- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

The 10 Best Essay Collections of the Decade

Ever tried. ever failed. no matter..

Friends, it’s true: the end of the decade approaches. It’s been a difficult, anxiety-provoking, morally compromised decade, but at least it’s been populated by some damn fine literature. We’ll take our silver linings where we can.

So, as is our hallowed duty as a literary and culture website—though with full awareness of the potentially fruitless and endlessly contestable nature of the task—in the coming weeks, we’ll be taking a look at the best and most important (these being not always the same) books of the decade that was. We will do this, of course, by means of a variety of lists. We began with the best debut novels , the best short story collections , the best poetry collections , and the best memoirs of the decade , and we have now reached the fifth list in our series: the best essay collections published in English between 2010 and 2019.

The following books were chosen after much debate (and several rounds of voting) by the Literary Hub staff. Tears were spilled, feelings were hurt, books were re-read. And as you’ll shortly see, we had a hard time choosing just ten—so we’ve also included a list of dissenting opinions, and an even longer list of also-rans. As ever, free to add any of your own favorites that we’ve missed in the comments below.

The Top Ten

Oliver sacks, the mind’s eye (2010).

Toward the end of his life, maybe suspecting or sensing that it was coming to a close, Dr. Oliver Sacks tended to focus his efforts on sweeping intellectual projects like On the Move (a memoir), The River of Consciousness (a hybrid intellectual history), and Hallucinations (a book-length meditation on, what else, hallucinations). But in 2010, he gave us one more classic in the style that first made him famous, a form he revolutionized and brought into the contemporary literary canon: the medical case study as essay. In The Mind’s Eye , Sacks focuses on vision, expanding the notion to embrace not only how we see the world, but also how we map that world onto our brains when our eyes are closed and we’re communing with the deeper recesses of consciousness. Relaying histories of patients and public figures, as well as his own history of ocular cancer (the condition that would eventually spread and contribute to his death), Sacks uses vision as a lens through which to see all of what makes us human, what binds us together, and what keeps us painfully apart. The essays that make up this collection are quintessential Sacks: sensitive, searching, with an expertise that conveys scientific information and experimentation in terms we can not only comprehend, but which also expand how we see life carrying on around us. The case studies of “Stereo Sue,” of the concert pianist Lillian Kalir, and of Howard, the mystery novelist who can no longer read, are highlights of the collection, but each essay is a kind of gem, mined and polished by one of the great storytellers of our era. –Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads Managing Editor

John Jeremiah Sullivan, Pulphead (2011)

The American essay was having a moment at the beginning of the decade, and Pulphead was smack in the middle. Without any hard data, I can tell you that this collection of John Jeremiah Sullivan’s magazine features—published primarily in GQ , but also in The Paris Review , and Harper’s —was the only full book of essays most of my literary friends had read since Slouching Towards Bethlehem , and probably one of the only full books of essays they had even heard of.

Well, we all picked a good one. Every essay in Pulphead is brilliant and entertaining, and illuminates some small corner of the American experience—even if it’s just one house, with Sullivan and an aging writer inside (“Mr. Lytle” is in fact a standout in a collection with no filler; fittingly, it won a National Magazine Award and a Pushcart Prize). But what are they about? Oh, Axl Rose, Christian Rock festivals, living around the filming of One Tree Hill , the Tea Party movement, Michael Jackson, Bunny Wailer, the influence of animals, and by god, the Miz (of Real World/Road Rules Challenge fame).

But as Dan Kois has pointed out , what connects these essays, apart from their general tone and excellence, is “their author’s essential curiosity about the world, his eye for the perfect detail, and his great good humor in revealing both his subjects’ and his own foibles.” They are also extremely well written, drawing much from fictional techniques and sentence craft, their literary pleasures so acute and remarkable that James Wood began his review of the collection in The New Yorker with a quiz: “Are the following sentences the beginnings of essays or of short stories?” (It was not a hard quiz, considering the context.)

It’s hard not to feel, reading this collection, like someone reached into your brain, took out the half-baked stuff you talk about with your friends, researched it, lived it, and represented it to you smarter and better and more thoroughly than you ever could. So read it in awe if you must, but read it. –Emily Temple, Senior Editor

Aleksandar Hemon, The Book of My Lives (2013)

Such is the sentence-level virtuosity of Aleksandar Hemon—the Bosnian-American writer, essayist, and critic—that throughout his career he has frequently been compared to the granddaddy of borrowed language prose stylists: Vladimir Nabokov. While it is, of course, objectively remarkable that anyone could write so beautifully in a language they learned in their twenties, what I admire most about Hemon’s work is the way in which he infuses every essay and story and novel with both a deep humanity and a controlled (but never subdued) fury. He can also be damn funny. Hemon grew up in Sarajevo and left in 1992 to study in Chicago, where he almost immediately found himself stranded, forced to watch from afar as his beloved home city was subjected to a relentless four-year bombardment, the longest siege of a capital in the history of modern warfare. This extraordinary memoir-in-essays is many things: it’s a love letter to both the family that raised him and the family he built in exile; it’s a rich, joyous, and complex portrait of a place the 90s made synonymous with war and devastation; and it’s an elegy for the wrenching loss of precious things. There’s an essay about coming of age in Sarajevo and another about why he can’t bring himself to leave Chicago. There are stories about relationships forged and maintained on the soccer pitch or over the chessboard, and stories about neighbors and mentors turned monstrous by ethnic prejudice. As a chorus they sing with insight, wry humor, and unimaginable sorrow. I am not exaggerating when I say that the collection’s devastating final piece, “The Aquarium”—which details his infant daughter’s brain tumor and the agonizing months which led up to her death—remains the most painful essay I have ever read. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (2013)

Of every essay in my relentlessly earmarked copy of Braiding Sweetgrass , Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer’s gorgeously rendered argument for why and how we should keep going, there’s one that especially hits home: her account of professor-turned-forester Franz Dolp. When Dolp, several decades ago, revisited the farm that he had once shared with his ex-wife, he found a scene of destruction: The farm’s new owners had razed the land where he had tried to build a life. “I sat among the stumps and the swirling red dust and I cried,” he wrote in his journal.

So many in my generation (and younger) feel this kind of helplessness–and considerable rage–at finding ourselves newly adult in a world where those in power seem determined to abandon or destroy everything that human bodies have always needed to survive: air, water, land. Asking any single book to speak to this helplessness feels unfair, somehow; yet, Braiding Sweetgrass does, by weaving descriptions of indigenous tradition with the environmental sciences in order to show what survival has looked like over the course of many millennia. Kimmerer’s essays describe her personal experience as a Potawotami woman, plant ecologist, and teacher alongside stories of the many ways that humans have lived in relationship to other species. Whether describing Dolp’s work–he left the stumps for a life of forest restoration on the Oregon coast–or the work of others in maple sugar harvesting, creating black ash baskets, or planting a Three Sisters garden of corn, beans, and squash, she brings hope. “In ripe ears and swelling fruit, they counsel us that all gifts are multiplied in relationship,” she writes of the Three Sisters, which all sustain one another as they grow. “This is how the world keeps going.” –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Hilton Als, White Girls (2013)

In a world where we are so often reduced to one essential self, Hilton Als’ breathtaking book of critical essays, White Girls , which meditates on the ways he and other subjects read, project and absorb parts of white femininity, is a radically liberating book. It’s one of the only works of critical thinking that doesn’t ask the reader, its author or anyone he writes about to stoop before the doorframe of complete legibility before entering. Something he also permitted the subjects and readers of his first book, the glorious book-length essay, The Women , a series of riffs and psychological portraits of Dorothy Dean, Owen Dodson, and the author’s own mother, among others. One of the shifts of that book, uncommon at the time, was how it acknowledges the way we inhabit bodies made up of variously gendered influences. To read White Girls now is to experience the utter freedom of this gift and to marvel at Als’ tremendous versatility and intelligence.

He is easily the most diversely talented American critic alive. He can write into genres like pop music and film where being part of an audience is a fantasy happening in the dark. He’s also wired enough to know how the art world builds reputations on the nod of rich white patrons, a significant collision in a time when Jean-Michel Basquiat is America’s most expensive modern artist. Als’ swerving and always moving grip on performance means he’s especially good on describing the effect of art which is volatile and unstable and built on the mingling of made-up concepts and the hard fact of their effect on behavior, such as race. Writing on Flannery O’Connor for instance he alone puts a finger on her “uneasy and unavoidable union between black and white, the sacred and the profane, the shit and the stars.” From Eminem to Richard Pryor, André Leon Talley to Michael Jackson, Als enters the life and work of numerous artists here who turn the fascinations of race and with whiteness into fury and song and describes the complexity of their beauty like his life depended upon it. There are also brief memoirs here that will stop your heart. This is an essential work to understanding American culture. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

Eula Biss, On Immunity (2014)

We move through the world as if we can protect ourselves from its myriad dangers, exercising what little agency we have in an effort to keep at bay those fears that gather at the edges of any given life: of loss, illness, disaster, death. It is these fears—amplified by the birth of her first child—that Eula Biss confronts in her essential 2014 essay collection, On Immunity . As any great essayist does, Biss moves outward in concentric circles from her own very private view of the world to reveal wider truths, discovering as she does a culture consumed by anxiety at the pervasive toxicity of contemporary life. As Biss interrogates this culture—of privilege, of whiteness—she interrogates herself, questioning the flimsy ways in which we arm ourselves with science or superstition against the impurities of daily existence.

Five years on from its publication, it is dismaying that On Immunity feels as urgent (and necessary) a defense of basic science as ever. Vaccination, we learn, is derived from vacca —for cow—after the 17th-century discovery that a small application of cowpox was often enough to inoculate against the scourge of smallpox, an etymological digression that belies modern conspiratorial fears of Big Pharma and its vaccination agenda. But Biss never scolds or belittles the fears of others, and in her generosity and openness pulls off a neat (and important) trick: insofar as we are of the very world we fear, she seems to be suggesting, we ourselves are impure, have always been so, permeable, vulnerable, yet so much stronger than we think. –Jonny Diamond, Editor-in-Chief

Rebecca Solnit, The Mother of All Questions (2016)

When Rebecca Solnit’s essay, “Men Explain Things to Me,” was published in 2008, it quickly became a cultural phenomenon unlike almost any other in recent memory, assigning language to a behavior that almost every woman has witnessed—mansplaining—and, in the course of identifying that behavior, spurring a movement, online and offline, to share the ways in which patriarchal arrogance has intersected all our lives. (It would also come to be the titular essay in her collection published in 2014.) The Mother of All Questions follows up on that work and takes it further in order to examine the nature of self-expression—who is afforded it and denied it, what institutions have been put in place to limit it, and what happens when it is employed by women. Solnit has a singular gift for describing and decoding the misogynistic dynamics that govern the world so universally that they can seem invisible and the gendered violence that is so common as to seem unremarkable; this naming is powerful, and it opens space for sharing the stories that shape our lives.

The Mother of All Questions, comprised of essays written between 2014 and 2016, in many ways armed us with some of the tools necessary to survive the gaslighting of the Trump years, in which many of us—and especially women—have continued to hear from those in power that the things we see and hear do not exist and never existed. Solnit also acknowledges that labels like “woman,” and other gendered labels, are identities that are fluid in reality; in reviewing the book for The New Yorker , Moira Donegan suggested that, “One useful working definition of a woman might be ‘someone who experiences misogyny.'” Whichever words we use, Solnit writes in the introduction to the book that “when words break through unspeakability, what was tolerated by a society sometimes becomes intolerable.” This storytelling work has always been vital; it continues to be vital, and in this book, it is brilliantly done. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Valeria Luiselli, Tell Me How It Ends (2017)

The newly minted MacArthur fellow Valeria Luiselli’s four-part (but really six-part) essay Tell Me How It Ends: An Essay in Forty Questions was inspired by her time spent volunteering at the federal immigration court in New York City, working as an interpreter for undocumented, unaccompanied migrant children who crossed the U.S.-Mexico border. Written concurrently with her novel Lost Children Archive (a fictional exploration of the same topic), Luiselli’s essay offers a fascinating conceit, the fashioning of an argument from the questions on the government intake form given to these children to process their arrivals. (Aside from the fact that this essay is a heartbreaking masterpiece, this is such a good conceit—transforming a cold, reproducible administrative document into highly personal literature.) Luiselli interweaves a grounded discussion of the questionnaire with a narrative of the road trip Luiselli takes with her husband and family, across America, while they (both Mexican citizens) wait for their own Green Card applications to be processed. It is on this trip when Luiselli reflects on the thousands of migrant children mysteriously traveling across the border by themselves. But the real point of the essay is to actually delve into the real stories of some of these children, which are agonizing, as well as to gravely, clearly expose what literally happens, procedural, when they do arrive—from forms to courts, as they’re swallowed by a bureaucratic vortex. Amid all of this, Luiselli also takes on more, exploring the larger contextual relationship between the United States of America and Mexico (as well as other countries in Central America, more broadly) as it has evolved to our current, adverse moment. Tell Me How It Ends is so small, but it is so passionate and vigorous: it desperately accomplishes in its less-than-100-pages-of-prose what centuries and miles and endless records of federal bureaucracy have never been able, and have never cared, to do: reverse the dehumanization of Latin American immigrants that occurs once they set foot in this country. –Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Editorial Fellow

Zadie Smith, Feel Free (2018)

In the essay “Meet Justin Bieber!” in Feel Free , Zadie Smith writes that her interest in Justin Bieber is not an interest in the interiority of the singer himself, but in “the idea of the love object”. This essay—in which Smith imagines a meeting between Bieber and the late philosopher Martin Buber (“Bieber and Buber are alternative spellings of the same German surname,” she explains in one of many winning footnotes. “Who am I to ignore these hints from the universe?”). Smith allows that this premise is a bit premise -y: “I know, I know.” Still, the resulting essay is a very funny, very smart, and un-tricky exploration of individuality and true “meeting,” with a dash of late capitalism thrown in for good measure. The melding of high and low culture is the bread and butter of pretty much every prestige publication on the internet these days (and certainly of the Twitter feeds of all “public intellectuals”), but the essays in Smith’s collection don’t feel familiar—perhaps because hers is, as we’ve long known, an uncommon skill. Though I believe Smith could probably write compellingly about anything, she chooses her subjects wisely. She writes with as much electricity about Brexit as the aforementioned Beliebers—and each essay is utterly engrossing. “She contains multitudes, but her point is we all do,” writes Hermione Hoby in her review of the collection in The New Republic . “At the same time, we are, in our endless difference, nobody but ourselves.” –Jessie Gaynor, Social Media Editor

Tressie McMillan Cottom, Thick: And Other Essays (2019)

Tressie McMillan Cottom is an academic who has transcended the ivory tower to become the sort of public intellectual who can easily appear on radio or television talk shows to discuss race, gender, and capitalism. Her collection of essays reflects this duality, blending scholarly work with memoir to create a collection on the black female experience in postmodern America that’s “intersectional analysis with a side of pop culture.” The essays range from an analysis of sexual violence, to populist politics, to social media, but in centering her own experiences throughout, the collection becomes something unlike other pieces of criticism of contemporary culture. In explaining the title, she reflects on what an editor had said about her work: “I was too readable to be academic, too deep to be popular, too country black to be literary, and too naïve to show the rigor of my thinking in the complexity of my prose. I had wanted to create something meaningful that sounded not only like me, but like all of me. It was too thick.” One of the most powerful essays in the book is “Dying to be Competent” which begins with her unpacking the idiocy of LinkedIn (and the myth of meritocracy) and ends with a description of her miscarriage, the mishandling of black woman’s pain, and a condemnation of healthcare bureaucracy. A finalist for the 2019 National Book Award for Nonfiction, Thick confirms McMillan Cottom as one of our most fearless public intellectuals and one of the most vital. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Dissenting Opinions

The following books were just barely nudged out of the top ten, but we (or at least one of us) couldn’t let them pass without comment.

Elif Batuman, The Possessed (2010)

In The Possessed Elif Batuman indulges her love of Russian literature and the result is hilarious and remarkable. Each essay of the collection chronicles some adventure or other that she had while in graduate school for Comparative Literature and each is more unpredictable than the next. There’s the time a “well-known 20th-centuryist” gave a graduate student the finger; and the time when Batuman ended up living in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, for a summer; and the time that she convinced herself Tolstoy was murdered and spent the length of the Tolstoy Conference in Yasnaya Polyana considering clues and motives. Rich in historic detail about Russian authors and literature and thoughtfully constructed, each essay is an amalgam of critical analysis, cultural criticism, and serious contemplation of big ideas like that of identity, intellectual legacy, and authorship. With wit and a serpentine-like shape to her narratives, Batuman adopts a form reminiscent of a Socratic discourse, setting up questions at the beginning of her essays and then following digressions that more or less entreat the reader to synthesize the answer for herself. The digressions are always amusing and arguably the backbone of the collection, relaying absurd anecdotes with foreign scholars or awkward, surreal encounters with Eastern European strangers. Central also to the collection are Batuman’s intellectual asides where she entertains a theory—like the “problem of the person”: the inability to ever wholly capture one’s character—that ultimately layer the book’s themes. “You are certainly my most entertaining student,” a professor said to Batuman. But she is also curious and enthusiastic and reflective and so knowledgeable that she might even convince you (she has me!) that you too love Russian literature as much as she does. –Eleni Theodoropoulos, Editorial Fellow

Roxane Gay, Bad Feminist (2014)

Roxane Gay’s now-classic essay collection is a book that will make you laugh, think, cry, and then wonder, how can cultural criticism be this fun? My favorite essays in the book include Gay’s musings on competitive Scrabble, her stranded-in-academia dispatches, and her joyous film and television criticism, but given the breadth of topics Roxane Gay can discuss in an entertaining manner, there’s something for everyone in this one. This book is accessible because feminism itself should be accessible – Roxane Gay is as likely to draw inspiration from YA novels, or middle-brow shows about friendship, as she is to introduce concepts from the academic world, and if there’s anyone I trust to bridge the gap between high culture, low culture, and pop culture, it’s the Goddess of Twitter. I used to host a book club dedicated to radical reads, and this was one of the first picks for the club; a week after the book club met, I spied a few of the attendees meeting in the café of the bookstore, and found out that they had bonded so much over discussing Bad Feminist that they couldn’t wait for the next meeting of the book club to keep discussing politics and intersectionality, and that, in a nutshell, is the power of Roxane. –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Associate Editor

Rivka Galchen, Little Labors (2016)

Generally, I find stories about the trials and tribulations of child-having to be of limited appeal—useful, maybe, insofar as they offer validation that other people have also endured the bizarre realities of living with a tiny human, but otherwise liable to drift into the musings of parents thrilled at the simple fact of their own fecundity, as if they were the first ones to figure the process out (or not). But Little Labors is not simply an essay collection about motherhood, perhaps because Galchen initially “didn’t want to write about” her new baby—mostly, she writes, “because I had never been interested in babies, or mothers; in fact, those subjects had seemed perfectly not interesting to me.” Like many new mothers, though, Galchen soon discovered her baby—which she refers to sometimes as “the puma”—to be a preoccupying thought, demanding to be written about. Galchen’s interest isn’t just in her own progeny, but in babies in literature (“Literature has more dogs than babies, and also more abortions”), The Pillow Book , the eleventh-century collection of musings by Sei Shōnagon, and writers who are mothers. There are sections that made me laugh out loud, like when Galchen continually finds herself in an elevator with a neighbor who never fails to remark on the puma’s size. There are also deeper, darker musings, like the realization that the baby means “that it’s not permissible to die. There are days when this does not feel good.” It is a slim collection that I happened to read at the perfect time, and it remains one of my favorites of the decade. –Emily Firetog, Deputy Editor

Charlie Fox, This Young Monster (2017)

On social media as in his writing, British art critic Charlie Fox rejects lucidity for allusion and doesn’t quite answer the Twitter textbox’s persistent question: “What’s happening?” These days, it’s hard to tell. This Young Monster (2017), Fox’s first book,was published a few months after Donald Trump’s election, and at one point Fox takes a swipe at a man he judges “direct from a nightmare and just a repulsive fucking goon.” Fox doesn’t linger on politics, though, since most of the monsters he looks at “embody otherness and make it into art, ripping any conventional idea of beauty to shreds and replacing it with something weird and troubling of their own invention.”

If clichés are loathed because they conform to what philosopher Georges Bataille called “the common measure,” then monsters are rebellious non-sequiturs, comedic or horrific derailments from a classical ideal. Perverts in the most literal sense, monsters have gone astray from some “proper” course. The book’s nine chapters, which are about a specific monster or type of monster, are full of callbacks to familiar and lesser-known media. Fox cites visual art, film, songs, and books with the screwy buoyancy of a savant. Take one of his essays, “Spook House,” framed as a stage play with two principal characters, Klaus (“an intoxicated young skinhead vampire”) and Hermione (“a teen sorceress with green skin and jet-black hair” who looks more like The Wicked Witch than her namesake). The chorus is a troupe of trick-or-treaters. Using the filmmaker Cameron Jamie as a starting point, the rest is free association on gothic decadence and Detroit and L.A. as cities of the dead. All the while, Klaus quotes from Artforum , Dazed & Confused , and Time Out. It’s a technical feat that makes fictionalized dialogue a conveyor belt for cultural criticism.

In Fox’s imagination, David Bowie and the Hydra coexist alongside Peter Pan, Dennis Hopper, and the maenads. Fox’s book reaches for the monster’s mask, not really to peel it off but to feel and smell the rubber schnoz, to know how it’s made before making sure it’s still snugly set. With a stylistic blend of arthouse suavity and B-movie chic, This Young Monster considers how monsters in culture are made. Aren’t the scariest things made in post-production? Isn’t the creature just duplicity, like a looping choir or a dubbed scream? –Aaron Robertson, Assistant Editor

Elena Passarello, Animals Strike Curious Poses (2017)

Elena Passarello’s collection of essays Animals Strike Curious Poses picks out infamous animals and grants them the voice, narrative, and history they deserve. Not only is a collection like this relevant during the sixth extinction but it is an ambitious historical and anthropological undertaking, which Passarello has tackled with thorough research and a playful tone that rather than compromise her subject, complicates and humanizes it. Passarello’s intention is to investigate the role of animals across the span of human civilization and in doing so, to construct a timeline of humanity as told through people’s interactions with said animals. “Of all the images that make our world, animal images are particularly buried inside us,” Passarello writes in her first essay, to introduce us to the object of the book and also to the oldest of her chosen characters: Yuka, a 39,000-year-old mummified woolly mammoth discovered in the Siberian permafrost in 2010. It was an occasion so remarkable and so unfathomable given the span of human civilization that Passarello says of Yuka: “Since language is epically younger than both thought and experience, ‘woolly mammoth’ means, to a human brain, something more like time.” The essay ends with a character placing a hand on a cave drawing of a woolly mammoth, accompanied by a phrase which encapsulates the author’s vision for the book: “And he becomes the mammoth so he can envision the mammoth.” In Passarello’s hands the imagined boundaries between the animal, natural, and human world disintegrate and what emerges is a cohesive if baffling integrated history of life. With the accuracy and tenacity of a journalist and the spirit of a storyteller, Elena Passarello has assembled a modern bestiary worthy of contemplation and awe. –Eleni Theodoropoulos, Editorial Fellow

Esmé Weijun Wang, The Collected Schizophrenias (2019)

Esmé Weijun Wang’s collection of essays is a kaleidoscopic look at mental health and the lives affected by the schizophrenias. Each essay takes on a different aspect of the topic, but you’ll want to read them together for a holistic perspective. Esmé Weijun Wang generously begins The Collected Schizophrenias by acknowledging the stereotype, “Schizophrenia terrifies. It is the archetypal disorder of lunacy.” From there, she walks us through the technical language, breaks down the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual ( DSM-5 )’s clinical definition. And then she gets very personal, telling us about how she came to her own diagnosis and the way it’s touched her daily life (her relationships, her ideas about motherhood). Esmé Weijun Wang is uniquely situated to write about this topic. As a former lab researcher at Stanford, she turns a precise, analytical eye to her experience while simultaneously unfolding everything with great patience for her reader. Throughout, she brilliantly dissects the language around mental health. (On saying “a person living with bipolar disorder” instead of using “bipolar” as the sole subject: “…we are not our diseases. We are instead individuals with disorders and malfunctions. Our conditions lie over us like smallpox blankets; we are one thing and the illness is another.”) She pinpoints the ways she arms herself against anticipated reactions to the schizophrenias: high fashion, having attended an Ivy League institution. In a particularly piercing essay, she traces mental illness back through her family tree. She also places her story within more mainstream cultural contexts, calling on groundbreaking exposés about the dangerous of institutionalization and depictions of mental illness in television and film (like the infamous Slender Man case, in which two young girls stab their best friend because an invented Internet figure told them to). At once intimate and far-reaching, The Collected Schizophrenias is an informative and important (and let’s not forget artful) work. I’ve never read a collection quite so beautifully-written and laid-bare as this. –Katie Yee, Book Marks Assistant Editor

Ross Gay, The Book of Delights (2019)

When Ross Gay began writing what would become The Book of Delights, he envisioned it as a project of daily essays, each focused on a moment or point of delight in his day. This plan quickly disintegrated; on day four, he skipped his self-imposed assignment and decided to “in honor and love, delight in blowing it off.” (Clearly, “blowing it off” is a relative term here, as he still produced the book.) Ross Gay is a generous teacher of how to live, and this moment of reveling in self-compassion is one lesson among many in The Book of Delights , which wanders from moments of connection with strangers to a shade of “red I don’t think I actually have words for,” a text from a friend reading “I love you breadfruit,” and “the sun like a guiding hand on my back, saying everything is possible. Everything .”

Gay does not linger on any one subject for long, creating the sense that delight is a product not of extenuating circumstances, but of our attention; his attunement to the possibilities of a single day, and awareness of all the small moments that produce delight, are a model for life amid the warring factions of the attention economy. These small moments range from the physical–hugging a stranger, transplanting fig cuttings–to the spiritual and philosophical, giving the impression of sitting beside Gay in his garden as he thinks out loud in real time. It’s a privilege to listen. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

Honorable Mentions

A selection of other books that we seriously considered for both lists—just to be extra about it (and because decisions are hard).

Terry Castle, The Professor and Other Writings (2010) · Joyce Carol Oates, In Rough Country (2010) · Geoff Dyer, Otherwise Known as the Human Condition (2011) · Christopher Hitchens, Arguably (2011) · Roberto Bolaño, tr. Natasha Wimmer, Between Parentheses (2011) · Dubravka Ugresic, tr. David Williams, Karaoke Culture (2011) · Tom Bissell, Magic Hours (2012) · Kevin Young, The Grey Album (2012) · William H. Gass, Life Sentences: Literary Judgments and Accounts (2012) · Mary Ruefle, Madness, Rack, and Honey (2012) · Herta Müller, tr. Geoffrey Mulligan, Cristina and Her Double (2013) · Leslie Jamison, The Empathy Exams (2014) · Meghan Daum, The Unspeakable (2014) · Daphne Merkin, The Fame Lunches (2014) · Charles D’Ambrosio, Loitering (2015) · Wendy Walters, Multiply/Divide (2015) · Colm Tóibín, On Elizabeth Bishop (2015) · Renee Gladman, Calamities (2016) · Jesmyn Ward, ed. The Fire This Time (2016) · Lindy West, Shrill (2016) · Mary Oliver, Upstream (2016) · Emily Witt, Future Sex (2016) · Olivia Laing, The Lonely City (2016) · Mark Greif, Against Everything (2016) · Durga Chew-Bose, Too Much and Not the Mood (2017) · Sarah Gerard, Sunshine State (2017) · Jim Harrison, A Really Big Lunch (2017) · J.M. Coetzee, Late Essays: 2006-2017 (2017) · Melissa Febos, Abandon Me (2017) · Louise Glück, American Originality (2017) · Joan Didion, South and West (2017) · Tom McCarthy, Typewriters, Bombs, Jellyfish (2017) · Hanif Abdurraqib, They Can’t Kill Us Until they Kill Us (2017) · Ta-Nehisi Coates, We Were Eight Years in Power (2017) · Samantha Irby, We Are Never Meeting in Real Life (2017) · Alexander Chee, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel (2018) · Alice Bolin, Dead Girls (2018) · Marilynne Robinson, What Are We Doing Here? (2018) · Lorrie Moore, See What Can Be Done (2018) · Maggie O’Farrell, I Am I Am I Am (2018) · Ijeoma Oluo, So You Want to Talk About Race (2018) · Rachel Cusk, Coventry (2019) · Jia Tolentino, Trick Mirror (2019) · Emily Bernard, Black is the Body (2019) · Toni Morrison, The Source of Self-Regard (2019) · Margaret Renkl, Late Migrations (2019) · Rachel Munroe, Savage Appetites (2019) · Robert A. Caro, Working (2019) · Arundhati Roy, My Seditious Heart (2019).

Emily Temple

Previous article, next article.

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

- NONFICTION BOOKS

- BEST NONFICTION 2023

- BEST NONFICTION 2024

- Historical Biographies

- The Best Memoirs and Autobiographies

- Philosophical Biographies

- World War 2

- World History

- American History

- British History

- Chinese History

- Russian History

- Ancient History (up to 500)

- Medieval History (500-1400)

- Military History

- Art History

- Travel Books

- Ancient Philosophy

- Contemporary Philosophy

- Ethics & Moral Philosophy

- Great Philosophers

- Social & Political Philosophy

- Classical Studies

- New Science Books

- Maths & Statistics

- Popular Science

- Physics Books

- Climate Change Books

- How to Write

- English Grammar & Usage

- Books for Learning Languages

- Linguistics

- Political Ideologies

- Foreign Policy & International Relations

- American Politics

- British Politics

- Religious History Books

- Mental Health

- Neuroscience

- Child Psychology

- Film & Cinema

- Opera & Classical Music

- Behavioural Economics

- Development Economics

- Economic History

- Financial Crisis

- World Economies

- How to Invest

- Artificial Intelligence/AI Books

- Data Science Books

- Sex & Sexuality

- Death & Dying

- Food & Cooking

- Sports, Games & Hobbies

- FICTION BOOKS

- BEST FICTION 2023

- NEW Fiction

- World Literature

- Literary Criticism

- Literary Figures

- Classic English Literature

- American Literature

- Comics & Graphic Novels

- Fairy Tales & Mythology

- Historical Fiction

- Crime Novels

- Science Fiction

- Short Stories

- South Africa

- United States

- Arctic & Antarctica

- Afghanistan

- Myanmar (Formerly Burma)

- Netherlands

- Kids Recommend Books for Kids

- High School Teachers Recommendations

- Prizewinning Kids' Books

- Popular Series Books for Kids

- BEST BOOKS FOR KIDS (ALL AGES)

- Ages Baby-2

- Books for Teens and Young Adults

- THE BEST SCIENCE BOOKS FOR KIDS

- BEST KIDS' BOOKS OF 2023

- BEST BOOKS FOR TEENS OF 2023

- Best Audiobooks for Kids

- Environment

- Best Books for Teens of 2023

- Best Kids' Books of 2023

- Political Novels

- New History Books

- New Literary Fiction

- New Historical Fiction

- New Biography

- New Memoirs

- New World Literature

- New Economics Books

- New Climate Books

- New Math Books

- New Philosophy Books

- New Psychology Books

- New Physics Books

- THE BEST AUDIOBOOKS

- Actors Read Great Books

- Books Narrated by Their Authors

- Best Audiobook Thrillers

- Best History Audiobooks

- Nobel Literature Prize

- Booker Prize (fiction)

- Baillie Gifford Prize (nonfiction)

- Financial Times (nonfiction)

- Wolfson Prize (history)

- Royal Society (science)

- Pushkin House Prize (Russia)

- Walter Scott Prize (historical fiction)

- Arthur C Clarke Prize (sci fi)

- The Hugos (sci fi & fantasy)

- Audie Awards (audiobooks)

Make Your Own List

Nonfiction Books » Essays

The best essays: the 2021 pen/diamonstein-spielvogel award, recommended by adam gopnik.

WINNER OF the 2021 PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay

Had I Known: Collected Essays by Barbara Ehrenreich

Every year, the judges of the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay search out the best book of essays written in the past year and draw attention to the author's entire body of work. Here, Adam Gopnik , writer, journalist and PEN essay prize judge, emphasizes the role of the essay in bearing witness and explains why the five collections that reached the 2021 shortlist are, in their different ways, so important.

Interview by Benedict King

Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Re-Reader by Vivian Gornick

Nature Matrix: New and Selected Essays by Robert Michael Pyle

Terroir: Love, Out of Place by Natasha Sajé

Maybe the People Would be the Times by Luc Sante

1 Had I Known: Collected Essays by Barbara Ehrenreich

2 unfinished business: notes of a chronic re-reader by vivian gornick, 3 nature matrix: new and selected essays by robert michael pyle, 4 terroir: love, out of place by natasha sajé, 5 maybe the people would be the times by luc sante.

W e’re talking about the books shortlisted for the 2021 PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award for the Art of the Essay . As an essayist yourself, or as a reader of essays, what are you looking for? What’s the key to a good essay ?

I have very specific and, in some ways, old fashioned views on the essay—though I think that the books we chose tend to confirm the ‘relevance’, perhaps even the continuing urgency, of those views. I think that we always ought to distinguish the essay from a political editorial or polemic on the one hand, and from a straight memoir or confession on the other. The essay, for me, is always a form in which it’s significant—more than significant, it’s decisive—that it has some form of first-person address, a particular voice bearing witness at a particular time. An essay isn’t a common claim, it’s not an editorial ‘we’, it’s not a manifesto. It’s one writer, one voice, addressing readers as though face-to-face. At the same time, for me—and I think this sense was shared by the other judges, as an intuition about the essay—it isn’t simply What Happened to Me. It’s not an autobiographical memoir, or a piece taken from an autobiographical memoir, wonderful though those can be (I say, as one who writes those, too).

Let’s turn to the books that made the shortlist of the 2021 PEN Award for the Art of the Essay. The winning book was Had I Known: Collected Essays by Barbara Ehrenreich , whose books have been recommended a number of times on Five Books. Tell me more.

One of the criteria for this particular prize is that it should be not just for a single book, but for a body of work. One of the things we wanted to honour about Barbara Ehrenreich is that she has produced a remarkable body of work. Although it’s offered in a more specifically political register than some essayists, or that a great many past prize winners have practised, the quiddity of her work is that it remains rooted in personal experience, in the act of bearing witness. She has a passionate political point to make, certainly, a series of them, many seeming all the more relevant now than when she began writing. Nonetheless, her writing still always depends on the intimacy of first-hand knowledge, what people in post-incarceration work call ‘lived experience’ (a term with a distinguished philosophical history). Her book Nickel and Dimed is the classic example of that. She never writes from a distance about working-class life in America. She bears witness to the nature and real texture of working-class life in America.

“One point of giving awards…is to keep passing the small torches of literary tradition”

Next up of the books on the 2021 PEN essay prize shortlist is Unfinished Business: Notes of a Chronic Re-Reader by Vivian Gornick.

Vivian Gornick is a writer who’s been around for a very long time. Although longevity is not in itself a criterion for excellence—or for this prize, or in the writing life generally—persistence and perseverance are. Writers who keep coming back at us, again and again, with a consistent vision, are surely to be saluted. For her admirers, her appetite to re-read things already read is one of the most attractive parts of her oeuvre , if I can call it that; her appetite not just to read but to read deeply and personally. One of the things that people who love her work love about it is that her readings are never academic, or touched by scholarly hobbyhorsing. They’re readings that involve the fullness of her experience, then applied to literature. Although she reads as a critic, she reads as an essayist reads, rather than as a reviewer reads. And I think that was one of the things that was there to honour in her body of work, as well.

Is she a novelist or journalist, as well?

Let’s move on to the next book which made the 2021 PEN essay shortlist. This is Nature Matrix: New and Selected Essays by Robert Michael Pyle.

I have a special reason for liking this book in particular, and that is that it corresponds to one of the richest and oldest of American genres, now often overlooked, and that’s the naturalist essay. You can track it back to Henry David Thoreau , if not to Ralph Waldo Emerson , this American engagement with nature , the wilderness, not from a narrowly scientific point of view, nor from a purely ecological or environmental point of view—though those things are part of it—but again, from the point of view of lived experience, of personal testimony.

Let’s look at the next book on the shortlist of the 2021 PEN Awards, which is Terroir: Love, Out of Place by Natasha Sajé. Why did these essays appeal?

One of the things that was appealing about this book is that’s it very much about, in every sense, the issues of the day: the idea of place, of where we are, how we are located on any map as individuals by ethnic identity, class, gender—all of those things. But rather than being carried forward in a narrowly argumentative way, again, in the classic manner of the essay, Sajé’s work is ruminative. It walks around these issues from the point of view of someone who’s an expatriate, someone who’s an émigré, someone who’s a world citizen, but who’s also concerned with the idea of ‘terroir’, the one place in the world where we belong. And I think the dialogue in her work between a kind of cosmopolitanism that she has along with her self-critical examination of the problem of localism and where we sit on the world, was inspiring to us.

Get the weekly Five Books newsletter

Last of the books on the shortlist for the 2021 Pen essay award is Maybe the People Would Be the Times by Luc Sante.

Again, here’s a writer who’s had a distinguished generalised career, writing about lots of places and about lots of subjects. In the past, he’s made his special preoccupation what he calls ‘low life’, but I think more broadly can be called the marginalized or the repressed and abject. He’s also written acute introductions to the literature of ‘low life’, the works of Asbury and David Maurer, for instance.

But I think one of the things that was appealing about what he’s done is the sheer range of his enterprise. He writes about countless subjects. He can write about A-sides and B-sides of popular records—singles—then go on to write about Jacques Rivette’s cinema. He writes from a kind of private inspection of public experience. He has a lovely piece about tabloid headlines and their evolution. And I think that omnivorous range of enthusiasms and passions is a stirring reminder in a time of specialization and compartmentalization of the essayist’s freedom to roam. If Pyle is in the tradition of Thoreau, I suspect Luc Sante would be proud to be put in the tradition of Baudelaire—the flaneur who walks the streets, sees everything, broods on it all and writes about it well.

One point of giving awards, with all their built-in absurdity and inevitable injustice, is to keep alive, or at least to keep passing, the small torches of literary tradition. And just as much as we’re honoring the great tradition of the naturalist essay in the one case, I think we’re honoring the tradition of the Baudelairean flaneur in this one.

April 18, 2021

Five Books aims to keep its book recommendations and interviews up to date. If you are the interviewee and would like to update your choice of books (or even just what you say about them) please email us at [email protected]

Support Five Books

Five Books interviews are expensive to produce. If you've enjoyed this interview, please support us by donating a small amount .

©Brigitte Lacombe

Adam Gopnik

Adam Gopnik has been a staff writer at the New Yorker since 1986. His many books include A Thousand Small Sanities: The Moral Adventure of Liberalism . He is a three time winner of the National Magazine Award for Essays & Criticism, and in 2021 was made a chevalier of the Legion d'Honneur by the French Republic.

We ask experts to recommend the five best books in their subject and explain their selection in an interview.

This site has an archive of more than one thousand seven hundred interviews, or eight thousand book recommendations. We publish at least two new interviews per week.

Five Books participates in the Amazon Associate program and earns money from qualifying purchases.

© Five Books 2024

- Literature & Fiction

- History & Criticism

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: $13.39 $13.39 FREE delivery: Thursday, March 28 on orders over $35.00 shipped by Amazon. Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Buy used: $9.09

Fulfillment by Amazon (FBA) is a service we offer sellers that lets them store their products in Amazon's fulfillment centers, and we directly pack, ship, and provide customer service for these products. Something we hope you'll especially enjoy: FBA items qualify for FREE Shipping and Amazon Prime.

If you're a seller, Fulfillment by Amazon can help you grow your business. Learn more about the program.

Other Sellers on Amazon

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

The Art of the Personal Essay: An Anthology from the Classical Era to the Present Paperback – January 15, 1995

Purchase options and add-ons.

- Reading age 1 year and up

- Print length 777 pages

- Language English

- Lexile measure 1180L

- Dimensions 6.04 x 1.63 x 9.16 inches

- Publisher Anchor

- Publication date January 15, 1995

- ISBN-10 038542339X

- ISBN-13 978-0385423397

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may ship from close to you

Editorial Reviews

From the publisher.

"Packed with personality and beguiling first-person prose... of reminders of the perils and pleasures of the craft." -- The Wall Street Journal .

From the Inside Flap

From the back cover, about the author, excerpt. © reprinted by permission. all rights reserved., product details.

- Publisher : Anchor; First Edition (January 15, 1995)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 777 pages

- ISBN-10 : 038542339X

- ISBN-13 : 978-0385423397

- Reading age : 1 year and up

- Lexile measure : 1180L

- Item Weight : 2.3 pounds

- Dimensions : 6.04 x 1.63 x 9.16 inches

- #24 in Comparative Literature

- #425 in Essays (Books)

- #1,567 in Short Stories Anthologies

About the author

Phillip lopate.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

Reviews with images

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Start Selling with Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

The Cowardice of Guernica

The literary magazine Guernica ’s decision to retract an essay about the Israeli-Palestinian conflict reveals much about how the war is hardening human sentiment.

Listen to this article

Produced by ElevenLabs and News Over Audio (NOA) using AI narration.

In the days after October 7, the writer and translator Joanna Chen spoke with a neighbor in Israel whose children were frightened by the constant sound of warplanes. “I tell them these are good booms,” the neighbor said to Chen with a grimace. “I understood the subtext,” Chen wrote later in an essay published in Guernica magazine on March 4, titled “From the Edges of a Broken World.” The booms were, of course, the Israeli army bombing Gaza, part of a campaign that has left at least 30,000 civilians and combatants dead so far.

The moment is just one observation in a much longer meditative piece of writing in which Chen weighs her principles—for years she has volunteered at a charity providing transportation for Palestinian children needing medical care, and works on Arabic and Hebrew translations to bridge cultural divides—against the more turbulent feelings of fear, inadequacy, and split allegiances that have cropped up for her after October 7, when 1,200 people were killed and 250 taken hostage in Hamas’s assault on Israel. But the conversation with the neighbor is a sharp, novelistic, and telling moment. The mother, aware of the perversity of recasting bombs killing children mere miles away as “good booms,” does so anyway because she is a mother, and her children are frightened. The act, at once callous and caring, will stay with me.

Not with the readers of Guernica , though. The magazine , once a prominent publication for fiction, poetry, and literary nonfiction, with a focus on global art and politics, quickly found itself imploding as its all-volunteer staff revolted over the essay. One of the magazine’s nonfiction editors posted on social media that she was leaving over Chen’s publication. “Parts of the essay felt particularly harmful and disorienting to read, such as the line where a person is quoted saying ‘I tell them these are good booms.’” Soon a poetry editor resigned as well, calling Chen’s essay a “horrific settler normalization essay”— settler here seeming to refer to all Israelis, because Chen does not live in the occupied territories. More staff members followed, including the senior nonfiction editor and one of the co-publishers (who criticized the essay as “a hand-wringing apologia for Zionism”). Amid this flurry of cascading outrage, on March 10 Guernica pulled the essay from its website, with the note: “ Guernica regrets having published this piece, and has retracted it. A more fulsome explanation will follow.” As of today, this explanation is still pending, and my request for comment from the editor in chief, Jina Moore Ngarambe, has gone unanswered.

Read: Beware the language that erases reality

Blowups at literary journals are not the most pressing news of the day, but the incident at Guernica reveals the extent to which elite American literary outlets may now be beholden to the narrowest polemical and moralistic approaches to literature. After the publication of Chen’s essay, a parade of mutual incomprehension occurred across social media, with pro-Palestine writers announcing what they declared to be the self-evident awfulness of the essay (publishing the essay made Guernica “a pillar of eugenicist white colonialism masquerading as goodness,” wrote one of the now-former editors), while reader after reader who came to it because of the controversy—an archived version can still be accessed—commented that they didn’t understand what was objectionable. One reader seemed to have mistakenly assumed that Guernica had pulled the essay in response to pressure from pro-Israel critics. “Oh buddy you can’t have your civilian population empathizing with the people you’re ethnically cleansing,” he wrote, with obvious sarcasm. When another reader pointed out that he had it backwards, he responded, “This chain of events is bizarre.”

Some people saw anti-Semitism in the decision. James Palmer, a deputy editor of Foreign Policy , noted how absurd it was to suggest that the author approved of the “good bombs” sentiment, and wrote that the outcry was “one step toward trying to exclude Jews from discourse altogether.” And it is hard not to see some anti-Semitism at play. One of the resigning editors claimed that the essay “includes random untrue fantasies about Hamas and centers the suffering of oppressors” (Chen briefly mentions the well-documented atrocities of October 7; caring for an Israeli family that lost a daughter, son-in-law, and nephew; and her worries about the fate of Palestinians she knows who have links to Israel).

Madhuri Sastry, one of the co-publishers, notes in her resignation post that she’d earlier successfully insisted on barring a previous essay of Chen’s from the magazine’s Voices on Palestine compilation. In that same compilation, Guernica chose to include an interview with Alice Walker, the author of a poem that asks “Are Goyim (us) meant to be slaves of Jews,” and who once recommended to readers of The New York Times a book that claims that “a small Jewish clique” helped plan the Russian Revolution, World Wars I and II, and “coldly calculated” the Holocaust. No one at Guernica publicly resigned over the magazine’s association with Walker.

However, to merely dismiss all of the critics out of hand as insane or intolerant or anti-Semitic would ironically run counter to the spirit of Chen’s essay itself. She writes of her desire to reach out to those on the other side of the conflict, people she’s worked with or known and who would be angered or horrified by some of the other experiences she relates in the essay, such as the conversation about the “good booms.” Given the realities of the conflict, she knows this attempt to connect is just a first step, and an often-frustrating one. Writing to a Palestinian she’d once worked with as a reporter, she laments her failure to come up with something meaningful to say: “I also felt stupid—this was war, and whether I liked it or not, Nuha and I were standing at opposite ends of the very bridge I hoped to cross. I had been naive … I was inadequate.” In another scene, she notes how even before October 7, when groups of Palestinians and Israelis joined together to share their stories, their goodwill failed “to straddle the chasm that divided us.”

Read: Why activism leads to so much bad writing

After the publication of Chen’s essay, one writer after another pulled their work from the magazine. One wrote, “I will not allow my work to be curated alongside settler angst,” while another, the Texas-based Palestinian American poet Fady Joudah, wrote that Chen’s essay “is humiliating to Palestinians in any time let alone during a genocide. An essay as if a dispatch from a colonial century ago. Oh how good you are to the natives.” I find it hard to read the essay that way, but it would be a mistake, as Chen herself suggests, to ignore such sentiments. For those who more naturally sympathize with the Israeli mother than the Gazan hiding from the bombs, these responses exist across that chasm Chen describes, one that empathy alone is incapable of bridging.

That doesn’t mean empathy isn’t a start, though. Which is why the retraction of the article is more than an act of cowardice and a betrayal of a writer whose work the magazine shepherded to publication. It’s a betrayal of the task of literature, which cannot end wars but can help us see why people wage them, oppose them, or become complicit in them.

Empathy here does not justify or condemn. Empathy is just a tool. The writer needs it to accurately depict their subject; the peacemaker needs it to be able to trace the possibilities for negotiation; even the soldier needs it to understand his adversary. Before we act, we must see war’s human terrain in all its complexity, no matter how disorienting and painful that might be. Which means seeing Israelis as well as Palestinians—and not simply the mother comforting her children as the bombs fall and the essayist reaching out across the divide, but far harsher and more unsettling perspectives. Peace is not made between angels and demons but between human beings, and the real hell of life, as Jean Renoir once noted, is that everybody has their reasons. If your journal can’t publish work that deals with such messy realities, then your editors might as well resign, because you’ve turned your back on literature.

After Kavanaugh: Christine Blasey Ford tells the rest of her story

In her memoir, ‘one way back,’ blasey ford details the chaos that ensued after she accused brett kavanaugh of sexually assaulting her.

Reading Christine Blasey Ford’s new memoir, I kept thinking of a tweet I read back in the spring of 2018, two months before President Donald Trump nominated Brett M. Kavanaugh to the U.S. Supreme Court. “Can you name all 59 women who came forward against Cosby?” a user named Feminist Next Door posted. “Cool so we agree that women don’t make rape accusations to become famous.”

Ford, of course, did become famous after accusing Kavanaugh of attempting to sexually assault her while both were in high school (Kavanaugh has always denied this happened). She came to Washington, delivered a memorable testimony — “ indelible in the hippocampus ” — and then descended into the kind of fame that, as she describes in the book, “ One Way Back ,” nobody would ever wish upon themselves. Death threats forced her family into a hotel room for months. Bodyguards accompanied her children to school. A decades-old fear of enclosed spaces (a fear that first started, she says, after Kavanaugh’s alleged attack) was now paired with a fear of open spaces as strangers wrote to her: “We know where you live. We know where you work. We know where you eat. … Your life is over.”

Before coming forward, Ford describes a charmed existence. She had long ago traded the stuffy Beltway of her teenage years for laid-back California. She was a weekday psychology professor and a weekend surfer. When she saw Kavanaugh’s name on Trump’s shortlist, she prayed for the nomination to go to anyone else so that she could go back to packing up snacks and wet suits for her family at their beach house. Why did she risk all of this to go public? In Ford’s telling, she never imagined that her story would become so polarizing or so huge, and once it did, it was too late to change her mind. It felt like a surfing metaphor: Paddling out, she writes, “is the hardest part. And you never, ever paddle back in once you’re out there. You catch the wave. You wipe out if you have to.”

Readers looking to “One Way Back” for a magic bullet to prove Kavanaugh’s guilt or innocence are out of luck. Ford doesn’t remember anything more than she’s already publicly recalled; there are no new witnesses or unearthed diary entries. What she gives instead is a thoughtful exploration of what it feels like to become a main character in a major American reckoning — a woman tossed out to sea and learning that the water is shark-infested, or at the very least blooming with red tide.

At times, she comes across as either deeply optimistic or unfortunately naive. Prehearing, Ford’s legal team suggested that she sit through a “murder board” — a mock interrogation designed to stress-test her story. She decided that her truth should be protection enough, not comprehending that she was declining a fairly standard form of preparation.

She was told she could bring a handful of guests to act as a supportive presence while she testified, and she chose friends and colleagues over relatives — she and her husband decided he should stay home with their sons so that they didn’t have to miss school; she worried that the long hearing would be physically uncomfortable for her elderly parents. But when she saw Kavanaugh flanked by his wife and daughters at his own testimony, she realized she’d misunderstood a fundamental rule in the game of optics.

“I didn’t know my integrity was on the stand as much as Brett’s,” she writes. Kavanaugh looked like a wholesome family man. She looked like a renegade. She woke up to a headline in The Washington Post that read: “Christine Blasey Ford’s family has been nearly silent amid outpouring of support.”

Of course, it turned out that things were more complicated with her family than even she had realized. After Kavanaugh was confirmed, Ford’s legal team approached her with a delicate question: Is it possible that her dad sent a letter to Kavanaugh’s father — they belonged to the same golf club — saying that he was glad Kavanaugh had been confirmed? Ford couldn’t believe this was true, and when she asked her dad, he assured her no letter was written. It’s not until a later conversation that he backtracked: He didn’t write a letter, but he did send an email. “Just gentleman to gentleman,” he explained awkwardly. “I should have just said, ‘I’m glad this is over.’ That’s what I meant.”

Oddly, Ford did know what he meant, and in the context of her father’s Washington, it makes sense: He was an old-school Republican for whom manners and decorum supersede everything — a trade-school graduate who was proud to propel his family into a country club lifestyle and who wanted to make sure they would still be welcomed in that lifestyle even after all this tricky business with his daughter. But her father’s actions were utterly devastating in the new political climate, in which every word could be weaponized and every text or email was a gotcha. The pair’s relationship hasn’t fully recovered by the end of the book, and it’s hard to imagine it ever will.

Returning to California after the confirmation hearings, Ford was catapulted into a new reality. On the one hand, she was invited to dinner at the homes of Oprah Winfrey and Laurene Powell Jobs. On the other hand, these dinners were the only times she felt safe leaving her house, figuring that Oprah must have even more security than she did. On the one hand, backstage invitations at a Metallica concert. On the other, an anxiety so deep and pervasive that she spent days on end wrapped in a gray Ugg-brand blanket. From time to time, she writes, people still asked her whether she thought she ruined Kavanaugh’s life, and she reacted with incredulity: “Despite the fact that Brett ultimately got the job. Despite the fact that he sits on the Supreme Court while I still receive death threats.”

There are inspirational moments, too: for every death threat, a dozen well-wishers; for every moment of self-doubt, another moment of reminding herself that she’s coming from a place of privilege — supportive family, steady income — and that putting herself through the wringer might make it easier on the next victim, the next time.

Did it? Will it? “One Way Back” is a blisteringly personal memoir of a singular experience. But it was most piercing to me as a memoir of the past half-decade, when long-buried wounds were tried in the court of public opinion as much as in the court of law, and when sexual assault allegations were treated as though they were about scoring political points more than settling psychic trauma.

If you believed Ford in 2018, “One Way Back” will give you a deeper appreciation for the woman behind the headlines. If you didn’t — well, I don’t know if the book will change your mind. But it might wiggle your mind a little bit. Because it’s impossible to picture why someone would lie to achieve the kind of fame that has been bestowed upon Ford. It’s hard enough to picture why someone would put themself through that nightmare to tell the truth.

One Way Back

By Christine Blasey Ford

St. Martin’s. 320 pp. $29

We are a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for us to earn fees by linking to Amazon.com and affiliated sites.

- Why is the royal family so bad at this? March 20, 2024 Why is the royal family so bad at this? March 20, 2024

- After Kavanaugh: Christine Blasey Ford tells the rest of her story March 13, 2024 After Kavanaugh: Christine Blasey Ford tells the rest of her story March 13, 2024

- A lot of moms can’t see themselves in Katie Britt’s kitchen March 8, 2024 A lot of moms can’t see themselves in Katie Britt’s kitchen March 8, 2024

Advertisement

More from the Review

Subscribe to our Newsletter

Best of The New York Review, plus books, events, and other items of interest

- The New York Review of Books: recent articles and content from nybooks.com

- The Reader's Catalog and NYR Shop: gifts for readers and NYR merchandise offers

- New York Review Books: news and offers about the books we publish

- I consent to having NYR add my email to their mailing list.

- Hidden Form Source

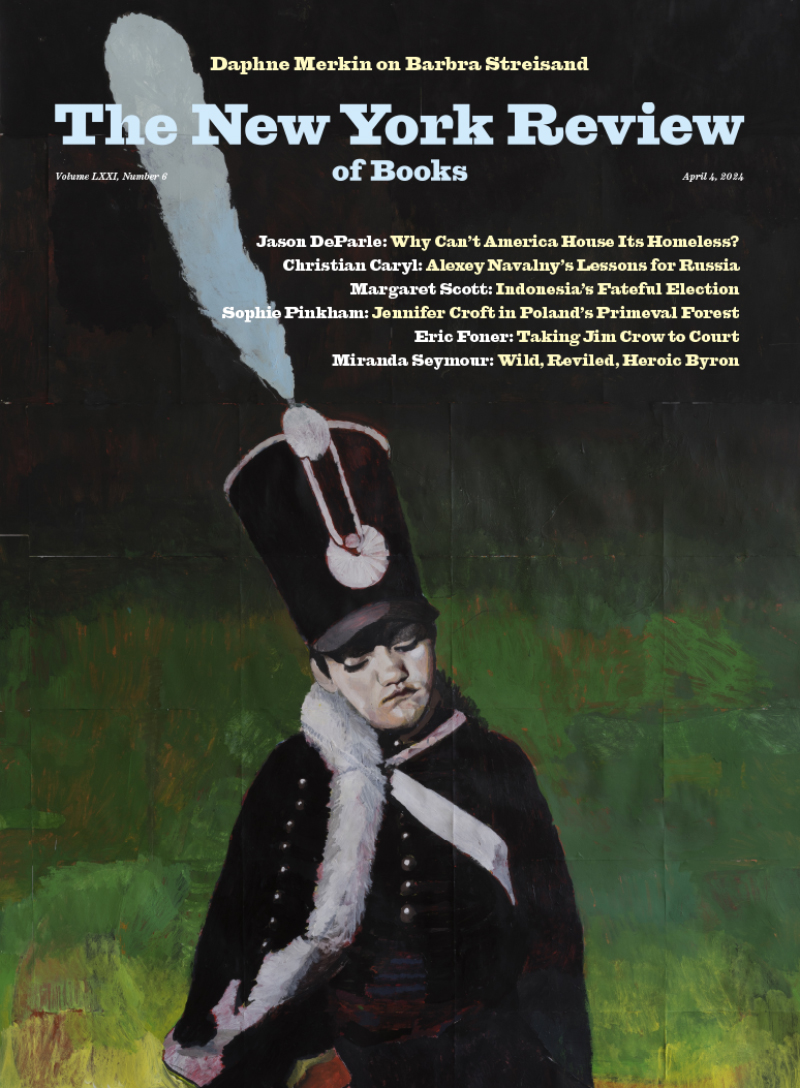

April 4, 2024

Current Issue

‘Thus I Lived with Words’

April 4, 2024 issue

Submit a letter:

Email us [email protected]

The Complete Personal Essays of Robert Louis Stevenson

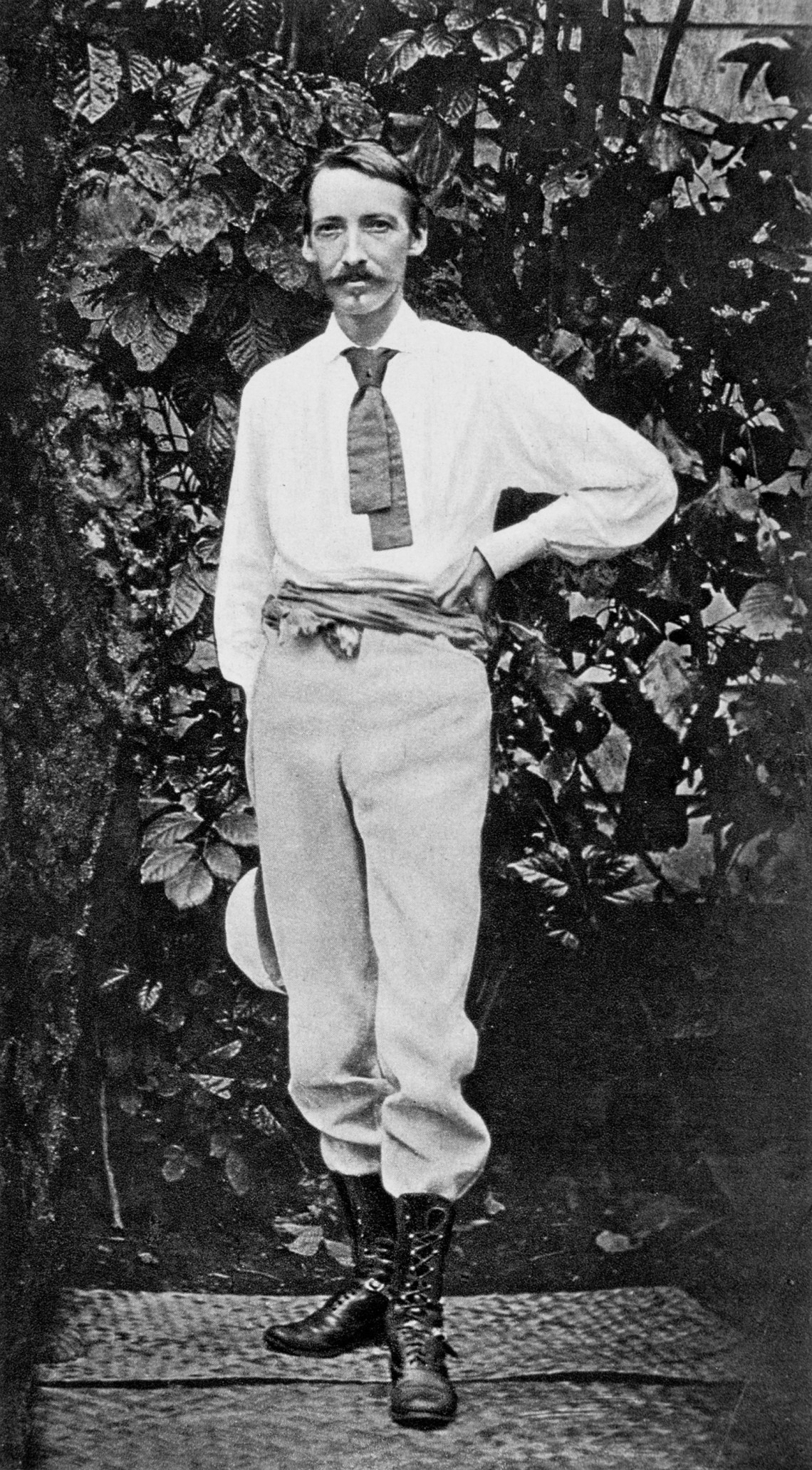

Robert Louis Stevenson, Vailima, Samoa, 1894

Known today as a writer of adventure stories for youth ( Treasure Island , Kidnapped ) or for his horror classic The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde , or even for his light-poetry collection A Child’s Garden of Verses , in his day Robert Louis Stevenson was celebrated equally for his essays. He wrote more than a hundred, of which seventy might be classified as personal. Edmund Gosse argued that these personal essays “reveal him in his best character” and that “if Stevenson is not the most exquisite of the English essayists, we know not to whom that praise is due.” Richard Le Gallienne predicted that “Stevenson’s final fame will be that of an essayist.” Once upon a time his essays were routinely offered as models in American college composition courses. Selections of them—from William Lyon Phelps’s Essays of Robert Louis Stevenson (1906) to The Lantern-Bearers and Other Essays (1988), astutely assembled by Jeremy Treglown—have sought to champion his excellence in the genre.

It has not been an easy sell. In part that may be because essays have never commanded the interest or respect that fiction has, but it may also be because the reading public has resisted relinquishing its settled idea about Stevenson as a romantic fantasist. Now Trenton B. Olsen, an associate professor of English at Brigham Young University, has pulled together the most copious selection so far, reproducing not only Stevenson’s dozen or so celebrated essays but also his uncollected published essays and his undergraduate ones. All this gives us the chance to assess the range and stature of a writer who, according to Olsen, was in his day “considered the most successful essayist of his generation.”

Stevenson was born in 1850 in Edinburgh, Scotland, into a distinguished family of lighthouse engineers. His father, Thomas Stevenson, had invented an ocular device for lighthouses and hoped that his son would go into the family business. But Robert showed little interest in engineering, cutting classes at the University of Edinburgh, and tempered his truancy only when his father coerced him to pursue a law degree instead. In one of his most famous essays, “An Apology for Idlers,” Stevenson cheekily argued for “certain other odds and ends that I came by in the open street while I was playing truant…. Suffice it to say this: if a lad does not learn in the streets, it is because he has no faculty of learning.”

Rebelling against his Scottish Calvinist upbringing, with its narrow emphasis on “respectability” (a word he always wrote with a sneer), and turning away from his family’s religious convictions (to his devout father’s deep sorrow), Stevenson asserted that “there is no duty we so much underrate as the duty of being happy.” He took to dressing bohemian, drinking, and visiting brothels. In fact he was hardly idle, insofar as he spent every available moment trying to master his preferred vocation, literature:

All through my boyhood and youth, I was known and pointed out for the pattern of an idler; and yet I was always busy on my own private end, which was to learn to write. I kept always two books in my pocket, one to read, one to write in. As I walked, my mind was busy fitting what I saw with appropriate words; when I sat by the roadside, I would either read, or a pencil and a penny version-book would be in my hand, to note down the features of the scene or commemorate some halting stanzas. Thus I lived with words. And what I thus wrote was for no ulterior use, it was written consciously for practice.

Such a beautiful description of a young author-to-be’s dedication. But wait, there’s more: “I have thus played the sedulous ape to Hazlitt, to Lamb, to Wordsworth, to Sir Thomas Browne, to Defoe, to Hawthorne, to Montaigne, to Baudelaire, and to Obermann.” (Notice the proliferation of personal essayists in his list of models.) He catches himself—“I hear some one cry out: But this is not the way to be original!”—then declares that imitation is the royal road to originality, citing Montaigne’s drawing on Cicero. “It is only from a school,” Stevenson says, “that we can expect to have good writers.”

At a time when the English essay had gravitated toward the more formal, intellectual, stately prose of Thomas Carlyle, Matthew Arnold, John Ruskin, and Walter Pater, Stevenson chose to attach himself to the older, more informal school of William Hazlitt and Charles Lamb. He took up many of the personal essay’s standard themes, such as friendship, talk, walking around, elderly relations, childhood, the past, and everyday objects. (See his playful essay “The Philosophy of Umbrellas.”) He was particularly enamored of Hazlitt, insisting that “though we are mighty fine fellows nowadays, we cannot write like Hazlitt.” In his essay “Walking Tours” he cited Hazlitt’s “On Going a Journey” as being “so good that there should be a tax levied on all who have not read it.”

Stevenson’s own essays are more genial than those of the combative, truculent Hazlitt, but he took from the older writer a liking for energetic, rhythmic prose. He even toyed with the idea of writing a biography of Hazlitt, then gave up the project in dismay when he came across Liber Amoris , the astonishingly frank account Hazlitt wrote of his unrequited infatuation with an innkeeper’s daughter. (There was a prim, Victorian avoidance of sex in Stevenson’s writing, despite his appetite for experience.)

One motivation that kept him seeking adventures was his ill health, a pulmonary weakness he had suffered ever since he was a boy. Few writers have been as consistently aware of encroaching mortality as Stevenson, and he tried to cheat death or at least stay one step ahead of it, cramming as much living as he could into his brief forty-four years. “It is better to lose health like a spendthrift than to waste it like a miser,” he wrote. As the biographer-critic Treglown succinctly put it:

He had always wanted to escape from the certitudes and complacencies, religious, moral and social, of his Edinburgh upbringing, and had been helped in doing so by the travelling his poor health necessitated. Visits to foreign spas were not only desirable, but required.

The title of one essay, “Ordered South,” says it all.