Why school kids need more exposure to the world of work

Policy Analyst, Mitchell Institute, Victoria University

Disclosure statement

This Mitchell Institute policy report was produced with funding support from Cisco.

Victoria University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU.

View all partners

All students need to experience the world of work, particularly work of the future, long before they leave school, according to a new report out today.

The latest Mitchell Institute report, Connecting the worlds of learning and work , says collaborating with industry and the community is vital to better prepare children and young people for future work and life. And governments need to play a leading role to ensure this happens.

Read more: Partnering with scientists boosts school students' and teachers' confidence in science

Jobs in the digital age, and the skills and capabilities required to do them are transforming at an unprecedented rate .

Schools alone cannot be expected to foster the complex combinations of STEM (science, technology, engineering, maths), digital and transferable skills , like collaboration, problem solving and communication, that young people will need in their future careers. That’s in addition to core skills like literacy and numeracy.

Bringing together the classroom and the workplace has broad public benefits , but can be challenging to do in practice .

Read more: Mining young minds: the challenges of private interests and education

Why is this important?

Exposure to the world of work provides opportunities for students to build connections with professionals outside their usual family networks, and to learn by “doing” in real world contexts.

This offers some valuable benefits – enriching school learning, building students’ employability, and helping them develop the capabilities (such as problem solving, collaboration, and resilience) that we know are valued in work and life .

Read more: Lack of workers with 'soft skills' demands a shift in teaching

Some students already have access to valuable experiences like industry mentoring and entrepreneurship programs at school, but this isn’t the case for all students .

With young people spending longer in formal education, many might not connect with the world of work until their 20s.

For these students, once they complete their education, the “ new work reality ” is the average transition time from education to full-time work is now up to five years, compared to one year in 1986.

Traditionally, practical industry-focussed learning was anchored in vocational education and training, but participation rates in vocational pathways are declining.

Read more: Vocational education and training sector is still missing out on government funding: report

Shaping career choices

Young people’s pathways are formed early – with career aspirations often following traditional gender stereotypes, and tending to reflect students’ interest and achievement in traditional school subjects. A lack of interest in STEM subjects at age 10 is unlikely to change by age 14 .

Varied opportunities to engage with the world of work , through career talks, mentoring, and excursions to job sites can be valuable from primary school through to secondary school, particularly for students at risk of disengagement.

Early exposure is critical to ensure that students can make informed decisions about future career pathways.

Read more: Careers education must be for all, not just those going to university

Haven’t we heard this before?

There have been attempts to put school-industry partnerships on the national agenda over the past decade, but they still haven’t reached every school.

As the recent Gonski 2.0 Review found:

“While many models of school-community engagement exist in Australia, school-community engagement to improve student learning is not common practice and implementation can be ad hoc.”

We haven’t yet found a way to bring the workplace and the classroom together in an effective way.

What’s stopping this?

We need to address some systemic barriers to enable partnerships with industry to flourish in all schools:

Partnerships take time and resources for schools to initiate and manage – yet things that can be widely measured, like NAPLAN and ATAR , tend to be prioritised

We know teachers are central to making partnerships work – but many don’t have the time, or the training to know how to engage effectively with industry

There are many structural and administrative blockers that add layers of complexity for schools and industry partners. These include child safety requirements, occupational health and safety, and procurement policies for new equipment that are different in each state and territory.

Policymakers must design systems that make partnerships easier and ensure they are effective and available in all schools across Australia.

Here’s what governments can do

1. Track school-industry partnerships to ensure equity and help planning

Governments need to track where partnerships are happening, what they involve, how effective they are, and who is missing out. This information can inform government reforms that ensure resources are allocated equitably across the education system, and assist schools and industry to plan effective partnerships.

2. Support teachers by giving them time and resoources

Partnerships need time and resources. We need to give teachers time to engage in partnerships and provide them with professional learning and support to more easily facilitate effective partnerships. This may include using intermediaries, which come in many forms, such as industry peak bodies , government agencies and not-for-profit organisations .

3. Address barriers to make it easier for all to take part

For partnerships to be successful everywhere, governments need to address the structural barriers (regulatory and governance issues), information barriers (finding partners to connect with and understanding how to meet both school and industry needs), and equity barriers (ensuring the schools that benefit the most are connected to suitable industry partners).

- Vocational education and training

- Vocational training

- Schoolchildren

Associate Professor, Occupational Therapy

GRAINS RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION CHAIRPERSON

Project Officer, Student Program Development

Faculty of Law - Academic Appointment Opportunities

Audience Development Coordinator (fixed-term maternity cover)

- Top Colleges

- Top Courses

- Entrance Exams

- Admission 2024

- Study Abroad

- Study in Canada

- Study in UK

- Study in USA

- Study in Australia

- Study in Germany

- IELTS Material

- Scholarships

- Sarkari Exam

- Visual Stories

- Write a review

- Login/ Register

- Login / Register

Work Education: Meaning, Importance, Skills, Objectives

Pallavi Pradeep Purbey ,

Mar 4, 2024

Share it on:

Work education provides students with exposure to social and economic activities inside and outside the classroom. It helps them understand and build skills related to work education which will help them uplift themselves and be independent.

Work Education comprises activities consisting of services, foods, and community development in various areas of human needs such as health and hygiene, food, clothing, recreation, and social service in accordance with the mental abilities and manual skills of children at various stages of education.

Work education results in services valuable to the community, besides the gratification of self-fulfillment. It focuses on building manual characters. The main objective of work education is to ensure a greater sense of worldly knowledge and develop respect for workers among the students.

Table of Contents

What is Work Education?

Why work education, objectives of work education, importance of work education, advantages of work education, list of activities in work education.

Work education is the nature of knowledge that provides an identical significance to the community and social services by creating consciousness for the wellbeing of the people and society. An essential concept of work education is that it has a manual spirit. Therefore, work education plays an emphasis on learning while working in any field.

Below are some features of Work Education.

- Work education provides both knowledge and skills through understandable and graded programs and helps people enter into a world of work.

- It acts as a different curricular area for offering children opportunities for participating in social and economic activities inside and outside the classroom.

- The prolific manual work situations are drawn from health and hygiene, food, shelter, clothing, recreation, and community service.

- The skills to be developed in this field should comprise knowledge, understanding, practical skills, and values throughout need-based life activities.

- Pre-vocational education should get a prominent place at work education to let students choose various activities according to their interests.

Also Read: 10 Problem Solving Courses You Must Enrol Into Right Now

Work Experience has been named as Work Education and thus makes it a fundamental part of education. It develops;

- Personality.

- Positive work values.

- Constructive habits.

Moreover, work education conveys crucial knowledge related to career and develops proper work skills which can help the children to become productive in meeting their day to day activities.

Work Education helps students develop skills like work values, productivity, and self-reliance. In addition, work education allows students to identify their natural interests and aptitudes in selecting suitable courses of study.

Also Read: What is a Junior College? Here's What to Know

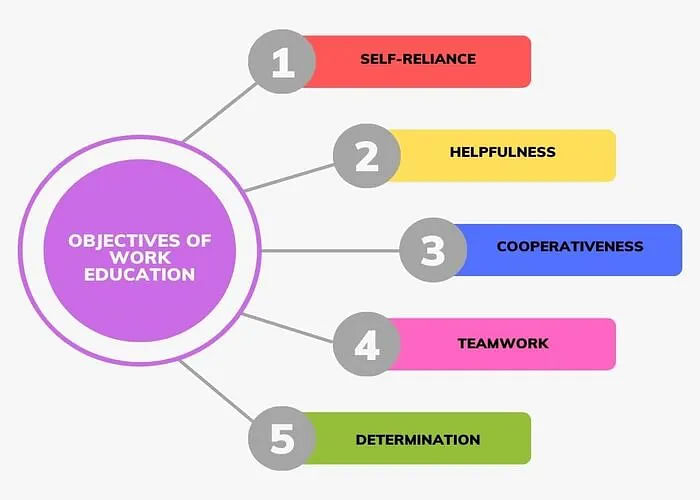

Work education has specific objectives, which are very important to give the right direction to people and the community. It acts as a vital part of the learning process resulting in goods or services considered valuable to the community. Work education focuses on teaching various socially desirable values such as;

Below is the list of objectives of work education.

- Identify the needs of every individual and their family and community concerning food, health, and hygiene to understand the working environment.

- Familiarize oneself with productive activities in the community in various sectors. It helps in gathering information about various activities in society.

- Know the sources of raw materials and understand the use of tools and equipment to produce goods and services by workers. It helps in gathering essential information.

- Develop skills for the assortment, procurement, arrangement, and utilization of tools and materials for different forms of productive work. It also helps in incorporating new skills.

- Develop self-esteem and confidence through accomplishment in productive work and services.

- Develop a deeper opinion for the environment and wisdom of belonging, responsibility, and commitment to society. It helps in developing a sense of belongingness within people.

- Develop reverence for manual work and regard for manual workers in the community to give them the utmost respect.

- Develop work habits such as punctuality, honesty, discipline, efficiency, and dedication to duty.

- Develop self-esteem and self-assurance through achievements in productive works and services in various fields.

- Develop a deeper apprehension for the environment and a sense of belongingness, responsibility, and commitment to society to ensure the community's welfare.

- Develop alertness of socio-economic problems of the society to ensure people about the changes if made.

Also Read: Buddhist Education System in India: Meaning, Objectives, Subjects

Work education is regarded as very important, meaningful, and the ongoing manual work is organized as a vital part of teaching-learning procedures that are functional to society and the satisfaction of doing work. It is essential for all education segments, i.e., primary, secondary, higher secondary, and higher education. Work education can be granted through a well-developed, channeled, and structured program.

Work education is an integral part of education as,

- It helps to bridge the gap between manual workers and white-collar workers in society.

- Work education gives respect to all types of workers in all sectors, and also creates social awareness for the welfare of society.

- It builds coordination in hand actions and brain activities.

- Work education promotes socially useful physical labor by inheriting educational activities in various fields.

- It acts as a necessary and significant factor in learning different activities and the processes to pursue a particular objective.

- Work education is discernible in the form of valuable services and productive work for the community.

- It is associated as a necessary factor with all the aspects of knowledge in a multi-level education system.

- Work education is based on the principle of learning by doing and practicing.

Also Read: Importance of Adult Education

Work education aids in various factors to the students and the people who are looking to work in varied areas. Students gain a plethora of knowledge about almost every field, and strategies are built on understanding and practicing such education. In addition, students are involved in activities that help them understand the concept of work education.

Below is the list of advantages of work education.

- Work education links classroom learning to the real world and makes students practice various activities.

- Work education gives opportunities to perform skills in real-world scenarios beyond theoretical learning.

- Work education helps students develop soft skills for the better manifestation of gifts.

- Work education gives students a chance to watch professionals in action entitled to work in various activities.

- It helps students associate with potential employers to broaden their network. And it leads to increased student enrollment with varied skills.

- Motivates students to understand and comprehend working areas.

- Work education provides opportunities for individualized instruction to perform skill-based activities. And it gets the community involved by providing an array of exciting work.

- Work education builds a pool of skilled workers to make the empire rise.

- Teaches soft skills that help in maintaining patience while working.

- Work education lowers recruitment costs for employers as there are people who would be highly skilled in a limited number of activities.

Also Read: What is Quality Education? Meaning and Importance

Work education includes activities of services, foods, and community development. It focused on health and hygiene sectors, food, clothing, recreation, and social service in harmony with children's mental abilities and manual skills related to work education. Below is the list of activities any person can enroll themselves in.

- Computer Education

- Drawing and Painting

- Work Experience

- Western Music

- Vocal Music

- Knitting and Stitching

- Gadgets learning

- Western Dance

- Creative Thinking

- General Assembly

- Sports and Games

- English Lab

- Smart Class

- Classical Dance

- Instrumental Music

Work education encourages children to know the needs of themselves, their families, and society. The aim is to build students' personalities to have a successful life by having moral values in their pocket of energy.

Also Read: Top 10 Benefits of Environmental Education 2024

Who gave the concept of work education?

What is called work education?

What is the history of work education?

POST YOUR COMMENT

Related articles.

Nirma University Syllabus 2024: Download PDF

Colleges Accepting JEE Advanced Score Other Than IITs in 2024

Calicut University Revaluation Result 2024: Direct Link

MAKAUT Syllabus 2024: Download PDF

Top 10 Degree Colleges in Hyderabad: Courses Offered and Admission Process

Gujarat University LLB Syllabus 2024: Download PDF

What are the Benefits of taking up KCET Exam 2024?

Get Free Scholarship worth 25000 INR

- International Peace and Security

- Higher Education and Research in Africa

- Andrew Carnegie Fellows

- Great Immigrants

- Carnegie Medal of Philanthropy

- Reporting Requirements

- Modification Requests

- Communications FAQs

- Grants Database

- Philanthropic Resources

- Grantmaking Highlights

- Past Presidents

- The Gospel of Wealth

- Other Carnegie Organizations

- Andrew Carnegie’s Story

- Governance and Policies

- Media Center

Why We Must Connect Education and the Future of Work

A lack of alignment among K–12, higher education, and the world of work threatens to compromise our resilience and success as a country. Education leaders at the Corporation argue that we must redesign our educational systems to reach a broader set of students

Fundamental goals for American public education are to ensure that each student is prepared to be an active participant in a robust democracy and to be successful in the global economy. This requires coordinated efforts among government, philanthropy, the business community, and the education sector. However, as our nation’s economic and labor market opportunities evolve, the lack of alignment among K–12, higher education, and the world of work is further exposed and compromises our resilience and success. Our institutions are working to meet the opportunities and demands of the future of work in relative isolation. We must encourage systematic connections that reach across the educational, political, and economic domains to holistically prepare students for life, work, and citizenship. This demands a redesign of educational and employment options for all students. We must ask tough questions about what contributions are needed from each sphere today to prepare the workforce of tomorrow.

Today’s high school students are arriving at college underprepared: 40 percent fail to graduate from four-year institutions, and 68 percent fail to graduate from two-year institutions. [1] Yet the future of work will require higher — not lower — college graduation rates. Already, our economy has 16 million recession-and automation-resistant middle-income jobs that require some postsecondary credential, as well as 35 million jobs that require a bachelor’s degree or higher. [2] Nearly half of American employers say they are struggling to fill positions — the highest number in more than a decade — citing dearths of applicants, experience, and both technical and soft skills as their biggest challenges. [3]

As our nation’s economic and labor market opportunities evolve, this lack of alignment among K–12, higher education, and the world of work will become further exposed and will compromise our resilience and success as a country. At present, students without access to higher education already experience less mobility and lower lifetime salaries. [4] Looking forward, if K–12 and higher education do not redesign their approaches to reach a broader set of students, we might experience even greater labor shortages and income disparities. If we want to alleviate these issues and prepare students for the careers of the future, it is imperative that we close the chasm between K–12 and higher education.

Those attempting to reform the education system are familiar with the ways in which it is fragmented. Many have experienced the unintended consequences that come from working in isolation and proceeding with untested assumptions, especially during efforts to scale innovations or foster long-term sustainability. We believe the solution is to work more integratively: to resist the temptation to tackle siloed, singular components and instead collaborate on large-scale transformations designed around a unified vision.

Looking forward, if K–12 and higher education do not redesign their approaches to reach a broader set of students, we might experience even greater labor shortages and income disparities.

That vision, when considering American public education, is to prepare each student for active participation in a robust democracy and success in an advanced global economy. Accomplishing this demands an approach that reaches across educational, political, and economic domains to seamlessly prepare students for life, work, and citizenship. It demands the redesign of educational and career pathways to allow for cross-pollination among all sectors, from business to government to philanthropy — and it demands asking tough questions about what each sphere must contribute today to prepare the workforce of tomorrow.

Higher education can play a unique role because it has the ability to reach in several directions: toward both K–12 schools and educators, and businesses and future employers. Since it is often under the control of the state, higher education can also reach across to the governor, mayor, and other decision- and policymakers. As such, higher education can do more than effect change within a single institution; instead, it can help to enact networks and policies across an entire city or state. In short, to prepare students to become citizens of the world — who also have economic opportunities in the future workplace — stakeholders must abandon their traditional silos and work together to achieve coherence.

The Case for Coherence

Linear, laser-focused strategies are appropriate when consequences are predictable, contexts are similar, and results are easily measured and few in number. But in the world of education, where contexts are diverse, the level of transformation needed is enormous, and the number of stakeholders is high, linear approaches to change do not work. They accomplish superficial, rather than meaningful, improvements and can lead to missteps and frustration.

To create longer-term solutions at scale, we must accept that education is a complex social system, and design strategies for change around that fundamental fact. If our goal is to move toward 21st-century teaching and learning that better prepares young people for the dynamic world of work, traditional top-down, isolated, programmatic approaches will not succeed. Rather, to effect broad change, we must be thoughtful, flexible, and inclusive, and we must consider myriad factors, including the vantage points and resources of all stakeholders.

Three Design Principles for Coherence

In one attempt to catalyze this shift, Carnegie Corporation of New York launched the Integration Design Consortium in 2017. The corporation extended grants to five organizations to design and implement two-year projects aimed at reducing fragmentation in education and advancing equity. During our collaboration with these initiatives — each focused on different disciplines, such as human-centered design, systems thinking, and change management — we saw several themes emerge again and again. Irrespective of the project or context, these principles seemed to be influential in making progress toward coherence. For those striving for educational change, we believe these three principles can serve as a foundation upon which to design innovative solutions, and a lens through which to envision ways of thinking and working differently.

Cultivating a Shared Purpose Rather than assuming that everyone engaged in educational improvement has similar priorities, deliberate attempts must be made to develop a shared understanding of what students need most during their journeys through the system. The work of defining this purpose cannot be done in an isolated manner; instead, a collective vision should be cocreated by various stakeholders, then anchored by thoughtful implementation planning. Developing a cohesive vision has multiple benefits, including increasing broad buy-in and helping individuals understand how their actions can lead to change at scale.

One promising initiative that exemplifies this approach is the Cowen Institute at Tulane University, which shares its purpose of advancing youth success with a multitude of stakeholders in its home city of New Orleans. In addition to disseminating salient research and implementing several direct service programs, the Cowen Institute develops and leads citywide collaboratives focused on promoting access to and persistence in college and careers. These include the New Orleans College Persistence Collaborative and the College and Career Counseling Collaborative, bringing together counselors and practitioners from high schools and community-based organizations across New Orleans under the common goal of increasing students’ access to and persistence in college and careers.

Rather than assuming that everyone engaged in educational improvement has similar priorities, deliberate attempts must be made to develop a shared understanding of what students need most during their journeys through the system.

By engaging in a shared review and understanding of data centered on the needs of all students, these communities of learning play an important role in cultivating a shared sense of purpose across a diversity of organizations and institutions. At the same time, they provide members with professional development, the opportunity to share best practices, and a means of engaging in collective problem-solving centered on improving college and career success for New Orleans youth.

Cocreating Inclusive Environments This principle, which has its roots in user-centered design, encourages the consideration of various points of view when developing policies, prioritizing input from those who will be directly affected by the outcome. It also urges individuals to assess their own beliefs before creating policies that reverberate through the entire system, and advocates the shifting of power structures so that those most affected have the opportunity to share their perspectives and play a role in the decision-making process. It is only by identifying the actors in the system, understanding their perspectives, and using their input that we can create inclusive and effective programs.

Transforming Postsecondary Education in Mathematics (TPSE Math) is one example of a movement to create an inclusive postsecondary environment. It focuses on a discipline that has traditionally been a barrier to student success: math.

In one study of 57 community colleges across several states, 59 percent of students were assigned to remedial math courses upon enrollment, and, of those, only 20 percent completed a college-level math course within three years. [5] Through TPSE Math, leading mathematicians have convened stakeholders across the country to change mathematics education at community colleges, four-year colleges, and research universities so that it better meets the needs of a diverse student body and their diverse future careers.

For example, TPSE has provided significant support in the national movement to develop multiple mathematics pathways for students. The goal is for every student to have the opportunity to take a rigorous entry-level mathematics course relevant to his or her field of study and future career and to significantly reduce the time for underprepared students to complete their first college-level math course. This results in more inclusive math departments and courses that focus on success for all students, not only those who will go on to be math majors or to remain in academia.

TPSE has also promoted cross-sector engagement by facilitating conversations about effective and innovative practices — including the connections between college mathematics and the world of work — and then sharing those learnings across institutions. These math departments are supporting a rich set of interdisciplinary academic experiences and pathways designed to prepare students with the mathematical knowledge and skills needed for engagement in society and the workforce.

Building Capacity That Is Responsive to Change To create infrastructure and processes that will be effective over the long term, it is crucial to acknowledge and accept the dynamic nature of the education system. This means prioritizing relationships and trust, and viewing a project’s initial implementation as the first of multiple iterations and trials, each of which considers the potential impact on different stakeholders. This is crucial because achieving broader coherence across the education system can seem daunting, so it is more manageable to identify a specific gap or disconnect to address, such as the transition from college to career.

Focusing on particular barriers and trying out solutions before prescribing them at scale acknowledges the dynamism of the sector and the complexities of coherence, while making meaningful progress on issues that matter.

The University Innovation Alliance (UIA), for instance, takes an agile, human-centered approach to increasing the number and diversity of college graduates in the United States. Since its founding in 2014, this national coalition of 11 public research universities has produced 29.6 percent more low-income bachelor’s degree graduates per year, amounting to nearly 13,000 graduates annually. The UIA estimates that the total will reach 100,000 by the 2022–2023 academic year. [6] *

True to the nature of the research institutions leading the work, the UIA accomplishes this through experimentation and iteration. One area of focus for the network has been ensuring student success beyond graduation through redesigning college-to-career supports to better ensure students find gainful employment upon graduation. The project uses design thinking, with its rapid prototyping of ideas and short feedback cycles, in service of reimagining career services to better support low-income students, first-generation students, and students of color.

The process of innovation starts with understanding the perspective of students and the current practices on campuses; providing career services professionals with the capacity, time, and connections they need to generate new campus solutions; and engaging employers and other stakeholders in the redesign. This approach is consistent with the vision of the UIA, that “by piloting new interventions, sharing insights about their relative cost and effectiveness, and scaling those interventions that are successful [,] . . . [its] collaborative work will catalyze systemic changes in the entire higher education sector. [7]

An Integrative Pathway to the Future

Strides in educational coherence are being made on a regional level, too. Tennessee and Colorado, for example, have adopted holistic cradle-to-career solutions that intentionally plan for the duration of their residents’ lifetimes, and the Central Ohio Compact has mobilized K–12, higher education, community-based organizations, and local industry with the goal of helping 65 percent of local adults earn a postsecondary credential by 2025. [8] Each of these initiatives exemplifies the design principles described earlier, by considering the experiences of key actors and employing a multistakeholder approach that includes policymakers — factors crucial to enacting change on a systemic level.

In most of the country, education, employment, and economic reform remain isolated in both policy and practice. If we continue down this path, limiting ourselves to what is possible within each of our silos, our mutual interests will soon be consumed by our differences.

Though these projects are promising, they are not enough. In most of the country, education, employment, and economic reform remain isolated in both policy and practice. If we continue down this path, limiting ourselves to what is possible within each of our silos, our mutual interests will soon be consumed by our differences. For the revolutionary changes that the future demands, we must move beyond this fragmented way of thinking and working, and accept that history’s boundaries no longer apply. We must take a coherent approach to connecting education and the future of work, harnessing integrative design principles to foster progress, flexibility, and inclusivity. To improve today and prepare for the future, we must build on these ideas together. We must embrace a user-centered approach that is designed around our ultimate goal: empowering and preparing our nation’s youth for fulfilling, engaged lives and productive careers, now and for decades to come.

[1] National Center for Education Statistics, “Undergraduate Retention and Graduation Rates,” May 2019, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_ctr.asp .

[2] Anthony P. Carnevale, Jeff Strohl, Neil Ridley, and Artem Gulish, “Three Educational Pathways to Good Jobs,” Georgetown University, 2018, https://cew.georgetown.edu/cew-reports/3pathways/ , 10.

[3] Manpower Group, “Solving the Talent Shortage: Build, Buy, Borrow and Bridge,” 2018, https://go.manpowergroup.com/talent-shortage-2018#thereport , 5–7.

[4] Jennifer Ma, Matea Penda, and Meredith Welch, “Education Pays 2016: The Benefits of Higher Education for Individuals and Society,” College Board, 2016, https://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/files/education-pays-2016-full-report.pdf , 3–4.

[5] T. Bailey, D. W. Jeong, and S. W. Cho, “Referral, Enrollment, and Completion in Developmental Education Sequences in Community Colleges, Economics of Education Review 29, no. 2 (2010): 255–70.

[6] The University Innovation Alliance, “Our Results,” http://www.theuia.org/#about .

[7] The University Innovation Alliance, “Vision and Prospectus,” http://www.theuia.org/sites/default/files/UIA-Vision-Prospectus.pdf .

[8] Central Ohio Compact, “Central Ohio’s Most Critical Challenge,” http://centralohiocompact.org/what-is-the-compact/our-challenge/ .

Excerpted from The Great Skills Gap: Optimizing Talent for the Future of Work (Stanford Business Books, 2021), edited by Jason Wingard, Dean Emeritus and Professor of Human Capital Management at Columbia University School of Professional Studies. Reprinted with permission.

*Note: Since the publication of the book, UIA reports an increase of annual degrees to low-income students by 46 percent since launch. Overall annual bachelor's degrees have increased 30 percent, and annual bachelor's degrees to students of color have increased 85 percent. They have exceeded 100,000 degrees.

LaVerne Srinivasan is vice president of Carnegie Corporation of New York’s National Program and program director of Education, Farhad Asghar is the Education program officer of the Pathways to Postsecondary Success portfolio, and Elise Henson is a former program analyst at the Corporation.

TOP: (Credit: SolStock/Getty Images)

Whether you call it digital, information, news, visual, or media literacy – it is vital for civic engagement and democracy

Addressing post-pandemic learning loss should include far greater support for programs that involve parents and caregivers in their kids’ educations

Why we should expose school kids to the world of work

To keep up with changing industries, school age students need real life exposure. Image: REUTERS/David Gray

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Kate Torii

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Entrepreneurship is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, entrepreneurship.

All students need to experience the world of work, particularly work of the future, long before they leave school, according to a new report out today.

The latest Mitchell Institute report, Connecting the worlds of learning and work , says collaborating with industry and the community is vital to better prepare children and young people for future work and life. And governments need to play a leading role to ensure this happens.

Jobs in the digital age, and the skills and capabilities required to do them are transforming at an unprecedented rate .

Schools alone cannot be expected to foster the complex combinations of STEM (science, technology, engineering, maths), digital and transferable skills , like collaboration, problem solving and communication, that young people will need in their future careers. That’s in addition to core skills like literacy and numeracy.

Bringing together the classroom and the workplace has broad public benefits , but can be challenging to do in practice .

Why is this important?

Exposure to the world of work provides opportunities for students to build connections with professionals outside their usual family networks, and to learn by “doing” in real world contexts.

Students picked by design thinking, coding and interview skills with this school-industry partnership.

This offers some valuable benefits – enriching school learning, building students’ employability, and helping them develop the capabilities (such as problem solving, collaboration, and resilience) that we know are valued in work and life .

Some students already have access to valuable experiences like industry mentoring and entrepreneurship programs at school, but this isn’t the case for all students .

With young people spending longer in formal education, many might not connect with the world of work until their 20s.

For these students, once they complete their education, the “ new work reality ” is the average transition time from education to full-time work is now up to five years, compared to one year in 1986.

Traditionally, practical industry-focussed learning was anchored in vocational education and training, but participation rates in vocational pathways are declining.

Shaping career choices

Young people’s pathways are formed early – with career aspirations often following traditional gender stereotypes, and tending to reflect students’ interest and achievement in traditional school subjects. A lack of interest in STEM subjects at age 10 is unlikely to change by age 14 .

Varied opportunities to engage with the world of work , through career talks, mentoring, and excursions to job sites can be valuable from primary school through to secondary school, particularly for students at risk of disengagement.

Early exposure is critical to ensure that students can make informed decisions about future career pathways.

Haven’t we heard this before?

There have been attempts to put school-industry partnerships on the national agenda over the past decade, but they still haven’t reached every school.

As the recent Gonski 2.0 Review found:

“While many models of school-community engagement exist in Australia, school-community engagement to improve student learning is not common practice and implementation can be ad hoc.”

We haven’t yet found a way to bring the workplace and the classroom together in an effective way.

What’s stopping this?

We need to address some systemic barriers to enable partnerships with industry to flourish in all schools:

Partnerships take time and resources for schools to initiate and manage – yet things that can be widely measured, like NAPLAN and ATAR , tend to be prioritised

We know teachers are central to making partnerships work – but many don’t have the time, or the training to know how to engage effectively with industry

Have you read?

Education systems can stifle creative thought. here’s how to do things differently, children's books need more female villains. here's why, higher education needs dusting off for the 21st century.

There are many structural and administrative blockers that add layers of complexity for schools and industry partners. These include child safety requirements, occupational health and safety, and procurement policies for new equipment that are different in each state and territory.

Policymakers must design systems that make partnerships easier and ensure they are effective and available in all schools across Australia.

Here’s what governments can do

1. Track school-industry partnerships to ensure equity and help planning

Governments need to track where partnerships are happening, what they involve, how effective they are, and who is missing out. This information can inform government reforms that ensure resources are allocated equitably across the education system, and assist schools and industry to plan effective partnerships.

2. Support teachers by giving them time and resoources

Partnerships need time and resources. We need to give teachers time to engage in partnerships and provide them with professional learning and support to more easily facilitate effective partnerships. This may include using intermediaries, which come in many forms, such as industry peak bodies , government agencies and not-for-profit organisations .

3. Address barriers to make it easier for all to take part

For partnerships to be successful everywhere, governments need to address the structural barriers (regulatory and governance issues), information barriers (finding partners to connect with and understanding how to meet both school and industry needs), and equity barriers (ensuring the schools that benefit the most are connected to suitable industry partners).

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Entrepreneurship .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

3 social economy innovators that are driving change in Brazil

Eliane Trindade

April 4, 2024

Driving impact: UpLink journey towards a more sustainable future

January 17, 2024

These innovators are accelerating the aviation industry's transition to net-zero

Gianluca Gygax

January 16, 2024

From solar-powered dryers to plastic decontaminators: Here's why green tech needs investment

Olivier M. Schwab

January 15, 2024

Q&A: How supporting early-stage start-ups can help achieve climate and nature goals

Laura Beltran

January 14, 2024

The Corporate Social Innovation Compass: Accelerating Impact through Social Enterprise Partnerships

The Job: Skills Training for the Undegreed

Will the Rise of AI Spell the Demise of Social Capital?

Can Texas Apprenticeships Put a Dent in the Nursing Shortage?

- Apprenticeship

The Job: Preparing Amid Uncertainty

The key to better education and career decisions? Work experience—in high school

Every student should have a work-based learning experience before they leave high school.

Whether a short-term project or a years-long internship, such real-world experiences are critical to helping students navigate from education to career. Students get an invaluable opportunity to explore their own career interests, experiment with—and possibly eliminate—potential careers before investing thousands of dollars or hours in education and training, and build a better understanding of the way they like to work. Taken together, that helps them more deliberately navigate a postsecondary path to success.

My own experience, which included a high school internship and deep connections with mentors, undoubtedly helped me choose a postsecondary education and career path that was right for me. At conferences and meetings when people ask, “Who is actually doing a job they went to college for?,” I am one of the few people who can raise their hand. I attribute that to the many opportunities I had in high school and college to try different career possibilities through work-based learning.

Still, research shows that there’s a gap between interest in and awareness and completion of these opportunities. A recent study by American Student Assistance found that while 79% of high school students would be interested in a work-based learning experience, only 34% were aware of any opportunities for students their age—and just 2% of students had completed an internship during high school . Moreover, there has been a steady decline in teens’ participation in the workforce over time—from 57.9% in 1979 to 35% between 2010 and 2018.

To reverse this trend, high school students must have equitable access to robust, high-quality work-based learning programs. That starts with regional and state leadership, and—as outlined in a new guide from ASA —there are four critical practices that stakeholders should keep in mind:

- Equal access for students regardless of gender, race, ethnicity, income level, disability status, or academic path.

- Outreach and awareness building among young people

- Incentives for employers to participate,

- And dedicated funding .

To provide greater access in Ohio, for instance, the state has changed labor regulations to make work-based learning for younger students possible and to reduce barriers to employer participation. Ohio’s minor labor laws explicitly exempt students participating in a career-technical or STEM program approved by the Ohio department of education, or in any eligible classes through the state’s dual enrollment program, including a state-recognized pre-apprenticeship program.

Increasing awareness among students is also critical. Many states have adopted a “work-based learning coordinator” model and tasked those coordinators with communicating among stakeholders about work-based learning programs and opportunities. This approach to communications, though, relies heavily on the capacity and networks of a single person, rather than leveraging the collective capacity and networks of stakeholders statewide.

To draw on those wider networks, some states also have built websites to help match young people with work-based learning opportunities . Rhode Island’s Work-Based Learning Navigator , for example, allows employers to post available work-based learning opportunities and educators to search and track those opportunities across the state and request resources based on their needs.

To encourage businesses to participate in work-based learning opportunities, some states provide incentives to offset employer costs. New Jersey’s Career Accelerator Internship Program provides participating employers with up to 50% of wages paid to new interns , up to $3,000 per student.

In terms of funding, districts and organizations often have difficulty sustaining work-based learning if there isn’t a dedicated funding source that makes the program a priority. To address this challenge, some states have inserted a line item in the state budget or created dedicated funding streams solely or primarily for creating and expanding work-based learning opportunities.

In Washington , for example, the 2019 Workforce Education Investment Act authorized $25 million in dedicated state funding to operate initiatives that support and scale work-based learning and other career-connected learning opportunities, as well as $11 million in capital and transportation funding to support these initiatives. Similarly, Massachusetts has a dedicated line-item in the annual state budget to fund high school internships and recently supported the launch of the Work-based Learning Alliance to scale accessibility to virtual work-based learning experiences.

We need to see more state and regional innovation of this kind. Doing so will ensure that more young people have the opportunity to experiment with careers—long before they have to commit to college, an apprenticeship, or another postsecondary path. Early experience means better decisions.

Julie Lammers, is senior vice president of advocacy and corporate social responsibility at American Student Assistance, which recently put out a comprehensive work-based learning guide, “ High School Work-based Learning: Best Practices Designed to Improve Career Readiness Outcomes for Today’s Youth .”

Related Posts

‘At a crossroads’: Reflections on engaging adult learners

Providing holistic support is good for students—and good for colleges, too.

There’s an ethical way to handle layoffs. Hint: It emphasizes learning and career mobility

Three big questions about AI and the future of work and learning

EdNC. Essential education news. Important stories. Your voice.

Perspective | helping students explore, discover, and prepare for a career.

Republish This Story

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

Republish our content

EdNC is a nonprofit, online, daily, independent newspaper. All of EdNC’s content is open source and free to republish. Please use the following guidelines when republishing our content.

- Our content must be republished in full. If your organization uses a paywall, the content must be provided in full for free.

- Credit our team by including both the author name and EdNC.org in the byline. Example: Alex Granados, EdNC.org .

- If republishing the story online, please provide a link to EdNC.org or a link to the original article in either the byline or credit line.

- The original headline of the article must be used. Allowable edits to the content of the piece include changes to meet your publication’s style guide and references to dates (i.e. this week changed to last week). Other edits must be approved by emailing Anna Pogarcic at [email protected] .

- Photos and other multimedia elements (audio, video, etc.) may not be republished without prior permission. Please email Anna Pogarcic at [email protected] if you are interested in sharing a multimedia element.

- If you republish a story, please let us know by emailing Anna Pogarcic at [email protected] .

Please email Anna Pogarcic at [email protected] if you have any questions.

by Cheryl C. Cox, EducationNC September 8, 2020

This <a target="_blank" href="https://www.ednc.org/perspective-helping-students-explore-discover-and-prepare-for-a-career/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://www.ednc.org">EducationNC</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://www.ednc.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/cropped-logo-square-512-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;"><img id="republication-tracker-tool-source" src="https://www.ednc.org/?republication-pixel=true&post=119227" style="width:1px;height:1px;">

Fall. That time of year when students begin their return to classrooms throughout the country.

For many students, the excitement of knowing that their graduation year is near is a complex emotion. Happiness, excitement, nervousness, and angst pull at the body and mind in diverse ways. A new beginning for the future lies just around the corner that can be both exciting and uncertain. Excitement for the next steps that life is bringing as well as feelings of hope, but also feelings of uncertainty for what that vision might really look like or how one goes about achieving that dream or goal.

Walk back in time with me a moment and reflect on your high school years.

Do you recall those years? Reflect on all the questions from parents, friends, relatives, teachers, counselors, youth leaders, and peers. Everyone wanted you to give them answers about your future, and they expected you to know immediately what your future would look like. You are a 17- or 18-year-old in high school, and it appears everyone thinks you are ready for adulthood.

They seem to think you should be ready to go out into this big old world and fly… and fly soon … like in just a few short months. Almost daily you are being asked, “What are your plans for your future? What will you do after graduation? What do you want to do for a living? Where are you going to school? How will you pay for your college or training?”

If you were like many of us, you were screaming in your mind, “WAIT! Stop. … Is there an Adulting 101 class I missed? I just want to enjoy high school! When do I apply for college? How do I really know what I want to do with my life? When is graduation? I don’t know what I want to do! I am going to college … but I don’t know about my career! I have no idea about career goals and my life ‘road map!’ I am just trying to ‘map out’ of high school.”

Sound familiar? For many students, these questions have existed for generations of time. Thankfully, over 900,000 North Carolina Career and Technical Education (CTE) students have many choices to help them explore the vast array of careers and help them decide firsthand if that career is a good choice for them.

CTE students start in middle school exploring and discovering career interests and inventories so that by the high school years, a more defined and concrete pathway can be built. This well-defined “road map” or “GPS” allows students to zoom in on the needed education and industry prerequisites, allowing for a successful, lucrative, and purposeful career.

The end result is years of schooling, time, and money not wasted on a career that is not aligned to one’s talents and abilities or a job that one does not enjoy or like.

How does CTE help students know what career is best for them? How does CTE help eliminate time and monetary resources from being wasted? The secret is in exploration, preparation, discovery, and work-based learning.

For many CTE students, the excitement is experienced in new ways, new concepts, and new environments. Classrooms today have a very different feel than in past years. Learning takes place in industry settings, giving students firsthand glimpses of what a career looks and feels like in a specific career pathway.

Internships and apprenticeships help students see firsthand the importance of preparation and education by doing and being a part of an industry – not just reading about it in a textbook. Work-based learning is a major focus for students, bringing enthusiasm, excitement, and a real-life view of the world of work. The work-based learning experiences offered in North Carolina schools through CTE programs connect learning to the textbook while helping students understand the “why” of what they have learned over the past 13 years.

My internship in high school was probably the most beneficial class to my career. I built relationships that led to recommendations for school and other jobs after that. It allowed me to get my foot in the door and know if I really wanted to pursue the career or not, while giving me real world experience as well. – Hannah Grubba, high school intern in Wake County Public School System. Currently works as a restaurant/pastry chef at the North Carolina Museum of Art .

Interning as a high school student was the most impactful use of a term I had. In addition to teaching me technical small business skills (inventory, management, networking, customer obsession, small business finances), interning at “Table of Contents” also sparked in me a great period of creativity and entrepreneurship and provided me a mentor for life. Transitioning into college was easier, and I was able to apply supply chain classroom topics to my time as an intern for small business in order to facilitate learning. – Shane Slider, high school intern in Wake County Public School System. Currently works at Amazon.

Take full advantage of the internship opportunity that is offered of you and earned. Having an internship in high school is very impressive to any potential employer. It will also give you an idea of what to expect at any future job opportunities. Besides the internship, having the fundamentals of business down will help you with the more demanding coursework of any collegiate course. Blake Hooks, high school intern at Winston-Salem/Forsyth County Schools. Currently works as a senior supply chain consultant at Sunrise Technologies.

Connecting the pieces of the puzzle is essential for students’ success and growth. There is no career that cannot be experienced or shadowed if given the chance and opportunity. Sometimes that career pathway is a hobby or an interest that is channeled into a livelihood and successful career.

Because of our business and industry partnerships, students are given opportunities never before experienced or made possible. Employers play an integral and important role in building a strong workforce pipeline. Educators, employers, and students can benefit greatly from these partnerships.

Businesses can help develop a student work force that is motivated and well-prepared by offering work-based learning opportunities. They can participate by serving on advisory boards and committees, participating in career fairs, being guest speakers, providing internships, offering job shadowing experiences, mentoring, conducting mock interviews, giving worksite tours, and being on local work-based learning boards. Each of these unique opportunities enhance and provide needed guidance and support for work-based learning experiences for North Carolina students.

Work-based learning strategies help students connect what they are learning in the classroom with the world of work and helps prepare tomorrow’s leaders today!

Career development and promoting work-based learning has been the passion and focus of Mrs. Cox’s educational career for the past 25 years.

Mrs. Cox has vast knowledge of cooperate as well as educational settings. Having begun her early career as an educational software and hardware vendor she quickly saw the need to connect with teachers and students to help them navigate the many technological advancements forthcoming. The pull to be front and center with students to help them meet these challenges led her straight into the classroom. Mrs. Cox has served in both the K-12 and postsecondary environments. Her former roles as a classroom teacher, adjunct professor, Career Development & Special Populations Coordinator, School-to-Career and Academy Director helped lead her to her present position as the Work-based Learning Consultant for the NC Department of Public Instruction in Career and Technical Education.

Mrs. Cox offers practical experiences and knowledge for multiple audiences and stakeholders. The knowledge for career development and fostering joint partnerships is evident in her daily life and work. Her insightful enthusiasm for bringing together all stake holders; businesses, educators, parents and students to help promote Career and Technical Education is her passion and her life goal. Her dream of promoting and increasing student opportunities via apprenticeships and internships is being seen throughout North Carolina by the large percentage of students participating and enrolling in work-based learning.

Her dream and goal to help all students be career ready in NC is heard loud and clear from the mountains to the shores of our great state.

Recommended reading

North Carolina saw a surge in apprenticeships this year. Here’s why.

by Molly Urquhart and Taylor Shain | March 12, 2020

More skilled workers needed for the jobs of tomorrow: Announcing 5,000 new apprenticeships

by Mebane Rash | February 19, 2020

Apprenticeships: A path from high school to middle-skill jobs

by Ferrel Guillory | May 5, 2017

The Importance of Work-based Education for the Future

Giving compass' take:.

- Writing for The 74, Tiffany Barfield explores how work-based learning can help advance career and education pipelines for students.

- How does COVID disruption to schooling impact progress in career readiness?

- Learn about inequity in work-based learning.

What is Giving Compass?

We connect donors to learning resources and ways to support community-led solutions. Learn more about us .

Two years of disrupted learning due to the pandemic have widened longstanding educational disparities that placed youth of color and those from underserved communities at a disadvantage when entering the workforce. Now, we have an unprecedented investment in the nation’s infrastructure that presents the possibility for numerous lucrative new jobs, particularly for young people. But without in-school preparation to develop workplace skills and knowledge, recent graduates will miss employment opportunities created by the $1 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act.

Bridging gaps in education and career development through work-based learning can both set students up to thrive in the workforce of the future and repair our nation’s decrepit infrastructure. These types of programs can give young people real-world experience while in high school, hone students’ academic, technical and employability skills and, by pairing preparation with opportunity, enable graduates to meet the new demands the infrastructure bill will create.

Unfortunately, our education system is not providing students with the skills and experience they need to succeed, particularly in the fields of science, technology engineering and math. Industries reliant on STEM faced a workforce shortage even before the pandemic, and as many as 2 million of an estimated 3.5 million manufacturing jobs may go vacant by 2025 because of the difficulty in finding people with the required skills. At the same time as the infrastructure package increases the need for workers with the capabilities to improve roads, bridges, railways and broadband access, COVID-19 learning loss has put students interested in pursuing STEM careers potentially six to 12 months behind in their education. Students of color are at increased risk of falling behind, with the pandemic widening pre-existing racial disparities in core subjects like math and science that are needed for success in high-paying jobs in these fields.

Fixing the school-to-career pipeline will become the driver of economic recovery. Schools must have the support to prepare learners for opportunities in indispensable high-wage, high-skill occupations that have proven resilient during economic upheavals. Work-based learning brings industry experts to the classroom and students to the workplace. These robust experiences incorporate academic achievement — credits toward a high school diploma or college — and professional training such as paid work experience and internships that help ensure students have pathways for long-term career success.

Read the full article about work-based learning by Tiffany Barfield at The 74. Read the full article

More Articles

How restorative justice can bring peace in schools, the hechinger report, apr 12, 2024, the importance of gender-responsive education in times of crisis.

Become a newsletter subscriber to stay up-to-date on the latest Giving Compass news.

Giving Compass Network

Partnerships & services.

We are a nonprofit too. Donate to Giving Compass to help us guide donors toward practices that advance equity.

Trending Issues

Copyright © 2024, Giving Compass Network

A 501(c)(3) organization. EIN: 85-1311683

- Skip to Nav

- Skip to Main

- Skip to Footer

For Students, the Importance of Doing Work That Matters

Please try again

By Will Richardson

We're halfway to school when my 14-year-old son remembers a homework assignment he forgot to do for biology class.

"Something big?" I ask, fearing the worst. "Nah," he says with a shrug. "Just a handout and some questions. It doesn't matter."

It's happened before, many times, in fact, that "it doesn't matter" response when it comes to work both of my kids are doing in school. This morning when he said it, I started trying to remember any work that they'd done this year that actually did matter in the world, work that seemed to have a purpose outside the classroom. Unfortunately, not much came to mind.

That's an especially frustrating reality for me because in my travels to schools around the world I see lots of examples of "work that matters"; high school kids in Philadelphia designing solar panels for hospitals in the African bush; middle school kids in San Diego writing books about their local ecosystems and selling them in local stores; primary school kids designing a new classroom wing being built at their school outside of Melbourne, Australia. And more.

"Work that matters" has significance beyond classroom walls; it's work that is created for an authentic audience who might enjoy it or benefit from it even in a small way. It's work that isn't simply passed to the teacher for a grade, or shared with peers for review. It's work that potentially makes a difference in the world.

And while we’ve always been able to do "work that matters" in our classrooms, our growing access to the Web and the tools and technologies of the modern world can certainly amplify the potentials for audience and for real world application of whatever it is our students are doing. Suddenly, our students have a potential audience of 2.5 billion people who could become readers or collaborators, and they've got all sorts of tools and apps in their backpacks that they can use to create really beautiful, meaningful work in ways that most of their teachers couldn't imagine doing when they were in school. I would argue, in fact, that the growing access to knowledge, information, people, and tools that our students are getting demands a shift in how we think about the work they do in school, one that moves them away from traditional, institutionally organized "assignments" and toward more student-organized projects that are centered on the intersection of their interests and the subject or standard at hand.

That argument becomes even more compelling when you look at the work some kids are doing on their own, outside of school, around their own interests and passions. Like 16-year-old Sean Fay Wolfe, whose 422-page book Quest for Justice (a novel set in Minecraft) currently ranks in the top 1 percent in sales of books sold on Amazon. Or like 12-year-old " Super Awesome Sylvia " Todd, who designed and helped to create a water color replicator that now sells in kit form for $295 . Or 15-year-old Jack Andraka , who used his after school time to work in a Johns Hopkins laboratory to invent a cancer test that obliterated the current gold standard.

Are these kids outliers? Sure. But they are also examples of what is now possible for every child and, I would add, each one of us as well. And those examples and the thousands more like them should compel us to rethink what's possible in our classrooms if we begin to open up to the potentials. Instead of passing paper, digital or otherwise, back and forth between students and teacher, what if we allowed students to do real work for real audiences that can read and interact far beyond the limits of the school walls, schedule, and curriculum? What if we let our students do work that they actually cared about and wanted to create, not for a grade but because of its potential contribution to and effect on the world?

No question, this kind of work is harder to manage and to assess; there is very little if any "work that matters" that happens when students sit to take state assessments. Even though this type of work might tell us much more about what a student has learned and can do with that learning than any traditional test, it's not as efficient or quantifiable or rankable.

Still, we can start small, can't we? What if we took 10% of what we're currently doing and handed it over to our students, asking them to meet the standard or the outcome we've set for them in a way that they care about and that had a purpose beyond the classroom? What if we created opportunities for them to educate, entertain, inspire, or connect with people from all over the globe who might be sincerely influenced by the work they’re doing? And what if we asked them to assess their own work in ways that matter to them, ways that inform them what worked, what didn’t work, and how they might do it differently down the road?

Schools and classrooms should support a deep culture of “doing work that matters,” where the adults in the building serve as models for the type of creating and learning we might expect from kids. And there should be a clear vision that everyone understands and works toward, one like the vision at Mount Vernon Presbyterian School in Atlanta which states: “We are a school of inquiry, innovation, and impact.” Impact, as in the work that students do carries more weight than just a grade.

The reality of this moment is that every one of our students can create and share and connect in ways that didn’t exist even a decade ago. I can’t imagine what it’s going to be like a decade from now. But I know this: if our students look at the work we’re asking them to do today and say “It doesn’t matter,” we’re missing a huge opportunity to help them become the learners they now need to be.

Will Richardson will be the opening keynote for the July 28-30 EdTechTeacher Summit in Chicago.

Education Is the Key to Better Jobs

Subscribe to the economic studies bulletin, michael greenstone , michael greenstone nonresident senior fellow - economic studies , the hamilton project adam looney , and adam looney nonresident senior fellow - economic studies michael greenstone and adam looney, the hamilton project mgaalthp michael greenstone and adam looney, the hamilton project.

September 17, 2012

Few issues are more critical than putting Americans back to work. With the economy adding private-sector jobs for the last 30 consecutive months and the unemployment rate continuing to tick down, another concern has begun to dominate the discussion. Is it enough to find a job, or should we be more focused on the quality of that job? For those Americans who have been displaced in the workforce, what are their prospects of finding comparable employment in the 21st century, post-recession economy? After all, having a job—any job—does not guarantee a wage that will support a family. How, then, can we foster an economy that produces quality, high-paying jobs?

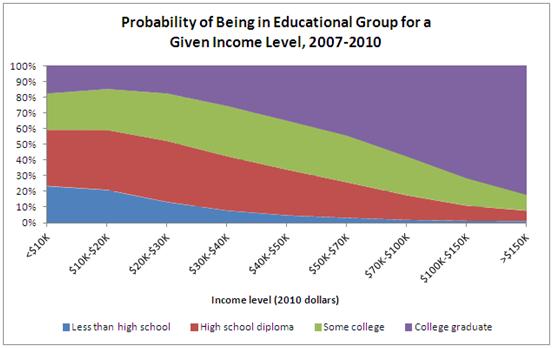

There may be a range of perspectives on the best way to move our economy forward, but one element essential to any answer is education. It may seem intuitive that more educated people earn more, yet the extent to which this is true is striking. A picture is often worth a thousand words, and the graph below illustrates this point.

The horizontal axis measures income while the vertical axis breaks up the income level by education level. As we move to the right toward higher incomes, we see that college graduates make up a bigger and bigger chunk of those earners. A few numbers help to underscore this. Those with only a high school diploma accounted for 39 percent of those who made between $20,000 and $30,000, but just 8 percent of those earning more than $100,000. In contrast, college graduates only accounted for 18 percent of the $20,000-to-$30,000 group and 75 percent of people earning more than $100,000, despite the population of these two educational demographic groups being roughly equal.

The message is clear—more education opens the gateway to better, higher-paying jobs. To put this into perspective, consider this:

- An individual with only a high school diploma is twice as likely to make under $40,000 per year than someone with a college degree.

- In contrast, an individual with a college degree is nearly nine times more likely to make over $100,000 than someone with only a high school diploma and 13 times more likely to make more than $200,000 per year.

On September 27th, The Hamilton Project will host an event focusing on the value of education, and opportunities to promote attainment and achievement in our K-12 system. We will release a series of economic facts about K-12 education in addition to three new discussion papers by outside authors— “Staying in School: A Proposal to Raise High School Graduation Rates,” “Learning from the Successes and Failures of Charter Schools,” and “Harnessing Technology to Improve K-12 Education.” Focusing on the new papers, three panels of distinguished experts will explore the value of stricter and better-enforced attendance laws, in coordination with other programs, to increase the high school graduation rate; the use of new evidence to demonstrate how targeted charter school methods could be successfully applied in public schools; and a new approach to evaluating education technologies to help speed the development of valuable new products.

The new Hamilton Project papers will be available on September 27th at 9:00 AM ET. For more information or to register for the event, click here .

Michael Greenstone is the director of The Hamilton Project and Adam Looney is its policy director. For more about the Project, visit www.hamiltonproject.org .

Economic Studies

The Hamilton Project

Amna Qayyum, Claudia Hui

March 7, 2024

February 1, 2024

Elyse Painter, Emily Gustafsson-Wright

January 5, 2024

The turning point: Why we must transform education now

Global warming. Accelerated digital revolution. Growing inequalities. Democratic backsliding. Loss of biodiversity. Devastating pandemics. And the list goes on. These are just some of the most pressing challenges that we are facing today in our interconnected world.

The diagnosis is clear: Our current global education system is failing to address these alarming challenges and provide quality learning for everyone throughout life. We know that education today is not fulfilling its promise to help us shape peaceful, just, and sustainable societies. These findings were detailed in UNESCO’s Futures of Education Report in November 2021 which called for a new social contract for education.

That is why it has never been more crucial to reimagine the way we learn, what we learn and how we learn. The turning point is now. It’s time to transform education. How do we make that happen?

Here’s what you need to know.

Why do we need to transform education?

The current state of the world calls for a major transformation in education to repair past injustices and enhance our capacity to act together for a more sustainable and just future. We must ensure the right to lifelong learning by providing all learners - of all ages in all contexts - the knowledge and skills they need to realize their full potential and live with dignity. Education can no longer be limited to a single period of one’s lifetime. Everyone, starting with the most marginalized and disadvantaged in our societies, must be entitled to learning opportunities throughout life both for employment and personal agency. A new social contract for education must unite us around collective endeavours and provide the knowledge and innovation needed to shape a better world anchored in social, economic, and environmental justice.

What are the key areas that need to be transformed?

- Inclusive, equitable, safe and healthy schools

Education is in crisis. High rates of poverty, exclusion and gender inequality continue to hold millions back from learning. Moreover, COVID-19 further exposed the inequities in education access and quality, and violence, armed conflict, disasters and reversal of women’s rights have increased insecurity. Inclusive, transformative education must ensure that all learners have unhindered access to and participation in education, that they are safe and healthy, free from violence and discrimination, and are supported with comprehensive care services within school settings. Transforming education requires a significant increase in investment in quality education, a strong foundation in comprehensive early childhood development and education, and must be underpinned by strong political commitment, sound planning, and a robust evidence base.