- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

- Research Papers

How to Write a Medical Research Paper

Last Updated: February 5, 2024 Approved

This article was co-authored by Chris M. Matsko, MD . Dr. Chris M. Matsko is a retired physician based in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. With over 25 years of medical research experience, Dr. Matsko was awarded the Pittsburgh Cornell University Leadership Award for Excellence. He holds a BS in Nutritional Science from Cornell University and an MD from the Temple University School of Medicine in 2007. Dr. Matsko earned a Research Writing Certification from the American Medical Writers Association (AMWA) in 2016 and a Medical Writing & Editing Certification from the University of Chicago in 2017. wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. In this case, 89% of readers who voted found the article helpful, earning it our reader-approved status. This article has been viewed 201,325 times.

Writing a medical research paper is similar to writing other research papers in that you want to use reliable sources, write in a clear and organized style, and offer a strong argument for all conclusions you present. In some cases the research you discuss will be data you have actually collected to answer your research questions. Understanding proper formatting, citations, and style will help you write and informative and respected paper.

Researching Your Paper

- Pick something that really interests you to make the research more fun.

- Choose a topic that has unanswered questions and propose solutions.

- Quantitative studies consist of original research performed by the writer. These research papers will need to include sections like Hypothesis (or Research Question), Previous Findings, Method, Limitations, Results, Discussion, and Application.

- Synthesis papers review the research already published and analyze it. They find weaknesses and strengths in the research, apply it to a specific situation, and then indicate a direction for future research.

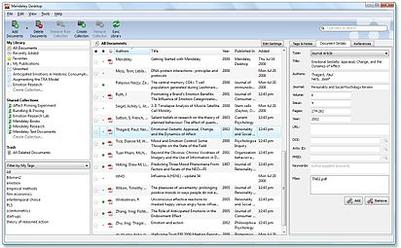

- Keep track of your sources. Write down all publication information necessary for citation: author, title of article, title of book or journal, publisher, edition, date published, volume number, issue number, page number, and anything else pertaining to your source. A program like Endnote can help you keep track of your sources.

- Take detailed notes as you read. Paraphrase information in your own words or if you copy directly from the article or book, indicate that these are direct quotes by using quotation marks to prevent plagiarism.

- Be sure to keep all of your notes with the correct source.

- Your professor and librarians can also help you find good resources.

- Keep all of your notes in a physical folder or in a digitized form on the computer.

- Start to form the basic outline of your paper using the notes you have collected.

Writing Your Paper

- Start with bullet points and then add in notes you've taken from references that support your ideas. [1] X Trustworthy Source PubMed Central Journal archive from the U.S. National Institutes of Health Go to source

- A common way to format research papers is to follow the IMRAD format. This dictates the structure of your paper in the following order: I ntroduction, M ethods, R esults, a nd D iscussion. [2] X Research source

- The outline is just the basic structure of your paper. Don't worry if you have to rearrange a few times to get it right.

- Ask others to look over your outline and get feedback on the organization.

- Know the audience you are writing for and adjust your style accordingly. [3] X Research source

- Use a standard font type and size, such as Times New Roman 12 point font.

- Double-space your paper.

- If necessary, create a cover page. Most schools require a cover page of some sort. Include your main title, running title (often a shortened version of your main title), author's name, course name, and semester.

- Break up information into sections and subsections and address one main point per section.

- Include any figures or data tables that support your main ideas.

- For a quantitative study, state the methods used to obtain results.

- Clearly state and summarize the main points of your research paper.

- Discuss how this research contributes to the field and why it is important. [4] X Research source

- Highlight potential applications of the theory if appropriate.

- Propose future directions that build upon the research you have presented. [5] X Research source

- Keep the introduction and discussion short, and spend more time explaining the methods and results.

- State why the problem is important to address.

- Discuss what is currently known and what is lacking in the field.

- State the objective of your paper.

- Keep the introduction short.

- Highlight the purpose of the paper and the main conclusions.

- State why your conclusions are important.

- Be concise in your summary of the paper.

- Show that you have a solid study design and a high-quality data set.

- Abstracts are usually one paragraph and between 250 – 500 words.

- Unless otherwise directed, use the American Medical Association (AMA) style guide to properly format citations.

- Add citations at end of a sentence to indicate that you are using someone else's idea. Use these throughout your research paper as needed. They include the author's last name, year of publication, and page number.

- Compile your reference list and add it to the end of your paper.

- Use a citation program if you have access to one to simplify the process.

- Continually revise your paper to make sure it is structured in a logical way.

- Proofread your paper for spelling and grammatical errors.

- Make sure you are following the proper formatting guidelines provided for the paper.

- Have others read your paper to proofread and check for clarity. Revise as needed.

Expert Q&A

- Ask your professor for help if you are stuck or confused about any part of your research paper. They are familiar with the style and structure of papers and can provide you with more resources. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Refer to your professor's specific guidelines. Some instructors modify parts of a research paper to better fit their assignment. Others may request supplementary details, such as a synopsis for your research project . Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Set aside blocks of time specifically for writing each day. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- Do not plagiarize. Plagiarism is using someone else's work, words, or ideas and presenting them as your own. It is important to cite all sources in your research paper, both through internal citations and on your reference page. Thanks Helpful 4 Not Helpful 2

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3178846/

- ↑ http://owl.excelsior.edu/research-and-citations/outlining/outlining-imrad/

- ↑ http://china.elsevier.com/ElsevierDNN/Portals/7/How%20to%20write%20a%20world-class%20paper.pdf

- ↑ http://intqhc.oxfordjournals.org/content/16/3/191

- ↑ http://www.ruf.rice.edu/~bioslabs/tools/report/reportform.html#form

About This Article

To write a medical research paper, research your topic thoroughly and compile your data. Next, organize your notes and create a strong outline that breaks up the information into sections and subsections, addressing one main point per section. Write the results and discussion sections first to go over your findings, then write the introduction to state your objective and provide background information. Finally, write the abstract, which concisely summarizes the article by highlighting the main points. For tips on formatting and using citations, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Joshua Benibo

Jun 5, 2018

Did this article help you?

Dominic Cipriano

Aug 16, 2016

Obiajulu Echedom

Apr 2, 2017

Noura Ammar Alhossiny

Feb 14, 2017

Dawn Daniel

Apr 20, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Medical Abstract for Publication

Preparing Your Study, Review, or Article for Publication in Medical Journals

The majority of social, behavioral, biological, and clinical journals follow the conventional structured abstract form with the following four major headings (or variations of these headings):

OBJECTIVE (Purpose; Aim; Goal) : Tells reader the purpose of your research and the questions it intends to answer

METHODS (Setting; Study Design; Participants) : Explains the methods and process so that other researchers can assess, review, and replicate your study.

RESULTS (Findings; Outcomes) : Summarizes the most important findings of your study

CONCLUSIONS (Discussion; Implications; Further Recommendations) : Summarizes the interpretation and implications of these results and presents recommendations for further research

Sample Health/Medical Abstract

Structured Abstracts Guidelines *

- Total Word Count: ~200-300 words (depending on the journal)

- Content: The abstract should reflect only the contents of the original paper (no cited work)

* Always follow the formatting guidelines of the journal to which you are submitting your paper.

Useful Terms and Phrases by Abstract Section

Objective: state your precise research purpose or question (1-2 sentences).

- Begin with “To”: “We aimed to…” or “The objective of this study was to…” using a verb that accurately captures the action of your study.

- Connect the verb to an object phrase to capture the central elements and purpose of the study, hypothesis , or research problem . Include details about the setting, demographics, and the problem or intervention you are investigating.

METHODS : Explain the tools and steps of your research (1-3 sentences)

- Use the past tense if the study has been conducted; use the present tense if the study is in progress.

- Include details about the study design, sample groups and sizes, variables, procedures, outcome measures, controls, and methods of analysis.

RESULTS : Summarize the data you obtained (3-6 sentences)

- Use the past tense when describing the actions or outcomes of the research.

- Include results that answer the research question and that were derived from the stated methods; examine data by qualitative or quantitative means.

- State whether the research question or hypothesis was proven or disproven.

CONCLUSIONS : Describe the key findings (2-5 sentences)

- Use the present tense to discuss the findings and implications of the study results.

- Explain the implications of these results for medicine, science, or society.

- Discuss any major limitations of the study and suggest further actions or research that should be undertaken.

Before submitting your abstract to medical journals, be sure to receive proofreading services from Wordvice, including journal manuscript editing and paper proofreading , to enhance your writing impact and fix any remaining errors.

Related Resources

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases for Top-Notch Essays (Oxford Royale Academy)

- 100+ Strong Verbs That Will Make Your Research Writing Amazing (Wordvice)

- Essential Academic Writing Words and Phrases (My English Teacher.eu)

- Academic Vocabulary, Useful Phrases for Academic Writing and Research Paper Writing (Research Gate)

- How to Compose a Journal Submission Cover Letter (Wordvice/YouTube)

- How to Write the Best Journal Submission Cover Letter (Wordvice)

Professional Medical Writing & Editing Services

The Ultimate Guide for Medical Manuscript Writing

Medical Manuscript writing can be overwhelming, but there are some tried-and-true techniques and creative tips that can dramatically simplify the process.

We mined the literature for strategies plus revealed some tricks from our seasoned writers to help you get your manuscript written and published.

In this document, we focused our attention on manuscripts since they are one of the most common types of medical writing . However, these are techniques that can be useful for any medical writing project.

What is good medical manuscript writing?

When you’re writing for a scientific audience it’s important to write with three C’s in mind:

- Clear: Don’t be ambiguous or leave anything to the imagination.

- Concise: Use brief, simple language and avoid repetition/redundancy.

- Correct: Be accurate, and don’t overstate the significance of your results.

Good medical writing is never more complicated than it needs to be.

Make it easy for your audience by keeping your language clear and simple.

How is medical writing different?

Many people want to know how writing healthcare blog topics is different from other types of writing. The answer is simple: it isn’t.

Good writing has a goal and a target audience and they will influence how you write, regardless of what you’re writing. A good manuscript is rooted in a good story.

Even data-driven medical texts can be delivered in an engaging way. Most of us can think of examples of stand-out papers in our field of expertise.

At their best these papers are entertaining and thought-provoking even while they deliver complicated, data-heavy material.

Make an Outline for your Manuscript

Before you start writing you need to have a clear understanding of the type and scope of your writing.

For example, consider exactly what you are writing. Is it a case study, textbook chapter , or literature review? These distinctions have important implications for how you craft and present your material.

An outline should be an obvious place to start, but you’d be surprised at how often this step is skipped.

How to structure your medial manuscript outline

When possible, before you start your outline you should understand the formatting requirements for your targeted publisher.

Many publishers specify abstract headings and have specific requirements for what can (and can’t) be included in the body of your text.

Use the outline as a way to narrow down the research you’ll need to do as you write.

It is an unfortunate fact of life: the abstract is often the only portion of a paper that ever gets read. For this reason, your abstract needs to convey the most important points from your paper in 300 words or less. Note what these points are in your abstract.

Make sure you know what your publisher expects from your abstract. Some journals limit you to 150 words or require that you arrange your abstract using specific headers.

You may need to include an objective or a statement of impact as well.

Most publishers ask authors to provide some keywords. Think about the keywords you’d use to search for your paper and write them down.

Keywords that are more general will increase the number of search results your paper will appear in. For example, use “spinal cord stimulation” instead of “neuromodulation.”

Define your goal

Is your goal to present new research data or to provide a meta-analysis of existing data? By clarifying the goal of your manuscript you can streamline preparation and writing.

Defining the goal is one of the secrets of successful grants and manuscripts of top biomedical PIs . Having a well-defined goal will also help you find the most appropriate publisher.

Keep your target audience in mind as you define your goal.

Introduction/background

The outline for your intro should note the current state of the field and identify knowledge gaps.

A good way to understand how to arrange your intro is by looking at similar papers that have been published by your target journal.

A standard approach to an intro can be broken down as follows:

- First paragraph: Current knowledge and foundational referencesYou’re paving the way for your readers to understand your objective

- Second paragraph: Introduce your specific topic and identify knowledge gaps

- Third paragraph: Clearly identify your aim

Key references and identifying your hypothesis and aim(s).

Methods Briefly list your methods and timeframe, but don’t get too detailed. This is just an outline.

Results The results section can be the most challenging to organize.

To simplify the writing process, state your overall question and create subsections for each dataset.

List the experiments you did and your results.

In your outline, identify data that should be presented in a figure or table. Save any subjective interpretations for the discussion section.

Discussion Your outline for the discussion should pick up where the introduction left off.

For example, if your intro ends with an aim, your discussion should start by restating your aim and reminding your readers of the knowledge gap(s) that you are addressing.

Your discussion needs to address each set of experiments and your interpretation, but don’t simply restate your results section.

Timeline Make a timeline for your manuscript and specify a submission date to help keep you on track.

Questions to consider when making your discussion outline include:

- How do your data relate to your original question?

- Do they support your hypothesis?

- Are your results consistent with what other researchers have found?

- If you had unexpected results, is there an explanation for them?

- Consider your data from the perspective of a competitor. Can you punch holes in your argument?

- Address potential concerns about your data head on. Don’t try to hide them or gloss over them.

- If you weren’t able to fully address your question(s) or aim(s), what else do you need to do?

- How do your data fit into the big picture?

Include a discussion subsection for each of your results subsections where you can subjectively interpret your data. Your outline should include the points you want to make in each subsection as well as your overall goal.

Conclude your discussion with a one sentence summary of your conclusion and its relevance to the field.

Again, don’t forget to write to your target audience!

Additional Resources for Medical Writing

Templates for Building a Perfect Writing Plan:

- Scope of work guide

- 30 Scope of work templates

- Medical cover letter + Templates

- Detailed guide of medical manuscript Scope of Work

- Short guide of scope of work for a medical journal

Know the Literature Before You Write Anything

An effective medical or scientific manuscript provides compelling information that builds on the existing literature and advances what is currently known.

This means you need to have a thorough understanding of the relevant literature!

Your goal is to collect all relevant references into a structured document. Make note of the aim and conclusion of each reference. Use this as a foundation to refer back to when you’re writing your paper.

Organize your research into buckets.

When you find a relevant source, ask yourself:

- Are the data consistent with what’s already known?

- If not: why are they different and how do they affect what’s known?

- Do your data support or refute the data presented in the source?

- You’ll need to explicitly address inconsistencies and identify potential resolutions.

Find Scholarly Sources

If you are writing an original research article , how do your data fit into the broader topic?

Google searches don’t usually produce scholarly resources unless you know where to look.

There are numerous FREE and Paid online resources available to find the right sources.

Top Scholarly Databases for journals, news, and articles

These tools can be used to find all the reputable sources needed to flesh out quality medical writing.

PubMed (MEDLINE):

PUBMED is an extremely popular and free search engine hosted by the NIH (National institutes of Health and U.S. National Library of Medicine. It can be used to access a vast index of peer-reviewed biological and medical research.

EMBASE is a database of literature intended to aid in organizational adherence to prescription drug regulations. Whereas it does contain some references that are not returned by PUBMED, there is a subscription fee associated with EMBASE.

Cochrane Library

The Cochrane Library is a curated database of medical research reviews, protocols, and editorials. While a subscription is required, the Cochrane is a critical resource for evidence-based medicine.

Web of Science

The Web of Science is another subscription service similar to those that have already been mentioned, albeit with an expanded range of academic disciplines including the arts, social sciences, and others.

Google Scholar

Google Scholar leverages Google’s powerful search engine to retrieve published literature from the whole internet (rather than just biomedical journals). This means you’ll get textbooks, theses, conference proceedings, and other publications that won’t show up in PubMed or EMBASE searches. Google Scholar is a powerful tool but it lacks the curation of other search tools, so a careful vetting of any information from this source is important.

Other databases:

Faculty of 1000 (F1000) offers Faculty Opinions and F1000Research. Faculty Opinions are links to recommended life-science articles, while F1000Research is a database of open-source research papers and results.

EBSCO is an online library providing a wide range of services, including its research databases that allow powerful searches of journals in a variety of academic disciplines.

iSEEK Education:

iSeek Education is a search engine geared specifically for academics. The resources from iSeek are meant to be dependable and from reliable sources, such as government agencies and universities.

RefSeek is another popular option for academically oriented search engines. RefSeek is designed to pull results from a large number of sources but not commercial links.

Virtual LRC:

The Virtual Learning Resources Center is a modified Google search of academic information websites. Its index of websites has been chosen by qualified curators.

More journal databases for medical research

- 100+ journal databases

- Top Academic Search Engines

- 101 Free Journal and Research Databases

- List of Global scholarly sources

Organize Your References:

One other point on knowing the literature: find a strategy that helps you keep references organized.

If you’ve ever written a paper and couldn’t remember where on earth you saw that one, perfect reference you know how important this is!

Rather than putting things into a long word document start with a research template.

RESOURCE: Use our FREE research template to collect sources for your manuscript

You can also download free basic software to organize references.

5 Reference Organization Tools and Software

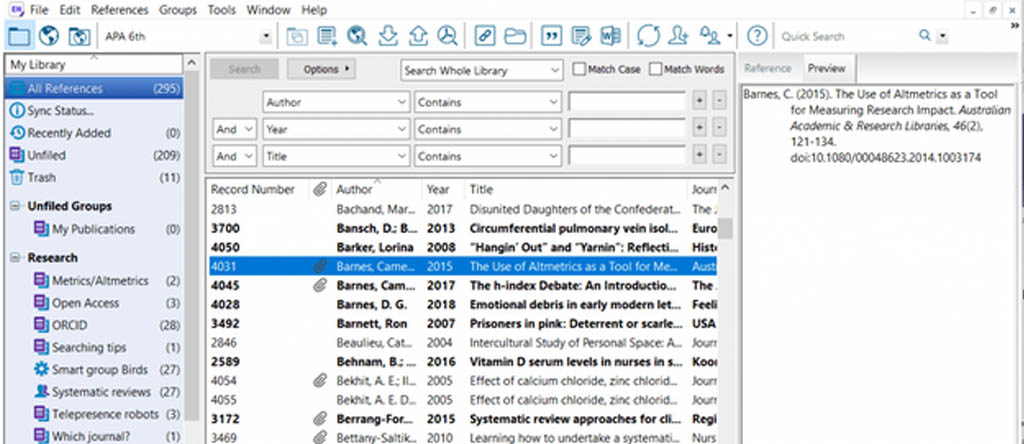

EndNote is the most popular reference organization tool for medical writers.

A basic version of EndNote is available for free, but paid subscriptions offer more options.

EndNote features include:

- Import, annotate, and search PDFs

- Ability to store reference libraries online, so you can access them from anywhere

- Collaboration is easy with shared libraries

- EndNote provides the most comprehensive citation style database, or you can create custom citation styles

- Easy to import/export references from databases using RIS, BibTex, and many other standard data schemes

One potential drawback of EndNote is that it’s not compatible with Linux.

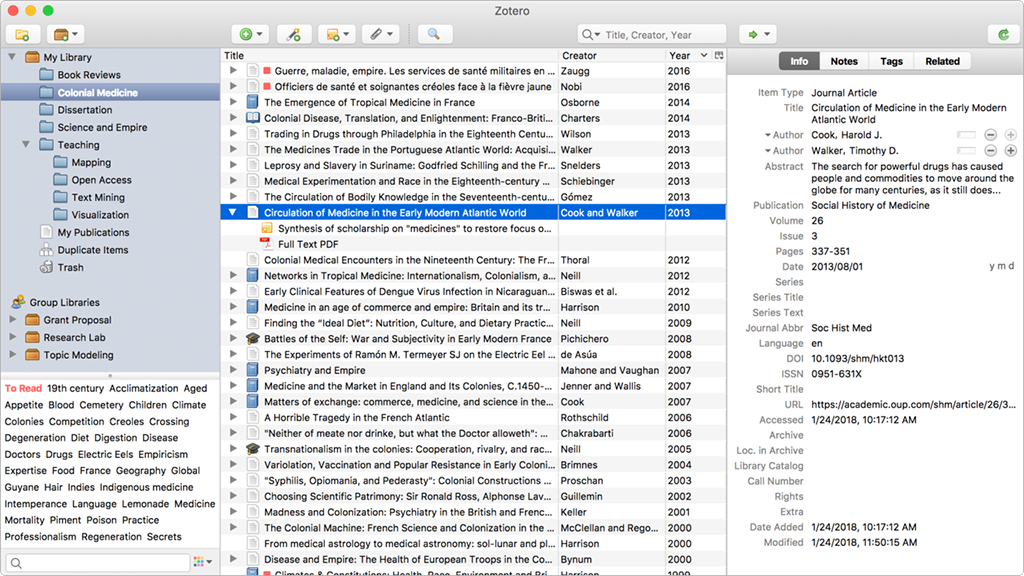

Zotero Zotero is a free, open-source reference management and citation tool.

Features of Zotero include:

- Save screenshots and annotate them within your citation library

- Import and export references in many formats, including RIS, BibTeX and BibLateX, EndNote, RefWorks, and more

- Supports over 30 languages

- Zotero’s online bibliography tool ZoteroBib lets you generate bibliographies without installing Zotero or creating an account

- Drag-and-drop interface

- Linux compatible

Mendeley Mendeley is Elsevier’s “freemium” referencing software, meaning the basic package is available for free but more sophisticated versions require a paid subscription.

Features of Mendeley include:

- Extract metadata from PDFs

- Create private, shareable libraries

A free online reference tool, Citefast allows users to quickly generate a library in APA 6 or 7, MLA 7 or 8, or Chicago styles.

Citefast doesn’t require you to make an account, but if you don’t create one your references will be lost after 4 days of inactivity.

Another free online resource, BibMe lets you import references and offers MLA, APA, Chicago, and Turabian formatting styles.

BibMe can also check your spelling and grammar, as well as look for plagiarism.

List of MORE Online Software Tools for Academic and Medical Research

30+ research tools to make your life easier

5 best tools for academic research

31 Best Online Tools for Research

10 great tools for online research

Know your audience

It’s important to know your audience before you start writing. This will help you define your goals and create an outline.

For example, if you’re preparing a case study for specialists your manuscript will be different than one for a multidisciplinary audience.

Ask yourself what your message is and find out how it aligns with the goals of your readers to maximize your paper’s impact.

Formatting requirements

Whenever possible, find out the formatting requirements you’ll need to follow before you start writing. They will explicitly state the layout, word limits, figure/table formatting, use of abbreviations, and which reference style to use.

If you’re writing for a journal their website will have a Guide for Authors that specifies formatting. If you’re not sure what the requirements are, you should contact the editor or publisher and ask them.

Types of medical manuscripts

Knowing what kind of manuscript you’re writing will help you organize your material and identify which information you should present. In addition, many publishers have different formatting requirements for different types of articles.

Although each publisher has their own guidelines for authors, many journals encourage authors to follow reporting guidelines from the EQUATOR Network (Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research).

Original research

The goal of an original research article is to convey your research findings to an audience. These articles typically follow the same structure:

- Introduction

Methods & Materials

Examples of great original medical research manuscripts:

- Nowacki J, Wingenfeld K, Kaczmarczyk M, et al. Steroid hormone secretion after stimulation of mineralocorticoid and NMDA receptors and cardiovascular risk in patients with depression . Transl Psychiatry . 2020 Apr 20;10(1):109.

- Pfitzer A, Maly C, Tappis H, et al. Characteristics of successful integrated family planning and maternal and child health services: Findings from a mixed-method, descriptive evaluation . F1000Res . 2019 Feb 28;8:229.

- Yi X, Liu M, Luo Q, et al. Toxic effects of dimethyl sulfoxide on red blood cells, platelets, and vascular endothelial cells in vitro . FEBS Open Bio . 2017 Feb 20;7(4):485-494.

- Karsan N, Goadsby PJ. Imaging the Premonitory Phase of Migraine . Front Neurol . 2020 Mar 25;11:140.

- Chan SS, Chappel AR, Maddox KEJ, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for preventing acquisition of HIV: A cross-sectional study of patients, prescribers, uptake, and spending in the United States, 2015-2016 . PLoS Med . 2020 Apr 10;17(4):e1003072.

Examples of great medical journal publications from The Med Writers :

Rapid communications

Rapid (or brief) communications are aimed at publishing highly impactful preliminary findings.

They are shorter than original research articles and focus on one specific result.

Many journals prioritize rapid communications, since they can provide paradigm-shifts in how we understand a particular topic.

5 Examples of Rapid Communications

- Rose D, Ashwood P. Plasma Interleukin-35 in Children with Autism . Brain Sci . 2019 Jun 27;9(7).

- Nash K, Johansson A, Yogeeswaran K. Social Media Approval Reduces Emotional Arousal for People High in Narcissism: Electrophysiological Evidence . Front Hum Neurosci . 2019 Sep 20;13:292.

- Su Q, Bouteau A, Cardenas J, et al. Long-term absence of Langerhans cells alters the gene expression profile of keratinocytes and dendritic epidermal T cells . PLoS One . 2020 Jan 10;15(1):e0223397.

- Nilsson I, Palmer J, Apostolou E, et al. Metabolic Dysfunction in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Not Due to Anti-mitochondrial Antibodies . Front Med . 2020 Mar 31;7:108.

- Rabiei S, Sedaghat F, Rastmanesh R. Is the hedonic hunger score associated with obesity in women? A brief communication . BMC Res Notes. 2019 Jun 10;12(1):330.

Case reports

Case reports detail interesting clinical cases that provide new insight into an area of research.

These are brief reports that chronicle a case, from initial presentation to prognosis (if known).

Importantly, when writing a case report, you need to clearly identify what makes your case unique and why it’s important. 5 Examples of Great Case Studies

- Scoles D, Ammar MJ, Carroll SE, et al. Cytomegalovirus retinitis in an immunocompetent host after complicated cataract surgery . Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep . 2020 Apr 6;18:100702.

- Yanagimoto Y, Ishizaki Y, Kaneko K. Iron deficiency anemia, stunted growth, and developmental delay due to avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder by restricted eating in autism spectrum disorder . Biopsychosoc Med . 2020 Apr 10;14:8.

- Pringle S, van der Vegt B, Wang X, et al. Lack of Conventional Acinar Cells in Parotid Salivary Gland of Patient Taking an Anti-PD-L1 Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor . Front Oncol . 2020 Apr 2;10:420.

- Crivelli P, Ledda RE, Carboni M, et al. Erdheim-Chester disease presenting with cough, abdominal pain, and headache . Radiol Case Rep . 2020 Apr 10;15(6):745-748.

- Tsai AL, Agustines D. The Coexistence of Oculocutaneous Albinism with Schizophrenia . Cureus . 2020 Jan 9;12(1):e6617.

Literature review

A good literature review provides a comprehensive overview of current literature in a new way. There are four basic types of literature review:

Traditional: Also known as narrative reviews, these reviews deliver a thorough synopsis of a body of literature. They may be used to highlight unanswered questions or knowledge gaps.

Li X, Geng M, Peng Y, Meng L, Lu S. Molecular immune pathogenesis and diagnosis of COVID-19 . J Pharm Anal . 2020 Mar 5.

Wardhan R, Kantamneni S. The Challenges of Ultrasound-guided Thoracic Paravertebral Blocks in Rib Fracture Patients . Cureus . 2020 Apr 10;12(4):e7626.

Lakhan, S.E., Vieira, K.F. Nutritional therapies for mental disorders . Nutr J 7, 2 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-7-2

A minireview is similar to a review, but confines itself to a specific subtopic:

Marra A, Viale G, Curigliano G. Recent advances in triple negative breast cancer: the immunotherapy era . BMC Med . 2019 May 9;17(1):90.

Systematic : These are rigorous, highly structured reviews that are often used to shed light on a specific research question. They are often combined with a meta-analysis or meta-synthesis.

Asadi-Pooya AA, Simani L. Central nervous system manifestations of COVID-19: A systematic review . J Neurol Sci . 2020 Apr 11;413:116832.

Katsanos K, Spiliopoulos S, Kitrou P, Krokidis M, Karnabatidis D. Risk of Death Following Application of Paclitaxel-Coated Balloons and Stents in the Femoropopliteal Artery of the Leg: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials . J Am Heart Assoc . 2018 Dec 18;7(24):e011245.

Meta-analysis: A meta-analysis analyzes data from multiple published studies using a standardized statistical approach. These reviews can help identify trends, patterns, and new conclusions.

Zhang J, Zhang X, Meng Y, Chen Y. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound for the differential diagnosis of thyroid nodules: An updated meta-analysis with comprehensive heterogeneity analysis . PLoS One . 2020 Apr 20;15(4):e0231775.

Meta-synthesis: A meta-synthesis is a qualitative (non-statistical) way to evaluate and analyze findings from several published studies.

Stuart R, Akther SF, Machin K, et al. Carers’ experiences of involuntary admission under mental health legislation: systematic review and qualitative meta-synthesis . BJPsych Open . 2020 Feb 11;6(2):e19.

At this point you’ve established three things for your manuscript:

- Your goal : Is your goal to convey the latest research? You should find a way to describe what you want to accomplish with this article.

- Your target audience : The most effective medical writing is done with a specific audience in mind.

- Type of manuscript : The type of article you’re writing will influence the format of the document you are writing.

You probably have a target journal or publisher in mind and you should have checked out their formatting requirements. Now it’s time to start writing!

Notably, many seasoned authors don’t write their articles from beginning to end. For example, if you’re preparing an original research manuscript they suggest writing the methods section first, followed by the results, discussion, introduction, and, lastly, the abstract. This will help you stay within the scope of the article.

Generally, the title for a medical document should be as succinct as possible while conveying the purpose of the article.

If you’re writing an original research article your title should convey your main finding as simply as possible.

Avoid using unnecessary jargon and ambiguity.

Some authors recommend including keywords that will help people find your writing in the title.

Your publisher may have a specific abstract format for you to follow. There are three general types of abstract:

- Indicative (descriptive) abstracts provide a clear overview of the topics covered. They are common in review articles and conference reports.

- Informative abstracts summarize the article based on structure (e.g. problem, methods, case studies/results, conclusions) but without headings.

- Structured abstracts use headings as specified by the publisher.

Good abstracts are clear, honest, brief, and specific. They also need to hook readers or your article will never be read (no pressure!).

Many publishers will ask you to come up with some keywords for your article. Make sure they’re specific and clearly represent the topic of your article.

If you’re not sure about your keywords the National Library of Medicine’s Medical Subject Headings ( MeSH ) website can help. Just type in a term and it will bring up associated subject headings and definitions.

Introduction

The goal of the introduction is to briefly provide context for your work and convince readers that it’s important. It is not a history lesson or a place to wax poetic about your love of medicine (unless you’re writing about history or your love of medicine). Everything in your introduction needs to be directly relevant to the overall goal of your manuscript.

Introductions vary in length and style between the different types of manuscript. The best way to understand what your publisher is looking for in an introduction is to read several examples from articles that are stylistically similar to yours.

Broadly speaking, an introduction needs to clearly identify the topic and the scope of the article. For an original research article this means you explicitly state the question you’re addressing and your proposed solution. For a literature review, the topic and its parameters should be stated.

Importantly, don’t mix the introduction with other sections. Methods and results don’t belong in the introduction.

Abbreviations

If you use terms that are abbreviated, some journals will ask you to include a section after the introduction where you define them. Consult the authors guide to learn how you should handle abbreviations. Also check to see if they have standard abbreviations that you don’t need to define in your manuscript.

A couple of tips for abbreviations:

· Terms that are only used once or twice should be spelled out, not abbreviated

· Don’t capitalize each word in an acronym unless it’s a proper noun (e.g. ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS), not Ubiquitin Proteasome System (UPS))

A good methods section will contain enough information that another researcher could reproduce the work. Clearly state your experimental design, what you did in chronological order, including equipment model numbers and specific settings you used. Make sure to include all equipment, materials, and products you used as they could account for future variability. Describe any statistical analyses.

The methods section should describe the following:

· Population and sampling methods

· Equipment and materials

· Procedures

· Time frame (if relevant)

· Analysis plan

· Approaches to ensure reliability/validity

· Any assumptions you used

· Scope and limitations

If you are using methods that have been described before you can refer to that publication or include them in your supplementary material, rather than re-writing them in the body of your text.

The results section is where your findings are objectively presented (save your interpretation of the results for the discussion section). Figure out which data are important for your story before you write the results section. For each important data set provide the results (preferably in a table or graph) and include a sentence or two that summarizes the results.

It’s easy to lose sight of the goal of the paper when you’re relaying numbers through the lens of statistics. Make sure to tie your results back to the biological aspects of your paper.

The discussion section is where you sell your interpretation of the data. Your discussion section needs to tie your introduction and your results sections together. A common strategy for the discussion section is to reiterate your main findings in light of the knowledge gaps you outlined in your introduction. How do your findings move the field forward?

Consider each of your results with respect to your original question and hypothesis. If there are multiple ways to interpret your data, discuss each of them. If your findings were not in line with your hypothesis, state this and provide possible explanations.

If your data are inconsistent with other published literature it’s important to consider technical and experimental differences before concluding that you’ve stumbled onto a groundbreaking medical discovery. Discuss all potential reasons for the divergent data.

Key points to include in your discussion section:

· What your results mean

· Whether your methods were successful

· How findings relate to other studies

· Limitations of your study

· How your work advances the field

· Applications

· Future directions

Don’t draw grand conclusions that aren’t supported by your data; some speculating is okay but don’t exaggerate the importance of your findings.

It’s important to remind your reader of your overall question and hypothesis throughout the discussion section, while you are providing your interpretation of the results. This will ensure that you stay on track while you’re writing and that your readers will understand exactly how your findings are relevant.

This is your final chance to convince your readers that your work is important.

Start your conclusion by restating your question and identify whether your findings support (or fail to support) your hypothesis.

Summarize your findings and discuss whether they agree with those of other researchers.

Finally, identify how your data advances the field and propose new or expanded ways of thinking about the question.

It’s important to avoid making unsupported claims or over-emphasize the impact of your findings. Even if you think your findings will revolutionize medicine as we know it, refrain from making that claim until you have the evidence to back it up.

Figures/Tables

Many readers will get the bulk of their information from your figures so make sure they are clear and informative. Your readers should be able to identify your key findings from figures alone.

Tips for figures and tables:

· Don’t repeat data in tables, figures and in the text

· Captions should sufficiently describe the figure so the reader could understand it even if the figure was absent

· Keep graphs simple! If a basic table will work there’s no need for a multi-colored graph

Acknowledgements

Use the acknowledgments section to identify people who made your manuscript possible. Include advisors, proofreaders, and financial backers. In addition, identify funding sources including grant or reference numbers.

Make sure to use the reference style specified by your target journal or publisher. Avoid too many references, redundant references, excessive self-referencing, and referencing for the sake of referencing. Personal communications, unpublished observations, and submitted, unaccepted manuscripts should generally be avoided.

It should go without saying that you need to be ethical when preparing medical manuscripts. Fabricating or falsifying data is never acceptable, and you put your career at risk. It’s not worth it.

Plagiarism is not a viable strategy for getting works published. Any indication that you’ve plagiarized will be investigated, and if you’re found to have plagiarized your career and scientific reputation are at stake. Any time you refer to published work you need to reference it, even if it was your own publication. Be very careful about self-plagiarizing!

To learn more about ethical writing take a look at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services guide: Avoiding Plagiarism, Self-plagiarism, and Other Questionable Writing Practices: A Guide to Ethical Writing , by Dr. Miguel Roig.

Ethics standards require that you submit your manuscript to only one publisher at a time. If you’re caught submitting to multiple editors none of them will publish your work.

Traps to avoid

Seasoned writers told us some of the pitfalls they’ve learned how to watch out for:

Writing versus editing

Writing and editing are not the same. Get comfortable writing , that is, pouring out all of your ideas without editing yourself. Then go back and edit.

Lack of editing

One of the toughest parts of writing is opening yourself up to critique. As hard as it can be, the best way to get a polished and meaningful manuscript is to have other people read it. As writers we can get attached to particular phrases or styles that may not read as well to other people.

Scientific manuscript editing is the toughest of any manuscript editing but if you keep patience and edit honestly it will get easier over time. Imagine that you’re editing someone else’s document to help give you fresh eyes. If possible give yourself a couple of days without looking at the manuscript, then go back and read it.

Being unfamiliar with the literature

It’s important to be familiar with the current literature on the topic you’re writing about. A fatal flaw of any research manuscript is proposing a hypothesis that has already been tested or posing questions that have already been answered.

Not formatting properly

If your manuscript is not formatted properly, it is less likely to be accepted. Make sure your font and line spacing are correct, that you’ve adhered to word and figure limits, and that your references are in the correct style.

Useful tips

Here are some helpful tips that you can use to improve your writing:

Framing your manuscript

A common trope in outlining manuscripts is the inverted triangle approach, which starts generally and ends specifically. A more useful method is to consider an hourglass-shaped outline, which starts generally, specifically addresses your contribution to the field, then ties your contribution back to current knowledge and unanswered questions.

Passive and active voice

Medical writing has long used passive voice to communicate and, while this is still the status quo for many journals, don’t be afraid to get out of that mire. As journals begin to recognize that active voice is not only more economical but can also be more readable they are becoming more comfortable publishing articles that include active voice.

Don’t edit while you write

Get a first draft onto paper as quickly as possible and then edit. Don’t waste time trying to get a paragraph perfect the first time you write it.

Ask someone else to edit

Medical writing does have some unique challenges associated with it. Your audience may not be experts on the material you are delivering, so an ability to communicate complicated information in an accessible manner is very helpful. Improve on your skills by asking people outside of your field to provide constructive criticism on writing samples.

It can be a very useful practice to edit some manuscripts that other people have written. This will help you understand what editors are paying attention to.

Keep track of references

Make sure to keep detailed notes of where you got your references so that you can easily and accurately cite the literature you used. There’s nothing more frustrating than not being able to remember where you saw a really great reference.

Before you submit your manuscript

Ideally, you’ve left yourself plenty of time to proofread and have other people edit your document. At the very least make sure you budget some hours to carefully proofread. Triple check that your paper adheres to formatting requirements. You can learn how to proofread scientific manuscripts before submitting them for publication.

Cover letters

If you’re submitting an article for consideration you’ll need to write a cover letter. Take the time to find out who the editor is and address your letter to him or her. This is your chance to communicate with the editor! A generic “To whom it may concern” won’t impress anyone.

Your cover letter should be brief, but it needs to convey the value of your paper to the journal. Describe your main findings and their significance and why they’re a great fit for your publication of interest.

If you have conflicts of interest, disclose them in your cover letter. Also, if your paper has already been rejected, let them know. Include the reason (if known) and reviewer comments, as well as discussing changes you’ve made to improve the paper.

You can also suggest peer-reviewers or people who shouldn’t review your paper. Be cautious when suggesting reviewers! Some of the most critical reviews come from suggested reviewers.

Your cover letter is an excellent opportunity to prove that you know what the goals of the journal are and that your article furthers them. Don’t waste it!

Reviewer comments/Revisions

If the publisher asks you to address reviewer comments, take the time to do this seriously and thoughtfully. Understand reviewer comments and address them objectively and scientifically (be polite!). If you disagree with a comment, state why and include supporting references. When more experiments or computations are requested, do them. It will make your paper stronger.

When you resubmit your manuscript make sure to identify page/line numbers where changes were made.

What if you’re rejected?

Don’t despair! Rejection happens to every writer. Try to understand why your manuscript was rejected. Evaluate your manuscript honestly and take the opportunity to learn from your mistakes.

A rejected paper isn’t a dead paper. You’ll need to make some substantial revisions and may need to change your formatting before resubmitting to a new journal or publisher. In the cover letter to the new editor you’ll need to state that your manuscript was rejected. Include any information you got about why your manuscript was rejected and all reviewer comments. Identify changes you made to the paper and explain why you chose to submit to the new journal.

Medical writing can be very rewarding but it’s important that writers have a clear understanding of what publishers are looking for. High-quality, original works that advance the medical field are much more likely to be published than papers that are not original or that have little medical or scientific interest.

Quality medical writing should have clarity, economy of language, and a consistent theme. It’s important to always state the question or topic you’re addressing early and refer to it often. This will help you stay focused and within the scope of your article during the writing process and it will help your readers understand your intentions. Using an outline is a very helpful way to make sure your article is consistently on-topic.

Following the tips and techniques provided here will definitely improve your writing skills, but the most effective way to get better at medical writing is to do it. There is no single best way to prepare a medical manuscript and even professional writers are continuously tweaking their writing strategies.

Hopefully these tips have helped you create a great manuscript. If you’re feeling overwhelmed and want some help with your medical writing or editing, we at The Med Writers can help. Contact us to learn more about our writing and editing services.

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Healthcare Writing

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

Subsections

- Open access

- Published: 07 September 2020

A tutorial on methodological studies: the what, when, how and why

- Lawrence Mbuagbaw ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5855-5461 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Daeria O. Lawson 1 ,

- Livia Puljak 4 ,

- David B. Allison 5 &

- Lehana Thabane 1 , 2 , 6 , 7 , 8

BMC Medical Research Methodology volume 20 , Article number: 226 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

36k Accesses

52 Citations

58 Altmetric

Metrics details

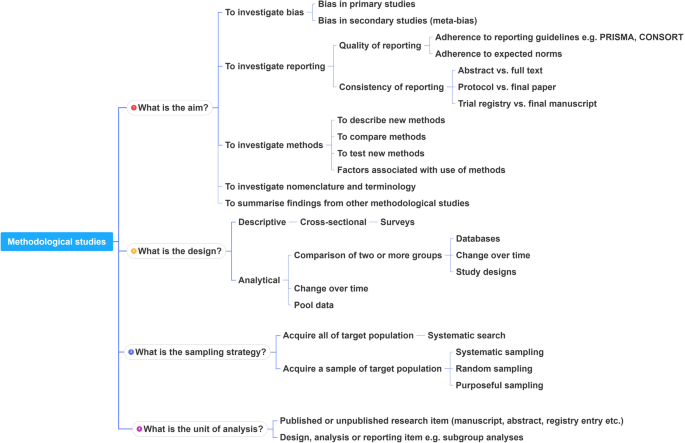

Methodological studies – studies that evaluate the design, analysis or reporting of other research-related reports – play an important role in health research. They help to highlight issues in the conduct of research with the aim of improving health research methodology, and ultimately reducing research waste.

We provide an overview of some of the key aspects of methodological studies such as what they are, and when, how and why they are done. We adopt a “frequently asked questions” format to facilitate reading this paper and provide multiple examples to help guide researchers interested in conducting methodological studies. Some of the topics addressed include: is it necessary to publish a study protocol? How to select relevant research reports and databases for a methodological study? What approaches to data extraction and statistical analysis should be considered when conducting a methodological study? What are potential threats to validity and is there a way to appraise the quality of methodological studies?

Appropriate reflection and application of basic principles of epidemiology and biostatistics are required in the design and analysis of methodological studies. This paper provides an introduction for further discussion about the conduct of methodological studies.

Peer Review reports

The field of meta-research (or research-on-research) has proliferated in recent years in response to issues with research quality and conduct [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. As the name suggests, this field targets issues with research design, conduct, analysis and reporting. Various types of research reports are often examined as the unit of analysis in these studies (e.g. abstracts, full manuscripts, trial registry entries). Like many other novel fields of research, meta-research has seen a proliferation of use before the development of reporting guidance. For example, this was the case with randomized trials for which risk of bias tools and reporting guidelines were only developed much later – after many trials had been published and noted to have limitations [ 4 , 5 ]; and for systematic reviews as well [ 6 , 7 , 8 ]. However, in the absence of formal guidance, studies that report on research differ substantially in how they are named, conducted and reported [ 9 , 10 ]. This creates challenges in identifying, summarizing and comparing them. In this tutorial paper, we will use the term methodological study to refer to any study that reports on the design, conduct, analysis or reporting of primary or secondary research-related reports (such as trial registry entries and conference abstracts).

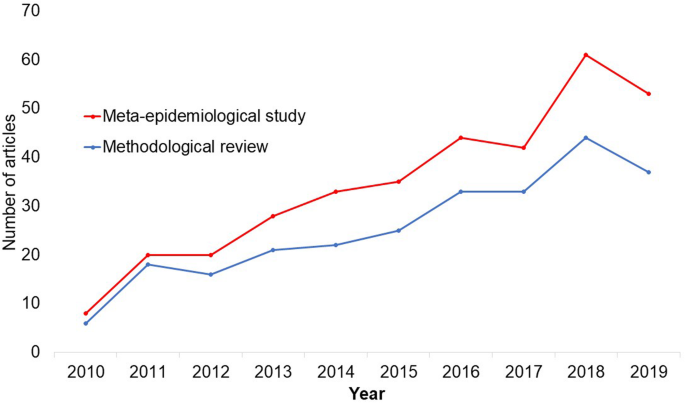

In the past 10 years, there has been an increase in the use of terms related to methodological studies (based on records retrieved with a keyword search [in the title and abstract] for “methodological review” and “meta-epidemiological study” in PubMed up to December 2019), suggesting that these studies may be appearing more frequently in the literature. See Fig. 1 .

Trends in the number studies that mention “methodological review” or “meta-

epidemiological study” in PubMed.

The methods used in many methodological studies have been borrowed from systematic and scoping reviews. This practice has influenced the direction of the field, with many methodological studies including searches of electronic databases, screening of records, duplicate data extraction and assessments of risk of bias in the included studies. However, the research questions posed in methodological studies do not always require the approaches listed above, and guidance is needed on when and how to apply these methods to a methodological study. Even though methodological studies can be conducted on qualitative or mixed methods research, this paper focuses on and draws examples exclusively from quantitative research.

The objectives of this paper are to provide some insights on how to conduct methodological studies so that there is greater consistency between the research questions posed, and the design, analysis and reporting of findings. We provide multiple examples to illustrate concepts and a proposed framework for categorizing methodological studies in quantitative research.

What is a methodological study?

Any study that describes or analyzes methods (design, conduct, analysis or reporting) in published (or unpublished) literature is a methodological study. Consequently, the scope of methodological studies is quite extensive and includes, but is not limited to, topics as diverse as: research question formulation [ 11 ]; adherence to reporting guidelines [ 12 , 13 , 14 ] and consistency in reporting [ 15 ]; approaches to study analysis [ 16 ]; investigating the credibility of analyses [ 17 ]; and studies that synthesize these methodological studies [ 18 ]. While the nomenclature of methodological studies is not uniform, the intents and purposes of these studies remain fairly consistent – to describe or analyze methods in primary or secondary studies. As such, methodological studies may also be classified as a subtype of observational studies.

Parallel to this are experimental studies that compare different methods. Even though they play an important role in informing optimal research methods, experimental methodological studies are beyond the scope of this paper. Examples of such studies include the randomized trials by Buscemi et al., comparing single data extraction to double data extraction [ 19 ], and Carrasco-Labra et al., comparing approaches to presenting findings in Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) summary of findings tables [ 20 ]. In these studies, the unit of analysis is the person or groups of individuals applying the methods. We also direct readers to the Studies Within a Trial (SWAT) and Studies Within a Review (SWAR) programme operated through the Hub for Trials Methodology Research, for further reading as a potential useful resource for these types of experimental studies [ 21 ]. Lastly, this paper is not meant to inform the conduct of research using computational simulation and mathematical modeling for which some guidance already exists [ 22 ], or studies on the development of methods using consensus-based approaches.

When should we conduct a methodological study?

Methodological studies occupy a unique niche in health research that allows them to inform methodological advances. Methodological studies should also be conducted as pre-cursors to reporting guideline development, as they provide an opportunity to understand current practices, and help to identify the need for guidance and gaps in methodological or reporting quality. For example, the development of the popular Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were preceded by methodological studies identifying poor reporting practices [ 23 , 24 ]. In these instances, after the reporting guidelines are published, methodological studies can also be used to monitor uptake of the guidelines.

These studies can also be conducted to inform the state of the art for design, analysis and reporting practices across different types of health research fields, with the aim of improving research practices, and preventing or reducing research waste. For example, Samaan et al. conducted a scoping review of adherence to different reporting guidelines in health care literature [ 18 ]. Methodological studies can also be used to determine the factors associated with reporting practices. For example, Abbade et al. investigated journal characteristics associated with the use of the Participants, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome, Timeframe (PICOT) format in framing research questions in trials of venous ulcer disease [ 11 ].

How often are methodological studies conducted?

There is no clear answer to this question. Based on a search of PubMed, the use of related terms (“methodological review” and “meta-epidemiological study”) – and therefore, the number of methodological studies – is on the rise. However, many other terms are used to describe methodological studies. There are also many studies that explore design, conduct, analysis or reporting of research reports, but that do not use any specific terms to describe or label their study design in terms of “methodology”. This diversity in nomenclature makes a census of methodological studies elusive. Appropriate terminology and key words for methodological studies are needed to facilitate improved accessibility for end-users.

Why do we conduct methodological studies?

Methodological studies provide information on the design, conduct, analysis or reporting of primary and secondary research and can be used to appraise quality, quantity, completeness, accuracy and consistency of health research. These issues can be explored in specific fields, journals, databases, geographical regions and time periods. For example, Areia et al. explored the quality of reporting of endoscopic diagnostic studies in gastroenterology [ 25 ]; Knol et al. investigated the reporting of p -values in baseline tables in randomized trial published in high impact journals [ 26 ]; Chen et al. describe adherence to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement in Chinese Journals [ 27 ]; and Hopewell et al. describe the effect of editors’ implementation of CONSORT guidelines on reporting of abstracts over time [ 28 ]. Methodological studies provide useful information to researchers, clinicians, editors, publishers and users of health literature. As a result, these studies have been at the cornerstone of important methodological developments in the past two decades and have informed the development of many health research guidelines including the highly cited CONSORT statement [ 5 ].

Where can we find methodological studies?

Methodological studies can be found in most common biomedical bibliographic databases (e.g. Embase, MEDLINE, PubMed, Web of Science). However, the biggest caveat is that methodological studies are hard to identify in the literature due to the wide variety of names used and the lack of comprehensive databases dedicated to them. A handful can be found in the Cochrane Library as “Cochrane Methodology Reviews”, but these studies only cover methodological issues related to systematic reviews. Previous attempts to catalogue all empirical studies of methods used in reviews were abandoned 10 years ago [ 29 ]. In other databases, a variety of search terms may be applied with different levels of sensitivity and specificity.

Some frequently asked questions about methodological studies

In this section, we have outlined responses to questions that might help inform the conduct of methodological studies.

Q: How should I select research reports for my methodological study?

A: Selection of research reports for a methodological study depends on the research question and eligibility criteria. Once a clear research question is set and the nature of literature one desires to review is known, one can then begin the selection process. Selection may begin with a broad search, especially if the eligibility criteria are not apparent. For example, a methodological study of Cochrane Reviews of HIV would not require a complex search as all eligible studies can easily be retrieved from the Cochrane Library after checking a few boxes [ 30 ]. On the other hand, a methodological study of subgroup analyses in trials of gastrointestinal oncology would require a search to find such trials, and further screening to identify trials that conducted a subgroup analysis [ 31 ].

The strategies used for identifying participants in observational studies can apply here. One may use a systematic search to identify all eligible studies. If the number of eligible studies is unmanageable, a random sample of articles can be expected to provide comparable results if it is sufficiently large [ 32 ]. For example, Wilson et al. used a random sample of trials from the Cochrane Stroke Group’s Trial Register to investigate completeness of reporting [ 33 ]. It is possible that a simple random sample would lead to underrepresentation of units (i.e. research reports) that are smaller in number. This is relevant if the investigators wish to compare multiple groups but have too few units in one group. In this case a stratified sample would help to create equal groups. For example, in a methodological study comparing Cochrane and non-Cochrane reviews, Kahale et al. drew random samples from both groups [ 34 ]. Alternatively, systematic or purposeful sampling strategies can be used and we encourage researchers to justify their selected approaches based on the study objective.

Q: How many databases should I search?

A: The number of databases one should search would depend on the approach to sampling, which can include targeting the entire “population” of interest or a sample of that population. If you are interested in including the entire target population for your research question, or drawing a random or systematic sample from it, then a comprehensive and exhaustive search for relevant articles is required. In this case, we recommend using systematic approaches for searching electronic databases (i.e. at least 2 databases with a replicable and time stamped search strategy). The results of your search will constitute a sampling frame from which eligible studies can be drawn.

Alternatively, if your approach to sampling is purposeful, then we recommend targeting the database(s) or data sources (e.g. journals, registries) that include the information you need. For example, if you are conducting a methodological study of high impact journals in plastic surgery and they are all indexed in PubMed, you likely do not need to search any other databases. You may also have a comprehensive list of all journals of interest and can approach your search using the journal names in your database search (or by accessing the journal archives directly from the journal’s website). Even though one could also search journals’ web pages directly, using a database such as PubMed has multiple advantages, such as the use of filters, so the search can be narrowed down to a certain period, or study types of interest. Furthermore, individual journals’ web sites may have different search functionalities, which do not necessarily yield a consistent output.

Q: Should I publish a protocol for my methodological study?

A: A protocol is a description of intended research methods. Currently, only protocols for clinical trials require registration [ 35 ]. Protocols for systematic reviews are encouraged but no formal recommendation exists. The scientific community welcomes the publication of protocols because they help protect against selective outcome reporting, the use of post hoc methodologies to embellish results, and to help avoid duplication of efforts [ 36 ]. While the latter two risks exist in methodological research, the negative consequences may be substantially less than for clinical outcomes. In a sample of 31 methodological studies, 7 (22.6%) referenced a published protocol [ 9 ]. In the Cochrane Library, there are 15 protocols for methodological reviews (21 July 2020). This suggests that publishing protocols for methodological studies is not uncommon.

Authors can consider publishing their study protocol in a scholarly journal as a manuscript. Advantages of such publication include obtaining peer-review feedback about the planned study, and easy retrieval by searching databases such as PubMed. The disadvantages in trying to publish protocols includes delays associated with manuscript handling and peer review, as well as costs, as few journals publish study protocols, and those journals mostly charge article-processing fees [ 37 ]. Authors who would like to make their protocol publicly available without publishing it in scholarly journals, could deposit their study protocols in publicly available repositories, such as the Open Science Framework ( https://osf.io/ ).

Q: How to appraise the quality of a methodological study?

A: To date, there is no published tool for appraising the risk of bias in a methodological study, but in principle, a methodological study could be considered as a type of observational study. Therefore, during conduct or appraisal, care should be taken to avoid the biases common in observational studies [ 38 ]. These biases include selection bias, comparability of groups, and ascertainment of exposure or outcome. In other words, to generate a representative sample, a comprehensive reproducible search may be necessary to build a sampling frame. Additionally, random sampling may be necessary to ensure that all the included research reports have the same probability of being selected, and the screening and selection processes should be transparent and reproducible. To ensure that the groups compared are similar in all characteristics, matching, random sampling or stratified sampling can be used. Statistical adjustments for between-group differences can also be applied at the analysis stage. Finally, duplicate data extraction can reduce errors in assessment of exposures or outcomes.

Q: Should I justify a sample size?

A: In all instances where one is not using the target population (i.e. the group to which inferences from the research report are directed) [ 39 ], a sample size justification is good practice. The sample size justification may take the form of a description of what is expected to be achieved with the number of articles selected, or a formal sample size estimation that outlines the number of articles required to answer the research question with a certain precision and power. Sample size justifications in methodological studies are reasonable in the following instances:

Comparing two groups

Determining a proportion, mean or another quantifier

Determining factors associated with an outcome using regression-based analyses

For example, El Dib et al. computed a sample size requirement for a methodological study of diagnostic strategies in randomized trials, based on a confidence interval approach [ 40 ].

Q: What should I call my study?

A: Other terms which have been used to describe/label methodological studies include “ methodological review ”, “methodological survey” , “meta-epidemiological study” , “systematic review” , “systematic survey”, “meta-research”, “research-on-research” and many others. We recommend that the study nomenclature be clear, unambiguous, informative and allow for appropriate indexing. Methodological study nomenclature that should be avoided includes “ systematic review” – as this will likely be confused with a systematic review of a clinical question. “ Systematic survey” may also lead to confusion about whether the survey was systematic (i.e. using a preplanned methodology) or a survey using “ systematic” sampling (i.e. a sampling approach using specific intervals to determine who is selected) [ 32 ]. Any of the above meanings of the words “ systematic” may be true for methodological studies and could be potentially misleading. “ Meta-epidemiological study” is ideal for indexing, but not very informative as it describes an entire field. The term “ review ” may point towards an appraisal or “review” of the design, conduct, analysis or reporting (or methodological components) of the targeted research reports, yet it has also been used to describe narrative reviews [ 41 , 42 ]. The term “ survey ” is also in line with the approaches used in many methodological studies [ 9 ], and would be indicative of the sampling procedures of this study design. However, in the absence of guidelines on nomenclature, the term “ methodological study ” is broad enough to capture most of the scenarios of such studies.

Q: Should I account for clustering in my methodological study?

A: Data from methodological studies are often clustered. For example, articles coming from a specific source may have different reporting standards (e.g. the Cochrane Library). Articles within the same journal may be similar due to editorial practices and policies, reporting requirements and endorsement of guidelines. There is emerging evidence that these are real concerns that should be accounted for in analyses [ 43 ]. Some cluster variables are described in the section: “ What variables are relevant to methodological studies?”

A variety of modelling approaches can be used to account for correlated data, including the use of marginal, fixed or mixed effects regression models with appropriate computation of standard errors [ 44 ]. For example, Kosa et al. used generalized estimation equations to account for correlation of articles within journals [ 15 ]. Not accounting for clustering could lead to incorrect p -values, unduly narrow confidence intervals, and biased estimates [ 45 ].

Q: Should I extract data in duplicate?

A: Yes. Duplicate data extraction takes more time but results in less errors [ 19 ]. Data extraction errors in turn affect the effect estimate [ 46 ], and therefore should be mitigated. Duplicate data extraction should be considered in the absence of other approaches to minimize extraction errors. However, much like systematic reviews, this area will likely see rapid new advances with machine learning and natural language processing technologies to support researchers with screening and data extraction [ 47 , 48 ]. However, experience plays an important role in the quality of extracted data and inexperienced extractors should be paired with experienced extractors [ 46 , 49 ].

Q: Should I assess the risk of bias of research reports included in my methodological study?

A : Risk of bias is most useful in determining the certainty that can be placed in the effect measure from a study. In methodological studies, risk of bias may not serve the purpose of determining the trustworthiness of results, as effect measures are often not the primary goal of methodological studies. Determining risk of bias in methodological studies is likely a practice borrowed from systematic review methodology, but whose intrinsic value is not obvious in methodological studies. When it is part of the research question, investigators often focus on one aspect of risk of bias. For example, Speich investigated how blinding was reported in surgical trials [ 50 ], and Abraha et al., investigated the application of intention-to-treat analyses in systematic reviews and trials [ 51 ].

Q: What variables are relevant to methodological studies?

A: There is empirical evidence that certain variables may inform the findings in a methodological study. We outline some of these and provide a brief overview below:

Country: Countries and regions differ in their research cultures, and the resources available to conduct research. Therefore, it is reasonable to believe that there may be differences in methodological features across countries. Methodological studies have reported loco-regional differences in reporting quality [ 52 , 53 ]. This may also be related to challenges non-English speakers face in publishing papers in English.

Authors’ expertise: The inclusion of authors with expertise in research methodology, biostatistics, and scientific writing is likely to influence the end-product. Oltean et al. found that among randomized trials in orthopaedic surgery, the use of analyses that accounted for clustering was more likely when specialists (e.g. statistician, epidemiologist or clinical trials methodologist) were included on the study team [ 54 ]. Fleming et al. found that including methodologists in the review team was associated with appropriate use of reporting guidelines [ 55 ].

Source of funding and conflicts of interest: Some studies have found that funded studies report better [ 56 , 57 ], while others do not [ 53 , 58 ]. The presence of funding would indicate the availability of resources deployed to ensure optimal design, conduct, analysis and reporting. However, the source of funding may introduce conflicts of interest and warrant assessment. For example, Kaiser et al. investigated the effect of industry funding on obesity or nutrition randomized trials and found that reporting quality was similar [ 59 ]. Thomas et al. looked at reporting quality of long-term weight loss trials and found that industry funded studies were better [ 60 ]. Kan et al. examined the association between industry funding and “positive trials” (trials reporting a significant intervention effect) and found that industry funding was highly predictive of a positive trial [ 61 ]. This finding is similar to that of a recent Cochrane Methodology Review by Hansen et al. [ 62 ]