Sustainable Rural Tourism in Himalayan Foothills pp 59–78 Cite as

Research Framework

- Suneel Kumar 2

- First Online: 20 September 2023

26 Accesses

This section presents the research design, provides a description and justification of the methodological approach and methods used, and details the research framework for the study. In addition, it presents the research objectives and highlights the research hypothesis; discusses about the research area, sampling techniques used, and the sample size drawn for the study; and presents the questionnaire used for collection of data and a detailed view of the statistical tools and techniques used in the study for the analysis purpose.

- Flexible strategies

- Sustainable development goals

- Judgmental sampling

- Snowball sampling

- Interpretive structural modeling

- MICMAC analysis

- Continuity-change matrix

- HML-VDB analysis

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Atsushi, I. 2011. Effects of improving infrastructure quality on business costs: Evidence from firm-level data in eastern europe and central asia. The Developing Economies 49 (02): 121–147.

Article Google Scholar

Bhardwaj, P. 2019. Types of sampling in research. Journal of the Practice of Cardiovascular Science 5: 157–163.

Boynton, P.M., and T. Greenhalgh. 2004. Selecting, designing, and developing your questionnaire. BMJ 328 (7451): 1312–1315. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.328.7451.1312 .

Butler, R.W. 1980. The concept of a tourist area cycle of evolution: Implications for management of resources. Canadian Geographer/ Le Géographe Canadien 24 (01): 5–12.

Cho, J.Y., and E.H. Lee. 2014. Reducing confusion about grounded theory and qualitative content analysis: Similarities and differences. The Qualitative Report 19 (32): 1–20.

Google Scholar

Creswell, J.W. 2013. Qualitative inquiry research design, choosing among five approaches . Los Angeles: Sage.

Cuthill, M. 2002. Exploratory research: Citizen participation, local government, and sustainable development in Australia. Sustainable Development 10: 79–89.

Elfil, M., and A. Negida. 2017. Sampling methods in clinical research; an educational review. Emergency(Tehran) 5 (01): 52.

Groenewald, T. 2004. A phenomenological research design illustrated. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 3 (01): 42–51.

Grinnell Jr, R. M., & Unrau, Y. A. 2010. Social work research and evaluation: Foundations of evidence-based practice . Oxford University Press.

Hall, J. 2008. Cross-sectional survey design. In Encyclopedia of survey research methods , ed. P.J. Lavrakas, 173–174. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Huberman, A.M., and M.B. Miles. 1994. Qualitative data analysis: An expanded . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Kerlinger, F. N. 1986. Foundations of Behavioural Research (3rd edn). New York: CBS College Publishing.

Kaurav, R.P.S., J. Kaur, and K. Singh. 2013. Rural tourism: Impact study—an integrated way of development of tourism for India. In Changing paradigms of rural management , ed. R.K. Miryala, 313–320. Hyderabad: Zenon Academic Publishing.

Kulkarni, Prashant B., K. Ravi, and S.B. Patil. 2018. Interpretive structural modeling (ISM) for implementation of green supply chain management in construction sector within Maharashtra. International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) : 2460–2472.

Kumar, Suneel, Navneet Guleria Shekhar, and N. Guleria. 2019. Understanding dynamics of niche tourism consumption through interpretive structure modeling. Saaransh RKG Journal of Management 11 (01): 40–48.

Mandal, A., and S.G. Deshmukh. 1994. Vendor selection using Interpretive Structural Modelling (ISM). International Journal of Operations & Production Management 14 (06): 52–59.

Masoodi, M. 2017. A comparative analysis of two qualitative methods: deciding between grounded theory and phenomenology for your research. Vocational Training: Research and Realities 28 (01): 23–40.

de Mello, A.M., and M. Pedroso. 2018. Applied research articles: Narrowing the gap between research and organizations. Revista de Gestão 25 (04): 338–339.

Mohajan, H.K. 2018. Qualitative research methodology in social sciences and related subjects. Journal of Economic Development, Environment and People 7 (01): 23–48.

Nordin, S. 2005. Tourism of tomorrow: Travel trends and forces of change . European Tourism Research Institute.

Praveenkumar, S. 2015. Tourism marketing and consumer behaviour. Research Journal of Social Science and Management 4 (12): 73–81.

Raj, T., Shankar, R., & Suhaib, M. 2008. An ISM approach for modelling the enablers of flexible manufacturing system: The case for India. International Journal of Production Research 46 (24): 6883–6912.

Rizvi, N.U., S. Kashiramka, S. Singh, and Sushil. 2019. A hierarchical model of the determinants of non-performing assets in banks: An ISM and MICMAC approach. Applied Economics : 1–21.

Saini, V. 2015. Skill development in India: Need, challenges and ways forward. Abhinav National Monthly Refereed Journal of Research in Arts & Education 4 (04): 1–9.

Setia, M.S. 2016. Methodology series module 5: sampling strategies. Indian Journal of Dermatology 61 (05): 505–509.

Shekhar, Suneel, and K. Attri. 2017. Incredible India: SWOT analysis of tourism sector. In Development aspects in tourism and hospitality sector , 175–189. New Delhi: Bharti Publications.

Syed Muhammad, S. K. 2016. Basic guidelines for research: An introductory approach or all disciplines , 1st ed. Bangladesh: Book Zone Publication.

Taherdoost, H. 2016. Sampling methods in research methodology; how to choose a sampling technique for research. International Journal of Academic Research in Management 5 (02): 18–27.

Weiermair, K., M. Peters, and M. Schuckert. 2015. Destination development and the tourist life-cycle: Implications for entrepreneurship in alpine tourism. Tourism Recreation Research 32: 83–93.

Link to SDGs

THE 17 GOALS | Sustainable Development (un.org)

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Shaheed Bhagat Singh College, University of Delhi, New Delhi, India

Suneel Kumar

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Kumar, S. (2023). Research Framework. In: Sustainable Rural Tourism in Himalayan Foothills. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-40098-8_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-40098-8_3

Published : 20 September 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-40097-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-40098-8

eBook Packages : Earth and Environmental Science Earth and Environmental Science (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

Theoretical Framework Example for a Thesis or Dissertation

Published on October 14, 2015 by Sarah Vinz . Revised on July 18, 2023 by Tegan George.

Your theoretical framework defines the key concepts in your research, suggests relationships between them, and discusses relevant theories based on your literature review .

A strong theoretical framework gives your research direction. It allows you to convincingly interpret, explain, and generalize from your findings and show the relevance of your thesis or dissertation topic in your field.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Sample problem statement and research questions, sample theoretical framework, your theoretical framework, other interesting articles.

Your theoretical framework is based on:

- Your problem statement

- Your research questions

- Your literature review

A new boutique downtown is struggling with the fact that many of their online customers do not return to make subsequent purchases. This is a big issue for the otherwise fast-growing store.Management wants to increase customer loyalty. They believe that improved customer satisfaction will play a major role in achieving their goal of increased return customers.

To investigate this problem, you have zeroed in on the following problem statement, objective, and research questions:

- Problem : Many online customers do not return to make subsequent purchases.

- Objective : To increase the quantity of return customers.

- Research question : How can the satisfaction of the boutique’s online customers be improved in order to increase the quantity of return customers?

The concepts of “customer loyalty” and “customer satisfaction” are clearly central to this study, along with their relationship to the likelihood that a customer will return. Your theoretical framework should define these concepts and discuss theories about the relationship between these variables.

Some sub-questions could include:

- What is the relationship between customer loyalty and customer satisfaction?

- How satisfied and loyal are the boutique’s online customers currently?

- What factors affect the satisfaction and loyalty of the boutique’s online customers?

As the concepts of “loyalty” and “customer satisfaction” play a major role in the investigation and will later be measured, they are essential concepts to define within your theoretical framework .

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Below is a simplified example showing how you can describe and compare theories in your thesis or dissertation . In this example, we focus on the concept of customer satisfaction introduced above.

Customer satisfaction

Thomassen (2003, p. 69) defines customer satisfaction as “the perception of the customer as a result of consciously or unconsciously comparing their experiences with their expectations.” Kotler & Keller (2008, p. 80) build on this definition, stating that customer satisfaction is determined by “the degree to which someone is happy or disappointed with the observed performance of a product in relation to his or her expectations.”

Performance that is below expectations leads to a dissatisfied customer, while performance that satisfies expectations produces satisfied customers (Kotler & Keller, 2003, p. 80).

The definition of Zeithaml and Bitner (2003, p. 86) is slightly different from that of Thomassen. They posit that “satisfaction is the consumer fulfillment response. It is a judgement that a product or service feature, or the product of service itself, provides a pleasurable level of consumption-related fulfillment.” Zeithaml and Bitner’s emphasis is thus on obtaining a certain satisfaction in relation to purchasing.

Thomassen’s definition is the most relevant to the aims of this study, given the emphasis it places on unconscious perception. Although Zeithaml and Bitner, like Thomassen, say that customer satisfaction is a reaction to the experience gained, there is no distinction between conscious and unconscious comparisons in their definition.

The boutique claims in its mission statement that it wants to sell not only a product, but also a feeling. As a result, unconscious comparison will play an important role in the satisfaction of its customers. Thomassen’s definition is therefore more relevant.

Thomassen’s Customer Satisfaction Model

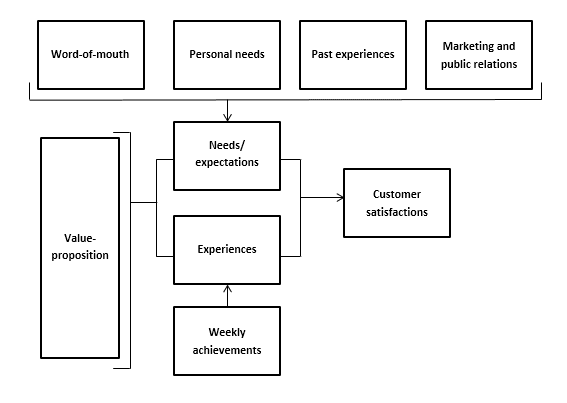

According to Thomassen, both the so-called “value proposition” and other influences have an impact on final customer satisfaction. In his satisfaction model (Fig. 1), Thomassen shows that word-of-mouth, personal needs, past experiences, and marketing and public relations determine customers’ needs and expectations.

These factors are compared to their experiences, with the interplay between expectations and experiences determining a customer’s satisfaction level. Thomassen’s model is important for this study as it allows us to determine both the extent to which the boutique’s customers are satisfied, as well as where improvements can be made.

Figure 1 Customer satisfaction creation

Of course, you could analyze the concepts more thoroughly and compare additional definitions to each other. You could also discuss the theories and ideas of key authors in greater detail and provide several models to illustrate different concepts.

If you want to know more about AI for academic writing, AI tools, or research bias, make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

Research bias

- Anchoring bias

- Halo effect

- The Baader–Meinhof phenomenon

- The placebo effect

- Nonresponse bias

- Deep learning

- Generative AI

- Machine learning

- Reinforcement learning

- Supervised vs. unsupervised learning

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Vinz, S. (2023, July 18). Theoretical Framework Example for a Thesis or Dissertation. Scribbr. Retrieved April 3, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/theoretical-framework-example/

Is this article helpful?

Sarah's academic background includes a Master of Arts in English, a Master of International Affairs degree, and a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science. She loves the challenge of finding the perfect formulation or wording and derives much satisfaction from helping students take their academic writing up a notch.

Other students also liked

What is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, how to write a literature review | guide, examples, & templates, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, what is your plagiarism score.

National Institute of Standards and Technology

Nist technical series publication.

NIST SP 1500-18r2

NIST Research Data Framework (RDaF)

Version 2.0

Robert J. Hanisch

Office of Data and Informatics

Material Measurement Laboratory

Debra L. Kaiser

Andrea Medina-Smith

Bonnie C. Carroll

Eva M. Campo

Campostella Research and Consulting

Alexandria, VA

This publication is available free of charge

https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.1500-18r2

February 2024

The NIST Research Data Framework (RDaF) is a multifaceted and customizable tool that aims to help shape the future of open data access and research data management (RDM). The RDaF will allow organizations and individual researchers to develop their own RDM strategy. Though NIST is leading the RDaF, most of the content in the current version 2.0, which supersedes preliminary V1.0 and interim V1.5, was obtained via engagement with national and international leaders in the research data community. NIST held a series of three plenary and 15 stakeholder workshops from October 2021 to September 2023. Workshop attendees represented many stakeholder sectors: US government agencies, national laboratories, academia, industry, non-profit organizations, publishers, professional societies, trade organizations, and funders (public and private), including international organizations. The audience for the RDaF is the entire research data community in all disciplines—the biological, chemical, medical, social, and physical sciences and the humanities. The RDaF is applicable from the organization to the project level and encompasses a wide array of job roles involving RDM, from executives and Chief Data Officers to publishers, funders, and researchers. The RDaF is a map of the research data space that uses a lifecycle approach with six stages to organize key information concerning RDM and research data dissemination. Through a community-driven and in-depth process, NIST identified and defined specific, high-priority topics and subtopics for each lifecycle stage. The topics and subtopics are programmatic and operational activities, concepts, and other important factors relevant to RDM which form the foundation of the framework. This foundation enables organizations and individual researchers to use the RDaF for self-assessment of their RDM status. Each subtopic has several informative references —resources such as guidelines, standards, and policies—to help a user understand or implement that subtopic. As such, the RDaF may be considered a “best practices” document. Fourteen overarching themes —topic areas identified as pervasive throughout the framework—illustrate the connections among the six lifecycle stages. Finally, the RDaF includes eight sample profiles for common job functions or roles. Each profile contains topics and subtopics an individual in the given role needs to consider in fulfilling their RDM responsibilities. Individual researchers and organizations involved in the research data lifecycle will be able to tailor these sample profiles or generate entirely new profiles for their specific job function. The methodologies used to generate the content of this publication, RDaF V2.0, are described in detail. An interactive web application has been developed and released that provides an interface for all the components of the RDaF mentioned above and replicates this document. The web application is easy and intuitive to navigate and provides new functionality enabled by the interactive environment.

Publications in the SP1500 subseries are intended to capture external perspectives related to NIST standards, measurement, and testing-related efforts. These external perspectives can come from industry, academia, government, and others. These reports are intended to document external perspectives and do not represent official NIST positions. The opinions, recommendations, findings, and conclusions in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of NIST or the United States Government.

Certain commercial entities, equipment, or materials may be identified in this document to describe an experimental procedure or concept adequately. Such identification is not intended to imply recommendation or endorsement by NIST, nor is it intended to imply that the entities, materials, or equipment are necessarily the best available for the purpose.

NIST Technical Series Policies

Copyright, Fair Use, and Licensing Statements

NIST Technical Series Publication Identifier Syntax

Publication History

Approved by the NIST Editorial Review Board on 2023-12-21

Supersedes NIST Series 1500-18 version 1.5 (May 2023) https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.1500-18r1 ; NIST Series 1500-18 (February 2021) https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.1500-18

How to Cite this NIST Technical Series Publication

Hanisch, RJ; Kaiser, D; Yuan, A; Medina-Smith, A; Carroll, B; Campo, E (2023) NIST Research Data Framework (RDaF) Version 2.0. (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD), NIST Special Publication (SP) 1500-18r2. https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.1500-18r2

NIST Author ORCID IDs

Robert Hanisch: 0000-0002-6853-4602

Debra Kaiser: 0000-0001-5114-7588

Alda Yuan: 0000-0001-9619-306X

Andrea Medina-Smith: 0000-0002-1217-701X

Bonnie Carroll: 0000-0001-8924-1000

Eva Campo: 0000-0002-9808-4112

Contact Information

Version 2.0 of the NIST Research Data Framework builds on the Preliminary version 1.0 released in February 2021 and on the interim version 1.5 released in May 2023, and incorporates input from many stakeholders. Version 2.0 has more than twice as many topics and subtopics as V1.0 and includes new sections. The major new sections are overarching themes : terms prevalent in multiple lifecycle stages, and profiles , which provide a list of the most relevant topics and subtopics for a given job function or role within the research data management ecosystem. A Request for Information (RFI) based on interim V1.5 was posted in the Federal Register in early June 2023. All comments received in response to this RFI were considered and the RDaF V1.5 was revised as appropriate. A draft of this modified version was presented at a stakeholder workshop held in September 2023.

Author Contributions

Robert Hanisch : Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing- review and editing; Debra Kaiser : Formal Analysis, Methodology, Writing- review and editing; Alda Yuan : Formal Analysis, Methodology, Project Administration, Writing- original draft, Writing- review and editing, Visualization; Andrea Medina-Smith : Data Curation, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Software, Writing- review and editing; Bonnie Carroll : Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing- review and editing; Eva M. Campo : Data Curation, Visualization, Writing- review and editing.

Acknowledgments

The completeness, relevance, and success of the NIST RDaF is wholly dependent on the input and participation of the broad research data community. NIST is grateful to all the workshop participants and others who have provided input to this effort. First and foremost, NIST thanks the members of the RDaF Steering Committee, past and present, who have given sound advice and shared their invaluable expertise since the inception of the RDaF in December 2019: Laura Biven, Cate Brinson, Bonnie Carroll (Chair), Mercè Crosas, Anita de Waard, Chris Erdmann, Joshua Greenberg, Martin Halbert, Hilary Hanahoe, Heather Joseph, Mark Leggott, Barend Mons, Sarah Nusser, Beth Plale, and Carly Strasser.

The RDaF team is also grateful to Susan Makar from the NIST Research Library for assistance with the informative references and to Angela Lee for development of the V2.0 interactive web application. Thanks to Eric Lin and James St. Pierre for their critical advice.

Thanks to the former members of the RDaF team including Breeze Dorsey, Laura Espinal, and Tamae Wong. Thanks as well to Campostella Research and Consulting for providing administrative support for the project and technical support for the natural language processing work. Our appreciation also goes to the NIST Material Measurement Laboratory (MML) leadership for their support and to all participants of the various workshops held to solicit community feedback, particularly those individuals who volunteered to serve as discussion leaders.

And finally, thanks to all involved with the NIST Cybersecurity Framework, which provided an initial model for development of the RDaF.

Keywords Research data, research data ecosystem, research data framework, research data lifecycle, research data management, research data dissemination, use, and reuse, research data governance, research data sharing, research data stewardship, open data.

1 Introduction

NIST’s Research Data Framework (RDaF) is designed to help shape the future of research data management (RDM) and open data access. Research data are defined here as “the recorded factual material commonly accepted in the scientific community as necessary to validate research findings.”[ 1 ] The motivation for the RDaF as articulated in the first RDaF publication V1.0 [ 2 ]—that the research data ecosystem is complicated and requires a comprehensive approach to assist organizations and individuals in attaining their RDM goals—has not changed since the project was initiated in 2019. Developed through active involvement and input from national and international leaders in the research data community, the RDaF provides a customizable strategy for the management of research data. The audience for the RDaF is the entire research data community, including all organizations and individuals engaged in any activities concerned with RDM, from Chief Data Officers and researchers to publishers and funders. The RDaF builds upon previous data-focused frameworks but is distinct through its emphasis on research data, the community-driven nature of its formulation, and its broad applicability to all disciplines, including the social sciences and humanities.

The RDaF is a map of the research data space that uses a lifecycle approach with six high-level lifecycle stages to organize key information concerning RDM and research data dissemination. Through a community-driven and in-depth process, stakeholders identified topics and subtopics —programmatic and operational activities, concepts, and other important factors relevant to RDM. These topics and subtopics, identified via stakeholder input, are nested under the six stages of the research data lifecycle. A partial example of this structure is illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1 — Partial organizational structure of the framework foundation

The components of the RDaF foundation shown in Fig. 1 —lifecycle stages and their associated topics and subtopics—are defined in this document. In addition, most subtopics have several informative references —resources such as guidelines, standards, and policies—that assist stakeholders in addressing that subtopic. Specific standards and protocols provided in the text or informative references may only be relevant for certain RDM situations. A link to the complete list of informative references is given in Appendix A .

The RDaF is not prescriptive; it does not instruct stakeholders to take any specific approach or action. Rather, the RDaF provides stakeholders with a structure for understanding the various components of RDM and for selecting components relevant to their RDM goals. The RDaF also includes sample profiles , which contain topics and subtopics an individual in a job role or function are encouraged consider in fulfilling their RDM responsibilities. Researchers and organizations involved in the research data lifecycle will be able to tailor these profiles using a supplementary document and online tools that will be available on the RDaF homepage . Entirely new profiles may be generated using a blank on-line template available in this supplementary document. Other uses of the RDaF include self-assessment and improvement of RDM infrastructure and practices for both organizations and individuals.

The RDaF was designed to be applicable to all stakeholders involved in research data. An organization seeking to review their data management policies may use the subtopics to create their own metrics for RDM assessment. Researchers who wish to ensure that their data are open access may use the framework to create a “checklist” of RDM considerations and tasks. A research project leader seeking guidance on how to assign data management roles may use the eight sample profiles as a starting point to create customized lists of responsibilities for individual researchers in their lab.

Since the first publication of the RDaF in 2021 (V1.0 [ 2 ]), NIST has expanded and enriched the framework through extensive engagement with stakeholders in the research data community. This publication, RDaF V2.0, includes updates to V1.0 and new features. Definitions and informative references for each subtopic have been added to improve the usability and applicability of the RDaF. In addition to profiles discussed in the previous paragraph, this document includes overarching themes that appear across multiple lifecycle stages and a list of many of the key organizations in the RDM space (see Appendix B ). The methodology used to generate the content of V2.0 is described in detail in the following section.

Note that the terms “data,” “datasets,” “data assets,” “digital objects,” and “digital data objects” are used throughout the framework depending on the context. Data is the most general and frequently used term. Dataset means a specific collection of data having related content. A data asset is “any entity that is comprised of data which may be a system or application output file, database, document, and web page.”[ 3 ] Digital objects and digital data objects typically have a structure such that they can be understood without the need for separate documentation. In addition, the terms “organization” and “institution” used throughout the framework are synonymous and the terms "RDaF team" and "team" refer to the authors of this publication. Finally, a list that spells out the full names of acronyms and initialisms used throughout this document is provided in Appendix C .

2 Methodology

This section describes the approaches used to develop RDaF V2.0, including brief descriptions of activities since the inception of the project in 2019. Throughout the lifetime of the RDaF project, the Steering Committee members noted previously in the Acknowledgements section were consulted, took leadership roles as discussion leaders at workshops, and provided valuable input and feedback on all aspects of the project.

2.1 Framework Development Through Stakeholder Input

The RDaF is driven by the research data stakeholder community, which can use the framework for multiple purposes such as identifying best practices for research data management (RDM) and dissemination and changing the research data culture in an organization. To ensure that the RDaF is a consensus document, NIST held stakeholder engagement workshops as the primary mechanism to gather input on the framework. The workshops have taken place in three phases, each resulting in further examination and refinement of the framework.

2.1.1 Phase 1: Plenary Scoping Workshop and Publication of the Preliminary RDaF V1.0

In the plenary scoping workshop held in December 2019, a group of about 50 distinguished research data experts selected a research data lifecycle approach as the organizing principle of the RDaF. The RDaF team subsequently selected six lifecycle stages—Envision, Plan, Generate/Acquire, Process/Analyze, Share/Use/Reuse, and Preserve/Discard—from a larger pool of stages suggested by workshop break-out groups. Feedback from this workshop contributed to the publication of the RDaF V1.0, which provides a structured and customizable approach to developing a strategy for the management of research data. The framework core (subsequently renamed foundation in V2.0) consisting of these six lifecycle stages and their associated topics and subtopics is the main result of that publication.

2.1.2 Phase 2: Opening Plenary Workshops

The second phase of the RDaF development began with two virtual plenary workshops held in late 2021. Each workshop had approximately 70 attendees and focused on two cohorts. The university cohort (UC) workshop, co-hosted by the Association of American Universities, the Association of Public Land-grant Universities, and the Association of Research Libraries, was a horizontal cut across various stakeholder roles in universities (e.g., vice presidents of research, deans, professors, and librarians), publishing organizations, data-based trade organizations, and professional societies. In contrast, the materials cohort (MC) workshop, held in cooperation with the Materials Research Data Alliance , was a vertical cut across stakeholder organizations engaged in materials science, including academia, government agencies, industry, publishers, and professional societies.

Prior to the workshops, the attendees selected, or were assigned to, one of six breakout sessions, each focused on a stage in the RDaF research data lifecycle. A NIST coordinator sent the attendees a link to the RDaF publication V1.0, a list of the participants, and definitions of the topics for that session’s lifecycle stage. The agenda for the two workshops included an overview talk by Robert Hanisch on the RDaF, a one-hour breakout session, and a plenary session with summaries presented by an attendee of each breakout and with closing remarks. During the breakout sessions, a discussion leader, recruited by the RDaF team, solicited input from the 10 to 12 participants on the following questions:

What are the most important (two or three) topics and the least important one?

Are there any missing topics?

Should any topics be modified or moved to another lifecycle stage?

The identical questions were posed regarding the subtopics for each topic. Attendee input was captured as notes taken by the session rapporteur and the NIST coordinator and an audio recording. After the two opening plenary workshops, the RDaF team revised the topics and subtopics for the lifecycle stages based on input from the workshops. All six of the lifecycle stages were then reviewed side-by-side for consistency and completeness.

The collective review revealed 14 overarching themes which appeared in multiple lifecycle stages. These themes include metadata and provenance, data quality, the FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) data principles, software tools, and cost implications. Section 4 of this document will address all overarching themes in detail.

2.1.3 Phase 3: Stakeholder Workshops

The next step in obtaining community input involved a series of two-hour stakeholder workshops focused on specific roles, equivalent to job functions or position titles. To secure a broad range of feedback, the RDaF team compiled a list of more than 200 invitees, including attendees of previous workshops and additional experts. These invitees were assigned to one of the following 15 roles:

Academic mid-level executive/head of research

Budget/cost expert

Data/IT leader

Data/research governance leader

Institute/center/program director

Open data expert

Professional society/trade organization leader

Provider of data tools/services/infrastructure

Senior executive

Unlike the first two RDaF workshops, these role-focused workshops were composed of smaller groups. The goal of these workshops was to develop profiles, i.e., lists of topics and subtopics important for individuals in a specific role with respect to RDM. Though the target size of these two-hour workshops was 10 to12 participants, the actual number ranged from four to 14. For each workshop, the RDaF team identified and invited an expert to serve as the discussion leader. Two members of the team were assigned to each workshop: a presenter and a rapporteur.

During the workshops, after a brief presentation covering the purpose and structure of the RDaF, participants selected the lifecycle stages most relevant to their assigned role. For each lifecycle stage, participants reviewed the topics and subtopics, and discussed any that were missing, misplaced or unclear. Depending on the length of the discussion, each workshop covered two to four of the lifecycle stages. In addition to requesting input on the topics and subtopics, the NIST coordinators asked participants to consider which topics and subtopics had the greatest influence on their role and those over which they had the greatest influence.

2.2 Framework Revisions per Stakeholder Workshop Input

Most of the input from participants at the Stakeholder Workshops concerned the topics and subtopics, and this input was used to revise them.

2.2.1 Stakeholder Workshop Note Aggregation

After the Stakeholder Workshops, the RDaF team designed a common methodology for collecting and analyzing the feedback, using a template to record the input from each workshop. This template contained the following:

A column for topics and subtopics in a lifecycle stage that were missing, misplaced, or unclear

A column for topics and subtopics relevant to, or missing from, the profile for a role

A section on feedback that addressed the definition of the role

A section on “takeaways” regarding the framework as a whole

A section on proposed new overarching themes

To analyze the feedback from each stakeholder workshop, selected RDaF team members first reviewed the rapporteur’s notes to familiarize themselves with the discussion. Then these team members viewed the recording of the workshop, read through any written comments provided in the workshop chat, and noted every comment in the appropriate section of the template. After the first draft of the template notes was completed, the team members viewed the recording a second time, added any missing comments, and converted each comment and suggestion concerning a topic or subtopic into a potential change for review. Finally, the entire RDaF team considered each potential change and generated an updated interim V1.5 of the framework foundation.

2.2.2 Input for Profile Development

After updating the framework foundation based on the stakeholder feedback, the next step involved the generation of a sample profile for each role addressed by a workshop. As the feedback from the stakeholder workshops concerning profiles was limited and varied in form and specificity, more data were needed to develop these profiles.

The updated topics and subtopics were used to develop blank checklists of topics and subtopics for the lifecycle stages discussed at each of the 15 stakeholder workshops. The appropriate spreadsheet was sent to the participants of a given workshop with instructions to mark those topics and subtopics that were most relevant to the role addressed at that workshop. About 60 participants submitted out a spreadsheet with their responses for the workshop they attended.

The responses were analyzed for similarities and several roles were modified. For example, professors and researchers were grouped together to form one role as professors are typically involved in their groups’ research. After consideration of the participants’ responses, the RDaF team selected eight common job roles for the generation of sample profiles. These roles are AI expert, curator, budget/cost expert, data and IT expert, provider of data tools, publisher, research organization leader, and researcher.

For each sample profile, the RDaF team first calculated the percentage of responses that labeled a subtopic as relevant. When 50% or more of the respondents considered a subtopic to be relevant, it was presumptively deemed relevant for the sample profile. Next, the team considered all comments received with the profile responses as well as all the notes from the Stakeholder Workshop to further flesh out the sample profile. Lastly, the RDaF team consulted with experts in these roles to finalize the profiles.

2.2.3 Request for Information on Interim Version 1.5

Interim V1.5 of the RDaF was published in May 2023 [ 4 ]. This publication included the entire list of topics and subtopics for the six lifecycle stages, definitions, informative references for most of the subtopics, 14 overarching themes, and eight sample profiles.

The RDaF team developed a Request for Information (RFI) that was posted in the Federal Register on June 6, 2023, to communicate updates to the RDaF and receive additional feedback on V1.5. The public had 30 days after release of the RFI to comment on any aspect of the RDaF. The RDaF team reviewed and distilled the comments into almost 70 possible action items which were considered individually within the context of the intent of the framework. All comments received were considered in generating V2.0 of the framework.

2.3 Development of an Interactive Web Application

A web application has been developed and released that presents an interface to the RDaF components—lifecycle stages, topics, subtopics, definitions, informative references, overarching themes, and sample profiles—and thus replicates this RDaF V2.0 document in an interactive environment. In addition to providing an easy means of navigating through the various components and the relationships among them, the web application has new functionality such as the capability to link subtopics to their corresponding informative references and to direct a user to the original source of any reference.

The web application runs on a variety of platforms including Windows, MacOS, and Linux. Development of the software—database design, Entity Framework Core, web application framework, search strategies, and user interface—is the subject of a separate publication in preparation.

3 Framework Foundation – Lifecycle Stages, Topics, and Subtopics

The foundation of the RDaF consists of lifecycle stages, topics, and subtopics selected by the RDaF team using a vast amount of stakeholder input as described in Section 2 . The RDaF research data lifecycle graphic depicted in Fig. 2 is cyclical rather than linear and has six stages defined below. Each stage is interconnected to all other stages, i.e., a stage can lead into any other stage. An organization or individual may initially approach the lifecycle from any stage and subsequently address any other stage. It is likely that an organization or individual will be involved in all lifecycle stages simultaneously, though with different levels of intensity or capacity.

Envision – This lifecycle stage encompasses a review of the overall strategies and drivers of an organization’s research data program. In this lifecycle stage, choices and decisions are made that together chart a high-level course of action to achieve desired organizational goals, including how the research data program is incorporated into an organization’s data governance strategy.

Plan – This lifecycle stage encompasses the activities associated with preparing for data acquisition, selection of data formats and storage solutions, and anticipation of data sharing and dissemination strategies and policies, including how a research data program is incorporated into an organization’s data management plan.

Generate/Acquire – This lifecycle stage covers the generation of raw research data, both experimentally and computationally, within an organization or by an individual, and the collection or acquisition of research data produced outside of an organization.

Process/Analyze – This lifecycle stage concerns the actions performed on generated or externally acquired research data to yield processed research data, typically using software, from which observations and conclusions can be made.

Share/Use/Reuse – This lifecycle stage outlines how raw and processed research data are disseminated, used, and reused within an organization or by an individual and any constraints or encouragements to use/reuse such data. This stage also includes the dissemination, use, and reuse of raw and processed research data outside an organization.

Preserve/Discard – This lifecycle stage delineates the end-of-use and end-of-life provisions for research data by an organization or individual and includes records management, archiving, and safe disposal.

Fig. 2 — Research data framework lifecycle stages

Tables 1 - 6 presented below each cover one research data lifecycle stage and its associated topics and subtopics. The goal of the framework is to be comprehensive while remaining flexible. An organization or individual may find that not every topic and subtopic in a lifecycle stage is relevant to their work. The selection of subtopics to generate a profile for a job or function will be described in Section 5 .

Many lexicons are used in the research data management space. Though the RDaF does not intend to introduce an entirely new vocabulary, it is important to be precise with the use of key terms. For each topic and subtopic, the RDaF provides definitions to assist users in understanding what tasks and responsibilities are associated with that topic or subtopic. To derive these definitions, the RDaF team performed a search of common data lexicons such as CODATA’s Research Data Management Terminology and Techopedia [ 5 , 6 ]. Additionally, the team searched more broadly for common and research data management-specific definitions, including ones for the informative references that provide guidance in the implementation of the RDaF. Some definitions are general or commonly understood and as such have no references. The definitions were checked for consistency with stakeholder feedback. Individual researchers and organizations should keep in mind that these definitions are not prescriptive and consider their own context when determining whether the definitions provided are appropriate.

Table 1. Envision lifecycle stage

Table 2. Plan lifecycle stage

Table 3. Generate/Acquire lifecycle stage

Table 4. Process/Analyze lifecycle stage

Table 5. Share/Use/Reuse lifecycle stage

Table 6. Preserve/Discard lifecycle stage

4 Overarching Themes

The RDaF was refined from the preliminary V1.0 using input from the two opening plenary workshops and the 15 stakeholder workshops. During this refinement process, 14 themes that spanned the various lifecycle stages were identified. Rather than repeat these themes in each stage, they are listed here with a brief explanation of their meaning in the context of research data and research data management (RDM). Following the explanatory narrative, the specific lifecycle stages/topics/subtopics in which each theme appears are shown in tabular form.

In most cases, the overarching themes are supported by explicit references in the framework. In other cases, the themes are implicit. For example, the cost implications and sustainability theme touches on every topic or subtopic, although it is not called out in any lifecycle stage: there is a financial implication to every decision and action that will be considered by those working with research data in any capacity. Note that while these 14 themes emerge from the general definitions of the topics and subtopics, considering the scope of RDM from the perspective of a specific individual or organization, other themes may emerge. Such custom themes can serve as an additional organizing function for job roles, tasks, and other activities represented by the topics and subtopics in the framework.

Separate tables generated for each overarching theme document the topics and subtopics most closely associated to that theme (see Tables 7 - 20 below). There are also two graphics that provide summary information. Figure 3 is a Sankey diagram that provides a visualization of the relationship between each lifecycle stage and each overarching theme. Figure 4 is a matrix table that gives a high-level overview of the relationships between the overarching themes and the topics for each lifecycle stage. (Some of the overarching theme names in Figs. 3 and 4 have been truncated or abbreviated for visualization purposes.)

Fig. 3 — Sankey diagram of the relationships between lifecycle stages and overarching themes

Fig. 4 — Matrix diagram of topics and overarching themes

4.1 Community Engagement

Community engagement , typically broader for RDM practices and more focused for research data projects, is an intentional set of approaches for both listening to and communicating with stakeholders. Successful research, data management, and data curation come from strong engagement with the community of practice or discipline and the organization in which the research is conducted. Community engagement is present in all the RDaF lifecycle stages, although there is an emphasis on it within the Envision and Plan stages. Engagement with stakeholders early in the research process may result in stronger outcomes and uptake of new research. In the other four lifecycle stages, stakeholder engagement is essential for accomplishing the goals established at the beginning of a research project.

Table 7 lists the topics and subtopics that are most relevant to the overarching theme of community engagement.

Table 7. Community engagement (overarching theme)

4.2 Cost Implications and Sustainability

Cost implications and sustainability is a theme that touches every lifecycle stage and most stakeholders in the research ecosystem. From Chief Data Officers and provosts to researchers and grant administrators, cost is a constant focus of all individuals’ work in public and private organizations. Administrators and C-suite officers would typically focus their efforts on the stages of Envision and Plan, while researchers, particularly those with curation duties and service provision, have more impact on the cost implications in the Generate/Acquire, Process/Analyze, Share/Use/Reuse, and Preserve/Discard stages.

Sustainability in research and RDM means sustainable funding, staffing, and preservation models as applied to research data. It is imperative that sustainable plans affecting these three areas are assessed as the areas are developed and maintained to prevent institutions and users from losing access to valuable datasets.

Table 8 lists the topics and subtopics that are most relevant to the overarching theme of cost implications and sustainability.

Table 8. Cost implications and sustainability (overarching theme)

4.3 Culture

Culture is the basis for the entirety of a given organization’s success in managing research data and in nearly every other aspect of running a collective enterprise; culture is what gives an institution or organization its character and consistency over time. Cultures are firmly embedded and stem from both informal practices and formal written policies which can make them difficult to change. Culture shapes norms within an organization and creates glide paths towards ingrained values and behaviors as well as resistance to others. Specifically, culture dictates how research data are valued or supported in an institution.

Table 9 lists the topics and subtopics that are most relevant to the overarching theme of culture.

Table 9. Culture (overarching theme)

4.4 Curation and Stewardship

The processes and procedures to make research data shareable and reusable are typically referred to as curation and stewardship . Both curation and stewardship, and the job roles that are responsible for them, aim to collect, manage, preserve, and promote research data over their lifecycles. Curation is often performed by librarians and others outside of a laboratory or research group, while data stewards tend to work with a specific research group, lab, or department (i.e., a specific discipline) to ensure that they are embedded in research projects from the onset of the Plan lifecycle stage. Because curators tend to work outside of labs, they are typically engaged in research projects much later during the Share/Use/Reuse stage, which may introduce complications. The curation and stewardship theme implicitly touches each lifecycle stage.

Table 10 lists the topics and subtopics that are most relevant to the overarching theme of curation and stewardship.

Table 10. Curation and stewardship (overarching theme)

4.5 Data Quality

Data quality directly impacts a dataset’s fitness for purpose, usability, and reusability. All parties involved in every stage of a dataset’s lifecycle should be cognizant of data quality. The CODATA Research Data Management Terminology [ 5 ] definition of data quality includes the following attributes: accuracy, completeness, update status, relevance, consistency across data sources, reliability, appropriate presentation, and accessibility. Assessment of data quality is not a single process, but rather a series of actions that, over the lifetime of a dataset, collectively assure the greatest degree of quality.

Table 11 lists the topics and subtopics that are most relevant to the overarching theme of data quality.

Table 11. Data quality (overarching theme)

4.6 Data Standards

Data standards, both discipline-specific (e.g., Darwin Core [ 255 ] or NeXus [ 256 ]) and general (e.g., PREMIS [ 257 ] or schema.org [ 258 ]) are implemented by researchers to make their datasets both more FAIR and of higher quality. Researchers may use formal (e.g., ISO [ 259 ] or ANSI [ 260 ] standards) or de facto (e.g., DataCite [ 209 ]) standards for their research community. Use of data standards ensures consistency within a discipline and can reduce cost by decreasing the likelihood that data will have to be created again. Data standards are called out in every lifecycle stage except Envision.

Table 12 lists the topics and subtopics that are most relevant to the overarching theme of data standards.

Table 12. Data standards (overarching theme)

4.7 Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility

Diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (DEIA) is a broad theme covering important social and cultural aspects of a research enterprise. Efforts in DEIA center on growing the sense of belonging for everyone in every laboratory, research group, department, or institution. Research data practices are not immune to biases and historical disadvantages must often be addressed through intentional action. DEIA is important not just for members of underrepresented and marginalized groups, but for the integrity of the research process as a whole. More inclusive research tends to be more rigorous as it introduces different perspectives that enable more complete and broader interpretations of research data. Given the typical challenges associated with cultural changes within an institution, DEIA efforts must be embedded throughout the research data management lifecycle to maximize their effectiveness.

Table 13 lists the topics and subtopics that are most relevant to the overarching theme of diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility.

Table 13. Diversity, equity, inclusion, and accessibility (overarching theme)

4.8 Ethics, Trust, and the CARE Principles

Ethics, trust, and the CARE principles encompass the ethical generation, analysis, use, reuse, sharing, disposal, and preservation of data and are pillars of responsible research that are called out throughout the framework. The phrase “as open as possible, as closed as necessary” [ 261 ] comes to mind when working through the ethical implications of sharing data. While ethical choices are often made at the Share/Use/Reuse lifecycle stage, questions and concerns regarding the generation or collection of data are likely to be examined by an institutional or ethics review board and must be considered in the Plan stage. In the Preserve/Discard stage, it is essential to comply with preservation and disposition standards. While the subtopics in the framework are a starting point for understanding how ethics touches every aspect of the research data lifecycle, it is also important that a project be securely grounded in the practices of a given discipline; for example, the standards for historical research will differ from those for economic or healthcare research.

Trust is a factor across the Framework and is the basis for relationships between data producers and users, the funding agencies that support projects, and the institutions that host research. Specific populations will also have various ethical considerations, for example, the CARE Principles for Indigenous Data Governance are quickly becoming the standard for working with indigenous data worldwide [ 262 ].

Table 14 lists the topics and subtopics that are most relevant to the overarching theme of ethics, trust, and the CARE principles.

Table 14. Ethics, trust, and the CARE principles (overarching theme)

4.9 Legal Considerations

As much as technical capabilities structure the ways in which data can be gathered, created, published, and preserved, legal considerations constrain and channel the research data lifecycle. Laws form the background rules governing how data can be managed and shared. Legal considerations can be complex, as they are context-specific, hierarchical, and change over time. They typically vary by sector (e.g., healthcare, finance, education, and public government) and by geographic location (e.g., municipal, regional, national, and international), and are often subject to interpretation. Institutions that share data often use contracts and agreements that rely upon the legal system to order and enforce the terms therein. Laws sometimes restrict access, especially for categories of sensitive data such as personally identifiable information, certain types of healthcare information, and business identifiable information. However, laws can also enable data sharing by providing clear guidelines or directives to provide open data when it is in the public interest. Though legal considerations appear in most of the six lifecycle stages, meticulous planning and preparation make any constraints and compliance with policy requirements less onerous.

Table 15 lists the topics and subtopics that are most relevant to the overarching theme of legal considerations.

Table 15. Legal considerations (overarching theme)

4.10 Metadata and Provenance

Metadata and provenance comprise the information about a dataset that defines, describes, and links the dataset to other datasets and provides contextualization of the dataset [ 91 ]. Metadata are essential to the effective use, reuse, and preservation of research data over time. In the Envision and Plan stages, metadata support legal and regulatory compliance, and are a consideration in planning data outputs and resources.

The table below shows each topic/subtopic that mentions or covers metadata. While the final lifecycle stage (Preserve/Discard) does not explicitly relate to metadata, the existence of descriptive and other metadata is imperative to this stage. The robustness of metadata for a file or dataset determines the level of curation needed for preservation and use: richer metadata allows for better findability, interoperability, and reuse in support of the FAIR data principles, while less robust metadata make all these activities more difficult and time intensive. Poor-quality metadata can render an otherwise important dataset unusable when the creator of the dataset is no longer available.

Included in the metadata theme is provenance, the historical information concerning the data [ 41 ]. Understanding the provenance of a given dataset, including metadata on the experimental conditions used to generate the data, is essential for many disciplines. Without proper provenance documentation, it is difficult to assess the quality and reliability of the data and to publish them with correct metadata. Provenance can be used as a criterion for preservation.

Table 16 lists the topics and subtopics that are most relevant to the overarching theme of metadata and provenance.

Table 16. Metadata and provenance (overarching theme)

4.11 Reproducibility and the FAIR Data Principles

Touching many of the lifecycle stages are reproducibility and the FAIR data principles , which are findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability. Reproducible research yields data that can be replicated by the author or other researchers using only information provided in the original work [ 84 ]. Standards for reproducibility differ by research discipline, but typically the metadata and other contextual information needed for reproducibility are similar to those described by the FAIR data principles [ 33 ]. These community-based principles have come to define, for many disciplines, the state to which a published dataset should aspire. By keeping the principles of findability, accessibility, interoperability, and reusability in mind while planning a project or when data are collected, the data will be ready for broader reuse when they are publicly released. Extensions of the FAIR data principles also exist, such as FAIRER, which adds Ethical and Revisable to the base principles [ 263 ].

Table 17 lists the topics and subtopics that are most relevant to the overarching theme of reproducibility and the FAIR data principles.

Table 17. Reproducibility and the FAIR data principles (overarching theme)

4.12 Security and Privacy

Digital data are designed to be easily shared, copied, and transformed, but their mobility can make privacy and security difficult to ensure. Security and privacy issues are fundamentally about trust, both in the institutions and systems that facilitate collection, storage, and transfer of data, as well as the individuals within those institutions. Proper protocols, rationally based on the need to protect vulnerable populations or sensitive information, or stemming from common understandings of security needs, promote trust, which can enable greater data mobility. In the European Union, organizations that collect, store, or hold personal data must comply with the General Data Protection Regulation. [ 264 ] The U.S. does not have such a universal regulation, though various federal laws govern different sectors and types of data, and some states have their own additional regulations. Security and privacy issues arise in the Envision and Plan lifecycle stages, with the results folded into the day-to-day procedures for handling and accessing data and appear again in the Share/Use/Reuse lifecycle stage.

Table 18 lists the topics and subtopics that are most relevant to the overarching theme of security and privacy.

Table 18. Security and privacy (overarching theme)

4.13 Software Tools

Regarding research data, software tools are programs or utilities for developing applications and analyzing/processing or searching for data. Additionally, software tools are used to generate data from computational and experimental methods, throughout the publication process. An exhaustive list of tools would be ever-changing; more important than a list of tools used in every discipline is the understanding that the tools used during all lifecycle stages can influence other stages.

Table 19 lists the topics and subtopics that are most relevant to the overarching theme of software tools.

Table 19. Software tools (overarching theme)

4.14 Training, Education, and Workforce Development

Training, education, and workforce development are critical for ensuring that any given organization or individual involved in the research data management process has the necessary skills for RDM. Investment into workforce development is especially important in an area where best practices are still developing. On-the-job training not only helps to promote the standardization that is important in RDM but can also promote equity by ensuring that everyone has access to the most innovative practices.

Table 20 lists the topics and subtopics that are most relevant to the overarching theme of training, education, and workforce development.

Table 20. Training, education, and workforce development (overarching theme)

5 Profiles

Profiles specify those topics and subtopics in the RDaF lifecycle stages that are most relevant for a particular job role or research data management (RDM) function in an organization. The framework contains a comprehensive list of the tasks and issues that may arise with respect to research data activities and RDM. Most organizations or individuals will not find every subtopic to be relevant. As described below, NIST is developing a tool that allows individuals and organizations to customize a profile (i.e., select relevant subtopics from the full list of subtopics) for their specific needs or responsibilities.

The RDaF team generated sample profiles for eight common RDM job roles or functions. These profiles described below are intended to serve as samples and guides. Users may either modify a sample profile as a starting point for their own profile or build an entirely new profile by selecting relevant subtopics. The subtopics relevant to the eight sample profiles are presented in Table 21 . A straightforward tool to generate a customized profile—by modifying one of the sample profiles or by creating an entirely new profile—is described in Appendix D . The tool is an editable Excel file that contains all the information in Table 21 and a blank template of all the subtopics. Profiles may also be used to conduct self-assessments of RDM and identify tasks and issues that may need attention. Results of such self-assessments can subsequently be communicated within an organization or between organizations.

AI expert – This profile addresses the growing and evolving field of artificial intelligence. Experts in AI and machine learning often deal with large and incomplete datasets and may not be the originators of the data, making it difficult, e.g., to assess data and metadata quality.

Budget/cost expert – This profile is relevant to those individuals whose job responsibilities encompass budgetary and financial issues, such as securing funding, distributing funds and tracking spending within an organization. Budgetary issues underlie nearly every subtopic; this profile focuses on those subtopics that drive RDM costs.

Curator – This profile is pertinent to individuals who curate data in general, such as data librarians, and to individuals who curate data only for a specific research project. Curators collect, organize, clean, annotate, and transform data, which are critical tasks for data preservation, use, and reuse.

Data/IT leader – This profile is relevant to those individuals who establish priorities for RDM at an organizational or disciplinary level and who engage in strategic planning and establishing RDM infrastructure requirements.

Provider of data tools – This profile is germane to those individuals who create and provide tools that enable data to be collected, analyzed, stored, and shared such as hardware providers and programmers.

Publisher – This profile is pertinent to those individuals who publish articles in scientific journals and datasets in various dissemination modes These individuals and their organizations are concerned with data access, storage, preservation, and evaluation of data quality in publishing decisions.

Research organization leader – This profile is relevant to those individuals who establish policies, procedures, and processes for managing research data across an organization.

Researcher – This profile is germane to those individuals who conduct scholarly studies in all disciplines, including the social sciences and humanities, to produce new data used to, e.g., increase knowledge, validate hypotheses, and facilitate decision-making.

Table 21. Sample profiles

6 Conclusions and Ongoing Work

Version 2.0 of the NIST RDaF has been developed through extensive stakeholder engagement via a total of 17 workshops. Carefully crafted methodologies were used in the development process, which took place over nearly two years. The RDaF is based on a lifecycle model with six stages, each having a comprehensive list of defined topics and subtopics, as well as informative references for most of the subtopics. Version 2.0 contains full descriptions of 14 overarching themes and eight sample profiles detailing the relevant subtopics for eight common job roles/functions in research data management (RDM) and in conduct of research data projects. V2.0 also contains a list of many research data management organizations, with a link to the homepage for each organization. In addition to these features and resources, a tool has been produced that enables the creation of customized profiles. Finally, a web application has been developed and released that presents an interface to all content in this RDaF V2.0 document in an interactive environment and provides new functionality such as linkages of subtopics to corresponding informative references. The link to this web application is available on the RDaF homepage . The paragraphs below describe ongoing work in various areas.

The RDaF V2.0 can be tailored and customized to fit the needs of a variety of data management professionals and organizations. The content of the RDaF is already being implemented and used in various ways. Organizations have used the topics and subtopics in V1.0 to create “scorecards” of subtopics that indicate the current state of their RDM and are using V2.0 as a guide to create implementation plans for improving RDM and for creating profiles. The RDaF could potentially be used as a basis for a data management education curriculum. NIST welcomes and encourages additional creative uses of the RDaF by the community.

The research data ecosystem is evolving rapidly and NIST intends to release updates of the RDaF on a regular basis (subject to availability of resources). Additionally, NIST will assist the research data community, including organizations and individuals engaged in or interested in using the framework, to assess and improve their RDM. NIST will also seek partnerships with organizations having similar aspirations, such as the Australian Research Data Commons, who recently released their “Research Data Management Framework for Institutions”[ 262 ] and the Research Data Alliance’s new working group, the “RDA-OfR Mapping the Landscape of Digital Research Tools [ 266 ].” Finally, NIST is following the development of frameworks in other areas, such as the Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction [ 267 ]. NIST encourages organizations and individuals seeking assistance in using the RDaF or considering the development of value-added tools based on the RDaF to contact the team at [email protected] .

Given the complexity of the framework, the RDaF team is working on various tools to improve accessibility and applicability of the framework. The RDaF V2.0 interactive web application described in section 2.3 has an intuitive design such that users can easily navigate all components in the V2.0 document and view relationships among these components. New features of this web application such as graphical navigation, a user feedback form, and a guided profile-maker are under development.

Interactive, web-based knowledge graphs are being developed to visually demonstrate the interconnected nature of the many subjects and tasks in RDM [ 268 ]. The knowledge graphs will allow exploration of the relationships between, e.g., topics, subtopics, and job functions (profiles) within the research data ecosystem. Such interactive knowledge graphs enable individuals and organizations to approach RDM from a variety of perspectives and starting points. A user will be able to select any component of the framework, determine the other components to which the starting component is linked, and navigate through the diagram in an intuitive manner. For example, a researcher interested in metadata may start at one subtopic, then move to the overarching themes related to that subtopic. Next, that individual may review the sample researcher profile to determine other subtopics associated with metadata. Parsing through these subtopics, the researcher may encounter, for example, the data privacy subtopic, for which more knowledge is desired. To obtain this knowledge, the researcher then navigates to the informative references for that subtopic.

Due to the complex nature of RDM, the RDaF was designed to be comprehensive and broadly applicable. As a multifaceted tool, it can be used to address various aspects of RDM for organizations and individuals, e.g., assessment of the state of RDM using the RDaF lifecycle stages/topics/subtopics, development of strategies to improve RDM infrastructure, policies, and practices, and identification of RDM tasks and responsibilities for specific job roles or functions. Organizations and individuals seeking to use the RDaF for these and other purposes may need assistance. To this end, NIST intends to develop and publish a best practice guide for various use scenarios in collaboration with different stakeholder groups. Such a guide will focus on use of the RDaF for general topics, such as: assessment of existing RDM policies and practices; determination of goals for RDM; creation of step-by-step plans for reaching RDM goals; generation of curricula for continuing education and other training materials; and creation of job descriptions with individualized workplans.

The various workshops held to further develop the RDaF resulted in many transcripts and notes. The methodology section 2 described a manual, human-driven method of incorporating that feedback to generate V2.0. As a supplement and an experimental exercise, the RDaF team is also exploring natural language processing as a method to extract insight and draw conclusions via machine learning. These findings will be compared with the results of the manual process and may be incorporated in future versions of the RDaF.

[1] Office of the Federal Register NA and RA (2014) 2 CFR § 200.315 - Intangible property. govinfo.gov . Available at https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/CFR-2014-title2-vol1/CFR-2014-title2-vol1-sec200-315

[2] Hanisch RJ,, Kaiser DL, Carroll BC, (2021) Research Data Framework (RDaF) :: motivation, development, and a preliminary framework core . ( National Institute of Standards and Technology (U.S.), Gaithersburg, MD ), NIST SP 1500-18 . https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.1500-18

[3] Data Asset NIST Computer Security Resource Center Glossary . Available at https://csrc.nist.gov/glossary/term/data_asset

[4] Hanisch RJ, Kaiser DL, Yuan A, Medina-Smith A, Carroll BC, Campo EM, (2023) NIST Research Data Framework (RDaF): version 1.5. (National Institute of Standards and Technology (U.S.), Gaithersburg, MD), NIST SP 1500-18r1. https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.SP.1500-18r1

[5] Research Data Management Terminology CODATA, The Committee on Data for Science and Technology . Available at https://codata.org/initiatives/data-science-and-stewardship/rdm-terminology-wg/rdm-terminology/

[6] Techopedia: Educating IT Professionals To Make Smarter Decisions - Techopedia Available at https://www.techopedia.com/

[7] What is the difference between mission, vision and values statements? (2023) SHRM . Available at https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/tools-and-samples/hr-qa/pages/mission-vision-values-statements.aspx

[8] Data policy CODATA Research Data Management Terminology . Available at https://codata.org/rdm-terminology/data-policy/

[9] Data governance CODATA Research Data Management Terminology . Available at https://codata.org/rdm-terminology/data-governance/

[10] National Institute of Standards and Technology (2018) Framework for Improving Critical Infrastructure Cybersecurity, Version 1.1. (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Gaithersburg, MD), NIST CSWP 04162018. Available at https://doi.org/10.6028/NIST.CSWP.04162018

[11] Data management CODATA Research Data Management Terminology . Available at https://codata.org/rdm-terminology/data-management/

[12] What are organizational values? Workplace from Meta . Available at https://www.workplace.com/blog/organizational-values

[13] Verlinden N, (2021) Organizational Values: Definition, Purpose & Lots of Examples . AIHR . Available at https://www.aihr.com/blog/organizational-values/

[14] Briggs LL, (2011) Q&A: Solid Value Proposition a Key to MDM Success . Transforming Data with Intelligence . Available at https://tdwi.org/articles/2011/02/16/value-proposition-mdm-success.aspx

[15] NOAA Administrative Order 212-15 ( National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration ), 212–15 , p 4 . Available at https://www.noaa.gov/sites/default/files/legacy/document/2020/Mar/212-15.pdf

[16] What is Data Privacy SNIA . Available at https://secure.livechatinc.com/

[17] Data ethics Cognizant Glossary . Available at https://www.cognizant.com/us/en/glossary/data-ethics

[18] Kengadaran S, (2019) Ethics for Data Projects. Siddarth Kengadaran . Available at https://siddarth.design/ethics-for-data-projects-5af0af333e71

[19] Bhandari P, (2022) Ethical Considerations in Research | Types & Examples. Scribbr . Available at https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/research-ethics/

[20] What is Data Security? Data Security Definition and Overview IBM . Available at https://www.ibm.com/topics/data-security

[21] Molch K., Cosac R., (2020) Long Term Preservation of Earth Observation Space Data: Glossary of Acronyms and Terms. Available at https://ceos.org/document_management/Working_Groups/WGISS/Interest_Groups/Data_Stewardship/White_Papers/EO-DataStewardshipGlossary.pdf

[22] Karen Scarfone How to Perform a Data Risk Assessment, Step by Step. Tech Target . Available at https://www.techtarget.com/searchsecurity/tip/How-to-perform-a-data-risk-assessment-step-by-step

[23] What is Data Risk Management? Why You Should Care? (2022) The ECM Consultant . Available at https://theecmconsultant.com/data-risk-management/

[24] Data Sharing Agreements US Geological Survey . Available at https://www.usgs.gov/data-management/data-sharing-agreements

[25] Data License Agreement (2021) Dimewiki . Available at https://dimewiki.worldbank.org/Data_License_Agreement

[26] Intellectual property (2023) Wikipedia . Available at https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Intellectual_property&oldid=1171678348

[27] Foreground Intellectual Property: Everything You Need to Know UpCounsel . Available at https://www.upcounsel.com/foreground-intellectual-property

[28] Aitken M, Toreini E, Carmichael P, Coopamootoo K, Elliott K, van Moorsel A ( 2020 ) Establishing a social licence for Financial Technology: Reflections on the role of the private sector in pursuing ethical data practices. Big Data & Society 7 (1):2053951720908892. 10.1177/2053951720908892

[29] Sariyar M, Schluender I, Smee C, Suhr S ( 2015 ) Sharing and Reuse of Sensitive Data and Samples: Supporting Researchers in Identifying Ethical and Legal Requirements. Biopreservation and Biobanking 13 (4): 263 – 270 . 10.1089/bio.2015.0014

[30] Southekal P, (2022) Data Culture: What It Is And How To Make It Work. Forbes . Available at https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbestechcouncil/2022/06/27/data-culture-what-it-is-and-how-to-make-it-work/

[31] Scientific Integrity and Research Misconduct Available at https://www.usda.gov/our-agency/staff-offices/office-chief-scientist-ocs/scientific-integrity-and-research-misconduct