What drives job satisfaction? Researchers think this is the answer

It's less of what you do, but more who you do it with. Image: Unsplash/Marten Bjork

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Douglas Broom

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Future of Work is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, future of work.

- Being interested in your work might not be the key to job satisfaction.

- Your boss and colleagues are more important, a new study of data going back to 1949 says.

- But being interested in what you do will improve your pay and promotion prospects.

Hate your job and want to move on? Chances are that it's down to your boss or the people you work with, rather than how interesting you find the work.

What defines job satisfaction?

A new study based on data going back to 1949 turns conventional wisdom about the sources of job satisfaction on its head. Far from the generally accepted notion that it's down to the work itself, people, it seems, could be the most important ingredient.

“To be satisfied with a job, you don’t have to worry too much about finding a perfect fit for your interests because we know other things matter too,” says Levin Hoff, an assistant professor of psychology at Houston University.

“As long as it’s something you don’t hate doing, you may find yourself very satisfied if you have a good supervisor, like your coworkers, and are treated fairly by your organization.”

To reach his conclusions, Hoff and his team analyzed 39,600 interviews conducted over 65 years.

Pay and promotions

They also found that while interest in a job may not matter much when it comes to satisfaction, it does help with career prospects. “Being interested in your work seems more important for job performance and the downstream consequences of performing well, like raises or promotions,” says Hoff.

Career guides have traditionally advised young people to look for a job in an area that fits with their personal interests. Hoff says it's still a useful approach but it's no predictor of long-term job satisfaction.

“In popular career guidance literature, it is widely assumed that interest fit is important for job satisfaction,” he says.

“Our results show that people who are more interested in their jobs tend to be slightly more satisfied, but interest assessments are more useful for guiding people towards jobs in which they will perform better and make more money.”

Job Satisfaction factors

Hoff’s findings are borne out by a study of 2,500 US workers last year in which more than half said the people they worked with and their immediate boss were more important to their job satisfaction than whether they were interested in their work.

Fewer than half of those surveyed said their satisfaction at work depended on their pay or their work-life balance, instead rating job security, paid holidays and their workplace environment, more highly.

A survey in June this year by HR firm Randstad found that although two-thirds felt COVID-19 had negatively impacted on their work, three-quarters thought their boss was supportive and was looking after their well-being.

Who’s happiest?

In the same survey, workers at both ends of the age range and those with higher qualifications said they were the most satisfied.

Men were more satisfied than women, although the balance was reversed among workers aged 45-67 with older women enjoying more job satisfaction than male colleagues.

On the global stage, India has the most satisfied workforce, followed by Argentina and the US, while, according to Randstad , Portugal, Hong Kong, SAR and Japan sit at the bottom of the job satisfaction league table.

Future skills

Still, as Hoff’s report says, while it may not always be key to satisfaction, interesting work plays an important role in many people’s careers and performance. And with the advent of the Fourth Industrial Revolution , jobs that exercise the grey matter will grow in importance.

The World Economic Forum’s Future of Jobs Report 2020 forecasts that COVID-19 will accelerate remote working and automation, predicting that machines will displace 85 million manual repetitive jobs.

At the same time, it says, 97 million new jobs will be created. In-demand skills of the future will include analytical thinking and problem solving as well as creativity, social influencing, team working and resilience.

Have you read?

This chart shows which countries have the highest and lowest job satisfaction, purpose or profit: which would give you more job satisfaction, don't miss any update on this topic.

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Jobs and the Future of Work .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Strategic Cybersecurity Talent Framework

The green skills gap: Educational reform in favour of renewable energy is now urgent

Roman Vakulchuk

April 24, 2024

How the ‘NO, NO’ Matrix can help professionals plan for success

April 19, 2024

The State of Social Enterprise: A Review of Global Data 2013–2023

From 'Quit-Tok' to proximity bias, here are 11 buzzwords from the world of hybrid work

Kate Whiting

April 17, 2024

How to build the skills needed for the age of AI

Juliana Guaqueta Ospina

April 11, 2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.7(4); 2021 Apr

Job satisfaction behind motivation: An empirical study in public health workers

Associated data.

The data that has been used is confidential.

The health sector is characterized as labor-intensive, which means that the effectiveness of an organization that operates within its context is inextricably linked to the level of employee performance. Therefore, an essential condition, in order to achieve higher standards, in terms of the effectiveness of the health units, as well as set the foundations of a solid health system, is to take maximum advantage of the full potential of human resources. This goal can only be accomplished by providing the appropriate incentives, which will naturally cause the adoption of the desired attitude and behavior. In the case of Greece, there is not enough research relative to the needs of health workers and, consequently, the incentives that can motivate them. This article aims to investigate the dynamics that may be behind health workers at a public hospital in Northern Greece. Data were collected from 74 employees in the hospital and were analyzed using ANOVA analysis. The results show that key motivators for the employees can be considered the relationships with their colleagues and the level of achievement, while the level of rewards and job characteristics play a secondary role. These results make it clear that, in order for the hospital's management to be able to improve the level of employee performance, it should ensure the establishment of a strong climate among employees, and also acknowledge the efforts made by them.

Motivation; Job satisfaction; Performance; Health personnel; Healthcare.

1. Introduction

The field of health is particularly complex as it focuses on the provision of health services, which are mainly produced by the human resources that staff the health units. The quality of the services under study is largely determined by the behavior of health workers as a result of their efforts ( Musinguzi et al., 2018 ). For this reason, the administrations of the health units must give great importance to the utilization of the human factor, to increase their effectiveness and, consequently, the effectiveness of the health units. In order for healthcare workers to be efficient and provide patients with superior quality services, the followings are necessary: health workers must have clear expectations of the subject of their work and their work environment, they must have the appropriate knowledge and skills needed for their work, they must have access to necessary equipment, receive feedback on their performance and have a supervisor who motivates them. More simply, healthcare workers need incentives to motivate them in order for them to satisfy patients and increase their effectiveness ( Hotchkiss et al., 2015 ; Huber and Schubert, 2019 ; Schopman et al., 2017 ).

Even in those cases where health workers do not have the proper means and equipment, incentives given to them seem to help them overcome these problems and attend to patients to the fullest. Popa and Popescu (2013) and Rossidis et al. (2016) argue that meeting the needs of employees through the provision of incentives is a powerful tool that administrations can use to motivate them and increase their productivity. This is an element that all health organizations should take advantage of, as this can help them to deal with and overcome serious problems that limit their effectiveness ( Borst et al., 2020 ; Valdez and Nichols, 2013 ). In this context, it is important to state that motivating healthcare workers is an urgent need as it increases their performance and consequently increases the efficiency of the services provided as well as patients’ satisfaction ( Hotchkiss et al., 2015 ; Rubel et al., 2020 ).

The present research aims to examine the factors that may motivate employees at a public hospital in Northern Greece. The need to provide incentives for healthcare workers in order to increase their performance is urgent, as the health systems of several countries have been severely affected bythe global financial crisis, which must be overcome. Reducing the number of health care workers coupled with shortages of material and technological equipment limits the efficiency and effectiveness of health care units, making it necessary for their administrations to look for a way out. The management of health units, in order to achieve effective management of available resources and produce higher quality health services, must make the best use of the human factor.

Essentially, the administrations of the Greek health units must design realistic incentive programs for their employees so that they can increase their efficiency. The provision of incentives to health workers is necessary for them to meet their needs. This means that healthcare management needs to know what motivates its staff to meet their needs and also needs to know whether their needs differ based on their personality type and profession. The results of this work are expected to be particularly useful and collaborate with other research work done during the last years of the economic crisis on the needs of health employees and knowing the incentives that can motivate them.

The research questions posed for the present research work to answer are:

- 1. What are the internal factors that motivate health professionals and the administrative staff of the hospital?

- 2. What are the external factors that motivate health professionals and the administrative staff of the hospital?

This paper is divided into sections: section 1 introduction of the subject, section 2 presents the theoretical background about the motivation of healthcare workers. Section 3 is the methodology, Section 4 presentation of research findings and Section 5 comments on the research results and the conclusions of the study.

2.1. Hospital management

The management of hospitals is very important for their proper functioning. It is also worth noting that hospital management differs from that of other sectors. Additionally, there are important differences between the management of private and public hospital management. The main goal of the management of private health units is to achieve profit and reduce costs and required resources. On the other hand, the main purpose of public hospitals is to promote and provide health services to all citizens without discrimination and exclusion criteria. There is also a great deal of effort in public hospitals to increase the quality of services provided, which often leads to a waste of available resources, creating problems for public health units ( Masango-Muzindutsi et al., 2018 ; Musinguzi et al., 2018 ).

In public hospitals, due to the difficult economic conditions prevalent in this country, there are problems in the quality of services provided. Great efforts are being made to reduce the cost of health services without quality being compromised. The measures taken by governments include attempts to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of public organizations, and rational use of the limited resources available. Thus, it is necessary to have the appropriate management in the health sector, which will be able to use resources rationally and in particular to coordinate the human resources in the most effective way to increase the quality of services provided in public health units ( Aysen and Parumasur, 2011 ; Liu et al., 2015 ). Also, in modernizing the administration of the public health units, efforts should be made to eliminate the pathogenesis of the Greek health system and reduce its weaknesses that have existed for years. It is worth noting that the management of public hospitals should be free from influences such as government policy so that it can carry out its work in the best possible way and be guided by the social interest and service of the citizens.

It has been found that leadership is very important in creating the necessary conditions within an organization to successfully achieve its goals. In essence, leadership is influenced by the reactions and behaviors of employees in relation to organizational change, the performance of the business as a whole, job satisfaction of staff and the culture that prevails within an organization. A leader, based on his values and characteristics, can positively or negatively affect employees and their behavior. Every leader, based on his or her skills and abilities, makes appropriate decisions and influences the way employees work and is also responsible for the elimination and proper management of conflicts and issues that may arise in the business ( Belrhiti et al., 2020 ; Curtis & O'Connell, 2011 ).

If a leader is effective, he or she can create an attractive vision for employees and inspire them to pursue and work toward the success of their goals. Also, a leader is effective when he can motivate his subordinates and make them committed to achieving their goals. Other actions of an effective and successful leader include the creation of performance and reward criteria, and the creation of effective teams and modes of communication between employees ( Musinguzi et al., 2018 ; Rubel et al., 2020 ).

Several factors have been reported to increase the job satisfaction of health care workers. One of the factors that contribute to the increase in staff satisfaction is their salary and wages. In fact, due to the pathogenesis of the Greek health system as well as their economic crisis and cuts in health care expenditures, there have been reductions in staff's salaries, invalid payments of medical and nursing staff and non-payment of various allowances in this profession. These factors lead to a reduction in healthcare staff's job satisfaction ( Halldorsdottir et al., 2018 ; Kontodimopoulos et al., 2009 ).

To improve the job satisfaction of medical and nursing staff as well as productivity, there could be some level of reward. Thus, each health care worker could be more productive if there is a corresponding reward that would lead to an increase in his/her job satisfaction. This can make the entire performance of the whole health unit to increase, which in turn would increase the quality of services provided ( Borst et al., 2020 ; Kontodimopoulos et al., 2009 ; Rubel et al., 2020 ).

Equally important is the fact that there is an increased sense of job satisfaction in workers at health organizations and a sense of justice within the unit. Meritocracy, objective judgment on promotions and salary increases, rational division of duties and work within the unit, fair distribution of shifts and impartial attitude of the administration are significant factors that can influence job satisfaction of nursing and medical staff ( Kontodimopoulos et al., 2009 ; Schopman et al., 2017 ). These factors can contribute to the increase in employees’ satisfaction, and as will be analyzed in the next section, they can also be incentives for employees in health units.

Other important factors that can lead to increased job satisfaction of healthcare workers are factors related to working conditions and the work environment. In particular, these factors include the existence of comfortable and functional workplaces and staff rest, the existence of appropriate equipment and consumables and the relationships among employees and those between employees with management. The factors that boost job satisfaction of medical and nursing staff include good communication that should be reciprocal, teamwork, and cooperation as well as the existence of good relations and respect within the health unit ( Kontodimopoulos et al., 2009 ; Schopman et al., 2017 ).

Another factor that increases the job satisfaction of healthcare employees is the acknowledgment of their work and appreciation they receive from their colleagues, management and patients. When the work of employees is acknowledged, they have increased levels of job satisfaction ( Borst et al., 2020 ; Lambrou et al., 20 , 10 ). Aside the acknowledgment of their work, employees are highly satisfied with their job when there are opportunities for development and growth within the health unit ( Lambrou et al., 2010 ). There is a need for these conditions to be present in the health units to increase the job satisfaction of their staff.

Other important factors that increase employees’ job satisfaction include the assignment of important responsibilities to them and allowing them to participate in the decision-making process ( Lambrou et al., 2010 ; Schopman et al., 2017 ). This will make them to feel that it is important to carry out important decisions and actions within the unit, thereby increasing their job satisfaction. From the above, the management and the leadership in each health unit should take into account the factors that can increase the job satisfaction of their employees. In this way, they will be able to increase their efficiency and productivity and make the health unit work much more efficient and successful, increasing the satisfaction of health service users.

2.2. Encouraging healthcare workers

In recent years, the interest in motivating health workers has been particularly strong as it seems to be crucial to the quality and effectiveness of the services provided. Rosak-Szyrocka (2015) argues that motivating health workers is a necessary and important process as it ensures their commitment both to their organization and the work they produce. As a result, the quality of the work of health and administrative staff is increasing. Therefore, it is expected that patients will receive not only satisfaction from the services they receive but also from the relationships they develop with doctors, nurses and the administrative staff of the health units. The effect of health workers' motivation on the quality of health care provided to patients is also confirmed by Alhassan et al. (2013) and Babic et al. (2014) . In particular, Alhassan et al. (2013) , through their research, showed that health workers who are not motivated by the administrations of the health units in which they are employed are very likely to provide unsafe health services.

Tsounis et al. (2013) , through a literature review, concluded that healthcare workers may not perceive incentives the way employees in other sectors do. They also argue that the individual categories of healthcare workers can be motivated in different ways and degrees due to their different needs and requirements. Typically, financial rewards are not an incentive for doctors to increase their performance. This is contrary to what happens in many different industries and also with other categories of healthcare workers. Instead, doctors seem to be motivated when they meet their goals and are acknowledged by both hospital management and their colleagues.

Identifying the factors that motivate healthcare workers has also been a significant subject of research by Babic et al. (2014) . They tried to identify whether there are differences between the incentives that motivate employees in the private health sector and those in the public health sector. The results of the survey showed that not all employees are motivated by material rewards as they are very low and employees in the private sector are positively motivated by the existence of security conditions. Also, in both private and public sectors, healthcare workers seem to be positively motivated by peer relationships and the support that develops between them. In contrast, employees in both private and public sectors do not seem to be satisfied with the way their superiors assess them, which does not help to motivate them. The results are moving in the same direction regarding the development incentives provided to both private and public health sectors, which are very limited and cannot motivate healthcare workers to increase their performance ( Mariappan, 2013 ).

Bhatnagar et al. (2017) argue that various motivations can lead to the promotion of healthcare workers, which can be either internal or external. Characteristically, they argue that their faith, values and self-efficacy are internal factors that influence or motivate them; economic gains and working conditions are external motivations that can affect their performance. Lambrou et al. (2010) , in their study, tried to investigate the factors that can motivate healthcare workers to adopt the desired behavior. The results of the research showed that salary, the relations between the colleagues as well as the nature of the work, are the determining factors of their motivation.

Hotchkiss et al. (2015) also researched on the incentives that health unit administrations can provide to employees to increase their effectiveness. They found that being motivated by both internal and external factors influences the effectiveness of workers. More specifically, employees' self-efficacy and self-esteem are two of the main internal motivations that motivate healthcare workers. It also emerged that in Ethiopia, healthcare workers’ satisfaction with their financial earnings, working conditions and relationships with their colleagues are the main external motivations that can motivate them.

Dagne et al. (2015) conducted another study in Ethiopia that tried to explain the factors that drive healthcare workers. The results of this research showed that healthcare workers are primarily motivated by their superiors and the relationship they create with them, by financial rewards, the nature of the work and the tasks they undertake and the location of the hospital where they work.

In addition, Shah et al. (2016) , in their research, concluded that the main factors that can motivate employees in the field of health are the safety of the work environment, recognition and rewarding of their work, provision of incentives and the possibility of their development within work.

Janus et al. (2008) identified various incentives that can be offered by healthcare unit management so that healthcare workers can be motivated and increase their effectiveness. Such incentives are participation in the decision-making process, participation in educational programs, the existence of security conditions in the work environment, good relations between colleagues as well as fair treatment given by their superiors. However, the most important incentives seem to be the financial rewards provided to healthcare workers by the management of health facilities ( Alotaibi et al., 2016 ; Halldorsdottir et al., 2018 ).

In a bid to examine the importance of motivating health workers in Greece, Gaki et al. (2013) investigated the factors that can motivate the nurses of Greek hospitals. The study involved 200 nurses who argued that they cannot be motivated only by material rewards (financial rewards) but also by factors that contribute to their personal and professional development. They also argued that their motivating factor is the job satisfaction they receive both from the exercise of their duties and from the conditions prevailing in their work environment. Holmberg et al. (2016) found the same results in a survey conducting in a Swedish clinical nursing staff.

2.3. Differentiation of incentives according to the personal and professional characteristics of health workers

A particularly interesting study is that of Rosak-Szyrocka (2015) , which makes it clear that gender is a significant factor in differentiating the health needs of workers and therefore the motivations of those who positively influence their behavior. More specifically, he argues that perceptions and social stereotypes affect their needs and thus seek different motivations to be able to be motivated. Lambrou et al. (2010) to this; it makes it clear that female health workers are more easily motivated by salary compared to men. Goncharuk (2018) found that the most significant motivator for women is salary but for men is the characteristics of their job.

Like the above researchers, Shah et al. (2016) found that there is a difference between the factors that motivate women and men who work in the health sector, making it clear that motivating women is a more difficult process. Like gender, the age of healthcare workers seems to be a determining factor in differentiating the motivations that can lead to the promotion of healthcare workers ( Gaki et al., 2013 ; Kantek et al., 2015 ; Park and Lee, 2020 ). Contrary to the above research, the research of Babic et al. (2014) did not identify the existence of different needs between the sexes. Babic et al. (2014) concluded that demographic characteristics do not affect employees' views on those factors that may affect their performance and actually motivate them. Similarly Dagne et al. (2015) found no significant statistical relationship between the demographic characteristics of the sample and the factors that motivate them.

The study led by Toode et al. (2015) provided additional support for the assertion that demographic factors for example age, working experience, position and educational training influence nurses’ motivation. They found that older and more tenured nurses were more probable motivated by external reasons. For managers, this is a particularly significant outcome to underline and brings up the issue of how to help and keep up intrinsic motivation when staff get older and have worked longer in medical care. Another important outcome is that workers who have had received limited training during the most recent years were less motivated than colleagues who were accomplished. Concerning family life, having children and whether the staff members lived alone or with a partner had no relation to their work motivation.

It is also important to note that the position of employees in the health unit affects their needs and requires the formation of different policies on the part of management to motivate them. Tsounis et al. (2013) argue that physicians are motivated by different factors and motivations compared to nurses and administrative staff. Similarly, Lambrou et al. (2010) showed that nurses are more interested in motivations that relate to material rewards than physicians who are interested in other motivations as stated earlier on. The highest ranked factor for nurses’ motivation is “achievements” according to Grammatikopoulos et al. (2013) which conducted in Greece.

The following hypotheses have been identified on the basis of existing studies:

Job related factors positively affect healthcare professionals' satisfaction.

Factors related to salary positively affect healthcare professionals' satisfaction.

Factors related to relationships with colleagues positively affect healthcare professionals' satisfaction.

Factors related to work achievements positively affect healthcare professionals' satisfaction.

3. Materials and methods

The research is carried out on the employees of a public hospital in Northern Greece and specifically, on the administrative employees, nurses and doctors. This means that the research population is the staff of the hospital under study, which amounts to 947 people. The study involved 74 hospital staff as the number of correctly completed questionnaires collected. It is important to note that 150 questionnaires were distributed, of which 11 were incorrectly completed and 65 were not completed at all, indicating a relatively high reluctance to participate in the survey.

The questionnaire is based on Paleologou et al. (2006) and it includes 4 categories of factors in order to examine the level of workers’ motivation in healthcare. These factors are related to job, salary, relationships with colleagues and work achievements. A 5point Likert ordinal satisfaction scale was used. Appendix displays the items as they appeared in the survey. Data were analyzed using ANOVA.

This paper does not involve chemicals; procedures or equipment that have any unusual hazards inherent in their use. Furthermore, it does not include experiments that may raise biosecurity concerns or human subjects or a clinical trial. Finally, the paper does not involve experimentation on animals.

Majority of the 74 employees were women (n = 60, 81.08%) while a smaller percentage were men (n = 14, 18.92%). 37.84% (n = 28) of the participants were aged 36–45 years, 36.48% (n = 27) of the participants were aged 46–55 years, 17.57% (n = 13) of the participants were aged 26–35 years and 8.11% (n = 6) of the participants were aged 18–25 years. 43.24% (n = 32) of the participants were graduates form Technological Institutes, 29.73% (n = 22) of the participants were high school graduates, 8.11% (n = 6) were postgraduate degree holders, 4.05% (n = 3) were graduates from Universities, 2.7% (n = 2) were school graduates and only 12.16% (n = 9) stated another level of education. The vast majority were health professionals (n = 73, 98.65%) and only 1 person (1.35%) was an executive staff ( Table 1 ).

Table 1

Descriptive statistics of the sample.

Internal consistency was calculated via Cronbach's alpha with the minimum requirement of 0.70 ( Newkirk et al., 2003 ). The Cronbach's alpha coefficient values for the variables are calculated in Table 2 .

Table 2

Reliability analysis of the questionnaire items.

The outcomes of Pearson's correlation analysis done to ascertain the level and type (direct or inverse) of relationship amongst the variables are presented in Table 3 .

Table 3

Correlation matrix.

From the normal P–P and scatter plots ( Figure 1 ), the data are usually distributed (all residuals cluster around the ‘line’) and conform with the assumptions of homogeneity of variance (homo-scedasticity) and linearity. The residual errors are evenly spread and not linked to the predicted value, thereby suggesting that the correlation is linear, and the variance of y is the same among all values of x, which supports the homoscedasticity assumption ( Kachigan, 1991 ). Z-score was used to evaluate the univariate outliers and all values were within the acceptable range. Mahalanobis and Cook's distances were used to evaluate the multivariate outliers. No influential outliers were identified. Variance inflation factors (VIFs) was used to evaluate Multicollinearity.

Standard P–P plot of the regression standardized residual and a residual scatter plot.

Table 4 presents the regression coefficients and the results of hypothesis testing. The path coefficient between job factors and satisfaction was negative and not statistically significant (β = -0.008, p > 0.05). Therefore, H1 was not supported. There was a negative and not statistically relationship between the factors that are related to salary and satisfaction (β = -0.012, p > 0.05). Therefore, H2 was not supported. There was a negative and not statistically significant relationship between the factors that are related to relationship with colleagues and satisfaction (β = -0.186, p > 0.05). Thus, H3 was not supported. There was a positive and statistically significant relationship between the factors that are related to work achievements and satisfaction (β = 0.577, p < 0.05). Thus, H4 was supported.

Table 4

Regression analysis between independent variables and dependent variable.

∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001.

5. Discussion

The findings show that the majority of the sample is moderately satisfied with the exercise of power within the hospital as well as moderately satisfied with the clarity of their work objectives. However, it should be noted that there is a significant percentage of respondents who are not at all satisfied with the clarity of their work goals. This raises significant concerns as these employees do not have a goal to guide their actions and behavior. Also, a large part of the sample states moderate to good satisfaction with the clarity of their duties, but again several employees do not seem to understand what their obligations are.

The majority of the survey participants are moderately satisfied with the safety of their work environment. A large part of the participants believes that their potential cannot be maximized as they are not provided with the appropriate opportunities. Regarding the satisfaction they receive from the conditions prevailing in the work environment of the hospital, majority of the sample statement is very satisfied, which is very encouraging as it seems that there is a positive atmosphere; however, all the employees are not very satisfied with the resources of the hospital in order to be able to perform their work.

Regarding the possibilities of personal and professional development through the educational programs provided to the employees of the hospital, majority of the sample and specifically almost half of the participants expressed moderate satisfaction. This makes it clear that there are significant opportunities for improvement as job development and training opportunities must be provided to employees in order to improve their skills and abilities. Also, it seems that most of the participants are moderately satisfied with the ability to exercise control over the decisions made and with the ability to participate in the decision-making process. In this regard, with the satisfaction that employees receive from their job position, several employees show little satisfaction, several employees who show great satisfaction and finally many who show great satisfaction.

Of particular interest are the views of employees at the Hospital regarding the satisfaction they receive with the achievements they make. Typically, majority of the sample claim to be moderate to very satisfied with the importance of their work as well as the levels of respect that exist between hospital staff. A large part of the participants claims that they receive moderate to significant satisfaction from the recognition of the efforts they make and the achievements they make. However, majority of the participants believe that there are no suitable opportunities for personal growth and development in the hospital. Of particular interest is the finding of satisfaction with the incentive effort adopted by the administration as the majority of the sample is not at all satisfied with this process or is at least satisfied with it. This is a finding that makes it necessary to change the attitude and behavior of management regarding the way employees are treated as they need to adopt more effective techniques that will contribute to their effective motivation.

The satisfaction of the participants in this study regarding the external incentives provided to them, in particular, the remuneration they receive and their relations with their colleagues was investigated. The results showed that majority of the sample are not at all even slightly satisfied with the financial earnings they receive and moderately satisfied with the benefits of pension and insurance coverage. However, they are moderately satisfied with their work environment and not at all satisfied with the policies for dealing with absenteeism.

In contrast to the above incentive categories, where there seems to be overall moderate satisfaction, in the case of relationships with colleagues, the results differ significantly: majority of the sample are moderate to very satisfied with the interpersonal relationships developed in their work, by the existence of a spirit of teamwork and cooperation, stimulation of pride and respect, appreciation of the role of employees, the support they receive from supervisory staff and supervisors, the fair treatment they receive and the ability they have to express themselves creatively. Finally, most of the hospital staff members are very satisfied with their relationship with their colleagues ( Ayalew et al., 2019 ; Belrhiti et al., 2020 ; Chmielewska et al., 2020 ; Huber and Schubert, 2019 ).

Regarding the results of those factors that drive hospital staff, it became clear that the main factor is the relationship with their colleagues and the achievements that follow. Both the salary and the characteristics of the job position are not the main motivating factors for the employees at the hospital. Similarly, Hotchkiss et al. (2015) and Lambrou et al. (2010) found that relationships between colleagues are a major motivator for health workers. The finding that differs from the aforementioned surveys concerns their remuneration which seems to be a key motivating factor, which is not confirmed by this research.

The increase in hospitalization and the prices of medicines and the reductions in the state health budget have led to significant problems in the health sector. Citizens can no longer afford private insurance thereby increase the workload in public hospitals. Unemployment has also risen. There is an increased social exclusion of the unemployed or those who do not have a job, leading to increased psychological disorders of individuals. Unemployment has even led to an increase in illness and psychological problems, as well as the number of disability and suicide cases. Thus, the public sector cannot effectively meet the health needs of citizens in a quality manner ( Potipiroon and Faerman, 2020 ). Respectively, health professionals cannot meet the particularly high needs of citizens and therefore their job satisfaction is reduced; there is also a strong brain drain phenomenon, during which many health professionals go abroad.

It is also important to mention that the process of financing the Greek public sector cannot meet the ever-increasing needs that exist, and therefore the proper functioning of public hospitals is affected. In fact, due to the shortages of material, consumables and equipment, the work of health professionals has become much more difficult in recent years ( Stuckler et al., 2009 ). Also, the economic crisis has led to a reduction in the income of citizens which has in turn led to a restriction on the use of health services by citizens, increasing the workload in public Greek hospitals. Thus, the pathogenesis of the Greek health system combined with the reduction of state health budgets has led to even more problems for health professionals and a reduction in job satisfaction. There is a need to provide the right incentives to increase the quality of health services.

6. Conclusion

The aim of this paper was to investigate internal and external factors that may motivate employees at a public hospital in Northern Greece. The results of this paper point out that without a strong motivational plan, the inner incentive of hospital nurses to work can become an extrinsic motivation over time. Managers should recognize and note when their nursing staff, who have been dedicated to self-focused for many years, require additional help or improvement in their position and be sensitive to giving them the extra assistance they may need to stay effective and independent.

The results of this paper can be used by the hospital to formulate more effective strategies, as they show that health workers are not fully satisfied with the prevailing conditions and that improvements need to be made to produce better quality health services. As it turned out, healthcare workers are not particularly happy with the level of knowledge of the strategic goals of healthcare units and their tasks, as well as the opportunities given to them to participate in decision-making processes and to develop personally and professionally. This means that the administrations will have to adopt a different leadership that will emphasize the needs of the employees and allows them to develop a more active role within the health unit. They should also encourage the creation of educational programs and create conditions for development so that hospital employees know that their work encourages their development and gives them opportunities for advancement.

It also became clear that hospital staff is more motivated by the good relations that exist between colleagues. This means that the management of the hospital should ensure in every way that there is a positive atmosphere of cooperation between its staff members and that there is a strong element of mutual support. It must look for all ways to create harmonious cooperation among members of the organization as well as strong interpersonal relationships and ties. Otherwise, employees cannot be productive and will not be able to provide quality health services, which are necessary for the citizens of the country, especially in such a difficult time.

The results of this work are of great interest, but cannot be generalized to the entire population of hospital staff as the sample involved in the study came from only one hospital in the country. It should also be noted that the results of the survey were obtained from a small sample of participants. These data make it clear that it is necessary to conduct a future survey of a larger population of health workers, from different parts of the country, to determine the situation in the whole country and to investigate the factors that motivate the staff to acquire the appropriate attitude and behavior needed for work. Through such future research, all hospital administrations in the country will know the needs of their employees as well as what motivates them. Besides, the paper gives some useful materialness to inspect medical attendants' work inspiration qualities. The questionnaire can be used to design a number of effective interview methods and spotlight on explicit individual mediations that can build the degree of motivation in a specific position or work unit.

Declarations

Author contribution statement.

Maria Kamariotou: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Fotis Kitsios: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

Declaration of interests statement.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Please mark the number to indicate the extent to which you are satisfied with the following factors.

- Alhassan R.K., Spieker N., vanOstenberg P., Oging A., Nketiah-Amponsah E., RinkedeWit T. Association between health worker motivation and healthcare quality efforts in Ghana. Hum. Resour. Health. 2013; 11 (37):2–11. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alotaibi J., Paliadelis P.S., Valenzuela F.R. Factors that affect the job satisfaction of Saudi Arabian nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016; 24 (3):275–282. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ayalew F., Kibwana S., Shawula S., Misganaw E., Abosse Z., Van Roosmalen J., Stekelenburg J., Kim Y.M., Teshome M., Mariam D.W. Understanding job satisfaction and motivation among nurses in public health facilities of Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nurs. 2019; 18 (1):1–13. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aysen G., Parumasur S.B. Managerial role in enhancing employee motivation in public health care. Corp. Ownersh. Control. 2011; 8 :401–410. [ Google Scholar ]

- Babic L., Kordic B., Babic J. Differences in motivation of health care proffessionals in public and private health care centers. SJAS. 2014; 11 (2):45–53. [ Google Scholar ]

- Belrhiti Z., Van Damme W., Belalia A., Marchal B. Unravelling the role of leadership in motivation of health workers in a Moroccan public hospital: a realist evaluation. BMJ open. 2020; 10 (1):1–17. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bhatnagar A., Gupta S., Alonge O., Asha G. Primary health care workers' views of motivating factors at individual, community and organizational levels: a qualitative study from Nasarawa and Ondo states, Nigeria. Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 2017; 32 (2):217–233. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Borst R.T., Kruyen P.M., Lako C.J., de Vries M.S. The attitudinal, behavioral, and performance outcomes of work engagement: a comparative meta-analysis across the public, semipublic, and private sector. Rev. Publ. Person. Adm. 2020; 40 (4):613–640. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chmielewska M., Stokwiszewski J., Filip J., Hermanowski T. Motivation factors affecting the job attitude of medical doctors and the organizational performance of public hospitals in Warsaw, Poland. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020; 20 :1–12. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Curtis E., O’Connell R. Essential leadership skills for motivating and developing staff. Nurs. Manag. 2011; 18 (5):32–35. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dagne T., Beyen W., Berhanu N. Motivation and factors affecting it among health professionals in the public hospitals, Central Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2015; 25 (3):231–242. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gaki E., Kontodimopoulos N., Niakas D. Investigating demographic, work-related and job satisfaction variables as predictors of motivation in Greek nurses. J. Nurs. Manag. 2013; 21 (3):483–490. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goncharuk A.G. Exploring a motivation of medical staff. Int. J. Health Plann. Manag. 2018; 33 (4):1013–1023. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Grammatikopoulos I.A., Koupidis S.A., Moralis D., Sadrazamis A., Athinaiou D., Giouzepas I. Job motivation factors and performance incentives as efficient management tools: a study among mental health professionals. Arch. Hellenic Med. 2013; 30 (1):46–58. [ Google Scholar ]

- Halldorsdottir S., Einarsdottir E.J., Edvardsson I.R. Effects of cutbacks on motivating factors among nurses in primary health care. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2018; 32 (1):397–406. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Holmberg C., Sobis I., Carlström E. Job satisfaction among Swedish mental health nursing staff: a cross-sectional survey. Int. J. Publ. Adm. 2016; 39 (6):429–436. [ Google Scholar ]

- Hotchkiss D., Bantayerna H., Tharaney M. Job satisfaction and motivation among public sector health workers: evidence from Ethiopia. Hum. Resour. Health. 2015; 13 (83):1–12. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Huber P., Schubert H.J. Attitudes about work engagement of different generations—a cross-sectional study with nurses and supervisors. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019; 27 (7):1341–1350. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Janus K., Amelung V.E., Baker L.C., Gaitanides M., Schwartz F.W., Rundall T.G. Job satisfaction and motivation among physicians in academic medical centers: insights from a cross-national study. J. Health Polit. Pol. Law. 2008; 33 (6):1133–1167. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kachigan S.K. second ed. Radius Press; Santa Fe: 1991. Multivariate Statistical Analysis: A Conceptual Introduction. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kantek F., Yildirim N., Kavla İ. Nurses’ perceptions of motivational factors: a case study in a Turkish university hospital. J. Nurs. Manag. 2015; 23 (5):674–681. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kontodimopoulos N., Paleologoy V., Niakas D. Identifying motivational factors for professionals in Greek hospitals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2009; 9 (1):1–11. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lambrou P., Kontodimopoulos N., Niakas D. Motivation and job satisfaction among medical and nursing staff in a Cyprus public general hospital. Hum. Resour. Health. 2010; 8 (1):1–9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu B., Yang K., Yu W. Work-related stressors and health-related outcomes in public service: examining the role of public service motivation. Am. Rev. Publ. Adm. 2015; 45 (6):653–673. [ Google Scholar ]

- Mariappan M. Analysis of nursing job characteristics in public sector hospitals. J. Health Manag. 2013; 15 (2):253–262. [ Google Scholar ]

- Masango-Muzindutsi Z., Haskins L., Wilford A., Horwood C. Using an action learning methodology to develop skills of health managers: experiences from KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2018; 18 (1):1–9. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Musinguzi C., Namale L., Rutebemberwa E., Dahal A., Nahirya-Ntege P., Kekitiinwa A. The relationship between leadership style and health worker motivation, job satisfaction and teamwork in Uganda. J. Healthc. Leader. 2018; 10 :21–32. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Newkirk H.E., Lederer A.L., Srinivasan C. Strategic information systems planning: too little or too much? J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 2003; 12 (3):201–228. [ Google Scholar ]

- Paleologou V., Kontodimopoulos N., Stamouli A., Aletras V., Niakas D. Developing and testing an instrument for identifying performance incentives in the Greek health care sector. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2006; 6 (1):118–128. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Park J., Lee K.H. Organizational politics, work attitudes and performance: the moderating role of age and public service motivation (PSM) Int. Rev. Psycho Anal. 2020; 25 (2):85–105. [ Google Scholar ]

- Popa I., Popescu D. Motivation in the context of global economic crisis. J. E. Eur. Res. Bus. Econ. 2013:1–13. 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Potipiroon W., Faerman S. Public Performance & Management Review; 2020. Tired from Working Hard? Examining the Effect of Organizational Citizenship Behavior on Emotional Exhaustion and the Buffering Roles of Public Service Motivation and Perceived Supervisor Support. (in press) [ Google Scholar ]

- Rosak-Szyrocka J. Employee motivation in health care. Product.Eng. Arch. 2015; 6 (1):21–25. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rossidis I., Aspridis G., Blanas N., Bouas K., Katsmarrdos P. Best practices for motivation and their implementation in the Greek public sector for increasing efficiency. Acad. J. Interdiscipl. Stud. 2016; 5 (3):144–150. [ Google Scholar ]

- Rubel M.R.B., Kee D.M.H., Rimi N.N. High-performance work practices and medical professionals' work outcomes: the mediating effect of perceived organizational support. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2020 (in press) [ Google Scholar ]

- Schopman L.M., Kalshoven K., Boon C. When health care workers perceive high-commitment HRM will they be motivated to continue working in health care? It may depend on their supervisor and intrinsic motivation. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017; 28 (4):657–677. [ Google Scholar ]

- Shah M.S., Zaidi S., Ahmed J., Rehman S. Motivation and retention of physicians in primary healthcare facilities: a qualitative study from abbottabad, pakista. Health Pol. Manag. 2016; 5 (8):467–475. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stuckler D., Basu S., Suhrckke M., Cooutts A., McKee M. The public health effect of economic crisis and alternative police responses in Europe: an empirical analysis. Lancet. 2009; 274 :315–323. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Toode K., Routasalo P., Helminen M., Suominen T. Hospital nurses' work motivation. Scand. J. Caring Sci. 2015; 29 (2):248–257. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tsounis A., Sarafis P., Bamidi P. Motivation among physicians in Greek public health-care sector. Br. J. Med. Med. Res. 2013; 4 (5):1094–1105. [ Google Scholar ]

- Valdez C., Nichols T. Motivating healthcare workers to work during a crisis: a literature review. J. Manag. Pol. Pract. 2013; 14 (4):43–51. [ Google Scholar ]

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Job satisfaction, organizational commitment and job involvement: the mediating role of job involvement.

- Department of Industrial Engineering and Management, Faculty of Technical Sciences, University of Novi Sad, Novi Sad, Serbia

We conducted an empirical study aimed at identifying and quantifying the relationship between work characteristics, organizational commitment, job satisfaction, job involvement and organizational policies and procedures in the transition economy of Serbia, South Eastern Europe. The study, which included 566 persons, employed by 8 companies, revealed that existing models of work motivation need to be adapted to fit the empirical data, resulting in a revised research model elaborated in the paper. In the proposed model, job involvement partially mediates the effect of job satisfaction on organizational commitment. Job satisfaction in Serbia is affected by work characteristics but, contrary to many studies conducted in developed economies, organizational policies and procedures do not seem significantly affect employee satisfaction.

1. Introduction

In the current climate of turbulent changes, companies have begun to realize that the employees represent their most valuable asset ( Glen, 2006 ; Govaerts et al., 2011 ; Fulmer and Ployhart, 2014 ; Vomberg et al., 2015 ; Millar et al., 2017 ). Satisfied and motivated employees are imperative for contemporary business and a key factor that separates successful companies from the alternative. When considering job satisfaction and work motivation in general, of particular interest are the distinctive traits of these concepts in transition economies.

Serbia is a country that finds itself at the center of the South East region of Europe (SEE), which is still in the state of transition. Here transition refers to the generally accepted concept, which implies economic and political changes introduced by former socialist countries in Europe and beyond (e.g., China) after the years of economic stagnation and recession in the 1980's, in the attempt to move their economy from centralized to market-oriented principles ( Ratkovic-Njegovan and Grubic-Nesic, 2015 ). Serbia exemplifies many of the problems faced by the SEE region as a whole, but also faces a number of problems uniquely related to the legacy of its past. Due to international economic sanctions, the country was isolated for most of the 1990s, and NATO air strikes, related to the Kosovo conflict and carried out in 1999, caused significant damage to the industry and economy. Transitioning to democracy in October 2000, Serbia embarked on a period of economic recovery, helped by the introduction of long overdue reforms, major inflows of foreign investment and substantial assistance from international funding institutions and others in the international community. However, the growth model on which Serbia and other SEE countries relied between 2001 and 2008, being based mainly on rapid capital inflows, a credit-fueled domestic demand boom and high current account deficit (above 20% of GDP in 2008), was not accompanied by the necessary progress in structural and institutional reforms to make this model sustainable ( Uvalic, 2013 ). The central issue of the transition process in Serbia and other such countries is privatization of public enterprises, which in Serbia ran slowly and with a number of interruptions, failures and restarts ( Radun et al., 2015 ). The process led the Serbian industry into a state of industrial collapse, i.e., deindustrialization. Today there are less than 400,000 employees working in the industry in Serbia and the overall unemployment rate exceeds 26% ( Milisavljevic et al., 2013 ). The average growth of Serbia's GDP in the last 5 years was very low, at 0.6% per year, but has reached 2.7% in 2016 ( GDP, 2017 ). The structure of the GDP by sector in 2015 was: services 60.5%, industry 31.4%, and agriculture 8.2% ( Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, 2017 ).

Taking into account the specific adversities faced by businesses in Serbia, we formulated two main research questions as a starting point for the analysis of the problem of work motivation in Serbia:

1. To what extent are the previously developed models of work motivation (such as the model of Locke and Latham, 2004 ) applicable to the transition economy and business practices in Serbia?

2. What is the nature of the relationships between different segments of work motivation (job satisfaction, organizational commitment, job involvement and work characteristics)?

The Hawthorn experiment, conducted in early 1930s ( Mayo, 1933 ), spurred the interest of organizational behavior researchers into the problem of work motivation. Although Hawthorn focused mainly on the problems of increasing the productivity and the effects of supervision, incentives and the changing work conditions, his study had significant repercussions on the research of work motivation. All modern theories of work motivation stem from his study.

Building on his work, Maslow (1943) published his Hierarchy of Needs theory, which remains to this day the most cited and well known of all work motivation theories according to Denhardt et al. (2012) . Maslow's theory is a content-based theory , belonging to a group of approaches which also includes the ERG Theory by Alderfer (1969) , the Achievement Motivation Theory, Motivation-Hygiene Theory and the Role Motivation Theory.

These theories focus on attempting to uncover what the needs and motives that cause people to act in a certain way, within the organization, are. They do not concern themselves with the process humans use to fulfill their needs, but attempt to identify variables which influence this fulfillment. Thus, these theories are often referred to as individual theories , as they ignore the organizational aspects of work motivation, such as job characteristics or working environment, but concentrate on the individual and the influence of an individual's needs on work motivation.

The approach is contrasted by the process theories of work motivation, which take the view that the concept of needs is not enough to explain the studied phenomenon and include expectations, values, perception, as important aspects needed to explain why people behave in certain ways and why they are willing to invest effort to achieve their goals. The process theories include: Theory of Work and Motivation ( Vroom, 1964 ), Goal Setting Theory ( Locke, 1968 ), Equity Theory ( Adams, 1963 ), as well as the The Porter-Lawler Model ( Porter and Lawler, 1968 ).

Each of these theories has its limitations and, while they do not contradict each other, they focus on different aspects of the motivation process. This is the reason why lately they have been several attempts to create an integrated theory of work motivation, which would encompass all the relevant elements of different basic theories and explain most processes taking place within the domain of work motivation, the process of motivation, as well as employee expectations ( Donovan, 2001 ; Mitchell and Daniels, 2002 ; Locke and Latham, 2004 ). One of the most influential integrated theories is the theory proposed by Locke and Latham (2004) , which represents the basis for the study presented in this paper.

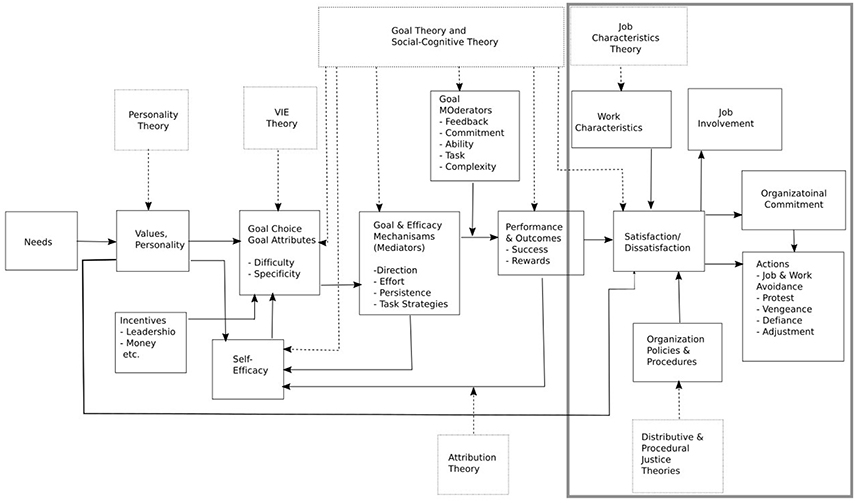

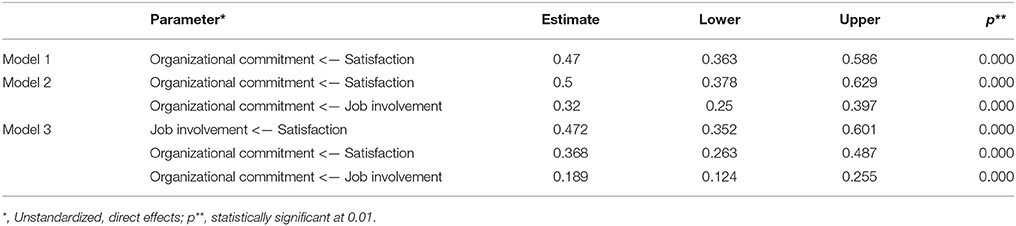

The model of Locke and Latham is show in Figure 1 . As the figure shows, it includes individual needs, values and motive, as well as personality. Incorporating the theory of expectations, the goal-setting theory and the social-cognitive theory, it focuses on goal setting, goals themselves and self-efficiency. Performance, by way of achievements and rewards, affects job satisfaction. The model defines relations between different constructs and, in particular, that job satisfaction is affected by the job characteristics and organizational policy and procedures and that it, in turn, affects organizational commitment and job involvement. Locke and Latham suggested that the theory they proposed needs more stringent empirical validation. In the study presented here, we take a closer look at the part of their theory which addresses the relationship between job satisfaction, involvement and organizational commitment. The results of the empirical study conducted in industrial systems suggest that this part of the model needs to be improved to reflect the mediating role of job involvement in the process through which job satisfaction influences organizational commitment.

Figure 1 . Diagram of the Latham and Locke model. The frame on the right indicates the part of the model the current study focuses on.

Job satisfaction is one of the most researched phenomena in the domain of human resource management and organizational behavior. It is commonly defined as a “pleasurable or positive emotional state resulting from the appraisal of oneś job or job experiences” ( Schneider and Snyder, 1975 ; Locke, 1976 ). Job satisfaction is a key element of work motivation, which is a fundamental determinant of one's behavior in an organization.

Organizational commitment, on the other hand, represents the degree to which the employees identify with the organization in which they work, how engaged they are in the organization and whether they are ready leave it ( Greenberg and Baron, 2008 ). Several studies have demonstrated that there is a strong connection between organizational commitment, job satisfaction and fluctuation ( Porter et al., 1974 ), as well as that people who are more committed to an organization are less likely to leave their job. Organizational commitment can be thought of as an extension of job satisfaction, as it deals with the positive attitude that an employee has, not toward her own job, but toward the organization. The emotions, however, are much stronger in the case of organizational commitment and it is characterized by the attachment of the employee to the organization and readiness to make sacrifices for the organization.

The link between job satisfaction and organizational commitment has been researched relatively frequently ( Mathieu and Zajac, 1990 ; Martin and Bennett, 1996 ; Meyer et al., 2002 ; Falkenburg and Schyns, 2007 ; Moynihan and Pandey, 2007 ; Morrow, 2011 ). The research consensus is that the link exists, but there is controversy about the direction of the relationship. Some research supports the hypothesis that job satisfaction predicts organizational commitment ( Stevens et al., 1978 ; Angle and Perry, 1983 ; Williams and Hazer, 1986 ; Tsai and Huang, 2008 ; Yang and Chang, 2008 ; Yücel, 2012 ; Valaei et al., 2016 ), as is the case in the study presented in this paper. Other studies suggest that the organizational commitment is an antecedent to job satisfaction ( Price and Mueller, 1981 ; Bateman and Strasser, 1984 ; Curry et al., 1986 ; Vandenberg and Lance, 1992 ).

In our study, job involvement represents a type of attitude toward work and is usually defined as the degree to which one identifies psychologically with one's work, i.e., how much importance one places on their work. A distinction should be made between work involvement and job involvement. Work involvement is conditioned by the process of early socialization and relates to the values one has wrt. work and its benefits, while job involvement relates to the current job and is conditioned with the one's current employment situation and to what extent it meets one's needs ( Brown, 1996 ).

2.1. Research Method

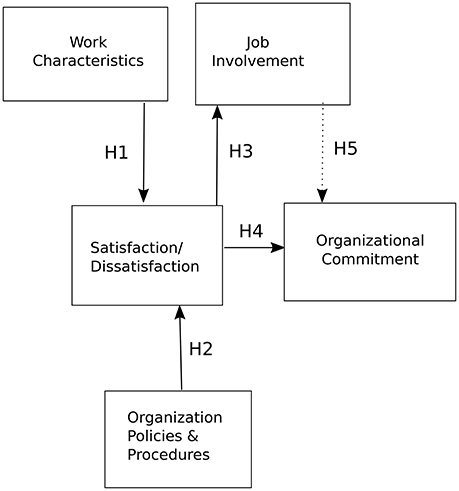

Based on the relevant literature, the results of recent studies and the model proposed by Locke and Latham (2004) , we designed a conceptual model shown in Figure 2 . The model was then used to formulate the following hypotheses:

H0 - Work motivation factors, such as organizational commitment, job involvement, job satisfaction and work characteristics, represent interlinked significant indicators of work motivation in the organizations examined.

H1 - Work characteristics will have a positive relationship with job satisfaction.

H2 - Organizational policies and procedures will have a positive relationship with job satisfaction.

H3 - Job satisfaction will have a positive relationship with job involvement.

H4 - Job satisfaction will have a positive relationship with organizational commitment.

H5 - Job involvement will have a mediating role between job satisfaction and organizational commitment.

Figure 2 . The research model.

2.2. Participants

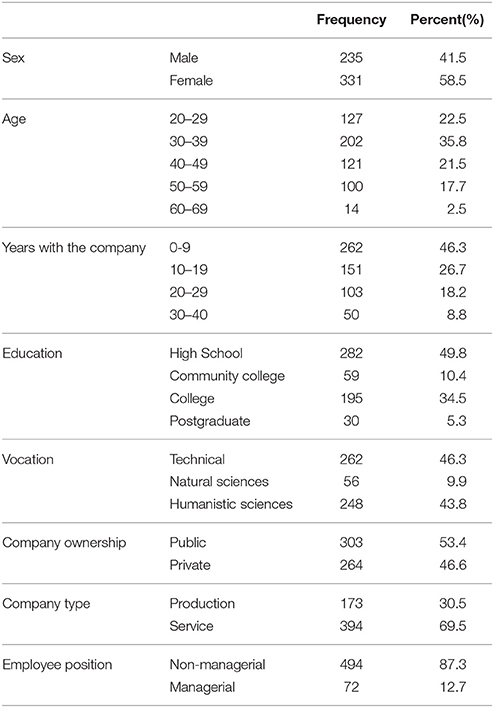

For the purpose of this study, 125 organizations from the Serbian Chamber of Commerce database ( www.stat.gov.rs ) were randomly selected to take part in this study. Each organization was contacted and an invitation letter was sent. Eight companies expressed a desire to take part and provided contact details for 700 of their employees. The questionnaire distribution process was conducted according to Dillman's approach ( Dillman, 2011 ). Thus, the initial questionnaire dissemination process was followed by a series of follow-up email reminders, if required. After a 2-month period, out of 625 received, 566 responses were valid. Therefore, the study included 566 persons, 235 males (42%) and 331 women (58%) employed by 8 companies located in Serbia, Eastern Europe.

The sample encompassed staff from both public (53%) and private (47%) companies in manufacturing (31%) and service (69%) industries. The companies were of varied size and had between 150 and 6,500 employees, 3 of them (37.5%) medium-sized (<250 employees) and 5 (62.5%) large enterprises.

For the sake of representativeness, the sample consisted of respondents across different categories of: age, years of work service and education. The age of the individuals was between 20 and 62 years of age and we divided them into 5 categories as shown in Table 1 . The table provides the number of persons per category and the relative size of the category wrt. to the whole sample. In the same table, a similar breakdown is shown in terms of years a person spent with the company, their education and the type of the position they occupy within the company (managerial or not).

Table 1 . Data sample characteristics.

2.3. Ethics Statement

The study was carried out in accordance with the Law on Personal Data Protection of the Republic of Serbia and the Codex of Professional Ethics of the University of Novi Sad. The relevant ethics committee is the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Technical Sciences of the University of Novi Sad.

All participants took part voluntarily and were free to fill in the questionnaire or not.

The questionnaire included a cover sheet explaining the aim of the research, ways in which the data will be used and the anonymous nature of the survey.

2.4. Measures

This study is based on a self reported questionnaire as a research instrument.

The questionnaire was developed in line with previous empirical findings, theoretical foundations and relevant literature recommendations ( Brayfield and Rothe, 1951 ; Weiss et al., 1967 ; Mowday et al., 1979 ; Kanungo, 1982 ; Fields, 2002 ). We then conducted a face validity check. Based on the results, some minor corrections were made, in accordance with the recommendations provided by university professors. After that, the pilot test was conducted with 2 companies. Managers from each of these companies were asked to assess the questionnaire. Generally, there were not any major complaints. Most of the questions were meaningful, clearly written and understandable. The final research instrument contained 86 items. For acquiring respondents' subjective estimates, a five-point Likert scale was used.

The questionnaire took about 30 min to fill in. It consisted of: 10 general demographic questions, 20 questions from the Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ), 15 questions from the Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ), 10 questions from the Job Involvement Questionnaire (JIQ), 18 questions of the Brayfield-Rothe Job Satisfaction Scale (JSS), 6 questions of the Job Diagnostic Survey (JDS) and 7 additional original questions related to the rules and procedures within the organization.

The Minnesota Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ), 20 items short form ( Weiss et al., 1967 ), was used to gather data about job satisfaction of participants. The MSQ – short version items, are rated on 5-points Likert scale (1 very dissatisfied with this aspect of my job, and 5 – very satisfied with this aspect of my job) with two subscales measuring intrinsic and extrinsic job satisfaction.

Organizational commitment was measured using The Organizational Commitment Questionnaire (OCQ). It is a 15-item scale developed by Mowday, Steers and Porter ( Mowday et al., 1979 ) and uses a 5-point Likert type response format, with 3 factors that can describe this commitment: willingness to exert effort, desire to maintain membership in the organization, and acceptance of organizational values.

The most commonly used measure of job involvement has been the Job Involvement Questionnaire (JIQ, Kanungo, 1982 ), 10-items scale designed to assess how participants feel toward their present job. The response scale on a 5-point scale varied between “strongly disagree/not applicable to me” to “strongly agree/fully applicable”.

The Brayfield and Rothe's 18-item Job Satisfaction Index (JSI, Brayfield and Rothe, 1951 ) was used to measure overall job satisfaction, operationalized on five-point Likert scale.

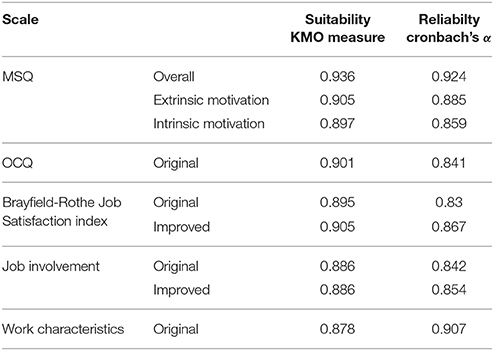

Psychometric analysis conducted showed that all the questionnaires were adequately reliable (Cronbach alpha > 0.7). The suitability of the data for factor analysis has been confirmed using the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) Test (see Table 2 ).

Table 2 . Basic psychometric characteristics of the instruments.

For further analysis we used summary scores for the different scales. Job satisfaction was represented with the overall score of MSQ, as the data analysis revealed a strong connection between the extrinsic and intrinsic motivators. The overall score on the OCQ was used as a measure of organizational commitment, while the score on JDS was used to reflect job characteristics. The JSS and JIQ scales have been modified, by eliminating a few questions, in order to improve reliability and suitability for factor analysis.

Statistical analysis was carried out using the SPSS software. The SPSS Amos structural equation modeling software was used to create the Structural Equation Models (SEMs).

The data was first checked for outliers using box-plot analysis. The only outliers identified were related to the years of employment, but these seem to be consistent to what is expected in practice in Serbia, so no observations needed to be removed from the dataset.

3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

Although research dimensions were empirically validated and confirmed in several prior studies, to the best of our knowledge, the empirical confirmation of the research instrument (i.e., questionnaire) and its constituents in the case of Serbia and South-Eastern Europe is quite scarce. Furthermore, the conditions in which previous studies were conducted could vary between research populations. Also, such differences could affect the structure of the research concepts. Thus, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted in order to empirically validate the structure of research dimensions and to test the research instrument, within the context of the research population of South-Eastern Europe and Serbia.

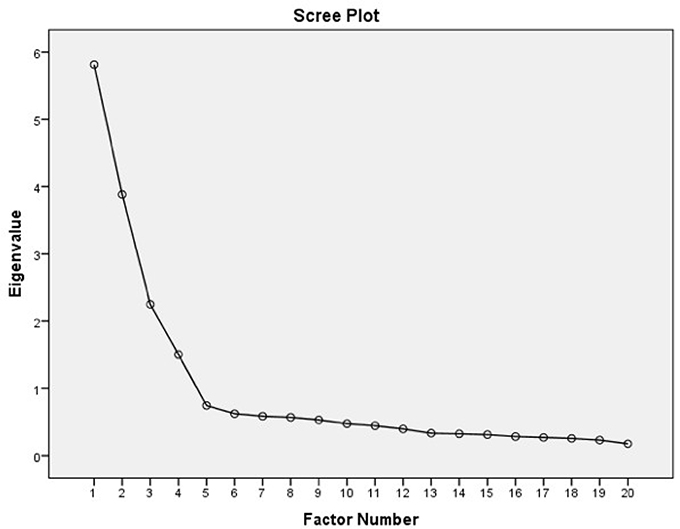

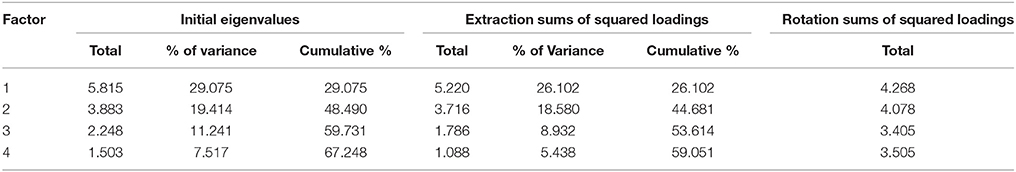

Using the maximum likelihood method we identified four factors, which account for 67% of the variance present in the data. The scree plot of the results of the analysis is shown in Figure 3 . As the figure shows, we retained the factors above the inflection point.

Figure 3 . Scree plot of the EFA results.

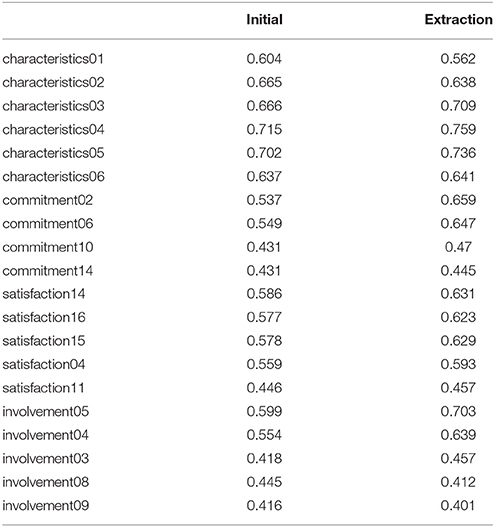

The communalities for the variables loading into the factors are shown in Table 3 and the questions corresponding to our variables are listed in Table 4 . Initial communalities are estimates of the proportion of variance in each variable accounted for by all components (factors) identified, while the extraction communalities refer to the part of the variance explained by the four factors extracted. The model explains more of the variance then the initial factors, for all but the last variable.

Table 3 . Communalities.

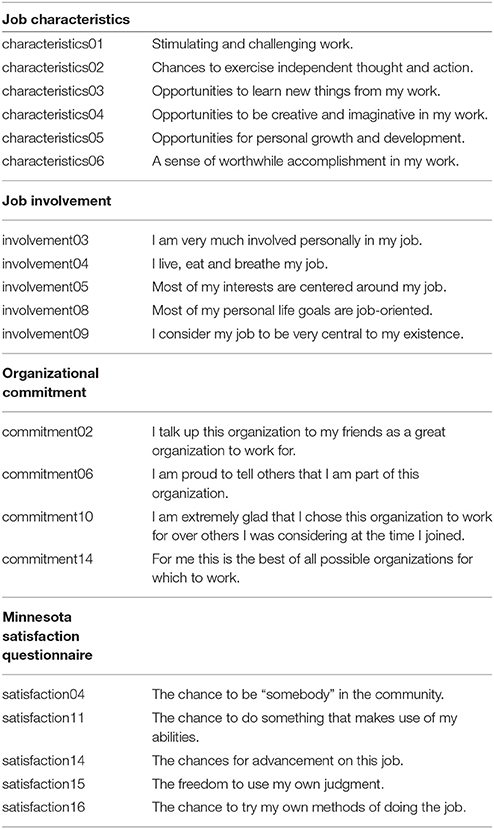

Table 4 . Questions that build our constructs.

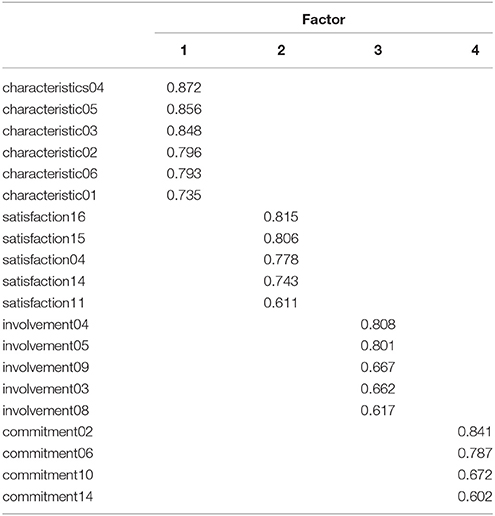

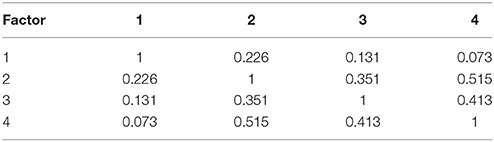

More detailed results of the EFA for the four factors, are shown in Table 5 . The unique loadings of specific items measured with the different questions in the questionnaire on the factors identified are shown in the pattern matrix (Table 6 ). As the table shows, each factor is loaded into by items that were designed to measure a specific construct and there are no cross-loadings. The first factor corresponds to job characteristics, second to job satisfaction, third to job involvement and the final to organizational commitment. The correlation between the factors is relatively low and shown in Table 7 .

Table 5 . Total variance explained by the dominant factors.

Table 6 . Pattern matrix for the factors identified.

Table 7 . Factor correlation matrix.

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

In the next part of our analysis we used Structural Equation Modeling to validate and improve a part of the model proposed by Locke and Latham (2004) that focuses on work characteristics, job satisfaction, organizational commitment and job involvement.

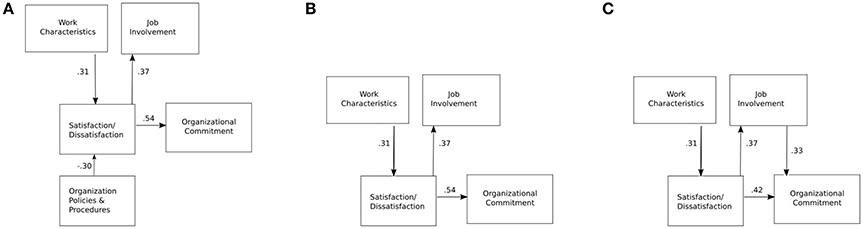

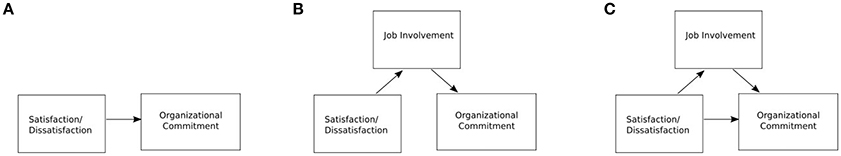

Although the EFA suggest the existence of four, not five, dominant factors in the model, diverging from the model proposed by Locke and Latham (2004) , in our initial experiments we used their original model, shown in Figure 4A , taking into account also organizational policies and procedures.

Figure 4 . The evolution of our model (the path coefficients are standardized): (A) the initial model based on Locke and Latham (2004) , (B) no partial mediation, and (C) partial mediation introduced.

In this (default) model, the only independent variable are the job characteristics. The standardized regression coefficients shown in Figure 4A (we show standardized coefficients throughout Figure 4 ) indicate that the relationship between the satisfaction and organizational commitment seems to be stronger (standard coefficient value of 0.54) than the one between satisfaction and involvement (standard coefficient value of 0.37). The effect of job characteristics and policies and procedures on the employee satisfaction seems to be balanced (standard coefficient values of 0.31 and 0.30, respectively).

The default model does not fit our data well. The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) for this model is 0.759, the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) is 0.598, while the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) is 0.192.