- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Case Study in Education Research

Introduction, general overview and foundational texts of the late 20th century.

- Conceptualisations and Definitions of Case Study

- Case Study and Theoretical Grounding

- Choosing Cases

- Methodology, Method, Genre, or Approach

- Case Study: Quality and Generalizability

- Multiple Case Studies

- Exemplary Case Studies and Example Case Studies

- Criticism, Defense, and Debate around Case Study

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Data Collection in Educational Research

- Mixed Methods Research

- Program Evaluation

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Gender, Power, and Politics in the Academy

- Girls' Education in the Developing World

- Non-Formal & Informal Environmental Education

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Case Study in Education Research by Lorna Hamilton LAST REVIEWED: 21 April 2021 LAST MODIFIED: 27 June 2018 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0201

It is important to distinguish between case study as a teaching methodology and case study as an approach, genre, or method in educational research. The use of case study as teaching method highlights the ways in which the essential qualities of the case—richness of real-world data and lived experiences—can help learners gain insights into a different world and can bring learning to life. The use of case study in this way has been around for about a hundred years or more. Case study use in educational research, meanwhile, emerged particularly strongly in the 1970s and 1980s in the United Kingdom and the United States as a means of harnessing the richness and depth of understanding of individuals, groups, and institutions; their beliefs and perceptions; their interactions; and their challenges and issues. Writers, such as Lawrence Stenhouse, advocated the use of case study as a form that teacher-researchers could use as they focused on the richness and intensity of their own practices. In addition, academic writers and postgraduate students embraced case study as a means of providing structure and depth to educational projects. However, as educational research has developed, so has debate on the quality and usefulness of case study as well as the problems surrounding the lack of generalizability when dealing with single or even multiple cases. The question of how to define and support case study work has formed the basis for innumerable books and discursive articles, starting with Robert Yin’s original book on case study ( Yin 1984 , cited under General Overview and Foundational Texts of the Late 20th Century ) to the myriad authors who attempt to bring something new to the realm of case study in educational research in the 21st century.

This section briefly considers the ways in which case study research has developed over the last forty to fifty years in educational research usage and reflects on whether the field has finally come of age, respected by creators and consumers of research. Case study has its roots in anthropological studies in which a strong ethnographic approach to the study of peoples and culture encouraged researchers to identify and investigate key individuals and groups by trying to understand the lived world of such people from their points of view. Although ethnography has emphasized the role of researcher as immersive and engaged with the lived world of participants via participant observation, evolving approaches to case study in education has been about the richness and depth of understanding that can be gained through involvement in the case by drawing on diverse perspectives and diverse forms of data collection. Embracing case study as a means of entering these lived worlds in educational research projects, was encouraged in the 1970s and 1980s by researchers, such as Lawrence Stenhouse, who provided a helpful impetus for case study work in education ( Stenhouse 1980 ). Stenhouse wrestled with the use of case study as ethnography because ethnographers traditionally had been unfamiliar with the peoples they were investigating, whereas educational researchers often worked in situations that were inherently familiar. Stenhouse also emphasized the need for evidence of rigorous processes and decisions in order to encourage robust practice and accountability to the wider field by allowing others to judge the quality of work through transparency of processes. Yin 1984 , the first book focused wholly on case study in research, gave a brief and basic outline of case study and associated practices. Various authors followed this approach, striving to engage more deeply in the significance of case study in the social sciences. Key among these are Merriam 1988 and Stake 1995 , along with Yin 1984 , who established powerful groundings for case study work. Additionally, evidence of the increasing popularity of case study can be found in a broad range of generic research methods texts, but these often do not have much scope for the extensive discussion of case study found in case study–specific books. Yin’s books and numerous editions provide a developing or evolving notion of case study with more detailed accounts of the possible purposes of case study, followed by Merriam 1988 and Stake 1995 who wrestled with alternative ways of looking at purposes and the positioning of case study within potential disciplinary modes. The authors referenced in this section are often characterized as the foundational authors on this subject and may have published various editions of their work, cited elsewhere in this article, based on their shifting ideas or emphases.

Merriam, S. B. 1988. Case study research in education: A qualitative approach . San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

This is Merriam’s initial text on case study and is eminently accessible. The author establishes and reinforces various key features of case study; demonstrates support for positioning the case within a subject domain, e.g., psychology, sociology, etc.; and further shapes the case according to its purpose or intent.

Stake, R. E. 1995. The art of case study research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Stake is a very readable author, accessible and yet engaging with complex topics. The author establishes his key forms of case study: intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Stake brings the reader through the process of conceptualizing the case, carrying it out, and analyzing the data. The author uses authentic examples to help readers understand and appreciate the nuances of an interpretive approach to case study.

Stenhouse, L. 1980. The study of samples and the study of cases. British Educational Research Journal 6:1–6.

DOI: 10.1080/0141192800060101

A key article in which Stenhouse sets out his stand on case study work. Those interested in the evolution of case study use in educational research should consider this article and the insights given.

Yin, R. K. 1984. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . Beverley Hills, CA: SAGE.

This preliminary text from Yin was very basic. However, it may be of interest in comparison with later books because Yin shows the ways in which case study as an approach or method in research has evolved in relation to detailed discussions of purpose, as well as the practicalities of working through the research process.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Education »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academic Achievement

- Academic Audit for Universities

- Academic Freedom and Tenure in the United States

- Action Research in Education

- Adjuncts in Higher Education in the United States

- Administrator Preparation

- Adolescence

- Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate Courses

- Advocacy and Activism in Early Childhood

- African American Racial Identity and Learning

- Alaska Native Education

- Alternative Certification Programs for Educators

- Alternative Schools

- American Indian Education

- Animals in Environmental Education

- Art Education

- Artificial Intelligence and Learning

- Assessing School Leader Effectiveness

- Assessment, Behavioral

- Assessment, Educational

- Assessment in Early Childhood Education

- Assistive Technology

- Augmented Reality in Education

- Beginning-Teacher Induction

- Bilingual Education and Bilingualism

- Black Undergraduate Women: Critical Race and Gender Perspe...

- Blended Learning

- Case Study in Education Research

- Changing Professional and Academic Identities

- Character Education

- Children’s and Young Adult Literature

- Children's Beliefs about Intelligence

- Children's Rights in Early Childhood Education

- Citizenship Education

- Civic and Social Engagement of Higher Education

- Classroom Learning Environments: Assessing and Investigati...

- Classroom Management

- Coherent Instructional Systems at the School and School Sy...

- College Admissions in the United States

- College Athletics in the United States

- Community Relations

- Comparative Education

- Computer-Assisted Language Learning

- Computer-Based Testing

- Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Evaluating Improvement Net...

- Continuous Improvement and "High Leverage" Educational Pro...

- Counseling in Schools

- Critical Approaches to Gender in Higher Education

- Critical Perspectives on Educational Innovation and Improv...

- Critical Race Theory

- Crossborder and Transnational Higher Education

- Cross-National Research on Continuous Improvement

- Cross-Sector Research on Continuous Learning and Improveme...

- Cultural Diversity in Early Childhood Education

- Culturally Responsive Leadership

- Culturally Responsive Pedagogies

- Culturally Responsive Teacher Education in the United Stat...

- Curriculum Design

- Data-driven Decision Making in the United States

- Deaf Education

- Desegregation and Integration

- Design Thinking and the Learning Sciences: Theoretical, Pr...

- Development, Moral

- Dialogic Pedagogy

- Digital Age Teacher, The

- Digital Citizenship

- Digital Divides

- Disabilities

- Distance Learning

- Distributed Leadership

- Doctoral Education and Training

- Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) in Denmark

- Early Childhood Education and Development in Mexico

- Early Childhood Education in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Childhood Education in Australia

- Early Childhood Education in China

- Early Childhood Education in Europe

- Early Childhood Education in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Early Childhood Education in Sweden

- Early Childhood Education Pedagogy

- Early Childhood Education Policy

- Early Childhood Education, The Arts in

- Early Childhood Mathematics

- Early Childhood Science

- Early Childhood Teacher Education

- Early Childhood Teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Years Professionalism and Professionalization Polici...

- Economics of Education

- Education For Children with Autism

- Education for Sustainable Development

- Education Leadership, Empirical Perspectives in

- Education of Native Hawaiian Students

- Education Reform and School Change

- Educational Statistics for Longitudinal Research

- Educator Partnerships with Parents and Families with a Foc...

- Emotional and Affective Issues in Environmental and Sustai...

- Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

- Environmental and Science Education: Overlaps and Issues

- Environmental Education

- Environmental Education in Brazil

- Epistemic Beliefs

- Equity and Improvement: Engaging Communities in Educationa...

- Equity, Ethnicity, Diversity, and Excellence in Education

- Ethical Research with Young Children

- Ethics and Education

- Ethics of Teaching

- Ethnic Studies

- Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention

- Family and Community Partnerships in Education

- Family Day Care

- Federal Government Programs and Issues

- Feminization of Labor in Academia

- Finance, Education

- Financial Aid

- Formative Assessment

- Future-Focused Education

- Gender and Achievement

- Gender and Alternative Education

- Gender-Based Violence on University Campuses

- Gifted Education

- Global Mindedness and Global Citizenship Education

- Global University Rankings

- Governance, Education

- Grounded Theory

- Growth of Effective Mental Health Services in Schools in t...

- Higher Education and Globalization

- Higher Education and the Developing World

- Higher Education Faculty Characteristics and Trends in the...

- Higher Education Finance

- Higher Education Governance

- Higher Education Graduate Outcomes and Destinations

- Higher Education in Africa

- Higher Education in China

- Higher Education in Latin America

- Higher Education in the United States, Historical Evolutio...

- Higher Education, International Issues in

- Higher Education Management

- Higher Education Policy

- Higher Education Research

- Higher Education Student Assessment

- High-stakes Testing

- History of Early Childhood Education in the United States

- History of Education in the United States

- History of Technology Integration in Education

- Homeschooling

- Inclusion in Early Childhood: Difference, Disability, and ...

- Inclusive Education

- Indigenous Education in a Global Context

- Indigenous Learning Environments

- Indigenous Students in Higher Education in the United Stat...

- Infant and Toddler Pedagogy

- Inservice Teacher Education

- Integrating Art across the Curriculum

- Intelligence

- Intensive Interventions for Children and Adolescents with ...

- International Perspectives on Academic Freedom

- Intersectionality and Education

- Knowledge Development in Early Childhood

- Leadership Development, Coaching and Feedback for

- Leadership in Early Childhood Education

- Leadership Training with an Emphasis on the United States

- Learning Analytics in Higher Education

- Learning Difficulties

- Learning, Lifelong

- Learning, Multimedia

- Learning Strategies

- Legal Matters and Education Law

- LGBT Youth in Schools

- Linguistic Diversity

- Linguistically Inclusive Pedagogy

- Literacy Development and Language Acquisition

- Literature Reviews

- Mathematics Identity

- Mathematics Instruction and Interventions for Students wit...

- Mathematics Teacher Education

- Measurement for Improvement in Education

- Measurement in Education in the United States

- Meta-Analysis and Research Synthesis in Education

- Methodological Approaches for Impact Evaluation in Educati...

- Methodologies for Conducting Education Research

- Mindfulness, Learning, and Education

- Motherscholars

- Multiliteracies in Early Childhood Education

- Multiple Documents Literacy: Theory, Research, and Applica...

- Multivariate Research Methodology

- Museums, Education, and Curriculum

- Music Education

- Narrative Research in Education

- Native American Studies

- Note-Taking

- Numeracy Education

- One-to-One Technology in the K-12 Classroom

- Online Education

- Open Education

- Organizing for Continuous Improvement in Education

- Organizing Schools for the Inclusion of Students with Disa...

- Outdoor Play and Learning

- Outdoor Play and Learning in Early Childhood Education

- Pedagogical Leadership

- Pedagogy of Teacher Education, A

- Performance Objectives and Measurement

- Performance-based Research Assessment in Higher Education

- Performance-based Research Funding

- Phenomenology in Educational Research

- Philosophy of Education

- Physical Education

- Podcasts in Education

- Policy Context of United States Educational Innovation and...

- Politics of Education

- Portable Technology Use in Special Education Programs and ...

- Post-humanism and Environmental Education

- Pre-Service Teacher Education

- Problem Solving

- Productivity and Higher Education

- Professional Development

- Professional Learning Communities

- Programs and Services for Students with Emotional or Behav...

- Psychology Learning and Teaching

- Psychometric Issues in the Assessment of English Language ...

- Qualitative Data Analysis Techniques

- Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research Samp...

- Qualitative Research Design

- Quantitative Research Designs in Educational Research

- Queering the English Language Arts (ELA) Writing Classroom

- Race and Affirmative Action in Higher Education

- Reading Education

- Refugee and New Immigrant Learners

- Relational and Developmental Trauma and Schools

- Relational Pedagogies in Early Childhood Education

- Reliability in Educational Assessments

- Religion in Elementary and Secondary Education in the Unit...

- Researcher Development and Skills Training within the Cont...

- Research-Practice Partnerships in Education within the Uni...

- Response to Intervention

- Restorative Practices

- Risky Play in Early Childhood Education

- Scale and Sustainability of Education Innovation and Impro...

- Scaling Up Research-based Educational Practices

- School Accreditation

- School Choice

- School Culture

- School District Budgeting and Financial Management in the ...

- School Improvement through Inclusive Education

- School Reform

- Schools, Private and Independent

- School-Wide Positive Behavior Support

- Science Education

- Secondary to Postsecondary Transition Issues

- Self-Regulated Learning

- Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices

- Service-Learning

- Severe Disabilities

- Single Salary Schedule

- Single-sex Education

- Single-Subject Research Design

- Social Context of Education

- Social Justice

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Pedagogy

- Social Science and Education Research

- Social Studies Education

- Sociology of Education

- Standards-Based Education

- Statistical Assumptions

- Student Access, Equity, and Diversity in Higher Education

- Student Assignment Policy

- Student Engagement in Tertiary Education

- Student Learning, Development, Engagement, and Motivation ...

- Student Participation

- Student Voice in Teacher Development

- Sustainability Education in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Higher Education

- Teacher Beliefs and Epistemologies

- Teacher Collaboration in School Improvement

- Teacher Evaluation and Teacher Effectiveness

- Teacher Preparation

- Teacher Training and Development

- Teacher Unions and Associations

- Teacher-Student Relationships

- Teaching Critical Thinking

- Technologies, Teaching, and Learning in Higher Education

- Technology Education in Early Childhood

- Technology, Educational

- Technology-based Assessment

- The Bologna Process

- The Regulation of Standards in Higher Education

- Theories of Educational Leadership

- Three Conceptions of Literacy: Media, Narrative, and Gamin...

- Tracking and Detracking

- Traditions of Quality Improvement in Education

- Transformative Learning

- Transitions in Early Childhood Education

- Tribally Controlled Colleges and Universities in the Unite...

- Understanding the Psycho-Social Dimensions of Schools and ...

- University Faculty Roles and Responsibilities in the Unite...

- Using Ethnography in Educational Research

- Value of Higher Education for Students and Other Stakehold...

- Virtual Learning Environments

- Vocational and Technical Education

- Wellness and Well-Being in Education

- Women's and Gender Studies

- Young Children and Spirituality

- Young Children's Learning Dispositions

- Young Children's Working Theories

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.80.149.115]

- 185.80.149.115

Text for Mobile

What is the Impact and Importance of Case Study in Education?

Before we explain the significance of case study in education these days for high education, let us explain the first, ‘What is a case study? However, it consists of three major parts that you need to consider for writing. Starting with a problem, outline different available solutions, and offer proven results exhibits that the product or service is an optimum solution for the problem.

What is a Case Study in Education?

Well, a case study is a method of research regarding any specific questions, which allows a person to investigate why and how it happens. Based on education, a case study is that who can use the research for many purposes. It lets the student describe various factors and interaction with each other in authentic contexts. It offers multiple learning opportunities and experiences for scholars by influencing the diverse practice of theories.

Importance of Case Study in Education

It is also considered the source of valuable data regarding diversity and complexity of educational commitments and settings. It plays a vital role in putting theories into regular practice. It is always necessary for the student to realize the clarity in nature and focus of the case study. Considering the significance, Casestudyhelp.com brings the best Case Study Help Any Academic Level for students exerting for acquiring top grades.

What are the Advantages of Case Studies in Class ?

Case studies are assigned to higher classes students, which proved very beneficial to the students, especially in the classroom. Students can actively engage in the discovery of the principles by conceptualizing from the examples. Furthermore, they develop skills like

- Problem-solving

- Coping with ambiguities

- Analytical/ quantitative/qualitative tools according to the case and

- Decision making in complex situations

Method of a Writing Case Study at Casestudyhelp.com!

When teachers give students a Case Study Topic by a teacher, they have to attack each case with the following checklist or go for best and reasonable Case Study Help for Any Topic at casestudyhelp.com!

- Thoroughly read the case and formulate own opinions before sharing ideas with others in the class. You must identify the problems on your own, and offer solutions and best alternatives alongside. Before the study converses, you need to form your own outline and course of action.

- Focus on the three major parts of a case study considering the starting with a problem, outline different accessible solutions, offer predictable results that exhibit the product/service is an optimal solution for the problem.

- Prepare to engage in data collection, collecting data in the field, carry out data evaluation and analysis to write the report.

If you want to save your crucial time for in-depth academic studies, hire our Case study research writers competent with all categories of analysis to write excellent category case studies.

Case Study Help is one of the best academic assistance providers with a team of Experts. We deliver a range of analysis help at a pocket -friendly price. For any category of writing and at any academic level, contact us now!

- Our Mission

Making Learning Relevant With Case Studies

The open-ended problems presented in case studies give students work that feels connected to their lives.

To prepare students for jobs that haven’t been created yet, we need to teach them how to be great problem solvers so that they’ll be ready for anything. One way to do this is by teaching content and skills using real-world case studies, a learning model that’s focused on reflection during the problem-solving process. It’s similar to project-based learning, but PBL is more focused on students creating a product.

Case studies have been used for years by businesses, law and medical schools, physicians on rounds, and artists critiquing work. Like other forms of problem-based learning, case studies can be accessible for every age group, both in one subject and in interdisciplinary work.

You can get started with case studies by tackling relatable questions like these with your students:

- How can we limit food waste in the cafeteria?

- How can we get our school to recycle and compost waste? (Or, if you want to be more complex, how can our school reduce its carbon footprint?)

- How can we improve school attendance?

- How can we reduce the number of people who get sick at school during cold and flu season?

Addressing questions like these leads students to identify topics they need to learn more about. In researching the first question, for example, students may see that they need to research food chains and nutrition. Students often ask, reasonably, why they need to learn something, or when they’ll use their knowledge in the future. Learning is most successful for students when the content and skills they’re studying are relevant, and case studies offer one way to create that sense of relevance.

Teaching With Case Studies

Ultimately, a case study is simply an interesting problem with many correct answers. What does case study work look like in classrooms? Teachers generally start by having students read the case or watch a video that summarizes the case. Students then work in small groups or individually to solve the case study. Teachers set milestones defining what students should accomplish to help them manage their time.

During the case study learning process, student assessment of learning should be focused on reflection. Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick’s Learning and Leading With Habits of Mind gives several examples of what this reflection can look like in a classroom:

Journaling: At the end of each work period, have students write an entry summarizing what they worked on, what worked well, what didn’t, and why. Sentence starters and clear rubrics or guidelines will help students be successful. At the end of a case study project, as Costa and Kallick write, it’s helpful to have students “select significant learnings, envision how they could apply these learnings to future situations, and commit to an action plan to consciously modify their behaviors.”

Interviews: While working on a case study, students can interview each other about their progress and learning. Teachers can interview students individually or in small groups to assess their learning process and their progress.

Student discussion: Discussions can be unstructured—students can talk about what they worked on that day in a think-pair-share or as a full class—or structured, using Socratic seminars or fishbowl discussions. If your class is tackling a case study in small groups, create a second set of small groups with a representative from each of the case study groups so that the groups can share their learning.

4 Tips for Setting Up a Case Study

1. Identify a problem to investigate: This should be something accessible and relevant to students’ lives. The problem should also be challenging and complex enough to yield multiple solutions with many layers.

2. Give context: Think of this step as a movie preview or book summary. Hook the learners to help them understand just enough about the problem to want to learn more.

3. Have a clear rubric: Giving structure to your definition of quality group work and products will lead to stronger end products. You may be able to have your learners help build these definitions.

4. Provide structures for presenting solutions: The amount of scaffolding you build in depends on your students’ skill level and development. A case study product can be something like several pieces of evidence of students collaborating to solve the case study, and ultimately presenting their solution with a detailed slide deck or an essay—you can scaffold this by providing specified headings for the sections of the essay.

Problem-Based Teaching Resources

There are many high-quality, peer-reviewed resources that are open source and easily accessible online.

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science at the University at Buffalo built an online collection of more than 800 cases that cover topics ranging from biochemistry to economics. There are resources for middle and high school students.

- Models of Excellence , a project maintained by EL Education and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has examples of great problem- and project-based tasks—and corresponding exemplary student work—for grades pre-K to 12.

- The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning at Purdue University is an open-source journal that publishes examples of problem-based learning in K–12 and post-secondary classrooms.

- The Tech Edvocate has a list of websites and tools related to problem-based learning.

In their book Problems as Possibilities , Linda Torp and Sara Sage write that at the elementary school level, students particularly appreciate how they feel that they are taken seriously when solving case studies. At the middle school level, “researchers stress the importance of relating middle school curriculum to issues of student concern and interest.” And high schoolers, they write, find the case study method “beneficial in preparing them for their future.”

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Using Case Study in Education Research

- Lorna Hamilton - University of Edinburgh, UK

- Connie Corbett-Whittier - Friends University, Topeka, Kansas

- Description

This book provides an accessible introduction to using case studies. It makes sense of literature in this area, and shows how to generate collaborations and communicate findings.

The authors bring together the practical and the theoretical, enabling readers to build expertise on the principles and practice of case study research, as well as engaging with possible theoretical frameworks. They also highlight the place of case study as a key component of educational research.

With the help of this book, graduate students, teacher educators and practitioner researchers will gain the confidence and skills needed to design and conduct a high quality case study.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

'Drawing on a wide range of their own and others' experiences, the authors offer a comprehensive and convincing account of the value of case study in educational research. What comes across - quite passionately - is the way in which a case study approach can bring to life some of the complexities, challenges and contradictions inherent in educational settings. The book is written in a clear and lively manner and should be an invaluable resource for those teachers and students who are incorporating a case study dimension into their research work' - Ian Menter, Professor of Teacher Education, University of Oxford

'This book is comprehensive in its coverage, yet detailed in its exposition of case study research. It is a highly interactive text with a critical edge and is a useful tool for teaching. It is of particular relevance to practitioner researchers, providing accessible guidance for reflective practice. It covers key matters such as: purposes, ethics, data analysis, technology, dissemination and communities for research. And it is a good read!' - Professor Anne Campbell, formerly of Leeds Metropolitan University

'This excellent book is a principled and theoretically informed guide to case study research design and methods for the collection, analysis and presentation of evidence' -Professor Andrew Pollard, Institute of Educaiton, University of London

This publication provides easy text, giving differing viewpoints to establish definitions for case study research. This book has been recommended to the Fd students to support projects of action research.

This has again been recommended for students on the Foundation Degree and Degree programmes as it is an easy text, providing differing viewpoints to establish definitions for case study research. Additionally recommended on the reading list for the BA programmes to provide a clearer insight into using Case Studies in preschool and school environments.

This is an excellent book - very clear

This text clearly discusses the case study approach and would be useful for both undergraduate and post graduate learners.

An easily accessible text, giving alternative points of view on what case study research actually is and how it might be interpreted at doctoral level.

This is a pleasant read with a number of useful group and individual tasks for students to engage with as they think through designing and doing a project. These tasks for useful not just for case studies but can be adapted as students consider other research designs.

Offers a good understanding of case study research in a clear and accessible manner. A perfect starting point for the researcher new to the case study method and will also offer the experienced researcher some useful tips and insights.

This text is clearly written and argues strongly for using case study in educational research, despite the challenges this approach faces in the dynamic world of shifting research paradigms. Step-by-step guidance from initial ideas through to the reality of undertaking case study in educational research is helpful

The book is written in a practical way, which gives a clear guide for undergraduate students especially for those who are using case study in education research. I will definitely add this book to recommended reading lists.

Preview this book

Sample materials & chapters.

Additional Resource 1

Additional Resource 2

Sample Chapter - Chapter 1

Activity 6.12 Observation 1 p98

Activity 6.12 Observation 2 p98

Activity 6.12 Observation 3 p98

Activity 6.18 Interview pupils

Activity 6.18 Interview schedule 1

Activity 6.19 and 6.20 Questionnaire P110

Activity 6.20 Questionnaire 2 p110

Activity 6.21 Sample interview teachers

For instructors

Select a purchasing option, related products.

This title is also available on SAGE Research Methods , the ultimate digital methods library. If your library doesn’t have access, ask your librarian to start a trial .

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What the Case Study Method Really Teaches

- Nitin Nohria

Seven meta-skills that stick even if the cases fade from memory.

It’s been 100 years since Harvard Business School began using the case study method. Beyond teaching specific subject matter, the case study method excels in instilling meta-skills in students. This article explains the importance of seven such skills: preparation, discernment, bias recognition, judgement, collaboration, curiosity, and self-confidence.

During my decade as dean of Harvard Business School, I spent hundreds of hours talking with our alumni. To enliven these conversations, I relied on a favorite question: “What was the most important thing you learned from your time in our MBA program?”

- Nitin Nohria is the George F. Baker Jr. Professor at Harvard Business School and the former dean of HBS.

Partner Center

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

The Importance of Case Study Research in Educational Settings

- Şenay Ozan Leymun

- Hatice Ferhan Odabaşı

- Işıl Kabakçı Yurdakul

Case study is a research method which is used to answer how and why questions regarding an issue to be investigated, with no researcher control over variables and when the case is current. There are many factors that affect the phenomenon in the studied case, these factors and their interactions are described by the case study. It is a fact that case study can be used for many purposes in educational research because it enables the capacity to describe a lot of factors and their interact with each other in real contexts. Case studies offer an opportunity to learn from experiences and influence the practice of theories. Case studies are valuable data sources for researchers in view of the complexity and diversity of educational settings and purposes. Case study research has an important role in putting theories into practice, thus developing the practice in the field of educational sciences. In this regard, it is important that the nature and the focus of the case study is clear. The aim of this study is to explain the focus and nature of the case study research method to investigate its importance in educational settings and to offer suggestions for practice to researchers.

- PDF (Türkçe)

How to Cite

- Endnote/Zotero/Mendeley (RIS)

Most read articles by the same author(s)

- Mehmet Fırat, Işıl Kabakçı Yurdakul, Ali Ersoy, Mixed Method Research Experience Based on an Educational Technology Study , Journal of Qualitative Research in Education : Vol. 2 Issue 1 (2014): Journal of Qualitative Research in Education

- Bulent ALAN, Hanmyrat SARIYEV, Hatice Ferhan ODABASI, Critical Friendship in Self-Study , Journal of Qualitative Research in Education : Issue 25 (2021): Journal of Qualitative Research in Education

Similar Articles

- Gül ÖZÜDOĞRU, Hüseyin ŞİMŞEK, A Qualitative Research on Competency- Based Learning Management System and Its Effectiveness , Journal of Qualitative Research in Education : Issue 27 (2021): Journal of Qualitative Research in Education

- Sevcan YAGAN, Beyza Yalkılıç, Pre–School Teachers ‘Views And Practices About Sexual Development And Education: A Case Study Design , Journal of Qualitative Research in Education : Issue 34 (2023): Journal of Qualitative Research in Education

- Merve Gangal, Yasin Öztürk, Undesired Behaviours in Preschool Classrooms and the ways for Coping with these Behaviours , Journal of Qualitative Research in Education : Vol. 7 Issue 3 (2019): Journal of Qualitative Research in Education

- Mehmet Ali Tastan, Filiz Bezci, Bullying from the Perspective of Multigrade Classroom Teachers , Journal of Qualitative Research in Education : Issue 34 (2023): Journal of Qualitative Research in Education

- Nese Askar, Mine Canan Durmusoglu, Meaning of Play with Loose Parts Materials in Preschool Education: A Case Study , Journal of Qualitative Research in Education : Issue 33 (2023): Journal of Qualitative Research in Education

- Ekrem CENGİZ, İkrametin DASDEMİR, The Thoughts of School Directors About Distance Education and Their Work in This Process , Journal of Qualitative Research in Education : Issue 31 (2022): Journal of Qualitative Research in Education

You may also start an advanced similarity search for this article.

Make a Submission

Information.

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

Announcements

About article topics.

Thank you for your great interest in the Journal of Qualitative Research in Education (Eğitimde Nitel Araştırmalar Dergisi - ENAD). We have decided not to publish studies on certain subjects as of the 2021 publication year. These topics are:

1. Studies on metaphor only. 2. Studies presented only by digitizing data. 3. Studies whose data sources are documents (thesis, article, document, etc.) and presented with quantitative content analysis. 4. Studies presented from a quantitative perspective.

Please review the Author's Guide before submitting your candidate article.

KAPAK VE LOGO

- Experiences of Prejudice, Stereotype, and Discrimination Exposure of Secondary School Students 145

- Sexuality of Individuals with Intellectual disabilities from Siblings’ Perspective: A Phenomenological Study 129

- Qualitative Data Analysis and Fundamental Principles 121

- Academic Reading in Graduate Students: Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis 102

- The Highest Levels of Maslow’s Hierarchical Needs: Self-actualization and Self-transcendence 99

Journal of Qualitative Research in Education on this website is open access for supporting academicians and researchers, studies. Any issues of Journal of Qualitative Research in Education (ENAD) -published or to be published, partly or as a whoe- may not be downloaded, reproduced, distrubuted, sold or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage retrieval system, without permission from ANI PUBLISHING LTD. CO. Otherwise, legal action will be taken in accordance with the Law on Intellectual and Artistic Works Law No. 5846. Anı Publishing reserves the right to file a lawsuit in any case.

©ENAD Online, www.enadonline.com

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Med Educ Curric Dev

- v.3; Jan-Dec 2016

Case-Based Learning and its Application in Medical and Health-Care Fields: A Review of Worldwide Literature

Susan f. mclean.

Department of Surgery, Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center El Paso, El Paso, TX, USA.

Introduction

Case-based learning (CBL) is a newer modality of teaching healthcare. In order to evaluate how CBL is currently used, a literature search and review was completed.

A literature search was completed using an OVID© database using PubMed as the data source, 1946-8/1/2015. Key words used were “Case-based learning” and “medical education”, and 360 articles were retrieved. Of these, 70 articles were selected to review for location, human health care related fields of study, number of students, topics, delivery methods, and student level.

All major continents had studies on CBL. Education levels were 64% undergraduate and 34% graduate. Medicine was the most frequently represented field, with articles on nursing, occupational therapy, allied health, child development and dentistry. Mean number of students per study was 214 (7–3105). The top 3 most common methods of delivery were live presentation in 49%, followed by computer or web-based in 20% followed by mixed modalities in 19%. The top 3 outcome evaluations were: survey of participants, knowledge test, and test plus survey, with practice outcomes less frequent. Selected studies were reviewed in greater detail, highlighting advantages and disadvantages of CBL, comparisons to Problem-based learning, variety of fields in healthcare, variety in student experience, curriculum implementation, and finally impact on patient care.

Conclusions

CBL is a teaching tool used in a variety of medical fields using human cases to impart relevance and aid in connecting theory to practice. The impact of CBL can reach from simple knowledge gains to changing patient care outcomes.

Medical and health care-related education is currently changing. Since the advent of adult education, educators have realized that learners need to see the relevance and be actively engaged in the topic under study. 1 Traditionally, students in health care went to lectures and then transitioned into patient care as a type of on-the-job training. Medical schools have realized the importance of including clinical work early and have termed the mixing of basic and clinical sciences as vertical integration. 2 Other human health-related fields have also recognized the value of illustrating teaching points with actual cases or simulated cases. Using clinical cases to aid teaching has been termed as case-based learning (CBL).

There is not a set definition for CBL. An excellent definition has been proposed by Thistlewaite et al in a review article. In their 2012 paper, a CBL definition is “The goal of CBL is to prepare students for clinical practice, through the use of authentic clinical cases. It links theory to practice, through the application of knowledge to the cases, using inquiry-based learning methods”. 3

Others have defined CBL by comparing CBL to a similar yet distinct clinical integration teaching method, problem-based learning (PBL). PBL sessions typically used one patient and had very little direction to the discussion of the case. The learning occurred as the case unfolded, with students having little advance preparation and often researching during the case. Srinivasan et al compared CBL with PBL 4 and noted that in PBL the student had little advance preparation and very little guidance during the case discussion. However, in CBL, both the student and faculty prepare in advance, and there is guidance to the discussion so that important learning points are covered. In a survey of students and faculty after a United States medical school switched from PBL to CBL, students reported that they enjoyed CBL better because there were fewer unfocused tangents. 4

CBL is currently used in multiple health-care settings around the world. In order to evaluate what is now considered CBL, current uses of CBL, and evaluation strategies of CBL-based curricular elements, a literature review was completed.

This review will focus on human health-related applications of CBL-type learning. A summary of articles reviewed is presented with respect to fields of study, delivery options for CBL, locations of study, outcomes measurement if any, number of learners, and level of learner's education. These findings will be discussed. The rest of this review will focus on expanding on the article summary by describing in more detail the publications that reported on CBL. The review is organized into definitions of CBL, comparison of CBL with PBL, and the advantages of using CBL. The review will also examine the utility and usage of CBL with respect to various fields and levels of learner, as well as the methods of implementation of CBL in curricula. Finally, the impact of CBL training on patient and health-care outcomes will be reviewed. One wonders with the proliferation of articles that have CBL in the title, whether or not there has been literature defining exactly what CBL is, how it is used, and whether or not there are any advantages to using CBL over other teaching strategies. The rationale for completing this review is to assess CBL as a discrete mode of transmitting medical and related fields of knowledge. A systematic review of how CBL is accomplished, including successes and failures in reports of CBL in real curricula, would aid other teachers of medical knowledge in the future. Examining the current use of CBL would improve the current methodology of CBL. Therefore, the aims of this review are to discover how widespread the use of CBL is globally, identify current definitions of CBL, compare CBL with PBL, review educational levels of learners, compare methods of implementation of CBL in curricula, and review CBL reports on outcomes of learning.

A literature search was completed using an OVID© database search with PubMed as the database, 1946 to August 1, 2015. The search key words were “Case Based Learning, Medical Education”. Investigational Review Board declined to review this project as there were no human subjects involved and this was an article review. A total of 360 articles were retrieved. Articles were excluded for the following reasons: unable to find complete article on the search engine OVID, unable to find English language translation, article did not really describe CBL, article was not medically or health related, or article did not describe human beings. Articles that originated in another language but had English language translation were included.

After excluding the articles as described, 70 of these articles were selected to review for location of study, description of CBL used, human health care-related fields of study, number of students if available, topics of study, method of delivery, and level of student (eg, graduate or undergraduate). Students were considered undergraduate if they were considered undergraduate in their field. For example, medical students were considered undergraduate, because they would still have to undergo more training to become fully able to practice. If the student was in the terminal degree, then that was considered a study of graduate students. For example, nutrition students were listed as graduate students. CBL encounters for both residents and independent practitioners who were in their final training prior to practice were listed as graduates. Residents were listed under graduate medical education. If a group had already graduated, they were listed as graduates. For example, MDs who participated in a continuing medical education (CME)-type CBL were listed as graduate type of student. Articles that did not list the total number of students were included, as one of the purposes of this review was to discover how widespread the use of CBL was globally, and what types of students and types of delivery were used. By including descriptive articles that were not specific, the global use of CBL could attempt to be assessed. Including locations of studies would then help decide whether CBL was isolated from the Western countries or has it truly spread around the world.

In order to review how CBL was used, in addition to where it was used, the method of delivery was assessed. Method of delivery refers to how the total educational content was delivered. Articles were reviewed for description of exactly how material was imparted to learners. Since many authors described their learning methods in detail, an attempt was undertaken to classify these methods. Method of delivery was classified as follows: live was considered a live presentation of the case, this could be a description, a patient, or a simulated patient. Computer or web based meant that the case and content were web based. Mixed modalities meant that more than two modalities were used during presentation. For example, if an article described assigned reading, lectures, small group discussions, a live case-based session, and patient interactions, then that article would be described as mixed modalities.

Method of evaluation of the educational intervention was also reviewed. The multiple ways in which the interventions were evaluated varied. A survey of how the learners viewed the intervention was frequent. Tests of knowledge gained were frequent, and these ranged from written, to oral, to Observed Skills Clinical Examination (OSCE). Another way by which CBL intervention knowledge was evaluated was review of practice behavior in clinicians. These multiple ways to evaluate the introduction of CBL into a curriculum are summarized in a table.

Results are presented in simple frequencies and percentages. SPSS (Statistical Program for the Social Sciences, IBM) version 22 was used for analysis.

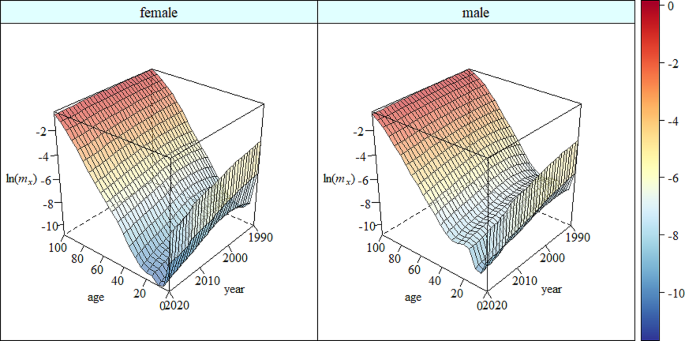

All continuously inhabited continents had studies on CBL ( Fig. 1 ). North America is represented with the most with 54.9% of articles, followed by Europe (25.4%) and Asia, including India, Australia, and New Zealand (15.5%). South America had 2.8% and Africa had 1%. 5 – , 75

CBL use worldwide.

Level of education was undergraduation in 45 (64%) articles and graduation in 24 (34%) articles, with one article having both levels. One study with both faculty and residents was considered as a type of graduate education. The types of fields of study varied ( Fig. 2 ). The most represented field was medicine including traditional Chinese medicine, with articles also on nursing, occupational therapy, allied health, child development, and dentistry. The number of students ranged from 7 to 3105 and the mean number of students was 214. One study reported on the use of teams of critical care personnel, in which it was mentioned that there were three persons per team usually. Thus, the number of students was multiplied: 40 teams x 3 = 120 in total. The total number of students were 9884 from the 46 papers that explicitly stated the number of students.

Fields of study.

Methods of delivery also varied ( Fig. 3 ). The most common method of delivery was live presentation (49%), followed by computer or web based (20%) and then mixed modalities (19%). Method of evaluation or outcomes was studied ( Fig. 4 ). Survey (36%), test (17%), and test plus survey (16%) were the top three methods of evaluation of a CBL learning session. Lesser in frequency was review of practice behavior (9%), test plus OSCE (9%), and others. Review of practice behavior could include reviewing prescription writing, or in one case reviewing the number of adverse drug events reported spontaneously in Portugal. 65

Mode of delivery of CBL.

Method of evaluation.

Discussion and Review

CBL is used worldwide. There was a large variety of fields of medicine. The numbers reported included a wide range of number of learners. Some studies were descriptive, and it was hard to know exactly how many students were involved. This problem was noted in another recent review. 3 CBL was used in various educational levels, from undergraduate to graduate. The number of students ranged from very small studies of 7 students to over 3000 students. The media used to deliver a CBL session varied, from several live forms to paper and pencil or internet-based media. The outcomes measurement to review if CBL sessions were successful ranged from surveys of participants to knowledge tests to measures of patient outcomes. In order to further analyze the worldwide use of CBL, the articles are reviewed below in more detail.

Definition of CBL

CBL has been used in medical fields since at least 1912, when it was used by Dr. James Lorrain Smith while teaching pathology in 1912 at the University of Edinburgh. 63 , 68 Thistlewaite et al 3 pointed out in a recent review of CBL that “There is no international consensus as to the definition of case-based learning (CBL) though it is contrasted to problem based learning (PBL) in terms of structure. We conclude that CBL is a form of inquiry based learning and fits on the continuum between structured and guided learning.” They offer a definition of CBL: “The goal of CBL is to prepare students for clinical practice, through the use of authentic clinical cases. It links theory to practice, through the application of knowledge to the cases, using inquiry-based learning methods.” 3

Another pathology article from Africa, describing a course in laboratory medicine for mixed graduate medical education (residents) and CME for clinicians, defines CBL: “Case-based learning is structured so that trainees explore clinically relevant topics using open-ended questions with well-defined goals.” 7 The exploring that students or trainees do factors into other definitions. In a dental education article originating in Turkey, the authors remark: “The advantages of the case-based method are promotion of self-directed learning, clinical reasoning, clinical problem solving, and decision making by providing repeated experiences in class and by enabling students to focus on the complexity of clinical care.” 8 Another definition of CBL was offered in a physiology education paper regarding teaching undergraduate medical students in India: “What is CBL? By discussing a clinical case related to the topic taught, students evaluated their own understanding of the concept using a high order of cognition. This process encourages active learning and produces a more productive outcome.” 13 In an article published in 2008, regarding teaching graduate pharmacology students, CBL was defined as “Case-based learning (CBL) is an active-learning strategy, much like problem-based learning, involving small groups in which the group focuses on solving a presented problem.” 45 Another study, which was from China regarding teaching undergraduate medical student's pharmacology, describes CBL as “CBL is a long-established pedagogical method that focuses on case study teaching and inquiry-based learning: thus, CBL is on the continuum between structured and guided learning.” 63 It is apparent that the definition requires at least: (1) a clinical case, (2) some kind of inquiry on the part of the learner, which is all of the information to be learned, is not presented at first, (3) enough information presented so that there is not too much time spent learning basics, and (4) a faculty teaching and guiding the discussion, ensuring that learning objectives are met. In most studies, CBL is not presented as free inquiry. The inquiry may be a problem or question. Based on the fact that a problem is expected to be solved or question answered, the information covered cannot be completely new, or the new information must be presented alongside the case.

A modern definition of CBL is that CBL is a form of learning, which involves a clinical case, a problem or question to be solved, and a stated set of learning objectives with a measured outcome. Included in this definition is that some, but not all, of the information is presented prior to or during the learning intervention, and some of the information is discovered during the problem solving or question answering. The learner acquires some of the learning objectives during the CBL session, whether it is live, web based, or on paper. In contrast, if all of the information were given prior or during the session, without the need for inquiry, then the session would just be a lecture or reading.

Comparison of CBL and PBL

CBL is not the first and only method of inquiry-based education. PBL is similar, with distinct differences ( Fig. 5 ). In many papers, CBL is compared and contrasted with PBL in order to define CBL better. PBL is also centered around a clinical case. Often the objectives are less clearly defined at the outset of the learning session, and learning occurs in the course of solving the problem. There is a teacher, but the teacher is less intrusive with the guidance than in CBL. One comparison of CBL to PBL was described in an article on Turkish dental school education: “… CBL is effective for students who have already acquired foundational knowledge, whereas PBL invites the student to learn foundational knowledge as part of researching the clinical case.” Study, of postgraduate education in an American Obstetrics and Gynecology residency, describes CBL as “CBL is a variant of PBL and involves a case vignette that is designed to reflect the educational objectives of a particular topic.” 54 In an overview of CBL and PBL in a dental education article from the United States, the authors note that the main focus of PBL is on the cases and CBL is more flexible in its use of clinical material. 16 The authors quote Donner and Bickley, 70 stating that PBL is “… a form of education in which information is mastered in the same context in which it will be used … PBL is seen as a student-driven process in which the student sets the pace, and the role of the teacher becomes one of guide, facilitator, and resource … (p294).” The authors note that where PBL has the student as the driver , in CBL the teachers are the drivers of education, guiding and directing the learning much more than in PBL. 16 The authors also note that there has not been conclusive evidence that PBL is better than traditional lecture-based learning (LBL) and has been noted to cover less material, some say 80% of a curriculum. 71 It is apparent that PBL has been used to aid case-related teaching in medical fields.

Differences in CBL and PBL.

Two studies highlight the advantages and disadvantages of CBL compared with PBL. Both studies report on major curriculum shifts at three major medical schools. The first study, published in 2005, reported on the performance outcomes during the third-year clerkship rotations at Southern Illinois University (SIU). 19 At SIU, during the 1994–2002 school years, there was both a standard (STND) and PBL learning tract offered for the preclinical years, years 1–2. During the PBL tract, basics of medicine were taught in small group tutoring sessions using PBL modules and standardized patients. In addition, there was a weekly live clinical session. The two tracts were compared over all those years with respect to United States Medical Licensing Exam© (USMLE) test performance on Steps 1 and 2, and also overall grades and subcategories on the six third-year clerkships. So the two tracks had differing years 1–2 and the same year 3. Results noted that the PBL track had more women and older students, so these variables were set out as covariates analyzing other scores. Comparing the PBL versus STND tracks, USMLE scores were statistically equal over the years 1994–2002. PBL was 204.90 ± 21.05 and STND was 205.09 ± 23.07 ( P , 0.92); Step 2 scores were PBL 210.17 ± 21.83, STND 201.32 ± 23.25 ( P , 0.15). Clerkship overall scores were overall statistically significantly higher for PBL tract students in Obstetrics and Gynecology and Psychiatry ( P = 0.02, P < 0.001, respectively) and statistically not different for other clerkships. Clerkship subcategory analysis demonstrated statistically significantly higher scores for PBL tract students in clinical performance, knowledge and clinical reasoning, noncognitive behaviors, and percent honors grades, with no difference in the percentage of remediations. The school decided to switch to a single-tract curriculum after 2002. The problems noted with the PBL curriculum involved recruiting PBL faculty and faculty acceptance of student interactions, and also assessment issues. Faculty had to be trained to teach in PBL, which was time consuming and interfered with the process of learning by students. In addition, some faculty felt that the teachers should determine the learner's needs and not vice versa. The PBL assessment tools were novel and not immediately accepted by the faculty. 19 Other schools noted similar problems with PBL: it is different than LBL, and difficult to teach, as it is extremely learner centered. Learning objectives are essentially generated by the student, making faculty control over learning difficult. At this school, the difficulties in using PBL contributed to its abandonment as a stand-alone curriculum tract.

The difficulties in using PBL were associated with changes in other medical schools. Two medical schools in the United States, namely, University of California, Los Angeles, and University of California, Davis, changed from a PBL method to a CBL method for teaching a course entitled Doctoring , which was a small group faculty led course given over years 1–3 in both schools. 4 Both schools had a typical PBL approach, with little student advance preparation, little faculty direction during the session, and a topic that was initially unknown to the student. After the shift in curriculum to CBL, there were still small group sessions, but the students were expected to do some advance reading, and the faculty members were instructed to guide or direct the problem solving. Since in both schools the students and faculty had some experience with PBL before the shift, a survey was used to assess student and faculty experiences and perceptions of the two methods. Both students and faculty preferred CBL (89% of students and 84% of faculty favored CBL). Reasons for preference of CBL over PBL were as follows: fewer unfocused tangents (59% favoring CBL, odds ratio [OR] 4.10, P = 0.01), less busywork (80% favoring CBL, OR 3.97 and P = 0.01), and more opportunities for clinical skills application (52%, OR 25.6, P = 0.002). 4 In summary, these two reports indicate that while a case-oriented learning session can prepare students for both tests of knowledge and also clinical reasoning, PBL has the problems of difficult to initiate faculty or teachers in teaching this way, difficult to cover a large amount of clinical ground, and difficulty in assessment. CBL, on the other hand, has advantages of flexibility in using the case and offers the same reality base that offers relevance for the adult health-care learner. In addition, CBL appears to be accepted by the faculty that may be practicing clinicians and offers a way to teach specific learning objectives. These advantages of CBL led to it being the preferred method of case-related learning at these two large medical schools.

Advantages of CBL and deeper learning

Another touted advantage of CBL is deeper learning. That is, learning that goes beyond simple identification of correct answers and is more aligned with either evidence of critical thinking or changes in behavior and generalizability of learning to new cases. Several articles described this aspect of CBL. One article was set at a tertiary care hospital, the Mayo Clinic, and was a teaching model for quality improvement to prevent patient adverse events. 33 The students were clinicians, and the course was a continuing education or postgraduate course. The authors in the Quality Improvement, Information Technology, and Medical Education departments created an online CBL module with three cases representing the most common type of patient adverse events in internal medicine. The authors use Kirkpatrick's outcomes hierarchy to assess the level of critical thinking after the CBL intervention. Kirkpatrick's outcomes hierarchy is based on four levels: the first, reaction of learner to educational intervention, the second, actual learning: acquiring knowledge or skills, the third, behavior or generalizing lessons learned to actual practice, and the fourth, results that would be patient outcomes. 72 The authors note that as one moves up this hierarchy, learning is more difficult to measure. A survey can measure hierarchy level 1, a written test, and level 2. Behavior is more difficult but still able to be measured. The authors measured critical thinking in physicians, taking their Quality Improvement course by measuring critical reflection by a survey. The authors constructed a reflection survey, which asked course participants about items constructed to assess their level of reflection on the cases. Least reflective levels consisted of habitual action, and most critically, reflective items asked physicians if they would change the way they do things based on the cases. The results of their intervention showed that physicians had the lowest scores in reaching the higher levels of reflective thinking. However, the reflection scores were shown to be associated with physicians’ perceptions of case relevance ( P = 0.01) and event generalizability ( P = 0.001). This study was the first to evaluate physician's reflections after a CBL module on adverse events. The assumption is that deeper learning will be more likely to lead to behavioral changes.

Another attempt to measure deeper learning was reported from a dental school in Turkey. 8 The authors compared a CBL course with an older LBL course from the previous year by using “SOLO” taxonomy, developed by Biggs and Collis. 73 SOLO taxonomy rates the learning outcomes from prestructural through extended abstract. For example, in unistructural, the second item of SOLO, items could be “define”, “identify”, or “do a simple procedure”, whereas in the “extended abstract” level, the items are “evaluate”, “predict”, “generalize”, “create”, “reflect”, or “hypothesize” in higher mental order tasks. 8 A post-test was used to measure the responses on the test. The test questions were assigned to SOLO categories. In the first three categories of SOLO taxonomy questions, there was no statistical difference in scores between LBL and CBL groups. In the last two or higher categories of questions based on SOLO taxonomy, there was a statistically significant increase in the scores for relational and extended types of questions for the CBL group ( P = 0.014 and 0.026, respectively). This review shows a benefit in higher level learning using a CBL program. Again, the assumption is that by inducing higher order mental tasks, deeper learning will occur and behavioral change will follow.