Sustainable Development and Social Responsibility—Volume 1 pp 299–316 Cite as

Towards an Understanding of the Sources of Sustainable Competitive Advantage: A Literature Review and Conceptual Framework

- Nihal El Daly 22

- Conference paper

- First Online: 12 February 2020

1320 Accesses

1 Citations

Part of the book series: Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation ((ASTI))

While the concept of sustainable competitive advantage is pivotal to firm success and the subject of much debate in the literature, empirical research investigating it is limited, and few frameworks reflect the divergence of perspectives on the matter. This article aims to advance the understanding of the sources of sustainable competitive advantage by critically spanning a large part of the literature on this subject and synthesizing the findings in a conceptual framework. The review covers perspectives starting from the industry-based explanations of industrial economists such as Porter ( 1980 ) to the resource-based explanations favoured by many such as Barney ( 1991 ), to more market-oriented views (Day 1994 ; De Wit and Meyer 2005 ). The Resource Based View (RBV) is discussed in detail as making a key contribution to developing and delivering competitive advantage (Chaharbaghi and Lynch 1999 ). The research also covers the more recent insights from the Dynamic Capabilities Thinking, inspired by the rising pressure on businesses to evolve rapidly in an increasingly complex and dynamic environment, reinforcing the importance of the firm’s ability to renew its resources and capabilities in light of market dynamics (Tondolo and Bitencourt 2014 ). The resulting conceptual framework will be empirically tested and further addressed in subsequent work.

- Sustainable competitive advantage

- Advantage-creating resources

- The resource based view

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Ram Charan, Strategy Execution Workshop, Fairmont Hotel, Cairo, Egypt, 11th August 2008.

Ambrosini, V., & Bowman, C. (2009). What are dynamic capabilities and are they a useful construct in strategic management? International Journal of Management Reviews, 11 (1), 29–49.

Article Google Scholar

Ambrosini, V., Bowman, C., & Collier, N. (2009). Dynamic capabilities: An exploration of how firms renew their resource. British Journal of Management, 20 (S1), 9–24.

Amit, R., & Schoemaker, P. J. (1993). Strategic assets and organisational rent. Strategic Management Journal, 14 (1), 33–46.

Barney, J. B. (1986). Strategic factor markets: Expectations, luck, and business strategy. Management Science, 32, 1231–1241.

Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17 (1), 99–120.

Breznik, L., & Lahovnik, M. (2014). Renewing the resource base in line with the dynamic capabilities view: A key to sustainable competitive advantage in the IT industry. JEEMS, 19 (4), 453–485.

Chaharbaghi, K., & Lynch, R. (1999). Sustainable competitive advantage: Towards a dynamic resource-based strategy. Management Decision, 37 (1), 45–50.

Collis, D. J., & Montgomery, C. A. (1995). Competing on resources. Harvard Business Review , 119.

Google Scholar

Conner, K. (1991). A historical comparison of resource-based theory and five schools of thought within industrial organisation economics: do we have a new theory of the firm? Journal of Management, 17 (1), 121–154.

Day, G. S. (1994). The capabilities of market-driven organisations. The Journal of Marketing , 37–52.

De Wit, B., & Meyer, R. (2005). Strategy synthesis: Resolving strategy paradoxes to create competitive advantage . London, UK: Thomson Learning.

Eisenhardt, K., & Martin, J. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21, 1105–1121.

Fahy, J. & Smithee, A. (1999). Strategic marketing and the resource-based view of the firm. Academy of Marketing Science Review , 10 . Retrieved from http://www.amsreview.org/articles/fahy10-1999.pdfarticles/fahy10-1999.pdf .

Fahy, J. (2000). The resource-based view of the firm: some stumbling blocks on the road to understanding sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of European Industrial Training , 24 (2/3/4), 94–104.

Grant, R. (1991). The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation. California Management Review, 33 (3), 114–135.

Grant, R. (1996). Toward a knowledge-based theory of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 17 (S2), 109–122.

Halawi, L. A., Aronson, J. E. & McCarthy R. V. (2005). Resources-based view of knowledge management for competitive advantage. The Electronic Journal of Knowledge Management , 3 (2), 75–86. Retrieved from www.ejkm.com .

Helfat, C. E., Finkelstein, S., Mitchell, W., Peteraf, M., Singh, H., Teece, D., et al. (2007). Dynamic capabilities: understanding strategic change in organisations . Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Hoffman, N. (2000). An examination of the “sustainable competitive advantage concept”: Past, present and future. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 2000, 1.

Hooley, G., & Broderick, A. (1998). Competitive positioning and the resource-based view of the firm. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 6, 97–115.

Hooley, G., Greenley, G., Fahy, J., & Cadogan, J. (2001). Market focused resources, competitive positioning and firm performance. Journal of Marketing Management, 17, 503–520.

Hooley, G., & Greenley, G. (2005). The resource underpinnings of competitive positions. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 13 (2), 93–116.

Hosseini, Akram Sadat, Soltani, Sanaz, & Mehdizadeh, Mohammad. (2018). Competitive advantage and its impact on new product development strategy (Case study: Toos nero technical firm). Journal of Open Innovation: Technology Market and Complexity, 2018 (4), 17.

Hult, G. T. M. (2003). An integration of thoughts on knowledge management. Decision Sciences, 34 (2).

Hult, G. T. M., & Ketchen, D. J. (2001). Does market orientation matter? A test of the relationship between positional advantage and performance. Strategic Management Journal, 22, 899–906.

Ketchen, D., Hult, T., & Slater, S. (2007). Toward greater understanding of market orientation and the resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 28, 961–964.

Kohli, A. K., & Jaworski, B. J. (1990). Market orientation: The constructs, research propositions and managerial implications. Journal of Marketing, 54, 1–18.

Kumar, V., Jones, E., Venkatesan, R., & Leone, R. P. (2011). Is market orientation a source of sustainable competitive advantage or simply the cost of competing? Journal of Marketing, 75, 16–30.

Lippman, S. A., & Rumelt, R. P. (1982). Uncertain imitability: An analysis of interfirm differences in efficiency under competition. The Bell Journal of Economics, 13, 418–438.

Lubit, R. (2001). Tacit knowledge and knowledge management: The keys to sustainable competitive advantage. Organizational Dynamics, 29 (4), 164–178.

Milfelner, B., Gabrijan, V. & Snoj, B. (2008). Can marketing resources contribute to company performance? Organizacija , 41 (1).

Morgan, R. M., & Hunt, S. D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing, 58, 20–38.

Murray, P. (2002). Knowledge management as a sustained competitive advantage. Ivey Business Journal, 66 (4), 71–76.

Narasimha, S. (2000). Organizational knowledge, human resource management, and sustained competitive advantage: Toward a framework. Competitiveness Review , 10 (1).

Nguyen, Q. T. N, Neck, P. A & Nguyen, T. H. (2009). The critical role of knowledge management in achieving and sustaining organizational competitive advantage. International Business Research , 2 (3).

Peteraf, M. A. (1993). The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based view. Strategic Management Journal, 14, 179–191.

Pisano, Gary P. (2017). Towards a prescriptive theory of dynamic capabilities: connecting strategic choice, learning and competition. Industrial and Corporate Change, 26 (5), 747–762.

Porter, M. E. (1980). Competitive strategy: Techniques for analyzing industries and competitors . New York, NY: Free Press.

Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance . New York, NY: Free Press.

Porter, M. E. (1986). Competitive strategy: Harvard business school press.

Porter, M. E. (1996). What is strategy? Harvard Business Review , Nov-Dec.

Prahalad, C. K. & Hamel, G. (1990). The core competence of the corporation. Harvard Business Review .

Reed, R., & DeFillippi, R. J. (1990). Causal ambiguity, barriers to imitation and sustainable competitive advantage. Academy of Management Review, 15 (1), 88–102.

Ritthaisong, Y., Johri, L. M., & Speece, M. (2014). Sources of sustainable competitive advantage: The case of rice-milling firms in Thailand. British Food Journal, 116 (2), 272–291.

Rumelt, R. P. (1987). Theory, strategy, and entrepreneurship. The Competitive Challenge, 137, 158.

Sigalas, C. & Economou, V. P. (2013). Revisiting the concept of competitive advantage: Problems and fallacies arising from its conceptualization. Journal of Strategy and Management, 6 (1), 61–80.

Srivastava, R., Fahey, L., & Christensen, H. K. (2001). The resource-based view and marketing: The role of market-based assets in gaining competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 27, 777–802.

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18 (7), 509–533.

Tondolo, V. A., & Bitencourt, C. (2014). Understanding dynamic capabilities from its antecedents, processes, and outcomes. Brazilian Business Review, 11 (5), 122–144.

Tuominen, M., Matear, S., Hyvonen, S., Rajala, A., Moller, K., Kajalo, S., & Hooley, G. J. (2005). Market driven intangibles and sustainable performance advantages. In AMA Winter Educators’ Proceedings .

Vorhies, D., & Morgan, N. (2005). Benchmarking marketing capabilities for sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Marketing, 69 (1), 80–94.

Weerawardena, J. (2003). The role of marketing capability in innovation-based competitive strategy. Journal of Strategy Marketing, 11, 15–35.

Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5 (2), 171–180.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to convey sincere appreciation to Dr Khaled Wahba for his continuous guidance and supervision of the doctoral work that inspired this article.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Maastricht School of Management, Maastricht, The Netherlands

Nihal El Daly

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nihal El Daly .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Dubai International Academic, American University in the Emirates, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Miroslav Mateev

School of Business, Slippery Rock University, Slippery Rock, PA, USA

Jennifer Nightingale

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper.

El Daly, N. (2020). Towards an Understanding of the Sources of Sustainable Competitive Advantage: A Literature Review and Conceptual Framework. In: Mateev, M., Nightingale, J. (eds) Sustainable Development and Social Responsibility—Volume 1. Advances in Science, Technology & Innovation. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32922-8_30

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32922-8_30

Published : 12 February 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-32921-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-32922-8

eBook Packages : Earth and Environmental Science Earth and Environmental Science (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Sustainability as the Source of Competitive Advantage. How Sustainable is it?

Creating a Sustainable Competitive Position: Ethical Challenges for International Firms

ISBN : 978-1-80455-252-0 , eISBN : 978-1-80455-249-0

ISSN : 1876-066X

Publication date: 2 October 2023

As reaching UN Sustainable Development Goals 2030 has become the top agenda of the global companies, they have prioritized sustainability as a response to the grand challenges as well as a potential source of competitive advantage. This chapter poses the question: whether and how can firms achieve a sustainable competitive advantage via sustainability? I critically examine the sustainability-based view of sustainable competitive advantage by arguing that in the changing global landscape we will need to re-think the accepted ideas as regards sustainability goals, sustainable development and the sustainable competitive advantage as the individual firm’s achievement. The chapter contributes to the ongoing debate by discussing the potential of de-growth ideas and principles to solve some of the contradictions and suggesting the questions for future research.

- Sustainability

- Sustainable competitive advantage

- Sustainable cooperative advantage

- Embedded sustainability

- Stakeholders

Tarnovskaya, V. (2023), "Sustainability as the Source of Competitive Advantage. How Sustainable is it?", Ghauri, P.N. , Elg, U. and Hånell, S.M. (Ed.) Creating a Sustainable Competitive Position: Ethical Challenges for International Firms ( International Business and Management, Vol. 37 ), Emerald Publishing Limited, Leeds, pp. 75-89. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1876-066X20230000037005

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2023 Veronika Tarnovskaya

This work is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of these works (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode .

1. Introduction

In recent years, sustainability has gained increased attention from academics and practitioners alike. The growing relevance of sustainability is reflected by the actions of global and European organizations such as the United Nations with its 2030 Agenda and Sustainable Development Goals, 1 not to mention the growing grassroots movements such as ‘Fridays for Future’. Sustainability is expected to prevail as a critical megatrend affecting companies (as well as consumers) in the decades to come ( Lichtenthaler, 2021 ). Because of these developments, companies need to be prepared to tackle grand challenges such as climate change, poverty, migration and health (pandemics) as well as the recently intensified political instability in the world ( Buckley et al., 2017 ).

Overall, the growing focus to address these challenges has brought sustainability to the top of companies’ strategic agendas. For example, global multinationals (MNEs) such as Hennes & Mauritz (H&M) with its vision ‘to lead the change towards a circular and renewable fashion industry, while being a fair and equal company’ ( H&M, 2018b ) pledged to use 35% of recycled materials by 2025, responding to one of the greatest ecological challenges of waste created by the fashion industry. Similarly, Apple announced in 2020 the goal to become 100% carbon neutral by 2030, including its supply chain and product life cycle 2 while IKEA has pledged its commitment to become climate positive by 2030

by reducing more greenhouse gas emissions than the IKEA value chain emits, while growing the IKEA business. This is how we contribute to limiting the global temperature increase to 1.5°C by the end of the century. ( IKEA Sustainability Report, 2021 )

All these examples of large MNEs show that sustainability has, in fact, become a key determinant of future business success. Beyond MNEs, there are multiple examples of small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and start-ups pursuing sustainability goals and adapting their business models to sustainability. In this chapter, I will use the broad definition of sustainability as defined by the United Nations – ‘meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs’. 3 In their 2030 Agenda, the United Nations have developed the Sustainable Development Goals and the concept of sustainable development in alignment with the triple bottom line of environmental, social and financial performance ( Elkington, 2018 ). Many companies have started sustainability initiatives not only as a response to the grand challenges outlined above but because the logic for performance accounting comprises a broader spectrum which also considers the mitigation of negative externalities ( Tarnovskaya et al., 2022 ). According to the analysis of the literature concerning the impact of corporate sustainability on financial performance, 78% of studies in top-tier journals found a positive relationship between corporate sustainability and a firm’s financial performance ( Alshehhi et al., 2018 ). As expressed in one of the studies, ‘the impact of sustainability practices on firm performance is growing over time and is expected to grow further in the coming years’ ( Govindan et al., 2020 , p. 13).

Following from the arguments above, sustainability initiatives may provide a critical source of competitive advantage for diverse types of firms, but especially MNEs, due to the global supply chains, economies-of-scale, vast resource base, access to innovative technologies, the public scrutiny they are exposed to and a more educated workforce. MNEs such as IKEA, H&M, Apple, Lego to name a few have historically found the key source of their sustainable competitive advantage in their strong brands (all these companies have been listed as one of the hundred best brands for decades 4 ). Most recently, they have also reached high rankings as the best sustainable brands, for example, IKEA being ranked by consumers as the number one sustainable brand in Sweden. 5 Whether this current development means that MNEs use both strong brands and sustainability to compete successfully or whether sustainability has been raised to the level of the business’s strategic agenda, its role as the source of competitive advantage that can be maintained rather than simply achieved is still poorly understood.

The aim of this chapter is to examine the viability of sustainability as a source of sustainable competitive advantage for global firms facing multiple challenges in the volatile, dynamic environments they operate in. The research question is: whether and how can firms achieve a sustainable competitive advantage via sustainability? The text presented below is of a conceptual nature, but I will use multiple examples of MNE’s sustainability endeavours from secondary sources and illustrate my points by observations from an in-depth case study of H&M sustainability implementation in Bangladesh.

I will argue that there are inherent contradictions in the very idea of sustainable competitive advantage via sustainability as it constitutes unresolved tensions such as the triple bottom line of competing goals and sustainable development through perpetual growth. Besides, when sustainability is raised to the level of industry standards, one single firm cannot maintain its sustainable competitive advantage alone. When collaboration with competing firms becomes critical for raising and maintaining new environmental, social and technological standards, the cooperative ( Morioka et al., 2017 ) advantage might be a more beneficial aim.

I will critically examine the sustainability-based view of sustainable competitive advantage by arguing that in the changing global landscape we will need to re-think many of the accepted ideas as regards sustainability goals (components), sustainable development as the strategy to ‘end poverty and other deprivations, improve health and education, reduce inequality, and spur economic growth’ 6 and the sustainable competitive advantage as an individual firm’s achievement. The chapter also contributes to the ongoing debate by discussing the potential of de-growth ideas and principles to solve some of the contradictions and suggest the questions for future research.

The empirical data presented in this chapter provide examples of MNEs’ sustainability endeavours from secondary sources as well as selected primary sources from an in-depth case study of H&M sustainability implementation in Bangladesh conducted by our research team in 2020. Five digital interviews were carried out with managers from sustainability, environmental and social teams operating in Bangladesh. The questions to local managers concerned their attitudes to sustainability programmes, mismatches between operations and strategy and stories about how sustainability projects have unfolded. We have used corporate social responsibility (CSR) and sustainability documents as well as news articles and reports from the business press, as anchor points for the questions (e.g. H&M, 2018a , 2018b , 2019a , 2019b ). Various documents explaining the MNE’s sustainability approaches have offered detailed knowledge regarding the sustainability work, including knowledge on how sustainability activities are organized and implemented, relationships with different stakeholders, different ethical codes, etc. The interviews were transcribed and analysed together with the documents using conceptually clustered matrix coding techniques and pattern matching recommended by Miles and Huberman (1994) . The NVIVO 12 software package was used to catalogue, collect and sort both the interview transcripts and the secondary data sources.

In the text below, I have used selected examples from these interviews to illustrate analytical points such as of sustainable solutions as the sources of cooperative (instead of competitive) advantage that MNEs increasingly pursue on a global scale. I have also complemented H&M examples from the in-depth case study with secondary sources featuring H&M Group as well as other companies: Bohinj ECo Hotel, Ikea, Lego, Patagonia, Alpa. These additional examples were chosen due to these companies’ track-records in sustainability (Ikea, Lego and Patagonia) as well as their embedded sustainability approach (Bohinj ECo Hotel and Alpa) and their elements of de-growth (Fairfone, Alpa and Patagonia). The empirical examples are used primarily to illustrate various aspects related to sustainability as competitive advantage.

3. Sustainability as the Source of Competitive Advantage. How Sustainable is it?

The origins and history of the sustainability concept can be traced as far back as the enlightenment era with its concern for the preservation of life. The post-modern idea of sustainability emerges from the conditions specific to the time and space of postmodernity, where life has become endangered to such an extent that ‘nature has taken over the old religions’ fundamental function of having an unquestionable authority that can impose limits’ ( Zizek, 2008 , pp. 53–54). Conceptually understood in management literature as the triple bottom line, sustainability consists of environmental sustainability defined as ‘a condition of balance, resilience, and interconnectedness that allows human society to satisfy its needs while neither exceeding the capacity of its supporting ecosystems to regenerate the services necessary to meet those needs nor by our actions diminishing biological diversity’ ( Morelli, 2011 , p. 6); social sustainability – universal human rights, liveable communities and basic needs for many people ( Lichtenthaler, 2021 ) and economic sustainability – activities and systems supporting long-term economic growth by enabling communities worldwide to keep their independence and access to resources without negative social and environmental consequences ( Elkington, 2018 ). As seen from these definitions, the economic sustainability goals go beyond financial indicators and measures since they include such indicators as quality of life, social cohesion and sound environment for people ( Spangenberg, 2005 ). Besides, the environmental, social and economic components of sustainability are interdependent as they provide opportunities/challenges for each other.

It is not hard to see that the triple bottom line of three sets of interdependent goals presents a serious challenge for companies trying to implement all of them without sacrificing one or another. In practice, many companies treat sustainability as a ‘business case’ by focussing the sustainability programmes on their value chain, key stakeholders, critical markets (e.g. human rights, workplace safety, labour norms in the supply chain) while pursuing less ambitious goals for other stakeholders. Depending on the degree of convergence of business and social interests, companies can function as good corporate citizens, attuned to evolving societal concerns or mitigate the adverse effects of corporate activities. The most important feature of this approach is the reconciliation of societal impact and business effectiveness through the creation and implementation of social projects for a company’s competitive positioning.

Historically, the term ‘sustainable competitive advantage’ described a firm’s superior attributes and resources that its competitors were unable to imitate ( Barney et al., 1989 ) and the assets that lasted for an extended period ( Porter, 1985 ). Barney (1991) defines competitive advantage as

the implementation of a value creating strategy which is not simultaneously being implemented by any current or potential competitors; whereas sustainable competitive advantage is viewed as an implementation of a value-creating strategy not simultaneously being implemented by any current or potential competitors and when these other firms are unable to duplicate the benefits of this strategy. ( Barney, 1991 , p. 102)

While Barney (1991) saw the sources of sustainable competitive advantage in resources that are rare, inimitable, un-substitutable and un-codifiable, Chaharbaghi and Lynch (1999) argued that the essence of sustainable competitive advantage is firms’ capabilities ( Teece et al., 1997 ) in producing core competencies – in other words, ways to produce and utilize resources in the dynamic and fast-changing environment. However, when the sources of core competencies are possible to imitate, for example, by sharing the knowledge on how to make the production process more sustainable across the industry, the sustainability of a competitive advantage might become questionable.

I will use the H&M case to provide examples of sustainable solutions to further argue that they might constitute the source of cooperative (instead of competitive) advantage that MNEs increasingly pursue on a global scale. I will start by arguing that in times of crisis MNEs might be forced to prioritize social/environmental goals over the economic ones.

3.1. H&M – Prioritizing Social Goals When Crisis Comes

A particularly good example of using sustainable solutions as cooperative advantage is H&M. H&M is pursuing its sustainable strategy of ‘leading the change towards circular and climate positive fashion while being a fair and equal company’ across its value chain of 1,603 tier one suppliers, 708 tier two suppliers employing 1.56 million people and 153,000 employees in approx. 5,000 stores. The company has achieved remarkably high rankings in the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (ranked fourth in 2020), the Dow Jones European Index, the highest possible score for human rights, environmental reporting, social reporting and materiality, the highest score in the fashion industry for supply chain management (92/100) and strategy for emerging markets (56/100).

According to the financial newspaper Dagens Industri: ‘H&M Group was ranked as the most sustainable consumer goods company in an assessment of listed companies in Sweden by Dagens Industri and Aktuell Hållbarhet’. These figures and facts show a strong competitive position achieved by the company if we limit the focus only to sustainability. It has been consistently ranked as one of the 50 best global brands by Interbrand and one of the Top 50 Global Retailers by NTF, 7 proving that its competitive standing has been sustainable for more than a decade (slightly decreasing in 2021). All that despite the numerous accusations of bad working conditions at its factories in Cambodia and Bangladesh, child labour in Uzbekistan, safety issues at factories in Cambodia and Bangladesh and low living wages in Bangladesh. Most of the reported incidents have led to concrete measures being taken by the sustainability teams at H&M. Nevertheless, the controversies remain (the latest one is the usage of forced labour at its factories in Xinjiang in China – accusations in 2021).

The most recent situation in the world when Russia started the brutal war in Ukraine de-stabilizing the European and worldwide political, economic and social order has led many global companies to leave the Russian market. As of 9 April 2022, more than 600 companies had withdrawn from Russia or freed themselves from Russian ties in protest at Russian actions. 8 H&M is one of these companies – on 2 March 2022, they announced that its 150 stores would be closed. H&M cited that it stands ‘with all the people who are suffering’ in Ukraine as well as for ‘the safety of customers and colleagues’ in Russia. 9 Russia was H&M’s sixth-biggest market at the time, representing 4% of group sales in the fourth-quarter of 2021. 10

In this respect, it seems relevant to discuss the role of external factors such as the changes of market dynamics in maintaining sustainability as the foundation of competitive advantage. As emphasized by Lichtenthaler (2021) , the radical changes in the competitive environment, business and/or political environment, might deem the sustainability-based competitive advantage unsustainable. In the situation of global crisis or war in one of the markets, the global firm needs to prioritize some of its sustainability goals more than others, as seen in the H&M and other MNEs’ statements and actions due to the situation of Russian aggression. More specifically, the economic goals were not seen as being of utmost importance as the retailer’s expected loss was estimated to be around 190M USD.

According to the analyst Richard Chamberlain, the profit estimates for H&M for this year and next year will decrease by about 10% due to both its Russian store closures and the slowdown in central and eastern Europe. 11 As H&M was one of the firms who followed the exodus from Russia rather than started it, the foundations of the firm’s superior performance (along the economic and the social axis) might be weakened.

3.2. H&M – Sustainable Solutions Via Collaboration

H&M also provides a particularly good example of collaborative sustainability solutions together with other global brands to solve the grand challenge – to ensure good working conditions and improved wages in the markets with underdeveloped labour laws such as Bangladesh. Fair wages are one of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. H&M has created a roadmap to reach this objective: ‘ Every garment worker should earn enough to live on’ – the initial implementation of the Fair Living Wage Roadmap . However, ensuring living wages for workers in supplier factories has been challenging. Firstly, since H&M does not own or manage the factories, the company does not pay garment workers’ salaries and cannot, therefore, decide how much they are paid. Secondly, workers have limited possibilities to negotiate wages collectively using union representatives. In addition to these challenges, H&M often faces the situation that factories normally are contracted by varied brands.

In their Fair Wage project, H&M managers elevated the wage issue to industry level to engage concerned stakeholders as well as governments to promote systemic change. One example of a crucial collaboration for H&M was the formation of ACT – Action, Collaboration, Transformation – formed in 2015 together with the global union organization IndustriALL and 22 other global brands. The mission of ACT is to transform the garment, textile and footwear industry and achieve living wages for workers through collective bargaining at industry level. ACT provides a framework through which all relevant actors, including brands and retailers, trade unions, manufacturers and governments, can exercise their responsibility and role in achieving living wages. ACT represents ‘an innovative solution, in terms of being the first time 22 companies in the industry get together and agree on improvements regarding issues related to living wages’ and this is the collective solution of the leading brands in the industry. In an interview, the CEO of H&M ( H&M, 2013 ) pointed out that to create a sustainable fashion industry, one company cannot make lasting and systemic change alone.

The examples of H&M’s sustainable solutions highlight another important aspect of achieving a sustainable competitive advantage via sustainability. Firms which have integrated sustainability in their business operations (sustainable business models) formulate their business success differently from the firms which have added sustainability issues to their current business-as-usual ( Morioka et al., 2017 ). Their success is about solving a social and/or environmental problem that requires a joint effort with competitors to find an innovative sustainability solution. For these firms, a cooperative (or cooptative) advantage is critical for business survival ( Morioka et al., 2017 ) and it implies a broader view of advantage derived from the competition and collaboration with competitors. The firms taking the sustainability business model path also define the performance differently – not as a financial success for shareholders but as a broader sustainable value creation for multiple stakeholders, deeming obsolete the view of competitive advantage as a path to superior financial value.

What follows is that the foundation of sustainability needs renewal and reconfiguration while performance outcomes of sustainability need to be specified. As argued in the literature, besides purely financial measures of firm performance, the triple bottom line considers various performance indicators capturing the social and environmental dimensions ( Alhaddi, 2015 ; Elkington, 2018 ) which might at different time periods create high social and environmental value but lead to negative financial effects (lower economic value). Overall, the sustainability view of competitive advantage calls for rethinking the whole idea of the competitive advantage through the superior value creation by a single firm focussing better than competitors on economic value and customers’ satisfaction. Instead, firms aiming at integrating sustainability into their business models need to extend their value propositions to all stakeholders, employ proactive problem-solving, engage stakeholders and collaborate rather than compete with competitors.

3.3. Bohinj ECo Hotel – Embedded Sustainability

The literature uses the concept of embedded sustainability as the incorporation of environmental and social value into the company’s core business with no trade-off in price or quality (i.e. with no social or green premium) ( Laszlo & Zhexembayeva, 2017 ). Unlike CSR initiatives or efforts to add social and environmental issues at the margins of the core business, embedded sustainability offers new pathways to enduring profits via stakeholder value creation.

Embedded sustainability goes much further than just adding sustainability to some parts of a company’s operations and/or having sustainability as separate from the core business strategy. The embedded sustainability is also more than just a balancing act in which economic interests are traded off against social and environmental targets. Embedded sustainability is the incorporation of environmental, health and social value into the company’s core business with the goal to pursue sustainable value for multiple stakeholders including customers, suppliers, employees as well as NGOs and regulators with whom the sustainable solutions are co-developed for system-level changes. This is achieved via a transformation of core business processes across all levels of the value chain, offering ‘smarter’ solutions with no trade-offs in quality and no social or green premium ( Laszlo & Zhexembayeva, 2017 ).

An exceptionally good example of such a business is the first complete eco-hotel in Eastern Europe – Bohinj ECo Hotel. 12 Bohinj ECo Hotel is the first and only Green Globe-certified hotel in Slovenia, recognized among the best of the sustainable hotels in the world. Instead of focussing on marginal environmental attributes such as usual eco-efficiency practices, the hotel has embedded environmental thinking and performance into all its operations. Combining geothermal and co-generation technologies, the hotel produces its own energy for all hotel operations, including its aquapark. Water is continuously recycled, and heat reused. Wall and window insulation in combination with the energy-efficient LED lighting allows for the highest levels of comforts at reasonable costs. The hotel generates 17.22 kg of CO 2 per guest per night compared with 174.82 kg produced by ‘standard’ hotels in the region. The savings from energy expenses are channelled into other activities of the hotel such as food and catering, allowing the company to produce superior performance without a price premium.

In the next section, I will discuss a more radical alternative to sustainable development and firms’ strategies – the idea and concept of de-growth. This concept challenges the basic assumption of sustainability as ‘a business case’ with the growth imperative.

4. Can De-growth Lead to a Competitive Advantage?

In this part, I would like to question the very idea of sustainable development as the strategy to ‘end poverty and other deprivations, improve health and education, reduce inequality, and spur economic growth’ 13 from the perspective of de-growth.

The term ‘de-growth’ (‘decroissance’ in French) was used for the first time by French intellectual Ander Gorz in 1972. He posed a question that remains at the centre of the de-growth Google scholar debate: ‘Is the earth’s balance, for which no-growth – or even de-growth – of material production is a necessary condition, compatible with the survival of the capitalist system?’ (Gorz, 1972 in Kallis et al., 2012 ). With the advent of neo-liberalism in the 1980s and 1990s, the interest in growth and de-growth declined while in the beginning of 2002 it came back when Bruno Clementin and Vincent Cheynet coined the term ‘sustainable de-growth’, understood as sustainable development. Since 2008, the English term has entered academic discourse reflecting the activities of the French-founded academic collective Research & De-growth and leading to more than 100 publications and several special issues ( D’Alisa et al., 2015 ; Kallis et al., 2012 ).

The meaning of de-growth is not very transparent and hardly popular among economists as the prefix de-creates negative connotations of stagnation rather than development. De-growth signifies a critique of growth as the central goal of the capitalist system reflected in gross domestic product, increased consumption and commodification of all spheres of human life, including the social ones. De-growth challenges the whole capitalist system based on growth and profit maximization. De-growth signifies a different growth with ‘smaller metabolism’, the usage of fewer natural resources and different organization of society on such principles as sharing, simplicity, conviviality, care and commons (collectives and communities) ( D’Alisa et al., 2015 ; Kallis et al., 2012 ). Put briefly, de-growth does not call for doing less of the same but doing things differently (it is not about making an elephant leaner but turning it into a snail) ( D’Alisa et al., 2015 ; Kallis et al., 2012 ).

The proponents of de-growth strongly argue for the incompatibility of sustainable development and economic growth, and more generally, of sustainable development and capitalism. As argued, ‘history suggests that it is highly unlikely that nations with capitalist economies would voluntarily choose not to grow’ ( D’Alisa et al., 2015 , p 10). As capitalism is represented by a specific range of institutions – the corporation, private property, waged labour, private credit and money at an interest rate – involved in the continuous struggle for profit accumulation, de-growth literature does not usually discuss what might happen to these institutions during de-growth transition. Instead, it includes diverse types of non-profit institutions and projects such as eco-communities, digital commons, communities of back-to-the landers, cooperatives, urban gardens, time banks, barter markets and healthcare associations.

De-growth at its core is a grassroots movement and among its practices are fast-growing consumer movements against consumerism and MNEs’ ethical practices, especially in their production countries. A recent survey in France showed that 27% of respondents want to consume less – double the percentage from two years earlier ( Roulet & Bothello, 2020 ). The number of people eating less meat or giving it up completely has been rising exponentially in recent years, too. Such movements as the Flygskam (‘flight shaming’ in Swedish) have grown in Sweden and it has even led to reduced pollution in 2019–2020. In the apparel industry, garment manufacturers like H&M are aware of the growing consumer criticism of the ecological impact of fast fashion. These examples show that consumers (in developed countries) are increasingly conscious of the negative consequences of consumerism and are changing their habits. As argued, ‘we are witnessing the emergence of consumer-driven de-growth’ ( Roulet & Bothello, 2020 ).

These consumer stories clearly show that de-growth opens new opportunities for companies – even within the present capitalist system – if they embrace consumer trends and/or disruptive technologies. For example, in Sweden and Scandinavia, the growth and popularity of Flygskam has created a boost for train travel and companies like SJ. The reduced meat and dairy consumption have led to the rise of meat substitutes and non-dairy products like Oatly, boosting the respective company’s competitive standing. What follows is that de-growth might reshuffle competitive dynamics within and across industries and even present new opportunities for competitive advantage ( Roulet & Bothello, 2020 ).

4.1. De-growth Strategies for Competitive and Cooperative Advantage

In this section, I will outline strategies available for firms that pursue sustainability via de-growth. Three different strategies identified in the literature ( Roulet & Bothello, 2020 ) can provide sources of competitive advantage for private firms. I have placed these strategies in a spectrum between the endpoints of competition and cooperation to argue that the more extensive is the shift towards the basic principles of de-growth: sharing, simplicity, conviviality, care, commons (broad stakeholder engagement) and the broad stakeholder value of the offerings – the stronger is the cooperative spirit of the business and its focus on the cooperative (rather than competitive) advantage.

Firstly, firms can pursue de-growth-adapted product design , involving the creation of products with longer lifespans via a modular or local production ( Roulet & Bothello, 2020 ). Fairphone – the sustainable smartphone produced by a company from the Netherlands with a strong community of supporters – avoids the built-in obsolescence practised by most mobile manufacturers such as Apple and Samsung and produces repairable phones having a dramatically extended longevity. 14 Similarly, the start-up – the 30-Year Sweatshirt under the Tom Cridland brand 15 – sells high-quality, durable products that refute the fast fashion principles. Alpa – the Swedish company 16 – has sustainability as the core value and business principle. They produce ‘timeless garments that withstand time’, long-lasting and practical, ecologically produced from carefully chosen yarns in Peru. All garments can be repaired free of charge and sold after use in the company’s online store.

Secondly, firms engage in value-chain repositioning , where they might skip certain stages of the value chain and even delegate some tasks to stakeholders ( Roulet & Bothello, 2020 ). The vehicle manufacturer Local Motors created a proof-of-concept recyclable vehicle crafted with 50 individual parts printed onsite, compared with 25,000 parts required for a traditional vehicle. The company crowdsourced designs and crowdfunded the project from their potential consumers. Larger firms such as IKEA and Lego have also modified their value chains, launching marketplaces for either creating innovative designs or trading used products as well as involving customers in product delivery and design. These firms have already incorporated stakeholder engagement into their operations and, therefore, they will be faster to adapt to de-growth when it becomes more mainstream.

Thirdly, firms can lead through de-growth-oriented standard setting ( Roulet & Bothello, 2020 ). This involves the creation of a standard for the rest of the industry to follow. The apparel company Patagonia – that explicitly follows an ‘antigrowth’ strategy – is the best example of this approach, offering a second-hand store and providing free repairs not only for their own products but also for those of other manufacturers. Walmart and Nike have requested advice from Patagonia on such practices, and more recently, H&M initiated the service with a pilot in-store repair facility. Similarly, the automobile company Tesla released all its patents in 2014, in an attempt to catalyse the diffusion of electric vehicles. Such initiatives were not merely marketing tactics, but also strategies to standardize a practice or technological platform throughout an industry in which companies like Patagonia or Tesla would have the best expertise.

5. Concluding Thoughts on Sustainability as a Source of Sustainable Advantage

In this section, I will summarize the insights from the previous discussion and illustrative cases and answer the question: whether and how can a sustainable competitive advantage be achieved by firms via sustainability? I have tried to probe this question through critical examination of the sustainability view of competitive advantage by arguing that sustainable development as such has been suggested as a global solution for the mounting global challenges that our societies are increasingly facing, and therefore, sustainability has developed from being the single firms’ response to the external pressures to their conscious, proactive and joint role in the radical change of business-as-usual. When sustainability is elevated from being an add-on to the ‘normal’ business to the embedded mode, it requires the joint efforts of companies, industries and stakeholders. Given its joint character and firms’ co-dependence on each other’s success, sustainability cannot be the source of sustainable competitive advantage but sustainable cooperative advantage.

In Table 1 , I have provided examples of different strategic aspects of sustainability leading to competitive and/or cooperative advantage. It shows that when sustainability is added to the business-as-usual (which is in other parts unsustainable), it might lead a firm to a combination of competitive/cooperative advantage which is unsustainable. Both firms pursuing the growth imperative and firms partly embracing de-growth are still coping with the conflicting economic and non-economic goals and they need to be profitable to implement these other goals. On the contrary, the firms that have embedded sustainability in their core business process become profitable because they have succeeded in the pursuit of sustainable value, which requires the whole transformation of the business ethics, relationships with stakeholders, competitors and other firms in the industry. In doing so, they can achieve a sustainable cooperative advantage.

The Strategic Aspects of Sustainability Leading to Competitive and Cooperative Advantage.

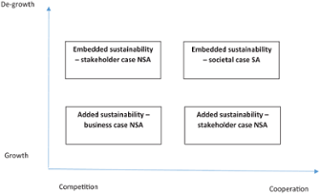

In Fig. 1 , I have placed different options for reaching the competitive/cooperative advantage via sustainability along the axis of growth – de-growth and competition – collaboration. I am arguing here that there are two ways of pursuing sustainability – to add it to the existing business model or fully embed it into the business operations by implementing a radically different business model with sustainability in focus. This can be achieved within the traditional growth-oriented and competition-based paradigm of capitalism (added sustainability as business case) as well as the alternative de-growth-oriented and collaboration-based paradigm of prosperity without growth imperative (embedded sustainability – societal case). However, only in the case of de-growth and collaborative approach (top right corner in Fig. 1 ) can sustainability become the source of sustainable (cooperative) advantage that can contribute to both businesses and societies as well as benefit the planet. There are also sideways options: to focus on the competition while pursuing de-growth and cooperating while growing. In both latter cases, sustainability will be achieved partially as it requires different trade-offs and, because of that, cannot lead to the sustainable advantage.

When Does Sustainability Become a Sustainable Advantage? NSA – Non-sustainable advantage. SA – Sustainable advantage.

Achieving sustainable cooperative advantage via sustainability can be achieved only via decoupling of economic goals from social and environmental ones when the latter goals become central while profits follow as stakeholders ‘reward’ firms by prioritizing their goods and services. The literature talks about decoupling of economic and social/environmental goals in the context of different approaches to sustainability as well as in the context of de-growth ( Tarnovskaya et al., 2022 ). It seems to me that a fruitful conclusion of this chapter is to come to similar ideas by dis-connecting sustainability from the established postulates of sustainable competitive advantage. I would like to end this chapter by saying that there will be plenty of examples of firms using sustainability as the way to over-compete with their rivals, position or reposition their brands and conquer market shares but we will also see examples of firms that will cooperate rather than compete and create innovative offerings of a sustainable value that won’t simply meet the growing concerns of customers and other stakeholders but, first and foremost, will solve the burning environmental problems, decrease the level of inequality in the world, improve lives of millions of poor people and even reverse climate change.

THE 17 GOALS | Sustainable Development ( un.org ).

Apple commits to be 100% carbon neutral for its supply chain and products by 2030 – Apple.

https://interbrand.com/best-global-brands/

https://www.sb-index.com/sweden

https://sdgs.un.org/goals

https://www.rankingthebrands.com

Sonnenfeld (2022) .

‘Ukraine conflict: Growing numbers of firms pull back from Russia’. BBC News , March 6, 2022.

https://en.wikipedia.org

H&M sales soar but shares slip on wider Ukraine impact concern | BoF ( businessoffashion.com ).

https://www.bohinj-eco-hotel.si/

https://www.fairphone.com/en/story/

https://www.tomcridland.com

https://alpaknitwear.se/hallbarhet/

Alhaddi, 2015 Alhaddi , H. ( 2015 ). Triple bottom line and sustainability: A literature review . Business and Management Studies , 1 ( 2 ), 6 – 10 .

Alshehhi, Nobanee, & Khare, 2018 Alshehhi , A. , Nobanee , H. , & Khare , N. ( 2018 ). The impact of sustainability practices on corporate financial performance: Literature trends and future research potential . Sustainability , 10 , 494 . https://doi.org/10.3390/su10020494

Barney, 1991 Barney , J. B. ( 1991 ). Firm resources and sustainable competitive advantage . Journal of Management , 17 , 99 – 120 .

Barney, Mc Williams, & Turk, 1989 Barney , J. B. , Mc Williams , A. , & Turk , T. ( 1989 ). On the relevance of the concept of entry barriers in the theory of competitive strategy . [Presentation] Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Strategic Management Society, San Francisco . https://www.academia.edu/28159566/On_the_relevance_of_the_concept_of_entry_barriers_in_the_theory_of_competitive_strategy

Buckley, Doh, & Benischke, 2017 Buckley , P. J. , Doh , J. P. , & Benischke , M. H. ( 2017 ). Towards a renaissance in international business research? Big questions, grand challenges, and the future of IB scholarship . Journal of International Business Studies , 48 ( 9 ), 1045 – 1064 .

Chaharbaghi, & Lynch, 1999 Chaharbaghi , K. , & Lynch , R. ( 1999 ). Sustainable competitive advantage: Towards a dynamic resource-based strategy . Management Decision , 37 ( 1 ), 45 – 50 .

D’Alisa, Demaria, & Kallis, 2015 D’Alisa , G. , Demaria , F. , & Kallis , G. ( 2015 ). Degrowth: A vocabulary for a new era . Routledge .

Elkington, 2018 Elkington , J. ( 2018 ). 25 years ago I coined the phrase “Triple Bottom Line.” Here’s why it is time to rethink it ( hbr.org ). Harvard Business Review, June , 2018.

Govindan, Sidhartha, Rupesh, & Patif, 2020 Govindan , K. , Sidhartha , A. , Rupesh , S. , & Patif , K. ( 2020 ). Supply chain sustainability and performance of firms: A meta-analysis of the literature . Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review , 137 , 1 – 22 . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tre.2020.101923 .

H&M, 2013 H&M . ( 2013 ). H&M conscious actions. Sustainability report 2013 . https://hmgroup.com/investors/reports/

H&M, 2018a H&M . ( 2018a ). H&M group annual report 2018 . Retrieved January 30, 2020, from https://hmgroup.com/

H&M, 2018b H&M . ( 2018b ). H&M group sustainability report 2018 . Retrieved September 11, 2020, from https://hmgroup.com/sustainability

H&M, 2019a H&M . ( 2019a ). H&M group annual report 2019 . Retrieved January 30, 2020, from https://hmgroup.com/

H&M, 2019b H&M . ( 2019b ). Sustainability performance report 2019 . Retrieved from February 8, 2021, https://hmgroup.com/sustainability

IKEA Sustainability Report, 2021 IKEA Sustainability Report . ( 2021 ). Retrieved from https://www.ikea.com/se/sv/files/pdf/cb/66/cb66310d/ikea-sustainability-report-final.pdf

Kallis, Kerschner, & Martinez-Alier, 2012 Kallis , G. , Kerschner , C. , & Martinez-Alier , J. ( 2012 ). The economics of degrowth . Ecological Economics . http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.08.01

Laszlo, & Zhexembayeva, 2017 Laszlo , C. , & Zhexembayeva , N. ( 2017 ). Embedded sustainability. The next big competitive advantage . Routledge .

Lichtenthaler, 2021 Lichtenthaler , U. ( 2021 ). Why being sustainable is not enough: Embracing a net positive impact . Journal of Business Strategy , 44 ( 1 ), 13 – 20 . https://doi.org/10.1108/JBS-09-2021-0153

Miles, & Huberman, 1994 Miles , M. B. , & Huberman , A. M. ( 1994 ). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook . Sage Publications .

Morelli, 2011 Morelli , J. ( 2011 ). Environmental sustainability: A definition for environmental professionals . Journal of Environmental Sustainability , 1 ( 1 ), Article 2. https://doi.org/10.14448/jes.01.0002 . http://scholarworks.rit.edu/jes/vol1/iss1/

Morioka, Bolis, Evans, & Carvalho, 2017 Morioka , S. N. , Bolis , I. , Evans , S. , & Carvalho , M. M. ( 2017 ). Transforming sustainability challenges into competitive advantage: Multiple case studies kaleidoscope converging into sustainable business models . Journal of Cleaner Production , 167 , 723 – 738 .

Porter, 1985 Porter , M. E. ( 1985 ). The competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance . Free Press .

Roulet, & Bothelleo, 2020 Roulet , T. , & Bothelleo , J. ( 2020 , February). Why “de-growth” shouldn’t scare businesses . Harvard Business Review . https://hbr.org/2020/02/why-de-growth-shouldnt-scare-businesses

Sonnenfeld, 2022 Sonnenfeld , J. ( 2022 , 22 March). Over 300 companies have withdrawn from Russia – But some remain . Yale School of Management . Retrieved March 10, 2022. from https://som.yale.edu/story/2022/over-1000-companies-have-curtailed-operations-russia-some-remain

Spangenberg, 2005 Spangenberg , J. H. ( 2005 ). Economic sustainability of the economy: Concepts and indicators . International Journal of. Sustainable Development , 8 ( 1–2 ), 47 – 64 .

Tarnovskaya, Tolstoy, & Melén Hånell, 2022 Tarnovskaya , V. , Tolstoy , D. , & Melén Hånell , S. ( 2022 ). Drivers or passengers? A taxonomy of multinationals’ approaches to corporate social responsibility implementation in developing markets . International Marketing Review , 39 ( 7 ), 1 – 24 . https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-05-2021-0161

Teece, Pisano, & Shuen, 1997 Teece , D. J. , Pisano , G. , & Shuen , A. ( 1997 ). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management . Strategic Management Journal , 18 ( 7 ), 509 – 533 .

UN Sustainable Development Goals UN Sustainable Development Goals | United Nations Development Programme ( undp.org )

Zizek, 2008 Zizek , S. ( 2008 ). Violence: Six sideways reflections . Picador .

Book Chapters

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The literature review demonstrates the varied points of view existing regarding the sources of sustainable competitive advantage ever since the concept appeared until present days. Two prominent theories of competitive advantage, were summarised, compared and contrasted, namely Porter's market view and the resource-based view.

This study aims to find out how the development of research related to sustainability competitive advantage that has been carried out so far and to find research gaps that can be used in the future related to the field of sustainability competitive advantage. This research was conducted using the systematic literature review method with the ...

In this literature review, the relationship between sustainability innovations and firm competitiveness is investigated. ... in order for them to adapt to rapidly changing competition and market demands and to be able to create a sustained competitive advantage ... A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model ...

A Systematic Literature Review: Determinants of Sustainable Competitive Advantage. CC BY-NC 4.0. In book: Proceedings of the Fifth Annual International Conference on Business and Public ...

Historically, the term 'sustainable competitive advantage' described a firm's superior attributes and resources that its competitors were unable to imitate ( Barney et al., 1989) and the assets that lasted for an extended period ( Porter, 1985 ). Barney (1991) defines competitive advantage as.

Sustainable Competitive Advantage: A Literature Review and Future Research Arizal Liwafa1*, Bagong2, Zuyyinna Choirunnisa3 1,2,3 Postgraduate School Universitas Airlangga, Indonesia ... LITERATURE REVIEW Abubakar et al., (2022) and Pratono, (2022) explain that strategic management has the ultimate goal of being able to realize competitive ...

This study is the first literature review that presents GCA management. The results show that the application of green innovation and high environmental awareness led to the development of improved performance, a better competitive advantage, and sustainable business. This study highlights significant theoretical and practical contributions.

Literature review. Competitive Advantage (CA) is a business's ability to create more economic value than competitors. CAs can be sustainable or temporary. ... Mahdi, O. R., Nassar, I. A., & Almsafir, M. K. (2019). Knowledge management processes and sustainable competitive advantage: An empirical examination in private universities. Journal of ...

Business Strategy and the Environment is a sustainable business journal ... competitive advantage that has been carried out so far and to find research gaps that can be used in the future related to the field of sustainability competitive advantage. This research was conducted using the systematic literature review method with the help of ...

2. Literature review Competitive Advantage (CA) is a business's ability to create more economic value than competitors. CAs can be sustainable or temporary. For most organisations, CA is achieved temporarily. However, if the organisation's competitors cannot imitate or replicate that

In-Depth Review An in-depth review was conducted to obtain an understanding of GCA to answer the research questions. This review included five sections, namely (1) green innovation and GCA, (2) green intellectual capital and GCA, (3) GCA and sustainability, (4) GCA construct, and (5) further research opportunities. 4.3.1.

While the concept of sustainable competitive advantage is pivotal to firm success and the subject of much debate in the literature, empirical research investigating it is limited, and few frameworks reflect the divergence of perspectives on the matter. This article aims to advance the understanding of the sources of sustainable competitive advantage by critically spanning a large part of the ...

Sustainable competitive advantage (SCA) is very important for companies in analyzing the quality of human resources and the company's environment that continues to change. Besides that, SCA is also able to provide short-term revenue increases and product advantages to customers. This research aims to map the topic of SCA in various scientific fields by visualizing it into a landscape map to ...

This is a preliminary study of the sustainable competitive advantage literature that includes the concept of strategic leadership as a knowledge management processes enabler for achieving a ...

to reconcile the other theories. The literature review suggests that the sustainability of competitive advantage is a valid concept even when the firms face environmental changes. Keywords: Sustainable Competitive Advantage, Resource-based View, Dynamic Capabilities, Ambidexterity TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.

From the data obtained, research on the topic of Sustainability Competitive Advantage tends to experience significant growth in its publications. The determinant factors of Sustainable Competitive ...

It is against this backdrop that this review paper aims to synthesize the literature on competition, competitiveness, and competitive advantage in HEIs. We examine the existing research spanning the years 2012-2022, highlighting the increasing scholarly interest in these concepts within HE, and identifying possible directions for future studies.

The systematic review of literature on sustainable tourism. The trade-off between sustainability and competitiveness. The main challenges of sustainable tourist development. New insights for the strengthening of competitiveness of sustainable tourism. The future research guidelines are set based on analysis performed.

cater this requirement. The literature was searched using „Google Scholar‟, for „any time‟, with frame „measure sustainable competitive advantage‟, where 21(15 effective) articles were found; and with frame „measure sustained competitive advantage‟ 19 (11 effective) articles were found. It was found that

Therefore, the objective of this paper is to review and analyze relevant literature in order to determine whether the HR practices can be considered as a real source of sustainable competitive ...

Sustainable Competitive Advantage(SCA) can be achieved by a company when the company has valuable, unique resources that cannot be imitated, and its attributes cannot be substituted so that it is only at the level of competitive advantage (CA).(Mahdi et al., 2019). ... Bibliometricsvery useful in systematic literature review research to combine ...

Key-Words: - Sustainable Competitive Advantage; VOSViewer; Bibliometrics; Systematic Literature Review Received: June 4, 2022. Revised: September 9, 2023. Accepted: October 7, 2023. Available online: November 13, 2023. 1 Introduction Sustainable Competitive Advantage (SCA) refers to an organization's ability to maintain its superior

In modern times, it has come to the realization of organizations that acquiring knowledge and using it in an effective manner is the only way to have a sustainable competitive advantage (SCA) in ...

However, in the sustainability literature, BDA's role in enabling sustainable FSC innovations is not explored. Thus, this study investigates how data-driven analytics might improve FSC innovation by adopting creative tactics in every triple bottom line (TBL) component - green, corporate social responsibility (CSR), and financial - to gain a ...