Case study method in anthropology

Karen Sykes, Anthropology.

A paraphrase of Gluckman’s thoughts on the case study captures the essence of the method:

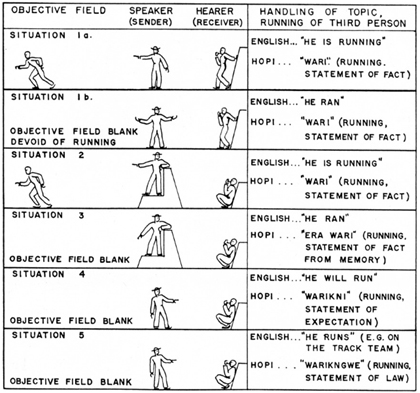

Anthropologists use ‘case’ in a slightly different way than some legal scholars or psychoanalysts, either of whom might use cases to illustrate their points or theories. Anthropologists often describe a case first, and then extract a general rule or custom from it, in the manner of inductive reasoning. Most often, the event is complex, or even a series of events, and we call these social situations, which can be analysed to show that the different conflictive perspectives on them are enjoined in the same social system (and not based in the assumption of cultural difference as a prima face condition of anthropological inquiry).

The case study, as a part of ‘situational analysis,’ is a vital approach that is used in anthropological research in the postcolonial world. In it we use the actions of individuals and groups within these situations to exhibit the morphology of a social structure, which is most often held together by conflict itself. Each case is taken as evidence of the stages in the unfolding process of social relations between specific persons and groups. When seen as such, we can dispense with the study of sentiment as accidental eruptions of emotions, or as differences of individual temperament, and bring depth to the study of society by penetrating surface tensions to understand how conflict constructs human experiences and gives shape to these as ‘social dramas’, which are the expressions of cultural life.

Experts/users at Manchester

The Case Study Method in Anthropology is used in many different research projects from ethnography of urban poverty, through studies of charismatic Christian movements, Cultural Property and in visual methods.

- Professor Caroline Moser - Caroline Moser, Professor of Urban Development and Director of GURC uses variations of the case study in her uses of the participatory urban appraisal methods to conduct research into peace processes, urban violence, as well as climate change.

- Dr Andrew Irving - Andrew Irving has used variations of the case study as social drama when examining life-events of his informants, as way to access their thoughts about immanence of death (which he calls interior knowledge).

- Professor Karen Sykes - Karen Sykes originally experimented with the use of case study method in order to understand how people came to see cultural property rights as a legal device to protect their cultural life from exploitation. Her book “Culture and Cultural Property in the New Guinea Islands Region: Seven Case Studies” was co-authored with J. Simet and S. Kamene and features the work of five female students at the University of Papua New Guinea.

Key references

Evens, T. M. S. and D. Handelman (2007) The Manchester School: Practice and ethnographic praxis in anthropology, Oxford: Berghahn. This book deals with the Case Study method as the cornerstone of all of the Manchester School methodologies.

Turner, V. (1953) Schism and Continuity in an African Society, Manchester University Press for the Rhodes Livingstone Institute. Turner’s first use of the social drama as a version of the case study method.

Mitchell, C. (1983) Case and Situation Analysis, Sociological Review, 31: 187 – 211. The definitive paper on Situational Analysis which can be compared to van Velson on the extended case method.

Van Velson, J. (1967) The Extended Case Method and Situational Analysis in Epstein, A. L., 1967, The Craft of Anthropology, London: Tavistock. This edited book collected chapters by Manchester School members on various approaches to anthropology.

Download PDF slides of the presentation ' What is a case study ... in anthropology? '

Case Study Research

- First Online: 29 September 2022

Cite this chapter

- Robert E. White ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-8045-164X 3 &

- Karyn Cooper 4

1294 Accesses

As a footnote to the previous chapter, there is such a beast known as the ethnographic case study. Ethnographic case study has found its way into this chapter rather than into the previous one because of grammatical considerations. Simply put, the “case study” part of the phrase is the noun (with “case” as an adjective defining what kind of study it is), while the “ethnographic” part of the phrase is an adjective defining the type of case study that is being conducted. As such, the case study becomes the methodology, while the ethnography part refers to a method, mode or approach relating to the development of the study.

The experiential account that we get from a case study or qualitative research of a similar vein is just so necessary. How things happen over time and the degree to which they are subject to personality and how they are only gradually perceived as tolerable or intolerable by the communities and the groups that are involved is so important. Robert Stake, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bartlett, L., & Vavrus, F. (2017). Rethinking case study research . Routledge.

Google Scholar

Bauman, Z. (2000). Liquid modernity . Polity Press.

Bhaskar, R., & Danermark, B. (2006). Metatheory, interdisciplinarity and disability research: A critical realist perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research, 8 (4), 278–297.

Article Google Scholar

Bulmer, M. (1986). The Chicago School of sociology: Institutionalization, diversity, and the rise of sociological research . University of Chicago Press.

Campbell, D. T. (1975). Degrees of freedom and the case study. Comparative Political Studies, 8 (1), 178–191.

Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1966). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research . Houghton Mifflin.

Chua, W. F. (1986). Radical developments in accounting thought. The Accounting Review, 61 (4), 601–632.

Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.). Sage.

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design . Sage.

Davey, L. (1991). The application of case study evaluations. Practical Assessment, Research, & Evaluation 2 (9) . Retrieved May 28, 2018, from http://PAREonline.net/getvn.asp?v=2&n=9

Demetriou, H. (2017). The case study. In E. Wilson (Ed.), School-based research: A guide for education students (pp. 124–138). Sage.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (2005). The Sage handbook of qualitative research . Sage.

Flyvbjerg, B. (2004). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. In C. Seale, G. Gobo, J. F. Gubrium, & D. Silverman (Eds.), Qualitative research practice (pp. 420–433). Sage.

Hamel, J., Dufour, S., & Fortin, D. (1993). Case study methods . Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Healy, M. E. (1947). Le Play’s contribution to sociology: His method. The American Catholic Sociological Review, 8 (2), 97–110.

Johansson, R. (2003). Case study methodology. [Keynote speech]. In International Conference “Methodologies in Housing Research.” Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, September 2003 (pp. 1–14).

Klonoski, R. (2013). The case for case studies: Deriving theory from evidence. Journal of Business Case Studies, 9 (31), 261–266.

McDonough, J., & McDonough, S. (1997). Research methods for English language teachers . Routledge.

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education . Jossey-Bass.

Miles, M. B. (1979). Qualitative data as an attractive nuisance: The problem of analysis. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24 (4), 590–601.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Sage.

Mills, A. J., Durepos, G. & E. Wiebe (Eds.) (2010). What is a case study? Encyclopedia of case study research, Volumes I and II. Sage.

National Film Board of Canada. (2012, April). Here at home: In search of the real cost of homelessness . [Web documentary]. Retrieved February 9, 2020, from http://athome.nfb.ca/#/athome/home

Popper, K. (2002). Conjectures and refutations: The growth of scientific knowledge . Routledge.

Ridder, H.-G. (2017). The theory contribution of case study research designs. Business Research, 10 (2), 281–305.

Rolls, G. (2005). Classic case studies in psychology . Hodder Education.

Seawright, J., & Gerring, J. (2008). Case-Selection techniques in case study research: A menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Political Research Quarterly, 61 , 294–308.

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research . Sage.

Stake, R. E. (2005). Multiple case study analysis . Guilford Press.

Swanborn, P. G. (2010). Case study research: What, why and how? Sage.

Thomas, W. I., & Znaniecki, F. (1996). The Polish peasant in Europe and America: A classic work in immigration history . University of Illinois Press.

Yin, R. K. (1981). The case study crisis: Some answers. Administrative Science Quarterly, 26 (1), 58–65.

Yin, R. K. (1991). Advancing rigorous methodologies : A Review of “Towards Rigor in Reviews of Multivocal Literatures….”. Review of Educational Research, 61 (3), 299–305.

Yin, R. K. (1999). Enhancing the quality of case studies in health services research. Health Services Research, 34 (5) Part II, 1209–1224.

Yin, R. K. (2012). Applications of case study research (3rd ed.). Sage.

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). Sage.

Zaretsky, E. (1996). Introduction. In W. I. Thomas & F. Znaniecki (Eds.), The Polish peasant in Europe and America: A classic work in immigration history (pp. vii–xvii). University of Illinois Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Education, St. Francis Xavier University, Antigonish, NS, Canada

Robert E. White

OISE, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Karyn Cooper

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Robert E. White .

A Case in Case Study Methodology

Christine Benedichte Meyer

Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration

Meyer, C. B. (2001). A Case in Case Study Methodology. Field Methods 13 (4), 329-352.

The purpose of this article is to provide a comprehensive view of the case study process from the researcher’s perspective, emphasizing methodological considerations. As opposed to other qualitative or quantitative research strategies, such as grounded theory or surveys, there are virtually no specific requirements guiding case research. This is both the strength and the weakness of this approach. It is a strength because it allows tailoring the design and data collection procedures to the research questions. On the other hand, this approach has resulted in many poor case studies, leaving it open to criticism, especially from the quantitative field of research. This article argues that there is a particular need in case studies to be explicit about the methodological choices one makes. This implies discussing the wide range of decisions concerned with design requirements, data collection procedures, data analysis, and validity and reliability. The approach here is to illustrate these decisions through a particular case study of two mergers in the financial industry in Norway.

In the past few years, a number of books have been published that give useful guidance in conducting qualitative studies (Gummesson 1988; Cassell & Symon 1994; Miles & Huberman 1994; Creswell 1998; Flick 1998; Rossman & Rallis 1998; Bryman & Burgess 1999; Marshall & Rossman 1999; Denzin & Lincoln 2000). One approach often mentioned is the case study (Yin 1989). Case studies are widely used in organizational studies in the social science disciplines of sociology, industrial relations, and anthropology (Hartley 1994). Such a study consists of detailed investigation of one or more organizations, or groups within organizations, with a view to providing an analysis of the context and processes involved in the phenomenon under study.

As opposed to other qualitative or quantitative research strategies, such as grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss 1967) or surveys (Nachmias & Nachmias 1981), there are virtually no specific requirements guiding case research. Yin (1989) and Eisenhardt (1989) give useful insights into the case study as a research strategy, but leave most of the design decisions on the table. This is both the strength and the weakness of this approach. It is a strength because it allows tailoring the design and data collection procedures to the research questions. On the other hand, this approach has resulted in many poor case studies, leaving it open to criticism, especially from the quantitative field of research (Cook and Campbell 1979). The fact that the case study is a rather loose design implies that there are a number of choices that need to be addressed in a principled way.

Although case studies have become a common research strategy, the scope of methodology sections in articles published in journals is far too limited to give the readers a detailed and comprehensive view of the decisions taken in the particular studies, and, given the format of methodology sections, will remain so. The few books (Yin 1989, 1993; Hamel, Dufour, & Fortin 1993; Stake 1995) and book chapters on case studies (Hartley 1994; Silverman 2000) are, on the other hand, mainly normative and span a broad range of different kinds of case studies. One exception is Pettigrew (1990, 1992), who places the case study in the context of a research tradition (the Warwick process research).

Given the contextual nature of the case study and its strength in addressing contemporary phenomena in real-life contexts, I believe that there is a need for articles that provide a comprehensive overview of the case study process from the researcher’s perspective, emphasizing methodological considerations. This implies addressing the whole range of choices concerning specific design requirements, data collection procedures, data analysis, and validity and reliability.

WHY A CASE STUDY?

Case studies are tailor-made for exploring new processes or behaviors or ones that are little understood (Hartley 1994). Hence, the approach is particularly useful for responding to how and why questions about a contemporary set of events (Leonard-Barton 1990). Moreover, researchers have argued that certain kinds of information can be difficult or even impossible to tackle by means other than qualitative approaches such as the case study (Sykes 1990). Gummesson (1988:76) argues that an important advantage of case study research is the opportunity for a holistic view of the process: “The detailed observations entailed in the case study method enable us to study many different aspects, examine them in relation to each other, view the process within its total environment and also use the researchers’ capacity for ‘verstehen.’ ”

The contextual nature of the case study is illustrated in Yin’s (1993:59) definition of a case study as an empirical inquiry that “investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context and addresses a situation in which the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident.”

The key difference between the case study and other qualitative designs such as grounded theory and ethnography (Glaser & Strauss 1967; Strauss & Corbin 1990; Gioia & Chittipeddi 1991) is that the case study is open to the use of theory or conceptual categories that guide the research and analysis of data. In contrast, grounded theory or ethnography presupposes that theoretical perspectives are grounded in and emerge from firsthand data. Hartley (1994) argues that without a theoretical framework, the researcher is in severe danger of providing description without meaning. Gummesson (1988) says that a lack of preunderstanding will cause the researcher to spend considerable time gathering basic information. This preunderstanding may arise from general knowledge such as theories, models, and concepts or from specific knowledge of institutional conditions and social patterns. According to Gummesson, the key is not to require researchers to have split but dual personalities: “Those who are able to balance on a razor’s edge using their pre-understanding without being its slave” (p. 58).

DESCRIPTION OF THE ILLUSTRATIVE STUDY

The study that will be used for illustrative purposes is a comparative and longitudinal case study of organizational integration in mergers and acquisitions taking place in Norway. The study had two purposes: (1) to identify contextual factors and features of integration that facilitated or impeded organizational integration, and (2) to study how the three dimensions of organizational integration (integration of tasks, unification of power, and integration of cultures and identities) interrelated and evolved over time. Examples of contextual factors were relative power, degree of friendliness, and economic climate. Integration features included factors such as participation, communication, and allocation of positions and functions.

Mergers and acquisitions are inherently complex. Researchers in the field have suggested that managers continuously underestimate the task of integrating the merging organizations in the postintegration process (Haspeslaph & Jemison 1991). The process of organizational integration can lead to sharp interorganizational conflict as the different top management styles, organizational and work unit cultures, systems, and other aspects of organizational life come into contact (Blake & Mounton 1985; Schweiger & Walsh 1990; Cartwright & Cooper 1993). Furthermore, cultural change in mergers and acquisitions is compounded by additional uncertainties, ambiguities, and stress inherent in the combination process (Buono & Bowditch 1989).

I focused on two combinations: one merger and one acquisition. The first case was a merger between two major Norwegian banks, Bergen Bank and DnC (to be named DnB), that started in the late 1980s. The second case was a study of a major acquisition in the insurance industry (i.e., Gjensidige’s acquisition of Forenede), that started in the early 1990s. Both combinations aimed to realize operational synergies though merging the two organizations into one entity. This implied disruption of organizational boundaries and threat to the existing power distribution and organizational cultures.

The study of integration processes in mergers and acquisitions illustrates the need to find a design that opens for exploration of sensitive issues such as power struggles between the two merging organizations. Furthermore, the inherent complexity in the integration process, involving integration of tasks, unification of power, and cultural integration stressed the need for in-depth study of the phenomenon over time. To understand the cultural integration process, the design also had to be linked to the past history of the two organizations.

DESIGN DECISIONS

In the introduction, I stressed that a case is a rather loose design that requires that a number of design choices be made. In this section, I go through the most important choices I faced in the study of organizational integration in mergers and acquisitions. These include: (1) selection of cases; (2) sampling time; (3) choosing business areas, divisions, and sites; and (4) selection of and choices regarding data collection procedures, interviews, documents, and observation.

Selection of Cases

There are several choices involved in selecting cases. First, there is the question of how many cases to include. Second, one must sample cases and decide on a unit of analysis. I will explore these issues subsequently.

Single or Multiple Cases

Case studies can involve single or multiple cases. The problem of single cases is limitations in generalizability and several information-processing biases (Eisenhardt 1989).

One way to respond to these biases is by applying a multi-case approach (Leonard-Barton 1990). Multiple cases augment external validity and help guard against observer biases. Moreover, multi-case sampling adds confidence to findings. By looking at a range of similar and contrasting cases, we can understand a single-case finding, grounding it by specifying how and where and, if possible, why it behaves as it does. (Miles & Huberman 1994)

Given these limitations of the single case study, it is desirable to include more than one case study in the study. However, the desire for depth and a pluralist perspective and tracking the cases over time implies that the number of cases must be fairly few. I chose two cases, which clearly does not support generalizability any more than does one case, but allows for comparison and contrast between the cases as well as a deeper and richer look at each case.

Originally, I planned to include a third case in the study. Due to changes in management during the initial integration process, my access to the case was limited and I left this case entirely. However, a positive side effect was that it allowed a deeper investigation of the two original cases and in hindsight turned out to be a good decision.

Sampling Cases

The logic of sampling cases is fundamentally different from statistical sampling. The logic in case studies involves theoretical sampling, in which the goal is to choose cases that are likely to replicate or extend the emergent theory or to fill theoretical categories and provide examples for polar types (Eisenhardt 1989). Hence, whereas quantitative sampling concerns itself with representativeness, qualitative sampling seeks information richness and selects the cases purposefully rather than randomly (Crabtree and Miller 1992).

The choice of cases was guided by George (1979) and Pettigrew’s (1990) recommendations. The aim was to find cases that matched the three dimensions in the dependent variable and provided variation in the contextual factors, thus representing polar cases.

To match the choice of outcome variable, organizational integration, I chose cases in which the purpose was to fully consolidate the merging parties’ operations. A full consolidation would imply considerable disruption in the organizational boundaries and would be expected to affect the task-related, political, and cultural features of the organizations. As for the contextual factors, the two cases varied in contextual factors such as relative power, friendliness, and economic climate. The DnB merger was a friendly combination between two equal partners in an unfriendly economic climate. Gjensidige’s acquisition of Forenede was, in contrast, an unfriendly and unbalanced acquisition in a friendly economic climate.

Unit of Analysis

Another way to respond to researchers’ and respondents’ biases is to have more than one unit of analysis in each case (Yin 1993). This implies that, in addition to developing contrasts between the cases, researchers can focus on contrasts within the cases (Hartley 1994). In case studies, there is a choice of a holistic or embedded design (Yin 1989). A holistic design examines the global nature of the phenomenon, whereas an embedded design also pays attention to subunit(s).

I used an embedded design to analyze the cases (i.e., within each case, I also gave attention to subunits and subprocesses). In both cases, I compared the combination processes in the various divisions and local networks. Moreover, I compared three distinct change processes in DnB: before the merger, during the initial combination, and two years after the merger. The overall and most important unit of analysis in the two cases was, however, the integration process.

Sampling Time

According to Pettigrew (1990), time sets a reference for what changes can be seen and how those changes are explained. When conducting a case study, there are several important issues to decide when sampling time. The first regards how many times data should be collected, while the second concerns when to enter the organizations. There is also a need to decide whether to collect data on a continuous basis or in distinct periods.

Number of data collections. I studied the process by collecting real time and retrospective data at two points in time, with one-and-a-half- and two-year intervals in the two cases. Collecting data twice had some interesting implications for the interpretations of the data. During the first data collection in the DnB study, for example, I collected retrospective data about the premerger and initial combination phase and real-time data about the second step in the combination process.

Although I gained a picture of how the employees experienced the second stage of the combination process, it was too early to assess the effects of this process at that stage. I entered the organization two years later and found interesting effects that I had not anticipated the first time. Moreover, it was interesting to observe how people’s attitudes toward the merger processes changed over time to be more positive and less emotional.

When to enter the organizations. It would be desirable to have had the opportunity to collect data in the precombination processes. However, researchers are rarely given access in this period due to secrecy. The emphasis in this study was to focus on the postcombination process. As such, the precombination events were classified as contextual factors. This implied that it was most important to collect real-time data after the parties had been given government approval to merge or acquire. What would have been desirable was to gain access earlier in the postcombination process. This was not possible because access had to be negotiated. Due to the change of CEO in the middle of the merger process and the need for renegotiating access, this took longer than expected.

Regarding the second case, I was restricted by the time frame of the study. In essence, I had to choose between entering the combination process as soon as governmental approval was given, or entering the organization at a later stage. In light of the previous studies in the field that have failed to go beyond the initial two years, and given the need to collect data about the cultural integration process, I chose the latter strategy. And I decided to enter the organizations at two distinct periods of time rather than on a continuous basis.

There were several reasons for this approach, some methodological and some practical. First, data collection on a continuous basis would have required use of extensive observation that I didn’t have access to, and getting access to two data collections in DnB was difficult in itself. Second, I had a stay abroad between the first and second data collection in Gjensidige. Collecting data on a continuous basis would probably have allowed for better mapping of the ongoing integration process, but the contrasts between the two different stages in the integration process that I wanted to elaborate would probably be more difficult to detect. In Table 1 I have listed the periods of time in which I collected data in the two combinations.

Sampling Business Areas, Divisions, and Sites

Even when the cases for a study have been chosen, it is often necessary to make further choices within each case to make the cases researchable. The most important criteria that set the boundaries for the study are importance or criticality, relevance, and representativeness. At the time of the data collection, my criteria for making these decisions were not as conscious as they may appear here. Rather, being restricted by time and my own capacity as a researcher, I had to limit the sites and act instinctively. In both cases, I decided to concentrate on the core businesses (criticality criterion) and left out the business units that were only mildly affected by the integration process (relevance criterion). In the choice of regional offices, I used the representativeness criterion as the number of offices widely exceeded the number of sites possible to study. In making these choices, I relied on key informants in the organizations.

SELECTION OF DATA COLLECTION PROCEDURES

The choice of data collection procedures should be guided by the research question and the choice of design. The case study approach typically combines data collection methods such as archives, interviews, questionnaires, and observations (Yin 1989). This triangulated methodology provides stronger substantiation of constructs and hypotheses. However, the choice of data collection methods is also subject to constraints in time, financial resources, and access.

I chose a combination of interviews, archives, and observation, with main emphasis on the first two. Conducting a survey was inappropriate due to the lack of established concepts and indicators. The reason for limited observation, on the other hand, was due to problems in obtaining access early in the study and time and resource constraints. In addition to choosing among several different data collection methods, there are a number of choices to be made for each individual method.

When relying on interviews as the primary data collection method, the issue of building trust between the researcher and the interviewees becomes very important. I addressed this issue by several means. First, I established a procedure of how to approach the interviewees. In most cases, I called them first, then sent out a letter explaining the key features of the project and outlining the broad issues to be addressed in the interview. In this letter, the support from the institution’s top management was also communicated. In most cases, the top management’s support of the project was an important prerequisite for the respondent’s input. Some interviewees did, however, fear that their input would be open to the top management without disguising the information source. Hence, it became important to communicate how I intended to use and store the information.

To establish trust, I also actively used my preunderstanding of the context in the first case and the phenomenon in the second case. As I built up an understanding of the cases, I used this information to gain confidence. The active use of my preunderstanding did, however, pose important challenges in not revealing too much of the research hypotheses and in balancing between asking open-ended questions and appearing knowledgeable.

There are two choices involved in conducting interviews. The first concerns the sampling of interviewees. The second is that you must decide on issues such as the structure of the interviews, use of tape recorder, and involvement of other researchers.

Sampling Interviewees

Following the desire for detailed knowledge of each case and for grasping different participant’s views the aim was, in line with Pettigrew (1990), to apply a pluralist view by describing and analyzing competing versions of reality as seen by actors in the combination processes.

I used four criteria for sampling informants. First, I drew informants from populations representing multiple perspectives. The first data collection in DnB was primarily focused on the top management level. Moreover, most middle managers in the first data collection were employed at the head offices, either in Bergen or Oslo. In the second data collection, I compensated for this skew by including eight local middle managers in the sample. The difference between the number of employees interviewed in DnB and Gjensidige was primarily due to the fact that Gjensidige has three unions, whereas DnB only has one. The distribution of interviewees is outlined in Table 2 .

The second criterion was to use multiple informants. According to Glick et al. (1990), an important advantage of using multiple informants is that the validity of information provided by one informant can be checked against that provided by other informants. Moreover, the validity of the data used by the researcher can be enhanced by resolving the discrepancies among different informants’ reports. Hence, I selected multiple respondents from each perspective.

Third, I focused on key informants who were expected to be knowledgeable about the combination process. These people included top management members, managers, and employees involved in the integration project. To validate the information from these informants, I also used a fourth criterion by selecting managers and employees who had been affected by the process but who were not involved in the project groups.

Structured versus unstructured. In line with the explorative nature of the study, the goal of the interviews was to see the research topic from the perspective of the interviewee, and to understand why he or she came to have this particular perspective. To meet this goal, King (1994:15) recommends that one have “a low degree of structure imposed on the interviewer, a preponderance of open questions, a focus on specific situations and action sequences in the world of the interviewee rather than abstractions and general opinions.” In line with these recommendations, the collection of primary data in this study consists of unstructured interviews.

Using tape recorders and involving other researchers. The majority of the interviews were tape-recorded, and I could thus concentrate fully on asking questions and responding to the interviewees’ answers. In the few interviews that were not tape-recorded, most of which were conducted in the first phase of the DnB-study, two researchers were present. This was useful as we were both able to discuss the interviews later and had feedback on the role of an interviewer.

In hindsight, however, I wish that these interviews had been tape-recorded to maintain the level of accuracy and richness of data. Hence, in the next phases of data collection, I tape-recorded all interviews, with two exceptions (people who strongly opposed the use of this device). All interviews that were tape-recorded were transcribed by me in full, which gave me closeness and a good grasp of the data.

When organizations merge or make acquisitions, there are often a vast number of documents to choose from to build up an understanding of what has happened and to use in the analyses. Furthermore, when firms make acquisitions or merge, they often hire external consultants, each of whom produces more documents. Due to time constraints, it is seldom possible to collect and analyze all these documents, and thus the researcher has to make a selection.

The choice of documentation was guided by my previous experience with merger and acquisition processes and the research question. Hence, obtaining information on the postintegration process was more important than gaining access to the due-diligence analysis. As I learned about the process, I obtained more documents on specific issues. I did not, however, gain access to all the documents I asked for, and, in some cases, documents had been lost or shredded.

The documents were helpful in a number of ways. First, and most important, they were used as inputs to the interview guide and saved me time, because I did not have to ask for facts in the interviews. They were also useful for tracing the history of the organizations and statements made by key people in the organizations. Third, the documents were helpful in counteracting the biases of the interviews. A list of the documents used in writing the cases is shown in Table 3 .

Observation

The major strength of direct observation is that it is unobtrusive and does not require direct interaction with participants (Adler and Adler 1994). Observation produces rigor when it is combined with other methods. When the researcher has access to group processes, direct observation can illuminate the discrepancies between what people said in the interviews and casual conversations and what they actually do (Pettigrew 1990).

As with interviews, there are a number of choices involved in conducting observations. Although I did some observations in the study, I used interviews as the key data collection source. Discussion in this article about observations will thus be somewhat limited. Nevertheless, I faced a number of choices in conducting observations, including type of observation, when to enter, how much observation to conduct, and which groups to observe.

The are four ways in which an observer may gather data: (1) the complete participant who operates covertly, concealing any intention to observe the setting; (2) the participant-as-observer, who forms relationships and participates in activities, but makes no secret of his or her intentions to observe events; (3) the observer-as-participant, who maintains only superficial contact with the people being studied; and (4) the complete observer, who merely stands back and eavesdrops on the proceedings (Waddington 1994).

In this study, I used the second and third ways of observing. The use of the participant-as-observer mode, on which much ethnographic research is based, was rather limited in the study. There were two reasons for this. First, I had limited time available for collecting data, and in my view interviews made more effective use of this limited time than extensive participant observation. Second, people were rather reluctant to let me observe these political and sensitive processes until they knew me better and felt I could be trusted. Indeed, I was dependent on starting the data collection before having built sufficient trust to observe key groups in the integration process. Nevertheless, Gjensidige allowed me to study two employee seminars to acquaint me with the organization. Here I admitted my role as an observer but participated fully in the activities. To achieve variation, I chose two seminars representing polar groups of employees.

As observer-as-participant, I attended a top management meeting at the end of the first data collection in Gjensidige and observed the respondents during interviews and in more informal meetings, such as lunches. All these observations gave me an opportunity to validate the data from the interviews. Observing the top management group was by far the most interesting and rewarding in terms of input.

Both DnB and Gjensidige started to open up for more extensive observation when I was about to finish the data collection. By then, I had built up the trust needed to undertake this approach. Unfortunately, this came a little late for me to take advantage of it.

DATA ANALYSIS

Published studies generally describe research sites and data-collection methods, but give little space to discuss the analysis (Eisenhardt 1989). Thus, one cannot follow how a researcher arrives at the final conclusions from a large volume of field notes (Miles and Huberman 1994).

In this study, I went through the stages by which the data were reduced and analyzed. This involved establishing the chronology, coding, writing up the data according to phases and themes, introducing organizational integration into the analysis, comparing the cases, and applying the theory. I will discuss these phases accordingly.

The first step in the analysis was to establish the chronology of the cases. To do this, I used internal and external documents. I wrote the chronologies up and included appendices in the final report.

The next step was to code the data into phases and themes reflecting the contextual factors and features of integration. For the interviews, this implied marking the text with a specific phase and a theme, and grouping the paragraphs on the same theme and phase together. I followed the same procedure in organizing the documents.

I then wrote up the cases using phases and themes to structure them. Before starting to write up the cases, I scanned the information on each theme, built up the facts and filled in with perceptions and reactions that were illustrative and representative of the data.

The documents were primarily useful in establishing the facts, but they also provided me with some perceptions and reactions that were validated in the interviews. The documents used included internal letters and newsletters as well as articles from the press. The interviews were less factual, as intended, and gave me input to assess perceptions and reactions. The limited observation was useful to validate the data from the interviews. The result of this step was two descriptive cases.

To make each case more analytical, I introduced the three dimensions of organizational integration—integration of tasks, unification of power, and cultural integration—into the analysis. This helped to focus the case and to develop a framework that could be used to compare the cases. The cases were thus structured according to phases, organizational integration, and themes reflecting the factors and features in the study.

I took all these steps to become more familiar with each case as an individual entity. According to Eisenhardt (1989:540), this is a process that “allows the unique patterns of each case to emerge before the investigators push to generalise patterns across cases. In addition it gives investigators a rich familiarity with each case which, in turn, accelerates cross-case comparison.”

The comparison between the cases constituted the next step in the analysis. Here, I used the categories from the case chapters, filled in the features and factors, and compared and contrasted the findings. The idea behind cross-case searching tactics is to force investigators to go beyond initial impressions, especially through the use of structural and diverse lenses on the data. These tactics improve the likelihood of accurate and reliable theory, that is, theory with a close fit to the data (Eisenhardt 1989).

As a result, I had a number of overall themes, concepts, and relationships that had emerged from the within-case analysis and cross-case comparisons. The next step was to compare these emergent findings with theory from the organizational field of mergers and acquisitions, as well as other relevant perspectives.

This method of generalization is known as analytical generalization. In this approach, a previously developed theory is used as a template with which to compare the empirical results of the case study (Yin 1989). This comparison of emergent concepts, theory, or hypotheses with the extant literature involves asking what it is similar to, what it contradicts, and why. The key to this process is to consider a broad range of theory (Eisenhardt 1989). On the whole, linking emergent theory to existent literature enhances the internal validity, generalizability, and theoretical level of theory-building from case research.

According to Eisenhardt (1989), examining literature that conflicts with the emergent literature is important for two reasons. First, the chance of neglecting conflicting findings is reduced. Second, “conflicting results forces researchers into a more creative, frame-breaking mode of thinking than they might otherwise be able to achieve” (p. 544). Similarly, Eisenhardt (1989) claims that literature discussing similar findings is important because it ties together underlying similarities in phenomena not normally associated with each other. The result is often a theory with a stronger internal validity, wider generalizability, and a higher conceptual level.

The analytical generalization in the study included exploring and developing the concepts and examining the relationships between the constructs. In carrying out this analytical generalization, I acted on Eisenhardt’s (1989) recommendation to use a broad range of theory. First, I compared and contrasted the findings with the organizational stream on mergers and acquisition literature. Then I discussed other relevant literatures, including strategic change, power and politics, social justice, and social identity theory to explore how these perspectives could contribute to the understanding of the findings. Finally, I discussed the findings that could not be explained either by the merger and acquisition literature or the four theoretical perspectives.

In every scientific study, questions are raised about whether the study is valid and reliable. The issues of validity and reliability in case studies are just as important as for more deductive designs, but the application is fundamentally different.

VALIDITY AND RELIABILITY

The problems of validity in qualitative studies are related to the fact that most qualitative researchers work alone in the field, they focus on the findings rather than describe how the results were reached, and they are limited in processing information (Miles and Huberman 1994).

Researchers writing about qualitative methods have questioned whether the same criteria can be used for qualitative and quantitative studies (Kirk & Miller 1986; Sykes 1990; Maxwell 1992). The problem with the validity criteria suggested in qualitative research is that there is little consistency across the articles as each author suggests a new set of criteria.

One approach in examining validity and reliability is to apply the criteria used in quantitative research. Hence, the criteria to be examined here are objectivity/intersubjectivity, construct validity, internal validity, external validity, and reliability.

Objectivity/Intersubjectivity

The basic issue of objectivity can be framed as one of relative neutrality and reasonable freedom from unacknowledged research biases (Miles & Huberman 1994). In a real-time longitudinal study, the researcher is in danger of losing objectivity and of becoming too involved with the organization, the people, and the process. Hence, Leonard-Barton (1990) claims that one may be perceived as, and may even become, an advocate rather than an observer.

According to King (1994), however, qualitative research, in seeking to describe and make sense of the world, does not require researchers to strive for objectivity and distance themselves from research participants. Indeed, to do so would make good qualitative research impossible, as the interviewer’s sensitivity to subjective aspects of his or her relationship with the interviewee is an essential part of the research process (King 1994:31).

This does not imply, however, that the issue of possible research bias can be ignored. It is just as important as in a structured quantitative interview that the findings are not simply the product of the researcher’s prejudices and prior experience. One way to guard against this bias is for the researcher to explicitly recognize his or her presuppositions and to make a conscious effort to set these aside in the analysis (Gummesson 1988). Furthermore, rival conclusions should be considered (Miles & Huberman 1994).

My experience from the first phase of the DnB study was that it was difficult to focus the questions and the analysis of the data when the research questions were too vague and broad. As such, developing a framework before collecting the data for the study was useful in guiding the collection and analysis of data. Nevertheless, it was important to be open-minded and receptive to new and surprising data. In the DnB study, for example, the positive effect of the reorganization process on the integration of cultures came as a complete surprise to me and thus needed further elaboration.

I also consciously searched for negative evidence and problems by interviewing outliers (Miles & Huberman 1994) and asking problem-oriented questions. In Gjensidige, the first interviews with the top management revealed a much more positive perception of the cultural integration process than I had expected. To explore whether this was a result of overreliance on elite informants, I continued posing problem-oriented questions to outliers and people at lower levels in the organization. Moreover, I told them about the DnB study to be explicit about my presuppositions.

Another important issue when assessing objectivity is whether other researchers can trace the interpretations made in the case studies, or what is called intersubjectivity. To deal with this issue, Miles & Huberman (1994) suggest that: (1) the study’s general methods and procedures should be described in detail, (2) one should be able to follow the process of analysis, (3) conclusions should be explicitly linked with exhibits of displayed data, and (4) the data from the study should be made available for reanalysis by others.

In response to these requirements, I described the study’s data collection procedures and processing in detail. Then, the primary data were displayed in the written report in the form of quotations and extracts from documents to support and illustrate the interpretations of the data. Because the study was written up in English, I included the Norwegian text in a separate appendix. Finally, all the primary data from the study were accessible for a small group of distinguished researchers.

Construct Validity

Construct validity refers to whether there is substantial evidence that the theoretical paradigm correctly corresponds to observation (Kirk & Miller 1986). In this form of validity, the issue is the legitimacy of the application of a given concept or theory to established facts.

The strength of qualitative research lies in the flexible and responsive interaction between the interviewer and the respondents (Sykes 1990). Thus, meaning can be probed, topics covered easily from a number of angles, and questions made clear for respondents. This is an advantage for exploring the concepts (construct or theoretical validity) and the relationships between them (internal validity). Similarly, Hakim (1987) says the great strength of qualitative research is the validity of data obtained because individuals are interviewed in sufficient detail for the results to be taken as true, correct, and believable reports of their views and experiences.

Construct validity can be strengthened by applying a longitudinal multicase approach, triangulation, and use of feedback loops. The advantage of applying a longitudinal approach is that one gets the opportunity to test sensitivity of construct measures to the passage of time. Leonard-Barton (1990), for example, found that one of her main constructs, communicability, varied across time and relative to different groups of users. Thus, the longitudinal study aided in defining the construct more precisely. By using more than one case study, one can validate stability of construct across situations (Leonard-Barton 1990). Since my study only consists of two case studies, the opportunity to test stability of constructs across cases is somewhat limited. However, the use of more than one unit of analysis helps to overcome this limitation.

Construct validity is strengthened by the use of multiple sources of evidence to build construct measures, which define the construct and distinguish it from other constructs. These multiple sources of evidence can include multiple viewpoints within and across the data sources. My study responds to these requirements in its sampling of interviewees and uses of multiple data sources.

Use of feedback loops implies returning to interviewees with interpretations and developing theory and actively seeking contradictions in data (Crabtree & Miller 1992; King 1994). In DnB, the written report had to be approved by the bank’s top management after the first data collection. Apart from one minor correction, the bank had no objections to the established facts. In their comments on my analysis, some of the top managers expressed the view that the political process had been overemphasized, and that the CEO’s role in initiating a strategic process was undervalued. Hence, an important objective in the second data collection was to explore these comments further. Moreover, the report was not as positive as the management had hoped for, and negotiations had to be conducted to publish the report. The result of these negotiations was that publication of the report was postponed one-and-a-half years.

The experiences from the first data collection in the DnB had some consequences. I was more cautious and brought up the problems of confidentiality and the need to publish at the outset of the Gjensidige study. Also, I had to struggle to get access to the DnB case for the second data collection and some of the information I asked for was not released. At Gjensidige, I sent a preliminary draft of the case chapter to the corporation’s top management for comments, in addition to having second interviews with a small number of people. Beside testing out the factual description, these sessions gave me the opportunity to test out the theoretical categories established as a result of the within-case analysis.

Internal Validity

Internal validity concerns the validity of the postulated relationships among the concepts. The main problem of internal validity as a criterion in qualitative research is that it is often not open to scrutiny. According to Sykes (1990), the researcher can always provide a plausible account and, with careful editing, may ensure its coherence. Recognition of this problem has led to calls for better documentation of the processes of data collection, the data itself, and the interpretative contribution of the researcher. The discussion of how I met these requirements was outlined in the section on objectivity/subjectivity above.

However, there are some advantages in using qualitative methods, too. First, the flexible and responsive methods of data collection allow cross-checking and amplification of information from individual units as it is generated. Respondents’ opinions and understandings can be thoroughly explored. The internal validity results from strategies that eliminate ambiguity and contradiction, filling in detail and establishing strong connections in data.

Second, the longitudinal study enables one to track cause and effect. Moreover, it can make one aware of intervening variables (Leonard-Barton 1990). Eisenhardt (1989:542) states, “Just as hypothesis testing research an apparent relationship may simply be a spurious correlation or may reflect the impact of some third variable on each of the other two. Therefore, it is important to discover the underlying reasons for why the relationship exists.”

Generalizability

According to Mitchell (1983), case studies are not based on statistical inference. Quite the contrary, the inferring process turns exclusively on the theoretically necessary links among the features in the case study. The validity of the extrapolation depends not on the typicality or representativeness of the case but on the cogency of the theoretical reasoning. Hartley (1994:225) claims, “The detailed knowledge of the organization and especially the knowledge about the processes underlying the behaviour and its context can help to specify the conditions under which behaviour can be expected to occur. In other words, the generalisation is about theoretical propositions not about populations.”

Generalizability is normally based on the assumption that this theory may be useful in making sense of similar persons or situations (Maxwell 1992). One way to increase the generalizability is to apply a multicase approach (Leonard-Barton 1990). The advantage of this approach is that one can replicate the findings from one case study to another. This replication logic is similar to that used on multiple experiments (Yin 1993).

Given the choice of two case studies, the generalizability criterion is not supported in this study. Through the discussion of my choices, I have tried to show that I had to strike a balance between the need for depth and mapping changes over time and the number of cases. In doing so, I deliberately chose to provide a deeper and richer look at each case, allowing the reader to make judgments about the applicability rather than making a case for generalizability.

Reliability

Reliability focuses on whether the process of the study is consistent and reasonably stable over time and across researchers and methods (Miles & Huberman 1994). In the context of qualitative research, reliability is concerned with two questions (Sykes 1990): Could the same study carried out by two researchers produce the same findings? and Could a study be repeated using the same researcher and respondents to yield the same findings?

The problem of reliability in qualitative research is that differences between replicated studies using different researchers are to be expected. However, while it may not be surprising that different researchers generate different findings and reach different conclusions, controlling for reliability may still be relevant. Kirk and Miller’s (1986:311) definition takes into account the particular relationship between the researcher’s orientation, the generation of data, and its interpretation:

For reliability to be calculated, it is incumbent on the scientific investigator to document his or her procedure. This must be accomplished at such a level of abstraction that the loci of decisions internal to the project are made apparent. The curious public deserves to know how the qualitative researcher prepares him or herself for the endeavour, and how the data is collected and analysed.

The study addresses these requirements by discussing my point of departure regarding experience and framework, the sampling and data collection procedures, and data analysis.

Case studies often lack academic rigor and are, as such, regarded as inferior to more rigorous methods where there are more specific guidelines for collecting and analyzing data. These criticisms stress that there is a need to be very explicit about the choices one makes and the need to justify them.

One reason why case studies are criticized may be that researchers disagree about the definition and the purpose of carrying out case studies. Case studies have been regarded as a design (Cook and Campbell 1979), as a qualitative methodology (Cassell and Symon 1994), as a particular data collection procedure (Andersen 1997), and as a research strategy (Yin 1989). Furthermore, the purpose for carrying out case studies is unclear. Some regard case studies as supplements to more rigorous qualitative studies to be carried out in the early stage of the research process; others claim that it can be used for multiple purposes and as a research strategy in its own right (Gummesson 1988; Yin 1989). Given this unclear status, researchers need to be very clear about their interpretation of the case study and the purpose of carrying out the study.

This article has taken Yin’s (1989) definition of the case study as a research strategy as a starting point and argued that the choice of the case study should be guided by the research question(s). In the illustrative study, I used a case study strategy because of a need to explore sensitive, ill-defined concepts in depth, over time, taking into account the context and history of the mergers and the existing knowledge about the phenomenon. However, the choice of a case study strategy extended rather than limited the number of decisions to be made. In Schramm’s (1971, cited in Yin 1989:22–23) words, “The essence of a case study, the central tendency among all types of case study, is that it tries to illuminate a decision or set of decisions, why they were taken, how they were implemented, and with what result.”

Hence, the purpose of this article has been to illustrate the wide range of decisions that need to be made in the context of a particular case study and to discuss the methodological considerations linked to these decisions. I argue that there is a particular need in case studies to be explicit about the methodological choices one makes and that these choices can be best illustrated through a case study of the case study strategy.

As in all case studies, however, there are limitations to the generalizability of using one particular case study for illustrative purposes. As such, the strength of linking the methodological considerations to a specific context and phenomenon also becomes a weakness. However, I would argue that the questions raised in this article are applicable to many case studies, but that the answers are very likely to vary. The design choices are shown in Table 4 . Hence, researchers choosing a longitudinal, comparative case study need to address the same set of questions with regard to design, data collection procedures, and analysis, but they are likely to come up with other conclusions, given their different research questions.

Adler, P. A., and P. Adler. 1994. Observational techniques. In Handbook of qualitative research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 377–92. London: Sage.

Andersen, S. S. 1997. Case-studier og generalisering: Forskningsstrategi og design (Case studies and generalization: Research strategy and design). Bergen, Norway: Fagbokforlaget.

Blake, R. R., and J. S. Mounton. 1985. How to achieve integration on the human side of the merger. Organizational Dynamics 13 (3): 41–56.

Bryman, A., and R. G. Burgess. 1999. Qualitative research. London: Sage.

Buono, A. F., and J. L. Bowditch. 1989. The human side of mergers and acquisitions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Cartwright, S., and C. L. Cooper. 1993. The psychological impact of mergers and acquisitions on the individual: A study of building society managers. Human Relations 46 (3): 327–47.

Cassell, C., and G. Symon, eds. 1994. Qualitative methods in organizational research: A practical guide. London: Sage.

Cook, T. D., and D. T. Campbell. 1979. Quasi experimentation: Design & analysis issues for field settings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Crabtree, B. F., and W. L. Miller. 1992. Primary care research: A multimethod typology and qualitative road map. In Doing qualitative research: Methods for primary care, edited by B. F. Crabtree and W. L. Miller, 3–28. Vol. 3. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Creswell, J. W. 1998. Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Denzin, N. K., and L. S. Lincoln. 2000. Handbook of qualitative research. London: Sage.

Eisenhardt, K. M. 1989. Building theories from case study research. Academy of Management Review 14 (4): 532–50.

Flick, U. 1998. An introduction to qualitative research. London: Sage.

George, A. L. 1979. Case studies and theory development: The method of structured, focused comparison. In Diplomacy: New approaches in history, theory, and policy, edited by P. G. Lauren, 43–68. New York: Free Press.

Gioia, D. A., and K. Chittipeddi. 1991. Sensemaking and sensegiving in strategic change initiation. Strategic Management Journal 12:433–48.

Glaser, B. G., and A. L. Strauss. 1967. The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago: Aldine.

Glick, W. H, G. P. Huber, C. C. Miller, D. H. Doty, and K. M. Sutcliffe. 1990. Studying changes in organizational design and effectiveness: Retrospective event histories and periodic assessments. Organization Science 1 (3): 293–312.

Gummesson, E. 1988. Qualitative methods in management research. Lund, Norway: Studentlitteratur, Chartwell-Bratt.

Hakim, C. 1987. Research design. Strategies and choices in the design of social research. Boston: Unwin Hyman.

Hamel, J., S. Dufour, and D. Fortin. 1993. Case study methods. London: Sage.

Hartley, J. F. 1994. Case studies in organizational research. In Qualitative methods in organizational research: A practical guide, edited by C. Cassell and G. Symon, 209–29. London: Sage.

Haspeslaph, P., and D. B. Jemison. 1991. The challenge of renewal through acquisitions. Planning Review 19 (2): 27–32.

King, N. 1994. The qualitative research interview. In Qualitative methods in organizational research: A practical guide, edited by C. Cassell and G. Symon, 14–36. London: Sage.

Kirk, J., and M. L. Miller. 1986. Reliability and validity in qualitative research. Qualitative Research Methods Series 1. London: Sage.

Leonard-Barton, D. 1990.Adual methodology for case studies: Synergistic use of a longitudinal single site with replicated multiple sites. Organization Science 1 (3): 248–66.

Marshall, C., and G. B. Rossman. 1999. Designing qualitative research. London: Sage.

Maxwell, J. A. 1992. Understanding and validity in qualitative research. Harvard Educational Review 62 (3): 279–99.

Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative data analysis. 2d ed. London: Sage.

Mitchell, J. C. 1983. Case and situation analysis. Sociology Review 51 (2): 187–211.

Nachmias, C., and D. Nachmias. 1981. Research methods in the social sciences. London: Edward Arnhold.

Pettigrew, A. M. 1990. Longitudinal field research on change: Theory and practice. Organization Science 1 (3): 267–92.

___. (1992). The character and significance of strategic process research. Strategic Management Journal 13:5–16.

Rossman, G. B., and S. F. Rallis. 1998. Learning in the field: An introduction to qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Schramm, W. 1971. Notes on case studies for instructional media projects. Working paper for Academy of Educational Development, Washington DC.

Schweiger, D. M., and J. P. Walsh. 1990. Mergers and acquisitions: An interdisciplinary view. In Research in personnel and human resource management, edited by G. R. Ferris and K. M. Rowland, 41–107. Greenwich, CT: JAI.

Silverman, D. 2000. Doing qualitative research: A practical handbook. London: Sage.

Stake, R. E. 1995. The art of case study research. London: Sage.

Strauss, A. L., and J. Corbin. 1990. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Sykes, W. 1990. Validity and reliability in qualitative market research: A review of the literature. Journal of the Market Research Society 32 (3): 289–328.

Waddington, D. 1994. Participant observation. In Qualitative methods in organizational research, edited by C. Cassell and G. Symon, 107–22. London: Sage.

Yin, R. K. 1989. Case study research: Design and methods. Applied Social Research Series, Vol. 5. London: Sage.

___. 1993. Applications of case study research. Applied Social Research Series, Vol. 34. London: Sage.

Christine Benedichte Meyer is an associate professor in the Department of Strategy and Management in the Norwegian School of Economics and Business Administration, Bergen-Sandviken, Norway. Her research interests are mergers and acquisitions, strategic change, and qualitative research. Recent publications include: “Allocation Processes in Mergers and Acquisitions: An Organisational Justice Perspective” (British Journal of Management 2001) and “Motives for Acquisitions in the Norwegian Financial Industry” (CEMS Business Review 1997).

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

White, R.E., Cooper, K. (2022). Case Study Research. In: Qualitative Research in the Post-Modern Era. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85124-8_7

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-85124-8_7

Published : 29 September 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-85126-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-85124-8

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Relevance of Case Study Method In Anthropology of Development

1990, Indian Anthropologist

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Increase Font Size

18 Case Study Method

Ms. Beliyaluxmi Devi

1. Introduction

2. Case Study

3 Techniques used for case studies

4 Sources of data for case studies

5 Types of case Studies

6 Advantage and limitation

Learning Objectives:

- To learn what is case study and distinction from case history; identify the application of case study;

- To discuss how to plan case study; and

- To understand the advantage and limitation of case study

- Introduction

Among the various methods of data collection, case study is certainly one popular form of qualitative analysis involving careful and complete observation of a case. A case is a social unit with a deviant behavior, and may be an event, problem, process, activity, programme, of a social unit. The unit may be a person, a family, an institution, a cultural group, a community or even an entire society (Kothari, 2014). But it is a bounded system that has the boundaries of the case. Case Study therefore is an intensive investigation of the particular unit under consideration. It is extensively used in psychology, education, sociology, anthropology, economics and political science. It aims at obtaining a complete and detailed account of a social phenomenon or a social event of a social unit. In case study, data can be collected from multiple sources by using any qualitative method of data collection like interviews, observation and it may also include documents, artifacts etc. Case study method is a type of data collection that goes in depth understanding rather than breadth. Case study can be descriptive as we observe and write in description as well as it can also be an exploratory that is we wrote what was said. Pierre Guillaume Frederic Le Play (1855), a mathematician and natural scientist, is considered as the founder of case study method as he used it for the first time in his publication Les Ouvriers Europeens.

2.1 Definitions of Case Study Methods

Case study has been defined differently by different scholars from time to time. Some of them are presented below.

- Young, P.V. (1984): Case study is a comprehensive study of a social unit, be it a person, a group of persons, an institute, a community or a family.

- Groode and Hatt (1953): It is a method of exploring and analyzing the life of a social unit

- Cooley, C.H. (2007): Case study depends our perception and gives clear insight into life directory.

- Bogardus, E. S. (1925): The method of examining specially and in detail a given situation

- Robson C. (1993): A strategy for doing research which involves an empirical investigation of a particular contemporary phenomenon within its real life context using multiple sources of evidence.

So critical analysis of these definitions, reveal that case study is a method of minute and detail study of a situation concerning a social unit in an intensive and comprehensive manner in order to understand the personal as well as hidden dimensions of human life.

2.2 Characteristics of Case Study

The main characteristics of the case study are (www.studylecturenotes.com):

A descriptive study:

- The data collected constitute descriptions of psychological processes and events, and of the contexts in which they occurred.

- The main emphasis is always on the construction of verbal descriptions of behavior or experience but rarely quantitative data may be collected. In short case study is more of a qualitative method rather than quantitative method.

- High levels of detail are provided.

- The behavior pattern of the concerned unit is studied directly wherein efforts are made to know the mutual inter-relationship of causal factors.

Narrowly focused:

- Typically a case study offers a complete and comprehensive description of all facets of a social unit, be it a single individual or may be a social group.

- Often the case study focuses on a limited aspect of a person, such as their psychopathological symptoms.

Combines objective and subjective data:

Researchers may combine objective and subjective data. Both the data are regarded as valid data for analysis. It enables case study to achieved in-depth understanding of the behavior and experience of a single individual.

Process-oriented:

- The case study method enables the researcher to explore and describe the nature of processes, which occur over time.

- In contrast to the experimental method, which basically provides a stilled ‘snapshot’ of processes, case study continued over time like for example the development of language in children over time.

2.3. Difference between Case Study and Case History

The Case study method helps retaining the holistic and meaningful characteristics of real life events – such as individual life cycles, small group behavior, etc. It is like a case history of a patient. As a patient goes to the doctor with some serious disease, the doctor records the case history. Analysis of case history helps in the diagnosis of the patient’s illness (http://www.differencebetween.com/difference-between-case-study-and-vs-case-history).

Although most of us confuse case study and case history to be the same, however, there exists a difference between these two terms. They are being used in many disciplines and allow the researcher to be more informative of people, and events. First, let us define the word case study. A case study refers to a research method where a person, group or an event is being investigated which is used by researchers whereas a case history, on the other hand, refers to a record of data which contributes to a case study; usually case history is used by doctors to investigate the patients. This is the main difference between a case study and case history.

(i) What is a Case Study?

A case study is a research method used to investigate an individual, a group of people, or a particular phenomenon. The case study has been used in many disciplines especially in social science, anthropology, sociology, psychology, and political science. A case study allows the researcher to gain an in-depth understanding of the topic. To conduct a case study, the researcher can use a number of techniques. For example, observation, interviews, usage of secondary data such as documents, records, etc. It usually goes on for a longer period because the researcher has to explore the topic deeply.

The case study method was first used in the clinical medicine so that the doctor has a clear understanding of the history of the patient. Various methods can be used in a case study for example a psychologist use observation to observe the individual, use interview method to broaden the understanding. To create a clear picture of the problem, the questions can be directed not only to the individual on whom the case study is being conducted but also on those who are related to the individual. A special feature of case studies is that it produces qualitative data that are rich and authentic.

(ii) What is a Case History?

Unlike the case study that refers to a method, a case history refers to a record of an individual or even a group. Case histories are used in many disciplines such as psychology, sociology, medicine, psychiatry, etc. It consists of all the necessary information of the individual. In medicine, a case history refers to a specific record that reveals the personal information, medical condition, the medication that has been used and special conditions of the individual. Having a case history can be very beneficial in treatment of disease. However, a case history does not necessarily have to be connected to an individual; it can even be of an event that took place. The case history is a recording that narrates a sequence of events. Such a narrative allows the researcher to look at an event in retrospect.

- Techniques used for Case Studies

The techniques of case studies includes –

(i) Observation

It is a systematic data collection approach. Researchers use all of their senses to examine people in natural settings or naturally occurring situations. Observation of a field setting involves: prolonged engagement in a setting or social situation.

(ii) Interview

It is questioning and discussing to a person for the purpose of an evaluation or to generate information. (iii) Secondary Data

Secondary data refers to data that was collected by someone through secondary sources. (iv) Documents

Any writing that provides information, especially information which is of official in nature.

(v) Records

Anything that provides permanent information which can rely on or providing an evident officially.

- Sources of Data for Case Study

In case study, information may be collected from various sources. Some of the important sources include:

- Life histories

- Personal documents

- Letters and records

- Biographies

- Information obtained through interviews

- Observation

- Types of Case Study

The following are the types of case study according to the Graham R Gibbs (2012) –

- Individual case study: This study was first done by Shaw, Clifford R. (1930). In individual case study, life of a particular person, his activities and his totalities were accompanied.

- Set of individual case study: Group of person that practice different culture was studies. As for instance those lives in rural area and those living in urban area there will different cases between them.

- Community studies: In community studies, it may include hundreds of people from a community that picked upon for some reason.

- Social Group Studies: Group of people that defined their social position, for example a group of musician or a group of drugs taker

- Studies of organizations and institutions: Study for a particular organizations or an institutions