Quick Links

- UW HR Resources

Training Videos

The following videos will teach the principles of pregnancy ultrasound, infection control, fetal anatomy, how to date a pregnancy, maternal pelvic anatomy, how to examine amniotic fluid volume, placenta anatomy, fetal presentation, how to identify certain serious complications (such as bleeding, ectopic and multiple gestation pregnancy, and intrauterine growth restriction) and fetal anomalies.

Welcome and Introduction to the Course

This video provides a general introduction and overview of the training course.

How Ultrasound Works

Learning Objectives:

How to use the Ultrasound Machine

Orient the Transducer

Orient the Screen

Rapidly Survey a Pregnant Uterus

Determine Fetal Orientation from a Single Transverse Scan

Infection Control

The Purpose of IPC

How to Keep Equipment Clean and Safe

how to Wash Your Hands Properly

How to Properly Cover Your Cough

2nd & 3rd Trimester Anatomy

How to Identify Normal Fetal Anatomy of the Head, Heart, Abdomen, Spine, Extremities, Skull, Face, and Brain

Fetal Dating: 2nd & 3rd Trimesters

How to Measure the Head, Abdomen, and Femur to find Fetal Age

How to Scan the Correct Level for each Structure

How to Choose the Best Ultrasound Images to Assess Fetal Age in the 2nd and 3rd Trimesters

Pelvic Anatomy

How to Identify Normal Structures

How to Identify Common Problems during Pregnancy

1st Trimester Anatomy

How to Identify the Following Structures on Ultrasound: Gestational Sac, Yolk Sac, Fetus, Corpus Luteum

How to Describe how the Fetus Grows during the First 13 Weeks

1st Trimester Dating

How to Measure "Mean Sac Diameter" to Estimate Fetal Age

How to Measure "Crown Rump Length" to Estimate Fetal Age

How to Choose the Best Ultrasound Images to Assess Fetal Age

Amniotic Fluid

Measure the volume of amniotic fluid.

Provide appropriate care if amniotic fluid levels are too low or too high.

Identify the position of the placenta

Evaluate for placenta previa

Assess for placental abruption

Conduct appropriate follow up and referrals if you suspect either condition

Fetal Lie and Presentation

Why it is important to identify the fetal lie and presentation

How to identify an abnormal fetal lie or presentation

When to perform a follow up ultrasound

1st Trimester Pain and Bleeding

Identify the normal and abnormal gestational sac

Evaluate fetal cardiac activity

Identify the signs of complete and incomplete miscarriage

Identify the signs of molar pregnancy

Perform appropriate ultrasound followup

Ectopic Pregnancy

Identify the signs of an ectopic pregancy on ultrasound

Assess the risk level of ectopic pregnancy and respond appropriately

Multiple Gestation Pregnancy

Identify dizygotic and monozygotic twins on ultrasound

Identify complications that can result in high-risk birth

Properly refer patients with multiple gestation to the hospital

Intrauterine Growth Restriction (IUGR)

Evaluate for IUGR on clinical exam

Evaluate for IUGR with ultrasounds using three different indicators

Make appropriate referrals for IUGR

Fetal Anomalies

Identify some important abnormalities

Many fetal anomalies cannot be seen by ultrasound or are difficult to see

Some babies you scan may be born with abnormalities you did not see on ultrasound

Course Review and Video of Sonographer Scanning a Patient

This video represents a review of what you have learned and shows a sonographer scanning a pregnant woman.

Learn how to make the patient comfortable during the examination

Review how to measure fetal biometry and the amniotic fluid index

Review how to perform the ROBUST scan

Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

This topic will provide an overview of major issues related to breech presentation, including choosing the best route for delivery. Techniques for breech delivery, with a focus on the technique for vaginal breech delivery, are discussed separately. (See "Delivery of the singleton fetus in breech presentation" .)

TYPES OF BREECH PRESENTATION

● Frank breech – Both hips are flexed and both knees are extended so that the feet are adjacent to the head ( figure 1 ); accounts for 50 to 70 percent of breech fetuses at term.

● Complete breech – Both hips and both knees are flexed ( figure 2 ); accounts for 5 to 10 percent of breech fetuses at term.

- Family Planning

- Antenatal Care

- Labor & Delivery

- Newborn Care

- Child Health

- Leadership and Management in Communities

- Country Map

- Add Resource

- How to use ORB

- Resource Guidelines

- Content Review Process

- Creative Commons FAQs

- Español (es)

Fetal Lie and Presentation Ultrasound Training Video

From: University of Washington School of Medicine

Learning Objectives:

- Why it is important to identify the fetal lie and presentation

- How to identify an abnormal fetal lie or presentation

- When to perform a follow up ultrasound

Your Rating/Bookmark

Organisation, health domain, resource type.

Resource viewed 434 times

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Tests & Procedures

Diagnostic ultrasound, also called sonography or diagnostic medical sonography, is an imaging method that uses sound waves to produce images of structures within your body. The images can provide valuable information for diagnosing and directing treatment for a variety of diseases and conditions.

Most ultrasound examinations are done using an ultrasound device outside your body, though some involve placing a small device inside your body.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Assortment of Products for Daily Living from Mayo Clinic Store

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Why it's done

Ultrasound is used for many reasons, including to:

- View the uterus and ovaries during pregnancy and monitor the developing baby's health

- Diagnose gallbladder disease

- Evaluate blood flow

- Guide a needle for biopsy or tumor treatment

- Examine a breast lump

- Check the thyroid gland

- Find genital and prostate problems

- Assess joint inflammation (synovitis)

- Evaluate metabolic bone disease

More Information

- Abdominal aortic aneurysm

- Acute kidney failure

- Acute liver failure

- Acute lymphocytic leukemia

- Adenomyosis

- Adult Still disease

- Alcoholic hepatitis

- Ambiguous genitalia

- Anal cancer

- Appendicitis

- Arteriosclerosis / atherosclerosis

- Arteriovenous fistula

- Atelectasis

- Autonomic neuropathy

- Bladder stones

- Blood in urine (hematuria)

- Breast cancer

- Breast pain

- Carotid artery disease

- Cerebral palsy

- Cholestasis of pregnancy

- Chronic exertional compartment syndrome

- Chronic kidney disease

- Cleft lip and cleft palate

- Congenital adrenal hyperplasia

- Conjoined twins

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)

- Double uterus

- Down syndrome

- Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS)

- Endometrial cancer

- Endometriosis

- Enlarged breasts in men (gynecomastia)

- Enlarged liver

- Epididymitis

- Erectile dysfunction

- Eye melanoma

- Fibroadenoma

- Fibrocystic breasts

- Galactorrhea

- Ganglion cyst

- Glomerulonephritis

- Growth plate fractures

- Hamstring injury

- High blood pressure in children

- Hurthle cell cancer

- Incompetent cervix

- Infant reflux

- Inflammatory breast cancer

- Intussusception

- Invasive lobular carcinoma

- Iron deficiency anemia

- Ischemic colitis

- Kidney cancer

- Knee bursitis

- Liver cancer

- Liver disease

- Liver hemangioma

- Male breast cancer

- Mammary duct ectasia

- Median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS)

- Menstrual cramps

- Miscarriage

- Morning sickness

- Morton's neuroma

- Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C)

- Muscle strains

- Muscular dystrophy

- Myelofibrosis

- Neuroblastoma

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- Osteoporosis

- Ovarian cancer

- Ovarian cysts

- Painful intercourse (dyspareunia)

- Pancreatic cancer

- Patellar tendinitis

- Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID)

- Peripheral artery disease (PAD)

- Peyronie disease

- Placenta previa

- Placental abruption

- Polycystic kidney disease

- Polymyalgia rheumatica

- Post-vasectomy pain syndrome

- Precocious puberty

- Premature birth

- Preterm labor

- Prostate cancer

- Pulmonary embolism

- Pyloric stenosis

- Recurrent breast cancer

- Residual limb pain

- Retinal detachment

- Retinoblastoma

- Rotator cuff injury

- Sacral dimple

- Sacroiliitis

- Scrotal masses

- Secondary hypertension

- Solitary rectal ulcer syndrome

- Spermatocele

- Spina bifida

- Swollen knee

- Takayasu's arteritis

- Tapeworm infection

- Testicular cancer

- Thrombophlebitis

- Thyroid cancer

- Thyroid nodules

- Torn meniscus

- Toxic hepatitis

- Toxoplasmosis

- Tricuspid atresia

- Tuberous sclerosis

- Uterine fibroids

- Uterine prolapse

- Wilms tumor

- Zollinger-Ellison syndrome

Diagnostic ultrasound is a safe procedure that uses low-power sound waves. There are no known risks.

Ultrasound is a valuable tool, but it has limitations. Sound waves don't travel well through air or bone, so ultrasound isn't effective at imaging body parts that have gas in them or are hidden by bone, such as the lungs or head. Ultrasound may also be unable to see objects that are located very deep in the human body. To view these areas, your health care provider may order other imaging tests, such as CT or MRI scans or X-rays.

How you prepare

Most ultrasound exams require no preparation. However, there are a few exceptions:

- For some scans, such as a gallbladder ultrasound, your care provider may ask that you not eat or drink for a certain period of time before the exam.

- Others, such as a pelvic ultrasound, may require a full bladder. Your doctor will let you know how much water you need to drink before the exam. Do not urinate until the exam is done.

- Young children may need additional preparation. When scheduling an ultrasound for yourself or your child, ask your doctor if there are any specific instructions you'll need to follow.

Clothing and personal items

Wear loose clothing to your ultrasound appointment. You may be asked to remove jewelry during your ultrasound, so it's a good idea to leave any valuables at home.

What you can expect

Before the procedure.

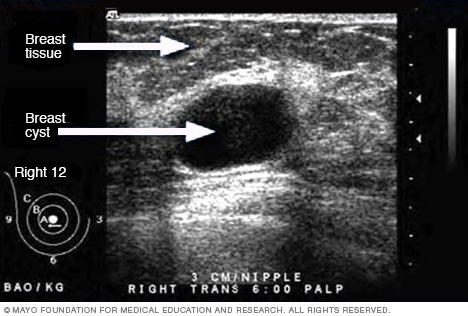

- Ultrasound of breast cyst

This ultrasound shows a breast cyst.

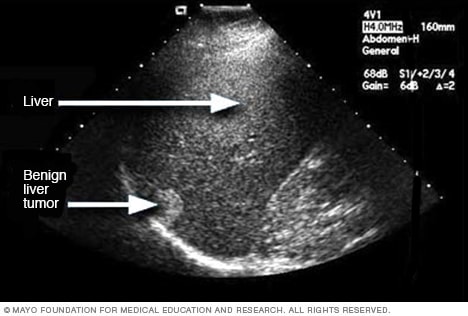

- Liver ultrasound

An ultrasound uses sound waves to make an image. This ultrasound shows a liver tumor that isn't cancer, called benign.

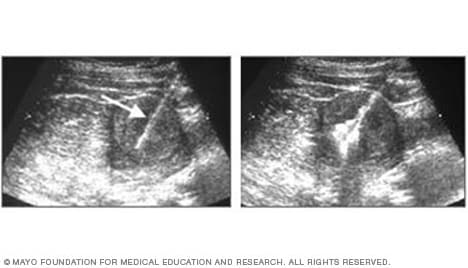

- Ultrasound of gallstones

This ultrasound shows gallstones in the gallbladder.

- Ultrasound of needle-guided procedure

These images show how ultrasound can help guide a needle into a tumor (left), where material is injected (right) to destroy tumor cells.

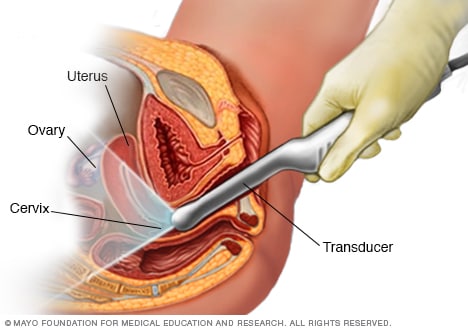

- Transvaginal ultrasound

During a transvaginal ultrasound, you lie on an exam table while a doctor or a medical technician puts a wandlike device, known as a transducer, into the vagina. Sound waves from the transducer create images of the uterus, ovaries and fallopian tubes.

Before your ultrasound begins, you may be asked to do the following:

- Remove any jewelry from the area being examined.

- Remove or reposition some or all of your clothing.

- Change into a gown.

You'll be asked to lie on an examination table.

During the procedure

Gel is applied to your skin over the area being examined. It helps prevent air pockets, which can block the sound waves that create the images. This safe, water-based gel is easy to remove from skin and, if needed, clothing.

A trained technician (sonographer) presses a small, hand-held device (transducer) against the area being studied and moves it as needed to capture the images. The transducer sends sound waves into your body, collects the ones that bounce back and sends them to a computer, which creates the images.

Sometimes, ultrasounds are done inside your body. In this case, the transducer is attached to a probe that's inserted into a natural opening in your body. Examples include:

- Transesophageal echocardiogram. A transducer, inserted into the esophagus, obtains heart images. It's usually done while under sedation.

- Transrectal ultrasound. This test creates images of the prostate by placing a special transducer into the rectum.

- Transvaginal ultrasound. A special transducer is gently inserted into the vagina to look at the uterus and ovaries.

Ultrasound is usually painless. However, you may experience mild discomfort as the sonographer guides the transducer over your body, especially if you're required to have a full bladder, or inserts it into your body.

A typical ultrasound exam takes from 30 minutes to an hour.

When your exam is complete, a doctor trained to interpret imaging studies (radiologist) analyzes the images and sends a report to your doctor. Your doctor will share the results with you.

You should be able to return to normal activities immediately after an ultrasound.

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies of tests and procedures to help prevent, detect, treat or manage conditions.

- Andreas A, et al., eds. Grainger & Allison's Diagnostic Radiology: A Textbook of Medical Imaging. 7th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Jan. 28, 2022.

- General ultrasound. RadiologyInfo.org. https://www.radiologyinfo.org/en/info/genus. Accessed Jan. 28, 2022.

- McKenzie GA (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. Feb. 1, 2022.

- Chronic pelvic pain

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Fetal macrosomia

- Heavy menstrual bleeding

- Kidney stones

- Molar pregnancy

- Peritonitis

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Soft tissue sarcoma

- Undescended testicle

- Urinary incontinence

News from Mayo Clinic

- Advancing ultrasound microvessel imaging and AI to improve cancer detection Oct. 13, 2023, 02:01 p.m. CDT

- Doctors & Departments

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

- Cord presentation

- Report problem with article

- View revision history

Citation, DOI, disclosures and article data

At the time the article was created Yuranga Weerakkody had no recorded disclosures.

At the time the article was last revised Joshua Yap had no financial relationships to ineligible companies to disclose.

- Funic presentation

- Cord (funic) presentation

A cord presentation (also known as a funic presentation or obligate cord presentation ) is a variation in the fetal presentation where the umbilical cord points towards the internal cervical os or lower uterine segment.

It may be a transient phenomenon and is usually considered insignificant until ~32 weeks. It is concerning if it persists past that date, after which it is recommended that an underlying cause be sought and precautionary management implemented.

On this page:

Epidemiology, radiographic features, treatment and prognosis, differential diagnosis.

- Cases and figures

The estimated incidence is at ~4% of pregnancies.

Associations

Recognized associations include:

marginal cord insertion from the caudal end of a low-lying placenta

uterine fibroids

uterine adhesions

congenital uterine anomalies that may prevent the fetus from engaging well into the lower uterine segment

cephalopelvic disproportion

polyhydramnios

multifetal pregnancy

long umbilical cord

Color Doppler interrogation is extremely useful and shows cord between the fetal presenting part and the internal cervical os. However, unlike a vasa previa , the placental insertion is usually normal.

ADVERTISEMENT: Supporters see fewer/no ads

As the complicating umbilical cord prolapse can lead to catastrophic consequences, most advocate an elective cesarean section delivery for persistent cord presentation in the third trimester 3 .

Complications

It can result in a higher rate of umbilical cord prolapse .

For the presence of umbilical cord vessels between the fetal presenting part and the internal cervical os on ultrasound consider:

vasa previa

- 1. Ezra Y, Strasberg SR, Farine D. Does cord presentation on ultrasound predict cord prolapse? Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 2003;56 (1): 6-9. doi:10.1159/000072323 - Pubmed citation

- 2. Kinugasa M, Sato T, Tamura M et-al. Antepartum detection of cord presentation by transvaginal ultrasonography for term breech presentation: potential prediction and prevention of cord prolapse. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2007;33 (5): 612-8. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2007.00620.x - Pubmed citation

- 3. Raga F, Osborne N, Ballester MJ et-al. Color flow Doppler: a useful instrument in the diagnosis of funic presentation. J Natl Med Assoc. 1996;88 (2): 94-6. - Free text at pubmed - Pubmed citation

- 4. Bluth EI. Ultrasound, a practical approach to clinical problems. Thieme Publishing Group. (2008) ISBN:3131168323. Read it at Google Books - Find it at Amazon

Incoming Links

- Variation in fetal presentation

- Vasa praevia

- Umbilical cord prolapse

- Vasa previa

Promoted articles (advertising)

By section:.

- Artificial Intelligence

- Classifications

- Imaging Technology

- Interventional Radiology

- Radiography

- Central Nervous System

- Gastrointestinal

- Gynaecology

- Haematology

- Head & Neck

- Hepatobiliary

- Interventional

- Musculoskeletal

- Paediatrics

- Not Applicable

Radiopaedia.org

- Feature Sponsor

- Expert advisers

Basic Principles of Ultrasound

Jul 20, 2014

720 likes | 1.59k Views

Basic Principles of Ultrasound. Objectives. Define Scope of Practice Understand Principals Understand Physics Understand Transducers Understand Terminology Understand Artifacts. Scope of Practice. eFAST in Trauma Abdomen Chest. Musculoskeletal/Soft tissue Fracture/dislocations.

Share Presentation

- vascular access

- distal shadow

- linear sequential array

Presentation Transcript

Objectives • Define Scope of Practice • Understand Principals • Understand Physics • Understand Transducers • Understand Terminology • Understand Artifacts

Scope of Practice • eFAST in Trauma • Abdomen • Chest • Musculoskeletal/Soft tissue • Fracture/dislocations • Vascular • Access • Blood flow/DVT • Ocular • FB/retinal detachment • Retrobulbar hemorrhage • Genitourinary • Bladder • Ectopic pregnancy • scrotal pain & swelling

3-Tiers • Basic • eFAST, MSK, Skin/Soft Tissue, & Vascular Access • Intermediate • Ocular, Renal, Regional Anesthesia, & DVT • Advanced • OB/Gyn, Testicular, Aorta (AAA), Cardiac (Critical Care), & Pericardiocentesis

Basic Principles • Ultrasound machine and probes create sound waves • Generate waves of vibration from the probe that travel through the tissue of the patient and return to the probe • Received by the machine and interpreted to provide images on screen • Different tissue densities affect the ultrasound beam

Principles • The intensity of the returning echo determines the brightness of the image on the screen • Strong signals = white (hyperechoic) images • Weak signals or lack of signal all together = black (hypoechoic) images • Tissue densities determine the many shades of gray in between

Physics • Diagnostic ultrasound uses sound waves in the frequency range 2-20 MHz • Key properties of sound waves: • Frequency is number of times per second the sound wave is repeated • Wavelength is the distance traveled in 1 cycle • Amplitude is distance between peak and trough

Physics – Parallel Concepts • Conceptually, ultrasound is similar to a laser range finder. • Sound waves sent from the transducer bounce off the object and return. • The ultrasound machine calculates distance to the object from the round-trip time, and creates a grey scale image on the screen.

What does it mean to me? • Lower frequencies image deep structures, but sacrifice resolution. • Higher frequencies provide better resolution, but sacrifice depth. LOWER FREQUENCY Longer wavelength HIGHER FREQUENCY Shorter wavelength

Transducer Function • Ultrasound waves are generated by an electric current -> sent to the crystals -> excites the crystals which vibrate -> creating the resulting wave in the tissue • Beam is ~ 1mm

Transducer Characteristics • The workhorse of the US machine • Sends out sound waves 1% of the time • Listens for echoes 99% of the time • Frequencies are fixed or adjustable • “Footprint” is what touches the patient

Transducer Use • Hold the probe lightly in your hand • Like a pencil • Small movements equal big changes

Transducer Use • Probe marker facing the patient’s right or head • Exceptions: cardiac & procedures

Probe indicator – leading edge Generally to the patient’s head or right side.

Transducer Choices • Curvilinear Array (Curved Probe) • Freq range (5-2 MHz), 30cm depth • Abdomen, FAST, AAA • Linear Sequential Array (Linear Probe) • Freq range (10-5 MHz), 9cm depth • Vascular access, pneumothorax, regional anesthesia • Phased Array (Sector or Cardiac Probe) • Freq range (5-1 MHz), 35cm depth • Cardiac, eFAST, AAA

Transducer directions • Rotating • Fanning/Tilting • Rocking • Sliding • Compression

Transducer directions • Sliding

Transducer directions • Fanning/Tilting • Compression

Transducer directions • Rotation • Rocking

Scanning Planes

Scanning Planes Sagittal Axial

Screen Orientation Near Field Receding Edge Leading Edge Far Field

Image Quality – The 5 P’s • Use Plenty of Gel • Parallel to the table/stretcher • Perpendicular to structure • Pressure (right amount) • Scan in multiple Planes

Gel & Water Stand-offs

Ultrasound transmission gel USE LOTS OF IT!!!

Image Quality - Machine • Depth: Place the object of interest in the center of the screen • Machine will autofocus to the center of the screen giving it the best resolution • Right side markings show depth in cm • Gain: brightness of the image • Can be adjusted for each scan • Be careful not to use too much or too little gain • Autogain

Depth Too Little Too Much

Depth – JUST RIGHT!

Gain Too Little Too Much

Gain – Just Right!

Image Resolution • Spatial Resolution • The ability to distinguish two separate objects close together • Temporal Resolution • The ability to accurately locate structures or events at a specific point in time • Can be improved by decreasing depth & narrowing the sector angle

Spatial Resolution Axial Lateral The ability to distinguish two objects that are laying side-by-side Dependent upon the beam width Two objects cannot be distinguished if they are separated by less than the beam width High freq = narrow width Low freq = wider width • The ability to differentiate two separate objects in the axial plane • Determined by the pulse length • High freq = short length & better axial resolution • Low freq = long length and poor axial resolution

Scanning Modes • B-Mode: • Nearly all of your scans will begin and stay in this mode • Organs appear differently based on their tissue densities

Scanning Modes • M-Mode: • Motion mode provides a reference line on screen • Shows motion towards and away from probe at any depth along that line • Used for detecting fetal heartbeatsand pneumothoracies

Scanning Modes Spectral Doppler Color Flow Doppler Blue – Away : Red – Towards Power Doppler

Attenuation • As the ultrasound beam travels through the body, it looses strength & returns less signal • Certain tissue densities cause this effect: • Slow: Bone, Diaphragm, Pericardium & air = bright (Hyperechoic) images • Moderate: Muscle, Liver, Kidney = gray (Isoechoic) images • Faster: Blood, Ascites, Urine = Darker (Hypoechoic) images

Artifacts • Posterior Enhancement • Reverberation • Edge Artifact • Shadowing • Mirror Image • Comet Tail

Posterior Enhancement Hyperechoic streaking distal to interface of anechoic structure Not a true artifact

Reverberation Bouncing of signal from two reflective surfaces Often seen as a “needle artifact” during procedural ultrasound Called “Ring Down artifact” when seen with air in the bowel or soft tissue

Edge Artifact A distal shadow from the edge of spherical fluid filled structures Scan at different angles to reduce the artifact

Shadowing Anechoic streaking distal to surface with high reflectivity (behaves like light) Stones Bones

Mirror Image Appearance of same image on both sides of highly reflective surface Misinterpretation by machine of signal timing puts image where it thinks it “should be” Often seen on cardiac and around diaphragm

Comet Tail Pathognomonic for excluding pneumothorax

- More by User

BASIC PRINCIPLES

BASIC PRINCIPLES You cannot sell from an empty wagon! Private sector development of industrial/business parks may be adequate. If not, there is a compelling need for local economic development programs to fill the need. STATUTORY AUTHORITY N.C.G.S. §158-7.1(a) provides:

624 views • 19 slides

Basic Principles of GMP

Basic Principles of GMP. Complaints and Recalls. Sections 5 and 6. Complaints and Recalls. Objectives To identify the key issues in product complaint and recall handling To understand the specific requirements for organization, procedures and resources

602 views • 22 slides

Principles of Ultrasound

Types of Ultrasound. Diagnostic (20,000 Hz 750,000 Hz)Therapeutic (.75 MHz 3 MHz)Surgical (3 MHz 10 GHz)Human ear can hear (16-20,000 Hz). Definition. Ultrasound is a deep penetrating modality capable of producing thermal and non-thermal effectsProduced by an alternating current (AC) flow

842 views • 27 slides

Basic Principles of Assessment

Basic Principles of Assessment. Communicating Assessment Results. Feedback Sessions. Oral or written Comprehensible and useful Need to consider: Purposes of assessment What does it mean to the test taker, education, career…. Should be soon after assessment.

475 views • 5 slides

Basic Principles

Basic Principles. Learning objectives. Understand the basic principles undelying A&T techniques Grasp the motivations and applicability of the main principles. Main A&T Principles . General engineering principles: Partition: divide and conquer Visibility: making information accessible

539 views • 10 slides

BASIC ULTRASOUND OF THE KNEE

BASIC ULTRASOUND OF THE KNEE. By Mohamed Hassan Youssef MD Arthritis/ Rehab&Pain Clinic Board certified of ABPM&R. Knee Joint. Knee Bones. Distal end of the F umer Proximal end of the Tibia Head of the Fibula Patella. Knee Bones. Knee Bones. Movement of Patella Upward

968 views • 40 slides

Basic Principles of Ultrasound Imaging

Basic Principles of Ultrasound Imaging. Introduction Ultrasound imaging have different meaning to to different categories of people based on profession or vocation In the Heath Sector- Clinicians, Patients

7.7k views • 17 slides

NMM Dynamic Core and HWRF Zavisa Janjic and Matt Pyle NOAA/NWS/NCEP/EMC , NCWCP, College Park, MD . Basic Principles. Forecast accuracy Fully compressible equations Discretization methods that minimize generation of computational noise and reduce or eliminate need for numerical filters

558 views • 39 slides

Introduction to NMMB Dynamics: How it differs from WRF-NMM Dynamics Zavisa Janjic NOAA/NWS/NCEP/EMC , College Park, MD . Basic Principles. Forecast accuracy Fully compressible equations

781 views • 60 slides

Basic Principles of Learning

Basic Principles of Learning. Basic Principles of Learning. Definition of Learning. Relative permanent change in behavior brought about through experience or interactions with the environment Not all changes result from learning Change in behavior not always immediate

978 views • 39 slides

Principles of Medical Ultrasound

Principles of Medical Ultrasound. Pai-Chi Li Department of Electrical Engineering National Taiwan University. What is Medical Ultrasound?. Prevention : actions taken to avoid diseases.

1.47k views • 81 slides

Basic Principles. No action will occur unless electrical current is flowing No current will flow unless it finds a complete loop out from the source and back to it Current will flow through any and all available loops, although not equally Heating occurs as current flows, due to resistance.

917 views • 46 slides

Basic Principles. We are taking a USER perspective, not a PREPARER perspective. Basic Principles. The Accounting Entity The business unit for which the financial statements are being prepared. Basic Principles. Going Concern

430 views • 13 slides

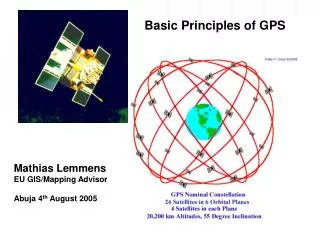

Basic Principles of GPS

Basic Principles of GPS. Mathias Lemmens EU GIS/Mapping Advisor Abuja 4 th August 2005. Contents. Introduction GPS as a surveying tool Methods of Observation Accuracy Aspects Sources of GPS Error. Global Positioning System (GPS).

1.34k views • 43 slides

Basic Principles of Nutriton

Basic Principles of Nutriton. Prof. Dr. Ahmet AYDIN İÜ Cerrahpaşa Tıp Fak. Çocuk Sağlığı ve Hastalıkları ABD Metabolizma ve Beslenme Bilim Dalı Başkanı (www.beslenmebulteni.com) ([email protected]). NUTRITIONAL REQUIREMENTS.

939 views • 73 slides

Basic Principles Of WTO

Non-discriminatory Principle Principle of Tariff Concession Principle of Trade Protection Principle of Trade Facilities,Transparency and Competition Protection. Basic Principles Of WTO. Non-discriminatory Principle. Principle of Most-Favoured-Nation Treatment MFN

1.68k views • 15 slides

Basic Principles of Ultrasound Imaging. Summarized by: Name: AGNES Purwidyantri Student ID number: D0228005 Biomedical Engineering Dept. Ultrasound. Sound waves above 20 KHz are usually called as ultrasound waves.

1.73k views • 22 slides

Basic Physics of Ultrasound

Basic Physics of Ultrasound. WHAT IS ULTRASOUND?. Ultrasound or ultrasonography is a medical imaging technique that uses high frequency sound waves and their echoes. Known as a ‘pulse echo technique’

1.11k views • 17 slides

Principles of Medical Ultrasound. Zahra Kavehvash. Medical Ultrasound Course (25-636). Introduction Acoustic wave propagation Acoustic waves in fluids Acoustic waves in solids Attenuation and dispersion Reflection and Transmission Transducers Beam forming and Diffraction

746 views • 58 slides

Basic Principles of GMP. Equipment. 13. Equipment. Objectives To review the requirements for equipment selection design use maintenance To discuss problems related to issues around selected items of equipment. Equipment. Principle Equipment must be l ocated designed

599 views • 26 slides

Basic Principles of Neuropharmacology

Chapter 12. Basic Principles of Neuropharmacology. Basic Principles of Neuropharmacology. Neuropharmacology is the study of drugs that alter processes controlled by the nervous system. Neuropharmacologic Agents. There are two categories of neuropharmacologic agents

260 views • 7 slides

Basic Principles in Management Accounting

332 views • 8 slides

CME Tracker

Music, Advanced Medicine, and Robotics Merge in Groundbreaking UltraCon 2024 Ultrasound Presentations

Dr. Omar Ishrak and Dr. Gil Weinberg to Headline Medical Tech Conference

AUSTIN, Texas, March 26, 2024 /PRNewswire/ -- The upcoming UltraCon 2024 conference , organized by the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM), is set to spotlight groundbreaking advancements in medical technology with keynotes from industry luminaries Dr. Omar Ishrak and Dr. Gil Weinberg. This premier event, taking place from April 6–10 in Austin, Texas, will draw professionals from across the medical imaging spectrum to discuss the future of ultrasound technology and its applications.

"With visionaries like Dr. Ishrak and Dr. Weinberg leading our keynote sessions, we're not just looking at the future of ultrasound; we're actively shaping it," said Dr. Richard Hoppmann, MD, FACP, FAIUM, President of the AIUM. "Their groundbreaking work exemplifies the spirit of innovation that drives our field forward, offering new ways to enhance patient care and improve lives."

Known for his transformative leadership at Medtronic and GE Healthcare Systems, Dr. Ishrak has been a central figure in the advancement of medical technology, consistently championing the expansion and integration of ultrasound technology across various facets of healthcare. In his upcoming presentation, "Views on the Future of Ultrasound Technology," Dr. Ishrak will provide a comprehensive overview of ultrasound technology—from technical innovations to its critical role in clinical improvement and its strategic importance in the healthcare ecosystem. He will also highlight the remarkable opportunities it presents for widespread application and accessibility, as well as discuss the expanding use of ultrasound not only in diagnostics but also in enhancing clinical outcomes.

"The future of ultrasound technology lies at the intersection of innovation and patient care," stated Dr. Ishrak. "Ultrasound will play a significant role in shaping the future of healthcare, and at UltraCon 2024, I look forward to exploring how advancements in imaging can redefine what's possible in diagnostics and treatment."

Attendees can also look forward to insights on the application of high-intensity ultrasound as a direct form of therapy, and how the innovative combination of high-intensity ultrasound with pharmaceutical approaches—like liquid biopsy and the increased permeability of the blood-brain barrier—can revolutionize patient care.

Also taking the stage will be Dr. Weinberg, whose keynote, "Sonic Prosthetics: Giving Amputees Robotic Arms That Play By Ear," will explore the intersection of robotics, music, and prosthetics. Dr. Weinberg's pioneering work in developing prosthetic robotic arms for amputees demonstrates a novel use of ultrasound signals to control robotic limbs with unparalleled precision and musicality. This innovative approach not only advances prosthetic technology but also opens new possibilities for amputees to engage in musical creation, showcasing the potential of robotics to enhance human expression and rehabilitation.

"By harnessing the power of ultrasound and machine learning, we aim to provide amputees not just with new limbs, but with new possibilities for expression and interaction," said Dr. Weinberg. "This innovative approach exemplifies the incredible advancements we can achieve when we blend technology with the human spirit of resilience and creativity, and I'm excited to share my learnings with UltraCon attendees in Austin."

As UltraCon 2024 prepares to welcome attendees in Austin, it sets the stage for discussions that will likely shape the trajectory of medical technology in the years to come. With its focus on innovation, the conference is poised to highlight the transformative impact of advanced technologies on medical diagnostics, treatment, and patient care.

For registration and additional information about UltraCon 2024, please visit https://ultracon2024. eventscribe.net/ .

For a list of all UltraCon 2024 exhibitors, please visit this link .

The American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine is a multidisciplinary medical association of more than 9,000 physicians, sonographers, scientists, students, and other healthcare professionals. Established in the early 1950s, AIUM is dedicated to empowering and cultivating a global multidisciplinary community engaged in the use of medical ultrasound through raising awareness, education, sharing information, and research.

LATEST NEWS

- Mar 26, 2024 Music, Advanced Medicine, and Robotics Merge in Groundbreaking UltraCon 2024 Ultrasound Presentations Dr. Omar Ishrak and Dr. Gil Weinberg to Headline Medical Tech Conference

- Mar 5, 2024 At UltraCon 2024, the Latest Breakthroughs in Ultrasound Technology Take Center Stage The American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM) has announced UltraCon 2024, a gathering that promises to bring together the brightest minds in ultrasound technology.

- Aug 3, 2023 Pulsenmore Wins the AIUM's Shark Tank Competition at UltraCon, Showcasing Revolutionary Patient-Centered Home Ultrasound Solution Pulsenmore, a leading innovator in connected patient-driven home ultrasound, emerged victorious in the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine’s first-ever Shark Tank competition held this past March at UltraCon this year in Orlando, Florida.

- Mar 30, 2023 AIUM New Leaders Take Office Members of the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM) have elected a new slate of leaders to the Executive Committee, Board of Governors, and Communities of Practices. These leaders, from across the country and around the world, will work to support the AIUM’s mission and vision.

- Mar 30, 2023 AIUM Names National Awards Recipients The American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine (AIUM) is proud to recognize the following doctors, researchers, sonographers, and educators as its 2023 class of national award recipients.

Partner with Us | Press | Privacy Policy | Contact Us

14750 Sweitzer Lane, Suite 100, Laurel, MD 20707 301-498-4100 © American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit educational organization. All Rights Reserved.

Web Design & Development by Matrix Group International, Inc .

- Alzheimer's disease & dementia

- Arthritis & Rheumatism

- Attention deficit disorders

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Biomedical technology

- Diseases, Conditions, Syndromes

- Endocrinology & Metabolism

- Gastroenterology

- Gerontology & Geriatrics

- Health informatics

- Inflammatory disorders

- Medical economics

- Medical research

- Medications

- Neuroscience

- Obstetrics & gynaecology

- Oncology & Cancer

- Ophthalmology

- Overweight & Obesity

- Parkinson's & Movement disorders

- Psychology & Psychiatry

- Radiology & Imaging

- Sleep disorders

- Sports medicine & Kinesiology

- Vaccination

- Breast cancer

- Cardiovascular disease

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Colon cancer

- Coronary artery disease

- Heart attack

- Heart disease

- High blood pressure

- Kidney disease

- Lung cancer

- Multiple sclerosis

- Myocardial infarction

- Ovarian cancer

- Post traumatic stress disorder

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Schizophrenia

- Skin cancer

- Type 2 diabetes

- Full List »

share this!

April 2, 2024

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

peer-reviewed publication

trusted source

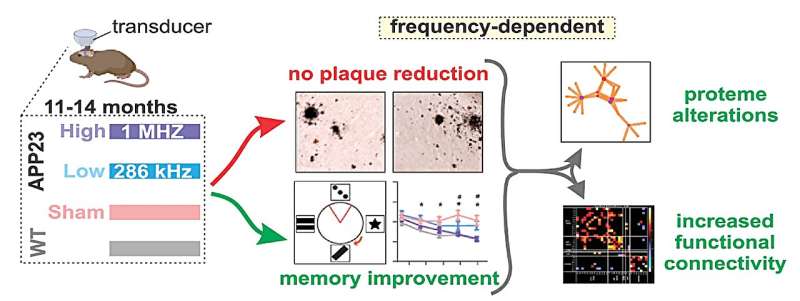

Ultrasound therapy shows promise as a treatment for Alzheimer's disease

by University of Queensland

University of Queensland researchers have found targeting amyloid plaque in the brain is not essential for ultrasound to deliver cognitive improvement in neurodegenerative disorders.

Dr. Gerhard Leinenga and Professor Jürgen Götz from UQ's Queensland Brain Institute (QBI) said the finding challenges the conventional notion in Alzheimer's disease research that targeting and clearing amyloid plaque is essential to improve cognition.

"Amyloid plaques are clumps of protein that can build up in the brain and block communication between brain cells , leading to memory loss and other symptoms of Alzheimer's disease," Dr. Leinenga said.

"Previous studies have focused on opening the blood-brain barrier with microbubbles, which activate the cell type in the brain called microglia which clears the amyloid plaque .

"But we used scanning ultrasound alone on mouse models and observed significant memory enhancement."

Dr. Leinenga said the finding shows that ultrasound without microbubbles can induce long-lasting cognitive changes in the brain, correlating with memory improvement. The research paper has been published in Molecular Psychiatry .

"Ultrasound on its own has direct effects on the neurons, with increased plasticity and improved brain networks," he said.

"We think the ultrasound is increasing the plasticity or the resilience of the brain to the plaques, even though it's not specifically clearing them."

Professor Götz said the study also revealed the effectiveness of ultrasound therapy varied depending on the frequency used.

"We tested two types of ultrasound waves, emitted at two different frequencies," he said. "We found the higher frequency showed superior results, compared to frequencies currently being explored in clinical trials for Alzheimer's disease patients."

The researchers hope to incorporate the findings into Professor Götz's pioneering safety trial using non-invasive ultrasound to treat Alzheimer's disease.

"By understanding the mechanisms underlying ultrasound therapy, we can tailor treatment strategies to maximize cognitive improvement in patients," Dr. Leinenga said.

"This approach represents a significant step toward personalized, effective therapies for neurodegenerative disorders."

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Researchers predict real-world SARS-CoV-2 evolution by monitoring mutations of viral isolates

48 minutes ago

New study targets major risk factor for gastric cancer

57 minutes ago

In people with opioid use disorder, telemedicine for HCV was more than twice as successful as off-site referral

Researchers find genetic variant coding for tubulin protein that may be partially responsible for left-handedness

A molecular route to decoding synaptic specificity and nerve cell communication

Hope for treating autoimmune diseases: Researchers explore diagnostic role of the systemic inflammation index

3 hours ago

Testing environmental water to monitor COVID-19 spread in unsheltered encampments

Dogs may provide new insights into human aging and cognition

18 hours ago

AI's ability to detect tumor cells could be key to more accurate bone cancer prognoses

19 hours ago

Novel pre-clinical models help advance therapeutic development for antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections

Related stories.

Potential noninvasive treatment for Alzheimer's disease

Jun 23, 2021

Ultrasound and drug research holds promise for Alzheimer's disease

Apr 5, 2017

Using focused ultrasound to treat Alzheimer's and Parkinson's

Sep 13, 2023

More evidence ultrasound can help in battle against Alzheimer's disease

Apr 10, 2020

Alzheimer's drugs might get into the brain faster with new ultrasound tool, study shows

Jan 4, 2024

New brain stimulation technique shows promise for treating brain disorders

Feb 23, 2024

Recommended for you

Early cortical remyelination has a neuroprotective effect in multiple sclerosis, study shows

Apr 2, 2024

Novel compound AC102 restores hearing in preclinical models of sudden hearing loss

YKT6 gene variants cause a new neurological disorder, finds study

'Zombie neurons' shed light on how the brain learns

Playtime, being social helps a dog's aging brain, study finds

Let us know if there is a problem with our content.

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Medical Xpress in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

- Open access

- Published: 29 March 2024

A feasibility study of a handmade ultrasound-guided phantom for paracentesis

- Chien-Tai Huang 1 , 2 ,

- Chih-Hsien Lin 2 ,

- Shao-Yung Lin 2 ,

- Sih‑Shiang Huang 2 &

- Wan-Ching Lien 2 , 3

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 351 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

58 Accesses

Metrics details

Simulation-based training is effective for ultrasound (US)-guided procedures. However, commercially developed simulators are costly. This study aims to evaluate the feasibility of a hand-made phantom for US-guided paracentesis.

We described the recipe to prepare an agar phantom. We collected the US performance data of 50 novices, including 22 postgraduate-year (PGY) residents and 28 undergraduate-year (UGY) students, who used the phantom for training, as well as 12 emergency residents with prior US-guided experience. We obtained the feedback after using the phantom with the Likert 5-point scale. The data were presented with medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) and analyzed by the Wilcoxon rank sum test.

While emergency residents demonstrated superior performance compared to trainees, all trainees exhibited acceptable proficiency (global rating of ≥ 3, 50/50 vs. 12/12, p = 1.000) and comparable needle steadiness [5 (5) vs. 5 (5), p = 0.223]. No significant difference in performance was observed between PGYs [5 (4–5)] and UGYs [5 (4–5), p = 0.825]. No significant differences were observed in terms of image stimulation, puncture texture, needle visualization, drainage simulation, and endurance of the phantom between emergency residents and trainees. However, experienced residents rated puncture texture and draining fluid as “neutral” (3/5 on the Likert scale). The cost of the paracentesis phantom is US$16.00 for at least 30 simulations, reducing it to US$6.00 without a container.

Conclusions

The paracentesis phantom proves to be a practical and cost-effective training tool. It enables novices to acquire paracentesis skills, enhances their US proficiency, and boosts their confidence. Nevertheless, further investigation is needed to assess its long-term impact on clinical performance in real patients.

Trial registration

NCT04792203 at the ClinicalTrials.gov.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Clinical procedures involve a complex combination of technical skills and cognitive decision-making. Achieving expert performance and sustaining skills necessitate deliberate practice [ 1 ]. Traditionally, procedural skills were acquired, and experience accumulated through direct application on real patients. However, concerns about patient safety and rights have escalated with inexperienced physicians performing procedures directly on patients. Simulation-based medical education provides an alternative for skill proficiency [ 2 ], particularly in ultrasound (US)-guided procedures [ 3 ].

Paracentesis is a commonly encountered procedure in clinical practice. The use of ultrasound guidance diminishes the risk of a dry tap (failure to obtain fluid) during paracentesis and reduces the likelihood of complications such as bleeding, abdominal hematoma, and puncture site infection [ 4 , 5 ]. Additionally, US-guided procedures are integral to emergency medicine training [ 6 ]. However, commercially developed simulators for US-guided procedures are often prohibitively expensive for many emergency departments.

An increasing number of low-cost, handmade phantoms have been developed for US-guided biopsy, thoracocentesis, and pericardiocentesis [ 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. However, options for paracentesis remain limited [ 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Furthermore, more evidence is needed to assess the learning impact of using handmade phantoms for paracentesis training. This study aims to evaluate the feasibility of a handmade phantom for US-guided paracentesis.

This prospective study was conducted at the Emergency Department of the National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH) from August 2022 to July 2023. It was approved by the institutional review board of the NTUH (202011111RIND) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT04792203). Informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Phantom preparation

Agar substrate

The agar substrate was created by dissolving 10 g of agar powder in 1000 cc of water. After thorough heating to melt the agar powder, the solution underwent filtration to remove impurities. The resulting clear solution was tinted with dark blue food coloring additives.

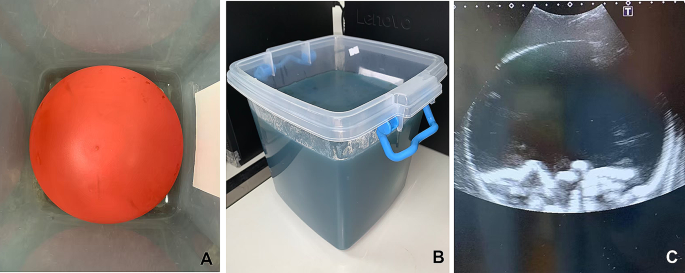

Paracentesis phantom

A cotton rope, at least 30 cm in length, was inserted into a 10-inch balloon to simulate the bowel. The balloon was then filled with yellowish water dyed with food coloring additives to mimic ascites. After tying the balloon securely, it was affixed to the bottom of the container using super glue (Fig. 1 A). The balloon was covered with the agar substrate, replicating the appearance of human skin and the subcutaneous area. The thickness of the covering could be adjusted based on different body habitus. The phantom was refrigerated for a minimum of 4 h to enhance its longevity (Fig. 1 B).

( A ) The balloon was tied in the container; ( B ) The phantom; ( C ) The simulated sonographic image of the phantom

The resulting phantom exhibited easily distinguishable echogenic structures (Fig. 1 C, Supplementary Video ). The balloon effectively delineated boundaries between the peritoneum and the subcutaneous area.

US-guided paracentesis using the hand-made phantom

We recruited 50 trainees, comprising 22 postgraduate-year 1 (PGY-1) residents and 28 undergraduate-year (UGY) students, for participation in a US training curriculum. To assess their experience and confidence in using US, the trainees completed a survey using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not confident at all; 2 = slightly confident; 3 = somewhat confident; 4 = fairly confident; 5 = completely confident). Subsequently, they attended a 30-minute didactic session covering the theory of US and US-guided paracentesis, followed by small-group hands-on training utilizing the agar phantom. The instructors, were certified by the Taiwan Society of Emergency Medicine.

Following the curriculum, all trainees underwent a skill test, performing paracentesis. The performance was evaluated using an assessment form (Table 1 ) in which the items of the assessment was developed to to encompass the training domains based on expert consensus. Three experts, certified by the Taiwan Society of Emergency Medicine and with over 10 years of US experience, participated in establishing this consensus.

Two independent evaluators, not involved in enrollment and training, graded the performance—one on-site, and the other assessed video recordings with trainee faces masked. Subsequently, trainees provided feedback on the phantom through a survey using a 5-point Likert scale (Supplementary Table 1 ).

Additionally, 12 emergency residents were enrolled to use the phantom without didactics and hands-on training. Their performance was graded, and a survey regarding the phantom was collected.

US machines (Xario 100, Canon, Japan, and Arietta 780, Fujifilm Healthcare, Japan) equipped with a 2–5 MHz curvilinear transducer were used.

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed by SAS software (SAS 9.4, Cary, North Carolina, USA). Initially, we conducted the Shapiro-Wilk test to assess the normality of continuous data. If the data did not follow a normal distribution, it was presented using medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). For the comparison between residents and trainees, as well as between PGYs and UGYs, we employed Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test.

To assess inter-rater reliability between two evaluators for the items on the assessment form and global scores, we utilized the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The Spearman correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the relationship between the total score and the global score. The total score represented the sum of each item on the assessment form. The internal reliability of the assessment form was estimated by employing Cronbach’s alpha coefficient [ 21 ]. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Following the assessment of normality, it was determined that the scores for each item on the assessment form, the global score, and feedback to the phantom were not normally distributed (all p < 0.0001). Therefore, these data were reported using medians and IQRs.

US performance

The 50 trainees were all considered US novices (Table 2 ). The 12 emergency residents had previous experience with US-guided paracentesis on more than 20 real patients. The ICC for the global score was 0.94 (95% CI, 0.90–0.96), indicating strong inter-rater reliability, as was observed for the items on the checklist (Supplementary Table 2 ). The Spearman correlation coefficient was 0.79 (95% CI, 0.67–0.87) between the total score and the global score, indicative of strong correlation. The standardized Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.75, suggesting good internal reliability.

While the performance of emergency residents surpassed that of trainees, all trainees demonstrated acceptable performance (global rating of ≧ 3). Trainees exhibited less familiarity with US-guided localization, visualization of the needle, and fluid aspiration (Table 2 ). No significant differences were found in the performance between PGYs and UGYs (Supplementary Table 3 ).

There were no significant differences observed in terms of image stimulation, puncture texture, needle visualization, drainage simulation, and endurance of the phantom between emergency residents and trainees. However, it is noteworthy that the residents rated puncture texture and draining fluid as “neutral (Table 3 ). Trainees reported increased confidence in paracentesis after using the phantom, compared with their pre-curriculum survey [4 (3–5) vs. 1 (1), p < 0.0001].

The US phantom could be utilized at least 30 times for practicing paracentesis within one curriculum. The cost of the handmade phantom with a container was approximately $16. Without the container, the cost was reduced to approximately $6.

Commercial US phantoms for paracentesis remain extremely expensive rendering them inaccessible for many training centers. Inexpensive, do-it-yourself phantoms play a crucial role in paracentesis training. In this study, we presented a low-cost, and easily reproducible phantom with echogenicity similar to human tissue and proved its feasibility. Utilizing the phantom facilitates the acquisition of paracentesis skills among novices, enhancing their US abilities and boosting their confidence. While novices demonstrated acceptable performance in paracentesis, it still lags behind that of experienced residents.

Apart from their higher cost, commercial phantoms may degrade with repeated use, requiring an additional fee for fixation. These phantoms typically incorporate polymers, resulting in an excessively firm texture. In contrast, our agar phantom, while having a semi-firm texture that may not perfectly replicate human skin, received a median rating ranging from 3 to 4 from experienced emergency residents in terms of feedback, encompassing image stimulation, puncture texture, needle visualization, and drainage simulation.

Reviewing the literature, some examples of inexpensive, handmade paracentesis phantoms were reported. Wilson et al. documented a gelatin phantom [ 18 ], and Kei et al. employed a water jug covered with pork belly [ 20 ]. Mesquita et al. used multiple gloves filled with various colors to simulate ascites and abdominal organs, elucidating students’ perceptions of the simulator [ 19 ]. In our study, we contribute additional evidence supporting the viability of a handmade phantom, reporting on the performance and feedback of novices in comparison to experienced residents.

Moreover, our phantom exhibited variability and flexibility. For instance, the fluid within the phantom could be altered to appear red or include debris content (such as adding talc), replicating hemoperitoneum or pus, respectively. Additionally, the ratio of fluid to ropes could be adjusted to simulate either a small or a large amount of ascites, depending on the desired training difficulty.

Lower-fidelity modalities are designed to concentrate on a specific learning task and skill acquisition, making them suitable for early learners or novices. In contrast, higher-fidelity simulations are employed for complex tasks, providing cognitive stimuli [ 1 ]. Our handmade phantom is a tool with lower fidelity in external appearance but exhibits high fidelity in ultrasound appearance, making it well-suited for paracentesis training, with novices demonstrating proficiency after completing the curriculum. It is important to note that the long-term impact on skill retention and the translation of acquired skills to proficiency in clinical settings remains unknown.

Gelatin is frequently employed as the primary substrate for homemade phantoms in ultrasound training [ 12 , 18 , 22 ]. However, gelatin necessitates refrigeration to solidify the model. In contrast, agar serves as a vegan-friendly alternative that can set the model without the need for refrigeration. Agar is capable of producing an ultrasound image that closely mimics real tissue and is durable enough to withstand high-volume training [ 23 ]. In this study, we opted for agar as the substrate, and the resulting echogenicity was deemed acceptable.

The assessment form was developed through expert consensus to ensure content validity. Our results also demonstrated good internal and interrater reliability of the assessment form. Research indicates that global rating scales effectively capture various proficiency levels compared to checklists and are user-friendly for examiners [ 24 ]. In this study, the global rating score was utilized to evaluate performance in conjunction with the items on the assessment form.

The main limitation of this study was the inclusion of trainees and emergency residents from a single institution, who voluntarily participated and exhibited high motivation, potentially introducing selection bias. Therefore, caution should be exercised when generalizing these results. Secondly, the study involved a substantial amount of labor and time, approximately 30–60 min for agar preparation and an additional 30 min for phantom assembly, which could limit its feasibility due to time constraints. Third, there may be a potential issue with the image quality of the phantom, as a small amount of air might have been introduced into the balloon during fluid aspiration. However, both trainees and residents reported acceptable image quality. Fourth, while the trainees had prior experience in blood drawing and needle catheterization through routine medical training, feedback concerning human tissue and draining sensation should be interpreted cautiously. Notably, residents with real-world experience rated “neutral” on aspects such as “puncture texture mimics human skin and subcutaneous area” and “draining fluid is realistic.” Lastly, the focus of this study was on evaluating the feasibility of the phantom. Factors such as skill retention and the clinical performance of trainees in real-world scenarios were not investigated. Additionally, the learning effect of using handmade phantoms was not compared with that of using commercial phantoms due to the latter’s high cost. These aspects should be addressed in future studies.

The paracentesis phantom proves to be a practical and cost-effective training tool. It facilitates the acquisition of paracentesis skills among novices, enhancing their US abilities and boosting their confidence. Nevertheless, further investigation is needed to assess its skill retention and long-term impact on clinical performance in real patients.

Data availability

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

Wang EE, Quinones J, Fitch MT, Dooley-Hash S, Griswold-Theodorson S, Medzon R, Korley F, Laack T, Robinett A, Clay L. Developing technical expertise in emergency medicine–the role of simulation in procedural skill acquisition. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(11):1046–57.

Article Google Scholar

Bradley P. The history of simulation in medical education and possible future directions. Med Educ. 2006;40:254–62.

Giannotti E, Jethwa K, Closs S, Sun R, Bhatti H, James J, Clarke C. Promoting simulation-based training in radiology: a homemade phantom for the practice of ultrasound-guided procedures. Br J Radiol. 2022;95(1137):20220354.

Patel PA, Ernst FR, Gunnarsson CL. Evaluation of hospital complications and costs associated with using ultrasound guidance during abdominal paracentesis procedures. J Med Econ. 2012;15(1):1–7.

Mercaldi CJ, Lanes SF. Ultrasound guidance decreases complications and improves the cost of care among patients undergoing thoracentesis and paracentesis. Chest. 2013;143(2):532–8.

ACEP. Ultrasound guidelines: Emergency, Point-of-care and clinical Ultrasound guidelines in Medicine. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(5):e27–54.

James V, Kee CY, Ong GY. A homemade, high-fidelity Ultrasound Model for simulating pneumonia with Parapneumonic Effusion and Empyema. J Emerg Med. 2019;56(4):421–5.

Sullivan A, Khait L, Favot M. A novel low-cost ultrasound-guided Pericardiocentesis Simulation Model: demonstration of feasibility. J Ultrasound Med. 2018;37(2):493–500.

Fredfeldt KE. An easily made ultrasound biopsy phantom. J Ultrasound Med. 1986;5(5):295–7.

McNamara MPJ, McNamara ME. Preparation of a homemade ultrasound biopsy phantom. J Clin Ultrasound. 1989;17(6):456–8.

Silver B, Metzger TS, Matalon TA. A simple phantom for learning needle placement for sonographically guided biopsy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1990;154(4):847–8.

Wilson J, Myers C, Lewiss RE. A low-cost, easy to make ultrasound phantom for training healthcare providers in pleural fluid identification and task simulation in ultrasoundguided thoracentesis. Visual J Emerg Med. 2017;8:80–1.

Do HH, Lee S. A low-cost training Phantom for Lung Ultrasonography. Chest. 2016;150(6):1417–9.

Zerth H, Harwood R, Tommaso L, Girzadas DV Jr. An inexpensive, easily constructed, reusable task trainer for simulating ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis. J Emerg Med. 2012;43(6):1066–9.

Daly R, Planas J, Edens M. Adapting Gel Wax into an ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis model at low cost. Western J Emerg Med. 2017;18(1):114–6.

Young T, Kuntz H. Modification of Daly’s Do-it-yourself, Ultrasound-guided pericardiocentesis model for added external realism. Western J Emerg Med. 2018;19(3):465–6.

DIY Ultrasound Phantom Compendium. [ https://www.ultrasoundtraining.com.au/resources/diy-ultrasound-phantom-compendium/ )].

Wilson J, Wilson A, Lewiss RE. A low-cost, easy to make ultrasound phantom for training healthcare providers in peritoneal fluid identification and task simulation in ultrasound-guided paracentesis. Visual J Emerg Med. 2017;8:29–30.

de Mesquita DAK, Queiroz EF, de Oliveira MA, da Cunha CMQ, Maia FM, Correa RV. The old one technique in a new style: developing procedural skills in paracentesis in a low cost simulator model. Arq Gastroenterol. 2018;55(4):375–9.

Kei J, Mebust DP. Realistic and Inexpensive Ultrasound Guided Paracentesis Simulator Using Pork Belly with Skin. JETem 2018, 3(3):127–132.

Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334.

Aytaç BG, Ünal S, Aytaç I. A randomized, controlled simulation study comparing single and double operator ultrasound-guided regional nerve block techniques using a gelatine-based home-made phantom. Med (Baltim). 2022;101(35):e30368.

Earle M, Portu G, DeVos E. Agar ultrasound phantoms for low-cost training without refrigeration. Afr J Emerg Med. 2016;6(1):18–23.

Rajiah K, Veettil SK, Kumar S. Standard setting in OSCEs: a borderline approach. Clin Teach. 2014;11(7):551–6.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (MOST 110-2511-H-002-009-MY2) for financial support.

The Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 110-2511-H-002-009-MY2).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Emergency Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, Hsin-Chu Branch, Hsin-Chu, Taiwan

Chien-Tai Huang

Department of Emergency Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, No.7, Chung-Shan South Road, Taipei, 100, Taiwan

Chien-Tai Huang, Chih-Hsien Lin, Shao-Yung Lin, Sih‑Shiang Huang & Wan-Ching Lien

Department of Emergency Medicine, College of Medicine, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan

Wan-Ching Lien

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

CT and WC conceived the study and designed the trial. CT, CH, SY, SS, and WC acquisition of the data. CT and WC analysis and interpretation of the data. CT and WC drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. WC critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and took responsibility for the paper as a whole. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Wan-Ching Lien .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Research Ethics Committee of the National Taiwan University Hospital (202011111RIND). Informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Material 1

Supplementary material 2, supplementary material 3, supplementary material 4, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Huang, CT., Lin, CH., Lin, SY. et al. A feasibility study of a handmade ultrasound-guided phantom for paracentesis. BMC Med Educ 24 , 351 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05339-9

Download citation

Received : 07 October 2023

Accepted : 22 March 2024

Published : 29 March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05339-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Paracentesis

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.16(4); 2019 Apr

Screening for breech presentation using universal late-pregnancy ultrasonography: A prospective cohort study and cost effectiveness analysis

David wastlund.

1 Cambridge Centre for Health Services Research, Cambridge Institute of Public Health, Cambridge, United Kingdom

2 The Primary Care Unit, Department of Public Health and Primary Care, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Alexandros A. Moraitis

3 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Cambridge, NIHR Cambridge Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre, Cambridge, United Kingdom

Alison Dacey

Edward c. f. wilson.

4 Health Economics Group, Norwich Medical School, University of East Anglia, Norwich, United Kingdom

Gordon C. S. Smith

Associated data.

The terms of the ethical permission for the POP study do not allow publication of individual patient level data. Requests for access to patient level data will usually require a Data Transfer Agreement, and should be made to Mrs Sheree Green-Molloy at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Cambridge University, UK ( ku.ca.mac.lhcsdem@dohgdnaoap ).

Despite the relative ease with which breech presentation can be identified through ultrasound screening, the assessment of foetal presentation at term is often based on clinical examination only. Due to limitations in this approach, many women present in labour with an undiagnosed breech presentation, with increased risk of foetal morbidity and mortality. This study sought to determine the cost effectiveness of universal ultrasound scanning for breech presentation near term (36 weeks of gestational age [wkGA]) in nulliparous women.

Methods and findings

The Pregnancy Outcome Prediction (POP) study was a prospective cohort study between January 14, 2008 and July 31, 2012, including 3,879 nulliparous women who attended for a research screening ultrasound examination at 36 wkGA. Foetal presentation was assessed and compared for the groups with and without a clinically indicated ultrasound. Where breech presentation was detected, an external cephalic version (ECV) was routinely offered. If the ECV was unsuccessful or not performed, the women were offered either planned cesarean section at 39 weeks or attempted vaginal breech delivery. To compare the likelihood of different mode of deliveries and associated long-term health outcomes for universal ultrasound to current practice, a probabilistic economic simulation model was constructed. Parameter values were obtained from the POP study, and costs were mainly obtained from the English National Health Service (NHS). One hundred seventy-nine out of 3,879 women (4.6%) were diagnosed with breech presentation at 36 weeks. For most women (96), there had been no prior suspicion of noncephalic presentation. ECV was attempted for 84 (46.9%) women and was successful in 12 (success rate: 14.3%). Overall, 19 of the 179 women delivered vaginally (10.6%), 110 delivered by elective cesarean section (ELCS) (61.5%) and 50 delivered by emergency cesarean section (EMCS) (27.9%). There were no women with undiagnosed breech presentation in labour in the entire cohort. On average, 40 scans were needed per detection of a previously undiagnosed breech presentation. The economic analysis indicated that, compared to current practice, universal late-pregnancy ultrasound would identify around 14,826 otherwise undiagnosed breech presentations across England annually. It would also reduce EMCS and vaginal breech deliveries by 0.7 and 1.0 percentage points, respectively: around 4,196 and 6,061 deliveries across England annually. Universal ultrasound would also prevent 7.89 neonatal mortalities annually. The strategy would be cost effective if foetal presentation could be assessed for £19.80 or less per woman. Limitations to this study included that foetal presentation was revealed to all women and that the health economic analysis may be altered by parity.

Conclusions

According to our estimates, universal late pregnancy ultrasound in nulliparous women (1) would virtually eliminate undiagnosed breech presentation, (2) would be expected to reduce foetal mortality in breech presentation, and (3) would be cost effective if foetal presentation could be assessed for less than £19.80 per woman.

In their cohort study, David Wastlund and colleagues find that universal ultrasound scanning for breech presentation near term is associated with reduced undiagnosed breech presentation and improved pregnancy outcomes, and can be cost-effective.

Author summary

Why was this study done.

- Risks of complications at delivery are higher for babies that are in a breech position, but sometimes breech presentation is not discovered until the time of birth.

- Ultrasound screening could be used to detect breech presentation before birth and lower the risk of complications but would be associated with additional costs.

- It is uncertain if offering ultrasound screening to every pregnancy is cost effective.

What did the researchers do and find?

- This study recorded the birth outcomes of pregnancies that were all screened using ultrasound.

- Economic modelling and simulation was used to compare these outcomes with those if ultrasound screening had not been used.

- Modelling demonstrated that ultrasound screening would lower the risk of breech delivery and, as a result, reduce emergency cesarean sections and the baby’s risk of death.

What do these findings mean?

- Offering ultrasound screening to every pregnancy would improve the health of mothers and babies nationwide.

- Whether the health improvements are enough to justify the increased cost of ultrasound screening is still uncertain, mainly because the cost of ultrasound screening for presentation alone is unknown.

- If ultrasound screening could be provided sufficiently inexpensively, for example, by being used during standard midwife appointments, routinely offering ultrasound screening would be worthwhile.

Introduction

Undiagnosed breech presentation in labour increases the risk of perinatal morbidity and mortality and represents a challenge for obstetric management. The incidence of breech presentation at term is around 3%–4% [ 1 – 3 ], and fewer than 10% of foetuses who are breech at term revert spontaneously to a vertex presentation [ 4 ]. Although breech presentation is easy to detect through ultrasound screening, many women go into labour with an undetected breech presentation [ 5 ]. The majority of these women will deliver through emergency cesarean section (EMCS), which has high costs and increased risk of morbidity and mortality for both mother and child.