November 11, 1999 Books of the Times Caught in Shifting Values (and Plot) By CHRISTOPHER LEHMANN-HAUPT DISGRACE By J. M. Coetzee Viking Penguin. $23.95 isgrace," the new novel by the South African writer J. M. Coetzee, which recently won him his second Booker Prize in Britain -- his "Life and Times of Michael K" won it in 1983 -- gets off to an irresistibly strong start. David Lurie, a 52-year-old twice-divorced adjunct professor of communications at Cape Technical University (formerly Cape Town University College), is at loose ends sexually after having had to end an affectionate relationship with a paid escort. One evening he runs into Melanie Isaacs, an attractive student in his class on the Romantic poets. Conversation leads to intimacy, and although he knows he is making a mistake, he begins an affair with her. Things quickly go off the track. Melanie's boyfriend begins to threaten him. She withdraws from his class and then from school. Her father shows up at his office, denouncing him. An official complaint is lodged. He is called before a committee composed in part of unsympathetic women. He at once pleads guilty to sexual harassment, infuriating the committee by his unwillingness to explain or express sincere apology. The committee recommends his termination without benefits. The community denounces his behavior. He packs up and leaves, accepting his exile in a state of disgrace. You read this first quarter of the novel by Coetzee (pronounced cught-SEE-uh) with deeply mixed feelings. You know that David has transgressed by abusing his power as a teacher. But you also smell a whiff of thought-policing in the air. As David later reflects: "Scapegoating worked in practice while it still had religious power behind it. . . . Then the gods died, and all of a sudden you had to cleanse the city without divine help. Real actions were demanded instead of symbolism. The censor was born, in the Roman sense. Watchfulness became the watchword: the watchfulness of all over all. Purgation was replaced by the purge." You think the issue of David's transgression is going to be further explored, but now the scene shifts radically and you see that his experience at the college is only the beginning of his education on the new realities of South Africa near the end of the millennium. After giving up his teaching job, he drives east to the smallholding of his daughter, Lucy, in the Eastern Cape. He is skeptical of her life as a farmer of flowers and produce and as a kennel keeper for neighboring dogs, but he settles in and lends a hand, determined to work in his spare time on a opera he has been meaning to write about Lord Byron in Italy. But then one day three black strangers show up asking to use Lucy's telephone. When she lets them into her house, they throw David into the bathroom, try to set him on fire and gang-rape Lucy. David, humiliated and outraged, wants justice, but Lucy, while evidently broken in spirit, asks him not to tell anyone what has happened to her. At once you see a parallel between David's position as a father and that of Isaacs, the father of David's student. You think that maybe David is being punished for his sexual arrogance, but once again Coetzee pulls the rug from under his plot. Nothing is what David expects it to be. All values are shifting in post-apartheid South Africa. The atmosphere is a little like the composition of David's Byron opera, which begins as a classical work and ends up grotesquely distorted, a comic solo sung by Byron's abandoned lover to the accompaniment of a seven-string banjo. The effect of the novel's plot is deeply disturbing, in part because of what happens to David and Lucy, but equally because of the disintegrating context of their experiences. Not even language can be trusted. "What is to be done?" David wonders. "Nothing that he, the onetime teacher of communications, can see. Nothing short of starting all over again with the ABC. By the time the big words come back reconstructed, purified, fit to be trusted once more, he will be long dead." The only meaning David can find is in the act of helping a neighbor euthanize and incinerate the sick and superfluous dogs in the community, a bitter acknowledgment, perhaps, of what his life has been reduced to, and a tribute to the final line of Kafka's "Trial," which follows Joseph K.'s stabbing and reads: " 'Like a dog!' he said; it was as if he meant the shame of it to outlive him." (Earlier in "Disgrace," David has used the same words to describe his and Lucy's humiliation: "Like a dog.") But if David is bitter, Lucy is accepting. When David asks her if she loves the child she is carrying because of her rape, she responds: "The child? No. How could I? But I will. Love will grow -- one can trust Mother Nature for that. I am determined to be a good mother, David. A good mother and a good person. You should try to be a good person too." Against the background of the disintegration that pervades "Disgrace," Lucy's trust in nature is a faint beacon of hope. But in the shattering world that Coetzee has created, you reach for any glimmer of light.

- Member Login

- Library Patron Login

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR

FREE NEWSLETTERS

Search: Title Author Article Search String:

Reviews of Disgrace by J M Coetzee

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

by J M Coetzee

Critics' Opinion:

Readers' Opinion:

- Literary Fiction

- Middle & Southern Africa

- 1980s & '90s

- Mid-Life Onwards

Rate this book

Buy This Book

About this Book

- Reading Guide

Book Summary

Written with the austere clarity that has made Coetzee the winner of two Booker Prizes and the Nobel Prize, Disgrace explores the downfall of one man and dramatizes the plight of a country caught in the chaotic aftermath of centuries of racial oppression.

Set in post-apartheid South Africa, Nobel Prize Winner, J. M. Coetzee’s searing novel tells the story of David Lurie, a twice divorced, 52-year-old professor of communications and Romantic Poetry at Cape Technical University. Lurie believes he has created a comfortable, if somewhat passionless, life for himself. He lives within his financial and emotional means. Though his position at the university has been reduced, he teaches his classes dutifully; and while age has diminished his attractiveness, weekly visits to a prostitute satisfy his sexual needs. He considers himself happy. But when Lurie seduces one of his students, he sets in motion a chain of events that will shatter his complacency and leave him utterly disgraced. Lurie pursues his relationship with the young Melanie—whom he describes as having hips "as slim as a twelve-year-old’s"—obsessively and narcissistically, ignoring, on one occasion, her wish not to have sex. When Melanie and her father lodge a complaint against him, Lurie is brought before an academic committee where he admits he is guilty of all the charges but refuses to express any repentance for his acts. In the furor of the scandal, jeered at by students, threatened by Melanie’s boyfriend, ridiculed by his ex-wife, Lurie is forced to resign and flees Cape Town for his daughter Lucy’s smallholding in the country. There he struggles to rekindle his relationship with Lucy and to understand the changing relations of blacks and whites in the new South Africa. But when three black strangers appear at their house asking to make a phone call, a harrowing afternoon of violence follows which leaves both of them badly shaken and further estranged from one another. After a brief return to Cape Town, where Lurie discovers his home has also been vandalized, he decides to stay on with his daughter, who is pregnant with the child of one of her attackers. Now thoroughly humiliated, Lurie devotes himself to volunteering at the animal clinic, where he helps put down diseased and unwanted dogs. It is here, Coetzee seems to suggest, that Lurie gains a redeeming sense of compassion absent from his life up to this point. Written with the austere clarity that has made J. M. Coetzee the winner of two Booker Prizes, Disgrace explores the downfall of one man and dramatizes, with unforgettable, at times almost unbearable, vividness the plight of a country caught in the chaotic aftermath of centuries of racial oppression.

Chapter One

FOR A MAN of his age, fifty-two, divorced, he has, to his mind, solved the problem of sex rather well. On Thursday afternoons he drives to Green Point. Punctually at two p.m. he presses the buzzer at the entrance to Windsor Mansions, speaks his name, and enters. Waiting for him at the door of No. 113 is Soraya. He goes straight through to the bedroom, which is pleasant-smelling and softly lit, and undresses. Soraya emerges from the bathroom, drops her robe, slides into bed beside him. 'Have you missed me?' she asks. 'I miss you all the time,' he replies. He strokes her honey-brown body, unmarked by the sun; he stretches her out, kisses her breasts; they make love. Soraya is tall and slim, with long black hair and dark, liquid eyes. Technically he is old enough to be her father; but then, technically, one can be a father at twelve. He has been on her books for over a year; he finds her entirely satisfactory. In the desert of the week ...

Please be aware that this discussion guide will contain spoilers!

- The novel begins by telling us that "For a man his age, fifty-two, divorced, he has, to his mind, solved the problem of sex rather well." What can you infer about David Lurie's character from this sentence? In what ways is it significant, particularly in relation to the events that follow, that he views sex as a "problem" and that his "solution" depends upon a prostitute?

- Lurie describes sexual intercourse with the prostitute Soraya as being like the copulation of snakes, "lengthy, absorbed, but rather abstract, rather dry, even at its hottest." When he decides to seduce his student, Melanie, they are passing through the college gardens. After their affair has been discovered ...

- "Beyond the Book" articles

- Free books to read and review (US only)

- Find books by time period, setting & theme

- Read-alike suggestions by book and author

- Book club discussions

- and much more!

- Just $45 for 12 months or $15 for 3 months.

- More about membership!

Media Reviews

Reader reviews.

Write your own review!

Read-Alikes

- Genres & Themes

If you liked Disgrace, try these:

The Promise

by Damon Galgut

Published 2022

About this book

More by this author

A modern family saga that could only have come from South Africa, written in gorgeous prose by twice Booker Prize-shortlisted author Damon Galgut.

The Largesse of the Sea Maiden

by Denis Johnson

Published 2019

Twenty-five years after Jesus' Son, a haunting new collection of short stories on aging, mortality, and transcendence, from National Book Award winner and two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist Denis Johnson

Books with similar themes

Support bookbrowse.

Join our inner reading circle, go ad-free and get way more!

Find out more

BookBrowse Book Club

Members Recommend

The Mystery Writer by Sulari Gentill

There's nothing easier to dismiss than a conspiracy theory—until it turns out to be true.

The Stone Home by Crystal Hana Kim

A moving family drama and coming-of-age story revealing a dark corner of South Korean history.

The Day Tripper by James Goodhand

The right guy, the right place, the wrong time.

Who Said...

There is no such thing as a moral or immoral book. Books are either well written or badly written. That is all.

Click Here to find out who said this, as well as discovering other famous literary quotes!

Solve this clue:

and be entered to win..

Your guide to exceptional books

BookBrowse seeks out and recommends the best in contemporary fiction and nonfiction—books that not only engage and entertain but also deepen our understanding of ourselves and the world around us.

Subscribe to receive some of our best reviews, "beyond the book" articles, book club info and giveaways by email.

- Emerging Critics

Criticism & Features

March 31, 2008

In Retrospect: “Disgrace,” Coetzee’s Masterpiece

J.M Coetzee’s “Disgrace” is about a lot of things, but at its heart it is an anatomy of racial hierarchy change in contemporary South Africa. A very quiet side note to this is its analysis of man’s disgraceful treatment of animals. “Disgrace” is a pitiless and errorless book about the condition of the human experience at the end of the twentieth century; while not altogether without hope, the book and its title is a condemnation of the basic state of modern humanity.

What happens in this book can be summed up quickly. Professor David Lurie, a white, thoroughly Western, classical intellectual and defender of the canon forces himself upon an undergraduate student who at first invites his advances. Lurie has done this sort of thing before, but he is aging and less in tune with what he can and can’t get away with. Through machinations that may or may not be of her own accord, the girl, Melanie Isaacs, brings an abuse charge against the professor, and his stubborn refusal to acknowledge what he has done as well as the changed context of his post-Apartheid nation lead to his dismissal in ‘disgrace’ from the university. He takes refuge on his daughter Lucy’s farm in the Eastern Cape.

There we are introduced to Petrus, her black neighbor who is slowly taking advantage of the changed social order to lift himself from a “dog-man” to a substantial land holder. Lucy is nearly alone in her refusal to join the “white-flight” exodus out of such predominantly black areas; in the book’s most dramatic scene she is raped by three black men as her father is locked in a bathroom and set afire. The dogs that she tends and loves are massacred with her own gun; her father is left to deal on his own with her abuse, which becomes a metaphor for the abuse of white South Africa by the black South Africa that is as angry as it ever was in its new empowerment. Lucy becomes pregnant during the attack and decides not only not to press charges against her attackers, but to keep the child; her father David, who has lost everything, ends the book with a vision of his daughter working stooped over in her fields. He sees her as a peasant; he understands that all the centuries of white rule and progress in the country have come to naught.

“Disgrace” is the definitive work on South Africa’s present state. In an early dramatic scene, Lurie is confronted by Melanie Isaacs’s father outside of his office at the university. Though the girl’s father is white, as is Lurie, his words speak to the anger that is the inheritance of forcible white rule in South Africa:

“‘Professor,’ he begins, laying heavy stress on the word, ‘you may be very educated and all that, but what you have done is not right…We put our children in the hands of you people because we think we can trust you. If we can’t trust the university, who can we trust?…No, Professor Lurie, you may be big and mighty and have all kinds of degrees, but if I was you I’d be very ashamed of myself, so help me God. If I’ve got hold of the wrong end of the stick, now is your chance to say, but I don’t think so, I can see it from your face.’” And when Lurie finds the accusation beneath him and turns away, the girl’s father shouts, “‘You can’t just run away like that! You have not heard the last of it, I tell you!’”

And indeed Lurie is not able to just run away, as the last Apartheid rulers could not avoid the inquiries and judgments of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. In scenes wholly representative of that body, and as familiar as any university judiciary committee in the newly liberalized West, Lurie is called to account for his harassment of Melanie before a mixed raced panel: “At five o’clock he is waiting in the corridor. Aram Hakim, sleek and youthful, emerges and ushers him in. There are already two persons in the room: Elaine Winter, chair of his department, and Farodia Rassool from Social Sciences, who chairs the university committee on discrimination…”

What this panel wants most from Lurie is an apology, a statement of admission that what he has done was wrong. And like a stalwart of the old order, Lurie refuses to admit anything but his actions. Fine enough in most cases, but not in South Africa, where culprits cannot be sent away but must somehow be woven into the fabric of society. What the new order wants from the old is not an admission of guilt, but a kowtow, one that Lurie is unwilling to give. One of his non-white colleagues offers Lurie this bit of advice, “‘Take a yellow card. Minimize the damage, wait for the scandal to blow over…Sensitivity training. Community service. Counseling. Whatever you can negotiate.’”

“‘Counseling? I need counseling?’” Lurie incredulously asks. Even friendly colleagues soon abandon him, so thorough is Lurie’s inability to understand how his world has changed. In an example of Coetzee’s most beautiful writing, the height of the media frenzy that surrounds Lurie’s trial is described like this: “They circle around him like hunters who have cornered a strange beast and do not know how to finish it off.”

Lurie is stripped of his titles and rank and finds himself on the rural farm of his lesbian daughter Lucy. Lucy is making do as the last hanger-on of a white hippie commune in the Eastern Cape, growing vegetables and flowers for market and keeping a boarding kennel of guard dogs, all those Rottweilers and German Shepherds and ridgebacks that upheld and became symbols for the worst of white rule’s abuses. Here Lurie meets Petrus, who introduces himself to the professor in this way, “‘I look after the dogs and I work in the garden…I am the gardener and the dog-man.’ He reflects for a moment. ‘The dog-man,’ he repeats, savoring the phrase.”

Once upon a time in South Africa, Petrus would have been just that, the impoverished and disenfranchised dog-man, the hired man who shoveled shit and fed offal to Lucy’s dogs. But the South Africa that Lurie would not bow to at the university has changed so thoroughly here in its rural reaches that the irony with which Petrus introduces himself is lost on neither of them. For though Petrus does tend to Lucy’s dogs for a wage, he has gained his own holding of land which abuts Lucy’s farm, is building a house, is gaining more. While Petrus labors at his fields and schemes on how to make Lucy’s land his own, Lurie looks at his refuge on his daughter’s farm as a time to finally complete his life’s opus: an opera about Byron’s last amorous days in Italy.

Here, Coetzee sets up a wonderful juxtaposition about the two cultures that have just changed positions. The work of Petrus’ ascendant black Africa has to do with toil and sweat and the growth of the soil, while the work of Lurie’s descendent white Africa has to do with an opera that most likely will never be completed and, as Lurie freely admits to himself, will never make any money. All through this book, Coetzee subtly reveals the ways in which the West has become irrelevant in South Africa. On Lucy’s farm, Lurie must contend with people who speak African languages he does not and will never know, who know nothing of Byron nor anyone else in the Western canon, who do not treasure these things, who are happy to ransack white homes for food and electronics but who leave the works of the great Western canon behind. As Lurie sees it, the crimes committed against himself and his daughter, indeed the violent crimes vivisecting the country as it was at Apartheid’s end, are not simply crimes, but individual sallies in a great black war of vengeance. This is illuminated most clearly when Lurie returns to his apartment in Cape Town:

“He wanders through the house taking a census of his losses. His bedroom has been ransacked, the cupboards yawn bare. His sound equipment is gone, his tapes and records, his computer equipment. In his study the desk and filing cabinet have been broken open; papers are scattered everywhere. The kitchen has been thoroughly stripped…No ordinary burglary. A raiding party moving in, cleaning out the site, retreating laden with bags, boxes, suitcases. Booty; war reparations; another incident in the great campaign of redistribution. Who is at this moment wearing his shoes? Have Beethoven and Janá cek found homes for themselves or have they been tossed out on the rubbish heap?” The reader can’t help but amending the final line with the obvious conclusion, ‘the rubbish heap of history.’

Coetzee is an agile writer, filling his pages with action and images that make “Disgrace” the page-turner that it is. “Things fall apart” in a moment in Coetzee, just as for someone like Lurie they did in his home country with the ’94 change of government. The anger and tensions building in “Disgrace” finally spill across the page on a day like any other on the farm, the beautiful wild geese who visit coasting across the surface of Lucy’s irrigation dam. Lucy and her father have taken two of the dogs, Dobermans, out for a long walk, they discuss history, symbolism and psychology in relation to Lurie’s dismissal from the university; when they return to the house, the dogs, guards and watchdogs all, are in an uproar, and three black men are waiting for them. The men have a story about a sick woman in the act of childbirth, it’s an emergency, may they use the phone? Lucy cages the dogs and lets the men in. Here Coetzee reveals the breadth of his mastery. The action is quick and definitive; there is nothing theoretical about it:

“A blow catches [Lurie] on the crown of the head. He has time to think, If I am still conscious then I am all right, before his limbs to water and he crumples. He is aware of being dragged across the kitchen floor…He is in the lavatory, the lavatory of Lucy’s house. Dizzily he gets to his feet. The door is locked, the key is gone…So it has come, the day of testing. Without warning, without fanfare, it is here, and he is in the middle of it…The door opens, knocking him off balance…‘The keys,’ says the man…The man raises the bottle. His face is placid, without trace of anger. It is merely a job he is doing: getting someone to hand over an article. If it entails hitting him with a bottle, he will hit him, hit him as many times as is necessary…[Lurie] speaks Italian, he speaks French, but Italian and French will not save him here in darkest Africa…Mission work: what has it left behind…Nothing that he can see…Now the tall man appears from around the front, carrying the rifle. With practiced ease he brings a cartridge up into the breech, thrusts the muzzle into the dogs’ cage…There is a heavy report; blood and brains splatter the cage.”

Throughout the attack, Lurie remains locked in the bathroom, watching the violence through the bars over the bathroom’s small window, imprisoned by the lock and heavy door of his white culture’s own device. It’s an image that call to mind Robben Island.

The dogs are slaughtered, Lucy is raped, Lurie is doused with methylated spirits and set afire. When the door to the bathroom is momentarily opened so that the men can toss the spirits onto him, what Lurie sees reveals the genius of Coetzee’s artistic eye, “…he glimpses the boy in the flowered shirt, eating from a tub of ice cream.”

If Lurie had felt bitter and helpless before in this changed and unfamiliar world, the attack leaves him broken. He fixates on what happened to Lucy in her bedroom at the hands of those men, an act he could not see; his mind runs wild with his imagining of it: “No wonder [women] are so vehement against rape…Rape, god of chaos and mixture, violator of seclusions. Raping a lesbian worse than raping a virgin: more of a blow. Did they know what they were up to, those men? Had word got around?”

Lurie’s relationship with his daughter has always been strained. Lucy knows her father’s history with women, knows that the trouble he has brought on himself throughout his life because of them has been wholly of his own making. In a reverie, Lurie thinks of all those women like this, “…a stream of images pours down, images of women he has known on two continents, some from so far away in time that he barely recognizes them. Like leaves blown on the wind, pell-mell, they pass before him. A fair field full of folk: hundreds of lives all tangled with his. He holds his breath, willing the vision to continue. What happened to them, all those women, all those lives? Are there moments when they too, or some of them, are plunged without warning into the ocean of memory? The German girl: is it possible that at this very instant she is remembering the man who picked her up on that roadside in Africa and spent the night with her? Enriched: that was the word the newspapers picked on to jeer at. A stupid word to let slip, under the circumstances, yet now, at this moment, he would stand by it. By Melanie, by the girl in Touws River; by Rosalind, Bev Shaw, Soraya: by each of them he was enriched, and by others too, even the least of them, even the failures. Like a flower blooming in his breast, his heart floods with thankfulness.”

Just as Lurie passes judgment on blacks who commit crimes against whites in what he terms “the great campaign of redistribution,” his reverie of women, like all those gilded monuments to progress and colonialism that litter the capitals of the Western World, should be judged on equal terms. While some of his adventures with women were mutually “enriching,” others were not—his harassment of Melanie Isaacs was not, nor was his stalking of the “exotic” prostitute Soraya early in the book. Colonialism, and white South Africa, when judged through this prism, might rightly be lauded for the tractors and radios that people like Petrus and Lucy’s rapists covet and use, but what cannot be forgotten are all the ways in which the colonizer simply took from the colonized to the “enrichment” of themselves. It might be nice to remember the brown arms of the women of the world’s palm-fringed coasts, but the guns and steel that conquered those coasts and allowed those memories to be made were fired and swung by white hearts drunk with darkness.

Lucy has not forgotten this history, and it cannot be said that Lurie has forgotten it either. Whenever some abuse visits them from the world of the blacks, Lurie is quick to explain it away to perceived wrongs being made right. But where he and Lucy differ is that Lurie, just as in his refusal to apologize for his victimization of Melanie, does not truly see his fault in history; Lucy does, so much so that she even offers her body to it in penance. When one of her rapists returns and is revealed to be a relative of her neighbor Petrus, Lurie wants to report it to the police. Lucy stays him. “‘Don’t shout at me, David. This is my life. I am the one who has to live here…As for Petrus, he is not some hired laborer whom I can sack because in my opinion he is mixed up with the wrong people. That’s all gone, gone with the wind.’” And later, of her rape and her response to it, she says, “‘It was so personal…It was done with such personal hatred. That was what stunned me more than anything. The rest was…expected. But why did they hate me so? I had never set eyes on them…I think they have done it before…At least the two older ones. I think they are rapists first and foremost. Stealing things is just incidental. A side-line. I think they do rape…I think I am in their territory. They have marked me. They will come back for me. …But isn’t there another way of looking at it, David? What if…what if that is the price one has to pay for staying on? Perhaps that is how they look at it; perhaps that is how I should look at it too. They see me as owing something. They see themselves as debt collectors, tax collectors. Why should I be allowed to live here without paying?’”

Her father rejects this, pleads with her, writers her a letter. “‘Dearest Lucy, With all the love in the world, I must say the following. You are on the brink of a dangerous error. You wish to humble yourself before history.’” She writes him this back, “‘…if I leave the farm now I will leave defeated, and will taste that defeat for the rest of my life.’”

Lucy is her own woman, has her own response to this changed hierarchy. Flight to Europe is not acceptable to her, she sees herself as a child of this soil. And now that the lordship of this soil has changed from white to black, she is vastly more willing to meet those terms than David is. Petrus confronts Lurie about Lurie’s threats to turn the rapist brother-in-law in to the police: “‘He is a child. He is my family, my people… You say it is bad, what happened…I also say it is bad. It is bad. But it is finish…It is finish.’” Petrus also offers the white man a solution to the problem of his daughter’s security. “‘He (the rapist) will marry her,’ he says at last. ‘He will marry Lucy, only he is too young, too young to be marry… Maybe one day he can marry, but not now. I will marry.’”

While Lurie is outraged, Lucy is not. She is pregnant, she is poor, she is alone, she is white. She tells her father, “‘Objectively I am a woman alone. I have no brothers. I have a father, but he is far away and anyhow powerless in the terms that matter here. To whom can I turn for protection? To Ettinger? [Ettinger is the last of the old-style, and armed, Boer farmers in the area.] It is just a matter of time before Ettinger is found with a bullet in his back. Practically speaking, there is only Petrus left. Petrus may not be a big man but he is big enough for someone small like me.’”

When her father again expresses indignation, Lucy loses her patience, “‘I don’t believe you get the point, David. Petrus is not offering me a church wedding followed by a honeymoon on the Wild Coast. He is offering an alliance, a deal. I contribute the land, in return for which I am allowed to creep in under his wing. Otherwise, he wants to remind me, I am without protection, I am fair game…it is humiliating. But perhaps that is a good point to start from again…With nothing…No cards, no weapons, no property, no rights, no dignity…like a dog.’”

Lucy’s final point is made again and again in the book; animals suffer here at the hands of men of all colors. Goats are slaughtered for parties, sheep are staked and starved before their deaths, dogs suffer from the lottery of their own fecundity. In moving passages about Lurie’s volunteer job—his unconscious admission that he does need to do penance in the world—putting them to sleep in a shelter, we see the only true moments of growth that ever come to him: “He has learned…to concentrate all his attention on the animal they are killing, giving it what he no longer has difficulty calling by its proper name: love.” The thoughtless slavery of animals is quietly documented on page after page of “Disgrace,” and sometimes not so quietly as when the gentle woman charged with the destruction of the cast-off dogs says to Lurie, “‘Yes we eat up a lot of animals in this country…It doesn’t seem to do us much good. I’m not sure how we will justify it to them.’” It’s in this that Coetzee reaches beyond, showing that what equalizes and nullifies questions of history and race is the unity of man in its abuse of animals.

Here the curtain falls in the novel on the bad old white South Africa, opens on a newer, humbled one. The night Lurie spends in pillaged apartment is the best metaphor for his end of things: “The lights are cut off, the telephone is dead…he will spend the night in the dark…He is too depressed to act. Let it all go to hell, he thinks, and sinks into a chair and closes his eyes.” Lucy in her fields, “…is becoming a peasant.” And Petrus on his tractor is the new boss. What his rule will mean is not the subject of this book, but the fact of his coming into power is. Of the child that Lucy will soon bear, Lurie thinks this, “So it will go on, a line of existences in which his share, his gift, will grow inexorably less and less, till it may as well be forgotten.”

Wouldn’t it be happy to think so? But what is more likely for South Africa as with so many colonized and troubled places in the world is a metaphor that Coetzee offers us much earlier in the book, when Lurie and Petrus are down together in a drained storage dam, working, doing a nasty job, shoveling out the muck. It’s a tight, fetid place they must inhabit together. Within moments, as a sorry testament to who we really are, the white man and the black man lift their voices in argument. It’s not hopeful, but it’s also not hopeless. “Disgrace,” like that perfect scene, is simply an anatomy of the truth.— Tony D’Souza

Labels: In Retrospect Series

Find anything you save across the site in your account

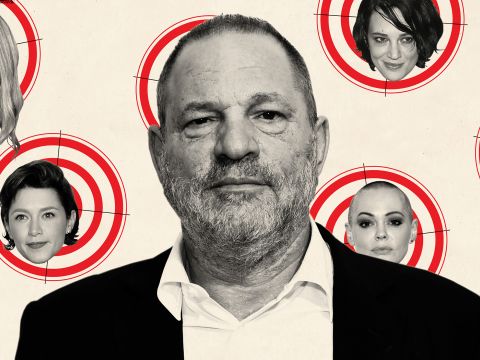

Reading J. M. Coetzee’s “Disgrace” During the Harvey Weinstein Trial

By Jia Tolentino

“These are puritanical times,” David Lurie, the protagonist of J. M. Coetzee’s novel “ Disgrace ,” from 1999, tells his daughter, Lucy. “Private life is public business. Prurience is respectable, prurience and sentiment.” Lurie is speaking with his daughter at her small landholding in eastern South Africa, which is serving as his temporary escape from Cape Town. He is in retreat, having been fired from a university, where he taught Romantic poetry, over what he regards as a lusty affair with a student, and what that student, named Melanie, regards as coercion, perhaps rape.

Lurie is unashamed of what he’s done—there is an icy near-clarity to the way he experiences the act of overpowering her. When he calls Melanie on the phone, he hears in her voice “all her uncertainty. Too young. She will not know how to deal with him; he ought to let her go. But he is in the grip of something.” He shows up at her apartment, uninvited, and Melanie is “too surprised to resist the intruder who thrusts himself upon her.” Her limbs crumple, and she struggles, tells him no. But “nothing will stop him,” and Lurie carries Melanie to her bedroom. “She does not resist,” Coetzee writes. “All she does is avert herself: avert her lips, avert her eyes. . . . Little shivers of cold run through her. . . . Not rape, not quite that, but undesired nevertheless, undesired to the core. As though she had decided to go slack, die within herself for the duration. . . . So that everything done to her might be done, as it were, far away.” After it’s over, she asks him to leave, and in his car Lurie has “no doubt, she, Melanie, is trying to cleanse herself of it, of him. . . . running a bath, stepping into the water, eyes closed like a sleepwalker.”

But Melanie’s experience feels immaterial to Lurie. If his desire is real, how could it be wrong? When, later, he recalls the university’s investigation, he identifies his age as the real crime, and his decaying body the punishment. He believes himself guilty not of raping a student but simply of growing old, becoming one of those men from whom a prostitute might shudder “as one shudders at a cockroach in a washbasin in the middle of the night.” He had been put on trial “for his way of life,” he thinks. “For unnatural acts: for broadcasting old seed, tired seed, seed that does not quicken, contra naturam . If the old men hog the young women, what will be the future of the species? That, at bottom, was the case for the prosecution. Half of literature is about it: young women struggling to escape from under the weight of old men, for the sake of the species.”

Lurie, who is white, believes that he has become disenfranchised, and this feeling goes hand in hand with his sense of entitlement to Melanie’s body. Old men, with their “stained raincoats and cracked false teeth and hairy earlobes—all of them were once upon a time children of God, with straight limbs and clear eyes,” he thinks, sitting hidden in a dark auditorium and watching her rehearse a play. “Can they be blamed for clinging to the last to their place at the sweet banquet of the senses?” Coetzee’s novel, though, doesn’t deal in blame. “Disgrace” is marked, instead, by the sustained juxtaposition of inevitability and unfathomability—it suggests that power exerted without consideration of humanity carries fearsome, unknowable, and often directly retributive costs.

The word “disgrace” now follows Harvey Weinstein like a shadow—elongating, stretching beyond him, as the light gets lower on his life. He’s the disgraced producer, the disgraced mogul. His sexual-assault trial in New York is completing its fourth week. Six women have testified that he assaulted them. The defense’s first witness, a friend of Weinstein’s, was confronted in court with texts he’d written to Weinstein saying that there was “likely a bunch of truth to the claims that you behaved like a cad and more,” and that, if “a lot of these girls had been my daughter, I would have wanted to beat the shit out of you.” The prosecution and the defense have both wrapped. In the defense’s closing argument, Donna Rotunno, one of Weinstein’s attorneys, suggested that the prosecution’s case imagines a universe in which “women are not responsible” for their actions. The prosecution will offer its closing statement on Friday, and the jury will begin deliberating next week.

Outside the courtroom, the verdict has already been handed down: a hundred women have accused Weinstein of assault or harassment, ninety-four of them on the record. And yet a criminal conviction is uncertain. It is uniquely and brutally difficult to prove rape in a courtroom; for most of history, legal guidelines were written to insure that this would be so. Bill Cosby’s conviction, in 2018, might seem like a precedent for Weinstein’s trial: both cases involve a famous defendant facing old accusations, with a lack of physical evidence, amid a wider scandal in the media. But Weinstein’s trial demands that the jury consider sexual assault in contexts that have almost always been regarded as too complicated for a courtroom : the charges come from the testimony of two women, Jessica Mann, who engaged in consensual sex with Weinstein after he allegedly assaulted her, and Miriam Haleyi, who sent him friendly e-mails after the alleged incident. This consensual contact, by their accounts, was also profoundly unwanted—a nuance that may illuminate the incidents in question or obscure them, depending on who’s looking. Mann, who was twenty-seven when she alleges Weinstein raped her, testified over the course of three days, the second of which was cut short when she couldn’t stop sobbing on the stand. On Monday, the defense called as a witness a former friend of Mann’s, who characterized Mann’s relationship with Weinstein as romantic rather than abusive and degrading. Rotunno, the defense attorney, has argued that Mann was the one exploiting Weinstein, for a chance at professional success. Rotunno also recently told the Times ’ Megan Twohey that she’d never been assaulted because “I would never put myself in that position.” (In “Disgrace,” Lurie’s lawyer advises him to get a woman to represent him, “as a matter of strategy.”)

Melanie, Lurie’s victim in Coetzee’s novel, goes to Lurie’s house after the assault and spends the night in his daughter’s room. She asks him to excuse her absences from class. Faced with this reminder that Melanie is a person whose life he has severely disrupted, Lurie thinks, “She is behaving badly. . . . she is learning to exploit him and will probably exploit him further.” Then, one day, after Lurie has gone to live with Lucy, three black South African men approach the farm and ask to use the telephone. They attack Lurie, set him on fire, shoot the dogs who board in Lucy’s kennel, burglarize the house, and steal the car. Lucy is silent about what the men do to her, but, later, her pregnancy gives it away. A monstrous parallel is established: the perpetrators of violence—both Lurie and the men who rape Lucy—act out of a semi-conscious conviction that they are righting an imbalance beyond their control.

At Weinstein’s trial, the particulars of the defendant’s appearance—his body, his age—have been evoked repeatedly, by both sides. Now sixty-seven, Weinstein has shown up in court looking older than that, and dishevelled in a way that seems deliberate. He had spinal surgery last month, to treat an injury from a car accident, and he has been using a walker with tennis balls affixed to the bottoms of its legs. (Reports of his behavior outside the courtroom contrast with this apparent frailty: Page Six reported that Weinstein threw a Super Bowl party the night before he was spotted dozing off in court.) The prosecution, meanwhile, has made a point of displaying images of Weinstein around the time of the alleged assaults, reminding the jurors that he was six feet tall and close to three hundred pounds. The prosecution has also, at times, seemed to imply that Weinstein was too ugly or disgusting for any of the young and beautiful women who were his alleged victims to have plausibly wanted to have sex with him. Mann, reflexively invoking the sort of discrimination that is faced by intersex people, testified, with apparent distress , that Weinstein’s genitals had “extreme scarring,” adding, “He does not have testicles, and it appears that he has a vagina.” Lauren Young, a corroborating witness, who says that Weinstein trapped her in a bathroom in Los Angeles and groped her while masturbating, told the jury that Weinstein was “hairy,” with rolls, moles, and had a “disgusting-looking penis.” Jurors have been shown photos of Weinstein’s naked body, which are intended to corroborate these accounts.

Weinstein does not deny that these women saw him naked, so establishing the details of his anatomy does not seem entirely necessary for establishing the truth of their claims. One can consent to and desire sex with people who are not conventionally physically attractive, and rapists can be good-looking; in her closing argument, Rotunno derided the prosecution for providing a “script” in which Weinstein “is so unattractive and large that no woman would want to sleep with him.”

Insofar as the prosecution did push this line of reasoning, it feels like a mistake. Of course the women had thoughts about Weinstein’s appearance; one of the prosecution’s corroborating witnesses said that she and Haleyi regarded him, at one point, as a “pathetic older man who was trying really hard to hit on Miriam,” and that they found this, at the time, a little bit funny. But the trial isn’t, or shouldn’t be, about how they saw him—it’s about how he saw them. In “Disgrace,” when Lurie first attempts to sleep with Melanie, he plies her with alcohol and says that “a woman’s beauty does not belong to her alone.” Later, he watches her act in a student play, tottering around in high heels, and thinks, “She does not own herself; perhaps he does not own himself either.” The sheer banality of this justification for rape is matched by Lurie’s conviction that his aging body is world-historically meaningful and elegiac. In a recent interview with David Marchese at the Times , Tina Brown, who launched the magazine Talk with Weinstein, in 1999, surmised that his psychology came down to “self-hatred, that he thought of himself as a deeply unattractive man and was tortured about that.” As a movie producer, Weinstein advanced the careers of beautiful young women—a life’s work that appears to have had two inseparable faces of generosity and demand. Hollywood systematically reduces people to their ability to inspire lust and longing from strangers; if Weinstein reduced women to a walking surfeit of a resource—beauty—that demanded seizure and distribution, perhaps he also imagined himself as a walking deficit of that resource. A man fixated on the supposed injustice of his own lack sometimes concludes that he is entitled to what he doesn’t possess .

Coetzee does not portray Lurie as the serial predator that Weinstein is alleged to be. Still, for much of the novel, Coetzee appears to be erecting an allegorical and moralistic edifice: Lurie harms Melanie, refuses to recognize what he’s done, and is subsequently punished by having his own violence rendered bloody and unspeakable on his daughter. Lucy then attempts to defend her rapists with a more righteous version of her father’s defense of himself: her plight, she suggests, is a consequence of the rapacious domination that South African whites have exercised over the country’s black population. As this awful symmetry arises, however, Coetzee simultaneously erases it; the atmosphere of the novel is acidic, hazy, dissolving. All of the characters—including the student protesters who slide a pamphlet reading “ WOMEN SPEAK OUT ” under Lurie’s office door, and who organize a group called Women Against Rape, which Coetzee sardonically abbreviates as “ WAR ”—seem like tiny figures, alive for a vanishing breath of changing weather, caught up in forces they can hardly begin to see.

Lurie is a more readily visible figure now. He is the man who frets about the overreach of #MeToo while demonstrating the tenacity of the attitudes that make such a movement necessary. (In Sigrid Nunez’s novel “ The Friend ,” published in 2018, the narrator describes a character as “one of several Lurian friends I’ve known: reckless, priapic men risking careers, livelihoods, marriages—everything.”) Lurie believes that he is the victim of a purge. “Watchfulness became the watchword; the watchfulness of all over all,” he thinks. After Lucy’s rape, he muses that among the “legions of countesses and kitchenmaids that Byron pushed himself into there were no doubt those who called it rape. But none surely had cause to fear that the session would end with her throat being slit.” That sort of thing, done at knifepoint, is real rape, he—like Weinstein’s defenders—implies. Lurie imagines poor Lucy, numb and mute and dissociating, “frightened near to death.” He understands, he thinks. He “can, if he concentrates, if he loses himself, be there, be the men, inhabit them, fill them with the ghost of himself. The question is, does he have it in him to be the woman?”

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By David Remnick

By Jay Caspian Kang

Disgrace by J.M.Coetzee

general information | review summaries | our review | links | about the author

- Return to top of the page -

A- : impressive, but full of unpleasantness

See our review for fuller assessment.

Review Consensus : Very impressed. From the Reviews : "In its honest and relentless probing of character and motive -- reminiscent of Walker Percy's insightful writings -- this novel secures Coetzee's place among today's major novelists. It deals with love and relationships at their most basic and dark levels -- as paths to both meaning and survival." - John Kennedy, The Antioch Review "It may be that 200 pages have never worked so hard as they do in Coetzee's hands. He's a novelist of stunning precision and efficiency. Disgrace loses none of its fidelity to the social and political complexities of South Africa, even while it explores the troubling tensions between generations, sexes, and races. This is a novel of almost frightening perception from a writer of brutally clear prose." - Ron Charles, Christian Science Monitor "This is a dry, hard novel, not as affecting or as imaginatively fashioned as Coetzee's other Booker winner, Life and Times of Michael K. The characters are so flatly presented that we cannot fully enter into their mental worlds, and the prose is so sparse as to verge on the lazy. (...) But at the same time, Disgrace is a gripping read, paced, shaped, and developed in a way that locks us into the narrative, and threaded with recurring images, like that of fire, which slowly build to an unbearable climax." - Carol Iannone, Commentary "In Sachen David Lurie jedoch hat er sein Mitgefühl ein wenig zu dick aufgetragen. Die eindeutige Symphatielenkung, die er f�r seinen traurigen Helden in Gang setzt, erscheint deshalb etwas aufdringlich, ja kokett. (...) Die herbe Handlung etwa, die er seinen Hauptfiguren aufbürdet, ist vollkommen plausibel, folgerichtig und, man soll das nicht verachten, spannend von der ersten bis zur letzten Seite.(...) Schande ist kein tröstliches Buch. Es ist viel mehr: ein beunruhigender Roman." - Jochen Hieber, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung " Disgrace is a subtle, multi-layered story, as much concerned with politics as it is with the itch of male flesh. Coetzee's prose is chaste and lyrical without being self- conscious: it is a relief to encounter writing as quietly stylish as this. I was not totally convinced by Lurie's musical abilities, with regard to his proposed opera, but that is my sole complaint." - Paul Bailey, The Independent " Disgrace offers an apocalyptic vision of contemporary South Africa. (...) What transforms Disgrace from a good, compelling book into a work of brilliance is its allegorical reach." - Daniel Davies, The Lancet "What makes the book interesting is the contrast between the urban life of an older-generation white male (who cannot escape from pride or principles even when these have led him to a dead end) and the rural life, where suffering, death and brutality are daily occurrences and have to be dealt with if there is to be any life at all. This conflict is no doubt epitomised in South Africa today." - Nicholas Mosley, Literary Review " Disgrace is the best novel Coetzee has written. It is a chilling, spare book, the work of a mature writer who has refined his textual obsessions to produce an exact, effective prose and condensed his thematic concern with authority into a deceptively simple story of family life. Half campus novel, half anti-pastoral, it begins quietly enough in Cape Town. (....) As so often in Coetzee's fiction, the characters in Disgrace have a metonymic or symbolic function." - Elizabeth Lowry, London Review of Books "Yet if it is faith Coetzee confesses, complete with annunciation and sacrifice, the form it takes is an art of stubborn, palpable inquiry. The apartness and pastoral retreat in some of the earlier work find in Disgrace even hints of a future for groups, for the polis." - Joseph McElroy, The Nation "(A) very good novel, almost too good a novel. It knows its limits, and lives within a wary self-governance. It sometimes reads as if it were the winner of an exam whose challenge was to create the perfect specimen of a very good contemporary novel. It is truthful, spare, compelling, often moving, and thematically legible: that is to say, it does not overflow interpretation. It does not rise to greatness, in part because of a certain formal, cognitive, and linguistic neatness -- almost a somber tidiness, if such a thing can be imagined -- that is obscured, and almost successfully subjugated, by what is most powerful about the book, its loose wail of pain, its vigorous honesty." - James Wood, The New Republic "Unable to communicate at the best of times, the characters' relationships crumple completely under the strain of momentous events. Coetzee, meanwhile, maintains the miracle that is his style: a determinedly clipped, abrupt prose that defies the brutality of events by nourishing a poetic vision. The main events, and the threads and stories within stories, all emerge in the end as the same central tale: a tireless reiteration of the impossibility of communication." - Douglas McCabe, New Statesman "The effect of the novel's plot is deeply disturbing, in part because of what happens to David and Lucy, but equally because of the disintegrating context of their experiences. Not even language can be trusted." - Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, The New York Times "This novel stands as one of the few I know in which the writer's use of the present tense is in itself enough to shape the structure and form of the book as a whole. Even though it presents an almost unrelieved series of grim moments, Disgrace isn't claustrophobic or depressing, as some of Coetzee's earlier work has been. Its grammar allows for the sublime exhilaration of accident and surprise, and so the fate of its characters -- and perhaps indeed of their country -- seems not determined but improvised." - Michael Gorra, The New York Times Book Review "The novel's juxtaposed inquiries and trials, for example, constitute a compelling debate over legal and confessional versions of ethics (.....) Similar dialogues are elicited through the novel's repeated scenes of intrusion and its meditations on disgrace, on animality, on the perfective. They are conversations that will not let us have ethical issues wrapped up in lovely clarity, with a bow of clean conscience on top." - Rebecca Saunders, Review of Contemporary Fiction " Disgrace is Coetzee's first book to deal explicitly with post-apartheid South Africa, and the picture it paints is a cheerless one that will comfort no one, no matter what race, nationality or viewpoint. (...) There is something fundamentally cryptic and unsummarizable about Disgrace , but I read it as an almost metaphysical journey from this Romantic variety of love to the harsher, leaner strain David eventually learns from life on and around Lucy's farm." - Andrew O'Hehir, Salon "And though Coetzee's protagonist serves as an impeccable guide into the new South Africa that lies outside the squalor of the townships, that is the least of Coetzee's achievement here. What Disgrace has on its mind is more urgent, more pitiless. In stark, wintry prose, Coetzee unflinchingly examines the absence of consolation; he finds that words are incapable of hiding our common solitude (.....) That he keeps the reader from cowering at such an unhappy subject is testament to the smoothness of his writing, his clinical yet exquisite tone and his unexpected hiccups of humor." - Oscar C. Villalon, San Francisco Chronicle "Coetzee has devised a subtly brilliant commentary on the nature and balance of power in his homeland. (...) Disgrace is a mini-opera without music by a writer at the top of his form. Its bleak vision lingers, shattering any hope of a redemptive state of grace." - Elizabeth Gleick, Time "Lurie is a fascinating, fully realized character, defined throughout the novel in terms of his inability to relate to the women in his life (.....) In fact, Disgrace is not about Lurie's relationship with women, but about what these relationships tell him about himself." - Ranti Williams, Times Literary Supplement " Disgrace is yet another surprise, a straightforward narrative that means just what it says, its real subject perhaps too grim for fashionable "progressive" opinion in its current state. (...) It is the present-day Republic of South Africa, in which, at least in Coetzee's vision, an English professor who seduces a confused student is inevitably disgraced and exiled but three thugs in the countryside can get away with rape, robbery, and attempted murder." - Robert L. Berner, World Literature Today Please note that these ratings solely represent the complete review 's biased interpretation and subjective opinion of the actual reviews and do not claim to accurately reflect or represent the views of the reviewers. Similarly the illustrative quotes chosen here are merely those the complete review subjectively believes represent the tenor and judgment of the review as a whole. We acknowledge (and remind and warn you) that they may, in fact, be entirely unrepresentative of the actual reviews by any other measure.

The complete review 's Review :

'The reason is that, as far as I am concerned, what happened to me is a purely private matter. In another time, in another place it might be held to be a public matter. But in this place, at this time, it is not. It is my business, mine alone.' 'This place being what ?' 'This place being South Africa.'

Wouldn't it have made more sense to call me in before you set them free, to have me identify them ? Now that they are out on bail they wil just disappear. You know that.

Let me not forget this day, he tells himself, lying beside her when they are spent. After the sweet young flesh of Melanie Isaacs, this is what I have come to. This is what I will have to get used to, this and even less.

No. How could I ? But I will. Love will grow -- one can trust Mother Nature for that. I am determined to be a good mother, David. A good mother and a good person.

About the Author :

John M. Coetzee was born in South Africa in 1940. He has won many literary prizes, and was the 2003 Nobel laureate in literature.

© 2004-2023 the complete review Main | the New | the Best | the Rest | Review Index | Links

Accessibility Links

Disgrace by JM Coetzee review — the making of a double Booker winner

Warning: contains spoilers

I would characterise my first reading of Disgrace , when it came out in 1999, as naive. The book is so adroitly put together, its pared-back style so perfectly carpentered for the story of stark suffering it presents, that I willingly surrendered to Coetzee’s mastery of his material. I wasn’t alone in this surrender. Disgrace took on a heavy cargo of global praise and made Coetzee the first double-Booker laureate.

In South Africa, however, unease about the book soon surfaced. Some members of the African National Congress were so dismayed by the novel’s “brutal representation” of its black characters that they brought it to the government’s Human Rights Commission on racism in the media in April 2000. The author pleaded that he

Related articles

- Biggest New Books

- Non-Fiction

- All Categories

- First Readers Club Daily Giveaway

- How It Works

Sober, Searing, and Cynical: J.M. Coetzee's Disgrace

Three of the first reviews of the south african nobel laureate's 1999 booker prize-winning novel.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

J.M. Coetzee, the reclusive South African-born Nobel Laureate and two-time Booker Prize winner, celebrates his eight-first birthday today. Happy birthday, John.

To mark the occasion, let’s look back at some of the earliest reviews of Disgrace , the novel for which Coetzee won his second Booker in 1999 and which has become, in the two decades since its publication, arguably the author’s most famous work.

Disgrace tells the story of fiftysomething English professor David Lurie, who, accused of sexual misconduct with one of his students and relieved of his teaching position, flees Cape Town to go live with his daughter on the Eastern Cape. What follows is a trenchant inquiry into the nature of salvation and self-destruction, and a grim portrait of life in post-Apartheid South Africa.

“When all else fails, philosophize.”

“The novel may not inherently be a dialectical form, but readers are so used to a synthesising process that they may detect one without help from the author. JM Coetzee’s quietly deceptive new novel exploits this reflex, with a narrative that belongs to two opposite types simultaneously, revealing its true allegiance only on the last page—in fact the last sentence.

David Lurie, a divorced university professor in his fifties, leaves Cape Town in disgrace to stay with his daughter Lucy on her smallholding in the Eastern Cape. What follows is somehow simultaneously a story of redemption and of collapse, just as a famous optical illusion is simultaneously a duck and a rabbit, but can only be seen at any one moment as one or the other. The reading mind responds to the possibilities in disconcerting alternation.

“Those who require narratives of healing will find plenty of material from which to construct one: Lurie does some physical work for a change and comes to feel a connection with animals. He helps at a clinic of the Animal Welfare League and supervises the disposal of dogs which have been put down, briefly taking charge of a hospital incinerator each week … But there is also an opposite story, not running parallel to the other but built from the same set of materials. In this narrative, country life is not therapy but ordeal, not a pastoral but a war of attrition. In the new South Africa, the man who was once the kaffir calls the shots. His help must be asked for and his protection sought, particularly by a woman living alone, and it may be that his ambition is to take over the land rather than share it. All this is regarded as just, or at least historically inevitable, but there are patterns that seem to magnify and distort the minor disgrace that did for Lurie in the city; oppression from someone whose role is to protect, sexual predation without even his excuses.

Any novel set in post-apartheid South Africa is fated to be read as a political portrait, but the fascination of Disgrace— a somewhat perverse fascination, as some will feel—is the way it both encourages and contests such a reading by holding extreme alternatives in tension. Salvation, ruin. Even a single paragraph can accommodate the transformation of hope into its opposite.”

–Adam Mars-Jones, The Guardian , July 18, 1999

“There is much one could say about this brief but oddly expansive novel, about the range of concerns that Coetzee has woven seamlessly together. There is Lurie’s attempt, as a specialist in Romantic poetry, to write a long-planned work on Byron, in which he finds himself adopting the voice of the poet’s discarded mistress. There is a profound meditation on another kind of otherness, on the lives and the rights of animals, a topic Coetzee has explored in a recent volume of essays—only here that meditation takes the form of the punishment and salvation that Lurie finds at Bev’s animal shelter, helping her to put down abandoned dogs, holding them ‘as the needle finds the vein and the drug hits the heart and the legs buckle and the eyes dim.’ I could note the way Coetzee makes us understand but not sympathize with Lurie’s intellectual arrogance and incorrigible desire, and could then compare him to his child: each is beyond stubborn, but the daughter is marked by an integrity that her father knows he cannot claim for himself. And I could point to the stark and even schematic armature of the plot that links them, a plot in which what Lurie has in some sense done to another man’s daughter is trebly visited on his own.

There is more in Disgrace than I can manage to describe here. But let me end by suggesting Coetzee’s most impressive achievement, one that grows from the very bones of the novel’s grammar. Lurie thinks of himself as having spent his career ‘explaining to the bored youth of the country the distinction between drink and drink up, burned and burnt. The perfective, signifying an action carried through to its conclusion.’ Disgrace is, however, written in the present tense, and its title denotes a continuing condition. Disgrace continues. And so do the characters’ lives, which at the end of the book remain unresolved and unfinished, their problems and possibilities still open.”

–Michael Gorra, The New York Times , November 28, 1999

“ I n his sober, searing and even cynical little book Disgrace , J.M. Coetzee tells us something we all suspect and fear—that political change can do almost nothing to eliminate human misery. What it can do, he suggests, is reorder it a little and half-accidentally introduce a few new varieties … Disgrace is Coetzee’s first book to deal explicitly with post-apartheid South Africa, and the picture it paints is a cheerless one that will comfort no one, no matter what race, nationality or viewpoint.

“Coetzee has always situated his characters in extreme situations that compel them to explore what it means to be human, and before this novel is over, David must endure both psychological abasement and physical torment. But Coetzee has never before asked so clearly what it is not to be human. Later in the novel, after David has fallen into disgrace and fled Cape Town for his daughter Lucy’s remote farm, she tells him, ‘This is the only life there is. Which we share with animals.’

“There is something fundamentally cryptic and unsummarizable about Disgrace , but I read it as an almost metaphysical journey from this Romantic variety of love to the harsher, leaner strain David eventually learns from life on and around Lucy’s farm … If David actually reclaims some dignity by the end of Disgrace , it is only because he gives up everything, gives up more than a dog ever could—his daughter, his ideas about justice and language, his dream of the opera on Byron and even the dying animals he has learned to love without reservation, without thought for himself.”

–Andrew O’Hehir, Salon , November 5, 1999

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

Get the Book Marks Bulletin

Email address:

- Categories Fiction Fantasy Graphic Novels Historical Horror Literary Literature in Translation Mystery, Crime, & Thriller Poetry Romance Speculative Story Collections Non-Fiction Art Biography Criticism Culture Essays Film & TV Graphic Nonfiction Health History Investigative Journalism Memoir Music Nature Politics Religion Science Social Sciences Sports Technology Travel True Crime

April 1, 2024

- Jhumpa Lahiri shares the syllabus for her recent course

- Thoughts on Trump’s new gig as a Bible salesman

- The life and work of Raymond Williams

Authors & Events

Recommendations

- New & Noteworthy

- Bestsellers

- Popular Series

- The Must-Read Books of 2023

- Popular Books in Spanish

- Coming Soon

- Literary Fiction

- Mystery & Thriller

- Science Fiction

- Spanish Language Fiction

- Biographies & Memoirs

- Spanish Language Nonfiction

- Dark Star Trilogy

- Ramses the Damned

- Penguin Classics

- Award Winners

- The Parenting Book Guide

- Books to Read Before Bed

- Books for Middle Graders

- Trending Series

- Magic Tree House

- The Last Kids on Earth

- Planet Omar

- Beloved Characters

- The World of Eric Carle

- Llama Llama

- Junie B. Jones

- Peter Rabbit

- Board Books

- Picture Books

- Guided Reading Levels

- Middle Grade

- Activity Books

- Trending This Week

- Top Must-Read Romances

- Page-Turning Series To Start Now

- Books to Cope With Anxiety

- Short Reads

- Anti-Racist Resources

- Staff Picks

- Memoir & Fiction

- Features & Interviews

- Emma Brodie Interview

- James Ellroy Interview

- Nicola Yoon Interview

- Qian Julie Wang Interview

- Deepak Chopra Essay

- How Can I Get Published?

- For Book Clubs

- Reese's Book Club

- Oprah’s Book Club

- happy place " data-category="popular" data-location="header">Guide: Happy Place

- the last white man " data-category="popular" data-location="header">Guide: The Last White Man

- Authors & Events >

- Our Authors

- Michelle Obama

- Zadie Smith

- Emily Henry

- Amor Towles

- Colson Whitehead

- In Their Own Words

- Qian Julie Wang

- Patrick Radden Keefe

- Phoebe Robinson

- Emma Brodie

- Ta-Nehisi Coates

- Laura Hankin

- Recommendations >

- 21 Books To Help You Learn Something New

- The Books That Inspired "Saltburn"

- Insightful Therapy Books To Read This Year

- Historical Fiction With Female Protagonists

- Best Thrillers of All Time

- Manga and Graphic Novels

- happy place " data-category="recommendations" data-location="header">Start Reading Happy Place

- How to Make Reading a Habit with James Clear

- Why Reading Is Good for Your Health

- 10 Facts About Taylor Swift

- New Releases

- Memoirs Read by the Author

- Our Most Soothing Narrators

- Press Play for Inspiration

- Audiobooks You Just Can't Pause

- Listen With the Whole Family

Look Inside | Reading Guide

Reading Guide

By J. M. Coetzee

By j. m. coetzee read by michael cumpsty, category: literary fiction, category: literary fiction | audiobooks.

Nov 01, 2000 | ISBN 9780140296402 | 5-1/16 x 7-3/4 --> | ISBN 9780140296402 --> Buy

Jan 03, 2017 | ISBN 9781524705466 | ISBN 9781524705466 --> Buy

May 29, 2008 | 420 Minutes | ISBN 9781436228046 --> Buy

Buy from Other Retailers:

Nov 01, 2000 | ISBN 9780140296402

Jan 03, 2017 | ISBN 9781524705466

May 29, 2008 | ISBN 9781436228046

420 Minutes

Buy the Audiobook Download:

- audiobooks.com

About Disgrace

The provocative Booker Prize winning novel from Nobel laureate, J.M. Coetzee “Compulsively readable… A novel that not only works its spell but makes it impossible for us to lay it aside once we’ve finished reading it.” — The New Yorker At fifty-two, Professor David Lurie is divorced, filled with desire, but lacking in passion. When an affair with a student leaves him jobless, shunned by friends, and ridiculed by his ex-wife, he retreats to his daughter Lucy’s smallholding. David’s visit becomes an extended stay as he attempts to find meaning in his one remaining relationship. Instead, an incident of unimaginable terror and violence forces father and daughter to confront their strained relationship and the equallity complicated racial complexities of the new South Africa. 2024 marks the 25th Anniversary of the publication of Disgrace

Also by J. M. Coetzee

About J. M. Coetzee

Born in Cape Town, South Africa, on February 9, 1940, J. M. Coetzee studied first at Cape Town and later at the University of Texas at Austin, where he earned a PhD degree in literature. In 1972, he returned to South Africa… More about J. M. Coetzee

Product Details

You may also like.

A House for Mr. Biswas

Straight Man

The Death of Vivek Oji

No Longer at Ease

The Beautiful Things That Heaven Bears

The Tortilla Curtain

A Widow for One Year

WINNER OF THE BOOK PRIZE THE NOBEL PRIZE WINNING NOVELIST “Disgrace is not a hard or obscure book — it is, among other things, compulsively readable — but what it may well be is an authentically spiritual document, a lament for the soul of a disgraced century.” —The New Yorker “A subtly brilliant commentary on the nature and balance of power in his homeland…. Disgrace is a mini-opera without music by a writer at the top of his form.” —Time “Mr. Coetzee, in prose lean yet simmering with feeling, has indeed achieved a lasting work: a novel as haunting and powerful as Albert Camus’s The Stranger.” —The Wall Street Journal “A tough, sad, stunning novel.” —Baltimore Sun “A great novel by one of the finest authors writing in the English language today.” – The Times (London) “What is remarkable about Coetzee’s vision as a novelist is that it remains intensely human, rooted in common experience and replete with failure, doubt and frustration.” ― Guardian “Exhilarating… One of the best novelists alive.” ― Sunday Times (London)

Man Booker Prize for Fiction WINNER

Nobel Prize in Literature WINNER

Visit other sites in the Penguin Random House Network

Raise kids who love to read

Today's Top Books

Want to know what people are actually reading right now?

An online magazine for today’s home cook

Just for joining you’ll get personalized recommendations on your dashboard daily and features only for members.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

The Washington Book: How to Read Politics and Politicians review – unpicking the lexicon of America’s leaders

New York Times columnist Carlos Lozada examines the speeches, writing and linguistic tics of presidents and members of Congress to expose ‘inveterate deceivers’

P oliticians mince or mash words for a living, and the virtuosity with which they twist meanings makes them artists of a kind. Their skill at spinning facts counts as a fictional exercise: in political jargon, a “narrative” is a storyline that warps truth for partisan purposes. Carlos Lozada, formerly a reviewer for the Washington Post and now a columnist at the New York Times , specialises in picking apart these professional falsehoods. Analysing windy orations, ghostwritten memoirs and faceless committee reports, the essays in his book expose American presidents, members of Congress and supreme court justices as unreliable narrators, inveterate deceivers who betray themselves in careless verbal slips.

Lozada has a literary critic’s sharp eye, and an alertly cocked ear to go with it. Thus he fixes on a stray remark made by Trump as he rallied the mob that invaded the Capitol in January 2021. Ordering the removal of metal detectors, he said that the guns his supporters toted didn’t bother him, because “they’re not here to hurt me”. Lozada wonders about the emphasis in that phrase: did it neutrally fall on “hurt” or come down hard on “me”? If the latter, it licensed the rampant crowd to hurt Trump’s enemies – for instance by stringing up his disaffected vice-president Mike Pence on a gallows outside the Capitol.

Tiny linguistic tics mark the clash between two versions of America’s fabled past and its prophetic future. Lozada subtly tracks the recurrence of the word “still” in Biden’s speeches – for instance his assertion that the country “still believes in honesty and decency” and is “still a democracy” – and contrasts it with Trump’s reliance on “again”, the capstone of his vow to Make America Great Again. Biden’s “still” defensively fastens on “something good that may be slipping away”, whereas Trump’s “again” blathers about restoring a lost greatness that is never defined. Biden’s evokes “an ideal worth preserving”; Trump’s equivalent summons up an illusion.

At their boldest, Lozada’s politicians trade in inflated tales about origins and predestined outcomes, grandiose narratives that “transcend belief and become a fully formed worldview”. Hence the title of Hillary Clinton’s manifesto It Takes a Village , which borrows an African proverb about child-rearing and uses it to prompt nostalgia for a bygone America. Lozada watches Obama devising and revising a personal myth. Addressed as Barry by his youthful friends, he later insisted on being called Barack and relaunched himself as the embodiment of America’s ethnic inclusivity; his “personalised presidency” treated the office as an extension of “the Obama brand”. In this respect Trump was Obama’s logical successor, extending a personal brand in a bonanza of self-enrichment. The “big lie” about the supposedly stolen 2020 election is another mythological whopper. Trump admitted its falsity on one occasion when he remarked “We lost”, after which he immediately backtracked, adding: “We didn’t lose. We lost in the Democrats’ imagination.”

All this amuses Lozada but also makes him anxious. As an adoptive American – born in Peru, he became a citizen a decade ago – he has a convert’s faith in the country’s ideals, yet he worries about contradictions that the national creed strains to reconcile. A border wall now debars the impoverished masses welcomed by the Statue of Liberty; the sense of community is fractured by “sophisticated engines of division and misinformation”. Surveying dire fictional scenarios about American decline, Lozada notes that the warmongers enjoy “a narrative advantage”: peace is boring, but predictions of a clash with China or an attack by homegrown terrorists excite the electorate by promising shock, awe and an apocalyptic barrage of special effects. Rather than recoiling from Trump, do Americans share his eagerness for desecration and destruction?

Changing only the names of the performers, The Washington Book has a shadowy local replica. Here in Britain, too, ideological posturing has replaced reasoned argument, and buzzwords are squeezed to death by repetition. Whenever Sunak drones on about “delivering for the British people”, I think of him as a Deliveroo gig worker with a cooling takeaway in his backpack, or a weary postman pushing a trolley full of mortgage bills.

Though such verbal vices are international, a difference of scale separates Washington from Westminster. In America, heroic ambition is brought low by errors of judgment or moral flaws that for Lozada recall “the great themes of literature and the great struggles of life”: Kennedy’s risky confrontations with Cuba, Lyndon Johnson mired in Vietnam, Nixon overcome by paranoia. To set against these tragic falls, we have only the comic spectacle of Boris Johnson gurning on a zip wire or Liz Truss vaingloriously granting an interview atop the Empire State Building; neither of them had the good grace to jump off. American politics is dangerously thrilling because it is so consequential for the rest of the world. In Britain we are doomed to sit through a more trivial show, an unfunny farce played out in a theatre that is crumbling around us.

- Politics books

- The Observer

- US politics

Most viewed

- ADMIN AREA MY BOOKSHELF MY DASHBOARD MY PROFILE SIGN OUT SIGN IN

Awards & Accolades

Our Verdict

FALLING FROM DISGRACE

by Tammy Dietz ‧ RELEASE DATE: Nov. 14, 2023

A poignant, absorbing story of overcoming religious trauma.

Dietz explores her religiously conservative upbringing in this debut memoir.