Table of Contents:

Launching a secondary line, exclusive manufacturing rights for prada leather goods, adapting and thriving in an evolving fashion market, maintaining control over labels by going public, challenging conventional notions of beauty, fondazione prada: a hub for contemporary art exhibitions, addressing diversity and inclusion in the fashion industry, expansion into emerging markets: prada’s bold moves, nurturing young talent across industries, what did miuccia prada study, why is miuccia prada so important, what is miuccia prada’s inspiration, what is a fun fact about miuccia prada, the prada-bertelli partnership: a powerhouse duo.

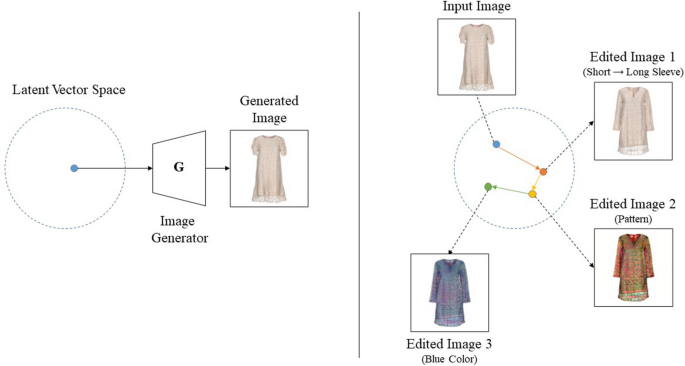

Journey back to the year 1978, a time of remarkable change and growth in fashion.

Miuccia Prada, the granddaughter of Prada’s founder, teamed up with Patrizio Bertelli to expand the brand beyond its original leather goods offerings. Together, they embarked on an ambitious journey that would change the fashion industry forever.

So, what did this dynamic duo achieve?

Inspired by her own nickname, Miuccia introduced Miu Miu – a secondary line that caters to younger fashion enthusiasts seeking luxury products at more accessible price points. Miuccia’s move to launch Miu Miu enabled Prada to expand its consumer base while maintaining the brand’s quality and exclusivity.

Bertelli’s expertise in manufacturing led to exclusive rights for producing all things Prada leather. This partnership proved fruitful as it allowed them both creative freedom and quality control over their products. The result? Prada became synonymous with luxury leather goods, and their reputation for quality and craftsmanship only grew stronger.

But that’s not all. The Prada-Bertelli partnership also invested over $120 million into major stores worldwide, solidifying their position as a global fashion powerhouse.

What’s truly remarkable about this partnership, however, is that they managed to maintain their personal relationship throughout their professional endeavors. Despite their different backgrounds – Miuccia was a former member of the Italian Communist Party, while Bertelli studied political science – they shared a common vision for the brand and worked tirelessly to make it a reality.

The Prada-Bertelli partnership is a testament to the power of collaboration and innovation in the fashion industry. Their legacy continues to inspire and influence designers and fashion enthusiasts around the world.

Organizational Culture and Going Public: The Prada Way

Let’s talk about the secret sauce behind Prada’s success.

Their organizational culture has allowed them to adapt and thrive in an ever-changing fashion market without compromising their core values or design philosophy.

So, how did they do it?

Innovation is key when navigating a rapidly changing industry like fashion. Miuccia Prada, the creative force behind the brand, has always been ahead of her time. She pushes boundaries with unconventional designs that challenge traditional notions of beauty while still remaining desirable enough for luxury consumers.

To keep up with demand and expand globally, going public was a strategic move for this Italian powerhouse brand. The Miuccia Prada case study details how Prada’s IPO allowed them to maintain control over their labels and grow their presence in emerging markets like China.

A remarkable organizational culture, original designs and astute business decisions have allowed Prada to remain a formidable presence in the fashion industry.

Want to learn more about Miuccia Prada’s journey? Dive into this Vogue interview for an insightful look at her life and career.

Unexpected Inspirations Behind Collections

Let’s talk about Miuccia Prada’s creative process. You might be surprised to learn that her inspirations often come from unconventional sources, making her collections truly unique and groundbreaking. Curious? Let me explain:

Miuccia Prada, the founder of Miuccia Prada and Miu Miu, is known for her unconventional approach to fashion. Miuccia Prada’s creative ideas come from a range of sources, such as her studies in political science and experience being part of the Italian Communist Party.

Prada’s collections often challenge conventional notions of beauty, incorporating unexpected materials and designs. For example, her Fondazione Prada in Milan features a gold leaf-covered exterior and a bar made entirely of whale bones.

So, what can we learn from Miuccia Prada’s approach? Don’t be afraid to think outside the box when it comes to finding inspiration for your own creative projects – you never know where a seemingly unrelated idea might lead.

Artistic Endeavors Beyond Fashion Design

Did you know she founded Fondazione Prada , an institution dedicated to contemporary art exhibitions?

That’s right.

This creative powerhouse doesn’t limit herself to just designing clothes and accessories.

- Collaborating with renowned artists:

Miuccia has teamed up with artists like Carsten Holler and Theaster Gates during Art Basel Miami events, showcasing her passion for creativity in various forms.

- Innovative materials:

Remember when industrial nylon became a luxury material back in the ’80s? You can thank Miuccia for that pioneering move.

This avant-garde designer is always pushing boundaries, both within and beyond fashion circles.

Let’s delve into the importance of diversity and inclusion in the fashion industry, shall we?

In an industry where representation matters, Miuccia Prada, the founder of Miuccia Prada and Fondazione Prada, is no stranger to pushing boundaries beyond just design aesthetics.

Enter Ava Duvernay – a prominent figure who had discussions with Prada’s team on the need for more diverse representation both in front of and behind the scenes.

Incorporating a variety of perspectives is essential for Prada to stay current in today’s dynamic world.

- Fashion Factoid: Miuccia was one of the first designers to cast black models such as Naomi Campbell back in 1994 – challenging traditional beauty standards even then. (source)

Ready for more? Dive into this Vogue article on diversity in fashion here.

Miuccia Prada’s commitment to pushing boundaries goes beyond design; it encompasses creating an inclusive space within the industry itself. She was a member of the Italian Communist Party and holds a Ph.D. in political science. Her partnership with Met Patrizio Bertelli, CEO of Prada, has been instrumental in the brand’s success.

Let’s talk about adaptability.

Prada has not only made waves with its designs but also through its strategic expansion into emerging markets like Russia and India, which were often overlooked by other luxury fashion houses. This bold move allowed the brand to reach new audiences while staying ahead of the competition.

Russia and India:

The decision to enter these markets was a calculated risk that paid off handsomely for Prada. With an increasing number of affluent consumers in both countries, there was a growing demand for high-end luxury products – perfect for Miuccia Prada’s innovative creations.

Acquiring a High-End Footwear Company:

To further strengthen their presence in these regions, Prada acquired Church’s Shoes – a renowned British footwear company known for its exceptional craftsmanship. This acquisition enabled them to maintain local production while benefiting from increased productivity levels. Learn more about this strategic partnership here.

- Maintaining Local Production: By acquiring Church’s Shoes, Prada ensured that they could continue producing high-quality footwear locally without compromising on quality or design integrity.

- Innovative Collaboration: The partnership between two iconic brands opened up opportunities for creative collaborations that pushed boundaries within the industry.

In conclusion, Miuccia Prada’s ability to adapt and evolve her brand is evident not just through her designs but also through strategic expansion into emerging markets. By taking calculated risks and forging innovative partnerships, Prada continues to push the boundaries of fashion while maintaining its status as a global luxury powerhouse.

Miuccia Prada is not just a fashion icon; she’s also an advocate for nurturing young talent in various fields. Her dedication to fostering creativity goes beyond the realm of fashion design, as evidenced by her collaboration with renowned architect Rem Koolhaas .

This partnership led to the creation of Fondazione Prada – a cultural mini-village that combines repurposed distillery spaces and newly designed buildings. The unique venue hosts contemporary art exhibitions, pushing boundaries and inspiring up-and-coming artists worldwide.

But Miuccia’s passion doesn’t stop there. She dreams of opening a school dedicated specifically to training aspiring movie directors someday soon too.

- Fostering creativity: Collaboration with Rem Koolhaas on Fondazione Prada project showcases Miuccia’s commitment to nurturing young talent across industries.

- Dreaming big: Opening a film director training school is another example of how she wants to inspire future generations in different creative fields.

In today’s world where artistic expression can be stifled or limited, it’s refreshing to see influential figures like Miuccia championing new talents and ideas within various industries.

FAQs in Relation to Miuccia Prada Case Study

She also trained as a mime artist at Teatro Piccolo and performed for five years before joining her family’s luxury fashion business.

Miuccia Prada is one of the most influential designers in the fashion industry. As head designer and co-CEO of Prada Group, she has transformed the brand into an international powerhouse known for its innovative designs, unconventional materials, and artistic collaborations.

Miuccia Prada draws inspiration from various sources such as art, history, politics, and everyday life. Her collections often challenge conventional norms by combining contrasting elements like modernity with tradition or high-fashion with utilitarianism. This unique approach to design has made her stand out in the competitive world of fashion.

A lesser-known fact about Miuccia Prada is that she was once part of Italy’s Communist Party during her university days. Despite coming from a wealthy background, she engaged in activism and even sold handbags on street corners to raise funds for party activities.

Overall, the Miuccia Prada Case Study highlights the brand’s ability to adapt and thrive in an ever-changing fashion market. From launching a secondary line to expanding into emerging markets, Prada has maintained its position as a leader in the industry.

Prada’s commitment to nurturing young talent across industries through collaborations with renowned artists and architects is evident in their Fondazione Prada exhibitions. Additionally, their efforts towards addressing diversity and inclusion within the fashion industry are commendable.

In conclusion, Miuccia Prada’s innovative approach to design and business strategy has led to continued success for her eponymous brand.

Was This Article Helpful?

You're never to cool to learn new things, here are sources for further research.

Please note: 440 Industries is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon.com.

Fashion Marketing

Retail marketing, fashion entrepreneurship, fashion finance.

MORE ARTICLES FROM OUR BLOG

Diesel Case Study: Fashion Industry’s Sustainable Revolution

Explore the Diesel Case Study: fashion industry’s sustainable shift through cleaner engines, innovative campaigns, and Smart Rebels focus.

The OTB Group Case Study: Core Values and Growth Strategies

Discover The OTB Group Case Study, highlighting core values, growth strategies, sustainability efforts, and digital innovation in the fashion world.

Jil Sander Case Study: Fashion Legacy & Adaptations

Explore the Jill Sander Case Study, delving into her minimalist fashion legacy and how creative directors Lucie and Luke Meier adapt to market changes.

Marni Case Study: Bold Fashion and Diverse Collaborations

Explore the Marni Case Study, highlighting bold fashion, diverse collaborations, and innovative digital expansion in this captivating analysis.

440 Industries Disclaimer, Credits and acknowledgements. Privacy Policy

Copyright © 440 industries 2024.

Fashion Design Management: Case Study

Updated for the 2024 admissions cycle.

How do you transform an idea into a successful fashion brand, and how do you define “success”? Fashion Design Management merges creativity, business savvy, and ethics to realize the potential of fashion products and ensure they reach the right consumers.

In the College of Human Ecology, students approach all areas of study by centering the health and well-being of people and communities. In Fashion Design Management, this means thinking about the needs and desires of consumers as well as the impact of fashion products, production, and promotion on the environment, garment workers, and society more generally. How do you learn about your consumer (i.e., “target market”) and then align your branding, communications, product lines, manufacturing, marketing, and retailing with their preferences?

The Fashion Design Management Case Study will provide an opportunity for you to answer some of these questions and showcase your creativity, analytic skills, and understanding of fashion design management. The written statements, though separate from the Case Study, will also offer a space to share your experience, background, and perspective on fashion design management.

The Fashion Design Management Case Study is required of all first-year and transfer applicants interested in this option of the Fashion Design Management option of the Fashion Design & Management major*. This submission will be considered along with your required application materials (Common Application, transcripts, etc). Fashion Design Management applicants who do not submit the Case Study will not be considered.

*Applicants interested in the Fashion Design option must follow separate fashion design portfolio guidelines .

Submitting your Fashion Design Management Case Study All Fashion Design Management Case Study components must be submitted via SlideRoom . Mailed materials will not be accepted, reviewed, or returned.

Deadlines Your Fashion Design Management Case Study must be submitted to SlideRoom by the application deadline that corresponds with your application status. Late submissions will not be considered.

Fashion Design Management Case Study Components The Fashion Design Management Case Study consists of the following (2) required components and (1) optional component (see below). Applicants must complete and submit the (2) required components.

- Required — Written Statements

- Required — Case Study

- Optional — Your own creative work

All work must be original and produced by the applicant, WITH NO ASSISTANCE FROM CONSULTANTS, ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, ETC. Any images or graphics that are not the work of the applicant must be properly cited (for example, a mood board of collaged images from a magazine must include attributions to the source). Submissions found to have significant similarity to work posted on the internet or from other sources will not be accepted.

Fashion design management case study instructions (2024).

Tell us more about yourself and your interest in Fashion Design Management by responding to each question/prompt below. Submit (1 – 2) pages with your responses to SlideRoom.

- Students in the College of Human Ecology approach the study of human health and well-being by considering many different scholarly perspectives, including human development, nutrition, psychology, history, economics, design, and the social and material sciences, among others. What interests you about studying Fashion Design Management in this kind of interdisciplinary educational context? (Maximum: 150 words)

- Please describe any fashion and/or business related experiences (including jobs, courses, internships, and volunteer work) in which you have participated. Share more about the creative, as well as the business, financial, and management aspects of these positions. (Maximum: 100 words)

- What do you believe is the greatest challenge facing the fashion industry today? What solutions would you recommend from the perspective of fashion design management? (Maximum: 150 words)

- Of all the places, people, and media platforms where fashion is seen, which has most informed and influenced you and why? (Maximum: 100 words)

The Fashion Design Management Case Study allows you to present your perspective on the business side of fashion and the management of design.

Prompt: Create a new fashion brand or expand/revamp an existing brand for an underserved or niche consumer. Develop a cohesive presentation of your work that you would pitch to an investor (in the case of a new fashion brand) or to upper-level management (in the case of an existing brand). Respond to each portion of the Case Study as outlined below.

- Brand identity and target market. Develop a brand identity and describe the target customer for your brand. Indicate what research and resources you used to select and understand this consumer group. Describe how your proposed brand would meet the needs and preferences of this customer. Develop a brand identity that clearly and cohesively communicates the mission, values, and personality of your brand through both visuals and written word. Submit (1 – 2) page to SlideRoom.

- Product line. Create or curate three looks that would be worn by the target customer and indicate the product category or categories that are part of the brand. For example, a brand might specialize in footwear, accessories, or a particular category of apparel, like swimwear, sleepwear, activewear, etc., whereas other brands might manufacture across a range of different product categories. To illustrate the consumer looks, you may provide original sketches, take photos of models you have styled, or use existing images from other sources, such as catalogs, magazines, or the internet. Be sure to identify your original work and accurately credit the work that you sourced. For each look, indicate how it exemplifies your brand identity. Submit (1) page per look (maximum 3 pages) to SlideRoom.

- Brand promotion. Consider how you would advertise this new brand to your target customers. Explain why your promotional strategy will effectively reach your customers and what will make you stand out from other competing fashion brands. Think outside the box for a unique approach. You could provide a sample advertisement, social media post, or promotional video. Submit (1 – 2) pages to SlideRoom.

- Production, distribution, and retailing . Share production and/or sourcing choices you might make for the product line(s). Identify and describe the distribution channel(s) the brand will use to reach consumers. Provide a general overview of the anticipated financial, environmental, and social considerations affecting your choices. Submit (1 – 2) pages to SlideRoom.

Submit up to three (3) additional images of your original creative work for consideration. Submissions can include photos, videos, and blog posts, as well as garments or accessories you have made.

Submit optional creative work (maximum of 3 pages) to SlideRoom.

- Think about the mission of the College of Human Ecology — Improving lives by exploring and shaping connections to the natural, social, and built environment — and consider developing a brand that articulates with this commitment to health and well-being in some way.

- To start your research, you may want to create a list of potential brands you think would be interesting for this challenge. Visit their websites and look for “Company Information” or “About Us” information to learn more about their background and customer.

- Explore the media platforms you use to learn about fashion and think about consumers who may be underrepresented in these spaces. How will you address both the needs and the desires of an overlooked consumer group?

- Consider identifying a target consumer who is different from you in some way and use the Case Study as an opportunity to research and learn about the needs of this consumer group. You may conduct research in the library, talk with people who identify in this consumer category, search for research reports, read journal articles, and find magazines or social media accounts targeted to this group, among many other research approaches.

- Visit a store in your area to look more closely at the merchandise and to talk to store employees.

- Be sure that if you use images, media, or styling looks with garments you did not create, that you indicate the sources owned/created by others.

Frequently Asked Questions

The fashion industry and fashion design management bridge creative and business components. The Case Study is intended to give prospective Fashion Design Management students a platform to highlight their business acumen, creativity, and consideration of social and cultural contexts. We are interested in understanding how you perceive fashion around you and the innovations, improvements, and interventions you might bring to the industry.

By creating a brand and detailing the products, consumers, branding, promotion, production, and distribution, your Case Study will show us a bit more about your perspective on fashion and your hopes for the future of the industry.

To start your research, you may create a list of potential retailers you think would be interesting for this challenge. Visit their websites and look for “Company Information” or “About Us” information to learn more about their background and customer. You can also see if there is a store in your area and take a visit to look more closely at the merchandise and talk to store employees.

Resources for images can come from print catalogs, fair use image databases, or you may take your own photographs. Be sure to appropriately credit images and photos if you use those owned by someone else.

The written statement portion of the Case Study allows you to describe your work experience. If you have visuals (images or designs) that resulted from your work experience, you can add this as your “Optional Creative Work” in SlideRoom.

Email us if you have additional questions about the design supplement.

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

- 02 Apr 2024

- Research & Ideas

Employees Out Sick? Inside One Company's Creative Approach to Staying Productive

Regular absenteeism can hobble output and even bring down a business. But fostering a collaborative culture that brings managers together can help companies weather surges of sick days and no-shows. Research by Jorge Tamayo shows how.

- 05 Dec 2023

- Cold Call Podcast

Tommy Hilfiger’s Adaptive Clothing Line: Making Fashion Inclusive

In 2017, Tommy Hilfiger launched its adaptive fashion line to provide fashion apparel that aims to make dressing easier. By 2020, it was still a relatively unknown line in the U.S. and the Tommy Hilfiger team was continuing to learn more about how to serve these new customers. Should the team make adaptive clothing available beyond the U.S., or is a global expansion premature? Assistant Professor Elizabeth Keenan discusses the opportunities and challenges that accompanied the introduction of a new product line that effectively serves an entirely new customer while simultaneously starting a movement to provide fashion for all in the case, “Tommy Hilfiger Adaptive: Fashion for All.”

- 25 Apr 2023

How SHEIN and Temu Conquered Fast Fashion—and Forged a New Business Model

The platforms SHEIN and Temu match consumer demand and factory output, bringing Chinese production to the rest of the world. The companies have remade fast fashion, but their pioneering approach has the potential to go far beyond retail, says John Deighton.

- 04 Apr 2023

Two Centuries of Business Leaders Who Took a Stand on Social Issues

Executives going back to George Cadbury and J. N. Tata have been trying to improve life for their workers and communities, according to the book Deeply Responsible Business: A Global History of Values-Driven Leadership by Geoffrey Jones. He highlights three practices that deeply responsible companies share.

- 26 Jul 2022

Can Bombas Reach New Customers while Maintaining Its Social Mission?

Bombas was started in 2013 with a dual mission: to deliver quality socks and donate much-needed footwear to people living in shelters. By 2021, it had become one of America’s most visible buy-one-give-one companies, with over $250 million in annual revenue and 50 million pairs of socks donated. Later, as Bombas expanded into underwear, t-shirts, and slippers, the company struggled to determine what pace of growth would best allow it to reach new customers while maintaining its social mission. Harvard Business School assistant professor Elizabeth Keenan discusses the case, "Bee-ing Better at Bombas."

- 24 May 2021

Can Fabric Waste Become Fashion’s Resource?

COVID-19 worsened the textile waste crisis. Now it's time for the fashion industry to address this spiraling problem, say Geoffrey Jones and Shelly Xu. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 18 May 2020

- Working Paper Summaries

No Line Left Behind: Assortative Matching Inside the Firm

This paper studies how buyer relationships influence suppliers' internal organization of labor. The results emphasize that suppliers to the global market, when they are beholden to a small set of powerful buyers, may be driven to allocate managerial skill to service these relationships, even at the expense of productivity.

- 08 Apr 2019

- Sharpening Your Skills

The Life of Luxury and How to Sell It

Luxury is its own market, but who shops there? Who sells there? What's the best strategy? Researchers at Harvard Business School examine consumerism at the top of the curve. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 02 Apr 2019

Managerial Quality and Productivity Dynamics

Which managerial skills, traits, and practices matter most for productivity? This study of a large garment firm in India analyzes the integration of features of managerial quality into a production process characterized by learning by doing.

- 08 Nov 2018

Could Big Data Replace the Creative Director at the Gap?

Is it time to throw out the creative director and rely on big data to predict what consumers want to wear next? Assistant Professor Ayelet Israeli discusses how Gap CEO Art Peck considers a bold idea to boost sales. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 21 May 2018

How Would You Price One of the World's Great Watches?

For companies with lots of innovation stuffed in their products, getting the price right is a crucial decision. Stefan Thomke discusses how watchmaker A. Lange & Söhne puts a price on its 173-year-old craftsmanship. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 24 Aug 2017

Does Le Pliage Help or Hurt the Longchamp Luxury Brand?

Longchamp's iconic but affordable Le Pliage bag is a conundrum for the company, explains Jill Avery in this podcast. Does an affordable luxury product work against the top-tier brand? Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 13 Mar 2017

Hiding Products From Customers May Ultimately Boost Sales

Is it smart for retailers to display their wares to customers a few at a time or all at once? The answer depends largely on the product category, according to research by Kris Johnson Ferreira and Joel Goh. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 06 Jan 2016

- What Do You Think?

Why Do Leaders Get Their Timing Wrong?

SUMMING UP: Is good management timing primarily a function of strategy or culture? James Heskett's readers add their opinions. What do YOU think? Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 21 Nov 2015

HBS Cases: Stella McCartney Combines High Fashion with Environmental Values

Fashion designer Stella McCartney is the subject of a recent case study by Anat Keinan showing that luxury and sustainability need not be mutually exclusive. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 02 Sep 2015

What's Wrong With Amazon’s Low-Retention HR Strategy?

SUMMING UP Does Amazon's "only the strongest survive" employee-retention policy make for a better company or improved customer relationships? Jim Heskett's readers chime in. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 20 Jul 2015

Globalization Hasn’t Killed the Manufacturing Cluster

In today's global markets, companies have many choices to procure what they need to develop, build, and sell product. So who needs a manufacturing cluster, such as Detroit? Research by Gary Pisano and Giulio Buciuni shows that in some industries, location still matters. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 29 Sep 2014

Why Do Outlet Stores Exist?

Created in the 1930s, outlet stores allowed retailers to dispose of unpopular items at fire-sale prices. Today, outlets seem outmoded and unnecessary—stores have bargain racks, after all. Donald K. Ngwe explains why outlets still exist. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 09 Jun 2014

The Manager in Red Sneakers

Wearing the corporate uniform may not be the best way to dress for success. Research by Silvia Bellezza, Francesca Gino, and Anat Keinan shows there may be prestige advantages when you stand out rather than fit in. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

- 06 Jan 2014

Mechanisms of Technology Re-Emergence and Identity Change in a Mature Field: Swiss Watchmaking, 1970-2008

According to most theories of technological change, old technologies tend to disappear when newer ones arrive. As this paper argues, however, market demand for old technologies may wane only to emerge again at a later point in time, as seems to be the case for products like Swiss watches, fountain pens, streetcars, independent bookstores, and vinyl records, which have all begun to claim significant market interest again. Looking specifically at watchmaking, the author examines dynamics of technology re-emergence and the mechanisms whereby this re-emergence occurs in mature industries and fields. Swiss watchmakers had dominated their industry and the mechanical watch movement for nearly two centuries, but their reign ended abruptly in the mid-1970s at the onset of the "Quartz Revolution" (also known as the "Quartz Crisis"). By 1983, two-thirds of all watch industry jobs in Switzerland were gone. More recently, however, as the field has moved toward a focus on luxury, a "re-coupling" of product, organizational, and community identity has allowed master craftsmen to continue building their works of art. The study makes three main contributions: 1) It highlights the importance of studying technology-in-practice as a lens on viewing organizational and institutional change. 2) It extends the theorization of identity to products, organizations, and communities and embeds these within cycles of technology change. 3) It suggests the importance of understanding field-level change as tentative and time-bound: This perspective may allow deeper insights into the mechanisms that propel emergence, and even re-emergence, of seemingly "dead" technologies and industries. (Read an interview with Ryan Raffaelli about his research.) Key concepts include: The value of some products may go beyond pure functionality to embrace non-functional aspects that can influence consumer buying behaviors. Introducing a new technology is not always the only way to get ahead of the curve when older technologies or industries appear to be reaching the end of their life. Industries that successfully re-emerge are able to redefine their competitive set - the group of organizations upon which they want to compete and the value proposition that they send to the consumer. There is significant interplay among community, organization, and product identities. Swiss watches—as well as fountain pens, streetcars, independent bookstores and vinyl records—are all examples of technologies once considered dead that have rematerialized to claim significant market interest. For Swiss watchmakers, "who we are" (as a community) and "what we do" (as watch producers) were mutually constitutive and may have been a potent force in the processes that sought re-coupling in the face of the de-coupling precipitated by technological change. Although new or discontinuous technologies tend to displace older ones, legacy technologies can re-emerge, coexist with, and even come to dominate newer technologies. Core to this process is the creation—and recreation—of product, organization, and community identities that resonate with the re-emergence of markets for legacy technologies. Substantial economic change may not be contained only within organizational or industry boundaries, but also extend outward to include broader forces related to field-level change. Closed for comment; 0 Comments.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Practice of sustainable fashion design considering customer emotions and personal tastes.

- Department of Clothing and Textiles, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, South Korea

This study aimed to determine a sustainable design practice approach that can satisfy customer emotions and personal tastes, which designers need in the early stages of the SFD process, and improve environmental performance. The research was conducted through a case study and interviews. For case studies, the specific design methods of fashion brands, which have been ranked sustainable over the last 3 years in the world’s top fashion magazines favored by the public, were researched. The results of the case studies were used to draw questions for the in-depth interviews. The results are as follows: first, the design approaches of SFBs were categorized into “eco-friendly materials,” “functional durability design,” “reuse and remanufacturing,” “emotional durability design,” and sustainable fashion technology. Each type’s specific design approach methods were organized into a checklist for the practice of SFD and then reflected in the interview questions. From the results of the interviews, it was noted that the sustainable design approaches perceived by Korean designers were “eco-friendly materials,” “reuse and remanufacturing,” and “functional durability design.” Moreover, it was mentioned that specific methods of emotional durability design and sustainable fashion technology need to be acquired. By applying the checklist to the interviewees, interview participants could conveniently and quickly recognize how to apply sustainable design through the inventory. This study is significant because it presents a checklist, an efficient tool for sustainable design approaches, and a sustainable design practice method that can satisfy customer emotions and personal tastes and improve environmental performance.

Introduction

The fashion industry is one of the industries that have contributed significantly to the growth of the global consumer goods industry for decades. Nevertheless, the environmental damage caused by water pollution and CO2 produced at each stage of the fashion supply chain is the second largest after the oil industry ( Villemain, 2019 ). Hence, the fashion industry’s responsibility for sustainable environmental development and its obligation to restore the environment are emphasized, as much as the share of the fashion industry in the global industry ( Caniato et al., 2012 ; Dissanayake and Sinha, 2015 ; Lawless and Medvedev, 2016 ; Maldini et al., 2019 ; O’Connell, 2020 ). Since the mid-2000s, industrial supply systems around the world have been affected by sustainability and have struggled to develop environmental management strategies ( Reoberto and Esposito, 2016 ). Previous studies have stated that a green supply system based on a circular economy is important in presenting a vision for sustainable manufacturing ( Zhu et al., 2011 ; Stahel, 2016 ; Geissdoerfer et al., 2017 ). H&M has regularly published public reports on sustainability activities since it launched an ethical fashion brand called “Conscious Collection” in 2011 ( Baker, 2011 ). In addition to mainstream brands such as Nike and M&S, it is considered a leader in sustainable business execution ( Kozlowski et al., 2019 ; Claxton and Kent, 2020 ). Many fashion companies, including Uniqlo, North Face, and New Balance, also recognize the importance of sustainability and supply chain management ( Shen, 2014 ). Early studies on sustainable fashion focused on eco-designs, which focused on the environmental harm during the product life cycle, from using materials to production and disposal. They were followed by studies on various tools for measuring performance in the three aspects of sustainability and strategies for sustainable fashion design (SFD) ( Pigosso et al., 2013 ; Rossi et al., 2016 ; Ahmad et al., 2018 ; Karell and Niinimäki, 2020 ). Emotionally durable design aims at a circular economy as a design approach that extends the life of a product by encouraging a more durable and resilient relationship with the product through the emotional experience that occurs between the product and the consumer ( Haines-Gadd et al., 2018 ). It can be said that it is a design method that allows modern people who consume selectively and wisely to choose sustainable product design according to their sensibility and personal taste. In previous studies, consumers agreed to the practice of sustainability but rejected sustainable products that did not fit their tastes ( Karell and Niinimäki, 2020 ). Additionally, while about 80% of sustainability impacts are determined at the design stage, which is an early stage in the production process, design methods still tend to rely on the designer’s intuition ( Ramani et al., 2010 ; Ribeiro et al., 2013 ; Ahmad et al., 2018 ; Keshavarz-Ghorabaee et al., 2019 ; Karell and Niinimäki, 2020 ). Designers play an essential role in sustainable environmental performance and decisively impact the future environmental effects of their products ( Boks, 2006 ; Ramani et al., 2010 ; Ribeiro et al., 2013 ; Ahmad et al., 2018 ; Keshavarz-Ghorabaee et al., 2019 ; Karell and Niinimäki, 2020 ). Nevertheless, fashion designers still need to understand the complexity of sustainable fashion issues and the unpredictable future of fashion design related to diversity, rapidly changing trends, and consumers ( Kozlowski et al., 2019 ). The world’s well-known fashion magazines, such as Vogue, Elle, and Harper’s Bazaar, rank and release articles on fashion products of sustainable fashion brands (SFBs). This implies that the public interest in sustainable fashion products is high. Thus, it is imperative to propose practical methods for easy-to-use SFD, in which the complexity of sustainability and the intuition and experience of designers are objectified.

The purpose of this study is to support the circular economy by satisfying customers’ sensibility and personal taste, improving environmental performance, and determining a design approach that designers can easily use in SFD.

Literature review

Sustainable fashion design.

Sustainability means that businesses must address social goals such as environmental conservation, social justice, and economic development ( Yıldızbaşı et al., 2021 ). It is in the same vein as the importance of business performance measured by considering the three dimensions of sustainability in the overall green industry ( Pattnaik et al., 2021 ). SFD refers to design that considers the social, environmental, and economic impacts associated with the fashion products in the entire life cycle until the end of their life, from the raw materials to the use and disposal ( Niinimäki, 2006 ; Kozlowski et al., 2019 ). Ecological, economic, and social factors have been the basis of many studies as the triple bottom line (TBL) of sustainability ( Raza et al., 2021 ). Today’s SFD has evolved into a system that plans products to suppress the occurrence of environmentally hazardous elements in the fashion product supply chain ( Ceschin and Gaziulusoy, 2016 ; Kozlowski et al., 2019 ). In the fashion industry, three out of five apparel items are discarded within a year of production ( Puspita and Chae, 2021 ). Problem-solving in sustainable fashion requires improving the complex apparel supply chain and the consumers, companies, and governments involved. Several previous studies have noted that designers are crucial to influencing changes in the sustainable design industry ( Lawless and Medvedev, 2016 ; Hur and Cassidy, 2019 ; Kozlowski et al., 2019 ). To achieve the sustainability goals of fashion products, designers should play an active role in design from the early stage of the production process by predicting the ethical behavior of fashion product production and consumption ( Ceschin and Gaziulusoy, 2016 ). For SFD, Kozlowski et al. (2019) stated that aesthetic and cultural dimensions should also be considered along with performance in three aspects: the environmental, social, and economic aspects of sustainability. These aspects must be regarded because sustainable fashion products that have been produced so far have become another environmentally hazardous factor because they have not been chosen as consumers’ tastes are not met. Currently, various tools are used to predict the performance of sustainable fashion supply chains ( Bovea and Pérez-Belis, 2012 ; Kozlowski et al., 2019 ). However, considering that approximately 80% of the sustainability impact over the entire life cycle of fashion products are determined in the design stage ( Ribeiro et al., 2013 ; Ahmad et al., 2018 ), it is necessary to explore various approaches to SFD.

Sustainable fashion brand

Fashion companies such as Zara, Nike, and H&M, including Kering, which currently has a portfolio of luxury brands, regularly publish public reports describing their sustainability activities ( Kozlowski et al., 2019 ). Most sections of the fashion industry, such as general apparel, sportswear, shoes, and underwear, are paying attention to sustainable product development in consideration of environmental, economic, and social issues. In 2010, H&M announced the first sustainable collection made from sustainable materials such as organic cotton, linen, recycled polyester, and Tencel of wood pulp fabric ( Portuguez, 2010 ). Then, in 2011, it launched a new “Conscious” collection and pledged to develop the Sustainable Apparel Coalition, an initiative devised to expand the use of organic and sustainable materials, educate cotton farmers, and measure the environment, impact, and labor practices for apparel and shoe manufacturing ( Baker, 2011 ). In 2011, Patagonia also started the “Do Not Buy This Jacket” campaign, which promotes conscious buying, upcycling, and product use changes ( Bandyopadhyay and Ray, 2020 ). Simultaneously, Patagonia operated a recycling program called the Common Threads Initiative, which focused on the “4 Rs” to enable the recycling of its products. It aims to reduce resale through eBay and recycling based on customer partnerships ( Patagonia Inc, 2011 ). One of the interests of Patagonia was in ethics for the life of workers, and Patagonia became one of the first fashion brands to take responsibility in partnership with Fair Trade USA. This movement has advocated for improved social and environmental standards since 2014 ( Teen Vogue, 2019 ; Bandyopadhyay and Ray, 2020 ). In 2014, to develop a roadmap to create a more sustainable supply chain and conserve endangered forests in Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam, Stella McCartney, H&M, Eileen Fisher, Patagonia, and Inditex/Zara formed a group of promising forest conservation policies. The group created a shared “knowledge map” for the viscose supply chain to facilitate the removal of endangered forest fibers and pledged to support a long-term conservation solution for high-priority forest areas, such as rainforests in Indonesia and rainforests and subarctic forests in Canada. Furthermore, they have pledged to support the development of sustainable fabric alternatives made of recycled fabrics, recycled materials, and agricultural byproducts such as straw ( Sustainable brands, 2014 ). Stella McCartney is a London-based luxury brand belonging to Kering that does not use unsustainable animal materials, such as fur, leather, and feathers. It is known to operate a brand with ceaseless sustainable thinking. Their 2019 collection was rated as the most sustainable among the past collections because 75% of the collection used Econyl and recycled polyester, while the rest used organic cotton or upcycled denim. They announced Koba faux fur made from corn byproducts mixed with recycled polyester as an alternative to plastic options ( Frost, 2019 ).

In 2015, Kering announced Environmental Profit and Loss (EP and L), a sustainability statement calling for industry accountability. In 2016, EP and L were applied to all brands of Kering. Further, the EP and L demanded environmental and ethical responsibility across the supply chain from damage to environmental impacts caused by fashion products and not to evade fair-trade labor practice, carbon imprint, and energy and resource conservation ( Social Media Today, 2015 ). It started with upcycling fashion brands in 2008 and evolved as Kolon Industries, a large fashion company, launched “RE: CODE,” an upcycling fashion brand that introduced fashion products manufactured by recycling fashion products to be incinerated and automotive parts ( Park and Kim, 2014 ). RE: CODE was launched in 2012 as a sustainable brand by Kolon Industries, Inc., a large fashion company in South Korea. It creates new value based on upcycling, which refers to making new clothes by recycling deadstock and clothing waste. RE: CODE breaks fashion stereotypes, creates new uses, and encourages the world to participate in environmental and sustainable societal movements ( Kolon Industries, 2012 ). Kolon Industries has been working on the Noah Project since 2016 as a campaign to protect endangered animals and plants in South Korea. “Kolon Sports” of Kolon Industries applied 100% eco-friendly materials and techniques to all products in the collection in 2020 as part of the Noah Project ( Park, 2020 ).

As described above, the sustainable activities of fashion companies are group activities and campaigns focused on eco-friendly materials and material recycling. More and more fashion brands were putting the concept of sustainability at the forefront of their design goals.

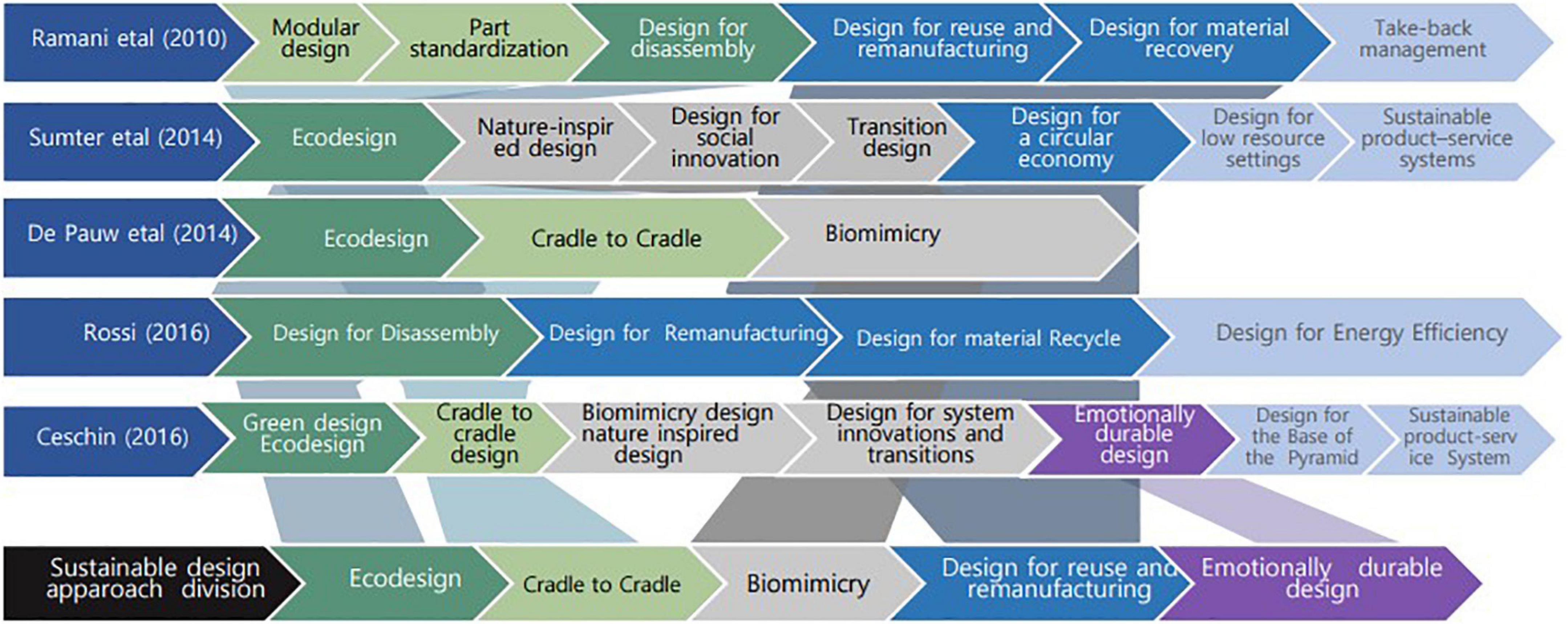

Sustainable design approach and method

Previous studies have dealt with guides for various conceptual design tools and strategies to help apparel designers implement sustainability. Ceschin and Gaziulusoy (2016) classified sustainable design approaches and methods into “green design and eco-design,” “emotionally durable design,” “nature-inspired design,” “cradle-to-cradle design,” “biomimicry design,” “design for the base of the pyramid,” “sustainable product-service system design,” and “design for system innovations and transitions.” Rossi et al. (2016) summarized design approaches with “design for X concept” and classified them into “design for disassembly,” “design for remanufacturing,” design for material recycling, and “design for energy efficiency.” Based on some previous studies, Irwin (2015) and Sumter et al. (2020) classified design approaches by adding “design for a circular economy” to “eco-design,” “nature-inspired design,” “sustainable product-service systems,” “design for low resource settings,” “design for social innovation,” and “transition design.” De Pauw et al. (2014) conducted exploratory case studies to compare “eco-design” as an eco-friendly method to the methods of “biomimicry” and “cradle-to-cradle.” Väänänen and Pöllänen (2020) stated that the introduction of craft techniques into recycling and upcycling products makes products aesthetically pleasing and meaningful, which can be associated with the emotional durability of products that increases consumer attachment. Attachment can be one of the solutions to these problems because sustainability products in the past have not elicited empathy for respecting the individualities and tastes of consumers, compared to the increase in environmental awareness among consumers ( Karell and Niinimäki, 2020 ). Ramani et al. (2010) have classified “modular design,” “part standardization,” “take-back management,” “design for disassembly,” “design for reuse and remanufacturing,” and “design for material recovery” as design methods for improving end-of-life (EOL) management that enables multiple life cycles of “cradle-to-cradle.” Ramani et al. (2010) mentioned developing a laser-based manufacturing process to reduce material waste. Further, it involves not releasing hazardous elements during design and processes using computer-aided design (CAD) and computer-aided process planning (CAPP), which can affect the design in the early stage.

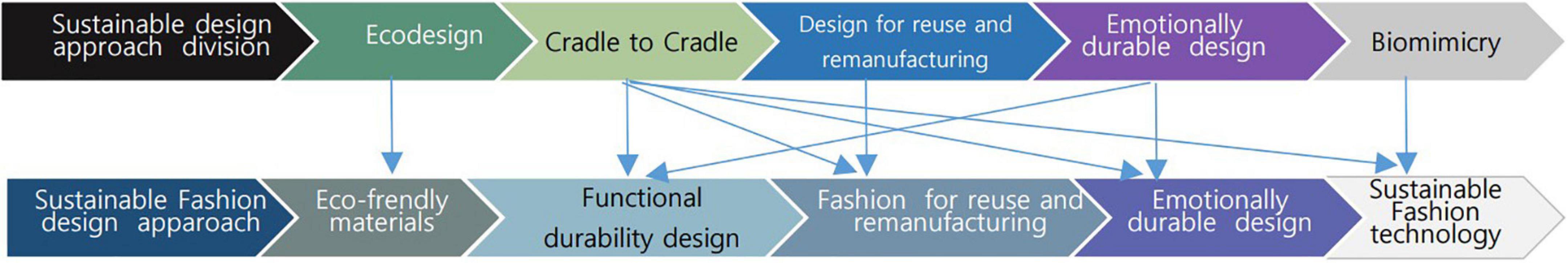

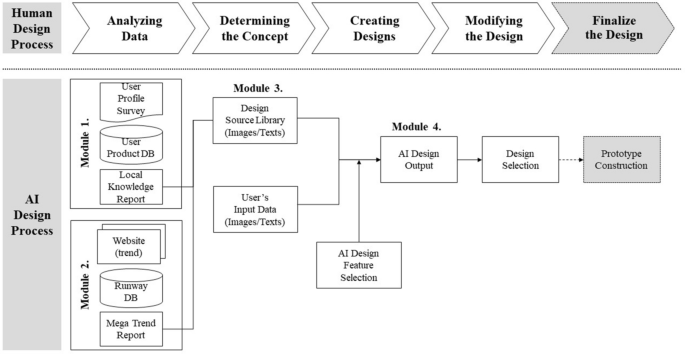

Figure 1 summarizes the classification of design approaches by researchers in previous studies. Based on these earlier studies on sustainable design, we classified design approaches into five categories in the early stage of sustainable design in this study. These include “eco-design,” “cradle-to-cradle,” “biomimicry,” “design for reuse and remanufacturing,” and “emotionally durable design,” which were used in the case analysis of sustainable designs in the next section. Figure 1 shows the process of deriving five sustainable design approaches based on the classifications of the five previous studies.

Figure 1. Process of classifying sustainable design approaches based on previous studies.

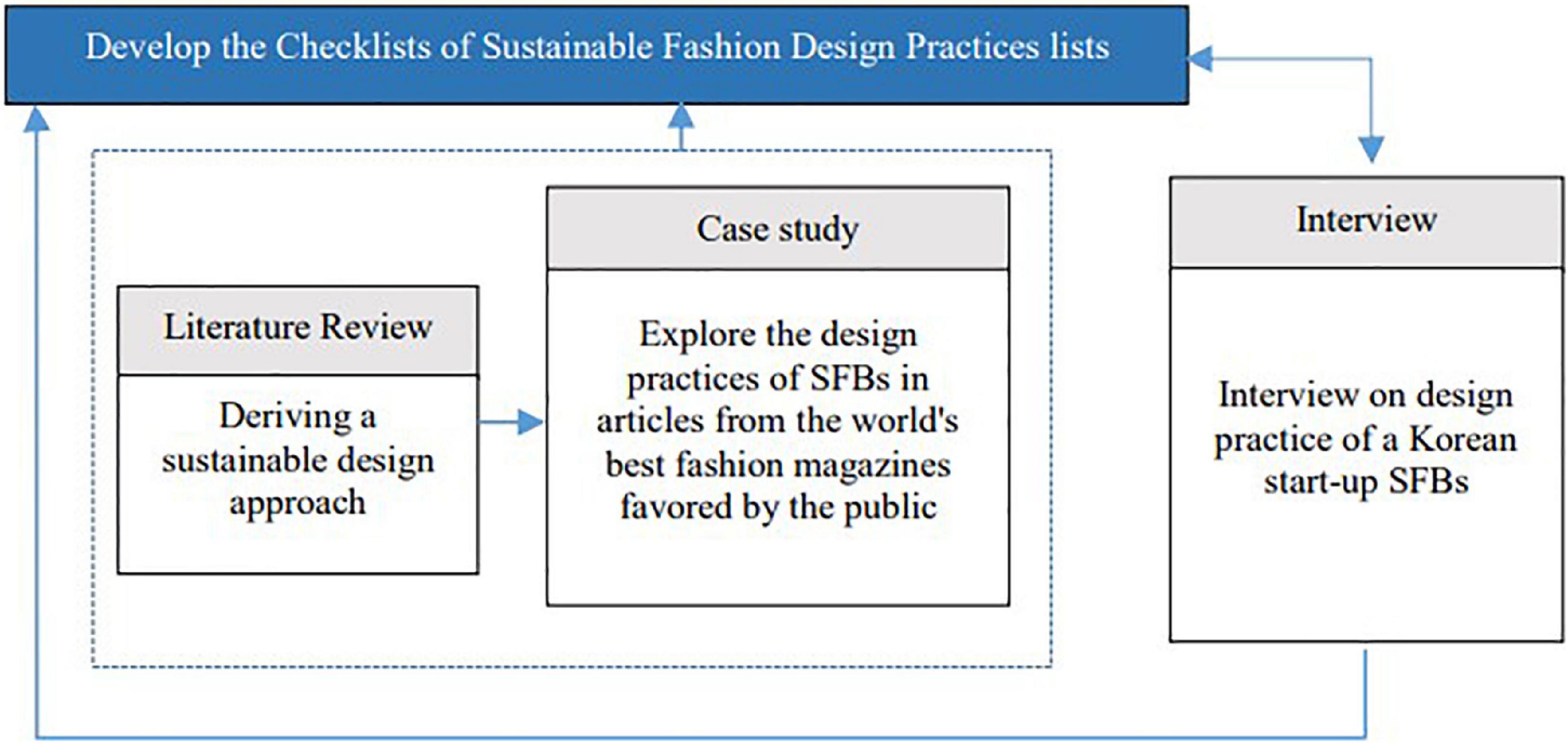

Methodology

The research was conducted through a case study and interviews. The research procedure is (1) classifying sustainable design approaches through a review of previous research; (2) based on this, the sustainable design approach and detailed design method for fashion designers were investigated in the world’s top fashion magazines favored by the public, (3) using the results of the case study as a tool for an in-depth interview with designers of SFB in Korea, and (4) determining design approaches that designers can easily use in the early stages of the SFD process. Figure 2 illustrates the framework of the study.

Figure 2. Framework of this study.

Regarding the research method, it analyzed the cases for the representation methods of SFBs that were ranked in the world’s top fashion magazines based on the sustainable design approaches derived through the literature review. The analysis focused on a total of 141 SFBs in nine articles searched using “the best SFB” in Vogue, Elle, and Harper’s Bazaar, which are the world’s top popular fashion magazines for 3 years from 2019 to 2021. Additionally, for the analysis of the design approaches of the collected 149 SFBs, additional design methods were identified in the introduction window and product introduction of brand websites, along with the contents of the articles. Table 1 summarizes the titles of the nine articles for the top-ranking fashion brands in the analyzed fashion magazines.

Table 1. Articles on sustainable fashion brands (SFBs) selected from the world’s top popular fashion magazines.

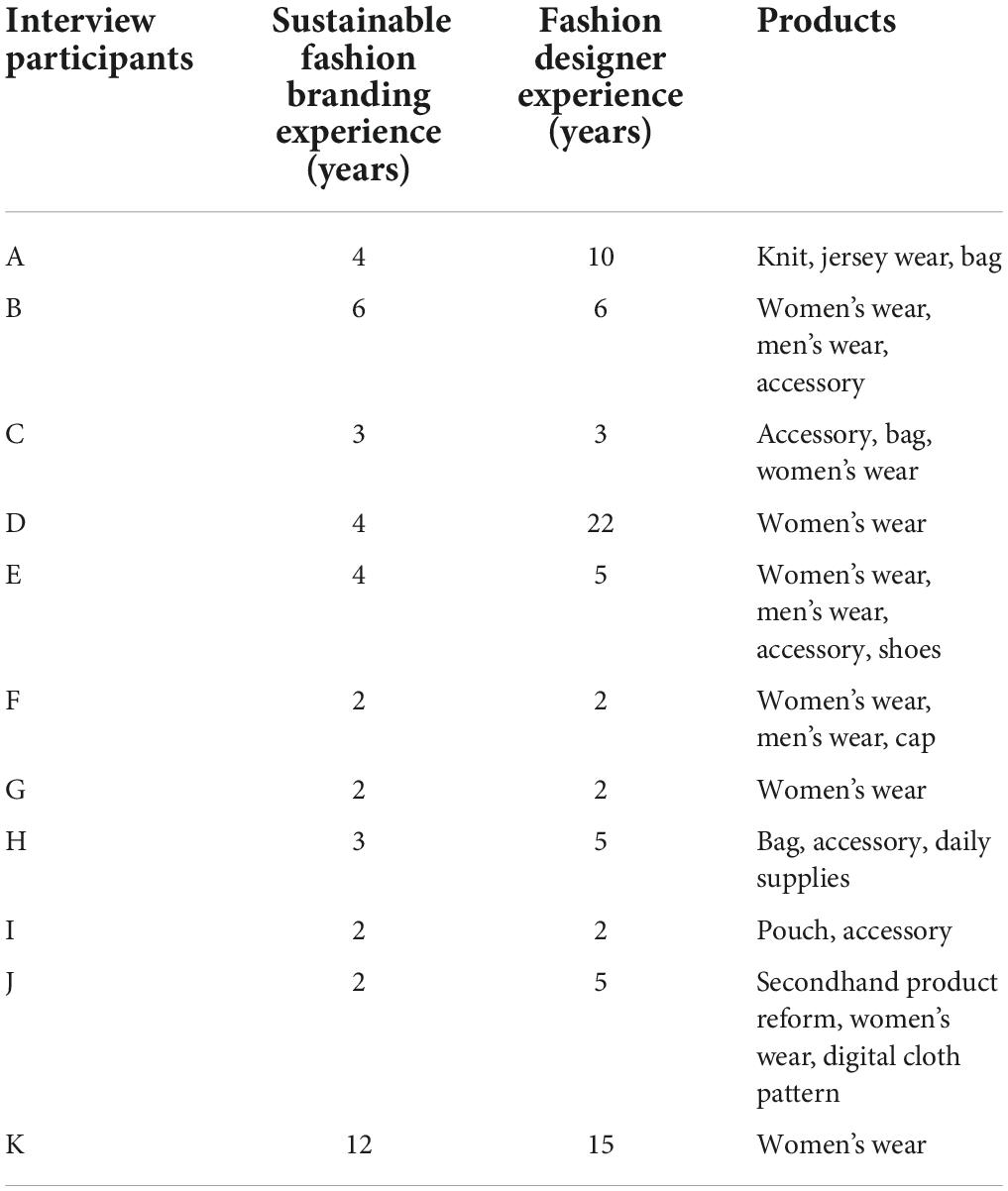

The interviews were conducted from 14 September 2021 to 30 March 2022. The interview participants were randomly selected from among the brands selected or applied for the SFB support project of the Korean or local government. Eleven designers from sustainable fashion start-ups in Korea participated in the interviews. Each interview was conducted face-to-face or via Zoom and lasted approximately 40–50 min. Table 2 shows the contents related to the interview participants, including Sustainable Fashion Branding Experience, Fashion Designer Experience, and fashion products designed by them. Letters were assigned according to the order of the interviews to ensure anonymity.

Table 2. Interview participants.

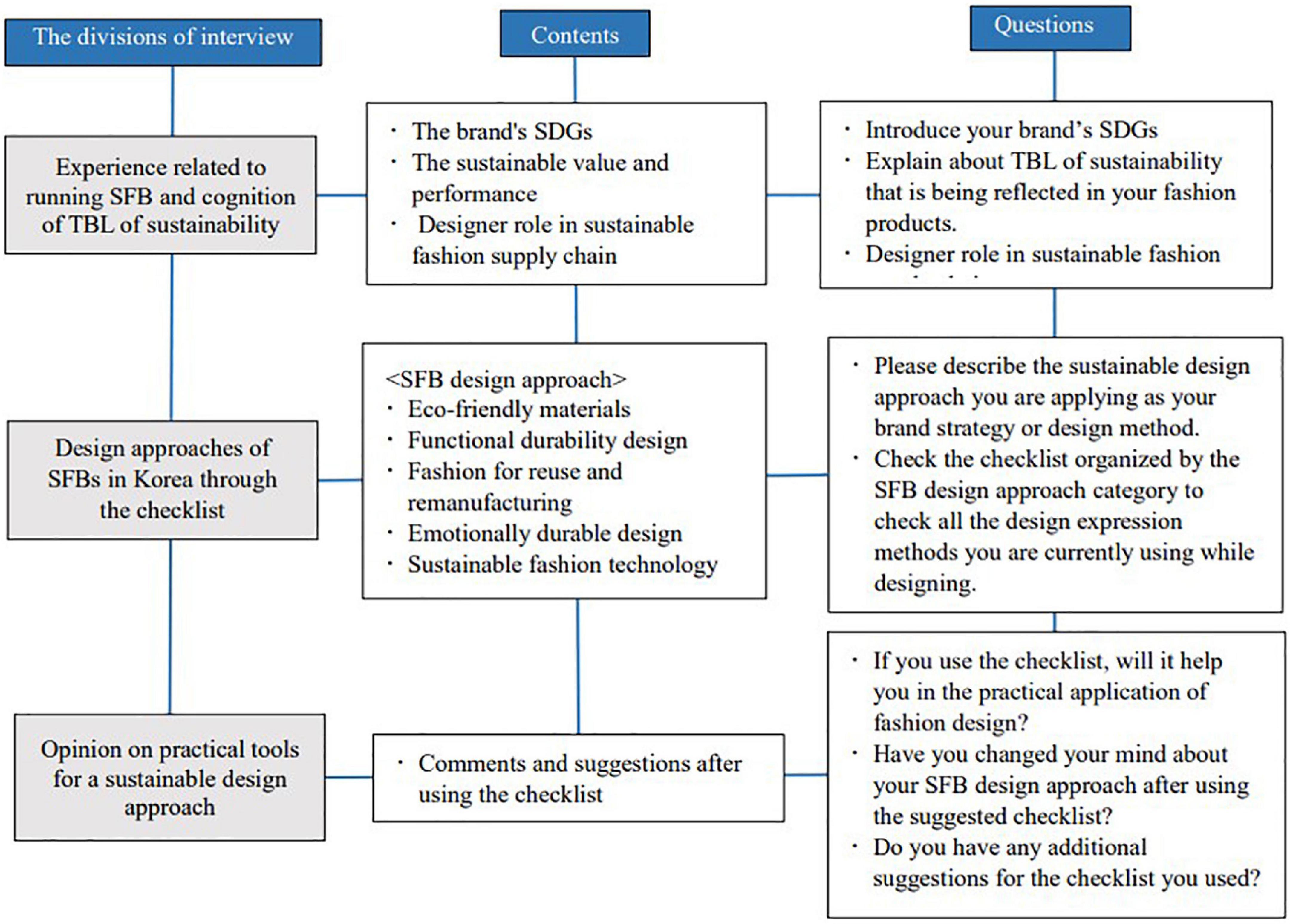

The interviews were recorded and transcribed with the consent of the interviewees. Semi-structured questions were used for the interview, and additional questions were asked to obtain specific answers and opinions. As shown in Figure 3 , the interview questions were mainly composed of three questions. The first part concerned the launch date of SFB, the goal of sustainable development, and cognition of triple bottom line (TBL) of sustainability. The second part was to identify the difference between the design approach currently used by the interviewed designers and the design method shown in the world’s best fashion magazines favored by the public, through the SFB design approach checklist based on the case study results. Finally, the third part consisted of comments and suggestions on practical tools for a sustainable design approach after the interview participants had used the checklist. Figure 3 is the frame of the interview question extraction process based on the checklist derived from the case study.

Figure 3. Interview questions on sustainable fashion brands’ (SFBs) design approach methods.

Case study of sustainable fashion brands’ design approach

A total of 149 SFBs were ranked by the world’s most popular fashion magazines for 3 years. Among them, 34 SFBs appeared twice or more, indicating that the SFB market has not yet been established stably. This may be an obvious result because it has only been approximately 10 years since fully fledged SFBs emerged. However, 35 brands were ranked only once in 2019, 19 in 2020, and 56 in 2021. Fashion brand activities were reduced in 2020 because of the SFB market shrinkage caused by COVID-19. Nevertheless, it can be seen that public interest in SFBs has increased since the number of new fashion brands in popular fashion magazines grew significantly in 2021. Thus, it is necessary to suggest a practical design approach for SFD that consumers can directly choose. Figure 4 shows the design classification process of the SFB based on the sustainable design approach classification derived from the literature review and was used as the category for the following case study.

Figure 4. Design approach classification process of sustainable fashion brand (SFB).

As a result of the case analysis based on the sustainable design approach of the previous studies, the design approaches of SFBs were categorized into: “eco-friendly materials,” “functional durability design,” “fashion for reuse and remanufacturing,” “emotionally durable design,” and “sustainable fashion technology.” Furthermore, case analysis was conducted for the specific design approaches applied in the early stage of the design process of SFB based on these categories as follows:

Eco-friendly materials

The use of eco-friendly materials is one of the metrics of sustainable fashion. Specifically, as eco-friendly materials are used, the sustainability of each product increases ( Wang and Shen, 2017 ). The environmental impact during the product life cycle can be minimized only by choosing eco-friendly materials ( Ribeiro et al., 2013 ; Ahmad et al., 2018 ; Claxton and Kent, 2020 ). In particular, sustainable fashion products made of organic fabrics are fundamental to the supply chain because they contain fewer chemicals that harm the environment ( Shen, 2014 ). At the initial design stage, designers should consider using biodegradable materials that can be returned to the soil without causing additional damage to nature ( Gurova and Morozova, 2018 ).

The study of SFB product cases revealed that the selection of eco-friendly materials was required in almost all companies as a design approach. It appeared with eco-friendly materials, 100% organic cotton materials, a method tracing the origin of materials, or using vegetable materials. Additionally, it adopted a short-distance distribution to use eco-friendly materials near the production site as SFB’s design strategy to reduce CO2 emissions.

1. Certified sustainable materials using 100% organic cotton materials include Patagonia (Nagurney and Yu, 2012), H&M Conscious ( Bédat, 2019 ), Stella McCartney ( McCartney, 2020 ), Mara Hoffman ( Bédat, 2019 ), and Theory ( Elle Fashion Team, 2020 ), Burberry ( Wang, 2020 ), House of Sunny ( Davis, 2021 ), BITE Studios ( Elle Fashion Team, 2021 ), Reformation ( Bédat, 2019 ), Baserange ( Elle Fashion Team, 2021 ), and Yasmina Q ( Davis, 2021 ), among others.

2. Tracing the origin of eco-friendly materials: Stella McCartney has adopted a method of tracing the origin of trees supplying viscose raw materials used strategically to help the environment by protecting endangered forests ( Davis, 2021 ) and, further, including those facilitating tracing of all eco-friendly materials on the brand’s website ( Elle Fashion Team, 2021 ).

3. Using vegetable materials: Vegan materials include Bleusalt’s signature fabric, an entirely vegan material with beech ( Penrose and Hearst, 2019 ). Moreover, notably, Alohas made shoes with two vegan types of leather from cactus and corn ( Elle Fashion Team, 2021 ). VEJA’s sneakers used organic cotton for fair trade and soles made of rubber grown in the Amazon rainforest ( Elle Fashion Team, 2021 ). Additionally, Allbirds often makes soles with sugarcane and manufacture uppers using eucalyptus or natural merino wool ( Davis, 2021 ).

4. Net zero: Mulberry produces bags by developing the lowest carbon leather ( Vogue, 2021 ). Sonia Carrasco uses only organic or vegan materials for clothes and tags, labels, packaging, and papers ( Elle Fashion Team, 2021 ). Wright Le Chapelain maintained a transparent supply chain of sustainability and fabrics sourced from UK factories over short distances ( Elle Fashion Team, 2021 ). Tretorn also launched eco-friendly sneakers made of locally sourced canvases ( Davis, 2021 ).

Functional durability design

The properties and quantity of materials and the shape of the clothes used by fashion designers affect the quality and durability, which can remarkably impact the life of clothes ( Claxton and Kent, 2020 ). Connor-Crabb et al. (2016) argued that trans -seasonal, multi-functionality, modularity, alterability, and physical emotional durability are approaches to functional durability design. Further, they stated that on-demand production is included in this category. According to Rahman and Gong (2016) , functional durability design extends the physical life of durable, organic, and recyclable fabric materials from a technical perspective. Moreover, it is a method of extending aesthetic life based on the emotional durability of the product. This study separated the approaches to emotional durability and discussed them. Transformable apparel provides two or more functional or aesthetic alternative styles ( Rahman and Gong, 2016 ) and can extend the life of clothes. Modularized garment design is the task of dividing a garment into several parts based on the functional analysis of different parts. As many examples of various functions and specifications are included in each piece, user-oriented clothes can be designed quickly and flexibly ( Zhou et al., 2016 ). According to the case study, the method of functional durability design appeared to be on-demand production, quality, durability, multi-functionality, and alterability.

1. On-demand production: The House of Sunny works on only two seasonal collections per year and produces small quantities based on orders. The design team spends more time researching sustainable fabrics, manufacturing methods, and sourcing materials ( Elle Fashion Team, 2020 , 2021 ; Davis, 2021 ). Further, Maison Cléo minimizes waste by selling it only once a week ( Elle Fashion Team, 2020 ). Mary produces timeless limited editions based on orders without inventory ( Elle Fashion Team, 2021 ).

2. Quality and durability: Everlane has chosen the finest materials and manufacturing methods for timeless products, such as the highest class cashmere sweaters, Italian shoes, and Peruvian Pima t-shirts ( EVERLANE, 2021 ).

3. Alterability: Misha Nonoo’s “Easy 8” collection features eight pieces that can produce 22 changeable looks ( Davis, 2021 ). Nynne has included various styling options and is placed in a seam line across the leather skirt so that the length can be reduced if the user gets bored of the size and introduced reversible shearling jackets for two completely different looks ( Davis, 2021 ). The CAES has proposed timeless items that can be worn throughout the year by adding a premium to slow fashion with a concept that compares clothes to protective “cases” that cover our bodies ( Elle Fashion Team, 2021 ). Petit Pli designed clothes that can be worn for a long time, even if the body changes, by creating variable garments that can be increased or decreased in length depending on the wearer in a chic-pleated manner. Cho proposed varying designs with clothes that could be adjusted in size based on a detachable panel in the style of clothes manufactured using recycled plastic bottles and ethically sourced ( Elle Fashion Team, 2021 ).

Fashion for reuse and remanufacturing

Energy is required for designing and producing new products ( DeLong et al., 2014 ). Therefore, sustainable fashion designers should consider valuable new product design methods that facilitate multiple life cycles by reusing and reconstructing discarded products. Janigo and Wu (2015) classified design approaches for reuse and remanufacturing into repair and alteration, upcycle, downcycle, post-consumer used and secondhand clothing, post-consumer recycled clothing, and redesigned clothing. Gurova and Morozova (2018) stated that upcycling, reuse, and repurposing methods exist.

In the case study of the SFB approach, the methods of reuse and remanufacturing were sourcing sustainable yarns from waste, redesigning clothing, and repurposing.

1. Recycled yarns: Burberry heritage trench coats and lightweight classic car coats are produced using Econyl, a sustainable nylon yarn made of recycled fishing nets, fabric scraps, and industrial plastics ( Wang, 2020 ). Baum und Pferdgarten uses recycled denim and recycled polyester from plastic bottles ( Elle Fashion Team, 2021 ; Vogue, 2021 ). Maggie Marilyn sourced 100% of synthetic fibers discarded after consumption ( Marius, 2020 ). Prada launched Prada Re-Nylon, a line of sustainable bags and accessories made of discarded cloth and recycled plastics collected from the sea and fishing nets ( Elle Fashion Team, 2020 ). JW Anderson introduced belt totes made of recycled plastic ( Elle Fashion Team, 2021 ). PAPER London launched swimsuits produced using recycled yarns from fishing nets, which would have taken 600 years to discompose ( Elle Fashion Team, 2021 ). The Pringle of Scotland, known as knitwear, has used 100% recycled fibers to produce limited-edition jumpers and recycled clothing tags ( Elle Fashion Team, 2021 ).

2. Redesigned clothing: Acne Studios has designed super-sized jackets and unique mini-skirts of modern images that the brand has as products that recycled discarded black denim and red leather ( Elle Fashion Team, 2021 ). Rave Review introduced luxurious upcycled fashions using fabrics and deadstock clothes and created tufty overcoats by upcycling vintage bedspreads ( Wang, 2020 ). Marine Serre has sourced discarded scarves, secondhand shirts, and wetsuit materials, turning them into futuristic practical wear from parkas to panel dresses ( Lim, 2019 ).

3. Repurposing: Mulberry bags aim to extend product life through repair, restoration, buyback, reselling, and repurposing ( Vogue, 2021 ). Matty Bovan sourced the fabrics and prints used in its collection by working with the Liberty Fabric Archives. In a previous collection, they recycled soccer pads to inflate the shoulders and redesigned old fur into new shapes ( Bonacic, 2020 ).

Emotionally durable design

An emotionally durable fashion design approach can extend the product life cycle based on the emotional attachment between consumers and products ( Claxton and Kent, 2020 ). Emotionally durable fashion originates from a business environment in which products connect consumers and manufacturers and provide conversation pieces that facilitate the ease of upgrades, services, and repairs ( Chapman, 2005 ). Consumers are attached to physical objects through complex interactions between cultural norms, personal preferences, and behaviors ( Connor-Crabb et al., 2016 ). Fashion customers with a taste for handcrafted and luxurious products are emotionally attracted to secondhand clothes reborn with felt, quilt, and dye and purchase them ( Janigo and Wu, 2015 ). Consumers stay attached for longer to products that elicit amazement and endless pleasure ( Armstrong et al., 2016 ). Consumers’ attachment to products that meet their personal characteristics and tastes leads to an extension of their product life. Design strategies that encourage social contact through sharing or group use may lead to attachment ( Armstrong et al., 2016 ). Upcycling designs using heirlooms or garments with strong personal attachment have emotional durability ( DeLong et al., 2014 ). Furthermore, handicrafts made by artisans have substantial value as a medium of sustainable fashion with devotion, as sustainable design reflecting local resources and culture can lead to the derivation of narratives ( Sandhu, 2020 ).

In the study of SFBs, emotionally durable fashion designs appeared to collaborate with artisans and artists in the production area, handwoven material sourcing, and emotional design concepts.

1. Collaboration with artisans: Bite Studios creates sustainable fashion products by collaborating with emerging and existing artists in various works, such as natural dyeing techniques, printmaking, and handmade jewelry ( Vogue, 2021 ). Chopova Lowena ( Elle Fashion Team, 2021 ) pursues uniqueness with vibrant combinations of Bulgarian folk handcraft materials made through craftsmanship and English tailoring ( Elle Fashion Team, 2020 ; BROWNS FASHION, 2021 ). Hereu’s bags and shoes are products made by local artisans at the home of the founding designer of Spanish nationality ( Elle Fashion Team, 2021 ). Ballen Pellettiere accessories commemorate Colombian fashion and artisans’ crafts, and playful embroidery paired with a unique shape is a trademark of their handmade bags ( Penrose and Hearst, 2019 ).

2. Handwoven material sourcing: Bethany Williams’ recycled tents and handwoven denim ensembles reflect their signature multicolor patchwork and streetwear sentiments ( Lim, 2019 ), while wooden buttons handcrafted by carving are discarded birches that reflect consumers’ individualities and preferences ( Bonačić, 2021 ). Bodes are brands that use recycled vintage cloth as materials and have unique handcrafted works containing stories of quilting, mending, and appliances by sourcing fabrics from all over the world, including Victorian quilts and 100-year-old linens ( BODE, 2021 ). Brother Vellies’ shoes and handbags are handmade in South Africa, Ethiopia, Kenya, and Morocco, combining the expertise of local artisans.

3. Personal design concept: Nynne approaches sustainable fashion consumer sentiment with a unique design concept named “Diana” dress as the brand’s signature work ( Davis, 2021 ).

Sustainable fashion technology

Digital tools can be used to find new behaviors in existing materials by modifying their structures, and a new understanding based on this can expand the possibilities provided to designers. By extensively using 3D design software, designers can design complex woven clothing, even if they have little understanding of weaving or weaving software ( Chapman, 2005 ). Sustainable fashion technology is related to creative pattern cutting, which can reduce environmental impact. Zero-waste pattern cutting is making fabric using the predetermined width and length to minimize the fabric’s loss in the cutting stage ( Townsend and Mills, 2013 ). Zero-waste fashion can show new expressions while reducing or eliminating waste in product production by mixing creative design practices and zero-waste pattern cutting ( McQuillan, 2019 ). Applying this method requires intuition and experience. However, in recent years, innovative designs and technological progress have made it easier to adopt creative practices. Software such as CLO enables fast initial design creation and facilitates the development of highly innovative woven shapes by visualizing 2D patterns, 3D shapes, and waste generated during garment design ( McQuillan, 2019 ).

In this study, the zero-waste fashion approach also included cases in which technologies that did not affect a sustainable environment were utilized.

1. 3D technique: PRISM Squared swimwear, sportswear, underwear, and shapewear produced by a seamless 3D knitting technique are created with almost no loss of fabrics during the production process (Elle team, 2020).

2. Digital printing: Hoffman performs digital printing directly on finished sweaters to ensure that the loss of fabric caused by pattern matching will not occur ( Marius, 2020 ; Offman, 2021 ).

3. Lasers and robotics: Levis produced jeans in a way that is better for the environment by combining lasers and robotics ( Elle Fashion Team, 2020 ; Davis, 2021 ).

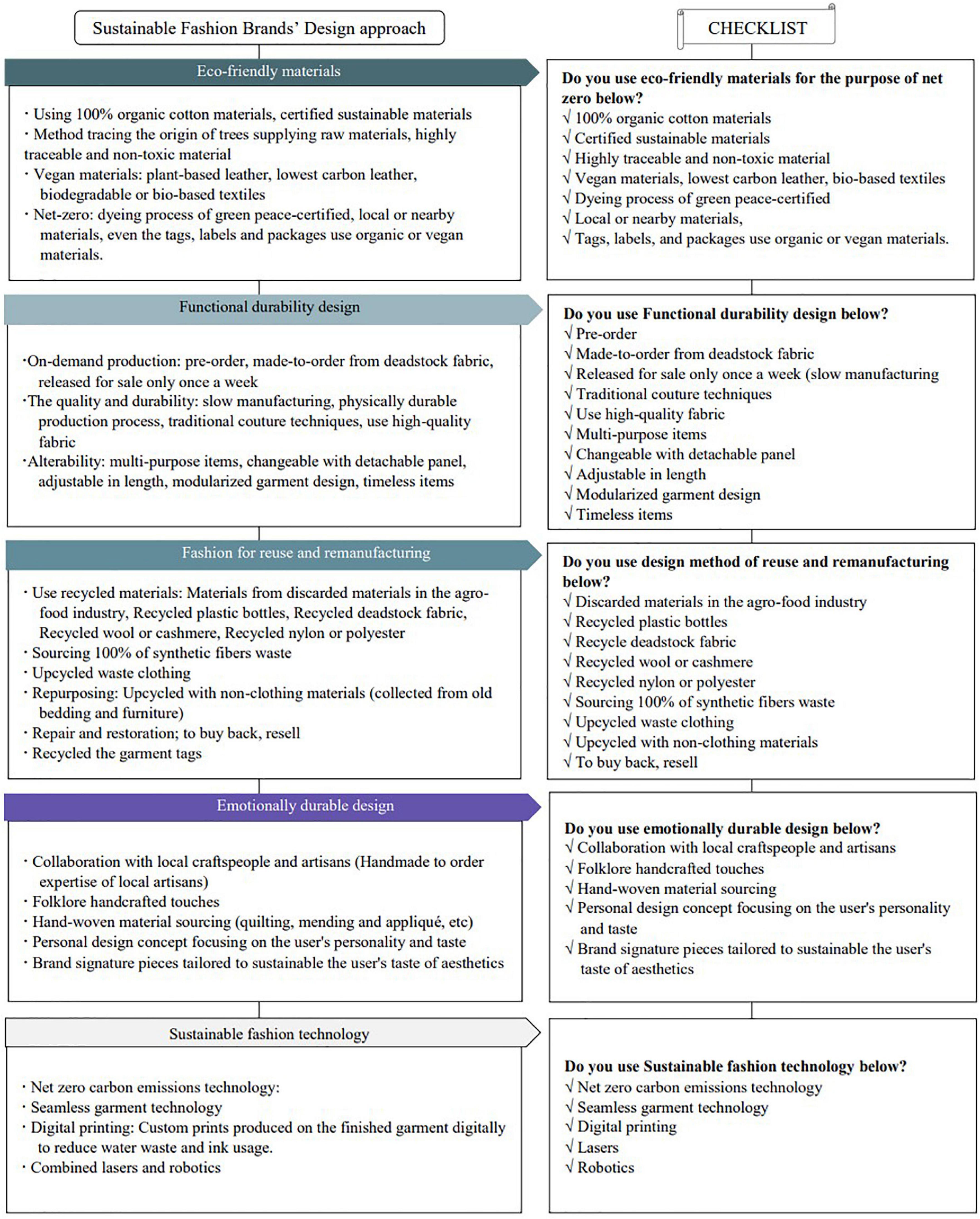

Checklist from the result of the case study

Figure 5 shows a summary of the specific methods for each design approach category, which can be applied in practical design in the early design phase of SFBs based on the experimental techniques derived from the case studies for each SFD approach category.

Figure 5. Representation methods by sustainable fashion brand (SFB) design approach category.

The interview was conducted in three stages. In the first stage, questions were about fashion designers and SFB practical experience, cognitions related to TBL of sustainability, and whether and how TBL performance was applied to the company. In the second stage, an interview was conducted to find out the current practical approach of the interviewees using the SFD approach checklist derived from the SFBs case study results that appeared in the world’s top popular fashion magazines. The third stage was an interview on whether the checklist can be used as a practical tool for a sustainable design approach. Eleven brands participated in interviews.

Experience related to running a sustainable fashion brand and triple bottom line of sustainability

Designers can have a significant impact on the environment by intervening early in the sustainable fashion industry supply chain. With this in mind, the first question was about knowledge of TBL and designer experience. The brands participating in the interviews ranged from micro-sized companies with one person to small- and medium-sized companies with fewer than ten employees. The duration of the SFB operation of the interviewees was between 2 and 12 years. Some of the interviewers were aware of the value and performance of the TBL of sustainability and able to properly explain the application cases in practice. The others could explain corporate SDGs, but misunderstood the TBL of sustainability. That is, most interviewees were aware of environmental values, whereas some had difficulty approaching economic and social values. In particular, they misunderstood the economic value of sustainable environmental development as the economic performance of the company. This is consistent with previous studies in which designers discussed inadequate knowledge about sustainability and the lack of time to acquire it ( Knight and Jenkins, 2009 ; Bovea and Pérez-Belis, 2012 ). The results support that tools for a sustainable design approach should be designed as effective learning mechanisms.

“From the social aspect of TBL, we actively hire women who have lost their careers to provide jobs for women who can be marginalized. From an environmental point of view, the use of recycled plastic bottles was actively introduced in all of the brand’s products, design, manufacturing method, and packing. We strive to reduce the impact of the environment through disposal, end-of-life treatment, which also contributes to sustainable environmental development and economic performance.” (Interviewee A)

This interviewee’s case was characteristic in that it aimed to expand the use of recycled plastic bottles. On the other hand, Interviewee D argued “to minimize the environmental impact, even plastic should not be used.”

Interviewee A and D had opposite views of sustainable development. In the report “Synthetics Anonymous” released by the Changing Markets Foundation (2021) , it is noted that downcycling plastic made from recycled plastic bottles, that is, clothing using recycled polyester, will eventually end up in landfill or incineration rather than circulating fashion. The use of PET bottles as a material for recycling is expected to be controversial in the future.

The role of designers is to create an opportunity to increase the sustainability of fashion design. Further, it is a critical change agent in sustainable fashion ( Niinimäki and Hassi, 2011 ). Most interviewees were aware of the importance of the designer’s role in attaining the value of sustainability. Interviewees A, B, C, D, and E discussed the importance of designers in reaching the value of sustainability because designers influence the life cycle of fashion products, and the design process is organically intertwined with all other areas. Interviewee I explained that a designer’s sense of design determined customers’ product selection and utilization. Moreover, they discussed the importance of design considering customer emotions and personal tastes to induce consumption of sustainable fashion products. Interviewees F and K stated that the role of designers is to convey the importance of sustainability to customers or boost sustainability in customer emotions and personal tastes. Through the interview results, designers can reflect on customer emotions and personal preferences in sustainable fashion products and exert influence throughout the design process to achieve sustainable goals. Designers can effectively implement sustainable fashion if there are tools that make the sustainable design approach more specific, practical, and easy to use.

Design approaches of sustainable fashion brands in Korea through the checklist

The interview on SFB’s approach to sustainable design practice in Korea was conducted by presenting a checklist derived from the case analysis results in the previous chapter. As a result of participating in the checklist, the SFD approach of the brands which participated in the interview mainly utilized “eco-friendly materials,” “functional durability design,” and “fashion for reuse and remanufacturing.” Some brands were new to or unfamiliar with the detailed expression methods of “emotionally durable design” and “sustainable fashion technology.” However, it is thought that it will be helpful for the expansion of sustainable design approaches in the future by realizing that the design process that is currently being implemented for customizing consumer tastes and the design inspired by their own culture belong to this area during the interview. The “eco-friendly materials” design approach is the design approach that most interviewees used, and there were various design expression methods. For example, Interviewee B used leather from the mulberry bark or cactus. Conversely, Interviewee D used sustainable materials, such as organic linen produced even on land unsuitable for grain production with low water consumption and pollution, and GOTS-certified organic cotton. Most of the brands interviewed chose green materials as a sustainable design approach, similar to a case study of SFB products presented by the world’s leading fashion magazines that are popular with the public. However, there was no mention of a method of tracing the origin of eco-friendly materials or tracking the use of eco-friendly materials at a short distance, which is a specific design approach shown in the results of the case study.

In the case study of fashion magazines, “functional durability design” presented specific design methods such as a pre-order method without stock, quality and design that can be worn over time, high-quality sewing, and a manual showing various styling with the few fashion items. Similarly, SFBs in Korea used manual finishing and preorder on-demand methods to ensure the robustness of their products and taught them various styling methods and easy repairs.

”As a company that produces sustainable bags and clothing, it enhances the solid finish with high-quality sewing using hand-sewn in the final finishing process.” (Interviewee B)

”We are adopting the slow business model as a seasonal, non-fashionable design method.” (Interviewee C)

“By connecting the small-volume production method of preorder with brand membership, we create a customer group with high loyalty to the brand. This avoids unnecessary production, resulting in environmental and economic performance. It gives advice to consumers on styling when they cannot use the purchased product and provides customers with information on laundry and care. Buying well-made products from good materials will extend the lifespan of your clothes.” (Interviewee K)

In the case study, “fashion for reuse and remanufacturing” was shown to be resourcing sustainable yarns from waste, or redesigning and repurposing. That is, recycled fishing nets, pieces of cloth, fabrics resourcing from plastic bottles, vintage clothing, outworn bedding, etc., were recycled and redesigned, and the original use of the material was changed. Similarly, in Korea’s SFB interviews, “fashion for reuse and remanufacturing” was found to use resourced materials from waste plastic bottles, use scrap or stock fabrics, or recycle discarded clothing. Among the design expression methods shown in the case study results, most expression methods were used by the brands participating in the interviews, except for recycling waste generated in the agro-food industry as a material.

“In Korea, the domestic waste plastic bottle market is active and has been developed using various materials. So, companies who want to use it can easily purchase it.” (Interviewee A)

“Among the clothes purchased from our brand, we collected the clothes the customer wanted to discard and upcycled it in the direction the customer wanted. The customer liked it very much.” (Interviewee K)

“We are producing hand-knitted handbags by collecting materials thrown away during the clothing-making process.” (Interviewee G)