Home — Essay Samples — Entertainment — Concert Review — Concert Report: The Impact of Live Music on Society

Concert Report: The Impact of Live Music on Society

- Categories: Concert Review Music Industry

About this sample

Words: 609 |

Published: Mar 16, 2024

Words: 609 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

The social impact of concerts, the economic impact of concerts, the psychological impact of concerts.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Karlyna PhD

Verified writer

- Expert in: Entertainment

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

4 pages / 1930 words

2.5 pages / 1220 words

2 pages / 1006 words

2.5 pages / 1035 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Concert Review

Music has the power to bring people together and transcend barriers. Attending a concert is not only a chance to enjoy live music but also to immerse oneself in a unique cultural experience. As a college student, I had the [...]

In the last couple of months, I attended two concerts for my music report. The first concert was Maximus Musicus Visits the Orchestra which was held on 3 June 2018 at the Malaysian Philharmonic Orchestra(MPO). The second concert [...]

I decided to go to the “Dimensions in Jazz” concert which was directed by Wade Judy, Dr. Eric Bush, and Marko Marcinko. Before the performance started, there was a wide range of people entering. Some were students and some were [...]

After watching “I Lived” I felt as if I could do more to live my life to the fullest. The boy in the video is unfortunately affected by Cystic Fibrosis, yet he lives as if he does not have it. He does not let it get in the way [...]

Attending a jazz concert for the first time was a great experience; it was performed at Mt. Sac’s Feddersen Recital Hall on October 19, 2019. The musicians who took part in it were Bob Sheppard who alternated between the alto [...]

In this essay I will make a report on the classical music concert I’ve visited. This was the first classical music concert that I have been to in my life so I guess I didn’t really know what to expect. When we drove past the [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

What’s behind the magic of live music?

Associate Professor of Music and Music Theory, Columbia University

Disclosure statement

Mariusz Kozak does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

View all partners

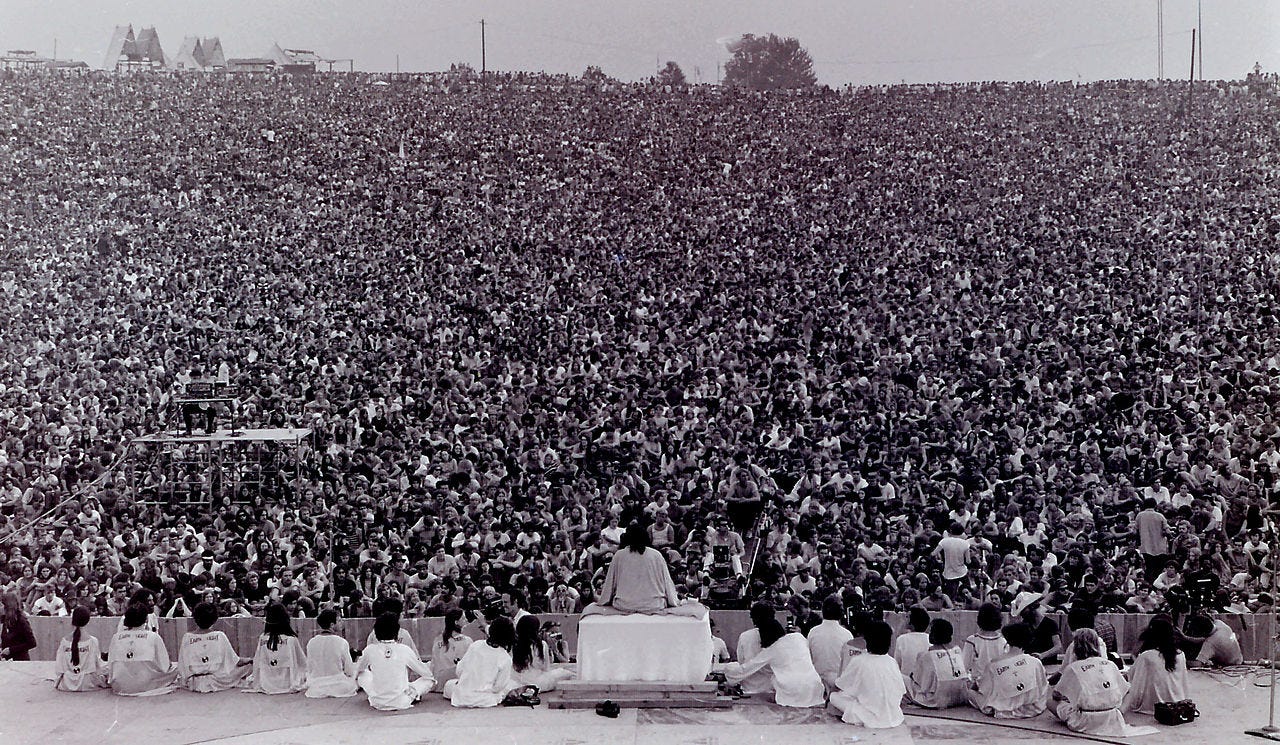

For months, fans were relegated to watching their favorite singers and musicians over Zoom or via webcasts. Now, live shows – from festivals like Lollapalooza to Broadway musicals – are officially back.

The songs that beamed into living rooms during the depths of the COVID-19 pandemic may have featured an artist’s hits. But there’s just something magical about seeing music surrounded by other people. Some fans reported being so moved by their first live shows in nearly two years that they wept with joy .

As a music theorist , I’ve spent my career trying to figure out just what that “magic” is. And part of understanding this requires thinking about music as more than simply sounds washing over a listener.

Music as more than communication

Music is often thought of as a twin sister to language . Whereas words tend to convey ideas and knowledge, music transmits emotions.

According to this view, performers broadcast their messages – the music – to their audience. Listeners decode the messages on the basis of their own listening habits, and that’s how they interpret the emotions the performers hope to communicate.

But if all music did was communicate emotions, watching an online concert should’ve been no different than going to a live show. After all, in both cases, listeners heard the same melodies, the same harmonies and the same rhythms.

So what couldn’t be experienced through a computer screen?

The short answer is that music does far more than communicate. When witnessed in person, with other people, it can create powerful physical and emotional bonds .

A ‘mutual tuning-in’

Without physical interactions, our well-being suffers. We fail to achieve what the philosopher Alfred Schütz called a “ mutual tuning-in ,” or what the pianist and Harvard professor Vijay Iyer more recently described as “ being together in time .”

In my book “ Enacting Musical Time ,” I note that time has a certain feel and texture that goes beyond the mere fact of its passage. It can move faster or slower, of course. But it can also thrum with emotion: There are times that are somber, joyous, melancholy, exuberant and so on.

When the passage of time is experienced in the presence of others, it can give rise to a form of intimacy in which people revel or grieve together. That may be why physical distancing and social isolation imposed by the pandemic were so difficult for so many people – and why many people whose lives and routines were upended reported an unsettling change in their sense of time .

When we’re in physical proximity, our mutual tuning-in toward one another actually generates bodily rhythms that make us feel good and gives us a greater sense of belonging . One study found that babies who are bounced to music in sync with an adult display increased altruism toward that person, while another found that people who are close friends tend to synchronize their movements when talking or walking together.

Music isn’t necessary for this synchronization to emerge, but rhythms and beats facilitate the synchronization by giving it a shape.

On the one hand, music encourages people to make specific movements and gestures while they dance or clap or just bob their heads to the beat. On the other, music gives audiences a temporal scaffold: where to place these movements and gestures so that they’re synchronized with others.

The great synchronizer

Because of the pleasurable effect of being synchronized with people around you, the emotional satisfaction you get from listening or watching online is fundamentally different from going to a live performance. At a concert, you can see and feel other bodies around you.

Even when explicit movement is restricted, like at a typical Western classical concert, you sense the presence of others, a mass of bodies that punctures your personal bubble.

The music shapes this mass of humanity, giving it structure, suggesting moments of tension and relaxation, of breath, of fluctuations in energy – moments that might translate into movement and gesture as soon as people become tuned into one another.

This structure is usually conveyed with sound, but different musical practices around the world suggest that the experience is not limited to hearing. In fact, it can include the synchronization of visuals and human touch.

For example, in the deaf musical community, sound is only one small part of the expression. In Christine Sun Kim’s “ face opera ii ” – a piece for prelingually deaf performers – participants “sing” without using their hands, and instead use facial gestures and movements to convey emotions. Like the line “fa-la-la-la-la” in the famous Christmas carol “ Deck the Halls ,” words can be deprived of their meaning until all that’s left is their emotional tone.

In some cultures, music is, conceptually, no different from dance, ritual or play. For example, the Blackfeet in North America use the same word to refer to a combination of music, dance and ceremony. And the Bayaka Pygmies of Central Africa have the same term for different forms of music, cooperation and play.

Many other groups around the world categorize communal pursuits under the same umbrella.

They all use markers of time like a regular beat – whether it’s the sound of a gourd rattle during a Suyá Kahran Ngere ceremony or groups of girls chanting “Mary Mack dressed in black” in a hand-clapping game – to allow participants to synchronize their movements.

Not all of these practices necessarily evoke the word “music.” But we can think of them as musical in their own way. They all teach people how to act in relation to one another by teasing, guiding and even urging them to move together.

In time. As one.

[ Get the best of The Conversation, every weekend. Sign up for our weekly newsletter .]

- Relationships

- Communication

- Live performance

- Musical theatre

- Synchronization

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

Data and Reporting Analyst

Lecturer (Hindi-Urdu)

Director, Defence and Security

Opportunities with the new CIEHF

What is Dance’s Relationship with Live Music?

Live music adds an extra layer of liveness to a performance, one that encourages performers to tune in to one another and that invites audiences to experience heightened sensual awareness.

Introduction

Live dancing paired with live music creates rich, multi-sensory experiences for audiences and performers alike. This combination enables a give-and-take between dancers and musicians as they work together to co-create the performance pieces on stage. They tune into one another so that dancers hear and musicians see, which produces something that the audience can feel. Live music and dance are fixtures at the Pillow. This essay aims to explore dance through the lens of live music, which actually illuminates the thematic content of the performance works.

When the pairing of live music and dance is done well, dancers and musicians sync up so precisely it seems it would be impossible for one to perform without the other. For an audience, live music fills the ears as the live dancing fills the eyes. For dancers, performing with live music changes their sensitivity and attention to it. That said, it is not always the case that musicians and dancers are discrete groups of people on stage. Borrowed Light (2006, 2012), ETM: The Initial Approach (2014) and ETM: Double Down (2016), and Moses(es) (2014) testify to this fact. In these pieces, the line between musicians and dancers is blurry, as everyone on stage moves and makes music together.

Borrowed Light: Staging Community

Borrowed Light , a collaboration between the Tero Saarinen Company of Finland and the Boston Camerata, offers a compelling juxtaposition of off-centered movement with music that is even and measured. The Shaker tunes and the performance of them by the Boston Camerata are bouncy, articulate, and sung mostly in unison with occasional simple harmonies, while the movement of the dancers spirals around itself, swinging and falling. Dancers lurch forward only to spill backward. They throw their energy up, out, and all around them. These movements are amplified by the whirl of their costumes, and in some moments, the dancers unleash their own momentum as their fellow dancers control them by pulling on their thick leather belts.

One theme Saarinen refers to whenever he discusses Borrowed Light is community. The piece uses Shaker spirituals as its music and follows an architectural principle employed in Shaker residences to maximize daylight as the premise of its lighting design. Importantly to Saarinen, the piece does not represent Shakers explicitly, but rather, the piece explores the feeling and spirit of community embedded in the Shaker experience.

From its inception, Borrowed Light was also about another community—the one the performers would create by uniting the Boston Camerata with the Tero Saarinen Company. In response to a question about the ways the dancers and singers support one another in performance, Saarinen discusses his objective to “weave together these two communities” in this piece.

The voices of the singers paired with the body percussion and heavy stepping and stomping of the dancers; the three-dimensional circling and spiraling of the dancers paired with the constant presence and gaze of the singers—this piece would not be so powerful if one were seen or heard without the other. While there are distinct differences between the singers and dancers, the choreography often integrates the two groups. The singers traverse the stage throughout the piece, sometimes joining the dancers as they side-step their way around a large circle or as they slowly travel in a line, moving from upstage toward the audience.

The following excerpt brings the two groups together. As the singers’ voices repeat a verse again and again, the dancers dance themselves almost to exhaustion. Over time, the singers create a small clump at the center of the stage, a vortex around which the dancers circle and leap, stomp and slap. Together, the movement and sound build to a frenzied, delirious, almost crazed energy.

Borrowed Light feels complete for its integration of movement with voices, costumes, and lighting. As a theatrical enterprise, Borrowed Light invests time and energy into collaboration, into design, into integrating each of the elements that makes up a living piece of art. The singers and dancers of Borrowed Light create a cohesive community and an exquisite performance piece. The integration of a cappella voices, body rhythms, and full-bodied, space-eating movements, epitomizes the rich sensory experience created throughout the piece.

MOSES(ES): A Single Idea Unfolding Infinitely

Choreographer Reggie Wilson is no stranger to Jacob’s Pillow. His company, Reggie Wilson / Fist and Heel Performance Group first appeared in the Inside/Out series with Love in 1996 followed by a repertory program in 1998, and then in the Doris Duke Theatre with The Tale in 2007, Moses(es) in 2014, and POWER in 2019. As an artist, Wilson says he likes the idea of “taking something unmanageable and trying to make it manageable,” which is the challenge he presented himself with in his piece Moses(es). While the title of the piece refers to the biblical figure of Moses, and while the piece is in some ways about that figure, Moses is really just the beginning. When asked about how his relationship to Moses(es) changed in the process of making the piece, Wilson reveals the complex simplicity that this piece is all about.

Approaching Moses(es) from the perspective of the relationship between dancing and live music illuminates this central premise of the piece—a single idea, unfolding infinitely. On the integration of music and sound in the piece, Wilson purposefully created an interactive sound score, which enables his investigation of layers of ideas, piling high, shifting, unfolding, aligning, dissembling, multiplying.

The piece uses recorded music from Louis Armstrong, The Klezmatics, and the Blind Boys of Alabama, to name only a few. In performance, Wilson along with vocalists Lawrence Harding and Rhetta Aleong add live singing, chanting, and percussion to the sound score. The dancers also occasionally lend their voices to the performance, as when they chant a fractal equation alongside the vocalists’ live and recorded voices.

The concept of fractals is one point of entry for Wilson in exploring the infinite unfolding of an idea. Fractals are complex patterns that repeat themselves in ever-smaller scales. In Moses(es) , however, the notion of fractals produces an ever-expansive range of ideas, images, and movements. In a section of Moses(es) that specifically engages a fractal equation, Wilson uses fractals as a metaphor for the infinite potential of all of this layering. Though this section does not use music, it does layer a variety of sound qualities from multiple voices, which is a distinctive characteristic of this piece. The sound score for this section includes recordings of the vocalists speaking a fractal equation alongside their live voices, which also recite the equation. At the start of the section, even the dancers speak as they move. In the beginning it seems easy to identify the correlations between movements and words as dancers chant and move simultaneously and in unison. However, over time, as the movements expand, those markers disappear. It becomes impossible to identify patterns or relationships between movements among the dancers and between movements and words, as seen in this brief excerpt from the piece.

In moments of transition, live voices bump up against recordings. Lighting shifts. Singers chant and move. Dancers pace. As these moments layer visual and aural experience, they also blur distinctions between seeing, hearing, and feeling. In one of these transitions, the movement and tone of the piece shift abruptly. As vocalists chant-sing, “Eli, Eli! Somebody call Eli,” their arms gesture up, down, and out, while their feet perform a stepping pattern from a folk dance. Suddenly a recording of female throat singing by the Ngqoko Women’s Ensemble interrupts their voices and, at the same time, dancers begin running across the stage. The vocalists join in this spilling, connecting, and constantly shifting movement. In this exploration of community, no one performer ever emerges as a singular leader.

Near the end of the piece, we see the return of a community that had been established as performers touch one another to connect, then exploding out only to reassemble again. This time it happens in slow motion as Wilson calls out, “Moses, Moses, don’t get lost,” and dancers respond, “in that red sea.”

The integration of movement with live and recorded sound involving both dancers and singers displays the already interconnected community of Reggie Wilson/Fist & Heel Performance Group. Addressing the theme of Moses in this piece, audiences encounter the integration of leaders and followers as essential to a unified community.

ETM: Dance is Music is Dance

As in other tap dancing, in the ETM series from Dorrance Dance, dancing creates music. ETM , which stands for electronic tap music, is a play on EDM, electronic dance music. What sets ETM apart from other tap dance performance is the ways the wired dance boards upon which the performers dance also add tone and timbre and electronic dimensions of sound inaccessible by shoes alone.

Artistic director (and 2013 Jacob’s Pillow Award winner) Michelle Dorrance has cultivated a distinct aesthetic that encourages tap dancers to engage the entire body while dancing. The tap dance boards offer dancers a new challenge, which makes this full-bodied dancing even more exciting. Dancers stretch to reach a board. They end spins at just the right moment. They jump up and hang in the air until the moment they have to play their next note.

The use of technology certainly makes this piece stand out from the tap dance pack, but it does not get all of the credit. The choreography, improvisation, and staging of this piece epitomize the quality of innovation that is embedded in tap dance as a form. In the ETM series, Dorrance Dance transforms upon its own original innovation. With ETM: Double Down , Dorrance expanded upon what was already a rich investigation of the potential of bodies to make sound/music in an earlier iteration of the piece dubbed ETM: The Initial Approach . A side-by-side comparison of one scene from each iteration reveals the tremendous choreographic development from the Initial Approach to Double Down . In the Initial Approach three dancers shift in and out of simple choreographed steps and individual improvisations.

In Double Down , those original steps and rhythms remain, but by using the full company of dancers for the scene in Double Down , Dorrance more than doubles the dimensions of movement and sound on stage. Additionally, when the tap dancers face upstage keeping a steady beat with side-to-side crawling steps, b-girl Ephrat “Bounce” Asherie’s movements stand out downstage.

Dorrance Dance

ETM: Double Down

Michelle Dorrance and her collaborator Nicholas Van Young talk about the many ways they expanded their use of technology in Double Down . They also address ways this enhanced the possibilities of dancers making music in the moment of performance.

While electronic music is certainly foregrounded in the ETM series, the show does not completely abandon acoustic tap dance. The moments when the dancers put metal to wood without assistance from computer software are all the more pronounced in this show. That said, as with the rest of ETM , even in acoustic moments the sounds of tap dancing are augmented with other textures of sound. In the section aptly titled “Boards and Chains,” dancers tap atop acoustic wood platforms, which are fitted with a strip of corrugated metal along one side. Each dancer also manipulates a long metal chain, dropping it onto the board in time with the dancing.

ETM reminds audiences that tap dancers are also musicians. Their bodies constantly interact with technology, with the floor, and with the body itself to create music and dance simultaneously.

In a 2017 PillowTalk entitled “Tap Today,” Dorrance and Dormeshia, co-directors of several different tap programs in the School at Jacob’s Pillow, discuss the relationship between tap dance and music.

By integrating musicians and dancers in these pieces and blurring the lines between who dances and who makes music, Borrowed Light , ETM , and Moses(es) persistently remind viewers of the liveliness of performance.

To see even more instances of live music and dance at the Pillow, check out the Live Music playlist on Jacob’s Pillow Dance Interactive. These excerpts illustrate many different ways choreographers engage with live music. For example, note that in Dance Heginbotham’s Chalk and Soot and Jessica Lang Dance’s Within the Space I Hold musicians join the dancers on stage as in the pieces discussed above. However, in the choreography by Heginbotham and Lang, while musicians and dancers do not physically interact, the musicians are responsive to the action unfolding before them.

PUBLISHED NOVEMBER 2021

More essays in this theme, the jacob’s pillow costume collection, pointe spread: the marvel of regional ballet, when the ballet came to jacob’s pillow, contemporary bharatanatyam at jacob’s pillow, uncovering jazz elements in the work of contemporary choreographers, the israeli delegation: artists from the holy land, broadway in becket: the american musical theater and jacob’s pillow, introduction to bharatanatyam and t. balasaraswati, performing the body: somatic influences in dance, explore themes | essays, dance and society, men in dance, women in dance, dance of the african diaspora, discover more, get the latest in your inbox.

Receive a monthly email with new and featured Jacob’s Pillow Dance Interactive videos, curated by Director of Preservation Norton Owen.

Live Performance in Today’s Culture Essay

The music industry is especially dependent on the recording. Recordings allow singers to eliminate imperfections in their performance and enhance its quality (Caramanica). Both recordings and live concerts are popular in the American society. However, this topic is highly controversial because sometimes recordings can alter artists’ voice beyond recognition. During a live performance, one can see the clear difference between the recording and the actual voice of a singer. Sometimes it can be better, but quite often it is otherwise.

Indeed, attending musical concerts is a big part of our culture. Live music performances do not only bring aesthetic pleasure. According to the Australasian Performing Right Association report, “Active engagement with music has been shown to increase positive perceptions of self, which in turn leads to greater motivation, manifesting in turn in enhanced self-perceptions of ability, self-efficacy, and aspirations” (10). A substantial amount of research investigating the effects of live performances on people has found that attending concerts with live performance and seeing live art performances improved the well-being of a person, build social capital and increase appreciation of music.

On the other hand, some artists can disappoint the audience because their real voice greatly differed from the recording. They undeservingly become famous and rip off listeners on concerts. I believe that good live performances leave a good impression on a person. For example, once I bought an expensive ticket to the concert of a famous pop singer and was highly disappointed. Another time, the live music performed by that band was very sensitive and touched my heart and gave me the feeling of belongingness. In my opinion, live performances are needed to inspire people and enrich their spirituality.

Works Cited

Australasian Performing Right Association. The Economic and Cultural Value of Live Music in Australia 2014. 2014. Web.

Caramanica, Jon. “Pitched to Perfection: Pop Star’s Silent Partner.” NY Times , 2012, Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, May 24). Live Performance in Today’s Culture. https://ivypanda.com/essays/live-performance-in-todays-culture/

"Live Performance in Today’s Culture." IvyPanda , 24 May 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/live-performance-in-todays-culture/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Live Performance in Today’s Culture'. 24 May.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Live Performance in Today’s Culture." May 24, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/live-performance-in-todays-culture/.

1. IvyPanda . "Live Performance in Today’s Culture." May 24, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/live-performance-in-todays-culture/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Live Performance in Today’s Culture." May 24, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/live-performance-in-todays-culture/.

- Anti-Franklinian Stance of Rip Van Winkle’s Character

- “Rip Van Winkle” the Story by Washington Irving

- "Rip Van Winkle" by Washington Irving

- The Meaning of Life on One's Story

- University Students’ Emotions in Lectures

- Heritage – A Sense of Belongingness

- “Rip Van Winkle”: Rip Van Winkle’s Personality

- Routing Protocols: RIP, EIGRP, and OSPF

- Reflection on Interventions

- ISDN, RIP, IGRP, and OSPF on the Cisco Routers and Switches

- Music in Films: Composers, Soundtracks and Themes

- Francois Couperin's Baroque Music

- Commercial Music for Listeners: Poster Discussion

- The Studio and Pre-Recorded Music Usage

- Rafet Elroman Pop Concert: Culture Issues

Laura Pausini: Live Music Event Critique

In this paper, I will present my analysis and reaction to the live concert of Laura Pausini, which took place in Miami on July 26, 2018. The event started at 8:00 PM at James L. Knight Center and lasted for a couple of hours. It was dedicated to Laura’s new album “Hazte Sentir,” and it can be suggested that the concert was held to promote the album and offer Laura an opportunity to come in contact with her fans. As I happen to be one of them, I was excited to attend. I arrived rather early, but the event was worth it, and I was glad to talk to the people who were equally interested in Laura as I waited.

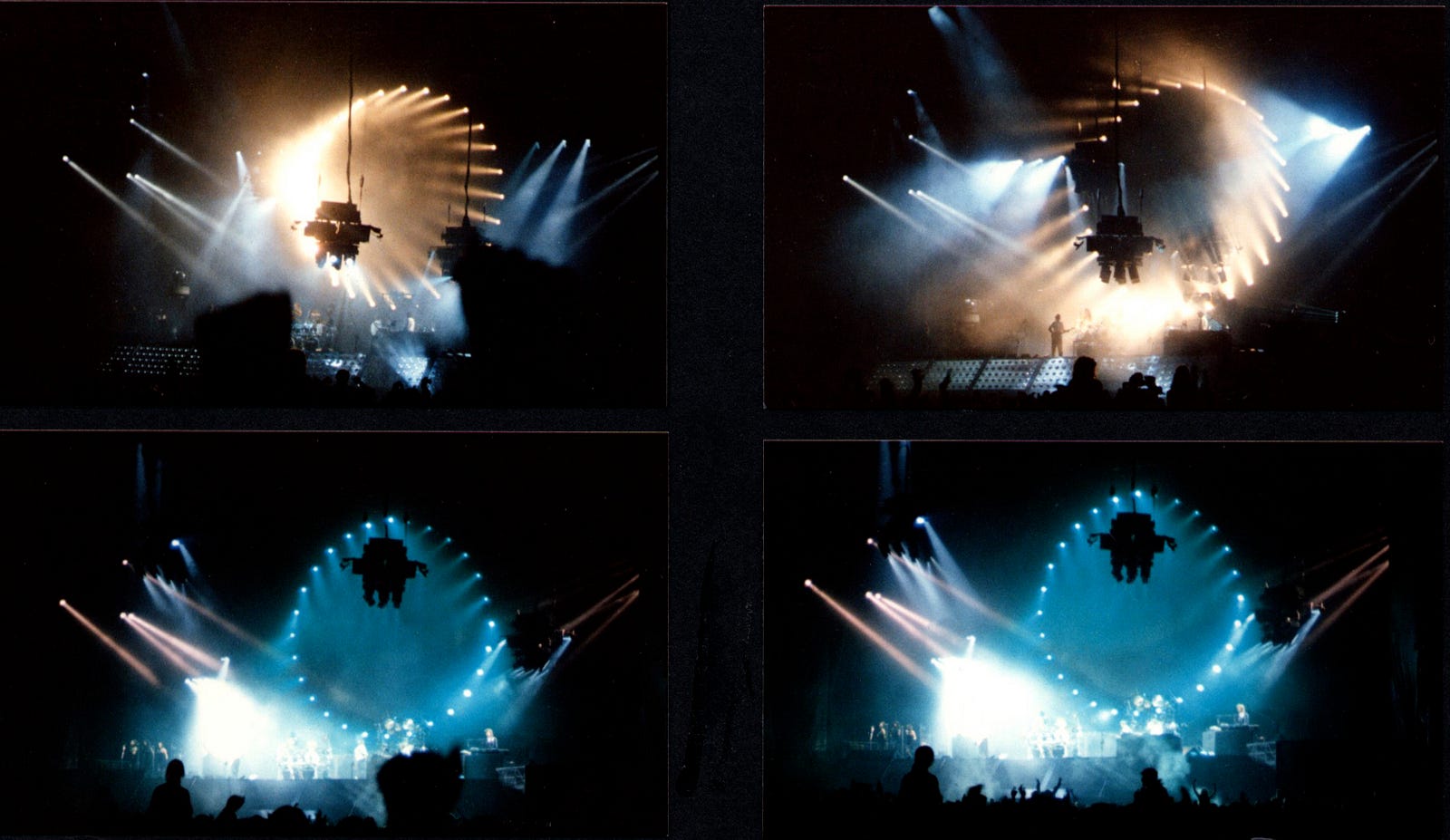

Laura made an exciting entrance, during which the stage and lighting were set in a way that would not draw too much attention to the other performers, but the setting changed very soon. In general, the scene was very dynamic; Laura used it to diversify her performance, and there were instances when other people were placed in the spotlight. Similarly, the lighting and the screen behind the scene were employed to complement the songs and make the performance more entertaining. Additionally, lighting helped Laura in transitions from one song to another. As for costumes, they were not very special; rather, they looked like comfortable and elegant clothing, in which none of the performers was set apart too noticeably. Even Laura’s costumes (she changed them several times) were not very colorful, although they were beautiful.

Laura was not working on her own; she had the support of other singers and musicians who played electric guitars, drums, and a piano. All the mentioned people appeared very skilled to me; the performance was definitely polished. Laura interacted with the performers, but she interacted with the audience even more often. She joked, came up with the comments that would help her introduce new songs, and thanked the audience for their support. She also invited us to sing along with her. It seemed that Laura took the opportunity to communicate with us very seriously.

It was also clear that Laura enjoyed being on the scene and liked her performance. Overall, it appeared to me that Laura and the other performers were working very hard but enjoyed the process. The songs were diverse, especially in their mood, and I loved all of them, but “Nadie Ha Dicho” was the one that was particularly memorable to me because it was the first one. Additionally, it was a very powerful song; it described a lost love and focused on the feelings that remained, which resonated with my personal experiences.

Furthermore, I enjoyed the performance that was designed for the song “Escucha Atento” very much. It involved red lights and images on the screen, which corresponded to the song’s message that was concerned with the concept of independence. I also think that the two songs demonstrated the diversity of Laura’s work: the first one was softer and bittersweet, and the second one was more assertive and energetic. The two songs did not involve instrumental solos, but they placed Laura in the spotlight, which was precisely what I wanted from the concert. Regarding the genre, Laura Pausini Official Website states that she is a pop singer, and it also notes that she has received some Latin music awards. I agree with this classification, and I think that Laura has a distinctive style that has been influenced by multiple genres. Pop-music and Latin music are probably the most prominent ones.

The audience at the concert was rather diverse; I saw men and women of different ages and ethnicities. Also, all the people that I have met seemed to be excited about the event; I think that they were either the fans of Laura or the people who were very interested in Latin pop-music and live concerts. I believe that the reason for this attitude was the fact that Laura’s music was the primary focus of the event; a person who would not enjoy it would have no reason to attend it.

Regarding my personal enjoyment of the event, it was immense. I think that I would have liked it in any case since I was excited about the opportunity from the very beginning. However, the efforts of Laura Pausini and other people who were involved in the process contributed to my experience. The concert was more than a person singing the songs that I was familiar with; rather, it was a performance, which involved much interaction with a singer I admired. While I did not talk to Laura in person, it still felt like it, and I think that it was her intent. As a result, the main thing that I recall about the experience was Laura: she engaged the audience, and she was engaged in the performance herself. That was exactly what I expected to see during a live concert, and it was delivered. As I returned home, I was filled with creative ideas and positive emotions.

Thus, I can conclude that several elements of the concert contributed to its success from my perspective. First, it was the audience: we came to the event because we wanted to be there and were interested in what Laura had to offer. Second, it was the professionalism of the performers: they were skilled and delivered high-quality music. Third, the special effects and settings were noteworthy: they were developed to improve the work and augment the presentation. Most importantly, however, it was Laura who helped me to enjoy the concert: she performed well, employed the special effects to her advantage, and interacted with the audience, giving us what we wanted. I am very grateful to her for this experience.

Laura Pausini Official Website. “Bio.” Laura Pausini Official Website .

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2021, June 21). Laura Pausini: Live Music Event Critique. https://studycorgi.com/laura-pausini-live-music-event-critique/

"Laura Pausini: Live Music Event Critique." StudyCorgi , 21 June 2021, studycorgi.com/laura-pausini-live-music-event-critique/.

StudyCorgi . (2021) 'Laura Pausini: Live Music Event Critique'. 21 June.

1. StudyCorgi . "Laura Pausini: Live Music Event Critique." June 21, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/laura-pausini-live-music-event-critique/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Laura Pausini: Live Music Event Critique." June 21, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/laura-pausini-live-music-event-critique/.

StudyCorgi . 2021. "Laura Pausini: Live Music Event Critique." June 21, 2021. https://studycorgi.com/laura-pausini-live-music-event-critique/.

This paper, “Laura Pausini: Live Music Event Critique”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: March 29, 2022 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

How live music moves us: head movement differences in audiences to live versus recorded music.

- 1 Department of Psychology, Neuroscience & Behaviour, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 2 McMaster Institute for Music and the Mind, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 3 Digital Music Lab, School of the Arts, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada

- 4 Rotman Research Institute, Baycrest Hospital, Toronto, ON, Canada

A live music concert is a pleasurable social event that is among the most visceral and memorable forms of musical engagement. But what inspires listeners to attend concerts, sometimes at great expense, when they could listen to recordings at home? An iconic aspect of popular concerts is engaging with other audience members through moving to the music. Head movements, in particular, reflect emotion and have social consequences when experienced with others. Previous studies have explored the affiliative social engagement experienced among people moving together to music. But live concerts have other features that might also be important, such as that during a live performance the music unfolds in a unique and not predetermined way, potentially increasing anticipation and feelings of involvement for the audience. Being in the same space as the musicians might also be exciting. Here we controlled for simply being in an audience to examine whether factors inherent to live performance contribute to the concert experience. We used motion capture to compare head movement responses at a live album release concert featuring Canadian rock star Ian Fletcher Thornley, and at a concert without the performers where the same songs were played from the recorded album. We also examined effects of a prior connection with the performers by comparing fans and neutral-listeners, while controlling for familiarity with the songs, as the album had not yet been released. Head movements were faster during the live concert than the album-playback concert. Self-reported fans moved faster and exhibited greater levels of rhythmic entrainment than neutral-listeners. These results indicate that live music engages listeners to a greater extent than pre-recorded music and that a pre-existing admiration for the performers also leads to higher engagement.

Introduction

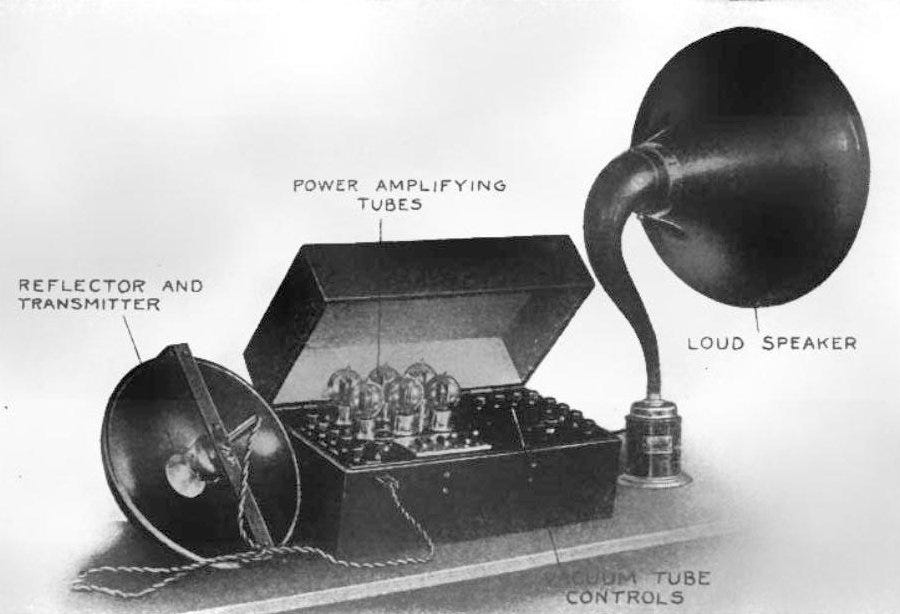

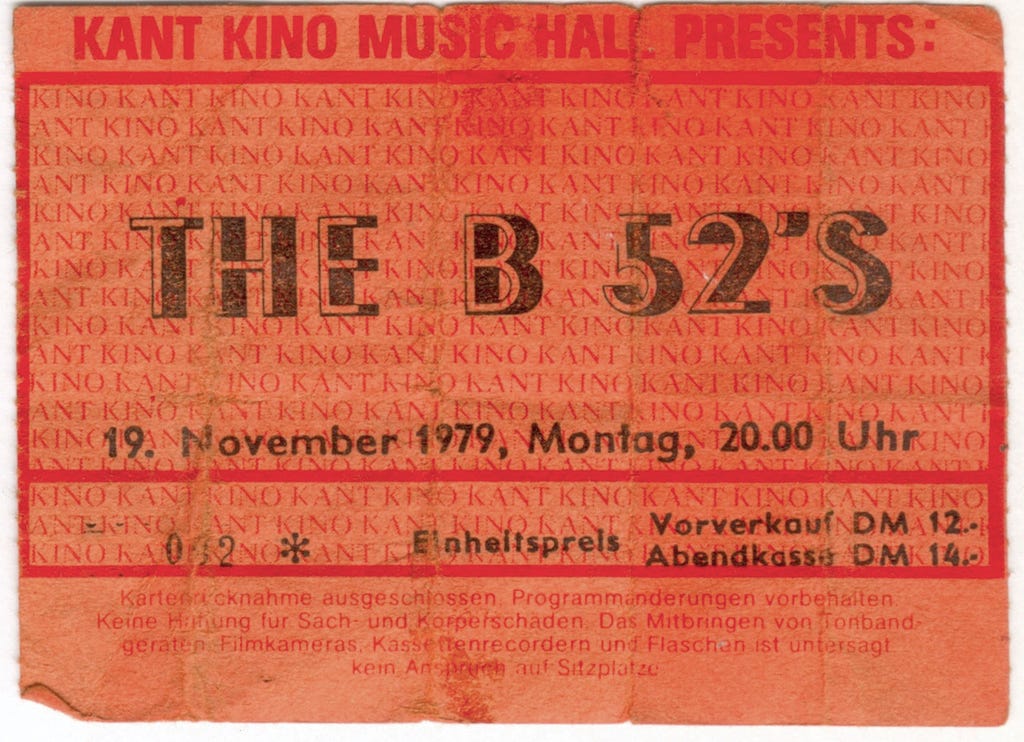

Music is a universal social phenomenon that has traditionally been experienced in a live context ( Nettl and Russell, 1998 ; Freeman, 2000 ). The advent of recording technology in the late 19th century heralded a cultural shift in the way that people experienced music, allowing for the convenience of private, in-home consumption ( Moreau, 2013 ). While technology has provided a low-cost, convenient method for music listening, many people continue to attend live concerts, sometimes at great expense in uncomfortable settings ( Baxter-Moore and Kitts, 2016 ; Brown and Knox, 2017 ). What is it about the experience that motivates listeners to attend live concerts? A survey found that listeners’ strongest musical experiences often took place at live events ( Lamont, 2011 ). Two factors that likely contribute critically to the enjoyment of live concerts are (1) people like the social connexion of experiencing music with other people ( Burland and Pitts, 2014 ; Brown and Knox, 2017 ) and (2) people like the feeling of being connected to the performers, by being in the same physical space together, with the potential for performers to directly engage the audience ( Silverberg et al., 2013 ; Leante, 2016 ), and by experiencing a unique live performance as it unfolds over time ( Brown and Knox, 2017 ). Every live performance is idiosyncratic such that events unfold organically and unpredictably, unlike when listening to a recording in which there is no possibility for an audience to directly affect what a performer has already created.

The social effects of experiencing music with other people have been studied to a greater extent than the effects of experiencing a live performance ( Freeman, 2000 ; Egermann et al., 2011 ; Rennung and Goritz, 2016 ; Stupacher et al., 2017 ). Here we examined the effects of live performance while controlling for the social setting. We compared people who listened to a live performance (specifically, a record release party by Canadian rock star Ian Fletcher Thornley’s 2015 solo album Secrets ) to people who listened in a group in the same venue without live performers to the album recordings of the same songs from Secrets . Recently, research on audiences of live performances has gained interest ( Egermann et al., 2011 ; Burland and Pitts, 2014 ; Danielsen and Helseth, 2016 ; Bradby, 2017 ; Brown and Knox, 2017 ), in part because audiences provide an ecologically valid setting for examining group dynamics. Audience experience has been examined with a variety of techniques including real-time subjective responses ( McAdams, 2004 ; Stevens et al., 2009 , 2014 ; Egermann et al., 2013 ), social networking ( Deller, 2011 ), video analysis ( Chan et al., 2013 ; Silverberg et al., 2013 ; Stevens et al., 2014 ; Leante, 2016 ; Theodorou et al., 2016 ) and physiological measurement ( Fancourt and Williamon, 2016 ; Bernardi et al., 2017 ). It is important to understand effects of the concert setting because attendance may increase health: attending a musical performance was found to reduce stress hormones in audience members ( Fancourt and Williamon, 2016 ) and a 10-year longitudinal study suggested that engagement in cultural events, including concerts, may protect against age-related cognitive decline ( Fancourt and Steptoe, 2018 ).

Enjoying music with other listeners may contribute powerfully to the concert experience. Observers of concert audiences judged synchronously moving listeners as experiencing greater rapport and similar psychological states compared to those moving asynchronously ( Lakens and Stel, 2011 ). After adults move in synchrony, even when unaware of their synchronised movements, they remember more about each other, express liking each other more, and show greater levels of trust and cooperation compared to after moving asynchronously ( Hove and Risen, 2009 ; Wiltermuth and Heath, 2009 ; Valdesolo et al., 2010 ; Valdesolo and DeSteno, 2011 ; Launay et al., 2013 ; Woolhouse et al., 2016 ). More broadly, periodic movements and physiological rhythms, such as breathing and heart rate, tend to synchronise unconsciously among people in a group ( Richardson et al., 2007 ; van Ulzen et al., 2008 ; Morris, 2010 ; Codrons et al., 2014 ; Miyata et al., 2018 ).

Entrainment is defined as the ability to synchronise movements with an external auditory stimulus, in this case the timing regularities of music ( Phillips-Silver and Keller, 2012 ). In humans, synchronisation is supported by connections between auditory and motor cortices ( Sakai et al., 1999 ; Janata and Grafton, 2003 ; Grahn and Brett, 2007 ; Zatorre et al., 2007 ; Fujioka et al., 2012 ) and manifests as oscillatory activity measured in EEG and MEG ( Schroeder and Lakatos, 2009 ; Arnal and Giraud, 2012 ; Fujioka et al., 2012 , 2015 ; Cravo et al., 2013 ; Calderone et al., 2014 ; Cirelli et al., 2014a ; Chang et al., 2018a ). Interestingly, few non-human species entrain movements to auditory regularities ( Merker et al., 2009 ; Patel et al., 2009 ; Schachner et al., 2009 ). The connection between movement synchronisation and social-emotional engagement may have deep evolutionary roots in humans. Infants are not yet able to coordinate their movements to entrain to a musical beat, although they do move faster to music with a faster compared to slower tempo ( Zentner and Eerola, 2010 ). Yet if an infant as young as 14 months is bounced to music synchronously with the movements of another adult, the infant is more likely to help that adult (e.g., to pick up “accidentally” dropped objects needed to complete a task) compared to if an infant is bounced asynchronously with the adult ( Cirelli et al., 2014c ). Later work revealed that this increased helpfulness extends to friends of the experimenter who bounced with them ( Cirelli et al., 2016 ). In another study, infants who were bounced to music with stuffed animals, choose animals that bounced synchronously with them over animals that bounced asynchronously. These studies indicate that synchronisation of movement with others during music listening is a cue that even infants use in the development of social-emotional bonds and altruistic behaviours ( Trainor and Cirelli, 2015 ; Cirelli et al., 2018 ).

We examined the effect of live music while controlling for the effects of being with others in an audience. Little research has examined differences between live and recorded performances by manipulating the presence and absence of the performer. Shoda et al. (2016) reported that the heartbeats of audience members at a live performance exhibited greater entrainment with the musical rhythm than those of listeners at a pre-recorded performance. Performer presence was also found to produce greater relaxation in audience members compared to those listening to a recording ( Shoda et al., 2016 ). Contemporary popular performers often play variations of recorded works at live performances ( Shoda and Adachi, 2015 ), suggesting a novelty factor for listeners. Brown and Knox (2017) found that audience members consider this musical novelty as an important motivator for concert attendance. Live concerts also enable audience members to experience an in-person relationship with the performer. Performers can also be influenced by the presence of an audience, and live performances can be acoustically and energetically different than those recorded in the studio ( Zajonc, 1965 ; Yoshie et al., 2016 ; Bradby, 2017 ).

We used head movement responses as our main measure of audience experience for several reasons. Moving to the beat during music listening is culturally ubiquitous, with collective movement a hallmark of the contemporary concert experience ( Zatorre et al., 2007 ; Madison et al., 2011 ; Janata et al., 2012 ; Davies et al., 2013 ; Madison and Sioros, 2014 ; Stupacher et al., 2017 ). Individuals use a range of movements when listening to music, from foot tapping to head nodding, to whole body movement ( Leman and Godøy, 2010 ). Head movements are particularly relevant as they are a reliable indicator of rhythmic entrainment ( Toiviainen et al., 2010 ; Burger et al., 2013 ), reveal communication patterns between performers ( Chang et al., 2017 ), reveal directional and emotional communication patterns (Chang et al., unpublished), and even predict who will “match” during speed dating ( Chang et al., 2018b ). Movement of the head alone—but not legs alone—affects how ambiguous auditorily-presented rhythms are interpreted ( Phillips-Silver and Trainor, 2008 ). This interaction between head movement and auditory perception likely involves the vestibular system located in the inner ear which processes proprioceptive information about head movements ( Trainor et al., 2009 ). Head movements also encode emotional information ( Livingstone and Palmer, 2016 ; Chang et al., unpublished), and may function as a form of non-verbal communication in a noisy environment ( Harrigan et al., 2008 ). Head movements provide information about the nature of an emotion being communicated ( Ekman and Friesen, 1967 ; Witkower and Tracy, 2018 ). Furthermore, movement smoothness (which increases with movement speed) is greater when communicating joy than a neutral emotion or sadness ( Kang and Gross, 2016 ). Horizontal head movements and forward velocity communicate happiness even without the context provided by facial expression or vocal content ( Livingstone and Palmer, 2016 ). Additionally, movement vigour (average speed) and movement distance have been shown to convey the intensity of emotions ( Atkinson et al., 2004 ). Leow et al. (2015) found that, even when asked to walk at the same tempo, participants walked more vigorously (faster) to more familiar music. One study found that during music listening, greater head speed was correlated with increased spectral flux in low frequencies (associated with greater presence of kick drum and bass guitar) and in high frequencies (associated with hi-hat and cymbals or liveliness of a rhythm), as well as with greater percussiveness, but head speed was not found to be related to tempo ( Burger et al., 2013 ).

In summary, there are many possible factors contributing to movement during music listening including biological imperatives, emotions, and the presence of others. These factors have been studied in highly controlled laboratory settings but have yet to be explored in real-world music listening contexts. In the present study, we were interested in how a live concert affected audience head movements as an index of engagement, specifically, by comparing the movements of concertgoers who experienced a live performance versus a recorded version of the same songs. We were particularly interested in the measure of vigour. Following previous researchers, we operationally defined movement vigour as the average speed of movement over a time interval, regardless of direction (specifically, head distance travelled within a song divided by the total length of the song, giving a value in millimetres per second) ( Atkinson et al., 2004 ; Mazzoni et al., 2007 ; Zentner and Eerola, 2010 ). We were also interested in how head movements might be influenced by audience members’ prior admiration for the performers (i.e., their Listener-preference). People are motivated to attend music concerts when they hold a strong preference for the musicians’ work. Musical preferences for genres and artists also play a role in defining social affiliations, particularly during adolescence, where they appear to function as a ‘badge of identity’ within a social group ( North and Hargreaves, 1999 ; Mulder et al., 2010 ). ‘Fans’ of a particular performer would be expected to enjoy musical performances by that performer, in part because the familiarity gained from repeated exposure to recordings of their music would be expected to increase enjoyment of the performer’s music in general ( Schellenberg et al., 2008 ; van den Bosch et al., 2013 ). To examine the effect of audience members’ prior preferences for the band, we recruited fans of the performer Ian Fletcher Thornley, along with naïve listeners who expressed no particular preference for the performer. Since the album had not yet been released prior to the concerts, the effects of song familiarity were controlled while examining differences between fans and neutral listeners as neither group had heard the songs prior to the concerts.

In sum, we examined the effects of live versus pre-recorded music and fan status on audience engagement with the music through head movements. Self-reported Fans and Neutral-preference listeners were separately recruited, and randomly assigned to attend one of two concerts. The concerts served as the record release event for Canadian rock star Ian Fletcher Thornley’s 2015 solo album Secrets , featuring new unreleased music. In the Live concert, audience members experienced a live performance by the musicians, while in the Album-playback concert, listeners heard an audio recording of the same songs from the Secrets album. Both concerts were held in the LIVELab, a 106-seat performance hall equipped with a 25-camera optical motion capture system. Head movements of participants were recorded simultaneously throughout each of the two concerts (Supplementary Figure S1 ). Two aspects of head movement were examined: (1) vigour and (2) entrainment to the beat of the music. We hypothesised that head movements would be faster and better entrained when audiences experienced a live concert compared to a pre-recorded version of the music. We further hypothesised that fans of the performer would exhibit faster movement, and entrain better to the rhythm, compared to neutral listeners.

Materials and Methods

Participants.

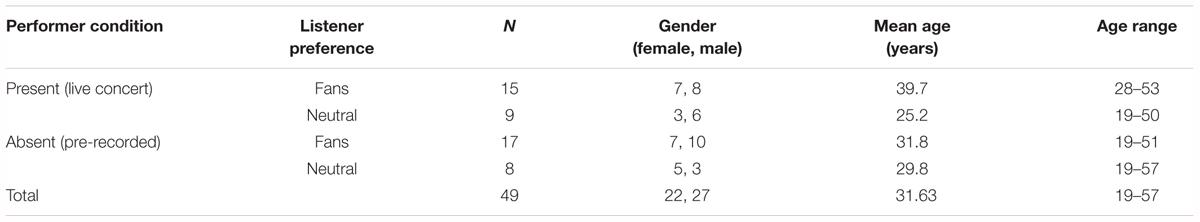

Fans of the performer were recruited through contests advertised in social media ( n = 39). Neutral-listeners who expressed no specific preference for Ian Fletcher Thornley ( n = 21) were recruited for course credit through McMaster University’s online research portal ( n = 3), social media and flyers circulated across campus and in music stores ( n = 18). Self-asserted Fan-status was verified via a follow-up questionnaire. Participants’ demographics and condition assignments are described in Table 1 . Prior to analysis, five participants were excluded due to: self-reported abnormal hearing ( n = 1 from Live/Neutral-listener condition), movement restrictions ( n = 1 from Album-playback/Fan condition), or having previously heard songs from the album ( n = 3; 1 from Album-playback/Fan, 2 from Live/Fan conditions). Six participants who did not respond to a follow-up survey confirming fan-status were further excluded: 1 from Album playback/Fan, 2 from Album-playback/Neutral-listener, 2 from Live/Fan, 1 from Live/Neutral-listener conditions. The final sample consisted of 32 Fans and 17 Neutral-listeners. The McMaster University Research Ethics Board approved all procedures.

Table 1. Participant demographics.

Stimuli and Apparatus

Ian Fletcher Thornley’s record release party concert was the setting for this study. Participants listened to eight songs from Thornley’s new studio album Secrets on the day of its official release. This release reached a top position of 9 on the Canadian iTunes sales charts on October 30th, 2015. The first seven songs were novel to all included participants. The final song in the concert, “Blown Wide Open,” was a cover version of a previous song that was familiar to fans 1 . The eight songs were presented in the following order in both conditions: (1) “Just to Know I Can”; (2) “How Long”; (3) “Fool”; (4) “Elouise”; (5) “Frozen Pond”; (6) “Feel”; (7) “Secrets”; and (8) reinterpretation of “Blown Wide Open”. These stimuli are hereafter referred to as Songs 1 through 8, respectively.

Both the Live and Album-playback concerts took place in the LIVELab 2 . The LIVELab is a research facility with a 106-seat performance hall designed for the study of human interaction in a variety of ecologically valid contexts, including music, dance and pedagogy. In both Live and Album-playback concerts, motion-recorded Fans and Neutral-listeners were seated interspersed in the front and centre of the audience across four rows with an average of 8 people per row. Sound for both concerts was presented over a high-quality Meyer Sound 6 channel house PA system (Left/Right Main Speakers, Meyer UPJ, Left/Right Front Fill, Meyer UP4, Left/Right Subwoofer, Meyer 500-HP). Reverberation was added to each instrument in the Live Concert via a Digico SD9 sound mixer. A sound technician manipulated volume and reverberation throughout the live concert as it would be at a professional live show. For the Live Concert condition, Thornley (vocals and electric guitar) and his band (electric bass, drums, and cigar box guitar) performed renditions of the 8 songs in the same order as they were presented in the Album-playback concert condition. Given that it was a live performance, there were minor variations in tempo and arrangement between the stimuli at the Live compared to Album-playback Concerts, as would be expected in any live performance of a recorded work (see Supplementary Table S1 in the Supplementary Material for a comparison of the tempi of the pre-recorded and live songs). Coloured stage lights helped create the concert experience. Videos depicting a variety of neuroscience-themed phenomena played behind the performers on the stage video wall (3 × 3 array of Mitsubishi LM55S 55″ monitors) during the Live concert. In song 6, “Feel,” a video depiction of a previous recording of Thornley’s neural responses when listening to the recording of his own song “Feel” were imaged from fMRI and EEG data. Referred to as “Lightning Brain,” the 5-min video can be viewed online 3 .

In the Album-playback concert, a photo of the Secrets album artwork was displayed on the stage video wall and the stage was dimly lit with coloured lights. The stage setup was identical for the two conditions; all of the instruments were in place and ready for performance. During Song 6 the video depiction of Thornley’s neural responses was displayed as in the Live concert. See Supplementary Table S1 for the tempi of the recorded and live songs.

Design and Procedure

The experimental design was a 2 × 2 × 7 with between-subjects factors Concert-status (Live, Album-playback) and Listener-preference (Fan, Neutral-listener) and within-subject factor Song (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7). The 8th song was analysed separately with only the between-subjects factors since it was familiar to Fans.

Fans and Neutral-listeners were randomly assigned to the Live or Album-playback conditions. In both cases participants were greeted at the entrance, filled out a consent form, and were fitted with a motion-capture cap. The caps did not restrict listener movement in any way. Participants were ushered into the theatre and to their seat. Once seated, additional audience members who did not participate in the study were then admitted to the theatre. Two researchers thanked the participants for their attendance and introduced the concert. Participants were instructed to do their best to forget that they were wearing caps and to enjoy the concert as they normally would. They were given no further instructions and were not encouraged to move in any particular way. Participants then completed a questionnaire on their familiarity with the performers, their current state of arousal and happiness, and their musical expertise (see Appendix S1 in Supplementary Material ). A follow-up questionnaire at the end of the concert asked the same questions regarding listener arousal and happiness.

Both concerts (Live, Album-playback) took place on the same day, with the Album-playback concert in the afternoon and the Live concert in the evening. During the Live concert, Thornley occasionally spoke to the audience between songs as performers would at a typical concert. Head movements between songs were not analysed. At the end of the Album-playback condition, Thornley and his band played a live song to avoid disappointing fans; head motion during this song was not analysed. A second questionnaire was sent to participants after the experiment to collect participant demographic information including age, sex, detailed music and dance experience and preferences.

Data Recording and Analysis

An audio recording of the live performance was recorded for later analysis. A passive optical motion capture system (24 Oqus 5+ cameras and an Oqus 210c video camera, Qualisys) recorded the head movements of participants at 90 Hz. Four retroreflective markers (10 mm) were placed on felt caps worn by the participants, forming a rigid body. One marker was placed on the front of the head, one on top of the head, and one on each temple.

Motion capture data were cleaned and labelled using the Qualisys Track Manager, then exported to MATLAB (The MathWorks Inc., 2015) for analysis with the motion capture toolbox ( Burger and Toiviainen, 2013 ). Motion data were gap-filled using linear interpolation, then low-pass filtered at 6 Hz to remove jitter. The positions of the four head markers were averaged to produce a single, stable representation of participant head centre (Supplementary Figure S1 ). Data were then normalised and segmented into songs. After preparation, two measures of participant head motion were generated.

Movement Vigour

The average movement speed of each participant in mm/s was calculated to provide a representation of movement vigour ( Mazzoni et al., 2007 ; Zentner and Eerola, 2010 ; Leow et al., 2014 ). The speed of participants’ movements was estimated by taking the first derivative of the motion signal (differences in position between adjacent frames). Speed trajectories were then smoothed using a second-order lowpass Butterworth filtre with a normalised low-pass frequency of 0.2π radians per sample. At a sampling frequency of 90 Hz, this equated to a 9 Hz low-pass filtre. Movement vigour is conceptually independent of synchronisation; a participant could remain in perfect synchrony to a given tempo and still move with more or less vigour (e.g., by increasing or decreasing the distance they moved their head), and a participant could also remain completely unsynchronised and still move with more or less vigour.

Degree of Entrainment

The degree of entrainment was defined as how frequently participants entrained their movements to the beat of each song. Movement periodicities were extracted with a windowed autocorrelation performed on listeners head-centre motion trajectories, with window size of 10 s, hop size of 5 s, and lags ranging from 0 to 2 s using mcwindow and mcperiod functions from the Mocap Toolbox ( Eerola et al., 2006 ; Burger and Toiviainen, 2013 ). The tempi of the songs from both the Live and Album-playback concerts were determined by two musically trained raters (first and third authors, n = 9 and n = 15 years of formal training, respectively) who tapped along to the beat of each song while listening to the recordings of the album and the Live concert using a metronome application (Metronome Beats, Stonekick©2015). The average inter-beat interval period was calculated from the song tempo, and this period was used to calculate the period at the quarter, half, and whole note levels of the musical metrical hierarchy for each song at which participants could have entrained. The participants’ head movement period at each window, obtained from the autocorrelation analysis, was compared to the three possible periods of each song. If the participant’s period of motion was within 5% of one of these beat periods, then that window was added to a count of the number of windows demonstrating entrainment. The measure of degree of entrainment was defined as the number of windows with entrainment divided by the total number of possible windows, to give the proportion of entrainment, which could range between 0.0 (no entrainment) and 1.0 (perfect entrainment). Actual measured proportions ranged from 0.0 to 0.58 depending on the participant and song. Our overall grand mean entrainment proportion of 0.081 was smaller, but of similar magnitude, to that found by Burger et al. (2014) who showed period-locking proportions less than 0.3 (summing tactus divisions and excluding inferior-superior movement, which our seated participants were not free to engage in). Smaller values would be expected in our case, given that for the Burger et al. (2014) experiment participants were standing and specifically asked to move to the music, whereas in the present study participants were seated and were not given any instructions regarding movement.

Analyses of the First Seven Unfamiliar Songs

Movement vigour and degree of entrainment were analysed with repeated measures ANOVAs, with between-subjects factors Concert-status (Live, Album-playback) and Listener-preference (Fan, Neutral-listener), and within-subjects factor Song (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7). When Mauchly’s test indicated that sphericity was violated, Greenhouse-Geisser’s corrections were applied. Effect sizes are reported with partial eta-squared values, means are accompanied by a variance measure of one standard error of the mean ( SEM ). Pairwise comparisons were adjusted using Bonferroni correction. Statistical tests were conducted in SPSS 2013 v20.0.0. Experiment-wise corrections were not implemented on the reported values, but below we note the two cases in which such a correction would affect interpretation of an effect as significant.

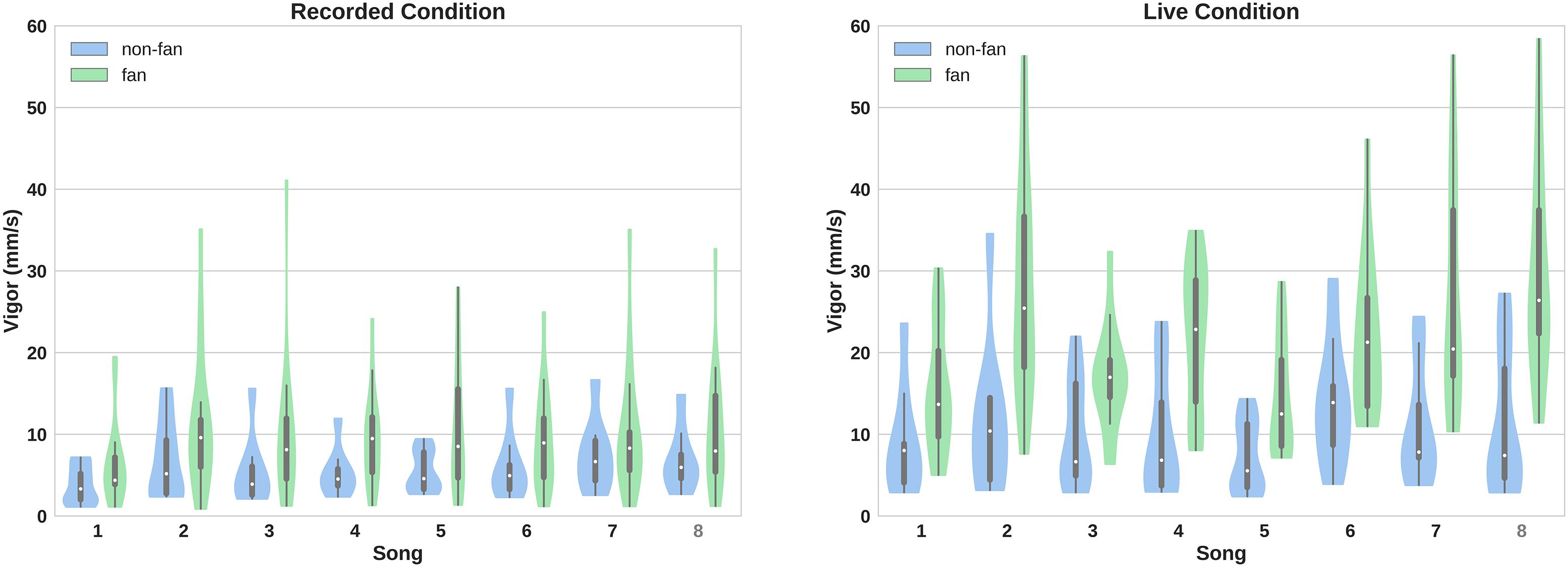

Concert-Status

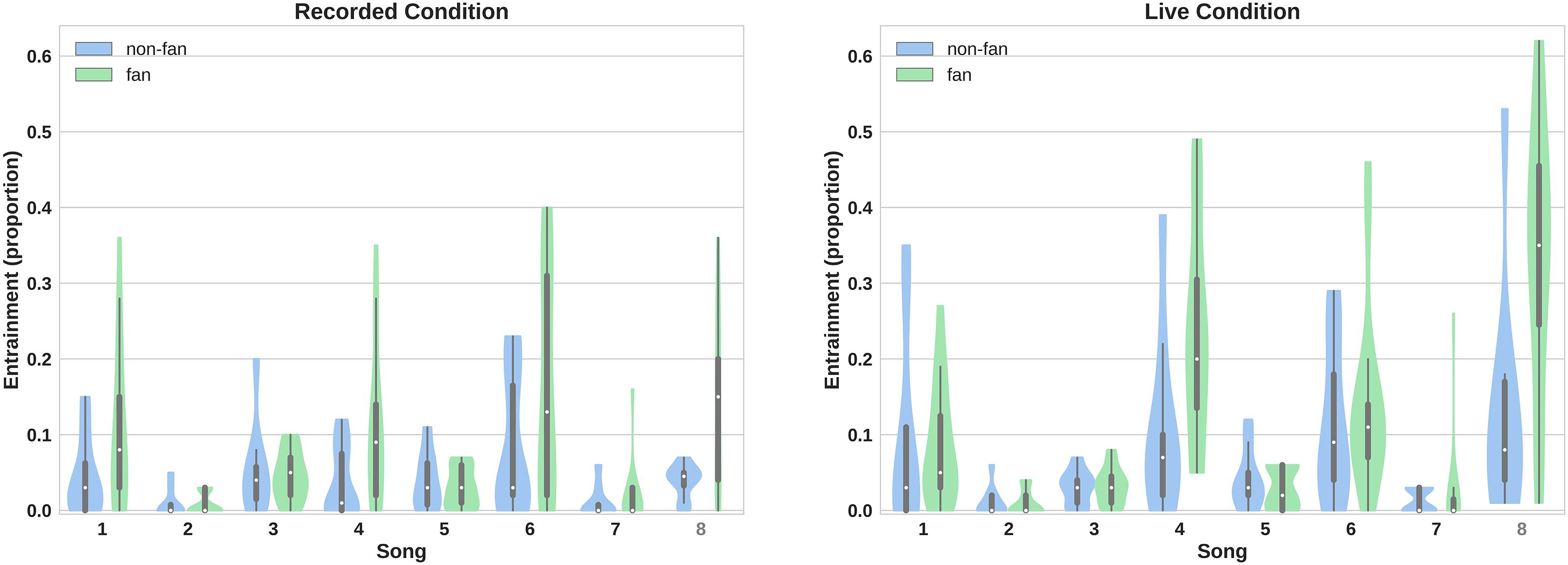

There was a main effect of Concert-status for vigour, but not for entrainment, F (1,45) = 15.783, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.260 and F (1,45) = 1.569, p = 0.217, η p 2 = 0.034, respectively. Participants moved more vigorously in the Live concert ( M = 15.559, SEM = 1.397) than the Album-playback concert ( M = 7.644, SEM = 1.421) condition. These results indicate that the Live concert increased vigour but not necessarily the degree of entrainment of head movements. The interaction between Concert-status and Listener-preference was not significant for either vigour or entrainment.

Listener-Preference

As predicted, there was a main effect of Listener-preference for both vigour and entrainment, F (1,45) = 12.871, p = 0.001, η p 2 = 0.222, and F (1,45) = 4.197, p = 0.046, η p 2 = 0.085, respectively. (Note that the effect of Listener-preference on entrainment is no longer significant if experiment-wise Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons is implemented). Fans ( M = 15.175, SEM = 1.174) moved faster than Neutral-listeners ( M = 8.027, SEM = 1.610) and Fans ( M = 0.074, SEM = 0.007) showed a higher degree of entrainment than Neutral-listeners ( M = 0.050, SEM = 0.01). These results indicate that Listener-preference affected both vigour and entrainment of head movements. The interaction between Concert-status and Listener-preference was not significant for either vigour or entrainment.

In addition to the main effects produced by the between-subjects variables, there was a main effect of Song for both vigour and entrainment, F (4.439,199.768) = 9.626, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.176 and F (3.254,146.414) = 19.022, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.297, respectively. This indicates substantial differences between songs in their ability to produce both fast and entrained movement, likely due to intrinsic properties of the songs, such as tempo (see Figures 1 , 2 ; song tempi are provided in Supplementary Table S1 in the Supplementary Material ). Interestingly, songs producing the fastest movement were not necessarily the same songs that produced maximal entrainment, indicating the possibility of some level of independence between these two measures. An acoustic analysis of the songs from both performances is underway as a separate paper in which we plan to relate head movements to characteristics such as Danceability, Energy, Instrumentalness, Liveness, and Valence of individual songs.

Figure 1. Vigour of head movements across songs. The distance travelled within a song was divided by the total length of the song, giving a value in millimetres per second. Fans moved with greater vigour than Neutral-listeners for every song and those in the Live Concert condition moved with greater vigour than those in the Album-playback Concert condition for every song. Vigour varied among songs, and was qualified depending on Concert-status (Live, Album-playback). The songs were: (1) “Just to Know I Can”; (2) “How Long”; (3) “Fool”; (4) “Elouise”; (5) “Frozen Pond”; (6) “Feel”; (7) “Secrets”; and (8) reinterpretation of “Blown Wide Open.” The violin plots show the same parameters as a standard box plot (range, interquartile range and median) as well as a kernel density plot that estimates the continuous distribution of the data.

Figure 2. Proportion of movement entrainment across songs. Fans generally showed a higher degree of entrainment to the tempo of the music than Neutral-listeners. However, there was variation among songs, which interacted with Concert-status. The songs were: (1) “Just to Know I Can”; (2) “How Long”; (3) “Fool”; (4) “Elouise”; (5) “Frozen Pond”; (6) “Feel”; (7) “Secrets”; and (8) reinterpretation of “Blown Wide Open.” The violin plots show the same parameters as a standard box plot (range, interquartile range and median) as well as a kernel density plot that estimates the continuous distribution of the data.

There was also an interaction between song and Listener-preference for both vigour and entrainment, F (4.439,199.768) = 2.428, p = 0.003, η p 2 = 0.082, and F (3.254,146.414) = 3.010, p = 0.029, η p 2 = 0.063, respectively. This interaction indicates that Fans and Neutral-listeners reacted differently to different songs (It should be noted that the interaction between song and Listener-preference on entrainment is no longer significant if experiment-wise Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons is implemented).

Analyses of the 8th Song

The final song (“Blown Wide Open,” released in 1997) was analysed separately because it was familiar to Thornley’s fans, having been one of the most famous songs from his previous band Big Wreck. This provides a preliminary exploration of how familiarity can promote movement.

There was a main effect of Concert-status on vigour, F (1,45) = 16.929, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.273. Movement was more vigorous in the Live concert ( M = 20.32 mm/s, SEM = 2.003) than Album-playback concert ( M = 8.56 mm/s, SEM = 2.037) condition. There was also a main effect on entrainment, F (1,45) = 11.917, p = 0.001, η p 2 = 0.209. The degree of entrainment was higher in the Live concert ( M = 0.235, SEM = 0.029) than Album-playback concert ( M = 0.091, SEM = 0.030) condition.

For Listener-preference, there was a main effect on vigour, F (1,45) = 14.494, p < 0.001, η p 2 = 0.244. Fans ( M = 19.88 mm/s, SEM = 1.683) moved faster than Neutral-listeners ( M = 9.00 mm/s, SEM = 2.308). There was also a main effect on entrainment, F (1,45) = 13.630, p = 0.001, η p 2 = 0.232. Fans ( M = 0.24, SEM = 0.025) entrained to a greater degree than Neutral-listeners ( M = 0.086, SEM = 0.034). The interaction between Concert-status and Listener-preference was not significant.

Musicians Versus Non-musicians

Using the self-reported measures of music experience, participants were categorised as musicians ( N = 25; mean years of training = 11.7; range = 1–38) or non-musicians with no musical training ( N = 24). Independent-samples t -tests were performed for vigour for the mean of Songs 1–7, t (47) = 0.6, p = 0.58, vigour for Song 8, t (47) = 0.4, p = 0.68, entrainment for the mean of Songs 1–7, t (47) = 0.5, p = 0.62, and entrainment for Song 8, t (47) = 0.8, p = 0.45. There were no significant differences on any of these measures.

The question of why people enjoy attending live concerts, when the same music can be experienced more easily and for less money at home, likely involves two aspects: the social sharing of the experience in a group of people; and “live” aspects, including connecting with the artists and experiencing the potential for spontaneity and unpredictability of live music as it unfolds over time, compared to a pre-recorded and unchanging version on a recording that a fan might become familiar with after repeated listening. In our study, we examined primarily the second aspect, comparing listening to a recording of a set of songs from Ian Fletcher Thornley’s 2015 album Secrets to listening to a live performance of those songs, while keeping the social aspect largely the same: both the Live and Album-playback concerts were experienced in the context of an audience in the same LIVELab venue. In the case of this study, audiences were not familiar with recorded songs, but nonetheless may have reacted to the knowledge that the music in the Live condition was unfolding in a unique way that would never be repeated exactly. Necessarily, the visual stimulation differed between the two conditions because of the presence of the live performers. We feel that this is not necessarily a confound—a live performance requires the presence of performers—but future studies might incorporate some visual stimulation that tries to better equate the two conditions, for example, by showing a video of the live performance. We also examined how being a fan of the musical group affected these experiences by comparing self-reported Fans and Neutral-listeners randomly assigned to the Live and Album-playback concert conditions. We focused on head movements, using motion capture to extract the vigour and degree of entrainment of head movements to the beat of music ( Toiviainen et al., 2010 ; Burger et al., 2013 ).

We found that for both Fans and Neutral-listeners, head movements were more vigorous in the Live than the Album-playback concert, but Concert-status did not affect degree of entrainment to the beat. On the other hand, across both concert conditions, Fans moved their heads more vigorously and with better entrainment to the beat compared to Neutral-listeners. The greater degree of entrainment to the beat in general in Fans likely reflects their greater familiarity with the artist’s musical style. The greater vigour of head movements across groups at the Live compared to Album-playback concert likely represents greater arousal, increased anticipation, and increased connection with the artists and their music during the live concert ( Mazzoni et al., 2007 ; Leow et al., 2014 ). Amount of musical training varied across audience members, but there were no differences between musicians and non-musicians in either movement vigour or synchronisation to the beat. Similarly, Bernardi et al. (2017) reported that musical training did not affect the degree of synchronisation of autonomic responses to the beat of music experienced in a group setting. Together, these results suggest that entrainment responses in audiences are independent of musical training.

We controlled for song familiarity across Fans and Neutral-listeners by using songs that had not yet been publicly released (the first 7 songs of the concerts). The eighth song, “Blown Wide Open,” on the other hand, was certainly familiar to Fans, and may have been familiar to some Neutral-listeners as its original rendition had achieved double platinum sales in Canada in the late 1990s. Interestingly, when the songs were not familiar, there was no difference in degree of entrainment to the music across the Live and Album-playback concerts. However, for the eighth song that was familiar at least to Fans, head movement entrainment was greater during the Live than Album-playback concert. This suggests that while the vigour of head movements is affected by whether the music is live or pre-recorded regardless of familiarity, familiarity with the music may foster greater entrainment to the beat during live compared to recorded contexts.

Vigour of head movements and degree of entrainment differed across songs. Further, there were interactions for both measures between Songs and Listener-preference, indicating that Fans and Neutral-listeners reacted differently to different songs. This suggests that some songs might excite existing fans differently than naïve listeners, which might inform record company promotion decisions. Concerts are becoming increasingly important for the music industry as the prevalence of piracy results in reduced revenue from album recordings ( Frith, 2007 ; Papies and van Heerde, 2017 ). Interestingly, the majority of audience members report that cost does not influence their decisions to attend concerts ( Brown and Knox, 2017 ). In general, research on audience development and retention could be important for sustaining the multi-billion dollar music industry ( O’Reilly et al., 2014 ; Papies and van Heerde, 2017 ).

Music compels us to move, the likely result of connections between auditory and motor areas of the brain ( Sakai et al., 1999 ; Janata and Grafton, 2003 ; Grahn and Brett, 2007 ; Zatorre et al., 2007 ; Grahn and Rowe, 2009 ; Janata et al., 2012 ), whose communication during rhythm and beat prediction can be measured in neural oscillations ( Fujioka et al., 2012 ). Certain characteristics of music lead to increased entrainment to music and compulsion of movement, such as beat predictability and rhythmic complexity ( Fitch, 2016 ), the density of events between beats ( Madison et al., 2011 ), moderate levels of syncopation ( Witek et al., 2014 ; Fitch, 2016 ), and possibly micro-timing deviations (cf. Madison et al., 2011 ; Davies et al., 2013 ; Stupacher et al., 2013 ; Kilchenmann and Senn, 2015 ). The present study demonstrates that in addition to acoustic characteristics of music, environmental and personal factors influence movement to music as well. Specifically, familiarity with the performer and musical style (Listener-preference) led to increased movement and entrainment, while the live performance (Concert-status) led to a significant increase in movement vigour. Because synchronous movement can lead to prosociality ( Hove and Risen, 2009 ; Wiltermuth and Heath, 2009 ; Valdesolo et al., 2010 ; Valdesolo and DeSteno, 2011 ; Launay et al., 2013 ; Cirelli et al., 2014b ; Trainor and Cirelli, 2015 ; Rennung and Goritz, 2016 ; Woolhouse et al., 2016 ), and because entrainment to music was fostered more by Listener-preference than Concert-status, it is possible that personal factors are more important than environmental factors for generating synchronous movement and subsequent prosociality.

This study adds to the fledgling literature examining music listening in concert settings ( Egermann et al., 2011 ; Shoda and Adachi, 2012 , 2015 , 2016 ; Fancourt and Williamon, 2016 ; Shoda et al., 2016 ). It provides unique insight into how live music is experienced in ecologically valid conditions, and how that experience is expressed through body movement. Many questions that remain could be addressed in future research in the LIVELab, such as how individual differences in personality affect live concert experiences, how individuals in a concert setting are affected by the movements of those around them, the effects of different musical characteristics (e.g., tempo, instrumentation, presence of improvisation, genre), whether synchronous movements in a concert setting leads to increased prosociality and bonding, and how performers are affected by audiences.

Data Availability

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available on https://zenodo.org/ (search for ‘LIVELab) by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Ethics Statement

This study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations of the Canadian Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (T), with written informed consent from all subjects. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the McMaster University Research Ethics Board.

Author Contributions

DS involved in data collection and analyses, and the preparation and review of the manuscript. DB involved in the research design, data collection and analyses, and the preparation and review of the manuscript. SL involved in motion data collection, statistical analyses, and review of the manuscript. JB involved in project and research design, recruitment, organisation, and data collection, and review of the manuscript. MW involved in the conception and organisation of the project including artist-Anthem coordination, research design, and review of the manuscript. SM-R involved in recruitment, data collection and review of the manuscript. LT involved in the conception and organisation of the project, research design, review of the statistical analyses, and preparation and review of the manuscript.

This research was funded by Anthem Records, a grant to LT from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (435-2016-1442), and a grant to MW from the Canadian Foundation for Innovation (30524).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments