National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Plan Your Visit

- Group Visits

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Accessibility Options

- Sweet Home Café

- Museum Store

- Museum Maps

- Our Mobile App

- Search the Collection

- Exhibitions

- Initiatives

- Museum Centers

- Publications

- Digital Resource Guide

- The Searchable Museum

- Freedmen's Bureau Search Portal

- Early Childhood

- Talking About Race

- Digital Learning

- Strategic Partnerships

- Ways to Give

- Internships & Fellowships

- Today at the Museum

- Upcoming Events

- Ongoing Tours & Activities

- Past Events

- Host an Event at NMAAHC

- About the Museum

- The Building

- Meet Our Curators

- Founding Donors

- Corporate Leadership Councils

- NMAAHC Annual Reports

The Revolutionary Practice of Black Feminisms

The black feminist tradition grows not out of other movements, but out of the condition of being both black and a woman. It is a long tradition which resists easy definition and is characterized by its multi-dimensional approach to liberation.

In 1864, Sojourner Truth sold cartes-de-visite, small photographs mounted to a paper card, to support her activism. Featuring the slogan “I sell the shadow to support the substance,” Truth capitalized on the popularity of these collector’s items to support herself and fund her speaking tours. As a formerly enslaved person, claiming ownership of her image for her own profit was revolutionary. Truth reportedly said that she “used to be sold for other people’s benefit, but now she sold herself for her own.” Though expressions of black feminism can be seen in written accounts as far back as the 1830s, Sojourner Truth is the most widely known nineteenth-century black feminist foremother. Throughout her life, Truth linked the movement to abolish slavery and the movement to secure women’s rights, stating that for black women, race and gender could not be separated.

Left to right: carte-de-visite portrait of Sojourner Truth, 1864; carte-de-visite portrait of Sojourner Truth, 1863; cabinet card of Sojourner Truth, 1864

Truth’s speeches and activism represent an early expression of the black feminist tradition. Black feminism is an intellectual, artistic, philosophical, and activist practice grounded in black women’s lived experiences. Its scope is broad, making it difficult to define. In fact, the diversity of opinion among black feminists makes it more accurate to think of black feminisms in the plural. In an oral history interview from the Museum’s collection, noted activist and scholar Angela Davis speaks to this point:

I rarely talk about feminism in the singular. I talk about feminisms. And, even when I myself refused to identify with feminism, I realized that it was a certain kind of feminism . . . It was a feminism of those women who weren’t really concerned with equality for all women... Dr. Angela Davis August 5th, 2019, Oral History Interview, National Museum of African American History and Culture

Despite different visions, a few foundational principles do exist among black feminisms:

- Black women’s experience of racism, sexism, and classism are inseparable.

- Their needs and worldviews are distinct from those of black men and white women.

- There is no contradiction between the struggle against racism, sexism, and all other-isms. All must be addressed simultaneously.

Pin for the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs owned by Mary Church Terrell, 20th century.

A2017.13.1.45

“Lifting as we climb,” the slogan of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), became a well-known motto for black women’s activism in the late nineteenth century. By this time, middle class black women organized social and political reform through women’s organizations, or clubs. Having had more resources and access to education than a woman like Sojourner Truth, these women’s experiences led them to a different expression of black feminism. Their project of racial uplift focused on combating harmful stereotypes surrounding black women’s sexuality and gender identity.

Problematically, they emphasized elevating poor women, less out of a sense of good-will, than out of a recognition that black women of any class would be judged through the circumstances of those “with the fewest resources and the least opportunity.” In discussing the motto of the NACW, Mary Church Terrell, founding president of the organization, said, “Even though we wish to shun them…we cannot escape the consequences of their acts… Self-preservation would demand that we go among the lowly… to whom we are bound by ties of race and sex.”

Service Award pin for Mary Church Terrell from the NACW, 1900.

Photograph of Mary Church Terrell by Addison Scurlock, ca. 1910.

Plaque for National Association of Colored Women service award, 1949.

Gallery Modal

The black feminism of the club movement is often overlooked, but as black feminist theorist Brittney Cooper points out, clubs such as the NACW can be seen as sites of development for black feminist leadership and thought despite their elitism. The club movement ushered in a new era of intellectual, artistic, and philosophical production by black women about their own experiences.

Placard with "STOP RACISM NOW" message, late 20th century. Commissioned by the National Organization for Women.

Pauli Murray , an activist, writer, Episcopal priest, and legal scholar, played an important role in several civil, social, and legal organizations including the National Organization of Women (NOW), which she cofounded in 1966. Throughout her life, Murray had romantic relationships with women but did not consider herself a lesbian. Her biographer, Rosalind Rosenburg, suggests that had Murray been alive today, she likely would have embraced a transgender identity. Murray wrote and theorized extensively on her experiences of black womanhood asserting that, for her, gender, race, and sexuality could not be separated. This refusal to separate her identity fueled her legal work and activism. In the NOW placard above from shortly after the group’s founding, the political connections between the women’s movement and anti-racist activity can be seen. However, Murray would soon become disillusioned with NOW as she saw the organization distance itself from economic and racial justice.

Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray in her study in Arlington, Virginia, December 1976.

Members of the National Council of Negro Women including Dorothy Height and Pauli Murray (both seated), 1976.

Rev. Dr. Pauli Murray being ordained at the National Cathedral, January 1977.

As the only female student at Howard University Law School, Pauli Murray developed the term Jane Crow, the “twin evil of Jim Crow,” to describe the sexism black women faced. She would continue to develop theoretical, legal, and political frameworks for describing black women’s experiences. Her legal work connecting race-based and sex-based discrimination led to the inclusion of sex-based discrimination under the Equal Protection Clause. However, due to the Civil Rights Movement’s demands for “respectable” performances of black womanhood, Murray’s many contributions to civil rights history remain relatively unknown. Despite this neglect of her work, the legal and theoretical parallels she drew between racial discrimination and gender discrimination set the stage for feminist thinkers to follow.

One truth, especially within the context of black feminisms, is that queer black feminism has always been part of this. That queer black women, queer black folks have always been in these spaces. Dr. Treva Lindsey 2019 NMAAHC public program "Is Womanist to Feminists as Purple is to Lavender?: African American Women Writers and Scholars Discuss Feminism"

The 1970s marked an increase in explicitly black feminist organizing, due in part to tensions inflamed during the Women’s Liberation and Civil Rights Movements. By this time, queer black feminists were becoming more openly and visibly positioned within black feminist groups. They also began creating their own organizations—such as the Salsa Soul Sisters , one of the first out and explicitly multi-cultural lesbian organizations —due to tensions with straight black feminists as well as white gays and lesbians. The influential Combahee River Collective statement , co-authored by Barbara Smith, expressed a radical, queer black feminist platform still relevant to expressions of black feminism today.

Barbara Smith at a National Gay Rights March, 1993.

Marchers with "Salsa Soul Sisters" banners, 1983.

Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches by Audre Lorde, 1984.

In 1983, Alice Walker developed the term “womanist” to describe “a Black feminist or feminist of color.” Her term defined a more communal and humanist expression of feminism that acknowledged queer black women and aligned with long-standing traditions of black women’s thought and activism. Sister Outsider , by Audre Lorde, is one of many foundational womanist writings produced during this period. In her essays and speeches, Lorde discusses the connected issues of sexism, racism, classism, and heterosexism, while calling for new tactics that centered these intersections.

Black women are often thought to be at a disadvantage because of racism and sexism, but some black feminists view their position as one of possibility. They argue that in the struggle for freedom, the people most exposed to different forms of oppression understand best how to dismantle them. While late nineteenth century black feminisms were grounded in heterosexual black women’s bodies, by the end of the twentieth and into the twenty-first century, radical black feminisms came to center queer and trans black women, girls, and gender nonconforming people.

Untitled , 2015. Photograph by Sheila Pree Bright taken at a Black Lives Matter rally in Atlanta, Georgia.

Marchers at the Women’s March, January 21, 2017.

Untitled , August 25, 2015.

Outside black feminist circles, black feminisms are often described as an outgrowth of other freedom struggles. While black women’s experiences working within political and social movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries certainly informed articulations of black feminism, black feminisms have never been derivative, nor do they fit cleanly into the “waves” of feminist history . For black women and other women of color, race and gender are inseparable, and black feminists resist all movements that ignore this reality. From women’s suffrage to the Women’s March of 2017, they have been unwilling to compromise on the assertion that a feminism which does not incorporate different experiences of womanhood cannot achieve full liberation. Since before Sojourner Truth sold her “shadow,” women in the black feminist tradition have developed theoretical frameworks and practices born of their experiences, to get, as black feminist scholar Dr. Treva Lindsey put it, “freer and freer and freer.”

Browse Objects Relating to Feminism in the NMAAHC Collection

Written by Max Peterson, Fall 2019 Intern Published on March 4, 2019

Is Womanist to Feminist as Purple is to Lavender?: African American Women Writers and Scholars Discuss Feminism program - https://www.ustream.tv/recorded/124469629

Guy-Sheftall, Beverley, ed. Words of Fire: An Anthology of African American Feminist Thought. New York, NY: The New Press, 1995.

Cooper, Brittney C. Beyond Respectability: The Intellectual Thought of Race Women. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2017.

Springer, Kimberly. Living for the Revolution: Black Feminist Organizations, 1968-1980. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005.

Lorde, Audre. Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. Freedom, CA: Crossing Press, 1984.

Walker, Alice. In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens: Womanist Prose . San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1983.

Subtitle here for the credits modal.

Black feminism and intersectionality

“Although we are in essential agreement with Marx’s theory as it applied to the very specific economic relationships he analyzed, we know that his analysis must be extended further in order for us to understand our specific economic situation as Black women.” —the Combahee River Collective Statement, 1977 1

“The concept of the simultaneity of oppression is still the crux of a Black feminist understanding of political reality and, I believe, one of the most significant ideological contributions of Black feminist thought.” —Black feminist and scholar Barbara Smith, 1983 2

Black legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality” in her insightful 1989 essay, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” 3 The concept of intersectionality is not an abstract notion but a description of the way multiple oppressions are experienced. Indeed, Crenshaw uses the following analogy, referring to a traffic intersection, or crossroad, to concretize the concept:

Consider an analogy to traffic in an intersection, coming and going in all four directions. Discrimination, like traffic through an intersection, may flow in one direction, and it may flow in another. If an accident happens in an intersection, it can be caused by cars traveling from any number of directions and, sometimes, from all of them. Similarly, if a Black woman is harmed because she is in an intersection, her injury could result from sex discrimination or race discrimination. . . . But it is not always easy to reconstruct an accident: Sometimes the skid marks and the injuries simply indicate that they occurred simultaneously, frustrating efforts to determine which driver caused the harm. 4

Crenshaw argues that Black women are discriminated against in ways that often do not fit neatly within the legal categories of either “racism” or “ sexism”—but as a combination of both racism and sexism. Yet the legal system has generally defined sexism as based upon an unspoken reference to the injustices confronted by all (including white) women, while defining racism to refer to those faced by all (including male) Blacks and other people of color. This framework frequently renders Black women legally “invisible” and without legal recourse.

Crenshaw describes several employment discrimination-based lawsuits to illustrate how Black women’s complaints often fall between the cracks precisely because they are discriminated against both as women and as Blacks. The ruling in one such case, DeGraffenreid v. General Motors , filed by five Black women in 1976, demonstrates this point vividly.

The General Motors Corporation had never hired a Black woman for its workforce before 1964—the year the Civil Rights Act passed through Congress. All of the Black women hired after 1970 lost their jobs fairly quickly, however, in mass layoffs during the 1973–75 recession. Such a sweeping loss of jobs among Black women led the plaintiffs to argue that seniority-based layoffs, guided by the principle “last hired-first fired,” discriminated against Black women workers at General Motors, extending past discriminatory practices by the company.

Yet the court refused to allow the plaintiffs to combine sex-based and race-based discrimination into a single category of discrimination:

The plaintiffs allege that they are suing on behalf of black women, and that therefore this lawsuit attempts to combine two causes of action into a new special sub-category, namely, a combination of racial and sex-based discrimination…. The plaintiffs are clearly entitled to a remedy if they have been discriminated against. However, they should not be allowed to combine statutory remedies to create a new “super-remedy” which would give them relief beyond what the drafters of the relevant statutes intended. Thus, this lawsuit must be examined to see if it states a cause of action for race discrimination, sex discrimination, or alternatively either, but not a combination of both. 5

In its decision, the court soundly rejected the creation of “a new classification of ‘black women’ who would have greater standing than, for example, a black male. The prospect of the creation of new classes of protected minorities, governed only by the mathematical principles of permutation and combination, clearly raises the prospect of opening the hackneyed Pandora’s box.” 6

Crenshaw observes of this ruling that “providing legal relief only when Black women show that their claims are based on race or on sex is analogous to calling an ambulance for the victim only after the driver responsible for the injuries is identified.” 7

“Ain’t we women?” After Crenshaw introduced the term intersectionality in 1989, it was widely adopted because it managed to encompass in a single word the simultaneous experience of the multiple oppressions faced by Black women. But the concept was not a new one. Since the times of slavery, Black women have eloquently described the multiple oppressions of race, class, and gender—referring to this concept as “interlocking oppressions,” “simultaneous oppressions,” “double jeopardy,” “triple jeopardy” or any number of descriptive terms. 8

Like most other Black feminists, Crenshaw emphasizes the importance of Sojourner Truth’s famous “Ain’t I a Woman?” speech delivered to the 1851 Women’s Convention in Akron, Ohio:

That man over there says that women need to be helped into carriages and lifted over ditches, and to have the best place everywhere. Nobody ever helps me into carriages, or over mud-puddles, or gives me any best place! And ain’t I a woman? Look at me! Look at my arm! I could have ploughed and planted, and gathered into barns, and no man could head me! And ain’t I a woman? I could work as much and eat as much as a man—when I could get it—and bear the lash as well! And ain’t I a woman? I have borne thirteen children, and seen them most all sold off to slavery, and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me! And ain’t I a woman? 9

Truth’s words vividly contrast the character of oppression faced by white and Black women. While white middle-class women have traditionally been treated as delicate and overly emotional—destined to subordinate themselves to white men—Black women have been denigrated and subject to the racist abuse that is a foundational element of US society. Yet, as Crenshaw notes, “When Sojourner Truth rose to speak, many white women urged that she be silenced, fearing that she would divert attention from women’s suffrage to emancipation,” invoking a clear illustration of the degree of racism within the suffrage movement. 10

Crenshaw draws a parallel between Truth’s experience with the white suffrage movement and Black women’s experience with modern feminism, arguing, “When feminist theory and politics that claim to reflect women’s experiences and women’s aspirations do not include or speak to Black women, Black women must ask, “Ain’t we women?”

Intersectionality as a synthesis of oppressions Thus, Crenshaw’s political aims reach further than addressing flaws in the legal system. She argues that Black women are frequently absent from analyses of either gender oppression or racism, since the former focuses primarily on the experiences of white women and the latter on Black men. She seeks to challenge both feminist and antiracist theory and practice that neglect to “accurately reflect the interaction of race and gender,” arguing that “because the intersectional experience is greater than the sum of racism and sexism, any analysis that does not take intersectionality into account cannot sufficiently address the particular manner in which Black women are subordinated.” 11

Crenshaw argues that a key aspect of intersectionality lies in its recognition that multiple oppressions are not each suffered separately but rather as a single, synthesized experience. This has enormous significance at the very practical level of movement building.

In Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness and the Politics of Empowerment , published in 1990, Black feminist Patricia Hill Collins extends and updates the social contradictions raised by Sojourner Truth, while crediting collective struggles waged historically with establishing a “collective wisdom” among Black women:

If women are allegedly passive and fragile, then why are Black women treated as “mules” and assigned heavy cleaning chores? If good mothers are supposed to stay at home with their children, then why are US Black women on public assistance forced to find jobs and leave their children in day care? If women’s highest calling is to become mothers, then why are Black teen mothers pressured to use Norplant and Depo Provera? In the absence of a viable Black feminism that investigates how intersecting oppressions of race, gender, and class foster these contradictions, the angle of vision created by being deemed devalued workers and failed mothers could easily be turned inward, leading to internalized oppression. But the legacy of struggle among US Black women suggests that a collectively shared Black women’s oppositional knowledge has long existed. This collective wisdom in turn has spurred US Black women to generate a more specialized knowledge, namely, Black feminist thought as critical social theory. 12

Like Crenshaw, Collins uses the concept of intersectionality to analyze how “oppressions [such as ‘race and gender’ or ‘sexuality and nation’] work together in producing injustice.” But Collins adds the concept “matrix of dominations” to this formulation: “In contrast, the matrix of dominations refers to how these intersecting oppressions are actually organized. Regardless of the particular intersections involved, structural, disciplinary, hegemonic, and interpersonal domains of power reappear across quite different forms of oppression.” 13

Elsewhere, Collins acknowledges the crucial component of social class among Black women in shaping political perceptions. In “The Contours of an Afrocentric Feminist Epistemology,” she argues that “[w]hile a Black woman’s standpoint and its accompanying epistemology stem from Black women’s consciousness of race and gender oppression, they are not simply the result of combining Afrocentric and female values— standpoints are rooted in real material conditions structured by social class. ” 14 [Emphasis added.]

Fighting sexism in a profoundly racist society Because of the historic role of slavery and racial segregation in the United States, the development of a unified women’s movement requires recognizing the manifold implications of this continuing racial divide. While all women are oppressed as women, no movement can claim to speak for all women unless it speaks for women who also face the consequences of racism—which place women of color disproportionately in the ranks of the working class and the poor. Race and class therefore must be central to the project of women’s liberation if it is to be meaningful to those women who are most oppressed by the system.

Indeed, one of the key weaknesses of the predominantly white US feminist movement has been its lack of attention to racism, with enormous repercussions. Failure to confront racism ends up reproducing the racist status quo.

The widely accepted narrative of the modern feminist movement is that it initially involved white women beginning in the late 1960s and early 1970s, who were later joined by women of color following in their footsteps. But this narrative is factually incorrect.

Decades before the rise of the modern women’s liberation movement, Black women were organizing against their systematic rape at the hands of white racist men. Women civil rights activists, including Rosa Parks, were part of a vocal grassroots movement to defend Black women subject to racist sexual assaults—in an intersection of oppression unique to Black women historically in the United States.

Danielle L. McGuire, author of At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance—A New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power 15 argues that

throughout the twentieth century…Black women regularly denounced their sexual misuse. By deploying their voices as weapons in the wars against white supremacy, whether in the church, the courtroom, or in congressional hearings, African American women loudly resisted what Martin Luther King, Jr., called the “thingification” of their humanity. Decades before radical feminists in the women’s movement urged rape survivors to “speak out,” African American women’s public protests galvanized local, national, and even international outrage and sparked larger campaigns for racial justice and human dignity. 16

The invention of the Black “matriarchy” In the 1960s, the contrast between white middle-class and Black women’s oppression could not have been more obvious. The same “experts” who prescribed a life of happy homemaking for white suburban women, as documented in Betty Friedan’s enormously popular The Feminine Mystique , reprimanded Black women for their failure to conform to this model. 17 Because Black mothers have traditionally worked outside the home in much larger numbers than their white counterparts, they were blamed for a range of social ills on the basis of their relative economic independence.

Socialist-feminist Stephanie Coontz describes “Freudians and social scientists” who “insisted that Black men had been doubly emasculated—first by slavery and later by the economic independence of their women.” Many in the African-American media also accepted this analysis. A 1960 Ebony magazine article stated plainly that the traditional independence of the Black woman meant that she was “more in conflict with her innate biological role than the white woman.” 18

This theme emerged full throttle in 1965, when the US Department of Labor issued a report entitled, “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action.” The report, authored by future Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan, describes a “Black matriarchy” at the center of a “tangle of pathology” afflicting Black families, leading to a cycle of poverty. “A fundamental fact of Negro American family life is the often reversed roles of husband and wife,” in which Black women consistently earn more than their men, argues Moynihan.

The report states, “In essence, the Negro community has been forced into a matriarchal structure which, because it is so out of line with the rest of the American society, seriously retards the progress of the group as a whole.” The report explains why this is the case:

There is, presumably, no special reason why a society in which males are dominant in family relationships is to be preferred to a matriarchal arrangement. However, it is clearly a disadvantage for a minority group to be operating on one principle, while the great majority of the population, and the one with the most advantages to begin with, is operating on another. This is the present situation of the Negro. Ours is a society which presumes male leadership in private and public affairs. The arrangements of society facilitate such leadership and reward it. A subculture, such as that of the Negro American, in which this is not the pattern, is placed at a distinct disadvantage. 19

This example demonstrates why gender discrimination cannot be effectively understood without factoring in the role of racism. And Black feminists since that time have made a priority of examining the interlocking relationship between gender, race, and class that many white feminists tended to ignore at the time. In so doing, they demonstrated that women of color are not merely “doubly oppressed” by both sexism and racism. Black women’s experience of sexism is shaped equally by racism and class inequality and is therefore different in certain respects from the experience of white, middle-class women.

“Two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal” The 1950s and1960s was also a period of intensive racial polarization in the United States, as the massive Civil Rights Movement struggled to end both Jim Crow segregation throughout the South and de facto racial segregation in the North. Interracial marriage was still banned in sixteen states in 1967 when the Supreme Court finally ruled such bans unconstitutional in the Loving v. Virginia decision.

Urban rebellions swept the country in the mid- to late-sixties, touched off by police brutality and other forms of racial discrimination in poverty-stricken Black ghettoes. In 1967, the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, also known as the Kerner Commission, was established to investigate the root causes of urban rebellions. In 1968, the Commission issued a report that included scathing indictment of racism and segregation in US society. The report concludes:

Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white—separate and unequal.… Segregation and poverty have created in the racial ghetto a destructive environment totally unknown to most white Americans. What white Americans have never fully understood but what the Negro can never forget—is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it. 20

The Kerner Commission emphasized that much of the problem was rooted in “[p]ervasive discrimination and segregation in employment, education and housing, which have resulted in the continuing exclusion of great numbers of Negroes from the benefits of economic progress.” The Commission concluded that the degree of housing segregation was such that “to create an unsegregated population distribution, an average of over 86 percent of all Negroes would have to change their place of residence within the city.” 21

In response to the extreme degree of racism and sexism they faced in the 1960s, Black women and other women of color began organizing against their oppression, forming a multitude of organizations. In 1968, for example, Black women from the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) formed the Third World Women’s Alliance. In 1973, a group of notable Black feminists, including Florynce Kennedy, Alice Walker, and Barbara Smith, formed the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO). In 1974, Barbara Smith joined with a group of other Black lesbian feminists to found the Boston-based Combahee River Collective as a self-consciously radical alternative to the NBFO. The Combahee River Collective was named to commemorate the successful Underground Railroad Combahee River Raid of 1863, planned and led by Harriet Tubman, which freed 750 slaves.

The Combahee River Collective’s defining statement, issued in 1977, described its vision for Black feminism as opposing all forms of oppression—including sexuality, gender identity, class, disability, and age oppression—later embedded in the concept of intersectionality.

The most general statement of our politics at the present time would be that we are actively committed to struggling against racial, sexual, heterosexual, and class oppression, and see as our particular task the development of integrated analysis and practice based upon the fact that the major systems of oppression are interlocking. The synthesis of these oppressions creates the conditions of our lives. As Black women we see Black feminism as the logical political movement to combat the manifold and simultaneous oppressions that all women of color face. 22

They added, “We know that there is such a thing as racial-sexual oppression which is neither solely racial nor solely sexual, e.g., the history of rape of Black women by white men as a weapon of political repression.” 23

The consequences of ignoring class and racial differences between women As noted above, Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique , published in 1963, gave voice to the anguish of white middle-class homemakers who were trapped in their suburban homes, doomed to lives revolving around fulfilling their families’ every need. The book immediately struck a chord with millions of women who desperately sought to escape the stultifying world of household drudgery.

Friedan’s book, however, ignored the importance of the very real class and racial differences that exist between women. She made a conscious decision to target this particular audience of white middle-class women. As Coontz notes, “[T]he content of The Feminine Mystique and the marketing strategy that Friedan and her publishers devised for it ignored Black women’s positive examples of Friedan’s argument.” Friedan surely knew better. She had traveled in left-wing labor circles during the 1930s and 1940s but decided in the mid-1950s (at the height of the anticommunist witch hunts of the McCarthy era) to reinvent herself as an apolitical suburban wife. 24

Few Black women or working-class women of any race would have been able to afford Friedan’s proposal that women hire domestic workers to perform their daily household chores while they were at work. Thus, “Black women who did read the book seldom responded as enthusiastically as did her white readers.” 25

Friedan praises those stay-at-home moms who had shown the courage to break from their traditional roles to seek well-paying careers, writing sympathetically that these women “had problems of course, tough ones—juggling their pregnancies, finding nurses and housekeepers, having to give up good assignments when their husbands were transferred.” 31 Yet she doesn’t deem it worthy to comment on the lives of the nursemaids and the housekeepers these career women hire, who also work all day but then return home to face housework and child care responsibilities of their own.

Soon after The Feminine Mystique was published, left-wing civil rights activist and women’s historian Gerda Lerner wrote to Friedan, praising the book but also expressing “one reservation:” Friedan had addressed the book “solely to the problems of middle class, college-educated women.” Lerner notes that “working women, especially Negro women, labor not only under the disadvantages imposed by the feminine mystique, but under the more pressing disadvantages of economic discrimination.” 26

It is also worth noting that Friedan introduces a profoundly anti-gay theme in The Feminine Mystique that would reverberate in her organizing efforts into the 1970s. She argues that “the homosexuality that is spreading like a murky smog over the American scene” has its roots in the feminine mystique, which can produce “the kind of mother-son devotion that can produce latent or overt homosexuality…. The boy smothered by such parasitical mother-love is kept from growing up, not only sexually, but in all ways.” 27

Reproducing the myth of the Black rapist But racism was not limited to the more conservative wing of the women’s movement. Susan Brownmiller, author of Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape , published in 1975, describes the root of women’s oppression in the crudest of biological terms, based on men’s physical ability to rape: “When men discovered that they could rape, they proceeded to do it…. Man’s discovery that his genitalia could serve as a weapon to generate fear must rank as one of the most important discoveries of prehistoric times, along with the use of fire and the first crude stone axe. From prehistoric times to the present, I believe, rape has played a critical function.” On this basis, Brownmiller concludes that men use rape to enforce their power over women: “[I]t is nothing more and nothing less than a conscious process by which all men keep all women in a state of fear.” 28

This theoretical framework, based purely on the supposed biological differences between men and women, allowed Brownmiller to justify reactionary assumptions in the name of combating women’s oppression. She reaches openly racist conclusions in her account of the 1955 lynching of Emmett Till. Fourteen-year-old Till, visiting family in Jim Crow Mississippi that summer, committed the “crime” of whistling at a married white woman named Carolyn Bryant, in a teenage prank. Till was tortured and shot before his young body was dumped in the Tallahatchie River.

Despite Till’s lynching, Brownmiller describes Till and his killer as sharing power over a “white woman,” using stereotypes that Black activist and scholar Angela Davis called “the resuscitation of the old racist myth of the Black rapist.” 29

Brownmiller’s own words illustrate Davis’s insight:

Rarely has one single case exposed so clearly as Till’s the underlying group male antagonisms over access to women, for what began in Bryant’s store should not be misconstrued as an innocent flirtation…. Emmett Till was going to show his black buddies that he, and by inference, they could get a white woman and Carolyn Bryant was the nearest convenient object. In concrete terms, the accessibility of all white women was on review. 30

Brownmiller also wrote,

And what of the wolf whistle, Till’s ‘gesture of adolescent bravado?’… The whistle was no small tweet of hubba-hubba or melodious approval for a well turned ankle…. It was a deliberate insult just short of physical assault, a last reminder to Carolyn Bryant that this black boy, Till, had in mind to possess her. 31

The acclaimed novelist, poet, and activist Alice Walker responded in the New York Times Book Review in 1975, “Emmett Till was not a rapist. He was not even a man. He was a child who did not understand that whistling at a white woman could cost him his life.” 32 Davis described the contradictions inherent in Brownmiller’s analysis of rape: “In choosing to take sides with white women, regardless of the circumstances, Brownmiller herself capitulates to racism. Her failure to alert white women about the urgency of combining a fierce challenge to racism with the necessary battle against sexism is an important plus for the forces of racism today.” 33

In 1976, Time magazine named Susan Brownmiller one of its “women of the year,” praising her book as “the most rigorous and provocative piece of scholarship that has yet emerged from the feminist movement.” 34 The objections to Brownmiller’s overtly racist standpoint from accomplished Black women such as Davis and Walker went largely unnoticed by the political mainstream.

Fighting sexism and racism in the 1970s It must be acknowledged that many women of color who identified as feminists in the 1970s and 1980s were strongly critical of mainstream feminism’s refusal to challenge racism and other forms of oppression. Barbara Smith, for example, argued for the inclusion of all the oppressed in a 1979 speech, in a clear challenge to white, middle-class, heterosexual feminists:

The reason racism is a feminist issue is easily explained by the inherent definition of feminism. Feminism is the political theory and practice to free all women: women of color, working-class women, poor women, physically challenged women, lesbians, old women, as well as white economically privileged heterosexual women. Anything less than this is not feminism, but merely female self-aggrandizement . 35

But during the 1960s and 1970s, many Black women and other women of color also felt sidelined and alienated by the lack of attention to women’s liberation inside nationalist and other antiracist movements. The Combahee River Collective, for example, was made up of women who were veterans of the Black Panther Party and other antiracist organizations. In this political context, Black feminists established a tradition that rejects prioritizing women’s oppression over racism, and vice versa. This tradition assumes the connection between racism and poverty in capitalist society, thereby rejecting middle-class strategies for women’s liberation that disregard the centrality of class in poor and working-class women’s lives.

Black feminists such as Angela Davis contested the theory and practice of white feminists who failed to address the centrality of racism. Davis’s groundbreaking book, Women, Race and Class , for example, examines the history of Black women in the United States from a Marxist perspective beginning with the system of slavery and continuing through to modern capitalism. Her book also examines the ways in which the issues of reproductive rights and rape, in particular, represent profoundly different experiences for Black and white women because of racism. Each of these is examined below.

• Reproductive rights and racist sterilization abuse Mainstream feminists of the 1960s and 1970s regarded the issue of reproductive rights as exclusively the winning of legal abortion, without acknowledging the racist policies that have historically prevented women of color from bearing and raising as many children as they wanted.

Davis argues that the history of the birth control movement and its racist sterilization programs necessarily make the issue of reproductive rights far more complicated for Black women and other women of color, who have historically been the targets of this abuse. Davis traces the path of twentieth-century birth-control pioneer Margaret Sanger from her early days as a socialist to her conversion to the eugenics movement, an openly racist approach to population control based on the slogan, “[More] children from the fit, less from the unfit.”

Those “unfit” to bear children, according to the eugenicists, included the mentally and physically disabled, prisoners, and the non-white poor. As Davis noted, “By 1932, the Eugenics Society could boast that at least twenty-six states had passed compulsory sterilization laws, and that thousands of ‘unfit’ persons had been surgically prevented from reproducing.”

In launching the “Negro Project” in 1939, Sanger’s American Birth Control League argued, “[T]he mass of Negroes, particularly in the South, still breed carelessly and disastrously.” In a personal letter, Sanger confided, “We do not want word to get out that we want to exterminate the Negro population and the minister is the man who can straighten out that idea if it ever occurs to their more rebellious members.” 36

Racist population-control policies left large numbers of Black women, Latinas, and Native American women sterilized against their will or without their knowledge. In 1974, an Alabama court found that between 100,000 and 150,000 poor Black teenagers were sterilized each year in Alabama.

The 1960s and 1970s witnessed an epidemic of sterilization abuse and other forms of coercion aimed at Black, Native American, and Latina women—alongside a sharp rise in struggles against this mistreatment. A 1970s study showed that 25 percent of Native American women had been sterilized, and that Black and Latina married women had been sterilized in much greater proportions than married women in the population at large. By 1968, one-third of women of childbearing age in Puerto Rico—still a US colony—had been permanently sterilized. 37

Yet mainstream white feminists not only ignored these struggles but also added to the problem. Many embraced the goals of population control with all its racist implications as an ostensibly “liberal” cause.

In 1972, for example, a time when Native Americans and other women of color were struggling against coercive adoption policies that targeted their communities, Ms. Magazine asked its predominantly white and middle-class readership, “‘What do you do if you’re a conscientious citizen, concerned about the population explosion and ecological problems, love children, want to see what one of your own would look like, and want more than one?’ Ms. offered as a solution: ‘Have One, Adopt One.’” 38 The children on offer for adoption were overwhelmingly Native American, Black, Latino, and Asian.

To be sure, the legalization of abortion in the US Supreme Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade decision was of paramount importance to all women and the direct result of grassroots struggle. Because of both the economic and social consequences of racism, the lives of Black women, Latinas, and other women of color were most at risk when abortion was illegal. Before abortion was made legal in New York City in 1970, for example, Black women made up 50 percent of all women who died after an illegal abortion, while Puerto Rican women were 44 percent. 39

The legalization of abortion in 1973 is usually regarded as the most important success of the modern women’s movement. That victory however was accompanied at the end of that decade by the far less heralded but equally important victories against sterilization abuse, the result of grassroots struggles waged primarily by women of color. In 1978, the federal government conceded to demands by Native American, Black, and Latina activists by finally establishing regulations for sterilization. These included required waiting periods and authorization forms in the same language spoken by the woman agreeing to be sterilized. 40

Davis notes that women of color “were far more familiar than their white sisters with the murderously clumsy scalpels of inept abortionists seeking profit in illegality,” 41 yet were virtually absent from abortion rights campaigns. She concludes, “[T]he abortion rights activists of the early 1970s should have examined the history of their movement. Had they done so, they might have understood why so many of their Black sisters adopted a posture of suspicion toward their cause.” 42

• The racial component of rape Rape is one of the most damaging manifestations of women’s oppression the world over. But rape also has had a toxic racial component in the United States since the time of slavery, as a key weapon in maintaining the system of white supremacy. Davis argues that rape is “an essential dimension of the social relations between slave master and slave,” involving the routine rape of Black slave women by their white masters. 43

She describes rape as “a weapon of domination, a weapon of repression, whose covert goal was to extinguish slave women’s will to resist and, in the process, to demoralize their men.” 44 The institutionalized rape of Black women survived the abolition of slavery and took on its modern form: “Group rape, perpetuated by the Ku Klux Klan and other terrorist organizations of the post–Civil War period, became an uncamouflaged political weapon in the drive to thwart the movement for Black equality.” 45

Black Marxist-feminist Gloria Joseph makes the following insightful observation of the shared experience of racism among Black women and men: “The slave experience for Blacks in the United States made an ironic contribution to male-female equality. Laboring in the fields or in the homes, men and women were equally dehumanized and brutalized.” In modern society, she concludes, “The rape of Black women and the lynching and castration of Black men are equally heinous in their nature.” 46

The caricature of the virtuous white Southern belle under constant prey by Black male rapists had its opposite in the promiscuous Black woman seeking the sexual attention of white men. As Davis argues, “The fictional image of the Black man as rapist has always strengthened its inseparable companion: the image of the Black woman as chronically promiscuous…. Viewed as ‘loose women’ and whores, Black women’s cries of rape would necessarily lack legitimacy.” 47 As Lerner likewise describes, “The myth of the Black rapist of white women is the twin of the myth of the bad Black woman—both designed to apologize for and facilitate the continued exploitation of Black men and women.” 48

Brownmiller was not alone in failing to challenge racist assumptions about rape, with the consequence of reproducing them. Davis strongly criticizes 1970s-era white feminists for neglecting to integrate an analysis of racism with the theory and practice of combating rape: “During the contemporary anti-rape movement, few feminist theorists seriously analyzed the special circumstances surrounding the Black woman as rape victim. The historical knot binding Black women—systematically abused and violated by white men—to Black men—maimed and murdered because of the racist manipulation of the rape charge—has just begun to be acknowledged to any significant extent.” 49

Left-wing Black feminism as a politics of inclusion This article has attempted to show how Black feminists since the time of slavery have developed a distinct political tradition based upon a systematic analysis of the interlocking oppressions of race, gender, and class. Since the 1970s, Black feminists and other feminists of color in the United States have built upon this analysis and developed an approach that provides a strategy for combating all forms of oppression within a common struggle.

Black feminists—along with Latinas and other women of color—of the 1960s era, who were critical of both the predominantly white feminist movement for its racism and of nationalist and other antiracist movements for their sexism, often formed separate organizations that could address the particular oppressions they faced. And when they rightfully asserted the racial and class differences between women, they did so because these differences were largely ignored and neglected by much of the women’s movement at that time, thereby rendering Black women and other women of color invisible in theory and in practice.

The end goal was not, however, permanent racial separation for most left-wing Black and other feminists of color, as it has come to be understood since. Barbara Smith conceived of an inclusive approach to combat multiple oppressions, beginning with coalition building around particular struggles. As she observed in 1983, “The most progressive sectors of the women’s movement, including radical white women, have taken [issues of racism], and many more, quite seriously.” 50 Asian American feminist Merle Woo argues explicitly: “Today…I feel even more deeply hurt when I realize how many people, how so many people, because of racism and sexism, fail to see what power we sacrifice by not joining hands.” But, she adds, “not all white women are racist, and not all Asian-American men are sexist. And there are visible changes. Real, tangible, positive changes.” 51

The aim of intersectionality within the Black feminist tradition has been toward building a stronger movement for women’s liberation that represents the interests of all women. Barbara Smith described her own vision of feminism in 1984: “I have often wished I could spread the word that a movement committed to fighting sexual, racial, economic and heterosexist oppression, not to mention one which opposes imperialism, anti-Semitism, the oppressions visited upon the physically disabled, the old and the young, at the same time that it challenges militarism and imminent nuclear destruction is the very opposite of narrow.” 52

This approach to fighting oppression does not merely complement but also strengthens Marxist theory and practice—which seeks to unite not only all those who are exploited but also all those who are oppressed by capitalism into a single movement that fights for the liberation of all humanity. The Black feminist approach described above enhances Lenin’s famous phrase from What is to be Done? : “Working-class consciousness cannot be genuine political consciousness unless the workers are trained to respond to all cases of tyranny, oppression, violence, and abuse, no matter what class is affected—unless they are trained, moreover, to respond from a Social-Democratic point of view and no other.” 53

The Combahee River Collective, which was perhaps the most self-consciously left-wing organization of Black feminists in the 1970s, acknowledged its adherence to socialism and anti-imperialism, while rightfully also arguing for greater attention to oppression:

We realize that the liberation of all oppressed peoples necessitates the destruction of the political-economic systems of capitalism and imperialism as well as patriarchy. We are socialists because we believe that work must be organized for the collective benefit of those who do the work and create the products, and not for the profit of the bosses. Material resources must be equally distributed among those who create these resources. We are not convinced, however, that a socialist revolution that is not also a feminist and anti-racist revolution will guarantee our liberation…. Although we are in essential agreement with Marx’s theory as it applied to the very specific economic relationships he analyzed, we know that his analysis must be extended further in order for us to understand our specific economic situation as Black women. 54

At the same time, intersectionality cannot replace Marxism—and Black feminists have never attempted to do so. Intersectionality is a concept for understanding oppression, not exploitation. Even the commonly used term “classism” describes an aspect of class oppression—snobbery and elitism—not exploitation. Most Black feminists acknowledge the systemic roots of racism and sexism but place far less emphasis than Marxists on the connection between the system of exploitation and oppression.

Marxism is necessary because it provides a framework for understanding the relationship between oppression and exploitation (i.e., oppression as a byproduct of the system of class exploitation), and also identifies the strategy for creating the material and social conditions that will make it possible to end both oppression and exploitation. Marxism’s critics have disparaged this framework as an aspect of Marx’s “economic reductionism.”

But, as Marxist-feminist Martha Gimenez responds, “To argue, then, that class is fundamental is not to ‘reduce’ gender or racial oppression to class, but to acknowledge that the underlying basic and ‘nameless’ power at the root of what happens in social interactions grounded in ‘intersectionality’ is class power.” 55 The working class holds the potential to lead a struggle in the interests of all those who suffer injustice and oppression. This is because both exploitation and oppression are rooted in capitalism. Exploitation is the method by which the ruling class robs workers of surplus value; the various forms of oppression play a primary role in maintaining the rule of a tiny minority over the vast majority. In each case, the enemy is one and the same.

The class struggle helps to educate workers—sometimes very rapidly—challenging reactionary ideas and prejudices that keep workers divided. When workers go on strike, confronting capital and its agents of repression (the police), the class nature of society becomes suddenly clarified. Racist, sexist, or homophobic ideas cultivated over a lifetime can disappear within a matter of days in a mass strike wave. The sight of hundreds of police lined up to protect the boss’s property or to usher in a bunch of scabs speaks volumes about the class nature of the state within capitalism.

The process of struggle also exposes another truth hidden beneath layers of ruling-class ideology: as the producers of the goods and services that keep capitalism running, workers have the ability to shut down the system through a mass strike. And workers not only have the power to shut down the system, but also to replace it with a socialist society, based upon collective ownership of the means of production. Although other groups in society suffer oppression, only the working class possesses this objective power.

These are the basic reasons why Marx argues that capitalism created its own gravediggers in the working class. But when Marx defines the working class as the agent for revolutionary change, he is describing its historical potential, rather than a foregone conclusion. This is the key to understanding Lenin’s words, cited above. The whole Leninist conception of the vanguard party rests on understanding that a battle of ideas must be fought inside the working class movement. A section of workers won to a socialist alternative and organized into a revolutionary party, can win other workers away from ruling-class ideologies and provide an alternative worldview. For Lenin, the notion of political consciousness entails workers’ willingness to champion the interests of all the oppressed in society, as an integral part of the struggle for socialism.

As an additive to Marxist theory, intersectionality leads the way toward a much higher level of understanding of the character of oppression than that developed by classical Marxists, enabling the further development of the ways in which solidarity can be built between all those who suffer oppression and exploitation under capitalism to forge a unified movement.

- The Combahee River Collective, April 1977. Quoted, for example, in Beverly Guy-Sheftall, ed., Words of Fire: An Anthology of African-American Feminist Thought (New York: The New Press, 1995), 235. The statement is available online at www. circuitous.org/scraps/combahee.html .

- Barbara Smith, ed., Home Girls: A Black Feminist Anthology (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2000), xxxiv.

- Kimberlé Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory, and Antiracist Politics,” University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989, 139–67.

- Ibid., 149.

- Crenshaw, “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex,” 142.

- Ibid., 143.

- See, for example, Guy-Sheftall, Words of Fire .

- Sojourner Truth, “Ain’t I a Woman?” Women’s Convention, Akron, Ohio, May 28-29, 1851. Quoted in Crenshaw, 153.

- Ibid., 140.

- Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment , second edition (New York: Routledge, 2001), 11–12.

- Quoted in Guy-Sheftall, Words of Fire , 345.

- Danielle L. McGuire, At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance—A New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power (New York: Random House, 2010).

- Ibid., xix–xx.

- Betty Friedan, The Feminine Mystique (New York: W.W. Norton, 1964).

- Stephanie Coontz, A Strange Stirring: The Feminine Mystique and American Women at the Dawn of the 1960s (Basic Books, 2011), 124.

- Office of Planning and Research, US Department of Labor, “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action, (March 1965).” Available online at www.dol.gov/asp/programs/history/webid-m... .

- Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (New York: Bantam Books, 1968), 1–29. Available online at www.eisenhowerfoundation.org/docs/kerner... .

- Combahee River Collective Statement.

- Coontz, A Strange Stirring , 140.

- Ibid., 126.

- Ibid., 101.

- Friedan, The Feminine Mystique , 263–64.

- Susan Brownmiller, Against Our Will: Men, Women and Rape (New York: Ballantine, 1993), 14–15.

- Angela Y. Davis, Women, Race, and Class (New York: Vintage, 1983), 178.

- Brownmiller, Against Our Will , 272.

- Ibid., 247.

- Alice Walker quoted in D.H. Melhem, Gwendolyn Brooks: Poetry and the Heroic Voice (Lexington, Ky.: University Press of Kentucky, 1987), 249.

- Davis, Women, Race, and Class , 188–89.

- Ibid., 178.

- Quoted in Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa, eds., This Bridge Called my Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (New York: Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press, 1983), 61.

- Davis, Women, Race & Class , 213–15.

- Rickie Solinger, ed., Abortion Wars: A Half Century of Struggle, 1950–2000 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 132; Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilization Abuse (CARASA) and Susan E. Davis, ed., Women Under Attack (Boston: South End Press, 1988), 28.

- Quoted in Meg Devlin O’Sullivan, “‘We Worry About Survival’: American Indian Women, Sovereignty, and the Right to Bear and Raise Children in the 1970s,” Dissertation, (Chapel Hill: 2007). Available online at www. cdr.lib.unc.edu/indexablecontent?id=uuid:7a462a63-5185-4140-8f3f-ad094b75f04d&ds=DATA_FILE .

- Guardian (US), April 12, 1989, 7.

- Jael Silliman, Marlene Gerber Fried, et al., Undivided Rights: Women of Color Organize for Reproductive Justice (Cambridge: South End Press, 2004), 10.

- Davis, 204.

- Ibid., 215.

- Ibid., 175.

- Ibid., 176.

- Lydia Sargent, ed, Women and Revolution: A Discussion of the Unhappy Marriage of Marxism and Feminism (Cambridge, Mass.: South End Press, 1981), 94.

- Davis, 182.

- Quoted in Davis, 174.

- Ibid., 173.

- Smith, op cit., xxxi.

- Moraga and Anzaldúa, The Bridge Called My Back , 146.

- Smith, Home Girls , 257–58.

- Vladimir Ilyich Lenin, “What Is To Be Done? Burning Questions of our Movement,” Lenin’s Collected Works Vol. 5 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1973), 412. Available online at www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1901/witbd/iii.htm .

- Combahee River Collective.

- Martha Gimenez, “Marxism and Class, Gender and Race: Rethinking the Trilogy,” Race, Gender & Class (2001: Vol. 8, No. 2), 22–33. Available online at www.colorado.edu/Sociology/gimenez/work/cgr.html .

Search form

"A sense of hope and the possibility for solidarity"

Sapronov and the russian revolution, standing up to the zionist backlash against bds, legacies of colonialism in africa, austerity, neoliberalism, and the indian working class, disability and the soviet union: advances and retreats, the critical communism of antonio labriola, austerity, neoliberalism, and the indian working class, the legacy of louis althusser, "a sense of hope and the possibility of solidarity", islamic fundamentalism, the arab spring, and the left, knocking down straw figures, have the democrats evolved, giving voice to the syrian revolution, from “waste people” to “white trash”, defending our right to criticize israel.

Racial Justice Resources for Activists, Advocates & Allies

- Black History Month

- Ableism & Disability Justice

Black feminism

- Civil Rights

- Educational Equity

- Healthcare / Health Disparities

- Higher Education

- Mental Health

- Microaggressions

- Racial Gaslighting

- Policing | Prisons

- Stereotypes

- Structural & Systemic Racism

- Voting Rights

- Anti-racism

- Critical Race Theory

- Intersectionality

- Activism

- BIPOC Resources

- Black Lives Matter

- CARA members

- Data / Web Tools

- Facilitating conversations about race

- Local Resources (Cincinnati & Ohio)

- UC Resources

- Librarianship

How to use this guide: Black feminism

Scroll through or click on a link below to explore the topics on this page

- Black feminism: videos

- Black feminism: web resources

- Black feminism: podcasts

- Black feminism: books

“If, as Black feminists contended, oppression positioned Black women at the lowest rung on the social ladder, then eradicating their oppression would necessarily ameliorate oppression for everyone” -Robert J. Patterson

Black feminism videos

Beverly Guy-Sheftall – Say Her Name: The Urgency of Black Feminism Now Black feminist discourse and activism have been significant interventions in a variety of social justice movements in the U.S. since the 19th century, though this has not always been acknowledged. In the aftermath of reforms catalyzed by the Black Lives Matter Movement, a queer black feminist project, Guy-Sheftall’s talk will reflect upon the transformations in civil society, academe, electoral politics, the criminal justice system, and other spaces that have occurred over the past year as a result of recent protests around systemic racism and other issues.

Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor: What We Can Learn From the Black Feminists of the Combahee River Collective We continue our interview with Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor about the new collection of essays she edited that, titled How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective.

Black feminism: web resources

Black feminism: podcasts.

Black feminism books

- << Previous: Bias

- Next: Civil Rights >>

- Last Updated: Mar 5, 2024 4:33 PM

- URL: https://guides.libraries.uc.edu/racialjusticeresources

University of Cincinnati Libraries

PO Box 210033 Cincinnati, Ohio 45221-0033

Phone: 513-556-1424

Contact Us | Staff Directory

University of Cincinnati

Alerts | Clery and HEOA Notice | Notice of Non-Discrimination | eAccessibility Concern | Privacy Statement | Copyright Information

© 2021 University of Cincinnati

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- Future Fables

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Just the Right Book

- Lit Century

- The Literary Life with Mitchell Kaplan

- New Books Network

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

The Foundations of Black Feminism and Womanism: A Reading List

Negesti kaudo lists some pillars of womanist writing.

What does it mean to be Black, American, and a woman? While trying to answer this question, I searched retroactively, exploring the writing of womanists and Black feminists before me. The authors included on this list have lived and survived a different era of the United States of America and its tumultuous relationship with Black women. Womanism is a form of feminism that focuses on achieving equity as a community, specifically for Black women, men, and children, in contrast to feminism, which ebbs and flows to and from its original intent over the years.

The original definition of womanism is much longer and describes different versions of what a womanist can look like, which, in many ways, each of these books expands upon. This list is not definitive, and certainly not exhaustive, but the works of the following writers have helped me understand womanism, Black feminism, and my role as a Black woman artist in the movement, both now and in the future.

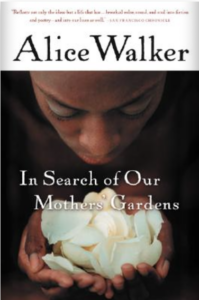

Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose (Amistad Press)

The collection includes a selection of works from 1966–1982, in which Walker writes about everything from Black art and creativity and the civil rights movement to female artists like Zora Neale Hurston and Georgia O’ Keefe. Amongst these works is Walker’s 1981 essay “Gifts of Power,” which focuses on the origins of the Shaker community in upstate New York during the late 1800s, whom she describes as womanists. Her argument is that because the Shakers were women who had left their husbands to live and commune together (chastely of course, due to celibacy) many would label them “lesbians,” but their relationship as a community of women that existed independently was something more… And to Walker, that meant they fit into a category of womanist.

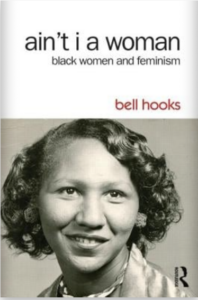

bell hooks, Ain’t I a Woman: Black Women and Feminism (Routledge)

bell hooks explores the history of feminism and its impact on Black women by analyzing the ways the feminist movement has consistently excluded us in order to achieve progress. But the movement’s idea of “progress” aims for women to reach equality with white men, rather than equity for Black women and black men (as well as white women). I think about this book every day since I read it. Ain’t I a Woman asks the reader to be critical of the motives behind feminism and the spaces created to serve it and teaches us if that space doesn’t serve us, how to create out own.

Ed. by Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, How We Get Free: Black Feminism and the Combahee River Collective (Haymarket Books)

If you consider yourself a womanist or a Black feminist, then this book should be on your list. How We Get Free is a timely reminder of the ways that Black women have helped organize and lead the charge for antiracism and women’s liberation. In a collection of interviews between Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor and the founding members of The Combahee River Collective—a group of radical Black feminists who have been organizing since 1974—this book compares contemporary activism to that of our foremothers, exploring the legacy of Black feminism and its impact today.

Morgan Parker, Magical Negro (Tin House Books)

This startling book of poems is a stark follow-up to Morgan Parker’s witty debut, There Are Things More Beautiful Than Beyoncé . At the 2019 AWP conference in Portland, Parker said she felt the ancestors’ presence with her as she wrote the poems in Magical Negro . The collection explores the characters of different “magical negroes” in pop culture, daily microaggressions (be they from dating a “Matt” or running into white women at the braid shop), and, in general, what it’s like to live as a Black woman in 21st-century America.

Ed. by Idrissa Simmonds, Jamila Woods, and Mahogany L. Browne, Black Girl Magic: The Breakbeat Poets Volume 2 (Haymarket Books)

Following The BreakBeat Poets Volume 1 , the editors of Volume 2 have selected a collection of poems that assert the space that Black women hold in the hip-hop world and offer various lyrical perspectives of Blackness and womanhood in America today from more than 60 writers. Insightful, inspiring, relatable, and sometimes even heartbreaking, Black Girl Magic encompasses the wealth, beauty, and range of Black women.

Mikki Kendall, Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women That a Movement Forgot (Viking)

Mikki Kendall’s collection of essays Hood Feminism focuses on contemporary feminism and explores the way it fails to be inclusive for all women; instead, it is positioned to support a select few. Kendall uses her own experiences to breakdown the feminist movement in a bold, but necessary, follow-up to the bell hooks’ criticism of the feminist movement in Ain’t I A Woman .

Ed. by Erica Hunt and Dawn Lundy Martin, Letters to the Future: Black Women/Radical Writing (Kore Press)

As an essayist, I love anthologies, where I can find a lot of different perspectives and voices all in one place. Inspired by Octavia Butler, editors Erica Hunt and Dawn Lundy Martin asked writers to respond to the following prompt: “In the radical sum of the thinking in your work, you encourage the reader to look where no one else is looking, to tune into registers that provide critical cues for the future.” The work in this collection of radical Black women writers bends the rules of genre and explores matters of intersectionality without confining itself to the language or ideas of writing that have been made “tradition” or “canon” by popularized white writers in the past. The pieces in this collection stray away from how writers and artists are taught to understand genre and form, with each writer molding their craft to create a space in the canon carved from their own image.

__________________________________

Ripe: Essays by Negesti Kaudo is available via Mad Creek Books.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

Negesti Kaudo

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

Taking the “Ick” Out of “Sick Lit.” A Reading List

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

Black Feminism: A Revolutionary Practice Essay

The Black Feminist Movement was organized in an endeavor to meet the requirements of black women who were racially browbeaten in the Women’s Movement and sexually exploited during the Black Liberation Movement. Therefore it can be said that the movement developed as a rejoinder to the above-mentioned two movements. Black women were an indistinguishable class whose survival and wants were disregarded. The purpose of the movement was to build up a premise that could effectively bring to a halt, the racist, sexist, and classist prejudice that were interrelated in their lives. The Women’s Liberation Movement has been regarded as the sole chattels of white middle-class women. If any black woman is seen drawn to this movement, it was ridiculously dealt with. This disinclination comes from the attitude that those who are subjugated cannot do the same to others. Faced with the sexism of black men and the racism of white women, black women in their relevant actions had two ways- they could either linger in the movements or strive to teach non-black or non-female companions about their requests, or they could be in possession of a movement. The first option, though dignified in its purpose, was not feasible since it was not exclusively their task to instruct the so-called class. Bringing up a Black Feminist Movement was not an easy mission. Despite the call for such a movement, few black women were eager to recognize themselves as feminists. Having determined to outline a movement in their hold, black women were required to delineate the objectives of the Black Feminist Movement and to verify its hub. The black woman ought to be strapping against the maltreatment shown to them simply for the reason of their subsistence in this world.

The white racists as well as the black nationalists categorize them as ‘Matriarchs’, as they had practically no constructive personality to authenticate their survival. Black women who crave liberation are to be self-righteous, noble, and free from all the improbable and deviant notions of prettiness and womanhood. They must not allow themselves to be kept upon a plinth, thereby allowing mocking at by those who pretend to be superior. The efficacy of the movement has not been homogeneous in the white feminist and black communities. Many white women in the feminist movement have accredited their racial discrimination and made attempts to address it in anti-racist instruction seminars. The Black Feminist Movement had to proceed through thorny paths. Most prominently, the movement was aimed to hit upon a means to expand their hold amidst the black and Third World women. The women who have little or no entry to the movement were also to be given awareness about the true nature and aim of the movement as well as resources and strategies for change through instructions. It has been tough for black women to come forward from the numerous imprecise descriptions that have reflected them as disgraceful beings. The movement was set as a target of the Black Liberation Struggle to hearten all skilled and efficient black women to emerge, strong and gorgeous, without the inferior feeling of culpable or discordant. This objective was to empower black women and enable them to mount up and reach the destination of leadership and reputation in the black community. Even though there were numerous movements for black, for example, the Civil Rights Movement, Black Nationalism, and others, all the movements were categorized under the title Black Liberation Movement. The movement, though apparently for the emancipation of the black race, was actually organized for the liberation of the black male.

The Black Feminist Movement has resulted in the formation of other similar risings intended to end oppression. In order to be again successful in its mission, the the movement had to cling to the existing male-oriented black liberation movement as well as move with its procedures. Indeed, all the black feminist movements did not reach their destination however some of them moved on and are still in motion to achieve the goal.

Works Cited

The National Black Feminist Organization’s Statement of Purpose, issued in 1973 (Customer had provided the reference).

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, May 12). Black Feminism: A Revolutionary Practice. https://ivypanda.com/essays/black-feminist-organizations/

"Black Feminism: A Revolutionary Practice." IvyPanda , 12 May 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/black-feminist-organizations/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Black Feminism: A Revolutionary Practice'. 12 May.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Black Feminism: A Revolutionary Practice." May 12, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/black-feminist-organizations/.

1. IvyPanda . "Black Feminism: A Revolutionary Practice." May 12, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/black-feminist-organizations/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Black Feminism: A Revolutionary Practice." May 12, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/black-feminist-organizations/.

- Strapping Products and Hyacinth Belt Design

- Classism as a Complex Issue of Discrimination

- How to Be an Antiracist Book by Kendi

- Can America Ever Be Completely Anti-Racist?

- The Basis of Good Government according to Analects

- Genetically Identical Twins and Different Disease Risk

- Beauty and Culture

- Task of Negro Womanhood

- The Science of Why You Crave Comfort Food

- Scene of Troy’s Madness in "Fences" Play and Film

- Positive Changes That Feminism Brought to America

- Are Feminist Criticisms of Militarism Essentialist?

- Feminist Approach: Virginia Woolf

- Western Feminist Critics and Cultural Imperialism

- Islamic Thought: Women in Islamic Perspective