364 Education Research Topics about School Issues, Special Education, and More

The field of education encompasses diverse areas of study, ranging from elementary school to higher education. It includes curriculum development, teaching policy-making, and the application of psychology and technology in learning.

Education research explores learning theories and effective teaching practices, examines the impact of sociocultural elements on teaching, and addresses concerns of equality and inclusion. This dynamic discipline continually evolves, driven by innovations and the desire to enhance learning outcomes for all students while creating new avenues for fundamental research.

In this article, you’ll find many education research topics for your projects. You can also find additional ideas in our free essay database .

🏫 15 Controversial School Topics

🔎 research areas & topics in education, 🎒 elementary education research topics, 👩🎓 adult education research topics, 🧮 action research topics in education, 🔕 special education research topics, 🚌 school issues topics, 📒 more controversial school topics, 🧠 school psychology research topics, 🔗 references.

- The role of school counselors’ support for students considering abortion.

- Psychedelic therapy: The impact on students’ mental health.

- The role of school religion classes in promoting cultural understanding.

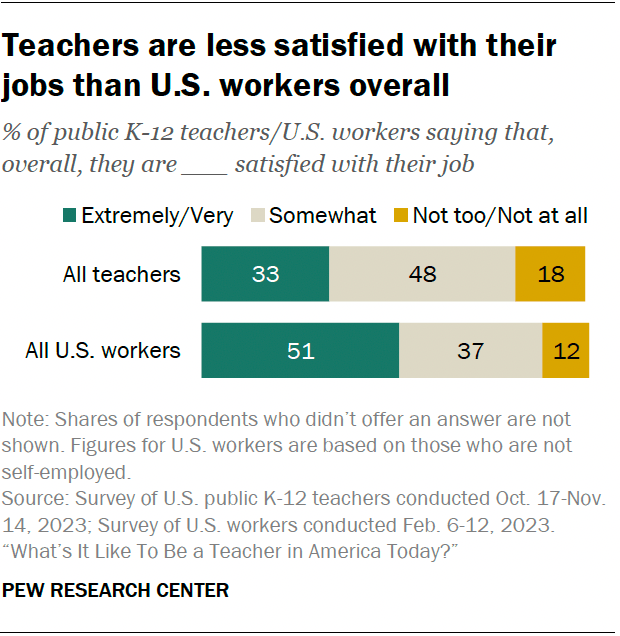

- How do economic policies impact teacher retention and job satisfaction?

- Sexual harassment in schools: Prevalence, structure, and perceptions.

- Free education and its role in reducing educational inequality.

- Why is parental support crucial in achieving academic success?

- Bullying and cyberbullying: The influence on the school environment.

- The effectiveness of school-based sex education programs.

- Promoting school safety for LGBTQ students.

- Inclusive curriculum as a path to better educational performance.

- Cultural diversity in secondary school classrooms.

- The link between alcohol consumption and educational performance.

- Gambling behavior and risk factors in preadolescent students.

- Final exams as the main reason for student depression and anxiety.

Research in education seeks to improve learning outcomes, address the issues of equity and inclusion , and integrate innovative technology into the educational process. Look at the table below to learn what different research areas in education deal with!

- The influence of modern technologies on elementary school education.

- Elementary education: Methods and strategies.

- Elementary School: Picture Communication at the Lesson .

- Promotion of the healthy diet program in elementary schools.

- The role of physical education in elementary schools.

- Addressing Bullying in Elementary and Middle School Classrooms .

- Social studies in the elementary school.

- How to increase motivation among students in elementary school?

- Math Methodology for Elementary Teachers .

- The value of community and family involvement in elementary schools.

- Dominant learning styles among elementary school students.

- Teacher Efficacy of Pre-service Elementary Teachers .

- Elementary education principles: Europe vs. the US.

- The problem of bullying among elementary school students.

- Departmentalization in American Elementary Schools .

- The impact of laptops on elementary school students’ performance.

- The history of elementary education development in Europe.

- Yorktown Elementary School Improvement Plan .

- Corporal punishment as a way of dealing with elementary-level aggressive children.

- Pedagogical Skills in Elementary School .

- Effects of obesity on elementary school students’ development.

- Elementary-level art education and its importance.

- Students’ Academic Performance: Elementary Homework Policies .

- The standards of learning at the elementary educational level.

- Modern approaches to self-studying in elementary school.

- Task-Based Language Teaching Applied in Elementary Classroom .

- Learning English in bilingual elementary schools.

- Lack of proper grooming as a cause of violence among elementary students.

- Proposal for Providing Healthier Food Choices for Elementary Students .

- The need for sexual education in elementary school.

- Differences between adult and child education.

- Main types of adult education and their features.

- Adult Education: Reasons to Continue Studying .

- The most popular adult education agencies and institutions in Europe.

- Adult education: Purpose and theories.

- Adult Education in the “Real World” Classroom .

- Challenges and motivating factors in education for adults.

- Greater social inclusion as one of the crucial benefits of adult education.

- Adult Education for Canadian Immigrants .

- Adult-education movements in the UK.

- What sets adult education apart from traditional education?

- Interaction Strategies in Adult Education .

- Albert Mansbridge and his role in adult education development.

- Adult education in Canada: Key features.

- Adult Educational Pedagogical Philosophies, Theories .

- Peculiarities of learning environment for adult students.

- Critical resources for adult education and training.

- Importance of Adult Education: Risks and Rewards .

- Adult education as a tool for developing leadership capabilities.

- The role of critical thinking in adult education.

- Adult Education: McClusky’s Power-Load-Margin .

- What theories of adult learning are used in UK education?

- Modern technology and its impact on adult learning improvement.

- Michael Collins “Adult Education as Vocation”: Theoretical Positions .

- Theories of adult learning in the context of clinical teaching nurses.

- Adult education: Opportunities and limitations.

- Concept of Lifelong Learning .

- The aid of volunteers in adult education.

- Teaching skills that play a vital role in adult education.

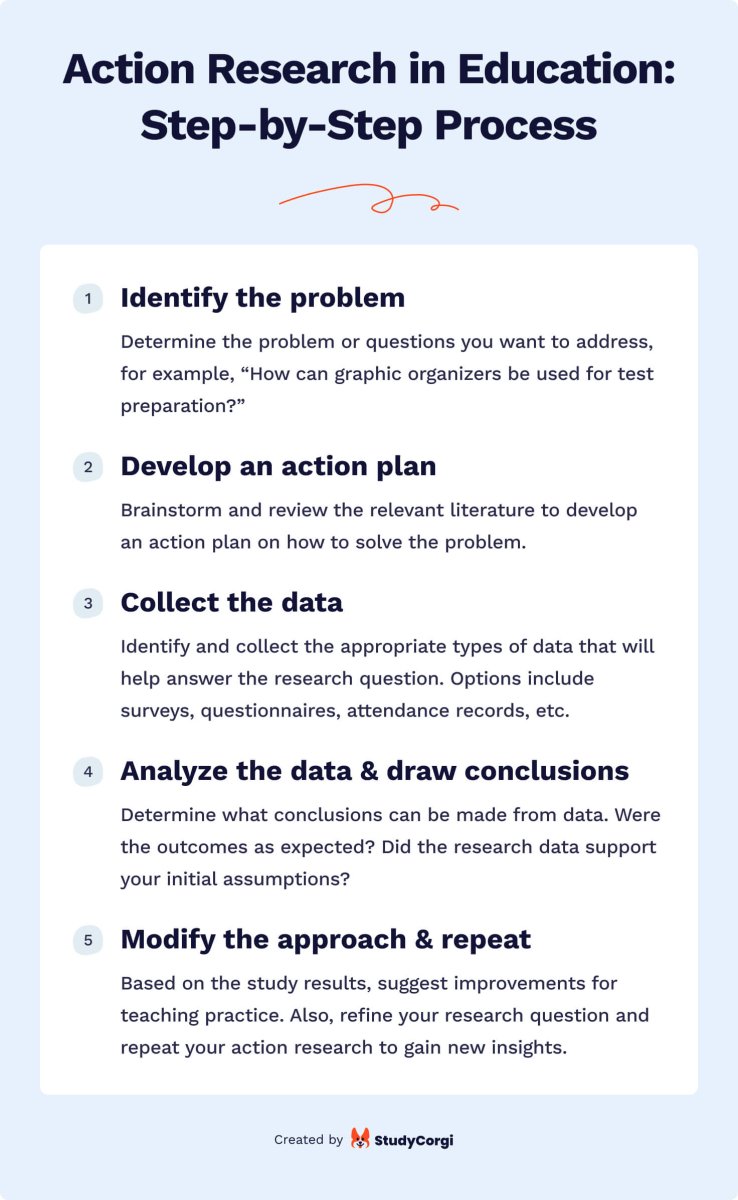

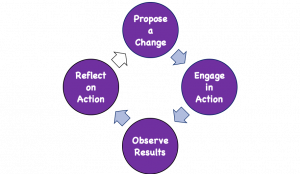

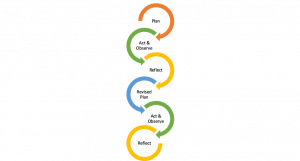

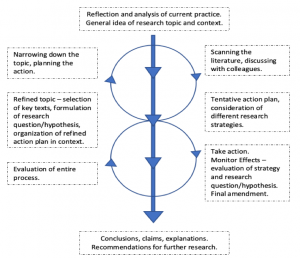

Action research seeks to identify problems, weaknesses, or areas for improvement in different dimensions of the education system — instructional, academic, or organizational. It is a cyclical process, the goal of which is to equip teachers with a mechanism for problem resolution in schools to enhance student learning and teacher effectiveness.

- William Barry: A theory-based educational approach to action research.

- The Effects of Cyberbullying on Students’ Academic Performance .

- Educators’ challenges in conducting action research in classrooms.

- Action research’s importance in teacher education courses.

- Inclusion Policies in Education and Their Effects .

- Primary school education: Action research plan.

- The benefits of using action research in the classroom.

- Learning Disabilities and Intervention Methods .

- The role of action research in college education.

- Parental involvement in student’s education with the help of action research.

- Online Learning and Students’ Mental Health .

- The influence of action research on curriculum development.

- Action research in education: Characteristics and working principles.

- How Is Social Media Affecting College Students?

- Why is action research one of the best ways to improve academic performance?

- Action research for educational reform: Remodeling action research theories.

- College Students’ Weight Gain and Its Causes .

- The use of action research in higher education and its outcomes.

- International educational perspectives through action research.

- Inclusion and Individual Differences in Classroom .

- The contribution of action research to investigating classroom practice.

- How does action research support the development of inclusive classroom environments?

- Homeschooling: Argumentation For and Against .

School & Classroom Management

- Peculiarities of educational management in primary and elementary schools.

- Classroom Management and Techniques to Incorporate in Student’s Reinforcement Plan .

- Preventive approaches to classroom management.

- Educational management: The blue vs. orange card theory.

- Teaching Strategies and Classroom Management .

- What is the role of corporal punishment in educational management?

- Classroom management system: Effective classroom rules.

- Dominance and Cooperation as Classroom Management Strategies .

- Culturally responsive classroom management: Definition and features.

- The influence of school management on student well-being and engagement.

- Blended Learning and Flipped Classrooms .

- Use of information communication technology in school management.

- The problems of classroom management with high school students.

- The Role of Computers in the Classroom .

- Assessment of the role of teachers in school management.

- Online vs. Traditional Classroom Education .

Educational Policies

- Why are education policies and strategies crucial for teachers and students?

- The effectiveness of implementing educational policies.

- Implementation of Federal Educational Policies .

- State policies to increase teacher retention.

- Policies and laws promoting gender equality in education.

- The Separate But Equal Education and Racial Segregation .

- Education policy issues in 2020: Consequences of Covid-19.

- Educational policies for students with disabilities.

- Higher Education Should Be Free for Everyone .

- What education policies and practices does UNESCO prioritize?

- Education policies as a way to improve the school system in the Philippines.

- Where and How Sex Education Should Be Conducted Among the Young People?

- The education policy fellowship program and its value and goal.

- Should Schools Distribute Condoms?

- European education policy regarding the education of adults.

- The main features of the special education process.

- Use of assistive technology in improving education for students with special needs.

- Special Education in New York City .

- Special education: Transforming America’s classrooms.

- The issues faced by parents of students with disabilities.

- Functional Curriculum Goals in Special Education .

- The role of social skills training in the development of special education.

- Paraeducators: Assisting students with special needs in their studies.

- Labeling in Special Education .

- Physical class as a vital part of special education.

- Effects of co-teaching approaches on the academic performance of students with disabilities.

- English Language Learning in Special Education .

- Behavioral strategies for dealing with autism spectrum conditions during lessons.

- Natural Readers Website as Assistive Technology in Education .

- Trauma-informed teaching as a trending issue in special education.

- Special education: The main concepts and legal background.

- Learning Disabilities: Speech and Language Disorders .

- Use of cultural resonance in special education.

- Current issues in special education for children with disabilities.

- Related Services for Students with Disabilities .

- The special education profession and its value.

- Special education: Teaching children with mental disorders.

- Exclusion of Students with Learning Disabilities .

- How to create a perfect curriculum for students with special needs?

- The importance of collaboration between parents and special education teachers.

- General Curriculum for Students with Severe Disabilities .

- The Netherlands as a leader in supporting intellectual disabilities programs.

- Effective Strategies for Students With Learning Disabilities

- The role of cultural sensitivity in multicultural special education.

- Special education: The main aspects and conflicts.

- New Technologies for the Students with Disabilities .

- The frequency and consequences of firearm-related incidents in schools.

- Gun Control and School Shootings .

- The impact of political ideology on educational policies and practices.

- Why is sexual assault a serious problem on American campuses?

- Negative Impact of Media Attention to School Shooting .

- Regulations and procedures for preventing unauthorized access to weapons in schools.

- College accreditation and student loan forgiveness.

- Discrimination in School and Its Effects on Students .

- Modern technologies as a real threat to student privacy and security.

- The issue with learning accommodation for non-traditional students.

- Discrimination and Inequality in the Education System

- Why is standardized testing one of the biggest problems in education?

- The prevalence and patterns of alcohol consumption among students.

- The Early Education Issues: Development and Importance .

- Student poverty and its connection to academic performance and success.

- Teacher salaries: A critical education issue of the 21st century.

- School Bullying and Legal Responsibility .

- What effect does the size of the class have on student outcomes?

- School violence: Dealing with it and minimizing the danger.

- Adolescent Mental Health: Depression .

- Analyzing the impact of technology integration on the increased level of cheating.

- Teacher burnout and its impact on student achievement.

- Adolescent Drug Abuse, Their Awareness, and Prevention .

- What is the influence of socioeconomic status on educational achievement gaps?

- Social Inequality at School .

- High-stakes testing as the main reason for increasing student stress levels.

- Homework: The main disadvantages of self-studying at home.

- Social Inequality and Juvenile Delinquency .

- The effects of drug education campaigns on student knowledge and attitudes.

- Why do college students often become addicted to gambling?

School Bullying

- A method to prevent bias and discrimination in the school system.

- Cyberbullying Among University Students .

- The social consequences of cyberbullying and cyberstalking for students.

- What is the influence of bullying on the academic performance of students?

- School Bullying and Problems in Adult Life .

- Bullying and suicide: Understanding the link and dealing with it.

- School Bullying: Causes and Effects .

- The issue of bullying of children with special needs in school.

- The impact of bullying on school communities.

- Prevention of Bullying in Schools .

- What effect does bullying have on high school-aged students?

- Parenting Style and Bullying Among Children .

- School bullying: Government strategies for managing the problem.

- What steps can parents take to stop bullying at school?

- Cyberbullying of Children in Canada .

- The importance of the anti-bullying program for schools.

- The contribution of technology to the occurrence or prevention of bullying.

- Student Dropouts in Bully-Friendly Schools .

- Bullying and its influence on school climate.

- Bullying and violence in schools: Social psychology perspective.

- The Long-Term Consequences of Being Bullied or Bullying Others in Childhood .

- What are the leading causes of bullying in school?

- Investigating the consequences of online bullying among school-aged children.

- Bullying of Learners with Disabilities .

Lack of Funding

- The impact of school funding issues on the performance of students.

- Children Education. Federal Funding of Preschool .

- School funding issues: Methods and strategies to overcome the problem.

- Why is school funding a key to equitable education?

- The Role of External Funding in Academic Projects .

- The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on school funding.

- How can an increase in spending on education help boost economic recovery?

- School-Funding System in New Jersey .

- Investigating the link between financial disparities and educational inequality.

- How Misuse of Funding Could Affect Education .

- The influence of budget cuts on teacher recruitment and retention.

- Inadequate funding as one of the biggest problems in education.

- Free College Education: Arguments in Support .

- Problems of insufficient funding for elementary education in Asia.

- The role of private sector partnerships in education funding.

- Should College Education Be Free for All US Citizens?

- Public education funding in the US: Peculiarities.

- The importance of educating children in poor countries.

- Should College Athletes Be Paid or Not?

- How can the issue of improper funding for schools be solved?

- New school funding model in Kenya: Benefits and main problems.

- Evidence-Based Model and Solving Problems with School Funding .

- How do decreasing budgets affect student learning and achievement?

Mental Health of Students

- Why do many college students experience symptoms of severe mental health conditions?

- University Students’ Mental Health in 2000-2020 .

- Depression as a common mental health issue in US students.

- Suicidal ideation and intent in students: The leading causes and symptoms.

- The Effect of Mental Health Programs on Students Academic Performance .

- American Psychological Association and its role in helping students with anxiety.

- Eating disorders: The female college students’ problem.

- Mental Health Issues in College Students .

- Substance misuse and its influence on the social life of students.

- What are the long-term effects of academic stress on student mental health?

- Strategies to Decrease Nursing Student Anxiety .

- Factors contributing to the rise in student anxiety and depression rates.

- Social media use and its connection to the mental health of high school students.

- Adolescent Depression: Modern Issues and Resources .

- Sleep quality and duration’s influence on student mental health.

- How does parental involvement influence the mental health and well-being of students?

- The Problem of Adolescent Suicide .

- Physical activity and its contribution to students’ mental health.

- The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on student mental health.

- Mental Health Well-Being Notion: Its Effect on Education .

- The effectiveness of school-based mental health programs for students in Europe.

- Education and Motivation for At-Risk Students .

- Creative approaches to support teenagers with mental disorders.

Inclusivity

- The value of inclusive education for high school students.

- Diversity and Inclusivity as Teaching Philosophy .

- Government measures to advance inclusive education.

- Inclusive education: Essential elements, related laws, and strategies.

- Inclusive Education for Students With Autism Spectrum Disorder .

- Inclusive teaching principles at Columbia schools.

- How do open society foundations support inclusive education?

- Student-Teacher Interaction in Inclusive Education .

- Inclusive education and its benefits for students with disabilities.

- Non-competitive learning as the main concept of inclusive education.

- Inclusive Education for Students With Disabilities .

- Increasing inclusivity in the classroom: The main benefits and methods.

- How can parents build an inclusive behavioral model for their children in elementary school?

- Effective Practice in Inclusive and Special Needs Education .

- The role of government in funding inclusive education in the US.

- Respectful language as a key to teaching students to be more tolerant.

- Early Childhood: Inclusive Programs and Social Interactions .

- Diverse groups and their contribution to increasing inclusivity in the classroom.

- The value of inclusive education: Socialization and academic progress.

- Creating Inclusive Classrooms for Diverse Learners .

- Peculiarities of curriculum and pedagogy in inclusive education.

- What are the critical challenges in implementing inclusive education policies?

Other School Issues

- Traditional teaching methods and their negative impact on student performance.

- Shooting in Schools: Trends and Definition .

- The main teaching issues: Constant pressure and a lot of paperwork.

- The lack of effective communication between teachers and students in high school.

- Alcohol Abuse Among Students: Reforming College Drinking .

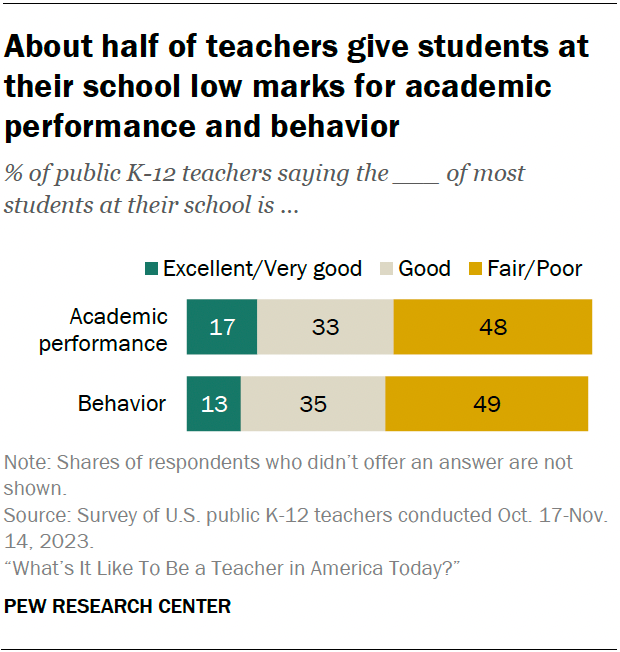

- Students’ behavior as one of the relevant issues in elementary school.

- The risk of burning out in college students: Causes and symptoms.

- Dormitory Life and Its Tough Sides for Students .

- How does a lack of support outside of the classroom influence students’ grades?

- The connection between administrative workload and teacher retention rates.

- Changes in Diet and Lifestyle for Students .

- Changing educational trends as one of the challenges faced by teachers.

- What are the main limitations of disciplining students?

- Homeschooling Disadvantages for Students and Parents .

- The issue of using mobile devices in the classroom.

- The potential drawbacks and limitations of redundant teaching techniques.

- Dealing With Procrastination Among Students .

- How to deal with the growing discipline problem in US classrooms?

- The effects of educational technology use on college student learning.

- Teaching Students With Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder .

- The emotional and mental toll of lesson planning on teachers.

- What is the impact of pressure from school administrators on teacher performance?

- Cybersecurity Threats for Students & How to Fight Them .

- The community perceptions and concerns regarding armed guards in schools.

- Small-Group Counseling for the High-School Students .

- The need for bilingual education for students in England.

- LGBT+ inclusive sex education: Advantages and disadvantages.

- Challenges Faced by Foreign Students in Adapting to University Culture .

- Why should school uniforms in middle and high school be mandatory?

- The influence of teaching salaries on teacher motivation and performance.

- The Problem of Technology Addiction Among College Students .

- The role of teachers in navigating religious diversity in classrooms.

- What makes private schools in the US better than public ones?

- Why Some Students Cheat .

- The impact of free colleges on the quality of higher education.

- Dissection in school: The value and impact on student’s attitudes toward science.

- How Inclusive Learning Affects Other Students .

- The social and emotional development of students in homeschooling and traditional schooling.

- Why is it necessary to implement college courses in state prisons?

- How to Keep Young Students Engaged and Disciplined in Classroom .

- The effectiveness of school-supplied condoms in preventing teenage pregnancy.

- The impact of implicit bias on racial segregation in education.

- The Problem of Anxiety Among the College Students .

- Race-based school discipline in high school: For and against.

- What are the cons and pros of single-sex schools?

- The Need for Curriculum Change Among African American Students .

- Corporal punishment in schools as a way of controlling undisciplined behavior.

- The role of online education in student-teacher interaction.

- Self-Esteem and Self-Anxiety in Nursing Students .

- The problem of sexually or socially provocative clothes at school and methods of solving it.

- Behavioral Intervention Plan (BIP) For Anxious Students .

- Corruption and emotional manipulations in the educational system.

- How can social and religious issues uniquely affect education?

- Mandatory Drug Tests for Nursing Students .

- What are the main aspects and goals of school psychology?

- Adlerian Theory for School Counseling .

- Historical foundations of American school psychology.

- The role of school psychologists in conceptualizing children’s development.

- Solution-Focused Brief Therapy in School Counseling .

- School psychology: The helping hand in overcoming school crisis.

- The value of professional development programs in high school.

- Therapy Modality for Transformational P-12 School Counselors .

- Job prospects in school psychology in the United States.

- What is the role of school psychologists in supporting students with special needs?

- The McMartin Preschool and Forensic Psychology .

- School psychology in the 21st century: Foundations and practices.

- How do the social-emotional learning programs impact student well-being?

- The effects of school-based crisis interventions on students’ post-traumatic recovery.

- Cognitive Distortions in Middle-School Students.

- School psychology science: Skills and procedures.

- What are the most effective psychological strategies for reducing bullying in schools?

- Instruction Development for Students with Cognitive Disability .

- The effects of crisis intervention work on school psychologists.

- National Association of School Psychologists: Standards and practices.

- The influence of psychologists on the formulation of school policies in the UK.

- Risky Sexual Behaviors Among College Students .

- Counseling students with a sexual abuse history and its impact on academic success.

- Religion and spirituality as diverse topics in school psychology publications.

- Social-Behavioral Skills of Elementary Students with Physical Disabilities .

- School-based considerations for supporting American youths’ mental health.

- The practices for increasing cross-cultural competency in school.

- Classroom Management Ideas: Behavioral Crises and Promotion of Friendship Between Students .

- School psychologists: Principles of professional ethics .

Educational research advances knowledge across diverse disciplines, employing scientific methods to address real-world challenges within the realm of education. By exploring various topics , from innovative pedagogies to the impact of technology, we gain valuable insights to enhance educational practices, ensure inclusivity, and empower future generations with the tools for success.

❓ Educational Research Topics FAQ

What are good research topics for education.

An effective topic is one you can explore in-depth within the length of your assignment. Here are some crucial characteristics of a good research topic:

- Relevant and clear.

- Not too broad or narrow.

- Interesting for the author and target audience.

For example:

- Project-based learning in the classroom: Pros and cons.

- What role did technology play in the development of online tutoring?

How do I find a research topic in education?

You should take 3 simple steps to find a research topic in education:

- Determine the area in education that interests you the most.

- Read all the relevant information to understand the hot issues in your field.

- If you still cannot find the one that suits you best, use our base of the most exciting research topics in education!

What are the top 5 most researched topics?

- Bullying and cyberbullying as significant issues in US schools.

- Why are modern technologies more of a distraction than a helper in education?

- The benefits of inclusive classrooms for students with disabilities.

- How did COVID-19 affect student mental health and the school environment?

- The barriers to education access in underserved communities.

- 10 Challenges Facing Public Education Today | National Education Association

- Education Issues, Explained | EducationWeek

- The Education Crisis: Being in School Is Not the Same as Learning | The World Bank

- The 10 Most Significant Education Studies of 2021 | Edutopia

- Special Education Topics | Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction

- Social Issues That Special Education Teachers Face | Chron

- How Teachers Can Learn Through Action Research | Edutopia

- School Psychology | American Psychological Association

- Issues and Problems in Education | Sociology by University of Minnesota

- Educational Research Design | University of Pittsburgh

- Global Education Issues: Making a Difference Through Policy | American University

- Unequal Opportunity: Race and Education | Brookings

- Higher Education | George Mason University

- Department of Curriculum and Instruction: Research Topics | University of Minnesota

- A Six Step Process to Developing an Educational Research Plan | East Carolina University

- Teaching and Learning Topics | University of Oregon

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter X

- Share to LinkedIn

You might also like

How to start a business as a student – a step-by-step guide, 4000 word essay writing guide: how to structure & how many pages is it, greek life 101: fraternities and sororities explained.

Research Topics & Ideas: Education

170+ Research Ideas To Fast-Track Your Project

If you’re just starting out exploring education-related topics for your dissertation, thesis or research project, you’ve come to the right place. In this post, we’ll help kickstart your research topic ideation process by providing a hearty list of research topics and ideas , including examples from actual dissertations and theses..

PS – This is just the start…

We know it’s exciting to run through a list of research topics, but please keep in mind that this list is just a starting point . To develop a suitable education-related research topic, you’ll need to identify a clear and convincing research gap , and a viable plan of action to fill that gap.

If this sounds foreign to you, check out our free research topic webinar that explores how to find and refine a high-quality research topic, from scratch. Alternatively, if you’d like hands-on help, consider our 1-on-1 coaching service .

Overview: Education Research Topics

- How to find a research topic (video)

- List of 50+ education-related research topics/ideas

- List of 120+ level-specific research topics

- Examples of actual dissertation topics in education

- Tips to fast-track your topic ideation (video)

- Free Webinar : Topic Ideation 101

- Where to get extra help

Education-Related Research Topics & Ideas

Below you’ll find a list of education-related research topics and idea kickstarters. These are fairly broad and flexible to various contexts, so keep in mind that you will need to refine them a little. Nevertheless, they should inspire some ideas for your project.

- The impact of school funding on student achievement

- The effects of social and emotional learning on student well-being

- The effects of parental involvement on student behaviour

- The impact of teacher training on student learning

- The impact of classroom design on student learning

- The impact of poverty on education

- The use of student data to inform instruction

- The role of parental involvement in education

- The effects of mindfulness practices in the classroom

- The use of technology in the classroom

- The role of critical thinking in education

- The use of formative and summative assessments in the classroom

- The use of differentiated instruction in the classroom

- The use of gamification in education

- The effects of teacher burnout on student learning

- The impact of school leadership on student achievement

- The effects of teacher diversity on student outcomes

- The role of teacher collaboration in improving student outcomes

- The implementation of blended and online learning

- The effects of teacher accountability on student achievement

- The effects of standardized testing on student learning

- The effects of classroom management on student behaviour

- The effects of school culture on student achievement

- The use of student-centred learning in the classroom

- The impact of teacher-student relationships on student outcomes

- The achievement gap in minority and low-income students

- The use of culturally responsive teaching in the classroom

- The impact of teacher professional development on student learning

- The use of project-based learning in the classroom

- The effects of teacher expectations on student achievement

- The use of adaptive learning technology in the classroom

- The impact of teacher turnover on student learning

- The effects of teacher recruitment and retention on student learning

- The impact of early childhood education on later academic success

- The impact of parental involvement on student engagement

- The use of positive reinforcement in education

- The impact of school climate on student engagement

- The role of STEM education in preparing students for the workforce

- The effects of school choice on student achievement

- The use of technology in the form of online tutoring

Level-Specific Research Topics

Looking for research topics for a specific level of education? We’ve got you covered. Below you can find research topic ideas for primary, secondary and tertiary-level education contexts. Click the relevant level to view the respective list.

Research Topics: Pick An Education Level

Primary education.

- Investigating the effects of peer tutoring on academic achievement in primary school

- Exploring the benefits of mindfulness practices in primary school classrooms

- Examining the effects of different teaching strategies on primary school students’ problem-solving skills

- The use of storytelling as a teaching strategy in primary school literacy instruction

- The role of cultural diversity in promoting tolerance and understanding in primary schools

- The impact of character education programs on moral development in primary school students

- Investigating the use of technology in enhancing primary school mathematics education

- The impact of inclusive curriculum on promoting equity and diversity in primary schools

- The impact of outdoor education programs on environmental awareness in primary school students

- The influence of school climate on student motivation and engagement in primary schools

- Investigating the effects of early literacy interventions on reading comprehension in primary school students

- The impact of parental involvement in school decision-making processes on student achievement in primary schools

- Exploring the benefits of inclusive education for students with special needs in primary schools

- Investigating the effects of teacher-student feedback on academic motivation in primary schools

- The role of technology in developing digital literacy skills in primary school students

- Effective strategies for fostering a growth mindset in primary school students

- Investigating the role of parental support in reducing academic stress in primary school children

- The role of arts education in fostering creativity and self-expression in primary school students

- Examining the effects of early childhood education programs on primary school readiness

- Examining the effects of homework on primary school students’ academic performance

- The role of formative assessment in improving learning outcomes in primary school classrooms

- The impact of teacher-student relationships on academic outcomes in primary school

- Investigating the effects of classroom environment on student behavior and learning outcomes in primary schools

- Investigating the role of creativity and imagination in primary school curriculum

- The impact of nutrition and healthy eating programs on academic performance in primary schools

- The impact of social-emotional learning programs on primary school students’ well-being and academic performance

- The role of parental involvement in academic achievement of primary school children

- Examining the effects of classroom management strategies on student behavior in primary school

- The role of school leadership in creating a positive school climate Exploring the benefits of bilingual education in primary schools

- The effectiveness of project-based learning in developing critical thinking skills in primary school students

- The role of inquiry-based learning in fostering curiosity and critical thinking in primary school students

- The effects of class size on student engagement and achievement in primary schools

- Investigating the effects of recess and physical activity breaks on attention and learning in primary school

- Exploring the benefits of outdoor play in developing gross motor skills in primary school children

- The effects of educational field trips on knowledge retention in primary school students

- Examining the effects of inclusive classroom practices on students’ attitudes towards diversity in primary schools

- The impact of parental involvement in homework on primary school students’ academic achievement

- Investigating the effectiveness of different assessment methods in primary school classrooms

- The influence of physical activity and exercise on cognitive development in primary school children

- Exploring the benefits of cooperative learning in promoting social skills in primary school students

Secondary Education

- Investigating the effects of school discipline policies on student behavior and academic success in secondary education

- The role of social media in enhancing communication and collaboration among secondary school students

- The impact of school leadership on teacher effectiveness and student outcomes in secondary schools

- Investigating the effects of technology integration on teaching and learning in secondary education

- Exploring the benefits of interdisciplinary instruction in promoting critical thinking skills in secondary schools

- The impact of arts education on creativity and self-expression in secondary school students

- The effectiveness of flipped classrooms in promoting student learning in secondary education

- The role of career guidance programs in preparing secondary school students for future employment

- Investigating the effects of student-centered learning approaches on student autonomy and academic success in secondary schools

- The impact of socio-economic factors on educational attainment in secondary education

- Investigating the impact of project-based learning on student engagement and academic achievement in secondary schools

- Investigating the effects of multicultural education on cultural understanding and tolerance in secondary schools

- The influence of standardized testing on teaching practices and student learning in secondary education

- Investigating the effects of classroom management strategies on student behavior and academic engagement in secondary education

- The influence of teacher professional development on instructional practices and student outcomes in secondary schools

- The role of extracurricular activities in promoting holistic development and well-roundedness in secondary school students

- Investigating the effects of blended learning models on student engagement and achievement in secondary education

- The role of physical education in promoting physical health and well-being among secondary school students

- Investigating the effects of gender on academic achievement and career aspirations in secondary education

- Exploring the benefits of multicultural literature in promoting cultural awareness and empathy among secondary school students

- The impact of school counseling services on student mental health and well-being in secondary schools

- Exploring the benefits of vocational education and training in preparing secondary school students for the workforce

- The role of digital literacy in preparing secondary school students for the digital age

- The influence of parental involvement on academic success and well-being of secondary school students

- The impact of social-emotional learning programs on secondary school students’ well-being and academic success

- The role of character education in fostering ethical and responsible behavior in secondary school students

- Examining the effects of digital citizenship education on responsible and ethical technology use among secondary school students

- The impact of parental involvement in school decision-making processes on student outcomes in secondary schools

- The role of educational technology in promoting personalized learning experiences in secondary schools

- The impact of inclusive education on the social and academic outcomes of students with disabilities in secondary schools

- The influence of parental support on academic motivation and achievement in secondary education

- The role of school climate in promoting positive behavior and well-being among secondary school students

- Examining the effects of peer mentoring programs on academic achievement and social-emotional development in secondary schools

- Examining the effects of teacher-student relationships on student motivation and achievement in secondary schools

- Exploring the benefits of service-learning programs in promoting civic engagement among secondary school students

- The impact of educational policies on educational equity and access in secondary education

- Examining the effects of homework on academic achievement and student well-being in secondary education

- Investigating the effects of different assessment methods on student performance in secondary schools

- Examining the effects of single-sex education on academic performance and gender stereotypes in secondary schools

- The role of mentoring programs in supporting the transition from secondary to post-secondary education

Tertiary Education

- The role of student support services in promoting academic success and well-being in higher education

- The impact of internationalization initiatives on students’ intercultural competence and global perspectives in tertiary education

- Investigating the effects of active learning classrooms and learning spaces on student engagement and learning outcomes in tertiary education

- Exploring the benefits of service-learning experiences in fostering civic engagement and social responsibility in higher education

- The influence of learning communities and collaborative learning environments on student academic and social integration in higher education

- Exploring the benefits of undergraduate research experiences in fostering critical thinking and scientific inquiry skills

- Investigating the effects of academic advising and mentoring on student retention and degree completion in higher education

- The role of student engagement and involvement in co-curricular activities on holistic student development in higher education

- The impact of multicultural education on fostering cultural competence and diversity appreciation in higher education

- The role of internships and work-integrated learning experiences in enhancing students’ employability and career outcomes

- Examining the effects of assessment and feedback practices on student learning and academic achievement in tertiary education

- The influence of faculty professional development on instructional practices and student outcomes in tertiary education

- The influence of faculty-student relationships on student success and well-being in tertiary education

- The impact of college transition programs on students’ academic and social adjustment to higher education

- The impact of online learning platforms on student learning outcomes in higher education

- The impact of financial aid and scholarships on access and persistence in higher education

- The influence of student leadership and involvement in extracurricular activities on personal development and campus engagement

- Exploring the benefits of competency-based education in developing job-specific skills in tertiary students

- Examining the effects of flipped classroom models on student learning and retention in higher education

- Exploring the benefits of online collaboration and virtual team projects in developing teamwork skills in tertiary students

- Investigating the effects of diversity and inclusion initiatives on campus climate and student experiences in tertiary education

- The influence of study abroad programs on intercultural competence and global perspectives of college students

- Investigating the effects of peer mentoring and tutoring programs on student retention and academic performance in tertiary education

- Investigating the effectiveness of active learning strategies in promoting student engagement and achievement in tertiary education

- Investigating the effects of blended learning models and hybrid courses on student learning and satisfaction in higher education

- The role of digital literacy and information literacy skills in supporting student success in the digital age

- Investigating the effects of experiential learning opportunities on career readiness and employability of college students

- The impact of e-portfolios on student reflection, self-assessment, and showcasing of learning in higher education

- The role of technology in enhancing collaborative learning experiences in tertiary classrooms

- The impact of research opportunities on undergraduate student engagement and pursuit of advanced degrees

- Examining the effects of competency-based assessment on measuring student learning and achievement in tertiary education

- Examining the effects of interdisciplinary programs and courses on critical thinking and problem-solving skills in college students

- The role of inclusive education and accessibility in promoting equitable learning experiences for diverse student populations

- The role of career counseling and guidance in supporting students’ career decision-making in tertiary education

- The influence of faculty diversity and representation on student success and inclusive learning environments in higher education

Education-Related Dissertations & Theses

While the ideas we’ve presented above are a decent starting point for finding a research topic in education, they are fairly generic and non-specific. So, it helps to look at actual dissertations and theses in the education space to see how this all comes together in practice.

Below, we’ve included a selection of education-related research projects to help refine your thinking. These are actual dissertations and theses, written as part of Master’s and PhD-level programs, so they can provide some useful insight as to what a research topic looks like in practice.

- From Rural to Urban: Education Conditions of Migrant Children in China (Wang, 2019)

- Energy Renovation While Learning English: A Guidebook for Elementary ESL Teachers (Yang, 2019)

- A Reanalyses of Intercorrelational Matrices of Visual and Verbal Learners’ Abilities, Cognitive Styles, and Learning Preferences (Fox, 2020)

- A study of the elementary math program utilized by a mid-Missouri school district (Barabas, 2020)

- Instructor formative assessment practices in virtual learning environments : a posthumanist sociomaterial perspective (Burcks, 2019)

- Higher education students services: a qualitative study of two mid-size universities’ direct exchange programs (Kinde, 2020)

- Exploring editorial leadership : a qualitative study of scholastic journalism advisers teaching leadership in Missouri secondary schools (Lewis, 2020)

- Selling the virtual university: a multimodal discourse analysis of marketing for online learning (Ludwig, 2020)

- Advocacy and accountability in school counselling: assessing the use of data as related to professional self-efficacy (Matthews, 2020)

- The use of an application screening assessment as a predictor of teaching retention at a midwestern, K-12, public school district (Scarbrough, 2020)

- Core values driving sustained elite performance cultures (Beiner, 2020)

- Educative features of upper elementary Eureka math curriculum (Dwiggins, 2020)

- How female principals nurture adult learning opportunities in successful high schools with challenging student demographics (Woodward, 2020)

- The disproportionality of Black Males in Special Education: A Case Study Analysis of Educator Perceptions in a Southeastern Urban High School (McCrae, 2021)

As you can see, these research topics are a lot more focused than the generic topic ideas we presented earlier. So, in order for you to develop a high-quality research topic, you’ll need to get specific and laser-focused on a specific context with specific variables of interest. In the video below, we explore some other important things you’ll need to consider when crafting your research topic.

Get 1-On-1 Help

If you’re still unsure about how to find a quality research topic within education, check out our Research Topic Kickstarter service, which is the perfect starting point for developing a unique, well-justified research topic.

You Might Also Like:

54 Comments

This is an helpful tool 🙏

Special education

Really appreciated by this . It is the best platform for research related items

Research title related to school of students

Research title related to students

Good idea I’m going to teach my colleagues

You can find our list of nursing-related research topic ideas here: https://gradcoach.com/research-topics-nursing/

Write on action research topic, using guidance and counseling to address unwanted teenage pregnancy in school

Thanks a lot

I learned a lot from this site, thank you so much!

Thank you for the information.. I would like to request a topic based on school major in social studies

parental involvement and students academic performance

Science education topics?

How about School management and supervision pls.?

Hi i am an Deputy Principal in a primary school. My wish is to srudy foe Master’s degree in Education.Please advice me on which topic can be relevant for me. Thanks.

Every topic proposed above on primary education is a starting point for me. I appreciate immensely the team that has sat down to make a detail of these selected topics just for beginners like us. Be blessed.

Kindly help me with the research questions on the topic” Effects of workplace conflict on the employees’ job performance”. The effects can be applicable in every institution,enterprise or organisation.

Greetings, I am a student majoring in Sociology and minoring in Public Administration. I’m considering any recommended research topic in the field of Sociology.

I’m a student pursuing Mphil in Basic education and I’m considering any recommended research proposal topic in my field of study

Kindly help me with a research topic in educational psychology. Ph.D level. Thank you.

Project-based learning is a teaching/learning type,if well applied in a classroom setting will yield serious positive impact. What can a teacher do to implement this in a disadvantaged zone like “North West Region of Cameroon ( hinterland) where war has brought about prolonged and untold sufferings on the indegins?

I wish to get help on topics of research on educational administration

I wish to get help on topics of research on educational administration PhD level

I am also looking for such type of title

I am a student of undergraduate, doing research on how to use guidance and counseling to address unwanted teenage pregnancy in school

the topics are very good regarding research & education .

Can i request your suggestion topic for my Thesis about Teachers as an OFW. thanx you

Would like to request for suggestions on a topic in Economics of education,PhD level

Would like to request for suggestions on a topic in Economics of education

Hi 👋 I request that you help me with a written research proposal about education the format

l would like to request suggestions on a topic in managing teaching and learning, PhD level (educational leadership and management)

request suggestions on a topic in managing teaching and learning, PhD level (educational leadership and management)

I would to inquire on research topics on Educational psychology, Masters degree

I am PhD student, I am searching my Research topic, It should be innovative,my area of interest is online education,use of technology in education

request suggestion on topic in masters in medical education .

Look at British Library as they keep a copy of all PhDs in the UK Core.ac.uk to access Open University and 6 other university e-archives, pdf downloads mostly available, all free.

May I also ask for a topic based on mathematics education for college teaching, please?

Please I am a masters student of the department of Teacher Education, Faculty of Education Please I am in need of proposed project topics to help with my final year thesis

Am a PhD student in Educational Foundations would like a sociological topic. Thank

please i need a proposed thesis project regardging computer science

Greetings and Regards I am a doctoral student in the field of philosophy of education. I am looking for a new topic for my thesis. Because of my work in the elementary school, I am looking for a topic that is from the field of elementary education and is related to the philosophy of education.

Masters student in the field of curriculum, any ideas of a research topic on low achiever students

In the field of curriculum any ideas of a research topic on deconalization in contextualization of digital teaching and learning through in higher education

Amazing guidelines

I am a graduate with two masters. 1) Master of arts in religious studies and 2) Master in education in foundations of education. I intend to do a Ph.D. on my second master’s, however, I need to bring both masters together through my Ph.D. research. can I do something like, ” The contribution of Philosophy of education for a quality religion education in Kenya”? kindly, assist and be free to suggest a similar topic that will bring together the two masters. thanks in advance

Hi, I am an Early childhood trainer as well as a researcher, I need more support on this topic: The impact of early childhood education on later academic success.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Starting the research process

- How to Define a Research Problem | Ideas & Examples

How to Define a Research Problem | Ideas & Examples

Published on November 2, 2022 by Shona McCombes and Tegan George. Revised on May 31, 2023.

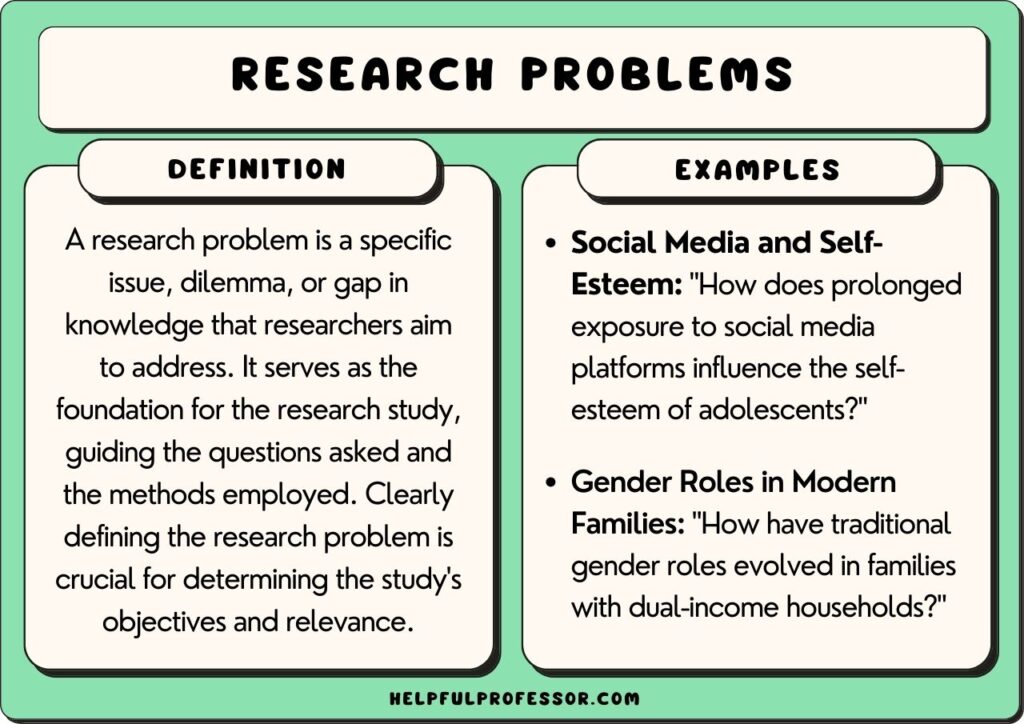

A research problem is a specific issue or gap in existing knowledge that you aim to address in your research. You may choose to look for practical problems aimed at contributing to change, or theoretical problems aimed at expanding knowledge.

Some research will do both of these things, but usually the research problem focuses on one or the other. The type of research problem you choose depends on your broad topic of interest and the type of research you think will fit best.

This article helps you identify and refine a research problem. When writing your research proposal or introduction , formulate it as a problem statement and/or research questions .

Table of contents

Why is the research problem important, step 1: identify a broad problem area, step 2: learn more about the problem, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research problems.

Having an interesting topic isn’t a strong enough basis for academic research. Without a well-defined research problem, you are likely to end up with an unfocused and unmanageable project.

You might end up repeating what other people have already said, trying to say too much, or doing research without a clear purpose and justification. You need a clear problem in order to do research that contributes new and relevant insights.

Whether you’re planning your thesis , starting a research paper , or writing a research proposal , the research problem is the first step towards knowing exactly what you’ll do and why.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

As you read about your topic, look for under-explored aspects or areas of concern, conflict, or controversy. Your goal is to find a gap that your research project can fill.

Practical research problems

If you are doing practical research, you can identify a problem by reading reports, following up on previous research, or talking to people who work in the relevant field or organization. You might look for:

- Issues with performance or efficiency

- Processes that could be improved

- Areas of concern among practitioners

- Difficulties faced by specific groups of people

Examples of practical research problems

Voter turnout in New England has been decreasing, in contrast to the rest of the country.

The HR department of a local chain of restaurants has a high staff turnover rate.

A non-profit organization faces a funding gap that means some of its programs will have to be cut.

Theoretical research problems

If you are doing theoretical research, you can identify a research problem by reading existing research, theory, and debates on your topic to find a gap in what is currently known about it. You might look for:

- A phenomenon or context that has not been closely studied

- A contradiction between two or more perspectives

- A situation or relationship that is not well understood

- A troubling question that has yet to be resolved

Examples of theoretical research problems

The effects of long-term Vitamin D deficiency on cardiovascular health are not well understood.

The relationship between gender, race, and income inequality has yet to be closely studied in the context of the millennial gig economy.

Historians of Scottish nationalism disagree about the role of the British Empire in the development of Scotland’s national identity.

Next, you have to find out what is already known about the problem, and pinpoint the exact aspect that your research will address.

Context and background

- Who does the problem affect?

- Is it a newly-discovered problem, or a well-established one?

- What research has already been done?

- What, if any, solutions have been proposed?

- What are the current debates about the problem? What is missing from these debates?

Specificity and relevance

- What particular place, time, and/or group of people will you focus on?

- What aspects will you not be able to tackle?

- What will the consequences be if the problem is not resolved?

Example of a specific research problem

A local non-profit organization focused on alleviating food insecurity has always fundraised from its existing support base. It lacks understanding of how best to target potential new donors. To be able to continue its work, the organization requires research into more effective fundraising strategies.

Once you have narrowed down your research problem, the next step is to formulate a problem statement , as well as your research questions or hypotheses .

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

Methodology

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

All research questions should be:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis

- Relevant to your field of study and/or society more broadly

Research questions anchor your whole project, so it’s important to spend some time refining them.

In general, they should be:

- Focused and researchable

- Answerable using credible sources

- Complex and arguable

- Feasible and specific

- Relevant and original

Your research objectives indicate how you’ll try to address your research problem and should be specific:

A research aim is a broad statement indicating the general purpose of your research project. It should appear in your introduction at the end of your problem statement , before your research objectives.

Research objectives are more specific than your research aim. They indicate the specific ways you’ll address the overarching aim.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. & George, T. (2023, May 31). How to Define a Research Problem | Ideas & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 14, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/research-process/research-problem/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a problem statement | guide & examples, writing strong research questions | criteria & examples, how to write a strong hypothesis | steps & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

How educational research could play a greater role in K-12 school improvement

Clinical Professor of Applied Human Development, Boston University

Disclosure statement

Detris Honora Adelabu does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

Boston University provides funding as a founding partner of The Conversation US.

View all partners

For the past 20 years, I have taught research methods in education to students here in the U.S. and in other countries. While the purpose of the course is to show students how to do effective research, the ultimate goal of the research is to get better academic results for the nation’s K-12 students and schools.

Vast resources are already being spent on this goal. Between 2019 and 2022, the Institute of Educational Sciences , the research and evaluation arm of the U.S. Education Department, distributed US$473 million in 255 grants to improve educational outcomes.

In 2021, colleges and universities spent approximately $1.6 billion on educational research .

The research is not hard to find. The Educational Research Information Center, a federally run repository, houses 1.6 million educational research sources in over 1,000 scholarly journals.

And there are plenty of opportunities for educational researchers to network and collaborate. Each year, for instance, more than 15,000 educators and researchers gather to present or discuss educational research findings at the annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association .

Yet, for all the time, money and effort that have been spent on producing research in the field of education, the nation seems to have little to show for it in terms of improvements in academic achievement.

Growing gaps

Even prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, test scores were beginning to decline. Results from the 2019 National Assessment of Educational Progress, , or NAEP – the most representative assessment of what elementary and middle school students know across specific subjects – show a widening gap between the highest and lowest achievement levels on the NAEP for fourth grade mathematics and eighth grade reading between 2017-19. During the same period, NAEP outcomes show stagnated growth in reading achievement among fourth graders. By eighth grade, there is a greater gap in reading achievement between the highest- and lowest-achieving students.

Some education experts have even suggested that the chances for progress get dimmer for students as they get older. For instance, in a 2019-2020 report to Congress , Mark Schneider, the Institute of Educational Sciences director, wrote: “for science and math, the longer students stay in school, the more likely they are to fail to meet even NAEP’s basic performance level.”

Scores on the International Assessment of Adult Competencies , a measure of literacy, numeracy and problem-solving skills, suggest a similar pattern of achievement. Achievement levels on the assessment show a slight decline in literacy and numeracy between 2012-14 and 2017. Fewer Americans are scoring at the highest levels of proficiency in literacy and numeracy.

As an educational researcher who focuses on academic outcomes for low-income students and students of color , I believe these troubling results raise serious questions about whether educational research is being put to use.

Are school leaders and policymakers actually reading any of the vast amount of educational research that exists? Or does it go largely unnoticed in voluminous virtual vaults? What, if anything, can be done to make sure that educational research findings and recommendations are actually being tried?

Here are four things I believe can be done in order to make sure that educational research is actually being applied.

1. Build better relationships with school leaders

Educational researchers can reach out to school leaders before doing their research in order to design research based on the needs of schools and schoolchildren. If school leaders can see how educational research can specifically benefit their school community, they may be more likely to implement findings and recommendations from the research.

2. Make policy and practice part of the research process

By implementing new policies and practices based on research findings, researchers can work with school leaders to do further research to see if the new policies and practices actually work.

For example, The Investing in Innovation (i3) Fund was established by the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 to fund the implementation and evaluation of education interventions with a record of improving student achievement. Through the fund, $679 million was distributed through 67 grants – and 12 of those 67 funded projects improved student outcomes. The key to success? Having a “tight implementation” plan, which was shown to produce at least one positive student outcome.

3. Rethink how research impact is measured

As part of the national rankings for colleges of education – that is, the schools that prepare schoolteachers for their careers – engagement with public schools could be made a factor in the rankings. The rankings could also include measurable educational impact.

4. Rethink and redefine how research is distributed

Evidence-based instruction can improve student outcomes . However, public school teachers often can’t afford to access the evidence or the time to make sense of it. Research findings written in everyday language could be distributed at conferences frequented by public school teachers and in the periodicals that they read.

If research findings are to make a difference, I believe there has to be a stronger focus on using research to bring about real-world change in public schools.

- Academic research

- Education research

- Academic results

- Proficiency Level

- K-12 education

- Student test scores

- Higher ed attainment

- Federal role in K-12 education

- K-12 schools

GRAINS RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION CHAIRPERSON

Project Officer, Student Program Development

Faculty of Law - Academic Appointment Opportunities

Operations Manager

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

- Our Mission

The 10 Most Significant Education Studies of 2020

We reviewed hundreds of educational studies in 2020 and then highlighted 10 of the most significant—covering topics from virtual learning to the reading wars and the decline of standardized tests.

In the month of March of 2020, the year suddenly became a whirlwind. With a pandemic disrupting life across the entire globe, teachers scrambled to transform their physical classrooms into virtual—or even hybrid—ones, and researchers slowly began to collect insights into what works, and what doesn’t, in online learning environments around the world.

Meanwhile, neuroscientists made a convincing case for keeping handwriting in schools, and after the closure of several coal-fired power plants in Chicago, researchers reported a drop in pediatric emergency room visits and fewer absences in schools, reminding us that questions of educational equity do not begin and end at the schoolhouse door.

1. To Teach Vocabulary, Let Kids Be Thespians

When students are learning a new language, ask them to act out vocabulary words. It’s fun to unleash a child’s inner thespian, of course, but a 2020 study concluded that it also nearly doubles their ability to remember the words months later.

Researchers asked 8-year-old students to listen to words in another language and then use their hands and bodies to mimic the words—spreading their arms and pretending to fly, for example, when learning the German word flugzeug , which means “airplane.” After two months, these young actors were a remarkable 73 percent more likely to remember the new words than students who had listened without accompanying gestures. Researchers discovered similar, if slightly less dramatic, results when students looked at pictures while listening to the corresponding vocabulary.

It’s a simple reminder that if you want students to remember something, encourage them to learn it in a variety of ways—by drawing it , acting it out, or pairing it with relevant images , for example.

2. Neuroscientists Defend the Value of Teaching Handwriting—Again

For most kids, typing just doesn’t cut it. In 2012, brain scans of preliterate children revealed crucial reading circuitry flickering to life when kids hand-printed letters and then tried to read them. The effect largely disappeared when the letters were typed or traced.

More recently, in 2020, a team of researchers studied older children—seventh graders—while they handwrote, drew, and typed words, and concluded that handwriting and drawing produced telltale neural tracings indicative of deeper learning.

“Whenever self-generated movements are included as a learning strategy, more of the brain gets stimulated,” the researchers explain, before echoing the 2012 study: “It also appears that the movements related to keyboard typing do not activate these networks the same way that drawing and handwriting do.”

It would be a mistake to replace typing with handwriting, though. All kids need to develop digital skills, and there’s evidence that technology helps children with dyslexia to overcome obstacles like note taking or illegible handwriting, ultimately freeing them to “use their time for all the things in which they are gifted,” says the Yale Center for Dyslexia and Creativity.

3. The ACT Test Just Got a Negative Score (Face Palm)

A 2020 study found that ACT test scores, which are often a key factor in college admissions, showed a weak—or even negative —relationship when it came to predicting how successful students would be in college. “There is little evidence that students will have more college success if they work to improve their ACT score,” the researchers explain, and students with very high ACT scores—but indifferent high school grades—often flamed out in college, overmatched by the rigors of a university’s academic schedule.

Just last year, the SAT—cousin to the ACT—had a similarly dubious public showing. In a major 2019 study of nearly 50,000 students led by researcher Brian Galla, and including Angela Duckworth, researchers found that high school grades were stronger predictors of four-year-college graduation than SAT scores.

The reason? Four-year high school grades, the researchers asserted, are a better indicator of crucial skills like perseverance, time management, and the ability to avoid distractions. It’s most likely those skills, in the end, that keep kids in college.

4. A Rubric Reduces Racial Grading Bias

A simple step might help undercut the pernicious effect of grading bias, a new study found: Articulate your standards clearly before you begin grading, and refer to the standards regularly during the assessment process.

In 2020, more than 1,500 teachers were recruited and asked to grade a writing sample from a fictional second-grade student. All of the sample stories were identical—but in one set, the student mentions a family member named Dashawn, while the other set references a sibling named Connor.

Teachers were 13 percent more likely to give the Connor papers a passing grade, revealing the invisible advantages that many students unknowingly benefit from. When grading criteria are vague, implicit stereotypes can insidiously “fill in the blanks,” explains the study’s author. But when teachers have an explicit set of criteria to evaluate the writing—asking whether the student “provides a well-elaborated recount of an event,” for example—the difference in grades is nearly eliminated.

5. What Do Coal-Fired Power Plants Have to Do With Learning? Plenty

When three coal-fired plants closed in the Chicago area, student absences in nearby schools dropped by 7 percent, a change largely driven by fewer emergency room visits for asthma-related problems. The stunning finding, published in a 2020 study from Duke and Penn State, underscores the role that often-overlooked environmental factors—like air quality, neighborhood crime, and noise pollution—have in keeping our children healthy and ready to learn.

At scale, the opportunity cost is staggering: About 2.3 million children in the United States still attend a public elementary or middle school located within 10 kilometers of a coal-fired plant.

The study builds on a growing body of research that reminds us that questions of educational equity do not begin and end at the schoolhouse door. What we call an achievement gap is often an equity gap, one that “takes root in the earliest years of children’s lives,” according to a 2017 study . We won’t have equal opportunity in our schools, the researchers admonish, until we are diligent about confronting inequality in our cities, our neighborhoods—and ultimately our own backyards.

6. Students Who Generate Good Questions Are Better Learners

Some of the most popular study strategies—highlighting passages, rereading notes, and underlining key sentences—are also among the least effective. A 2020 study highlighted a powerful alternative: Get students to generate questions about their learning, and gradually press them to ask more probing questions.

In the study, students who studied a topic and then generated their own questions scored an average of 14 percentage points higher on a test than students who used passive strategies like studying their notes and rereading classroom material. Creating questions, the researchers found, not only encouraged students to think more deeply about the topic but also strengthened their ability to remember what they were studying.

There are many engaging ways to have students create highly productive questions : When creating a test, you can ask students to submit their own questions, or you can use the Jeopardy! game as a platform for student-created questions.

7. Did a 2020 Study Just End the ‘Reading Wars’?

One of the most widely used reading programs was dealt a severe blow when a panel of reading experts concluded that it “would be unlikely to lead to literacy success for all of America’s public schoolchildren.”

In the 2020 study , the experts found that the controversial program—called “Units of Study” and developed over the course of four decades by Lucy Calkins at the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project—failed to explicitly and systematically teach young readers how to decode and encode written words, and was thus “in direct opposition to an enormous body of settled research.”