Find what you need to study

Academic Paper: Discussion and Analysis

5 min read • march 10, 2023

Dylan Black

Introduction

After presenting your data and results to readers, you have one final step before you can finally wrap up your paper and write a conclusion: analyzing your data! This is the big part of your paper that finally takes all the stuff you've been talking about - your method, the data you collected, the information presented in your literature review - and uses it to make a point!

The major question to be answered in your analysis section is simply "we have all this data, but what does it mean?" What questions does this data answer? How does it relate to your research question ? Can this data be explained by, and is it consistent with, other papers? If not, why? These are the types of questions you'll be discussing in this section.

Source: GIPHY

Writing a Discussion and Analysis

Explain what your data means.

The primary point of a discussion section is to explain to your readers, through both statistical means and thorough explanation, what your results mean for your project. In doing so, you want to be succinct, clear, and specific about how your data backs up the claims you are making. These claims should be directly tied back to the overall focus of your paper.

What is this overall focus, you may ask? Your research question ! This discussion along with your conclusion forms the final analysis of your research - what answers did we find? Was our research successful? How do the results we found tie into and relate to the current consensus by the research community? Were our results expected or unexpected? Why or why not? These are all questions you may consider in writing your discussion section.

You showing off all of the cool findings of your research! Source: GIPHY

Why Did Your Results Happen?

After presenting your results in your results section, you may also want to explain why your results actually occurred. This is integral to gaining a full understanding of your results and the conclusions you can draw from them. For example, if data you found contradicts certain data points found in other studies, one of the most important aspects of your discussion of said data is going to be theorizing as to why this disparity took place.

Note that making broad, sweeping claims based on your data is not enough! Everything, and I mean just about everything you say in your discussions section must be backed up either by your own findings that you showed in your results section or past research that has been performed in your field.

For many situations, finding these answers is not easy, and a lot of thinking must be done as to why your results actually occurred the way they did. For some fields, specifically STEM-related fields, a discussion might dive into the theoretical foundations of your research, explaining interactions between parts of your study that led to your results. For others, like social sciences and humanities, results may be open to more interpretation.

However, "open to more interpretation" does not mean you can make claims willy nilly and claim "author's interpretation". In fact, such interpretation may be harder than STEM explanations! You will have to synthesize existing analysis on your topic and incorporate that in your analysis.

Liam Neeson explains the major question of your analysis. Source: GIPHY

Discussion vs. Summary & Repetition

Quite possibly the biggest mistake made within a discussion section is simply restating your data in a different format. The role of the discussion section is to explain your data and what it means for your project. Many students, thinking they're making discussion and analysis, simply regurgitate their numbers back in full sentences with a surface-level explanation.

Phrases like "this shows" and others similar, while good building blocks and great planning tools, often lead to a relatively weak discussion that isn't very nuanced and doesn't lead to much new understanding.

Instead, your goal will be to, through this section and your conclusion, establish a new understanding and in the end, close your gap! To do this effectively, you not only will have to present the numbers and results of your study, but you'll also have to describe how such data forms a new idea that has not been found in prior research.

This, in essence, is the heart of research - finding something new that hasn't been studied before! I don't know if it's just us, but that's pretty darn cool and something that you as the researcher should be incredibly proud of yourself for accomplishing.

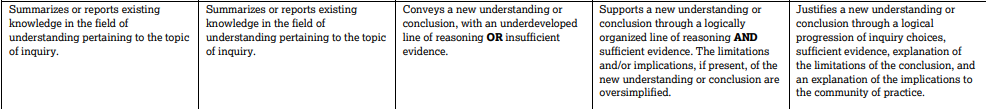

Rubric Points

Before we close out this guide, let's take a quick peek at our best friend: the AP Research Rubric for the Discussion and Conclusion sections.

Source: CollegeBoard

Scores of One and Two: Nothing New, Your Standard Essay

Responses that earn a score of one or two on this section of the AP Research Academic Paper typically don't find much new and by this point may not have a fully developed method nor well-thought-out results. For the most part, these are more similar to essays you may have written in a prior English class or AP Seminar than a true Research paper. Instead of finding new ideas, they summarize already existing information about a topic.

Score of Three: New Understanding, Not Enough Support

A score of three is the first row that establishes a new understanding! This is a great step forward from a one or a two. However, what differentiates a three from a four or a five is the explanation and support of such a new understanding. A paper that earns a three lacks in building a line of reasoning and does not present enough evidence, both from their results section and from already published research.

Scores of Four and Five: New Understanding With A Line of Reasoning

We've made it to the best of the best! With scores of four and five, successful papers describe a new understanding with an effective line of reasoning, sufficient evidence, and an all-around great presentation of how their results signify filling a gap and answering a research question .

As far as the discussions section goes, the difference between a four and a five is more on the side of complexity and nuance. Where a four hits all the marks and does it well, a five exceeds this and writes a truly exceptional analysis. Another area where these two sections differ is in the limitations described, which we discuss in the Conclusion section guide.

You did it!!!! You have, for the most part, finished the brunt of your research paper and are over the hump! All that's left to do is tackle the conclusion, which tends to be for most the easiest section to write because all you do is summarize how your research question was answered and make some final points about how your research impacts your field. Finally, as always...

Key Terms to Review ( 1 )

Research Question

Stay Connected

© 2024 Fiveable Inc. All rights reserved.

AP® and SAT® are trademarks registered by the College Board, which is not affiliated with, and does not endorse this website.

What are your chances of acceptance?

Calculate for all schools, your chance of acceptance.

Your chancing factors

Extracurriculars.

Ultimate Guide to the AP Research Course and Assessment

Is your profile on track for college admissions?

Our free guidance platform determines your real college chances using your current profile and provides personalized recommendations for how to improve it.

The Advanced Placement (AP) curriculum is administered by the College Board and serves as a standardized set of year-long high school classes that are roughly equivalent to one semester of college-level coursework. Although most students enroll in an actual course to prepare for their AP exams, many others will self-study for the exams without enrolling in the actual AP class.

AP classes are generally stand-alone subjects that easily translate to traditional college courses. Typically, they culminate in a standardized exam on which students are graded using a 5-point scale, which colleges and universities will use to determine credit or advanced standing. Starting in fall of 2014, though, this traditional AP course and exam format has begun to adapt in efforts by the College Board to reflect less stringent rote curriculum and a heavier emphasis on critical thinking skills.

The AP Capstone program is at the center of these changes, and its culmination course is AP Research. If you are interested in learning more about the AP Research Course and Assessment, and how they can prepare you for college-level work, read on for CollegeVine’s Ultimate Guide to the AP Research Course and Assessment.

About the Course and Assessment

The AP Research course is the second of two classes required for the AP Capstone™ Diploma . In order to enroll in this course you need to have completed the AP Seminar course during a previous year. Through that course, you will have learned to collect and analyze information with accuracy and precision, developed arguments based on facts, and effectively communicated your conclusions. During the AP Research course, you apply these skills on a larger platform. In the AP Research course, you can expect to learn and apply research methods and practices to address a real-world topic of your choosing, with the end result being the production and defense of a scholarly academic paper. Students who receive a score of 3 or higher on both the AP Seminar and AP Research courses earn an AP Seminar and Research Certificate™. Students who receive a score of 3 or higher on both courses and on four additional AP exams of their choosing receive the AP Capstone Diploma™.

The AP Research course will guide you through the design, planning, and implementation of a year-long, research-based investigation to address a research question of interest to you. While working with an expert advisor, chosen by you with the help of your teacher, you will explore an academic topic, problem, or issue of your choosing and cultivate the skills and discipline necessary to conduct independent research and produce and defend a scholarly academic paper. Through explicit instruction in research methodology, ethical research practices, and documentation processes, you will develop a portfolio of scholarly work to frame your research paper and subsequent presentation of it.

Although the core content and skills remain standardized for every AP Research course, the implementation of this instruction may vary. Some AP Research courses may have a specific disciplinary focus wherein the course content is rooted in a specific subject, such as AP Research STEM Inquiries or AP Research Performing and Visual Arts. Similarly, other AP Research courses are offered in conjunction with a separate and specific AP class, such as AP Research and AP Biology wherein students are concurrently enrolled in both AP courses and content is presented in a cross-curricular approach. Alternatively, AP Research may be presented in the form of an internship wherein students who are already working with a discipline-specific expert adviser conduct independent studies and research of the student’s choosing while taking the AP Research class. Finally, some AP Research courses are delivered independently as a research methods class. In this style of class, students develop inquiry methods for the purpose of determining which method best fits their chosen topic of inquiry/research question, and each student then uses a selected method to complete his or her investigation.

Only schools that currently offer the AP Capstone Diploma may offer the AP Research course. Because it is a part of a larger comprehensive, skills-based program, students may not self-study for the AP Research course or final paper. At this time, home-schooled students, home-school organizations, and online providers are not eligible to participate in AP Capstone.

Your performance in the AP Research course is assessed through two performance tasks. The first is the Academic Paper, which accounts for 75% of your total AP score. In this paper, you will present the findings of your yearlong research in 4,000-5,000 words. Although the official submission deadline for this task is April 30, the College Board strongly recommends that this portion of your assessment be completed by April 15 in order to allow enough time for the second of your performance tasks.

The second performance task is your Presentation and Oral Defense, which accounts for the remaining 25% of your total AP score. Using your research topic, your will prepare a 15-20 minute presentation in an appropriate format with appropriate accompanying media. Your defense will include fielding three to four questions from a panel consisting of your AP Research teacher and two additional panel members chosen at the discretion of your teacher.

In 2016, fewer than 3,000 students submitted an AP Research project, but enrollment is projected to grow rapidly, since 12,000 students took the AP Seminar assessment in 2016 and most will presumably go on to submit an AP Research project in 2017. Scores from the 2016 AP Research projects reveal a high pass rate (score of three or higher) but a difficult rate of mastery. While 67.1% of students taking the assessments scored a three or higher, only 11.6% received the highest score of a five, while nearly 40% received a three. Only 2% of students submitting research projects received the lowest score of one.

A full course description that can help to guide your planning and understanding of the knowledge required for the AP Research course and assessments can be found in the College Board course description .

Read on for tips for successfully completing the AP Research course.

How Should I Prepare for the AP Research Course?

As you undertake the AP Research course and performance tasks, you will be expected to conduct research, write a scholarly paper, and defend your work in a formal presentation. Having already completed the AP Seminar course, these skills should be familiar to you. You should use your scores on the AP Seminar performance task to help guide your preparations for the AP Research performance tasks.

Carefully review your scores from AP Seminar. Make sure you understand where points were lost and why. It may be helpful to schedule a meeting with your AP Seminar teacher to review your work. Alternatively, your AP Research teacher may be willing to go over your AP Seminar projects with you. You might also ask a classmate to review your projects together to get a better idea of where points were earned and where points were lost. Use this review as a jumping point for your AP Research studies. You should go into the course with a good idea of where your strengths lie, and where you need to focus on improving.

A sample timeline for the AP Research course is available on page 36 of the course description . One detail worth noting is that the recommended timeline actually begins not in September with the start of the new school year, but instead begins in May with the completion of the AP Seminar course during the previous school year. It is then that you should begin to consider research topics, problems, or ideas. By September of the following school year, it is recommended that you have already finalized a research question and proposal, completed an annotated bibliography, and prepared to begin a preliminary inquiry proposal for peer review.

What Content Will I Be Held Accountable For During the AP Research Course?

To be successful in the AP Research class, you will begin with learning to investigate relevant topics, compose insightful problem statements, and develop compelling research questions, with consideration of scope, to extend your thinking. Your teacher will expect you to demonstrate perseverance through setting goals, managing time, and working independently on a long-term project. Specifically, you will prepare for your research project by:

- Identifying, applying, and implementing appropriate methods for research and data collection

- Accessing information using effective strategies

- Evaluating the relevance and credibility of information from sources and data

- Reading a bibliography for the purpose of understanding that it is a source for other research and for determining context, credibility, and scope

- Attributing knowledge and ideas accurately and ethically, using an appropriate citation style

- Evaluating strengths and weaknesses of others’ inquiries and studies

As in the AP Research course, you will continue to investigate real-world issues from multiple perspectives, gathering and analyzing information from various sources in order to develop credible and valid evidence- based arguments. You will accomplish this through instruction in the AP Research Big Ideas, also called the QUEST Framework. These include:

- Question and Explore: Questioning begins with an initial exploration of complex topics or issues. Perspectives and questions emerge that spark one’s curiosity, leading to an investigation that challenges and expands the boundaries of one’s current knowledge.

- Understand and Analyze Arguments: Understanding various perspectives requires contextualizing arguments and evaluating the authors’ claims and lines of reasoning.

- Evaluate Multiple Perspectives: Evaluating an issue involves considering and evaluating multiple perspectives, both individually and in comparison to one another.

- Synthesize Ideas: Synthesizing others’ ideas with one’s own may lead to new understandings and is the foundation of a well-reasoned argument that conveys one’s perspective.

- Team, Transform, and Transmit: Teaming allows one to combine personal strengths and talents with those of others to reach a common goal. Transformation and growth occur upon thoughtful reflection. Transmitting requires the adaptation of one’s message based on audience and context.

In addition, you will use four distinct reasoning processes as you approach your research. The reasoning processes are situating, choosing, defending , and connecting . When you situate ideas, you are aware of their context in your own perspective and the perspective of others, ensuring that biases do not lead to false assumptions. When you make choices about ideas and themes, you recognize that these choices will have both intended and unintentional consequences. As you defend your choices, you explain and justify them using a logical line of reasoning. Finally, when you connect ideas you see intersections within and/or across concepts, disciplines, and cultures.

For a glossary of research terms that you should become familiar with, see page 62 of the course description .

How Will I Know If I’m Doing Well in the AP Research Course?

Because your entire score for the AP Research course is determined by your research paper and presentation, which come at the very end of the course, it can be difficult to gauge your success until that point. Do yourself a favor and do not wait until your final scores come back to determine how successful you have been in the course.

As you undertake the AP Research course, there will be many opportunities for formative assessments throughout the semester. These assessments are used to give both you and your teacher an idea of the direction of instruction needed for you to master the skills required in the AP Research course. You should use these assessments to your advantage and capitalize on the feedback you receive through each. A list of possible activities used for these assessments can be found on page 41 of the course description .

Another way that you and your teacher will track your progress is through your Process and Reflection Portfolio (PREP). The PREP serves to document your development as you investigate your research questions, thereby providing evidence that you have demonstrated a sustained effort during the entire inquiry process. You will review your PREP periodically with your teacher, who will use it as a formative assessment to evaluate your progress.

Throughout the course, you will be assigned prompts and questions to respond to in your PREP. You will use this portfolio to document your research or artistic processes, communication with your expert adviser, and reflections on your thought processes. You should also write freely, journaling about your strengths and weaknesses with regard to implementing such processes and developing your arguments or aesthetic rationales.

Your final PREP should include:

- Table of contents

- Completed and approved proposal form

- Specific pieces of work selected by the student to represent what he or she considers to be the best showcase for his or her work. (Examples might include: in-class (teacher-directed) free-writing about the inquiry process, resource list, annotated bibliography of any source important to the student’s work, photographs, charts, spreadsheets, and/or links to videos or other relevant visual research/project artifacts, draft versions of selected sections of the academic paper, or notes in preparation for presentation and oral defense.)

- Documentation of permission(s) received from primary sources, if required — for example, permission(s) from an IRB or other agreements with individuals, institutions, or organizations that provide primary and private data such as interviews, surveys, or investigations

- Documentation or log of the student’s interaction with expert adviser(s) and the role the expert adviser(s) played in the student’s learning and inquiry process (e.g., What areas of expertise did the expert adviser have that the student needed to draw from? Did the student get the help he or she needed — and if not, what did he or she do to ensure that the research process was successful? Which avenues of exploration did the expert adviser help the student to discover?)

- Questions asked to and feedback received from peer and adult reviewers both in the initial stages and at key points along the way

- Reflection on whether or not the feedback was accepted or rejected and why

- Attestation signed by the student which states, “I hereby affirm that the work contained in this Process and Reflection Portfolio is my own and that I have read and understand the AP Capstone TM Policy on Plagiarism and Falsification or Fabrication of Information”

It cannot be stressed enough how important it is to maintain strong communications with your teacher as you progress through the AP Research course. Not only is your teacher your best resource for learning new skills and knowledge, but also it is your teacher who will be responsible for grading your final performance tasks and as such, you should always have a strong understanding of how your work is being assessed and the ways in which you can improve it. Remember, your teacher wants you to succeed just as much as you do; work together as a team to optimize your chances.

How Should I Choose a Research Topic?

You will begin to consider research topics before the school year even starts. If your AP Research class is offered in conjunction with another course, such as those rooted in a specific subject or linked to another concurrent AP course, you will have some idea of the direction in which your research should head. Regardless of whether you know the precise subject matter of your topic, you should begin by asking yourself what you want to know, learn, or understand. The AP Research class provides a unique opportunity for you to guide your own learning in a direction that is genuinely interesting to you. You will find your work more engaging, exciting, and worthwhile if you choose a topic that you want to learn more about.

As you begin to consider research topics, you should:

- Develop a list of topics and high-level questions that spark your interest to engage in an individual research project

- Identify potential expert advisers to guide you in the planning and development of your research project (For tips on how to find a mentor, read CollegeVine’s “ How to Choose a Winning Science Fair Project Idea ”)

- Identify potential opportunities (if you are interested) to perform primary research with an expert adviser during the summer, via internships or summer research projects for high school students offered in the community and local higher education institutions

- Discuss research project planning skills and ideas with students who are currently taking or have already taken the AP Research course

You might also find inspiration from reading about past AP Research topics. One list of potential research questions can be found here and another can be found here . Keep in mind that these lists make great starting points and do a good job of getting you thinking about important subjects, but your research topic should ultimately be something that you develop independently as the result of careful introspection, discussions with your teacher and peers, and your own preliminary research.

Finally, keep in mind that if you pursue a research project that involves human subjects, your proposal will need to be reviewed and approved by an institutional review board (IRB) before experimentation begins. Talk with your teacher to decide if this is the right path for you before you get too involved in a project that may not be feasible.

Once you have decided on a research topic, complete an Inquiry Proposal Form. This will be distributed by your teacher and can also be found on page 55 of the course description .

How Do I Conduct My Research?

By the time you begin your AP Research course, you will have already learned many of the basics about research methods during your AP Seminar course. You should be comfortable collecting and analyzing information with accuracy and precision, developing arguments based on facts, and effectively communicating your point of view. These will be essential skills as you move forward in your AP Research project.

As you undertake your work, remember the skills you’ve already learned about research:

- Use strategies to aid your comprehension as you tackle difficult texts.

- Identify the author’s main idea and the methods that he or she uses to support it.

- Think about biases and whether other perspectives are acknowledged.

- Assess the strength of research, products, and arguments.

- Look for patterns and trends as you strive to make connections between multiple arguments.

- Think about what other issues, questions, or topics could be explored further.

You should be certain to keep track of all sources used in your research and cite them appropriately. The College Board has a strict policy against plagiarism. You can read more about its specifics on page 60 of the course description .

How Do I Write My Paper?

Before you begin writing your final paper, make sure to thoroughly read the Task Overview handout which will be distributed by your teacher. If you would like to see it beforehand, it can be found on page 56 of the course description . You should also review the outline of required paper sections on page 49 of the course description .

Your paper must contain the following sections:

› Introduction

› Method, Process, or Approach

› Results, Product, or Findings

› Discussion, Analysis, and/or Evaluation

› Conclusion and Future Directions

› Bibliography

Before you begin writing, organize your ideas and findings into an outline using the sections listed above. Be sure to consider how you can connect and analyze the evidence in order to develop an argument and support a conclusion. Also think about if there are any alternate conclusions that could be supported by your evidence and how you can acknowledge and account for your own biases and assumptions.

Begin your paper by introducing and contextualizing your research question or problem. Make sure to include your initial assumptions and/or hypothesis. Next, include a literature review of previous work in the field and various perspectives on your topic. Use the literature review to highlight the gap in the current field of knowledge to be addressed by your research project. Then, explain and justify your methodology, present your findings, evidence, or data, and interpret the significance of these findings. Discuss implications for further research or limitations of your existing project. Finally, reflect on the project, how it could impact its field, and any possible next steps. Your paper should conclude with a comprehensive bibliography including all of the sources used in your process.

Make sure to proofread and edit your paper yourself, have it proofread and edited by a friend, and then proofread and edit it again before you complete your final draft.

How Do I Prepare For My Oral Defense?

Once your paper is finished, you may be tempted to sit back and rest on your laurels. Although you’ve no doubt expended a tremendous about of energy in producing a final product you can be proud of, don’t forget that the work is not over yet. Your oral defense accounts for 25% of your total score so it should be taken seriously.

Your oral defense is a 15-20 minute presentation that uses appropriate media to present your findings to an oral defense panel. You may choose any appropriate format for your presentation, as long as the presentation reflects the depth of your research. If your academic paper was accompanied by an additional piece of scholarly work (e.g., performance, exhibit, product), you should arrange with your teacher for him or her, along with the panelists, to view the scholarly work prior to your presentation.

As you plan your presentation, consider how you can best appeal to your audience. Consider different mediums for your presentation, and how those mediums might affect your credibility as a presenter. You want to be engaging to your audience while still being taken seriously.

Following your presentation, you will field three or four questions from your panelists. These will include one question pertaining to your research or inquiry process, one question focused on your depth of understanding, and one question about your reflection throughout the inquiry process as evidenced in your PREP. The fourth question and any follow-up questions are at the discretion of the panel. A list of sample oral defense questions begins on page 52 of the course description . For a complete outline of the oral defense, see page 49 of the course description .

How Will My Work Be Assessed?

Because this assessment is only available to students enrolled in the AP Capstone program, your teacher will register you for the assessment when you enroll in the course. You should confirm with your teacher that you are registered for the assessment no later than March 1.

You will submit your final paper and complete your oral presentation no later than April 30, at which point your teacher will submit your work and scores through an AP Digital Portfolio. Your presentation will be scored by your teacher alone. Your paper will be scored by your teacher and validated by the College Board.

You may find the scoring rubric from the 2016 performance tasks available here . You may find a collection authentic student research papers and scoring explanations available here .

Preparing for any AP assessment can be a stressful process. Having a specific plan of attack and a firm grasp of how your work is assessed will help you to feel prepared and score well. Use CollegeVine’s Ultimate Guide to the AP Research Course and Assessment to help shape your understanding of the course and how to complete your performance tasks effectively. When submission day arrives, you should feel better prepared and informed about the work you have produced.

For more about information about APs, check out these CollegeVine posts:

• Can AP Tests Actually Save You Thousands of Dollars?

• Should I Take AP/IB/Honors Classes?

• How to Choose Which AP Courses and Exams to Take

• What If My School Doesn’t Offer AP or IB Courses?

• Are All APs Created Equal in Admissions?

Want access to expert college guidance — for free? When you create your free CollegeVine account, you will find out your real admissions chances, build a best-fit school list, learn how to improve your profile, and get your questions answered by experts and peers—all for free. Sign up for your CollegeVine account today to get a boost on your college journey.

Related CollegeVine Blog Posts

Generate accurate APA citations for free

- Knowledge Base

- APA Style 7th edition

- How to write an APA results section

Reporting Research Results in APA Style | Tips & Examples

Published on December 21, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on January 17, 2024.

The results section of a quantitative research paper is where you summarize your data and report the findings of any relevant statistical analyses.

The APA manual provides rigorous guidelines for what to report in quantitative research papers in the fields of psychology, education, and other social sciences.

Use these standards to answer your research questions and report your data analyses in a complete and transparent way.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What goes in your results section, introduce your data, summarize your data, report statistical results, presenting numbers effectively, what doesn’t belong in your results section, frequently asked questions about results in apa.

In APA style, the results section includes preliminary information about the participants and data, descriptive and inferential statistics, and the results of any exploratory analyses.

Include these in your results section:

- Participant flow and recruitment period. Report the number of participants at every stage of the study, as well as the dates when recruitment took place.

- Missing data . Identify the proportion of data that wasn’t included in your final analysis and state the reasons.

- Any adverse events. Make sure to report any unexpected events or side effects (for clinical studies).

- Descriptive statistics . Summarize the primary and secondary outcomes of the study.

- Inferential statistics , including confidence intervals and effect sizes. Address the primary and secondary research questions by reporting the detailed results of your main analyses.

- Results of subgroup or exploratory analyses, if applicable. Place detailed results in supplementary materials.

Write up the results in the past tense because you’re describing the outcomes of a completed research study.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Before diving into your research findings, first describe the flow of participants at every stage of your study and whether any data were excluded from the final analysis.

Participant flow and recruitment period

It’s necessary to report any attrition, which is the decline in participants at every sequential stage of a study. That’s because an uneven number of participants across groups sometimes threatens internal validity and makes it difficult to compare groups. Be sure to also state all reasons for attrition.

If your study has multiple stages (e.g., pre-test, intervention, and post-test) and groups (e.g., experimental and control groups), a flow chart is the best way to report the number of participants in each group per stage and reasons for attrition.

Also report the dates for when you recruited participants or performed follow-up sessions.

Missing data

Another key issue is the completeness of your dataset. It’s necessary to report both the amount and reasons for data that was missing or excluded.

Data can become unusable due to equipment malfunctions, improper storage, unexpected events, participant ineligibility, and so on. For each case, state the reason why the data were unusable.

Some data points may be removed from the final analysis because they are outliers—but you must be able to justify how you decided what to exclude.

If you applied any techniques for overcoming or compensating for lost data, report those as well.

Adverse events

For clinical studies, report all events with serious consequences or any side effects that occured.

Descriptive statistics summarize your data for the reader. Present descriptive statistics for each primary, secondary, and subgroup analysis.

Don’t provide formulas or citations for commonly used statistics (e.g., standard deviation) – but do provide them for new or rare equations.

Descriptive statistics

The exact descriptive statistics that you report depends on the types of data in your study. Categorical variables can be reported using proportions, while quantitative data can be reported using means and standard deviations . For a large set of numbers, a table is the most effective presentation format.

Include sample sizes (overall and for each group) as well as appropriate measures of central tendency and variability for the outcomes in your results section. For every point estimate , add a clearly labelled measure of variability as well.

Be sure to note how you combined data to come up with variables of interest. For every variable of interest, explain how you operationalized it.

According to APA journal standards, it’s necessary to report all relevant hypothesis tests performed, estimates of effect sizes, and confidence intervals.

When reporting statistical results, you should first address primary research questions before moving onto secondary research questions and any exploratory or subgroup analyses.

Present the results of tests in the order that you performed them—report the outcomes of main tests before post-hoc tests, for example. Don’t leave out any relevant results, even if they don’t support your hypothesis.

Inferential statistics

For each statistical test performed, first restate the hypothesis , then state whether your hypothesis was supported and provide the outcomes that led you to that conclusion.

Report the following for each hypothesis test:

- the test statistic value,

- the degrees of freedom ,

- the exact p- value (unless it is less than 0.001),

- the magnitude and direction of the effect.

When reporting complex data analyses, such as factor analysis or multivariate analysis, present the models estimated in detail, and state the statistical software used. Make sure to report any violations of statistical assumptions or problems with estimation.

Effect sizes and confidence intervals

For each hypothesis test performed, you should present confidence intervals and estimates of effect sizes .

Confidence intervals are useful for showing the variability around point estimates. They should be included whenever you report population parameter estimates.

Effect sizes indicate how impactful the outcomes of a study are. But since they are estimates, it’s recommended that you also provide confidence intervals of effect sizes.

Subgroup or exploratory analyses

Briefly report the results of any other planned or exploratory analyses you performed. These may include subgroup analyses as well.

Subgroup analyses come with a high chance of false positive results, because performing a large number of comparison or correlation tests increases the chances of finding significant results.

If you find significant results in these analyses, make sure to appropriately report them as exploratory (rather than confirmatory) results to avoid overstating their importance.

While these analyses can be reported in less detail in the main text, you can provide the full analyses in supplementary materials.

Are your APA in-text citations flawless?

The AI-powered APA Citation Checker points out every error, tells you exactly what’s wrong, and explains how to fix it. Say goodbye to losing marks on your assignment!

Get started!

To effectively present numbers, use a mix of text, tables , and figures where appropriate:

- To present three or fewer numbers, try a sentence ,

- To present between 4 and 20 numbers, try a table ,

- To present more than 20 numbers, try a figure .

Since these are general guidelines, use your own judgment and feedback from others for effective presentation of numbers.

Tables and figures should be numbered and have titles, along with relevant notes. Make sure to present data only once throughout the paper and refer to any tables and figures in the text.

Formatting statistics and numbers

It’s important to follow capitalization , italicization, and abbreviation rules when referring to statistics in your paper. There are specific format guidelines for reporting statistics in APA , as well as general rules about writing numbers .

If you are unsure of how to present specific symbols, look up the detailed APA guidelines or other papers in your field.

It’s important to provide a complete picture of your data analyses and outcomes in a concise way. For that reason, raw data and any interpretations of your results are not included in the results section.

It’s rarely appropriate to include raw data in your results section. Instead, you should always save the raw data securely and make them available and accessible to any other researchers who request them.

Making scientific research available to others is a key part of academic integrity and open science.

Interpretation or discussion of results

This belongs in your discussion section. Your results section is where you objectively report all relevant findings and leave them open for interpretation by readers.

While you should state whether the findings of statistical tests lend support to your hypotheses, refrain from forming conclusions to your research questions in the results section.

Explanation of how statistics tests work

For the sake of concise writing, you can safely assume that readers of your paper have professional knowledge of how statistical inferences work.

In an APA results section , you should generally report the following:

- Participant flow and recruitment period.

- Missing data and any adverse events.

- Descriptive statistics about your samples.

- Inferential statistics , including confidence intervals and effect sizes.

- Results of any subgroup or exploratory analyses, if applicable.

According to the APA guidelines, you should report enough detail on inferential statistics so that your readers understand your analyses.

- the test statistic value

- the degrees of freedom

- the exact p value (unless it is less than 0.001)

- the magnitude and direction of the effect

You should also present confidence intervals and estimates of effect sizes where relevant.

In APA style, statistics can be presented in the main text or as tables or figures . To decide how to present numbers, you can follow APA guidelines:

- To present three or fewer numbers, try a sentence,

- To present between 4 and 20 numbers, try a table,

- To present more than 20 numbers, try a figure.

Results are usually written in the past tense , because they are describing the outcome of completed actions.

The results chapter or section simply and objectively reports what you found, without speculating on why you found these results. The discussion interprets the meaning of the results, puts them in context, and explains why they matter.

In qualitative research , results and discussion are sometimes combined. But in quantitative research , it’s considered important to separate the objective results from your interpretation of them.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2024, January 17). Reporting Research Results in APA Style | Tips & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 29, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/apa-style/results-section/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, how to write an apa methods section, how to format tables and figures in apa style, reporting statistics in apa style | guidelines & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

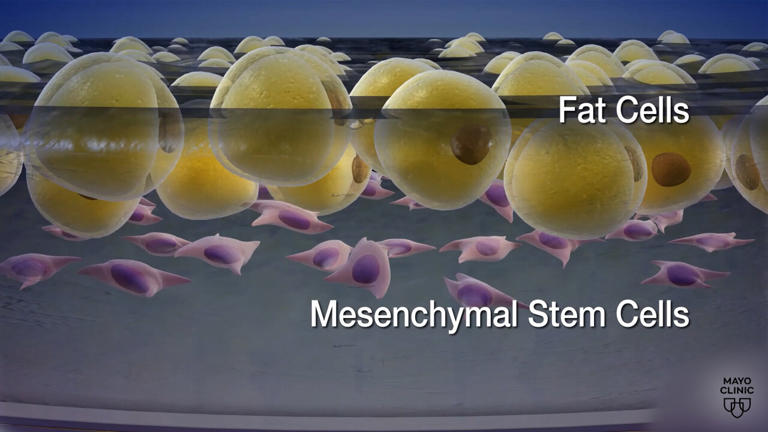

Study documents safety, improvements from stem cell therapy after spinal cord injury

A Mayo Clinic study shows stem cells derived from patients' own fat are safe and may improve sensation and movement after traumatic spinal cord injuries. The findings from the Phase I clinical trial appear in Nature Communications . The results of this early research offer insights into the potential of cell therapy for people living with spinal cord injuries and paralysis for whom options to improve function are extremely limited.

In the study of 10 adults, the research team noted seven participants demonstrated improvements based on the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale. Improvements included increased sensation when tested with pinprick and light touch, increased strength in muscle motor groups, and recovery of voluntary anal contraction, which aids in bowel function.

The scale has five levels, ranging from complete loss of function to normal function. The seven participants who improved each moved up at least one level on the ASIA scale. Three patients in the study had no response, meaning they did not improve but did not get worse.

"This study documents the safety and potential benefit of stem cells and regenerative medicine," says Mohamad Bydon, M.D., a Mayo Clinic neurosurgeon and first author of the study.

"Spinal cord injury is a complex condition. Future research may show whether stem cells in combination with other therapies could be part of a new paradigm of treatment to improve outcomes for patients."

No serious adverse events were reported after stem cell treatment. The most commonly reported side effects were headache and musculoskeletal pain that resolved with over-the-counter treatment.

In addition to evaluating safety, this Phase I clinical trial had a secondary outcome of assessing changes in motor and sensory function. The authors note that motor and sensory results are to be interpreted with caution given limits of Phase I trials. Additional research is underway among a larger group of participants to further assess risks and benefits.

The full data on the 10 patients follows a 2019 case report that highlighted the experience of the first study participant who demonstrated significant improvement in motor and sensory function.

Stem cells' mechanism of action not fully understood

In the multidisciplinary clinical trial, participants had spinal cord injuries from motor vehicle accidents, falls and other causes. Six had neck injuries; four had back injuries. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 65.

Participants' stem cells were collected by taking a small amount of fat from a 1- to 2-inch incision in the abdomen or thigh. Over four weeks, the cells were expanded in the laboratory to 100 million cells and then injected into the patients' lumbar spine in the lower back. Over two years, each study participant was evaluated at Mayo Clinic 10 times.

Although it is understood that stem cells move toward areas of inflammation—in this case the location of the spinal cord injury—the cells' mechanism of interacting with the spinal cord is not fully understood, Dr. Bydon says.

As part of the study, researchers analyzed changes in participants' MRIs and cerebrospinal fluid as well as in responses to pain, pressure and other sensation. The investigators are looking for clues to identify injury processes at a cellular level and avenues for potential regeneration and healing.

The spinal cord has limited ability to repair its cells or make new ones. Patients typically experience most of their recovery in the first six to 12 months after injuries occur. Improvement generally stops 12 to 24 months after injury.

One unexpected outcome of the trial was that two patients with cervical spine injuries of the neck received stem cells 22 months after their injuries and improved one level on the ASIA scale after treatment. Two of three patients with complete injuries of the thoracic spine—meaning they had no feeling or movement below their injury between the base of the neck and mid-back—moved up two ASIA levels after treatment.

Each regained some sensation and some control of movement below the level of injury. Based on researchers' understanding of traumatic thoracic spinal cord injury, only 5% of people with a complete injury would be expected to regain any feeling or movement.

"In spinal cord injury, even a mild improvement can make a significant difference in that patient's quality of life," Dr. Bydon says.

Research continues into stem cells for spinal cord injuries

Stem cells are used mainly in research in the U.S., and fat-derived stem cell treatment for spinal cord injury is considered experimental by the Food and Drug Administration.

Between 250,000 and 500,000 people worldwide suffer a spinal cord injury each year, according to the World Health Organization .

An important next step is assessing the effectiveness of stem cell therapies and subsets of patients who would most benefit, Dr. Bydon says. Research is continuing with a larger, controlled trial that randomly assigns patients to receive either the stem cell treatment or a placebo without stem cells.

"For years, treatment of spinal cord injury has been limited to supportive care, more specifically stabilization surgery and physical therapy," Dr. Bydon says.

"Many historical textbooks state that this condition does not improve. In recent years, we have seen findings from the medical and scientific community that challenge prior assumptions. This research is a step forward toward the ultimate goal of improving treatments for patients."

More information: Mohamad Bydon et al, Nature Communications (2024).

Provided by Mayo Clinic

Advertisement

Perceptions towards pronatalist policies in Singapore

- Original Research

- Open access

- Published: 11 May 2023

- Volume 40 , article number 14 , ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Jolene Tan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4968-3482 1

7223 Accesses

4 Citations

8 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Fertility rates have been declining in most high-income countries. Singapore is at the forefront of developing pronatalist policies to increase birth rates. This study examines perceptions towards pronatalist policies among men and women in Singapore and compares which policies are perceived as the most important contributors to the conduciveness for childbearing. Using data from the Singapore Perceptions of the Marriage and Parenthood Package study ( N = 2000), the results from dominance analysis highlight two important findings. First, paternity leave, shared parental leave, and the Baby Bonus are the top three contributors to the conduciveness to have children. Second, the combined positive effect of financial incentives and work–life policies is perceived to be favorable to fertility. The findings suggest that low-fertility countries may wish to consider adopting this basket of policies as they are like to be regarded as supportive of childbearing. Although previous research suggests that pronatalist policies may only have a modest effect on fertility, the findings raise further questions as to whether fertility may decline even further in the absence of these policies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Education and Parenting in the Philippines

The New Roles of Men and Women and Implications for Families and Societies

Parenting in the Philippines

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Increasing birth rates in low-fertility countries is important for maintaining sustainable populations. This has become an important policy agenda in many countries with an aging society and workforce. In Singapore, the rapid demographic transition that occurred from the 1960–2000s has led to a precipitous decline in fertility, resulting in a shift from a relatively youthful population to an aging population that is increasingly dependent on immigration for population growth (Yap & Gee, 2015 ). Singapore’s total fertility rates have declined substantially from 5.76 to 1.12 children per woman between 1960 and 2021 (Singapore Department of Statistics, 2022a ). The country’s low fertility imposes significant strains on the government and economy due to the negative consequences associated with a shrinking labor force and an aging population (Jones, 2012 ). To address these demographic and economic challenges, policies to increase fertility have become a priority for Singapore and many other low-fertility nations.

Since the 1980s, the Singaporean government has introduced a range of pronatalist policies to reduce the financial costs of parenthood and facilitate a more conducive work–family balance. However, these policies appear to have only modest effects on Singapore’s fertility rates (Saw, 2016 ). Recent studies point to a potential mistargeting of pronatalist policies as a reason for the lack of policy effectiveness in several advanced Asian societies, including Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea (Chen et al., 2018 , 2020 ). The studies found that policies prioritizing higher order births in Singapore may not provide adequate support to women aged 30–34 to facilitate their transition to parenthood. Thus, it is suggested that the policy focus should shift towards supporting this group of women instead.

Despite the call for policy improvements, systematic research into the needs of potential policy beneficiaries has been very limited (Sun, 2012 ). Most studies on pronatalist policies tend to focus on analyses aimed at quantifying outcomes or attributing fertility change to existing policy (e.g., Drago et al., 2011 ; Son, 2018 ). The needs of childbearing couples may be overlooked due to a lack of research and data regarding what they think about the range of pronatalist policy measures and how conducive these policies are to their fertility choices. Consequently, little is known about whether pronatalist policies actually fit the needs of target populations and their circumstances.

The present study attempts to fill this gap by using a unique data set to examine the perceptions of married men and women towards a range of policy measures intended to raise fertility rates. Drawing on data from the Perception of Policies in Singapore (POPS) Survey 7: Perceptions of the Marriage and Parenthood Package, the study investigates the relative importance of pronatalist policies among married people and within different sociodemographic subgroups (i.e., by age, sex, and child parity). It examines two research questions. First, to what extent do pronatalist policies in Singapore contribute to a conducive environment in which married, heterosexual couples will choose to have children? Conduciveness refers to the extent to which the policies support and facilitate the likelihood of childbearing among couples. Second, how do public perceptions towards different policies differ by individual sociodemographic characteristics?

While this study is unable to directly address the cause and effect of pronatalist policies on fertility, it serves as a first step in investigating how the married population views the importance of these policies, which may support further policy discussions about whether to replicate, scale up or revise pronatalist policies, and how to target different population subgroups more effectively. The policies under investigation—including baby bonus payments; tax incentives; paternal, maternal, and shared parental leave; and childcare support—have been widely adopted by governments around the world (United Nations Population Division, 2017 ). Using Singapore as a case study, the study provides useful insights into the relevance and importance of policy in addressing the potential needs of married men and women in the reproductive age.

Pronatal family policies: a review

Financial incentives and work–family initiatives.

The rational choice approach to pronatalist policy design posits that policies that lower the costs of having children and provide childcare support to parents are likely to positively impact fertility (Coleman, 1990 ; Schultz, 1990 ). Financial incentives provided to parents through cash payments, tax relief, and subsidies can alleviate the direct costs Footnote 1 of having and raising a child. On the other hand, the gender relations perspective posits that work–family policies, such as parental leave and childcare subsidies, may alleviate the indirect costs Footnote 2 of having children and offset the additional time spent on childbearing and child-raising (McDonald, 2006 ).

However, empirical evidence on the impact of financial incentives on fertility has been mixed (Gauthier, 2007 ). Some studies have found positive associations between financial incentives and fertility (Drago et al., 2011 ; Milligan, 2005 ), whereas other studies have found no association between the two (Deutscher & Breunig, 2018 ; Jones, 2019 ). A recent systematic review of quasi-experimental evaluations of fertility policies (Bergsvik et al., 2020 ) showed that universal transfers, childcare, and a reduction in the costs of health services may have a positive impact on fertility, but the effects varied by age, child parity and country context. Notwithstanding the variability in results, one of the most consistent findings is that the overall effect of financial incentives on fertility tends to be modest and temporary, as financial incentives only cover a small fraction of the total cost of raising a child (Thevenon & Gauthier, 2011 ).

Work–family initiatives that support parents in combining work and family responsibilities have been shown to reduce the opportunity cost of children and increase fertility in more gender-egalitarian societies (Duvander et al., 2020 ; Rindfuss et al., 2010 ; Tan, 2022a , b ; Thevenon, 2011 ). However, in low-fertility Asian societies that are heavily influenced by Confucianism, working mothers still tend to shoulder a disproportionately larger share of childcare and domestic tasks (Singapore Ministry of Social & Family Development, 2017 ). In a comparison of parental leave and childcare support policies in Sweden and South Korea, Lee et al. ( 2016 ) found that the policies were less effective in South Korea due to women’s significantly higher contribution to household labor relative to that of men. Considering that Singapore is ranked 54th out of 156 countries on the Global Gender Gap Index 2021, lying approximately halfway between Sweden in fifth place and South Korea in 102nd place, work–family initiatives may provide opportunities for men to get involved in the family, and assist in creating a more conducive environment for couples to have children in Singapore (World Economic Forum, 2021 ).

Pronatal policy targeting

To understand why existing policies may have been less successful than anticipated in increasing fertility rates, recent studies have identified the potential mistargeting of policies as a possible reason for the limited impact of policy on fertility (Chen et al., 2018 , 2020 ; Gauthier, 2016 ). In Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, Gauthier ( 2016 ) found a misalignment between the supply and demand of pronatalist policies. In particular, the high costs of children are perceived to be a major barrier to childbearing in the three East Asian societies, but governmental financial support remains inadequate in meeting the needs of families, especially in light of rising private education costs. In addition to financial costs, there is also a perceived incompatibility between work and family responsibilities that may not have been adequately addressed by policy. As women are often expected to take on a second shift after work and perform the role of a homemaker and caregiver, work–family conflicts hinder progression to higher parities as time and resource demands increase with each additional child (Chen & Yip, 2017 ; Torr & Short, 2004 ).

Some studies have emphasized the need for increased efforts to implement better targeted pronatalist policies. Chen and Yip ( 2017 ) stressed that the perceived challenges of parenthood tend to differ according to child parity. This is because the needs and considerations of parents become more complex as parity increases (Frejka et al., 2010 ). Policies are likely to be more conducive for couples making their first transition to parenthood, as the desire for the first child is generally considered intrinsically motivated; hence, policies tend to be viewed as facilitative or supportive of intended childbearing (Botev, 2015 ). Conversely, policies aimed at incentivizing higher order births could reduce the motivation to have additional children, as they may be perceived as insufficient, coercive, or restrictive of individual autonomy (Frey, 2012 ). Given that the motivation and needs of high-parity parents are unlikely to be met by extrinsic incentives, policies may be less conducive for those with high parity than those with low parity (Botev, 2015 ).

There is also a general age pattern of fertility that aligns with the fecundity (i.e., reproductive capacity) of each couple. Given that fecundability declines as people get older, responses to policy intervention may also wane with time. Previous research suggests that people are more likely to adjust their fertility intentions downwards as they age and, thus, pronatalist policies may be less conducive for older individuals compared to their younger counterparts (Chen & Yip, 2017 ; Liefbroer, 2009 ). There could also be gender differences in parenting responsibilities and expectations because men and women negotiate the demands of parenthood differently (Barnes, 2015 ). Given that women tend to bear the burden of childbearing and child-raising, there are two ways in which policies may be perceived. Policies may be perceived as conducive if women feel that the policies can improve gender equity in the division of housework and childcare (McDonald, 2013 ). However, if women feel that the unequal division of domestic labor is likely to persist, then the usefulness of policy may be weakened.

The Singaporean context

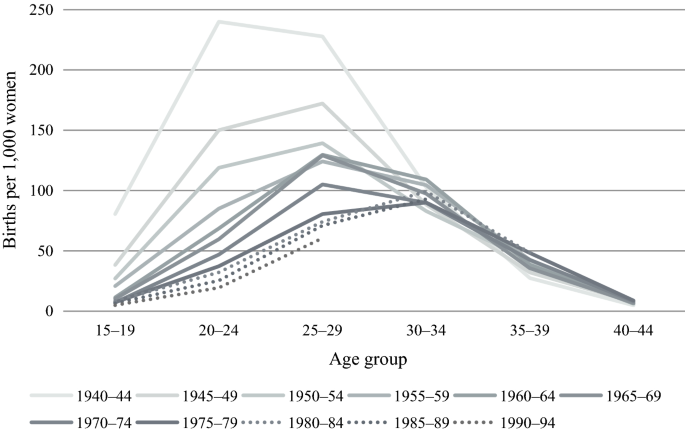

A contextual understanding of Singapore’s fertility trends and policy framework is important for highlighting ongoing demographic and policy shifts. Singapore’s total fertility rate of 1.12 children per woman in 2021 is one of the lowest in the world. Significant delays in childbearing can be observed by the shifting age-pattern of fertility in Fig. 1 . The figure shows that increases in fertility at ages 30 and older did not make up for fertility declines in younger age groups, resulting in an overall decrease in fertility rates across cohorts.

Source : Singapore Department of Statistics ( 2022a )

Cohort-age specific fertility rates, 1940–1994.

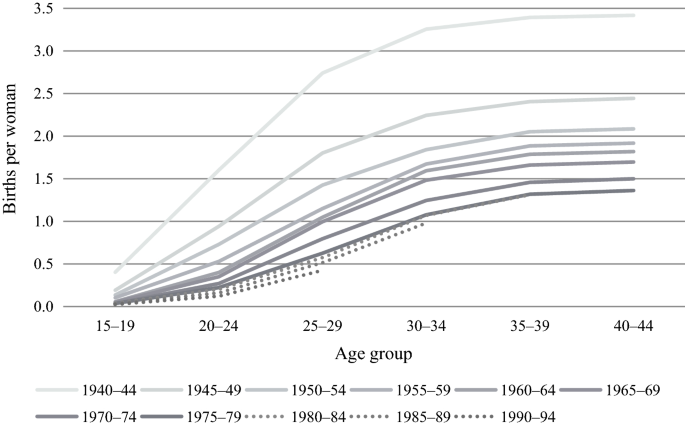

Figure 2 shows the declining cumulative cohort fertility rates for each successive cohort after the 1940–1944 cohort. The persistent decline in cohort fertility may lead to an older population age structure and create a momentum for future population decline (Lutz et al., 2006 ). It is thus a demographic imperative for Singapore to increase its fertility rates to ensure a sustainable population.

Cumulative cohort fertility rates in 2020.

Singapore is known for its comprehensive and long-standing policies to encourage childbearing. Since 1987, the government has started promoting family formation, and by 1995 had more pronatalist policies in place than any other country. A comprehensive Marriage and Parenthood Package was introduced by the government in 2001 as part of the ongoing effort to address Singapore’s falling birth rates (National Population and Talent Division, 2012). A range of policy measures were implemented to “create a total environment conducive to raising a family” (National Archives of Singapore, 2000 , para. 118).

Based on Heitlinger ( 1991 ) and McDonald’s ( 2002 ) policy classification framework, Singapore’s pronatalist policies can be grouped into two broad categories: financial incentives and work–family initiatives. Financial incentives include cash payments, tax relief, and housing subsidies. The Baby Bonus cash payments was introduced in 2001 to help families defray the costs of raising a child and offer financial support following the birth of a child. When it was first implemented, eligible couples received cash gifts for having a second (S$500 Footnote 3 ) or third child (S$1000). The amount has since increased to S$8000 for a first or second child and S$10,000 for a third or subsequent child (Made for Families, 2022a ). The Working Mother’s Child Relief provides a tax deduction on a proportion of women’s earned income to encourage working mothers to have children and stay in the workforce. Working mothers may claim 15% of their earned income for their first child, 20% for their second child, and 25% for their third child and any subsequent children, with a maximum cap at 100% of their earned income (Inland Revenue Authority of Singapore, 2022 ). Housing schemes and grants were introduced to help couples purchase and finance their first home. Priority is given to married couples with or expecting a child and families with more than two children (Housing & Development Board, 2022 ). Eligible first-time home buyers who are married may qualify for a housing grant of up to S$80,000 to help with their flat purchase (Housing & Development Board, 2022 ). The government also assists with the costs of conception for Assisted Conception Procedures (ACPs), subsidizes pregnancy-related healthcare expenses, and provides a Medisave account (Singapore’s national medical savings account) for newborns that can be used for a range of healthcare expenses. Couples undergoing ACPs in public assisted reproduction centers can receive up to 75% in co-funding from the government (Singapore Ministry of Health, 2022 ). The maternity package allows parents to use their Medisave for medical care pre-delivery (e.g., pre-natal consultations, ultrasound scans, tests, medications) and during delivery (e.g., delivery procedure, hospital admission) (Made for Families, 2022b ). A grant is also provided to set up a Medisave account to pay for newborn’s healthcare expenses. The grant amount was S$3000 in 2013–2014 and was subsequently increased to S$4000 for children born on or after 1 January 2015 (Singapore Ministry of Health, 2022 ).

Work–family initiatives include maternity leave, paternity leave, child-related leave, and childcare subsidies. Introduced in 2004, the government-paid maternity leave provides working mothers with 16 weeks of paid maternity leave to support their recovery from childbirth and encourage bonding with their newborns. Government-paid paternity leave was later introduced in 2013, entitling working fathers to 1 week of paid paternity leave and allowing them to share up to one week of their wife’s 16 weeks of maternity leave, subject to her agreement (Singapore Ministry of Social & Family Development, 2013 ). Since 2017, the paternity leave was extended to two weeks for eligible working fathers, including those who are self-employed. In addition, eligible fathers can take up to four weeks of shared parental leave (Singapore Ministry of Manpower, 2020 ). To further support parents with combining work and childcare responsibilities, parents of children enrolled at licensed childcare centers are given subsidies of up to S$600 per month for infant care and up to S$300 per month for daycare. Working parents are also allowed to take up to six days of childcare leave per year if their child is below the age of seven, and up to six days of unpaid infant care leave per year if their child is under the age of two.

Existing policy discussions suggest that the policies have not had a positive impact on fertility. Jones ( 2019 ) argues that financial incentives are ineffective as they only cover less than a third of the total costs of raising a child in Singapore. McDonald and Evans ( 2002 ) posit that cash incentives and subsidies are much less effective than initiatives geared towards mitigating the opportunity cost of having children. However, other than policy discussions (Jones, 2012 , 2019 ), content analysis (Wong & Yeoh, 2003 ), aggregate research (Chen et al., 2018 ; Jones & Hamid, 2015 ), and qualitative studies (Teo, 2010 ; Williams, 2014 ), there is limited empirical evidence on the extent to which Singapore’s pronatalist policy measures contribute to a conducive environment in which couples will choose to have children. Even within the broader literature, little attention has been paid to understanding how intended beneficiaries perceive the utility of policy. Therefore, this study aims to understand the policy perceptions among couples and different sociodemographic subgroups to provide insights into the extent to which pronatalist policies are able to meet the needs of individuals for childbearing in a low-fertility context.

Data and methods

This study used data from the POPS Survey 7: Perceptions of the Marriage and Parenthood Package. Permission for the use of the data was obtained from the Singapore Institute of Policy Studies. The POPS Survey 7 is a nationally representative survey of 2000 married Singaporean citizens and permanent residents aged 21–49. The survey was undertaken to examine the attitudes of married, childbearing-age participants towards policies that support family formation. Single parents and individuals who are divorced, separated, or widowed were excluded from the survey. The data were collected between July and September 2014 via a door-to-door interview method. Participants were selected through a multistage cluster sampling method using a sampling frame obtained from the Singapore Department of Statistics. In line with the 2010 Census, quotas based on sex, ethnicity, and housing type were used to ensure a nationally representative sample. Households were first grouped into reticulate units with 200 households of the same housing type in each unit, then a random sample of 100 units was obtained. Twenty households were selected from the 100 units, and an eligible person from each household was interviewed. In cases where the selected household did not have an eligible participant or when a potential participant refused to participate, an eligible person from a matching dwelling was invited to complete the survey. The respondent profiles are generally representative of Singapore’s married resident population aged 21–49. A comparison of sociodemographic characteristics between the sample and the population can be found in Table 5 of the Appendix. The final sample included all 2000 Singaporean residents.

Dependent variable

The dependent variable is the overall conduciveness of policies for childbearing (“On the whole, has the most recent Marriage and Parenthood Package made it conducive for you and your spouse to have children?”), which was recorded as a binary variable (0 = no , 1 = yes ).

Independent variables

Twelve policy measures were examined, covering both financial incentives and work–family initiatives. The policies include the Baby Bonus, housing schemes and grants, working mother’s child relief, the maternity package, the healthcare grant for newborns, co-funding for ACPs, maternity leave, paternity leave, shared parental leave, extended childcare leave, unpaid infant care leave, and subsidies for center-based infant and childcare (see Table 6 in the Appendix for the list of policies). Participants were asked whether each policy would influence them to have (more) children (0 = no , 1 = yes ).

Control variables

Six key sociodemographic variables, including age, sex, ethnicity, educational attainment, number of children born, and employment status, were included in the analyses. Age was coded into three categories: below 30, 30–39, and above 39. Gender was coded as a binary variable (0 = man , 1 = woman ). Ethnicity included four categories: Chinese (reference group), Malay, Indian, and other ethnicities. Educational attainment was categorized into secondary school education or lower (reference group), diploma and other professional qualifications, and university degree or higher. Number of children was grouped into no children (reference group), one child, two children, and three or more children. Employment status was coded as a binary variable (0 = unemployed , 1 = employed ).

Analytic strategy

Dominance analysis was used to evaluate the relative importance of pronatalist policies in contributing to the overall conduciveness for childbearing at the population level and in stratified subgroups (i.e., by age, sex, and child parity). The analyses are based on a logistic regression model with overall conduciveness as the outcome and the 12 policy measures as predictors, adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics. Dominance analysis is a method of comparing the relative importance and ranking of predictors (i.e., dominance profiles) based on how much each predictor contributes to the total variance of the outcome in a model (Azen & Budescu, 2003 ). Dominance analysis considers both the unique contribution of a predictor and its contribution when combined with other predictors. It is an ensemble approach that estimates all possible regression models and subset models to compare the change in model fit ( R 2 ), quantifying the influence of a predictor when added to all possible subset models with a given set of predictors (Azen & Traxel, 2009 ). Specifically. the dominance analyses in this study consisted of 4095 (2 12 –1) regression models containing all possible combinations of predictors. Dominance analysis has been a popular method used by many researchers and practitioners in recent years to assess the relative contribution of a large set of predictors to a specific outcome (e.g., Gromping, 2007 ; Johnson & Lebreton, 2004 ; Mange et al., 2021 ; Peacock, 2021 ; Vize et al., 2019 ). Stata/SE v15.1 was used to prepare the data and conduct the analyses. Dominance analysis was performed using the community-contributed command domin (Luchman, 2021 ).

Descriptive results

Overall, 40% of respondents reported that the policies were conducive. The majority of those who were aged under 30 (61.93%) were more likely to report that the policies were conducive for them compared to those aged between 30 and 39 (49.35%), and those aged above 39 (27.90%) (see Table 1 ). Men were more likely than women to view the policies as conducive. Approximately half of the proportion of ethnic Indians (50.59%) reported that the policy measures were conducive for them, compared to the ethnic Chinese (36.8%), ethnic Malay (45.11%), and respondents of other ethnicities (47.06%). Respondents who had no children (59.25%) were more likely to report that the policies were conducive for them compared to those with one child (47.44%), two children (32.62%), and three or more children (32.36%). Among parents, those who reported that the policy measures were conducive to parenthood had younger children than those who reported otherwise. On average, the youngest child in the family was eight years old for those who reported that the policies were conducive and 11 years old for those who reported that the policies were less conducive. There was no discernible difference in overall conduciveness across education groups and employment statuses, although there are some variations by occupation and monthly household income. Compared to other occupations, professionals (37.96%), technicians and associate professionals (16.62%), and service and sales workers (17.53%) made up a higher proportion of respondents who reported that the policies were conducive. Those with higher monthly household income (> S$6000) were less likely to view the policies as conducive than those in lower household income categories. In addition, about 41% of respondents in a dual-earner relationship reported that the policies were conducive to childbearing.

Main findings

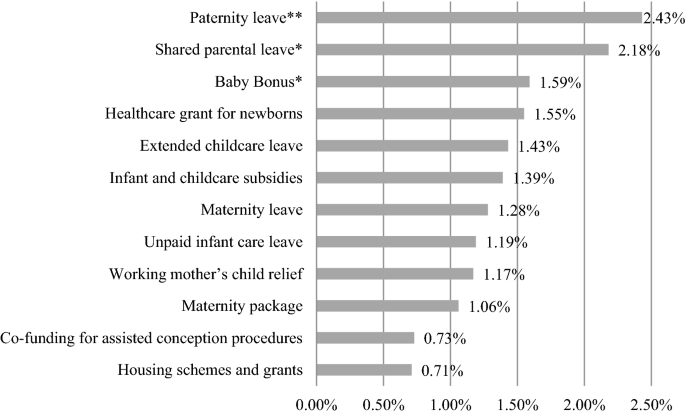

There were three significant policy measures contributing to the conduciveness for childbearing (see Fig. 3 ). Financial incentives and work–family initiatives along with sociodemographic characteristics explained 24% of the variance in the overall conduciveness of policies (see Table 7 in the Appendix for details on the logistic models). The three policy measures explaining most of the variance in the overall conduciveness were paternity leave (2.43%), shared parental leave (2.18%), and Baby Bonus (1.59%) (Fig. 3 ).

Adjusted dominance statistics for all respondents ( N = 2000). Adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, number of children, educational attainment, and employment status. Rank of policy measures based on average increase in total variance explained by the model ( R 2 ) when adding a variable to all possible subset models. * p < .05, ** p < .01

Stratified analyses

Pronatalist policies were more likely to influence the conduciveness for younger Singaporeans to have children compared to their older counterparts (see Table 2 ). In the analyses stratified by age group, the predictors explained 35.04%, 21.96%, and 20.65% of the variance in overall policy conduciveness for those under 30, between 30 and 39, and above 39 respectively. For the younger age group (< 30 years), the most important policy measures were shared parental leave (6.21%), paternity leave (5.25%), and working mother’s child relief (3.26%). For the middle age group (30–39 years), the most relevant policy measures were the healthcare grant for newborns (2%), Baby Bonus (1.94%), and paternity leave (1.91%). For the older age group (> 39 years), the most important policy measures were paternity leave (2.99%), shared parental leave (2.95%), and extended childcare leave (1.75%).