The Big Five in SLA pp 1–25 Cite as

Personality: Definitions, Approaches and Theories

- Ewa Piechurska-Kuciel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6690-231X 3

- First Online: 04 November 2020

2191 Accesses

2 Citations

Part of the book series: Second Language Learning and Teaching ((SLLT))

The main objective of this chapter is to describe the concept of personality and approaches to researching it. For this reason, first a view on outlining the field of personality psychology in its present form, then the key term—personality—is discussed. The next section contains a synopsis of the main approaches to the study of personality, including psychoanalytic, learning and humanistic perspectives. The objective of the second part is to present the main theoretical directions in personality studies, which are divided into two basic trends. The first one is represented by type theories that focus on qualitative differences and discrete categories. The other direction is composed of trait theories that aim to formulate the latent structure of personality on the basis of statistical procedures, this has led to the development of the trait model adopted as the groundwork of this volume—the Big Five. The last section of this chapter is devoted to a general description of the most important theories exploring the development of personality across a lifespan (psychosexual, psychosocial, cognitive, and social cognitive).

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institute of Linguistics, Opole University, Opole, Opolskie, Poland

Ewa Piechurska-Kuciel

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Piechurska-Kuciel, E. (2020). Personality: Definitions, Approaches and Theories. In: The Big Five in SLA. Second Language Learning and Teaching. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-59324-7_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-59324-7_1

Published : 04 November 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-59323-0

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-59324-7

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, personality research in the 21st century: new developments and directions for the field.

Journal of Management History

ISSN : 1751-1348

Article publication date: 19 August 2022

Issue publication date: 6 April 2023

The purpose of this study is to systematically examine and classify the multitude of personality traits that have emerged in the literature beyond the Big Five (Five Factor Model) since the turn of the 21st century. The authors argue that this represents a new phase of personality research that is characterized both by construct proliferation and a movement away from the Big Five and demonstrates how personality as a construct has substantially evolved in the 21st century.

Design/methodology/approach

The authors conducted a comprehensive, systematic review of personality research from 2000 to 2020 across 17 management and psychology journals. This search yielded 1,901 articles, of which 440 were relevant and subsequently coded for this review.

The review presented in this study uncovers 155 traits, beyond the Big Five, that have been explored, which the authors organize and analyze into 10 distinct categories. Each category comprises a definition, lists the included traits and highlights an exemplar construct. The authors also specify the significant research outcomes associated with each trait category.

Originality/value

This review categorizes the 155 personality traits that have emerged in the management and psychology literature that describe personality beyond the Big Five. Based on these findings, this study proposes new avenues for future research and offers insights into the future of the field as the concept of personality has shifted in the 21st century.

- Personality

- Systematic literature review

Medina-Craven, M.N. , Ostermeier, K. , Sigdyal, P. and McLarty, B.D. (2023), "Personality research in the 21st century: new developments and directions for the field", Journal of Management History , Vol. 29 No. 2, pp. 276-304. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMH-06-2022-0021

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2022, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 22 May 2020

Assessing the Big Five personality traits using real-life static facial images

- Alexander Kachur ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1165-2672 1 ,

- Evgeny Osin ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3330-5647 2 ,

- Denis Davydov ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3747-7403 3 ,

- Konstantin Shutilov 4 &

- Alexey Novokshonov 4

Scientific Reports volume 10 , Article number: 8487 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

122k Accesses

41 Citations

347 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Computer science

- Human behaviour

There is ample evidence that morphological and social cues in a human face provide signals of human personality and behaviour. Previous studies have discovered associations between the features of artificial composite facial images and attributions of personality traits by human experts. We present new findings demonstrating the statistically significant prediction of a wider set of personality features (all the Big Five personality traits) for both men and women using real-life static facial images. Volunteer participants (N = 12,447) provided their face photographs (31,367 images) and completed a self-report measure of the Big Five traits. We trained a cascade of artificial neural networks (ANNs) on a large labelled dataset to predict self-reported Big Five scores. The highest correlations between observed and predicted personality scores were found for conscientiousness (0.360 for men and 0.335 for women) and the mean effect size was 0.243, exceeding the results obtained in prior studies using ‘selfies’. The findings strongly support the possibility of predicting multidimensional personality profiles from static facial images using ANNs trained on large labelled datasets. Future research could investigate the relative contribution of morphological features of the face and other characteristics of facial images to predicting personality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Facial recognition technology can expose political orientation from naturalistic facial images

Michal Kosinski

Individual differences and the multidimensional nature of face perception

David White & A. Mike Burton

Professional actors demonstrate variability, not stereotypical expressions, when portraying emotional states in photographs

Tuan Le Mau, Katie Hoemann, … Lisa Feldman Barrett

Introduction

A growing number of studies have linked facial images to personality. It has been established that humans are able to perceive certain personality traits from each other’s faces with some degree of accuracy 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 . In addition to emotional expressions and other nonverbal behaviours conveying information about one’s psychological processes through the face, research has found that valid inferences about personality characteristics can even be made based on static images of the face with a neutral expression 5 , 6 , 7 . These findings suggest that people may use signals from each other’s faces to adjust the ways they communicate, depending on the emotional reactions and perceived personality of the interlocutor. Such signals must be fairly informative and sufficiently repetitive for recipients to take advantage of the information being conveyed 8 .

Studies focusing on the objective characteristics of human faces have found some associations between facial morphology and personality features. For instance, facial symmetry predicts extraversion 9 . Another widely studied indicator is the facial width to height ratio (fWHR), which has been linked to various traits, such as achievement striving 10 , deception 11 , dominance 12 , aggressiveness 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , and risk-taking 17 . The fWHR can be detected with high reliability irrespective of facial hair. The accuracy of fWHR-based judgements suggests that the human perceptual system may have evolved to be sensitive to static facial features, such as the relative face width 18 .

There are several theoretical reasons to expect associations between facial images and personality. First, genetic background contributes to both face and personality. Genetic correlates of craniofacial characteristics have been discovered both in clinical contexts 19 , 20 and in non-clinical populations 21 . In addition to shaping the face, genes also play a role in the development of various personality traits, such as risky behaviour 22 , 23 , 24 , and the contribution of genes to some traits exceeds the contribution of environmental factors 25 . For the Big Five traits, heritability coefficients reflecting the proportion of variance that can be attributed to genetic factors typically lie in the 0.30–0.60 range 26 , 27 . From an evolutionary perspective, these associations can be expected to have emerged by means of sexual selection. Recent studies have argued that some static facial features, such as the supraorbital region, may have evolved as a means of social communication 28 and that facial attractiveness signalling valuable personality characteristics is associated with mating success 29 .

Second, there is some evidence showing that pre- and postnatal hormones affect both facial shape and personality. For instance, the face is a visible indicator of the levels of sex hormones, such as testosterone and oestrogen, which affect the formation of skull bones and the fWHR 30 , 31 , 32 . Given that prenatal and postnatal sex hormone levels do influence behaviour, facial features may correlate with hormonally driven personality characteristics, such as aggressiveness 33 , competitiveness, and dominance, at least for men 34 , 35 . Thus, in addition to genes, the associations of facial features with behavioural tendencies may also be explained by androgens and potentially other hormones affecting both face and behaviour.

Third, the perception of one’s facial features by oneself and by others influences one’s subsequent behaviour and personality 36 . Just as the perceived ‘cleverness’ of an individual may lead to higher educational attainment 37 , prejudice associated with the shape of one’s face may lead to the development of maladaptive personality characteristics (i.e., the ‘Quasimodo complex’ 38 ). The associations between appearance and personality over the lifespan have been explored in longitudinal observational studies, providing evidence of ‘self-fulfilling prophecy’-type and ‘self-defeating prophecy’-type effects 39 .

Fourth and finally, some personality traits are associated with habitual patterns of emotionally expressive behaviour. Habitual emotional expressions may shape the static features of the face, leading to the formation of wrinkles and/or the development of facial muscles.

Existing studies have revealed the links between objective facial picture cues and general personality traits based on the Five-Factor Model or the Big Five (BF) model of personality 40 . However, a quick glance at the sizes of the effects found in these studies (summarized in Table 1 ) reveals much controversy. The results appear to be inconsistent across studies and hardly replicable 41 . These inconsistencies may result from the use of small samples of stimulus faces, as well as from the vast differences in methodologies. Stronger effect sizes are typically found in studies using composite facial images derived from groups of individuals with high and low scores on each of the Big Five dimensions 6 , 7 , 8 . Naturally, the task of identifying traits using artificial images comprised of contrasting pairs with all other individual features eliminated or held constant appears to be relatively easy. This is in contrast to realistic situations, where faces of individuals reflect a full range of continuous personality characteristics embedded in a variety of individual facial features.

Studies relying on photographic images of individual faces, either artificially manipulated 2 , 42 or realistic, tend to yield more modest effects. It appears that studies using realistic photographs made in controlled conditions (neutral expression, looking straight at the camera, consistent posture, lighting, and distance to the camera, no glasses, no jewellery, no make-up, etc.) produce stronger effects than studies using ‘selfies’ 25 . Unfortunately, differences in the methodologies make it hard to hypothesize whether the diversity of these findings is explained by variance in image quality, image background, or the prediction models used.

Research into the links between facial picture cues and personality traits faces several challenges. First, the number of specific facial features is very large, and some of them are hard to quantify. Second, the effects of isolated facial features are generally weak and only become statistically noticeable in large samples. Third, the associations between objective facial features and personality traits might be interactive and nonlinear. Finally, studies using real-life photographs confront an additional challenge in that the very characteristics of the images (e.g., the angle of the head, facial expression, makeup, hairstyle, facial hair style, etc.) are based on the subjects’ choices, which are potentially influenced by personality; after all, one of the principal reasons why people make and share their photographs is to signal to others what kind of person they are. The task of isolating the contribution of each variable out of the multitude of these individual variables appears to be hardly feasible. Instead, recent studies in the field have tended to rely on a holistic approach, investigating the subjective perception of personality based on integral facial images.

The holistic approach aims to mimic the mechanisms of human perception of the face and the ways in which people make judgements about each other’s personality. This approach is supported by studies of human face perception, showing that faces are perceived and encoded in a holistic manner by the human brain 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 . Put differently, when people identify others, they consider individual facial features (such as a person’s eyes, nose, and mouth) in concert as a single entity rather than as independent pieces of information 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 . Similar to facial identification, personality judgements involve the extraction of invariant facial markers associated with relatively stable characteristics of an individual’s behaviour. Existing evidence suggests that various social judgements might be based on a common visual representational system involving the holistic processing of visual information 51 , 52 . Thus, even though the associations between isolated facial features and personality characteristics sought by ancient physiognomists have emerged to be weak, contradictory or even non-existent, the holistic approach to understanding the face-personality links appears to be more promising.

An additional challenge faced by studies seeking to reveal the face-personality links is constituted by the inconsistency of the evaluations of personality traits by human raters. As a result, a fairly large number of human raters is required to obtain reliable estimates of personality traits for each photograph. In contrast, recent attempts at using machine learning algorithms have suggested that artificial intelligence may outperform individual human raters. For instance, S. Hu and colleagues 40 used the composite partial least squares component approach to analyse dense 3D facial images obtained in controlled conditions and found significant associations with personality traits (stronger for men than for women).

A similar approach can be implemented using advanced machine learning algorithms, such as artificial neural networks (ANNs), which can extract and process significant features in a holistic manner. The recent applications of ANNs to the analysis of human faces, body postures, and behaviours with the purpose of inferring apparent personality traits 53 , 54 indicate that this approach leads to a higher accuracy of prediction compared to individual human raters. The main difficulty of the ANN approach is the need for large labelled training datasets that are difficult to obtain in laboratory settings. However, ANNs do not require high-quality photographs taken in controlled conditions and can potentially be trained using real-life photographs provided that the dataset is large enough. The interpretation of findings in such studies needs to acknowledge that a real-life photograph, especially one chosen by a study participant, can be viewed as a holistic behavioural act, which may potentially contain other cues to the subjects’ personality in addition to static facial features (e.g., lighting, hairstyle, head angle, picture quality, etc.).

The purpose of the current study was to investigate the associations of facial picture cues with self-reported Big Five personality traits by training a cascade of ANNs to predict personality traits from static facial images. The general hypothesis is that a real-life photograph contains cues about personality that can be extracted using machine learning. Due to the vast diversity of findings concerning the prediction accuracy of different traits across previous studies, we did not set a priori hypotheses about differences in prediction accuracy across traits.

Prediction accuracy

We used data from the test dataset containing predicted scores for 3,137 images associated with 1,245 individuals. To determine whether the variance in the predicted scores was associated with differences across images or across individuals, we calculated the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) presented in Table 2 . The between-individual proportion of variance in the predicted scores ranged from 79 to 88% for different traits, indicating a general consistency of predicted scores for different photographs of the same individual. We derived the individual scores used in all subsequent analyses as the simple averages of the predicted scores for all images provided by each participant.

The correlation coefficients between the self-report test scores and the scores predicted by the ANN ranged from 0.14 to 0.36. The associations were strongest for conscientiousness and weakest for openness. Extraversion and neuroticism were significantly better predicted for women than for men (based on the z test). We also compared the prediction accuracy within each gender using Steiger’s test for dependent sample correlation coefficients. For men, conscientiousness was predicted more accurately than the other four traits (the differences among the latter were not statistically significant). For women, conscientiousness was predicted more accurately, and openness was predicted less accurately compared to the three other traits.

The mean absolute error (MAE) of prediction ranged between 0.89 and 1.04 standard deviations. We did not find any associations between the number of photographs and prediction error.

Trait intercorrelations

The structure of the correlations between the scales was generally similar for the observed test scores and the predicted values, but some coefficients differed significantly (based on the z test) (see Table 3 ). Most notably, predicted openness was more strongly associated with conscientiousness (negatively) and extraversion (positively), whereas its association with agreeableness was negative rather than positive. The associations of predicted agreeableness with conscientiousness and neuroticism were stronger than those between the respective observed scores. In women, predicted neuroticism demonstrated a stronger inverse association with conscientiousness and a stronger positive association with openness. In men, predicted neuroticism was less strongly associated with extraversion than its observed counterpart.

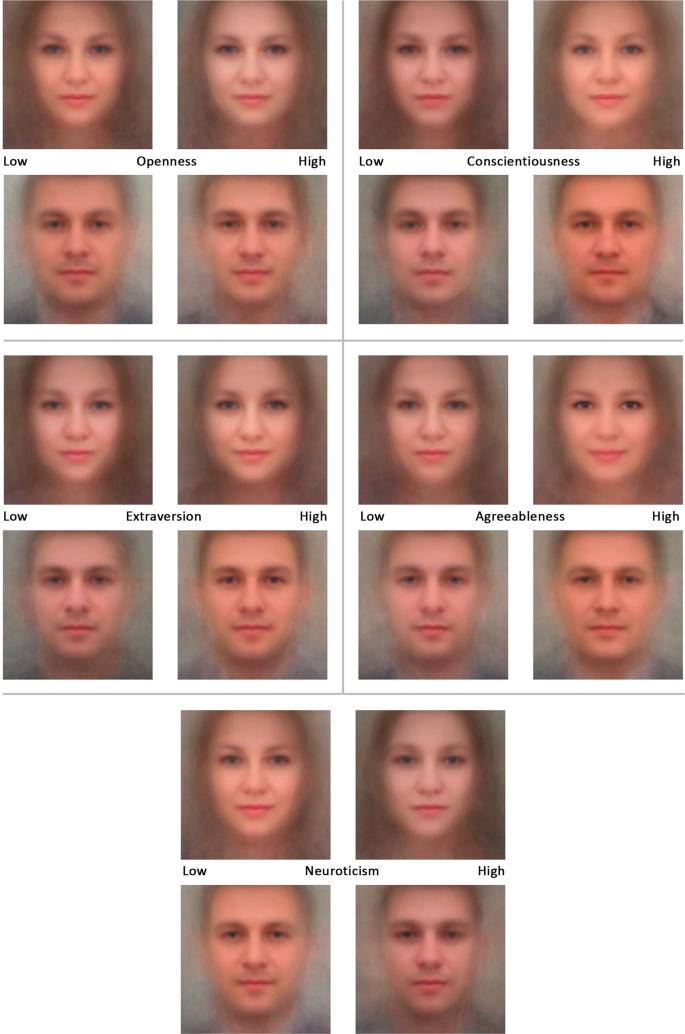

To illustrate the findings, we created composite images using Abrosoft FantaMorph 5 by averaging the uploaded images across contrast groups of 100 individuals with the highest and the lowest test scores on each trait. The resulting morphed images in which individual features are eliminated are presented in Fig. 1 .

Composite facial images morphed across contrast groups of 100 individuals for each Big Five trait.

This study presents new evidence confirming that human personality is related to individual facial appearance. We expected that machine learning (in our case, artificial neural networks) could reveal multidimensional personality profiles based on static morphological facial features. We circumvented the reliability limitations of human raters by developing a neural network and training it on a large dataset labelled with self-reported Big Five traits.

We expected that personality traits would be reflected in the whole facial image rather than in its isolated features. Based on this expectation, we developed a novel two-tier machine learning algorithm to encode the invariant facial features as a vector in a 128-dimensional space that was used to predict the BF traits by means of a multilayer perceptron. Although studies using real-life photographs do not require strict experimental conditions, we had to undertake a series of additional organizational and technological steps to ensure consistent facial image characteristics and quality.

Our results demonstrate that real-life photographs taken in uncontrolled conditions can be used to predict personality traits using complex computer vision algorithms. This finding is in contrast to previous studies that mostly relied on high-quality facial images taken in controlled settings. The accuracy of prediction that we obtained exceeds that in the findings of prior studies that used realistic individual photographs taken in uncontrolled conditions (e.g., selfies 55 ). The advantage of our methodology is that it is relatively simple (e.g., it does not rely on 3D scanners or 3D facial landmark maps) and can be easily implemented using a desktop computer with a stock graphics accelerator.

In the present study, conscientiousness emerged to be more easily recognizable than the other four traits, which is consistent with some of the existing findings 7 , 40 . The weaker effects for extraversion and neuroticism found in our sample may be because these traits are associated with positive and negative emotional experiences, whereas we only aimed to use images with neutral or close to neutral emotional expressions. Finally, this appears to be the first study to achieve a significant prediction of openness to experience. Predictions of personality based on female faces appeared to be more reliable than those for male faces in our sample, in contrast to some previous studies 40 .

The BF factors are known to be non-orthogonal, and we paid attention to their intercorrelations in our study 56 , 57 . Various models have attempted to explain the BF using higher-order dimensions, such as stability and plasticity 58 or a single general factor of personality (GFP) 59 . We discovered that the intercorrelations of predicted factors tend to be stronger than the intercorrelations of self-report questionnaire scales used to train the model. This finding suggests a potential biological basis of GFP. However, the stronger intercorrelations of the predicted scores can be explained by consistent differences in picture quality (just as the correlations between the self-report scales can be explained by social desirability effects and other varieties of response bias 60 ). Clearly, additional research is needed to understand the context of this finding.

We believe that the present study, which did not involve any subjective human raters, constitutes solid evidence that all the Big Five traits are associated with facial cues that can be extracted using machine learning algorithms. However, despite having taken reasonable organizational and technical steps to exclude the potential confounds and focus on static facial features, we are still unable to claim that morphological features of the face explain all the personality-related image variance captured by the ANNs. Rather, we propose to see facial photographs taken by subjects themselves as complex behavioural acts that can be evaluated holistically and that may contain various other subtle personality cues in addition to static facial features.

The correlations reported above with a mean r = 0.243 can be viewed as modest; indeed, facial image-based personality assessment can hardly replace traditional personality measures. However, this effect size indicates that an ANN can make a correct guess about the relative standing of two randomly chosen individuals on a personality dimension in 58% of cases (as opposed to the 50% expected by chance) 61 . The effect sizes we observed are comparable with the meta-analytic estimates of correlations between self-reported and observer ratings of personality traits: the associations range from 0.30 to 0.49 when one’s personality is rated by close relatives or colleagues, but only from −0.01 to 0.29 when rated by strangers 62 . Thus, an artificial neural network relying on static facial images outperforms an average human rater who meets the target in person without any prior acquaintance. Given that partner personality and match between two personalities predict friendship formation 63 , long-term relationship satisfaction 64 , and the outcomes of dyadic interaction in unstructured settings 65 , the aid of artificial intelligence in making partner choices could help individuals to achieve more satisfying interaction outcomes.

There are a vast number of potential applications to be explored. The recognition of personality from real-life photos can be applied in a wide range of scenarios, complementing the traditional approaches to personality assessment in settings where speed is more important than accuracy. Applications may include suggesting best-fitting products or services to customers, proposing to individuals a best match in dyadic interaction settings (such as business negotiations, online teaching, etc.) or personalizing the human-computer interaction. Given that the practical value of any selection method is proportional to the number of decisions made and the size and variability of the pool of potential choices 66 , we believe that the applied potential of this technology can be easily revealed at a large scale, given its speed and low cost. Because the reliability and validity of self-report personality measures is not perfect, prediction could be further improved by supplementing these measures with peer ratings and objective behavioural indicators of personality traits.

The fact that conscientiousness was predicted better than the other traits for both men and women emerges as an interesting finding. From an evolutionary perspective, one would expect the traits most relevant for cooperation (conscientiousness and agreeableness) and social interaction (certain facets of extraversion and neuroticism, such as sociability, dominance, or hostility) to be reflected more readily in the human face. The results are generally in line with this idea, but they need to be replicated and extended by incorporating trait facets in future studies to provide support for this hypothesis.

Finally, although we tried to control the potential sources of confounds and errors by instructing the participants and by screening the photographs (based on angles, facial expressions, makeup, etc.), the present study is not without limitations. First, the real-life photographs we used could still carry a variety of subtle cues, such as makeup, angle, light facial expressions, and information related to all the other choices people make when they take and share their own photographs. These additional cues could say something about their personality, and the effects of all these variables are inseparable from those of static facial features, making it hard to draw any fundamental conclusions from the findings. However, studies using real-life photographs may have higher ecological validity compared to laboratory studies; our results are more likely to generalize to real-life situations where users of various services are asked to share self-pictures of their choice.

Another limitation pertains to a geographically bounded sample of individuals; our participants were mostly Caucasian and represented one cultural and age group (Russian-speaking adults). Future studies could replicate the effects using populations representing a more diverse variety of ethnic, cultural, and age groups. Studies relying on other sources of personality data (e.g., peer ratings or expert ratings), as well as wider sets of personality traits, could complement and extend the present findings.

Sample and procedure

The study was carried out in the Russian language. The participants were anonymous volunteers recruited through social network advertisements. They did not receive any financial remuneration but were provided with a free report on their Big Five personality traits. The data were collected online using a dedicated research website and a mobile application. The participants provided their informed consent, completed the questionnaires, reported their age and gender and were asked to upload their photographs. They were instructed to take or upload several photographs of their face looking directly at the camera with enough lighting, a neutral facial expression and no other people in the picture and without makeup.

Our goal was to obtain an out-of-sample validation dataset of 616 respondents of each gender to achieve 80% power for a minimum effect we considered to be of practical significance ( r = 0.10 at p < 0.05), requiring a total of 6,160 participants of each gender in the combined dataset comprising the training and validation datasets. However, we aimed to gather more data because we expected that some online respondents might provide low-quality or non-genuine photographs and/or invalid questionnaire responses.

The initial sample included 25,202 participants who completed the questionnaire and uploaded a total of 77,346 photographs. The final combined dataset comprised 12,447 valid questionnaires and 31,367 associated photographs after the data screening procedures (below). The participants ranged in age from 18 to 60 (59.4% women, M = 27.61, SD = 12.73, and 40.6% men, M = 32.60, SD = 11.85). The dataset was split randomly into a training dataset (90%) and a test dataset (10%) used to validate the prediction model. The validation dataset included the responses of 505 men who provided 1224 facial images and 740 women who provided 1913 images. Due to the sexually dimorphic nature of facial features and certain personality traits (particularly extraversion 1 , 67 , 68 ), all the predictive models were trained and validated separately for male and female faces.

Ethical approval

The research was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Open University for the Humanities and Economics. We obtained the participants’ informed consent to use their data and photographs for research purposes and to publish generalized findings. The morphed group average images presented in the paper do not allow the identification of individuals. No information or images that could lead to the identification of study participants have been published.

Data screening

We excluded incomplete questionnaires (N = 3,035) and used indices of response consistency to screen out random responders 69 . To detect systematic careless responses, we used the modal response category count, maximum longstring (maximum number of identical responses given in sequence by participant), and inter-item standard deviation for each questionnaire. At this stage, we screened out the answers of individuals with zero standard deviations (N = 329) and a maximum longstring above 10 (N = 1,416). To detect random responses, we calculated the following person-fit indices: the person-total response profile correlation, the consistency of response profiles for the first and the second half of the questionnaire, the consistency of response profiles obtained based on equivalent groups of items, the number of polytomous Guttman errors, and the intraclass correlation of item responses within facets.

Next, we conducted a simulation by generating random sets of integers in the 1–5 range based on a normal distribution (µ = 3, σ = 1) and on the uniform distribution and calculating the same person-fit indices. For each distribution, we generated a training dataset and a test dataset, each comprised of 1,000 simulated responses and 1,000 real responses drawn randomly from the sample. Next, we ran a logistic regression model using simulated vs real responses as the outcome variable and chose an optimal cutoff point to minimize the misclassification error (using the R package optcutoff). The sensitivity value was 0.991 for the uniform distribution and 0.960 for the normal distribution, and the specificity values were 0.923 and 0.980, respectively. Finally, we applied the trained model to the full dataset and identified observations predicted as likely to be simulated based on either distribution (N = 1,618). The remaining sample of responses (N = 18,804) was used in the subsequent analyses.

Big Five measure

We used a modified Russian version of the 5PFQ questionnaire 70 , which is a 75-item measure of the Big Five model, with 15 items per trait grouped into five three-item facets. To confirm the structural validity of the questionnaire, we tested an exploratory structural equation (ESEM) model with target rotation in Mplus 8.2. The items were treated as ordered categorical variables using the WLSMV estimator, and facet variance was modelled by introducing correlated uniqueness values for the items comprising each facet.

The theoretical model showed a good fit to the data (χ 2 = 147854.68, df = 2335, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.931; RMSEA = 0.040 [90% CI: 0.040, 0.041]; SRMR = 0.024). All the items showed statistically significant loadings on their theoretically expected scales (λ ranged from 0.14 to 0.87, M = 0.51, SD = 0.17), and the absolute cross-loadings were reasonably low (M = 0.11, SD = 0.11). The distributions of the resulting scales were approximately normal (with skewness and kurtosis values within the [−1; 1] range). To assess the reliability of the scales, we calculated two internal consistency indices, namely, robust omega (using the R package coefficientalpha) and algebraic greatest lower bound (GLB) reliability (using the R package psych) 71 (see Table 4 ).

Image screening and pre-processing

The images (photographs and video frames) were subjected to a three-step screening procedure aimed at removing fake and low-quality images. First, images with no human faces or with more than one human face were detected by our computer vision (CV) algorithms and automatically removed. Second, celebrity images were identified and removed by means of a dedicated neural network trained on a celebrity photo dataset (CelebFaces Attributes Dataset (CelebA), N > 200,000) 72 that was additionally enriched with pictures of Russian celebrities. The model showed a 98.4% detection accuracy. Third, we performed a manual moderation of the remaining images to remove images with partially covered faces, those that were evidently photoshopped or any other fake images not detected by CV.

The images retained for subsequent processing were converted to single-channel 8-bit greyscale format using the OpenCV framework (opencv.org). Head position (pitch, yaw, roll) was measured using our own dedicated neural network (multilayer perceptron) trained on a sample of 8 000 images labelled by our team. The mean absolute error achieved on the test sample of 800 images was 2.78° for roll, 1.67° for pitch, and 2.34° for yaw. We used the head position data to retain the images with yaw and roll within the −30° to 30° range and pitch within the −15° to 15° range.

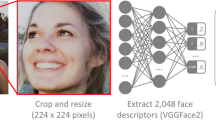

Next, we assessed emotional neutrality using the Microsoft Cognitive Services API on the Azure platform (score range: 0 to 1) and used 0.50 as a threshold criterion to remove emotionally expressive images. Finally, we applied the face and eye detection, alignment, resize, and crop functions available within the Dlib (dlib.net) open-source toolkit to arrive at a set of standardized 224 × 224 pixel images with eye pupils aligned to a standard position with an accuracy of 1 px. Images with low resolution that contained less than 60 pixels between the eyes, were excluded in the process.

The final photoset comprised 41,835 images. After the screened questionnaire responses and images were joined, we obtained a set of 12,447 valid Big Five questionnaires associated with 31,367 validated images (an average of 2.59 images per person for women and 2.42 for men).

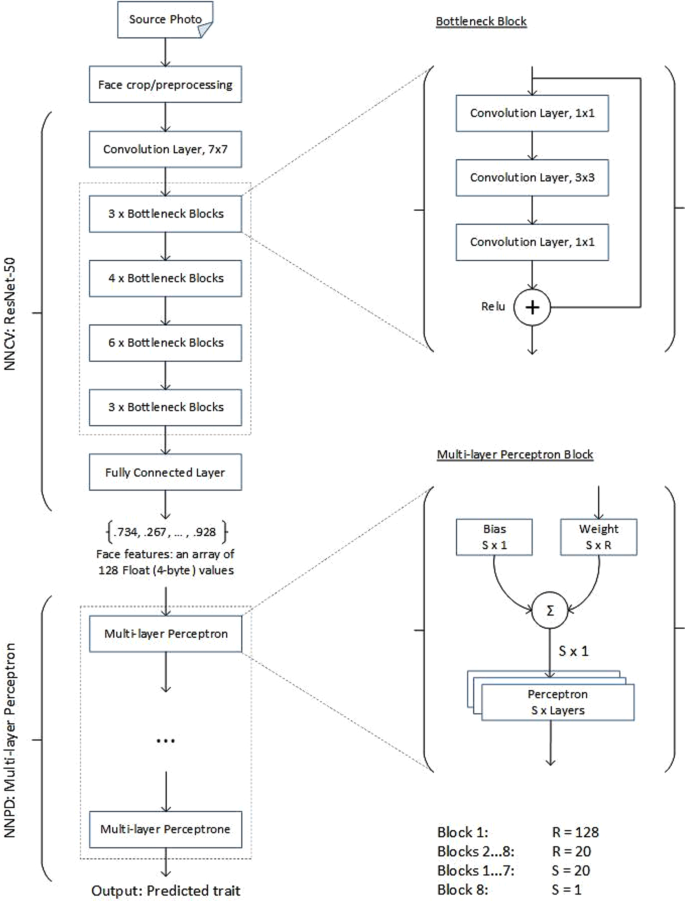

Neural network architecture

First, we developed a computer vision neural network (NNCV) aiming to determine the invariant features of static facial images that distinguish one face from another but remain constant across different images of the same person. We aimed to choose a neural network architecture with a good feature space and resource-efficient learning, considering the limited hardware available to our research team. We chose a residual network architecture based on ResNet 73 (see Fig. 2 ).

Layer architecture of the computer vision neural network (NNCV) and the personality diagnostics neural network (NNPD).

This type of neural network was originally developed for image classification. We dropped the final layer from the original architecture and obtained a NNCV that takes a static monochrome image (224 × 224 pixels in size) and generates a vector of 128 32-bit dimensions describing unique facial features in the source image. As a measure of success, we calculated the Euclidean distance between the vectors generated from different images.

Using Internet search engines, we collected a training dataset of approximately 2 million openly available unlabelled real-life photos taken in uncontrolled conditions stratified by race, age and gender (using search engine queries such as ‘face photo’, ‘face pictures’, etc.). The training was conducted on a server equipped with four NVidia Titan accelerators. The trained neural network was validated on a dataset of 40,000 images belonging to 800 people, which was an out-of-sample part of the original dataset. The Euclidean distance threshold for the vectors belonging to the same person was 0.40 after the training was complete.

Finally, we trained a personality diagnostics neural network (NNPD), which was implemented as a multilayer perceptron (see Fig. 2 ). For that purpose, we used a training dataset (90% of the final sample) containing the questionnaire scores of 11,202 respondents and a total of 28,230 associated photographs. The NNPD takes the vector of the invariants obtained from NNCV as an input and predicts the Big Five personality traits as the output. The network was trained using the same hardware, and the training process took 9 days. The whole process was performed for male and female faces separately.

Data availability

The set of photographs is not made available because we did not solicit the consent of the study participants to publish the individual photographs. The test dataset with the observed and predicted Big Five scores is available from the openICPSR repository: https://doi.org/10.3886/E109082V1 .

Kramer, R. S. S., King, J. E. & Ward, R. Identifying personality from the static, nonexpressive face in humans and chimpanzees: Evidence of a shared system for signaling personality. Evol. Hum. Behav . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2010.10.005 (2011).

Walker, M. & Vetter, T. Changing the personality of a face: Perceived big two and big five personality factors modeled in real photographs. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 110 , 609–624 (2016).

Article Google Scholar

Naumann, L. P., Vazire, S., Rentfrow, P. J. & Gosling, S. D. Personality Judgments Based on Physical Appearance. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 35 , 1661–1671 (2009).

Borkenau, P., Brecke, S., Möttig, C. & Paelecke, M. Extraversion is accurately perceived after a 50-ms exposure to a face. J. Res. Pers. 43 , 703–706 (2009).

Shevlin, M., Walker, S., Davies, M. N. O., Banyard, P. & Lewis, C. A. Can you judge a book by its cover? Evidence of self-stranger agreement on personality at zero acquaintance. Pers. Individ. Dif . https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00356-2 (2003).

Penton-Voak, I. S., Pound, N., Little, A. C. & Perrett, D. I. Personality Judgments from Natural and Composite Facial Images: More Evidence For A “Kernel Of Truth” In Social Perception. Soc. Cogn. 24 , 607–640 (2006).

Little, A. C. & Perrett, D. I. Using composite images to assess accuracy in personality attribution to faces. Br. J. Psychol. 98 , 111–126 (2007).

Kramer, R. S. S. & Ward, R. Internal Facial Features are Signals of Personality and Health. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 63 , 2273–2287 (2010).

Pound, N., Penton-Voak, I. S. & Brown, W. M. Facial symmetry is positively associated with self-reported extraversion. Pers. Individ. Dif. 43 , 1572–1582 (2007).

Lewis, G. J., Lefevre, C. E. & Bates, T. Facial width-to-height ratio predicts achievement drive in US presidents. Pers. Individ. Dif. 52 , 855–857 (2012).

Haselhuhn, M. P. & Wong, E. M. Bad to the bone: facial structure predicts unethical behaviour. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 279 , 571 LP–576 (2012).

Valentine, K. A., Li, N. P., Penke, L. & Perrett, D. I. Judging a Man by the Width of His Face: The Role of Facial Ratios and Dominance in Mate Choice at Speed-Dating Events. Psychol. Sci . 25 , (2014).

Carre, J. M. & McCormick, C. M. In your face: facial metrics predict aggressive behaviour in the laboratory and in varsity and professional hockey players. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 275 , 2651–2656 (2008).

Carré, J. M., McCormick, C. M. & Mondloch, C. J. Facial structure is a reliable cue of aggressive behavior: Research report. Psychol. Sci . https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02423.x (2009).

Haselhuhn, M. P., Ormiston, M. E. & Wong, E. M. Men’s Facial Width-to-Height Ratio Predicts Aggression: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS One 10 , e0122637 (2015).

Lefevre, C. E., Etchells, P. J., Howell, E. C., Clark, A. P. & Penton-Voak, I. S. Facial width-to-height ratio predicts self-reported dominance and aggression in males and females, but a measure of masculinity does not. Biol. Lett . 10 , (2014).

Welker, K. M., Goetz, S. M. M. & Carré, J. M. Perceived and experimentally manipulated status moderates the relationship between facial structure and risk-taking. Evol. Hum. Behav . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2015.03.006 (2015).

Geniole, S. N. & McCormick, C. M. Facing our ancestors: judgements of aggression are consistent and related to the facial width-to-height ratio in men irrespective of beards. Evol. Hum. Behav. 36 , 279–285 (2015).

Valentine, M. et al . Computer-Aided Recognition of Facial Attributes for Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Pediatrics 140 , (2017).

Ferry, Q. et al . Diagnostically relevant facial gestalt information from ordinary photos. Elife 1–22 https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.02020.001 (2014).

Claes, P. et al . Modeling 3D Facial Shape from DNA. PLoS Genet. 10 , e1004224 (2014).

Carpenter, J. P., Garcia, J. R. & Lum, J. K. Dopamine receptor genes predict risk preferences, time preferences, and related economic choices. J. Risk Uncertain. 42 , 233–261 (2011).

Dreber, A. et al . The 7R polymorphism in the dopamine receptor D4 gene (<em>DRD4</em>) is associated with financial risk taking in men. Evol. Hum. Behav. 30 , 85–92 (2009).

Bouchard, T. J. et al . Sources of human psychological differences: the Minnesota Study of Twins Reared Apart. Science (80-.). 250 , 223 LP–228 (1990).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Livesley, W. J., Jang, K. L. & Vernon, P. A. Phenotypic and genetic structure of traits delineating personality disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.55.10.941 (1998).

Bouchard, T. J. & Loehlin, J. C. Genes, evolution, and personality. Behavior Genetics https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012294324713 (2001).

Vukasović, T. & Bratko, D. Heritability of personality: A meta-analysis of behavior genetic studies. Psychol. Bull. 141 , 769–785 (2015).

Godinho, R. M., Spikins, P. & O’Higgins, P. Supraorbital morphology and social dynamics in human evolution. Nat. Ecol. Evol . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0528-0 (2018).

Rhodes, G., Simmons, L. W. & Peters, M. Attractiveness and sexual behavior: Does attractiveness enhance mating success? Evol. Hum. Behav . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2004.08.014 (2005).

Lefevre, C. E., Lewis, G. J., Perrett, D. I. & Penke, L. Telling facial metrics: Facial width is associated with testosterone levels in men. Evol. Hum. Behav. 34 , 273–279 (2013).

Whitehouse, A. J. O. et al . Prenatal testosterone exposure is related to sexually dimorphic facial morphology in adulthood. Proceedings. Biol. Sci. 282 , 20151351 (2015).

Penton-Voak, I. S. & Chen, J. Y. High salivary testosterone is linked to masculine male facial appearance in humans. Evol. Hum. Behav . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2004.04.003 (2004).

Carré, J. M. & Archer, J. Testosterone and human behavior: the role of individual and contextual variables. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 19 , 149–153 (2018).

Swaddle, J. P. & Reierson, G. W. Testosterone increases perceived dominance but not attractiveness in human males. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci . https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2002.2165 (2002).

Eisenegger, C., Kumsta, R., Naef, M., Gromoll, J. & Heinrichs, M. Testosterone and androgen receptor gene polymorphism are associated with confidence and competitiveness in men. Horm. Behav. 92 , 93–102 (2017).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Kaplan, H. B. Social Psychology of Self-Referent Behavior . https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-2233-5 . (Springer US, 1986).

Rosenthal, R. & Jacobson, L. Pygmalion in the classroom. Urban Rev . https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02322211 (1968).

Masters, F. W. & Greaves, D. C. The Quasimodo complex. Br. J. Plast. Surg . 204–210 (1967).

Zebrowitz, L. A., Collins, M. A. & Dutta, R. The Relationship between Appearance and Personality Across the Life Span. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 24 , 736–749 (1998).

Hu, S. et al . Signatures of personality on dense 3D facial images. Sci. Rep. 7 , 73 (2017).

Kosinski, M. Facial Width-to-Height Ratio Does Not Predict Self-Reported Behavioral Tendencies. Psychol. Sci. 28 , 1675–1682 (2017).

Walker, M., Schönborn, S., Greifeneder, R. & Vetter, T. The basel face database: A validated set of photographs reflecting systematic differences in big two and big five personality dimensions. PLoS One 13 , (2018).

Goffaux, V. & Rossion, B. Faces are ‘spatial’ - Holistic face perception is supported by low spatial frequencies. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform . https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-1523.32.4.1023 (2006).

Schiltz, C. & Rossion, B. Faces are represented holistically in the human occipito-temporal cortex. Neuroimage https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.05.037 (2006).

Van Belle, G., De Graef, P., Verfaillie, K., Busigny, T. & Rossion, B. Whole not hole: Expert face recognition requires holistic perception. Neuropsychologia https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.04.034 (2010).

Quadflieg, S., Todorov, A., Laguesse, R. & Rossion, B. Normal face-based judgements of social characteristics despite severely impaired holistic face processing. Vis. cogn. 20 , 865–882 (2012).

McKone, E. Isolating the Special Component of Face Recognition: Peripheral Identification and a Mooney Face. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn . https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.30.1.181 (2004).

Sergent, J. An investigation into component and configural processes underlying face perception. Br. J. Psychol . https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1984.tb01895.x (1984).

Tanaka, J. W. & Farah, M. J. Parts and Wholes in Face Recognition. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. Sect. A https://doi.org/10.1080/14640749308401045 (1993).

Young, A. W., Hellawell, D. & Hay, D. C. Configurational information in face perception. Perception https://doi.org/10.1068/p160747n (2013).

Calder, A. J. & Young, A. W. Understanding the recognition of facial identity and facial expression. Nature Reviews Neuroscience https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1724 (2005).

Todorov, A., Loehr, V. & Oosterhof, N. N. The obligatory nature of holistic processing of faces in social judgments. Perception https://doi.org/10.1068/p6501 (2010).

Junior, J. C. S. J. et al . First Impressions: A Survey on Computer Vision-Based Apparent Personality Trait Analysis. (2018).

Wang, Y. & Kosinski, M. Deep neural networks are more accurate than humans at detecting sexual orientation from facial images. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 114 , 246–257 (2018).

Qiu, L., Lu, J., Yang, S., Qu, W. & Zhu, T. What does your selfie say about you? Comput. Human Behav. 52 , 443–449 (2015).

Digman, J. M. Higher order factors of the Big Five. J.Pers.Soc.Psychol . https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.6.1246 (1997).

Musek, J. A general factor of personality: Evidence for the Big One in the five-factor model. J. Res. Pers . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.02.003 (2007).

DeYoung, C. G. Higher-order factors of the Big Five in a multi-informant sample. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 91 , 1138–1151 (2006).

Rushton, J. P. & Irwing, P. A General Factor of Personality (GFP) from two meta-analyses of the Big Five: Digman (1997) and Mount, Barrick, Scullen, and Rounds (2005). Pers. Individ. Dif. 45 , 679–683 (2008).

Wood, D., Gardner, M. H. & Harms, P. D. How functionalist and process approaches to behavior can explain trait covariation. Psychol. Rev. 122 , 84–111 (2015).

Dunlap, W. P. Generalizing the Common Language Effect Size indicator to bivariate normal correlations. Psych. Bull. 116 , 509–511 (1994).

Connolly, J. J., Kavanagh, E. J. & Viswesvaran, C. The convergent validity between self and observer ratings of personality: A meta-analytic review. Int. J. of Selection and Assessment. 15 , 110–117 (2007).

Harris, K. & Vazire, S. On friendship development and the Big Five personality traits. Soc. and Pers. Psychol. Compass. 10 , 647–667 (2016).

Weidmann, R., Schönbrodt, F. D., Ledermann, T. & Grob, A. Concurrent and longitudinal dyadic polynomial regression analyses of Big Five traits and relationship satisfaction: Does similarity matter? J. Res. in Personality. 70 , 6–15 (2017).

Cuperman, R. & Ickes, W. Big Five predictors of behavior and perceptions in initial dyadic interactions: Personality similarity helps extraverts and introverts, but hurts “disagreeables”. J. of Pers. and Soc. Psychol. 97 , 667–684 (2009).

Schmidt, F. L. & Hunter, J. E. The validity and utility of selection methods in personnel psychology: Practical and theoretical implications of 85 years of research findings. Psychol. Bull. 124 , 262–274 (1998).

Brown, M. & Sacco, D. F. Unrestricted sociosexuality predicts preferences for extraverted male faces. Pers. Individ. Dif. 108 , 123–127 (2017).

Lukaszewski, A. W. & Roney, J. R. The origins of extraversion: joint effects of facultative calibration and genetic polymorphism. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 37 , 409–21 (2011).

Curran, P. G. Methods for the detection of carelessly invalid responses in survey data. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 66 , 4–19 (2016).

Khromov, A. B. The five-factor questionnaire of personality [Pjatifaktornyj oprosnik lichnosti]. In Rus. (Kurgan State University, 2000).

Trizano-Hermosilla, I. & Alvarado, J. M. Best alternatives to Cronbach’s alpha reliability in realistic conditions: Congeneric and asymmetrical measurements. Front. Psychol . https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00769 (2016).

Liu, Z., Luo, P., Wang, X. & Tang, X. Deep Learning Face Attributes in the Wild. in 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV) 3730–3738 https://doi.org/10.1109/ICCV.2015.425 (IEEE, 2015).

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S. & Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. in 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 770–778 https://doi.org/10.1109/CVPR.2016.90 (IEEE, 2016).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the assistance of Oleg Poznyakov, who organized the data collection, and we are grateful to the anonymous peer reviewers for their detailed and insightful feedback.

Contributions

A.K., E.O., D.D. and A.N. designed the study. K.S. and A.K. designed the ML algorithms and trained the ANN. A.N. contributed to the data collection. A.K., K.S. and D.D. contributed to data pre-processing. E.O., D.D. and A.K. analysed the data, contributed to the main body of the manuscript, and revised the text. A.K. prepared Figs. 1 and 2. All the authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Alexander Kachur or Evgeny Osin .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

A.K., K.S. and A.N. were employed by the company that provided the datasets for the research. E.O. and D.D. declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Kachur, A., Osin, E., Davydov, D. et al. Assessing the Big Five personality traits using real-life static facial images. Sci Rep 10 , 8487 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65358-6

Download citation

Received : 12 April 2019

Accepted : 28 April 2020

Published : 22 May 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65358-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Unravelling the many facets of human cooperation in an experimental study.

- Victoria V. Rostovtseva

- Mikael Puurtinen

- Franz J. Weissing

Scientific Reports (2023)

Using deep learning to predict ideology from facial photographs: expressions, beauty, and extra-facial information

- Stig Hebbelstrup Rye Rasmussen

- Steven G. Ludeke

- Robert Klemmensen

Facial Expression of TIPI Personality and CHMP-Tri Psychopathy Traits in Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes)

- Lindsay Murray

- Jade Goddard

- David Gordon

Human Nature (2023)

Seeing the darkness: identifying the Dark Triad from emotionally neutral faces

- Danielle Haroun

- Yaarit Amram

- Joseph Glicksohn

Current Psychology (2023)

Py-Feat: Python Facial Expression Analysis Toolbox

- Jin Hyun Cheong

- Eshin Jolly

- Luke J. Chang

Affective Science (2023)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Personality types revisited–a literature-informed and data-driven approach to an integration of prototypical and dimensional constructs of personality description

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Psychology, Freie Universität Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Psychology, University of Duisburg-Essen, Duisburg Germany

Affiliation Personality Psychology and Psychological Assessment Unit, Helmut Schmidt University of the Federal Armed Forces Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

- André Kerber,

- Marcus Roth,

- Philipp Yorck Herzberg

- Published: January 7, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244849

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

A new algorithmic approach to personality prototyping based on Big Five traits was applied to a large representative and longitudinal German dataset (N = 22,820) including behavior, personality and health correlates. We applied three different clustering techniques, latent profile analysis, the k-means method and spectral clustering algorithms. The resulting cluster centers, i.e. the personality prototypes, were evaluated using a large number of internal and external validity criteria including health, locus of control, self-esteem, impulsivity, risk-taking and wellbeing. The best-fitting prototypical personality profiles were labeled according to their Euclidean distances to averaged personality type profiles identified in a review of previous studies on personality types. This procedure yielded a five-cluster solution: resilient, overcontroller, undercontroller, reserved and vulnerable-resilient. Reliability and construct validity could be confirmed. We discuss wether personality types could comprise a bridge between personality and clinical psychology as well as between developmental psychology and resilience research.

Citation: Kerber A, Roth M, Herzberg PY (2021) Personality types revisited–a literature-informed and data-driven approach to an integration of prototypical and dimensional constructs of personality description. PLoS ONE 16(1): e0244849. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244849

Editor: Stephan Doering, Medical University of Vienna, AUSTRIA

Received: January 5, 2020; Accepted: December 17, 2020; Published: January 7, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Kerber et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data used in this article were made available by the German Socio-Economic Panel (SOEP, Data for years 1984-2015) at the German Institute for Economic Research, Berlin, Germany. To ensure the confidentiality of respondents’ information, the SOEP adheres to strict security standards in the provision of SOEP data. The data are reserved exclusively for research use, that is, they are provided only to the scientific community. To require full access to the data used in this study, it is required to sign a data distribution contract. All contact informations and the procedure to request the data can be obtained at: https://www.diw.de/en/diw_02.c.222829.en/access_and_ordering.html .

Funding: The author(s) received no specific funding for this work.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Although documented theories about personality types reach back more than 2000 years (i.e. Hippocrates’ humoral pathology), and stereotypes for describing human personality are also widely used in everyday psychology, the descriptive and variable-oriented assessment of personality, i.e. the description of personality on five or six trait domains, has nowadays consolidated its position in modern personality psychology.

In recent years, however, the person-oriented approach, i.e. the description of an individual personality by its similarity to frequently occurring prototypical expressions, has amended the variable-oriented approach with the addition of valuable insights into the description of personality and the prediction of behavior. Focusing on the trait configurations, the person-oriented approach aims to identify personality types that share the same typical personality profile [ 1 ].

Nevertheless, the direct comparison of the utility of person-oriented vs. variable-oriented approaches to personality description yielded mixed results. For example Costa, Herbst, McCrae, Samuels and Ozer [ 2 ] found a higher amount of explained variance in predicting global functioning, geriatric depression or personality disorders for the variable-centered approach using Big Five personality dimensions. But these results also reflect a methodological caveat of this approach, as the categorical simplification of dimensionally assessed variables logically explains less variance. Despite this, the person-centered approach was found to heighten the predictability of a person’s behavior [ 3 , 4 ] or the development of adolescents in terms of internalizing and externalizing symptoms or academic success [ 5 , 6 ], problem behavior, delinquency and depression [ 7 ] or anxiety symptoms [ 8 ], as well as stress responses [ 9 ] and social attitudes [ 10 ]. It has also led to new insights into the function of personality in the context of other constructs such as adjustment [ 2 ], coping behavior [ 11 ], behavioral activation and inhibition [ 12 ], subjective and objective health [ 13 ] or political orientation [ 14 ], and has greater predictive power in explaining longitudinally measured individual differences in more temperamental outcomes such as aggressiveness [ 15 ].

However, there is an ongoing debate about the appropriate number and characteristics of personality prototypes and whether they perhaps constitute an methodological artifact [ 16 ].

With the present paper, we would like to make a substantial contribution to this debate. In the following, we first provide a short review of the personality type literature to identify personality types that were frequently replicated and calculate averaged prototypical profiles based on these previous findings. We then apply multiple clustering algorithms on a large German dataset and use those prototypical profiles generated in the first step to match the results of our cluster analysis to previously found personality types by their Euclidean distance in the 5-dimensional space defined by the Big Five traits. This procedure allows us to reliably link the personality prototypes found in our study to previous empirical evidence, an important analysis step lacking in most previous studies on this topic.

The empirical ground of personality types

The early studies applying modern psychological statistics to investigate personality types worked with the Q-sort procedure [ 1 , 15 , 17 ], and differed in the number of Q-factors. With the Q-Sort method, statements about a target person must be brought in an order depending on how characteristic they are for this person. Based on this Q-Sort data, prototypes can be generated using Q-Factor Analysis, also called inverse factor analysis. As inverse factor analysis is basically interchanging variables and persons in the data matrix, the resulting factors of a Q-factor analysis are prototypical personality profiles and not hypothetical or latent variable dimensions. On this basis, personality types (groups of people with similar personalities) can be formed in a second step by assigning each person to the prototype with whose profile his or her profile correlates most closely. All of these early studies determined at least three prototypes, which were labeled resilient, overcontroler and undercontroler grounded in Block`s theory of ego-control and ego-resiliency [ 18 ]. According to Jack and Jeanne Block’s decade long research, individuals high in ego-control (i.e. the overcontroler type) tend to appear constrained and inhibited in their actions and emotional expressivity. They may have difficulty making decisions and thus be non-impulsive or unnecessarily deny themselves pleasure or gratification. Children classified with this type in the studies by Block tend towards internalizing behavior. Individuals low in ego-control (i.e. the undercontroler type), on the other hand, are characterized by higher expressivity, a limited ability to delay gratification, being relatively unattached to social standards or customs, and having a higher propensity to risky behavior. Children classified with this type in the studies by Block tend towards externalizing behavior.

Individuals high in Ego-resiliency (i.e. the resilient type) are postulated to be able to resourcefully adapt to changing situations and circumstances, to tend to show a diverse repertoire of behavioral reactions and to be able to have a good and objective representation of the “goodness of fit” of their behavior to the situations/people they encounter. This good adjustment may result in high levels of self-confidence and a higher possibility to experience positive affect.

Another widely used approach to find prototypes within a dataset is cluster analysis. In the field of personality type research, one of the first studies based on this method was conducted by Caspi and Silva [ 19 ], who applied the SPSS Quick Cluster algorithm to behavioral ratings of 3-year-olds, yielding five prototypes: undercontrolled, inhibited, confident, reserved, and well-adjusted.

While the inhibited type was quite similar to Block`s overcontrolled type [ 18 ] and the well-adjusted type was very similar to the resilient type, two further prototypes were added: confident and reserved. The confident type was described as easy and responsive in social interaction, eager to do exercises and as having no or few problems to be separated from the parents. The reserved type showed shyness and discomfort in test situations but without decreased reaction speed compared to the inhibited type. In a follow-up measurement as part of the Dunedin Study in 2003 [ 20 ], the children who were classified into one of the five types at age 3 were administered the MPQ at age 26, including the assessment of their individual Big Five profile. Well-adjusteds and confidents had almost the same profiles (below-average neuroticism and above average on all other scales except for extraversion, which was higher for the confident type); undercontrollers had low levels of openness, conscientiousness and openness to experience; reserveds and inhibiteds had below-average extraversion and openness to experience, whereas inhibiteds additionally had high levels of conscientiousness and above-average neuroticism.

Following these studies, a series of studies based on cluster analysis, using the Ward’s followed by K-means algorithm, according to Blashfield & Aldenderfer [ 21 ], on Big Five data were published. The majority of the studies examining samples with N < 1000 [ 5 , 7 , 22 – 26 ] found that three-cluster solutions, namely resilients, overcontrollers and undercontrollers, fitted the data the best. Based on internal and external fit indices, Barbaranelli [ 27 ] found that a three-cluster and a four-cluster solution were equally suitable, while Gramzow [ 28 ] found a four-cluster solution with the addition of the reserved type already published by Caspi et al. [ 19 , 20 ]. Roth and Collani [ 10 ] found that a five-cluster solution fitted the data the best. Using the method of latent profile analysis, Merz and Roesch [ 29 ] found a 3-cluster, Favini et al. [ 6 ] found a 4-cluster solution and Kinnunen et al. [ 13 ] found a 5-cluster solution to be most appropriate.

Studies examining larger samples of N > 1000 reveal a different picture. Several favor a five-cluster solution [ 30 – 34 ] while others favor three clusters [ 8 , 35 ]. Specht et al. [ 36 ] examined large German and Australian samples and found a three-cluster solution to be suitable for the German sample and a four-cluster solution to be suitable for the Australian sample. Four cluster solutions were also found to be most suitable to Australian [ 37 ] and Chinese [ 38 ] samples. In a recent publication, the authors cluster-analysed very large datasets on Big Five personality comprising more than 1,5 million online participants using Gaussian mixture models [ 39 ]. Albeit their results “provide compelling evidence, both quantitatively and qualitatively, for at least four distinct personality types”, two of the four personality types in their study had trait profiles not found previously and all four types were given labels unrelated to previous findings and theory. Another recent publication [ 40 ] cluster-analysing data of over 270,000 participants on HEXACO personality “provided evidence that a five-profile solution was optimal”. Despite limitations concerning the comparability of HEXACO trait profiles with FFM personality type profiles, the authors again decided to label their personality types unrelated to previous findings instead using agency-communion and attachment theories.

We did not include studies in this literature review, which had fewer than 199 participants or those which restricted the number of types a priori and did not use any method to compare different clustering solutions. We have made these decisions because a too low sample size increases the probability of the clustering results being artefacts. Further, a priori limitation of the clustering results to a certain number of personality types is not well reasonable on the base of previous empirical evidence and again may produce artefacts, if the a priori assumed number of clusters does not fit the data well.

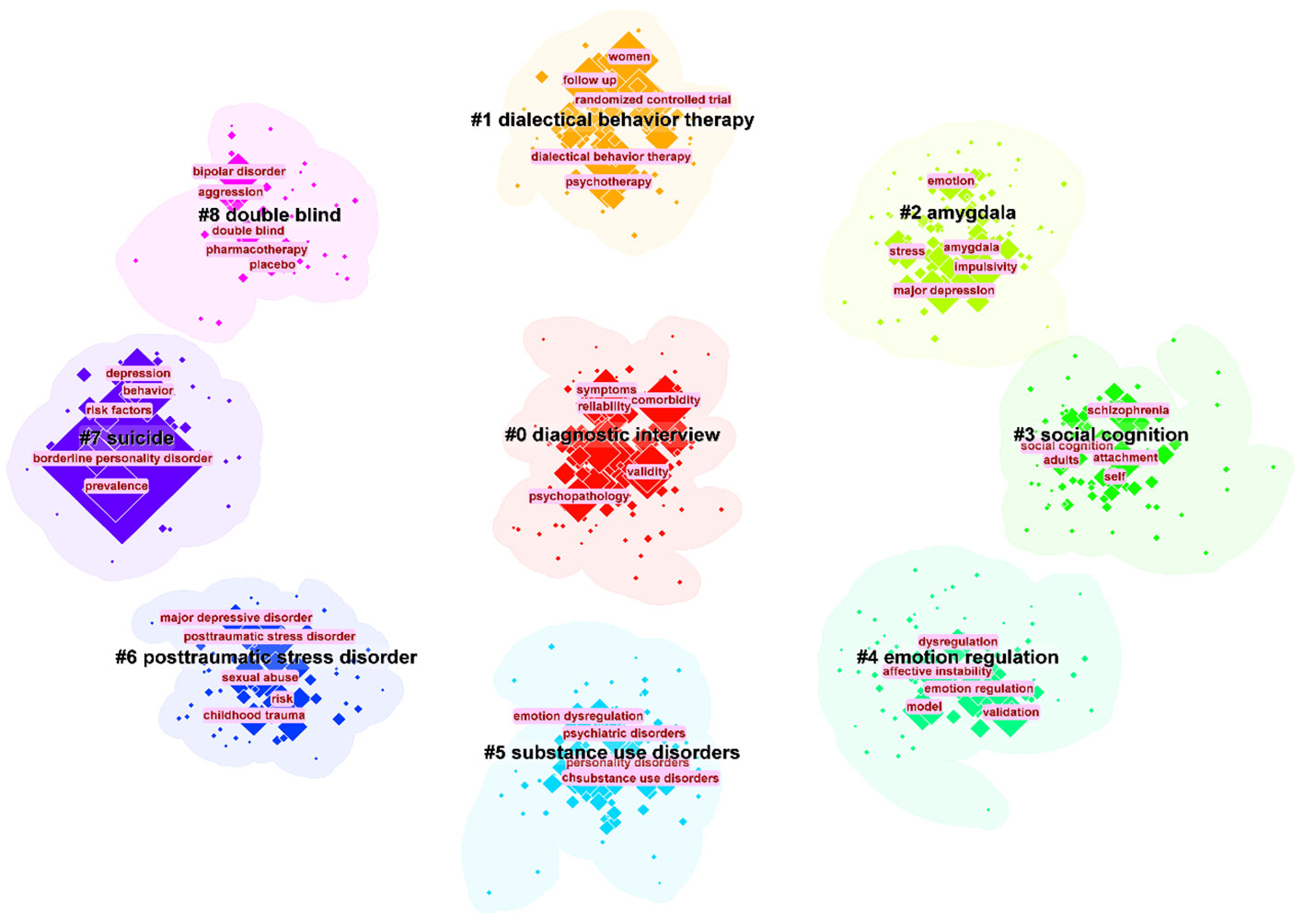

To gain a better overview, we extracted all available z-scores from all samples of the above-described studies. Fig 1 shows the averaged z-scores extracted from the results of FFM clustering solutions for all personality prototypes that occurred in more than one study. The error bars represent the standard deviation of the distribution of the z-scores of the respective trait within the same personality type throughout the different studies. Taken together the resilient type was replicated in all 19 of the mentioned studies, the overcontroler type in 16, the undercontroler personality type in 17 studies, the reserved personality type was replicated in 6 different studies, the confident personality type in 4 and the non-desirable type was replicated twice.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

Average Big Five z-scores of personality types based on clustering of FFM datasets with N ≥ 199 that were replicated at least once. Error bars indicate the standard deviation of the repective trait within the respective personality type found in the literature [ 5 , 6 , 10 , 22 – 25 , 27 – 31 , 33 – 36 , 38 , 39 , 41 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244849.g001

Three implications can be drawn from this figure. First, although the results of 19 studies on 26 samples with a total N of 1,560,418 were aggregated, the Big Five profiles for all types can still be clearly distinguished. In other words, personality types seem to be a phenomenon that survives the aggregation of data from different sources. Second, there are more than three replicable personality types, as there are other replicated personality types that seem to have a distinct Big Five profile, at least regarding the reserved and confident personality types. Third and lastly, the non-desirable type seems to constitute the opposite of the resilient type. Looking at two-cluster solutions on Big Five data personality types in the above-mentioned literature yields the resilient opposed to the non-desirable type. This and the fact that it was only replicated twice in the above mentioned studies points to the notion that it seems not to be a distinct type but rather a combined cluster of the over- and undercontroller personality types. Further, both studies with this type in the results did not find either the undercontroller or the overcontroller cluster or both. Taken together, five distinct personality types were consistently replicated in the literature, namely resilient, overcontroller, undercontroller, reserved and confident. However, inferring from the partly large error margin for some traits within some prototypes, not all personality traits seem to contribute evenly to the occurrence of the different prototypes. While for the overcontroler type, above average neuroticism, below average extraversion and openness seem to be distinctive, only below average conscientiousness and agreeableness seemed to be most characteristic for the undercontroler type. The reserved prototype was mostly characterized by below average openness and neuroticism with above average conscientiousness. Above average extraversion, openness and agreeableness seemed to be most distinctive for the confident type. Only for the resilient type, distinct expressions of all Big Five traits seemed to be equally significant, more precisely below average neuroticism and above average extraversion, openness, agreeableness and conscientiousness.

Research gap and novelty of this study

The cluster methods used in most of the mentioned papers were the Ward’s followed by K-means method or latent profile analysis. With the exception of Herzberg and Roth [ 30 ], Herzberg [ 33 ], Barbaranelli [ 27 ] and Steca et. al. [ 25 ], none of the studies used internal or external validity indices other than those which their respective algorithm (in most cases the SPSS software package) had already included. Gerlach et al. [ 39 ] used Gaussian mixture models in combination with density measures and likelihood measures.

The bias towards a smaller amount of clusters resulting from the utilization of just one replication index, e.g. Cohen's Kappa calculated by split-half cross-validation, which was ascertained by Breckenridge [ 42 ] and Overall & Magee [ 43 ], is probably the reason why a three-cluster solution is preferred in most studies. Herzberg and Roth [ 30 ] pointed to the study by Milligan and Cooper [ 44 ], which proved the superiority of the Rand index over Cohen's Kappa and also suggested a variety of validity metrics for internal consistency to examine the construct validity of the cluster solutions.

Only a part of the cited studies had a large representative sample of N > 2000 and none of the studies used more than one clustering algorithm. Moreover, with the exception of Herzberg and Roth [ 30 ] and Herzberg [ 33 ], none of the studies used a large variety of metrics for assessing internal and external consistency other than those provided by the respective clustering program they used. This limitation further adds up to the above mentioned bias towards smaller amounts of clusters although the field of cluster analysis and algorithms has developed a vast amount of internal and external validity algorithms and criteria to tackle this issue. Further, most of the studies had few or no other assessments or constructs than the Big Five to assess construct validity of the resulting personality types. Herzberg and Roth [ 30 ] and Herzberg [ 33 ] as well, though using a diverse variety of validity criteria only used one clustering algorithm on a medium-sized dataset with N < 2000.