Five Current Trending Issues in Special Education

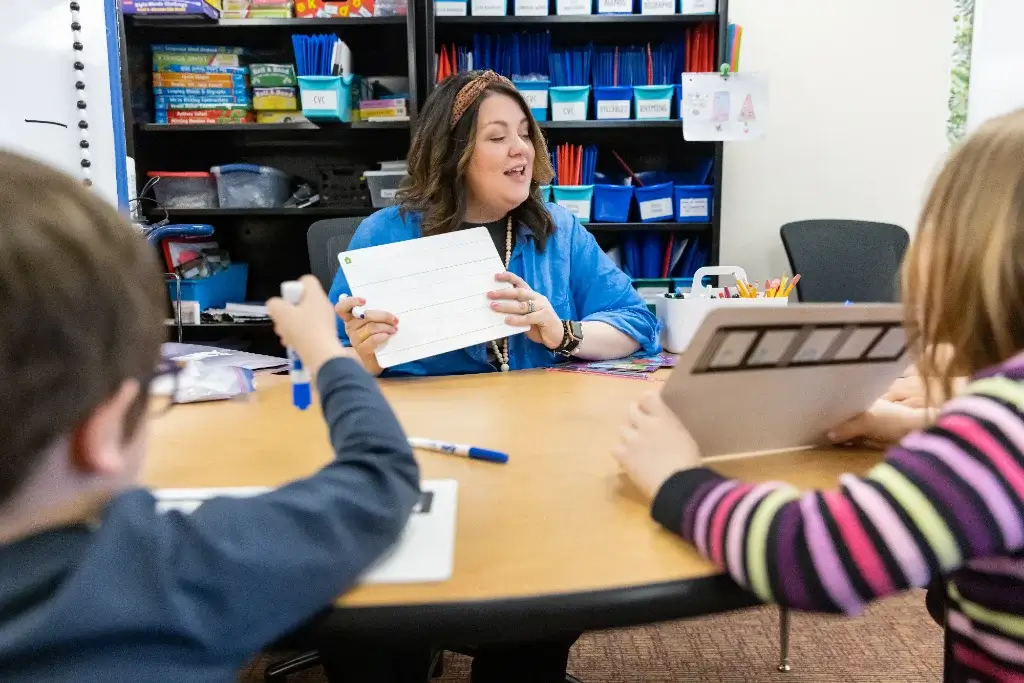

The majority of students with disabilities is now served in general education classrooms as we embrace inclusive practices in our schools. The primary dynamics of the general ed classroom is changing due to these inclusive measures. Continuing scarcity of special education teachers and movement toward team teaching or co-teaching impact the process that districts approach special education as well. The lines are blurring in diagnosis, pedagogy, and instruction between a general education classroom and special education approaches to instruction. As mentioned, both here and in previous blog posts, the classroom is changing. The focus of educators is becoming more about supporting students who face trauma, catastrophic events, multiple disabilities, and special talents, all without the benefit of a clear diagnosis. This is leaving general education classroom teachers responsible for a greater need for understanding of student learning that falls outside the realm of a worksheet and basal reader. Let’s take a deeper look into some of the top five issues that are currently trending in the world of special education.

As technology continues to substantially alter the classroom, students with Individualized Education Programs (IEPs) are especially targeted for extra support. By leveraging technology, classroom instruction can be enhanced with individual learning occasions, which allows teachers greater flexibility for differentiation in instruction through blended learning opportunities and the variety of Web-based, evidence-based practices. No longer are students stuck in a classroom they don’t understand, learning at a pace they can’t keep up with.

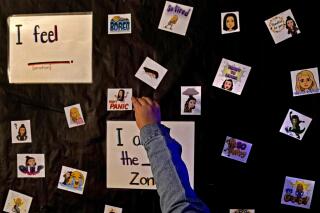

Trauma-Informed Teaching

Students and teachers are often faced with dire situations far outside their control. Managing these situations and addressing the emotional impact can make day-to-day instruction feel trivial in comparison. How do you face a traumatic event and continue to learn fractions? This school year, we have seen flooding, fires, tornados, mudslides, polar vortexes, and hurricanes affect communities. Surely these should be considered traumatic events! The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) counts natural disasters as traumatic events. The NCTSN defines a traumatic event as a “frightening, dangerous, or violent event that poses a threat to a child’s life or bodily integrity.” Each student reacts to trauma in his or her own way. While there is no clear-cut set of cues to spot, there are many resources describing possible signs of trauma to keep an eye out for. According to the NCTSN, there is a variety of behaviors that you might observe in students affected by trauma.

These students are dealing with issues that are far outside of the classroom, yet impact learning. How students deal is unique to them, but they do not qualify for special education services immediately. Trauma-screening resources are available for educators to help providers identify children’s and families’ needs. Knowing the signs and resources is a first step to managing a general education classroom with these special students. Students who face trauma certainly require special accommodations. Their world and work are significantly impacted by forces outside of their control. There are behaviors we can look for and resources we can put in place, but as educators, and often participants of the same catastrophic events, we need to be aware of the resources and act as part of the solution, not the only solution.

Homelessness

Educators are well aware of the impact of poverty on students and learning. But, do you know how many of your students are homeless? This is a challenge being faced by more students than you might expect, and under new Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) requirements, increased focus is being placed on monitoring the academic growth of this specific population. Again, these students fit outside the realm of traditionally acknowledged special education students. For homeless students, the classroom could be the one safe, stable place in their day-to-day lives, an important tether to the safety and security of routine and, perhaps most critically, an essential support in the journey out of poverty and into a better situation. These students are being forced to deal with significant, difficult, and interrelated challenges outside of the classroom that inevitably impact academic performance and the ability to participate in instruction.

At this point, it should come as no surprise that for children already identified as needing special education services, the stresses of homelessness can exacerbate learning problems. After all, transitions are often hard for children with exceptionalities—can you imagine anything more transitional than being without a consistent place to sleep every night? However, not all homeless students have gone through the evaluation process (or need to), so providing educational support and resources is not an option, but consider how difficult it must be for general education students to deal with the uncertainty of circumstances and continue to maintain focus on classroom instruction. Read our full blog post on strategies for educators and resources for you to connect your students .

Twice-Exceptional Students

One of the challenges teachers face, in addition to everything else on their plates, is providing material that is appropriate in content and grade level for every child. When discussing students with special needs, this can often refer to age-appropriate and skill-appropriate content. There is another population of students that must be reviewed with an eye toward their special needs. These children often get lost, and because of their talents, these students often find themselves hiding in the “average” populations. In education, students who qualify for gifted programs as well as special education services are described as “twice-exceptional” learners. Twice-exceptional (or “2E”) students demonstrate significantly above-average abilities in certain academic areas but also show special educational needs, such as ADHD, learning disabilities, or autism spectrum disorder. Because their giftedness often masks their special needs, or vice versa, they are sometimes labeled as "lazy" or "underperforming," even though that is not the case.

Educators recognize that 2E students exist—often in the shadows—of the classroom. However, the real challenge is how to accurately identify these students, understand the challenges that they face, and implement whole-child-based strategies to best support them. Savvy teachers are now learning how to allow these students to experience the same opportunities available for gifted students, learn in ways that highlight their strengths, and address their challenges at the same time.

Parental Support

We have talked at great length about some of the issues that students and teachers are facing within special education. Many of these topics are outside of the identification of diagnosis and recognition of special ed disabilities and guaranteed services. However, one common theme we have not discussed is the approach that must be considered when meeting with parents. You, as their child’s teacher, may be the very first person to indicate that there is an issue with their precious baby. Starting the conversation is hard—you can be met with tears or terror. The main thing to consider is that this is their child and that you only know one small piece of the puzzle. It is important from the beginning that you are part of the one unified team that supports students in the best way possible. At the end of the day, you and your students’ parents want the best for the children, and it’s important to remember that. You play an important role in students’ lives, so make sure that you’re making your voice heard, but be sure that you’re listening to what parents have to say. Keep children’s best interests in mind. Remember, you are an advocate, but they are the parents. Create a plan that you can all agree on—one that will find students where they are.

There is more legislation supporting students with special needs as being part of the general education classroom. Students with special needs are part of the general populations of their grade levels both in testing and in instruction. ESSA has clear limits on which/how many students can be classified for assessments (high-stakes exams), and the assessment world is moving toward the growth mindset, which celebrates a growth over final scores. It’s a position where special education teachers have lived for years.

Next Steps for Educators

Classroom teachers are amazing. It’s as simple as that. More and more students, either diagnosed or facing matters that are outside the standards of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) categories of special ed, are showing up in the general education classroom. This puts significant pressures on general education teachers. Continuing education, individualized instruction, and flexibility are paramount for these teachers. Legislation calls for some of these previously underrepresented populations to be accountable in high-stakes testing, without IEPs or provisions. This means that classroom teachers must be aware of how best to teach everyone in the classroom and not turn over the keys to a special education teacher. Teachers with special education certification may not be there or may be spread across many classrooms. Communication is key. Work with other teachers, parents, and students to create an environment of shared practice and success. Be sensitive to the journey your students are on; it may have hidden barriers we might not know about.

Get the latest education insights sent directly to your inbox

Subscribe to our knowledge articles.

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

Many kids are struggling. Is special education the answer?

FILE - A student visits a sensory room at Williams Elementary School, on Nov. 3, 2021, in Topeka, Kan. Schools contending with soaring student mental health needs and other challenges have been struggling to determine just how much the pandemic is to blame. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

- Copy Link copied

The COVID-19 pandemic sent Heidi Whitney’s daughter into a tailspin.

Suddenly the San Diego middle schooler was sleeping all day and awake all night. When in-person classes resumed, she was so anxious at times that she begged to come home early, telling the nurse her stomach hurt.

Whitney tried to keep her daughter in class. But the teen’s desperate bids to get out of school escalated. Ultimately, she was hospitalized in a psychiatric ward, failed “pretty much everything” at school and was diagnosed with depression and ADHD.

As she started high school this fall, she was deemed eligible for special education services, because her disorders interfered with her ability to learn, but school officials said it was a close call. It was hard to know how much her symptoms were chronic or the result of mental health issues brought on by the pandemic, they said.

“They put my kid in a gray area,” said Whitney, a paralegal.

Schools contending with soaring student mental health needs and other challenges have been struggling to determine just how much the pandemic is to blame. Are the challenges the sign of a disability that will impair a student’s learning long term, or something more temporary?

It all adds to the desperation of parents trying to figure out how best to help their children. If a child doesn’t qualify for special education, where should parents go for help?

“I feel like because she went through the pandemic and she didn’t experience the normal junior high, the normal middle school experience, she developed the anxiety, the deep depression and she didn’t learn. She didn’t learn how to become a social kid,” Whitney said. “Everything got turned on its head.”

Schools are required to spell out how they will meet the needs of students with disabilities in Individualized Education Programs, and the demand for screening is high. Some schools have struggled to catch up with assessments that were delayed in the early days of the pandemic. For many, the task is also complicated by shortages of psychologists .

To qualify for special education services, a child’s school performance must be suffering because of a disability in one of 13 categories, according to federal law. They include autism, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, learning disabilities like dyslexia, developmental delays and “emotional disturbances.”

It’s important not to send children who might have had a tough time during the pandemic into the special education system, said John Eisenberg, the executive director of the National Association of State Directors of Special Education.

“That’s not what it was designed for,” he said. “It’s really designed for kids who need specially designed instruction. It’s a lifelong learning problem, not a dumping ground for kids that might have not got the greatest instruction during the pandemic or have major other issues.”

In the 2020-2021 school year, about 15% of all public school students received special education services under federal law, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

Among kids ages 6 and older, special education enrollment rose by 2.4% compared with the previous school year, according to federal data. The figures also showed a large drop in enrollment for younger, preschool-age students, many of whom were slow to return to formal schooling. The numbers varied widely from state to state. No data is available yet for last year.

While some special education directors worry the system is taking on too many students, advocates are hearing the opposite is happening, with schools moving too quickly to dismiss parent concerns.

Even now, some children are still having evaluations pushed off because of staffing shortages , said Marcie Lipsitt, a special education advocate in Michigan. In one district, evaluations came to a complete halt in May because there was no school psychologist to do them, she said.

When Heather Wright approached her son’s school last fall seeking help with the 9-year-old’s outbursts and other behavioral issues, staff suggested private testing. The stay-at-home mom from Sand Creek, Michigan, called eight places. The soonest she could get an appointment was in December of this year — a full 14 months later.

She also suspects her 16-year-old has a learning disability and is waiting for answers from the school about both children.

“I hear a lot of: ‘Well, everyone’s worse. It’s not just yours,’” she said. “Yeah, but, like, this is my child and he needs help.”

It can be challenging to tease out the differences between problems that stem directly from the pandemic and a true disability, said Brandi Tanner, an Atlanta-based psychologist who has been deluged with parents seeking evaluations for potential learning disabilities, ADHD and autism.

“I’m asking a lot more background questions about pre-COVID versus post-COVID, like, ‘Is this a change in functioning or was it something that was present before and has just lingered or gotten worse?’” she said.

Sherry Bell, a leader in the Department of Exceptional Children at Charleston County School District in South Carolina, said she is running into the issue as well.

“In my 28 years in special education, you know, having to rule out all of those factors is much more of a consideration than ever before, just because of the pandemic and the fact that kids spent all of that time at home,” said Bell.

The key is to have good systems in place to distinguish between a student with a lasting obstacle to learning and one that missed a lot of school because of the pandemic, said Kevin Rubenstein, president-elect of the Council of Administrators of Special Education.

“Good school leaders and great teachers are going to be able to do that,” he said.

The federal government, he noted, has provided vast amounts of COVID relief money for schools to offer tutoring, counseling and other support to help students recover from the pandemic.

But advocates worry about consequences down the line for students who do not receive the help they might need. Kids who slip through the cracks could end up having more disciplinary problems and diminished prospects for life after school, said Dan Stewart, the managing attorney for education and employment for the National Disability Rights Network.

Whitney, for her part, said she is relieved her daughter is getting help, including a case manager, as part of her IEP. She also will be able to leave class as needed if she feels anxious.

“I realize that a lot of kids were going through this,” she said. “We just went through COVID. Give them a break.”

Sharon Lurye in New Orleans contributed to this report. The Associated Press education team receives support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. The AP is solely responsible for all content.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Students with disabilities have a right to qualified teachers — but there's a shortage

Lee V. Gaines

This is the first in a two-part series on the special education teacher shortage. You can read part two here .

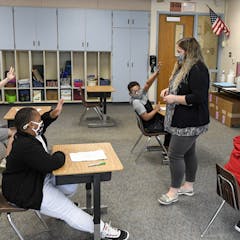

At the beginning of the school year, when Becky Ashcraft attended an open house at her 12-year-old daughter's school, she was surprised to find there was no teacher in her daughter's classroom – just a teacher's aide.

"They're like, 'Oh, well, she doesn't have a teacher right now. But, you know, hopefully, we'll get one soon,' " Ashcraft recalls.

Schools are struggling to hire special education teachers. Hawaii may have found a fix

Ashcraft's daughter attends a public school in northwest Indiana that exclusively serves students with disabilities. She is on the autism spectrum and doesn't speak. Without an assigned teacher, it was difficult for Ashcraft to know what her daughter did everyday.

"I wonder what actually kind of education she was receiving," Ashcraft says.

Ashcraft's daughter spent the entire fall semester without an assigned teacher. One other parent at the school told NPR they were in the same position. Ashcraft says the principal told her they were trying to hire someone, but it was difficult to find qualified candidates.

After Months Of Special Education Turmoil, Families Say Schools Owe Them

The school would not confirm to NPR that Ashcraft's daughter had no teacher, but a spokesperson did say the school has used substitutes to provide special education services amid the shortage of qualified educators.

The federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act guarantees students with disabilities access to fully licensed special educators. But as Ashcraft learned, those teachers can be hard to find. In 2019, 44 states reported special education teacher shortages to the federal government. This school year, that number jumped to 48.

When schools can't find qualified teachers, federal law allows them to hire people who aren't fully qualified so long as they're actively pursuing their special education certification. Indiana, California, Virginia and Maryland are among the states that offer provisional licenses to help staff special education classrooms.

It's a practice that concerns some special education experts. They worry placing people who aren't fully trained for the job in charge of classrooms could harm some of the most vulnerable students.

But given the lack of qualified special education teachers, Ashcraft says she wouldn't mind if her daughter's teacher wasn't fully trained yet.

"Let them work towards that [license], that's wonderful," she says. "But, you know, I guess at this point, you know, we're happy to take anybody."

The case against provisional special education licenses

Jacqueline Rodriguez, with the American Association of Colleges for Teacher Education, is alarmed at the number of provisional licenses issued to unqualified special education teachers in recent years — even if those teachers are actively working toward full licensure.

"The band aid has been, let's put somebody who's breathing in front of kids, and hope that everybody survives," she says. Her organization focuses on teacher preparation, and has partnered with higher education institutions to improve recruitment of special educators.

She worries placing untrained people at the helm of a classroom, and in charge of Individualized Education Programs, is harmful for students.

"This to me is like telling somebody there's a dearth of doctors in neurosurgery, so we would love for you to transition into the field by giving you the opportunity to operate on people while you're taking coursework at night," Rodriguez says.

She admits it's a provocative analogy, but says teaching is a profession that requires intensive coursework, evaluation and practice. "And unless you can demonstrate competency, you have no business being a teacher."

One district is building a special education teacher pipeline

Shaleta West had zero teaching experience when she was hired as a special educator by Elkhart Community Schools, a district in northern Indiana.

She says her first couple weeks in the classroom were overwhelming.

"It was very scary because, you know, I know kids, yes. But when you're trying to teach kids it's a whole other ball game. You can't just play around with them and talk to them and chit chat. You have to teach."

The Coronavirus Crisis

Families of children with special needs are suing in several states. here's why..

Her district is helping her work toward her certification at nearby Indiana University South Bend. Elkhart Community Schools pays West's tuition and, in exchange, West has agreed to work for the district for five years.

The district also provides West with a mentor — a seasoned special educator who answers questions, offers tips and looks over the complicated paperwork that's legally required for students with disabilities.

West says she would have been lost without the mentorship and the university classes.

"To be honest, I don't even know if I would have stayed," she explains.

"I knew nothing. I came in without any prior knowledge to what I needed to do on a daily basis."

Administrator Lindsey Brander oversees the Elkhart schools program that supports West. She says the program has produced about 30 fully qualified special educators over the past four years. This year, it's serving about 10 special educators, all on provisional licenses.

"We are able to recruit our own teachers and train them specifically for our students. So the system is working," Brander explains. The challenge, she says, is that it's become increasingly difficult for the district to find people to participate in the program.

And even with a new teacher pipeline in place, the district still has 24 special education vacancies.

Brander would prefer if all the district's special education teachers were fully qualified the first day they set foot in a classroom.

"But that's not reality. That's not going to happen. Until we fix some of the structural challenges that we have in education, this is how business is done now. This is life in education," she says.

How high teacher turnover impacts students

The structural issues contributing to the special educator shortage include heavy workloads and relatively low pay. At Elkhart schools, for example, new special education teachers with bachelor's degrees receive a minimum salary of $41,000, according to district officials.

Desiree Carver-Thomas, a researcher with the Learning Policy Institute, says low compensation and long workdays can lead to high turnover, especially in schools that serve students of color and children from low-income households. And when special education teachers leave the profession, the cycle continues.

"Because when turnover rates are so high, schools and districts they're just trying to fill those positions with whomever they can find, often teachers who are not fully prepared," Carver-Thomas says.

Hiring unprepared teachers can also contribute to high turnover rates, according to Carver-Thomas' research . And it can impact student outcomes.

Schools Say They Have To Do Better For Students With Disabilities This Fall

As NPR has reported , Black students and students with disabilities are disciplined and referred to law enforcement at higher rates than students without disabilities. Black students with disabilities are especially vulnerable; federal data shows they have the highest risk for suspension among all students with disabilities.

"That may be more common when teachers don't have the tools and the experience and the training to respond appropriately," Carver-Thomas says.

Schools and families have to make do

The solution to the special educator shortage isn't simple. Carver-Thomas says it will require schools, colleges and governments to work together to boost teacher salaries and improve recruitment, preparation, working conditions and on-the-job support.

In the meantime, schools and families will have to make do.

In January, Becky Ashcraft learned her northwest Indiana school had found a teacher for her daughter's classroom.

She says she's grateful to finally have a fully licensed teacher to tell her about her daughter's school day. And she wishes the special educators that families like hers rely on were valued more.

"We've got to be thankful for the people that do this work," she says.

Nicole Cohen edited this story for broadcast and for the web.

Articles on Special education

Displaying 1 - 20 of 40 articles.

Navigating special education labels is complex, and it matters for education equity

Laura Perez Gonzalez , Toronto Metropolitan University ; Henry Parada , Toronto Metropolitan University , and Veronica Escobar Olivo , Toronto Metropolitan University

Schools have a long way to go to offer equitable learning opportunities, especially in French immersion

Diana Burchell , University of Toronto ; Becky Xi Chen , University of Toronto ; Elizabeth Kay-Raining Bird , Dalhousie University , and Roksana Dobrin-De Grace , Toronto Metropolitan University

Daily report cards can decrease disruptions for children with ADHD

Gregory Fabiano , Florida International University

Achieving full inclusion in schools: Lessons from New Brunswick

Melissa Dockrill Garrett , University of New Brunswick and Andrea Garner , University of New Brunswick

Pandemic shut down many special education services – how parents can help their kids catch up

Mitchell Yell , University of South Carolina

Police response to 5-year -old boy who left school was problematic from the start

Elizabeth K. Anthony , Arizona State University

Decades after special education law and key ruling, updates still languish

Charles J. Russo , University of Dayton

ADHD: Medication alone doesn’t improve classroom learning for children – new research

William E. Pelham Jr. , Florida International University

Students of color in special education are less likely to get the help they need – here are 3 ways teachers can do better

Mildred Boveda , Penn State

Students with disabilities are not getting help to address lost opportunities

John McKenna , UMass Lowell

5 tips to help preschoolers with special needs during the pandemic

Michele L. Stites , University of Maryland, Baltimore County and Susan Sonnenschein , University of Maryland, Baltimore County

Children on individual education plans: What parents need to know, and 4 questions they should ask

Tori Trajanovski , York University, Canada

3 ways music educators can help students with autism develop their emotions

Dawn R. Mitchell White , University of South Florida

‘Generation C’: Why investing in early childhood is critical after COVID-19

David Philpott , Memorial University of Newfoundland

Federal spending covers only 8% of public school budgets

David S. Knight , University of Washington

Coronavirus: Distance learning poses challenges for some families of children with disabilities

Jess Whitley , L’Université d’Ottawa/University of Ottawa

How lockdown could affect South Africa’s children with special needs

Athena Pedro , University of the Western Cape ; Dr Bronwyn Mthimunye , University of the Western Cape , and Ella Bust , University of the Western Cape

5 tips to help parents navigate the unique needs of children with autism learning from home

Amanda Webster , University of Wollongong

Ontario’s high school e-learning still hasn’t addressed students with special needs

Pam Millett , York University, Canada

Excluded and refused enrolment: report shows illegal practices against students with disabilities in Australian schools

Kathy Cologon , Macquarie University

Related Topics

- Children with disability

- Inclusive education

- Special education services

- Special needs

Top contributors

Associate Professor, Tarleton State University

Professor of participation and learning support, The Open University

Senior Lecturer, Department of Educational Studies, Macquarie University

Senior Research Fellow, University of Warwick

Associate Professor of Economics, Carleton University

Assistant Professor of Special Education, Boston University

Assistant Professor of Special Education, UMass Boston

Assistant Professor of Economics, The University of Texas at Austin

Assistant Professor of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies, University of Memphis

Assistant Professor, Nazarbayev University

Professor of Educational Psychology and Special Educational Needs, University of Exeter

PhD Researcher, Swansea University

Associate Professor of Education, Elon University

Associate Professor, Faculty of Law, University of Technology Sydney

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

What federal education data shows about students with disabilities in the U.S.

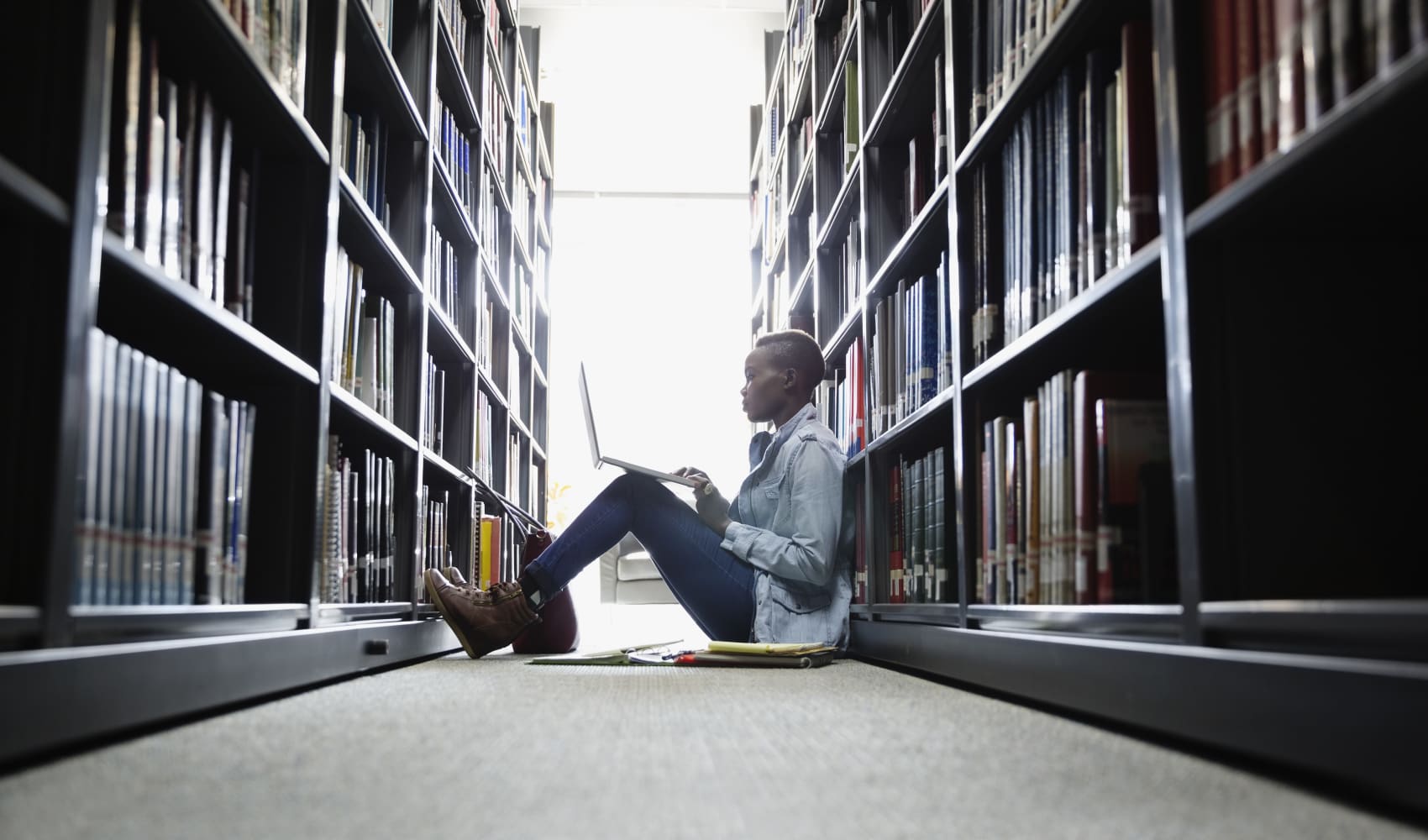

Public K-12 schools in the United States educate about 7.3 million students with disabilities – a number that has grown over the last few decades. Disabled students ages 3 to 21 are served under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) , which guarantees them the right to free public education and appropriate special education services.

For Disability Pride Month , here are some key facts about public school students with disabilities, based on the latest data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) .

July is both Disability Pride Month and the anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act. To mark these occasions, Pew Research Center used federal education data from the National Center for Education Statistics to learn more about students who receive special education services in U.S. public schools.

In this analysis, students with disabilities include those ages 3 to 21 who are served under the federal Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) . Through IDEA, children with disabilities are guaranteed a “free appropriate public education,” including special education and related services.

The 7.3 million disabled students in the U.S. made up 15% of national public school enrollment during the 2021-22 school year. The population of students in prekindergarten through 12th grade who are served under IDEA has grown in both number and share over the last few decades. During the 2010-11 school year, for instance, there were 6.4 million students with disabilities in U.S. public schools, accounting for 13% of enrollment.

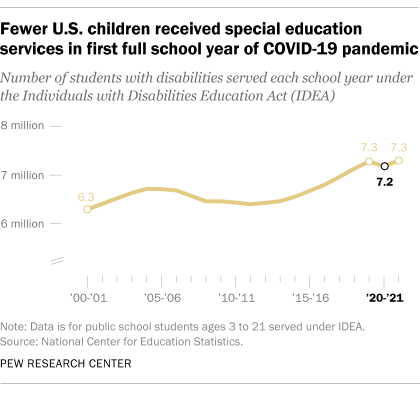

The number of students receiving special education services temporarily dropped during the coronavirus pandemic – the first decline in a decade. Between the 2019-20 and 2020-21 school years, the number of students receiving special education services decreased by 1%, from 7.3 million to 7.2 million. This was the first year-over-year drop in special education enrollment since 2011-12.

The decline in students receiving special education services was part of a 3% decline in the overall number of students enrolled in public schools between 2019-20 and 2020-21. While special education enrollment bounced back to pre-pandemic levels in the 2021-22 school year, overall public school enrollment remained flat.

These enrollment trends may reflect some of the learning difficulties and health concerns students with disabilities and their families faced during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic , which limited or paused special education services in many school districts.

Many school districts struggle to hire special education professionals. During the 2020-21 school year, 40% of public schools that had a special education teaching vacancy reported that they either found it very difficult to fill the position or were not able to do so.

Foreign languages (43%) and physical sciences (37%) were the only subjects with similarly large shares of hard-to-fill teaching vacancies at public schools that were looking to hire in those fields.

While the COVID-19 pandemic called attention to a nationwide teacher shortage , special education positions have long been among the most difficult for school districts to fill .

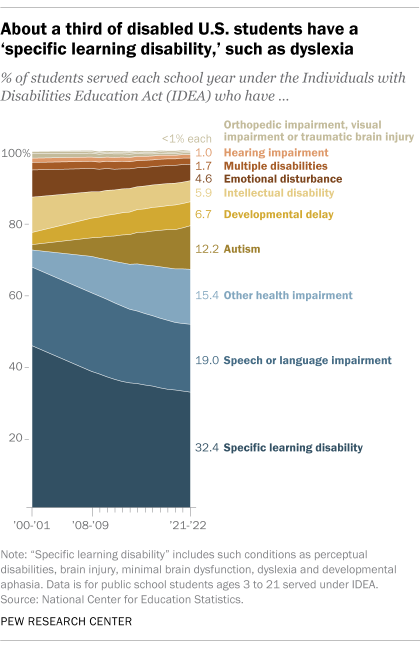

The most common type of disability for students in prekindergarten through 12th grade involves “specific learning disabilities,” such as dyslexia. In 2021-22, about a third of students (32%) receiving services under IDEA had a specific learning disability. Some 19% had a speech or language impairment, while 15% had a chronic or acute health problem that adversely affected their educational performance. Chronic or acute health problems include ailments such as heart conditions, asthma, sickle cell anemia, epilepsy, leukemia and diabetes.

Students with autism made up 12% of the nation’s schoolchildren with disabilities in 2021-22, compared with 1.5% in 2000-01. During those two decades, the share of disabled students with a specific learning disability, such as dyslexia, declined from 45% to 32%.

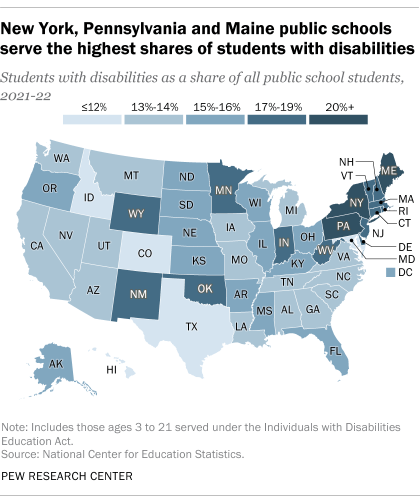

The percentage of students receiving special education services varies widely across states. New York serves the largest share of disabled students in the country at 20.5% of its overall public school enrollment. Pennsylvania (20.2%), Maine (20.1%) and Massachusetts (19.3%) serve the next-largest shares. The states serving the lowest shares of disabled students include Texas and Idaho (both 11.7%) and Hawaii (11.3%).

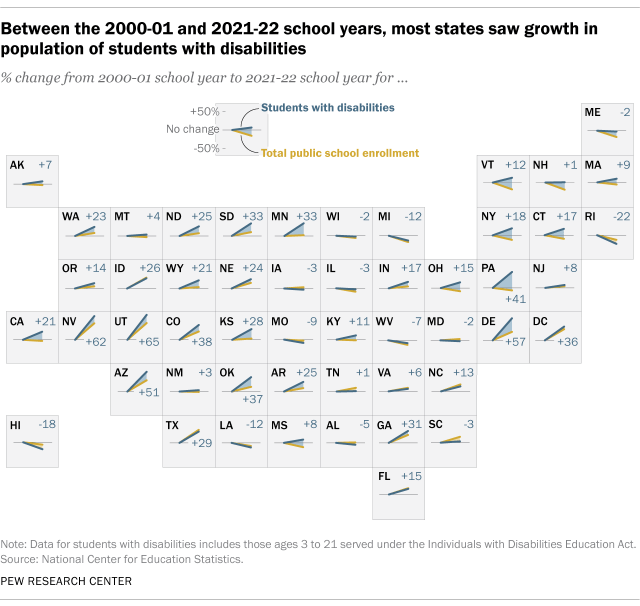

Between the 2000-01 and 2021-22 school years, all but 12 states experienced growth in their disabled student populations. The biggest increase occurred in Utah, where the disabled student population rose by 65%. Rhode Island saw the largest decline of 22%.

These differences by state are likely the result of inconsistencies in how states determine which students are eligible for special education services and challenges in identifying disabled children.

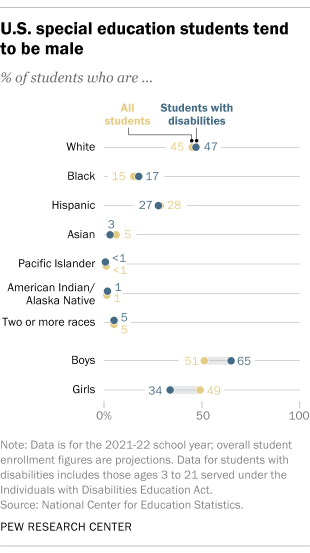

The racial and ethnic makeup of the nation’s special education students is similar to public school students overall, but there are differences by sex. About two-thirds of disabled students (65%) are male, while 34% are female, according to data from the 2021-22 school year. Overall student enrollment is about evenly split between boys and girls.

Research has shown that decisions about whether to recommend a student for special education may be influenced by their school’s socioeconomic makeup, as well as by the school’s test scores and other academic markers.

Note: This is an update of a post originally published April 23, 2020.

Katherine Schaeffer is a research analyst at Pew Research Center

Most Americans think U.S. K-12 STEM education isn’t above average, but test results paint a mixed picture

About 1 in 4 u.s. teachers say their school went into a gun-related lockdown in the last school year, about half of americans say public k-12 education is going in the wrong direction, what public k-12 teachers want americans to know about teaching, what’s it like to be a teacher in america today, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

The Current State of Special Education in the U.S.

The term “special” is typically used to describe something that is better or greater than the average. In terms of education, however, the term is often used to describe students who are different or differently abled. Special education focuses on helping children with disabilities learn and, just as every student is different, so are the various approaches to special education.

Parents and teachers have always had their work cut out for them when it comes to educating and caring for special needs students, but the COVID-19 pandemic has created new challenges that may last for years to come. In this article, we’ll discuss the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on special education and provide useful information for both parents and teachers.

What is Special Education?

The term “special education” generally refers to a set of services provided to students who have unique learning needs. In terms of federal law, according to the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), however, special education is defined as: “Specially designed instruction, at no cost to parents, to meet the unique needs of a child with a disability.”

In order to qualify for special education services, students must have an identified disability that affects their ability to learn. Eligible disabilities may include the following:

- Intellectual disabilities

- Speech or language impairment

- Hearing impairment

- Visual impairment

- Serious emotional disturbance

- Traumatic brain injury

- Orthopedic impairments

- Autism spectrum disorder

- Developmental delay

- Specific learning disabilities

Federal law requires schools to provide an appropriate education for all of their students with disabilities, regardless their disability or its severity. It also requires that six principles be provided to all students who qualify for special education services. These principles include the following:

- Free and Appropriate Public Education (FAPE ) – This principle states that all children with disabilities are entitled to a public education (at no cost) that is designed to meet the child’s individual needs. Students should be provided access to the general education curriculum and receive services in accordance with their IEP.

- Nondiscriminatory Identification and Evaluation – Public schools are required to use nonbiased methods to identify students with disabilities to ensure that there is no discrimination based on race, culture, or native language. Evaluation instruments must use the child’s native language.

- Individualized Education Program (IEP ) – This is a document that forms the foundation of special education, describing in detail the services to be provided to each individual student. It includes a description of the student’s current academic level and information on how the student’s disability affects their performance. It also outlines the adaptations and accommodations that are to be made along with learning goals and objectives for the year.

- Least Restrictive Environment (LRE ) – This describes the setting in which students with disabilities receive special education services. Generally speaking, children will be educated alongside students without disabilities as much as is appropriate. It may include part- or full-time special education in a resource room, a self-contained classroom, or community setting.

- Parent Participation – Parents have the right to be a member of any group that makes decisions regarding their child’s placement and LRE. They also have the right to access planning and evaluation materials and should be invited to attend IEP meetings.

- Due Process Safeguards – These are the protections given to children and their parents under IDEA. Safeguards may include obtaining parental consent for placement, confidentiality of the child’s records, independent evaluation (at no cost to the parent), and due process hearings in times when the school and the parent may disagree.

Because every child is unique, special education is not a “one size fits all” approach. Furthermore, federal law requires that children who receive special education spend as much time as possible in the same classrooms as other children. This requires parents and teachers to be involved in the student’s education to ensure they learn at an appropriate rate.

The Impact of the Pandemic on Special Needs Students

According to data collected by the Pew Research Center , there were nearly 7 million disabled students in the United States at the end of the 2017-18 school year. This group of special needs students has grown 11% since the 2000-01 school year. While the IDEA guarantees a certain quality of education for disabled students aged 3 to 21, the COVID-19 pandemic has created some unique challenges that won’t soon be overcome. Millions of students across the country shifted to online learning and the transition was particularly challenging for special needs students.

A survey of Americans aged 18 and older revealed that disabled Americans feel less comfortable using technology than their non-disabled counterparts. Additionally, disabled adults are less likely to express a high level of confidence in their ability to use the Internet as well as other communication devices (39% versus 65% of all adults). Compared to 8% of non-disabled adults, 23% of disabled adults say they never go on the Internet at all.

If disabled adults struggle to such a significant degree with technology, what does it mean for children with disabilities?

Many parents of disabled children find that maintaining a structured routine helps. Unfortunately, the chaos of the COVID-19 pandemic destroyed existing structures for special needs students both in-school and at-home. With the majority of schools transitioning to remote learning, it has fallen on the parents to establish the kind of routine their children would have normally had in school. Like most parents of school-age children, the parents of special needs children have undergone a period of trial-and-error to find out which methods work and which do not.

It wasn’t just parents who struggled, however. When schools first closed down, the federal government declared that it wouldn’t offer any special education waivers. Essentially, that meant that everything stipulated under IDEA was still in place, despite the increased difficulty schools faced in implementing it.

Some states made their own adjustments like the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (formerly the Massachusetts Department of Education). They decided that schools could provide a modification to their IEPs in the form of a remote learning program that was to be submitted to families in writing. Unlike the traditional IEP, however, these remote learning plans didn’t require a sign-off from parents. Unfortunately, many schools followed a similar trajectory in failing to provide services to special needs students if they couldn’t do it in the same way as regular students.

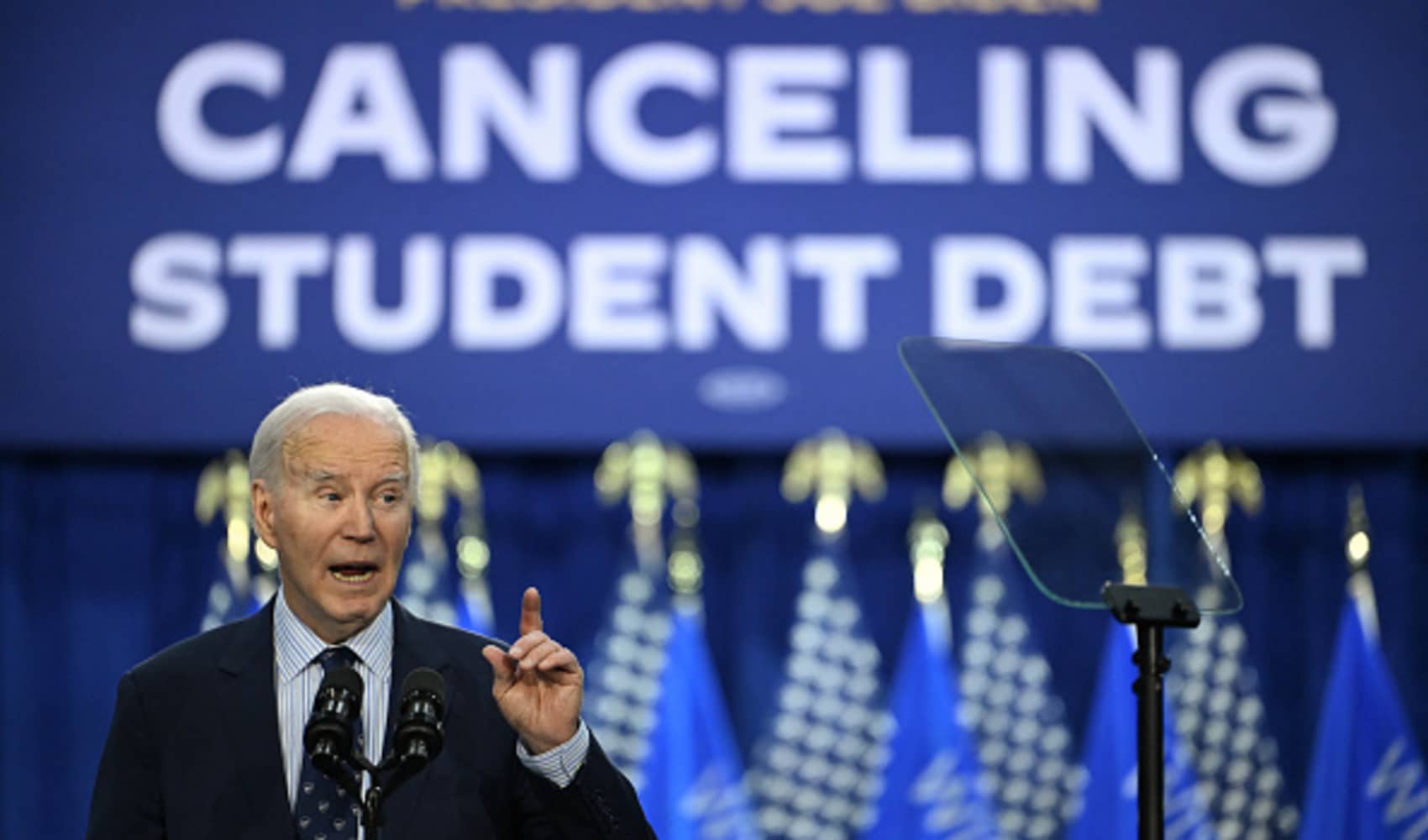

Students who were new to the special education system may have faced even greater challenges. Schools are required to evaluate special needs children within 30 school days and to meet with the family after another 15 days. During the spring quarantine, however, schools did little or no testing which has created a huge backlog. Not only have these students missed out on these evaluations, but they’ve missed out on months of special education services.

Under IDEA, special needs students are entitled to these services which means families are entitled to compensatory services for the special education students didn’t receive during the pandemic. Schools are still working out the details for what this compensation will look like.

The Upside of Remote Learning

While many special needs students have struggled to adapt to remote learning, the experience has been a very positive one for others. Many students with disabilities have found that remote learning is more accessible for their learning style and, for some, it is liberating in a way.

A recent Hechinger Report tells the story of a seventh grader named John who has both a language disorder and ADHD. For John, learning came easier in a remote setting than it ever had in school. When asked about potentially continuing remote learning, John told the report, “I bet I could do so much better, and I could concentrate better.” John’s mother saw a difference as well, commenting, “He misses his friends, obviously, but at the same time, I can tell there was a huge change in his stress levels, and he was able to concentrate on his schoolwork.”

The shift to remote learning has been difficult for teachers and students alike. It has been particularly difficult for children of color and kids without access to technology at home. For a small number of students, however, freedom from the distractions that come with in-person learning has been a blessing. This has led some educators to wonder how these experiences can be applied to improve in-person education in the future for all students.

A Look at Special Education Statistics

As the world recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic, many industries find themselves facing major changes going forward – the education industry included. Though we may not yet fully understand the impact of the pandemic on this generation of students, new data will continue to inform the decisions of policymakers and educators. Statistics on special education will be important as well.

Here are a few statistics on special education in the U.S.:

- The most common disability for American students is a “specific learning disability” like dyslexia. In the 2017-18 school year, roughly one-third (34%) of disabled students had a specific learning disability, 20% a speech/language impairment, and 14% a chronic health problem.

- Autistic students account for about 10% of the nation’s disabled school-age children, compared to just 1.5% two decades earlier. In the same time period, students with specific learning disabilities declined from 45% to 34%.

- The percentage of special education students varies greatly from state to state. The highest rates are found in the northeast, particularly Pennsylvania (18.6%), Maine (18.4%), and Massachusetts (18%). The lowest numbers are found in Texas (9.2%), Hawaii (10.6%), and Idaho (11%). All except 15 states declined in numbers between 2000 and 2018.

- The demographics of special education students mirror the student population overall but there are some differences in gender. Roughly two-thirds of special needs students are male (67%) while overall, student enrollment is fairly evenly split between boys and girls.

In 2018, an article published by U.S. News reported that the number of students receiving special education services is on the rise, citing 13% of all students. This is according to a Department of Education report, titled The Condition of Education 2018 . According to this report, students receiving special education rose from 6.6 million to 6.7 million from the 2014-15 school year to the 2015-16 school year. Though the increase is only slight from the previous year, the lead author of the report notes that it is within the range of what they’ve seen in previous years.

Tips for Parents of Special Needs Children

Though the country is slowly rising out of the pandemic, this generation of students will be feeling the effects for years to come. Students of color and special needs children may be the last to fully recover, though many would argue that the last thing that is needed is a complete return to “normal.” The pandemic may have been challenging (disproportionately so for some groups), but it also highlighted areas where change is needed most which will hopefully inspire policymakers to take action.

As the parent of a special needs child, you may find yourself playing the role of teacher for a little while longer. Even though many schools have reopened for in-person education or plan to in the fall, it could be a long summer and the next school year won’t be without hiccups.

To give you an idea of how the pandemic has affected special needs students in particular, consider the results of a survey conducted by the Child Neurology Foundation of nearly 2,000 families. Parents of special needs children reported an increase in tantrums and other disruptions – 81% reported aggressive outbursts happening at least once a month. The stress of the pandemic has been hard on everyone, but children – perhaps especially children with disabilities – may not have the capacity to understand what is happening or why.

Dr. Tanjala Gibson, MD, FAAN, the director of the Neurodevelopmental Disabilities Clinic at the Center for Developmental Disabilities, suggests parents of special needs children employ these strategies:

- Prioritize safety . Even when your child is in the middle of a meltdown, make sure both of you are safe. If necessary, take steps to keep your child from hurting themselves or other without restricting his or her ability to express their feelings.

- Stop talking . When you’re in a battle with your child, sometimes the best thing you can do is stop talking. Many children become cognitively overloaded and, particularly in the middle of a tantrum, the last thing they want to do is listen. Use fewer words if you can or stop talking altogether to give your child time to calm down.

- Mimic good behavior . Your child feeds off your energy and your mood, so try to keep yourself calm as much as possible. When your child is throwing a tantrum, try using soothing motions like gentle physical touch or take your child for a calming walk. Sometimes the best thing you can do is leave them alone to work through their feelings.

- Offer forgiveness . Never punish your child for feeling overwhelmed or throwing a tantrum. Instead, try to talk to your child after it’s over to figure out the source of the problem so you can prevent it from happening again in the future. Ask your child how you can help.

- Help your child understand . Many children with disabilities resist doing things if they don’t understand why they’re doing them. Take advantage of resources and learning tools to help your child understand things in their own terms.

- Get support . Being the parent of a special needs child can feel isolating at times, so find support wherever you can. Join a parents group, even if it’s only online, and network with other parents to share helpful resources and relevant experiences.

- Engage in self - care . Everyone deserves a little time to themselves now and then, though it may be difficult for you to find spare time when you’re the parent of a special needs child. Take advantage of friends and family to get the time you need to take care of yourself. You won’t be able to give your child your best if you’re not taking care of your own needs.

Being a parent or teacher to a special needs child is always a challenge, but the COVID-19 pandemic has thrown a wrench in the entire public education system. While schools have started to reopen and resume a more-or-less normal mode of education, special needs students still face lasting challenges and may continue to face them for years to come.

More Articles

- Learning Library

- Exceptional Teacher Resource Repository

- Create an Account

Special Education TODAY

Administration pushes for better pay and high quality pathways.

The U.S. Department of Education (ED), in coordination with the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL), has announced new initiatives to expand pathways into teaching, increase pay, and improve working...

New House Appropriations Chair Selected; Cardona Testifies Before Subcommittee

This week, House Republicans selected Representative Tom Cole (R-OK) to fill the remaining term of outgoing House Appropriations Chairwoman Kay Granger (R-TX). Cole was a longtime Republican leader of...

CEC’s 2024 Legacy Proclamation Recipients

In February 2024, the Board of Directors approved the first individuals nominated to receive a CEC Legacy Proclamation:

- Jamie Hopkins

- John Wills Lloyd

- James M. Patton (posthumous)

- Landis M...

Honoring and Expressing Intersectionality Through the Visual and Performing Arts

CEC Interdivisional Video Podcast Series on Critical Global Conversations: Supporting Youth, Families, & Educators in Culturally Responsive and Sustaining Practices Presents “ Honoring and Expressing...

Sign up to receive SET updates in your email!

© 2023 Council for Exceptional Children (CEC). All rights reserved.

- Privacy Policy & Terms of Use

- Accessibility Statement

- Customer Service Center

- Partner Solutions Directory

Top 10 Special Education Issues for the 2023-24 School Year

Harris Beach has a team of four attorneys paying close attention to issues and news in the special education arena. Based on their knowledge of the field, they have assembled a list of issues for school districts, special education administrators and others in the field to be aware of and, perhaps, address proactively.

The top 10 identified issues:

1. Special Education Staff and Program Shortages

Even before COVID, staffing and program shortages were common in the field. The pandemic exacerbated the problem.

In some cases, such as transportation, the shortage is common throughout education. Bus drivers have been in great demand throughout the country.

Harris Beach attorneys recommend school districts, when possible, consider sharing transportation duties with other districts in situations such as transporting students to out-of-district programs.

The problem should also be addressed by the highest levels of the school district, not left to the special education director. Coordination with your Boards of Cooperative Educational Services (BOCES) is essential. The special education director needs to work closely with the superintendent and the transportation director to work out arrangements for all students.

With teacher shortages, districts should persistently advertise for teachers and short and long-term substitutes.

Special education administrators also need to be proactive with superintendents about their needs so the superintendents can encourage BOCES to create needed programs.

Remote learning could be an answer in some circumstances. It is not appropriate for all students or services, but it is for some. Just be aware of certification issues if the remote program is offered from a different state.

Finally, in some instances home services could be an option, but this should be a temporary option, not a long-term solution.

It is imperative that districts have an Individualized Education Program (IEP) in place for a student, even if the program does not currently exist. The Committee on Special Education (CSE) must ensure that the student has an IEP in place that is able to be implemented.

2. Compensatory Services

As a result of COVID and staffing shortages, some students may have missed certain services.

Districts should look back and determine if services were missed because, under some circumstances, compensatory services are necessary to make the student whole.

Requests for compensatory services increased after COVID as more parents became aware that districts must make up services in circumstances in which students did not make expected progress.

For districts, it may be easy to know if services are owed. It is more difficult to pinpoint how much services are owed because students are not automatically entitled to one-for-one make-up sessions. For example, a student who misses 100 hours of speech-language therapy is not automatically entitled to 100 hours of compensatory speech-language therapy. Rather, the inquiry is based on the student’s progress and the student may need more or less to make up a gap in expected progress.

The CSE should consider data on student progress to help determine how much services are owed. Focus on whether the student achieved their annual goals and what was missed by collecting and reviewing the data to identify the deficit and what is needed to address it. Progress Monitoring data from the student’s last year’s IEP will be key information to help determine what if any compensatory services may be due to the student for the 2023-2024 school year.

In some cases, administrators and the parent can work out an agreement on compensatory services. That is ideal, but the district should be certain to document the agreement in writing separate from the IEP. The district should also document the provision of any compensatory services.

3. Managing Student Behaviors and Mental Health Issues

This is a major issue right now, perhaps exacerbated by COVID and a lack of services to address mental health, Harris Beach attorneys note.

One potential issue is Child Find violations. Child Find is a district’s duty to identify and evaluate all students who are reasonably suspected of having a disability. Those students should be referred to the CSE.

School districts should be mindful that students may qualify under special education law, or Section 504, as a student with a disability, even when the student is doing well, when their mental health condition does not allow them to attend school regularly, get through their day or develop appropriate peer or adult relationships.

Districts frequently provide pre-referral services that are too intense and for too long to students with social-emotional and/or behavioral difficulties. These pre-referral interventions are often similar to special education-level support and could indicate the student should have been referred and an IEP developed.

When students exhibit behaviors that interfere with learning, districts should conduct a Functional Behavioral Assessment (FBA) and put a Behavioral Intervention Plan (BIP) in place.

By referring and getting IEPs and BIPs in place, the district is better serving the student and in a better position to defend its plan, attorneys say

4. Pressure to Reduce Suspensions/Restorative Justice

Harris Beach attorneys caution that students with disabilities are protected from discipline for behaviors outside of their control through the manifestation determination review (MDR) process.

Harris Beach attorneys have noticed an increase in suspensions as student behavioral needs have increased for all students, including those in general education and special education. On the other hand, the pressure to keep children in the classroom is strong; the attorneys anticipate future legislative limitations on suspending all students, including students with disabilities.

The state is encouraging Restorative Justice, the attorneys said. This is a theory of justice focused on mediation and agreement rather than punishment. It is based on inclusionary practices that bring students and teachers together. The state has initiated free training to districts on Restorative Justice techniques. Using this alternative approach does not, however, remove the requirement to conduct manifestation determination reviews when student behavior results in the number of suspensions and/or removals from school that trigger the manifestation determination review safeguards.

5. Services for Students Beyond 21 Years of Age

One of the biggest issues affecting particularly New York school districts this year is providing services to student with disabilities through age 22 -- an additional year that will likely impact district budgets.

A U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals decision holding that Connecticut must make available a free appropriate public education (FAPE) until age 22 for students with disabilities (SWDs) who had not received a high school diploma led to New York’s State Education Department to opine that New York school districts must do the same.

The legal requirement is now that a FAPE must be available to students until they either earn a high school diploma or turn 22, whichever occurs first. However, “SED’s Office of Special Education recommends that school districts consider providing such services through the end of the school year in which the student turns 22 or upon receipt of a high school diploma, whichever occurs first.”

This change in eligibility of services will likely have significant impact on school districts across New York. Administrators, boards of education, and special education professionals will need to plan for increasing budget allocations to fund these additional services. It remains unclear whether the Board of Regents and NYSED program offices will provide additional funding and guidance to support districts in meeting these new special education programming and service requirements. The Harris Beach Education Team previously issued a Legal Alert on the subject of services until age 22 .

6. Increase in Independent Educational Evaluation Requests

More parents are asking for Independent Educational Evaluations (IEEs), perhaps because of COVID, staffing shortages or increased awareness.

Harris Beach attorneys recommend districts be proactive. The school district should have an IEE policy and procedure in place identifying the district’s criteria for IEEs, including evaluator credentials, fees, and geographic location. Although it is permissible to reach out to the parent and ask why they want the evaluation, districts cannot require parents to provide a reason. Rather, parents are entitled to IEEs when they disagree with a CSE evaluation conducted by the school district. The school district’s response to a parent’s request for an IEE must be to either grant the request or initiate an impartial due process hearing to demonstrate the district’s own evaluation was appropriate and/or to enforce the district’s IEE criteria. Notably, it is often less expensive to grant the request, but there are some circumstances in which districts decide to initiate due process.

Also, if an independent evaluation is requested, the district should provide parents with an updated provider list for them to select an evaluator. The list should contain active providers within the district’s defined geographic area, who have qualifications and credentials equal to those required by the district and pricing acceptable to the district. Regularly check community rates for evaluations to set your fee parameters.

7. Students Viewed as a Threat to Others

When a student with (or without) a disability is viewed a threat to others, a district will face pressure from two sides: the parents and state requirements to maintain educating the student in the least restrictive environment, as well as the teachers, students, parents of students and others who perceive the student as a threat.

It is advisable for every district to have threat-assessment procedures and a trained team to analyze each threat and determine whether it is a true or passing threat. Students with disabilities who are disciplined for making threats are entitled to manifestation determination review protections when warranted because of the length of suspension or removal.

If a nexus is found between the student’s misconduct and disability, the district may pursue an Interim Alternative Educational Setting (IAES) if the misconduct involved a weapon, drugs, or resulted in in serious bodily injury. Placement in the alternative setting may be for up to 45 school days, but no longer than the length the suspension would have been. The CSE ultimately determines the IAES placement for a student.

The other option is to initiate due process and ask an independent hearing officer to order placement in an IAES because the student is a threat to harm themselves or others. The district would need to prove the student is dangerous, which is often challenging.

8. Greater Pressure to Mainstream Students with Disabilities

Many parents naturally want their children with disabilities to be educated alongside their non-disabled peers. Parents want placement in the least restrictive environment, and this is also required by law. Districts must remember that it is the least restrictive appropriate environment, Harris Beach attorneys say. Some students need smaller environments with less distractions and more individual attention.

Attorneys recommend districts remain patient and be sure to consider the parent’s perspective. CSEs are reminded that it must exhaust all potential supplementary aids and services within a setting before recommending a more restrictive setting for a student. Has the district tried all possible supports and accommodations? Have all options been exhausted? Personal aides? Assistive technology? Behavioral intervention plan?

The key is to try everything reasonably possible and see if it works. There will be pressure, perhaps from inside the building or parents of other students, to separate a student, but districts need to exhaust all reasonable options before placing the student in a more restrictive setting. Sometimes those options will work for a student. But if the interventions are not successful, , the parents may see that the student is not making progress in the setting and accept a change. Either way, the district will be in a better position to defend its decision.

9. Service Animals

School districts are seeing an increase in students being accompanied by service animals in school.

Districts are understandably cautious about service animals in schools because of the distraction they may cause, but there are two questions administrators must ask before granting or denying a request: (1) Is the animal necessary for a disability (if it isn’t obvious, such as a student with blindness)? And, (2) what task is the animal trained to perform?

If the answer is yes to a disability, such as anxiety, and yes to the task, such as applying deep pressure in a stressful situation, the district must grant the request. There’s not a lot of wiggle room, Harris Beach attorneys say. The right to a service animal is a distinct set of rights under the Americans with Disabilities Act, independent of the requirements/rights under the IDEA.

After the animal has been admitted to school, the district will be in a better position to assess the extent to which the service animal is able to perform the task for which it was supposedly trained. The district will also determine the extent to which the animal disrupts school operations or poses a threat to others. Under those circumstances, the service animal may be excluded from the school setting.

10. Reading Instruction

Reading is a hot-button issue for many parents and advocates. Parents of children with reading disabilities frequently make demands for an IEP to include specific teaching methodologies, evaluator credentials, the amount of instruction time and staffing ratios for instruction. Some independent evaluators make blanket recommendations on reading, such as every student should have one hour of daily individual instruction.

But districts should determine reading instruction, including specific annual goals, based on the individual needs of the student. Ultimately, the IEP goals drive the instruction, and a student’s teacher has the authority to identify the appropriate methodology to address those goals. Except in rare exceptions, decisions regarding teaching methodology should be made by teachers in the classroom, not at CSE meetings.

Reading intervention is frequently provided on a building-level basis so CSEs do not include the specialized reading on student IEPs. But for students with disabilities who require specialized reading instruction, specific content such as annual goals, frequency and duration of service, staffing ratios and instructional settings should be included in the student’s IEP.

These 10 issues will significantly impact the special education field in New York and across the country over the next school year.

Latest Posts

- Department of Labor Increases Salary Thresholds for Overtime

- Summary of FTC’s Non-Compete Prohibition and Best Practices For The Business World

- New State Budget Bill Includes Changes to Employment Laws

- Calling Out Affordable Housing Components of New York Budget Bill

- NY to Get Aggressive with Illegal Cannabis Shops to Help Legal Retailers

See more »

DISCLAIMER: Because of the generality of this update, the information provided herein may not be applicable in all situations and should not be acted upon without specific legal advice based on particular situations.

Refine your interests »

Written by:

Published In:

Harris beach pllc on:.

"My best business intelligence, in one easy email…"

Home / Learning / Challenges And Controversial Issues In Special Education Today

Challenges And Controversial Issues In Special Education Today

Delve into the turbulent currents of today’s Special Education landscape. Explore the battlegrounds of inclusion, the intricate dance of diagnosis, and the technological revolution’s disruptive impact. Controversial Issues in Special Education Today takes you on a thrilling roller coaster ride through the hot-button topics that ignite fiery discussions and challenge the status quo. Brace yourself for a thought-provoking journey into the heart of educational controversy.

The landscape of special education is continually evolving, shaped by societal changes, advancements in research, and shifting educational paradigms.

This evolution has given rise to various controversial issues that demand careful consideration. In this brief introduction, I will provide an overview of these emerging challenges within the field of special education .

One of the primary issues is the ongoing debate over inclusive education. While it aims to provide equal educational opportunities for students with disabilities in mainstream classrooms, it raises questions about whether it adequately addresses the diverse needs of these students.

Additionally, the assessment and identification of students with disabilities have been a subject of contention, with concerns about overdiagnosis or underdiagnosis.

Furthermore, the role of technology in special education has generated debates regarding its potential benefits and drawbacks.

The increased use of assistive technology and online learning platforms has prompted discussions about accessibility and the effectiveness of these tools in meeting individual learning needs.

Inclusion Vs. Segregation Study

In the ever-evolving landscape of special education, a heated and persistent debate revolves around the most effective approach for educating students with disabilities.

This profound discussion centers on the dichotomy between inclusive classrooms and specialized settings, each with its own set of proponents and arguments.

Inclusive Classrooms

- Equality and Diversity: Advocates for inclusive education passionately assert that diversity within the classroom is not only a strength but also a reflection of society’s values. Inclusion champions equality, ensuring that students of all abilities share the same learning space.

- Social Integration: A core tenet of inclusion is the belief that students with disabilities benefit from interacting with their typically developing peers. Proponents argue that this social integration can lead to improved social skills and a sense of belonging.

- Legal Mandates: In many countries, laws and regulations mandate inclusive education. These legal frameworks are seen as essential in upholding the principle of equal access to education for all students, regardless of their abilities.

Specialized Settings

Tailored support.

Advocates of specialized settings contend that these environments can offer a higher level of tailored support for students with complex needs. The argument is that such settings can better address the specific challenges that certain students face.

Reduced Distractions

It is posited that specialized settings can provide a less distracting learning environment, particularly beneficial for students with sensory sensitivities or attention-related issues.

Individualized Education

In specialized settings, individualized education plans (IEPs) can be meticulously crafted to cater to the unique and specific requirements of each student. This individualized approach is perceived as crucial for meeting the diverse learning needs within the special education spectrum.

Restraints And Seclusion In Special Education

In the realm of special education, the subject of utilizing restraints and seclusion techniques for managing challenging behaviors has stirred significant controversy and raised ethical and safety concerns that warrant a thorough examination.

This multifaceted issue compels us to delve deeper into the intricate web of implications surrounding the practice.

Ethical Considerations

- Dignity and Respect: Critics vehemently argue that the application of restraints and seclusion can potentially infringe upon a student’s inherent dignity and respect. Subjecting a student to such measures may be seen as degrading and inhumane, causing emotional and psychological harm.

- Autonomy and Consent: A central ethical concern revolves around the question of autonomy and informed consent. When these techniques are employed, students may have limited agency and input in the decision-making process, leading to questions about their rights and personal autonomy within the educational context.

- Potential for Trauma: There exists a compelling concern regarding the potential for trauma. Encounters with restraints and seclusion can be profoundly distressing for students, potentially resulting in long-term psychological and emotional consequences.

Safety Considerations

- Physical Safety: While restraints and seclusion may be implemented with the intention of maintaining physical safety, there are inherent risks involved. Misapplication or excessive use of these techniques can lead to physical harm, not only for the students but also for the staff responsible for their implementation.

- Staff Training: The effective and safe use of restraints and seclusion hinges on the competence and preparedness of staff members. Inadequate training can lead to unintended consequences, including accidents or incidents that escalate rather than resolve.

- Legal Implications: Many regions have established legal regulations governing the use of restraints and seclusion in educational settings. Failure to adhere to these regulations can carry legal consequences for educational institutions, further emphasizing the gravity of the matter.

Balancing the imperative of maintaining safety within special education settings with the ethical quandaries surrounding restraints and seclusion remains an intricate and contentious undertaking.

Ongoing dialogue, rigorous examination, and a commitment to finding alternative, less intrusive strategies are vital components of addressing the complex ethical and safety considerations inherent to these practices.

Psychotropic Medications In Educational Settings

In the realm of special education, the use of psychotropic medications to address behavioral and emotional challenges in students has emerged as a topic of intense debate, sparking concerns and ethical dilemmas.

This complex issue warrants a comprehensive exploration, delving into the various dimensions of the controversies surrounding the administration of psychotropic medications in educational settings.

Overreliance On Medication

One of the prominent controversies centers on the perception of an overreliance on psychotropic medications as a convenient and expedient solution for managing behavioral issues in students.

Critics argue that this approach may overshadow the significance of identifying and addressing underlying psychological, emotional, or environmental factors contributing to a student’s challenges.

Long-Term Effects And Developmental Considerations