How to Write a Persuasive Essay (This Convinced My Professor!)

.png)

Table of contents

Meredith Sell

You can make your essay more persuasive by getting straight to the point.

In fact, that's exactly what we did here, and that's just the first tip of this guide. Throughout this guide, we share the steps needed to prove an argument and create a persuasive essay.

This AI tool helps you improve your essay > This AI tool helps you improve your essay >

Key takeaways: - Proven process to make any argument persuasive - 5-step process to structure arguments - How to use AI to formulate and optimize your essay

Why is being persuasive so difficult?

"Write an essay that persuades the reader of your opinion on a topic of your choice."

You might be staring at an assignment description just like this 👆from your professor. Your computer is open to a blank document, the cursor blinking impatiently. Do I even have opinions?

The persuasive essay can be one of the most intimidating academic papers to write: not only do you need to identify a narrow topic and research it, but you also have to come up with a position on that topic that you can back up with research while simultaneously addressing different viewpoints.

That’s a big ask. And let’s be real: most opinion pieces in major news publications don’t fulfill these requirements.

The upside? By researching and writing your own opinion, you can learn how to better formulate not only an argument but the actual positions you decide to hold.

Here, we break down exactly how to write a persuasive essay. We’ll start by taking a step that’s key for every piece of writing—defining the terms.

What Is a Persuasive Essay?

A persuasive essay is exactly what it sounds like: an essay that persuades . Over the course of several paragraphs or pages, you’ll use researched facts and logic to convince the reader of your opinion on a particular topic and discredit opposing opinions.

While you’ll spend some time explaining the topic or issue in question, most of your essay will flesh out your viewpoint and the evidence that supports it.

The 5 Must-Have Steps of a Persuasive Essay

If you’re intimidated by the idea of writing an argument, use this list to break your process into manageable chunks. Tackle researching and writing one element at a time, and then revise your essay so that it flows smoothly and coherently with every component in the optimal place.

1. A topic or issue to argue

This is probably the hardest step. You need to identify a topic or issue that is narrow enough to cover in the length of your piece—and is also arguable from more than one position. Your topic must call for an opinion , and not be a simple fact .

It might be helpful to walk through this process:

- Identify a random topic

- Ask a question about the topic that involves a value claim or analysis to answer

- Answer the question

That answer is your opinion.

Let’s consider some examples, from silly to serious:

Topic: Dolphins and mermaids

Question: In a mythical match, who would win: a dolphin or a mermaid?

Answer/Opinion: The mermaid would win in a match against a dolphin.

Topic: Autumn

Question: Which has a better fall: New England or Colorado?

Answer/Opinion: Fall is better in New England than Colorado.

Topic: Electric transportation options

Question: Would it be better for an urban dweller to buy an electric bike or an electric car?

Answer/Opinion: An electric bike is a better investment than an electric car.

Your turn: Walk through the three-step process described above to identify your topic and your tentative opinion. You may want to start by brainstorming a list of topics you find interesting and then going use the three-step process to find the opinion that would make the best essay topic.

2. An unequivocal thesis statement

If you walked through our three-step process above, you already have some semblance of a thesis—but don’t get attached too soon!

A solid essay thesis is best developed through the research process. You shouldn’t land on an opinion before you know the facts. So press pause. Take a step back. And dive into your research.

You’ll want to learn:

- The basic facts of your topic. How long does fall last in New England vs. Colorado? What trees do they have? What colors do those trees turn?

- The facts specifically relevant to your question. Is there any science on how the varying colors of fall influence human brains and moods?

- What experts or other noteworthy and valid sources say about the question you’re considering. Has a well-known arborist waxed eloquent on the beauty of New England falls?

As you learn the different viewpoints people have on your topic, pay attention to the strengths and weaknesses of existing arguments. Is anyone arguing the perspective you’re leaning toward? Do you find their arguments convincing? What do you find unsatisfying about the various arguments?

Allow the research process to change your mind and/or refine your thinking on the topic. Your opinion may change entirely or become more specific based on what you learn.

Once you’ve done enough research to feel confident in your understanding of the topic and your opinion on it, craft your thesis.

Your thesis statement should be clear and concise. It should directly state your viewpoint on the topic, as well as the basic case for your thesis.

Thesis 1: In a mythical match, the mermaid would overcome the dolphin due to one distinct advantage: her ability to breathe underwater.

Thesis 2: The full spectrum of color displayed on New England hillsides is just one reason why fall in the northeast is better than in Colorado.

Thesis 3: In addition to not adding to vehicle traffic, electric bikes are a better investment than electric cars because they’re cheaper and require less energy to accomplish the same function of getting the rider from point A to point B.

Your turn: Dive into the research process with a radar up for the arguments your sources are making about your topic. What are the most convincing cases? Should you stick with your initial opinion or change it up? Write your fleshed-out thesis statement.

3. Evidence to back up your thesis

This is a typical place for everyone from undergrads to politicians to get stuck, but the good news is, if you developed your thesis from research, you already have a good bit of evidence to make your case.

Go back through your research notes and compile a list of every …

… or other piece of information that supports your thesis.

This info can come from research studies you found in scholarly journals, government publications, news sources, encyclopedias, or other credible sources (as long as they fit your professor’s standards).

As you put this list together, watch for any gaps or weak points. Are you missing information on how electric cars versus electric bicycles charge or how long their batteries last? Did you verify that dolphins are, in fact, mammals and can’t breathe underwater like totally-real-and-not-at-all-fake 😉mermaids can? Track down that information.

Next, organize your list. Group the entries so that similar or closely related information is together, and as you do that, start thinking through how to articulate the individual arguments to support your case.

Depending on the length of your essay, each argument may get only a paragraph or two of space. As you think through those specific arguments, consider what order to put them in. You’ll probably want to start with the simplest argument and work up to more complicated ones so that the arguments can build on each other.

Your turn: Organize your evidence and write a rough draft of your arguments. Play around with the order to find the most compelling way to argue your case.

4. Rebuttals to disprove opposing theses

You can’t just present the evidence to support your case and totally ignore other viewpoints. To persuade your readers, you’ll need to address any opposing ideas they may hold about your topic.

You probably found some holes in the opposing views during your research process. Now’s your chance to expose those holes.

Take some time (and space) to: describe the opposing views and show why those views don’t hold up. You can accomplish this using both logic and facts.

Is a perspective based on a faulty assumption or misconception of the truth? Shoot it down by providing the facts that disprove the opinion.

Is another opinion drawn from bad or unsound reasoning? Show how that argument falls apart.

Some cases may truly be only a matter of opinion, but you still need to articulate why you don’t find the opposing perspective convincing.

Yes, a dolphin might be stronger than a mermaid, but as a mammal, the dolphin must continually return to the surface for air. A mermaid can breathe both underwater and above water, which gives her a distinct advantage in this mythical battle.

While the Rocky Mountain views are stunning, their limited colors—yellow from aspen trees and green from various evergreens—leaves the autumn-lover less than thrilled. The rich reds and oranges and yellows of the New England fall are more satisfying and awe-inspiring.

But what about longer trips that go beyond the city center into the suburbs and beyond? An electric bike wouldn’t be great for those excursions. Wouldn’t an electric car be the better choice then?

Certainly, an electric car would be better in these cases than a gas-powered car, but if most of a person’s trips are in their hyper-local area, the electric bicycle is a more environmentally friendly option for those day-to-day outings. That person could then participate in a carshare or use public transit, a ride-sharing app, or even a gas-powered car for longer trips—and still use less energy overall than if they drove an electric car for hyper-local and longer area trips.

Your turn: Organize your rebuttal research and write a draft of each one.

5. A convincing conclusion

You have your arguments and rebuttals. You’ve proven your thesis is rock-solid. Now all you have to do is sum up your overall case and give your final word on the subject.

Don’t repeat everything you’ve already said. Instead, your conclusion should logically draw from the arguments you’ve made to show how they coherently prove your thesis. You’re pulling everything together and zooming back out with a better understanding of the what and why of your thesis.

A dolphin may never encounter a mermaid in the wild, but if it were to happen, we know how we’d place our bets. Long hair and fish tail, for the win.

For those of us who relish 50-degree days, sharp air, and the vibrant colors of fall, New England offers a season that’s cozier, longer-lasting, and more aesthetically pleasing than “colorful” Colorado. A leaf-peeper’s paradise.

When most of your trips from day to day are within five miles, the more energy-efficient—and yes, cost-efficient—choice is undoubtedly the electric bike. So strap on your helmet, fire up your pedals, and two-wheel away to your next destination with full confidence that you made the right decision for your wallet and the environment.

3 Quick Tips for Writing a Strong Argument

Once you have a draft to work with, use these tips to refine your argument and make sure you’re not losing readers for avoidable reasons.

1. Choose your words thoughtfully.

If you want to win people over to your side, don’t write in a way that shuts your opponents down. Avoid making abrasive or offensive statements. Instead, use a measured, reasonable tone. Appeal to shared values, and let your facts and logic do the hard work of changing people’s minds.

Choose words with AI

You can use AI to turn your general point into a readable argument. Then, you can paraphrase each sentence and choose between competing arguments generated by the AI, until your argument is well-articulated and concise.

2. Prioritize accuracy (and avoid fallacies).

Make sure the facts you use are actually factual. You don’t want to build your argument on false or disproven information. Use the most recent, respected research. Make sure you don’t misconstrue study findings. And when you’re building your case, avoid logical fallacies that undercut your argument.

A few common fallacies to watch out for:

- Strawman: Misrepresenting or oversimplifying an opposing argument to make it easier to refute.

- Appeal to ignorance: Arguing that a certain claim must be true because it hasn’t been proven false.

- Bandwagon: Assumes that if a group of people, experts, etc., agree with a claim, it must be true.

- Hasty generalization: Using a few examples, rather than substantial evidence, to make a sweeping claim.

- Appeal to authority: Overly relying on opinions of people who have authority of some kind.

The strongest arguments rely on trustworthy information and sound logic.

Research and add citations with AI

We recently wrote a three part piece on researching using AI, so be sure to check it out . Going through an organized process of researching and noting your sources correctly will make sure your written text is more accurate.

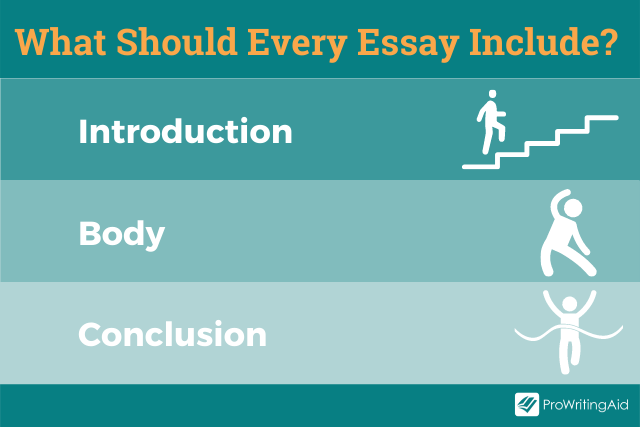

3. Persuasive essay structure

If you’re building a house, you start with the foundation and go from there. It’s the same with an argument. You want to build from the ground up: provide necessary background information, then your thesis. Then, start with the simplest part of your argument and build up in terms of complexity and the aspect of your thesis that the argument is tackling.

A consistent, internal logic will make it easier for the reader to follow your argument. Plus, you’ll avoid confusing your reader and you won’t be unnecessarily redundant.

The essay structure usually includes the following parts:

- Intro - Hook, Background information, Thesis statement

- Topic sentence #1 , with supporting facts or stats

- Concluding sentence

- Topic sentence #2 , with supporting facts or stats

- Concluding sentence Topic sentence #3 , with supporting facts or stats

- Conclusion - Thesis and main points restated, call to action, thought provoking ending

Are You Ready to Write?

Persuasive essays are a great way to hone your research, writing, and critical thinking skills. Approach this assignment well, and you’ll learn how to form opinions based on information (not just ideas) and make arguments that—if they don’t change minds—at least win readers’ respect.

Share This Article:

10 Longest Words in English Defined and Explained

.webp)

Finding the OG Writing Assistant – Wordtune vs. QuillBot

What’s a Split Infinitive? Definition + When to Avoid It

Looking for fresh content, thank you your submission has been received.

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

How to Write a Persuasive Essay: Tips and Tricks

Allison Bressmer

Most composition classes you’ll take will teach the art of persuasive writing. That’s a good thing.

Knowing where you stand on issues and knowing how to argue for or against something is a skill that will serve you well both inside and outside of the classroom.

Persuasion is the art of using logic to prompt audiences to change their mind or take action , and is generally seen as accomplishing that goal by appealing to emotions and feelings.

A persuasive essay is one that attempts to get a reader to agree with your perspective.

Ready for some tips on how to produce a well-written, well-rounded, well-structured persuasive essay? Just say yes. I don’t want to have to write another essay to convince you!

How Do I Write a Persuasive Essay?

What are some good topics for a persuasive essay, how do i identify an audience for my persuasive essay, how do you create an effective persuasive essay, how should i edit my persuasive essay.

Your persuasive essay needs to have the three components required of any essay: the introduction , body , and conclusion .

That is essay structure. However, there is flexibility in that structure.

There is no rule (unless the assignment has specific rules) for how many paragraphs any of those sections need.

Although the components should be proportional; the body paragraphs will comprise most of your persuasive essay.

How Do I Start a Persuasive Essay?

As with any essay introduction, this paragraph is where you grab your audience’s attention, provide context for the topic of discussion, and present your thesis statement.

TIP 1: Some writers find it easier to write their introductions last. As long as you have your working thesis, this is a perfectly acceptable approach. From that thesis, you can plan your body paragraphs and then go back and write your introduction.

TIP 2: Avoid “announcing” your thesis. Don’t include statements like this:

- “In my essay I will show why extinct animals should (not) be regenerated.”

- “The purpose of my essay is to argue that extinct animals should (not) be regenerated.”

Announcements take away from the originality, authority, and sophistication of your writing.

Instead, write a convincing thesis statement that answers the question "so what?" Why is the topic important, what do you think about it, and why do you think that? Be specific.

How Many Paragraphs Should a Persuasive Essay Have?

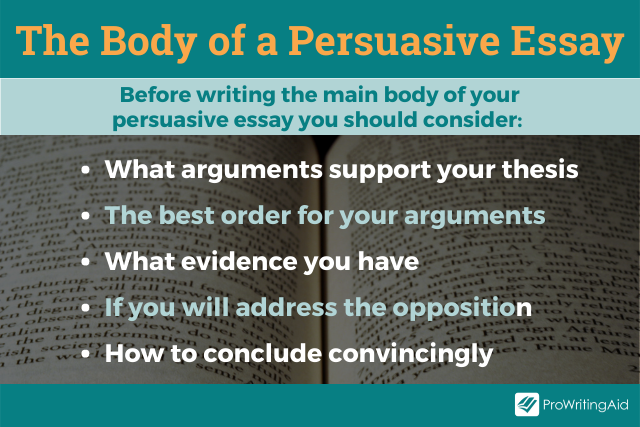

This body of your persuasive essay is the section in which you develop the arguments that support your thesis. Consider these questions as you plan this section of your essay:

- What arguments support your thesis?

- What is the best order for your arguments?

- What evidence do you have?

- Will you address the opposing argument to your own?

- How can you conclude convincingly?

TIP: Brainstorm and do your research before you decide which arguments you’ll focus on in your discussion. Make a list of possibilities and go with the ones that are strongest, that you can discuss with the most confidence, and that help you balance your rhetorical triangle .

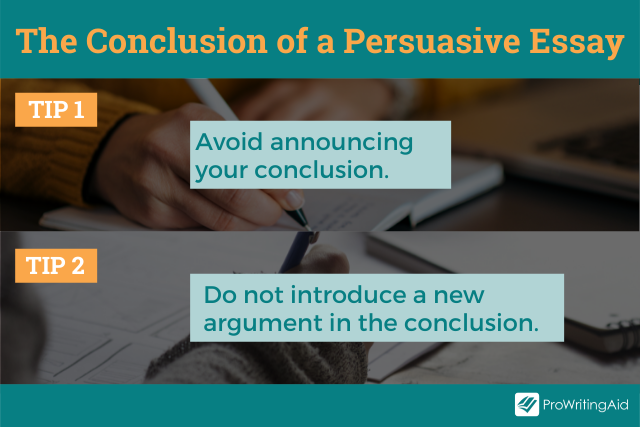

What Should I Put in the Conclusion of a Persuasive Essay?

The conclusion is your “mic-drop” moment. Think about how you can leave your audience with a strong final comment.

And while a conclusion often re-emphasizes the main points of a discussion, it shouldn’t simply repeat them.

TIP 1: Be careful not to introduce a new argument in the conclusion—there’s no time to develop it now that you’ve reached the end of your discussion!

TIP 2 : As with your thesis, avoid announcing your conclusion. Don’t start your conclusion with “in conclusion” or “to conclude” or “to end my essay” type statements. Your audience should be able to see that you are bringing the discussion to a close without those overused, less sophisticated signals.

If your instructor has assigned you a topic, then you’ve already got your issue; you’ll just have to determine where you stand on the issue. Where you stand on your topic is your position on that topic.

Your position will ultimately become the thesis of your persuasive essay: the statement the rest of the essay argues for and supports, intending to convince your audience to consider your point of view.

If you have to choose your own topic, use these guidelines to help you make your selection:

- Choose an issue you truly care about

- Choose an issue that is actually debatable

Simple “tastes” (likes and dislikes) can’t really be argued. No matter how many ways someone tries to convince me that milk chocolate rules, I just won’t agree.

It’s dark chocolate or nothing as far as my tastes are concerned.

Similarly, you can’t convince a person to “like” one film more than another in an essay.

You could argue that one movie has superior qualities than another: cinematography, acting, directing, etc. but you can’t convince a person that the film really appeals to them.

Once you’ve selected your issue, determine your position just as you would for an assigned topic. That position will ultimately become your thesis.

Until you’ve finalized your work, consider your thesis a “working thesis.”

This means that your statement represents your position, but you might change its phrasing or structure for that final version.

When you’re writing an essay for a class, it can seem strange to identify an audience—isn’t the audience the instructor?

Your instructor will read and evaluate your essay, and may be part of your greater audience, but you shouldn’t just write for your teacher.

Think about who your intended audience is.

For an argument essay, think of your audience as the people who disagree with you—the people who need convincing.

That population could be quite broad, for example, if you’re arguing a political issue, or narrow, if you’re trying to convince your parents to extend your curfew.

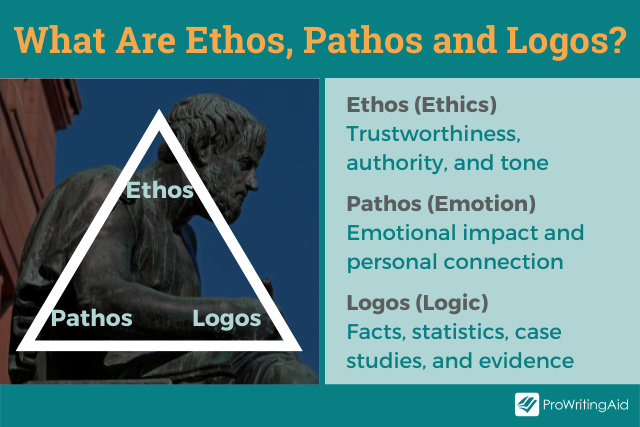

Once you’ve got a sense of your audience, it’s time to consult with Aristotle. Aristotle’s teaching on persuasion has shaped communication since about 330 BC. Apparently, it works.

Aristotle taught that in order to convince an audience of something, the communicator needs to balance the three elements of the rhetorical triangle to achieve the best results.

Those three elements are ethos , logos , and pathos .

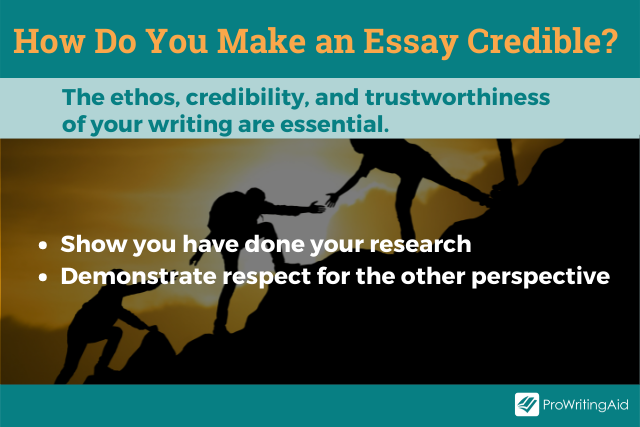

Ethos relates to credibility and trustworthiness. How can you, as the writer, demonstrate your credibility as a source of information to your audience?

How will you show them you are worthy of their trust?

- You show you’ve done your research: you understand the issue, both sides

- You show respect for the opposing side: if you disrespect your audience, they won’t respect you or your ideas

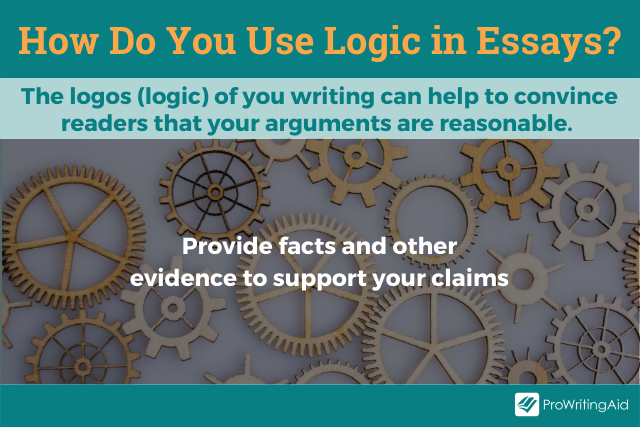

Logos relates to logic. How will you convince your audience that your arguments and ideas are reasonable?

You provide facts or other supporting evidence to support your claims.

That evidence may take the form of studies or expert input or reasonable examples or a combination of all of those things, depending on the specific requirements of your assignment.

Remember: if you use someone else’s ideas or words in your essay, you need to give them credit.

ProWritingAid's Plagiarism Checker checks your work against over a billion web-pages, published works, and academic papers so you can be sure of its originality.

Find out more about ProWritingAid’s Plagiarism checks.

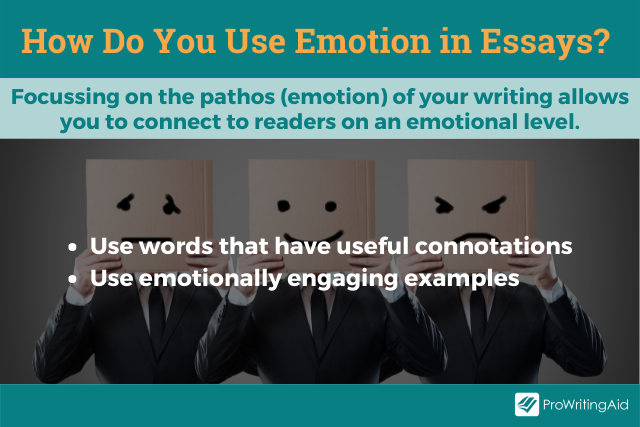

Pathos relates to emotion. Audiences are people and people are emotional beings. We respond to emotional prompts. How will you engage your audience with your arguments on an emotional level?

- You make strategic word choices : words have denotations (dictionary meanings) and also connotations, or emotional values. Use words whose connotations will help prompt the feelings you want your audience to experience.

- You use emotionally engaging examples to support your claims or make a point, prompting your audience to be moved by your discussion.

Be mindful as you lean into elements of the triangle. Too much pathos and your audience might end up feeling manipulated, roll their eyes and move on.

An “all logos” approach will leave your essay dry and without a sense of voice; it will probably bore your audience rather than make them care.

Once you’ve got your essay planned, start writing! Don’t worry about perfection, just get your ideas out of your head and off your list and into a rough essay format.

After you’ve written your draft, evaluate your work. What works and what doesn’t? For help with evaluating and revising your work, check out this ProWritingAid post on manuscript revision .

After you’ve evaluated your draft, revise it. Repeat that process as many times as you need to make your work the best it can be.

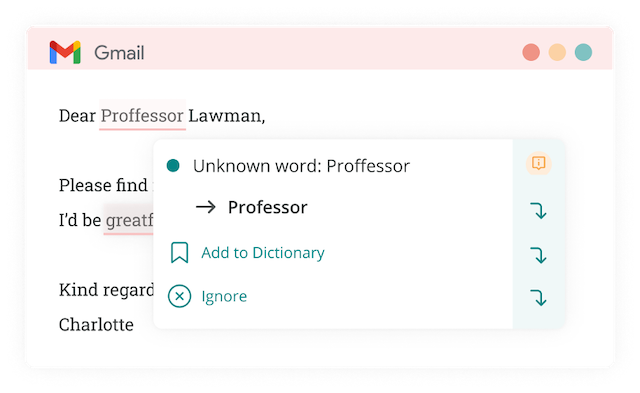

When you’re satisfied with the content and structure of the essay, take it through the editing process .

Grammatical or sentence-level errors can distract your audience or even detract from the ethos—the authority—of your work.

You don’t have to edit alone! ProWritingAid’s Realtime Report will find errors and make suggestions for improvements.

You can even use it on emails to your professors:

Try ProWritingAid with a free account.

How Can I Improve My Persuasion Skills?

You can develop your powers of persuasion every day just by observing what’s around you.

- How is that advertisement working to convince you to buy a product?

- How is a political candidate arguing for you to vote for them?

- How do you “argue” with friends about what to do over the weekend, or convince your boss to give you a raise?

- How are your parents working to convince you to follow a certain academic or career path?

As you observe these arguments in action, evaluate them. Why are they effective or why do they fail?

How could an argument be strengthened with more (or less) emphasis on ethos, logos, and pathos?

Every argument is an opportunity to learn! Observe them, evaluate them, and use them to perfect your own powers of persuasion.

Be confident about grammar

Check every email, essay, or story for grammar mistakes. Fix them before you press send.

Allison Bressmer is a professor of freshman composition and critical reading at a community college and a freelance writer. If she isn’t writing or teaching, you’ll likely find her reading a book or listening to a podcast while happily sipping a semi-sweet iced tea or happy-houring with friends. She lives in New York with her family. Connect at linkedin.com/in/allisonbressmer.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

Writing an Argumentative Research Paper

- Library Resources

- Books & EBooks

- What is an Argumentative Research Essay?

- Choosing a Topic

- How to Write a Thesis Statement Libguide

- Structure & Outline

- Types of Sources

- OER Resources

- Copyright, Plagiarism, and Fair Use

Examples of argumentative essays

Skyline College libguides: MLA Sample Argumentative Papers

Ebooks in Galileo

Video Tutorial

Structure & Outline

Usually written in the five-paragraph structure, the argumentative essay format consists of an introduction, 2-3 body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

A works cited page or reference page (depending on format) will be included at the end of the essay along with in-text citations within the essay.

When writing an argumentative research essay, create an outline to structure the research you find as well as help with the writing process. The outline of an argumentative essay should include an introduction with thesis statement, 3 main body paragraphs with supporting evidence and opposing viewpoints with evidence to disprove, along with an conclusion.

The example below is just a basic outline and structure

I. Introduction: tells what you are going to write about. Basic information about the issue along with your thesis statement.

A. Basic information

B. Thesis Statement

II. Body 1 : Reason 1 write about the first reason that proves your claim on the issue and give supporting evidence

A. supporting evidence

B. Supporting evidence

II. Body 2 .: Reason 2 write about the third reason that proves your claim on the issue and give supporting evidence

A. supporting evidence

III. Body 3 : Reason 3 write about the fourth reason that proves your claim on the issue and give supporting evidence

IV. Counter arguments and responses. Write about opposing viewpoints and use evidence to refute their argument and persuade audience in your direction or viewpoint

A. Arguments from other side of the issue

B. Refute the arguments

V. Conclusion

- << Previous: How to Write a Thesis Statement Libguide

- Next: Conducting Research >>

- Last Updated: Jan 24, 2024 1:23 PM

- URL: https://wiregrass.libguides.com/c.php?g=1188383

Research Methods: Persuasive Arguments

- Annotated Bibliographies

- Literature Reviews

- Scoping Reviews

- Systematic Reviews

- Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

- Persuasive Arguments

- Subject Specific Methodology

What is Persuasive Research?

Persuasive or argumentative research asks you to take one side of an issue and support this side by looking at the research, facts, and news about the topic. You will need to research both sides of the topic, and may be required to conduct interviews, surveys, observations, or experiments to gather data for your argument.

Start your argumentative research by selecting a topic and creating a clear and concise thesis.

- Start My Research This is the library's main search tool. Search numerous resources available through Auraria Library including journals, articles, media, books, and more. Limit by material type, publication date, author, and more.

Excellent series of books on controversial topics include:

- Taking Sides

- You Decide

Add the series name to your topic to see if there is a volume for you.

You can also add words like “ controversial ” “ debates ” “ pro and con ”, or “ arguments ” to your search.

Multimedia Resources

- American Rhetoric Index to and growing database of 5000+ full text, audio and video (streaming) versions of public speeches, sermons, legal proceedings, lectures, debates, interviews, other recorded media events, and a declaration or two.

Key Resources

- CQ Researcher Online This link opens in a new window Provides in-depth coverage of the most important issues of the day. A wide range of topics are covered, from social and political issues to environment, health, education, crime, climate change, public policy, and science and technology.

- Opposing Viewpoints This link opens in a new window Presents an array of perspectives on a wide range of topics using fully cited articles, essays, primary documents, biographies, statistics, court cases, profiles of government and special interest groups, websites, and podcasts. Topics cover politics, the environment, health care, education, energy, and much, much more.

- ProCon.org This website promotes critical thinking, education, and informed citizenship by presenting controversial issues in a nonpartisan,primarily pro-con format. The topics researched are up-to-the-minute and relevant to today's world.

Special Resources

Congressional Hearings are an excellent and sometimes overlooked resource for argumentative and position papers. When members of Congressional committees convene a hearing, they call expert witnesses from all sides of an issue. Witnesses testify regarding the issue, and they also must testify as to their credentials to demonstrate their experience and knowledge on the issue. In addition, the exact transcripts of the experts’ words are provided so they make an excellent source for quotes to reinforce your paper's position.

- Congressional Publications This link opens in a new window Comprehensive access to U.S. legislative information, including laws, proposed bills and statutes, hearings, legislative histories, congressional committee information, campaign contributions and PAC activities, the "Congressional Record", the historical "Congressional Index", and the "Serial Set", as well as articles from the "National Journal". Right-hand column has tips on how to use the Congressional interface.Note: Email yourself a copy of the article instead of a link.

- U.S. House of Representatives Search for hearings. A simple search like "global warming hearing" will work. The hearing can be viewed as a webcast or as a written transcript.

- U.S. Senate Search for hearings. A simple search like "global warming hearing" will work. The hearing can be viewed as a webcast or as a written transcript.

Newspapers are a good source of information for papers and speeches. Find articles reporting on current events, and opinion articles on major issues.

- Access World News This link opens in a new window Includes thousands of full text local, regional, national and international newspapers, as well as newswires, blogs, and more. Has Colorado publications, including The Denver Post. Formerly known as Newsbank.

In addition to America's News, there are some news databases that lend themselves to argumentative and persuasive assignments. These resources cover newspapers that may depart from the majority opinions found in the Washington Post, New York Times, or other "white bread" papers. For example, a topic like immigration might be covered very differently in an ethnic newspaper than in the Denver Post.

- Left Index This link opens in a new window A complete guide to the diverse literature of the left, with an emphasis on political, economic, social and culturally engaged scholarship inside and outside academia. A secondary emphasis is on significant but little known sources of news and ideas. Covers over 250 periodical publications + many classic texts.

- Ethnic NewsWatch This link opens in a new window Ethnic NewsWatch is a current resource of full-text newspapers, magazines, and journals of the ethnic and minority press. The complete collection also includes the module Ethnic NewsWatch: A History, which provides historical coverage of Native American, African American, and Hispanic American periodicals from 1959-1989. Together, these resources provide access to a full-text collection of more than 2.5 million articles from over 340 publications, including articles from major scholarly journals on ethnic studies.

- << Previous: Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

- Next: Subject Specific Methodology >>

- Last Updated: Feb 29, 2024 12:00 PM

- URL: https://guides.auraria.edu/researchmethods

1100 Lawrence Street Denver, CO 80204 303-315-7700 Ask Us Directions

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

An inclusive, real-world investigation of persuasion in language and verbal behavior

Vivian p. ta.

1 Department of Psychology, Lake Forest College, 555 N. Sheridan Road, Lake Forest, IL 60045 USA

Ryan L. Boyd

2 Department of Psychology, Data Science Institute, Security Lancaster, Lancaster University, Lancaster, UK

Sarah Seraj

3 Department of Psychology, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX USA

Anne Keller

Caroline griffith.

4 Department of Counselor Education and Human Services, University of Dayton, Dayton, OH USA

Alexia Loggarakis

5 School of Social Work, Loyola University Chicago, Chicago, IL USA

Lael Medema

Linguistic features of a message necessarily shape its persuasive appeal. However, studies have largely examined the effect of linguistic features on persuasion in isolation and do not incorporate properties of language that are often involved in real-world persuasion. As such, little is known about the key verbal dimensions of persuasion or the relative impact of linguistic features on a message’s persuasive appeal in real-world social interactions. We collected large-scale data of online social interactions from a social media website in which users engage in debates in an attempt to change each other’s views on any topic. Messages that successfully changed a user’s views are explicitly marked by the user themselves. We simultaneously examined linguistic features that have been previously linked with message persuasiveness between persuasive and non-persuasive messages. Linguistic features that drive persuasion fell along three central dimensions: structural complexity, negative emotionality, and positive emotionality. Word count, lexical diversity, reading difficulty, analytical language, and self-references emerged as most essential to a message’s persuasive appeal: messages that were longer, more analytic, less anecdotal, more difficult to read, and less lexically varied had significantly greater odds of being persuasive. These results provide a more parsimonious understanding of the social psychological pathways to persuasion as it operates in the real world through verbal behavior. Our results inform theories that address the role of language in persuasion, and provide insight into effective persuasion in digital environments.

Introduction

Understanding persuasion —how people can fundamentally alter the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of others—is a cornerstone of social psychology. Historically, social influence has been outstandingly difficult to study in the real-world, requiring researchers to piece together society-level puzzles either in the abstract [ 1 ] or through carefully-crafted field studies [ 2 ]. In recent years, technology has driven interest in studying social influence as digital traces make it possible to study how the behaviors of one individual or group cascade to change others’ behaviors [ 3 , 4 ]. Nevertheless, most social processes are complex, to the point where they are very difficult to study as they operate outside of the lab. However, the availability of digital data and computational techniques provide a ripe opportunity to begin understanding the precise mechanisms by which people influence the thoughts and feelings of others.

Today, persuasion is often transacted—partially or wholly—through verbal interactions that take place on the internet [ 5 ]: a message is transmitted from one person to another through the use of language, altering the recipient’s attitude. As such, researchers have sought to identify linguistic features 1 that are linked to a message’s persuasive appeal. A relatively sizable number of linguistic features that are important in message persuasiveness have emerged from this body of research and include features that indicate what a message conveys as well as how it was conveyed (Table (Table1). 1 ). Models of persuasion, such as the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) [ 6 ], have been used to identify these linguistic features and explain how they affect message persuasiveness.

Summary of linguistic features and predictions

Despite the impressive corpus of studies to date, the existing literature has several limitations. Studies have largely examined the effect of linguistic features on persuasion in isolation by only focusing on a small number of linguistic features (i.e., one or two) at a time. While this body of literature has collectively identified a relatively sizable number of linguistic features that are linked to message persuasiveness, it remains unclear how these links, taken together, inform the social aspects of verbal behavior in persuasion. In other words, what do the linguistic features connected with message persuasiveness reveal about the key verbal behaviors involved in persuasion? As language provides “a rich stream of ongoing social processes” [ 7 ], synthesizing these findings can provide a more complete understanding of the social psychological pathways to persuasion.

In the same vein, real-world messages are constructed using a varied combination of linguistic features to transmit complex thoughts, emotions, and information to others. Nevertheless, studies tend to examine how a single linguistic feature (or a small set of features) correlate with persuasion without taking into account other potentially important linguistic features within a given message [ 8 , 9 ]. The meaning of a given word or feature in any text is dependent on the context by which it was used which can be inferred by the words and features that surround it [ 10 , 11 ]. As such, the effect of any particular linguistic feature on message persuasiveness can be attenuated by the presence of other features in the message. As they are typically studied in isolation, little is known about the relative impact of linguistic features on a message’s persuasive appeal.

Furthermore, studies that examine the effect of linguistic features on persuasion tend to focus on persuasion in terms of engaging in specific behaviors [ 3 , 12 – 14 ] rather than changing attitudes in general. Persuading people to engage in a specific behavior is conceptually distinct from changing people’s attitude on a topic. Although changes in behavior can facilitate changes in attitude, changes in behavior can also be dependent on attitude change (e.g., an individual may not engage in behavior change unless they believe that the behavior will result in a desirable outcome). Although changes in behavior can facilitate changes in attitude, changes in behavior does not always indicate that attitude change has occurred (e.g., an individual may decide to ultimately receive the COVID-19 vaccine because their employer requires it and not because their views regarding vaccines have changed) [ 15 ].

Finally, many studies that investigate the effect of linguistic features on persuasion are conducted in controlled lab settings [ 16 , 17 ] due to the sheer difficulty of studying persuasion as it unfolds in the real-world. Given that persuasion often takes place through online social interactions [ 5 ], there is a need to study persuasion in this setting. Doing so also enables researchers to better understand how digital environments influence the process of persuasion, especially as digital environments are now progressively constructed to persuade the attitudes and behaviors of users [ 18 ] and there is “little consensus on how to persuade effectively within the digital realm” [ 19 ].

We sought to address these limitations in the current study. Specifically, we collected large-scale data from r/ChangeMyView , an online public forum on the social media website Reddit where users engage in debates in an attempt to change each other’s views on any topic. Most importantly, messages that successfully changed a user’s views are explicitly marked by the user themselves. That is, individuals are exposed to several messages and explicitly identified the message(s) that actually changed their views. We simultaneously examined linguistic features that have been previously linked with message persuasiveness (Table (Table1) 1 ) between persuasive and non-persuasive messages to test the following research questions:

- What are the key linguistic dimensions of persuasion? Given that a relatively sizable number of linguistic features have been linked with persuasion, we first sought to determine whether these features could be meaningfully reduced to a smaller number of dimensions representing the key verbal processes of persuasion. We then assessed whether these dimensions were uniquely predictive of persuasion when controlling for the effects of the remaining dimensions.

- Which individual linguistic features, when assessed simultaneously, are the most essential and relevant to a message’s persuasive appeal? We then simultaneously assessed all linguistic features that have been linked with message persuasiveness in a single model to examine the relative impact of the features on a message’s persuasive appeal to identify features that were most crucial to message persuasiveness.

While theory-driven predictions can be made regarding how each linguistic feature relates to persuasion, there has been a considerable amount of variability across studies in terms of which features positively or negatively relate to persuasion, as well as studies that show mixed or inconclusive results pertaining to the effect of a given linguistic feature on persuasion (see Table Table1). 1 ). Given that our primary goal was to obtain a more unified understanding of the social psychological pathways to persuasion via language, the current study is guided by a jointly data-driven and exploratory approach, with results informing our understanding of the directional relationship between the linguistic features and message persuasiveness. Overall, assessing the interplay between important linguistic features on persuasion using large-scale, real-world data help inform theories, such as ELM, that address how linguistic features influence persuasion to provide a parsimonious and ecologically-valid understanding of the social psychological processes that shape persuasion.

Although some previous studies have used r/ChangeMyView data to investigate the effect of linguistic features on persuasion, they differ from the current investigation in important ways. The types and combinations of linguistic features that have been examined vary across studies and typically feature a mix of linguistic features that have and have not been linked to persuasion. For example, Tan et al. [ 21 ] examined how some persuasion-linked linguistic features (including arousal, valence, reading difficulty, and hedges), some non-persuasion-linked features (e.g., formatting features such as use of italics and boldface), and interaction dynamics (e.g., the time a replier enters a debate) were associated with successful persuasion. Wei et al. [ 22 ] investigated how surface text features (e.g., reply length, punctuation), social interaction features (e.g., the number of replies stemming from a root comment), and argumentation-related features (e.g., argument relevance and originality) related to persuasion. Musi et al. [ 23 ] assessed the distribution of argumentative concessions in persuasive versus non-persuasive comments, and Priniski and Horne [ 24 ] examined persuasion through the presentation of evidence only in sociomoral topics. Moreover, studies tend to have greater emphasis on model building to accurately detect persuasive content online rather than interpretability and a more unified understanding of the social psychological pathways to persuasion via language. For instance, Khazaei et al. [ 20 ] assessed how all LIWC-based features varied across persuasive and non-persuasive replies and used this information to train a machine learning model to identify persuasive responses.

Data collection

We used data from the Reddit sub-community (i.e., “subreddit”) r/ChangeMyView , a forum in which users post their own views (referred to as “original posters”, or “OPs”) on any topic and invite others to debate them. Those who debate the OP (referred to as “repliers”) reply to the OP’s post in an attempt to change the OP’s view. The OP will award a delta (∆) to particular replies that changed their original views.

Using data from r/ChangeMyView presents several advantages. All replies in r/ChangeMyView are written with the purpose of persuasion. The replies that successfully change an OP’s view are explicitly marked by the OP themselves, allowing for a sample of persuasive and non-persuasive replies. All OPs and repliers must adhere to the official policies 2 of r/ChangeMyView . For instance, OPs are required to explain at a reasonable length (using 500 characters or more) why they hold their views and to interact with repliers within a reasonable time frame. Replies must be substantial, adequate, and on-topic. Because these policies are enforced by moderators, the resulting interactions are high in quality [ 21 ] and are conducted under similar conditions with similar expectations. OPs can also post their view on any topic, allowing for an examination of persuasion across a wide variety of topics.

All top-level replies (direct replies to the OP’s original statement of views) posted between January 2013 and October 2018 were initially collected from the Pushshift database [ 25 ]. We focused only on the top-level replies and omitted any additional replies that were in response to a direct reply (i.e., a direct reply’s “children”). This ensured that replies that were deemed persuasive were due to its contents and not due to any resulting “back-and-forth” interactions given that deltas can also be awarded to downstream replies. We also omitted any top-level replies that were made by a post’s OP and any replies that received a delta in which the delta was not awarded by the OP. Because the data contained a substantially greater number of non-persuasive replies (99.39%) than persuasive ones, analyses were conducted on a balanced subsample that included all top-level replies that were awarded a delta and a random subsample of top-level replies that were not awarded a delta that came from the original posts in which at least one delta was awarded. This allowed us to compare the persuasive and non-persuasive replies from the same original post while bypassing issues associated with class imbalances [ 26 ].

As an example, consider a parent post that garnered two top-level replies that were awarded a delta, and three top-level replies that were not awarded a delta. In this case, the two top-level replies that were awarded a delta were included in the subsample and two out of the three top-level replies that were not awarded a delta would be randomly selected for inclusion in the subsample. Using the random number generator in Microsoft Excel, the 3 top-level replies that were not awarded a delta were assigned a random number between 1 and 100. Replies with the lowest two values were then selected for inclusion in the subsample. Parent posts almost always contained a greater number of top-level replies that were not awarded a delta than top-level replies that were awarded a delta. However, for the very few instances in which a parent post contained a greater number of top-level replies that were awarded a delta than top-level replies that were not awarded a delta, we included all top-level replies in the subsample ( N = 9020 top-level replies; n = 4515 top-level replies that were awarded a delta; n = 4505 top-level replies that were not awarded a delta). Example persuasive and non-persuasive replies can be found in Table Table2 2 .

Example replies

Note : All example replies were derived from different parent posts

To gain an initial understanding of the types of topics that were raised for debate in the subreddit, we randomly selected 100 replies from the final dataset and manually coded their content. Six overarching topics emerged: legal and politics; race, culture, and gender; business and work; science and technology; behavior, attitudes, and relationships; and recreation. More information regarding debated topics can be found in the supplementary materials. 3 .

Linguistic features

Prior to extracting linguistic features from our data, we conducted a cursory search of the psychological literature to identify prominent linguistic features reported to have a significant relationship with message persuasiveness in at least one published study. These linguistic features are listed in Table Table1. 1 . Each reply in the r/ChangeMyView dataset was analyzed separately using Language Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) [ 27 ] which calculates the percentage-use of words belonging to psychologically or linguistically meaningful categories. We used LIWC to quantify word count, analytic thinking (analytical thinking formula = articles + prepositions—personal pronouns—impersonal pronouns—auxiliary verbs—conjunctions—adverbs—negations; relative frequencies are normalized within LIWC2015 to a 0-to-100 scale, with higher scores reflecting more analytical language and lower scores reflecting more informal and narrative-like language), the percentage-use of self-references (i.e., first-person singular pronouns, or “i-words”), and the percentage-use of certainty terms in each reply within our corpus. Dictionaries of terms that have been rated on emotionality 4 (i.e., valence, arousal, and dominance) from [ 28 ] were imported into LIWC to measure the percentage-use of language that scored high and low on valence, arousal, and dominance. A dictionary of hedges from [ 29 ] was also imported into LIWC to measure the percentage-use of hedges. Following [ 21 ], the use of examples was measured by occurrences of “for example”, “for instance”, and “e.g.”. Language abstraction/concreteness was measured using the linguistic category model, with higher scores indicating higher levels of language abstraction and lower scores indicating lower levels of language abstraction (i.e., greater language concreteness; formula for calculation = [(Descriptive Action Verbs × 1) + (Interpretative Action Verb × 2) + (State Verb × 3) + (Adjectives × 4)]/(Descriptive Action Verbs + Interpretative Action Verbs + State Verbs + Adjectives)) [ 30 ]. Type-token ratio, the ratio between the number of unique words in a message and the total number of words in the given message [ 31 ], was used to measure lexical diversity with higher scores indicating greater lexical diversity (type-token ratio formula = number of unique lexical terms/total number of words). Last, reading difficulty was measured via the SMOG Index which estimates the years of education the average person needs to completely comprehend a piece of text (SMOG Index formula = 1.0430 [√number of polysyllables × (30/number of sentences)] + 3.1291). Because a higher SMOG score indicates that higher education is needed to comprehend a piece of text, higher reading difficulty scores represent text that is more difficult to read and lower scores represent text that is easier to read [ 32 ]. More information about these linguistic features and example replies that scored high and low on each linguistic feature are reported in the supplementary.

Given that a relatively sizable number of linguistic features have been linked with persuasion, we first determined whether these features could be meaningfully reduced to a smaller number of dimensions representing the key verbal processes of persuasion. Second, we determined whether these dimensions were each uniquely predictive of persuasion when controlling for the effects of the remaining dimensions. Third, we simultaneously assessed all linguistic features that have been linked with message persuasiveness in a single model to understand how linguistic features interact with one another to influence a message’s persuasive appeal and identify features most crucial to message persuasiveness. All data and analytic code can be found in the supplementary. Descriptive statistics, zero-order correlations between all variables, and complete analytic outputs for all analyses are presented in the supplementary.

To identify the key linguistic dimensions of persuasion (RQ 1), we submitted all linguistic features into a principal components analysis (PCA) with a varimax rotation. Bartlett’s Sphericity Test ( p < 0.001) and the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin metric (KMO = 0.55) suggested that our data were suitable for analysis. Features with factor loadings greater than the absolute value of 0.50 were retained and used to quantify principal components. Three principal components were extracted that collectively accounted for 36.28% of the total variance: structural complexity, negative emotionality, and positive emotionality (see Table Table3). 3 ). Structural complexity had high loadings in the direction of lower lexical diversity, higher word count, and greater reading difficulty. Negative emotionality had high loadings in the direction of greater percentage-use of terms that scored low on valence and low on dominance. Positive emotionality had high loadings in the direction of greater percentage-use of terms that scored high on dominance, high on valence, and hedges.

Results of PCA with Varimax Rotation

To assess if all three dimensions were uniquely important to message persuasiveness, we entered each component into a multilevel logistic regression analysis using lme4 [ 33 ]. This procedure corrects for non-independence of replies (i.e., replies to the same parent post) on the dependent variable: persuasion (delta awarded = 1, no delta awarded = 0). We include random intercepts for replies nested within parent posts and replies nested within repliers (i.e., some repliers provided replies to multiple original posts). All three components emerged as significant predictors of persuasion. For a one-unit increase in structural complexity, the odds of receiving a delta increase by a factor of 2.25, 95% CI [2.11, 2.39]. For a one-unit increase in negative emotionality, the odds of receiving a delta decrease by a factor of 0.89, 95% CI [0.85, 0.94]. For a one-unit increase in positive emotionality, the odds of receiving a delta also decrease by a factor of 0.92, 95% CI [0.88, 0.97]. Post-hoc power analyses conducted using the simr package in R (Version 1.0.5) [ 34 ] revealed that we had at least 96% power to detect a small effect (i.e., 0.15) for each of these factors on persuasion.

Next, the individual linguistic features were assessed simultaneously to identify those that were the most essential and relevant to a message’s persuasive appeal (RQ 2). A logistic least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression was performed using glmmLasso [ 35 ]. A LASSO regression is a penalized regression analysis that performs variable selection to prevent overfitting by adding a penalty ( λ ) to the cost function (i.e., the sum of squared errors) equal to the sum of the absolute value of the coefficients. This penalty results in sparse models with few coefficients. In other words, this method selects a parsimonious set of variables that best predict the outcome variable and has many advantages over other feature selection methods [ 36 ]. All linguistic features were entered into the LASSO regression model. A grid search was performed to identify the most optimal shrinkage parameter based on BIC. Five features emerged with nonzero coefficients: word count, lexical diversity, reading difficulty, analytical thinking, and self-references (Table (Table4 4 ).

Results of LASSO regression

*** p < 0.001; ** p < 0.01; λ = 62

These variables were subsequently entered into a multilevel logistic regression. Again, persuasion was entered as the dependent variable and we included random intercepts for replies nested within parent posts and replies nested within repliers. All five predictors emerged as significant predictors of persuasion. Specifically, for a one-unit increase in word count, the odds of receiving a delta increase by a factor of 1.23, 95% CI [1.13, 1.35]. For a one-unit increase in reading difficulty scores (i.e., greater difficulty in reading comprehension), the odds of receiving a delta increase by a factor of 1.10, 95% CI [1.04, 1.16]. For a one-unit increase in analytical thinking, the odds of receiving a delta increase by a factor of 1.10, 95% CI [1.05, 1.17]. For a one-unit increase in self-references, the odds of receiving a delta decrease by a factor of 0.92, 95% CI [0.87, 0.98]. Last, for a one-unit increase in lexical diversity, the odds of receiving a delta decrease by a factor of 0.54, 95% CI [0.50, 0.59]. Post-hoc power analyses conducted using the simr [ 34 ] revealed that we had at least 96% power to detect a small effect (i.e., 0.15) for each of these predictors on persuasion.

Previous studies have largely examined the effect of linguistic features on persuasion in isolation and do not incorporate properties of language that are often involved in real-world persuasion. As such, little is known about the key verbal dimensions of persuasion or the relative impact of linguistic features on a message’s persuasive appeal in real-world social interactions. To address these limitations, we collected large-scale data of online social interactions from a public forum in which users engage in debates in an attempt to change each other’s views on any topic. Messages that successfully changed a user’s views are explicitly marked by the user themselves. We simultaneously examined linguistic features that have been previously linked with message persuasiveness between persuasive and non-persuasive messages. Our findings provide a parsimonious and ecologically-valid understanding of the social psychological pathways to persuasion as it operates in the real world through verbal behavior.

Three linguistic dimensions appeared to underlie the tested features: structural complexity, negative emotionality, and positive emotionality. Each dimension uniquely predicted persuasion when the effects of the remaining dimensions were statistically controlled, with greater structural complexity exhibiting the highest odds of persuasion. Interestingly, messages marked with less emotionality had higher odds of persuasion than messages marked with more emotionality, regardless of whether it was positive or negative. Emotionality can help persuasion in specific contexts [ 37 , 38 ], but emotional appeals can also backfire when audiences prefer cognitive appeals [ 39 ]. Given that OPs were publicly inviting others to debate them, it is plausible that they preferred cognitively-appealing responses—ones that include an abundance of clear and valid reasons to support an argument—rather than emotionally-appealing responses.

The linguistic features that made a message longer, more analytic, less anecdotal, more difficult to read, and less lexically diverse were most essential to a message’s persuasive appeal and uniquely predictive of persuasion. Longer messages provide more context and likely contain more arguments than shorter messages. Presenting more arguments can be more persuasive even if the arguments themselves are not compelling [ 40 ]. Longer messages likely provided more opportunities for the OP to engage with material that could potentially change their mind, thus increasing the likelihood of persuasion.

Although more readable content is easier to understand and less aversive than less readable content [ 41 ], greater reading difficulty and comprehension can engender more interest, attention, and engagement [ 42 , 43 ]. It can also facilitate deeper cognitive processing that leads to greater learning and long-term retention [ 44 , 45 ]. This is especially true for individuals intrinsically motivated or capable of engaging in complex and novel tasks [ 46 ]. OPs were likely capable of and intrinsically motivated to engage in content that challenged their beliefs considering they were inviting others to debate them. The interpretation of users being intrinsically motivated to challenge their beliefs is also in line with the link that emerged between greater usage of analytical language and persuasion. Similarly, messages that focused less on one’s own personal experiences may have provided more objective evidence to support a particular argument, facilitating persuasion.

Last, while greater lexical repetitions may be perceived as less interesting [ 31 , 47 ], it facilitated persuasion in this context. Lexical repetitions provide effective ways for speakers to communicate complex topics as it keeps “lexical strings relatively simple, while complex lexical relations are constructed around them” [ 48 ]. Lexical repetitions are advantageous for navigating through the order and logic of an argument, providing “textual markers” that help readers connect important aspects of an argument together [ 49 ]. Lower lexical diversity, then, appeared to be beneficial for building arguments that are more cohesive, more coherent, and thus, more persuasive.

Altogether, our findings reveal that the linguistic features linked to persuasion fall along three dimensions pertaining to structural complexity, negative emotionality, and positive emotionality. Our findings also highlight the importance of linguistic features related to a message’s structural complexity, particularly the verbal behaviors that provide a greater amount of factual evidence in a way that enables readers to connect important aspects of the information in an appropriately stimulating manner. Although the other linguistic features that were examined in this study may contribute to message persuasiveness to some degree, our results indicate that they are relatively less important after word count, lexical diversity, reading difficulty, analytical thinking, and self-references are taken into account. These findings also seem to reflect r/ChangeMyView’s digital environment. A central feature of r/ChangeMyView is ensuring that all posts and replies meaningfully contribute to the conversations. As such, OPs and repliers must adhere to all moderator-enforced policies of interaction. In addition, users who post on r/ChangeMyView are likely individuals who are open to attitude change given that they are publicly inviting others to debate them on a topic they already have an opinion on. This suggests that, in digital environments that underscore meaningful contributions to conversations, the ability to convey more objective information while fostering engagement and a holistic understanding of an argument are most vital to the alteration of established attitudes among open-minded individuals.

Our findings also have implications for the process by which persuasion research via language is conducted. Assessing the relative importance of a linguistic feature on message persuasiveness allowed us to understand its interconnections with other linguistic features and its link to persuasion, yielding a more comprehensive and well-rounded understanding of the feature’s role in message persuasiveness. Consider word count , for example: without assessing word count’s relative importance on message persuasiveness in the current study, we would not have been able to ascertain its link to message persuasiveness via a message’s structural complexity and the importance of providing more content in a way that enables readers to connect important aspects of the information in an appropriately stimulating manner. Because the meaning of a word or linguistic feature in any text is dependent on the context by which it is used, understanding the social psychological pathways to persuasion via language requires researchers to account for the presence of multiple linguistic features within a given message when assessing a linguistic feature’s link to message persuasiveness. This holistic approach may also help reconcile conflicting results from previous research on language and persuasion.

Our findings also inform theories, such as ELM, that address how linguistic features influence persuasion and provide a more precise understanding of the social psychological pathways to persuasion. For example, ELM states that here are two main routes to persuasion: the central route, which focuses on the message quality on persuasion, and the peripheral route, which uses heuristics and peripheral cues to help influence individual decisions regarding a topic [ 6 ]. Individuals are more likely persuaded via the central route if they have the ability and motivation to process the information. On the other hand, individuals are more likely persuaded via the peripheral route if involvement is low and information processing capability is diminished. OPs likely have the ability and motivation to process arguments from repliers and are thus likely persuaded via the central route given that they are publicly inviting others to debate them. Supplying more information to support a conclusion may be more likely to persuade via the central route, but this information also needs to be organized in a way that helps readers connect important aspects of the information together. A wealth of information that is structured in an incoherent manner would undoubtedly hinder comprehension, and thus, persuasion.

Strengths and limitations

Our dataset contained a large sample of replies that spanned a wide variety of topics, and provided high ecological validity given that it captured the process of persuasion as it occurred naturally without elicitation. The enforcement of rules on r/ChangeMyView yielded interactions that were conducted under similar conditions and expectations. This helped to minimize interaction variance without interfering with the naturalistic nature of the data. However, OPs can award deltas to responses within subtrees (the “children” of direct replies) typically as the result of “back-and-forth” interactions with repliers. These were not included in the current study as we only examined top-level responses. Our results could also differ by topic, recency of the post, and post length, and it is possible non-linguistic features such as the popularity of a post, the number of “upvotes” (i.e., the number of instances other users have registered agreement with a particular post or reply) a reply receives, and the number of deltas a replier has ever received may also impact message persuasiveness. Future studies should determine if these variables moderate the findings, and doing so would also address the relative importance of linguistic versus non-linguistic features on message persuasiveness.

Although it is a policy on r/ChangeMyView that OPs must post a non-neutral opinion (i.e., their post must take a non-neutral stance on a topic), and posts that violate this rule are removed by moderators, it is possible that an OP’s post did not accurately reflect their true attitude or attitude strength. Given the nature of the data, this study cannot address whether the resulting attitude changes were long-lasting, nor if the OP’s attitude strength moderated their attitude change. Longitudinal studies can assess these points. Because there were substantially more non-persuasive replies (99.39%) than persuasive ones, we constructed a balanced subsample and conducted our analyses on this balanced subsample. While this strategy limited biased outcomes stemming from a large class imbalance, it also limits the generalizability of results to posts in which no persuasion occurred. Further examinations of the class imbalance are needed to address this issue. For example, it is possible that posts in which no persuasion occurred are systematically different from posts in which persuasion occurred. Or, perhaps the class imbalance simply reflects the rigid nature of attitudes. In addition, our results may only reflect a particular population given that Reddit users tend to skew younger and male [ 50 ]. Since we did not have access to subjects’ demographic information, we cannot assert the representativeness of our sample. Future research should investigate persuasion that takes place on other debate-style forums and websites to incorporate more diverse subjects, interaction modes, and digital environments.

Acknowledgements

We thank Haley Bader, Carolynn Boatfield, Maria Civitello, Katie Kauth, and Xinyu Wang for their assistance in data cleaning, Arthur Bousquet and Leonardo Carrico for their assistance in data analysis, and David Johnson for his helpful feedback on earlier drafts of this paper. Preparation of this manuscript was funded, in part, by grants from the Swiss National Science Foundation (#196255) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (15F06718R0006603). The views, opinions, and findings contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be construed as position, policy, or decision of the aforementioned agencies, unless so designated by other documents.

Author contributions

VT developed the concept of the study, conducted data analysis, and wrote the manuscript. RL Boyd collected the data, assisted with study development, natural language and statistical analyses and provided critical revisions. SS assisted with data preparation and analyses and provided critical revisions. AK, CG, AL, and LM assisted with data cleaning and literature review.

Not applicable.

Declarations

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

https://osf.io/4rj26/?view_only=5556b511084b4e75bc14808e47d15dce .

Approval granted by Lancaster University’s ethics committee (Reference #FST19067).

Not applicable; data was non-identifiable and publicly available.

1 We define linguistic feature as a characteristic used to classify a word or corpus of text based on their linguistic properties. Examples include reading difficulty, words denoting high or low emotionality, hedges, etc.

2 For all of r/ChangeMyView’s policies, visit https://www.reddit.com/r/changemyview/wiki/rules#wiki_rule_a .

3 Supplementary materials can be found here: https://osf.io/4rj26/?view_only=5556b511084b4e75bc14808e47d15dce

4 We adopted the Valence-Arousal-Dominance circumplex model of emotion (Bradley & Lang, 1994; Russell, 1980) and the PAD emotion state model (Mehrabian, 1980; Bales, 2001) and conceptualize valence, arousal, and dominance as the dimensions of emotion. All three dimensions have been linked to message persuasiveness (see Table Table1 1 ).

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

- Research Papers

How to Write an Argumentative Research Paper

Last Updated: December 9, 2022 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Christopher Taylor, PhD . Christopher Taylor is an Adjunct Assistant Professor of English at Austin Community College in Texas. He received his PhD in English Literature and Medieval Studies from the University of Texas at Austin in 2014. There are 14 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 369,201 times.

An argumentative essay requires you to make an argument about something and support your point of view using evidence in the form of primary and secondary sources. The argumentative essay is a common assignment, but teachers may present it in a variety of different ways. You can learn how to write an argumentative essay by following some standard steps for writing an essay as well as by doing some things that are required for argumentative essays, such as citing your sources.

Sample Outlines

Getting Started

- a thesis statement that makes a clear argument (provided in the first paragraph)

- claims that help prove your overall argument

- logical transitions that connect paragraphs and sentences

- support for your claims from your sources

- a conclusion that considers the evidence you have presented

- in-text citations throughout your essay to indicate where you have used sources (ask your teacher about what citation style to use)

- a works cited page with an entry for each of your sources (ask your teacher about what citation style to use)

- Make sure that you understand how to cite your sources for the paper and how to use the documentation style your teacher prefers. If you’re not sure, just ask.

- Don’t feel bad if you have questions. It is better to ask and make sure that you understand than to do the assignment wrong and get a bad grade.

- Listing List all of the ideas that you have for your essay (good or bad) and then look over the list you have made and group similar ideas together. Expand those lists by adding more ideas or by using another prewriting activity. [3] X Research source

- Freewriting Write nonstop for about 10 minutes. Write whatever comes to mind and don’t edit yourself. When you are done, review what you have written and highlight or underline the most useful information. Repeat the freewriting exercise using the passages you underlined as a starting point. You can repeat this exercise multiple times to continue to refine and develop your ideas. [4] X Research source

- Clustering Write a brief explanation (phrase or short sentence) of the subject of your argumentative essay on the center of a piece of paper and circle it. Then draw three or more lines extending from the circle. Write a corresponding idea at the end of each of these lines. Continue developing your cluster until you have explored as many connections as you can. [5] X Research source

- Questioning On a piece of paper, write out “Who? What? When? Where? Why? How?” Space the questions about two or three lines apart on the paper so that you can write your answers on these lines. Respond to each question in as much detail as you can. [6] X Research source

- Ethos refers to a writer’s credibility or trustworthiness. To convince your readers that your argument is valid, you need to convince them that you are trustworthy. You can accomplish this goal by presenting yourself as confident, fair, and approachable. You can achieve these objectives by avoiding wishy-washy statements, presenting information in an unbiased manner, and identifying common ground between yourself and your readers(including the ones that may disagree with you). You can also show your authority, another aspect of ethos, by demonstrating that you’ve done thorough research on the topic.