Global Literature Review Software Market Report By Type (Cloud-Based, On-Premise), By Application (Large Enterprises, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs) And By Regions - Industry Trends, Size, Share, Growth, Estimation and Forecast, 2023-2032

The global demand for Literature Review Software Market is presumed to reach the valuation of nearly USD XX MN by 2030 from USD XX MN in 2022 with a CAGR of XX% during the period of 2023-2030. A literature review talks about the published material in a specific subject area, and at times within a certain time period. It can be just a humble synopsis of the sources, but typically a literature review includes structural patterns and blends both synopsis and synthesis. A synopsis is an outline of the important information drawn from the source; however, synthesis is a re-establishment of the same information. It may offer a newly analyzed version of old material or blend new with old analysis. A literature review software places each work in the context of its role and impact to have an insight into the research problem being examined in an automated way. The key focus of a literature review software is to outline, decode and synthesize the assertions and inklings of others without reinforcing new contributions in an automated way. Market Dynamics The ever-changing industry trends generate favorable prospects as well as complications with it. Literature Review Software helps to decode and analyze current industry trends and helps businesses to stay ahead of competitors and take the right business decisions at the right time. With the rise in industrialization and scientific research, the literature review software market is expected to flourish. The report covers Porter's Five Forces Model, Market Attractiveness Analysis and Value Chain analysis. These tools help to get a clear picture of the industry's structure and evaluate the competition attractiveness at a global level. Additionally, these tools also give inclusive assessment of each application/product segment in the global market of literature review software. Market Segmentation The entire literature review software market has been sub-categorized into type, application. The report provides an analysis of these subsets with respect to the geographical segmentation. This research study will keep marketer informed and helps to identify the target demographics for a product or service. By Type

- Cloud-Based

By Application

- Large Enterprises

- Small and Medium-sized Enterprises (SMEs)

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) about this Report

What is the Global Literature Review Software Market segmentation covered in the report?

Who are the leading Global Literature Review Software Market manufacturers profiled in the report?

- Single User License: $3,950.00

- Upto 10 Users License: $5,450.00

- Corporate User License: $8,600.00

- DataPack License: $2,100.00

Avail customized purchase options to meet your exact research needs:

- Buy sections of this report

- Buy country level reports

- Request for historical data

- Request discounts available for Start-Ups & Universities

- Define and measure the global market

- Volume or revenue forecast of the global market and its various sub-segments with respect to main geographies

- Analyze and identify major market trends along with the factors driving or inhibiting the market growth

- Study the company profiles of the major market players with their market share

- Analyze competitive developments

- Client First Policy

- Excellent Quality

- After Sales Support

- 24/7 Email Support

Key questions answered by the report

- What is the current market size and trends?

- What will be the market size during the forecast period?

- How various market factors such as a driver, restraints, and opportunity impact the market?

- What are the dominating segment and region in the market and why

Need specific market information?

- Ask for free product review call with the author

- Share your specific research requirments for a customized report

- Request for due diligence and consumer centric studies

- Request for study updates, segment specific and country level reports

USEFUL LINKS

- Upcoming Reports

- Testimonials

- How To Order

- Research Methodology

FIND ASSISTANCE

- Press Release

- Privacy Policy

- Refund Policy

- Terms & Conditions

UG-203, Gera Imperium Rise, Wipro Circle Metro Station, Hinjawadi, Pune - 411057

- [email protected]

- +1-888-294-1147

BUSINESS HOURS

Monday to Friday : 9 A.M IST to 6 P.M IST

Saturday-Sunday : Closed

Email Support : 24 x 7

© , All Rights Reserved, Value Market Research

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, what is your plagiarism score.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How To Write A Literature Review - A Complete Guide

Table of Contents

A literature review is much more than just another section in your research paper. It forms the very foundation of your research. It is a formal piece of writing where you analyze the existing theoretical framework, principles, and assumptions and use that as a base to shape your approach to the research question.

Curating and drafting a solid literature review section not only lends more credibility to your research paper but also makes your research tighter and better focused. But, writing literature reviews is a difficult task. It requires extensive reading, plus you have to consider market trends and technological and political changes, which tend to change in the blink of an eye.

Now streamline your literature review process with the help of SciSpace Copilot. With this AI research assistant, you can efficiently synthesize and analyze a vast amount of information, identify key themes and trends, and uncover gaps in the existing research. Get real-time explanations, summaries, and answers to your questions for the paper you're reviewing, making navigating and understanding the complex literature landscape easier.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explore everything from the definition of a literature review, its appropriate length, various types of literature reviews, and how to write one.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a collation of survey, research, critical evaluation, and assessment of the existing literature in a preferred domain.

Eminent researcher and academic Arlene Fink, in her book Conducting Research Literature Reviews , defines it as the following:

“A literature review surveys books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated.

Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have explored while researching a particular topic, and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within a larger field of study.”

Simply put, a literature review can be defined as a critical discussion of relevant pre-existing research around your research question and carving out a definitive place for your study in the existing body of knowledge. Literature reviews can be presented in multiple ways: a section of an article, the whole research paper itself, or a chapter of your thesis.

A literature review does function as a summary of sources, but it also allows you to analyze further, interpret, and examine the stated theories, methods, viewpoints, and, of course, the gaps in the existing content.

As an author, you can discuss and interpret the research question and its various aspects and debate your adopted methods to support the claim.

What is the purpose of a literature review?

A literature review is meant to help your readers understand the relevance of your research question and where it fits within the existing body of knowledge. As a researcher, you should use it to set the context, build your argument, and establish the need for your study.

What is the importance of a literature review?

The literature review is a critical part of research papers because it helps you:

- Gain an in-depth understanding of your research question and the surrounding area

- Convey that you have a thorough understanding of your research area and are up-to-date with the latest changes and advancements

- Establish how your research is connected or builds on the existing body of knowledge and how it could contribute to further research

- Elaborate on the validity and suitability of your theoretical framework and research methodology

- Identify and highlight gaps and shortcomings in the existing body of knowledge and how things need to change

- Convey to readers how your study is different or how it contributes to the research area

How long should a literature review be?

Ideally, the literature review should take up 15%-40% of the total length of your manuscript. So, if you have a 10,000-word research paper, the minimum word count could be 1500.

Your literature review format depends heavily on the kind of manuscript you are writing — an entire chapter in case of doctoral theses, a part of the introductory section in a research article, to a full-fledged review article that examines the previously published research on a topic.

Another determining factor is the type of research you are doing. The literature review section tends to be longer for secondary research projects than primary research projects.

What are the different types of literature reviews?

All literature reviews are not the same. There are a variety of possible approaches that you can take. It all depends on the type of research you are pursuing.

Here are the different types of literature reviews:

Argumentative review

It is called an argumentative review when you carefully present literature that only supports or counters a specific argument or premise to establish a viewpoint.

Integrative review

It is a type of literature review focused on building a comprehensive understanding of a topic by combining available theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence.

Methodological review

This approach delves into the ''how'' and the ''what" of the research question — you cannot look at the outcome in isolation; you should also review the methodology used.

Systematic review

This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research and collect, report, and analyze data from the studies included in the review.

Meta-analysis review

Meta-analysis uses statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects than those derived from the individual studies included within a review.

Historical review

Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, or phenomenon emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and identify future research's likely directions.

Theoretical Review

This form aims to examine the corpus of theory accumulated regarding an issue, concept, theory, and phenomenon. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories exist, the relationships between them, the degree the existing approaches have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested.

Scoping Review

The Scoping Review is often used at the beginning of an article, dissertation, or research proposal. It is conducted before the research to highlight gaps in the existing body of knowledge and explains why the project should be greenlit.

State-of-the-Art Review

The State-of-the-Art review is conducted periodically, focusing on the most recent research. It describes what is currently known, understood, or agreed upon regarding the research topic and highlights where there are still disagreements.

Can you use the first person in a literature review?

When writing literature reviews, you should avoid the usage of first-person pronouns. It means that instead of "I argue that" or "we argue that," the appropriate expression would be "this research paper argues that."

Do you need an abstract for a literature review?

Ideally, yes. It is always good to have a condensed summary that is self-contained and independent of the rest of your review. As for how to draft one, you can follow the same fundamental idea when preparing an abstract for a literature review. It should also include:

- The research topic and your motivation behind selecting it

- A one-sentence thesis statement

- An explanation of the kinds of literature featured in the review

- Summary of what you've learned

- Conclusions you drew from the literature you reviewed

- Potential implications and future scope for research

Here's an example of the abstract of a literature review

Is a literature review written in the past tense?

Yes, the literature review should ideally be written in the past tense. You should not use the present or future tense when writing one. The exceptions are when you have statements describing events that happened earlier than the literature you are reviewing or events that are currently occurring; then, you can use the past perfect or present perfect tenses.

How many sources for a literature review?

There are multiple approaches to deciding how many sources to include in a literature review section. The first approach would be to look level you are at as a researcher. For instance, a doctoral thesis might need 60+ sources. In contrast, you might only need to refer to 5-15 sources at the undergraduate level.

The second approach is based on the kind of literature review you are doing — whether it is merely a chapter of your paper or if it is a self-contained paper in itself. When it is just a chapter, sources should equal the total number of pages in your article's body. In the second scenario, you need at least three times as many sources as there are pages in your work.

Quick tips on how to write a literature review

To know how to write a literature review, you must clearly understand its impact and role in establishing your work as substantive research material.

You need to follow the below-mentioned steps, to write a literature review:

- Outline the purpose behind the literature review

- Search relevant literature

- Examine and assess the relevant resources

- Discover connections by drawing deep insights from the resources

- Structure planning to write a good literature review

1. Outline and identify the purpose of a literature review

As a first step on how to write a literature review, you must know what the research question or topic is and what shape you want your literature review to take. Ensure you understand the research topic inside out, or else seek clarifications. You must be able to the answer below questions before you start:

- How many sources do I need to include?

- What kind of sources should I analyze?

- How much should I critically evaluate each source?

- Should I summarize, synthesize or offer a critique of the sources?

- Do I need to include any background information or definitions?

Additionally, you should know that the narrower your research topic is, the swifter it will be for you to restrict the number of sources to be analyzed.

2. Search relevant literature

Dig deeper into search engines to discover what has already been published around your chosen topic. Make sure you thoroughly go through appropriate reference sources like books, reports, journal articles, government docs, and web-based resources.

You must prepare a list of keywords and their different variations. You can start your search from any library’s catalog, provided you are an active member of that institution. The exact keywords can be extended to widen your research over other databases and academic search engines like:

- Google Scholar

- Microsoft Academic

- Science.gov

Besides, it is not advisable to go through every resource word by word. Alternatively, what you can do is you can start by reading the abstract and then decide whether that source is relevant to your research or not.

Additionally, you must spend surplus time assessing the quality and relevance of resources. It would help if you tried preparing a list of citations to ensure that there lies no repetition of authors, publications, or articles in the literature review.

3. Examine and assess the sources

It is nearly impossible for you to go through every detail in the research article. So rather than trying to fetch every detail, you have to analyze and decide which research sources resemble closest and appear relevant to your chosen domain.

While analyzing the sources, you should look to find out answers to questions like:

- What question or problem has the author been describing and debating?

- What is the definition of critical aspects?

- How well the theories, approach, and methodology have been explained?

- Whether the research theory used some conventional or new innovative approach?

- How relevant are the key findings of the work?

- In what ways does it relate to other sources on the same topic?

- What challenges does this research paper pose to the existing theory

- What are the possible contributions or benefits it adds to the subject domain?

Be always mindful that you refer only to credible and authentic resources. It would be best if you always take references from different publications to validate your theory.

Always keep track of important information or data you can present in your literature review right from the beginning. It will help steer your path from any threats of plagiarism and also make it easier to curate an annotated bibliography or reference section.

4. Discover connections

At this stage, you must start deciding on the argument and structure of your literature review. To accomplish this, you must discover and identify the relations and connections between various resources while drafting your abstract.

A few aspects that you should be aware of while writing a literature review include:

- Rise to prominence: Theories and methods that have gained reputation and supporters over time.

- Constant scrutiny: Concepts or theories that repeatedly went under examination.

- Contradictions and conflicts: Theories, both the supporting and the contradictory ones, for the research topic.

- Knowledge gaps: What exactly does it fail to address, and how to bridge them with further research?

- Influential resources: Significant research projects available that have been upheld as milestones or perhaps, something that can modify the current trends

Once you join the dots between various past research works, it will be easier for you to draw a conclusion and identify your contribution to the existing knowledge base.

5. Structure planning to write a good literature review

There exist different ways towards planning and executing the structure of a literature review. The format of a literature review varies and depends upon the length of the research.

Like any other research paper, the literature review format must contain three sections: introduction, body, and conclusion. The goals and objectives of the research question determine what goes inside these three sections.

Nevertheless, a good literature review can be structured according to the chronological, thematic, methodological, or theoretical framework approach.

Literature review samples

1. Standalone

2. As a section of a research paper

How SciSpace Discover makes literature review a breeze?

SciSpace Discover is a one-stop solution to do an effective literature search and get barrier-free access to scientific knowledge. It is an excellent repository where you can find millions of only peer-reviewed articles and full-text PDF files. Here’s more on how you can use it:

Find the right information

Find what you want quickly and easily with comprehensive search filters that let you narrow down papers according to PDF availability, year of publishing, document type, and affiliated institution. Moreover, you can sort the results based on the publishing date, citation count, and relevance.

Assess credibility of papers quickly

When doing the literature review, it is critical to establish the quality of your sources. They form the foundation of your research. SciSpace Discover helps you assess the quality of a source by providing an overview of its references, citations, and performance metrics.

Get the complete picture in no time

SciSpace Discover’s personalized suggestion engine helps you stay on course and get the complete picture of the topic from one place. Every time you visit an article page, it provides you links to related papers. Besides that, it helps you understand what’s trending, who are the top authors, and who are the leading publishers on a topic.

Make referring sources super easy

To ensure you don't lose track of your sources, you must start noting down your references when doing the literature review. SciSpace Discover makes this step effortless. Click the 'cite' button on an article page, and you will receive preloaded citation text in multiple styles — all you've to do is copy-paste it into your manuscript.

Final tips on how to write a literature review

A massive chunk of time and effort is required to write a good literature review. But, if you go about it systematically, you'll be able to save a ton of time and build a solid foundation for your research.

We hope this guide has helped you answer several key questions you have about writing literature reviews.

Would you like to explore SciSpace Discover and kick off your literature search right away? You can get started here .

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. how to start a literature review.

• What questions do you want to answer?

• What sources do you need to answer these questions?

• What information do these sources contain?

• How can you use this information to answer your questions?

2. What to include in a literature review?

• A brief background of the problem or issue

• What has previously been done to address the problem or issue

• A description of what you will do in your project

• How this study will contribute to research on the subject

3. Why literature review is important?

The literature review is an important part of any research project because it allows the writer to look at previous studies on a topic and determine existing gaps in the literature, as well as what has already been done. It will also help them to choose the most appropriate method for their own study.

4. How to cite a literature review in APA format?

To cite a literature review in APA style, you need to provide the author's name, the title of the article, and the year of publication. For example: Patel, A. B., & Stokes, G. S. (2012). The relationship between personality and intelligence: A meta-analysis of longitudinal research. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(1), 16-21

5. What are the components of a literature review?

• A brief introduction to the topic, including its background and context. The introduction should also include a rationale for why the study is being conducted and what it will accomplish.

• A description of the methodologies used in the study. This can include information about data collection methods, sample size, and statistical analyses.

• A presentation of the findings in an organized format that helps readers follow along with the author's conclusions.

6. What are common errors in writing literature review?

• Not spending enough time to critically evaluate the relevance of resources, observations and conclusions.

• Totally relying on secondary data while ignoring primary data.

• Letting your personal bias seep into your interpretation of existing literature.

• No detailed explanation of the procedure to discover and identify an appropriate literature review.

7. What are the 5 C's of writing literature review?

• Cite - the sources you utilized and referenced in your research.

• Compare - existing arguments, hypotheses, methodologies, and conclusions found in the knowledge base.

• Contrast - the arguments, topics, methodologies, approaches, and disputes that may be found in the literature.

• Critique - the literature and describe the ideas and opinions you find more convincing and why.

• Connect - the various studies you reviewed in your research.

8. How many sources should a literature review have?

When it is just a chapter, sources should equal the total number of pages in your article's body. if it is a self-contained paper in itself, you need at least three times as many sources as there are pages in your work.

9. Can literature review have diagrams?

• To represent an abstract idea or concept

• To explain the steps of a process or procedure

• To help readers understand the relationships between different concepts

10. How old should sources be in a literature review?

Sources for a literature review should be as current as possible or not older than ten years. The only exception to this rule is if you are reviewing a historical topic and need to use older sources.

11. What are the types of literature review?

• Argumentative review

• Integrative review

• Methodological review

• Systematic review

• Meta-analysis review

• Historical review

• Theoretical review

• Scoping review

• State-of-the-Art review

12. Is a literature review mandatory?

Yes. Literature review is a mandatory part of any research project. It is a critical step in the process that allows you to establish the scope of your research, and provide a background for the rest of your work.

But before you go,

- Six Online Tools for Easy Literature Review

- Evaluating literature review: systematic vs. scoping reviews

- Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review

- Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

Competitive pricing on online markets: a literature review

- Research Article

- Open access

- Published: 14 June 2022

- Volume 21 , pages 596–622, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Torsten J. Gerpott 1 &

- Jan Berends 1

22k Accesses

8 Citations

Explore all metrics

Past reviews of studies concerning competitive pricing strategies lack a unifying approach to interdisciplinarily structure research across economics, marketing management, and operations. This academic void is especially unfortunate for online markets as they show much higher competitive dynamics compared to their offline counterparts. We review 132 articles on competitive posted goods pricing on either e-tail markets or markets in general. Our main contributions are (1) to develop an interdisciplinary framework structuring scholarly work on competitive pricing models and (2) to analyze in how far research on offline markets applies to online retail markets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Pricing Strategies in the Electronic Marketplace

Can online retailers escape the law of one price.

Platform Competition: Market Structure and Pricing

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Setting prices relative to competitors, i.e., competitive pricing, Footnote 1 is a classical marketing problem which has been studied extensively before the emergence of e-commerce (Talluri and van Ryzin 2004 ; Vives 2001 ). Although literature on online pricing has been reviewed in the past (Ratchford 2009 ), interrelations between pricing and competition were rarely considered systematically (Li et al. 2017 ). As less than 2% of high-impact journal articles address pricing issues (Toni et al. 2017 ), pricing strategies do not receive proper research attention according to their practical relevance. This research gap holds even more for competitive pricing. In the past, the monopolistic assumption that demand for homogeneous goods mostly depends on prices set by a single firm may have been a viable simplification since price comparisons were difficult. Today, consumer search costs Footnote 2 shrink as the prices of most goods can be compared on relatively transparent online markets. Therefore, demand is increasingly influenced by prices of competitors which therefore should not be ignored (Lin and Sibdari 2009 ).

In the early 1990s, few people anticipated that business-to-consumer (B2C) online goods retail markets Footnote 3 would develop from a dubious alternative to conventional “brick-and-mortar” retail stores to an omnipresent distribution channel for all kinds of products in less than two decades (Balasubramanian 1998 ; Boardman and McCormick 2018 ). In 2000, e-commerce accounted for a mere 1% of overall retail sales. In 2025, e-retail sales are projected to account for nearly 25% of global retail sales (Lebow 2019 ). Traditional offline channels are nowadays typically complemented by online technologies (Gao and Su 2018 ). With digitization of various societal sectors in general and the COVID-19 pandemic in particular, the shift toward online channels is unlikely to stop in the future. Besides direct online shops, two-thirds of e-commerce sales are sold through online marketplaces/platforms like Alibaba, Amazon or eBay (Young 2022 ). The marketplace operator acts as an intermediary (two-sided platform) who matches demand (online consumers) with supply (retailers). Whereas the retailer retains control over product assortment and prices, he has to pay a commission to the marketplace operator (Hagiu 2007 ). However, these intermediaries often act as sellers themselves, thereby posing direct competition to retailers who have to decide between direct or marketplace channels (Ryan et al. 2012 ).

Online consumer markets fundamentally differ from offline settings (Chintagunta et al. 2012 ; Lee and Tan 2003 ; Scarpi et al. 2014 ; Smith and Brynjolfsson 2001 ). Factors which make competition even more prevalent for online than for offline markets are summarized in Table 1 .

To date, a number of scholarly articles reviews various aspects of pricing under competition or online pricing (Boer 2015a ; Chen and Chen 2015 ; Cheng 2017 ; Kopalle et al. 2009 ; Ratchford 2009 ; Vives 2001 ). Vives ( 2001 ) provides an overview of the history of pricing theory and its evolution from the early work of Bertrand ( 1883 ) who studied a duopoly with unconstrained capacity and identical products to Dudey ( 1992 ) who set the foundation for today’s dynamic pricing Footnote 4 research with constrained capacities and a finite sales horizon. Ratchford ( 2009 ) reviews the influence of online markets on pricing strategies. Although he depicts factors shaping the competitive environment of online markets and compares online versus offline channels, he does not include competitive strategies specifically. This also holds for review papers on dynamic pricing which treat competition rather novercally (Boer 2015a ; Gönsch et al. 2009 ). With emphasis on mobility barriers, multimarket contact and mutual forbearance, Cheng ( 2017 ) studies competition mechanisms across strategic groups. Kopalle et al. ( 2009 ) discuss competitive effects in retail focusing on different aspects such as manufacturer interaction and cross-channel competition. To the best of our knowledge, Chen and Chen ( 2015 ) are the only scholars who review existing competitive pricing research by classifying model characteristics along product uniqueness (identical vs. differentiated), type of customer (myopic vs. strategic), pricing policy (contingent vs. preannounced) and number of competitors (duopoly vs. oligopoly). However, competition is only one of three pricing problems they analyze forcing them to reduce scope and depth and to exclude online peculiarities. In addition, significant competitive pricing contributions were published since 2015 (chapter 2.2). Overall, given the limitations of previous reviews of the pricing literature makes revisiting the current state of research a worthwhile undertaking.

Most often, competitive pricing literature uses simplifying assumptions limiting the applicability of presented models. The simplifications are required to circumvent challenges like the curse of dimensionality (Harsha et al. 2019 ; Kastius and Schlosser 2022 ; Li et al. 2017 ; Schlosser and Boissier 2018 ), endogeneity problems (Cebollada et al. 2019 ; Chu et al. 2008 ; Fisher et al. 2018 ; Villas-Boas and Winer 1999 ), uncertain information (Adida and Perakis 2010 ; e.g., Bertsimas and Perakis 2006 ; Chung et al. 2012 ; Ferreira et al. 2016 ; Keskin and Zeevi 2017 ; Shugan 2002 ) and simultaneity bias (Li et al. 2017 ). As a consequence, early work on pricing strategies with competition was restricted to theoretical discussions (Caplin and Nalebuff 1991 ; Mizuno 2003 ; Perloff and Salop 1985 ). This holds especially true in combination with other practical circumstances such as capacity constraints, time-varying demand or a finite selling horizon (Gallego and Hu 2014 ).

Armstrong and Green ( 2007 ) find empirical evidence that competitive pricing, especially for the sake of gaining market share, harms profitability. Similarly, some researchers cursorily ascribe competitor-based pricing as a sign of a poor management because it signals a lack of capabilities to set prices independently (Larson 2019 ). Revenue management researchers therefore often assume that monopoly pricing models implicitly capture the dynamic effects of competition. The so-called market response hypothesis is the key rationale to neglect the effects of competition altogether (Phillips 2021 ; Talluri and van Ryzin 2004 ). According to this reasoning, competition does not have to be considered as all relevant effects are already included in historical sales data. However, this intuitive argument can be easily rebutted as Simon ( 1979 ) already showed that price elasticities change over time. Furthermore, Cooper et al. ( 2015 ) study the validity of the market response hypothesis and conclude that this monopolistic view is rarely adequate. Monopolistic pricing models can only be applied to stable markets with little time-varying demand and little expected competitive reactions.

Detrimental outcomes of ignoring competition in pricing strategies are shown by Anufriev et al. ( 2013 ), Bischi et al. ( 2004 ), Isler and Imhof ( 2008 ), Schinkel et al. ( 2002 ), and Tuinstra (2004). The negative effects are even more harmful in fierce competitive settings such as situations with a high number of competitors or price sensitive customers (van de Geer et al. 2019 ). Empirical evidence on the influence of competition on pricing decisions is provided by Richards and Hamilton ( 2006 ) who find that retailers compete on price and variety for market share. Li et al. ( 2017 ) observe that competition-based variables explained 30.2% of hotel price variations in New York—compared to 22.3% attributed to demand-side variables. Similarly, Hinterhuber ( 2008 ) assesses competitor-based pricing as a dominant strategy from a practical perspective. Li et al. ( 2008 ) argue that because of its relevance, competition should be considered in operational revenue management and not be treated stepmotherly as an abstract strategic constraint.

Although striving to simplify pricing models is desirable, researchers should thus not simply ignore effects of competition on price setting in a non-monopolistic (online) world. Blindly pegging pricing strategies to competitors or undercutting competitors to gain market share may favor detrimental price wars and not profit-maximizing market structures. Nevertheless, no significant market player can operate isolated on online markets—decisions made always affect competing firms and consumer demand (Chiang et al. 2007 ). In such dynamic markets (chapter 3.3), competition must be considered with time-varying attributes (Schlosser et al. 2016 ).

Against this background, we suggest a conceptual framework to structure research covering competitive online pricing. It can serve scholars as a map to direct future research on the one hand and provide practicing managers with a guide to locate relevant pricing contributions on the other hand. Although the framework can be applied to a variety of markets with competitive dynamics, we concentrate our review on research covering B2C online goods retail markets. Thus, related research with a focus on auction pricing, multichannel peculiarities, behavioral pricing and multi-dimensional pricing approaches such as Everything-as-a-Service (XaaS) or bundle pricing is only assessed when findings are crucial to the competition-related discussion. In the remainder, we proceed as follows. The next chapter provides a descriptive overview of the competitive pricing literature for the subsequent discussion. Chapter 3 puts the identified literature into the perspective of online retail markets considering product and environmental characteristics. Section 4 concludes with practical implications and directions for future research.

Overview of competitive pricing research

Initially, properties of the reviewed literature are briefly summarized. Besides (a) the journal representation, (b) the historical development of online market considerations and (c) research domains, we classify research according to (d) the geographical and industry context as well as (e) research design and empirical foundation.

We identified relevant references through a semi-structured multi-pronged search strategy. Following Tranfield et al. ( 2003 ), we firstly screened the literature reviews mentioned in chapter 1 to obtain an overview of existing research streams. Second, we created a set of potentially relevant contributions by searching multiple keywords in the journal databases EBSCO, Scopus and Web of Science (c.f. Baloglu and Assante 1999 ). Footnote 5 Third, high-impact journals (see Appendix 1) in the academic fields economics, marketing management, and operations were screened. With focus on highly cited (> 10 citations in Scopus), recent (published later than 2000) research, we identified an initial sample of 996 unique papers. Fourth, we studied the abstract and skimmed the text of all papers for relevance to competitive online pricing, reducing our initial set to 174 papers. Fifth, we screened the references of the papers and identified literature cited which we not already included in our set. Sixth, especially for research areas with limited coverage in peer-reviewed journals, we uncovered gray literature through searches with Google Scholar. As a result, this study concentrates on papers published between 2000 and 2022 and only sparsely utilizes literature from the pre-internet era. The final sample of the papers with relevance to competitive B2C online pricing encompasses 132 entries. A complete list of the papers reviewed in great depth is provided in Appendix 2. 94% are peer-reviewed articles. Book chapters, conference papers and preprint/working papers each account for 2%.

Journal representation

Competitive pricing literature is widely dispersed over a broad range of journals as roughly half of the articles considered are from journals with less than three articles in our review. Notably, journals with a higher density of competitive pricing contributions are from the fields of operations, economics or are interdisciplinary. Table 2 reports the distribution of articles among the journals with the highest representation. In addition, it provides the considered articles subject to a content analysis in chapter 3.

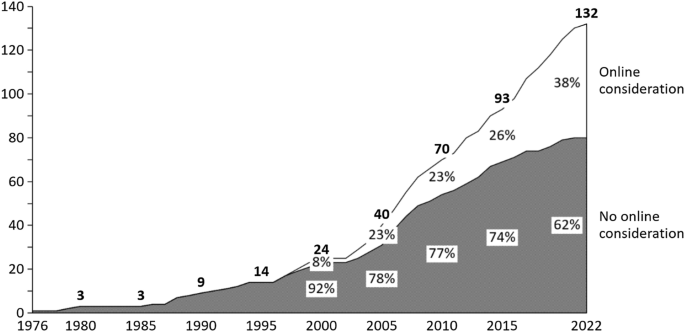

Online pricing contributions over time

Between 1976 and the end of the second millennium, the number of papers on competitive pricing in an internet context is naturally limited (Fig. 1 ). Parallel to the dissemination of online use among residential households, interest of researchers in online pricing in a competitive environment started to take off. 71.8% of the papers published from 2015 to 2022 consider online settings specifically. The corresponding statistic from 2000 to 2005 amounts to 43.8%.

Competitive pricing literature and its consideration of online peculiarities accumulated by year

Development of research domains

Competitive pricing literature typically can be assigned to one of the following research domains:

The economics domain takes a market perspective across individual firms. It elaborates on the existence and uniqueness of competitive equilibria also including all subjects regarding econometrics.

The marketing management domain analyzes competitive pricing problems from the perspective of a single firm with a focus on customer reactions to pricing decisions. It includes all subjects linked to marketing, strategy, business, international, technology, innovation, and general management.

The operations domain considers quantitative pricing solutions for, among others, quantity planning, choice of distribution channels, and detection of algorithm driven price collusion. It includes all subjects regarding computer science, industrial and manufacturing engineering, and mathematics.

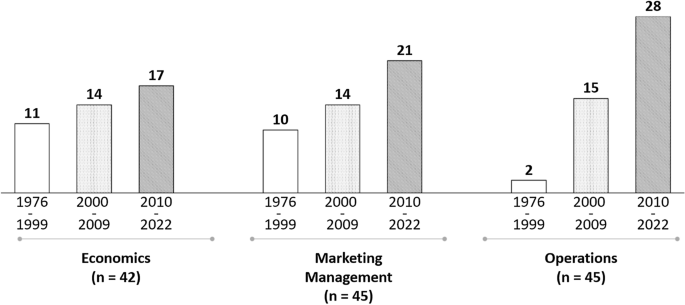

Separating the last 47 years of competitive pricing research into three intervals, all reviewed papers are assigned to their most affiliated research domain. Although the domains are similarly represented in our review (see Fig. 2 ), we see differences in their temporal change. Whereas rather theoretical economic subjects are covered relatively constant over time, more practice-oriented marketing management and operations subjects gained momentum since 2000. This suggests a shift from model conceptualization toward applicable research, frequently based on empirical data.

Distribution of competitive pricing literature over research domain and time interval

Geographical and industry context

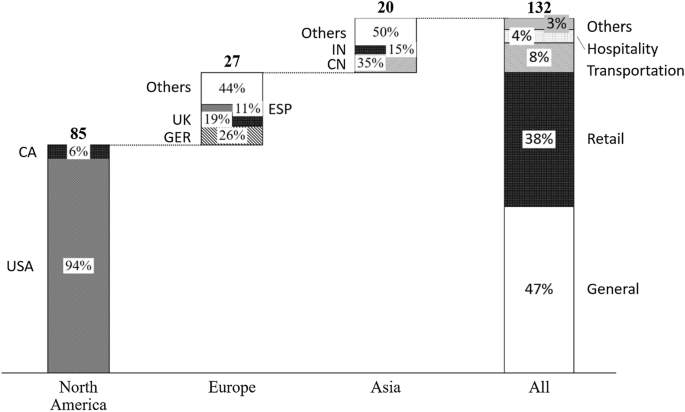

As the origin of revenue management lies in transportation and hospitality optimization problems, one could expect that competitive pricing research also originates in these dynamic sectors. However, our analysis reveals a different picture: Almost half of the papers in our review do not concentrate on a specific industry. Besides, most industry-specific competitive pricing articles focus on retail, with 38% concentrating on the retail industry versus 8% and 4% on transportation and hospitality, respectively (see Fig. 3 ). This supports our proposition in chapter 1 that effects of competition on industry-specific pricing are particularly relevant for online markets.

Competitive pricing research by focal industry and location of lead authors’ institution

Competitive pricing literature is predominantly driven by researchers employed by U.S. institutions (60%). The remaining 40% consist of Europe (19%), Asia (17%) and Canada (4%).

Research approach

A lack of empirical testing is an issue that hampers competitive pricing research. Liozu ( 2015 ) reported that only 15% of general pricing literature include empirical data. For competitive pricing, the situation appears even more aggravated. In addition to parameters such as price elasticities and stock levels of the company under study, comprehensive, real-time information of other market participants is crucial to add practical value.

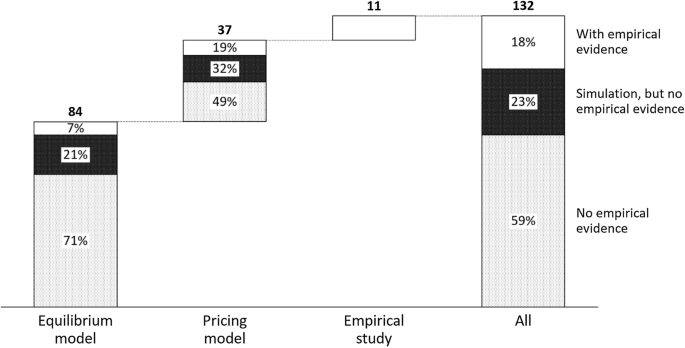

For instance, to solve a simple Bertrand equilibrium, Footnote 6 full information of all competitors is needed, which is rarely available in real-life settings. Therefore, many problems covered in the literature are of a theoretical nature. In accordance with Liozu ( 2015 ), we find that only 18% of reviewed articles use empirical evidence to validate hypotheses. An additional 23% strive to ameliorate this shortage through simulation data and numerical examples. The remaining 59% fail to bring any empirical evidence or numerical examples.

As can be taken from Fig. 4 , missing empirical support is particularly prevalent for equilibrium models which use empirical data in only 7% of all papers.

Competitive pricing research by research design and empirical validation

Competitive pricing on online markets

In this chapter, we assess the applicability of competitive pricing work to online markets. Typical characteristics of competitive B2C pricing models were derived from literature described in chapter 2. Competitive pricing literature can be classified along four characteristics depicted in Table 3 that form the market environment in which firms compete for consumer demand.

In the remainder of chapter 3, we discuss the four key questions in more depth and elaborate on their applicability to online retail markets.

Product similarity

In general, products in competitive pricing models are either identical (homogeneous) or differentiated by at least one quality parameter (heterogeneous). In case of homogeneous products, pricing is the only purchase decision variable—a perfectly competitive setting (Chen and Chen 2015 ). However, many firms strive to differentiate their products as this shifts the focus from the price as competitive lever to other product-related features (Afeche et al. 2011 ; Boyd and Bilegan 2003 ; Thomadsen 2007 ). According to Lancaster ( 1979 ), there are two types of product differentiation: vertical and horizontal differentiation. Vertical differentiation Footnote 7 encompasses all product distinctions which are objectively measurable and quantifiable regarding their quality level. Horizontal differentiation Footnote 8 can manifest in many variants and includes all product-related aspects which cannot be quantified according to their quality levels. Footnote 9 A key difference in the modeling of substitutable yet differentiated versus identical goods is that customers have heterogenous preferences among products. Footnote 10 A recent stream of literature approaches unknown differentiation criteria by assessing online consumer-generated content (DeSarbo and Grewal 2007 ; Lee and Bradlow 2011 ; Netzer et al. 2012 ; Ringel and Skiera 2016 ; Won et al. 2022 ).

Besides the chosen price level, Cachon and Harker ( 2002 ) argue that firms compete with the operational performance level offered and perceived, i.e., service level in online retail, to differentiate an otherwise homogenous offering. In situations, where resellers with comparable service and shipping policies offer similar products, price is a major decision variable for potential buyers (Yang et al. 2020 ). Often, e-tailers do not possess the right to exclusively distribute a certain product. For example, Samsung’s Galaxy S21 5G was offered by 69 resellers on the German price comparison website Idealo.de. Footnote 11 As some products in e-tail can be differentiated and others cannot, both identical and differentiated product research have their raison d’être for competitive online pricing.

Most competitive pricing models only address the effects of single-product settings. This simplification is reasonable if there is no interdependence between products of an e-tailer (Gönsch et al. 2009 ). Taking up on the smartphone example, the prices of close substitutes, such as Huawei’s P30 Pro, nonetheless have an impact on the demand of Samsung’s Galaxy S21 5G. To further extent product differentiation, price models have to incorporate multi-product pricing problems in non-cooperative settings (Chen and Chen 2015 ). Such models have to account not only for demand impact of directly competing products but also for synergies, cannibalization/substitution effects of (own) differentiated goods. Although there is a recent research stream regarding product assortment (Besbes and Sauré 2016 ; Federgruen and Hu 2015 ; Heese and Martínez-de-Albéniz 2018 ; Nip et al. 2020 ; Sun and Gilbert 2019 ), multi-product work is still underdeveloped. Thus, competitive multi-product pricing constitutes an area which should be addressed in future research.

Product durability

The durability of products is an important feature to differentiate between competitive pricing model types. Durable (non-perishable) products do not have an expiration date, for example consumer durables such as household appliances. Perishable products can only be sold for a limited time interval and have a finite sales horizon. After expiration date, unused capacity is lost or significantly devalued to a salvage value. Footnote 12 Combined with limited capacities, the firm objective is thus most often to maximize turnover under capacity constraints and finite sales horizon (Gallego and van Ryzin 1997 ; McGill and van Ryzin 1999 ; Weatherford and Bodily 1992 ).

Perishability can be of relevance for products with seasonality effects or short product life cycles (i.e., finite selling horizon) such as apparel, food groceries or winter sports equipment. This is especially relevant because online retailers of perishable products are severely restricted in their shipment, return handle policies and supply chain length (Cattani et al. 2007 ). Sellers cannot replenish their inventory after the planning phase and cannot retain goods for future sales periods (Perakis and Sood 2006 ). Some products like apparel—albeit reducing in value after a selling season—still have a certain salvage value and can be sold at reduced prices (Anand and Girotra 2007 ).

It depends on the type of product to decide whether perishability should be included in competitive pricing models. There is a fundamental distinction in the underlying optimization objective for models with or without perishability. Whereas models with perishable products tend to focus on revenue maximization over a definite short-term time horizon, models with durable products tend to focus on profit maximization over an indefinite or at least long-term time horizon by balancing current revenues of existing and future revenues of new customers. To account for this trade-off, models with durable products need to discount future cash flows incorporating time value of money, stock-keeping, opportunity and other costs related to prolonged sales (Farias et al. 2012 ). To conclude, perishability cannot be treated as an extension to durable models but rather as a separate class of pricing models. Depending on the product and/or setting in focus, both are relevant for online retailing. Further research could investigate the performance of models with and without consideration of perishability in various (online) settings to determine when it is appropriate to use which class of pricing models. Also, an interesting field of future studies arises around the question which instruments (e.g., service differentiations or price diffusion) are used by online retailers to differentiate otherwise homogeneous offerings.

Time dependence

A key differentiator of competitive pricing models is the consideration of either a static (time-independent) setup with definite equilibrium or a dynamic (time-dependent) constellation with changing environmental factors and equilibria. Albeit static pricing models have no time component, many consist of multiple stages to investigate the interplay of different factors. Footnote 13 In contrast, dynamic models allow for varying competitive (re-)actions over time. Footnote 14 Within the latter category, there are models with a finite (Afeche et al. 2011 ; Levin et al. 2008 ; Liu and Zhang 2013 ; Yang and Xia 2013 ) and an infinite (Anderson and Kumar 2007 ; Li et al. 2017 ; Schlosser and Richly 2019 ; Villas-Boas and Winer 1999 ; Weintraub et al. 2008 ) time horizon.

Historically, competitive pricing models assumed fixed prices over the considered time horizon. Limited computational power made it impossible to appropriately estimate models dynamically due to dimensionality issues (Schlosser and Boissier 2018 ). A lack of reliable demand information, high menu and investment costs to implement dynamic approaches were additional reasons why pricing models remained inherently static without incorporating changing competitive responses (Ferreira et al. 2016 ). The focus in retail has conventionally rather been on long-term profit optimization and to a lesser degree on dynamically changing price optimizations (Elmaghraby and Keskinocak 2003 ).

The literature disagrees on whether firms should opt for static or dynamic pricing strategies. A static environment allows to simplify and concentrate on a specific topic such as equilibrium discussions. For instance, Lal and Rao ( 1997 ) study success factors of everyday low pricing and derive conditions for a perfect Nash equilibrium between an everyday low price retailer and a retailer with promotional pricing. With Zara as an example for a company with a successful static pricing strategy, Liu and Zhang ( 2013 ) argue that with the presence of strategic customers who prolong sales in anticipation of price decreases, firms might even be better off to deploy static over dynamic price setting processes. Studying the time-variant pricing plans in electricity markets, Schlereth et al. ( 2018 ) suggest that consumers might prefer static over dynamic pricing because of factors like choice confusion, lack of trust in price fairness, perceived economical risk or perceived additional effort. Further support for a static pricing strategy is found in Cachon and Feldman ( 2010 ) and Hall et al. ( 2009 ).

Nevertheless, to generalize that static should strictly be preferred over dynamic pricing models could be short-sighted. Firms cannot generally infer future behavior of competitors from past observations to assess how competitive (re-) actions may influence the optimal pricing policy (Boer 2015b ). Corresponding to the surge of revenue management systems in the airline industry during the 70s and 80s, increased price and demand transparency, low menu costs and an abundance of decision support software created fierce competition among online retailers (Fisher et al. 2018 ). Taking up on the above mentioned example by Liu and Zhang ( 2013 ), Caro and Gallien ( 2012 ) show that even Zara does not solely rely on static pricing. They supported Zara’s pricing team in designing and implementing a dynamic clearance pricing optimization system—to generate a competitive advantage in addition to the fast-fashion retail model Zara mainly pursues (Caro 2012 ). Zhang et al. ( 2017 ) discuss various duopoly pricing models with static and dynamic pricing under advertising. They find that market surplus is highest when one firm prices dynamically, profiting from the static behavior of the other. Chung et al. ( 2012 ) provide numerical evidence that a dynamic pricing model with an appropriately specified demand estimation always outperforms static pricing strategies—also in settings with incomplete information. Xu and Hopp ( 2006 ) show that dynamic pricing outperforms preannounced pricing, especially with effective inventory management and elastic demand. Further support for advantages of dynamic pricing can be found by Popescu ( 2015 ), Wang and Sun ( 2019 ), and Zhang et al. ( 2018b ). Empirical evidence of the negative consequences of sticking to a static strategy in a changing environment is found in the cases of Nokia, Kodak, and Xerox.

While some scholars distinguish between discrete and continuous dynamic pricing systems (Vinod 2020 ), we suggest to classify dynamic pricing models according to their level of sophistication into two evolutionary stages: the (in e-commerce widely applied) manual rule-based pricing approach and the data-driven algorithmic optimization approach (Popescu 2015 ; Le Chen et al. 2016 ). Footnote 15 For the rule-based approach, “if-then-else rules” are defined and updated manually. Footnote 16 However, the mere number of stock-keeping units (SKUs) in today’s retailer offerings aggravate the initial setup and handling of rule-based pricing and make real-time adjustments unmanageable (Schlosser and Boissier 2018 ). In addition, rule-based approaches are rather subjective than sufficiently data-driven. Faced with a large range of SKUs, competitor responses and heterogeneous demand elasticities, canceling out the human decision-making process on an operational level is the next evolutionary step for competitive pricing systems (Calvano et al. 2020 ). Data-driven algorithmic pricing strategies use observable market Footnote 17 data to predict sales probabilities based on consumer demand and competitive responses (Schlosser and Richly 2019 ).

As online marketplaces benefit from an increased number of retailers on their platforms, they typically support sellers to establish automated dynamic pricing systems (Kachani et al. 2010 ). Footnote 18 However, Schlosser and Richly ( 2019 ) claim that current dynamic pricing systems are not able to deal with the complexity of competitor-based pricing and therefore most often ignore competition altogether or solely rely on manually adjusted rule-based mechanics. Challenges include the indefinite spectrum of changing competitor strategies, asymmetric access to competitor knowledge, a large solution space under limited information and the black-box character of dynamic systems, which exacerbates an intervention in case of a pricing system malfunction. Besides, researchers did not yet identify an algorithm which consistently outperforms other methodologies in competitive situations. Instead, it depends on the specific setting and other competitors’ pricing behavior to assess which pricing algorithm is optimal (van de Geer et al. 2019 ) exacerbating the application of such systems.

Reflecting the literature findings for both static and dynamic pricing strategies, we conclude that pricing managers should develop dynamic pricing models in most e-commerce situations. As long as demand and competitor price responses vary over time on online markets, dynamic models are naturally superior to time-independent approaches. Static models on the other hand are only appropriate in market constellations with little time-varying demand and competitor behavior. As static research can be expected to remain a vivid field of literature, further research with regard to the transferability of static models to dynamic settings is desirable. In addition, more research is needed that helps to better understand the implications of widely applied rule-based dynamic pricing methods and their transition toward algorithmic approaches (Boer 2015a ; van de Geer et al. 2019 ; Kastius and Schlosser 2022 ; Könönen 2006 ).

Market structure

The market structure describes the number of competing firms such as duopoly or oligopoly in a demand setting with an indefinite number of consumers. 60% of the reviewed papers studied duopolies, 49% oligopolies, 7% monopolistic competition, and 3% perfect competition. Footnote 19

Especially for research in the economics stream, many papers assume a perfectly competitive market. Pricing research with perfectly competitive markets (e.g., van Mieghem and Dada 1999 or Yang and Xia 2013 ) is likely to be of very limited value to online retailers. Building on the notion of Diamond ( 1971 ), Salop ( 1976 ) argues that if customers have positive information gathering costs, no perfect competition can occur as firms have room to slightly increase prices without losing demand. Christen ( 2005 ) found evidence that even with strong competition and low information costs, cost uncertainty could decrease the detrimental effect of competition for sellers and could increase prices above Bertrand levels. Similarly, Bryant ( 1980 ) showed that perfect competition is not possible in a market with uncertain demand, even if the number of firms is large and customers have no search costs. Rather, price dispersion reflects uncertain demand (Borenstein and Rose Nancy L. 1994 ; Cavallo 2018 ; Clemons et al. 2002 ; Obermeyer et al. 2013 ; Wang et al. 2021 ). Israeli et al. ( 2022 ) empirically show that the market power of individual firms does not only depend on the number and intensity of competitors but also on the firm’s ability to adjust prices in response to varying inventory levels of product substitutes, especially with low consumer search costs. This is of relevance for e-commerce as e-tailers could exploit this dependence by incorporating competitors’ stock levels into pricing decisions (Fisher et al. 2018 ).

Some papers discuss (quasi) monopolistic competition (e.g., Xu and Hopp 2006 ) in which small firms charge the (higher) monopoly price rather than the (lower) competitive price. From an empirical study in the U.S. airline industry, Chen (2018) concludes that, as firms can price discriminate late-arriving consumers, competition is softened, profits are increased, and the only single-price equilibrium could be at the monopoly price. This supports Lal and Sarvary ( 1999 ) who show that online retailers enjoy a certain amount of monopoly power in cases where buyers cannot switch suppliers for repeated purchases (e.g., technical incompatibility reasons). In such cases, switching costs could increase online prices (Chen and Riordan 2008 ). However, this contradicts Deck and Gu ( 2012 ) who empirically show that, although the distribution of buyer values of competing products might theoretically lead to higher prices through competition, intensity of competition rarely allows for an occurrence of this phenomenon in e-tail settings.

Although duopoly settings can serve to assess the relevant strength of pricing strategies, which is not directly possible for oligopoly markets due to the curse of dimensionality (Kastius and Schlosser 2022 ), they cannot be transferred to more competitive environments (van de Geer et al. 2019 ). In online retail, a duopoly market structure is a rare exemption. Like for perfectly competitive markets, findings of duopoly research must be carefully assessed in terms of their applicability to online retail oligopolies.

Bresnahan and Reiss ( 1991 ) found empirical evidence that markets with an increasing number of dealers have lower prices than in less competitive market structures such as monopolies or duopolies. Although applicable to many online retail markets, where retailers face dozens, if not hundreds of thousands of competitors (Schlosser and Boissier 2018 ), few research attention is currently given toward a structure with a large number of competitors in an imperfect market (cf. Li et al. 2017 ). A way to assess the current competitive structure of markets is the utilization of online consumer-generated content such as forum entries (Netzer et al. 2012 ; Won et al. 2022 ) or clickstream data (Ringel and Skiera 2016 ) and actual sales data (Kim et al. 2011 ).