Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples

Published on June 19, 2020 by Pritha Bhandari . Revised on June 22, 2023.

Qualitative research involves collecting and analyzing non-numerical data (e.g., text, video, or audio) to understand concepts, opinions, or experiences. It can be used to gather in-depth insights into a problem or generate new ideas for research.

Qualitative research is the opposite of quantitative research , which involves collecting and analyzing numerical data for statistical analysis.

Qualitative research is commonly used in the humanities and social sciences, in subjects such as anthropology, sociology, education, health sciences, history, etc.

- How does social media shape body image in teenagers?

- How do children and adults interpret healthy eating in the UK?

- What factors influence employee retention in a large organization?

- How is anxiety experienced around the world?

- How can teachers integrate social issues into science curriculums?

Table of contents

Approaches to qualitative research, qualitative research methods, qualitative data analysis, advantages of qualitative research, disadvantages of qualitative research, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about qualitative research.

Qualitative research is used to understand how people experience the world. While there are many approaches to qualitative research, they tend to be flexible and focus on retaining rich meaning when interpreting data.

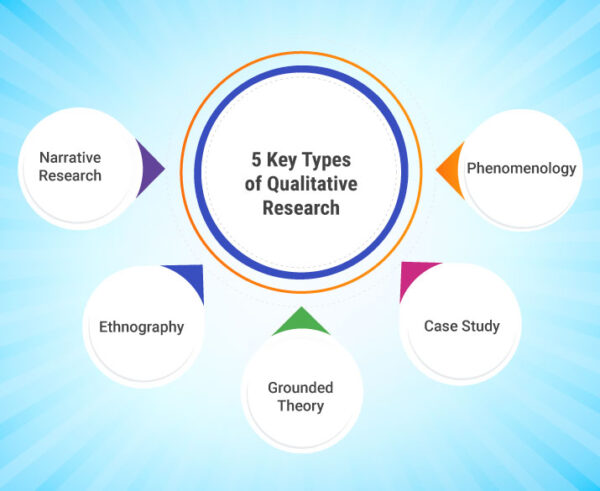

Common approaches include grounded theory, ethnography , action research , phenomenological research, and narrative research. They share some similarities, but emphasize different aims and perspectives.

Note that qualitative research is at risk for certain research biases including the Hawthorne effect , observer bias , recall bias , and social desirability bias . While not always totally avoidable, awareness of potential biases as you collect and analyze your data can prevent them from impacting your work too much.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

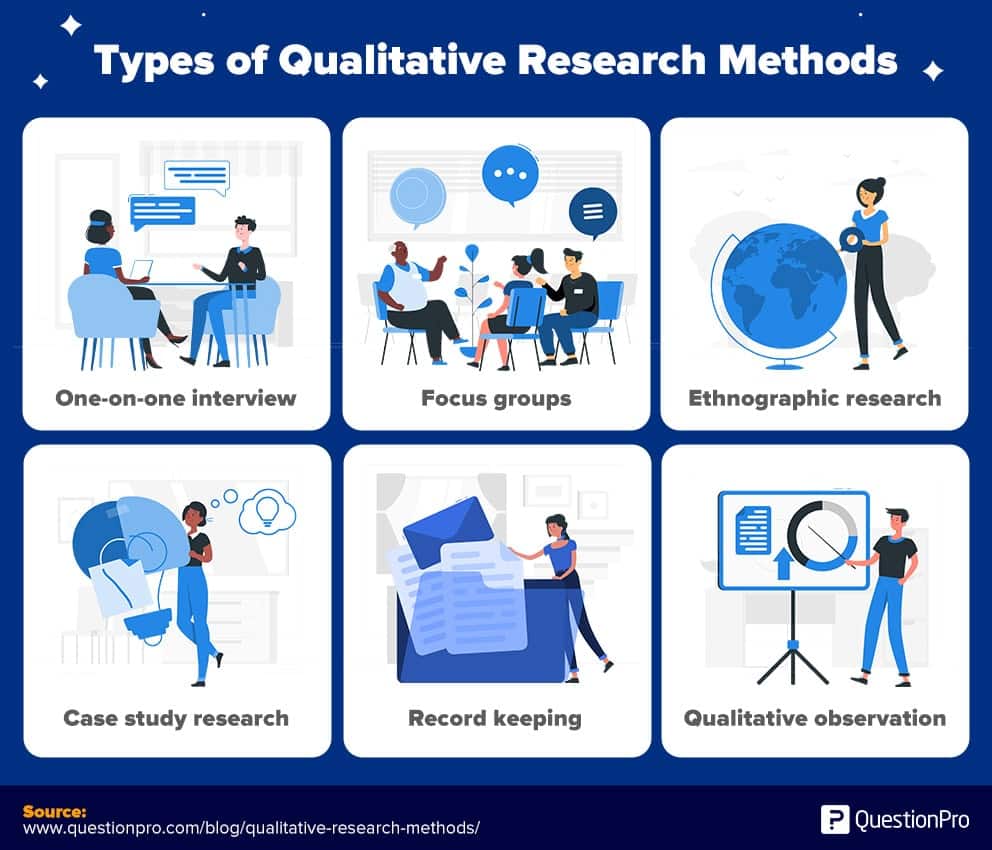

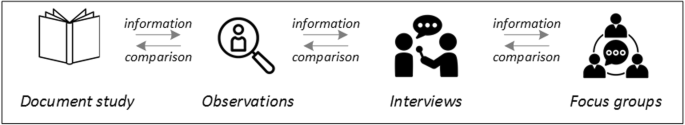

Each of the research approaches involve using one or more data collection methods . These are some of the most common qualitative methods:

- Observations: recording what you have seen, heard, or encountered in detailed field notes.

- Interviews: personally asking people questions in one-on-one conversations.

- Focus groups: asking questions and generating discussion among a group of people.

- Surveys : distributing questionnaires with open-ended questions.

- Secondary research: collecting existing data in the form of texts, images, audio or video recordings, etc.

- You take field notes with observations and reflect on your own experiences of the company culture.

- You distribute open-ended surveys to employees across all the company’s offices by email to find out if the culture varies across locations.

- You conduct in-depth interviews with employees in your office to learn about their experiences and perspectives in greater detail.

Qualitative researchers often consider themselves “instruments” in research because all observations, interpretations and analyses are filtered through their own personal lens.

For this reason, when writing up your methodology for qualitative research, it’s important to reflect on your approach and to thoroughly explain the choices you made in collecting and analyzing the data.

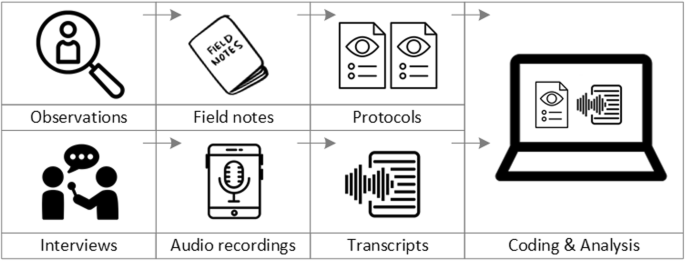

Qualitative data can take the form of texts, photos, videos and audio. For example, you might be working with interview transcripts, survey responses, fieldnotes, or recordings from natural settings.

Most types of qualitative data analysis share the same five steps:

- Prepare and organize your data. This may mean transcribing interviews or typing up fieldnotes.

- Review and explore your data. Examine the data for patterns or repeated ideas that emerge.

- Develop a data coding system. Based on your initial ideas, establish a set of codes that you can apply to categorize your data.

- Assign codes to the data. For example, in qualitative survey analysis, this may mean going through each participant’s responses and tagging them with codes in a spreadsheet. As you go through your data, you can create new codes to add to your system if necessary.

- Identify recurring themes. Link codes together into cohesive, overarching themes.

There are several specific approaches to analyzing qualitative data. Although these methods share similar processes, they emphasize different concepts.

Qualitative research often tries to preserve the voice and perspective of participants and can be adjusted as new research questions arise. Qualitative research is good for:

- Flexibility

The data collection and analysis process can be adapted as new ideas or patterns emerge. They are not rigidly decided beforehand.

- Natural settings

Data collection occurs in real-world contexts or in naturalistic ways.

- Meaningful insights

Detailed descriptions of people’s experiences, feelings and perceptions can be used in designing, testing or improving systems or products.

- Generation of new ideas

Open-ended responses mean that researchers can uncover novel problems or opportunities that they wouldn’t have thought of otherwise.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Researchers must consider practical and theoretical limitations in analyzing and interpreting their data. Qualitative research suffers from:

- Unreliability

The real-world setting often makes qualitative research unreliable because of uncontrolled factors that affect the data.

- Subjectivity

Due to the researcher’s primary role in analyzing and interpreting data, qualitative research cannot be replicated . The researcher decides what is important and what is irrelevant in data analysis, so interpretations of the same data can vary greatly.

- Limited generalizability

Small samples are often used to gather detailed data about specific contexts. Despite rigorous analysis procedures, it is difficult to draw generalizable conclusions because the data may be biased and unrepresentative of the wider population .

- Labor-intensive

Although software can be used to manage and record large amounts of text, data analysis often has to be checked or performed manually.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Chi square goodness of fit test

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

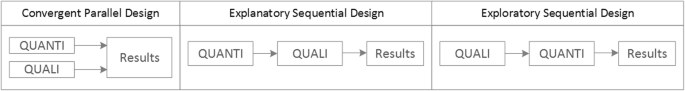

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to systematically measure variables and test hypotheses . Qualitative methods allow you to explore concepts and experiences in more detail.

There are five common approaches to qualitative research :

- Grounded theory involves collecting data in order to develop new theories.

- Ethnography involves immersing yourself in a group or organization to understand its culture.

- Narrative research involves interpreting stories to understand how people make sense of their experiences and perceptions.

- Phenomenological research involves investigating phenomena through people’s lived experiences.

- Action research links theory and practice in several cycles to drive innovative changes.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organizations.

There are various approaches to qualitative data analysis , but they all share five steps in common:

- Prepare and organize your data.

- Review and explore your data.

- Develop a data coding system.

- Assign codes to the data.

- Identify recurring themes.

The specifics of each step depend on the focus of the analysis. Some common approaches include textual analysis , thematic analysis , and discourse analysis .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2023, June 22). What Is Qualitative Research? | Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 27, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-research/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs. quantitative research | differences, examples & methods, how to do thematic analysis | step-by-step guide & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Qualitative Research – Methods, Analysis Types and Guide

Table of Contents

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is a type of research methodology that focuses on exploring and understanding people’s beliefs, attitudes, behaviors, and experiences through the collection and analysis of non-numerical data. It seeks to answer research questions through the examination of subjective data, such as interviews, focus groups, observations, and textual analysis.

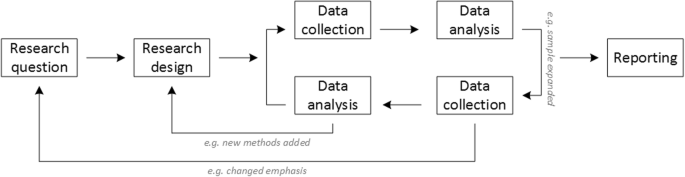

Qualitative research aims to uncover the meaning and significance of social phenomena, and it typically involves a more flexible and iterative approach to data collection and analysis compared to quantitative research. Qualitative research is often used in fields such as sociology, anthropology, psychology, and education.

Qualitative Research Methods

Qualitative Research Methods are as follows:

One-to-One Interview

This method involves conducting an interview with a single participant to gain a detailed understanding of their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. One-to-one interviews can be conducted in-person, over the phone, or through video conferencing. The interviewer typically uses open-ended questions to encourage the participant to share their thoughts and feelings. One-to-one interviews are useful for gaining detailed insights into individual experiences.

Focus Groups

This method involves bringing together a group of people to discuss a specific topic in a structured setting. The focus group is led by a moderator who guides the discussion and encourages participants to share their thoughts and opinions. Focus groups are useful for generating ideas and insights, exploring social norms and attitudes, and understanding group dynamics.

Ethnographic Studies

This method involves immersing oneself in a culture or community to gain a deep understanding of its norms, beliefs, and practices. Ethnographic studies typically involve long-term fieldwork and observation, as well as interviews and document analysis. Ethnographic studies are useful for understanding the cultural context of social phenomena and for gaining a holistic understanding of complex social processes.

Text Analysis

This method involves analyzing written or spoken language to identify patterns and themes. Text analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative text analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Text analysis is useful for understanding media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

This method involves an in-depth examination of a single person, group, or event to gain an understanding of complex phenomena. Case studies typically involve a combination of data collection methods, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis, to provide a comprehensive understanding of the case. Case studies are useful for exploring unique or rare cases, and for generating hypotheses for further research.

Process of Observation

This method involves systematically observing and recording behaviors and interactions in natural settings. The observer may take notes, use audio or video recordings, or use other methods to document what they see. Process of observation is useful for understanding social interactions, cultural practices, and the context in which behaviors occur.

Record Keeping

This method involves keeping detailed records of observations, interviews, and other data collected during the research process. Record keeping is essential for ensuring the accuracy and reliability of the data, and for providing a basis for analysis and interpretation.

This method involves collecting data from a large sample of participants through a structured questionnaire. Surveys can be conducted in person, over the phone, through mail, or online. Surveys are useful for collecting data on attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors, and for identifying patterns and trends in a population.

Qualitative data analysis is a process of turning unstructured data into meaningful insights. It involves extracting and organizing information from sources like interviews, focus groups, and surveys. The goal is to understand people’s attitudes, behaviors, and motivations

Qualitative Research Analysis Methods

Qualitative Research analysis methods involve a systematic approach to interpreting and making sense of the data collected in qualitative research. Here are some common qualitative data analysis methods:

Thematic Analysis

This method involves identifying patterns or themes in the data that are relevant to the research question. The researcher reviews the data, identifies keywords or phrases, and groups them into categories or themes. Thematic analysis is useful for identifying patterns across multiple data sources and for generating new insights into the research topic.

Content Analysis

This method involves analyzing the content of written or spoken language to identify key themes or concepts. Content analysis can be quantitative or qualitative. Qualitative content analysis involves close reading and interpretation of texts to identify recurring themes, concepts, and patterns. Content analysis is useful for identifying patterns in media messages, public discourse, and cultural trends.

Discourse Analysis

This method involves analyzing language to understand how it constructs meaning and shapes social interactions. Discourse analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as conversation analysis, critical discourse analysis, and narrative analysis. Discourse analysis is useful for understanding how language shapes social interactions, cultural norms, and power relationships.

Grounded Theory Analysis

This method involves developing a theory or explanation based on the data collected. Grounded theory analysis starts with the data and uses an iterative process of coding and analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data. The theory or explanation that emerges is grounded in the data, rather than preconceived hypotheses. Grounded theory analysis is useful for understanding complex social phenomena and for generating new theoretical insights.

Narrative Analysis

This method involves analyzing the stories or narratives that participants share to gain insights into their experiences, attitudes, and beliefs. Narrative analysis can involve a variety of methods, such as structural analysis, thematic analysis, and discourse analysis. Narrative analysis is useful for understanding how individuals construct their identities, make sense of their experiences, and communicate their values and beliefs.

Phenomenological Analysis

This method involves analyzing how individuals make sense of their experiences and the meanings they attach to them. Phenomenological analysis typically involves in-depth interviews with participants to explore their experiences in detail. Phenomenological analysis is useful for understanding subjective experiences and for developing a rich understanding of human consciousness.

Comparative Analysis

This method involves comparing and contrasting data across different cases or groups to identify similarities and differences. Comparative analysis can be used to identify patterns or themes that are common across multiple cases, as well as to identify unique or distinctive features of individual cases. Comparative analysis is useful for understanding how social phenomena vary across different contexts and groups.

Applications of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research has many applications across different fields and industries. Here are some examples of how qualitative research is used:

- Market Research: Qualitative research is often used in market research to understand consumer attitudes, behaviors, and preferences. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with consumers to gather insights into their experiences and perceptions of products and services.

- Health Care: Qualitative research is used in health care to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education: Qualitative research is used in education to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. Researchers conduct classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work : Qualitative research is used in social work to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : Qualitative research is used in anthropology to understand different cultures and societies. Researchers conduct ethnographic studies and observe and interview members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : Qualitative research is used in psychology to understand human behavior and mental processes. Researchers conduct in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy : Qualitative research is used in public policy to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. Researchers conduct focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

How to Conduct Qualitative Research

Here are some general steps for conducting qualitative research:

- Identify your research question: Qualitative research starts with a research question or set of questions that you want to explore. This question should be focused and specific, but also broad enough to allow for exploration and discovery.

- Select your research design: There are different types of qualitative research designs, including ethnography, case study, grounded theory, and phenomenology. You should select a design that aligns with your research question and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Recruit participants: Once you have your research question and design, you need to recruit participants. The number of participants you need will depend on your research design and the scope of your research. You can recruit participants through advertisements, social media, or through personal networks.

- Collect data: There are different methods for collecting qualitative data, including interviews, focus groups, observation, and document analysis. You should select the method or methods that align with your research design and that will allow you to gather the data you need to answer your research question.

- Analyze data: Once you have collected your data, you need to analyze it. This involves reviewing your data, identifying patterns and themes, and developing codes to organize your data. You can use different software programs to help you analyze your data, or you can do it manually.

- Interpret data: Once you have analyzed your data, you need to interpret it. This involves making sense of the patterns and themes you have identified, and developing insights and conclusions that answer your research question. You should be guided by your research question and use your data to support your conclusions.

- Communicate results: Once you have interpreted your data, you need to communicate your results. This can be done through academic papers, presentations, or reports. You should be clear and concise in your communication, and use examples and quotes from your data to support your findings.

Examples of Qualitative Research

Here are some real-time examples of qualitative research:

- Customer Feedback: A company may conduct qualitative research to understand the feedback and experiences of its customers. This may involve conducting focus groups or one-on-one interviews with customers to gather insights into their attitudes, behaviors, and preferences.

- Healthcare : A healthcare provider may conduct qualitative research to explore patient experiences and perspectives on health and illness. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with patients and their families to gather information on their experiences with different health care providers and treatments.

- Education : An educational institution may conduct qualitative research to understand student experiences and to develop effective teaching strategies. This may involve conducting classroom observations and interviews with students and teachers to gather insights into classroom dynamics and instructional practices.

- Social Work: A social worker may conduct qualitative research to explore social problems and to develop interventions to address them. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals and families to understand their experiences with poverty, discrimination, and other social problems.

- Anthropology : An anthropologist may conduct qualitative research to understand different cultures and societies. This may involve conducting ethnographic studies and observing and interviewing members of different cultural groups to gain insights into their beliefs, practices, and social structures.

- Psychology : A psychologist may conduct qualitative research to understand human behavior and mental processes. This may involve conducting in-depth interviews with individuals to explore their thoughts, feelings, and experiences.

- Public Policy: A government agency or non-profit organization may conduct qualitative research to explore public attitudes and to inform policy decisions. This may involve conducting focus groups and one-on-one interviews with members of the public to gather insights into their perspectives on different policy issues.

Purpose of Qualitative Research

The purpose of qualitative research is to explore and understand the subjective experiences, behaviors, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Unlike quantitative research, which focuses on numerical data and statistical analysis, qualitative research aims to provide in-depth, descriptive information that can help researchers develop insights and theories about complex social phenomena.

Qualitative research can serve multiple purposes, including:

- Exploring new or emerging phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring new or emerging phenomena, such as new technologies or social trends. This type of research can help researchers develop a deeper understanding of these phenomena and identify potential areas for further study.

- Understanding complex social phenomena : Qualitative research can be useful for exploring complex social phenomena, such as cultural beliefs, social norms, or political processes. This type of research can help researchers develop a more nuanced understanding of these phenomena and identify factors that may influence them.

- Generating new theories or hypotheses: Qualitative research can be useful for generating new theories or hypotheses about social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data about individuals’ experiences and perspectives, researchers can develop insights that may challenge existing theories or lead to new lines of inquiry.

- Providing context for quantitative data: Qualitative research can be useful for providing context for quantitative data. By gathering qualitative data alongside quantitative data, researchers can develop a more complete understanding of complex social phenomena and identify potential explanations for quantitative findings.

When to use Qualitative Research

Here are some situations where qualitative research may be appropriate:

- Exploring a new area: If little is known about a particular topic, qualitative research can help to identify key issues, generate hypotheses, and develop new theories.

- Understanding complex phenomena: Qualitative research can be used to investigate complex social, cultural, or organizational phenomena that are difficult to measure quantitatively.

- Investigating subjective experiences: Qualitative research is particularly useful for investigating the subjective experiences of individuals or groups, such as their attitudes, beliefs, values, or emotions.

- Conducting formative research: Qualitative research can be used in the early stages of a research project to develop research questions, identify potential research participants, and refine research methods.

- Evaluating interventions or programs: Qualitative research can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions or programs by collecting data on participants’ experiences, attitudes, and behaviors.

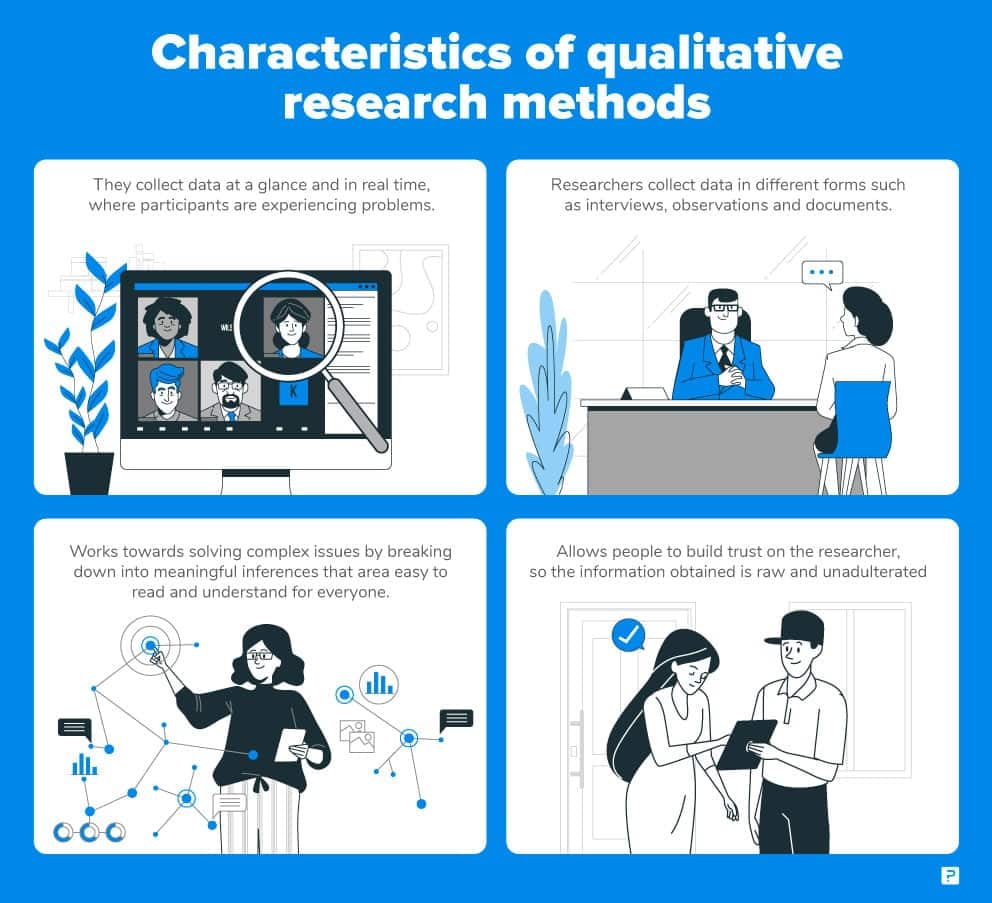

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research is characterized by several key features, including:

- Focus on subjective experience: Qualitative research is concerned with understanding the subjective experiences, beliefs, and perspectives of individuals or groups in a particular context. Researchers aim to explore the meanings that people attach to their experiences and to understand the social and cultural factors that shape these meanings.

- Use of open-ended questions: Qualitative research relies on open-ended questions that allow participants to provide detailed, in-depth responses. Researchers seek to elicit rich, descriptive data that can provide insights into participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Sampling-based on purpose and diversity: Qualitative research often involves purposive sampling, in which participants are selected based on specific criteria related to the research question. Researchers may also seek to include participants with diverse experiences and perspectives to capture a range of viewpoints.

- Data collection through multiple methods: Qualitative research typically involves the use of multiple data collection methods, such as in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation. This allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data from multiple sources, which can provide a more complete picture of participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Inductive data analysis: Qualitative research relies on inductive data analysis, in which researchers develop theories and insights based on the data rather than testing pre-existing hypotheses. Researchers use coding and thematic analysis to identify patterns and themes in the data and to develop theories and explanations based on these patterns.

- Emphasis on researcher reflexivity: Qualitative research recognizes the importance of the researcher’s role in shaping the research process and outcomes. Researchers are encouraged to reflect on their own biases and assumptions and to be transparent about their role in the research process.

Advantages of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research offers several advantages over other research methods, including:

- Depth and detail: Qualitative research allows researchers to gather rich, detailed data that provides a deeper understanding of complex social phenomena. Through in-depth interviews, focus groups, and observation, researchers can gather detailed information about participants’ experiences and perspectives that may be missed by other research methods.

- Flexibility : Qualitative research is a flexible approach that allows researchers to adapt their methods to the research question and context. Researchers can adjust their research methods in real-time to gather more information or explore unexpected findings.

- Contextual understanding: Qualitative research is well-suited to exploring the social and cultural context in which individuals or groups are situated. Researchers can gather information about cultural norms, social structures, and historical events that may influence participants’ experiences and perspectives.

- Participant perspective : Qualitative research prioritizes the perspective of participants, allowing researchers to explore subjective experiences and understand the meanings that participants attach to their experiences.

- Theory development: Qualitative research can contribute to the development of new theories and insights about complex social phenomena. By gathering rich, detailed data and using inductive data analysis, researchers can develop new theories and explanations that may challenge existing understandings.

- Validity : Qualitative research can offer high validity by using multiple data collection methods, purposive and diverse sampling, and researcher reflexivity. This can help ensure that findings are credible and trustworthy.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research also has some limitations, including:

- Subjectivity : Qualitative research relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers, which can introduce bias into the research process. The researcher’s perspective, beliefs, and experiences can influence the way data is collected, analyzed, and interpreted.

- Limited generalizability: Qualitative research typically involves small, purposive samples that may not be representative of larger populations. This limits the generalizability of findings to other contexts or populations.

- Time-consuming: Qualitative research can be a time-consuming process, requiring significant resources for data collection, analysis, and interpretation.

- Resource-intensive: Qualitative research may require more resources than other research methods, including specialized training for researchers, specialized software for data analysis, and transcription services.

- Limited reliability: Qualitative research may be less reliable than quantitative research, as it relies on the subjective interpretation of researchers. This can make it difficult to replicate findings or compare results across different studies.

- Ethics and confidentiality: Qualitative research involves collecting sensitive information from participants, which raises ethical concerns about confidentiality and informed consent. Researchers must take care to protect the privacy and confidentiality of participants and obtain informed consent.

Also see Research Methods

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

Qualitative Research : Definition

Qualitative research is the naturalistic study of social meanings and processes, using interviews, observations, and the analysis of texts and images. In contrast to quantitative researchers, whose statistical methods enable broad generalizations about populations (for example, comparisons of the percentages of U.S. demographic groups who vote in particular ways), qualitative researchers use in-depth studies of the social world to analyze how and why groups think and act in particular ways (for instance, case studies of the experiences that shape political views).

- Next: Choose an approach >>

- Choose an approach

- Find studies

- Learn methods

- Get software

- Get data for secondary analysis

- Network with researchers

- Last Updated: Jan 31, 2024 9:21 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.stanford.edu/qualitative_research

No internet connection.

All search filters on the page have been cleared., your search has been saved..

- All content

- Dictionaries

- Encyclopedias

- Expert Insights

- Foundations

- How-to Guides

- Journal Articles

- Little Blue Books

- Little Green Books

- Project Planner

- Tools Directory

- Sign in to my profile My Profile

- Sign in Signed in

- My profile My Profile

The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods

- Edited by: Lisa M. Given

- Publisher: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Publication year: 2008

- Online pub date: December 27, 2012

- Discipline: Anthropology

- Methods: Artistic inquiry , Action research

- DOI: https:// doi. org/10.4135/9781412963909

- Keywords: art , inquiry Show all Show less

- Print ISBN: 9781412941631

- Online ISBN: 9781412963909

- Buy the book icon link

Reader's guide

Entries a-z, subject index.

Qualitative research is designed to explore the human elements of a given topic, while specific qualitative methods examine how individuals see and experience the world. Qualitative approaches are typically used to explore new phenomena and to capture individuals' thoughts, feelings, or interpretations of meaning and process. Such methods are central to research conducted in education, nursing, sociology, anthropology, information studies, and other disciplines in the humanities, social sciences, and health sciences. Qualitative research projects are informed by a wide range of methodologies and theoretical frameworks.

The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods presents current and complete information as well as ready-to-use techniques, facts, and examples from the field of qualitative research in a very accessible style. In taking an interdisciplinary approach, these two volumes target a broad audience and fill a gap in the existing reference literature for a general guide to the core concepts that inform qualitative research practices. The entries cover every major facet of qualitative methods, including access to research participants, data coding, research ethics, the role of theory in qualitative research, and much more—all without overwhelming the informed reader.

Key Features

Defines and explains core concepts, describes the techniques involved in the implementation of qualitative methods, and presents an overview of qualitative approaches to research; Offers many entries that point to substantive debates among qualitative researchers regarding how concepts are labeled and the implications of such labels for how qualitative research is valuedl; Guides readers through the complex landscape of the language of qualitative inquiry; Includes contributors from various countries and disciplines that reflect a diverse spectrum of research approaches from more traditional, positivist approaches, through postmodern, constructionist ones; Presents some entries written in first-person voice and others in third-person voice to reflect the diversity of approaches that define qualitative work

Approaches and Methodologies; Arts-Based Research, Ties to; Computer Software; Data Analysis; Data Collection; Data Types and Characteristics; Dissemination; History of Qualitative Research; Participants; Quantitative Research, Ties to; Research Ethics; Rigor; Textual Analysis, Ties to; Theoretical and Philosophical Frameworks

The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods is designed to appeal to undergraduate and graduate students, practitioners, researchers, consultants, and consumers of information across the social sciences, humanities, and health sciences, making it a welcome addition to any academic or public library.

Front Matter

- Editorial Board

- List of Entries

- Reader's Guide

- About the Editor

- Contributors

- Introduction

Reader’s Guide

- A/r/tography

- Action Research

- Advocacy Research

- Applied Research

- Appreciative Inquiry

- Artifact Analysis

- Arts-Based Research

- Arts-Informed Research

- Autobiography

- Autoethnography

- Basic Research

- Clinical Research

- Collaborative Research

- Community-Based Research

- Comparative Research

- Content Analysis

- Conversation Analysis

- Covert Research

- Critical Action Research

- Critical Arts-Based Inquiry

- Critical Discourse Analysis

- Critical Ethnography

- Critical Hermeneutics

- Critical Research

- Cross-Cultural Research

- Discourse Analysis

- Document Analysis

- Duoethnography

- Ecological Research

- Emergent Design

- Empirical Research

- Empowerment Evaluation

- Ethnography

- Ethnomethodology

- Evaluation Research

- Evidence-Based Practice

- Explanatory Research

- Exploratory Data Analysis

- Feminist Research

- Field Research

- Foucauldian Discourse Analysis

- Genealogical Approach

- Grounded Theory

- Hermeneutics

- Heuristic Inquiry

- Historical Discourse Analysis

- Historical Research

- Historiography

- Indigenous Research

- Institutional Ethnography

- Institutional Research

- Interdisciplinary Research

- Internet in Qualitative Research

- Interpretive Inquiry

- Interpretive Phenomenology

- Interpretive Research

- Market Research

- Meta-Analysis

- Meta-Ethnography

- Meta-Synthesis

- Methodological Holism Versus Individualism

- Methodology

- Mixed Methods Research

- Multicultural Research

- Narrative Analysis

- Narrative Genre Analysis

- Narrative Inquiry

- Naturalistic Inquiry

- Observational Research

- Oral History

- Orientational Perspective

- Para-Ethnography

- Participatory Action Research (PAR)

- Performance Ethnography

- Phenomenography

- Phenomenology

- Place/Space in Qualitative Research

- Playbuilding

- Portraiture

- Program Evaluation

- Q Methodology

- Readers Theater

- Social Justice

- Social Network Analysis

- Survey Research

- Systemic Inquiry

- Theatre of the Oppressed

- Transformational Methods

- Unobtrusive Research

- Value-Free Inquiry

- Virtual Ethnography

- Virtual Research

- Visual Ethnography

- Visual Narrative Inquiry

- Bricolage and Bricoleur

- Connoisseurship

- Dance in Qualitative Research

- Ethnopoetics

- Fictional Writing

- Film and Video in Qualitative Research

- Literature in Qualitative Research

- Multimedia in Qualitative Research

- Music in Qualitative Research

- Photographs in Qualitative Research

- Photonovella and Photovoice

- Poetry in Qualitative Research

- Researcher as Artist

- Storytelling

- Visual Research

- Association for Qualitative Research (AQR)

- Center for Interpretive and Qualitative Research

- International Association of Qualitative Inquiry

- International Institute for Qualitative Methodology

- ResearchTalk, Inc.

- ATLAS.ti"(Software)

- Computer-Assisted Data Analysis

- Diction (Software)

- Ethnograph (Software)

- Framework (Software)

- HyperRESEARCH (Software)

- MAXqda (Software)

- NVivo (Software)

- Qualrus (Software)

- SuperHyperQual (Software)

- TextQuest (Software)

- Transana (Software)

- Analytic Induction

- ATLAS.ti" (Software)

- Audience Analysis

- Axial Coding

- Categorization

- Co-Constructed Narrative

- Codes and Coding

- Coding Frame

- Comparative Analysis

- Concept Mapping

- Conceptual Ordering

- Constant Comparison

- Context and Contextuality

- Context-Centered Knowledge

- Core Category

- Counternarrative

- Creative Writing

- Cultural Context

- Data Analysis

- Data Management

- Data Saturation

- Descriptive Statistics

- Discursive Practice

- Diversity Issues

- Embodied Knowledge

- Emergent Themes

- Emic/Etic Distinction

- Emotions in Qualitative Research

- Ethnographic Content Analysis

- Ethnostatistics

- Evaluation Criteria

- Everyday Life

- Experiential Knowledge

- Explanation

- Gender Issues

- Heteroglossia

- Historical Context

- Horizonalization

- Imagination in Qualitative Research

- In Vivo Coding

- Indexicality

- Interpretation

- Intertextuality

- Liminal Perspective

- Literature Review

- Lived Experience

- Marginalization

- Membership Categorization Device Analysis (MCDA)

- Memos and Memoing

- Meta-Narrative

- Negative Case Analysis

- Nonverbal Communication

- Open Coding

- Peer Review

- Psychological Generalization

- Rapid Assessment Process

- Reconstructive Analysis

- Recursivity

- Reflexivity

- Research Diaries and Journals

- Research Literature

- Researcher as Instrument

- Researcher Sensitivity

- Response Groups

- Rhythmanalysis

- Rigor in Qualitative Research

- Secondary Analysis

- Selective Coding

- Situatedness

- Social Context

- Systematic Sociological Introspection

- Tacit Knowledge

- Textual Analysis

- Thematic Coding and Analysis

- Theoretical Memoing

- Theoretical Saturation

- Thick Description

- Transcription

- Typological Analysis

- Understanding

- Video Intervention/Prevention Assessment

- Visual Data

- Visual Data Displays

- Writing Process

- Active Listening

- Audiorecording

- Captive Population

- Closed Question

- Cognitive Interview

- Convenience Sample

- Convergent Interviewing

- Conversational Interviewing

- Covert Observation

- Critical Incident Technique

- Data Archive

- Data Collection

- Data Generation

- Data Security

- Data Storage

- Diaries and Journals

- Email Interview

- Focus Groups

- Free Association Narrative Interview

- In-Depth Interview

- In-Person Interview

- Interactive Focus Groups

- Interactive Interview

- Interview Guide

- Interviewing

- Leaving the Field

- Life Stories

- Narrative Interview

- Narrative Texts

- Natural Setting

- Naturalistic Data

- Naturalistic Observation

- Negotiating Exit

- Neutral Question

- Neutrality in Qualitative Research

- Nonparticipant Observation

- Nonprobability Sampling

- Observation Schedule

- Open-Ended Question

- Participant Observation

- Peer Debriefing

- Pilot Study

- Probes and Probing

- Projective Techniques

- Prolonged Engagement

- Psychoanalytically Informed Observation

- Purposive Sampling

- Quota Sampling

- Random Sampling

- Recruiting Participants

- Research Problem

- Research Question

- Research Setting

- Research Team

- Researcher Roles

- Researcher Safety

- Sample Size

- Sampling Frame

- Secondary Data

- Semi-Structured Interview

- Sensitizing Concepts

- Serendipity

- Snowball Sampling

- Stratified Sampling

- Structured Interview

- Structured Observation

- Subjectivity Statement

- Telephone Interview

- Theoretical Sampling

- Triangulation

- Unstructured Interview

- Unstructured Observation

- Videorecording

- Virtual Interview

- Ethnography (Journal)

- Field Methods (Journal)

- Forum: Qualitative Social Research (Journal)

- International Journal of Qualitative Methods

- Journal of Contemporary Ethnography

- Journal of Mixed Methods Research

- Narrative Inquiry (Journal)

- Oral History Review (Journal)

- Qualitative Health Research (Journal)

- Qualitative Inquiry (Journal)

- Qualitative Report, The (Journal)

- Qualitative Research (Journal)

- Advances in Qualitative Methods Conference

- Ethnographic and Qualitative Research Conference

- First-Person Voice

- Interdisciplinary Qualitative Studies Conference

- International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry

- International Human Science Research Conference

- Publishing and Publication

- Qualitative Health Research Conference

- Representational Forms of Dissemination

- Research Proposal

- Education, Qualitative Research in

- Evolution of Qualitative Research

- Health Sciences, Qualitative Research in

- Humanities, Qualitative Research in

- Politics of Qualitative Research

- Qualitative Research, History of

- Social Sciences, Qualitative Research in

- Confidentiality

- Conflict of Interest

- Disengagement

- Disinterestedness

- Empowerment

- Informed Consent

- Insider/Outsider Status

- Intersubjectivity

- Key Informant

- Marginalized Populations

- Member Check

- Over-Rapport

- Participant

- Participants as Co-Researchers

- Reciprocity

- Researcher–Participant Relationships

- Secondary Participants

- Virtual Community

- Vulnerability

- Generalizability

- Objectivity

- Probability Sampling

- Quantitative Research

- Reductionism

- Reliability

- Replication

- Ethics Review Process

- Project Management

- Qualitative Research Summer Intensive

- Research Design

- Research Justification

- Theoretical Frameworks

- Thinking Qualitatively Workshop Conference

- Accountability

- Authenticity

- Ethics and New Media

- Ethics Codes

- Institutional Review Boards

- Integrity in Qualitative Research

- Relational Ethics

- Sensitive Topics

- Audit Trail

- Confirmability

- Credibility

- Dependability

- Inter- and Intracoder Reliability

- Observer Bias

- Subjectivity

- Transferability

- Translatability

- Transparency

- Trustworthiness

- Verification

- Discursive Psychology

- Chaos and Complexity Theories

- Constructivism

- Critical Humanism

- Critical Pragmatism

- Critical Race Theory

- Critical Realism

- Critical Theory

- Deconstruction

- Epistemology

- Essentialism

- Existentialism

- Feminist Epistemology

- Grand Narrative

- Grand Theory

- Nonessentialism

- Objectivism

- Postcolonialism

- Postmodernism

- Postpositivism

- Postrepresentation

- Poststructuralism

- Queer Theory

- Reality and Multiple Realities

- Representation

- Social Constructionism

- Structuralism

- Subjectivism

- Symbolic Interactionism

Sign in to access this content

Get a 30 day free trial, more like this, sage recommends.

We found other relevant content for you on other Sage platforms.

Have you created a personal profile? Login or create a profile so that you can save clips, playlists and searches

- Sign in/register

Navigating away from this page will delete your results

Please save your results to "My Self-Assessments" in your profile before navigating away from this page.

Sign in to my profile

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Learning Resources have to offer.

You must have a valid academic email address to sign up.

Get off-campus access

- View or download all content my institution has access to.

Sign up for a free trial and experience all Sage Research Methods has to offer.

- view my profile

- view my lists

Research Methodologies

- Quantitative Research Methodologies

Qualitative Research Methodologies

- Systematic Reviews

- Finding Articles by Methodology

- Design Your Research Project

Library Help

What is qualitative research.

Qualitative research methodologies seek to capture information that often can't be expressed numerically. These methodologies often include some level of interpretation from researchers as they collect information via observation, coded survey or interview responses, and so on. Researchers may use multiple qualitative methods in one study, as well as a theoretical or critical framework to help them interpret their data.

Qualitative research methods can be used to study:

- How are political and social attitudes formed?

- How do people make decisions?

- What teaching or training methods are most effective?

Qualitative Research Approaches

Action research.

In this type of study, researchers will actively pursue some kind of intervention, resolve a problem, or affect some kind of change. They will not only analyze the results but will also examine the challenges encountered through the process.

Ethnography

Ethnographies are an in-depth, holistic type of research used to capture cultural practices, beliefs, traditions, and so on. Here, the researcher observes and interviews members of a culture — an ethnic group, a clique, members of a religion, etc. — and then analyzes their findings.

Grounded Theory

Researchers will create and test a hypothesis using qualitative data. Often, researchers use grounded theory to understand decision-making, problem-solving, and other types of behavior.

Narrative Research

Researchers use this type of framework to understand different aspects of the human experience and how their subjects assign meaning to their experiences. Researchers use interviews to collect data from a small group of subjects, then discuss those results in the form of a narrative or story.

Phenomenology

This type of research attempts to understand the lived experiences of a group and/or how members of that group find meaning in their experiences. Researchers use interviews, observation, and other qualitative methods to collect data.

Often used to share novel or unique information, case studies consist of a detailed, in-depth description of a single subject, pilot project, specific events, and so on.

- Hossain, M.S., Runa, F., & Al Mosabbir, A. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on rare diseases: A case study on thalassaemia patients in Bangladesh. Public Health in Practice, 2(100150), 1-3.

- Nožina, M. (2021). The Czech Rhino connection: A case study of Vietnamese wildlife trafficking networks’ operations across central Europe. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 27(2), 265-283.

Focus Groups

Researchers will recruit people to answer questions in small group settings. Focus group members may share similar demographics or be diverse, depending on the researchers' needs. Group members will then be asked a series of questions and have their responses recorded. While these responses may be coded and discussed numerically (e.g., 50% of group members responded negatively to a question), researchers will also use responses to provide context, nuance, and other details.

- Dichabeng, P., Merat, N., & Markkula, G. (2021). Factors that influence the acceptance of future shared automated vehicles – A focus group study with United Kingdom drivers. Transportation Research: Part F, 82, 121–140.

- Maynard, E., Barton, S., Rivett, K., Maynard, O., & Davies, W. (2021). Because ‘grown-ups don’t always get it right’: Allyship with children in research—From research question to authorship. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(4), 518–536.

Observational Study

Researchers will arrange to observe (usually in an unobtrusive way) a set of subjects in specific conditions. For example, researchers might visit a school cafeteria to learn about the food choices students make or set up trail cameras to collect information about animal behavior in the area.

- He, J. Y., Chan, P. W., Li, Q. S., Li, L., Zhang, L., & Yang, H. L. (2022). Observations of wind and turbulence structures of Super Typhoons Hato and Mangkhut over land from a 356 m high meteorological tower. Atmospheric Research, 265(105910), 1-18.

- Zerovnik Spela, Kos Mitja, & Locatelli Igor. (2022). Initiation of insulin therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: An observational study. Acta Pharmaceutica, 72(1), 147–157.

Open-Ended Surveys

Unlike quantitative surveys, open-ended surveys require respondents to answer the questions in their own words.

- Mujcic, A., Blankers, M., Yildirim, D., Boon, B., & Engels, R. (2021). Cancer survivors’ views on digital support for smoking cessation and alcohol moderation: a survey and qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1-13.

- Smith, S. D., Hall, J. P., & Kurth, N. K. (2021). Perspectives on health policy from people with disabilities. Journal of Disability Policy Studies, 32(3), 224–232.

Structured or Semi-Structured Interviews

Researchers will recruit a small number of people who fit pre-determined criteria (e.g., people in a certain profession) and ask each the same set of questions, one-on-one. Semi-structured interviews will include opportunities for the interviewee to provide additional information they weren't asked about by the researcher.

- Gibbs, D., Haven-Tang, C., & Ritchie, C. (2021). Harmless flirtations or co-creation? Exploring flirtatious encounters in hospitable experiences. Tourism & Hospitality Research, 21(4), 473–486.

- Hongying Dai, Ramos, A., Tamrakar, N., Cheney, M., Samson, K., & Grimm, B. (2021). School personnel’s responses to school-based vaping prevention program: A qualitative study. Health Behavior & Policy Review, 8(2), 130–147.

- Call : 801.863.8840

- Text : 801.290.8123

- In-Person Help

- Email a Librarian

- Make an Appointment

- << Previous: Quantitative Research Methodologies

- Next: Systematic Reviews >>

- Last Updated: Mar 23, 2024 6:39 PM

- URL: https://uvu.libguides.com/methods

What is Qualitative Research? Definition, Types, Examples, Methods, and Best Practices

By Nick Jain

Published on: June 21, 2023

Table of Contents

What is Qualitative Research?

5 key types of qualitative research, examples of qualitative research, qualitative research methods: the top 4 techniques, qualitative research best practices.

Qualitative research is defined as an exploratory metho d that aims to understand complex phenomena, often within their natural settings, by examining subjective experiences, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors.

Unlike quantitative research , which focuses on numerical measurements and statistical analysis, qualitative research employs a range of data collection methods to gather detailed, non-numerical data that can provide in-depth insights into the research topic.

Here are the key characteristics of Qualitative Research:

- Subjectivity : Qualitative research acknowledges the subjective nature of human experiences and perceptions. It recognizes that individuals interpret and construct meaning based on their unique perspectives, cultural backgrounds, and social contexts. Researchers using qualitative methods aim to capture this subjectivity by engaging in detailed qualitative observations , interviews, and analyses that capture the nuances and complexities of human behavior.

- Contextualization : Qualitative research places a strong emphasis on the context in which social phenomena occur. It seeks to understand the interconnectedness between individuals, their environments, and the broader social structures that shape their experiences. Researchers delve into the specific settings and circumstances that influence the behavior and attitudes of participants, aiming to unravel the intricate relationships between different variables.

- Flexibility : Qualitative research is characterized by its flexibility and adaptability. Researchers have the freedom to modify their research design and methods during the course of the study based on emerging insights and new directions. This flexibility allows for iterative and exploratory research, enabling researchers to delve deeper into the subject matter and capture unexpected findings.

- Interpretation and meaning-making : Qualitative research recognizes that meaning is not fixed but constructed through social interactions and interpretations. Researchers engage in a process of interpretation and meaning-making to make sense of the data collected. This interpretive approach allows researchers to explore multiple perspectives, cultural influences, and social constructions that shape participants’ experiences and behaviors.

- Richness and depth : One of the key strengths of qualitative research is its ability to generate rich and in-depth data. Through methods such as interviews, focus groups , and participant observation, researchers can gather detailed narratives and descriptions that go beyond surface-level information. This depth of data enables a comprehensive understanding of the research topic, including the underlying motivations, emotions, and social dynamics at play.

- Inductive reasoning : Qualitative research often employs an inductive reasoning approach. Instead of starting with preconceived hypotheses or theories, researchers allow patterns and themes to emerge from the data. They engage in iterative cycles of data collection and analysis to develop theories or conceptual frameworks grounded in the empirical evidence gathered. This inductive process allows for new insights and discoveries that may challenge existing theories or offer alternative explanations.

- Naturalistic setting : Qualitative research frequently takes place in naturalistic settings, where participants are observed and studied in their everyday environments. This setting enhances the ecological validity of the research, as it allows researchers to capture authentic behaviors, interactions, and experiences. By observing individuals in their natural contexts, researchers can gain a deeper understanding of how social phenomena unfold in real-world situations.

Learn more: What is Qualitative Observation?

Here are the 5 key qualitative research types that are employed in studies:

1. Phenomenology : This type of research focuses on understanding the essence and meaning of a particular phenomenon or experience as perceived by individuals who have lived through it. It seeks to capture the subjective experiences and perspectives of participants.

2. Ethnography : Ethnographic research involves immersing oneself in a specific cultural or social group to observe and understand its practices, customs, beliefs, and values. Researchers spend extended periods of time within the community to gain a holistic view of its way of life.

3. Grounded Theory: Grounded theory aims to generate new theories or conceptual frameworks based on the analysis of data collected from interviews, observations, or documents. It involves systematically coding and categorizing data to identify patterns and develop theoretical explanations.

4. Case Study : In a case study, researchers conduct an in-depth examination of a single individual, group, or event to gain a detailed understanding of the subject of study. This approach allows for rich contextual information and can be particularly useful in exploring complex and unique cases.

5. Narrative Research: Narrative research focuses on analyzing the stories and personal narratives of individuals to gain insights into their experiences, identities, and sense-making processes. It emphasizes the power of storytelling in constructing meaning.

Example 1. A researcher conducting a phenomenological study might explore the lived experiences of individuals who have survived a natural disaster to understand the psychological and emotional impact of such events.

Example 2. An ethnographer might immerse themselves in a remote indigenous community to study their cultural practices, rituals, and social dynamics.

Example 3. A grounded theory study might investigate the coping mechanisms employed by cancer patients by conducting interviews and analyzing their experiences.

Example 4. A case study could involve examining a specific company’s organizational culture to understand its impact on employee performance and job satisfaction.

Example 5. A narrative research project might analyze the personal narratives of individuals who have experienced significant life transitions, such as migration or career changes, to understand the underlying meaning-making processes.

Learn more: What is Qualitative Market Research?

Here are the best qualitative research methods that offer unique advantages in capturing rich data, facilitating in-depth analysis, and generating comprehensive findings:

1. In-Depth Interviews

One of the most widely used qualitative research techniques is in-depth interviews. This method involves conducting one-on-one interviews with participants to gather rich, detailed information about their experiences, perspectives, and opinions. In-depth interviews allow researchers to explore a participant’s thoughts, emotions, and motivations, providing deep insights into their behavior and decision-making processes. The flexibility of this method allows for the exploration of individual experiences in great detail, making it particularly suitable for sensitive topics or complex phenomena. Through careful probing and open-ended questioning, researchers can develop a comprehensive understanding of the participant’s worldview, uncovering hidden patterns, and generating new hypotheses.

2. Focus Groups

Focus group research involves the gathering of a small group of individuals (typically 6-10) who share common characteristics or experiences. This method encourages participants to engage in open discussions facilitated by a skilled moderator. Focus groups offer a dynamic environment that allows participants to interact, share their perspectives, and build upon each other’s ideas. This method is particularly useful for exploring group dynamics, collective opinions, and societal norms. By observing interactions within the group, researchers can gain valuable insights into how social influences shape individual attitudes and behaviors. Focus groups also allow for the exploration of diverse viewpoints, enabling researchers to identify patterns, contradictions, and shared experiences.

3. Observational Research

Observational research involves systematically observing and documenting participants’ behaviors and interactions within their natural environments. This method provides researchers with a direct window into real-life contexts, allowing for a comprehensive understanding of social interactions, cultural practices, and behavioral patterns. Whether conducted through participant observation or unobtrusive observation, this method eliminates the potential biases associated with self-reporting, as participants’ actions speak louder than words. Observational research is especially valuable in studying nonverbal communication, contextual factors, and complex social systems. It can also provide insights into unarticulated behaviors or experiences that may be difficult to capture through other methods. However, careful planning, ethical considerations, and the need for prolonged engagement are crucial for conducting successful observational research .

4. Case Studies

Case studies involve an in-depth examination of a specific individual, group, organization, or event. Researchers collect data through various sources, such as interviews, observations, documents, and artifacts, to construct a holistic understanding of the case under investigation. This method allows for an exploration of complex social phenomena in their real-life context, uncovering rich, detailed insights that may not be accessible through other methods. Case studies provide an opportunity to examine unique or rare cases, delve into historical contexts, and generate context-specific knowledge. The findings from case studies are often highly detailed and context-bound, offering rich descriptions and contributing to theory development or refinement.

Qualitative research methods offer a range of powerful tools for exploring subjective experiences, meanings, and interpretations. In-depth interviews allow for the exploration of individual perspectives, while focus groups illuminate group dynamics. Observational research provides a direct view of participants’ behaviors, and case studies offer a holistic understanding of specific cases. By leveraging these qualitative methods, researchers can unveil deep insights, capture complex phenomena, and generate context-specific knowledge.

- Clear Research Objectives: Clearly define the qualitative research objectives, questions, or hypotheses that guide the study. This helps maintain focus and ensures that data collection and analysis are aligned with the research goals.

- Sampling Strategy: Select participants or cases that are relevant to the qualitative research questions and provide diverse perspectives. Purposeful sampling techniques, such as maximum variation or snowball sampling, can help ensure the inclusion of a wide range of experiences and viewpoints.

- Data Collection Rigor: Employ rigorous qualitative data collection techniques to ensure the accuracy, credibility, and depth of the findings. This may involve conducting multiple interviews or qualitative observations , using multiple sources of data, and taking detailed field notes.

- Ethical Considerations: Adhere to ethical guidelines and obtain informed consent from participants. Protect the privacy, confidentiality, and anonymity of participants and ensure their voluntary participation throughout the qualitative research process.

- Data Analysis: Utilize systematic and rigorous approaches to analyze qualitative research data. This may involve coding, categorizing, and identifying patterns or themes within the data. Software tools like NVivo or ATLAS.ti can assist in organizing and analyzing large datasets.

- Triangulation: Enhance the validity and reliability of the findings by employing triangulation. Triangulation involves using multiple data sources, methods, or researchers to corroborate and validate the results, reducing the impact of researcher bias.

- Member Checking: Share the preliminary findings with participants to verify the accuracy and interpretation of their data. Member checking allows participants to provide feedback and corrections, enhancing the trustworthiness of the research.

- Reflexive Journaling: Maintain a reflexive journal throughout the research process to record reflections, insights, and decisions made during data collection and analysis. This journal can serve as a valuable tool for ensuring transparency and traceability in the research process.

- Clear and Transparent Reporting: Present the research findings in a clear, coherent, and transparent manner. Clearly describe the research methodology, data collection, and analysis processes. Provide rich and thick descriptions of the findings, supported by direct quotations and examples from the data.

By following these best practices, qualitative researchers can enhance the rigor, credibility, and trustworthiness of their research, leading to valuable and meaningful insights into the complex phenomena under investigation.

Learn more: What is Customer Experience (CX) Research?

Enhance Your Research

Collect feedback and conduct research with IdeaScale’s award-winning software

Elevate Research And Feedback With Your IdeaScale Community!

IdeaScale is an innovation management solution that inspires people to take action on their ideas. Your community’s ideas can change lives, your business and the world. Connect to the ideas that matter and start co-creating the future.

Copyright © 2024 IdeaScale

Privacy Overview

Qualitative Research Using R: A Systematic Approach pp 1–19 Cite as

Qualitative Research: An Overview

- Yanto Chandra 3 &

- Liang Shang 4

- First Online: 24 April 2019

3670 Accesses

5 Citations

Qualitative research is one of the most commonly used types of research and methodology in the social sciences. Unfortunately, qualitative research is commonly misunderstood. In this chapter, we describe and explain the misconceptions surrounding qualitative research enterprise, why researchers need to care about when using qualitative research, the characteristics of qualitative research, and review the paradigms in qualitative research.

- Qualitative research

- Gioia approach

- Yin-Eisenhardt approach

- Langley approach

- Interpretivism

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Qualitative research is defined as the practice used to study things –– individuals and organizations and their reasons, opinions, and motivations, beliefs in their natural settings. It involves an observer (a researcher) who is located in the field , who transforms the world into a series of representations such as fieldnotes, interviews, conversations, photographs, recordings and memos (Denzin and Lincoln 2011 ). Many researchers employ qualitative research for exploratory purpose while others use it for ‘quasi’ theory testing approach. Qualitative research is a broad umbrella of research methodologies that encompasses grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss 2017 ; Strauss and Corbin 1990 ), case study (Flyvbjerg 2006 ; Yin 2003 ), phenomenology (Sanders 1982 ), discourse analysis (Fairclough 2003 ; Wodak and Meyer 2009 ), ethnography (Geertz 1973 ; Garfinkel 1967 ), and netnography (Kozinets 2002 ), among others. Qualitative research is often synonymous with ‘case study research’ because ‘case study’ primarily uses (but not always) qualitative data.

The quality standards or evaluation criteria of qualitative research comprises: (1) credibility (that a researcher can provide confidence in his/her findings), (2) transferability (that results are more plausible when transported to a highly similar contexts), (3) dependability (that errors have been minimized, proper documentation is provided), and (4) confirmability (that conclusions are internally consistent and supported by data) (see Lincoln and Guba 1985 ).

We classify research into a continuum of theory building — > theory elaboration — > theory testing . Theory building is also known as theory exploration. Theory elaboration refers to the use of qualitative data and a method to seek “confirmation” of the relationships among variables or processes or mechanisms of a social reality (Bartunek and Rynes 2015 ).

In the context of qualitative research, theory/ies usually refer(s) to conceptual model(s) or framework(s) that explain the relationships among a set of variables or processes that explain a social phenomenon. Theory or theories could also refer to general ideas or frameworks (e.g., institutional theory, emancipation theory, or identity theory) that are reviewed as background knowledge prior to the commencement of a qualitative research project.

For example, a qualitative research can ask the following question: “How can institutional change succeed in social contexts that are dominated by organized crime?” (Vaccaro and Palazzo 2015 ).

We have witnessed numerous cases in which committed positivist methodologists were asked to review qualitative papers, and they used a survey approach to assess the quality of an interpretivist work. This reviewers’ fallacy is dangerous and hampers the progress of a field of research. Editors must be cognizant of such fallacy and avoid it.

A social enterprises (SE) is an organization that combines social welfare and commercial logics (Doherty et al. 2014 ), or that uses business principles to address social problems (Mair and Marti 2006 ); thus, qualitative research that reports that ‘social impact’ is important for SEs is too descriptive and, arguably, tautological. It is not uncommon to see authors submitting purely descriptive papers to scholarly journals.

Some qualitative researchers have conducted qualitative work using primarily a checklist (ticking the boxes) to show the presence or absence of variables, as if it were a survey-based study. This is utterly inappropriate for a qualitative work. A qualitative work needs to show the richness and depth of qualitative findings. Nevertheless, it is acceptable to use such checklists as supplementary data if a study involves too many informants or variables of interest, or the data is too complex due to its longitudinal nature (e.g., a study that involves 15 cases observed and involving 59 interviews with 33 informants within a 7-year fieldwork used an excel sheet to tabulate the number of events that occurred as supplementary data to the main analysis; see Chandra 2017a , b ).

As mentioned earlier, there are different types of qualitative research. Thus, a qualitative researcher will customize the data collection process to fit the type of research being conducted. For example, for researchers using ethnography, the primary data will be in the form of photos and/or videos and interviews; for those using netnography, the primary data will be internet-based textual data. Interview data is perhaps the most common type of data used across all types of qualitative research designs and is often synonymous with qualitative research.

The purpose of qualitative research is to provide an explanation , not merely a description and certainly not a prediction (which is the realm of quantitative research). However, description is needed to illustrate qualitative data collected, and usually researchers describe their qualitative data by inserting a number of important “informant quotes” in the body of a qualitative research report.

We advise qualitative researchers to adhere to one approach to avoid any epistemological and ontological mismatch that may arise among different camps in qualitative research. For instance, mixing a positivist with a constructivist approach in qualitative research frequently leads to unnecessary criticism and even rejection from journal editors and reviewers; it shows a lack of methodological competence or awareness of one’s epistemological position.

Analytical generalization is not generalization to some defined population that has been sampled, but to a “theory” of the phenomenon being studied, a theory that may have much wider applicability than the particular case studied (Yin 2003 ).

There are different types of contributions. Typically, a researcher is expected to clearly articulate the theoretical contributions for a qualitative work submitted to a scholarly journal. Other types of contributions are practical (or managerial ), common for business/management journals, and policy , common for policy related journals.

There is ongoing debate on whether a template for qualitative research is desirable or necessary, with one camp of scholars (the pluralistic critical realists) that advocates a pluralistic approaches to qualitative research (“qualitative research should not follow a particular template or be prescriptive in its process”) and the other camps are advocating for some form of consensus via the use of particular approaches (e.g., the Eisenhardt or Gioia Approach, etc.). However, as shown in Table 1.1 , even the pluralistic critical realism in itself is a template and advocates an alternative form of consensus through the use of diverse and pluralistic approaches in doing qualitative research.

Alvesson, M., & Kärreman, D. (2007). Constructing mystery: Empirical matters in theory development. Academy of Management Review, 32 (4), 1265–1281.

Article Google Scholar

Bartunek, J. M., & Rynes, S. L. (2015). Qualitative research: It just keeps getting more interesting! In Handbook of qualitative organizational research (pp. 41–55). New York: Routledge.

Google Scholar

Brinkmann, S. (2018). Philosophies of qualitative research . New York: Oxford University Press.

Bucher, S., & Langley, A. (2016). The interplay of reflective and experimental spaces in interrupting and reorienting routine dynamics. Organization Science, 27 (3), 594–613.

Chandra, Y. (2017a). A time-based process model of international entrepreneurial opportunity evaluation. Journal of International Business Studies, 48 (4), 423–451.