- Open access

- Published: 17 January 2024

Breast cancer survivorship needs: a qualitative study

- Rahimeh Khajoei ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3770-6790 1 ,

- Payam Azadeh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1771-7377 2 ,

- Sima ZohariAnboohi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3422-9420 3 ,

- Mahnaz Ilkhani ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5454-4041 3 &

- Fatemah Heshmati Nabavi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9842-966X 4

BMC Cancer volume 24 , Article number: 96 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

967 Accesses

Metrics details

Breast cancer rates and the number of breast cancer survivors have been increasing among women in Iran. Effective responses from healthcare depend on appropriately identifying survivors’ needs. This study investigated the experience and needs of breast cancer survivors in different dimensions.

In this qualitative content analysis, semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted from April 2023 to July 2023. Data saturation was achieved after interviewing 16 breast cancer survivors (BCSs) and four oncologists using purposive sampling. Survivors were asked to narrate their experiences about their needs during the survivorship. Data were analyzed with an inductive approach in order to extract the themes.

Twenty interviews were conducted. The analysis focused on four central themes: (1) financial toxicity (healthcare costs, unplanned retirement, and insurance coverage of services); (2) family support (emotional support, Physical support); (3) informational needs (management of side effects, management of uncertainty, and balanced diet); and (4) psychological and physical issues (pain, fatigue, hot flashes, and fear of cancer recurrence).

Conclusions

This study provides valuable information for designing survivorship care plans. Identifying the survivorship needs of breast cancer survivors is the first and most important step, leading to optimal healthcare delivery and improving quality of life. It is recommended to check the financial capability of patients and take necessary measures for patients with financial problems. Additionally, support sources should be assessed and appropriate. Psychological interventions should be considered for patients without a support source. Consultation groups can be used to meet the information needs of patients. For patients with physical problems, self-care recommendations may also be useful in addition to doctors’ orders.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

According to the Globocan website, breast cancer is the most common cancer among women. Breast cancer was the most common cancer in Iran in 2020 in both sexes and the fifth cause of death in both sexes; however, it is the leading cause of death in women [ 1 ]. Due to early diagnosis and improvements in treatment methods, the prognosis and survival rate of women with breast cancer have enhanced significantly worldwide [ 2 ]. Breast cancer survivors face many problems and needs in different dimensions: psychological, physical, social, etc. [ 3 ]. These needs and issues during the survivorship period are different during the active phase of cancer treatment [ 4 ]. Physical and psychological symptoms include fatigue, pain, osteoporosis, premature menopause, fear of disease recurrence, sexual problems, and infertility [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. To deal with these health needs, many patients require medical, psychological, and social care for more than ten years after diagnosis [ 8 , 9 ].

The growing population of survivors, along with their multiple needs, is a challenge for healthcare providers and health policymakers, who need to provide a good standard of care during the survival period and meet the different dimensions of the needs of these patients after treatment [ 3 , 10 ]. Failure to meet these needs is associated with negative consequences such as decreased satisfaction with care, poor adherence to treatment, decreased quality of life, and increased anxiety and depression [ 11 ]. The current trend in modern medicine is changing from a disease-based model to a patient-centered model in which patients are active and their preferences and needs are considered in care [ 12 ]. Therefore, the first step in planning supportive care services for cancer patients is to identify their care needs [ 13 ]. To date, several studies have investigated the needs and experiences of breast cancer survivors and obtained different results. The need for help in dealing with problems such as financial distress [ 14 ], Pain [ 15 ], Memory problems [ 16 ], Fear of disclosure [ 17 ], concerns relating to body image, femininity, altered physical appearance, and self-confidence [ 18 ] are among the needs experienced by breast cancer survivors. In 2023, a systematic study on the needs of breast cancer survivors showed that most of these patients had psychological and informational needs [ 19 ]. In assessing the needs of BCSs, it is essential to consider culture, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, birthplace, and native language. The elements of the survivorship journey may be somewhat similar for all women, yet we cannot assume that their experiences are monolithic, regardless of the context. Ethnic, racial, and cultural diversity may affect survivors’ needs. Iran is a country with unique cultural and religious characteristics and people’s behavior and attitude towards disease are different depending on their culture. As such, conducting research across cultures is necessary. For example, the family holds a valuable position in Iran. Cancer affects physical, mental, social, and economic dimensions of patients and their families. In this situation, preserving and consolidating the family foundation is important and may create different needs for patients. Therefore, considering the differences in the ethnic, cultural, and socioeconomic background of Iran, this study aimed to investigate the needs and experiences of breast cancer survivors in the country.

This qualitative study was conducted using a conventional content analysis approach in order to investigate the experiences and needs of breast cancer survivors. Qualitative research methods seek to discover and understand people’s inner worlds. As experiences form the structure of truth for each person, researchers can discover the meaning of phenomena from their perspective by taking into account people’s experiences [ 20 ]. In conventional content analysis, classes are extracted directly from the data text. This approach is used in studies whose purpose is to describe a phenomenon; this method was used in the present study [ 21 ].

Contributors

The qualitative research participants had deep experience of the phenomenon under study [ 19 ]. The participants in the study were breast cancer survivors (14 participants), patients’ families (two participants), and healthcare professionals (four participants). Women who had completed their treatment courses at a university hospital in Tehran between four and 18 months prior and were visiting the hospital for follow-up care were included in the study using targeted sampling. To achieve the maximum difference in the samples, participants with maximum diversity were included in the study over a period of three months. Participants of different ages, marriages, education levels, income, and ethnicities were included in the study. The sampling was continued until data saturation was achieved. The inclusion criteria were patients between 18 and 60 years of age, literacy, completion of treatment, non-metastatic cancer, and stable clinical conditions. The exclusion criteria were cancer recurrence or metastasis, secondary cancers, and cognitive impairment.

Collecting data

Two separate interview guides for survivors and healthcare professionals were developed by the research team, using expert input on the needs of cancer survivors. These guidelines are based on a literature review of the needs of survivors of breast cancer. In-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted in order to collect the data. After informed consent was obtained, an interview method with open-ended questions focusing on the study objectives was conducted. Each interview was conducted and analyzed. The interviews were scheduled at a convenient time and location for the interviewees. A total of 20 face-to-face and telephone interviews were conducted, lasting 45 min each. The data were collected between April 20 and July 30, 2023. The interviews began with an open-ended question relating to the needs and experiences of breast cancer survivors. Based on the interviewees’ answers, the interview process was directed towards achieving the main goal of the research. Exploratory questions were asked in order to attain a deeper understanding of the phenomena. The interviews continued until complete information saturation was reached. Full saturation occurs when classes and subclasses are completed, and new data do not add anything to these classes; at this point, no new data are obtained from the interviews and only previous information is repeated. Immediately after the end of the interviews, all interviews were recorded verbatim using the recording device and transcribed.

The interview guide questions included the following questions:

What were the most important issues you faced after completing your treatment?

What side effects did you experience and how did you deal with them?

What feelings did you experience during your recovery? Fear, anxiety, depression, despair, anger, fear of cancer returning, loss of self-confidence?

Explain your emotional life.

In addition, according to the participants’ answers, the following questions were addressed:

In what areas did you need more training and information?

What physical problems and complications do you currently face in need of support?

Do you need support in establishing relationships with others and being present in the community and workplace?

Do you feel that you need more support in your emotional and family relationships?

Do you need help from others in performing daily tasks?

Do you have trouble remembering and recalling events?

In addition, interview guide questions for healthcare providers include the following:

From your perspective, what are the most important issues and needs of breast cancer survivors? (in physical, mental, informational, cognitive dimensions, etc.)

Are there any issues that are more problematic for the Iranian recoveries?

The researcher further explored participants’ answers to each question. Furthermore, by restating and returning to the salient points or a summary of the participants’ answers, we confirmed the correctness of the data and increased the credibility of the results. At the end of each session, we asked questions such as “Is there anything else you would like to add?” and “Is there another question I should have asked?” Participants were asked to express any further experience or additional information. In addition, permission was obtained from the participants for future calls or interviews. At the end of each interview, the interviews were listened to several times at the earliest possible time and transcribed verbatim. The moods and characteristics of the participants were recorded along with the interviews. The mood and characteristics of the participants helped code the text of the interviews. That the codes accurately express a person’s understanding of the desired situation. The text of the interviews with pseudonyms was entered into MAXQDA 2020 software for data storage, retrieval, and analysis.

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using conventional content analysis, based on the steps introduced by Graneheim and Lundman [ 22 ]. The sentences and phrases describing the needs and experiences of survivors were coded. The first and third researchers coded the texts of the interviews separately. The coded text was reviewed by a responsible researcher. Any disagreements were discussed to reach a consensus. Subsequently, the central concept of each class and the main and abstract concepts were defined. Following this, based on a constant comparison of similarities and differences, the codes that indicated a single topic were placed in a class, the subclasses and classes were categorized, and the core codes were formed. In the fifth step, the central concept of each class and the main and abstract concepts were defined.

Data integrity and robustness

To validate the research findings, the criteria of acceptability or validity, transferability, reliability, trust or stability, and ability, based on Lincoln and Guba, were used [ 23 ]. To ensure the validity of the data, in addition to allocating sufficient time for data collection and immersion, semi-structured interviews were conducted; the maximum variety in sampling was observed by interviewing people of different ages, education, income, and use at various stages of the disease. Sampling continued until the data reached saturation and the most appropriate semantic unit was selected. Internal validity of content analysis was condcuted; this was evaluated for its face validity. To validate the content, a panel of experts (research team) supported the generation of concepts or coding topics; these were also reviewed by the participants. For this purpose, the interview text and extracted codes were presented to participants, who commented on their accuracy [ 24 ]. In this study, a research audit, a detailed review of data by an external observer, was used to increase the stability of the research. In addition, the period of data collection (interviews) was carried out as quickly as possible and all participants were asked about the same topic [ 22 ]. To facilitate transferability, the researcher has provided a clear description of the platform, the method of selecting and characterizing the participants, the data collection, and the analysis process so that the reader can judge the applicability of the findings to other situations. In addition, rich and detailed findings with appropriate quotations and authentic documents are presented in order to increase transferability [ 25 ]. To increase the verifiability of the data, all research stages, methodology, and decisions taken in the research stages are explained in clear detail so that they can be followed by other researchers if necessary. In addition, all raw data and recorded notes, documents, and interviews have been retained for future review [ 26 ].

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in Tehran (IR. SBMU. PHARMACY. REC.1402.005). Informed consent was obtained from the research participants, and they were also informed about the confidentiality of their information.

Participants

The medical records of 450 BCSs were reviewed. 56 patients met the inclusion criteria for this study. 28 survivors could not be contacted, 12 declined to participate, and 16 participated in the interviews. Among the survivors, 64% were married and about half were between 30 and 50 years old. 60% had a higher education level and over 85% had an average income. Of the 12 oncologists who were invited to participate in this study, four agreed to participate, with a response rate of 33.3%.

The analysis focused on four central themes: (1) financial toxicity (healthcare costs, unplanned retirement, and insurance coverage of services); (2) family support (emotional support, Physical support); (3) informational needs (management of side effects, management of uncertainty, and balanced diet); and (4) psychological and physical issues (pain, fatigue, hot flashes, and fear of cancer recurrence).

Financial toxicity

The high cost of drugs and treatment, along with reduced work productivity and subsequent loss of income, impose a heavy financial burden on cancer patients, which in turn imposes a unique stress known as financial toxicity [ 27 ]. In this study, most patients mentioned financial problems as their most challenging issue.

Healthcare costs

One source of financial problems is the costs associated with cancer care services (e.g., medications, supplies, copayments, and transportation) [ 28 ]. Patients who report cancer-related financial problems or high healthcare costs are more likely to avoid or delay their medical care or prescribed medications. This may slow their healing process or aggravate the disease [ 29 ]. The participants in this study complained about the high costs of drugs and medical procedures. One participant said:

I had finished chemotherapy three months ago and was told to start radiation. But I couldn’t afford it, so I gave it up.

Coverage of insurance services

Another financial problem for the participants was that insurance did not cover the cost of some treatments. Obtaining health insurance did not fully protect against cancer-related financial problems. One participant said:

I am a worker and I have to work hard to improve my wife’s condition. Thank God, most of my wife’s treatment costs were paid by supplementary insurance. However, now the problem is that my wife has to undergo a mastectomy and she is very upset about the change in her appearance and wants to have breast implants. However, because it is considered a cosmetic procedure, unfortunately, insurance does not accept the payment and we are not able to pay the cost.

Unplanned retirement

One source of financial distress is reduced income due to loss of employment, missing work, or unplanned retirement [ 28 ]. In this study, it was found that some patients were forced to retire and had difficulty with paying the treatment costs. One participant said:

I am a teacher, and I was forced to retire due to illness. My pension is not sufficient to pay for my medicine and treatment. I really don’t know what to do to pay for the treatment.

Family support

Emotional support.

A remarkable finding obtained from the participants’ statements was that emotional support from their family, partner, and children played an important role in reducing their physical and psychological symptoms. Survivors who had a strong source of emotional support experienced fewer physical symptoms and a better mental state; among these patients, psychological symptoms such as stress, anxiety, and depression were far less common. Studies have shown that BCSs face various stresses during the course of the disease and need comprehensive support, including social and family support, to deal with these stressful factors and manage their resulting conditions better [ 30 ]. Family involvement increases their ability to cope [ 31 ]. Some of the participants’ statements support this:

After the radiation treatment, I felt much better because I went to my family in the city. They supported me a lot, making me feel better.

I live alone. Initially, my family supported me, but they left me little by little. Of course, they are right, our problem is ongoing, and I do not like to disturb anyone. I am struggling with several complications. The current problems include severe muscle pain, fatigue, weakness, and lethargy. I feel lonely. I often feel stressed and anxious.

The husband of one of the participants said:

My wife is not experiencing any particular problem at the moment because I am paying attention to her in every way. She is my life partner, and I should be by her side facing difficulties. I will do whatever I can to make her feel better. Thank God; there is no problem now.

Considering that partners play an essential role in providing emotional support, financial management, and decision-making regarding their spouses’ cancer treatment, there is a need to involve them in psychological interventions [ 32 ].

Physical support

Due to the complications of the treatment, the participants needed physical support from the family to fulfill their responsibilities. Patients who lacked physical support from the family had many problems in carrying out daily responsibilities and activities. One participant said:

I separated from my wife and live alone. My hand is swollen and painful, but I have to work with this condition; And I don’t have anyone to help me and this is really hard for me.

Informational needs

Almost all participants stated that they did not receive any information on what to expect. and would have liked to receive more information about management of side effects and balanced diet.

Management of side effects

Information needs were one of the most important needs for the survivors. Most participants said that they had not been given any training program. Many women reported that they had experienced persistent side effects from treatment for which they were poorly prepared. Moreover, they did not receive any related training. This lack of information confused them and exacerbated complications. One participant said:

I was not provided with any training. I was faced with cases where I did not know what to do. For example, because of menopause, I used to get hot flashes and I was very bothered. Later, they said you could use cool liquids like chicory, but I did not know what to do, and I tolerated it.

Management of uncertainty

One of the informational needs for BCSs was ensuring complete recovery. They were confused about being completely healed. Furthermore, they wanted more information about disease prevention for their daughters. One participant said:

My most important question during the recovery period is whether I have fully recovered. Does cancer have a chance of coming back? Is it possible for my daughter to develop cancer in the future?

One of the specialists stated:

Facing an uncertain future and the fear of the disease returning (especially the concern for children) is one of the most important concerns of BCSs. They should know that creating a suitable lifestyle and continuous follow-up can prevent the return of the disease.

Balanced diet

Another need expressed by patients was information about healthy eating or balanced eating (food to eat, food to avoid). One of the participants said:

In this regard, we did not receive sufficient training. I do not know what food is good for me. There is some information on the internet, but it is unreliable. I cannot always ask my doctor these questions. They should teach us about proper nutrition.

Psychological and physical issues

Most participants reported post-mastectomy, chest/arm, musculoskeletal, and lymphatic pain. Chronic pain is one of the most troublesome side effects of breast cancer treatment and affects patients’ quality of life [ 33 ]. Chronic pain causes discomfort and fatigue, reduces appetite and sleep, and interferes with many activities of daily living [ 34 ]. Some of the participants’ statements regarding pain are provided below. One of the specialists stated:

Survivors face long-term complications of treatment, such as myalgia, osteoporosis, and hot flashes due to hormonal treatments, respiratory disorders due to receiving radiotherapy, and paresthesias of limbs due to receiving chemotherapy drugs, and they should have the necessary information and background to face these complications.

Participants stated:

My main problem was that I experienced so much musculoskeletal pain that I could not move. I was admitted to the hospital a couple of times, and a bunch of drugs were injected into me, but it worked temporarily, and the pain recurred.

My left hand is in severe pain due to the removal of the lymph nodes, which makes it difficult for me to do my chores and I need the help of others.

Fatigue was another physical symptom mentioned by most participants. Fatigue is the most common and frequent symptom of BCSs after treatment [ 35 ]. Studies have shown that low physical activity, decreased muscle mass, and impaired physical fitness are potential causes of fatigue in BCSs [ 36 ]. One participant said:

Sometimes I am so tired that I have to take a break several times while doing a normal daily task and continue again.

Hot flashes

Most of the participants stated that they experienced hot flashes due to menopause. Hot flashes are a common problem in breast cancer survivors, affecting their work performance [ 37 ]. One of the participants stated:

I have night sweats and hot flashes due to menopause. It bothers me a lot; it starts with my head and then with the rest of my body. Anyone around me will notice that I am sweating profusely. When I get this condition at night, I wake up, get annoyed, and cannot sleep anymore. I drink cold liquids, and it gets better but not completely.

Fear of cancer recurrence

Fear of cancer recurrence is one of the most commonly reported concerns among cancer survivors [ 38 ]. Most participants experienced FCR; it was the most important source of stress and worry after breast cancer diagnosis and treatment, involving the fear of cancer returning to the breast, metastasizing, or returning as a second cancer. One of the contributors said:

I do not have much stress and anxiety because my doctor told me that my disease has progressed. My only concern is whether my cancer returns?

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the needs and experiences of Iranian BCSs. The most important finding of this study was the patients’ experience with financial problems. Most patients had financial problems associated with cancer care services (e.g., therapeutic procedures, supplies, medications, and transportation) and reduced income due to loss of employment, missing work, or unplanned retirement. In Iranian government hospitals, all healthcare services are based on insurance. Patients who use these services in hospitals are required to pay a percentage of the treatment cost. Usually, cosmetic procedures are not included in these insurance programs. However, the increase in inflation and prices has caused most patients to experience financial problems. This finding is consistent with that of a study by Autade and Chauhan, in which all BCSs reported financial problems [ 39 ]. In addition, in a study by Carrera (2018), 28–48% of cancer survivors experienced financial toxicity based on monetary measures and 16–73% experienced financial toxicity based on subjective measures [ 40 ]. In a study by Barthakur et al. (2016), finances relating to treatment were a major concern for survivors and there was a need for information on reducing healthcare costs [ 41 ]. Over 8% reported that providing for the financial needs of their families was a severe problem [ 42 ]. Patients who report cancer-related financial problems or high costs may be more likely to forgo or delay prescription medications or medical care [ 29 ]. The inability to afford household expenses is one of the most commonly reported reasons for delayed medical care among cancer patients [ 43 ]. Financial problems, if not identified, can negatively affect the physical, psychological, and socioeconomic status of survivors and lead to poorer access to health services and consequently poorer health status and health-related quality of life [ 44 ]. Research shows that health professionals recognize patients’ financial concerns but may not be qualified to address them [ 44 ]. Healthcare providers can take several steps to reduce patients’ financial difficulties, including: (1) considering the cost of multiple treatment regimens with similar effects, (2) providing cancer cost estimates to patients, (3) considering treatment benefits, (4) assessing patients for financial toxicity, and (5) educating and assisting patients about insurance benefits and other financial assistance institutions that may be available to them [ 42 ].

Another finding of this study relates to patients’ experience of support resources. Consistent with Iranian culture, in this study family members were a valuable and main source of support for the BCSs. In the study of Lee et al., family members, including adult children and spouses, were the main source of support for all participants [ 45 ].

Upon receiving emotional support from their family, patients felt reassurance, acceptance, and attention. Those who had family support felt less anxious and depressed, and their physical symptoms were much fewer. The effective role of emotional support for patients has been reported in several studies [ 5 , 9 , 46 ]. Wilson et al. reported that support from friends and family is a positive strategy for reducing stress and anxiety and coping with illness [ 47 ]. In a study by Moradi et al. (2013), supportive care needs in women with breast cancer decreased after their husbands were educated about familiarity with breast cancer disease, symptoms and complications of the disease, and treatment. It has been suggested that caregivers use training sessions to reduce the needs of women with cancer [ 48 ]. These results were inconsistent, however, with those of Thewes (2004) and Arora (2007) [ 9 , 49 ]. They both concluded that friends and family members of patients with cancer tend to decrease or withdraw their support after treatment completion. The family’s role in improving patient outcomes cannot be overemphasized.

The study shows that patients who do not have access to a family support source have a greater tendency to use social support networks [ 50 ]. The researchers could create access to social support networks for patients who do not receive family support. Additionally, the role of support groups cannot be ignored. Support groups consisted of people with common experiences. In Iran, there are many support groups for cancer patients. Experiencers with any type of cancer can declare their readiness to participate in these groups by registering on related sites. These groups usually have weekly or monthly meetings. These meetings are held in person or virtually, according to the position of the group members. According to the needs of the members, the content of these meetings can be informative, reminiscent, fun, sports, cooking, or any topic desired by the majority of the members. Chou et al. (2016) showed that support groups help reduce psychological distress and increase the quality of life of patients with breast cancer. It is also possible to educate patients’ families about the needs of those who have recovered. Moghaddam Tabrizi et al. (2018) conducted an interventional study and trained patients’ families in family participation, optimism, coping with cancer, reducing uncertainty, and managing symptoms. The findings indicated a significant improvement in overall cancer coping scores on all subscales, including individual, positive focus, coping, deviation, planning, and interpersonal communication [ 31 ].

The participants also stated that they had unmet information needs in the areas of management of side effects, nutrition, and uncertainty management. Previous studies have also identified informational needs as the most common need for BCSs [ 3 , 5 , 51 ], even for survivors who have been diagnosed and treated for several years. These needs often include information on diet and nutrition, mental health counselling, infertility, and spiritual counselling [ 52 ]. Previous studies have indicated that BCSs often feel unready for the side effects that linger after therapy [ 17 , 18 ]. In a study by Pembroke et al., almost half of the participants reported informational needs associated with side effects of treatment [ 52 ]. In this study, patients met their information needs through the Internet; however, they had doubts regarding the use of this information. The high use of the Internet by patients with cancer suggests that healthcare providers may not be adequately meeting patients’ information needs [ 53 ].

Germino et al. (2013) conducted an intervention study with the aim of determining the impact of uncertainty management intervention on reducing uncertainty, better uncertainty management, fewer breast cancer-specific concerns and more positive psychological outcomes. The intervention consisted of a written CD and a manual with four weekly 20-minute training calls. The findings showed that BCS who received the intervention reported a reduction in uncertainty and significant improvement in behavioral and cognitive coping strategies for managing uncertainty, self-efficacy, and sexual dysfunction [ 54 ].

Physical problems were also reported by most participants. The patients mostly complained of pain, fatigue, and hot flashes. This finding is consistent with the results of the present study [ 9 , 16 , 17 , 39 ]. In the study by Bu et al. (2022), fatigue and pain were reported in 40.7% and 37.2% of the subjects respectively [ 55 ]. Studies have shown that the use of exercise-based interventions plays an effective role in reducing the pain and fatigue of breast cancer survivors [ 56 , 57 ].

Studies have also shown that mobile health education intervention improves cancer-related fatigue among breast cancer survivors [ 58 ]. mHealth interventions involve the adoption of mobile technologies to provide educational information, help users manage their own conditions and behaviors, and deliver healthcare to improve the health of users [ 59 ]. Integrating training to manage fatigue as part of routine care among breast cancer survivors is recommended [ 58 ].

The most important mental disorder experienced by patients was the fear of recurrence. The results of this study are similar to those of a previous study, which showed that the most common unmet need was help with coping with the fear of recurrence [ 60 , 61 , 62 ]. In the study of Brennan et al. (2010), fear of cancer recurrence was reported by 38% of the participants and emerged as the highest-ranked unmet need in all age groups [ 63 ]. In this study, fear of recurrence was identified as a key issue for cancer survivors [ 64 , 65 , 66 , 67 ].

The remarkable findings obtained from the interviews with health care professionals were that they mentioned the long-term complications caused by treatment procedures such as radiotherapy and chemotherapy in breast cancer survivors, including pain, fatigue, and hot flashes. Survivors have also reported these complications. According to healthcare professionals, facing an uncertain future, fear of cancer recurrence, and body image concerns are the most important concerns for breast cancer survivors. These results are consistent with those reported by Wells et al. [ 68 ].

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, while the BCSs were diverse, all were recruited from a comprehensive cancer center in Tehran, where they were referred to receive survivorship care. They may differ in other centers. Second, we did not use random sampling to obtain a sample of study participants. Instead, we used purposive sampling, a sampling approach commonly used in qualitative research, in order to select participants who were particularly knowledgeable about the phenomenon under study. Third, a qualitative method was used in this study, which does not allow the testing of a specific hypothesis. Fourth, we used literate participants; different results may be obtained from illiterate individuals.

The results of this study can be used to design survival care programs for Iranian BCS. Therefore, patients’ support resources should be reviewed and measured. Appropriate psychological interventions could be used for patients who do not have a source of support. The financial ability of patients should be assessed, and necessary measures should be considered for patients with financial problems. All the patients were provided with an educational program tailored to their needs. Consultation groups could be used to meet the information needs of the patients. In patients with physical problems, self-care recommendations may also be useful in addition to doctors’ orders.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to ethical restrictions. but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Breast Cancer Survivor

Survivorship care plans

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.

Article Google Scholar

DeSantis CE, Ma J, Gaudet MM, Newman LA, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, et al. Breast cancer statistics, 2019. Cancer J Clin. 2019;69(6):438–51.

Cheng KKF, Cheng HL, Wong WH, Koh C. A mixed-methods study to explore the supportive care needs of breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2018;27(1):265–71.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Joshi A, Larkins S, Evans R, Moodley N, Brown A, Sabesan S. Use and impact of breast cancer survivorship care plans: a systematic review. Breast Cancer. 2021;28(6):1292–317.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Dsouza SM, Vyas N, Narayanan P, Parsekar SS, Gore M, Sharan K. A qualitative study on experiences and needs of breast cancer survivors in Karnataka, India. Clin Epidemiol Global Health. 2018;6(2):69–74.

Fong EJ, Cheah WL. Unmet supportive care needs among breast cancer survivors of community-based support group in Kuching, Sarawak. International journal of breast cancer. 2016;2016.

Hubbeling HG, Rosenberg SM, González-Robledo MC, Cohn JG, Villarreal-Garza C, Partridge AH, et al. Psychosocial needs of young breast cancer survivors in Mexico City, Mexico. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(5):e0197931.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Lo-Fo‐Wong DN, de Haes HC, Aaronson NK, van Abbema DL, den Boer MD, van Hezewijk M, et al. Risk factors of unmet needs among women with breast cancer in the post‐treatment phase. Psycho‐Oncology. 2020;29(3):539–49.

Thewes B, Butow P, Girgis A, Pendlebury S. The psychosocial needs of breast cancer survivors; a qualitative study of the shared and unique needs of younger versus older survivors. Psychooncology. 2004;13(3):177–89.

Richter-Ehrenstein C, Martinez-Pader J. Impact of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment on work-related life and financial factors. Breast Care. 2021;16(1):72–6.

Mayer DK, Nasso SF, Earp JA. Defining cancer survivors, their needs, and perspectives on survivorship health care in the USA. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(1):e11–e8.

Chae BJ, Lee J, Lee SK, Shin HJ, Jung SY, Lee JW, et al. Unmet needs and related factors of Korean breast cancer survivors: a multicenter, cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer. 2019;19(1):839.

Rahmani A, Ferguson C, Jabarzadeh F, Mohammadpoorasl A, Moradi N, Pakpour V. Supportive care needs of Iranian cancer patients. Indian J Palliat Care. 2014;20(3):224–8.

Buki LP, Rivera-Ramos ZA, Kanagui-Muñoz M, Heppner PP, Ojeda L, Lehardy EN, et al. I never heard anything about it: knowledge and psychosocial needs of Latina breast cancer survivors with lymphedema. Women’s Health. 2021;17:17455065211002488.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gisiger-Camata S, Adams N, Nolan TS, Meneses K. Multi-level assessment to reach out to rural breast cancer survivors. Women’s Health. 2016;12(6):513–22.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gisiger-Camata S, Adams N, Nolan TS, Meneses K. Multi-level Assessment to Reach out to rural breast Cancer survivors. Womens Health (Lond). 2016;12(6):513–22.

Cappiello M, Cunningham RS, Tish Knobf M, Erdos D. Breast cancer survivors: information and support after treatment. Clin Nurs Res. 2007;16(4):278–93.

Galván N, Buki LP, Garcés DM. Suddenly, a carriage appears: social support needs of Latina breast cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2009;27(3):361–82.

Khajoei R, Ilkhani M, Azadeh P, Anboohi SZ, Nabavi FH. Breast cancer survivors–supportive care needs: systematic review. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. 2023;13(2):143–53.

Speziale HS, Streubert HJ, Carpenter DR. Qualitative research in nursing: advancing the humanistic imperative. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88.

Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today. 2004;24(2):105–12.

Lincoln YS, Guba EG. But is it rigorous? Trustworthiness and authenticity in naturalistic evaluation. New Dir Program Evaluation. 1986;1986(30):73–84.

Corbin J, Strauss A. Strategies for qualitative data analysis. Basics of Qualitative Research Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2008;3(104135):9781452230153.

Google Scholar

Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–15.

Lietz CA, Langer CL, Furman R. Establishing trustworthiness in qualitative research in social work: implications from a study regarding spirituality. Qualitative Social work. 2006;5(4):441–58.

Lentz R, Benson AB III, Kircher S. Financial toxicity in cancer care: prevalence, causes, consequences, and reduction strategies. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120(1):85–92.

Perry LM, Hoerger M, Seibert K, Gerhart JI, O’Mahony S, Duberstein PR. Financial strain and physical and emotional quality of life in breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2019;58(3):454–9.

Kent EE, Forsythe LP, Yabroff KR, Weaver KE, de Moor JS, Rodriguez JL, et al. Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer. 2013;119(20):3710–7.

Hu RY, Wang JY, Chen WL, Zhao J, Shao CH, Wang JW, et al. Stress, coping strategies and expectations among breast cancer survivors in China: a qualitative study. BMC Psychol. 2021;9(1):26.

Moghaddam Tabrizi F, Alizadeh S. Family intervention based on the FOCUS Program effects on Cancer Coping in Iranian breast Cancer patients: a Randomized Control Trial. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19(6):1523–8.

PubMed Google Scholar

Sebri V, Pravettoni G. Tailored psychological interventions to manage body image: an Opinion study on breast Cancer survivors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20(4).

Tait RC, Zoberi K, Ferguson M, Levenhagen K, Luebbert RA, Rowland K, et al. Persistent Post-mastectomy Pain: risk factors and current approaches to treatment. J Pain. 2018;19(12):1367–83.

Fitzgerald Jones K, Fu MR, McTernan ML, Ko E, Yazicioglu S, Axelrod D, et al. Lymphatic Pain in breast Cancer survivors. Lymphat Res Biol. 2022;20(5):525–32.

Schmidt ME, Chang-Claude J, Vrieling A, Heinz J, Flesch-Janys D, Steindorf K. Fatigue and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: temporal courses and long-term pattern. J Cancer Surviv. 2012;6(1):11–9.

Neil SE, Klika RJ, Garland SJ, McKenzie DC, Campbell KL. Cardiorespiratory and neuromuscular deconditioning in fatigued and non-fatigued breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(3):873–81.

Harris PF, Remington PL, Trentham-Dietz A, Allen CI, Newcomb PA. Prevalence and treatment of menopausal symptoms among breast cancer survivors. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;23(6):501–9.

Thewes B, Lebel S, Seguin Leclair C, Butow P. A qualitative exploration of fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) amongst Australian and Canadian breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(5):2269–76.

Autade YCG. Assess the prevalence for needs of breast cancer survivors’ in the oncology ward at a selected tertiary care hospital. JPRI. 2021;1(33):1–12.

Carrera PM, Kantarjian HM, Blinder VS. The financial burden and distress of patients with cancer: understanding and stepping-up action on the financial toxicity of cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(2):153–65.

Barthakur MS, Sharma MP, Chaturvedi SK, Manjunath SK. Experiences of breast Cancer survivors with Oncology Settings in Urban India: qualitative findings. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2016;7(4):392–6.

Coughlin SS, Ayyala DN, Tingen MS, Cortes JE. Financial distress among breast cancer survivors. Curr Cancer Rep. 2020;2(1):48–53.

Knight TG, Deal AM, Dusetzina SB, Muss HB, Choi SK, Bensen JT et al. Financial toxicity in adults with Cancer: adverse outcomes and noncompliance. J Oncol Pract. 2018:Jop1800120.

Nipp RD, Shui AM, Perez GK, Kirchhoff AC, Peppercorn JM, Moy B, et al. Patterns in Health Care Access and Affordability among Cancer survivors during implementation of the Affordable Care Act. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(6):791–7.

Lee S, Chen L, Ma GX, Fang CY, Oh Y, Scully L. Challenges and needs of Chinese and Korean American breast Cancer survivors: In-Depth interviews. N Am J Med Sci (Boston). 2013;6(1):1–8.

Shaw MD, Coggin C. Using a Delphi technique to determine the needs of African American breast cancer survivors. Health Promot Pract. 2008;9(1):34–44.

Wilson SE, Andersen MR, Meischke H. Meeting the needs of rural breast cancer survivors: what still needs to be done? J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9(6):667–77.

Moradi NAF, Rahmani AZV. Effects of husband’s education on meting supportive care needs of breast cancer patients: a clinical trial. Avicenna-J-Nurs-Midwifery-Care. 2013;21(3):40–50.

Arora NK, Finney Rutten LJ, Gustafson DH, Moser R, Hawkins RP. Perceived helpfulness and impact of social support provided by family, friends, and health care providers to women newly diagnosed with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2007;16(5):474–86.

Namkoong K, Shah DV, Gustafson DH. Offline Social relationships and Online Cancer Communication: effects of Social and Family Support on Online Social Network Building. Health Commun. 2017;32(11):1422–9.

Liao MN, Chen SC, Chen SC, Lin YC, Hsu YH, Hung HC, et al. Changes and predictors of unmet supportive care needs in Taiwanese women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2012;39(5):E380–9.

Zebrack B. Information and service needs for young adult cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17(4):349–57.

Winzelberg AJ, Classen C, Alpers GW, Roberts H, Koopman C, Adams RE, et al. Evaluation of an internet support group for women with primary breast cancer. Cancer: Interdisciplinary International Journal of the American Cancer Society. 2003;97(5):1164–73.

Germino BB, Mishel MH, Crandell J, Porter L, Blyler D, Jenerette C, et al. Outcomes of an uncertainty management intervention in younger African American and caucasian breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2013;40(1):82–92.

Bu X, Jin C, Fan R, Cheng ASK, Ng PHF, Xia Y, et al. Unmet needs of 1210 Chinese breast cancer survivors and associated factors: a multicentre cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):135.

Galiano-Castillo N, Cantarero‐Villanueva I, Fernández‐Lao C, Ariza‐García A, Díaz‐Rodríguez L, Del‐Moral‐Ávila R, et al. Telehealth system: a randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact of an internet‐based exercise intervention on quality of life, pain, muscle strength, and fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2016;122(20):3166–74.

Lin Y, Wu C, He C, Yan J, Chen Y, Gao L, et al. Effectiveness of three exercise programs and intensive follow-up in improving quality of life, pain, and lymphedema among breast cancer survivors: a randomized, controlled 6-month trial. Support Care Cancer. 2022;31(1):9.

Bandani-Susan B, Montazeri A, Haghighizadeh MH, Araban M. The effect of mobile health educational intervention on body image and fatigue in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Ir J Med Sci. 2022;191(4):1599–605.

Wei Y, Zheng P, Deng H, Wang X, Li X, Fu H. Design features for improving Mobile Health intervention user Engagement: systematic review and thematic analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(12):e21687.

Hodgkinson K, Butow P, Hunt GE, Pendlebury S, Hobbs KM, Wain G. Breast cancer survivors’ supportive care needs 2–10 years after diagnosis. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(5):515–23.

Beatty L, Oxlad M, Koczwara B, Wade TD. The psychosocial concerns and needs of women recently diagnosed with breast cancer: a qualitative study of patient, nurse and volunteer perspectives. Health Expect. 2008;11(4):331–42.

Torres E, Dixon C, Richman AR. Understanding the breast Cancer Experience of survivors: a qualitative study of African American Women in Rural Eastern North Carolina. J Cancer Educ. 2016;31(1):198–206.

Brennan ME, Butow P, Spillane AJ, Boyle F. Patient-reported quality of life, unmet needs and care coordination outcomes: moving toward targeted breast cancer survivorship care planning. Asia‐Pacific J Clin Oncol. 2016;12(2):e323–e31.

Simard S, Thewes B, Humphris G, Dixon M, Hayden C, Mireskandari S, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):300–22.

Crist JV, Grunfeld EA. Factors reported to influence fear of recurrence in cancer patients: a systematic review. Psychooncology. 2013;22(5):978–86.

Ellegaard MB, Grau C, Zachariae R, Bonde Jensen A. Fear of cancer recurrence and unmet needs among breast cancer survivors in the first five years. A cross-sectional study. Acta Oncol. 2017;56(2):314–20.

Fang SY, Fetzer SJ, Lee KT, Kuo YL. Fear of recurrence as a predictor of Care needs for long-term breast Cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2018;41(1):69–76.

Wells KJ, Drizin JH, Ustjanauskas AE, Vázquez-Otero C, Pan-Weisz TM, Ung D, et al. The psychosocial needs of underserved breast cancer survivors and perspectives of their clinicians and support providers. Support Care Cancer. 2022;30:105–16.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Not funded.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Student Research Committee, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, IR, Iran

Rahimeh Khajoei

Radiation Oncology Department, School of Medicine, Imam Hossein Hospital, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Payam Azadeh

Department of Medical Surgical Nursing, School of Nursing and Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, IR, Iran

Sima ZohariAnboohi & Mahnaz Ilkhani

Nursing and Midwifery Care Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran

Fatemah Heshmati Nabavi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

R.K. and M.I. conceived and designed the study. R.K. conducted and transcribed interviews, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. M.I., S.Z., P.A. and F.H. assisted in the analysis and interpretation of data, and in the revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mahnaz Ilkhani .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran with code IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1402.005. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Khajoei, R., Azadeh, P., ZohariAnboohi, S. et al. Breast cancer survivorship needs: a qualitative study. BMC Cancer 24 , 96 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-11834-5

Download citation

Received : 16 September 2023

Accepted : 03 January 2024

Published : 17 January 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-11834-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Breast cancer

- Survivorship

ISSN: 1471-2407

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Open access

- Published: 19 May 2020

The mediating effect of social support on uncertainty in illness and quality of life of female cancer survivors: a cross-sectional study

- Insook Lee ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6090-7999 1 &

- Changseung Park 2

Health and Quality of Life Outcomes volume 18 , Article number: 143 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

2971 Accesses

20 Citations

Metrics details

Cancer survivors have been defined as those living more than 5 years after cancer treatment with no signs of recurrence or further growth; however, the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship of the United States defined cancer survivors as those undergoing treatment after being diagnosed with cancer or those considered to be fully cured. The National Cancer Institute of the United States established the Office of Cancer Survivorship, with the American Society of Clinical Oncology including “patient and survivor management” as its 2006 annual objective [ 1 ], indicating the importance of cancer survivor management as a major agenda item.

Typically, breast and thyroid cancer diagnoses occur among women in their 40s and 50s, and patients who receive treatment have high survival rates. The majority of breast and thyroid cancer survivors return to their daily lives within a relatively short timeframe [ 2 ], making quality of life after treatment and important factor in cancer treatment [ 3 , 4 , 5 ].

Cancer survivors have reported experiencing a variety of physical difficulties during or after treatment, including fatigue, pain, loss of energy, sleeping disorders, and constipation [ 6 , 7 ]. They also have psychological concerns, such as fear of the cancer spreading, concerns about treatment results, and uncertainty about the future [ 8 ], as well as financial difficulties, issues with their sex lives, decreased body image, difficulties in interpersonal relationships, role disorders, and difficulty returning to work [ 7 ]. Thus, cancer patients require a diverse range of healthcare services, plus emotional and socioeconomic support, with an international study of the quality of life and symptoms of cancer survivors reporting that the quality of life among Asian patients to be the lowest of those than other country [ 6 ]. Survivors of breast cancer have reported low quality of life after treatment [ 9 , 10 ], which is influenced by emotional and psychological factors such as uncertainty, body image, lack of self-respect, and depression [ 9 , 10 , 11 ], as well as social factors including social, family, and spouse support [ 10 , 11 ].

Uncertainty among women diagnosed with malignant illnesses was found to be higher than that among women with a lump in the breast [ 12 ]. Uncertainty among breast cancer patients continues for a long period because of the fear of recurrence [ 13 ] and reduced quality of life [ 11 ]. Similarly, thyroid cancer survivors also show higher levels of fatigue, depression, and anxiety compared to those with no experience of cancer [ 14 , 15 , 16 ].

Social support is a complex and multidimensional concept that is characterized by mutual benefits that include social, psychological, and material support provided by the social support network [ 17 ]. In other words, social support means help provided by social relationships such as family, friends, and significant others, and plays an important role in directly and indirectly reducing uncertainty [ 18 , 19 ]. For cancer survivors, the need for social support is varied and depends largely on the adaptive tasks they face [ 20 ]. Social support is closely related to breast cancer survivor prognosis [ 21 ]; breast cancer survivors’ uncertainty was found to lower their quality of life, but their recognition of social support was found to improve it [ 11 ]. Recognition of social support and uncertainty played a key role in managing and maintaining quality of life. Research has shown that social support differs according to survival stage, as patients who are undergoing treatment receive active support from healthcare professionals and their family, but this support declines notably after the treatment ends [ 14 , 22 , 23 ].

With the number of cancer survivors steadily increasing, there has been an increase in the number of studies published on cancer survivors internationally [ 22 , 24 ]. In Korea in particular, there have been studies on recurrence-prevention behaviors and quality of life [ 25 ], the factors influencing quality of life [ 10 ], fatigue and quality of life [ 26 ], distress and quality of life [ 27 ], and symptoms and quality of life among breast cancer survivors [ 8 ]. Most of these studies focused on breast cancer survivors, but few studies focus on overall quality of life and the related influential factors. Few studies have analyzed the relationships between uncertainty in illness, quality of life, and social support among female breast and thyroid cancer survivors.

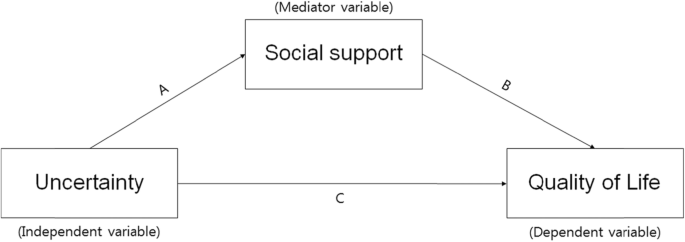

This study aimed to identify the relationships among uncertainty in illness, social support, and quality of life in female cancer survivors, and to verify the mediating role of social support, in the relationship between uncertainty in illness and quality of life. Social support may act as a generative mechanism influencing how uncertainty in illness, the predictor variable, affects quality of life, the outcome variable (Fig. 1 ) [ 28 ]. Therefore, this study will provide foundational data for devising practical and helpful intervention strategies to raise the quality of life of cancer survivors.

The theoretical research model showing the influence of uncertainty on quality of life and the mediating effect of social support

Participants

Participants were selected using convenience sampling of female cancer patients who were being treated by specialists in breast endocrinology at general hospitals located in J City of Korea. Among the 189 women (138 thyroid and 50 breast cancer patients) who agreed to participate, 156 surveys were collected (response rate: 82.5%). The final sample including 148 participants after excluding eight insincere responses. The data collection period was from April 21 to June 30, 2014. The completion of data collection through the mailed-in copies of surveys occurred on October 15, 2014. Participants were asked to complete the survey, put it in an opaque envelope, and seal it before returning it to the researchers. In cases in which on-site survey completion was difficult, participants were able to complete the survey at home and returned it by mail to the researcher.

The necessary sample size for the multiple regression analysis was confirmed utilizing G*power ver. 3.1.9 with a significance level (α) of .05; power of .80; effect size (f 2 ) of .15 (representing a medium effect size in the multiple regression analysis); and 13 independent variables (age, marital status, religion, level of education, occupation, satisfaction with economic status, smoking, drinking, diagnosis name, clinical stage of cancer, time passed since the end of treatment, uncertainty, and social support). The minimum sample size was determined to be 131. Since a maximum dropout rate of 40% was expected, information was collected from a total of 189 participants who fit the following inclusion criteria: 1) a diagnosis of cancer and no cognitive limitations; 2) the ability to understand and complete the survey in Korean; and 3) an understanding of the purpose of the study and consenting to participate. The exclusion criteria were those suffering from a mental illness, those with difficulties in communication, and those who did not wish to participate in the study.

Uncertainty in illness

Uncertainty occurs when an appropriate subjective interpretation of an illness or event is not formed. This study measured uncertainty using Mishel’s Uncertainty in Illness Scale (MUIS), which is composed of 33 items concerning uncertainty in illness. Mishel [ 19 ] originally developed the scale, and it has been translated into Korean by Lee [ 28 ]. The MUIS is a self-administered survey, with items scored on a 5-point scale from 5 ( strongly agree ) to 1 ( strongly disagree ). Positive items were measured backward, so that total scores ranged from 33 to 165. Higher scores indicated higher rates of uncertainty. The Cronbach’s α for the original 33-item tool was .91–.93; the Cronbach’s α for the tool used in the study of Korean breast cancer patients [ 29 ] was .83. In this study, the Cronbach’s α for the uncertainty scale was .88.

Social support

Social support was measured using Zimet et al.’s [ 30 ] Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS). This 12-item measure is scored on a 7-point, Likert-type scale, and assessed the three dimensions of family, friends, and significant others. Its sub-domains are composed of four items. Overall social support scores are calculated by summing the scores for each item, with higher scores indicating higher levels of social support. At the time of development, the Cronbach’s α reliability was .91; Cronbach’s α for each subscale ranged from .90–.95. In this study, the Cronbach’s α of the social support scale was .95.

Quality of life

Quality of life was measured using a standardized tool that was translated into the Korean and verified validity of the Korean version of the EORTC QLQ-C30, which was developed through a process of international joint study from multiple countries, and it is the most widely used standardized tool to measure the quality of life of cancer patients. This tool is composed of three subdomains and 30 items. It includes two items on overall quality of life and five functional domains (i.e., physical, role, cognitive, emotional, and social functions) that include 15 items; three symptom domains (i.e., fatigue, pain, nausea/vomiting) that include seven items; and one item for each of the symptoms commonly reported by cancer patients (i.e., difficulties in breathing, loss of appetite, sleeping disorders, constipation, diarrhea, and financial hardship) [ 31 ]. The EORTC QLQ-C30 is converted into a score ranging between 0 and 100 points [ 31 ]; higher overall quality of life scores, higher functional domain scores, and lower symptom domain scores indicate higher quality of life. Moreover, overall quality of life can be understood as a measurement of comprehensive quality of life [ 31 ]. This study assess quality of life using the overall quality of life score. At the time of development, Cronbach’s α was .65–.73; the Cronbach’s α for the overall quality of life score in this study was .853.

Ethical considerations

This study was conducted after receiving approval of the research protocol from the Institutional Review Board (Approved number: 2014-L02–01). The purpose and method of the research was explained directly to participants by a trained research assistant. The participants then signed an informed consent form that stated the survey would be used for the purposes of the study only, and that their confidentiality would be safeguarded. The subjects who agreed to participate in the survey received a small amount of goods worth of KRW 3000, but there were no factors that could interfere with the answers in the survey.

Data analysis

The collected data were coded and analyzed using SPSS software (version 24.0; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) at .05 significance level. The analysis excluded missing data values. The general characteristics, illness-related characteristics, uncertainty, social support, and quality of life were measured using frequency, percentages, means, and standard deviations. The differences in uncertainty, social support, and quality of life in accordance with general and illness-related characteristics were analyzed using independent t -tests and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Tukey’s post-hoc analysis was used for independent variables of more than three groups to identify which group contained the differences. Pearson’s correlation coefficient was calculated to identify correlations between uncertainty, social support, and quality of life. Multiple regression (stepwise method) was used to test the influence of uncertainty on social support and quality of life. To verify the mediating effects of social support in the relationship between uncertainty and quality of life, simple, and hierarchical multiple regression analyses were conducted as per the method proposed by Baron and Kenny [ 30 ]. The significance of the mediating effects of social support was verified using the Sobel test.

Demographic characteristics of subjects

The general characteristics of the female cancer survivors in this study indicated that their average age was 51.87 ( SD = 11.78) years, with the largest proportion (33.3%) of the population being in their 50s, followed by those in their 40s (30.1%), 60s and over (24.4%), and below 30 (12.2%). Most participants (76.2%) were married; 61.9% practiced a religion, and 66.7% had a high school education or below; 56.2% had jobs; 17.8% had lost their jobs as a result of their cancer diagnosis and treatment, and 73.1% indicated that their satisfaction with their financial status was average. They had an average of 2.26 ( SD = 1.19) children; 94.4% were non-smokers; 64.1% were non-drinkers; 29.1% of the subjects had breast cancer and 70.9% had thyroid cancer; 53.8% of the cancers were early stage, and 46.2% were advanced. The duration after cancer treatment averaged 17.64 ( SD = 31.30) months, with 70.3% reporting a duration of less than a year since they ended their treatment (Table 1 ).

Uncertainty in illness, social support, and quality of life

Average scores of uncertainty in illness, social support, and quality of life are given in Table 2 . The average uncertainty in illness score was 83.06 ( SD = 15.29; range: 44–127 points), and the average quality of life score was 66.90 ( SD = 20.32; range: 0–100 points). Average social support score was 62.62 ( SD = 17.09; range: 12–84 points), with family support being the highest (mean = 21.84, SD = 6.58), followed by support from significant others (mean = 21.28, SD = 5.93) and friends (mean = 19.45, SD = 6.70).

Differences in uncertainty in illness, social support, and quality of life according to general and illness-related characteristics

The results of the analysis of differences in uncertainty in illness, social support, and quality of life according to general and illness-related characteristics are given in Tables 3 and 4 . There were significant differences in uncertainty in illness by educational level ( t = 4.048, p < .001), satisfaction with financial status ( F = 3.760, p = .027), and smoking ( t = 2.195, p = .030). Uncertainty in illness was higher for subjects with less than a high school education, compared to those who had a university degree or higher, when they were dissatisfied with their financial status. Likewise, it was higher for smokers, compared to non-smokers.

Social support had statistically significant differences given satisfaction with financial status ( F = 5.151, p = .007) and duration since cancer treatment completion ( F = 4.292, p = .015). Social support was higher for subjects with average financial status satisfaction, and for subjects for whom it had been less than a year, or between 1 to 5 years, since they completed cancer treatment.

Quality of life significantly differed according to financial status satisfaction ( F = 6.648, p = .002). Participants had higher quality of life when they had high or average financial status satisfaction compared to dissatisfaction.

Correlation between uncertainty in illness, social support, and quality of life

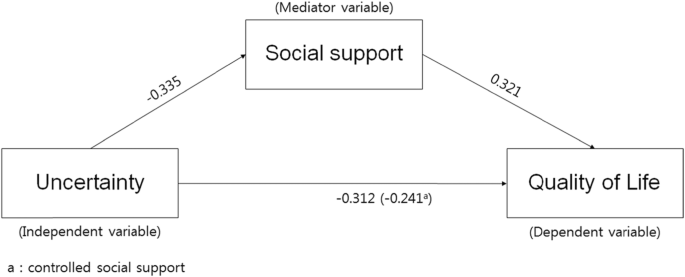

The results of the correlation analyses indicated that uncertainty in illness had a significant negative correlation with social support ( r = −.335, p < .001) and quality of life ( r = −.312, p < .001); social support had a significant positive correlation with quality of life ( r = .321, p < .001). Correlations between the sub-factors of social support and quality of life indicate that there were significant positive correlations between quality of life and support from significant others ( r = .315, p < .001), friends ( r = .284, p = .001), and family ( r = .265, p = .001). Uncertainty and support from significant others ( r = −.326, p = .001), friends ( r = −.294, p = .002), and family ( r = −.244, p = .010) showed significant negative correlations; particularly, the highest correlation was between support from significant others and uncertainty (Table 5 ).

Mediating effect of social support

Four stages of regression analysis were conducted to verify whether social support had mediating effects in the process by which uncertainty in illness influenced quality of life. Prior to verifying the mediating effects of social support, this study examined the multicollinearity between variables. The residual limit was between 0.8–1.0, which is higher than 0.1; and the value of the variance inflation factor was between 1.0–1.2, which was lower than 10, indicating no issues with multicollinearity. Moreover, the Durbin-Watson test, which is the test of independence of residual error, indicated d = 1.903–1.944, which was close to two and met the independence condition, representing no issues with self-correlation.

Using the hierarchy regression, this confirmed the partial mediating effects of social support in the process of uncertainty influencing quality of life (Table 6 , Fig. 2 ). The first regression analysis indicated that the independent variable (uncertainty) had a statistically significant influence on the mediator variable (social support; β = − 0.335, p < .001), and the explanatory power for social support was 10.4%. The second stage regression analysis indicated that the mediator variable (social support) had a significant influence on the dependent variable (quality of life; β = 0.321, p < .001), and the explanatory power for quality of life was 9.7%. The third stage regression analysis indicated that the independent variable (uncertainty) had a significant influence on the dependent variable (quality of life; β = − 0.312, p = .001) with an explanatory power of 8.9%. At the fourth stage, this study aimed to test the influence of the independent variable (uncertainty) on the dependent variable (quality of life) with social support as the mediator variable. The results indicated that uncertainty (β = − 0.241, p = .014) and social support (β = 0.213, p = .030) were significant predictors of quality of life. When social support was set as the mediator variable, uncertainty was found to have a significant influence on quality of life; the unstandardized regression coefficient reduced from − 0.396 to − 0.398, indicating a partial mediation of social support. The explanatory power of these variables in terms of quality of life was 12.1%. This study executed the Sobel test to verify the significance of the mediating effects of social support, confirming that they were significant in the relationship between uncertainty and quality of life.

Model showing the influence of uncertainty on quality of life and the mediating effect of social support

Mullen divided the stages of cancer survival into three major classifications [ 32 , 33 ]. First is the acute stage, which marks the period after the cancer diagnosis. Second is the extended stage, in which the active treatment of cancer has ended and the patient is placed under tracking observation or engages in intermittent treatment. During this period, the majority of cancer survivors experience uncertainty toward their cancer treatment and fear recurrence, and they may experience physical and psychological issues. Lastly, the permanent stage marks a period in which the cancer is thought to be fully cured, or the patient is expected to survive long term, with a low risk of recurrence.

The participants in this study averaged a score of 66.90 for quality of life. As it is difficult to draw a direct comparison given the lack of research utilizing this measure, in converting quality of life into a scale of 100 points, this study’s results were similar to those found previously regarding post-hoc management following breast cancer treatment for 200 women [ 8 , 10 ]. However, a study covering regionally based, adult female breast cancer survivors between 6 months and 2 years after anti-cancer treatment completion reported lower scores (e.g., 60.13 points) compared to this study [ 27 ]. Likewise, a study of breast cancer survivors with completed surgeries and assistive treatments, breast cancer survivors whose treatment had ended had scores of 53.4 and 56.66 points, respectively for breast cancer survivors with completed surgeries and assistive treatments [ 25 , 26 ].

On the other hand, a report of 110 adult females with breast cancer or OB/GYN cancers [ 33 ] indicated that quality of life according to cancer survival stage was 58.7, 62.3, and 66.8 points during the acute, extended, and permanent stages, respectively. Quality of life in this study was similar to the level experienced by survivors during the permanent stage. Considering that the average time since treatment was 17.64 months, these results indicate a relatively high quality of life. While these differences cannot be accurately compared and discussed because of the lack of research covering the same variables, the majority of survivors had thyroid cancer (70.9%), and it is known that thyroid cancer has higher rates of survival. Going forward, it is important to develop interventions to improve quality of life by assessing survivors’ specific stages.

There were no significant relationships between quality of life and length of time since completing treatment. Existing research has suggested that quality of life was significantly higher for those surviving more than 5 years after cancer treatment completion [ 8 , 33 ], indicating that quality of life improves as duration of survival increases. The quality of life of these cancer survivors has been reported to improve with the passage of time [ 8 , 33 ]. Therefore, cross-sectional and longitudinal studies are required in the future to identify quality of life by survival stage and changes in quality of life over time.

On the other hand, qualitative studies of Korean female cancer survivors have indicated that the significant others and families of female cancer survivors wanted them to return to their pre-cancer lives to take care of their spouses and children, indicated the demands on female cancer survivors in Korea to fulfill their roles as wives and mothers before fully recovering from cancer [ 33 ]. Thus, customized interventions by survival stage for female cancer survivors are needed along with further research on the relationships between cultural specificity, role conflicts imposed on survivors because they are women, and their quality of life.

The uncertainty toward illness of the participants in this study was similar to existing research in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy averaged 83.08 [ 34 ] and female thyroid cancer patients [ 35 ]. On the other hand, the level of uncertainty faced by cancer patients prior to surgery averaged 81.43 in a study of cancer patients hospitalized for breast, thyroid, and bladder cancer [ 36 ], which was slightly lower than the value found in this study. This appears to be because female cancer survivors in this study were mostly in the extended stage, which comes after the active treatment of their cancer [ 32 , 33 ]. Most cancer survivors face uncertainty toward cancer treatment and fear of recurrence [ 8 , 32 , 33 ]; thus, they experience a diverse range of physical and psychological problems [ 6 , 7 ]. On the other hand, a qualitative study of 25 breast cancer survivors aged over 30 who had undergone surgery and chemotherapy as their primary treatment for breast cancer [ 37 ] indicated that quality of life following treatment for breast cancer survivors saw a coexistence of anxiety and uncertainty about recurrence. A shorter duration of time since treatment led to higher confusion in their own health management efforts and health management in general.

These results indicate that there are limitations to comparing uncertainty results given the lack of domestic studies on cancer survivors; therefore, future studies are needed to fill this gap. Moreover, it is necessary to confirm uncertainty by cancer survival stage and develop interventions to reduce the uncertainty accompanying each stage.

Uncertainty in illness was higher for those with less than a high school education, compared to those with a university education or higher, when they were dissatisfied with their financial status, and for those who were smokers. These results were similar to previous research [ 36 ], which indicated high uncertainty for participants over 60 who had a low monthly income and low level of education. Therefore, it is necessary to consider these socioeconomic factors when developing uncertainty reducing strategies such as customized information delivery and communication.