Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Working with sources

- What Is Critical Thinking? | Definition & Examples

What Is Critical Thinking? | Definition & Examples

Published on May 30, 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on May 31, 2023.

Critical thinking is the ability to effectively analyze information and form a judgment .

To think critically, you must be aware of your own biases and assumptions when encountering information, and apply consistent standards when evaluating sources .

Critical thinking skills help you to:

- Identify credible sources

- Evaluate and respond to arguments

- Assess alternative viewpoints

- Test hypotheses against relevant criteria

Table of contents

Why is critical thinking important, critical thinking examples, how to think critically, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about critical thinking.

Critical thinking is important for making judgments about sources of information and forming your own arguments. It emphasizes a rational, objective, and self-aware approach that can help you to identify credible sources and strengthen your conclusions.

Critical thinking is important in all disciplines and throughout all stages of the research process . The types of evidence used in the sciences and in the humanities may differ, but critical thinking skills are relevant to both.

In academic writing , critical thinking can help you to determine whether a source:

- Is free from research bias

- Provides evidence to support its research findings

- Considers alternative viewpoints

Outside of academia, critical thinking goes hand in hand with information literacy to help you form opinions rationally and engage independently and critically with popular media.

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

Critical thinking can help you to identify reliable sources of information that you can cite in your research paper . It can also guide your own research methods and inform your own arguments.

Outside of academia, critical thinking can help you to be aware of both your own and others’ biases and assumptions.

Academic examples

However, when you compare the findings of the study with other current research, you determine that the results seem improbable. You analyze the paper again, consulting the sources it cites.

You notice that the research was funded by the pharmaceutical company that created the treatment. Because of this, you view its results skeptically and determine that more independent research is necessary to confirm or refute them. Example: Poor critical thinking in an academic context You’re researching a paper on the impact wireless technology has had on developing countries that previously did not have large-scale communications infrastructure. You read an article that seems to confirm your hypothesis: the impact is mainly positive. Rather than evaluating the research methodology, you accept the findings uncritically.

Nonacademic examples

However, you decide to compare this review article with consumer reviews on a different site. You find that these reviews are not as positive. Some customers have had problems installing the alarm, and some have noted that it activates for no apparent reason.

You revisit the original review article. You notice that the words “sponsored content” appear in small print under the article title. Based on this, you conclude that the review is advertising and is therefore not an unbiased source. Example: Poor critical thinking in a nonacademic context You support a candidate in an upcoming election. You visit an online news site affiliated with their political party and read an article that criticizes their opponent. The article claims that the opponent is inexperienced in politics. You accept this without evidence, because it fits your preconceptions about the opponent.

There is no single way to think critically. How you engage with information will depend on the type of source you’re using and the information you need.

However, you can engage with sources in a systematic and critical way by asking certain questions when you encounter information. Like the CRAAP test , these questions focus on the currency , relevance , authority , accuracy , and purpose of a source of information.

When encountering information, ask:

- Who is the author? Are they an expert in their field?

- What do they say? Is their argument clear? Can you summarize it?

- When did they say this? Is the source current?

- Where is the information published? Is it an academic article? Is it peer-reviewed ?

- Why did the author publish it? What is their motivation?

- How do they make their argument? Is it backed up by evidence? Does it rely on opinion, speculation, or appeals to emotion ? Do they address alternative arguments?

Critical thinking also involves being aware of your own biases, not only those of others. When you make an argument or draw your own conclusions, you can ask similar questions about your own writing:

- Am I only considering evidence that supports my preconceptions?

- Is my argument expressed clearly and backed up with credible sources?

- Would I be convinced by this argument coming from someone else?

If you want to know more about ChatGPT, AI tools , citation , and plagiarism , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- ChatGPT vs human editor

- ChatGPT citations

- Is ChatGPT trustworthy?

- Using ChatGPT for your studies

- What is ChatGPT?

- Chicago style

- Paraphrasing

Plagiarism

- Types of plagiarism

- Self-plagiarism

- Avoiding plagiarism

- Academic integrity

- Consequences of plagiarism

- Common knowledge

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

Critical thinking skills include the ability to:

You can assess information and arguments critically by asking certain questions about the source. You can use the CRAAP test , focusing on the currency , relevance , authority , accuracy , and purpose of a source of information.

Ask questions such as:

- Who is the author? Are they an expert?

- How do they make their argument? Is it backed up by evidence?

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

Information literacy refers to a broad range of skills, including the ability to find, evaluate, and use sources of information effectively.

Being information literate means that you:

- Know how to find credible sources

- Use relevant sources to inform your research

- Understand what constitutes plagiarism

- Know how to cite your sources correctly

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search, interpret, and recall information in a way that aligns with our pre-existing values, opinions, or beliefs. It refers to the ability to recollect information best when it amplifies what we already believe. Relatedly, we tend to forget information that contradicts our opinions.

Although selective recall is a component of confirmation bias, it should not be confused with recall bias.

On the other hand, recall bias refers to the differences in the ability between study participants to recall past events when self-reporting is used. This difference in accuracy or completeness of recollection is not related to beliefs or opinions. Rather, recall bias relates to other factors, such as the length of the recall period, age, and the characteristics of the disease under investigation.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Ryan, E. (2023, May 31). What Is Critical Thinking? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 9, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/critical-thinking/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, student guide: information literacy | meaning & examples, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, applying the craap test & evaluating sources, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Critical Thinking pp 57–86 Cite as

Ethical Thinking

- Dirk Jahn 3 &

- Michael Cursio 4

- First Online: 10 December 2023

71 Accesses

The word “ethics,” which gives its name to the corresponding philosophical discipline, derives from the ancient Greek “ethos,” in which three different yet related meanings can be distinguished. Firstly, it simply means the place where one lives; secondly, the socially established habits, customs, and traditions; and thirdly, the personal attitude or the character of a person.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

A little more detail on this (Safranski, 1997 ).

Normative validity claims in the sense of regulations, e.g., of a methodological nature, however, also played a role above. Here we concentrate on moral norms.

That there is also a descriptive ethics in the sense of the investigation of factually found moral concepts, we leave out of consideration here.

In order not to complicate the idea, we will refrain from arguing normatively in a non-moral sense, i.e., rationally in terms of purpose, e.g., that such arms deliveries damage Germany’s reputation. This in turn presupposes that the purpose towards which the argument is being made here (Germany’s positive reputation) is desirable. In justifying this purpose, in turn, we would have to reach a point at some point that can no longer be justified by higher-level purposes, but is good “par excellence”. This claim is what distinguishes moral norms from other norms.

Although utilitarianism, which is close to such a view, also has adherents in our time, we will go into this later.

The example comes from Robert Spaemann’s book Moral Basic Concepts (Spaemann, 1999 ), which, despite its age, is highly recommended as an introduction to ethics.

We must largely leave aside the significant approaches of antiquity.

The following description is largely based on Höffe ( 1992 ).

On this also (Höffe, 1992 ).

The following consideration is inspired by Forschner ( 1998 ).

Reference should be made here to the presentation in (Gebauer et al., 2009 ), which is excellently suited for teaching purposes and which is included here, among others.

However, Jonas does not yet emphasize the intrinsic value of nature as vehemently as other authors, e.g., Spaemann, do.

For example, Höffe advises a rational and sober balance that sensibly weighs opportunities and risks (Höffe, 1993 ).

(Pieper & Thurnherr, 1998 ; Nida-Rümelin, 2002 ), recommended for didactic purposes (Goergen & Frericks, 2009 ; Gebauer et al., 2009 ; Nickl, 2002 ).

In 2019 in Germany alone 2,902,348 (Tierschutzbund, 2021).

For example, according to the Federal Statistical Office, 55.1 million pigs were slaughtered in Germany in 2019 (Statisches Bundesamt, 2021).

Bentham. (1992). Eine Einführung in die Prinzipien der Moral und Gesetzgebung. In O. Höffe (Ed.), Einführung in die utilitaristische Ethik (pp. 55–83). utb.

Google Scholar

Birnbaum, R., & Ismar, G. (2020). Schäuble will dem Schutz des Lebens nicht alles unterordnen. DER TAGESSPIEGEL . https://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/bundestagspraesident-zur-corona-krise-schaeuble-will-dem-schutz-des-lebens-nicht-alles-unterordnen/25770466.html

Cohen, C. (2001). The animal rights debate . Rowman and Littlefield.

Cohen, C. (2008). Warum Tiere keine Rechte haben. In U. Wolf (Ed.), Texte zur Tierethik (pp. 51–55). Reclam.

Cursio, M. (2013). Was bedeutet Ethik im Design? In P. Krüll (Ed.), Who but: Magazin der Fakultät Design an der Technischen Hochschule Nürnberg (pp. 213–224). Verlag für Moderne Kunst.

Ethik-Kommission. (2017). Automatisiertes und vernetztes Fahren . Von Bundesministerium für Verkehr und digitale Infrastruktur. https://www.bmvi.de/SharedDocs/DE/Publikationen/DG/bericht-der-ethik-kommission.pdf?__blob=publicationFile . Accessed 20 Juni 2017.

Forschner, M. (1994). Über das Glück des Menschen . Wiss. Buchges.

Forschner, M. (1998). Über das Handeln des Menschen im Einklang mit der Natur. Grundlagen ethischer Verständigung . Primus.

Gebauer, M. (2019). Rüstungsexporte. Regierung genehmigt Waffenlieferungen nach Indien und Algerien. Von Spiegel Politik. https://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/ruestungsexporte-regierung-genehmigt-waffenlieferungen-nach-indien-und-algerien-a-1285044.html

Gebauer, D., Kres, L., & Moisel, J. (2009). Abitur-Wissen Ethik . Stark.

Goergen, K., & Frericks, H. (2009). Mein Ziel: Abitur Ethik . Manz.

Höffe, O. (1992). Einführung. In O. Höffe (Ed.), Einführung in die utilitaristische Ethik. Klassische und zeitgenössische Texte. Klassische und zeitgenössische Texte (pp. 7–51). UTB.

Höffe, O. (1993). Moral als Preis der Moderne . Suhrkamp.

Höffe, O. (1995). Kategorische Rechtsprinzipien . Suhrkamp.

Höffe, O. (2018). Ethik. Eine Einführung . Beck.

Hohmann, K. (2005). Einführung in die Wirtschaftsethik . Lit.

Jonas, H. (1984). Das Prinzip Verantwortung. Versuch einer Ethik für die technologische Zivilisation . Suhrkamp.

Kant, I. (1984). Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten . Reclam.

Krones, T. (2020). Corona-Massnahmen in der Kritik: “Mit dem Besuchsverbot sind wir definitiv zu weit gegangen” (K. &. Gentinetta, Interviewer) Von. https://www.nzz.ch/video/nzz-standpunkte/corona-massnahmen-in-der-kritik-mit-dem-besuchsverbot-sind-wir-definitiv-zu-weit-gegangen-ld.1559559

Malburg, M. (2020). Ein Wissenschaftler ist kein Politiker . Von nd. Journalismus von links. https://www.neues-deutschland.de/artikel/1135018.christian-drosten-ein-wissenschaftler-ist-kein-politiker.html

Mittelstraß, J. (2001). Wissen und Grenzen. Philosophische Studien . Suhrkamp.

Nickl, G. (2002). Wissenschaft. Technik. Verantwortung . Stark.

Nida-Rümelin, J. (2002). Ethische essays . Suhrkamp.

Nida-Rümelin, J. (2018). Unaufgeregter Realismus. Eine philosophische Streitschrift . mentis.

Book Google Scholar

Nida-Rümelin, J. (2020). Gesellschaft handlungsfähig halten . Von ZDF.de. https://www.zdf.de/nachrichten/zdf-morgenmagazin/julian-nida-ruemelin-zur-corona-krise-100.html

Nida-Rümelin, J., & Weidenfeld, N. (2018). Digitaler Humanismus . Piper.

Pieper, A., & Thurnherr, U. (1998). Angewandte Ethik. Eine Einführung . Beck.

Radisch, I. (2019). Umso schlimmer für die Tatsachen . Von https://www.zeit.de/2019/03/robert-menasse-schriftsteller-fakten-zitate-zuckermayer-medaille-auszeichnung

Regan, T. (2008). Wie man Tierrechte begründet. In U. Wolf (Ed.), Texte zur Tierethik (pp. 33–39). Reclam.

Regan, T. (2014). Von Menschenrechten zu Tierrechten. In F. Schmitz (Ed.), Tierethik (pp. 88–114). Suhrkamp.

Ricken, F. (1998). Allgemeine Ethik . Kohlhammer.

Safranski, R. (1997). Das Böse oder das Drama der Freiheit . Hanser.

SAMW. (2020). Hinweise zur Umsetzung Kapitel 9.3. der SAMW-Richtlinien Intensivmedizinische Massnahmen (2013 ). Von file:///C:/Users/DONMIC~1/AppData/Local/Temp/richtlinien_v2_samw_triage_intensivmedizinische_massnahmen_ressourcenknappheit_ 20200324.pdf

Sandel, M. J. (2019). Gerechtigkeit . Ullstein.

Schneider, H. J. (1994). Einleitung: Ethisches Argumentieren. In H. &. Hastedt (Hrsg.), Ethik. Ein Grundkurs (S. 13–47). Rowohlt.

Singer, P. (2008). Rassismus und Speziesismus. In U. Wolf (Ed.), Texte zur Tierethik (pp. 25–32). Reclam.

Spaemann, R. (1980). Technische Eingriffe in die Natur als Problem der politischen Ethik. In D. Birnbacher (Ed.), Ökologie und Ethik (pp. 180–206). Reclam.

Spaemann, R. (1999). Moralische Grundbegriffe . Beck.

Wolf, U. (2018). Ethik der Mensch-Tier-Beziehung . Klostermann.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Friedrich Alexander Uni, Fortbildungszentrum Hochschullehre FBZHL, Fürth, Bayern, Germany

Friedrich Alexander Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg, Fortbildungszentrum Hochschullehre FBZHL, Fürth, Germany

Michael Cursio

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH, part of Springer Nature

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Jahn, D., Cursio, M. (2023). Ethical Thinking. In: Critical Thinking. Springer VS, Wiesbaden. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-41543-3_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-41543-3_3

Published : 10 December 2023

Publisher Name : Springer VS, Wiesbaden

Print ISBN : 978-3-658-41542-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-658-41543-3

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

A Framework for Ethical Decision Making

- Markkula Center for Applied Ethics

- Ethics Resources

This document is designed as an introduction to thinking ethically. Read more about what the framework can (and cannot) do .

We all have an image of our better selves—of how we are when we act ethically or are “at our best.” We probably also have an image of what an ethical community, an ethical business, an ethical government, or an ethical society should be. Ethics really has to do with all these levels—acting ethically as individuals, creating ethical organizations and governments, and making our society as a whole more ethical in the way it treats everyone.

What is Ethics?

Ethics refers to standards and practices that tell us how human beings ought to act in the many situations in which they find themselves—as friends, parents, children, citizens, businesspeople, professionals, and so on. Ethics is also concerned with our character. It requires knowledge, skills, and habits.

It is helpful to identify what ethics is NOT:

- Ethics is not the same as feelings . Feelings do provide important information for our ethical choices. However, while some people have highly developed habits that make them feel bad when they do something wrong, others feel good even though they are doing something wrong. And, often, our feelings will tell us that it is uncomfortable to do the right thing if it is difficult.

- Ethics is not the same as religion . Many people are not religious but act ethically, and some religious people act unethically. Religious traditions can, however, develop and advocate for high ethical standards, such as the Golden Rule.

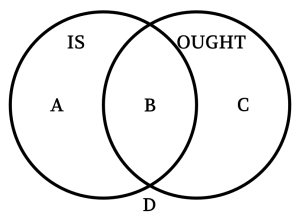

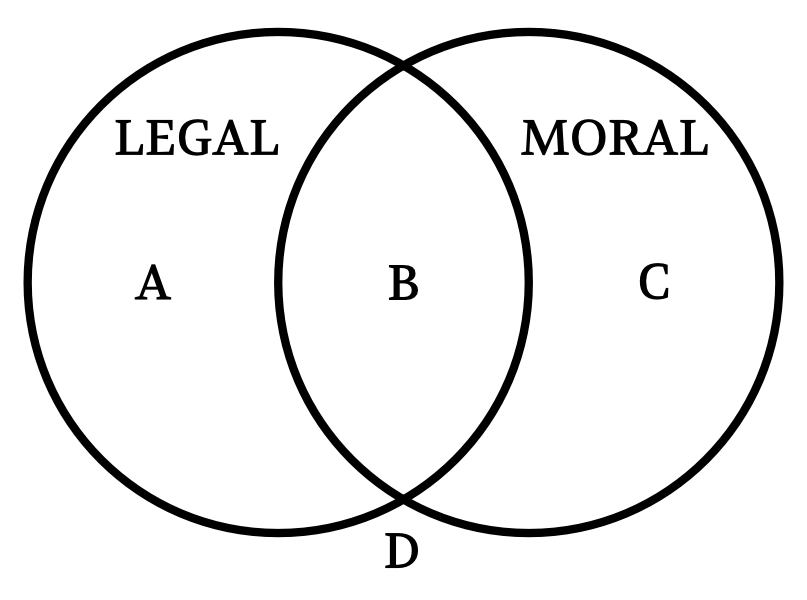

- Ethics is not the same thing as following the law. A good system of law does incorporate many ethical standards, but law can deviate from what is ethical. Law can become ethically corrupt—a function of power alone and designed to serve the interests of narrow groups. Law may also have a difficult time designing or enforcing standards in some important areas and may be slow to address new problems.

- Ethics is not the same as following culturally accepted norms . Cultures can include both ethical and unethical customs, expectations, and behaviors. While assessing norms, it is important to recognize how one’s ethical views can be limited by one’s own cultural perspective or background, alongside being culturally sensitive to others.

- Ethics is not science . Social and natural science can provide important data to help us make better and more informed ethical choices. But science alone does not tell us what we ought to do. Some things may be scientifically or technologically possible and yet unethical to develop and deploy.

Six Ethical Lenses

If our ethical decision-making is not solely based on feelings, religion, law, accepted social practice, or science, then on what basis can we decide between right and wrong, good and bad? Many philosophers, ethicists, and theologians have helped us answer this critical question. They have suggested a variety of different lenses that help us perceive ethical dimensions. Here are six of them:

The Rights Lens

Some suggest that the ethical action is the one that best protects and respects the moral rights of those affected. This approach starts from the belief that humans have a dignity based on their human nature per se or on their ability to choose freely what they do with their lives. On the basis of such dignity, they have a right to be treated as ends in themselves and not merely as means to other ends. The list of moral rights—including the rights to make one's own choices about what kind of life to lead, to be told the truth, not to be injured, to a degree of privacy, and so on—is widely debated; some argue that non-humans have rights, too. Rights are also often understood as implying duties—in particular, the duty to respect others' rights and dignity.

( For further elaboration on the rights lens, please see our essay, “Rights.” )

The Justice Lens

Justice is the idea that each person should be given their due, and what people are due is often interpreted as fair or equal treatment. Equal treatment implies that people should be treated as equals according to some defensible standard such as merit or need, but not necessarily that everyone should be treated in the exact same way in every respect. There are different types of justice that address what people are due in various contexts. These include social justice (structuring the basic institutions of society), distributive justice (distributing benefits and burdens), corrective justice (repairing past injustices), retributive justice (determining how to appropriately punish wrongdoers), and restorative or transformational justice (restoring relationships or transforming social structures as an alternative to criminal punishment).

( For further elaboration on the justice lens, please see our essay, “Justice and Fairness.” )

The Utilitarian Lens

Some ethicists begin by asking, “How will this action impact everyone affected?”—emphasizing the consequences of our actions. Utilitarianism, a results-based approach, says that the ethical action is the one that produces the greatest balance of good over harm for as many stakeholders as possible. It requires an accurate determination of the likelihood of a particular result and its impact. For example, the ethical corporate action, then, is the one that produces the greatest good and does the least harm for all who are affected—customers, employees, shareholders, the community, and the environment. Cost/benefit analysis is another consequentialist approach.

( For further elaboration on the utilitarian lens, please see our essay, “Calculating Consequences.” )

The Common Good Lens

According to the common good approach, life in community is a good in itself and our actions should contribute to that life. This approach suggests that the interlocking relationships of society are the basis of ethical reasoning and that respect and compassion for all others—especially the vulnerable—are requirements of such reasoning. This approach also calls attention to the common conditions that are important to the welfare of everyone—such as clean air and water, a system of laws, effective police and fire departments, health care, a public educational system, or even public recreational areas. Unlike the utilitarian lens, which sums up and aggregates goods for every individual, the common good lens highlights mutual concern for the shared interests of all members of a community.

( For further elaboration on the common good lens, please see our essay, “The Common Good.” )

The Virtue Lens

A very ancient approach to ethics argues that ethical actions ought to be consistent with certain ideal virtues that provide for the full development of our humanity. These virtues are dispositions and habits that enable us to act according to the highest potential of our character and on behalf of values like truth and beauty. Honesty, courage, compassion, generosity, tolerance, love, fidelity, integrity, fairness, self-control, and prudence are all examples of virtues. Virtue ethics asks of any action, “What kind of person will I become if I do this?” or “Is this action consistent with my acting at my best?”

( For further elaboration on the virtue lens, please see our essay, “Ethics and Virtue.” )

The Care Ethics Lens

Care ethics is rooted in relationships and in the need to listen and respond to individuals in their specific circumstances, rather than merely following rules or calculating utility. It privileges the flourishing of embodied individuals in their relationships and values interdependence, not just independence. It relies on empathy to gain a deep appreciation of the interest, feelings, and viewpoints of each stakeholder, employing care, kindness, compassion, generosity, and a concern for others to resolve ethical conflicts. Care ethics holds that options for resolution must account for the relationships, concerns, and feelings of all stakeholders. Focusing on connecting intimate interpersonal duties to societal duties, an ethics of care might counsel, for example, a more holistic approach to public health policy that considers food security, transportation access, fair wages, housing support, and environmental protection alongside physical health.

( For further elaboration on the care ethics lens, please see our essay, “Care Ethics.” )

Using the Lenses

Each of the lenses introduced above helps us determine what standards of behavior and character traits can be considered right and good. There are still problems to be solved, however.

The first problem is that we may not agree on the content of some of these specific lenses. For example, we may not all agree on the same set of human and civil rights. We may not agree on what constitutes the common good. We may not even agree on what is a good and what is a harm.

The second problem is that the different lenses may lead to different answers to the question “What is ethical?” Nonetheless, each one gives us important insights in the process of deciding what is ethical in a particular circumstance.

Making Decisions

Making good ethical decisions requires a trained sensitivity to ethical issues and a practiced method for exploring the ethical aspects of a decision and weighing the considerations that should impact our choice of a course of action. Having a method for ethical decision-making is essential. When practiced regularly, the method becomes so familiar that we work through it automatically without consulting the specific steps.

The more novel and difficult the ethical choice we face, the more we need to rely on discussion and dialogue with others about the dilemma. Only by careful exploration of the problem, aided by the insights and different perspectives of others, can we make good ethical choices in such situations.

The following framework for ethical decision-making is intended to serve as a practical tool for exploring ethical dilemmas and identifying ethical courses of action.

Identify the Ethical Issues

- Could this decision or situation be damaging to someone or to some group, or unevenly beneficial to people? Does this decision involve a choice between a good and bad alternative, or perhaps between two “goods” or between two “bads”?

- Is this issue about more than solely what is legal or what is most efficient? If so, how?

Get the Facts

- What are the relevant facts of the case? What facts are not known? Can I learn more about the situation? Do I know enough to make a decision?

- What individuals and groups have an important stake in the outcome? Are the concerns of some of those individuals or groups more important? Why?

- What are the options for acting? Have all the relevant persons and groups been consulted? Have I identified creative options?

Evaluate Alternative Actions

- Evaluate the options by asking the following questions:

- Which option best respects the rights of all who have a stake? (The Rights Lens)

- Which option treats people fairly, giving them each what they are due? (The Justice Lens)

- Which option will produce the most good and do the least harm for as many stakeholders as possible? (The Utilitarian Lens)

- Which option best serves the community as a whole, not just some members? (The Common Good Lens)

- Which option leads me to act as the sort of person I want to be? (The Virtue Lens)

- Which option appropriately takes into account the relationships, concerns, and feelings of all stakeholders? (The Care Ethics Lens)

Choose an Option for Action and Test It

- After an evaluation using all of these lenses, which option best addresses the situation?

- If I told someone I respect (or a public audience) which option I have chosen, what would they say?

- How can my decision be implemented with the greatest care and attention to the concerns of all stakeholders?

Implement Your Decision and Reflect on the Outcome

- How did my decision turn out, and what have I learned from this specific situation? What (if any) follow-up actions should I take?

This framework for thinking ethically is the product of dialogue and debate at the Markkula Center for Applied Ethics at Santa Clara University. Primary contributors include Manuel Velasquez, Dennis Moberg, Michael J. Meyer, Thomas Shanks, Margaret R. McLean, David DeCosse, Claire André, Kirk O. Hanson, Irina Raicu, and Jonathan Kwan. It was last revised on November 5, 2021.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

10.1: Ethics vs. Morality

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 223916

There’s no standard distinction between the ‘ethical’ and the ‘moral.’ Which are ethical questions? Which are moral questions? Who knows?

I like to think about them the following way:

The ethical (from Greek ethos ) is a really broad category encompassing questions about everything we do. The ethical is about your relationship with yourself (and if you’re a theist about your relationship with God).

The moral (from Latin mores or customs) is a narrower category encompassing only questions about our relations with one another. Moral questions are like the morality of abortion, murder, theft, lying, etc. They’re about how we interact with other agents/actors.

A sub-set of moral questions are political : how should we govern our society? What taxation schemes are fair/just/moral? What is a moral policing strategy? Etc.

On this conception, the ethical encompasses the moral and political because ethical questions are questions about the good life and what we ought to do, whereas moral questions are about what we ought to do to and with one another.

It’s important to note, though, that this isn’t an authoritative way to draw the distinction. There are other ways to do so. In this class, I tend to just use ‘moral’ and ‘ethical’ interchangeably.

Leading in Context

Unleash the Positive Power of Ethical Leadership

How Is Critical Thinking Different From Ethical Thinking?

By Linda Fisher Thornton

Ethical thinking and critical thinking are both important and it helps to understand how we need to use them together to make decisions.

- Critical thinking helps us narrow our choices. Ethical thinking includes values as a filter to guide us to a choice that is ethical.

- Using critical thinking, we may discover an opportunity to exploit a situation for personal gain. It’s ethical thinking that helps us realize it would be unethical to take advantage of that exploit.

Develop An Ethical Mindset Not Just Critical Thinking

Critical thinking can be applied without considering how others will be impacted. This kind of critical thinking is self-interested and myopic.

“Critical thinking varies according to the motivation underlying it. When grounded in selfish motives, it is often manifested in the skillful manipulation of ideas in service of one’s own, or one’s groups’, vested interest.” Defining Critical Thinking, The Foundation For Critical Thinking

Critical thinking informed by ethical values is a powerful leadership tool. Critical thinking that sidesteps ethical values is sometimes used as a weapon.

When we develop leaders, the burden is on us to be sure the mindsets we teach align with ethical thinking. Otherwise we may be helping people use critical thinking to stray beyond the boundaries of ethical business.

Unl eash the Positive Power of Ethical Leadership

© 2019-2024 Leading in Context LLC

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Pingback: Unveiling Ethical Insights: Reflecting on My Business Ethics Class – Atlas-blue.com

- Pingback: The Ethics Of Artificial Intelligence – Surfactants

- Pingback: Five Blogs – 17 May 2019 – 5blogs

Join the Conversation!

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Hughes RG, editor. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2008 Apr.

Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses.

Chapter 6 clinical reasoning, decisionmaking, and action: thinking critically and clinically.

Patricia Benner ; Ronda G. Hughes ; Molly Sutphen .

Affiliations

This chapter examines multiple thinking strategies that are needed for high-quality clinical practice. Clinical reasoning and judgment are examined in relation to other modes of thinking used by clinical nurses in providing quality health care to patients that avoids adverse events and patient harm. The clinician’s ability to provide safe, high-quality care can be dependent upon their ability to reason, think, and judge, which can be limited by lack of experience. The expert performance of nurses is dependent upon continual learning and evaluation of performance.

- Critical Thinking

Nursing education has emphasized critical thinking as an essential nursing skill for more than 50 years. 1 The definitions of critical thinking have evolved over the years. There are several key definitions for critical thinking to consider. The American Philosophical Association (APA) defined critical thinking as purposeful, self-regulatory judgment that uses cognitive tools such as interpretation, analysis, evaluation, inference, and explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations on which judgment is based. 2 A more expansive general definition of critical thinking is

. . . in short, self-directed, self-disciplined, self-monitored, and self-corrective thinking. It presupposes assent to rigorous standards of excellence and mindful command of their use. It entails effective communication and problem solving abilities and a commitment to overcome our native egocentrism and sociocentrism. Every clinician must develop rigorous habits of critical thinking, but they cannot escape completely the situatedness and structures of the clinical traditions and practices in which they must make decisions and act quickly in specific clinical situations. 3

There are three key definitions for nursing, which differ slightly. Bittner and Tobin defined critical thinking as being “influenced by knowledge and experience, using strategies such as reflective thinking as a part of learning to identify the issues and opportunities, and holistically synthesize the information in nursing practice” 4 (p. 268). Scheffer and Rubenfeld 5 expanded on the APA definition for nurses through a consensus process, resulting in the following definition:

Critical thinking in nursing is an essential component of professional accountability and quality nursing care. Critical thinkers in nursing exhibit these habits of the mind: confidence, contextual perspective, creativity, flexibility, inquisitiveness, intellectual integrity, intuition, openmindedness, perseverance, and reflection. Critical thinkers in nursing practice the cognitive skills of analyzing, applying standards, discriminating, information seeking, logical reasoning, predicting, and transforming knowledge 6 (Scheffer & Rubenfeld, p. 357).

The National League for Nursing Accreditation Commission (NLNAC) defined critical thinking as:

the deliberate nonlinear process of collecting, interpreting, analyzing, drawing conclusions about, presenting, and evaluating information that is both factually and belief based. This is demonstrated in nursing by clinical judgment, which includes ethical, diagnostic, and therapeutic dimensions and research 7 (p. 8).

These concepts are furthered by the American Association of Colleges of Nurses’ definition of critical thinking in their Essentials of Baccalaureate Nursing :

Critical thinking underlies independent and interdependent decision making. Critical thinking includes questioning, analysis, synthesis, interpretation, inference, inductive and deductive reasoning, intuition, application, and creativity 8 (p. 9).

Course work or ethical experiences should provide the graduate with the knowledge and skills to:

- Use nursing and other appropriate theories and models, and an appropriate ethical framework;

- Apply research-based knowledge from nursing and the sciences as the basis for practice;

- Use clinical judgment and decision-making skills;

- Engage in self-reflective and collegial dialogue about professional practice;

- Evaluate nursing care outcomes through the acquisition of data and the questioning of inconsistencies, allowing for the revision of actions and goals;

- Engage in creative problem solving 8 (p. 10).

Taken together, these definitions of critical thinking set forth the scope and key elements of thought processes involved in providing clinical care. Exactly how critical thinking is defined will influence how it is taught and to what standard of care nurses will be held accountable.

Professional and regulatory bodies in nursing education have required that critical thinking be central to all nursing curricula, but they have not adequately distinguished critical reflection from ethical, clinical, or even creative thinking for decisionmaking or actions required by the clinician. Other essential modes of thought such as clinical reasoning, evaluation of evidence, creative thinking, or the application of well-established standards of practice—all distinct from critical reflection—have been subsumed under the rubric of critical thinking. In the nursing education literature, clinical reasoning and judgment are often conflated with critical thinking. The accrediting bodies and nursing scholars have included decisionmaking and action-oriented, practical, ethical, and clinical reasoning in the rubric of critical reflection and thinking. One might say that this harmless semantic confusion is corrected by actual practices, except that students need to understand the distinctions between critical reflection and clinical reasoning, and they need to learn to discern when each is better suited, just as students need to also engage in applying standards, evidence-based practices, and creative thinking.

The growing body of research, patient acuity, and complexity of care demand higher-order thinking skills. Critical thinking involves the application of knowledge and experience to identify patient problems and to direct clinical judgments and actions that result in positive patient outcomes. These skills can be cultivated by educators who display the virtues of critical thinking, including independence of thought, intellectual curiosity, courage, humility, empathy, integrity, perseverance, and fair-mindedness. 9

The process of critical thinking is stimulated by integrating the essential knowledge, experiences, and clinical reasoning that support professional practice. The emerging paradigm for clinical thinking and cognition is that it is social and dialogical rather than monological and individual. 10–12 Clinicians pool their wisdom and multiple perspectives, yet some clinical knowledge can be demonstrated only in the situation (e.g., how to suction an extremely fragile patient whose oxygen saturations sink too low). Early warnings of problematic situations are made possible by clinicians comparing their observations to that of other providers. Clinicians form practice communities that create styles of practice, including ways of doing things, communication styles and mechanisms, and shared expectations about performance and expertise of team members.

By holding up critical thinking as a large umbrella for different modes of thinking, students can easily misconstrue the logic and purposes of different modes of thinking. Clinicians and scientists alike need multiple thinking strategies, such as critical thinking, clinical judgment, diagnostic reasoning, deliberative rationality, scientific reasoning, dialogue, argument, creative thinking, and so on. In particular, clinicians need forethought and an ongoing grasp of a patient’s health status and care needs trajectory, which requires an assessment of their own clarity and understanding of the situation at hand, critical reflection, critical reasoning, and clinical judgment.

Critical Reflection, Critical Reasoning, and Judgment

Critical reflection requires that the thinker examine the underlying assumptions and radically question or doubt the validity of arguments, assertions, and even facts of the case. Critical reflective skills are essential for clinicians; however, these skills are not sufficient for the clinician who must decide how to act in particular situations and avoid patient injury. For example, in everyday practice, clinicians cannot afford to critically reflect on the well-established tenets of “normal” or “typical” human circulatory systems when trying to figure out a particular patient’s alterations from that typical, well-grounded understanding that has existed since Harvey’s work in 1628. 13 Yet critical reflection can generate new scientifically based ideas. For example, there is a lack of adequate research on the differences between women’s and men’s circulatory systems and the typical pathophysiology related to heart attacks. Available research is based upon multiple, taken-for-granted starting points about the general nature of the circulatory system. As such, critical reflection may not provide what is needed for a clinician to act in a situation. This idea can be considered reasonable since critical reflective thinking is not sufficient for good clinical reasoning and judgment. The clinician’s development of skillful critical reflection depends upon being taught what to pay attention to, and thus gaining a sense of salience that informs the powers of perceptual grasp. The powers of noticing or perceptual grasp depend upon noticing what is salient and the capacity to respond to the situation.

Critical reflection is a crucial professional skill, but it is not the only reasoning skill or logic clinicians require. The ability to think critically uses reflection, induction, deduction, analysis, challenging assumptions, and evaluation of data and information to guide decisionmaking. 9 , 14 , 15 Critical reasoning is a process whereby knowledge and experience are applied in considering multiple possibilities to achieve the desired goals, 16 while considering the patient’s situation. 14 It is a process where both inductive and deductive cognitive skills are used. 17 Sometimes clinical reasoning is presented as a form of evaluating scientific knowledge, sometimes even as a form of scientific reasoning. Critical thinking is inherent in making sound clinical reasoning. 18

An essential point of tension and confusion exists in practice traditions such as nursing and medicine when clinical reasoning and critical reflection become entangled, because the clinician must have some established bases that are not questioned when engaging in clinical decisions and actions, such as standing orders. The clinician must act in the particular situation and time with the best clinical and scientific knowledge available. The clinician cannot afford to indulge in either ritualistic unexamined knowledge or diagnostic or therapeutic nihilism caused by radical doubt, as in critical reflection, because they must find an intelligent and effective way to think and act in particular clinical situations. Critical reflection skills are essential to assist practitioners to rethink outmoded or even wrong-headed approaches to health care, health promotion, and prevention of illness and complications, especially when new evidence is available. Breakdowns in practice, high failure rates in particular therapies, new diseases, new scientific discoveries, and societal changes call for critical reflection about past assumptions and no-longer-tenable beliefs.

Clinical reasoning stands out as a situated, practice-based form of reasoning that requires a background of scientific and technological research-based knowledge about general cases, more so than any particular instance. It also requires practical ability to discern the relevance of the evidence behind general scientific and technical knowledge and how it applies to a particular patient. In dong so, the clinician considers the patient’s particular clinical trajectory, their concerns and preferences, and their particular vulnerabilities (e.g., having multiple comorbidities) and sensitivities to care interventions (e.g., known drug allergies, other conflicting comorbid conditions, incompatible therapies, and past responses to therapies) when forming clinical decisions or conclusions.

Situated in a practice setting, clinical reasoning occurs within social relationships or situations involving patient, family, community, and a team of health care providers. The expert clinician situates themselves within a nexus of relationships, with concerns that are bounded by the situation. Expert clinical reasoning is socially engaged with the relationships and concerns of those who are affected by the caregiving situation, and when certain circumstances are present, the adverse event. Halpern 19 has called excellent clinical ethical reasoning “emotional reasoning” in that the clinicians have emotional access to the patient/family concerns and their understanding of the particular care needs. Expert clinicians also seek an optimal perceptual grasp, one based on understanding and as undistorted as possible, based on an attuned emotional engagement and expert clinical knowledge. 19 , 20

Clergy educators 21 and nursing and medical educators have begun to recognize the wisdom of broadening their narrow vision of rationality beyond simple rational calculation (exemplified by cost-benefit analysis) to reconsider the need for character development—including emotional engagement, perception, habits of thought, and skill acquisition—as essential to the development of expert clinical reasoning, judgment, and action. 10 , 22–24 Practitioners of engineering, law, medicine, and nursing, like the clergy, have to develop a place to stand in their discipline’s tradition of knowledge and science in order to recognize and evaluate salient evidence in the moment. Diagnostic confusion and disciplinary nihilism are both threats to the clinician’s ability to act in particular situations. However, the practice and practitioners will not be self-improving and vital if they cannot engage in critical reflection on what is not of value, what is outmoded, and what does not work. As evidence evolves and expands, so too must clinical thought.

Clinical judgment requires clinical reasoning across time about the particular, and because of the relevance of this immediate historical unfolding, clinical reasoning can be very different from the scientific reasoning used to formulate, conduct, and assess clinical experiments. While scientific reasoning is also socially embedded in a nexus of social relationships and concerns, the goal of detached, critical objectivity used to conduct scientific experiments minimizes the interactive influence of the research on the experiment once it has begun. Scientific research in the natural and clinical sciences typically uses formal criteria to develop “yes” and “no” judgments at prespecified times. The scientist is always situated in past and immediate scientific history, preferring to evaluate static and predetermined points in time (e.g., snapshot reasoning), in contrast to a clinician who must always reason about transitions over time. 25 , 26

Techne and Phronesis

Distinctions between the mere scientific making of things and practice was first explored by Aristotle as distinctions between techne and phronesis. 27 Learning to be a good practitioner requires developing the requisite moral imagination for good practice. If, for example, patients exercise their rights and refuse treatments, practitioners are required to have the moral imagination to understand the probable basis for the patient’s refusal. For example, was the refusal based upon catastrophic thinking, unrealistic fears, misunderstanding, or even clinical depression?

Techne, as defined by Aristotle, encompasses the notion of formation of character and habitus 28 as embodied beings. In Aristotle’s terms, techne refers to the making of things or producing outcomes. 11 Joseph Dunne defines techne as “the activity of producing outcomes,” and it “is governed by a means-ends rationality where the maker or producer governs the thing or outcomes produced or made through gaining mastery over the means of producing the outcomes, to the point of being able to separate means and ends” 11 (p. 54). While some aspects of medical and nursing practice fall into the category of techne, much of nursing and medical practice falls outside means-ends rationality and must be governed by concern for doing good or what is best for the patient in particular circumstances, where being in a relationship and discerning particular human concerns at stake guide action.

Phronesis, in contrast to techne, includes reasoning about the particular, across time, through changes or transitions in the patient’s and/or the clinician’s understanding. As noted by Dunne, phronesis is “characterized at least as much by a perceptiveness with regard to concrete particulars as by a knowledge of universal principles” 11 (p. 273). This type of practical reasoning often takes the form of puzzle solving or the evaluation of immediate past “hot” history of the patient’s situation. Such a particular clinical situation is necessarily particular, even though many commonalities and similarities with other disease syndromes can be recognized through signs and symptoms and laboratory tests. 11 , 29 , 30 Pointing to knowledge embedded in a practice makes no claim for infallibility or “correctness.” Individual practitioners can be mistaken in their judgments because practices such as medicine and nursing are inherently underdetermined. 31

While phronetic knowledge must remain open to correction and improvement, real events, and consequences, it cannot consistently transcend the institutional setting’s capacities and supports for good practice. Phronesis is also dependent on ongoing experiential learning of the practitioner, where knowledge is refined, corrected, or refuted. The Western tradition, with the notable exception of Aristotle, valued knowledge that could be made universal and devalued practical know-how and experiential learning. Descartes codified this preference for formal logic and rational calculation.

Aristotle recognized that when knowledge is underdetermined, changeable, and particular, it cannot be turned into the universal or standardized. It must be perceived, discerned, and judged, all of which require experiential learning. In nursing and medicine, perceptual acuity in physical assessment and clinical judgment (i.e., reasoning across time about changes in the particular patient or the clinician’s understanding of the patient’s condition) fall into the Greek Aristotelian category of phronesis. Dewey 32 sought to rescue knowledge gained by practical activity in the world. He identified three flaws in the understanding of experience in Greek philosophy: (1) empirical knowing is the opposite of experience with science; (2) practice is reduced to techne or the application of rational thought or technique; and (3) action and skilled know-how are considered temporary and capricious as compared to reason, which the Greeks considered as ultimate reality.

In practice, nursing and medicine require both techne and phronesis. The clinician standardizes and routinizes what can be standardized and routinized, as exemplified by standardized blood pressure measurements, diagnoses, and even charting about the patient’s condition and treatment. 27 Procedural and scientific knowledge can often be formalized and standardized (e.g., practice guidelines), or at least made explicit and certain in practice, except for the necessary timing and adjustments made for particular patients. 11 , 22

Rational calculations available to techne—population trends and statistics, algorithms—are created as decision support structures and can improve accuracy when used as a stance of inquiry in making clinical judgments about particular patients. Aggregated evidence from clinical trials and ongoing working knowledge of pathophysiology, biochemistry, and genomics are essential. In addition, the skills of phronesis (clinical judgment that reasons across time, taking into account the transitions of the particular patient/family/community and transitions in the clinician’s understanding of the clinical situation) will be required for nursing, medicine, or any helping profession.

Thinking Critically

Being able to think critically enables nurses to meet the needs of patients within their context and considering their preferences; meet the needs of patients within the context of uncertainty; consider alternatives, resulting in higher-quality care; 33 and think reflectively, rather than simply accepting statements and performing tasks without significant understanding and evaluation. 34 Skillful practitioners can think critically because they have the following cognitive skills: information seeking, discriminating, analyzing, transforming knowledge, predicating, applying standards, and logical reasoning. 5 One’s ability to think critically can be affected by age, length of education (e.g., an associate vs. a baccalaureate decree in nursing), and completion of philosophy or logic subjects. 35–37 The skillful practitioner can think critically because of having the following characteristics: motivation, perseverance, fair-mindedness, and deliberate and careful attention to thinking. 5 , 9

Thinking critically implies that one has a knowledge base from which to reason and the ability to analyze and evaluate evidence. 38 Knowledge can be manifest by the logic and rational implications of decisionmaking. Clinical decisionmaking is particularly influenced by interpersonal relationships with colleagues, 39 patient conditions, availability of resources, 40 knowledge, and experience. 41 Of these, experience has been shown to enhance nurses’ abilities to make quick decisions 42 and fewer decision errors, 43 support the identification of salient cues, and foster the recognition and action on patterns of information. 44 , 45

Clinicians must develop the character and relational skills that enable them to perceive and understand their patient’s needs and concerns. This requires accurate interpretation of patient data that is relevant to the specific patient and situation. In nursing, this formation of moral agency focuses on learning to be responsible in particular ways demanded by the practice, and to pay attention and intelligently discern changes in patients’ concerns and/or clinical condition that require action on the part of the nurse or other health care workers to avert potential compromises to quality care.

Formation of the clinician’s character, skills, and habits are developed in schools and particular practice communities within a larger practice tradition. As Dunne notes,

A practice is not just a surface on which one can display instant virtuosity. It grounds one in a tradition that has been formed through an elaborate development and that exists at any juncture only in the dispositions (slowly and perhaps painfully acquired) of its recognized practitioners. The question may of course be asked whether there are any such practices in the contemporary world, whether the wholesale encroachment of Technique has not obliterated them—and whether this is not the whole point of MacIntyre’s recipe of withdrawal, as well as of the post-modern story of dispossession 11 (p. 378).

Clearly Dunne is engaging in critical reflection about the conditions for developing character, skills, and habits for skillful and ethical comportment of practitioners, as well as to act as moral agents for patients so that they and their families receive safe, effective, and compassionate care.

Professional socialization or professional values, while necessary, do not adequately address character and skill formation that transform the way the practitioner exists in his or her world, what the practitioner is capable of noticing and responding to, based upon well-established patterns of emotional responses, skills, dispositions to act, and the skills to respond, decide, and act. 46 The need for character and skill formation of the clinician is what makes a practice stand out from a mere technical, repetitious manufacturing process. 11 , 30 , 47

In nursing and medicine, many have questioned whether current health care institutions are designed to promote or hinder enlightened, compassionate practice, or whether they have deteriorated into commercial institutional models that focus primarily on efficiency and profit. MacIntyre points out the links between the ongoing development and improvement of practice traditions and the institutions that house them:

Lack of justice, lack of truthfulness, lack of courage, lack of the relevant intellectual virtues—these corrupt traditions, just as they do those institutions and practices which derive their life from the traditions of which they are the contemporary embodiments. To recognize this is of course also to recognize the existence of an additional virtue, one whose importance is perhaps most obvious when it is least present, the virtue of having an adequate sense of the traditions to which one belongs or which confront one. This virtue is not to be confused with any form of conservative antiquarianism; I am not praising those who choose the conventional conservative role of laudator temporis acti. It is rather the case that an adequate sense of tradition manifests itself in a grasp of those future possibilities which the past has made available to the present. Living traditions, just because they continue a not-yet-completed narrative, confront a future whose determinate and determinable character, so far as it possesses any, derives from the past 30 (p. 207).

It would be impossible to capture all the situated and distributed knowledge outside of actual practice situations and particular patients. Simulations are powerful as teaching tools to enable nurses’ ability to think critically because they give students the opportunity to practice in a simplified environment. However, students can be limited in their inability to convey underdetermined situations where much of the information is based on perceptions of many aspects of the patient and changes that have occurred over time. Simulations cannot have the sub-cultures formed in practice settings that set the social mood of trust, distrust, competency, limited resources, or other forms of situated possibilities.

One of the hallmark studies in nursing providing keen insight into understanding the influence of experience was a qualitative study of adult, pediatric, and neonatal intensive care unit (ICU) nurses, where the nurses were clustered into advanced beginner, intermediate, and expert level of practice categories. The advanced beginner (having up to 6 months of work experience) used procedures and protocols to determine which clinical actions were needed. When confronted with a complex patient situation, the advanced beginner felt their practice was unsafe because of a knowledge deficit or because of a knowledge application confusion. The transition from advanced beginners to competent practitioners began when they first had experience with actual clinical situations and could benefit from the knowledge gained from the mistakes of their colleagues. Competent nurses continuously questioned what they saw and heard, feeling an obligation to know more about clinical situations. In doing do, they moved from only using care plans and following the physicians’ orders to analyzing and interpreting patient situations. Beyond that, the proficient nurse acknowledged the changing relevance of clinical situations requiring action beyond what was planned or anticipated. The proficient nurse learned to acknowledge the changing needs of patient care and situation, and could organize interventions “by the situation as it unfolds rather than by preset goals 48 (p. 24). Both competent and proficient nurses (that is, intermediate level of practice) had at least two years of ICU experience. 48 Finally, the expert nurse had a more fully developed grasp of a clinical situation, a sense of confidence in what is known about the situation, and could differentiate the precise clinical problem in little time. 48

Expertise is acquired through professional experience and is indicative of a nurse who has moved beyond mere proficiency. As Gadamer 29 points out, experience involves a turning around of preconceived notions, preunderstandings, and extends or adds nuances to understanding. Dewey 49 notes that experience requires a prepared “creature” and an enriched environment. The opportunity to reflect and narrate one’s experiential learning can clarify, extend, or even refute experiential learning.

Experiential learning requires time and nurturing, but time alone does not ensure experiential learning. Aristotle linked experiential learning to the development of character and moral sensitivities of a person learning a practice. 50 New nurses/new graduates have limited work experience and must experience continuing learning until they have reached an acceptable level of performance. 51 After that, further improvements are not predictable, and years of experience are an inadequate predictor of expertise. 52

The most effective knower and developer of practical knowledge creates an ongoing dialogue and connection between lessons of the day and experiential learning over time. Gadamer, in a late life interview, highlighted the open-endedness and ongoing nature of experiential learning in the following interview response:

Being experienced does not mean that one now knows something once and for all and becomes rigid in this knowledge; rather, one becomes more open to new experiences. A person who is experienced is undogmatic. Experience has the effect of freeing one to be open to new experience … In our experience we bring nothing to a close; we are constantly learning new things from our experience … this I call the interminability of all experience 32 (p. 403).

Practical endeavor, supported by scientific knowledge, requires experiential learning, the development of skilled know-how, and perceptual acuity in order to make the scientific knowledge relevant to the situation. Clinical perceptual and skilled know-how helps the practitioner discern when particular scientific findings might be relevant. 53

Often experience and knowledge, confirmed by experimentation, are treated as oppositions, an either-or choice. However, in practice it is readily acknowledged that experiential knowledge fuels scientific investigation, and scientific investigation fuels further experiential learning. Experiential learning from particular clinical cases can help the clinician recognize future similar cases and fuel new scientific questions and study. For example, less experienced nurses—and it could be argued experienced as well—can use nursing diagnoses practice guidelines as part of their professional advancement. Guidelines are used to reflect their interpretation of patients’ needs, responses, and situation, 54 a process that requires critical thinking and decisionmaking. 55 , 56 Using guidelines also reflects one’s problem identification and problem-solving abilities. 56 Conversely, the ability to proficiently conduct a series of tasks without nursing diagnoses is the hallmark of expertise. 39 , 57

Experience precedes expertise. As expertise develops from experience and gaining knowledge and transitions to the proficiency stage, the nurses’ thinking moves from steps and procedures (i.e., task-oriented care) toward “chunks” or patterns 39 (i.e., patient-specific care). In doing so, the nurse thinks reflectively, rather than merely accepting statements and performing procedures without significant understanding and evaluation. 34 Expert nurses do not rely on rules and logical thought processes in problem-solving and decisionmaking. 39 Instead, they use abstract principles, can see the situation as a complex whole, perceive situations comprehensively, and can be fully involved in the situation. 48 Expert nurses can perform high-level care without conscious awareness of the knowledge they are using, 39 , 58 and they are able to provide that care with flexibility and speed. Through a combination of knowledge and skills gained from a range of theoretical and experiential sources, expert nurses also provide holistic care. 39 Thus, the best care comes from the combination of theoretical, tacit, and experiential knowledge. 59 , 60

Experts are thought to eventually develop the ability to intuitively know what to do and to quickly recognize critical aspects of the situation. 22 Some have proposed that expert nurses provide high-quality patient care, 61 , 62 but that is not consistently documented—particularly in consideration of patient outcomes—and a full understanding between the differential impact of care rendered by an “expert” nurse is not fully understood. In fact, several studies have found that length of professional experience is often unrelated and even negatively related to performance measures and outcomes. 63 , 64

In a review of the literature on expertise in nursing, Ericsson and colleagues 65 found that focusing on challenging, less-frequent situations would reveal individual performance differences on tasks that require speed and flexibility, such as that experienced during a code or an adverse event. Superior performance was associated with extensive training and immediate feedback about outcomes, which can be obtained through continual training, simulation, and processes such as root-cause analysis following an adverse event. Therefore, efforts to improve performance benefited from continual monitoring, planning, and retrospective evaluation. Even then, the nurse’s ability to perform as an expert is dependent upon their ability to use intuition or insights gained through interactions with patients. 39

Intuition and Perception

Intuition is the instant understanding of knowledge without evidence of sensible thought. 66 According to Young, 67 intuition in clinical practice is a process whereby the nurse recognizes something about a patient that is difficult to verbalize. Intuition is characterized by factual knowledge, “immediate possession of knowledge, and knowledge independent of the linear reasoning process” 68 (p. 23). When intuition is used, one filters information initially triggered by the imagination, leading to the integration of all knowledge and information to problem solve. 69 Clinicians use their interactions with patients and intuition, drawing on tacit or experiential knowledge, 70 , 71 to apply the correct knowledge to make the correct decisions to address patient needs. Yet there is a “conflated belief in the nurses’ ability to know what is best for the patient” 72 (p. 251) because the nurses’ and patients’ identification of the patients’ needs can vary. 73

A review of research and rhetoric involving intuition by King and Appleton 62 found that all nurses, including students, used intuition (i.e., gut feelings). They found evidence, predominately in critical care units, that intuition was triggered in response to knowledge and as a trigger for action and/or reflection with a direct bearing on the analytical process involved in patient care. The challenge for nurses was that rigid adherence to checklists, guidelines, and standardized documentation, 62 ignored the benefits of intuition. This view was furthered by Rew and Barrow 68 , 74 in their reviews of the literature, where they found that intuition was imperative to complex decisionmaking, 68 difficult to measure and assess in a quantitative manner, and was not linked to physiologic measures. 74

Intuition is a way of explaining professional expertise. 75 Expert nurses rely on their intuitive judgment that has been developed over time. 39 , 76 Intuition is an informal, nonanalytically based, unstructured, deliberate calculation that facilitates problem solving, 77 a process of arriving at salient conclusions based on relatively small amounts of knowledge and/or information. 78 Experts can have rapid insight into a situation by using intuition to recognize patterns and similarities, achieve commonsense understanding, and sense the salient information combined with deliberative rationality. 10 Intuitive recognition of similarities and commonalities between patients are often the first diagnostic clue or early warning, which must then be followed up with critical evaluation of evidence among the competing conditions. This situation calls for intuitive judgment that can distinguish “expert human judgment from the decisions” made by a novice 79 (p. 23).

Shaw 80 equates intuition with direct perception. Direct perception is dependent upon being able to detect complex patterns and relationships that one has learned through experience are important. Recognizing these patterns and relationships generally occurs rapidly and is complex, making it difficult to articulate or describe. Perceptual skills, like those of the expert nurse, are essential to recognizing current and changing clinical conditions. Perception requires attentiveness and the development of a sense of what is salient. Often in nursing and medicine, means and ends are fused, as is the case for a “good enough” birth experience and a peaceful death.

- Applying Practice Evidence

Research continues to find that using evidence-based guidelines in practice, informed through research evidence, improves patients’ outcomes. 81–83 Research-based guidelines are intended to provide guidance for specific areas of health care delivery. 84 The clinician—both the novice and expert—is expected to use the best available evidence for the most efficacious therapies and interventions in particular instances, to ensure the highest-quality care, especially when deviations from the evidence-based norm may heighten risks to patient safety. Otherwise, if nursing and medicine were exact sciences, or consisted only of techne, then a 1:1 relationship could be established between results of aggregated evidence-based research and the best path for all patients.

Evaluating Evidence

Before research should be used in practice, it must be evaluated. There are many complexities and nuances in evaluating the research evidence for clinical practice. Evaluation of research behind evidence-based medicine requires critical thinking and good clinical judgment. Sometimes the research findings are mixed or even conflicting. As such, the validity, reliability, and generalizability of available research are fundamental to evaluating whether evidence can be applied in practice. To do so, clinicians must select the best scientific evidence relevant to particular patients—a complex process that involves intuition to apply the evidence. Critical thinking is required for evaluating the best available scientific evidence for the treatment and care of a particular patient.

Good clinical judgment is required to select the most relevant research evidence. The best clinical judgment, that is, reasoning across time about the particular patient through changes in the patient’s concerns and condition and/or the clinician’s understanding, are also required. This type of judgment requires clinicians to make careful observations and evaluations of the patient over time, as well as know the patient’s concerns and social circumstances. To evolve to this level of judgment, additional education beyond clinical preparation if often required.

Sources of Evidence

Evidence that can be used in clinical practice has different sources and can be derived from research, patient’s preferences, and work-related experience. 85 , 86 Nurses have been found to obtain evidence from experienced colleagues believed to have clinical expertise and research-based knowledge 87 as well as other sources.

For many years now, randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have often been considered the best standard for evaluating clinical practice. Yet, unless the common threats to the validity (e.g., representativeness of the study population) and reliability (e.g., consistency in interventions and responses of study participants) of RCTs are addressed, the meaningfulness and generalizability of the study outcomes are very limited. Relevant patient populations may be excluded, such as women, children, minorities, the elderly, and patients with multiple chronic illnesses. The dropout rate of the trial may confound the results. And it is easier to get positive results published than it is to get negative results published. Thus, RCTs are generalizable (i.e., applicable) only to the population studied—which may not reflect the needs of the patient under the clinicians care. In instances such as these, clinicians need to also consider applied research using prospective or retrospective populations with case control to guide decisionmaking, yet this too requires critical thinking and good clinical judgment.

Another source of available evidence may come from the gold standard of aggregated systematic evaluation of clinical trial outcomes for the therapy and clinical condition in question, be generated by basic and clinical science relevant to the patient’s particular pathophysiology or care need situation, or stem from personal clinical experience. The clinician then takes all of the available evidence and considers the particular patient’s known clinical responses to past therapies, their clinical condition and history, the progression or stages of the patient’s illness and recovery, and available resources.