. Biodiversity, poverty, and development. Oxf. Rev. Econ. Policy 28 , 48–68 (2012).

Tumusiime, D. M. & Vedeld, P. Can biodiversity conservation benefit local people? Costs and benefits at a strict protected area in Uganda. J. Sustain. For. 34 , 761–786 (2015).

Tzoulas, K. et al. Promoting ecosystem and human health in urban areas using Green Infrastructure: a literature review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 81 , 167–178 (2007).

Schilling, J. & Logan, J. Greening the Rust Belt: a green infrastructure model for right sizing America’s shrinking cities. J. Am. Plan. Assoc. 74 , 451–466 (2008).

Berardi, U., GhaffarianHoseini, A. H. & GhaffarianHoseini, A. State-of-the-art analysis of the environmental benefits of green roofs. Appl. Energy 115 , 411–428 (2014).

Charlesworth, S. M., Perales-Momparler, S., Lashford, C. & Warwick, F. The sustainable management of surface water at the building scale: preliminary results of case studies in the UK and Spain. J. Water Supply Res. Technol.-Aqua 62 , 534–544 (2013).

Vineyard, D. et al. Comparing green and grey infrastructure using life cycle cost and environmental impact: a rain garden case study in Cincinnati, OH. J. Am. Water Resour. Assoc. 51 , 1342–1360 (2015).

Dong, X., Guo, H. & Zeng, S. Y. Enhancing future resilience in urban drainage system: green versus grey infrastructure. Water Res. 124 , 280–289 (2017).

Renaud, F. G., Sudmeier-Rieux, K., Estrella, M. & Nehren, U. Ecosystem-based Disaster Risk Reduction and Adaptation in Practice (Springer, 2016).

Hausmann, A., Slotow, R., Burns, J. K. & Di Minin, E. The ecosystem service of sense of place: benefits for human well-being and biodiversity conservation. Environ. Conserv. 43 , 117–127 (2016).

Blicharska, M. & Mikusiński, G. Incorporating social and cultural significance of large old trees in conservation policy. Conserv. Biol. 28 , 1558–1567 (2014).

Rotherham, I. D. Bio-cultural heritage and biodiversity: emerging paradigms in conservation and planning. Biodivers. Conserv. 24 , 3405–3429 (2015).

Bhagwat, S. A. & Rutte, C. Sacred groves: potential for biodiversity management. Front. Ecol. Environ. 4 , 519–524 (2006).

Kabisch, N., van den Bosch, M. & Lafortezza, R. The health benefits of nature-based solutions to urbanization challenges for children and the elderly - a systematic review. Environ. Res. 159 , 362–373 (2017).

Gunnarsson, B., Knez, I., Hedblom, M. & Sang, A. O. Effects of biodiversity and environment-related attitude on perception of urban green space. Urban Ecosyst. 20 , 37–49 (2017).

Nielsen, A. B., van den Bosch, M., Maruthaveeran, S. & van den Bosch, C. K. Species richness in urban parks and its drivers: a review of empirical evidence. Urban Ecosyst. 17 , 305–327 (2014).

Shanahan, D. F., Fuller, R. A., Bush, R., Lin, B. B. & Gaston, K. J. The health benefits of urban nature: how much do we need? BioScience 65 , 476–485 (2015).

McVittie, A., Cole, L., Wreford, A., Sgobbi, A. & Yordi, B. Ecosystem-based solutions for disaster risk reduction: lessons from European applications of ecosystem-based adaptation measures. Int. J. Disast. Risk Reduct. 32 , 42–54 (2018).

Salick, J. et al. Tibetan sacred sites conserve old growth trees and cover in the eastern Himalayas. Biodivers. Conserv. 16 , 693–706 (2007).

Aydin, S. et al. Aerobic and anaerobic fungal metabolism and Omics insights for increasing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons biodegradation. Fungal Biol. Rev. 31 , 61–72 (2017).

Ehlers, A., Worm, B. & Reusch, T. B. H. Importance of genetic diversity in eelgrass Zostera marina for its resilience to global warming. Mar. Ecol.-Prog. Ser. 355 , 1–7 (2008).

Wilmers, C. C. & Getz, W. M. Gray wolves as climate change buffers in Yellowstone. PloS Biol. 3 , 571–576 (2005).

Steffen, W. et al. Planetary boundaries: guiding human development on a changing planet. Science 347 , 1259855 (2015).

Stahel, W. R. The circular economy. Nature 531 , 435–438 (2016).

Burch-Brown, J. & Archer, A. In defence of biodiversity. Biol. Philos. 32 , 969–997 (2017).

Myers, N., Mittermeier, R. A., Mittermeier, C. G., da Fonseca, G. A. B. & Kent, J. Biodiversity hotspots for conservation priorities. Nature 403 , 853–858 (2000).

Shaw, J. D., Terauds, A., Riddle, M. J., Possingham, H. P. & Chown, S. L. Antarctica’s protected areas are inadequate, unrepresentative, and at risk. PloS Biol. 12 , e1001888 (2014).

Roe, D., Elliott, J., Sandbrook, C. & Walpole, M. in Biodiversity Conservation and Poverty Alleviation: Exploring the Evidence for a Link (eds Roe, D. et al.) 3–18 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2013).

Redford, K. H. & Richter, B. D. Conservation of biodiversity in a world of use. Conserv. Biol. 13 , 1246–1256 (1999).

Download references

Author information

These authors contributed equally: Malgorzata Blicharska, Richard J. Smithers.

Authors and Affiliations

Natural Resources and Sustainable Development, Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden

Malgorzata Blicharska & Patrik Rönnbäck

Ricardo Energy & Environment, Didcot, UK

Richard J. Smithers

Grimsö Wildlife Research Station, Department of Ecology, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), Riddarhyttan, Sweden

Grzegorz Mikusiński

Centre for Ecology & Hydrology, Lancaster Environment Centre, Lancaster, UK

Paula A. Harrison

Stockholm Environment Institute, Stockholm, Sweden

Måns Nilsson

Department of Zoology, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK

William J. Sutherland

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

M.B. and R.J.S. conceived the Review and wrote the manuscript. M.B. undertook the literature search and was supported by R.J.S. in identifying relevant examples. G.M. undertook the analysis for Fig. 1 . All authors contributed to ideas and editing.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Malgorzata Blicharska .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Supplementary Information sections 1–2, table and refs. 1–4.

Rights and permissions