Is Text Messaging Ruining English?

With every generation come cries that teenagers are destroying the language with their newfangled slang. The current grievance harps on the way casual language used in texts and instant messages inhibits kids from understanding how to write and speak “properly.” While amateur language lovers might think this argument makes sense, experts say this is not at all the case. In fact, linguists say teenagers, far from destroying English, are innovating and enriching the language.

First of all, abbreviations like haha , lol , omg , brb , and btw are more infrequent than you might imagine, according to a 2008 paper by Sali A. Tagliamonte and Derek Denis . Of course, 2008 is a long time ago in terms of digital fluency, but the findings of the study are nevertheless fascinating. Looking at IM conversations of Toronto-based teenagers, Tagliamonte found that “the use of short forms, abbreviations, and emotional language is infinitesimally small.” These sorts of stereotypical markers of teen language accounted for only 3 percent of Tagliamonte’s data. Perhaps one of her most interesting findings is that older teens start to outgrow the abbreviation lol , opting for the more mature haha . Tagliamonte’s 16-year-old daughter told her, “I used to use lol when I was a kid.”

Tagliamonte, who now is exploring language development in texting as well as instant messaging, argues that these forms of communication are a cultivated mix of formal and informal language and that these mediums are “on the forefront of change.” In an article published in May of this year, Tagliamonte concludes that “students showed that they knew where to use proper English.” For example, a student might not start sentences with capital letters in IMs and text messages, but still understands to do this in formal papers. Tagliamonte believes that this kind of natural blending of conversational registers employed by teens would not be possible without a sophisticated understanding of both formal and informal language.

It was once trendy to try to speak like people wrote, and now it’s the other way around. For the first time in history, we can write quickly enough to capture qualities of spoken language in our writing, and teens are skillfully doing just that. John McWhorter’s 2013 TED Talk “ Txting is killing language. JK!!! ” further supports the idea that teens are language innovators. He believes their creative development of the English language should be not mocked, but studied, calling texting “an expansion of [young people’s] linguistic repertoire.” He singles out the subtle communication prowess of lol . Teens are using it in non-funny situations, and its meaning has expanded beyond just “laugh out loud.” Now it can be used as a marker of empathy and tone, something often lacking in written communication. This is an enhancement–not a perversion–of language. There’s also evidence to suggest that lol sometimes carries a similar meaning to wtf (and furthermore, the abbreviation wtf is more functional and sophisticated than it seems).

Teens aren’t the only ones opting for abbreviations in written communication. The first citation of OMG in the Oxford English Dictionary is from a 1917 letter from the British admiral John Arbuthnot Fisher to none other than Winston Churchill. He writes, “I hear that a new order of Knighthood is on the tapis–O.M.G. (Oh! My God!)–Shower it on the Admiralty!!” Clearly, to give young people all the credit for spreading new abbreviations would be shortsighted, though this letter does bring up the question of where Admiral John Fisher first encountered OMG . Perhaps he picked up this colorful expression from his grandchildren.

Current Events

Science & Technology

Trending Words

Language Stories

Hobbies & Passions

[ joo-b uh - ley -sh uh n ]

- By clicking "Sign Up", you are accepting Dictionary.com Terms & Conditions and Privacy policies.

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Is Text Messaging Destroying the English Language? A Reflective Essay on Texting and English

- Categories : Help with english grammar & vocabulary

- Tags : Homework help & study guides

The Concern

There is an increasing concern that the birth of a heavily abbreviated text messaging language could bring about severe problems for the English language in the near future. One could argue that such fears are founded upon mere parochialism among the middle class, yet the evidence to suggest that text language is having a detrimental impact upon English is highly compelling.

Journalists across the globe have condemned the casual usage of text language in formal mediums such as emails, yet the world only seems to have recently started to take notice. Could it be that the prevalence of text language is leading not only to poor spelling but also to the death of the English language as we know it?

The Death of Grammar?

It is a recognized fact, of course, that text language can be a quick and efficient method of communicating with one another in an informal environment. Abbreviations such as ‘tbh’ instead of ‘to be honest or ‘u’ instead of ‘you’ are certainly practical ones in the hectic lifestyles of the denizens of the twenty-first century. There simply isn’t the time to write messages in full, many will argue, yet it is feared that these lazy spelling forms are gradually penetrating the official English language.

According to Job Bank USA, numerous employers have complained of the sheer volume of job applications they receive written in text language [1]. In particular they note that many applicants have a tendency to speak informally and use text message abbreviations, giving the impression that they are corresponding with an old friend rather than a potential employer. Such prospective applicants seem therefore poorly educated, lazy, and unprofessional. Needless to say, in most cases such applications are thrown in the bin and never thought of again.

Yet the U.K.’s online Daily Mail [2] claimed in an article that this casual, lazy usage of text language outside of the world of mobile phones is becoming something of a contagious disease. Phrases such as ‘lol’ and ‘k’ (meaning ‘laugh out loud’ and ‘okay’ respectively) are being used increasingly in speech and in email correspondence. The result is that many employees and prospective employees appear highly unprofessional in the work place, particularly when corresponding with their superiors.

Optimistic Research

However, despite the issues in and out of the workplace already created by text language, some researchers claim that in reality one need have little to worry about. For example, Kate Baggot writes in the MIT-published website Technology Review [3] that text language and the mediums through which it is employed (instant messengers, Facebook, cell phones) are encouraging literacy among the younger generation: ‘’There is simply much more pressure to know how to read.’’ Some conservative consumers may find this to be an overly trite or optimistic viewpoint, yet one cannot deny that these text language mediums have attracted droves of youngsters to reading and writing at an early age.

English Will Not Yield Easily

Other than the concerns being raised by employers across the globe, the long-term damage that text language could inflict upon English remains for the most part yet to be seen. It is, however, undeniable that the presence of text language, for all its minor benefits, is leading to a more lazy approach to correspondence, especially among younger generations. Fortunately there is no shortage of defenders of the English language–and not only in the UK and the US. Many teachers, journalists, and employers are anxious to maintain its integrity. Those tempted to slip into text language on a regular basis must bear in mind that such culture warriors are very much aware of its presence and all the more likely to chastise those who employ it inappropriately .

- Codesman, Diane. Job Bank USA: https://www.jobbankusa.com/News/Employment/text _language_harms_employment_chances.html

- Clark, Laura. Online Mail. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1094174/Two-thirds-teachers-allow-children-use-slang-text-message-speak-school-tests.html

- Baggot, Kate. Technology Review. Literacy and Text Messaging: https://www.technologyreview.com/biztech/17927/

Texting and the English Language Essay (Critical Writing)

Introduction.

This critique presents the analysis of the issues proposed by Humphrys in order to try to assess whether the text messages destroy the English language.

The article “I h8 txt msgs: How texting is wrecking our language”, is an article written by Humphrys (2007), and it provides the discussion of the sidelining of the English dictionary in favor of a new language. The main point proposed by the article is that the influx of technology has destroyed the uses of the English language through the introduction of the text message service.

The article explains the removal of the hyphenated word in the Oxford English dictionary, a fact that seems to imply that the population does not have time to press the hyphen key in the computer. The author then explains that texting destroys the English language by introducing fashion to writing.

The article explains the time factor as a reason for shortening writing styles, and the influx of the text message phenomenon into normal lives. The author describes the issue of hyphenation of words in the dictionary, and gives two main reasons. The reasons proposed by the author are the ones that follow: time is a factor, but the influx of the text message is the main factor. The introduction of the text message ensures that even old population is forced to text to avoid ridicule from the young generation.

The issue of text messaging has reduced most of the words in the English dictionary. This is because texting has become common for all individuals, and they use it to write shortened versions of the words they would like to deliver from the dictionary. Therefore, this process ensures that dictionary becomes useless. According to Humphrys, the issue of shortening text messages is becoming popular due to the influx of texters in the world.

The author proposes that the issue of text messages interferes with the structure of English messages, rapes the language, destroys punctuation, destroys vocabulary and messes sentence structure. Therefore, this critique presents the analysis of the issues proposed by Humphrys in order to try to assess whether the text messages destroy the English language.

The first issue proposed by the author is the fact that texting is a new phenomenon that has become so common that people who do not text are ridiculed. For example, the author states that the youth will consider him a “grandfather” (Humphrys, 2007) if he does not text.

Therefore, the author states that to text is important for nearly everyone in the world, a factor meaning that people will neglect conventional language writing skills when composing text messages. The result is that people will form their own new language to replace the language that they have used to when writing.

The other point that the author puts forward is that the economy of texting reduces the instances in which individuals make calls (Humphrys, 2007). The author supports this point by stating that some voice calls are irritating for the receivers; the caller leaves long and rambling text messages in the answering machine.

This point indicates that the author is irritated by the calling phenomenon, a fact that necessitates texting. The age of the receivers and texters is also important. Many people, regardless of their age, will prefer to text in order to avoid the tedious and costly nature of making voice calls.

Texting allows people to skip some words that they would have used to when speaking English language, because of the use of smileys in the texting language (Humphrys, 2007). The author states that the history of the smiles, from the first smileys that included the gloomy and smiley face, to the current crop of smiles that have grown, includes 16 pages of smileys.

The author states that smiles have reached an instant where it is impossible to type the colon, dash, and bracket without forming a smiley face. The use of smiles, in one way, have served to destroy the English language by introducing obscure ways of expression, a texter can now express emotions without writing out the whole word.

The grotesque abbreviations, that have plagued the English language, also serve to destroy the English language (Humphrys, 2007). The number of abbreviations has increased in recent years to an extent that abbreviations have evolved to obscure meanings. Texting has increased to the extent that abbreviations have to be understood before being written.

Therefore, the author states that abbreviations destroy the whole point of texting, for example, some abbreviations lose meaning due to their complexity. The abbreviation ’IMHO U R GR8’ (Humphrys, 2007), which means ‘In my humble opinion you are great,’ is a factor that destroys the fact of texting.

In defense of the texting phenomenon, the author states that times are continually evolving, therefore, the texting phenomenon should be universally accepted (Humphrys, 2007). The introduction of e-mail services also serve to interfere with the structure of the English language because of the wrong use of grammar when composing e-mails.

In the past, mails were sent by post, therefore, the mail was written in a conventional grammatical ways. However, with the introduction of the e-mail, most writers find themselves slipping into sloppy writing habits, a fact that means that the language is destroyed (Humphrys, 2007).

Some examples of sloppy writing habits include lack of proper punctuation and diction when writing. In conclusion, it can be seen that the author has a genuine case for hating the texting phenomena; texting destroys the structure of the language, and makes an individual lose his/her language skills.

Humphrys, J. (2007). I h8 txt msgs: How texting is wrecking our language. Dailymail. Retrieved from: < https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-483511/I-h8-txt-msgs-How-texting-wrecking-language.html >

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, December 16). Texting and the English Language. https://ivypanda.com/essays/texting-and-the-english-language/

"Texting and the English Language." IvyPanda , 16 Dec. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/texting-and-the-english-language/.

IvyPanda . (2023) 'Texting and the English Language'. 16 December.

IvyPanda . 2023. "Texting and the English Language." December 16, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/texting-and-the-english-language/.

1. IvyPanda . "Texting and the English Language." December 16, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/texting-and-the-english-language/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Texting and the English Language." December 16, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/texting-and-the-english-language/.

- Logographic Writing System and Emoji Language

- Medical Terminology Abbreviations

- Impact of Language on the Internet

- Use of Abbreviations in the Healthcare Field

- Texting's Importance for the Society

- Texting Effects on Students Academic Performance

- Mobile Culture: Texting Effects on Teenagers

- Medical Abbreviations in Medical Documentations

- Formal Written English is disappearing

- Drunk Driving vs. Texting While Driving

- The Benefits of Being Bilingual in a Global Society

- The Course of English for Special Purposes

- “Sexism in English: Embodiment and Language”

- Written as Spoken Language

- Language Accommodation

- Accessibility & Inclusivity

- Breaking News

- International

- Clubs & Orgs

- Humans of SB

- In Memoriam

- Santa Barbara

- Top Features

- Arts & Culture

- Film & TV

- Local Artists

- Local Musicians

- Student Art

- Theater & Dance

- Top A&E

- App Reviews

- Environment

- Nature of UCSB

- Nature of IV

- Top Science & Tech

- Campus Comment

- Letters to the Editor

- Meet Your Neighbor

- Top Opinions

- Illustrations

- Editorial Board

Earth Day Isla Vista – Celebrating Through Music, Nature, and Fun

In photos: men’s basketball: gauchos vs uc davis, art as a weapon against invasion – film reminds us of…, opportunity for all uc office of the president yet to make…, the top boba places in isla vista – a journey into…, getting kozy: isla vista’s newest coffee shop, a call for natural sustainability: the story and mission of the…, tasa night market 2023: fostering community and featuring budding clubs at…, in photos – daedalum luminarium, an art installation, creating characters we love: the screenwriting process in our flag means…, indigo de souza and the best-case anticlimax, a spectrum of songs: ucsb’s college of creative studies set to…, nature in i.v. – black mold, southern california is in super bloom, from love to likes: social media’s role in relationships, the gloom continues: a gray may, the rise of ai girlfriends: connecting with desires and discussing controversy,…, letter to the editor: dining hall laborers have had enough, do…, is studying abroad worth it for a ucsb student, workers at ucsb spotlight: being a writing tutor for clas, omg is txting ruining #english .

Nardin Sarkis Staff Writer Illustration by Carrie Ding, Staff Illustrator

We have all heard it before—be it from our grandparents, professors, or Time magazine covers—that texting abbreviations are killing the English language. While reflecting on the addition of lol , brb , and selfie to the Oxford English Dictionary in recent years understandably feels unsettling, texting lingo shouldn’t be seen as a corruption of the English language, but rather an evolution of it.

The new millennium’s debate over streamlining language isn’t the first time people have complained about the changing nature of language. Shakespeare would have scoffed at Victorian English speakers’ “distorted language” just as they were angered by American “bastardization” of words like “center” instead of centre . Ironic that the very language used to criticize vernacular abbreviations was at one time itself the source of controversy.

Many academics have also voiced concern over the constraints technology places on the English language. While it is true that technological modes of communication shorten and quicken conversation, most of the time it is simply streamlining the process. Why peruse an article about breaking news when you can get to the point in 140 characters or less?

That same sense of efficiency is at the root of texting lingo. By typing fomo to a friend, it doesn’t indicate that I don’t know how to spell the phrase “fear of missing out,” but rather that we are so immersed and well versed in the English language that merely four letters can suffice in communicating a thought. Abbreviations are simply a product of a world that is moving faster than ever before. When there is faster Internet to browse, more media to consume, and never-ending news headlines, it is imperative that the speed and efficiency of our communication not fall behind.

In this evolution of efficiency, it is important to note many aspects of the English language that benefit—most notably, grammar. The same college student who hashtags and tweets funny links followed by lmao also proudly displays “grammar snob” or “syntax enthusiast” in their bio header. As more and more communication is occurring through technology and fewer words are actually spoken, it seems more focus is being placed on grammar and punctuation. When a simple period can mean the difference between an aggressive or inviting tone, more and more users will be punctuation-conscious. This delicate focus on punctuation enriches communication and celebrates its intricacies.

It is this attention to the details of the language that has helped English evolve. New abbreviations and alternate punctuation use are indicators of a language that is developing rather than remaining static, progressing without sacrificing value. Open any recent iMessage or Facebook chat, and scattered throughout the conversation are several *corrections, noting that although we want to get 2 the point, we aren’t simpletons.

The popularity and widespread use of abbreviations in tech communication should be seen as just another step towards the future of the English language. Merely keeping up with the fast-paced era we live in, texting lingo is clearly here to stay. So next time someone tries to reprimand you for your streamlined mode of communication, you can tell them 2 gtfo . lol. jk.

Fun article-thanks! I agree, we’ve reached another step-stone in the English language. Though, many may not agree with the change, I’m sure when there were changes in the language in the past, many didn’t agree but changes are inevitable. In all aspects of our life. For those who had trouble understanding the acronyms at the end you can go to http://www.abbreviations.com/ and look them up. GL! and HAGD!

Comments are closed.

- Science & Tech

A Linguist Explains Why Texting and Tweeting Aren’t Ruining the English Language

ORIGINAL REPORTING ON EVERYTHING THAT MATTERS IN YOUR INBOX.

By signing up, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy & to receive electronic communications from Vice Media Group, which may include marketing promotions, advertisements and sponsored content.

Why it’s time to stop worrying about the decline of the English language

People often complain that English is deteriorating under the influence of new technology, adolescent fads and loose grammar. Why does this nonsensical belief persist?

T he 21st century seems to present us with an ever-lengthening list of perils: climate crisis, financial meltdown, cyber-attacks. Should we stock up on canned foods in case the ATMs snap shut? Buy a shedload of bottled water? Hoard prescription medicines? The prospect of everything that makes modern life possible being taken away from us is terrifying. We would be plunged back into the middle ages, but without the skills to cope.

Now imagine that something even more fundamental than electricity or money is at risk: a tool we have relied on since the dawn of human history, enabling the very foundations of civilisation to be laid. I’m talking about our ability to communicate – to put our thoughts into words, and to use those words to forge bonds, to deliver vital information, to learn from our mistakes and build on the work done by others.

The doomsayers admit that this apocalypse may take some time – years, or decades, even – to unfold. But the direction of travel is clear. As things stand, it is left to a few heroic individuals to raise their voices in warning about the dangers of doing nothing to stave off this threat. “There is a worrying trend of adults mimicking teen-speak. They are using slang words and ignoring grammar,” Marie Clair, of the Plain English Campaign , told the Daily Mail. “Their language is deteriorating. They are lowering the bar. Our language is flying off at all tangents, without the anchor of a solid foundation.”

The Queen’s English Society , a British organisation, has long been fighting to prevent this decline. Although it is at pains to point out that it does not believe language can be preserved unchanged, it worries that communication is at risk of becoming far less effective. “Some changes would be wholly unacceptable, as they would cause confusion and the language would lose shades of meaning,” the society says on its website.

With a reduced expressive capacity, it seems likely that research, innovation and the quality of public discourse would suffer. The columnist Douglas Rushkoff put it like this in a 2013 New York Times opinion piece : “Without grammar, we lose the agreed-upon standards about what means what. We lose the ability to communicate when respondents are not actually in the same room speaking to one another. Without grammar, we lose the precision required to be effective and purposeful in writing.”

At the same time, our laziness and imprecision are leading to unnecessary bloating of the language – “language obesity,” as the British broadcaster John Humphrys has described it. This is, he said, “the consequence of feeding on junk words. Tautology is the equivalent of having chips with rice. We talk of future plans and past history; of live survivors and safe havens. Children have temper tantrums and politicians announce ‘new initiatives’.”

It is frightening to think where all this might lead. If English is in such a bad state now, what will things be like in a generation’s time? We must surely act before it is too late.

B ut there is something perplexing about claims like this. By their nature, they imply that we were smarter and more precise in the past. Seventy-odd years ago, people knew their grammar and knew how to talk clearly. And, if we follow the logic, they must also have been better at organising, finding things out and making things work.

John Humphrys was born in 1943. Since then, the English-speaking world has grown more prosperous, better educated and more efficiently governed, despite an increase in population. Most democratic freedoms have been preserved and intellectual achievement intensified.

Linguistic decline is the cultural equivalent of the boy who cried wolf, except the wolf never turns up. Perhaps this is why, even though the idea that language is going to the dogs is widespread, nothing much has been done to mitigate it: it’s a powerful intuition, but the evidence of its effects has simply never materialised. That is because it is unscientific nonsense.

There is no such thing as linguistic decline, so far as the expressive capacity of the spoken or written word is concerned. We need not fear a breakdown in communication. Our language will always be as flexible and sophisticated as it has been up to now. Those who warn about the deterioration of English haven’t learned about the history of the language, and don’t understand the nature of their own complaints – which are simply statements of preference for the way of doing things they have become used to. The erosion of language to the point that “ultimately, no doubt, we shall communicate with a series of grunts” (Humphrys again) will not, cannot, happen. The clearest evidence for this is that warnings about the deterioration of English have been around for a very long time.

In 1785, a few years after the first volume of Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire had been published, things were so bad that the poet and philosopher James Beattie declared: “Our language (I mean the English) is degenerating very fast.” Some 70 years before that, Jonathan Swift had issued a similar warning. In a letter to Robert, Earl of Oxford, he complained: “From the Civil War to this present Time, I am apt to doubt whether the Corruptions in our Language have not at least equalled the Refinements of it … most of the Books we see now a-days, are full of those Manglings and Abbreviations. Instances of this Abuse are innumerable: What does Your Lordship think of the Words, Drudg’d, Disturb’d, Rebuk’t, Fledg’d, and a thousand others, every where to be met in Prose as well as Verse?”

Swift would presumably have thought The History of the Decline and Fall, revered as a masterpiece today, was a bit of a mess. He knew when the golden age of English was: “The Period wherein the English Tongue received most Improvement, I take to commence with the beginning of Queen Elizabeth’s Reign, and to conclude with the Great Rebellion in [Sixteen] Forty Two.”

But the problem is that writers at that time also felt they were speaking a degraded, faltering tongue. In The Arte of English Poesie, published in 1589, the critic George Puttenham fretted about the importation of new, foreign words – “strange terms of other languages … and many dark words and not usual nor well sounding, though they be daily spoken in Court.” That was halfway through Swift’s golden age. Just before it, in the reign of Elizabeth’s sister, Mary, the Cambridge professor John Cheke wrote with anxiety that “Our own tongue should be written clean and pure, unmixed and unmangled with borrowing of other tongues.”

This concern for purity – and the need to take a stand against a rising tide of corruption – goes back even further. In the 14th century, Ranulf Higden complained about the state English was in. His words, quoted in David Crystal’s The Stories of English , were translated from the Latin by a near-contemporary, John Trevisa: “By intermingling and mixing, first with Danes and afterwards with Normans, in many people the language of the land is harmed, and some use strange inarticulate utterance, chattering, snarling, and harsh teeth-gnashing.”

That’s five writers, across a span of 400 years, all moaning about the same erosion of standards. And yet the period also encompasses some of the greatest works of English literature.

It’s worth pausing here to take a closer look at Trevisa’s translation, for the sentence I’ve reproduced is a version in modern English. The original is as follows: “By commyxstion and mellyng furst wiþ danes and afterward wiþ Normans in menye þe contray longage ys apeyred, and som vseþ strange wlaffyng, chyteryng, harrying and garryng, grisbittyng.”

For those who worry about language deteriorating, proper usage is best exemplified by the speech and writing of a generation or so before their own. The logical conclusion is that the generation or two before that would be even better, the one before that even more so. As a result, we should find Trevisa’s language vastly more refined, more correct, more clear and more effective. The problem is, we can’t even read it.

Hand-wringing about standards is not restricted to English. The fate of every language in the world has been lamented by its speakers at some point or another. In the 13th century, the Arabic lexicographer Ibn Manzur described himself as a linguistic Noah – ushering words into a protective ark in order that they might survive the onslaught of laziness. Elias Muhanna, a professor of comparative literature, describes one of Manzur’s modern-day counterparts: “Fi’l Amr, a language-advocacy group [in Lebanon], has launched a campaign to raise awareness about Arabic’s critical condition by staging mock crime scenes around Beirut depicting “murdered” Arabic letters, surrounded by yellow police tape that reads: ‘Don’t kill your language.’”

The linguist Rudi Keller gives similar examples from Germany. “Hardly a week goes by,” he writes, “in which some reader of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung doesn’t write a letter to the editor expressing fear for the future of the German language.” As Keller puts it: “For more than 2,000 years, complaints about the decay of respective languages have been documented in literature, but no one has yet been able to name an example of a ‘decayed language’.” He has a point.

The hard truth is that English, like all other languages, is constantly evolving. It is the speed of the change, within our own short lives, that creates the illusion of decline. Because change is often generational, older speakers recognise that the norms they grew up with are falling away, replaced with new ones they are not as comfortable using. This cognitive difficulty doesn’t feel good, and the bad feelings are translated into criticism and complaint. We tend to find intellectual justifications for our personal preferences, whatever their motivation. If we lived for hundreds of years, we would be able to see the bigger picture. Because when you zoom out, you can appreciate that language change is not just a question of slovenliness: it happens at every level, from the superficial to the structural.

Any given language is significantly reconfigured over the centuries, to the extent that it becomes totally unrecognisable. But, as with complex systems in the natural world, there is often a kind of homeostasis: simplification in one area can lead to greater complexity in another. What stays the same is the expressive capacity of the language. You can always say what needs to be said.

F requently, these changes are unexpected and revealing. They shed light on the workings of our minds, mouths and culture. One common driver of linguistic change is a process called reanalysis. This can happen when a language is learned for the first time, when babies begin to talk and construe what they hear slightly differently from their parents. In the abstract, it sounds complex but, in fact, it is straightforward: when a word or sentence has a structural ambiguity, what we hear could be an instance of A, but it could also be an instance of B. For years, A has held sway, but suddenly B catches on – and changes flow from that new understanding.

Take the words adder, apron and umpire. They were originally “nadder”, “napron” and “numpire”. Numpire was a borrowing from the French non per – “not even” – and described someone who decided on tie-breaks in games. Given that numpire and those other words were nouns, they often found themselves next to an indefinite article – a or an – or the first-person possessive pronoun, mine. Phrases such as “a numpire” and “mine napron” were relatively common, and at some point – perhaps at the interface between two generations – the first letter came to be seen as part of the preceding word. The prerequisite for reanalysis is that communication is not seriously impaired: the reinterpretation takes place at the level of the underlying structure. A young person would be able to say “where’s mine apron?” and be understood, but they would then go on to produce phrases such as “her apron” rather than “her napron”, which older folk presumably regarded as idiotic.

Another form that linguistic change often takes is grammaticalisation: a process in which a common phrase is bleached of its independent meaning and made into a word with a solely grammatical function. One instance of this is the verb “to go”, when used for an action in the near future or an intention. There is a clue to its special status in the way we have started saying it. We all inherit an evolutionarily sensible tendency to expend only the minimum effort needed to complete a task. For that reason, once a word has become a grammatical marker, rather than something that carries a concrete meaning, you do not need it to be fully fleshed out. It becomes phonetically reduced – or, as some would have it, pronounced lazily. That is why “I’m going to” becomes “I’m gonna”, or even, in some dialects, “Imma”. But this change in pronunciation is only evident when “going to” is grammatical, not when it is a verb describing real movement. That is why you can say “I’m gonna study history” but not “I’m gonna the shops”. In the first sentence, all “I’m going to”/“I’m gonna” tells you is that the action (study history) is something you intend to do. In the second one, the same verb is not simply a marker of intention, it indicates movement. You cannot therefore swap it for another tense (“I will study history” v “I will the shops”).

“Will”, the standard future tense in English, has its own history of grammaticalisation. It once indicated desire and intention. “I will” meant “I want”. We can still detect this original English meaning in phrases such as “If you will” (if you want/desire). Since desires are hopes for the future, this very common verb gradually came to be seen simply as a future marker. It lost its full meaning, becoming merely a grammatical particle. As a result, it also gets phonetically reduced, as in “I’ll”, “she’ll” and so on.

Human anatomy makes some changes to language more likely than others. The simple mechanics of moving from a nasal sound (m or n) to a non-nasal one can make a consonant pop up in between. Thunder used to be “thuner”, and empty “emty”. You can see the same process happening now with words such as “hamster”, which is often pronounced with an intruding “p”. Linguists call this epenthesis. It may sound like a disease, but it is definitely not pathological laziness – it’s the laws of physics at work. If you stop channelling air through the nose before opening your lips for the “s”, they will burst apart with a characteristic pop, giving us our “p”.

The way our brain divides up words also drives change. We split them into phonemes (building blocks of sound that have special perceptual significance) and syllables (groups of phonemes). Sometimes these jump out of place, a bit like the tightly packed lines in a Bridget Riley painting. Occasionally, such cognitive hiccups become the norm. Wasp used to be “waps”; bird used to be “brid” and horse “hros”. Remember this the next time you hear someone “aks” for their “perscription”. What’s going on there is metathesis, and it’s a very common, perfectly natural process.

Sound changes can come about as a result of social pressures: certain ways of saying things are seen as having prestige, while others are stigmatised. We gravitate towards the prestigious, and make efforts to avoid saying things in a way that is associated with undesirable qualities – often just below the level of consciousness. Some forms that become wildly popular, such as Kim Kardashian’s vocal fry, although prestigious for some, are derided by others. One study found that “young adult female voices exhibiting vocal fry are perceived as less competent, less educated, less trustworthy, less attractive and less hireable”.

All this is merely a glimpse of the richness of language change. It is universal, it is constant, and it throws up extraordinary quirks and idiosyncrasies, despite being governed by a range of more-or-less regular processes. Anyone who wants to preserve some aspect of language that appears to be changing is fighting a losing battle. Anyone who wishes people would just speak according to the norms they had drummed into them when they were growing up may as well forget about it. But what about those, such as the Queen’s English Society, who say they merely want to ensure that clear and effective communication is preserved; to encourage good change, where they find it, and discourage bad change?

The problem arises when deciding what might be good or bad. There are, despite what many people feel, no objective criteria by which to judge what is better or worse in communication. Take the loss of so-called major distinctions in meaning bemoaned by the Queen’s English Society. The word “disinterested”, which can be glossed “not influenced by considerations of personal advantage”, is a good example. Whenever I hear it nowadays, it is being used instead to mean “uninterested, lacking in interest”. That’s a shame, you could argue: disinterest is a useful concept, a way (hopefully) to talk about public servants and judges. If the distinction is being lost, won’t that harm our ability to communicate? Except that, of course, there are many other ways to say disinterested: unbiased, impartial, neutral, having no skin in the game, without an axe to grind. If this word disappeared tomorrow, we would be no less able to describe probity and even-handedness in public life. Not only that, but if most people don’t use it properly, then the word itself has become ineffective. Words cannot really be said to have an existence beyond their common use. There is no perfect dictionary in the sky with meanings that are consistent and clearly defined: real-world dictionaries are constantly trying to catch up with the “common definition” of a word.

But here’s the clincher: disinterested, as in “not interested”, has actually been around for a long time. The blogger Jonathon Owen cites the Oxford English dictionary as providing evidence that “both meanings have existed side by side from the 1600s. So there’s not so much a present confusion of the two words as a continuing, three-and-a-half-century-long confusion.”

S o what is it that drives the language conservationists? Younger people tend to be the ones who innovate in all aspects of life: fashion, music, art. Language is no different. Children are often the agents of reanalysis, reinterpreting ambiguous structures as they learn the language. Young people move about more, taking innovations with them into new communities. Their social networks are larger and more dynamic. They are more likely to be early adopters of new technology, becoming familiar with the terms used to describe them. At school, on campus or in clubs and pubs, groups develop habits, individuals move between them, and language change is the result.

What this means, crucially, is that older people experience greater linguistic disorientation. Though we are all capable of adaptation, many aspects of the way we use language, including stylistic preferences, have solidified by our 20s. If you are in your 50s, you may identify with many aspects of the way people spoke 30-45 years ago.

This is what the author Douglas Adams had to say about technology. Adapted slightly, it could apply to language, too:

– Anything that is in the world when you’re born is normal and ordinary and is just a natural part of the way the world works. – Anything that’s invented between when you’re 15 and 35 is new and exciting and revolutionary. – Anything invented after you’re 35 is against the natural order of things.

Based on that timescale, formal, standard language is about 25 years behind the cutting edge. But if change is constant, why do we end up with a standard language at all? Well, think about the institutions that define standard language: universities, newspapers, broadcasters, the literary establishment. They are mostly controlled by middle-aged people. Their dialect is the dialect of power – and it means that everything else gets assigned a lower status. Deviations might be labelled cool, or creative, but because people generally fear or feel threatened by changes they do not understand, they are more likely to be called bad, lazy or even dangerous. This is where the “standards are slipping” narrative moves into more unpleasant territory. It’s probably OK to deviate from the norm if you are young – as long as you are also white and middle-class. If you are from a group with fewer social advantages, even the forms that your parents use are likely to be stigmatised. Your innovations will be doubly condemned.

The irony is, of course, that the pedants are the ones making the mistakes. To people who know how language works, pundits such as Douglas Rushkoff only end up sounding ignorant, having failed to really interrogate their views. What they are expressing are stylistic preferences – and that’s fine. I have my own, and can easily say “I hate the way this is written”, or even “this is badly written”. But that is shorthand: what is left off is “in my view” or “according to my stylistic preferences and prejudices, based on what I have been exposed to up to now, and particularly between the ages of five and 25”.

Mostly, pedants do not admit this. I know, because I have had plenty of arguments with them . They like to maintain that their prejudices are somehow objective – that there are clear instances of language getting “less good” in a way that can be independently verified. But, as we have seen, that is what pedants have said throughout history. George Orwell, a towering figure in politics, journalism and literature, was clearly wrong when he imagined that language would become decadent and “share in the general collapse” of civilisation unless hard work was done to repair it. Maybe it was only conscious and deliberate effort to arrest language change that was responsible for all the great poetry and rhetoric in the generation that followed him – the speeches “ I have a dream ” and “We choose to go to the moon”, the poetry of Seamus Heaney or Sylvia Plath, the novels of William Golding, Iris Murdoch, John Updike and Toni Morrison. More likely, Orwell was just mistaken.

The same is true of James Beattie, Jonathan Swift, George Puttenham, John Cheke and Ranulf Higden. The difference is that they didn’t have the benefit of evidence about the way language changes over time, unearthed by linguists from the 19th century onwards. Modern pedants don’t have that excuse. If they are so concerned about language, you have to wonder, why haven’t they bothered to get to know it a little better?

Adapted from Don’t Believe a Word: The Surprising Truth About Language by David Shariatmadari, published by W&N on 22 August and available at guardianbookshop.co.uk . Also available as an unabridged audio edition from Orion Audio

- The long read

Most viewed

Become an Insider

Sign up today to receive premium content.

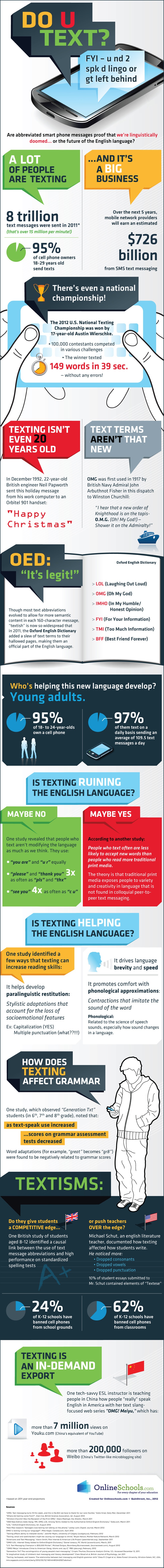

Is Texting Ruining the English Language? [Infographic]

Anuli is a writer and new-media enthusiast who dreams about becoming the sixth Spice Girl. Until then follow her on Google+ or Twitter: @akaanuli .

Mom was right, it’s not what you say, but how you say it. And today’s students prefer to say it through text messaging.

A new infographic released by OnlineSchools.com explores whether the widespread practice of abbreviated messaging is proof that the future of the English language is changing.

Communicating through text messaging has become so popular that the Oxford English Dictionary now includes “textish” terms, such as LOL (laugh out loud), OMG (oh my God) and TMI (too much information), making them an official part of the English language. OMG, we’ve sure come a long way from the Queen’s English!

Text messaging is a common method of communication for students: 97 percent of young adults who own a cell phone text on a daily basis. Since young adults send an average of 109.5 text messages a day, it is no surprise that texting slang has found its way into the classroom.

The effect of texting on grammar has been highly debated by educators.

One study of “Generation Txt” students showed that scores on grammar assessment tests decreased as text-speak use increased. However, a separate British study of students ages 8–12 discovered a link between text messages and high performance on standardized spelling tests.

It is uncertain whether text messaging has doomed the future of the English language, but one thing is for sure: Students will continue to text.

This infographic originally appeared on OnlineSchools.com.

- Smartphones

Related Articles

Unlock white papers, personalized recommendations and other premium content for an in-depth look at evolving IT

Copyright © 2024 CDW LLC 200 N. Milwaukee Avenue , Vernon Hills, IL 60061 Do Not Sell My Personal Information

- Localization & Translation

- BLEND Voice

- Data for AI

- Transcription

- Technologies

- Integrations & Partnerships

- Spotlight Integrations

- By Industry

- Freelancers i Translators, voice actors, linguistic experts, content writers -apply here

Impact of Texting on Language

Texting might seem to be corrupting the language skills of people, but the fact is language is always changing and evolving, and if it is evolving towards texting, that’s okay.

One thing I’ve noticed that’s prevalent among people who are highly educated and trained in a subject – like, say, translation services and linguistics – is the instinct to preserve your expertise. By that I mean that once people consider themselves to be experts on a subject, they must always be able to comment judiciously on any related subject – even if they really don’t know what they’re talking about.

You see this a lot with new technologies. Someone like me, who considers himself to be very knowledgeable about language in general and translation in specific, encounters a new technology that affects language and the urge, the instinct to be able to instantly comprehend it and its implications is strong – which pushes me to speak on subjects I’m perhaps not really all that qualified to speak on. I try very hard to avoid this temptation, but not all of my peers do.

Take texting: This is a relatively new phenomenon in language, and many people have decried texting as a decline in the language skills of the younger generation.

This is right on schedule, of course, with the past generational angst that leads every generation to complain that the new generation is a step-down, and despairing of the future of society based on some supposedly awful things the kids are doing. Texting is the linguistic world’s bugbear these days. I personally doubt texting’s impact will be negative – but there will be an impact, of that you can be sure.

Language Evolution and Brevity

One thing is certain: The language we speak today (for simplicity I’ll use English as the example) is very different from the language we spoke a few hundred years ago. The first example of ‘modern English’ most children encounter in school is likely Chaucer’s ‘Canterbury Tales.

To the average modern person, Chaucer is probably only halfway intelligible – but you can at least pick your way through it without a separate language course or language translation. The Canterbury Tales was published in the middle of the 15th Century. Prior to that, English would have been unrecognisable to us modern folk.

Just a few hundred years later, in Shakespeare’s time , English was still kind of linguistic oddity from a modern perspective, but had modernised to the point that you don’t really have trouble with the language in those plays – you have trouble with the references.

More recently, we can point to the impact of the modern dictionary on standardisation. The word ‘president’ was written commonly with an ‘f’ ( prefident ) in 1789 when George Washington become the USA’s first one, and spelling oddities continued until dictionaries caused a roar of standardisation that also carried over into grammar and punctuation. These big and little things have shaped our language – and continue to shape it today.

One of the major forces on language is the need for efficiency. Spoken language has always valued speed of communication over length and complexity. The written word has evolved differently, as the written word has always taken longer to read and was designed to be communication over the distance of time and space.

But texting is a whole new thing – a written communication designed to be as fast and flexible as spoken language. The result is an increasing focus on efficiency that will, I think, end with our language more closely resembling texting than the other way around.

Consider some of the features of texting:

- Abbreviations as words . Things like LOL and BRB have become words unto themselves, used in a variety of grammatical constructions. Instead of spelling things out, the abbreviations become words themselves.

- Dropped vowels . Space being a premium, many texts drop vowels altogether in favour of the speed and simplicity of consonants – and yet, if you notice, you have no trouble understanding the words as written (or typed). This isn’t unheard of: Arabic, for example, doesn’t include vowels in its written form – they are assumed. It’s not impossible to imagine an English that is written with many if not all vowels dropped and implied – and that will be the result of texting.

Formal Vs. Informal

Another possible impact of texting might be the formation of formal and informal modes in English. Right now English is English and the formality or lack thereof is implied through use of grammar and vocabulary – but texting might split the language into a formal written mode (similar to what we use today) and an informal one, based on texting conventions, that might also bleed over into spoken communications.

Again, this isn’t unheard of in other languages, and while it might seem alien to English speakers at the moment, in some way it’s happening right now, because texting is an informal form of the language. You understand texts – but you would never write a business letter in text format, would you?

Of course, texting might be a brief technological blip that is replaced by some other technology in a few years, and all this theorising may be for naught. Something like texting has to stick around for a long time before it can really have a large impact – and a permanent impact – on the language. If it fades away tomorrow its impact will be brief and little more than a historical footnote with some intriguing examples, but no lasting effect.

Whether or not you’re happy to think about that or not might depend on your reaction to technology, of course; technophobes have a tendency to disdain any changes that stem from new gadgets or new systems, believing them to be ‘fruit of the poisonous tree’ or something similar.

But in language there really is no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ way. All that matters is that it does its job communicating ideas and concepts in an efficient and flexible manner, as well as recording information and facilitating everyday tasks. As long as it’s doing its job, in other words, it doesn’t matter what form it eventually takes.

Contact us to learn more about BLEND’s translation services and localization services .

Liraz Postan

Liraz is an International SEO and Content Expert with over 13 years of experience.

Need fast, high-quality translation?

What our customers are saying

International YouTube Star Nuseir Yassin, Owner of Nas Daily, Grows Russian Language YouTube Channel 35% with BLEND

Simply Increases App Conversion Rate by 10% with BLEND Localization Services

Lightricks Improved Localization Delivery Rates by 120%!

BLEND Helps Payoneer Reduce KYC Verification Times with Localization Services in 50 Languages

Get in Touch

- Is Texting Killing the English Language?

- Educational

- Posted on June 8, 2016

- By spinkerton

- In Educational

But let’s go back a while. Writing was invented over 5,00 years ago, and language likely traces back perhaps 80,000 years. So talking came first; writing is just an artifice that came along much later. Due to this, writing was first based on the way people talk, with short sentences — think of the Old Testament. However, while talking is largely subconscious and rapid, writing is slower and more deliberate. Like language assessment tests, speaking tests are always shorter in duration than written tests. But in getting back to texting – It’s developing its own type of grammar (no pun intended). Take LOL for example . It doesn’t actually mean “laughing out loud” in a literal sense anymore. LOL has evolved into something much subtler and sophisticated and is used even when nothing is remotely amusing. Jessica texts “Where have you been?” and David texts back “LOL at the library studying for two hours.” LOL signals basic empathy between texters, easing tension and creating a sense of equality. Instead of having a literal meaning, it does something — conveying an attitude — just like the -ed ending conveys past tense rather than “meaning” anything. LOL , of all things, is grammar.

Over time, the meaning of a word or an expression evolves — meat used to mean any kind of food , silly used to mean, believe it or not, blessed.

Civilization, then, is fine — people typing away on their smartphones are fluently using a code separate from the one they use in actual writing, and there’s no evidence that texting is ruining composition skills. Worldwide people speak differently from the way they write, and texting — quick, casual and only intended to be read once — is actually a way of talking with your fingers.

All indications are that America’s youth are doing it quite well. Texting, far from being a scourge, is a work in progress.

This essay is adapted from McWhorter’s talk at TED 2013.

Latest Anti-Discrimination Rules: Language Assistance for Non-English Speakers

Does bilingualism in america threaten the english language.

Shelby has worked at Language Testing International for over four years in content development and digital marketing. She holds a master's degree in European and Russian Studies from Yale University and is passionate about all things language and culture.

Recommended Posts

The Benefits of Periodic Language Proficiency Assessment for World Language Teachers

Empowering Agentive Learning with ACTFL OPIc Tests and Diagnostic Grids

Advocating for Multilingualism and Language Education: 2023 Language Advocacy Days

Is Texting Ruining the English Language? Essay Sample

Some say that it is queering children’s ability to efficaciously pass on both written and orally. and there are statements stating that it really helps kids pass on better. In this essay I will be looking at both sides of the statement and seeking to come up with a decision as to whether texting is really destructing the English linguistic communication. Arguments against this statement are varied; some believe it helps the kids communicate more efficaciously. As a kid communication by text can be seen as ‘cool’ i personally believe it’s merely a tendency that like others will come and travel. At the minute the tendency of text message linguistic communication is really popular and with most English citizens having a nomadic it is really widely spread but one uncertainty people really use text message linguistic communication in mundane address and other things such as school and work. I think that the usage of this linguistic communication is strictly for texting and should be kept to that. while others think it’s merely the English linguistic communication germinating as it has done for 100s of old ages. for illustration our linguistic communication presently evolved from Shakespearean and so on.

Peoples believe that the English linguistic communication is flexible and used to alter therefore it can accommodate to alterations. in this instance text messaging; Text messaging is a perfect illustration of how people adapt and mould linguistic communication to accommodate different contexts. Text messaging can besides be seen a more of a convenience than a new linguistic communication in itself. more a tool than the creative activity of a whole new linguistic communication. Text message linguistic communication is extremely abbreviated an therefore saves clip. clip that can be used to make other things. another ground why people like it so much. Arguments holding with this statement besides differ. The chief statement to be considered is that people can be considered as field lazy for utilizing this linguistic communication. The usage of abbreviations allows the user to avoid holding to spell right and hence confines the individual to the text linguistic communication itself; hence I believe its pure indolence.

Peoples would besides reason that its set uping children’s ability to pass on both written and orally which in their hereafter lives would be a monolithic job with school. occupations and what non. The people reasoning against this believe that texting itself is doing kids to bury the regulations of RP English and wholly disregard the usage of proper grammar whereas I would state it’s informal and merely a tool of convenience. I personally believe that it is harmless and is merely an easier and much more convenient manner of pass oning I believe that some people are looking excessively profoundly into the result of text message linguistic communication and that the linguistic communication itself is perchance merely a tendency instead than a whole new linguistic communication emerging. Like the Morse codification I believe this is merely advancement in engineering and that every bit long as it is kept on text so the English linguistic communication should confront no problem in

lasting. merely as it has done for many old ages.

More about Essay Database

- Essay Database Summary

- Essay Database Accounting

- Essay Database Anthropology

- Essay Database Architecture

- Essay Database Biology

- Essay Database Business

- Essay Database Chemistry

- Essay Database Computer Science

- Essay Database Criminology

- Essay Database Culture and Arts

- Essay Database Economics

- Essay Database Geography

- Essay Database History

- Essay Database Human resources

- Essay Database International Studies

- Essay Database Jurisprudence

- Essay Database Linguistics

- Essay Database Management

- Essay Database Marketing

- Essay Database Mathematics

- Essay Database Medicine

- Essay Database Movies

- Essay Database Music

- Essay Database Physics

- Essay Database Politics

- Essay Database Psychology

- Essay Database Relationships

- Essay Database Religion

- Essay Database Science

- Essay Database Society

- Essay Database Sociology

- Essay Database Technology

- Essay Database Television

- Essay Database Tourism

- Essay Database Women and Gender

Related Posts

- Television: Is it Ruining Our Society? Essay Sample

- Is Hip-Hop Music Ruining Our Teenagers?

- Texting While Driving is Dangerous Essay

- Texting and Driving

- Texting Effects on Written Communication Skills

- Texting and Driving case study

- Texting & Driving : 1 Way 2 Die

- Explore the Varieties of and Attitudes to Texting

- What Are the Importance of English Language in This Modern World Essay Sample

- The Aspired Macbeth and the Evil Macbeth Book Review

How about getting full access immediately?

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you’re on board with our cookie policy

Is Texting Ruining the English Language?

- Word count: 505

- Category: Language

A limited time offer! Get a custom sample essay written according to your requirements urgent 3h delivery guaranteed

Some say that it is thwarting children’s ability to effectively communicate both written and orally, and there are arguments saying that it actually helps children communicate better. In this essay I will be looking at both sides of the argument and trying to come up with a conclusion as to whether texting is actually destroying the English language. Arguments against this statement are varied; some believe it helps the children communicate more effectively. As a child communicating by text can be seen as ‘cool’ i personally believe it’s just a trend that like others will come and go. At the moment the trend of text message language is very popular and with most English citizens owning a mobile it is very widely spread but i doubt people actually use text message language in everyday speech and other things such as school and work. I think that the use of this language is purely for texting and should be kept to that. while others think it’s just the English language evolving as it has done for hundreds of years, for example our language currently evolved from Shakespearean and so on.

People believe that the English language is flexible and used to change therefore it can adapt to changes, in this case text messaging; Text messaging is a perfect example of how people adapt and mould language to suit different contexts. Text messaging can also be seen a more of a convenience than a new language in itself, more a tool than the creation of a whole new language. Text message language is highly abbreviated an therefore saves time, time that can be used to do other things, another reason why people like it so much. Arguments agreeing with this statement also differ. The main argument to be considered is that people can be considered as plain lazy for using this language. The use of abbreviations allows the user to avoid having to spell correctly and therefore confines the person to the text language itself; therefore I believe its pure laziness.

People would also argue that its effecting children’s ability to communicate both written and orally which in their future lives would be a massive problem with school, jobs and what not. The people arguing against this believe that texting itself is causing children to forget the rules of RP English and completely ignore the use of proper grammar whereas i would say it’s informal and just a tool of convenience. I personally believe that it is harmless and is just an easier and much more convenient way of communicating I believe that some people are looking too deeply into the outcome of text message language and that the language itself is possibly just a trend rather than a whole new language emerging. Like the Morse code I believe this is just advancement in technology and that as long as it is kept on text then the English language should face no trouble in surviving, just as it has done for many years.

Related Topics

We can write a custom essay

According to Your Specific Requirements

Sorry, but copying text is forbidden on this website. If you need this or any other sample, we can send it to you via email.

Copying is only available for logged-in users

If you need this sample for free, we can send it to you via email

By clicking "SEND", you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We'll occasionally send you account related and promo emails.

We have received your request for getting a sample. Please choose the access option you need:

With a 24-hour delay (you will have to wait for 24 hours) due to heavy workload and high demand - for free

Choose an optimal rate and be sure to get the unlimited number of samples immediately without having to wait in the waiting list

3 Hours Waiting For Unregistered user

Using our plagiarism checker for free you will receive the requested result within 3 hours directly to your email

Jump the queue with a membership plan, get unlimited samples and plagiarism results – immediately!

We have received your request for getting a sample

Only the users having paid subscription get the unlimited number of samples immediately.

How about getting this access immediately?

Or if you need this sample for free, we can send it to you via email.

Your membership has been canceled.

Your Answer Is Very Helpful For Us Thank You A Lot!

Emma Taylor

Hi there! Would you like to get such a paper? How about getting a customized one?

Get access to our huge, continuously updated knowledge base

Advertisement

Supported by

A Comic Riff on Greek Tragedy, With an Irish Accent

In Ferdia Lennon’s charming debut, “Glorious Exploits,” Athenian prisoners stage Euripides for their wine-swilling, foul-mouthed captors.

- Share full article

By Annalisa Quinn

Annalisa Quinn is an articles editor at The Boston Globe Magazine.

GLORIOUS EXPLOITS, by Ferdia Lennon

There is a small, moving detail in Plutarch’s account of the Athenian defeat at Syracuse during the final stages of the Peloponnesian War.

In 412 BC, the Athenian forces, then the dominant power in the Aegean, overplayed their hand. Routed in a brutal sea battle, rounded up as prisoners into the quarries of Syracuse and given starvation rations, some Athenians survived, Plutarch writes, because the Syracusans so loved the tragedies of Euripides that they offered food or freedom in exchange for verses. It would be like if the Viet Cong released American P.O.W.s for singing Elvis.

“They say that many Athenians who reached home in safety greeted Euripides with affectionate hearts,” Plutarch wrote, and told him “that they had been set free from slavery for rehearsing what they remembered of his works.”

This is the seed of Ferdia Lennon’s breezy, winning debut, “Glorious Exploits,” set in ancient Syracuse but written in the language of contemporary Ireland, where Lennon was raised. There has been a pleasing recent turn away from making ancient people in fiction speak in the style of Victorian poets — handmaidens, smiting, woe, bosoms, etc. — including Emily Wilson’s sublimely wry, unpretentious Homer translations and Pat Barker’s (less successful) feminist retellings of Athenian tragedy.

Lennon’s vernacular gives the novel a shambolic charm, a story told in a Dublin bar by a drunk lurching between poetry and obscenity — your best friend tonight even if he might not remember you tomorrow.

Lampo, the narrator, is an illiterate, unemployed potter with a love of wine. He begins the story on a sunny morning, going to the quarry with his friend Gelon to “feed the Athenians,” the way someone might idly feed ducks.

They smell the captives before seeing them. “Ah, and I like the way they smell,” thinks Lampo. “It’s awful, but it’s wonderful awful. They smell like victory and more. Every Syracusan feels it when they get that smell. Even the slaves feel it. Rich or poor, free or not, you get a whiff of those pits, and your life seems somehow richer than it did before, your blankets warmer, your food tastier.”

The Athenians also serve another purpose. “A mouthful of olives for some ‘Medea,’” Gelon shouts, as the starving captives crowd around, trying to remember lines. Eventually, the two plot to put on a full production of “Medea” — “with chorus, masks, and shit” — along with Euripides’s newest tragedy, “The Trojan Women,” never before seen in Sicily.

The middle of the novel is essentially a buddy comedy: They secure the backing of a mysterious funder, Lampo spends their money on booze and clothes, they pick up ruffians eager to help and they grow somewhat fond of the Athenians (Lampo periodically ruffles their hair, which floats away in the breeze from malnutrition).

This is all fun — I first read the novel in one happy sitting, on a plane — but Lennon attempts to go deeper, with mixed success. One sign of ambition is his choice of play: Euripides probably wrote some 90 in his lifetime, and Plutarch doesn’t specify which the captives sang for freedom.

“Medea ,” one of his most famous, is an obvious choice. But “Trojan Women” — about Hecuba, Cassandra, and the women left after the sacking of Troy as they wait to be taken into slavery — is something else. Instead of the typical tragic arc from power to ruin, it begins and ends in misery. The classicist Gilbert Murray described it like this: “The only movement of the drama is a gradual extinguishing of all the familiar lights of human life.”

“Trojan Women" was likely at least partly inspired by the Athenian army’s slaughter of the entire adult male population of Melos the year before it premiered. The men were butchered, the women and children sold, in a tactic summarized by Thucydides as “the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.”

This setup — conquerors made captive, then made to play versions of their own victims before an audience of their recent conquerors — promises an interesting experiment about reversal, sympathy, and power. But instead, the novel seems to assert rather than show or interrogate its central idea, a vague one about the power of storytelling — a phrase that makes me feel like a dutiful A.P. English student or the kind of person who owns an “I <3 BOOKS” mug.

In “The Iliad,” Hecuba says that she wants to cannibalize her son’s killer, to “eat his liver” like a carrion bird on the battlefields of Troy. In “Medea,” the queen’s rage at her unfaithful husband is so great that she slaughters her own children. These are stories about deep, excruciating ties of love and friendship and family, severed again and again by war and death.

There’s nothing approximating that depth of feeling in Lennon’s novel. Relationships feel like those between drinking buddies: affectionate and fun, but bloodless.

GLORIOUS EXPLOITS | By Ferdia Lennon | Holt | 289 pp. | $26.99

Explore More in Books

Want to know about the best books to read and the latest news start here..

James McBride’s novel sold a million copies, and he isn’t sure how he feels about that, as he considers the critical and commercial success of “The Heaven & Earth Grocery Store.”

How did gender become a scary word? Judith Butler, the theorist who got us talking about the subject , has answers.

You never know what’s going to go wrong in these graphic novels, where Circus tigers, giant spiders, shifting borders and motherhood all threaten to end life as we know it .

When the author Tommy Orange received an impassioned email from a teacher in the Bronx, he dropped everything to visit the students who inspired it.

Do you want to be a better reader? Here’s some helpful advice to show you how to get the most out of your literary endeavor .

Each week, top authors and critics join the Book Review’s podcast to talk about the latest news in the literary world. Listen here .

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Texting has long been bemoaned as the downfall of the written word, "penmanship for illiterates," as one critic called it. To which the proper response is LOL. Texting properly isn't writing at all — it's actually more akin to spoken language. And it's a "spoken" language that is getting richer and more complex by the year.

In 2013, the average schoolchild struggles more with spelling, grammar and essay-writing: essential skills which before now were considered key to a good grasp of the English language. Text messaging is alienating English speakers from their native tongue and confusing non-natives who wish to learn the language. It promotes mis-spelling.

Is Text Messaging Ruining English? With every generation come cries that teenagers are destroying the language with their newfangled slang. The current grievance harps on the way casual language used in texts and instant messages inhibits kids from understanding how to write and speak "properly.". While amateur language lovers might think ...

One could argue that such fears are founded upon mere parochialism among the middle class, yet the evidence to suggest that text language is having a detrimental impact upon English is highly compelling. Journalists across the globe have condemned the casual usage of text language in formal mediums such as emails, yet the world only seems to ...

The article "I h8 txt msgs: How texting is wrecking our language", is an article written by Humphrys (2007), and it provides the discussion of the sidelining of the English dictionary in favor of a new language. The main point proposed by the article is that the influx of technology has destroyed the uses of the English language through the ...

The Bottom Line. -. April 15, 2015. 1. Nardin Sarkis. Staff Writer. Illustration by Carrie Ding, Staff Illustrator. We have all heard it before—be it from our grandparents, professors, or Time magazine covers—that texting abbreviations are killing the English language. While reflecting on the addition of lol, brb, and selfie to the Oxford ...

While some may dismiss "doge" and "smol" as insignificant, others know the internet is changing the fabric of the English language daily. Linguist Gretchen McCulloch has been writing about the ...

Linguist John McWhorter has a great new theory on what's really going on in modern texting. Far from being a scourge, texting is a linguistic miracle. Spoken human language has been around for about 150,000 years, but it wasn't until much later that written language came about; as he puts it: "If humanity has existed for 24 hours, writing ...

That is because it is unscientific nonsense. There is no such thing as linguistic decline, so far as the expressive capacity of the spoken or written word is concerned. We need not fear a ...

Text messaging is a common method of communication for students: 97 percent of young adults who own a cell phone text on a daily basis. Since young adults send an average of 109.5 text messages a day, it is no surprise that texting slang has found its way into the classroom. The effect of texting on grammar has been highly debated by educators.

Formal Vs. Informal. Another possible impact of texting might be the formation of formal and informal modes in English. Right now English is English and the formality or lack thereof is implied through use of grammar and vocabulary - but texting might split the language into a formal written mode (similar to what we use today) and an informal ...

Texting has long been accused as being the downfall of the written word, "penmanship for illiterates," as one critic called it. To which the likely response is LOL. Proper testing is not writing at all — it's actually more like the spoken language. It's a "spoken" language that is evolving and becoming more complex as time passes. But.

Lately, there has been discussion about how texting is affecting or ruining the english language. Texting has an affect on the the writing and speech of young adults for several reasons. The TED Talk "Txtng is Killing Language. JK!!" by John McWhorter explores how texting is not really affecting the writing of young adults for several reasons.

Texting can be called a fad or fashion which actually is taking the beauty of language and killing communication completely. We know that English is an evolving language and after so many years of use texting has become its integral part. After nearly 20 years of continuous and successful of texting language we find paradox results.

Michaela Cullington addresses the issue of text messaging possibly causing poor communication skills and the use of textspeak, abbreviations used during text messaging such as "LOL" and "g2g," in students' formal writing. Cullington argues that "texting actually has a minimal effect on student writing" (pg. 367).

Texting Is Ruining English Language Essay. 427 Words 2 Pages. Today many people believe that texting and other instant messaging programs are ruining the grammar and the knowledge level of the growing youth of this day and age. I believe that texting is not ruining our language and grammar because it has brought about advancements in technology ...

Texting is a fairly new form of communication that has taken the world by storm. It became popular around 2001, and originally had its limitations, such as the 160-character limit. But now that technology has advanced, texting has followed along and is now a convenient, casual, and a more immediate way of communicating.