Khoros AI and automation delivers unmatched efficiency for marketing and service excellence. Read more

AI & Automation

AI for every conversation, campaign, and customer

Khoros Communities

Self-service support, education, and collaboration

Khoros Service

Agent efficiency, automation, and operational insights

Khoros Social Media Management

Content management, publishing, and governance

Strategic Services

Our in-house experts in social media and community management for Khoros customers

Professional services

More than onboarding and implementation, this is where our partnership begins

Product coaching

Increase satisfaction and improve product adoption with complimentary training.

Upcoming events

Join us for webinars and in-person events

Insights, tips, news, and more from our team to yours

Customer stories

Case studies with successful customers to see how they did it

Resource Center

Guides, tipsheets, ebooks, on-demand webinars, & more

Integrations

Integrations to connect with your customers, wherever they are

Tech integrations

Developer information

Technical overviews and links to developer documentation

- Join our community

EXPERT INSIGHTS

Oct-21-2022

The role of social media during the COVID-19 pandemic

Jackson Kushner

During the height of COVID-19, people around the world used social media to stay connected — even while physically separated. This made COVID-19 different from previous pandemics. As countries began to quarantine, there were seismic shifts in communities and across business, which were documented and influenced by social media.

Here we look at social media’s role throughout the COVID-19 quarantine, and which trends we think continue to permeate today.

The importance of social media during the COVID-19 pandemic, and why it matters

Can you imagine first learning about a pandemic because a Boy Scout knocked on your door to tell you about it? Well, during the 1918 flu pandemic, that’s how it worked.

The CDC estimates the 1918 flu pandemic infected a third of the world’s population and killed an estimated fifty million people globally. A public health report on Minneapolis’ response to the 1918 flu shows that critical information regarding the virus was primarily shared via postal workers, Boy Scouts, and teachers; very different to how information is shared today.

Now, not only do we have access to news sources at our fingertips, but the speed at which we consume information means we have immediate access to livesaving social and medical information.

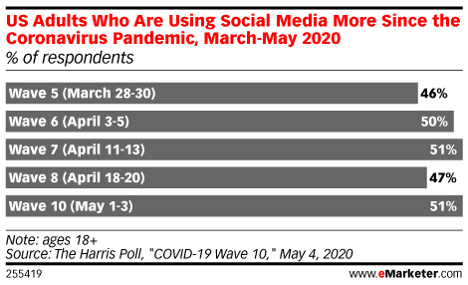

More people logged on to social media during the pandemic than ever before. A study by the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health found that 70% of respondents (Spanish adults) reported their social media use increased during the first wave of the pandemic in 2020, and 87% reported increases during the second wave in 2021.

Even before the pandemic, businesses and governments used social media to share information. The severity of COVID-19, the confusion around the safest protocols, and the mandated COVID-19 quarantines all underscored the need for an even more strategic approach to social media usage.

For example, during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, businesses used social media to better support employees and customers like never before, and governments leveraged it to quickly share the latest news and information across platforms.

The pandemic in many ways sped up the adoption of digital channels for people, businesses, and governments alike and permanently shifted how we move in the world. These are the four most important social media takeaways from the pandemic.

1. Social media can provide both information and misinformation

The speed with which information could be spread was one of the biggest benefits of social media during COVID-19 — and also one of its biggest drawbacks. On the positive side, governments, healthcare agencies, and even brands used social media to provide people with a better understanding of events in real-time. But it was also usedto spread falsehoods, including miracle preventative measures, false claims about martial law, conspiracy theories, masks, and more. The spread of helpful health information was prominent, but so was the spread of misinformation.

Finding trusted sources of information duringCOVID-19 could sometimes be challenging — especially on social media. With so much incertainty, people grappled for as much information as possible and thus became more susceptible to false and sometimes hazardous claims, which they shared with to others. According to a PEW Research Center report , about half of Americans said they’d seen falsenews about COVID-19.

Distinguishing between trustworthy vs. untrustworthy sources on social media is crucial

A comprehensive WHO study on how people sought out and responded to fake news found a majority of respondents (59%) across the globe were often highly aware of untrustworthy sources. If they encountered a source that they knew to be inaccurate, 35% said they ignored it and 25% said they reported it, and 8.6% said they unfollowed the poster. In terms of positioning your brand as being reliable and worthy of an individual’s attention, none of these responses to inaccurate information promotes good outcomes.

As a business, it’s your responsibility to ensure the information you decide to share is fact-checked and accurate. On social media, be cautious to avoid alarmist or absolute language in an effort to provide help instead of instill fear. It is more important now than ever before that businesses pay attention to what they share, and stick to facts.

2. Social media can influence public response to outbreaks

Here are a few of the most distinct ways social media influenced the public at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic — especially when lockdowns started in March 2020.

Social distancing and home quarantine provide opportunities for digital connection

Until COVID-19, many of us hadn’t even heard of “social distancing.” Soon after the world went into lockdown, social media users called for social distancing and encouraged people to stay strong during mandated quarantines.

One of the benefits of social media during the first wave of the pandemic was it enabled helpful information to be easily shared with a wide audience.

Meanwhile, many organizations even came up with creative ways to continue engaging with people via social media. For example the Getty Museum asked people to recreate works of art using items found in their homes and post them to their social accounts.

We challenge you to recreate a work of art with objects (and people) in your home. 🥇 Choose your favorite artwork 🥈 Find three things lying around your house⠀ 🥉 Recreate the artwork with those items And share with us. pic.twitter.com/9BNq35HY2V — Getty is Celebrating 25 Years (@GettyMuseum) March 25, 2020

“Quarantine culture” became a trend as society went from dealing with the lockdown to embracing it — changing the ways brands interacted with consumers .

Social media both promotes and discourages pandemic-related behaviors

At the start of the pandemic, many people panic-purchased things like household goods, sanitization products, and food in fear that necessities would become scarce— much like you would see with a natural disaster.

On social media, we saw panic buying discussed in two distinct ways: (1) people posting about their own panic buying, showing images of carts filled with toilet paper, water bottles, and frozen meals; and (2) people posting pictures of empty shelves or other people’s carts as a way to shame supposed panic buyers.

During this time, it was key for businesses to ease consumer fears that led to panic buying. With social media, businesses could quickly update customers and clients with information on supply chain and restocks. Businesses also have authority to speak on how customers can obtain products responsibly and sustainably — making the business-to-consumer connection stronger.

3. Social media provides a platform for socially responsible product marketing and branding

The COVID-19 outbreak was a defining moment for many brands in how they chose to market their products. Some took advantage of people’s fear during the pandemic by selling snake oil-type products (think essential oils claiming to provide immunity), while others took the opportunity to do right by their customers and the community.

Social media highlights product needs and opportunities brought on by new circumstances

As the pandemic ramped up, we saw businesses pay extra attention to emerging trends, such as the increased search volume for things like face masks and hand sanitizer.

In fact, many brands responded to the overall increase in demand by pivoting from their normal products to produce these suddenly in-demand goods. Alcohol companies like Anheuser-Busch shifted from brewing beer to making hand sanitizer, Tesla began producing ventilators, and Brooks Brothers went from stitching suits to face masks.

Other examples of pandemic-related marketing that filled a sudden need include stores and restaurants emphasizing curbside pick-up and delivery services and the countless “video-conference” advertisements aimed toward people working at home.

Brands focused on socially responsible product marketing

Despite the uptick in alarmist-focused media spend, many businesses provided powerful and empathetic responses to COVID-19. Brands recognized their main responsibility was to provide for the safety and well-being of their employees and customers.

In response to a tweet sent by a librarian in Dubai , Audible made a wide selection of titles free for kids and teens for the duration of the pandemic, helping them to fill hours spent at home, unmoored from the usual schedules.

Dial spread awareness about the proper handwashing technique and Reebok offered to create customized home workouts for consumers.

4. Social media can bring positivity during a scary time

No platform is perfect. While we saw misinformation and fear on social media, there was also an abundance of lifesaving information, connection, and global unity. Social media let us share experiences with family and friends to combat isolation while reminding us we’re all in this together.

Here are a few of the ways that social media made positive impacts during the COVID-19 pandemic:

Fundraisers were organized and distributed on social to help raise money for those in need

COVID-19 put many — especially the elderly, those with disabilities, working parents who lost childcare, and those who lost their jobs — in challenging situations. During the pandemic, communities rallied by sharing fundraisers with large audiences on social media.

On an individual level, the role social media played during the quarantine period helped people offer support in any way they could, such as picking up groceries for individuals who were unable to leave home. The importance of social media during lockdown for keeping people connected shouldn’t be underestimated.

Many local businesses used social media to spread the word about how local communities could support them during the pandemic, and corporations used it to fundraise and spread information about assistance initiatives.

Social media after the height of the COVID-19 pandemic

COVID-19 is the first pandemic with social media. We’re just beginning to understand social media’s role in how people experience and handle outbreaks of this scale. In the years to come, more studies will show us exactly how social media influences the ways the public and businesses alike respond to such an unprecedented global event, and how those responses on a public platform impact individuals, corporations, and governments.

If one thing is for sure, it’s that the pandemic has forever changed the ways in which brands interact with consumers — and social media is at the forefront of that shift. Social media usage during the pandemic shaped us, our businesses, and our government. In our twenty years of experience improving CX, Khoros has never seen so many businesses have to shift and adjust to so much so quickly.

Manage your social media during the pandemic and beyond with Khoros

Khoros is proud to have helped our clients throughout COVID-19. We also encourage you to check out our COVID-19 resource page and COVID-19 Marketing webinar , or any of the following resources we created for marketing and social media during COVID-19:

Guide to marketing during a pandemic

Re-engaging your customers after a pandemic

Contact center challenges during COVID-19

Driving customer engagement from home

COVID-19 customer engagement tip sheet

Need help managing your social media? Khoros is here for you through the good times and the bad. We help our clients reduce time spent managing social media and more with unified social listening , planning, and publishing. Our social media management tools help you scale, elevate, protect, and measure your social content, while our digital customer service tools for social media and review platforms allow you to manage service inquiries across channels.

Request a demo today and learn how Khoros can help you create customers for life!

RELATED RESOURCES

The strategic advantage of outsourcing customer service (and how to do it)

Explore 5 tips for outsourcing customer care. Elevate your service standards by mastering true partnership and transforming your customer experience approach.

Apr-01-2024

SOCIAL MEDIA

2024’s top social media trends: How social listening maximizes their potential

Our in-house experts curated a list of seven trends predicted to define social media engagement in 2024. Using their practical social listening tips, you can pave your way to a success-filled year.

Mar-27-2024

ONLINE COMMUNITIES

What is community marketing and how to start

Community marketing can help you build lasting customer relationships. Learn our top community marketing strategies and more.

Mar-21-2024

CUSTOMER ENGAGEMENT

4 tips from Esri on aligning stakeholders and driving community business value

Chris Catania, Esri's Head of Community, shares four invaluable tips to align stakeholders and drive business value for community initiatives, offering a roadmap to community success for hi-tech enterprises.

CUSTOMER SERVICE

6 best practices for B2B customer service

B2B customer service is important for creating and maintaining business relationships. Discover what it is, best practices, examples, and more.

Mar-20-2024

Why your brand should have a virtual community

Virtual communities offer brands the opportunity to deepen customer relationships and build loyalty. Learn the benefits and how to build one.

Mar-19-2024

Five steps to replacing Social Studio in 2024 - Don’t forget #2!

Social Studio is ending in 2024. Follow these steps to find your replacement solution.

Mar-14-2024

Khoros on Khoros: How we harnessed employees’ power to transform our results

Learn how EveryoneSocial empowered Khoros' team members to become passionate brand ambassadors, augmenting outreach beyond the limits of traditional approaches.

Community works: How Esri drives customer success and business value

Watch this ondemand webinar to hear Chris Catania, Head of Community at leading geographic information system (GIS) software provider Esri, discuss strategies he used for aligning internally, securing stakeholder buy-in, and optimizing the Esri community to deliver measurable business value to the company, customers, partners, and employees.

Mar-13-2024

Getting alignment: A quick guide to rallying stakeholders around your community

To thrive, your community needs buy-in from all relevant stakeholders. Use this guide to align internal teams with your community project.

Mar-11-2024

90-day checklist: How to set up employee advocacy for your brand

Get every step you need to set up a successful employee advocacy program for your brand in no time.

A month in review: February social media trends and updates

We're diving into the hottest social media trends and noteworthy industry updates that have been making waves in the digital sphere over the month of February.

Mar-08-2024

Sign up for our newsletter

Would you like to learn more about khoros.

Discover the advantages of our solution in action. Request a demo now!

- How to recruit?

- Internship calendars

- Post an offer

- How to give

- Ways to give

- 2019-2024 campaign

- News and publications

- Annual Report

- Build your brand

- Work with our students

- Become a partner

- Our corporate partners

What is the Role of Social Media During the COVID-19 Crisis?

Today, social media such as Twitter, Facebook and Instagram, have become primary sources of information. They are also vehicles for fake news and disinformation. During a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic, how should social media be mastered and employed in a responsible way? HEC Paris Associate Professor of Marketing, Kristine de Valck, has been studying the role of social networks in the marketplace since 1999. She explains.

©chaay tee on Adobe Stock

Listen to the podcast:

How do companies and individuals use social media during such crisis.

Broadly, there are two opposing logics. Companies can use social media for commercial purposes or for communal purposes. In other words, companies use social media to brand, sell, market their business (which is close to traditional marketing efforts using mass-media) versus using social media to connect with and co-create with customers and – more importantly – to provide a platform to customers to bond together. You can see this as the distinction between using social media to talk to your customers versus using social media to talk with your customers and have them talk to each other through your brand.

You can see this as the distinction between using social media to talk to your customers versus using social media to talk with your customers and have them talk to each other through your brand.

For individuals, the same axe translates into using social media to self-present – that can turn into the very narcissistic self-exposure that we sometimes see on social media versus using social media to connect with friends, family and likeminded others for socialization and emotional support.

What particular strengths of social media are highlighted during such difficult times?

For me, this crisis highlights the particular strengths of social media in how they can be used for the second type of purpose; that is community and emotional support.

Just like we have seen with other crises, such as the earthquake and following tsunami that caused the nuclear disaster in Japan in 2011, the terrorists attacks in Paris and elsewhere in Europe over the past years, we see today that people all over the world reach out to each other – close by and far away – through social media to make sense of what is happening.

Just like we have seen with other crises, people all over the world reach out to each other through social media to make sense of what is happening.

I am thinking of the many funny videos about how people creatively deal with the lockdown, of the neighborhood Facebook groups that organize entertainment and practical support to help neighbors who need assistance with grocery shopping or childcare, and the quick rise of apps and functionalities that allow for live chat and video sessions with multiple people. This is social media in its core and at its best.

People turn to social media not only for support and entertainment, but also use it as a source of information… and fake news.

This is where we need to warn for the dark side of social media and its role in spreading fake news. Platforms have been slow in acknowledging their responsibility in helping platform users distinguish fake news from facts, but they are taking steps in the right direction. Instagram, for example, announced to only include COVID-19 related posts and stories in their recommendation section that are published by official health organizations. In general, my advice is to crosscheck information that you get through social media with at least two other information sources such as government websites and high-quality news outlets. In addition, we also all have a role to play by not further spreading rumors through our social media accounts.

How should marketers adopt their social media strategies in this extraordinary time?

It is a tricky question. Typically, I teach my students that marketers should relate their social media contributions to the real-time context. Indeed, at the start of the crisis I kept receiving long-before planned brand posts that did not refer at all to the situation, and thus, seemed misplaced. At the same time, trying to leverage a sanitary crisis for branding purposes in your social media posts can quickly be perceived as distasteful.

The best examples I have seen come from companies that offer free resources to their customers to face the crisis. For example, many academic publishers have made online content available for free to support teachers and students worldwide with distance learning. Closer to home, the Pilates teacher at HEC Paris has started a YouTube channel where he posts videos on how we can keep fit while confined at home.

Instead of self-glorifying social media brand posts, brands will be forced to embrace the communal logic of social media during the COVID-19 crisis.

Instead of self-glorifying social media brand posts, brands will be forced to embrace the communal logic of social media during the COVID-19 crisis. More than ever, social media posts should be user-centric and not producer-centric. Brands that will be able to deliver messages and engage in conversations that are considered valuable because they provide helpful information, relevant advice or that simply make you laugh will come out of the crisis stronger.

Stay safe and keep sharing!

Kristine de Valck's research and teaching focus on how the Internet in general and social media in particular have changed consumer behavior...

Related content on Marketing

Going Circular to Align Business Models with Planetary Boundaries

By Daniel Halbheer

What Machine Learning Can Teach Us About Habit Formation

By Anastasia Buyalskaya

Copyright: nakhin

What is Experience Worth in A Sales Career? And What it Means for Talent Retention

By Dominique Rouziès, Bertrand Quélin, Michael Segalla

©tupungato/123RF.COM

Are Strong Brands Stressing Out Their Mid-level Employees?

By Dominique Rouziès

How to Handle People’s Data Ethically

By Michael Segalla, Dominique Rouziès

Newsletter knowledge

A monthly brief in your email box and 3 issues of the book per year.

Insights @HECParis School of #Management

Support Research

Our articles are produced thanks to our reader's support

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Social Media Use and Mental Health during the COVID‐19 Pandemic: Moderator Role of Disaster Stressor and Mediator Role of Negative Affect

1 Peking University, Beijing China

Guangyu Zhou

Informed by the differential susceptibility to media effects model (DSMM), the current study aims to investigate associations of COVID‐19‐related social media use with mental health outcomes and to uncover potential mechanisms underlying the links.

A sample of 512 (62.5% women; M age = 22.12 years, SD = 2.47) Chinese college students participated in this study from 24 March to 1 April 2020 via online questionnaire. They completed measures of social media use, the COVID‐19 stressor, negative affect, secondary traumatic stress (STS), depression, and anxiety as well as covariates.

As expected, results from regression analyses indicated that a higher level of social media use was associated with worse mental health. More exposure to disaster news via social media was associated with greater depression for participants with high (but not low) levels of the disaster stressor. Moreover, path analysis showed negative affect mediated the relationship of social media use and mental health.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that the disaster stressor may be a risk factor that amplifies the deleterious impact of social media use on depression. In addition, excessive exposure to disaster on social media may trigger negative affect, which may in turn contribute to mental health problems. Future interventions to improve mental health should consider elements of both disaster stressor and negative affect.

INTRODUCTION

A newly emerging coronavirus, SARS‐CoV‐2 (previously known as 2019‐nCoV) which can cause coronavirus disease (COVID‐19), a severe respiratory illness like SARS and MERS, was first reported in Wuhan, China at the end of 2019. The World Health Organization (WHO) initially declared the COVID‐19 outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) and then characterised it as a pandemic. In response to the pandemic, rigorous policies to restrict public movement and large gatherings have been implemented in China, such as extending the Lunar New Year holiday, postponing the spring semester for universities, primary and middle schools and kindergartens (“China Extends Spring Festival Holiday”, 2020 ). Due to the strict physical distancing measures, people are heavily reliant on media, especially social media (e.g. Weibo and WeChat), to learn the latest news about the pandemic and to maintain connectivity (Limaye et al., 2020 ).

Disaster Media Exposure and Mental Health

Despite the importance of media in spreading urgent information during times of collective trauma events, numerous studies have suggested that disaster media exposure may evoke poor mental health outcomes. For example, early 9/11‐ and Iraq War‐related television exposure was prospectively associated with increases in posttraumatic stress (PTS) symptoms (Silver et al., 2013 ). Following the Boston Marathon bombings, six or more daily hours of bombing‐related media exposure was associated with higher acute stress symptoms in individuals outside the directly affected community (Holman, Garfin, & Silver, 2014 ). Among adolescents who did not experience the Sichuan earthquake in 2008, those who were frequently exposed to distressing media images reported a higher risk of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) 6 months later (Yeung et al., 2018 ). Although the negative impacts of disaster media exposure on a range of psychological outcomes have been demonstrated (see the review by Pfefferbaum et al., 2014 ), secondary traumatic stress (STS) was not adequately addressed (Ben‐Zur, Gil, & Shamshins, 2012 ; Blanchard et al., 2004 ). STS refers to PTSD‐like symptoms, such as arousal, avoidant behaviors, and intrusive imagery, as a consequence of being indirectly exposed to traumatic events (Branson, 2019 ; Ludick & Figley, 2017 ). Given that most people are not infected with SARS‐CoV‐2, it is critical to consider whether media exposure is associated with STS among the general population. Indeed, Li et al. ( 2020 ) found that the general public reported even higher levels of vicarious traumatisation than front‐line nurses fighting COVID‐19.

Compared with traditional media, social media has played a multitude of positive roles in information exchange during the COVID‐19 crisis, including disseminating health‐related recommendations, enabling connectivity and psychological first aid (Merchant & Lurie, 2020 ), showing public attitudes, experience, and perception of the disease as well as sentiment to the government (Zhu, Fu, Grépin, Liang, & Fung, 2020 ). On the other hand, social media has also fueled the rapid spread of misinformation and rumors, which can create a sense of panic and confusion among the public (Garfin, Silver, & Holman, 2020 ). However, there has been a dearth of studies focused specifically on social media exposure. Thus, it is still unknown whether and how using social media to access COVID‐19 is associated with mental health. In addition, it is necessary to examine the association in young adults, considering that they are more frequent users of social media (China Internet Network Information Center, 2013 ) and are prone to use social media sources to access disaster‐related messages (Piotrowski, 2015 ).

Theoretical Backdrop

The Differential Susceptibility to Media Effects Model (DSMM; Valkenburg & Peter, 2013 ) is a well‐established integrative model that addresses relationships between media use and health outcomes. According to the DSMM, media usage can influence users’ cognitive, emotional, physiological, and behavioral outcomes. Certain individual or social variables moderate the direction or strength of media exposure effects. A group of variables such as current and prior traumatic stress, as well as prior health status, may serve as potential moderators (Houston, Spialek, & First, 2018 ). Indeed, the relationship between media exposure and worry about the Ebola pandemic was augmented in individuals who reported a higher level of stressful responses to a prior bomb attack (Thompson, Garfin, Holman, & Silver, 2017 ). In another study, respondents who had previous mental health diagnoses were sensitised to media coverage of disaster events and reported more distress (Thompson, Jones, Holman, & Silver, 2019 ). To date, however, the conditional effects, such as the moderating role of COVID‐19 stress between social media use and mental health, have not been examined in the current pandemic.

Three response states (i.e. cognitive, emotional, and excitative states) have been proposed as mediator mechanisms between media use and health outcomes in the DSMM. Only two studies explicitly examined the mediating process, with acute stress and fear as mediators, respectively (Holman, Garfin, Lubens, & Silver, 2019 ; Silver et al., 2013 ). Using longitudinal designs, Silver et al. ( 2013 ) concluded that acute stress did not mediate the association between media exposure and physical health, whereas Holman et al. ( 2019 ) found that fear of future terrorism significantly mediated the association between media usage and functional impairment. Although underexplored, there has been some evidence suggesting that negative affect might mediate the disaster media effects. For example, watching television news after the 9/11 terrorist attack was related to a range of negative emotions, such as fear, anger, and frustration (Cho et al., 2003 ). Negative affect, in turn, was often a predisposition to mood disorders (e.g. depression; Mor et al., 2010 ) and anxiety‐related disorders (e.g. PTSD; Weems et al., 2007 ) in the context of disaster.

The Present Study

The present study aims to investigate whether and how social media exposure to COVID‐19 was associated with various mental health outcomes in a sample of Chinese college students. The relationships among social media use, the COVID‐19 stressor, negative affect, and mental health, such as STS, depression, and anxiety, were examined. Drawing on the logic of the DSMM and empirical findings on traditional media use, we formulated the following hypotheses:

The more time participants spend on social media accessing content related to COVID‐19, the more STS, depression, and anxiety they experience, after controlling for both traditional and internet media usage.

More COVID‐19 stressors are associated with greater STS, depression, and anxiety, after controlling for key covariates (e.g. prior collective trauma exposure, health history).

The COVID‐19 stressor moderates the relationship between social media use and mental health. Participants with a higher level of COVID‐19 stressor report more mental health problems with cumulative daily use of social media, while the association of social media exposure and mental health is attenuated among those with a lower level of COVID‐19 stressor.

Negative affect mediates the relationship between social media use and mental health. Specifically, social media use positively correlates with negative affect, which in turn, is positively associated with STS, depression, and anxiety.

Procedure and Participants

The present study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Peking University. To reach college students, the first author posted a recruitment message containing an introduction to the study on a popular social media network in China. During the data collection period, from 24 March to 1 April 2020, the recruitment advertisement was shared and reposted hundreds of times. Viewers who were interested in the study could scan a quick response code directing them to a consent form. Once giving his or herconsents, the potential participant was invited to fill in an online survey via www.sojump.com . It takes about 10 minutes to complete the survey.

There were 705 university students who completed the questionnaire. Following the suggestions of Curran ( 2016 ), the study adopted various data screening methods to ensure the quality of online data, including response time restriction (ranged from 300s to 2000s, excluded 62 participants), one bogus item (i.e. “I’ve never used a mobile phone in my life”, excluded 67 participants), two instructed items (e.g. “Please indicate option [agree] for this question”, excluded 60 participants), and self‐report diligence at the end of the survey (i.e. “In your honest opinion, should we use your data in our analyses?”, excluded four participants). The final sample comprised 512 Chinese college students (62.5% women; M age = 22.12 years, range = 18–30 years; for details see Table 1 ).

Characteristics and Responses of Participants ( N = 512)

COVID‐19 related media use, risk factors (i.e. the COVID‐19 stressor, prior collective trauma exposure, and health history), and psychological outcomes (i.e. negative affect, STS, depression and anxiety) were assessed as well as demographics.

Social Media Use

Social media use was adapted from the assessment tool developed by Lin et al. ( 2016 ). Participants were required to recall the average number of total hours per day they had spent on social media usage during the period of severe epidemic (20 January–17 February 2020, characterised by a sharp increase in accumulated confirmed cases from 258 to 70,635). Specifically, they were asked to estimate the time spent accessing COVID‐19‐related information through seven widely used social media platforms (i.e. Weibo, Wechat, QQ, Zhihu, Douban, Douyin, and Kuaishou) in China. Responses could range from 0 to 12 hours for each platform. Social media use was computed by summing up the total daily hours, with higher hours indicating more social media use.

COVID‐19 Stressor

Adapted from the measurement of SARS‐related stressors (Main et al., 2011 ), a checklist tool with 10 items was used to assess COVID‐19 stressors. Participants were asked whether they experienced the lockdown of Wuhan, confirmed or suspected infection, experienced the death of loved ones, witnessed people dying from the infection, worked with infectious patients, volunteered in epidemic prevention and control, and lacked necessities, such as food, face masks, disinfectants, and medical care. Responses were “yes” (coded as 1) or “no” (coded as 0) to each item. The scores of all items were summed to reflect indexes of disaster stressor during the pandemic. The scores ranged from 0 to 10, with a higher score indicating a higher level of disaster stressor.

Negative Affect

The 10‐item self‐reported Negative Affect (NA) scale of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988 ) was used to measure participants’ negative mood in the past two weeks (e.g. “Hostile”, “Afraid”) with 5‐point Likert‐type graded responses (1 = not at all, 5 = very strongly). Total scores were calculated for analyses, with higher scores indicating more negative affect experienced (Cronbach’s α = .91).

Secondary Traumatic Stress (STS)

STS was measured using the 17‐item Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale for Social Media Users (STSS‐SM), which was originally developed by Bride, Robinson, Yegidis, and Figley ( 2004 ) and further adapted by Megan ( 2019 ) in a sample of social media users. The scale assessed participants’ traumatic symptoms such as avoidance, intrusion, and arousal through their experiences on social media with traumatised individuals or traumatic events, using 5‐point Likert‐type scales (1 = never and 5 = very often). For example, “Reminders of things I’ve seen on social media upset me”. Total scores were calculated to indicate STS level (Cronbach’s α = .93).

The nine‐item Patient Health Questionnaire depression module (PHQ‐9; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001 ) was used to measure depressive symptoms in 4‐point Likert‐type graded responses (1 = not at all and 4 = nearly every day). For example, “Little interest or pleasure in doing things”. Total scores were calculated to indicate the level of depression (Cronbach’s α = .89).

The seven‐item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD‐7; Spitzer, Kroenke, Williams, & Löwe, 2006 ) was used to assess anxiety symptoms in 4‐point Likert‐type graded responses (1 = not at all, 4 = nearly every day). For example, “Not being able to stop or control worrying”. Total scores were calculated to indicate the level of anxiety (Cronbach’s α = .91).

Traditional and online media use measured the time spent accessing COVID‐19‐related information through three types of traditional media (i.e. television, radio, newspapers) and online media such as Jinri Toutiao (today's headlines). Prior collective trauma exposure evaluated (a) whether participants or their close others were seriously injured, (b) whether participants witnessed others dying in the 2003 SARS epidemic or the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake. Participants who gave at least one “yes” response were coded as 1, otherwise coded as 0. Health history was assessed with two items inquiring whether participants had a cold during the COVID‐19 pandemic or had a history of mental disorder. Participants who answered at least one “yes” response were coded as 1, otherwise coded as 0. Demographics including age, gender, ethnicity, education attainment, and average monthly household income were assessed.

Statistical Analysis

First, social media use, traditional media use, and online media use were transformed with the square‐root for normality. Descriptive statistics and partial correlations of study variables were calculated while controlling for demographics. Given significant correlations of prior collective trauma exposure, health history, traditional and online media use with mental health, those variables were regarded as covariates in the following analyses. Harman’s one‐factor test (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986 ) was used to detect the possibility of common method bias (CMB). All variables of interest were entered into an exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and the cumulative variance explained by the first unrotated factor was less than 50 percent (i.e. 31.9%), indicating no serious CMB.

Second, to examine the moderating role of the disaster stressor in the relationship of social media use and mental health, mental health outcomes (i.e. STS, depression, and anxiety) were regressed on social media use, the COVID‐19 stressor, and their interaction. Finally, to test the mediating role of negative affect, a path analysis was conducted with social media use, the COVID‐19 stressor and the interaction term as predictors, negative affect as the mediator, and mental health as outcomes.

Data analyses were performed in SPSS 25 and Mplus 7.4. Multiple model fit criteria were used with RMSEA values lower than 0.08, CFI and TLI values close to 0.90 or higher indicating acceptability (Muthén & Muthén, 2012 ). Standardised, unstandardised, and 95% confidence intervals of path coefficients were estimated with 5,000 bootstraps.

Preliminary Analyses

Table 2 displays descriptive statistics and correlations among the study variables. The skewness and kurtosis of all variables were between −2 and +2, which demonstrated acceptable univariate normality (Mallery & George, 2003 ). Among the hypothetical risk factors, the COVID‐19 stressor was positively related to negative affect ( r = 0.12), STS ( r = 0.25), depression ( r = 0.19), and anxiety ( r = 0.20). Health history correlated positively with negative affect ( r = 0.16), STS ( r = 0.21), and anxiety ( r = 0.10), while prior trauma had no significant correlation with mental health. Among COVID‐19‐related media use, social media use was positively related to negative affect ( r = 0.12), STS ( r = 0.14), depression ( r = 0.10), and anxiety ( r = 0.10). Online media use positively correlated with STS ( r = 0.10), while traditional media use had no significant correlations with psychological outcomes.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations between Study Variables ( N = 512)

STS = secondary traumatic stress. All analyses controlled for age, gender, ethnicity, education attainment, and monthly average household income. Social media use, traditional media use, and online media use are square‐root transformed for normality, and the skewness and kurtosis after transformation are reported. The skewness and kurtosis of prior trauma and health history were not reported since normality testing is not necessary for binary variables.

Regression Analyses

Multiple linear regression results showed that associations of social media use with STS (β = 0.18, p < .001), depression (β = 0.11, p = .019), and anxiety (β = 0.12, p = .014) were significant, suggesting that participants who spent more time on social media reported more mental health problems. The results confirmed Hypothesis 1. Supporting Hypothesis 2, the associations of the COVID‐19 stressor and STS (β = 0.20, p < .001), depression (β = 0.18, p < .001), and anxiety (β = 0.18, p < .001) were also significant, such that more exposure to COVID‐19 was associated with more mental health problems.

More importantly, the interaction of social media use and the COVID‐19 stressor was significantly associated with depression (β = 0.09, p = .043). However, the associations between the interaction and STS (β = 0.06, p = .139) and anxiety (β = 0.06, p = .166) were not significant. Simple slope analysis was conducted to probe the significant interaction (Aiken & West, 1991 ). As Figure 1 illustrates, at a high level of the COVID‐19 stressor (1 SD above the mean), participants with a greater amount of social media use reported a significantly higher level of depression ( b = 1.05, SE = 0.35, 95% CI [0.36, 1.74]; p = .003). By contrast, at a low level of COVID‐19 stressor (1 SD below the mean), social media use was unrelated to depression ( b = 0.15, SE = 0.33, 95% CI [−0.48, 0.79]; p = .635). These results partially confirmed Hypothesis 3.

Interaction effects of social media use and the COVID‐19 stressor on depression. Note : Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals.

Path Analyses

To further test the mediating role of negative affect between social media use and mental health (i.e. Hypothesis 4), a path analysis was conducted (see Figure 2 ), which provided an acceptable fit to the data (CFI = 0.991; TFI = 0.922; RMSEA = 0.077, 90% CI [0.041, 0.118]; χ 2 (4) = 16.242). Table 3 displays direct, indirect, and total effects. In general, the model confirmed Hypothesis 4 indicating that social media use was indirectly associated with higher levels of STS ( b = 0.98, 95% CI [0.32, 1.64]), depression ( b = 0.42, 95% CI [0.13, 0.70]), and anxiety ( b = 0.41, 95% CI [0.13, 0.68]) through negative affect. Moreover, the model confirmed the results that the joint influence of social media use and the COVID‐19 stressor on depression was significant.

Path analysis examining the mediating role of negative affect and the interaction between social media use and the COVID‐19 stressor on psychological outcomes simultaneously ( N = 512). Note : Covariates are prior trauma, health history, traditional and online media use. Nonsignificant paths from covariates to dependent variables are omitted for visual clarity. The values showed are standardised path coefficients. Black solid lines refer to significant paths (bold lines/*** p < .001; semi‐bold lines/** p < .01; thin lines/* p < .05) and gray dashed lines refer to nonsignificant paths ( p > .05). Percentages indicate the explained variance of mediator and each dependent variable in the model.

Direct, Indirect, and Total Effects from Social Media Use and COVID‐19 Stressor to Psychological Outcomes

STS = secondary traumatic stress.

The mental health status of the public following the outbreak of COVID‐19 is a major issue of concern (Bao, Sun, Meng, Shi, & Lu, 2020 ). Excessive social media exposure to this public health crisis might lead to heightened acute stress and long‐term psychological distress (Garfin et al., 2020 ). Our main goal in the present study was to examine the relationships between social media exposure and psychological outcomes during the pandemic. Moreover, we aimed to examine the hypothesised moderator (i.e. the COVID‐19 stressor) and mediator (i.e. negative affect) based on the DSMM theory.

Unique Role of Social Media Use in Mental Health

Results showed that disaster‐related social media consumption was significantly associated with negative mental health (i.e. STS, depression, and anxiety). The relationship of media exposure and mental health has been evidenced during collective trauma events, such as Ebola (Thompson et al., 2017 ), the Sichuan earthquake (Yeung et al., 2018 ), and several terrorist attacks (Holman et al., 2014 ; Silver et al., 2013 ; Thompson et al., 2019 ). More importantly, this study has complemented the existing literature by differentiating media types (i.e. traditional, online vs. social media). Interestingly, our findings suggest that social media use particularly contributed to STS, depression, and anxiety while other media usages were unrelated to mental health. This pattern is in line with previous findings indicating that frequently social media usage was positively associated with the high odds of anxiety, depression (Gao et al., 2020 ), and PTS (Goodwin, Palgi, Hamama‐Raz, & Ben‐Ezra, 2013 ).

The unique role of social media use in mental health might be explained from the characteristics of social media. During the pandemic, social media has become one of the most important channels to disseminate information with an absolute superiority in speed, reach, and penetration (Merchant & Lurie, 2020 ). Compared with their use of traditional media, young adults are more likely to use social media sources to attend to disaster‐related coverage (Jones, Garfin, Holman, & Silver, 2016 ). Massive information on social media with various forms (e.g. text, picture, video and live streaming) enables people to stay informed on the latest policies and recommendations regarding COVID‐19 prevention, and also to get connected with those who have been directly exposed to the disaster (e.g. infected patients, front‐line medical staff; Garfin et al., 2020 ). Meanwhile, social media has been used to create and share information with personal interpretations, which may lead to the transmission of rumors, conspiracies, or misinformation (Wang, McKee, Torbica, & Stuckler, 2019 ). Taken together, the indispensability and complexity of social media might amplify the negative psychological consequences of disaster exposure while at the same time covering the effects of traditional media.

Moderator Role of the COVID‐19 Stressor

In addition to media exposure, disaster‐related stressors have also been considered one of the key predictors of mental health (Paul et al., 2014 ). The COVID‐19 stressor was operationalised as a common stressor that people experienced amid the pandemic in the current study. A higher level of disaster stressor was associated with worse mental health outcomes. The result is consistent with prior studies indicating that individuals who experienced more disaster‐related stressors were at higher risk of DSM‐IV anxiety‐mood disorders (Galea et al., 2007 ). In addition, social media use was positively related to depression only at a high (but not low) level of the COVID‐19 stressor. It suggests that people who experienced a higher level of the stressor had greater vulnerability to depression. It should be noted, however, that the contribution of the interaction term is relatively small.

Individuals who suffered from collective trauma experienced higher levels of physiological arousal and fear, many of whom continued to worry about themselves and their families (Pfefferbaum et al., 1999 ). It is likely that excessive exposure to social media coverage maintained their heightened reactivity to traumatic events which may in turn, predispose them to develop post‐disaster stress. However, it is somewhat surprising that the interaction of social media use and the COVID‐19 stressor was only significantly associated with depression, but not STS or anxiety. A possible explanation might be that people who experienced the COVID‐19 stressor are faced with real problems such as lacking necessities and experiencing bereavement. Being immersed in social media may not solve the problems but reinforce their feelings of sadness and helplessness. In this sense, depression might be a more common manifestation of distress than other psychological symptoms.

Mediating Role of Negative Affect

Another main finding is that negative affect mediated the relationship between social media use and mental health (i.e. STS, depression, and anxiety). This finding is not only consistent with the theoretical mechanistic pathways proposed by the DSMM (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013 ), but is also in line with prior research indicating fear as a mediator from exposure to bloody images of a bombing event to future functioning impairment (Holman et al., 2019 ). It suggests that negative emotional states explain the relationship between exposure to COVID‐19 information on social media and negative mental health outcomes.

Exposure to disaster content on social media may be associated with mental health through differential plausible avenues. As stated by Bayer and his colleagues (Bayer, Triệu, & Ellison, 2020 ), one of the elements of social media is stream (or feeds), which is the aggregated flows of content seen on home pages of social media platforms (e.g. “Hot search” on Weibo; “Moments” on WeChat). The stream can help users gain knowledge of heated issues as well as others’ activities, thoughts, and stories. In the pandemic context, people have a strong desire to comprehend the consequences of the disaster and stream appears to fulfill this desire by leading users to authentic and personal information (e.g. short videos, blogs documenting COVID‐19) shared by those directly exposed to COVID‐19. This could open doors for emotion contagion because viewers may observe and perceive negative emotions expressed through social media (Kramer, Guillory, & Hancock, 2014 ). For example, respondents with social media exposure described negative emotions such as sadness, grief, compassion, shock, and numbness in a disaster situation (Neubaum, Rösner, Rosenthal‐von der Pütten, & Krämer, 2014 ). Such empathic responses combined with prolonged exposure to suffering may contribute to the onset of STS (Ludick & Figley, 2017 ). It is also possible that repeated exposure to heartbreaking news with respect to COVID‐19 puts people at risk of depression due to a process of grief rumination (Lenferink, Eisma, de Keijser, & Boelen, 2017 ). Unlike traditional media on which information is strictly regulated to ensure credibility, social media provides a public space where users can communicate unfiltered information, thus giving rise to rumors (Jones, Thompson, Dunkel Schetter, & Silver, 2017 ). Coronavirus rumors on social media can greatly exacerbate negative emotions (e.g. panic, fear, and distress), which may in turn induce anxiety symptoms (Dong & Zheng, 2020 ).

Possible Alternative Explanations for the Findings

Since the findings are largely based on cross‐sectional data, the directionality of the associations among social media use, negative affect, and mental health is still not clear. It is possible that individuals living with mental health conditions tend to consume more COVID‐19‐related information on social media. For example, individuals with major depressive disorder (MDD) did spend more daily hours using the computer compared to healthy controls (de Wit, van Straten, Lamers, Cuijpers, & Penninx, 2011 ), which may put them at increased risk of news coverage of collective trauma. Another study found that stress responses to past traumatic events predicted increased consumption of media following later collective tragedies (Thompson et al., 2019 ). Such specific media usage patterns may lead to subsequent post‐disaster distress over time, thereby fueling a vicious cycle. This process also corresponds with what the DSMM proposed as transactional effects that media exposure and health outcomes operate in a feedback loop.

Another possible explanation arises from uncertainty management theory which states that seeking disaster‐related information from media is a way of mitigating uncertainty (Lachlan, Spence, & Seeger, 2009 ). In the case of the September 11 attack, for example, those who experienced a range of negative emotions such as anger, grief, and powerlessness were motivated to learn about the disaster (Boyle et al., 2004 ). In the context of COVID‐19, people tend to perceive the coronavirus as threatening and present feelings of fear and worry. Consequently, these negative emotions may lead to increased use of social media to seek assurance, but may further heighten the risk for mental health disorders.

Implications

Regardless of the direction of association between social media use and mental health, our findings have important implications. From a theoretical perspective, our findings have enriched the DSMM model by identifying negative affect as one mediator as well as the COVID‐19 stressor as one moderator. The emotional pathway from social media use to mental health highlights the importance of managing negative emotions such as fear, anger, and sadness when using social media to access information. It is also worth noticing that people experiencing a higher level of the COVID‐19 stressor exhibited vulnerability to depression. Together with other dispositional factors such as prior collective trauma and pre‐existing mental health conditions, disaster‐related stressors serve as a significant moderator of the disaster media effect. Our findings also shed light on strategies of trauma prevention and intervention. It is critical for policymakers, public health agencies, parents, psychologists, and healthcare staff to remain sensitive to the potential negative consequences of ubiquitous social media exposure. The general public, especially those who have been directly or indirectly traumatised by COVID‐19, could be advised to avoid excessive social media use and learn effective emotion regulation strategies (e.g. reappraisal) to reduce negative emotions induced by news coverage.

Limitations

There are several limitations to the current study. Participants were fully recruited via social media and those who did not use any type of social media may not be included in the study, posing a potential threat to representativeness of the sample. Time on social media to access COVID‐19 information in a specified period was recalled, which was prone to recall bias. To increase memory accuracy, a brief timeline with major events was provided to remind participants of the time period. We used self‐report measures of social media use, which could be improved by ongoing media diaries or objective data accessed from media platforms. Face‐to‐face clinical interviews rather than self‐report measures of psychological symptoms could also be an alternative.

The time lag between the measurement of social media use and negative affect is not short enough to assess the immediate responses to disaster messages, given that emotional response was characterised as a state‐like variable in the DSMM (Valkenburg & Peter, 2013 ). It may be valuable for future studies to use intensive longitudinal measures (e.g. daily diaries or experience sampling) to capture the concurrent variations of emotions and social media use patterns on a daily level (Choi & Toma, 2014 ; Stieger & Lewetz, 2018 ). Furthermore, the current study measured negative affect as a general emotional state, making the concept excessively overlap with mental health outcomes (i.e. depression, anxiety, and STS). Future studies are encouraged to measure specific emotional responses to COVID‐19, such as fear (Ahorsu et al., 2020 ), grief (Kristensen, Dyregrov, Dyregrov, & Heir, 2016 ), and anger (Park, Aldwin, Fenster, & Snyder, 2008 ).

The current study only tested the potential mediating role of emotional states. Other mediators of disaster media effects, such as cognitive appraisal or excitative responses (Houston et al., 2018 ), likely exist and should be explored in future research. The study only measured frequency of social media consumption, and did not attempt to disaggregate for media content (e.g. positive vs. negative information; texts, graphics, or videos) and user types (e.g. active vs. passive use). To further investigate how media exposure influences mental health, more detailed assessments on social media use are needed (Hall et al., 2019 ; Neubaum et al., 2014 ). Although we have controlled for several potential confounds (i.e. prior collective trauma exposure, mental health, and demographics), it is still possible that other unmeasured, individual characteristics (e.g. neuroticism, specific mental health diagnoses) might exist and explain the observed associations. Lastly, it should be acknowledged that the cross‐sectional design limits causal inferences, although a theoretical case for the direction of causality can be made based on previous literature. Longitudinal studies with large time lags are imperative to clarify the psychological processes that may be affected by social media exposure as well as to track mental health symptoms over time following COVID‐19.

- Ahorsu, D.K. , Lin, C.‐Y. , Imani, V. , Saffari, M. , Griffiths, M.D. , & Pakpour, A.H. (2020). The Fear of COVID‐19 Scale: Development and initial validation . International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469‐ 020‐00270‐8. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aiken, L.S. , & West, S.G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bao, Y. , Sun, Y. , Meng, S. , Shi, J. , & Lu, L. (2020). 2019‐nCoV epidemic: Address mental health care to empower society . The Lancet , 395 ( 10224 ), e37–e38. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bayer, J.B. , Triệu, P. , & Ellison, N.B. (2020). Social media elements, ecologies, and effects . Annual Review of Psychology , 71 ( 1 ), 471–497. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ben‐Zur, H. , Gil, S. , & Shamshins, Y. (2012). The relationship between exposure to terror through the media, coping strategies and resources, and distress and secondary traumatization . International Journal of Stress Management , 19 ( 2 ), 132–150. [ Google Scholar ]

- Blanchard, E.B. , Kuhn, E. , Rowell, D.L. , Hickling, E.J. , Wittrock, D. , Rogers, R.L. , … Steckler, D.C. (2004). Studies of the vicarious traumatization of college students by the September 11th attacks: Effects of proximity, exposure and connectedness . Behaviour Research and Therapy , 42 ( 2 ), 191–205. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Boyle, M.P. , Schmierbach, M. , Armstrong, C.L. , McLeod, D.M. , Shah, D.V. , & Pan, Z. (2004). Information seeking and emotional reactions to the September 11 terrorist attacks . Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly , 81 ( 1 ), 155–167. [ Google Scholar ]

- Branson, D.C. (2019). Vicarious trauma, themes in research, and terminology: A review of literature . Traumatology , 25 ( 1 ), 2–10. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bride, B.E. , Robinson, M.M. , Yegidis, B. , & Figley, C.R. (2004). Development and validation of the secondary traumatic stress scale . Research on Social Work Practice , 14 ( 1 ), 27–35. [ Google Scholar ]

- China Extends Spring Festival Holiday (2020). China extends Spring Festival holiday to contain coronavirus outbreak. The State Council of the People’s Republic of China . Retrieved from: http://english.www.gov.cn/policies/latestreleases/202001/27/content_WS5e2e34e4c6d019625c603f9b.html

- China Internet Network Information Center (2013). The 32nd China Internet Development Statistics Report . Retrieved from: http://www.cnnic.cn/hlwfzyj/hlwxzbg/hlwtjbg/201307/t20130717_40664.htm Accessed 2013 Jul 27.

- Cho, J. , Boyle, M.P. , Keum, H. , Shevy, M.D. , McLeod, D.M. , Shah, D.V. , & Pan, Z. (2003). Media, terrorism, and emotionality: Emotional differences in media content and public reactions to the September 11th terrorist attacks . Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media , 47 ( 3 ), 309–327. [ Google Scholar ]

- Choi, M. , & Toma, C.L. (2014). Social sharing through interpersonal media: Patterns and effects on emotional well‐being . Computers in Human Behavior , 36 , 530–541. 10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.026 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Curran, P.G. (2016). Methods for the detection of carelessly invalid responses in survey data . Journal of Experimental Social Psychology , 66 , 4–19. [ Google Scholar ]

- de Wit, L.M. , van Straten, A. , Lamers‐Winkelman, F. , Cuijpers, P. , & Penninx, B.W.J.H. (2011). Are sedentary television watching and computer use behaviors associated with anxiety and depressive disorders? Psychiatry Research , 186 ( 2–3 ), 239–243. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dong, M. , & Zheng, J. (2020). Letter to the editor: Headline stress disorder caused by Netnews during the outbreak of COVID‐19 . Health Expectations , 23 ( 2 ), 259–260. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Galea, S. , Brewin, C.R. , Gruber, M. , Jones, R.T. , King, D.W. , King, L.A. , … Kessler, R.C. (2007). Exposure to hurricane‐related stressors and mental illness after Hurricane Katrina . Archives of General Psychiatry , 64 ( 12 ), 1427–1434. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gao, J. , Zheng, P. , Jia, Y. , Chen, H. , Mao, Y. , Chen, S. , … Dai, J. (2020). Mental health problems and social media exposure during COVID‐19 outbreak . PLoS One , 15 ( 4 ), e0231924. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Garfin, D.R. , Silver, R.C. , & Holman, E.A. (2020). The novel coronavirus (COVID‐2019) outbreak: Amplification of public health consequences by media exposure . Health Psychology , 39 ( 5 ), 355–357. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goodwin, R. , Palgi, Y. , Hamama‐Raz, Y. , & Ben‐Ezra, M. (2013). In the eye of the storm or the bullseye of the media: Social media use during Hurricane Sandy as a predictor of post‐traumatic stress . Journal of Psychiatric Research , 47 ( 8 ), 1099–1100. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hall, B.J. , Xiong, Y.X. , Yip, P.S.Y. , Lao, C.K. , Shi, W. , Sou, E.K.L. , … Lam, A.I.F. (2019). The association between disaster exposure and media use on post‐traumatic stress disorder following Typhoon Hato in Macao, China . European Journal of Psychotraumatology , 10 ( 1 ), 1558709. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Holman, E.A. , Garfin, D.R. , Lubens, P. , & Silver, R.C. (2019). Media exposure to collective trauma, mental health, and functioning: Does it matter what you see? Clinical Psychological Science , 8 ( 1 ), 111–124. [ Google Scholar ]

- Holman, E.A. , Garfin, D.R. , & Silver, R.C. (2014). Media's role in broadcasting acute stress following the Boston Marathon bombings . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America , 111 ( 1 ), 93–98. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Houston, J.B. , Spialek, M.L. , & First, J. (2018). Disaster media effects: A systematic review and synthesis based on the differential susceptibility to media effects model . Journal of Communication , 68 ( 4 ), 734–757. [ Google Scholar ]

- Jones, N.M. , Garfin, D.R. , Holman, E.A. , & Silver, R.C. (2016). Media use and exposure to graphic content in the week following the Boston Marathon bombings . American Journal of Community Psychology , 58 ( 1–2 ), 47–59. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jones, N.M. , Thompson, R.R. , Dunkel Schetter, C. , & Silver, R.C. (2017). Distress and rumor exposure on social media during a campus lockdown . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America , 114 ( 44 ), 11663–11668. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kramer, A.D.I. , Guillory, J.E. , & Hancock, J.T. (2014). Experimental evidence of massive‐scale emotional contagion through social networks . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America , 111 ( 24 ), 8788–8790. 10.1073/pnas.1320040111 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kristensen, P. , Dyregrov, K. , Dyregrov, A. , & Heir, T. (2016). Media exposure and prolonged grief: A study of bereaved parents and siblings after the 2011 Utøya Island terror attack . Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy , 8 ( 6 ), 661–667. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kroenke, K. , Spitzer, R.L. , & Williams, J.B. (2001). The PHQ‐9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure . Journal of General Internal Medicine , 16 ( 9 ), 606–613. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lachlan, K.A. , Spence, P.R. , & Seeger, M. (2009). Terrorist attacks and uncertainty reduction: Media use after September 11 . Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression , 1 ( 2 ), 101–110. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lenferink, L.I.M. , Eisma, M.C. , de Keijser, J. , & Boelen, P.A. (2017). Grief rumination mediates the association between self‐compassion and psychopathology in relatives of missing persons . European Journal of Psychotraumatology , 8 ( 6 ), 1378052. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li, Z. , Ge, J. , Yang, M , Feng, J. , Qiao, M. , Jiang, R. , … Yang, C. (2020). Vicarious traumatization in the general public, members, and non‐members of medical teams aiding in COVID‐19 control . Brain, Behavior, and Immunity , 1591 ( 20 ), 916–919. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Limaye, R.J. , Sauer, M. , Ali, J. , Bernstein, J. , Wahl, B. , Barnhill, A. , & Labrique, A. (2020). Building trust while influencing online COVID‐19 content in the social media world . The Lancet Digital Health , 2 ( 6 ), e277–e278. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lin, L.Y. , Sidani, J.E. , Shensa, A. , Radovic, A. , Miller, E. , Colditz, J.B. , … Primack, B.A. (2016). Association between social media use and depression among US young adults . Depression and Anxiety , 33 ( 4 ), 323–331. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ludick, M. , & Figley, C.R. (2017). Toward a mechanism for secondary trauma induction and reduction: Reimagining a theory of secondary traumatic stress . Traumatology , 23 ( 1 ), 112–123. [ Google Scholar ]

- Main, A. , Zhou, Q. , Ma, Y. , Luecken, L.J. , & Liu, X. (2011). Relations of SARS‐related stressors and coping to Chinese college students' psychological adjustment during the 2003 Beijing SARS epidemic . Journal of Counseling Psychology , 58 ( 3 ), 410–423. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mallery, P. , & George, D. (2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference . Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [ Google Scholar ]

- Megan, N.M. (2019). Development and validation of the Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale in a sample of social media users . ETD Archive . 1132. Retrieved from: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/etdarchive/1132

- Merchant, R.M. , & Lurie, N. (2020). Social media and emergency preparedness in response to novel coronavirus . JAMA , 323 ( 20 ), 2011–2012. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mor, N. , Doane, L.D. , Adam, E.K. , Mineka, S. , Zinbarg, R.E. , Griffith, J.W. , … Nazarian, M. (2010). Within‐person variations in self‐focused attention and negative affect in depression and anxiety: A diary study . Cognition and Emotion , 24 ( 1 ), 48–62. [ Google Scholar ]

- Muthén, L.K. , & Muthén, B.O. (2012). MPlus: Statistical analysis with latent variables: User's guide (7th edn.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. [ Google Scholar ]

- Neubaum, G. , Rösner, L. , Rosenthal‐von der Pütten, A.M. , & Krämer, N.C. (2014). Psychosocial functions of social media usage in a disaster situation: A multi‐methodological approach . Computers in Human Behavior , 34 , 28–38. [ Google Scholar ]

- Park, C.L. , Aldwin, C.M. , Fenster, J.R. , & Snyder, L.B. (2008). Pathways to posttraumatic growth versus posttraumatic stress: Coping and emotional reactions following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks . American Journal of Orthopsychiatry , 78 ( 3 ), 300–312. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Paul, L.A. , Price, M. , Gros, D.F. , Gros, K.S. , McCauley, J.L. , Resnick, H.S. , … Ruggiero, K.J. (2014). The associations between loss and posttraumatic stress and depressive symptoms following Hurricane Ike . Journal of Clinical Psychology , 70 ( 4 ), 322–332. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pfefferbaum, B. , Newman, E. , Nelson, S.D. , Nitiéma, P. , Pfefferbaum, R.L. , & Rahman, A. (2014). Disaster media coverage and psychological outcomes: Descriptive findings in the extant research . Current Psychiatry Reports , 16 ( 9 ), 464. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pfefferbaum, B. , Nixon, S.J. , Tucker, P.M. , Tivis, R.D. , Moore, V.L. , Gurwitch, R.H. , … Geis, H.K. (1999). Posttraumatic stress responses in bereaved children after the Oklahoma city bombing . Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry , 38 ( 11 ), 1372–1379. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Piotrowski, C. (2015). Mass media use by college students during hurricane threat . College Student Journal , 49 ( 1 ), 13–16. [ Google Scholar ]

- Podsakoff, P.M. , & Organ, D.W. (1986). Self‐reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects . Journal of Management , 12 ( 4 ), 531–544. [ Google Scholar ]

- Silver, R.C. , Holman, E.A. , Andersen, J.P. , Poulin, M. , McIntosh, D.N. , & Gil‐Rivas, V. (2013). Mental‐ and physical‐health effects of acute exposure to media images of the September 11, 2001, attacks and the Iraq War . Psychological Science , 24 ( 9 ), 1623–1634. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Spitzer, R.L. , Kroenke, K. , Williams, J.B. , & Löwe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD‐7 . Archives of Internal Medicine , 166 ( 10 ), 1092–1097. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stieger, S. , & Lewetz, D. (2018). A Week Without Using Social Media: Results from an Ecological Momentary Intervention Study Using Smartphones . Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking , 21 ( 10 ), 618–624. 10.1089/cyber.2018.0070 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thompson, R.R. , Garfin, D.R. , Holman, E.A. , & Silver, R.C. (2017). Distress, worry, and functioning following a global health crisis: A national study of Americans’ responses to Ebola . Clinical Psychological Science , 5 ( 3 ), 513–521. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thompson, R.R. , Jones, N.M. , Holman, E.A. , & Silver, R.C. (2019). Media exposure to mass violence events can fuel a cycle of distress . Science Advances , 5 ( 4 ), eaav3502. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Valkenburg, P.M. , & Peter, J. (2013). The Differential Susceptibility to Media Effects Model . Journal of Communication , 63 ( 2 ), 221–243. [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang, Y. , McKee, M. , Torbica, A. , & Stuckler, D. (2019). Systematic literature review on the spread of health‐related misinformation on social media . Social Science & Medicine , 240 , 112552. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Watson, D. , Clark, L.A. , & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 54 ( 6 ), 1063–1070. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weems, C.F. , Pina, A.A. , Costa, N.M. , Watts, S.E. , Taylor, L.K. , & Cannon, M.F. (2007). Predisaster trait anxiety and negative affect predict posttraumatic stress in youths after Hurricane Katrina . Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 75 ( 1 ), 154–159. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yeung, N.C.Y. , Lau, J.T.F. , Yu, N.X. , Zhang, J. , Xu, Z. , Choi, K.C. , … Lui, W.W.S. (2018). Media exposure related to the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake predicted probable PTSD among Chinese adolescents in Kunming, China: A longitudinal study . Psychological Trauma , 10 ( 2 ), 253–262. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhu, Y. , Fu, K. , Grépin, K. , Liang, H. , & Fung, I. (2020). Limited early warnings and public attention to coronavirus disease 2019 in China, January–February, 2020: A longitudinal cohort of randomly sampled Weibo users . Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness , 1–4. 10.1017/dmp.2020.68 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

Exploring the effects of social media on mental health during COVID

Fariha hanif, mariley polanco, and fatima warda.

The role of social media in COVID-19

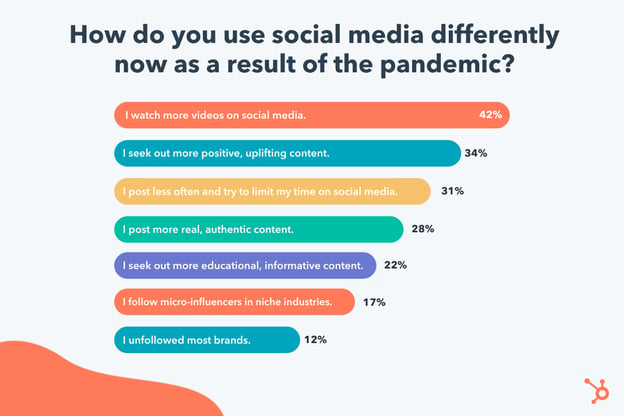

Social media, on an individual basis, is used for keeping in touch with friends and family. This, however, can be expanded to encompass using social media as a networking tool for career options, finding people across the globe with similar interests, and simply as a means to vent their frustrations/emotions. While these applications are still used for similar purposes today, they are most definitely used more frequently as a result of the forced isolation that came about from the pandemic. People who didn’t enjoy using social media and avoided it at all costs as a method of communication have reluctantly given into trying these platforms to stay in touch with their loved ones. Whether it is via the direct messaging features available on various apps or through posting pictures from their daily lives, people try to depict their lives in the best way possible on these virtual platforms. The way social media has been used prior to and during the pandemic has a strong relationship to the idea of the social self.

Especially with the pandemic, social media has brought light to another layer of healthcare. Various healthcare providers created public accounts on these social media platforms, such as YouTube, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Tiktok, and etc. to provide information/updates about what is going on with the pandemic, social distancing guidelines, and updates about the vaccine. In a peer reviewed article published prior to COVID, the authors explored the various benefits and risks of being an active user on social media. Some of these benefits include increasing interactions with others, having more accessible information, social support, and having the potential to influence many policies related to health (Moorhead et al., 2013). Many of these healthcare providers whose following blew up during the pandemic have even branched out into making social media a side gig, taking monetary compensation for everything that they post, even collaborating with major companies to encourage people to stay safe and healthy during the pandemic. A good example is the user @lifeofadoctor on Tiktok, whose following grew exponentially after making daily/weekly updates on COVID statistics during the pandemic to encourage his followers to stay home. His following grew so much in that brief period of time that he was among one of the first few creators on TikTok to be a recipient of $1 billion creator fund.

https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMJgx4KYe/