Is Homework Good for Kids? Here’s What the Research Says

A s kids return to school, debate is heating up once again over how they should spend their time after they leave the classroom for the day.

The no-homework policy of a second-grade teacher in Texas went viral last week , earning praise from parents across the country who lament the heavy workload often assigned to young students. Brandy Young told parents she would not formally assign any homework this year, asking students instead to eat dinner with their families, play outside and go to bed early.

But the question of how much work children should be doing outside of school remains controversial, and plenty of parents take issue with no-homework policies, worried their kids are losing a potential academic advantage. Here’s what you need to know:

For decades, the homework standard has been a “10-minute rule,” which recommends a daily maximum of 10 minutes of homework per grade level. Second graders, for example, should do about 20 minutes of homework each night. High school seniors should complete about two hours of homework each night. The National PTA and the National Education Association both support that guideline.

But some schools have begun to give their youngest students a break. A Massachusetts elementary school has announced a no-homework pilot program for the coming school year, lengthening the school day by two hours to provide more in-class instruction. “We really want kids to go home at 4 o’clock, tired. We want their brain to be tired,” Kelly Elementary School Principal Jackie Glasheen said in an interview with a local TV station . “We want them to enjoy their families. We want them to go to soccer practice or football practice, and we want them to go to bed. And that’s it.”

A New York City public elementary school implemented a similar policy last year, eliminating traditional homework assignments in favor of family time. The change was quickly met with outrage from some parents, though it earned support from other education leaders.

New solutions and approaches to homework differ by community, and these local debates are complicated by the fact that even education experts disagree about what’s best for kids.

The research

The most comprehensive research on homework to date comes from a 2006 meta-analysis by Duke University psychology professor Harris Cooper, who found evidence of a positive correlation between homework and student achievement, meaning students who did homework performed better in school. The correlation was stronger for older students—in seventh through 12th grade—than for those in younger grades, for whom there was a weak relationship between homework and performance.

Cooper’s analysis focused on how homework impacts academic achievement—test scores, for example. His report noted that homework is also thought to improve study habits, attitudes toward school, self-discipline, inquisitiveness and independent problem solving skills. On the other hand, some studies he examined showed that homework can cause physical and emotional fatigue, fuel negative attitudes about learning and limit leisure time for children. At the end of his analysis, Cooper recommended further study of such potential effects of homework.

Despite the weak correlation between homework and performance for young children, Cooper argues that a small amount of homework is useful for all students. Second-graders should not be doing two hours of homework each night, he said, but they also shouldn’t be doing no homework.

Not all education experts agree entirely with Cooper’s assessment.

Cathy Vatterott, an education professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, supports the “10-minute rule” as a maximum, but she thinks there is not sufficient proof that homework is helpful for students in elementary school.

“Correlation is not causation,” she said. “Does homework cause achievement, or do high achievers do more homework?”

Vatterott, the author of Rethinking Homework: Best Practices That Support Diverse Needs , thinks there should be more emphasis on improving the quality of homework tasks, and she supports efforts to eliminate homework for younger kids.

“I have no concerns about students not starting homework until fourth grade or fifth grade,” she said, noting that while the debate over homework will undoubtedly continue, she has noticed a trend toward limiting, if not eliminating, homework in elementary school.

The issue has been debated for decades. A TIME cover in 1999 read: “Too much homework! How it’s hurting our kids, and what parents should do about it.” The accompanying story noted that the launch of Sputnik in 1957 led to a push for better math and science education in the U.S. The ensuing pressure to be competitive on a global scale, plus the increasingly demanding college admissions process, fueled the practice of assigning homework.

“The complaints are cyclical, and we’re in the part of the cycle now where the concern is for too much,” Cooper said. “You can go back to the 1970s, when you’ll find there were concerns that there was too little, when we were concerned about our global competitiveness.”

Cooper acknowledged that some students really are bringing home too much homework, and their parents are right to be concerned.

“A good way to think about homework is the way you think about medications or dietary supplements,” he said. “If you take too little, they’ll have no effect. If you take too much, they can kill you. If you take the right amount, you’ll get better.”

More Must-Reads From TIME

- Biden’s Campaign Is In Trouble. Will the Turnaround Plan Work?

- Why We're Spending So Much Money Now

- The Financial Influencers Women Actually Want to Listen To

- Breaker Sunny Choi Is Heading to Paris

- The UAE Is on a Mission to Become an AI Power

- Why TV Can’t Stop Making Silly Shows About Lady Journalists

- The Case for Wearing Shoes in the House

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Katie Reilly at [email protected]

You May Also Like

The Cult of Homework

America’s devotion to the practice stems in part from the fact that it’s what today’s parents and teachers grew up with themselves.

America has long had a fickle relationship with homework. A century or so ago, progressive reformers argued that it made kids unduly stressed , which later led in some cases to district-level bans on it for all grades under seventh. This anti-homework sentiment faded, though, amid mid-century fears that the U.S. was falling behind the Soviet Union (which led to more homework), only to resurface in the 1960s and ’70s, when a more open culture came to see homework as stifling play and creativity (which led to less). But this didn’t last either: In the ’80s, government researchers blamed America’s schools for its economic troubles and recommended ramping homework up once more.

The 21st century has so far been a homework-heavy era, with American teenagers now averaging about twice as much time spent on homework each day as their predecessors did in the 1990s . Even little kids are asked to bring school home with them. A 2015 study , for instance, found that kindergarteners, who researchers tend to agree shouldn’t have any take-home work, were spending about 25 minutes a night on it.

But not without pushback. As many children, not to mention their parents and teachers, are drained by their daily workload, some schools and districts are rethinking how homework should work—and some teachers are doing away with it entirely. They’re reviewing the research on homework (which, it should be noted, is contested) and concluding that it’s time to revisit the subject.

Read: My daughter’s homework is killing me

Hillsborough, California, an affluent suburb of San Francisco, is one district that has changed its ways. The district, which includes three elementary schools and a middle school, worked with teachers and convened panels of parents in order to come up with a homework policy that would allow students more unscheduled time to spend with their families or to play. In August 2017, it rolled out an updated policy, which emphasized that homework should be “meaningful” and banned due dates that fell on the day after a weekend or a break.

“The first year was a bit bumpy,” says Louann Carlomagno, the district’s superintendent. She says the adjustment was at times hard for the teachers, some of whom had been doing their job in a similar fashion for a quarter of a century. Parents’ expectations were also an issue. Carlomagno says they took some time to “realize that it was okay not to have an hour of homework for a second grader—that was new.”

Most of the way through year two, though, the policy appears to be working more smoothly. “The students do seem to be less stressed based on conversations I’ve had with parents,” Carlomagno says. It also helps that the students performed just as well on the state standardized test last year as they have in the past.

Earlier this year, the district of Somerville, Massachusetts, also rewrote its homework policy, reducing the amount of homework its elementary and middle schoolers may receive. In grades six through eight, for example, homework is capped at an hour a night and can only be assigned two to three nights a week.

Jack Schneider, an education professor at the University of Massachusetts at Lowell whose daughter attends school in Somerville, is generally pleased with the new policy. But, he says, it’s part of a bigger, worrisome pattern. “The origin for this was general parental dissatisfaction, which not surprisingly was coming from a particular demographic,” Schneider says. “Middle-class white parents tend to be more vocal about concerns about homework … They feel entitled enough to voice their opinions.”

Schneider is all for revisiting taken-for-granted practices like homework, but thinks districts need to take care to be inclusive in that process. “I hear approximately zero middle-class white parents talking about how homework done best in grades K through two actually strengthens the connection between home and school for young people and their families,” he says. Because many of these parents already feel connected to their school community, this benefit of homework can seem redundant. “They don’t need it,” Schneider says, “so they’re not advocating for it.”

That doesn’t mean, necessarily, that homework is more vital in low-income districts. In fact, there are different, but just as compelling, reasons it can be burdensome in these communities as well. Allison Wienhold, who teaches high-school Spanish in the small town of Dunkerton, Iowa, has phased out homework assignments over the past three years. Her thinking: Some of her students, she says, have little time for homework because they’re working 30 hours a week or responsible for looking after younger siblings.

As educators reduce or eliminate the homework they assign, it’s worth asking what amount and what kind of homework is best for students. It turns out that there’s some disagreement about this among researchers, who tend to fall in one of two camps.

In the first camp is Harris Cooper, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. Cooper conducted a review of the existing research on homework in the mid-2000s , and found that, up to a point, the amount of homework students reported doing correlates with their performance on in-class tests. This correlation, the review found, was stronger for older students than for younger ones.

This conclusion is generally accepted among educators, in part because it’s compatible with “the 10-minute rule,” a rule of thumb popular among teachers suggesting that the proper amount of homework is approximately 10 minutes per night, per grade level—that is, 10 minutes a night for first graders, 20 minutes a night for second graders, and so on, up to two hours a night for high schoolers.

In Cooper’s eyes, homework isn’t overly burdensome for the typical American kid. He points to a 2014 Brookings Institution report that found “little evidence that the homework load has increased for the average student”; onerous amounts of homework, it determined, are indeed out there, but relatively rare. Moreover, the report noted that most parents think their children get the right amount of homework, and that parents who are worried about under-assigning outnumber those who are worried about over-assigning. Cooper says that those latter worries tend to come from a small number of communities with “concerns about being competitive for the most selective colleges and universities.”

According to Alfie Kohn, squarely in camp two, most of the conclusions listed in the previous three paragraphs are questionable. Kohn, the author of The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing , considers homework to be a “reliable extinguisher of curiosity,” and has several complaints with the evidence that Cooper and others cite in favor of it. Kohn notes, among other things, that Cooper’s 2006 meta-analysis doesn’t establish causation, and that its central correlation is based on children’s (potentially unreliable) self-reporting of how much time they spend doing homework. (Kohn’s prolific writing on the subject alleges numerous other methodological faults.)

In fact, other correlations make a compelling case that homework doesn’t help. Some countries whose students regularly outperform American kids on standardized tests, such as Japan and Denmark, send their kids home with less schoolwork , while students from some countries with higher homework loads than the U.S., such as Thailand and Greece, fare worse on tests. (Of course, international comparisons can be fraught because so many factors, in education systems and in societies at large, might shape students’ success.)

Kohn also takes issue with the way achievement is commonly assessed. “If all you want is to cram kids’ heads with facts for tomorrow’s tests that they’re going to forget by next week, yeah, if you give them more time and make them do the cramming at night, that could raise the scores,” he says. “But if you’re interested in kids who know how to think or enjoy learning, then homework isn’t merely ineffective, but counterproductive.”

His concern is, in a way, a philosophical one. “The practice of homework assumes that only academic growth matters, to the point that having kids work on that most of the school day isn’t enough,” Kohn says. What about homework’s effect on quality time spent with family? On long-term information retention? On critical-thinking skills? On social development? On success later in life? On happiness? The research is quiet on these questions.

Another problem is that research tends to focus on homework’s quantity rather than its quality, because the former is much easier to measure than the latter. While experts generally agree that the substance of an assignment matters greatly (and that a lot of homework is uninspiring busywork), there isn’t a catchall rule for what’s best—the answer is often specific to a certain curriculum or even an individual student.

Given that homework’s benefits are so narrowly defined (and even then, contested), it’s a bit surprising that assigning so much of it is often a classroom default, and that more isn’t done to make the homework that is assigned more enriching. A number of things are preserving this state of affairs—things that have little to do with whether homework helps students learn.

Jack Schneider, the Massachusetts parent and professor, thinks it’s important to consider the generational inertia of the practice. “The vast majority of parents of public-school students themselves are graduates of the public education system,” he says. “Therefore, their views of what is legitimate have been shaped already by the system that they would ostensibly be critiquing.” In other words, many parents’ own history with homework might lead them to expect the same for their children, and anything less is often taken as an indicator that a school or a teacher isn’t rigorous enough. (This dovetails with—and complicates—the finding that most parents think their children have the right amount of homework.)

Barbara Stengel, an education professor at Vanderbilt University’s Peabody College, brought up two developments in the educational system that might be keeping homework rote and unexciting. The first is the importance placed in the past few decades on standardized testing, which looms over many public-school classroom decisions and frequently discourages teachers from trying out more creative homework assignments. “They could do it, but they’re afraid to do it, because they’re getting pressure every day about test scores,” Stengel says.

Second, she notes that the profession of teaching, with its relatively low wages and lack of autonomy, struggles to attract and support some of the people who might reimagine homework, as well as other aspects of education. “Part of why we get less interesting homework is because some of the people who would really have pushed the limits of that are no longer in teaching,” she says.

“In general, we have no imagination when it comes to homework,” Stengel says. She wishes teachers had the time and resources to remake homework into something that actually engages students. “If we had kids reading—anything, the sports page, anything that they’re able to read—that’s the best single thing. If we had kids going to the zoo, if we had kids going to parks after school, if we had them doing all of those things, their test scores would improve. But they’re not. They’re going home and doing homework that is not expanding what they think about.”

“Exploratory” is one word Mike Simpson used when describing the types of homework he’d like his students to undertake. Simpson is the head of the Stone Independent School, a tiny private high school in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, that opened in 2017. “We were lucky to start a school a year and a half ago,” Simpson says, “so it’s been easy to say we aren’t going to assign worksheets, we aren’t going assign regurgitative problem sets.” For instance, a half-dozen students recently built a 25-foot trebuchet on campus.

Simpson says he thinks it’s a shame that the things students have to do at home are often the least fulfilling parts of schooling: “When our students can’t make the connection between the work they’re doing at 11 o’clock at night on a Tuesday to the way they want their lives to be, I think we begin to lose the plot.”

When I talked with other teachers who did homework makeovers in their classrooms, I heard few regrets. Brandy Young, a second-grade teacher in Joshua, Texas, stopped assigning take-home packets of worksheets three years ago, and instead started asking her students to do 20 minutes of pleasure reading a night. She says she’s pleased with the results, but she’s noticed something funny. “Some kids,” she says, “really do like homework.” She’s started putting out a bucket of it for students to draw from voluntarily—whether because they want an additional challenge or something to pass the time at home.

Chris Bronke, a high-school English teacher in the Chicago suburb of Downers Grove, told me something similar. This school year, he eliminated homework for his class of freshmen, and now mostly lets students study on their own or in small groups during class time. It’s usually up to them what they work on each day, and Bronke has been impressed by how they’ve managed their time.

In fact, some of them willingly spend time on assignments at home, whether because they’re particularly engaged, because they prefer to do some deeper thinking outside school, or because they needed to spend time in class that day preparing for, say, a biology test the following period. “They’re making meaningful decisions about their time that I don’t think education really ever gives students the experience, nor the practice, of doing,” Bronke said.

The typical prescription offered by those overwhelmed with homework is to assign less of it—to subtract. But perhaps a more useful approach, for many classrooms, would be to create homework only when teachers and students believe it’s actually needed to further the learning that takes place in class—to start with nothing, and add as necessary.

Read our research on: TikTok | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

What we know about online learning and the homework gap amid the pandemic.

America’s K-12 students are returning to classrooms this fall after 18 months of virtual learning at home during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some students who lacked the home internet connectivity needed to finish schoolwork during this time – an experience often called the “ homework gap ” – may continue to feel the effects this school year.

Here is what Pew Research Center surveys found about the students most likely to be affected by the homework gap and their experiences learning from home.

Children across the United States are returning to physical classrooms this fall after 18 months at home, raising questions about how digital disparities at home will affect the existing homework gap between certain groups of students.

Methodology for each Pew Research Center poll can be found at the links in the post.

With the exception of the 2018 survey, everyone who took part in the surveys is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

The 2018 data on U.S. teens comes from a Center poll of 743 U.S. teens ages 13 to 17 conducted March 7 to April 10, 2018, using the NORC AmeriSpeak panel. AmeriSpeak is a nationally representative, probability-based panel of the U.S. household population. Randomly selected U.S. households are sampled with a known, nonzero probability of selection from the NORC National Frame, and then contacted by U.S. mail, telephone or face-to-face interviewers. Read more details about the NORC AmeriSpeak panel methodology .

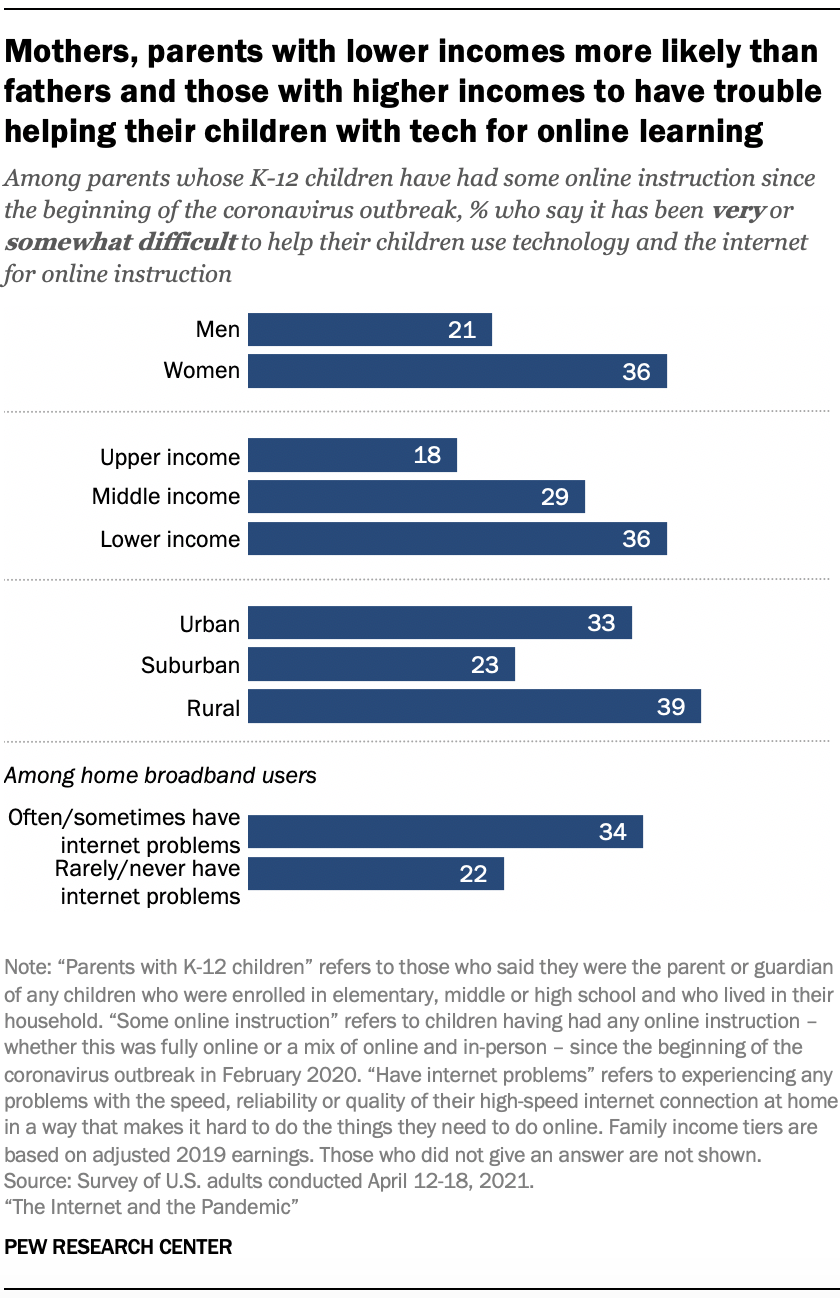

Around nine-in-ten U.S. parents with K-12 children at home (93%) said their children have had some online instruction since the coronavirus outbreak began in February 2020, and 30% of these parents said it has been very or somewhat difficult for them to help their children use technology or the internet as an educational tool, according to an April 2021 Pew Research Center survey .

Gaps existed for certain groups of parents. For example, parents with lower and middle incomes (36% and 29%, respectively) were more likely to report that this was very or somewhat difficult, compared with just 18% of parents with higher incomes.

This challenge was also prevalent for parents in certain types of communities – 39% of rural residents and 33% of urban residents said they have had at least some difficulty, compared with 23% of suburban residents.

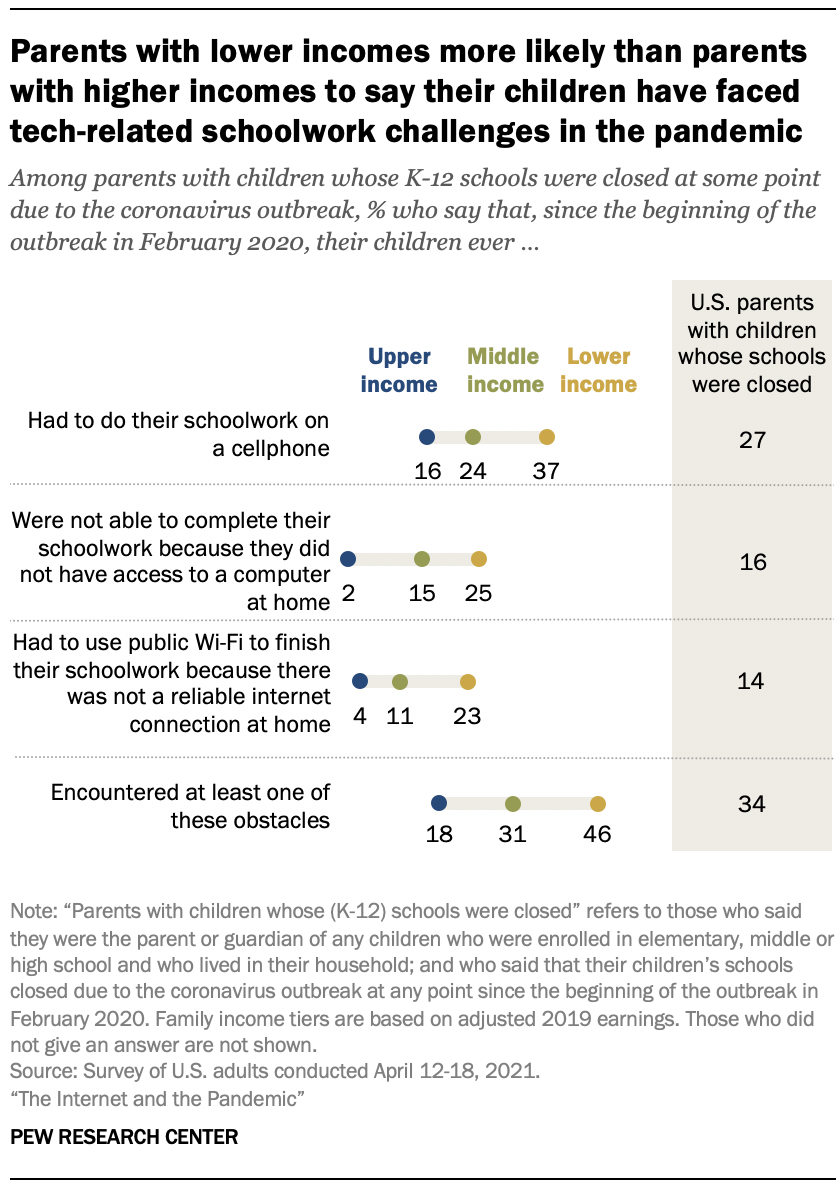

Around a third of parents with children whose schools were closed during the pandemic (34%) said that their child encountered at least one technology-related obstacle to completing their schoolwork during that time. In the April 2021 survey, the Center asked parents of K-12 children whose schools had closed at some point about whether their children had faced three technology-related obstacles. Around a quarter of parents (27%) said their children had to do schoolwork on a cellphone, 16% said their child was unable to complete schoolwork because of a lack of computer access at home, and another 14% said their child had to use public Wi-Fi to finish schoolwork because there was no reliable connection at home.

Parents with lower incomes whose children’s schools closed amid COVID-19 were more likely to say their children faced technology-related obstacles while learning from home. Nearly half of these parents (46%) said their child faced at least one of the three obstacles to learning asked about in the survey, compared with 31% of parents with midrange incomes and 18% of parents with higher incomes.

Of the three obstacles asked about in the survey, parents with lower incomes were most likely to say that their child had to do their schoolwork on a cellphone (37%). About a quarter said their child was unable to complete their schoolwork because they did not have computer access at home (25%), or that they had to use public Wi-Fi because they did not have a reliable internet connection at home (23%).

A Center survey conducted in April 2020 found that, at that time, 59% of parents with lower incomes who had children engaged in remote learning said their children would likely face at least one of the obstacles asked about in the 2021 survey.

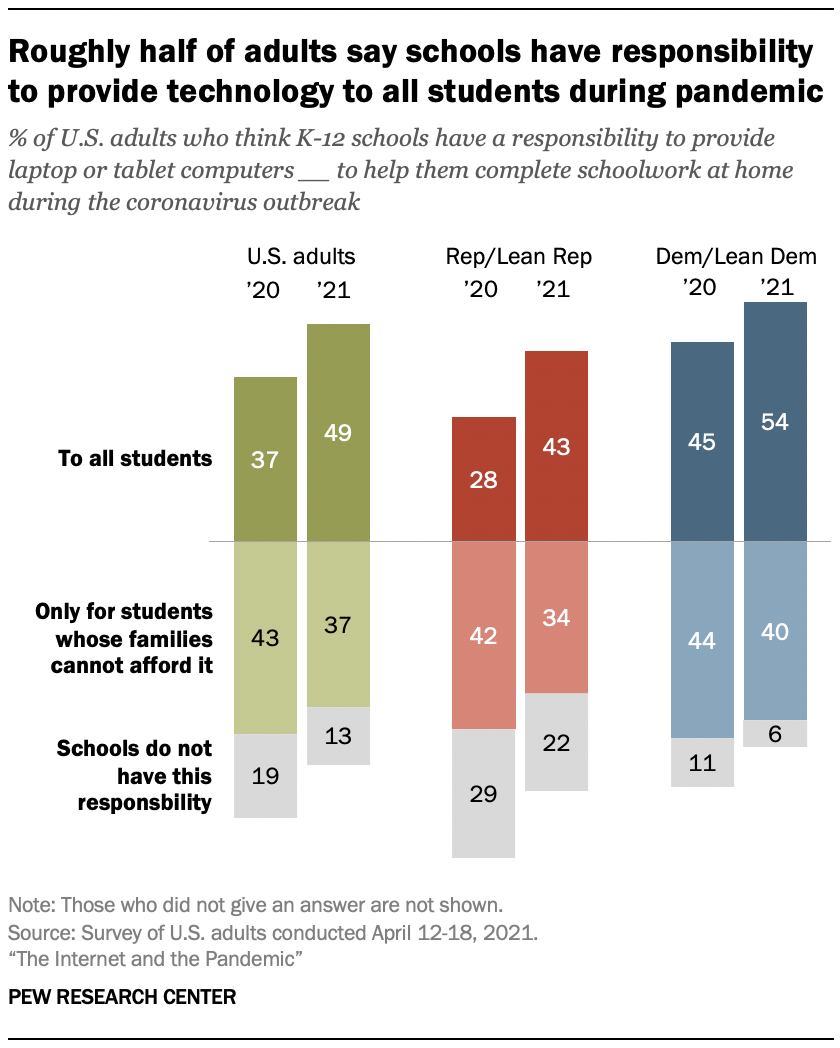

A year into the outbreak, an increasing share of U.S. adults said that K-12 schools have a responsibility to provide all students with laptop or tablet computers in order to help them complete their schoolwork at home during the pandemic. About half of all adults (49%) said this in the spring 2021 survey, up 12 percentage points from a year earlier. An additional 37% of adults said that schools should provide these resources only to students whose families cannot afford them, and just 13% said schools do not have this responsibility.

While larger shares of both political parties in April 2021 said K-12 schools have a responsibility to provide computers to all students in order to help them complete schoolwork at home, there was a 15-point change among Republicans: 43% of Republicans and those who lean to the Republican Party said K-12 schools have this responsibility, compared with 28% last April. In the 2021 survey, 22% of Republicans also said schools do not have this responsibility at all, compared with 6% of Democrats and Democratic leaners.

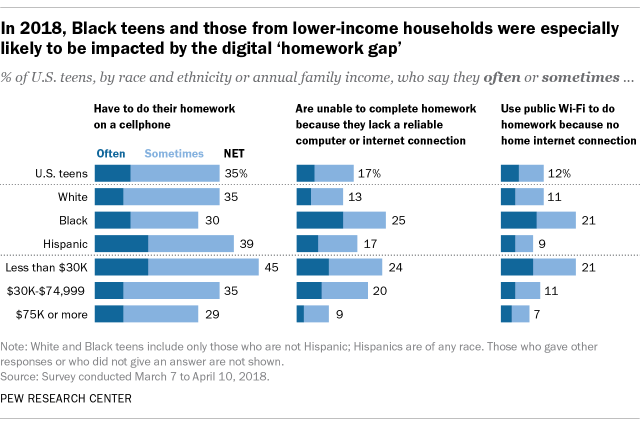

Even before the pandemic, Black teens and those living in lower-income households were more likely than other groups to report trouble completing homework assignments because they did not have reliable technology access. Nearly one-in-five teens ages 13 to 17 (17%) said they are often or sometimes unable to complete homework assignments because they do not have reliable access to a computer or internet connection, a 2018 Center survey of U.S. teens found.

One-quarter of Black teens said they were at least sometimes unable to complete their homework due to a lack of digital access, including 13% who said this happened to them often. Just 4% of White teens and 6% of Hispanic teens said this often happened to them. (There were not enough Asian respondents in the survey sample to be broken out into a separate analysis.)

A wide gap also existed by income level: 24% of teens whose annual family income was less than $30,000 said the lack of a dependable computer or internet connection often or sometimes prohibited them from finishing their homework, but that share dropped to 9% among teens who lived in households earning $75,000 or more a year.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivered Saturday mornings

What federal education data shows about students with disabilities in the U.S.

Most americans who go to religious services say they would trust their clergy’s advice on covid-19 vaccines, unvaccinated americans are at higher risk from covid-19 but express less concern than vaccinated adults, americans who relied most on trump for covid-19 news among least likely to be vaccinated, most popular.

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

- Our Mission

What’s the Right Amount of Homework?

Decades of research show that homework has some benefits, especially for students in middle and high school—but there are risks to assigning too much.

Many teachers and parents believe that homework helps students build study skills and review concepts learned in class. Others see homework as disruptive and unnecessary, leading to burnout and turning kids off to school. Decades of research show that the issue is more nuanced and complex than most people think: Homework is beneficial, but only to a degree. Students in high school gain the most, while younger kids benefit much less.

The National PTA and the National Education Association support the “ 10-minute homework guideline ”—a nightly 10 minutes of homework per grade level. But many teachers and parents are quick to point out that what matters is the quality of the homework assigned and how well it meets students’ needs, not the amount of time spent on it.

The guideline doesn’t account for students who may need to spend more—or less—time on assignments. In class, teachers can make adjustments to support struggling students, but at home, an assignment that takes one student 30 minutes to complete may take another twice as much time—often for reasons beyond their control. And homework can widen the achievement gap, putting students from low-income households and students with learning disabilities at a disadvantage.

However, the 10-minute guideline is useful in setting a limit: When kids spend too much time on homework, there are real consequences to consider.

Small Benefits for Elementary Students

As young children begin school, the focus should be on cultivating a love of learning, and assigning too much homework can undermine that goal. And young students often don’t have the study skills to benefit fully from homework, so it may be a poor use of time (Cooper, 1989 ; Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). A more effective activity may be nightly reading, especially if parents are involved. The benefits of reading are clear: If students aren’t proficient readers by the end of third grade, they’re less likely to succeed academically and graduate from high school (Fiester, 2013 ).

For second-grade teacher Jacqueline Fiorentino, the minor benefits of homework did not outweigh the potential drawback of turning young children against school at an early age, so she experimented with dropping mandatory homework. “Something surprising happened: They started doing more work at home,” Fiorentino writes . “This inspiring group of 8-year-olds used their newfound free time to explore subjects and topics of interest to them.” She encouraged her students to read at home and offered optional homework to extend classroom lessons and help them review material.

Moderate Benefits for Middle School Students

As students mature and develop the study skills necessary to delve deeply into a topic—and to retain what they learn—they also benefit more from homework. Nightly assignments can help prepare them for scholarly work, and research shows that homework can have moderate benefits for middle school students (Cooper et al., 2006 ). Recent research also shows that online math homework, which can be designed to adapt to students’ levels of understanding, can significantly boost test scores (Roschelle et al., 2016 ).

There are risks to assigning too much, however: A 2015 study found that when middle school students were assigned more than 90 to 100 minutes of daily homework, their math and science test scores began to decline (Fernández-Alonso, Suárez-Álvarez, & Muñiz, 2015 ). Crossing that upper limit can drain student motivation and focus. The researchers recommend that “homework should present a certain level of challenge or difficulty, without being so challenging that it discourages effort.” Teachers should avoid low-effort, repetitive assignments, and assign homework “with the aim of instilling work habits and promoting autonomous, self-directed learning.”

In other words, it’s the quality of homework that matters, not the quantity. Brian Sztabnik, a veteran middle and high school English teacher, suggests that teachers take a step back and ask themselves these five questions :

- How long will it take to complete?

- Have all learners been considered?

- Will an assignment encourage future success?

- Will an assignment place material in a context the classroom cannot?

- Does an assignment offer support when a teacher is not there?

More Benefits for High School Students, but Risks as Well

By the time they reach high school, students should be well on their way to becoming independent learners, so homework does provide a boost to learning at this age, as long as it isn’t overwhelming (Cooper et al., 2006 ; Marzano & Pickering, 2007 ). When students spend too much time on homework—more than two hours each night—it takes up valuable time to rest and spend time with family and friends. A 2013 study found that high school students can experience serious mental and physical health problems, from higher stress levels to sleep deprivation, when assigned too much homework (Galloway, Conner, & Pope, 2013 ).

Homework in high school should always relate to the lesson and be doable without any assistance, and feedback should be clear and explicit.

Teachers should also keep in mind that not all students have equal opportunities to finish their homework at home, so incomplete homework may not be a true reflection of their learning—it may be more a result of issues they face outside of school. They may be hindered by issues such as lack of a quiet space at home, resources such as a computer or broadband connectivity, or parental support (OECD, 2014 ). In such cases, giving low homework scores may be unfair.

Since the quantities of time discussed here are totals, teachers in middle and high school should be aware of how much homework other teachers are assigning. It may seem reasonable to assign 30 minutes of daily homework, but across six subjects, that’s three hours—far above a reasonable amount even for a high school senior. Psychologist Maurice Elias sees this as a common mistake: Individual teachers create homework policies that in aggregate can overwhelm students. He suggests that teachers work together to develop a school-wide homework policy and make it a key topic of back-to-school night and the first parent-teacher conferences of the school year.

Parents Play a Key Role

Homework can be a powerful tool to help parents become more involved in their child’s learning (Walker et al., 2004 ). It can provide insights into a child’s strengths and interests, and can also encourage conversations about a child’s life at school. If a parent has positive attitudes toward homework, their children are more likely to share those same values, promoting academic success.

But it’s also possible for parents to be overbearing, putting too much emphasis on test scores or grades, which can be disruptive for children (Madjar, Shklar, & Moshe, 2015 ). Parents should avoid being overly intrusive or controlling—students report feeling less motivated to learn when they don’t have enough space and autonomy to do their homework (Orkin, May, & Wolf, 2017 ; Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008 ; Silinskas & Kikas, 2017 ). So while homework can encourage parents to be more involved with their kids, it’s important to not make it a source of conflict.

Homework in America

- 2014 Brown Center Report on American Education

Subscribe to the Brown Center on Education Policy Newsletter

Tom loveless tom loveless former brookings expert @tomloveless99.

March 18, 2014

- 18 min read

Part II of the 2014 Brown Center Report on American Education

Homework! The topic, no, just the word itself, sparks controversy. It has for a long time. In 1900, Edward Bok, editor of the Ladies Home Journal , published an impassioned article, “A National Crime at the Feet of Parents,” accusing homework of destroying American youth. Drawing on the theories of his fellow educational progressive, psychologist G. Stanley Hall (who has since been largely discredited), Bok argued that study at home interfered with children’s natural inclination towards play and free movement, threatened children’s physical and mental health, and usurped the right of parents to decide activities in the home.

The Journal was an influential magazine, especially with parents. An anti-homework campaign burst forth that grew into a national crusade. [i] School districts across the land passed restrictions on homework, culminating in a 1901 statewide prohibition of homework in California for any student under the age of 15. The crusade would remain powerful through 1913, before a world war and other concerns bumped it from the spotlight. Nevertheless, anti-homework sentiment would remain a touchstone of progressive education throughout the twentieth century. As a political force, it would lie dormant for years before bubbling up to mobilize proponents of free play and “the whole child.” Advocates would, if educators did not comply, seek to impose homework restrictions through policy making.

Our own century dawned during a surge of anti-homework sentiment. From 1998 to 2003, Newsweek , TIME , and People , all major national publications at the time, ran cover stories on the evils of homework. TIME ’s 1999 story had the most provocative title, “The Homework Ate My Family: Kids Are Dazed, Parents Are Stressed, Why Piling On Is Hurting Students.” People ’s 2003 article offered a call to arms: “Overbooked: Four Hours of Homework for a Third Grader? Exhausted Kids (and Parents) Fight Back.” Feature stories about students laboring under an onerous homework burden ran in newspapers from coast to coast. Photos of angst ridden children became a journalistic staple.

The 2003 Brown Center Report on American Education included a study investigating the homework controversy. Examining the most reliable empirical evidence at the time, the study concluded that the dramatic claims about homework were unfounded. An overwhelming majority of students, at least two-thirds, depending on age, had an hour or less of homework each night. Surprisingly, even the homework burden of college-bound high school seniors was discovered to be rather light, less than an hour per night or six hours per week. Public opinion polls also contradicted the prevailing story. Parents were not up in arms about homework. Most said their children’s homework load was about right. Parents wanting more homework out-numbered those who wanted less.

Now homework is in the news again. Several popular anti-homework books fill store shelves (whether virtual or brick and mortar). [ii] The documentary Race to Nowhere depicts homework as one aspect of an overwrought, pressure-cooker school system that constantly pushes students to perform and destroys their love of learning. The film’s website claims over 6,000 screenings in more than 30 countries. In 2011, the New York Times ran a front page article about the homework restrictions adopted by schools in Galloway, NJ, describing “a wave of districts across the nation trying to remake homework amid concerns that high stakes testing and competition for college have fueled a nightly grind that is stressing out children and depriving them of play and rest, yet doing little to raise achievement, especially in elementary grades.” In the article, Vicki Abeles, the director of Race to Nowhere , invokes the indictment of homework lodged a century ago, declaring, “The presence of homework is negatively affecting the health of our young people and the quality of family time.” [iii]

A petition for the National PTA to adopt “healthy homework guidelines” on change.org currently has 19,000 signatures. In September 2013, Atlantic featured an article, “My Daughter’s Homework is Killing Me,” by a Manhattan writer who joined his middle school daughter in doing her homework for a week. Most nights the homework took more than three hours to complete.

The Current Study

A decade has passed since the last Brown Center Report study of homework, and it’s time for an update. How much homework do American students have today? Has the homework burden increased, gone down, or remained about the same? What do parents think about the homework load?

A word on why such a study is important. It’s not because the popular press is creating a fiction. The press accounts are built on the testimony of real students and real parents, people who are very unhappy with the amount of homework coming home from school. These unhappy people are real—but they also may be atypical. Their experiences, as dramatic as they are, may not represent the common experience of American households with school-age children. In the analysis below, data are analyzed from surveys that are methodologically designed to produce reliable information about the experiences of all Americans. Some of the surveys have existed long enough to illustrate meaningful trends. The question is whether strong empirical evidence confirms the anecdotes about overworked kids and outraged parents.

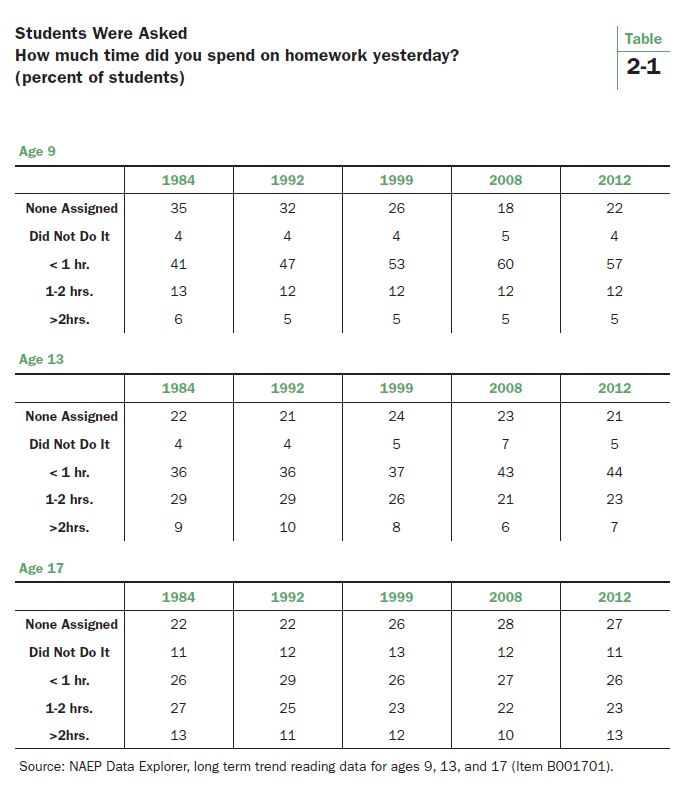

Data from the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) provide a good look at trends in homework for nearly the past three decades. Table 2-1 displays NAEP data from 1984-2012. The data are from the long-term trend NAEP assessment’s student questionnaire, a survey of homework practices featuring both consistently-worded questions and stable response categories. The question asks: “How much time did you spend on homework yesterday?” Responses are shown for NAEP’s three age groups: 9, 13, and 17. [iv]

Today’s youngest students seem to have more homework than in the past. The first three rows of data for age 9 reveal a shift away from students having no homework, declining from 35% in 1984 to 22% in 2012. A slight uptick occurred from the low of 18% in 2008, however, so the trend may be abating. The decline of the “no homework” group is matched by growth in the percentage of students with less than an hour’s worth, from 41% in 1984 to 57% in 2012. The share of students with one to two hours of homework changed very little over the entire 28 years, comprising 12% of students in 2012. The group with the heaviest load, more than two hours of homework, registered at 5% in 2012. It was 6% in 1984.

The amount of homework for 13-year-olds appears to have lightened slightly. Students with one to two hours of homework declined from 29% to 23%. The next category down (in terms of homework load), students with less than an hour, increased from 36% to 44%. One can see, by combining the bottom two rows, that students with an hour or more of homework declined steadily from 1984 to 2008 (falling from 38% to 27%) and then ticked up to 30% in 2012. The proportion of students with the heaviest load, more than two hours, slipped from 9% in 1984 to 7% in 2012 and ranged between 7-10% for the entire period.

For 17-year-olds, the homework burden has not varied much. The percentage of students with no homework has increased from 22% to 27%. Most of that gain occurred in the 1990s. Also note that the percentage of 17-year-olds who had homework but did not do it was 11% in 2012, the highest for the three NAEP age groups. Adding that number in with the students who didn’t have homework in the first place means that more than one-third of seventeen year olds (38%) did no homework on the night in question in 2012. That compares with 33% in 1984. The segment of the 17-year-old population with more than two hours of homework, from which legitimate complaints of being overworked might arise, has been stuck in the 10%-13% range.

The NAEP data point to four main conclusions:

- With one exception, the homework load has remained remarkably stable since 1984.

- The exception is nine-year-olds. They have experienced an increase in homework, primarily because many students who once did not have any now have some. The percentage of nine-year-olds with no homework fell by 13 percentage points, and the percentage with less than an hour grew by 16 percentage points.

- Of the three age groups, 17-year-olds have the most bifurcated distribution of the homework burden. They have the largest percentage of kids with no homework (especially when the homework shirkers are added in) and the largest percentage with more than two hours.

- NAEP data do not support the idea that a large and growing number of students have an onerous amount of homework. For all three age groups, only a small percentage of students report more than two hours of homework. For 1984-2012, the size of the two hours or more groups ranged from 5-6% for age 9, 6-10% for age 13, and 10-13% for age 17.

Note that the item asks students how much time they spent on homework “yesterday.” That phrasing has the benefit of immediacy, asking for an estimate of precise, recent behavior rather than an estimate of general behavior for an extended, unspecified period. But misleading responses could be generated if teachers lighten the homework of NAEP participants on the night before the NAEP test is given. That’s possible. [v] Such skewing would not affect trends if it stayed about the same over time and in the same direction (teachers assigning less homework than usual on the day before NAEP). Put another way, it would affect estimates of the amount of homework at any single point in time but not changes in the amount of homework between two points in time.

A check for possible skewing is to compare the responses above with those to another homework question on the NAEP questionnaire from 1986-2004 but no longer in use. [vi] It asked students, “How much time do you usually spend on homework each day?” Most of the response categories have different boundaries from the “last night” question, making the data incomparable. But the categories asking about no homework are comparable. Responses indicating no homework on the “usual” question in 2004 were: 2% for age 9-year-olds, 5% for 13 year olds, and 12% for 17-year-olds. These figures are much less than the ones reported in Table 2-1 above. The “yesterday” data appear to overstate the proportion of students typically receiving no homework.

The story is different for the “heavy homework load” response categories. The “usual” question reported similar percentages as the “yesterday” question. The categories representing the most amount of homework were “more than one hour” for age 9 and “more than two hours” for ages 13 and 17. In 2004, 12% of 9-year-olds said they had more than one hour of daily homework, while 8% of 13-year-olds and 12% of 17-year-olds said they had more than two hours. For all three age groups, those figures declined from1986 to 2004. The decline for age 17 was quite large, falling from 17% in 1986 to 12% in 2004.

The bottom line: regardless of how the question is posed, NAEP data do not support the view that the homework burden is growing, nor do they support the belief that the proportion of students with a lot of homework has increased in recent years. The proportion of students with no homework is probably under-reported on the long-term trend NAEP. But the upper bound of students with more than two hours of daily homework appears to be about 15%–and that is for students in their final years of high school.

College Freshmen Look Back

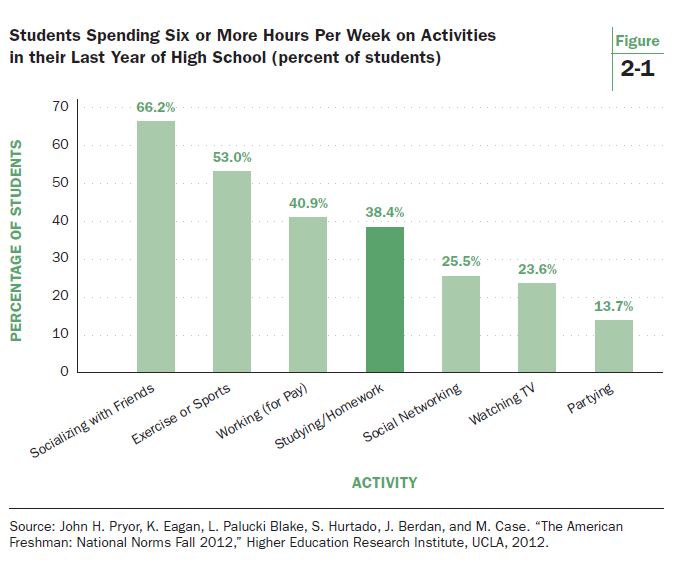

There is another good source of information on high school students’ homework over several decades. The Higher Education Research Institute at UCLA conducts an annual survey of college freshmen that began in 1966. In 1986, the survey started asking a series of questions regarding how students spent time in the final year of high school. Figure 2-1 shows the 2012 percentages for the dominant activities. More than half of college freshmen say they spent at least six hours per week socializing with friends (66.2%) and exercising/sports (53.0%). About 40% devoted that much weekly time to paid employment.

Homework comes in fourth pace. Only 38.4% of students said they spent at least six hours per week studying or doing homework. When these students were high school seniors, it was not an activity central to their out of school lives. That is quite surprising. Think about it. The survey is confined to the nation’s best students, those attending college. Gone are high school dropouts. Also not included are students who go into the military or attain full time employment immediately after high school. And yet only a little more than one-third of the sampled students, devoted more than six hours per week to homework and studying when they were on the verge of attending college.

Another notable finding from the UCLA survey is how the statistic is trending (see Figure 2-2). In 1986, 49.5% reported spending six or more hours per week studying and doing homework. By 2002, the proportion had dropped to 33.4%. In 2012, as noted in Figure 2-1, the statistic had bounced off the historical lows to reach 38.4%. It is slowly rising but still sits sharply below where it was in 1987.

What Do Parents Think?

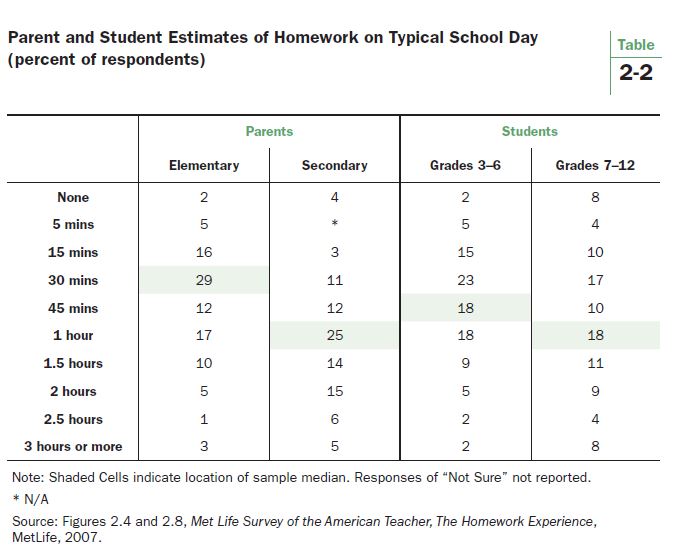

Met Life has published an annual survey of teachers since 1984. In 1987 and 2007, the survey included questions focusing on homework and expanded to sample both parents and students on the topic. Data are broken out for secondary and elementary parents and for students in grades 3-6 and grades 7-12 (the latter not being an exact match with secondary parents because of K-8 schools).

Table 2-2 shows estimates of homework from the 2007 survey. Respondents were asked to estimate the amount of homework on a typical school day (Monday-Friday). The median estimate of each group of respondents is shaded. As displayed in the first column, the median estimate for parents of an elementary student is that their child devotes about 30 minutes to homework on the typical weekday. Slightly more than half (52%) estimate 30 minutes or less; 48% estimate 45 minutes or more. Students in grades 3-6 (third column) give a median estimate that is a bit higher than their parents’ (45 minutes), with almost two-thirds (63%) saying 45 minutes or less is the typical weekday homework load.

One hour of homework is the median estimate for both secondary parents and students in grade 7-12, with 55% of parents reporting an hour or less and about two-thirds (67%) of students reporting the same. As for the prevalence of the heaviest homework loads, 11% of secondary parents say their children spend more than two hours on weekday homework, and 12% is the corresponding figure for students in grades 7-12.

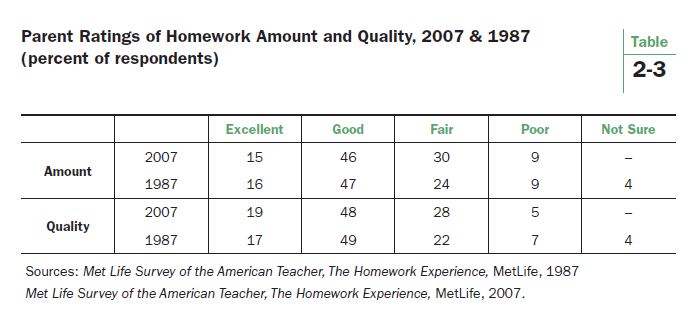

The Met Life surveys in 1987 and 2007 asked parents to evaluate the amount and quality of homework. Table 2-3 displays the results. There was little change over the two decades separating the two surveys. More than 60% of parents rate the amount of homework as good or excellent, and about two-thirds give such high ratings to the quality of the homework their children are receiving. The proportion giving poor ratings to either the quantity or quality of homework did not exceed 10% on either survey.

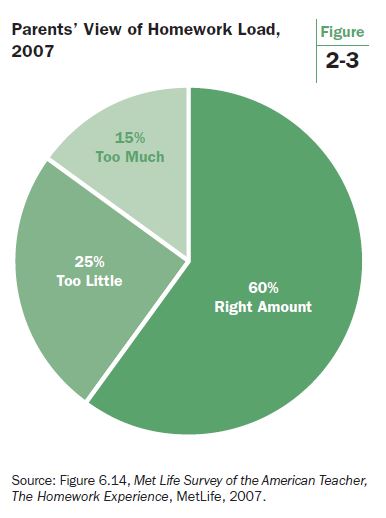

Parental dissatisfaction with homework comes in two forms: those who feel schools give too much homework and those who feel schools do not give enough. The current wave of journalism about unhappy parents is dominated by those who feel schools give too much homework. How big is this group? Not very big (see Figure 2-3). On the Met Life survey, 60% of parents felt schools were giving the right amount of homework, 25% wanted more homework, and only 15% wanted less.

National surveys on homework are infrequent, but the 2006-2007 period had more than one. A poll conducted by Public Agenda in 2006 reported similar numbers as the Met Life survey: 68% of parents describing the homework load as “about right,” 20% saying there is “too little homework,” and 11% saying there is “too much homework.” A 2006 AP-AOL poll found the highest percentage of parents reporting too much homework, 19%. But even in that poll, they were outnumbered by parents believing there is too little homework (23%), and a clear majority (57%) described the load as “about right.” A 2010 local survey of Chicago parents conducted by the Chicago Tribune reported figures similar to those reported above: approximately two-thirds of parents saying their children’s homework load is “about right,” 21% saying it’s not enough, and 12% responding that the homework load is too much.

Summary and Discussion

In recent years, the press has been filled with reports of kids over-burdened with homework and parents rebelling against their children’s oppressive workload. The data assembled above call into question whether that portrait is accurate for the typical American family. Homework typically takes an hour per night. The homework burden of students rarely exceeds two hours a night. The upper limit of students with two or more hours per night is about 15% nationally—and that is for juniors or seniors in high school. For younger children, the upper boundary is about 10% who have such a heavy load. Polls show that parents who want less homework range from 10%-20%, and that they are outnumbered—in every national poll on the homework question—by parents who want more homework, not less. The majority of parents describe their children’s homework burden as about right.

So what’s going on? Where are the homework horror stories coming from?

The Met Life survey of parents is able to give a few hints, mainly because of several questions that extend beyond homework to other aspects of schooling. The belief that homework is burdensome is more likely held by parents with a larger set of complaints and concerns. They are alienated from their child’s school. About two in five parents (19%) don’t believe homework is important. Compared to other parents, these parents are more likely to say too much homework is assigned (39% vs. 9%), that what is assigned is just busywork (57% vs. 36%), and that homework gets in the way of their family spending time together (51% vs. 15%). They are less likely to rate the quality of homework as excellent (3% vs. 23%) or to rate the availability and responsiveness of teachers as excellent (18% vs. 38%). [vii]

They can also convince themselves that their numbers are larger than they really are. Karl Taro Greenfeld, the author of the Atlantic article mentioned above, seems to fit that description. “Every parent I know in New York City comments on how much homework their children have,” Mr. Greenfeld writes. As for those parents who do not share this view? “There is always a clique of parents who are happy with the amount of homework. In fact, they would prefer more . I tend not to get along with that type of parent.” [viii]

Mr. Greenfeld’s daughter attends a selective exam school in Manhattan, known for its rigorous expectations and, yes, heavy homework load. He had also complained about homework in his daughter’s previous school in Brentwood, CA. That school was a charter school. After Mr. Greenfeld emailed several parents expressing his complaints about homework in that school, the school’s vice-principal accused Mr. Greenfeld of cyberbullying. The lesson here is that even schools of choice are not immune from complaints about homework.

The homework horror stories need to be read in a proper perspective. They seem to originate from the very personal discontents of a small group of parents. They do not reflect the experience of the average family with a school-age child. That does not diminish these stories’ power to command the attention of school officials or even the public at large. But it also suggests a limited role for policy making in settling such disputes. Policy is a blunt instrument. Educators, parents, and kids are in the best position to resolve complaints about homework on a case by case basis. Complaints about homework have existed for more than a century, and they show no signs of going away.

Part II Notes:

[i]Brian Gill and Steven Schlossman, “A Sin Against Childhood: Progressive Education and the Crusade to Abolish Homework, 1897-1941,” American Journal of Education , vol. 105, no. 1 (Nov., 1996), 27-66. Also see Brian P. Gill and Steven L. Schlossman, “Villain or Savior? The American Discourse on Homework, 1850-2003,” Theory into Practice , 43, 3 (Summer 2004), pp. 174-181.

[ii] Bennett, Sara, and Nancy Kalish. The Case Against Homework: How Homework Is Hurting Our Children and What We Can Do About It (New York: Crown, 2006). Buell, John. Closing the Book on Homework: Enhancing Public Education and Freeing Family Time . (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2004). Kohn, Alfie. The Homework Myth: Why Our Kids Get Too Much of a Bad Thing (Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 2006). Kralovec, Etta, and John Buell. The End of Homework: How Homework Disrupts Families, Overburdens Children, and Limits Learning (Boston: Beacon Press, 2000).

[iii] Hu, Winnie, “ New Recruit in Homework Revolt: The Principal ,” New York Times , June 15, 2011, page a1.

[iv] Data for other years are available on the NAEP Data Explorer. For Table 1, the starting point of 1984 was chosen because it is the first year all three ages were asked the homework question. The two most recent dates (2012 and 2008) were chosen to show recent changes, and the two years in the 1990s to show developments during that decade.

[v] NAEP’s sampling design lessens the probability of skewing the homework figure. Students are randomly drawn from a school population, meaning that an entire class is not tested. Teachers would have to either single out NAEP students for special homework treatment or change their established homework routine for the whole class just to shelter NAEP participants from homework. Sampling designs that draw entact classrooms for testing (such as TIMSS) would be more vulnerable to this effect. Moreover, students in middle and high school usually have several different teachers during the day, meaning that prior knowledge of a particular student’s participation in NAEP would probably be limited to one or two teachers.

[vi] NAEP Question B003801 for 9 year olds and B003901 for 13- and 17-year olds.

[vii] Met Life, Met Life Survey of the American Teacher: The Homework Experience , November 13, 2007, pp. 21-22.

[viii] Greenfeld, Karl Taro, “ My Daughter’s Homework Is Killing Me ,” The Atlantic , September 18, 2013.

Education Policy K-12 Education

Governance Studies

Brown Center on Education Policy

Sofoklis Goulas

March 14, 2024

Melissa Kay Diliberti, Stephani L. Wrabel

March 12, 2024

Sarah Reber, Gabriela Goodman

Does Homework Really Help Students Learn?

A conversation with a Wheelock researcher, a BU student, and a fourth-grade teacher

“Quality homework is engaging and relevant to kids’ lives,” says Wheelock’s Janine Bempechat. “It gives them autonomy and engages them in the community and with their families. In some subjects, like math, worksheets can be very helpful. It has to do with the value of practicing over and over.” Photo by iStock/Glenn Cook Photography

Do your homework.

If only it were that simple.

Educators have debated the merits of homework since the late 19th century. In recent years, amid concerns of some parents and teachers that children are being stressed out by too much homework, things have only gotten more fraught.

“Homework is complicated,” says developmental psychologist Janine Bempechat, a Wheelock College of Education & Human Development clinical professor. The author of the essay “ The Case for (Quality) Homework—Why It Improves Learning and How Parents Can Help ” in the winter 2019 issue of Education Next , Bempechat has studied how the debate about homework is influencing teacher preparation, parent and student beliefs about learning, and school policies.

She worries especially about socioeconomically disadvantaged students from low-performing schools who, according to research by Bempechat and others, get little or no homework.

BU Today sat down with Bempechat and Erin Bruce (Wheelock’17,’18), a new fourth-grade teacher at a suburban Boston school, and future teacher freshman Emma Ardizzone (Wheelock) to talk about what quality homework looks like, how it can help children learn, and how schools can equip teachers to design it, evaluate it, and facilitate parents’ role in it.

BU Today: Parents and educators who are against homework in elementary school say there is no research definitively linking it to academic performance for kids in the early grades. You’ve said that they’re missing the point.

Bempechat : I think teachers assign homework in elementary school as a way to help kids develop skills they’ll need when they’re older—to begin to instill a sense of responsibility and to learn planning and organizational skills. That’s what I think is the greatest value of homework—in cultivating beliefs about learning and skills associated with academic success. If we greatly reduce or eliminate homework in elementary school, we deprive kids and parents of opportunities to instill these important learning habits and skills.

We do know that beginning in late middle school, and continuing through high school, there is a strong and positive correlation between homework completion and academic success.

That’s what I think is the greatest value of homework—in cultivating beliefs about learning and skills associated with academic success.

You talk about the importance of quality homework. What is that?

Quality homework is engaging and relevant to kids’ lives. It gives them autonomy and engages them in the community and with their families. In some subjects, like math, worksheets can be very helpful. It has to do with the value of practicing over and over.

What are your concerns about homework and low-income children?

The argument that some people make—that homework “punishes the poor” because lower-income parents may not be as well-equipped as affluent parents to help their children with homework—is very troubling to me. There are no parents who don’t care about their children’s learning. Parents don’t actually have to help with homework completion in order for kids to do well. They can help in other ways—by helping children organize a study space, providing snacks, being there as a support, helping children work in groups with siblings or friends.

Isn’t the discussion about getting rid of homework happening mostly in affluent communities?

Yes, and the stories we hear of kids being stressed out from too much homework—four or five hours of homework a night—are real. That’s problematic for physical and mental health and overall well-being. But the research shows that higher-income students get a lot more homework than lower-income kids.

Teachers may not have as high expectations for lower-income children. Schools should bear responsibility for providing supports for kids to be able to get their homework done—after-school clubs, community support, peer group support. It does kids a disservice when our expectations are lower for them.

The conversation around homework is to some extent a social class and social justice issue. If we eliminate homework for all children because affluent children have too much, we’re really doing a disservice to low-income children. They need the challenge, and every student can rise to the challenge with enough supports in place.

What did you learn by studying how education schools are preparing future teachers to handle homework?

My colleague, Margarita Jimenez-Silva, at the University of California, Davis, School of Education, and I interviewed faculty members at education schools, as well as supervising teachers, to find out how students are being prepared. And it seemed that they weren’t. There didn’t seem to be any readings on the research, or conversations on what high-quality homework is and how to design it.

Erin, what kind of training did you get in handling homework?

Bruce : I had phenomenal professors at Wheelock, but homework just didn’t come up. I did lots of student teaching. I’ve been in classrooms where the teachers didn’t assign any homework, and I’ve been in rooms where they assigned hours of homework a night. But I never even considered homework as something that was my decision. I just thought it was something I’d pull out of a book and it’d be done.

I started giving homework on the first night of school this year. My first assignment was to go home and draw a picture of the room where you do your homework. I want to know if it’s at a table and if there are chairs around it and if mom’s cooking dinner while you’re doing homework.

The second night I asked them to talk to a grown-up about how are you going to be able to get your homework done during the week. The kids really enjoyed it. There’s a running joke that I’m teaching life skills.

Friday nights, I read all my kids’ responses to me on their homework from the week and it’s wonderful. They pour their hearts out. It’s like we’re having a conversation on my couch Friday night.

It matters to know that the teacher cares about you and that what you think matters to the teacher. Homework is a vehicle to connect home and school…for parents to know teachers are welcoming to them and their families.

Bempechat : I can’t imagine that most new teachers would have the intuition Erin had in designing homework the way she did.

Ardizzone : Conversations with kids about homework, feeling you’re being listened to—that’s such a big part of wanting to do homework….I grew up in Westchester County. It was a pretty demanding school district. My junior year English teacher—I loved her—she would give us feedback, have meetings with all of us. She’d say, “If you have any questions, if you have anything you want to talk about, you can talk to me, here are my office hours.” It felt like she actually cared.

Bempechat : It matters to know that the teacher cares about you and that what you think matters to the teacher. Homework is a vehicle to connect home and school…for parents to know teachers are welcoming to them and their families.

Ardizzone : But can’t it lead to parents being overbearing and too involved in their children’s lives as students?

Bempechat : There’s good help and there’s bad help. The bad help is what you’re describing—when parents hover inappropriately, when they micromanage, when they see their children confused and struggling and tell them what to do.

Good help is when parents recognize there’s a struggle going on and instead ask informative questions: “Where do you think you went wrong?” They give hints, or pointers, rather than saying, “You missed this,” or “You didn’t read that.”

Bruce : I hope something comes of this. I hope BU or Wheelock can think of some way to make this a more pressing issue. As a first-year teacher, it was not something I even thought about on the first day of school—until a kid raised his hand and said, “Do we have homework?” It would have been wonderful if I’d had a plan from day one.

Explore Related Topics:

- Share this story

Senior Contributing Editor

Sara Rimer A journalist for more than three decades, Sara Rimer worked at the Miami Herald , Washington Post and, for 26 years, the New York Times , where she was the New England bureau chief, and a national reporter covering education, aging, immigration, and other social justice issues. Her stories on the death penalty’s inequities were nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and cited in the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision outlawing the execution of people with intellectual disabilities. Her journalism honors include Columbia University’s Meyer Berger award for in-depth human interest reporting. She holds a BA degree in American Studies from the University of Michigan. Profile

She can be reached at [email protected] .

Comments & Discussion

Boston University moderates comments to facilitate an informed, substantive, civil conversation. Abusive, profane, self-promotional, misleading, incoherent or off-topic comments will be rejected. Moderators are staffed during regular business hours (EST) and can only accept comments written in English. Statistics or facts must include a citation or a link to the citation.

There are 81 comments on Does Homework Really Help Students Learn?

Insightful! The values about homework in elementary schools are well aligned with my intuition as a parent.

when i finish my work i do my homework and i sometimes forget what to do because i did not get enough sleep

same omg it does not help me it is stressful and if I have it in more than one class I hate it.

Same I think my parent wants to help me but, she doesn’t care if I get bad grades so I just try my best and my grades are great.

I think that last question about Good help from parents is not know to all parents, we do as our parents did or how we best think it can be done, so maybe coaching parents or giving them resources on how to help with homework would be very beneficial for the parent on how to help and for the teacher to have consistency and improve homework results, and of course for the child. I do see how homework helps reaffirm the knowledge obtained in the classroom, I also have the ability to see progress and it is a time I share with my kids

The answer to the headline question is a no-brainer – a more pressing problem is why there is a difference in how students from different cultures succeed. Perfect example is the student population at BU – why is there a majority population of Asian students and only about 3% black students at BU? In fact at some universities there are law suits by Asians to stop discrimination and quotas against admitting Asian students because the real truth is that as a group they are demonstrating better qualifications for admittance, while at the same time there are quotas and reduced requirements for black students to boost their portion of the student population because as a group they do more poorly in meeting admissions standards – and it is not about the Benjamins. The real problem is that in our PC society no one has the gazuntas to explore this issue as it may reveal that all people are not created equal after all. Or is it just environmental cultural differences??????

I get you have a concern about the issue but that is not even what the point of this article is about. If you have an issue please take this to the site we have and only post your opinion about the actual topic

This is not at all what the article is talking about.

This literally has nothing to do with the article brought up. You should really take your opinions somewhere else before you speak about something that doesn’t make sense.

we have the same name

so they have the same name what of it?

lol you tell her

totally agree

What does that have to do with homework, that is not what the article talks about AT ALL.

Yes, I think homework plays an important role in the development of student life. Through homework, students have to face challenges on a daily basis and they try to solve them quickly.I am an intense online tutor at 24x7homeworkhelp and I give homework to my students at that level in which they handle it easily.

More than two-thirds of students said they used alcohol and drugs, primarily marijuana, to cope with stress.

You know what’s funny? I got this assignment to write an argument for homework about homework and this article was really helpful and understandable, and I also agree with this article’s point of view.

I also got the same task as you! I was looking for some good resources and I found this! I really found this article useful and easy to understand, just like you! ^^

i think that homework is the best thing that a child can have on the school because it help them with their thinking and memory.

I am a child myself and i think homework is a terrific pass time because i can’t play video games during the week. It also helps me set goals.

Homework is not harmful ,but it will if there is too much

I feel like, from a minors point of view that we shouldn’t get homework. Not only is the homework stressful, but it takes us away from relaxing and being social. For example, me and my friends was supposed to hang at the mall last week but we had to postpone it since we all had some sort of work to do. Our minds shouldn’t be focused on finishing an assignment that in realty, doesn’t matter. I completely understand that we should have homework. I have to write a paper on the unimportance of homework so thanks.

homework isn’t that bad

Are you a student? if not then i don’t really think you know how much and how severe todays homework really is

i am a student and i do not enjoy homework because i practice my sport 4 out of the five days we have school for 4 hours and that’s not even counting the commute time or the fact i still have to shower and eat dinner when i get home. its draining!

i totally agree with you. these people are such boomers

why just why

they do make a really good point, i think that there should be a limit though. hours and hours of homework can be really stressful, and the extra work isn’t making a difference to our learning, but i do believe homework should be optional and extra credit. that would make it for students to not have the leaning stress of a assignment and if you have a low grade you you can catch up.

Studies show that homework improves student achievement in terms of improved grades, test results, and the likelihood to attend college. Research published in the High School Journal indicates that students who spent between 31 and 90 minutes each day on homework “scored about 40 points higher on the SAT-Mathematics subtest than their peers, who reported spending no time on homework each day, on average.” On both standardized tests and grades, students in classes that were assigned homework outperformed 69% of students who didn’t have homework. A majority of studies on homework’s impact – 64% in one meta-study and 72% in another – showed that take home assignments were effective at improving academic achievement. Research by the Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) concluded that increased homework led to better GPAs and higher probability of college attendance for high school boys. In fact, boys who attended college did more than three hours of additional homework per week in high school.

So how are your measuring student achievement? That’s the real question. The argument that doing homework is simply a tool for teaching responsibility isn’t enough for me. We can teach responsibility in a number of ways. Also the poor argument that parents don’t need to help with homework, and that students can do it on their own, is wishful thinking at best. It completely ignores neurodiverse students. Students in poverty aren’t magically going to find a space to do homework, a friend’s or siblings to help them do it, and snacks to eat. I feel like the author of this piece has never set foot in a classroom of students.

THIS. This article is pathetic coming from a university. So intellectually dishonest, refusing to address the havoc of capitalism and poverty plays on academic success in life. How can they in one sentence use poor kids in an argument and never once address that poor children have access to damn near 0 of the resources affluent kids have? Draw me a picture and let’s talk about feelings lmao what a joke is that gonna put food in their belly so they can have the calories to burn in order to use their brain to study? What about quiet their 7 other siblings that they share a single bedroom with for hours? Is it gonna force the single mom to magically be at home and at work at the same time to cook food while you study and be there to throw an encouraging word?

Also the “parents don’t need to be a parent and be able to guide their kid at all academically they just need to exist in the next room” is wild. Its one thing if a parent straight up is not equipped but to say kids can just figured it out is…. wow coming from an educator What’s next the teacher doesn’t need to teach cause the kid can just follow the packet and figure it out?

Well then get a tutor right? Oh wait you are poor only affluent kids can afford a tutor for their hours of homework a day were they on average have none of the worries a poor child does. Does this address that poor children are more likely to also suffer abuse and mental illness? Like mentioned what about kids that can’t learn or comprehend the forced standardized way? Just let em fail? These children regularly are not in “special education”(some of those are a joke in their own and full of neglect and abuse) programs cause most aren’t even acknowledged as having disabilities or disorders.

But yes all and all those pesky poor kids just aren’t being worked hard enough lol pretty sure poor children’s existence just in childhood is more work, stress, and responsibility alone than an affluent child’s entire life cycle. Love they never once talked about the quality of education in the classroom being so bad between the poor and affluent it can qualify as segregation, just basically blamed poor people for being lazy, good job capitalism for failing us once again!

why the hell?

you should feel bad for saying this, this article can be helpful for people who has to write a essay about it

This is more of a political rant than it is about homework

I know a teacher who has told his students their homework is to find something they are interested in, pursue it and then come share what they learn. The student responses are quite compelling. One girl taught herself German so she could talk to her grandfather. One boy did a research project on Nelson Mandela because the teacher had mentioned him in class. Another boy, a both on the autism spectrum, fixed his family’s computer. The list goes on. This is fourth grade. I think students are highly motivated to learn, when we step aside and encourage them.

The whole point of homework is to give the students a chance to use the material that they have been presented with in class. If they never have the opportunity to use that information, and discover that it is actually useful, it will be in one ear and out the other. As a science teacher, it is critical that the students are challenged to use the material they have been presented with, which gives them the opportunity to actually think about it rather than regurgitate “facts”. Well designed homework forces the student to think conceptually, as opposed to regurgitation, which is never a pretty sight