- About This Site

- What is social theory?

- Habermas/Parsons

- Frankfurt School

- Inequalities

- Research Students

- Dirty Looks

- Latest Posts

- Pedagogy & Curriculum

- Contributors

- Publications

Select Page

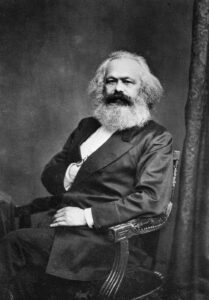

What did Marx mean by Thesis Eleven?

Posted by Mark Murphy | Aug 10, 2013 | Theory | 2

Thesis Eleven is the most famous of Karl Marx’s Theses on Feuerbach , and goes like this:

The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point, however, is to change it.

As well as being the most famous thesis it is also arguably the most misinterpreted of Marx’s statements generally, up there with ‘ Property is theft ’ (which was Marx quoting Proudhon , unfavourably). I sometimes get the impression that people who use the phrase have some variant of ‘act first, ask questions later (if at all)’ in their head when they use it. I may be wrong on that assumption (hard to tell), but this is certainly not the meaning intended by Marx when he went to work on Feuerbach and then later Max Stirner in The German Ideology . Instead Marx’s real target was the perceived need (then and now) to deliver some kind of objective philosophical justification/legitimation for engagement with acts of social struggle (against oppression, exploitation, colonialism etc).

An excellent explanation of Marx’s thinking around Thesis Eleven is provided by Cornel West in his book The ethical dimensions of Marxist thought (highly recommended). In the chapter ‘Marx’s adoption of radical historicism’, West argues that Thesis Eleven

was not a rejection of rational dialogue, discourse, or discussion, nor is it a call for blind activism (West, p. 68).

Rather, Thesis Eleven was a statement of Marx’s desire to situate philosophical thinking about social problems within history rather than outside it – Marx, not for the first time, flipping conventional wisdom on its head. Thesis Eleven itself was the inevitable outcome of a process begun earlier in the Theses, most notably in Theses Six & Seven, where Marx made clear his shift from philosophy to radical historicism, or what West refers to as the ‘move from philosophic aims and language to theoretic ones’:

This means that fundamental distinctions such as objectivism/relativism, necessary/arbitrary, or essential/accidental will no longer be viewed through a philosophic lens. That is, no longer will one be concerned with arriving at timeless criteria, necessary grounds, or universal foundations for philosophic objectivity, necessity, or essentiality. Instead, any talk about objectivity, necessity, or essentiality must be under-a-description, hence historically located, socially situated and “a product” of revisable, agreed-upon human conventions which reflect particular needs, social interests, and political powers at a specific moment in history. The task at hand then becomes a theoretic one, namely, providing a concrete social analysis which shows how these needs, interests, and powers shape and hold particular human conventions and in which ways these conventions can be transformed (West, p. 67).

For Marx, theorising social change went hand-in-hand with an understanding of social change as inevitably being ‘under-a-description’ as West puts it (great phrase). Thesis Eleven, then, is the culmination of this thinking, providing a succinct indication of the consequences of the radical historical shift for social struggle, a shift that assumes that

the heightened awareness of the limitations of traditional philosophy will soon render that philosophy barren, a mere blind and empty will-to-nothingness. In its place will thrive a theory of history and society, able to account for its own appearance and status, aware of the paradoxes it cannot solve, grounded in ever changing personal needs and social interests, and beckoning for action in order to overcome certain conditions and realize new conditions. In this way, the radical historicist viewpoint enables Marx to make the philosophic to theoretic shift without bothering his philosophic conscience (West, p. 68).

Marx then went on to have a right go at Max Stirner in The German Ideology (two-thirds of the book were devoted to Stirner’s The ego and its own , itself a partial critique of Marx). A radical historicist vs. a radical psychologist – they don’t make debates like that anymore, do they?

About The Author

Mark Murphy

Mark Murphy is a Reader in Education and Public Policy at the University of Glasgow. He previously worked as an academic at King’s College, London, University of Chester, University of Stirling, National University of Ireland, Maynooth, University College Dublin and Northern Illinois University. Mark is an active researcher in the fields of education and public policy. His research interests include educational sociology, critical theory, accountability in higher education, and public sector reform.

Related Posts

Narrative inquiry as intersubjective understanding

March 15, 2014

Digital citizenship: creating a deliberative pedagogical context

May 17, 2014

Introducing Institutional Ethnography for Research in Education

January 8, 2021

What do we mean by social justice?

October 31, 2015

Hi Mark, Is the phrase ‘under-a-description’ like an operational definition? Could you say a bit more about that and why you like it. Thanks

Marx said , masturbation is philosophical sex . But such an act doesn’t produce children , and you cannot philosophically grow carrots . I would argue Marx saw his world as theorizing , where as philosophers merely interpreted the actions of others , from what I’ve read of Marx he tired of philosophy not long after tiring of religion and spent his life working on political economy and other subjects .

Recent Posts

Theses On Feuerbach 1938 translation of Marx’s original

Source : MECW Volume 5, p. 3; Written : by Marx in Brussels in the spring of 1845, under the title “1) ad Feuerbach”; This version was first published in 1924 — in German and in Russian — by the Institute of Marxism-Leninism in Marx-Engels Archives, Book I, Moscow. First Published : the English translation was first published in the Lawrence and Wishart edition of The German Ideology in 1938.

1) ad Feuerbach [1] 1

The chief defect of all previous materialism (that of Feuerbach included) is that things [ Gegenstand ], reality, sensuousness are conceived only in the form of the object, or of contemplation , but not as sensuous human activity, practice , not subjectively. Hence, in contradistinction to materialism, the active side was set forth abstractly by idealism — which, of course, does not know real, sensuous activity as such. Feuerbach wants sensuous objects, really distinct from conceptual objects, but he does not conceive human activity itself as objective activity. In Das Wesen des Christenthums , he therefore regards the theoretical attitude as the only genuinely human attitude, while practice is conceived and defined only in its dirty-Jewish form of appearance [2] . Hence he does not grasp the significance of “revolutionary”, of “practical-critical”, activity.

The question whether objective truth can be attributed to human thinking is not a question of theory but is a practical question. Man must prove the truth, i.e., the reality and power, the this-worldliness of his thinking in practice. The dispute over the reality or non-reality of thinking which is isolated from practice is a purely scholastic question.

The materialist doctrine concerning the changing of circumstances and upbringing forgets that circumstances are changed by men and that the educator must himself be educated. This doctrine must, therefore, divide society into two parts, one of which is superior to society.

The coincidence of the changing of circumstances and of human activity or self-change can be conceived and rationally understood only as revolutionary practice.

Feuerbach starts out from the fact of religious self-estrangement, of the duplication of the world into a religious world and a secular one. His work consists in resolving the religious world into its secular basis. But that the secular basis lifts off from itself and establishes itself as an independent realm in the clouds can only be explained by the inner strife and intrinsic contradictoriness of this secular basis. The latter must, therefore, itself be both understood in its contradiction and revolutionised in practice. Thus, for instance, once the earthly family is discovered to be the secret of the holy family, the former must then itself be destroyed in theory and in practice.

Feuerbach, not satisfied with abstract thinking , wants [ sensuous ] contemplation ; but he does not conceive sensuousness as practical , human-sensuous activity.

Feuerbach resolves the essence of religion into the essence of man . But the essence of man is no abstraction inherent in each single individual. In its reality it is the ensemble of the social relations.

Feuerbach, who does not enter upon a criticism of this real essence, is hence obliged:

1. To abstract from the historical process and to define the religious sentiment [ Gem�t ] by itself, and to presuppose an abstract — isolated — human individual.

2. Essence, therefore, can be regarded only as “species”, as an inner, mute, general character which unites the many individuals in a natural way .

Feuerbach, consequently, does not see that the “religious sentiment” is itself a social product, and that the abstract individual which he analyses belongs to a particular form of society.

All social life is essentially practical . All mysteries which lead theory to mysticism find their rational solution in human practice and in the comprehension of this practice.

The highest point reached by contemplative materialism, that is, materialism which does not comprehend sensuousness as practical activity, is the contemplation of single individuals and of civil society.

The standpoint of the old materialism is “civil” society; the standpoint of the new is human society, or social humanity.

The philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.

Deutsch | 1969 Selected Works translation | 2002 translation of Marx’s original | MECW translation of Engels’ 1888 version

Marx/Engels Works Archive | Study Guide | Engels on Feuerbach | Image of Thesis 11 | Works Index

Theses on Feuerbach

Originally written in 1845, these notes were not published until after Marx's death in 1888 by Engels.

The main deficiency, up to now, in all materialism – including that of Feuerbach – is that the external object, reality and sensibility are conceived only in the form of the object and of our contemplation of it, rather than as sensuous human activity and as practice – as something non-subjective. For this reason, the active aspect has been developed by idealism, in opposition to materialism, though only abstractly, since idealism naturally does not know real, sensuous activity as such. Feuerbach wants sensuous objects, clearly distinguished from mental objects, but he does not conceive human activity in terms of subject and object. That is why, in The Essence of Christianity , he regards only theoretical activity as authentically human, whilst practice is conceived and defined only in its dirty Jewish manifestation. He therefore does not understand the meaning of “revolutionary”, of practical-critical activity.

The question whether objective truth can be attributed to human thinking is not a question of theory but a practical question. Man must prove in practice the truth - i.e. the reality and power, the worldliness - of his thinking. Isolated from practice, the controversy over the reality or unreality of thinking is a purely scholastic question.

The materialist doctrine that humans are products of circumstances and upbringing and that, therefore, men who change are products of new circumstances and a different upbringing, forgets that circumstances are changed by men themselves, and that it is essential to educate the educator. Necessarily, then, this doctrine divides society into two parts, one of which is placed above society (for example, in the work of Robert Owen).

The coincidence of changing circumstance on the one hand, and of human activity or self-changing on the other, can be conceived only as revolutionary practice, and rationally understood.

Feuerbach starts out from the fact of religious self-alienation and the duplication of the world into an imagined religious world and a real world. His work consists in resolving the religious world into its secular basis. He overlooks that, once this work is completed, the central task remains to be done. But the fact that the secular basis detaches from itself and fixes in the clouds as an independent realm can be explained only by the self-negation and self-contradiction within it. This must be first of all understood in the context of its contradictions, and then be revolutionised by the removal of those contradictions. Thus, for instance, once the earthly family is discovered to be the secret of the holy family, the former must then be theoretically critiqued and practically overthrown.

Feuerbach, not satisfied with abstract thinking, appeals to sensory intuition; but he does not conceive the realm of the senses in terms of practical, human sensuous activity.

Feuerbach resolves the religious essence into the human essence. But the human essence is not an abstraction inherent in each single individual. In its reality, it is the ensemble of social conditions.

Feuerbach, who does not undertake a criticism of this real essence, is therefore compelled:

1. To abstract from the historical process and to fix the religious sentiment as something by itself and to presuppose an abstract – isolated – human individual;

2. For this reason, he can consider the human essence only as a “genus”, as an internal, mute generality which naturally unites the multiplicity of individuals.

Feuerbach therefore does not see that “religious sentiment” is itself a social product, and that the abstract individual that he analyses belongs in reality to a particular social form.

Social life is essentially practical. All the mysteries which turn theory towards mysticism find their rational solution in human practice and in the understanding of this practice.

The highest point reached by intuitive materialism - that is, materialism which does not comprehend the activity of the senses as practical activity - is the point-of-view of single individuals in “bourgeois society”.

The standpoint of the old materialism is “bourgeois” society; the standpoint of the new is human society, or socialised mankind.

Philosophers have only interpreted the world in different ways. What is crucial, however, is to change it.

This work is in the public domain worldwide because it has been so released by the copyright holder.

Public domain Public domain false false

- Works with non-existent author pages

Navigation menu

- Knowledge and Education

- Social Sciences and Humanities

- Source (9/16)

Karl Marx, “Theses on Feuerbach” (1845)

Karl Marx is known as the father of communism. Written in 1845, his “Theses on Feuerbach” outlined the basic tendencies of his thought. A radical materialist, Marx wanted nothing to do with religious or philosophical forms of speculation. Both of these forms, he argued, were themselves determined by the material facts of social life. The essence of the human person as a thinking self, in fact, could only be understood in terms of one’s own social location and the economic relationships by which one was utterly dominated. Marx grounded his philosophy of historical change upon these ideas. Alterations in political history were due not to ideas, however derived, but to underlying forces at the base of society. He concluded these theses with his famous appeal for a new kind of philosophy, one that would not interpret human reality, but rather change it. Marx’s ideas influenced every area of modern German knowledge, from political and social thought to ethical reflection, cultural analysis, and university scholarship.

I The chief defect of all hitherto existing materialism—that of Feuerbach included—is that the thing, reality, sensuousness, is conceived only in the form of the object or of contemplation , but not as sensuous human activity, practice , not subjectively. Hence, in contradistinction to materialism, the active side was developed abstractly by idealism—which, of course, does not know real, sensuous activity as such. Feuerbach wants sensuous objects, really distinct from the thought objects, but he does not conceive human activity itself as objective activity. Hence, in The Essence of Christianity , he regards the theoretical attitude as the only genuinely human attitude, while practice is conceived and fixed only in its dirty-judaical manifestation. Hence, he does not grasp the significance of “revolutionary,” of “practical-critical,” activity.

II The question whether objective truth can be attributed to human thinking is not a question of theory but is a practical question. Man must prove the truth—i.e. the reality and power, the this-sidedness of his thinking in practice. The dispute over the reality or non-reality of thinking that is isolated from practice is a purely scholastic question.

III The materialist doctrine concerning the changing of circumstances and upbringing forgets that circumstances are changed by men and that it is essential to educate the educator himself. This doctrine must, therefore, divide society into two parts, one of which is superior to society. The coincidence of the changing of circumstances and of human activity or self-changing can be conceived and rationally understood only as revolutionary practice .

IV Feuerbach starts out from the fact of religious self-alienation, of the duplication of the world into a religious world and a secular one. His work consists in resolving the religious world into its secular basis. But that the secular basis detaches itself from itself and establishes itself as an independent realm in the clouds can only be explained by the cleavages and self-contradictions within this secular basis. The latter must, therefore, in itself be both understood in its contradiction and revolutionized in practice. Thus, for instance, after the earthly family is discovered to be the secret of the holy family, the former must then itself be destroyed in theory and in practice.

V Feuerbach, not satisfied with abstract thinking, wants contemplation; but he does not conceive sensuousness as practical, human-sensuous activity.

VI Feuerbach resolves the religious essence into the human essence. But the human essence is no abstraction inherent in each single individual. In its reality it is the ensemble of the social relations. Feuerbach, who does not enter upon a criticism of this real essence, is consequently compelled: 1. To abstract from the historical process and to fix the religious sentiment as something by itself and to presuppose an abstract—isolated—human individual. 2. Essence, therefore, can be comprehended only as “genus”, as an internal, dumb generality which naturally unites the many individuals.

VII Feuerbach, consequently, does not see that the “religious sentiment” is itself a social product, and that the abstract individual whom he analyses belongs to a particular form of society.

VIII All social life is essentially practical. All mysteries which lead theory to mysticism find their rational solution in human practice and in the comprehension of this practice.

IX The highest point reached by contemplative materialism, that is, materialism which does not comprehend sensuousness as practical activity, is contemplation of single individuals and of civil society.

X The standpoint of the old materialism is civil society; the standpoint of the new is human society, or social humanity.

XI The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point is to change it.

Source of English translation: Marx/Engels Internet Archive (marxists.org) 1995, 1999, 2002. Permission is granted to copy and/or distribute this document under the terms of CC BY-SA 2.0. Available online at: https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/theses/theses.htm

Source of original German text: Karl Marx, “Thesen über Feuerbach,” in Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, Werke , vol. 3. Berlin: Dietz, 1962, pp. 5–7.

Recommended Citation

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Karl Marx. Thesen über Feuerbach. Theses on Feuerbach. German Text with a Facing Page English Translation. By Carlos Bendaña-Pedroza

2022, Karl_Marx_Thesen_über_Feuerbach_Theses_on_Feuerbach_German_Text_English_Translation_Carlos_Bendaña-Pedroza_Bonn_2019

German Text of the Marx-Engels Gesamtausgabe (MEGA,1932) and the Marx-Engels Werke (MEW, 1958). English translation based on the textual and contextual analysis, which the translator has outlined in El manifiesto del método (Manifesto of Method, 2015 [1981])

Related Papers

Karl_Marx_Theses_on_Feuerbach_1)_ad_Feuerbach_Trans_Carlos_Bendaña-Pedroza_Bonn_2019

Carlos Bendana-Pedroza

English translation based on a systematic textual and contextual analysis. The „Theses on Feuerbach“ are the fundamental text of marxism and a key text of the history of philosophy. Hence the importance of the accurate translation of this document.

Texto alemán y traducción al castellano basada en el análisis textual y contextual sistemático. Las "Tesis sobre Feuebach" son el documento fundamental del marxismo y uno de los textos claves de la historia de la filosofía. De ahí la importancia de su traducción rigurosa.

KARL_MARX_THESES_ON_FEUERBACH_NEW_ENGLISH_TRANSLATION_ BASED_ON_THE_NEW_MEGA_CARLOS_BENDAÑA-PEDROZA_BONN_2022

A new English translation of Karl Marx’s “Theses on Feuerbach” based on the text of the new Marx-Engels Gesamtausgabe (MEGA), sec. IV, vol. 3, Berlin, 1998; and on the reading outlined by the translator in his essay: El manifiesto del método (Manifesto of Method), Bonn, 2015 (1981).

KARL_MARX_THESEN_ÜBER_FEUERBACH_NEUE_SPANISCHE_ÜBERSETZUNG_NACH_DER_NEUEN_MEGA_CARLOS_BENDAÑA-PEDROZA_BONN_2020

Neue spanische Übersetzung der “Thesen über Feuerbach“ von Karl Marx, nach dem Text der neuen Marx-Engels Gesamtausgabe (MEGA), Abt. IV, Bd. 3, Berlin, 1998; und nach der Lektüre, die der Übersetzer in seinem Versuch: El manifiesto del método (Das Manifest der Methode), Bonn, 2015 (1981) skizziert hat.

KARL_MARX_THESEN_ÜBER_FEUERBACH_NEUE_ENGLISCHE_ÜBERSETZUNG_NACH_DER_NEUEN_MEGA_CARLOS_BENDAÑA-PEDROZA_BONN_2020

Neue englische Übersetzung der “Thesen über Feuerbach“ von Karl Marx, nach dem Text der neuen Marx-Engels Gesamtausgabe (MEGA), Abt. IV, Bd. 3, Berlin, 1998; und nach der Lektüre, die der Übersetzer in seinem Versuch: El manifiesto del método (Das Manifest der Methode), Bonn, 2015 (1981) skizziert hat.

Pradip Baksi

A journey through the legacy of Karl Marx, time use studies and, the goal of universal literacy. Karl Marx's critique of political economy is a sublation or Aufhebung of classical political economy, for opening up the frontiers of its future as a science, aimed at self-emancipation of the wage-labourer. He divided his corresponding task into 6 topics: capital, landed property, wage-labour; the state, foreign trade and, world market. His output in this and in the other areas are being published within the Marx-Engels-Gesamtausgabe (MEGA) I-IV: http://mega.bbaw.de/struktur

Nicolás González Varela

Socialist Register

Rob Beamish

Historical Materialism

Kaan Kangal

The following is a critical reconstruction of the collaboration between Bauer and Marx between 1839 and 1842. The turbulences in the period in question reveal themselves in Marx’s thought as well as in his relationship with Bruno Bauer. Correspondingly, Marx’s detours, false paths, dead ends and abandoned work are therefore made the focus of this study. The ambivalent initial relations between the two of them, which both made their collaboration possible and hindered it, clearly go back further than 1841, when Bauer was not yet an atheist and was still a proponent of church doctrine. This was the Bruno Bauer that Marx had come to know in the Doctor’s Club. We then meet Bauer the atheist at the end of 1839 or perhaps the beginning of 1840, as he was planning a comprehensive attack on orthodox theology and wanted Marx to fight on his side. This attack continued in Bauer’s Trumpet and in Hegel’s Doctrine. https://brill.com/view/journals/hima/aop/article-10.1163-1569206X-12341901/article-10.1163-1569206X-12341901.xml

Marcello Musto

the project of a ‘second’ MEGA , designed to reproduce all the writings of the two thinkers together with an extensive critical apparatus, got under way in 1975 in East Germany. Following the fall of the Berlin wall, however, this too was interrupted. A diffi cult period of reorganization ensued, in which new editorial principles were developed and approved, and the publication of MEGA2 recommenced only in 1998. Since then twenty- six volumes have appeared in print – others are in the course of preparation – containing new versions of certain of Marx’s works; all the preparatory manuscripts of Capital; correspondence from important periods of his life including a number of letters received; and approximately two hundred notebooks. ! e latter contain excerpts from books that Marx read over the years and the refl ections to which they gave rise. ! ey constitute his critical theoretical workshop, indicating the complex itinerary he followed in the development of his thought and the sources on which he drew in working out his own ideas. these priceless materials – many of which are available only in German and therefore intended for small circles of researchers – show us an author very different from the one that numerous critics or self- styled followers presented for such a long time. Indeed, the new textual acquisitions in MEGA 2 make it possible to say that, of the classics of political and philosophical thought, Marx is the author whose profi le has changed the most in recent years. The political landscape following the implosion of the Soviet Union has helped to free Marx from the role of fi gurehead of the state apparatus that was accorded to him there. Research advances, together with the changed political conditions, therefore suggest that the renewal in the interpretation of Marx’s thought is a phenomenon destined to continue.

RELATED PAPERS

KARL_MARX_TESIS_SOBRE_FEUERBACH_NUEVA_TRADUCCION_CASTELLANA_BASADA_EN_LA_NUEVA_MEGA_CARLOS_BENDANA-PEDROZA_BONN_2020

Felipe Cotrim

A Bibliography Reflecting Karl Marx's Study of History

Peter C. Caldwell

Marco Solinas

Wulf D. Hund

International Review of Social History

Jack Marler

Alexandre Cunha

History of Political Thought

Esther Oluffa Pedersen

Materialism and Politics

Bernardo Bianchi

Peter Petkov

A proposal for further extending Karl Marx's critique of political economy

historia magistra

Roberto Fineschi

Frank Biewer

Ricardo F . Castro

The SAGE Handbook of Marxism

Miguel Candioti

Science & Society

Journal of Classical Sociology

Terrell Carver

Luis Cruz Olivera

Wolfgang Fritz Haug

A bibliography for New Silk Road Studies after Marx@200

Bielefeld: Transcript

Anna-Sophie Schönfelder

Christoph Henning

Socialism and Democracy

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Marx’s Theses on Feuerbach

The theses on feuerbach and modern leftism..

Marx’s Theses on Feuerbach are one of the most useful texts for understanding his philosophical and revolutionary methodology. This is due to its being concise whilst also demonstrating the methodological approach in action. The theses are a collection of eleven criticisms of prior philosophy up to Feuerbach, with Marx clearly positioning himself as being the herald of a new dawn in human development. He clearly wrote this at a key point in his intellectual development with it demonstrating the importance of his practical materialist focus. The world is not to be changed through philosophy, but through revolutionary action.

Ludwig A. Feuerbach (1804-1872)

Marx’s eleven Theses on Feuerbach:

First thesis:.

An intrinsic flaw in prior philosophic works is asserted, typically this follows the form of an inversion (we believe we are progressing but are in fact regressing, we thought that the answer was in developing more comprehensive ideas but these have led us further from the truth).

In the Hegelian tradition, particularly after its Marxist offshoot, this frequently appears as a criticism of objectivity. In other words, an object of knowledge such as an idea, is critiqued on the grounds of its lack of subjectivity. The aim being to overcome the objective by a rigorous development of the subjective.

Buried in here is an issue over the goal, the telos of thought and action. Where we are oriented toward ‘the wrong goal’ we work against ourselves and must adapt.

Since Marx’s materialism is initially directed against philosophy and religion it is easier to use them as examples. In the former, philosophers have sought to understand the world by creating objects of knowledge and abstractly manipulating them; in the latter, Christian theologians argue that God creates the world.

To Marx these are not only inadequate, they are false and inherently harmful. Philosophy and theology are both set as placing an erroneous value on abstraction to the poverty of the physical, they reject “revolutionary … practical-critical activity.” [1]

Part of Marx’s correction is to ensure that people alter their perception to see the world “as practice”. The person taking part in simple “human activity … objective activity” must make a qualitative transformation and instead perform “ sensuous human activity ”.

Second thesis:

Truth is then detached from those prior systems. For example, truth cannot be apprehended through philosophy or theology, instead truth must be apprehended through the practical. It is down to those holding the ideas to demonstrate their “truth”. It is quite clear that “power” is a core principle. Whether the ideas manifested into action are a success or not are the gauge of their power, their truth. It is only through the vehicle of physical practice that whether something is “real” or not can be demonstrated.

Third thesis:

The progression requires that people themselves are changed. The need is for academics to be instructed, who then teach progressively more students and yet-to-be teachers. It is through academia that revolutionary praxis (theory into action, which generates new theory and is converted into new action, ad nauseum) is established.

Earlier in the Theses on Feuerbach the criticism is levelled against a certain discipline and the knowledge being abstract, whereas here, Marx critiques society itself. Much like how he accuses established knowledge of being oriented towards false truths, society can also be false. The task is to break apart the processes which sustain the existing society and a key part of this is to establish at first in theory, a more ideal form of society. Revolutionary action is putting into effect this theory, it is the action and implementing it which demonstrates its truth. However, this change can only occur through revolutionary action, incidentally, sensuous human activity .

Note: a number of years prior to the Theses on Feuerbach Marx had made clear that this division of society into present and desired, was likewise bifurcated with emotion. He is quite clear that all evil must be concentrated onto existing society whilst at the same time all good is instrumentally located with the Revolutionary Society [2, pp. 137-142] . Revolutionaries need not feel guilt or have any qualms about overthrowing the old society, whilst at the same time they possess certainty of their own moral status.

Fourth thesis:

In this thesis Marx critiques Feuerbach, who had argued that God is a psychological projection out of our consciousness. Feuerbach after his negative critique had then sought a positive one in which divinity became relocated in the collective: “ man with man … that is God” [3, p. §60] and that discovery “takes the place of religion” [3, p. §64] . Marx having a strict materialist position rejects Feuerbach’s philosophy becoming the basis of a new religion, since he sees it as maintaining the old issue by an alternative means. So, Marx set the two as being mutually exclusive, the theoretical destroys the materialistic and so the higher-society cannot be brought into existence. Instead, the future ought to be practical.

Fifth thesis:

Marx accuses Feuerbach of failing to grasp the importance of revolutionary action and that he commits a fundamental error. Note: how V parallels I.

Sixth thesis:

The critique now shifts to reform Feuerbach’s ideas. Marx argues that Feuerbach succeeds in realising that the true essence of religion is not God but is in humanity . However, this cannot merely be left as an abstraction, it must of course be made into practical reality by revolutionary practice which establishes the idea in existence and reveals the power of the idea and action, hence the truth of the matter. In order to make Feuerbach’s collective-human god more than an idea, Marx invests the system of social relations with this divinity. This is summarised as:

- A) Feuerbach re-establishes a contradiction between abstract idea of human divinity and the practical manifestation of human divinity.

- B) This reduces human divinity to the province of being a simple analytical category.

Seventh thesis:

The accusation is that Feuerbach failed to follow the line of reasoning to completion and so, Feuerbach misses Marx’s addition which is that: depending on the type of people you have you get different manifestations of religion. Different societies have different religions and to tie this in with the 3 rd thesis, a higher society will have a higher religious manifestation which can be taught through academia.

Eighth thesis:

It is the physical world which is the essence of social existence and the relations therein. The means of resolving the problem of re-occurring abstraction is to implement revolutionary practice and to establish new theories based on this practice.

Ninth thesis:

Prior philosophic materialism, such as that of Feuerbach, does not yet move the world into a place of non-contradiction between people and the ideas that they hold. Nor does it then overcome civil society with a human society at the level of the species.

Tenth thesis:

The purpose of prior materialism is the erroneous goal of “civil society”, whereas Marx’s materialism is a qualitative change into a new form of society, viz-á-viz I-III, and which realises VI-VIII.

Eleventh thesis:

Philosophers once “interpreted” the world, now their duty is to reform it.

Theses on Feuerbach: Discussion

The Theses on Feuerbach clearly have a number of significant implications.

Marx sets out to establish an entirely new conception of reality and whilst in his view philosophy had utility in the past, it is to be replaced by revolutionary action. Other conceptions of existence, knowledge and ethics are treated as simplistic whereas his materialist conception is positioned as the highest. Truth is dependent on action, not on philosophy, so that ‘truth’ is only what occurs through the materialist worldview. This form of truth is recognised to be subjective, but it is taken as proven when the materialist worldview comes to exert power over existence.

The aim is to undo the distinction between abstract and materialist through revolutionary action.

The above are inculcated through education, be it academic or journalistic. People are taught that on the one hand there are simplistic abstract conceptions of existence, secondly, that there is a higher alternative. This higher alternative is realised (made into a physical reality) through revolutionary action.

Readers might note in the above the mechanistic model of historicism , that history has a purpose and is marching towards it. In Marx’s system he, like Hegel before him, subjectively decides on what that future state of existence ought to look like.

This is important because it establishes an academic monopoly over the ability to determine the pathway of human development. Hegelian academia is inquisitive insofar as they can take their ideas and turn them into directives which others must deliver. In other words, academicians develop complex theories which restrict people into being extensions of the Hegelian academic. The natural consequence of this is that there is a bifurcation in academia, society, culture which is aiming to reform reality. Under Marxian education this means that only certain educators and certain disciplines are considered to have legitimate knowledge or some semblance of the truth. The truth/legitimacy of the discipline or its teaching, stems from the materialist conception of existence and revolutionary action oriented to the subjectively selected historicist goal. The methodology by which knowledge is developed and what is considered to be knowledge, are made the sole province of Hegelian academics (naturally different offshoots will disagree on their version of the truth).

Pre-figured into this is the fact that you as an individual exist for a purpose, and that purpose is to establish this academically hypothesised reformation of existence and the superordinate society that needs to be brought into being.

This new academic process is also religious. Feuerbach argues that God was an idea, a psychological projection which we create, for him this means that God originates in the human. Marx describes how he lost belief in God and decided that “new gods had to be installed” [4, p. 18] . He states that he he arrived at Hegel’s process but with one additional step, which is that it had to be materialised through revolutionary action. In other words, like in Hegel’s philosophy god is constituted by humanity, but like Feuerbach god is in the collective; Marx materialises these two conceptions so that the Marxist collective embody divinity in their union with the material world, in the union of humanity with nature .

The Marxian form of academia indoctrinates students with the idea that history marches toward a known-end. It is the duty of all who receive the Promethean light of the revolutionary methodology from the Marxian academics, to herald and then usher in this future in which the revolutionary collective undergoes a collective apotheosis and becomes divine (“man is the supreme being for man” [2, pp. 137, 142 see also 131] ). Under Marx’s materialist reformation of reality, theology is replaced by social science and the academy becomes a neo-seminary. It is in the neo-seminary that the correct action, knowledge and truths are conveyed to adepts.

Science is here a method for developing peoples’ consciousness toward the end-goal of Marx’s system; the person who undergoes the scientific process is moved from being crude and simple, to being superior. Their duty then becomes the manifestation of the higher reality and its corresponding ‘ human society’. With Hegelian science , the form of religious consciousness and all reality is likewise transformed.

Marx’s Theses on Feuerbach are incredibly useful for understanding the thought which governs Marxist philosophy, revolutionary practice and the later philosophical modifications of Marx’s philosophy and praxis . Within the theses we can see the very movement of the dialectic in action through the critique of Feuerbach. The critique reveals contradictions which must be dialectically brought into harmony and thus create a synthesis. Whilst past syntheses have taken place through abstraction in philosophy, the primary synthesis established by Marx is through materialism. This requires the negation of past abstractions and to then replace philosophical labour with practical labour, that practical labour being the positive movement of ideas which are based on material reality. The task of the materialist collective being to take the abstract Hegelian form of divinity (the philsophic-god of the Absolute Idea) and materialise it, manifesting the divine dialectical collective which restlessly self-creates and reforms its consciousness.

The requirement for revolutionary action does not simply upend society and the political landscape, but reforms existence in its entirety. Through a sequence of historicist steps, the person is dialectically led to a reformed conceptualisation of existence, a new means of developing knowledge and socially constructing ‘truth’, with a corresponding system of ethics and sense of beauty, complete with a new subject-object to worship: humanity-nature . It demands nothing less than a revolution from reality itself.

A number of quotes by Marxian intellectuals on the religious aspects of Marxist socialis are available in my book The Revolutionary Renaissance , some of which can be seen here .

Works Cited

@DialecticWizard

TheHoneybarrel

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Eleven Theses on Feuerbach

Audio with external links item preview.

Share or Embed This Item

Flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[Storj] [Storj]](https://archive.org/images/storj-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

42,821 Views

7 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

In collections.

Uploaded by librivoxbooks on October 15, 2007

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- Monthly Review Essays

- Climate & Capitalism

- Money on the Left

Living the Eleventh Thesis

—Karl Marx, Theses on Feuerbach , No. 11

When I was a boy I always assumed that I would grow up to be both a scientist and a Red. Rather than face a problem of combining activism and scholarship, I would have had a very difficult time trying to separate them.

Before I could read, my grandfather read to me from Bad Bishop Brown’s Science and History for Girls and Boys . 1 My grandfather believed that at a minimum every socialist worker should be familiar with cosmology, evolution, and history. I never separated history, in which we are active participants, from science, the finding out how things are. My family had broken with organized religion five generations back, but my father sat me down for Bible study every Friday evening because it was an important part of the surrounding culture and important to many people, a fascinating account of how ideas develop in changing conditions, and because every atheist should know it as well as believers do.

On my first day of primary school, my grandmother urged me to learn everything they could teach me—but not to believe it all. She was all too aware of the “racial science” of 1930s Germany and the justifications for eugenics and male supremacy that were popular in our own country. Her attitude came from her knowledge of the uses of science for power and profit and from a worker’s generic distrust of the rulers. Her advice formed my stance in academic life: consciously in, but not of, the university. I grew up in a left-wing neighborhood of Brooklyn where the schools were empty on May Day and where I met my first Republican at age twelve. Issues of science, politics, and culture were debated in permanent clusters on the Brighton Beach boardwalk and were the bread and butter of mealtime conversation. Political commitment was assumed, how to act on that commitment was a matter of fierce debate.

As a teenager I became interested in genetics through my fascination with the work of the Soviet scientist Lysenko. He turned out to be dreadfully wrong, especially in trying to reach biological conclusions from philosophical principles. However, his criticism of the genetics of his time turned me toward the work of Waddington and Schmalhausen and others who would not simply dismiss him out of hand in Cold War fashion but had to respond to his challenge by developing a deeper view of the organism–environment interaction.

My wife, Rosario Morales, introduced me to Puerto Rico in 1951, and my eleven years there gave a Latin American perspective to my politics. The various left-wing victories in South America were a source of optimism even in those grim times. FBI surveillance in Puerto Rico blocked me from the jobs I was looking for and I ended up doing vegetable farming for a living on the island’s western mountains.

As an undergraduate at Cornell University’s School of Agriculture, I had been taught that the prime agricultural problem of the United States was the disposal of the farm surplus. But as a farmer in a poor region of Puerto Rico, I saw the significance of agriculture for people’s lives. That experience introduced me to the realities of poverty as it undermines health, shortens lives, closes options, and stultifies personal growth, and to the specific forms that sexism takes among the rural poor. Direct labor organizing on the coffee plantations was combined with study. Rosario and I wrote the agrarian program of the Puerto Rican Communist Party in which we combined rather amateurish economic and social analysis with some firsthand insights into ecological production methods, diversification, conservation, and cooperatives.

I first went to Cuba in 1964 to help develop their population genetics and get a look at the Cuban Revolution. Over the years I became involved in the ongoing Cuban struggle for ecological agriculture and an ecological pathway of economic development that was just, egalitarian, and sustainable. Progressivist thinking, so powerful in the socialist tradition, expected that developing countries had to catch up with advanced countries along the single pathway of modernization. It dismissed critics of the high-tech pathway of industrial agriculture as “idealists,” urban sentimentalists nostalgic for a bucolic rural golden age that never really existed. But there was another view, that each society creates its own ways of relating to the rest of nature, its own pattern of land use, its own appropriate technology, and its own criteria of efficiency. This discussion raged in Cuba in the 1970s and by the 1980s the ecological model had basically won although implementation was still a long process. The Special Period, that time of economic crisis after the collapse of the Soviet Union when the materials for high-tech became unavailable, allowed ecologists by conviction to recruit the ecologists by necessity. This was possible only because the ecologists by conviction had prepared the way.

I first met dialectical materialism in my early teens through the writings of the British Marxist scientists J. B. S. Haldane, J. D. Bernal, Joseph Needham, and others, and then on to Marx and Engels. It immediately grabbed me both intellectually and aesthetically. A dialectical view of nature and society has been a major theme of my research since. I have delighted in the dialectical emphasis on wholeness, connection and context, change, historicity, contradiction, irregularity, asymmetry, and the multiplicity of levels of phenomena, a refreshing counterweight to the prevalent reductionism then and now.

An example: after Rosario suggested I look at Drosophila in nature—not just in bottles in the laboratory—I started to work with the Drosophila in the neighborhood of our home in Puerto Rico. My question was: How do Drosophila species cope with the temporal and spatial gradients of their environments? I began examining the multiple ways that different Drosophila species responded to similar environmental challenges. I could collect Drosophila in a single day in the deserts of Gúanica and in the rain forest around our farm at the crest of the cordillera. It turned out that some species adapt physiologically to high temperature in two to three days, and show relatively little genetic differences in heat tolerance along a 3,000-foot altitude gradient (about twenty miles). Others had distinct genetic sub-populations in the different habitats. Still others adapted to and inhabited only a part of the available environmental range.

One of the desert species was not any better at tolerating heat than some Drosophila from the rain forest, but were much better at finding the cool moist microsites and hiding in them after about 8 a.m. These findings led me to describe the concepts of co-gradient selection, where the direct impact of the environment enhances genetic differences among populations, and counter-gradient selection where genetic differences offset the direct impact of the environment. Since on my transect the high temperature was associated with dry conditions, natural selection acted to increase the size of the flies at Guánica while the effect of temperature on development made them smaller. The outcome turned out to be that the flies from the sea-level desert and the rain forest were of about the same size in their own habitats, but that Guánica flies were bigger when raised at the same temperature as rain forest flies.

In this work I questioned the prevailing reductionist bias in biology by insisting that phenomena take place on different levels, each with their own laws, but also connected. My bias was dialectical: the interaction among adaptations on the physiological, behavioral, and genetic levels. My preference for process, variability, and change set the agenda for my thesis.

The problem was how species can adapt to an environment when the environment was not always the same. When I began thesis work I was puzzled by the facile assumption that, faced with opposing demands, for example when the environment favors small size some of the time and large size the rest of the time, an organism would have to adopt some intermediate state as a compromise. But this is an unthinking application of the liberal bromide that when there are opposing views the truth lies somewhere in the middle. In my dissertation, the study of fitness sets was an attempt to examine when an intermediate position is truly an optimum and when is it the worst possible choice. The short answer turned out to be that when the alternatives are not too different, an intermediate position is indeed optimal, but when they are very different compared to the range of tolerance of the species, then one extreme alone or in some cases a mixture of extremes is preferable.

Work in natural selection within population genetics almost always assumed a constant environment, but I was interested in its inconstancy. I proposed that “environmental variation” must be an answer to many questions of evolutionary ecology and that organisms adapt not only to specific environmental features such as high temperature or alkaline soils but also to the pattern of the environment—its variability, its uncertainty, the grain of its patchiness, the correlations among different aspects of the environment. Moreover, these patterns of environment are not simply given, external to the organism: organisms select, transform, and define their own environments.

Regardless of the particular matter of an investigation (evolutionary ecology, agriculture, or more recently, public health), my core interest has always been the understanding of the dynamics of complex systems. Also, my political commitment requires that I question the relevance of my work. In one of Brecht’s poems he says, “Truly we live in a terrible time…when to talk about trees is almost a crime because it is a kind of silence about injustice.” Brecht was of course wrong about trees: nowadays when we talk of trees we are not ignoring injustice. But he was also right that scholarship that is indifferent to human suffering is immoral.

Poverty and oppression cost years of life and health, shrinks the horizons, and cuts off potential talents before they can flourish. My commitment to support the struggles of the poor and oppressed and my interest in variability combined to focus my attention on the physiological and social vulnerabilities of people.

I have been studying the body’s capacity to restore itself after it is stressed by malnutrition, pollution, insecurity, and inadequate health care. Continual stress undermines the stabilizing mechanisms in the bodies of oppressed populations making them more vulnerable to anything that happens, to small differences in their environments. This shows up in increased variability in measures of blood pressure, body mass index, and life expectancy as compared to more uniform results in comfortable populations. In examining the effects of poverty, it is not enough to examine the prevalence of separate diseases in different populations. Whereas specific pathogens or pollutants may precipitate specific named diseases, social conditions create more diffuse vulnerability that links medically unrelated diseases. For instance, malnutrition, infection, or pollution can breach the protective barriers of the intestine. But once breached for any of these reasons it becomes a locus of invasion by pollutants, microbes, or allergens. Therefore nutritional problems, infectious diseases, stress, and toxicities cause a great variety of seemingly unrelated diseases.

The prevailing notion since the 1960s had been that infectious disease would disappear with economic development. In the 1990s I helped form the Harvard Group on New and Resurgent Disease to reject that idea. Our argument was partly ecological: the rapid adaptation of vectors to changing habitats—to deforestation, irrigation projects, and population displacement by war and famine. We also focused on the equally rapid adaptation of pathogens to pesticides and antibiotics. But we also criticized the physical, institutional, and intellectual isolation of medical research from plant pathology and veterinary studies which could have shown sooner the broad pattern of upsurge of not only malaria, cholera, and AIDS, but also African swine fever, feline leukemia, tristeza disease of citrus, and bean golden mosaic virus. We have to expect epidemiological changes with growing economic disparities and with changes in land use, economic development, human settlement, and demography. The faith in the efficacy of antibiotics, vaccines, and pesticides against plant, animal, and human pathogens is naïve in the light of adaptive evolution. And the developmentalist expectation that economic growth will lead the rest of the world to affluence and to the elimination of infectious disease is being proved wrong.

The resurgence of infectious disease is but one manifestation of a more general crisis: the eco-social distress syndrome—the pervasive multilevel crisis of dysfunctional relations within our species and between it and the rest of nature. It includes in one network of actions and reactions patterns of disease, relations of production and reproduction, demography, our depletion and wanton destruction of natural resources, changing land use and settlement, and planetary climate change. It is more profound than previous crises, reaching higher into the atmosphere, deeper into the earth, more widespread in space, and more long lasting, penetrating more corners of our lives. It is both a generic crisis of the human species and a specific crisis of world capitalism. Therefore it is a primary concern of both my science and my politics.

The complexity of this whole world syndrome can be overwhelming, and yet to evade the complexity by taking the system apart to treat the problems one at a time can produce disasters. The great failings of scientific technology have come from posing problems in too small a way. Agricultural scientists who proposed the Green Revolution without taking pest evolution and insect ecology into account, and therefore expecting pesticides would control pests, have been surprised that pest problems increased with spraying. Similarly, antibiotics create new pathogens, economic development creates hunger, and flood control promotes floods. Problems have to be solved in their rich complexity; the study of complexity itself becomes an urgent practical as well as theoretical problem.

These interests inform my political work: within the left, my task has been to argue that our relations with the rest of nature cannot be separated from a global struggle for human liberation, and within the ecology movement my task has been to challenge the “harmony of nature” idealism of early environmentalism and to insist on identifying the social relations that lead to the present dysfunction. At the same time my politics have determined my scientific ethics. I believe that all theories are wrong that promote, justify, or tolerate injustice.

A leftist critique of the structure of intellectual life is a counterweight to the culture of the universities and foundations. The antiwar movement of the 1960s and 1970s took up the issues of the nature of the university as an organ of class rule and made the intellectual community itself an object of theoretical as well as practical interest. I joined Science for the People, an organization that started with a research strike at MIT in 1967 as a protest against military research on campus. As a member I helped in the challenge to the Green Revolution and genetic determinism. Antiwar activism also took me to Vietnam to investigate war crimes (especially the use of defoliants) and from there to organizing Science for Vietnam. We denounced the use of Agent Orange (used as defoliant in the Vietnamese jungle) that was causing birth defects among Vietnamese peasants. Agent Orange was one of the worst uses of chemical herbicides.

The Puerto Rican independence movement gave me an anti-imperialist consciousness that serves me well in a university that promotes “structural reform” and other euphemisms for empire. My wife’s sharp working-class feminism is a running source of criticism of the pervasive elitism and sexism. Regular work with Cuba shows me vividly that there is an alternative to a competitive, individualistic, exploitative society.

Community organizations, especially in marginalized communities, and the women’s health movement raise issues that academia prefers to ignore: the mothers of Woburn noticing that too many of their children from the same small neighborhood had leukemia, the hundreds of environmental justice groups that noted that toxic waste dumps were concentrated in black and Latino neighborhoods, and the Women’s Community Cancer project and others who insist on the environmental causes of cancer and other diseases while the university laboratories are looking for guilty genes. Their initiatives help me maintain an alternative agenda for both theory and action.

Within the university I have a contradictory relationship with the institution and with colleagues, a combination of cooperation and conflict. We may share a concern about health disparities and persistent poverty, but we are in conflict about corporations funding research for patentable molecules and about government agencies such as USAID (Agency for International Development) promoting the goals of empire. 2

I never aspired to what is conventionally considered a “successful career” in academia. I do not find most of my personal validation through the formal reward and recognition system of the scientific community, and I try not to share the common assumptions of my professional community. This gives me wide freedom of choice. Thus when I declined to join the National Academy of Sciences and received many supportive letters praising my courage or calling it a difficult decision, I could honestly say that it was not a hard decision, merely a political choice taken collectively by the Science for the People group in Chicago. We judged that it was more useful to take a public stand against the Academy’s collaboration with the Vietnam-American War than to join the Academy and attempt to influence its actions from inside. Dick Lewontin had already tried that unsuccessfully and resigned, along with Bruce Wallace.

I have always enjoyed mathematics and see one of its tasks as making the obscure obvious. I regularly employ a sort of mid-level math in unconventional ways to promote understanding more than prediction. Much modeling now aims at precise equations giving precise prediction. This makes sense in engineering. In the field of policy, it makes sense to those who are the advisors to the rulers who imagine they have complete enough control of the world to be able to optimize their efforts and investments of resources. But those of us who are in the opposition have no such illusion. The best we can do is decide where to push the system. For this, a qualitative mathematics is more useful. My work with signed digraphs (loop analysis) is one such approach. Rejecting the opposition between qualitative and quantitative analysis and the notion that quantitative is superior to qualitative, I have mostly worked with those mathematical tools that assist conceptualization of complex phenomena.

Political activism, of course, attracts the attention of the agencies of repression. I have been fortunate in that regard, having experienced only relatively light repression. Others did not fare as well, with lost careers, years of imprisonment, violent attacks, intense harassment even of their families, and deportations. Some, mostly from the Puerto Rican, African-American, and Native American liberation movements, as well as the five Cuban anti-terrorists arrested in Florida, are still political prisoners.

Exploitation kills and hurts people. Racism and sexism destroy health and thwart lives. Studying the greed and brutality and smugness of late capitalism is painful and infuriating. Sometimes I have to recite from Jonathan Swift:

For the most part scholarship and activism have given me an enjoyable and rewarding life, doing work I find intellectually exciting, socially useful, and with people I love.

- ↩ John Montgomery Brown had been a Lutheran Episcopal bishop of the Missouri Synod, excommunicated when he became a Marxist. In the 1930s he published the quarterly journal Heresy .

- ↩ USAID supports health and development in strategically chosen third-world countries. Its separate programs are sometimes helpful and participants are motivated by humanitarian concerns. But the agency is also a terrorist organization, supporting counter-revolutionary groups in Venezuela, Haiti, and Cuba. It once supported LEAP (Law Enforcement Assistance Program) that taught torture to Uruguayan and Brazilian police.

Comments are closed.

Commentary on “Theses on Feuerbach” from “The Principle of Hope,” by Ernst Bloch

Significant brevity is coherent, that is why it is the least quick to put itself into words. Thus the understanding must repeatedly prove itself anew in such propositions. This nowhere more freshly than in the terse collection of the most terse directions which are known as the Eleven Theses on Feuerbach. Marx wrote them down in April 1845 in Brussels, most probably in the burst of preparatory work for ‘The German Ideology’. The theses were not published until 1888 by Engels, as an appendix to his ‘Ludwig Feuerbach and the Outcome of Classical German Philosophy’. Here Engels slightly edited Marx’s occasionally sketchy text for style, naturally without the slightest change of content. Concerning the theses, Engels writes in the foreword to his ‘Ludwig Feuerbach’: ‘They are notes for later elaboration, jotted down quickly, definitely not intended for publication, but invaluable as the first document in which the seed of genius of the new view of the world is set down.’ Feuerbach had recalled us from pure thought to sensory perception, from mind to man, together with nature as his basis. As we know, this both ‘humanistic’ and ‘naturalistic’ rejection of Hegel (with man as the main idea, nature rather than mind as primary) had a strong influence on the young Marx.

Feuerbach’s ‘The Essence of Christianity’, 1841, his ‘Provisional Theses for a Reform of Philosophy’, 1842, and even his ‘Principles of the Philosophy of the Future’, 1843, seemed all the more liberating since even the left-wing school of Hegelians could not detach itself from Hegel, in fact did not go beyond a merely internal Hegelian critique of the master of idealism. ‘The enthusiasm’, says Engels in ‘Ludwig Feuerbach’, looking back at it around fifty years later, ‘was general: we were all momentarily Feuerbachians. How enthusiastically Marx greeted the new interpretation, and how greatly – despite all critical reservations – he was influenced by it, we can read in ‘The Holy Family’ (Ludwig Feuerbach, Dietz, 1946, p. 14). The German youth of that time believed it could at last see land instead of heaven, human, of this world.

Meanwhile Marx very soon detached himself from this all too vague humanness of this world. His activity on the ‘Rheinische Zeitung’ had brought him into far closer contact with political and economic questions than the left-wing Hegelians, or even the Feuerbachians enjoyed. This very contact increasingly led Marx from the critique of religion, to which Feuerbach restricted himself, to the critique of the state, indeed already of the social organization which – as the ‘Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of State’, 1841 – 3, recognizes – determines the form of the state. In Hegel’s distinction between bourgeois society and state, emphasized by Marx, more economic consciousness was in fact already concealed than in his epigones, even in the Feuerbachians. The separation from Feuerbach occurred with respect and in the first place as a correction or even as a mere amendment, but the totally different, social viewpoint is clear from the beginning. On 13th March 1843 Marx thus writes to Ruge:

‘For me Feuerbach’s aphorisms are only incorrect on one point, he refers too much to nature and too little to politics. This is however the only alliance through which current philosophy can become truth’ (MEGA I, 1/2, p. 308). The ‘Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts’, 1844, contain another significant celebration of Feuerbach, admittedly as a contrast to the woolgathering of Bruno Bauer; they praise above all among Feuerbach’s achievements the ‘foundation of true materialism and of real science, in that Feuerbach likewise makes the relationship between ‘'man and man” into the fundamental principle of his theory’ (MEGA I, 3, P. 152). But the ‘Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts’ are already a lot further beyond Feuerbach than they declare. The relationship between ‘man and man’ in them does not remain an abstract anthropological one at all, as it does in Feuerbach, instead the critique of human self-alienation (transferred from religion to the state) already penetrates to the economic heart of the alienation process. This not least in the splendid passages on Hegelian phenomenology, in which the historically formative role of work is identified, and Hegel’s work interpreted in the light of it. At the same time, however, the ‘Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts’ criticize this work because it interprets human work-activity only as mental, not as material. The breakthrough to political economy, i.e. away from Feuerbach’s general idea of man, is accomplished in the first work undertaken in collaboration with Engels, in ‘The Holy Family’, likewise in 1844. The ‘Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts’ already contained the sentence: ‘Workers themselves are capital, a commodity (1.c., p. 103), whereby nothing more of Feuerbachian humanness remains here than its negation in capitalism; ‘The Holy Family’ noted capitalism itself as the source of this strongest and final alienation.

Instead of Feuerbachian generic man, with his abstract naturalness which always remains the same, a historically changing ensemble of social relationships now clearly appeared and above all: one that is antagonistic in class terms. Alienation, of course, embraced both: the exploiting class as well as that of the exploited, above all in capitalism, the strongest form of this relinquishing of self, false objectification of self. ‘But’, states ‘The Holy Family’, ‘the first class feels happy and confirmed in this self-alienation, knows that the alienation is its own power and possesses in it the appearance of a human existence; the second class feels itself destroyed in alienation, perceives in it its own powerlessness and the reality of an inhuman existence’ (MEGA I, 3, P. 206). Which in fact showed the respective class-based methods of production and exchange based on the division of labour, particularly the capitalist ones, to be the finally discovered source of alienation. Marx was a materialist at the latest from 1843 onwards; ‘The Holy Family’ gave birth to the materialist interpretation of history in 1844, and with it scientific socialism. And the ‘Eleven Theses’, produced between ‘The Holy Family’ of 1844/45 and ‘The German Ideology’ of 1845/46 , thus represent the formulated departure from Feuerbach, together with a highly original entry into a new original inheritance. Politically empirical experience from the Rhineland period plus Feuerbach made Marx immune to the ‘mind’ and nothing but ‘mind’ of the left-wing school of Hegelians. The adopted standpoint of the proletariat allowed Marx to become causally and concretely, that is, truly (fundamentally) humanistic.

As is self-evident, the departure here is not a complete break. References to Feuerbach run through large parts of Marx’s work, even after the departure of the ‘Eleven Theses’. Closest to the abandoned land, if only for chronological reasons, stands ‘The German Ideology’ which directly followed the theses. Many critical approaches of the theses return in it, although of course the critique of Feuerbach and the murderous demolition of second-rate Hegelian epigones are vastly different here. Feuerbach still belonged to bourgeois ideology, so the analysis of its pseudo-radical manifestations of decay, such as Bruno Bauer and Stirner [Max Stirner, 1806 – 56, nom de plume of the German individualist philosopher Johann Kaspar], also had to implicate him in ‘The German Ideology’. But in such a way that in places the philosopher himself supplied the handle of the logical weapon with which Marx also intervened against him, but above all against the left-wing Hegelians. Consequently, ‘The German Ideology’ fundamentally begins with the name of Feuerbach and criticizes, starting out from his critique of religion, the simply inner idealistic ‘conquering’ of idealism. ‘It has not occurred to any of these philosophers to inquire about the connections of German philosophy with German reality, about the connections of their critique with their own material surroundings’ (MEGA I, 5, P. 10). However, Marx stresses on the other hand that Feuerbach ‘is to be greatly preferred to the “pure” materialists in that he realizes that man is also a “sensory object"’. In fact, the recognition cited above indicates the importance of Feuerbach for the early development of Marxism just as much as the critique of his abstract, ahistorical notion of the human being indicates the un- and indeed anti-Feuerbachian character of fully developed Marxism itself. The recognition states: without man equally being a ‘sensory object’, it would have been much more difficult to have worked out human activity materialistically as the root of all social things. Feuerbach’s anthropological materialism thus marks the facilitated possible transition from mere mechanical to historical materialism. The critique states: without the concretization of what is human into really existing, and above all socially active men, with real relationships to one another and to nature, materialism and history would have in fact continually fallen apart, despite all ‘anthropology’. In this connection, however, Feuerbach always remains important for Marx, both as a transit point and as the only contemporary philosopher of whom an analysis is at all possible, clarifying and fruitful. The basic thoughts to which Marx critically reacts in this way, and via which he makes productive progress, are essentially contained in Feuerbach’s central work ‘The Essence of Christianity’ of 1841. Feuerbach’s ‘Provisional Theses for a Reform of Philosophy’ of 1842 and the ‘Principles of the Philosophy of the Future’ of 1843 also come into consideration. The earlier writings of the philosopher can hardly have been of any importance for Marx, since Feuerbach, at least until 1839, was too unoriginal, and lay too much under the influence of Hegel. Only from that time on did Feuerbach apply the Hegelian concept of self-alienation to religion. Only from that time on did the earlier Hegelian say his first thought had been God, his second reason, and his third and last was man. This means: just as the Hegelian philosophy of reason had overcome church-belief, so philosophy now put man (with the inclusion of nature as his basis) in place of Hegel. Despite all this, however, Feuerbach could not find the path to reality; precisely the most important aspect of Hegel: the historical-dialectical method, he rejected. It was only the ‘Eleven Theses’ that became signposts out of mere anti-Hegelianism into reality which can be changed, out of the materialism of the base behind the lines into that of the Front.

Question of Grouping