American Dirt

Jeanine cummins, everything you need for every book you read..

Welcome to the LitCharts study guide on Jeanine Cummins's American Dirt . Created by the original team behind SparkNotes, LitCharts are the world's best literature guides.

American Dirt: Introduction

American dirt: plot summary, american dirt: detailed summary & analysis, american dirt: themes, american dirt: quotes, american dirt: characters, american dirt: symbols, american dirt: theme wheel, brief biography of jeanine cummins.

Historical Context of American Dirt

Other books related to american dirt.

- Full Title: American Dirt

- When Written: 2013–2018

- When Published: January 21, 2020

- Literary Period: Contemporary

- Genre: Novel, Thriller, Migrant Literature

- Setting: Mexico, Arizona, Maryland

- Climax: Lydia, Luca, and a group of migrants undertake a clandestine journey on foot across the border between Mexico and the United States.

- Antagonist: Javier Crespo Fuentes

- Point of View: Third-Person Omniscient

Extra Credit for American Dirt

Is All Press Really Good Press? Many consider Jeanine Cummins’s American Dirt to be one of the most controversial publications in recent history. For the most part, the controversy is due to publicity: preceding publication, American Dirt ’s publisher celebrated the book as “the defining novel” of an era because of its depiction of clandestine migration. In response, a group of outspoken Latino writers and activists (specifically #DignidadLiterary) denounced the work as cultural appropriation (among other accusations), spurring heated conversations about representation gaps and other issues plaguing the publishing industry.

Persistence Pays Off. Jeanine Cummins has stated in an interview she started writing American Dirt in 2013, a full seven years before it was finally published. In fact, she revealed that she’d submitted two failed drafts before hitting her stride. Eventually, the novel was part of a three-day, nine-house auction that resulted in a seven-figure advance for the author.

American Dirt

59 pages • 1 hour read

A modern alternative to SparkNotes and CliffsNotes, SuperSummary offers high-quality Study Guides with detailed chapter summaries and analysis of major themes, characters, and more.

Chapter Summaries & Analyses

Chapters 1-3

Chapters 5-7

Chapters 9-12

Chapters 14-18

Chapters 19-22

Chapters 23-25

Chapters 26-29

Chapter 30-Epilogue

Character Analysis

Symbols & Motifs

Important Quotes

Essay Topics

Discussion Questions

Summary and Study Guide

American Dirt is a work of fiction by Jeanine Cummins published in 2020 by MacMillan Press. This guide refers to the first US edition. The controversial, cross-genre novel combines elements of a commercial thriller, literary fiction, suspense, and romance. The title refers to the land comprising the geopolitical entity that is the United States of America, and to the contempt undocumented migrants face both before and after crossing the US-Mexico border. While many critics initially praised the book for its propulsive plot and poignant treatment of an underrepresented group, others objected to its portrayal of Mexicans; characterizing the novel as stereotypical, opportunistic, and parasitical; while also accusing Cummins of cultural appropriation. A vitriolic debate centering on who can tell which stories emerged in the press and on social media, prompting the publisher to cancel Cummins’s book tour. The book is written in alternating third-person viewpoints. Its moral voice unequivocally lands on the side of migrants, while its simple language creates a sense of immediacy and conveys the terror of the migrant experience.

Plot Summary

Get access to this full Study Guide and much more!

- 7,250+ In-Depth Study Guides

- 5,000+ Quick-Read Plot Summaries

- Downloadable PDFs

Lydia Quixano Pérez , a bookstore owner in Acapulco, saves her son Luca from a massacre that wipes out their entire family at a quinceañera cookout. The perpetrators are three sicarios , killers for Los Jardineros, a violent local cartel. Javier Crespo Fuentes , Lydia’s close friend and the jefe of Los Jardineros, ordered the hit in retaliation for an exposé written by Lydia’s husband, a journalist named Sebastián Pérez Delgado . Javier’s murderous rage stems not from the article itself, but from the impact it has on his daughter, Marta, who commits suicide when she learns of her father’s true identity. Lydia and Luca spend the rest of the novel running from Javier’s men, encountering a diverse cast of migrants along the road to the US.

Lydia gathers necessities from her mother’s house and takes Luca to a hotel using several buses to throw off Los Jardineros. Despite her precautions, a clerk recognizes her and informs Javier. The next morning, Lydia receives a gift from the jefe with a thinly veiled threat. She and Luca flee Acapulco by bus, stopping in Chilpancingo to avoid roadblocks before pressing on to Mexico City. From the capital, they travel by commuter train to Huehuetoca, where Luca witnesses the aftermath of a sexual assault at a migrant facility. The rapist is Lorenzo , a sicario for Los Jardineros. Fearful of Lorenzo, Lydia takes Luca to the train tracks where they meet two beautiful adolescent sisters named Soledad and Rebeca. Luca notices Lorenzo on the train. The sicario recognizes Lydia but claims he is no longer in Los Jardineros and means her no harm. The sisters invite Lydia and Luca to travel with them.

The SuperSummary difference

- 8x more resources than SparkNotes and CliffsNotes combined

- Study Guides you won ' t find anywhere else

- 100+ new titles every month

Lydia, Luca, and the sisters leave Lorenzo behind in Guadalajara and ride La Bestia , freight trains used by migrants, through dangerous Sinaloa territory. Immigration agents intercept the train and load all the migrants except Soledad and Rebeca into vans. When the sisters join the others in a warehouse hours later, it is clear they have been raped. As the only Mexican nationals in the group, Lydia and Luca meet with the commander, who demands a toll for their release. Luca refuses to leave the sisters behind, which prompts Lydia to pay their toll and leaves her penniless. The group meets Beto , a vivacious, asthmatic deportee who is flush with cash.

Soledad contacts a coyote named El Chacal when they arrive in Nogales. He agrees to add Lydia, Luca, and Beto to the group crossing the border , but Lydia does not have enough money. Beto volunteers to pay the difference. The migrants face their first challenge a few hours into the trek when they spy a US Border Patrol drone. Shortly thereafter, they encounter a group of armed vigilantes on the lookout for migrants and an immigration official. Other challenges arise, including a sudden storm and a flash flood that ends the journey north for two members of the group. Lorenzo tries to rape Rebeca, prompting Soledad to shoot him. Lydia finds Lorenzo’s phone and learns he offered her and Luca to Javier in exchange for his freedom from Los Jardineros. The book reaches its climax when Lydia confronts Javier over videocall and Beto dies of an asthma attack. The remaining migrants reach a campsite run by El Chacal’s contacts who drive them to Tucson in hidden compartments in their RVs. The novel ends in Maryland, where Lydia and Luca share a house with Soledad, Rebeca, and the sisters’ relatives.

Don't Miss Out!

Access Study Guide Now

Ready to dive in?

Get unlimited access to SuperSummary for only $ 0.70 /week

Related Titles

By Jeanine Cummins

A Rip in Heaven

Jeanine Cummins

Featured Collections

Audio study guides.

View Collection

Goodreads Reading Challenge

Hispanic & latinx american literature, oprah's book club picks, the best of "best book" lists.

Advertise Contact Privacy

Browse All Reviews

New Releases

List Reviews by Rating

List Reviews by Author

List Reviews by Title

American Dirt

By jeanine cummins.

Book review and synopsis for American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins, a controversial novel about a timely and important topic.

In American Dirt , after her journalist husband runs afoul of cartel boss Javier Fuentes, Lydia’s entire family is murdered with the exception of her young son, Luca. Now, Lydia and Luca must run for their lives to try to leave Mexico despite the many dangers lurking along the difficult journey and with Fuentes and his men nipping at their heels.

Action-packed and suspenseful, American Dirt is a thriller that tells a story about migration into the United States.

(The Full Plot Summary is also available, below)

Full Plot Summary

Lydia Quixano's entire family is gunned down after her journalist husband, Sebastian , publishes an expose on a cartel boss, Javier Fuentes . Javier is the leader of Los Jardineros and had also been a close personal friend of Lydia's. She met him as a customer at her bookstore. Lydia and her 8-year-old son Luca are the sole survivors in the attack, and they must flee Mexico.

Lydia and Luca travel north by bus from Acapulco to Chilpancingo to find Carlos , a friend of Sebastian's. Carlos's wife Meredith puts them in a van pretending to be with a group of American missionaries to get to Mexico City. The goal is to fly to a border city to cross, but at the airport, Lydia has no documentation for Luca. Instead, they continue on foot to Huehuetoca and stay at a migrant shelter. They come across two teen girls, Soledad and Rebeca , who teach them how to get on and off La Bestia, a freight train that migrants commonly hitch a ride on, though it requires jumping onto a moving train. Soledad and Rebeca are from Honduras and are fleeing from a gang leader who has taken an interest in them. Soledad is pregnant by rape. They are headed to Maryland, where their cousin Cesar lives.

On La Bestia, they meet Lorenzo , a man who was part of Los Jardineros and recognizes Lydia as a target they're after, but Lorenzo claims that he is fleeing that lifestyle. Lorenzo tells Lydia that Javier's daughter Marta killed herself three days after learning the secret about her father. At a shelter, the two girls call home to find out their father was stabbed by the man they are running from.

Back on board La Bestia, they ride until immigration agents raid the train. They are then rounded up and taken to a warehouse. As Mexican nationals, Lydia and Luca are free to go (with payment), but Luca demands that they save Soledad and Rebeca. They give up the rest of their money to save them. Soledad miscarries. They continue riding La Bestia and meet a asthmatic, migrant 10-year-old boy, Beto. Together, they all go to Nogales to meet the girls' coyote, El Chacal. Lydia clears out her mother's bank account to pay him $11,000 for her and Luca. They soon find out Lorenzo has hired the same coyote and will be making the two-day journey with them, along with 8 others.

16 days after departing Acapulco, Lydia and Luca cross the border into the United States, but they still have a long trek ahead. One man party breaks his leg and his godfather stays with him so they can go turn themselves into border patrol (as opposed to dying in the desert). The next day, Lorenzo attempts to assault Rebeca, and Soledad shoots him with El Chacal's gun. Lydia finds Lorenzo's cell phone and discovers Lorenzo has been reporting her location to Javier. She calls Javier to tell him that Lorenzo is dead and to leave her alone. In the final leg of the trip, Beto dies from his asthma.

In the epilogue on month later, Lydia and Luca move to Maryland to live with Soledad and Rebeca at their cousin Cesar's house. Lydia gets a job as a house cleaner and the girls are enrolled in school.

For more detail, see the full Section-by-Section Summary .

If this summary was useful to you, please consider supporting this site by leaving a tip ( $2 , $3 , or $5 ) or joining the Patreon !

Book Review

American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins has been the most talked about novel of the new decade so far (though keep in mind that I’m writing this in January 2020), for both good reasons and bad. It was sold in what was reported to be a seven-figure deal and has a movie in the works. It also received praise from a lot of big names like Stephen King, Sandra Cisneros, Ophrah and various literary gatekeepers.

As for the negative buzz, well, there’s been a lot of that, too. More accurately, it’s been accused of being a one-dimensional portrayal of Mexico and being exploitative. Commentators have also pointed out factual inaccuracies about Mexico, an over-reliance on stereotypes, and the strange foreign gaze that the Mexican protagonist has.

So, what’s the deal, and should you read this novel? Since most of the reviews thus far have been largely polarized, either a) willfully ignorant of any criticisms, or b) focused almost entirely on its flaws, I was curious to take a look.

Oprah’s Book Club Pick

The Good Stuff

American Dirt is very much a thriller in that there’s plenty of chases, suspense and a lot of action in the novel. The backstory for the characters and the writing are superior to your standard thriller. Parul Segal wrote a review of it that (accurately) lambastes some of the writing as being tortured or otherwise questionable , but honestly it’s still a large step up from your average thriller. It’s maybe a bit long-winded, but really I think most people will be fine with the writing.

If I hadn’t known about the criticisms, it would not have seemed overtly apparent to me that the book was problematic (with some exceptions, see below). There wasn’t a ton that stuck out to me when I first started reading, beyond a standard level of nit-picks. I would have wondered about the accuracy in general, but I wouldn’t know one way or another since I am neither from Mexico or of Mexican heritage.

To be clear, this is not a book where no effort has been made to do any research. Parts of the novel contain many details which clearly are the result of diligent research. For example, there’s much specificity in discussing conditions on La Bestia, a freight train, and the impact of Programa Frontera Sur, a joint U.S.-Mexican funded initiative to keep migrants off the train. And yet, it’s unfortunate that the result is still a book that has some issues (see below).

The book also does try to incorporate a range of experiences and types of migrants in order to paint a fuller picture of the experience of trying to cross the border, though the main focus is on the journey from Mexico (as opposed to from Central America) since that’s where the story is set. It’s clear the plot has been contorted to some extent to bring in these aspects of the story, but I can understand why Cummins would try to do this. I do think she did a good job of working these things into the narrative. (But of course, how accurate any of these depictions are is questionable, so I take it all with a grain of salt.)

Criticisms & Controversy

In terms of the story, there are quite a few questionable plot decisions and characterizations. Everyone is either a murderer/rapist or a saint, and the characters rarely have to make hard decisions. Our protagonist Lydia is especially saintly, and yet also kind of stupid. Why would she think it wasn’t necessary to have any safety precautions with her husband publishing an expose on a cartel boss? Why does she rely on begging for food when she has thousands of pesos on hand and hundreds of thousands in the bank? Why doesn’t she (a middle-class woman) know that you need documentation to ride a plane?

Meanwhile, Lydia’s son Luca is eight years old but says stuff like “your help would be a significant advantage” when asking for help. Luca also lashes out at random guards, criminals and whatnot, and they all laugh it off because they find him so cute and precocious. I’ve never tried crossing the border, but my instinct is that acting brash, but cute is not a great strategy.

A bigger issue that other reviewers have pointed out is Lydia’s “ foreign gaze ” when it comes to journeying through Mexico. Her reactions do seem oddly similar to how a foreigner would react to situations. Additionally, a noticeably irritating aspect of the story is the repeated references to “brown” skin. It’s just “skin,” okay? Unless there’s something noteworthy about the color, you can just refer to it as “skin.”

Cultural Inaccuracies

In terms of the cultural inaccuracies, I’m not from Mexico or of Mexican heritage so I can’t really assess how accurate the depiction of Mexico is. I will instead rely on what other reviewers have said. Four widely shared articles that are critical of the book can be found here , here , here and here .

For example, an issue that’s been brought up is the stereotypes about Mexico that many feel are pervasive throughout the book. There seems to be a common commentary that it paints Mexico as only being overrun with drugs, crime or corruption and not much else. Furthermore, Cummins throws in a wide range of stereotypically Mexican/Mexican-ish things. Just in the first few chapters, things like quinceañeras, Carne asada, random Spanish words, and so on all make appearances. I’d imagine its similar to if someone wrote a book about an American family that dresses in red, white and blue, eats hot dogs all the time and decorates their house with pictures of eagles.

Another example of the lack of authenticity that has been pointed out by a reviewer on Amazon . The characters wonder why a gang leader is nicknamed “La Lechuza”, which means “the owl”, since owls aren’t scary. The reviewer clarifies that a “lechuza” is more specifically a screech owl that has been considered an omen and harbinger of death in Mexican culture for thousands of years, which any Mexican would know (according to that person).

Of course, the sad fact is that literature, including stuff taught in schools, is rife with inaccuracies and inaccurate portrayals of places or people. Some books, like Conrad’s Heart of Darkness , are blatantly problematic. Others, like Hemingway’s For Whom the Bell Tolls , on further inspection, misrepresent the societies they are depicting and contradict historical records. And then there’s stuff like Robinson Crusoe where it’s a classic but few reading it would assume it was ever meant to be a fact-based story. But these stories all end up shaping our perceptions nonetheless, so it seems like we should be striving for something better.

I also think reviewers should be more honest about what they don’t know. People need to be allowed to write about cultures they are not a part of, or review books from heritages that are not their own. However, when a non-Mexican writer publishes a book about Mexico and a non-Mexican reviewer declares its “authenticity,” any responsible editor should find that highly suspect.

Writing About Other Cultures

As mentioned above, in my opinion, writers must be able to write about people outside of themselves. That said, I think that comes with it the burden of doing the work to portray other cultures or people accurately and responsibly. Furthermore, for sensitive topics, I think that burden is especially high. (If a publisher is worried about that burden, finding writers that have first-hand experience is always an option!)

For example, they have the responsibility to ensure that it’s not full of stereotypes or otherwise exploitative. Unfortunately, American Dirt is guilty of both these things. It leans on stereotypes about Mexico and the treatment of the subject matter feels exploitative to a lot of people. I can certainly see why a publisher choosing to promote a book on a sensitive topic of great importance and relevance without proper diligence would feel extremely exploitative to people who know that place and have lived that pain.

When reporters shove a microphone in someone’s face after they’ve experienced trauma, it’s exploitative. In much the same way, misrepresenting the story and culture of immigrants when those people are currently under attack by U.S. leaders (and using the symbols of their trauma as decoration as parties, see below) shows very poor judgement.

One thing I’ll say in Cummin’s defense is that I doubt she imagined when she submitted the book that it would end up being this large of a release. It’s not to say that it excuses whatever inaccuracies entirely, but I imagine if she’d known it would be so widely read and if she’d had the resources she has now, perhaps some parts of the book would have been shaped differently. And the decision to promote this specific book (over other more authentic voices) is ultimately up to the publisher, not the author. I’ll finally add that I think book twitter has gotten too vitriolic. There is a difference between being critical and being hateful .

More Controversy and Barbed Wire Centerpieces

To make matters worse, the Flatiron Books launch party for American Dirt made the extremely questionable decision to feature barbed wire centerpieces. Honestly, who thought this was a good idea? Would you use nooses as decor to launch a book about America’s racist history? Or small planes as decor for a book about September 11?

Barbed Wire Centerpieces, From Flatiron Book’s American Dirt Launch Party

I don’t doubt that there were many people with only pure intentions in the publishing process. But stuff like this really does reinforce the idea that this is just a big publishing house capitalizing on and exploiting the pain of immigrants without any genuine concern for their plight.

(Author Jeanine Cummins also had a manicure — mirror here in case that link goes down — that many found objectionable.)

Read it or Skip it?

Obviously, a book can be two things at once. American Dirt is a book that tells a well-paced story that is timely and accessible. However, it’s also a book that has many issues and inaccuracies. I wouldn’t rely on it to enhance your understanding of Mexico, and while it does contain some information about the difficulties migrants face, I would also take it all with a grain of salt.

(Furthermore, there are clearly systemic issues that allowed those problems to be ignored on its way to publication. And I think recommending this book without making others aware of the problems with it is a little irresponsible.)

Aside from any cultural stuff, it doesn’t take an expert to know that this story lacks realism in parts. The characterizations are questionable, and there’s an odd lack of hard decisions that need to be made in this situation that necessitates hard decisions. This is not to say the story isn’t suspenseful or interesting for people who enjoy thrillers, though.

I would love to hear others’ opinions on this book! Feel free to drop a comment below. I promise to give any (civil) comment genuine, open-minded consideration, especially when it comes to opposing perspectives. Happy reading!

See American Dirt on Amazon .

Similar Titles

For some other titles dealing in similar territory, check out The Devil’s Highway by Mexican author Luis Alberto Urrea, Fruit of the Drunken Tree by Colombian author Ingrid Rojas Contreras, Children of the Land by Marcelo Hernandez Castillo, or The Affairs of the Falcóns by Melissa Rivero.

Book Excerpt

Read the first pages of American Dirt

Share this post

Fourth Wing

Funny Story

Murder Road

The Housemaid’s Secret

2024’s Best Book Club Books (New & Anticipated)

Best Cozy Mystery Books of 2024

Bookshelf: Development Diary

Best Rom-Com, Beach Reads & Contemporary Romance Books

2024’s Best Rom Com & Romance Books (New & Anticipated)

20 comments

Share your thoughts cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

What an excellent,and balanced piece this is! Having got my own copy and feeling quite awkward about reading and reviewing it,I absolutely feel you nailed both the issues and the responsibilities so well.

Thank you! and yes, I totally agree this was one of the harder reviews to write given that so many people have strong feelings about it and there’s a lot of external stuff going on around it. Thanks for reading!

It’s refreshing to read a balanced review of this book! It doesn’t sound like something I’ll add to my tbr pile, but I’m happy to have read your review.

thank you and thank you for reading! :)

Interesting review, there is certainly a lot of hype and negative press about the book around.

thank you — yeah there’s definitely a lot of commentary about it right now to sift through!

I kept hearing about all the controversy surrounding this book but didn’t have time to read any articles until today, so yours is the first that I’ve read. I really appreciate your suggestions of other, similar books to read as well as the links to four critics. The first link had some book suggestions. Links 2 & 3 seem to take me to the same article?

It was enough for me to hear all the complaints about the bad writing. I will pass on American Dirt for that reason alone.

I made myself a Goodreads shelf called American Dirt opposition and added the books you and Myriam Gurba mentioned to it.

Hi Jinjer — thank you for letting me know about the messed up links, it’s been fixed! Thanks for reading!

I agree with the author’s objections to the book. However, I would not say it’s poorly written, not on the sentence level. I find much of the writing to be strong. The metaphors and word choices are often beautiful.

Thank you for this balanced review, Jennifer! I haven’t read this book, nor am I going to soon… But I’m seeing this going on for about a year now, how an author is also abused instead of only criticised. I think these are the pitfalls of a connected age. And the book has been tagged as a fiction, domestic fiction, thriller. What exactly has happened to the understanding of creative liberties? Middle East has been, is still being, in certain respects, misrepresented. But does it mean that we stop reading works of fiction and appreciating them? I’m from India and knowing the reality about my country, if some author only considers one aspect for their book and sweeps aside all the other things, then I won’t of course treat it as a misrepresentation. And in this connected age, neither will anyone else as long as they read the world news! It is, after all, a work of fiction. I don’t understand the hue and cry.

I started reading this book and since I have been living in Mexico for 15 years, could easily see the errors in the plot story. When I realized Lydia was planning to take the train, I stopped reading to question both the author and the purpose of this book. Thanks for your review. When I saw it was a thriller I realized why the author, not understanding Mexico would distort life here. I do think there is some irresponsible actions of promoting this book because the US main stream media publishes so many false statements about Mexico and this book and this book does the same. I don’t plan to finish the book I don’t read thrillers

My OPINION 1. It shows that what happened to Lydia, a misjudgment of character, trusting those on “face” value, Love Is Blind etc, can happen to anyone “in general”. She was a typical hard working loving mother daughter aunt…that LIFE’s dark side threw curves!

2. It is a “light hearted” look at a horrific topic that too many sheltered people choose to ignore thus I APPLAUD this protected eye opening novel

3. I cannot even watch war or fight sequences and books like this that are too real will not even be given a chance…Luca is a complex character that is delightful and offers a relief and hope just when things need which is not “real”. Unreal books about REAL life circumstance the privileged cannot even begin to ingest let alone digest, crates the perfect taste to wet the appetite for more.

I’m currently reading this book and as someone who is mexican, this book has created mixed feelings for me. I don’t question Jeanine’s freedom of expression, I just wished this book was well researched. There were many missed opportunities through out the book where she could elaborate. I just don’t like the concept of a middle aged woman with lots of money in the bank crossing the country, into the United states and suddenly everything is okay. This book also doesn’t do justice of explaining the beauty that Mexico has. Yes Mexico is controlled by drug cartels, but there is beauty on those lands. There are excellent food options, beautiful buildings from the 1500s, and beautiful beaches. However, I believe this book has become a catalyst for creating the conversation of what is an immigrant, and leading readers to other Latinx stories that are far better than American Dirt.

I was entertained by this book. Though I don’t believe it as a completely accurate portrayal of Mexico and immigrant plight, it still brings awareness to the issue. I think some of the criticisms are justified but I agree with you that they have gotten out of control- some people ARE downright hateful (read Myriam Gurba). I think maybe the people that are uber defensive just don’t like that the dangerous and frightening aspects of their country are being highlighted.

Jules Verne once wrote a book about a submarine. Today we know, that such a submarine cannot be build using the materials he described. It would have not been strong enough to resist the water pressure at the depths he quoted.

So what! Does it make his book less enjoyable? Is it of a lesser value today? And does it matter that Verne could not even swim? How dared he to write about underwater escapades!

I just finished AD,in 3 days, I couldn’t put it down. I also just witnessed the end of President Trumps time in office , and have no doubt that this is the way life has been for the immigrants seeking life here in the USA. This may not represent the entire country of Mexico, but I think it’s a realist read on what immigrants go through to get here. And even worse, what happens if they are detained, now that we all know the realities of his vicious immigration policies. If it is exaggerated at all, so what, it is representive of what an immigrants life is now.

I have lived among many Central Americans and know many Mexicans. I have travelled the whole length of the country by bus. I also have known a woman who has had similar experiences to Lydia. Middle class and who I accompanied to a asylum seeking court appearance because someone was searching for her to kill her. The evidence obtained from Central America was enough to cause the judge to grant her asylum. I also found that I grew to like many of the characters in the book. I was not judging nor do I judge Mexico. The story i read is only one part of how I view Mexico with its “sympatico” people, rich heritage, hard working people, personable caring friends, lively music, a language I have learned to speak, etc.

Almost every book has flaws, big, small…I liked the book. For me it was an interesting personal story of a mother, son and important influencers. It was not meant to learn about Mexican culture. We know how cartels can work. We learn about them every day!

It’s fiction, for cripe sake. I don’t read fiction in order to expand my knowledge, understanding or perspective of the material. If I wish to acquire knowledge of a particular subject, I don’t resort to fiction to do so. It’s a so called thriller. I found it long at times, elaborating on the same scenes. Maybe the breakdown of every meal they ingested was of interest to some, but I found it to be maybe more of accomplishing a word count for the author. All considered, I found the book to be marginally entertaining. I should acknowledge that I read it as a book club assignment. Normally I would avoid any book that Oprah is pontificating on.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Book News & Features

Latinx critics speak out against 'american dirt'; jeanine cummins responds.

Rachel Martin

American Dirt

Buy featured book.

Your purchase helps support NPR programming. How?

- Independent Bookstores

Author Interviews

'american dirt' author jeanine cummins answers vocal critics.

There's a book you might have heard of by now. It's called American Dirt , and it's the much-hyped new novel from author Jeanine Cummins that was released this week.

It's the story of a Mexican woman named Lydia and her 8-year-old son Luca, who flee their home and undertake a harrowing journey to the U.S. border after gunmen from a local drug cartel kill most of their family. It's been hailed as "a Grapes of Wrath for our times." In fact, that quote is on the cover of the book. [Disclosure: Flatiron Books, publisher of American Dirt , is among NPR's financial supporters]

And that is one of the many problems with American Dirt , according to several critics. There have been tweet threads and essays , all arguing that the book deploys harmful stereotypes. Even a hashtag — My Latino Novel — has popped up on Twitter, where people are writing their own parodies. But there is so much more to say about race and identity in publishing, about who gets to tell what stories and which of those voices are elevated in the mainstream culture.

Los Angeles Times writer Esmeralda Bermudez has been one of the most vocal critics of American Dirt . "In 17 years of journalism, in interviewing thousands of immigrants, I've never come across anyone like American Dirt's main character," Bermudez says.

"She's this middle-class, bookstore-owning woman who left Mexico with a small fortune in her pocket, like she was going to go to France or something. With inheritance money. With an ATM to her mom's life savings. And why did she leave? Because she was flirting with a drug lord who's now trying to kill her. This is a wonderful, melodramatic telenovela, something I would love watching for cheap entertainment, like a narco-thriller on Netflix. But this should not be called by anyone 'the great immigrant novel, the story of our time, The Grapes of Wrath .' Why? How did we get to a point in our industry, in the book industry, in society, that this is the low standard that we have?"

Writer Myriam Gurba, another critic of the book , pointed out a particular inauthenticity: "There is a scene where the main character encounters an ice rink. And she's utterly shocked at the existence of this ice rink, as if she's unaware that winter sports are played in Mexico. And I was laughing," Gurba says. "I laughed out loud when I got to that section because I learned to ice skate in Mexico. I learned to ice skate at age 9 in Guadalajara."

Bermudez, like many others speaking out against the book, says that despite the author's intentions, it doesn't reflect the truth of the migrant experience. "My grandfather, my aunt, my uncle were killed in El Salvador at a time of death squads. Death squads sponsored by the U.S. I was separated from my mom, I didn't meet her until I was five because of all this violence. I wanted to see myself reflected in this book. It's painful that not only did I not see myself, but I found all these things that constantly make us feel small."

She says she understands that Americans who aren't migrants themselves or come from migrant families may walk away from this book with a completely different feeling. "This book has left a lot of white readers with this very fuzzy feeling, like, 'Oh my God' about immigrants. And my skin is crawling. My skin is crawling."

We recorded an interview with Cummins, the book's author, last week — an interview that never aired because the criticism of American Dirt started coming down hard, and the conversation about this book had to change. So we called Cummins back. She says she's tried to avoid the criticism, especially on Twitter. When I share some of what's being said, Cummins says, "I don't know how to respond to this. ... Not everyone has to love my book. I endeavored to be incredibly culturally sensitive, I did the work, I did five years of research. The whole intention in my heart when I wrote this book was to try to upend the stereotypes that I saw being very prevalent in our national dialogue. And I felt like there was room ... for us to examine the humanity of the people involved."

Cummins says she's aware of her own privilege, her cultural blind spots and the imbalances in the publishing industry. "And that's not a problem that I can fix, nor is it a problem that I'm responsible for," she says. "All I can do is write the book that I believe in. And I did that."

You can find the rest of my conversation with Cummins here.

This story was produced for radio by Lisa Weiner and Reena Advani, and adapted for the Web by Petra Mayer.

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

Why Everyone’s Talking About American Dirt

The controversy about jeanine cummins’ novel encompasses appropriation, cries of silencing, and four separate new york times stories..

Why is literary Twitter piling on Jeanine Cummins’ American Dirt , once one of the most highly anticipated books of the year? After an intense bidding war among nine houses that ended in a reported seven-figure deal, the novel landed on both the New York Times’ and LitHub’s 2020-in-reading lists. It’s in stores Tuesday, accompanied by praise from heavyweights like Stephen King, Sandra Cisneros, and Don Winslow—the last of whom compared the migrant drama novel to John Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath . A film adaptation is already in the works by the same company that produced Clint Eastwood’s The Mule.

But an increasingly vocal contingent of Mexican and Mexican American writers has panned the novel as “ trauma porn ,” pointing out myriad inconsistencies and errors in Cummins’ descriptions of Mexico that a largely American, non-Spanish-speaking industry of agents, editors, and publicists seemed to not have been able to notice.

Over the long weekend, the slowly brewing clash spilled onto the pages of the New York Times books section. Here’s what’s going on.

American Dirt follows the journey of a mother and son fleeing Mexico for America after their entire family is murdered on the orders of a local cartel kingpin. Before the slaughter, Lydia Quixano Pérez is a bookseller in Acapulco, mother to Luca and wife to journalist Sebastián. It is Sebastián’s exposé on the kingpin, who also happens to be a frequent customer of Lydia’s bookstore, that serves as the linchpin for the violence that sets off the novel and Lydia’s journey through the desert to the border.

In her afterword Cummins describes a four-year writing process that included extensive travel and interviews in Mexico. Cummins writes of her desire to humanize “the faceless brown mass” that she believes is so many people’s perception of immigrants. “I wish someone slightly browner than me would write it,” she continues. “But then I thought, if you’re the person who has the capacity to be a bridge, why not be a bridge .” I’m sure you can see where this bridge is going.

The Backlash

At first glance, the criticism of American Dirt reads as the increasingly pro forma conversation about who’s allowed to tell whose story. On one side are Mexican and Mexican American writers asking why Cummins felt the need to tell this story, other than to individuate a “faceless brown mass” that she’s not a part of—simultaneously raising the question of who exactly sees that mass as faceless and whether it’s worth writing for them. On the other side is Cummins raising a familiar alarm on how conversations around cultural appropriation will eventually morph into censorship. In a profile in the Times touching on the controversy, she said, “I do think that the conversation about cultural appropriation is incredibly important, but I also think that there is a danger sometimes of going too far toward silencing people.”

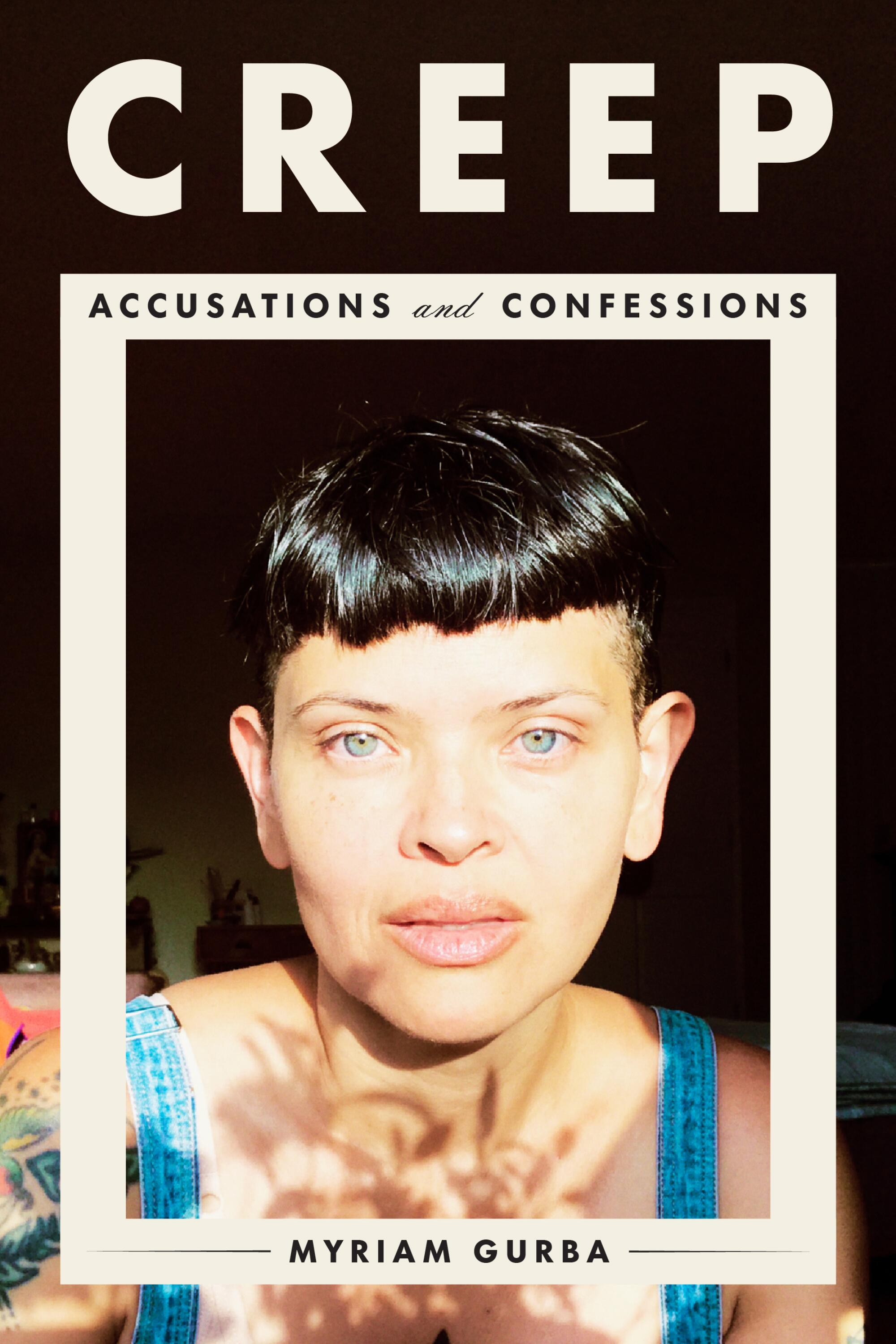

The public debate began with a review of American Dirt by Myriam Gurba * published in Tropics of Meta, an academic blog that publishes essays on a broad range of topics. Gurba takes to task not only Cummins’ identity—she apparently identified as white as recently as four years ago, when she wrote in the New York Times that she wasn’t qualified to write about race—but also American Dirt ’s similarity to other books about Mexico that Cummins used for research, as well as the novel’s ignorance of the very people the book purports to represent. “That Lydia is so shocked by her own country’s day-to-day realities […] gives the impression that Lydia might not be … a credible Mexican,” Gurba writes. “In fact, she perceives her own country through the eyes of a pearl-clutching American tourist.”

Gurba also dropped that she was originally assigned to review American Dirt by “an editor at a feminist magazine”—later revealed to be Ms. While her editor thought the review was “spectacular,” Gurba wrote, it was nonetheless killed because Gurba “lacked the fame to pen something so ‘negative.’ ”

Though Gurba’s review was published over a month ago, in the days before American Dirt hit the shelves it was shared again and again . Writers like Jose Antonio Vargas and Viet Thanh Nguyen publicly called for Ms. to account for why they decided to kill the review.

The New York Times

But the pan with the biggest reach came this weekend when Parul Sehgal wrote for the New York Times’ daily Books of the Times section that “this peculiar book flounders and fails.” Two days later, the Times Book Review published Lauren Groff’s conflicted review , which makes the case that the novel “was written with good intentions, and like all deeply felt books, it calls its imagined ghosts into the reader’s real flesh.”

What’s literary drama without the Gray Lady? The differences between Sehgal’s and Groff’s reviews were noted as soon as the latter published on Sunday. Soon after Groff’s review dropped, it was linked from the Book Review’s Twitter account with a line more complimentary than any that exists in the published review: “ ‘American Dirt’ is one of the most wrenching books I have read in the past few years, with the ferocity and political reach of the best of Theodore Dreiser’s novels.” Groff responded, “Please take this down and post my actual review.” (She added, “ Fucking nightmare .”) The tweet, according to Groff and, later, New York Times Book Review editor Pamela Paul , had mistakenly been pulled from an earlier draft of the review—one that perhaps started out more positive about American Dirt than it ended up. Groff seemed to agonize over the review in public, eventually tweeting, “I give up. Obviously I finished my review long before I knew of Parul’s—anyone who has gone through edits knows the editing timeline—but hers is better and smarter anyway. I wrestled like a beast with this review, the morals of my taking it on, my complicity in the white gaze.”

Once upon a time, books frequently received reviews from both the daily Times and the Book Review, but that’s much rarer now. These days it happens only to the most newsworthy or most highly anticipated books—which often happen to be their publishers’ seasonal lead titles, the ones that get the biggest publicity budgets. In addition to those reviews, the Times also published an excerpt for some reason. Oh, and the profile. All of which makes Cummins’ fears—stated in the New York Times!—about being “silenced” seem a bit silly. For the big-money book publicity machine to wield its influence on behalf of a novel about the Mexican immigrant experience written by a non-immigrant, non-Mexican author—when books by Mexican and Mexican American writers often struggle to see daylight—is another reminder of what the industry deems valuable. Cummins’ good intentions have largely been acknowledged, but as Rebecca Makkai wrote in LitHub last year —and linked to on Tuesday , “apropos of nothing”—“I [can’t] good-person myself into good writing.”

Still, the conversation seems to have reached its peak and is calming down. Let’s just hope Oprah doesn’t pick American Dirt for her book club or anything .

Correction, Jan. 21, 2020: This piece originally misspelled Myriam Gurba’s last name.

- Newsletters

Site search

- Israel-Hamas war

- 2024 election

- Kate Middleton

- TikTok’s fate

- Supreme Court

- All explainers

- Future Perfect

Filed under:

The controversy over the new immigration novel American Dirt, explained

A non-Mexican author wrote a book about Mexican migrants. Critics are calling it trauma porn.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Twitter

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: The controversy over the new immigration novel American Dirt, explained

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/66149746/1195327207.jpg.0.jpg)

The new novel American Dirt by Jeanine Cummins, officially released on January 21, was anointed the biggest book of the season well before it came out.

It sold to Flatiron Books at auction for a reported seven-figure advance . Flatiron announced a first print run of 500,000 copies. (For most authors, a print run of 20,000 is pretty good .) It received glowing blurbs from luminaries like Stephen King, John Grisham, and Sandra Cisneros. Early trade reviews were rapturous . The New York Times had it reviewed twice — once in the daily paper, once in the weekly Book Review — in addition to interviewing the author and publishing an excerpt from the novel.

But as the publication date approached, the narrative around American Dirt has changed. One of those New York Times reviews was a pan , the other was mixed at best . Another critic revealed that she’d written a review panning the book, too, and the magazine that commissioned her review killed it.

All of these negative reviews centered on one major problem: American Dirt is a book about Mexican migrants, and author Jeanine Cummins has identified as white , calling her family mostly white “in every practical way” a few years ago. ( She has since begun to discuss a Puerto Rican grandmother .) Cummins had written a story that was not hers — and, according to many readers of color, she didn’t do a very good job of it. In fact, she seemed to fetishize the pain of her characters at the expense of treating them as real human beings.

So last week, when Oprah announced that American Dirt would be the next book discussed in her book club, the news was treated not as the crown jewel in the coronation of the novel of the season, but as a slightly awkward development for Oprah . Oprah ended up qualifying her choice , maintaining that she would keep the book in her club, but change her planned coverage of it to a series of conversations with those on “both sides” of the issue.

Oprah, lounging in a silk robe, sipping her morning coffee, copies of Groff's and Seghal's reviews of AMERICAN DIRT on the coffee table. She picks up her phone and thinks: I'll show these literary girls what chaos is — joshua gutterman tranen (@jdgtranen) January 21, 2020

Meanwhile, in the wake of the controversy, Flatiron has canceled Cummins’s book tour , citing threats to both Cummins and to booksellers. And some of American Dirt ’s critics say they have received threats, too.

The story of American Dirt has now become a story about cultural appropriation, and about why publishing as an industry chose this particular tale of Mexican migration to champion. And it revolves around a question that has become fundamental to the way we talk about storytelling today: Who is allowed to tell whose stories?

“I wished someone slightly browner than me would write it”

American Dirt is a social issues thriller. It tells the story of a mother and son, Lydia and Luca, fleeing their home in Acapulco, Mexico, for the US after the rest of their family is murdered by a drug cartel. Lydia is a bookstore owner who never thought of herself as having anything in common with the migrants she sees on the news, but after she comes up with the plan of disguising herself by posing as a migrant, she realizes that it won’t really be a disguise: It’s who she is now.

In her author’s note, Cummins explains that she wrote American Dirt in an attempt to remind readers — presumably white readers — that Mexican migrants are human beings. “At worst, we perceive them [migrants] as an invading mob of resource-draining criminals, and, at best, a sort of helpless, impoverished, faceless brown mass, clamoring for help at our doorstep,” she writes. “We seldom think of them as our fellow human beings.”

Cummins also says in the note that she recognizes that this story may not be hers to tell, while stressing that her husband is an immigrant and that he used to be undocumented. She does not include in the note the fact that her husband immigrated to the US from Ireland, an elision that some observers have taken to be strategic, as though Cummins wishes to give the impression that her husband is Latino and could have been in just as much danger of being held in a cage at the border as the people she is writing about.

“I worried that, as a nonmigrant and non-Mexican, I had no business writing a book set almost entirely in Mexico, set entirely among migrants. I wished someone slightly browner than me would write it,” Cummins says. (It is worth noting at this juncture that plenty of people who are slightly browner than Cummins have in fact written about Mexican migration.) “But then, I thought, If you’re a person who has the capacity to be a bridge, why not be a bridge ?” Cummins continues. And so she spent years working on this book, traveling on both sides of the border and interviewing the people she met there.

American Dirt is explicitly addressed to non-Mexican readers by a non-Mexican author, and it is framed as a story that will remind those readers that Mexican migrants are human beings. And for some readers, including some Latinx readers, Cummins was successful in her aims. In her blurb for the book, the legendary Mexican American author Sandra Cisneros declared herself a fan, writing, “This book is not simply the great American novel; it’s the great novel of las Americas . It’s the great world novel! This is the international story of our times. Masterful.”

But for other readers, American Dirt is a failure. And it fails specifically in achieving its ostensible goal: to appreciate its characters’ humanity.

“It aspires to be Día de los Muertos but it, instead, embodies Halloween”

The first true pan of American Dirt came out in December , on the academic blog Tropics of Meta. In it, the Chicana writer Myriam Gurba takes Cummins to task for “(1) appropriating genius works by people of color; (2) slapping a coat of mayonesa on them to make palatable to taste buds estados-unidenses and (3) repackaging them for mass racially ‘colorblind’ consumption.”

Gurba describes American Dirt as “trauma porn that wears a social justice fig leaf,” arguing, “ American Dirt fails to convey any Mexican sensibility. It aspires to be Día de los Muertos but it, instead, embodies Halloween.” Most especially, she critiques the way Cummins positions the US as a safe haven for migrants, a utopia waiting for them outside of the bloody crime zone of Mexico. “Mexicanas get raped in the USA too,” she writes. “You know better, you know how dangerous the United States of America is, and you still chose to frame this place as a sanctuary. It’s not.”

Moreover, Gurba notes that American Dirt has received the kind of institutional support and attention that books about Mexico from Chicano authors rarely do. “While we’re forced to contend with impostor syndrome,” she writes, “dilettantes who grab material, style, and even voice are lauded and rewarded.”

Gurba originally wrote her review for Ms. magazine, but it never appeared there. “I had reviewed for them before,” Gurba told Vox over email. But this time, “when they received my review, they rejected it, telling me I’m not famous enough to be so mean. They offered to pay me a kill fee but I told them to keep the money and use it to hire women of color with strong dissenting voices.”

Gurba says she’s had a mostly positive response to her review, “except for the death threats.” She maintains that American Dirt is a very bad book.

“ American Dirt is a metaphor for all that’s wrong in Big Lit,” she says: “big money pushing big turds into the hands of readers eager to gobble up pity porn.”

“I was sure I was the wrong person to review this book”

Gurba’s review established the counternarrative on American Dirt , but that narrative didn’t become the dominant read until January 17. That’s when the New York Times published a negative review by Parul Sehgal , one of the paper’s staff book critics.

“Allow me to take this one for the team,” Sehgal wrote. “The motives of the book may be unimpeachable, but novels must be judged on execution, not intention. This peculiar book flounders and fails.”

Sehgal, who is of Indian descent, says she believes in the author’s right to write about “the other,” which she argues fiction “necessarily, even rather beautifully” requires. But American Dirt , she says, fails because of the ways it seems to fetishize its characters’ otherness: “The book feels conspicuously like the work of an outsider,” she writes.

And, putting aside questions of identity and Cummins’s stated objective, Sehgal finds that American Dirt fails to make the argument that its characters are human beings. “What thin creations these characters are — and how distorted they are by the stilted prose and characterizations,” she says. “The heroes grow only more heroic, the villains more villainous.”

Two days after Sehgal’s review came out in the daily New York Times, the paper published another review from the novelist Lauren Groff in its weekly Book Review section . Groff, who is white, was less critical of American Dirt than Sehgal was, but her review was far from an unmitigated rave: It wrestles with a number of questions over whether Cummins had the right to write this book.

But you would not know as much from the Book Review’s Twitter account, which posted a link to Groff’s published review with a quote that appears nowhere within it. “‘American Dirt’ is one of the most wrenching books I have read in the past few years, with the ferocity and political reach of the best of Theodore Dreiser’s novels,” said the now-deleted tweet.

“Please take this down and post my actual review,” Groff responded .

According to Book Review editor Pamela Paul , the tweet used language from an early draft of Groff’s review and was an unintentional error. But for some observers, that tweet, combined with the deluge of coverage the New York Times was offering Cummins, made it appear that the paper had an agenda: Was it actively trying to make American Dirt a success?

The Times’s intentions aside, in her review, Groff treats American Dirt as a mostly successful commercial thriller with a polemic political agenda, as opposed to Sehgal, who treated it as a failed literary novel. (Arguably, Groff is being truer to the aims of American Dirt ’s genre than Sehgal was, but given that American Dirt is a book whose front cover contains a blurb calling it “a Grapes of Wrath for our times,” it’s hard to say that Sehgal’s expectations for literary prose were unmerited.) Groff praises the novel’s “very forceful and efficient drive” and its “propulsive” pacing, but she also finds herself “deeply ambivalent” about it.

“I was sure I was the wrong person to review this book” as a white person, she writes, and became even more sure as she learned that Cummins herself was white. Groff spends much of her review wrestling with her responsibility as a white critic of a novel addressed to white people by a white author about the stories of people of color, and ends without arriving at a satisfying answer. “Perhaps this book is an act of cultural imperialism,” she concludes; “at the same time, weeks after finishing it, the novel remains alive in me.”

On Twitter, Groff has called her review “deeply inadequate,” and said she only took the job in the first place because she didn’t think the Times would ask anyone else who was willing to wrestle with the responsibility of criticism in the course of reviewing it. “Fucking nightmare,” she tweeted .

Fucking nightmare. — Lauren Groff (@legroff) January 19, 2020

In the wake of these reviews, the American Dirt controversy coalesced around two major questions. The first is an aesthetic question: Does this book fetishize and glory in the trauma of its characters in ways that objectify them, and is that objectification what always follows when people write about marginalized groups to which they do not belong?

The second is a structural question: Why did the publishing industry choose this particular book — about brown characters, written by a white woman for a white audience — to throw its institutional force behind?

“Writing requires you to enter into the lives of other people”

The aesthetic question is more complicated than it might initially appear. People sometimes flatten critiques like the one American Dirt is facing into a pat declaration that no one is allowed to write about groups of which they are not a member, which opponents can then declare to be nothing but rank censorship and an existential threat to fiction: “If we have permission to write only about our own personal experience,” Lionel Shriver declared in the New York Times in 2016 , “there is no fiction, but only memoir.”

But the most prominent voices in this debate have tended to say that it is entirely possible to write about a particular group without belonging to it. You just have to do it well — and part of doing it well involves treating your characters as human beings, and not luxuriating in and fetishizing their trauma.

In another New York Times essay in 2016 , Kaitlyn Greenidge described reading a scene written by an Asian American man that described the lynching of a black man. She strongly felt that this author had the right to write such a scene, she says, “because he wrote it well. Because he was a good writer, a thoughtful writer, and that scene had a reason to exist besides morbid curiosity or a petulant delight in shrugging on and off another’s pain.”

Brandon Taylor made a similar point at LitHub earlier in 2016 , arguing that successful writers have to be able to write with empathy. “Writing requires you to enter into the lives of other people, to imagine circumstances as varied, as mundane, as painful, as beautiful, and as alive as your own,” Taylor said. “It means graciously and generously allowing for the existence of other minds as bright as quiet as loud as sullen as vivacious as your own might be, or more so. It means seeing the humanity of your characters. If you’re having a difficult time accessing the lives of people who are unlike you, then your work is not yet done.”

Critics of American Dirt are making the case that Cummins has failed to do the work of empathy. They are arguing that she has the right to write from the point of view of Mexican characters, but that they have the right to critique her in turn, and that what their critiques reveal is that she does not see the humanity of her characters. They are arguing that instead, American Dirt has done the opposite of what Greenidge applauded that lynching scene for accomplishing. That the book has failed to suggest “a reason to exist besides morbid curiosity or a petulant delight in shrugging on and off another’s pain.”

It’s in the spirit of that reading — of American Dirt as a failure in empathy, as trauma porn — that Gurba noted on Twitter that an early book party that Flatiron Books created for Cummins featured barbed wire centerpieces.

pic.twitter.com/6W8suWpCUD — Myriam Chingona Gurba de Serrano (@lesbrains) January 22, 2020

Flatiron has issued an official apology for those centerpieces, saying, “We can now see how insensitive those and other decisions were, and we regret them.” But for critics of the novel, the central problem remains. Those barbed wire centerpieces are all about the aesthetic splendor of migrant trauma, about the idea of reveling in the thrill of the danger that actual human beings have to deal with every day, without ever worrying that you personally might be threatened. They’re a fairly good illustration of what the phrase “trauma porn” means.

“I only know one writer of color who got a six-figure advance and that was in the ’90s”

The institutional questions about American Dirt are more quantitative. They progress like this: There are plenty of authors of color writing smart, good stories about their experiences. And yet American Dirt , a novel written by a white woman for a white audience, is the book about people of color that landed the seven-figure advance and a publicity budget that could result in four articles in the New York Times. Why has publishing chosen to allocate its resources in this way?

Flatiron Books has defended its choice. “Whose stories get told and who can tell them are important questions,” said Amy Einhorn, Cummins’s acquiring editor and Flatiron’s founder, in a statement emailed to Vox. “We understand and respect that people are discussing this and that it can spark passionate conversations. In today’s turbulent times, it’s hopeful and important that books still have power. We are thrilled that some of the biggest names in Latinx literature are championing American Dirt .”

It is worth pointing out here that Einhorn, a well-respected industry vet, was also the acquiring editor of the 2009 novel The Help , a novel by a white woman about black women in the 1950s. The Help was a bestseller and a major success, but it was also the subject of a critique similar to the one American Dirt is experiencing now , with readers arguing that The Help gloried in fetishizing the pain of its subjects.

Meanwhile, authors of color say they rarely see publishers investing the kind of money and support in their books on the level that The Help and American Dirt received.

“I got sexually assaulted by a serial killer in 1996. I wrote a book about that . Most of the subjects in that book are Mexicans and Chicanx. I got paid $3,000 for my story,” Gurba says. “So yes, the publicity surrounding American Dirt is unfamiliar to say the least.”

“I’ve always had five-figure advances ( my fourth book comes out this spring ) and many of my friends have gotten four figures — and they are mostly writers of color,” said the novelist Porochista Khakpour in an email to Vox. “I only know one writer of color who got a six-figure advance and that was in the ’90s.”

Khakpour adds that the level of hyperbolic attention American Dirt has received, especially from the New York Times, is deeply unusual for publishing. “I only got a Sunday [New York Times Book Review] review for my first novel and that felt like a miracle,” she says. “Again, most writers of color I know are published by indies or academic presses, and it’s hard for them to get the attention of the Times. I write for the NYTBR and I can honestly say I’ve never seen this much attention given to a book — I find it embarrassing.”

Both Khakpour and Gurba argue that American Dirt was appealing to publishers because white people tend to be most comfortable reading about people of color as objects of suffering.

“Certain narratives that flirt with poverty porn make liberal white people feel good about their opinions,” Khakpour says. “They feel like they learn something, like by reading these accounts they are somehow participating in helping the world they usually feel so helpless about.”

Gurba says many white people expect to see her enact such narratives herself and become angry when she doesn’t. “Recently, a white woman got angry at me when she found out that I’m Mexican,” Gurba says. “She insisted that I didn’t look or act Mexican and that I had confused her. But she confused herself. She had a stereotype of what Mexicans are. I defied it. That made her uncomfortable. Now, apply that scenario to the literary equation [ American Dirt has] presented.”

The narratives Gurba and Khakpour suggest both assume that the decision-makers on American Dirt were white. And there is very good reason for that assumption: Publishing is an extremely white industry.

According to the trade magazine Publishers Weekly, white people made up 84 percent of publishing’s workforce in 2019 . Publishing is staffed almost entirely by white people — and in large part, that fact can be explained by publishing’s punishingly low entry-level salaries.

A job as an editorial assistant pays around $30,000, and it likely means living in New York City, where conservative estimates generally say you need an annual salary of about $40,000 before taxes to get by . But landing a position as an editorial assistant is generally a promotion: To get one, you usually have to spend a season or two working as an intern first, for low or no pay.

Such salaries mean that the kind of people who work in publishing tend to be the kind of people who can afford to work in publishing: those who are carrying little student debt and who can rely on their parents to supplement their salaries as necessary. And mostly, those people tend to be white.

As a result, publishing is predominantly staffed with well-meaning white people who, when looking for a book about the stories of people of color, can find themselves drawn toward one addressed specifically to white people — and who will lack the expertise to question that book’s treatment of its characters. Which means that as long as publishing continues to be overwhelmingly, monolithically white, it will continue to find itself mired in controversies like the one surrounding American Dirt .

Update: This story was originally published on January 22, 2020. It has been updated to include news of Cummins’s book tour cancellation, Oprah’s plan for discussing American Dirt as part of her book club, and Flatiron’s statement of apology for the barbed wire centerpieces.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

At Vox, we believe that clarity is power, and that power shouldn’t only be available to those who can afford to pay. That’s why we keep our work free. Millions rely on Vox’s clear, high-quality journalism to understand the forces shaping today’s world. Support our mission and help keep Vox free for all by making a financial contribution to Vox today.

We accept credit card, Apple Pay, and Google Pay. You can also contribute via

Next Up In Culture

Sign up for the newsletter today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

Thanks for signing up!

Check your inbox for a welcome email.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

The battle for blame over a deadly terror attack in Moscow

We’re long overdue for an Asian lead on The Bachelor franchise

The House GOP just gave Biden’s campaign a huge gift

Kate Middleton’s cancer diagnosis is part of a frightening global trend

The disappearance of Kate Middleton, explained

3 Body Problem, explained with the help of an astrophysicist

The “American Dirt” Controversy: Lessons for Writers on Getting Cultures Right

Author Jeanine Cummins has been attacked on social media for sensationalizing the Mexican migration with lurid violence and stereotypical characters in her book. Photo courtesy of Flatiron Books

The American Dirt Controversy: Lessons for Writers on Getting Cultures Right

A conversation with cuban-american author dariel suarez (grs’12), education director at creative writing center grubstreet.

Not many people have a more informed perspective on the controversy swirling around American Dirt , the wildly hyped best-selling novel about a Mexican mother and her son escaping to the United States, than Latino writer Dariel Suarez.

American Dirt ’s author, Jeanine Cummins, identifies herself as white and Latina. She received a seven-figure advance for her book, which has raised questions about how the publishing industry chooses which books, and writers, to aggressively promote, how authors approach writing about marginalized people from other cultures, and how the story of immigration, one of the most politically charged issues in the United States today, gets told.

As education director at GrubStreet , a nonprofit writing center in Boston, Suarez (GRS’12), who has an MFA in creative writing, spends a lot of time thinking about these kinds of questions.

Cummins has been attacked on social media for sensationalizing the Mexican migration with lurid violence and stereotypical characters. Her publisher, Flatiron, was criticized for promoting a soap opera-ish page turner as the immigration novel of our times—and throwing a book party with barbed-wire-festooned centerpieces—while overlooking talented Latinx authors who have written about the subject with greater nuance and complexity. Flatiron has since apologized for how it positioned and publicized the novel, and its parent company, Macmillan, has pledged to substantially increase its numbers of Latinx authors and staff.

Suarez was recently awarded first prize at the International Latino Book Awards for Best Collection of Short Stories in English for A Kind of Solitude (Willow Springs Press, 2019). His first novel, about a Cuban family navigating government censorship, social media, and migration, is due out next year from Red Hen Press.

BU Today sat down with Suarez to talk about American Dirt and what he tells students who want to write about people who are different from them.

With Dariel Suarez

Bostonia: some people say that this is about cultural appropriation, that a white american woman shouldn’t have written a novel about the mexican migration. how do you feel about that.

Suarez: I have a fundamental problem with framing the conversation through the lens of how do people write in the call-out culture—are folks allowed to write about people who are different from them—because that’s just code for, “Can white people write about people who are not like them—who are not from the same race or culture—without getting criticism?” To me, that’s centering the conversation on whiteness. It’s complicated. It’s not just POC [people of color] calling people out on Twitter, which is one part of it, but it’s also POC having more of a voice, which I think is a good thing… Now you have to consider a larger, more diverse audience if you want to be a good writer. My perspective—and I think that of most critics and most readers—is that we aren’t saying you can’t write about a person who’s different from you, who’s from a different culture. That’s not what this is about.

Taking one for the team this week. Was curious about the season’s supposed big, breakout novel. If only books could be reviewed for their intention not execution.. https://t.co/0Ski959YHY — Parul Sehgal (@parul_sehgal) January 17, 2020

Bostonia: Are you talking about fiction?

Suarez: Yes, but also any type of writing when it gets into culture and the way that an audience reads it. The point that’s being made is that if you are going to write outside of your own culture, or from a position of privilege, that you do so thoughtfully, that you engage with people in those communities—that you have them read your work and give you feedback. And that you also interrogate—why should you be the one telling the story? How am I doing it? Who is reading it and giving me feedback? Where are my blind spots? Where am I not doing enough of the cultural work? Those, to me, are legitimate questions that should be part of the artistic process. I’m Cuban, I was born in Cuba. I grew up in Cuba until I was a teenager, when I came to the United States. In fiction and in my nonfiction and in my poetry, I’ve written about Cuba and about people and places that have nothing to do with me. I’ve written outside of my race. I’m light-skinned and I’ve written about black characters. And I’ve written about women. I always have people read the work and critique it from a craft perspective, but also to highlight anything in the content that seems problematic or not nuanced enough or unclear. I’ve been called out by my wife on things in my novel—this chapter, this scene, it just reads as a little bit sexist, did you intend for the characters to be that way? That’s valuable criticism.

Bostonia: Have you made changes in your writing based on that feedback?

Suarez: Yes. I want to make sure the cultural details in my stories about Cuba are as true to life as I can make them, based on the people who are reading these stories, who may have even more experience than I did because I left the country when I was young. I give the benefit of the doubt to writers that they have good intentions. I think they have the right to be curious and to explore and to write about people who are different from them. And, in fact, they are doing it. They’re getting seven figures for it. It’s funny how people talk about censorship. I come from a country where censorship is the real thing, and it’s nothing like what these people claim here. If you’re getting seven figures for a book, if Oprah is picking your book [ American Dirt is Winfrey’s latest book club selection], if you’re getting a lot of attention, I don’t believe that’s censorship. Now, if you’re being criticized, that’s different. Some people can get personal, they can make threats—that’s crossing a line. There’s no place for that in any conversation.

Suarez: But the bigger point is—there is a community of people telling you there’s something wrong with this book. And you should listen and say, “Let me engage, let me see where I failed because obviously it’s not resonating with the community that I’m writing about.” But that’s often not their [the writers’] reaction and I think that’s where people get frustrated.

Bostonia: What do you tell your students about writing about the so-called other?

Suarez: I tell my students you can write about anyone and any place you want. You should be ambitious in your work and write about what you don’t know as a way to learn, as a way to inhabit other people and to develop empathy. Then you should have people read the work and check you on your blind spots. Your job is to make it nuanced, to not rely on stereotypes and not fall into the lazy pitfall of writing a character that you only define through two or three characteristics and put into a box, instead of saying, “I want to have a complex, interesting, layered human being who happens to be this way and these are the ways it manifests in the story.” And also to not assume that folks identify themselves only through one lens. I think stereotypes happen when you write about a black character and everything in the story is defined through the lens of the fact that they’re black. That’s not how we think about ourselves. I don’t think of myself as Cuban, Latino, every second of the day. I’m human, I’m a metalhead. I like heavy metal music. That’s a part of my life that’s important to me. So if I were to write about myself, that would be something that I would want to explore, maybe even more so at times than the fact that I’m Latino or Latinx. At GrubStreet we emphasize content, which encompasses context, alongside craft as part of the conversation. Any social, cultural, gender, racial stuff that might be part of the writing—we lean into that conversation. We believe inclusion and diversity are directly tied to artistic excellence—we don’t separate the two. The goal is the same: let’s be better writers—and better people.

You should write about what you don’t know as a way to learn, as a way to inhabit other people and to develop empathy. —Dariel Suarez

Suarez: It’s all complicated and it’s never going to be perfect. I think our approach, which is starting to come more to the forefront, is, hopefully, creating generations of writers who will be more aware of the cultural importance of their work and their audience. I think what happens to a lot of these writers: they grow up in a bubble, they study and get feedback and praise in a bubble, and then reality hits when the book comes out and people say, “Hey, you forgot about us, you didn’t take into account how we would feel about your book.” This is not about censorship. Any writer is susceptible to a Twitter storm. Unfortunately, that’s the reality that we live in. It’s how you respond and how you engage with it and how you grow from it and how you improve your work that I think matters. And I think that’s also often not central to the conversation.

Bostonia: Have you read American Dirt ?

Suarez: I’ve read a few chapters, and I’ve read a few of the reviews that did a good job of delineating some of the issues. For anyone in that culture [Mexican], I can understand why it would feel problematic. Based on the chapters that I read, I felt like the use of Spanish was at times laughable. It felt badly done, artistically. And also some of the names and details felt like stereotypical telenovela, soap opera. But the frustrating part to me is more than just the the artistic failure—it’s that in publishing they keep giving money and privilege to writers who are not within the culture. And then so many other writers who are writing about the same things in a more complex and nuanced way are not getting the money, the attention. It’s very disheartening for writers to look at the way the publishing industry is run and then to see people get so up in arms when they get criticized. Work, art—it’s up for being socially and culturally criticized. That comes with the territory, especially with such a high-profile book.

Explore Related Topics:

- Creative Writing

- Immigration

- Share this story

- 15 Comments Add

Senior Contributing Editor