Skip to content

Read the latest news stories about Mailman faculty, research, and events.

Departments

We integrate an innovative skills-based curriculum, research collaborations, and hands-on field experience to prepare students.

Learn more about our research centers, which focus on critical issues in public health.

Our Faculty

Meet the faculty of the Mailman School of Public Health.

Become a Student

Life and community, how to apply.

Learn how to apply to the Mailman School of Public Health.

New Research Highlights Inequities in Diagnosis, Treatment of Postpartum Depressive Symptoms

Pregnancy and childbirth can be significant stressors on mental health. Nearly one in eight people who have given birth develop postpartum depression, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than just the “baby blues,” postpartum depressive symptoms can lead to adverse outcomes for birthing people and families, and treatment requires effective screening, diagnosis and management.

New research from Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health, published online and in the April print issue of Health Affairs , has uncovered significant underdiagnosis and undertreatment of postpartum depressive symptoms as well as stark racial and ethnic inequities in diagnosis and treatment for those with postpartum depressive symptoms. The research was led by senior author Jamie Daw , PhD, assistant professor of Health Policy and Management at Columbia Mailman School in collaboration with Sarah Haight, first author and doctoral candidate in epidemiology at the Gillings School as part of her dissertation.

The research drew on data from a novel survey led by Daw at Columbia that followed up with 4,542 postpartum people who had a live birth in 2020 in seven jurisdictions: Kansas, Michigan, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Utah, Virginia and New York City. The researchers found that 11.8 percent of those sampled reported postpartum depressive symptoms at 2-6 months postpartum. However, only 1 in 4 individuals with depressive symptoms received a perinatal mood and anxiety disorder (PMAD) diagnosis, and one in two reported receiving some form of mental health care in the first year postpartum.

The study found that while there were no statistical differences in PMAD diagnoses based on race or ethnicity, among those with depressive symptoms, 67 percent of white respondents received postpartum mental health treatment compared to only 37 percent of Hispanic and Black respondents and 19.7 percent of respondents who identified as Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, Southwest Asian, Middle Eastern or North African.

“Our study in concert with existing work shows that Asian, Black and Latine birthing people, who may be at the greatest risk of postpartum depression, are the least likely to receive any form of postpartum mental health care—illustrating stark racial inequities in how postpartum depression is identified and managed in the U.S.,” said Haight.

“Previous studies on PMAD symptoms, diagnosis and treatment have typically focused only on the early postpartum period. By following people through the postpartum year, our findings elucidate how many individuals with mental health symptoms fall through the cracks and don’t ever receive the care they need,” said Daw.

The study findings suggest that policies that require and reimburse universal mental health screening at postpartum visits, ensure connections to care, reduce gaps in postpartum insurance coverage, and require clinician training in culturally responsive resources could improve equity of postpartum depression diagnosis and care in the U.S.

Birthing people undergo physical, mental and social upheaval during the perinatal and postpartum periods. Caring for a newborn, managing hormonal changes, and navigating existing social, financial or relational situations—each can place a burden on mental health that PMAD can magnify, according to authors Haight and Daw. PMAD is linked to low social support, less closeness and warmth with partners, stunted infant growth, delayed infant cognitive and language development, poor infant sleep, compromised maternal-infant attachment, and difficulty initiating or maintaining breastfeeding. “Half of pregnancy-related deaths in the U.S. occur in the postpartum year and mental health conditions are the second leading cause of deaths in the late postpartum period. Improving equitable access to PMAD diagnosis and treatment is thus critical to addressing the maternal health crisis in the U.S.,” said Daw.

“Our findings document disparities in care, but future work is needed to investigate how structural and interpersonal racism may explain these observed inequities and what efforts are needed to address these mechanisms and their harmful effects,” said Haight.

The study is part of the Health Affairs April 2024 issue on perinatal mental health and well-being, which explores the impacts of perinatal mental health on parents, infants and children and how policies can intervene to help. Daw and Haight, along with fellow experts and co-authors, will be part of a virtual symposium on Wednesday, April 3 at 1:00 pm, ET.

Co-authors are Chantel Martin, Brian Wells Pence, and Joanna Maselko, Gillings School; Karen Sheffield-Abdullah, UNC School of Nursing; Sarah Verbiest, UNC School of Social Work, School of Medicine and Gillings School.

Media Contact

Stephanie Berger, [email protected]

Related Information

Meet our team, jamie daw, phd.

- Affiliate, Columbia Population Research Center

New research highlights inequities in treatment of postpartum depressive symptoms

April 1, 2024

Pregnancy and childbirth can be significant stressors on mental health. Nearly one in eight people who have given birth develop postpartum depression , according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More than just the “baby blues,” postpartum depressive symptoms can lead to adverse outcomes for birthing people and families, and treatment requires effective screening, diagnosis and management.

New research from the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health and the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health, published today online and in the April print issue of Health Affairs , has uncovered significant underdiagnosis and undertreatment of postpartum depressive symptoms. As part of her dissertation, this study was led by Sarah Haight, MPH, doctoral candidate in epidemiology at the Gillings School in collaboration with Jamie Daw, PhD, assistant professor of health policy and management at the Mailman School. The researchers also found stark racial and ethnic inequities in treatment for those with postpartum depressive symptoms.

The research drew on data from a novel survey led by Daw at Columbia University that followed up with 4,542 postpartum people who had a live birth in 2020 in seven jurisdictions: Kansas, Michigan, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Utah, Virginia and New York City. The researchers found that 11.8% of those sampled reported postpartum depressive symptoms at 2-6 months postpartum. However, only one in four individuals with depressive symptoms received a perinatal mood and anxiety disorder (PMAD) diagnosis, and one in two reported receiving some form of mental health care in the first year postpartum.

The study found that while there were no statistical differences in PMAD diagnoses based on race or ethnicity, among those with depressive symptoms, 67% of white respondents received postpartum mental health treatment compared to only 37% of Hispanic and Black respondents and 19.7% of respondents who identified as Asian, Native Hawaiian, Pacific Islander, Southwest Asian, Middle Eastern or North African.

Sarah Haight

“Our study in concert with existing work shows that Asian, Black and Latine birthing people, who may be at the greatest risk of postpartum depression, are the least likely to receive any form of postpartum mental health care – illustrating stark racial and ethnic inequities in how postpartum depression is identified and managed in the U.S.,” said Haight.

“Previous studies on PMAD symptoms, diagnosis and treatment have typically focused only on the early postpartum period. By following people through the postpartum year, our findings elucidate how many individuals with mental health symptoms fall through the cracks and don’t ever receive the care they need,” said Daw.

The study findings suggest that policies that require and reimburse universal mental health screening at postpartum visits, ensure connections to care, reduce gaps in postpartum insurance coverage, and require clinician training in culturally responsive resources could improve equity of postpartum depression diagnosis and care in the U.S.

Birthing people undergo physical, mental and social upheaval during the perinatal and postpartum periods. Caring for a newborn, managing hormonal changes, and navigating existing social, financial or relational situations – each can place a burden on mental health that PMAD can magnify, according to the researchers. PMAD is linked to low social support, less closeness and warmth with partners, stunted infant growth, delayed infant cognitive and language development, poor infant sleep, compromised maternal-infant attachment, and difficulty initiating or maintaining breastfeeding.

“Half of pregnancy-related deaths in the U.S. occur in the postpartum year and mental health conditions are the second leading cause of deaths in the late postpartum period. Improving equitable access to PMAD diagnosis and treatment is thus critical to addressing the maternal health crisis in the U.S.,” said Daw.

“Our findings document disparities in care, but more work is needed to investigate how structural and interpersonal racism may explain these observed inequities and what efforts are needed to address these mechanisms and their harmful effects,” said Haight.

The study is part of the Health Affairs April 2024 issue on perinatal mental health and well-being, which explores the impacts of perinatal mental health on parents, infants and children and how policies can intervene to help. Haight and Daw, along with fellow experts and co-authors, will be part of a virtual symposium on Wednesday, April 3, at 1:00 p.m. ET

Join the conversation and register for this FREE event: https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/he20240312.862836/full/

Additional co-authors on this study include Chantel Martin, PhD (Gillings School), Karen Sheffield-Abdullah, PhD, RN, CNM (UNC School of Nursing), Sarah Verbiest, DrPH (UNC School of Social Work, School of Medicine and Gillings School), Brian Wells Pence, PhD (Gillings School), and Joanna Maselko, ScD (Gillings School).

Contact the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health communications team at [email protected] .

Use this form to submit news, events and announcements to be shared via our newsletter and digital screens.

View and download the visual elements associated with the Gillings School.

For the use of our faculty, staff and students, the School offers the following PowerPoint template, which can be modified as needed.

This form allows faculty and staff to create a new web profile or update a current one.

This form enables Gillings School representatives to submit requests for website edits.

Garcia wins the 2024 Gertrude M. Cox Award

Information for:.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 12 April 2021

Predicting women with depressive symptoms postpartum with machine learning methods

- Sam Andersson 1 ,

- Deepti R. Bathula 2 ,

- Stavros I. Iliadis 1 ,

- Martin Walter 3 , 4 , 5 &

- Alkistis Skalkidou 1

Scientific Reports volume 11 , Article number: 7877 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

42 Citations

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Machine learning

- Risk factors

Postpartum depression (PPD) is a detrimental health condition that affects 12% of new mothers. Despite negative effects on mothers’ and children’s health, many women do not receive adequate care. Preventive interventions are cost-efficient among high-risk women, but our ability to identify these is poor. We leveraged the power of clinical, demographic, and psychometric data to assess if machine learning methods can make accurate predictions of postpartum depression. Data were obtained from a population-based prospective cohort study in Uppsala, Sweden, collected between 2009 and 2018 (BASIC study, n = 4313). Sub-analyses among women without previous depression were performed. The extremely randomized trees method provided robust performance with highest accuracy and well-balanced sensitivity and specificity (accuracy 73%, sensitivity 72%, specificity 75%, positive predictive value 33%, negative predictive value 94%, area under the curve 81%). Among women without earlier mental health issues, the accuracy was 64%. The variables setting women at most risk for PPD were depression and anxiety during pregnancy, as well as variables related to resilience and personality. Future clinical models that could be implemented directly after delivery might consider including these variables in order to identify women at high risk for postpartum depression to facilitate individualized follow-up and cost-effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Postpartum depression: a developed and validated model predicting individual risk in new mothers

Trine Munk-Olsen, Xiaoqin Liu, … Merete L. Maegbaek

Individualized prediction of psychiatric readmissions for patients with major depressive disorder: a 10-year retrospective cohort study

Ting Zhu, Jingwen Jiang, … Wei Zhang

Predicting change in diagnosis from major depression to bipolar disorder after antidepressant initiation

Melanie F. Pradier, Michael C. Hughes, … Roy H. Perlis

Introduction

Postpartum depression (PPD), defined as having an episode of minor or major depression during pregnancy or up to one year after giving birth, is a relatively common condition that affects 8–15% of new mothers in Sweden every year 1 , 2 . The etiology of PPD is not well understood, but the condition likely arises from a combination of psychological, psychosocial and biological factors 3 , 4 . The most well documented biological risk factors for PPD are hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis dysregulation, inflammatory processes, genetic vulnerability, and allopregnanolone withdrawal 4 . The strongest psychosocial factors are previous depression, severe life events, some forms of chronic stress and relationship struggles 4 , 5 . The role of resilience and personality have been lately also gaining attention 6 , 7 .

PPD is a condition that can have devastating effects on the mothers, as well as their children 8 , 9 . Mothers may experience persistent doubts about their ability to care for the child, have difficulties bonding with their child, and also have thoughts about hurting the child 2 . Moreover, PPD can affect a child’s development by interfering with the mother-infant relationship 10 , 11 . For instance, children of mothers with PPD have greater cognitive, behavioral and interpersonal problems compared to children of mothers without PPD 12 , 13 . Despite PPD being a detrimental health condition for many women, numerous affected women fail to receive adequate care 14 . There exist several effective treatments and interventions for PPD 14 , 15 , 16 , but they are only cost-effective among high-risk women. The idea of prenatal prediction of PPD has existed for several years and early studies using more traditional methods attempted to predict women at risk by prenatal assessment of critical variables 17 . However, to date, there has been no effective way to predict women at risk for the development of depressive symptoms postpartum.

Traditional statistical methods allow researchers to estimate risks by sequentially analysing the associations mainly between two variables, often controlling for the effect of others. Further, machine learning (ML) methods enable researchers to iteratively and simultaneously analyse multiple interacting associations between variables 18 as well as to devise data-driven predictive models that then can be evaluated by quantifying the performance metrics across all models in order to find the best predictive model. The power of ML allows for the analysis of complex non-linear relationships and even the integration and pooling of multiple different data-types from several sources 19 , 20 , 21 . Over the last decade, there has been a steady increase in the use of ML in medicine and its effects can be observed in many fields including oncology 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , cardiology and hematology 26 , 27 , critical care 28 , 29 , and psychiatry 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 . Importantly, PPD represents a unique case in which a moderately high chance to develop a serious psychiatric condition is coupled with a very precise temporal prediction of when such symptoms are to be expected. As such, and considering PPDs substantial societal burden, ML-based risk classification can be applied in an ideal situation with high expected societal benefit. With approximately 120,000 annual births in Sweden and the typical prevalence of PPD at 12% among women who nearly in their entirety present with a multitude of adaptations after childbirth, close monitoring of the whole population for early depressive sentinels after childbirth seems hardly feasible in reality. In contrast, close follow-up among high risk groups during midwife or nurse-led postpartum assessments may strongly contribute to more tailored and cost-efficient maternal perinatal mental care services.

However, despite promising results in other fields, relatively few studies have been performed using ML in the field of perinatal mental health. An early study in the field could predict PPD with an accuracy of 84% by use of multilayer perceptrons and assessment of 16 variables 36 . A recent pilot study used ML algorithms applied to data extracted from electronic health records to show that ML models can be utilized to predict PPD and identify critical variables that conform with known risk variables such as race, demographics, threatened abortion, prenatal mental disorder, anxiety, and an earlier episode of major depression 34 . Another study also developed models to predict PPD, which were then integrated into a mobile application platform to be used by pregnant women 37 , while a recently published study compared four PPD prediction models that comprised demographic, social and mental health data 38 . In the latter study, psychological resilience was pointed out as an important predictive factor. However, these studies have been limited by either sample size or richness of data. Finally, in a recently published study, Zhang et al. proposed a machine learning based framework for PPD risk prediction in pregnancy, using electronic health record data 39 .

To date, our study is the first using a population-based, large and rich dataset, including a wide range of clinical and psychometric self-report and medical journal-derived variables and evaluating a range of different ML algorithms against each other, and also after stratification for earlier or pregnancy depression, to provide a robust screening tool, at discharge from the delivery ward, for predicting women at risk for developing depressive symptoms later in the postpartum period.

Hence, we aim to predict women at risk for depressive symptoms at 6 weeks postpartum, from clinical, demographic, and psychometric questionnaire data available after childbirth, by use of machine learning methods.

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows summary statistics of the study population by depressive symptom status at 6 weeks postpartum. Results are presented as frequencies and relative frequencies within EPDS status [N (%)] or median (interquartile range) for sociodemographic, clinical and questionnaire variables. Of the 4313 participants in the study, 577 had depressive symptoms at 6 weeks postpartum. The mean age for both groups was 31 years. Differences were seen among women with depressive symptoms and women without depressive symptoms across sociodemographic variables like education, employment, and country of origin, as well as many other variables known as risk factors for postpartum depression. A greater proportion of women with depressive symptoms postpartum did not receive adequate support from their partner and were not breastfeeding.

Classification graphs

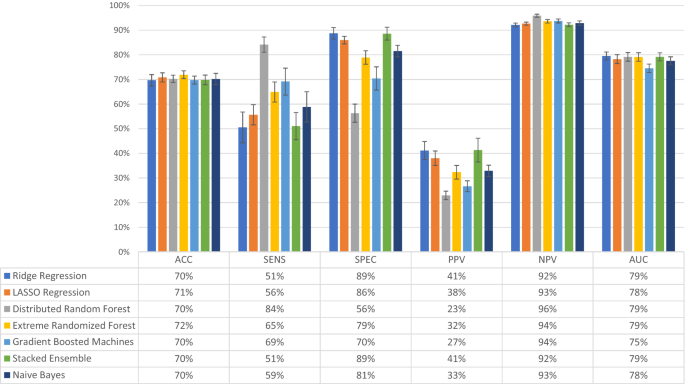

To evaluate whether ML can predict women with depressive symptoms, two datasets were used, namely the BP variables and the combined dataset, that includes the BP variables and three psychometric questionnaires (RS, SOC, and VPSQ). Performance of different ML models was first evaluated for the BP data (Fig. 1 ). The performance metrics for Ridge Regression, LASSO Regression, Gradient Boosting Machines, Distributed Radom Forests (DRF), Extreme Randomized Forests (XRT), Naïve Bayes and Stacked Ensembles models are shown. Balanced accuracy, NPV and AUC were quite similar across the models, with accuracy reaching 72% and AUC 79% for XRT. NPV was over 92% for all models. Sensitivity was quite low and together with specificity and PPV, they varied between the models. Sensitivity was highest for DRF at 84%, while only 65% for XRT; DRF had though the lowest specificity and PPV. The highest PPV was observed for Ridge Regression and Stacked Ensemble, at 41%.

Evaluation of model performance in the dataset containing only background, medical and pregnancy-related variables (n = 4277 women). The models tested were Ridge Regression, LASSO Regression, Distributed Random Forest, Extremely Randomized Trees, Gradient Boosted Machines, Stacked Ensemble, and Naïve Bayes. Models were assessed for accuracy (ACC), sensitivity (SENS), specificity (SPEC), positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and area under the curve (AUC), the outcome being depressive symptoms at 6 weeks postpartum. The bars represent the level of performance measures (in percent) and the table below the bar plot presents the exact numerical values. Error bars represent one standard deviation from the mean.

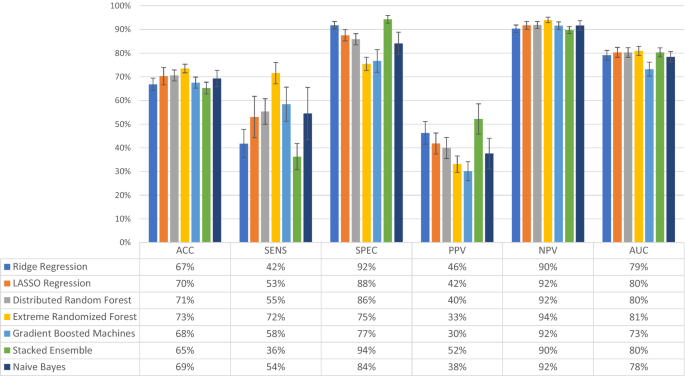

Performance of different ML models was then evaluated for the combined dataset, even including psychometric measures (Fig. 2 ). Performance metrics for the same models showed that NPV was still over 90% for all models, but otherwise, similar levels of accuracy and AUC were observed. More variability among the models was observed for sensitivity, specificity and PPV. XTR had the highest accuracy (at 73%) and AUC (at 81%) among all models, with a balance in sensitivity at 72% and specificity at 75%; PPV was at 33% and NPV at 94%. As this balancing act is an essential attribute of predictive models based on imbalanced datasets the subsequent experimental analysis was provided using only XRT.

Evaluation of model performance in the total combined dataset (n = 2385 women). The combined dataset contained the background, medical and pregnancy-related variables, as well as answers to the questionnaires Resilience-14, Sense of Coherence-29 and Vulnerable Personality Scale Questionnaire. The models tested were Ridge Regression, LASSO Regression, Distributed Random Forest, Extremely Randomized Trees, Gradient Boosted Machines, Stacked Ensemble, and Naïve Bayes. Models were assessed for accuracy (ACC), sensitivity (SENS), specificity (SPEC), positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and area under the curve (AUC), the outcome being depressive symptoms at 6 weeks postpartum. The bars represent the level of performance measures (in percent) and the table below the bar plot presents the exact numerical values. Error bars represent one standard deviation from the mean.

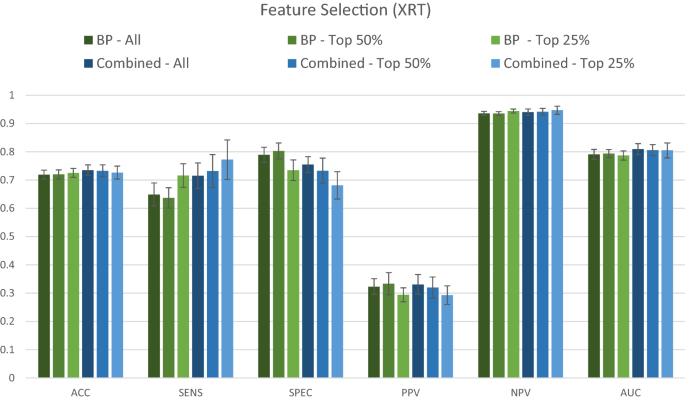

Comparative performance of the XRT model using all variables, the top 50%, and the top 25% variables, for both the BP and the combined dataset is shown in Fig. 3 . There was an apparent trade-off between model sensitivity and specificity, which were both affected by dataset used and percent of variables included (Fig. 3 ). Sensitivity was highest with use of only 25% of the combined dataset, while specificity was highest with the use of the top 50% of the BP dataset. None among the other measures were greatly affected by either dataset used or percent of variables included (a trend to lower PPV when 25% of variables used was noted). The AUC curves corresponding to Figs. 2 and 3 are available in the supplementary material (Supplementary Figure 1 ).

Comparative performance of the dataset containing only background, medical history and pregnancy-related variables (BP) and the combined dataset (BP + RS + SOC + VPSQ). The Extremely Randomized Trees (XRT) algorithm was used to compare the performance of the two datasets for predicting depression at 6 weeks postpartum. Models were assessed for accuracy (ACC), sensitivity (SENS), specificity (SPEC), positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and area under the curve (AUC). The variable selection procedure shows results when All (100%), Top 50%, and Top 25% of variables were retained, ranked according to Mean Decrease in Impurity (MDI) relevance.

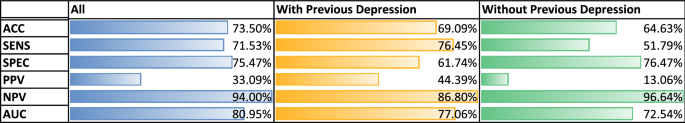

The results for the performance of the XRT models after stratification for previous depression are shown in Fig. 4 . For all women, XRT achieved a balanced accuracy of 73%, a sensitivity of 72%, a specificity of 75%, a positive predictive value of 33%, a negative predictive value of 94% and an AUC of 81%. For women with depression in pregnancy or earlier in life, XRT achieved a balanced accuracy of 69%, a sensitivity of 76%, a specificity of 61%, a positive predictive value of 44%, a negative predictive value of 87% and an AUC of 77%. For women without any previous depressive episode, balanced accuracy was 64%, sensitivity 52%, specificity 76%, positive predictive value of 13%, negative predictive value 97% and AUC of 73% (Fig. 4 ). Among the results from analyses of the individual questionnaires, no single one achieved an accuracy of more than 70% (Supplementary Figure 2 ).

Stratified classification graphs for Extreme Randomized Forest (XRT) model, by pregnancy/previous depression status. Results presented for all women (All, n = 2385, of which 14% had postpartum depression, PPD), women with depression during current pregnancy or earlier in life (With Previous Depression, n = 971, of which 27% had PPD), and women without any previous depression episode (Without Previous Depression, n = 1414, of which 6% had PPD). For each category, models were assessed for accuracy (ACC), sensitivity (SENS), specificity (SPEC), positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and area under the curve (AUC).

Variable importance

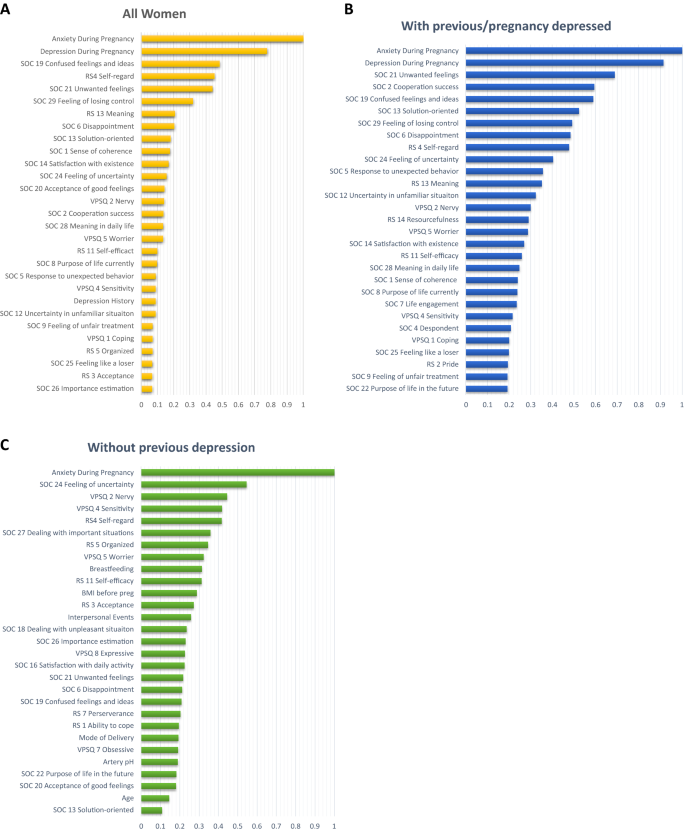

The 25 most important variables by MDI based on Distributed Random Forests (DRF) models, considering the women with different previous depression status are shown in Fig. 5 . For all women, Anxiety During Pregnancy and Depressive During Pregnancy stand out as the two most important variables (importance level above 0.7) (Fig. 5 A). The variables following in importance were questions included in the psychometric instruments, except for history of depression. Similarly, for women with previous depression, Anxiety During Pregnancy and Depressive During Pregnancy stand out as important variables for the presence of depression postpartum (importance level above 0.9) (Fig. 5 B). Finally, for women without depression, Anxiety During Pregnancy was the absolutely most important variable (importance level of 1) (Fig. 5 C). Even here, variables relating to resilience, sense of coherence and personality followed, but interestingly, variables such as breastfeeding, BMI, traumatic events in childhood, mode of delivery, hypoxia in the newborn and age place among the top 25 variables.

Ranked importance of the assessed variables using the Extremely Randomized Trees (XRT) models in the combined dataset, considering the women with different previous depression status. Results presented for all women ( A ), All women (n = 2385), ( B ) women with depression during current pregnancy or earlier in life (Previous/pregnancy depression, n = 971), and ( C ) women without any previous depression episode (No previous depression, n = 1414). The graphs depict the variable importance as a relative measure that is scaled to a maximum of 1.0. The x-axis represents the relative contribution to the classification algorithm of the corresponding feature on the y-axis.

The 25 most important variables based only on BP variables for all women (n = 4313) can be found in Fig. 6 . The two variables that have an importance level above 0.9 are again Depression During Pregnancy and Anxiety During Pregnancy. The next variable with an importance level above 0.3 is Depression History, while the remaining rate below 0.2.

Ranked importance of the assessed background, medical history and pregnancy variables for all women (n = 4277) using Extremely Randomized Trees (XRT) models. The top 25% of the variables are reported . The x-axis represents the relative contribution of the corresponding variable to the classification algorithm.

Including only the top 20 variables, the AUC is only reduced by 1% to 0.79, including just 10 variables reduced the AUC by 2% to ~ 0.78, while after including just 5 variables reduced the AUC by 3% to ~ 0.77. For the previously non-depressed group, including 10 variables gives an AUC of 0.72, and 5 variables an AUC of 0.71.

In this study, we evaluated a range of different machine learning (ML) methods to predict pregnant women at risk for postpartum depressive (PPD) symptoms. The classification performance of the chosen ML algorithms was not significantly different in regard to accuracy, NPV, AUC measures. However, variations were more pronounced in regard to sensitivity, specificity and PPV. In general, as expected, an inverse relationship is observed in performance with respect to sensitivity and specificity. Furthermore, PPV is considerably lower than NPV due to low prevalence of PPD, as expected.

Overall, XRT provides robust performance with highest accuracy and well-balanced sensitivity and specificity. Addition of resilience and personality self-reported variables to the background, medical history and pregnancy-related variables provides marginal improvement in both accuracy and AUC. It is nevertheless of note that these extra variables boost the sensitivity of the XRT model substantially for only a slight drop in specificity. As this does not depend on the lower sample size used for the second step of analyses involving personality and resilience measures, it could be hypothesized that there is either a certain redundancy between variables, e.g. that low resilience is a core feature among depressed patients during pregnancy, or that anxiety and depression measures, available for all patients, have such a strong predictive value that the further addition of variables does not greatly improve accuracy.

These results suggest a possible benefit of using ML to screen new mothers at discharge from the delivery ward in order to identify those at high risk for postpartum depressive symptoms. However, because of the low PPV across all models, due to the relatively low prevalence of PPD at 12%, one would expect that many women identified at high risk would in the end not get depressed. On the other hand, these methods may nevertheless permit the identification of a high-risk group, to which preventive interventions would be offered in a cost-effective way, mainly by avoiding large costs related to full-blown depressive episodes postpartum. These could include the provision of extra support as well as more focused and longitudinal assessments in these mothers. Furthermore, the variables included in the BASIC study refer to easily acquired web-based self-reports, which support their use for screening purposes. Because of the high NPV, we would not expect many women not identified as high risk to develop depression postpartum. As such, the application of our classification algorithms would boost cost-effectiveness, allowing for a tailored resource allocation towards the mothers initially identified at risk versus a more widespread follow up of all mothers; in the low-risk group, assessments could be limited to single timepoints, as is praxis today. As PPD affects more than 16,000 families every year in Sweden alone, with high associated costs, estimated at $30,000 per mother-infant pair for untreated peripartum mood disorders, preventive efforts would have substantial societal benefits 40 .

It is interesting that performance metrics, especially accuracy and AUC, remain stable even when the number of variables used in the models is reduced from 100 to 50% and even to 25% of all variables available, and AUC is relatively stable even at 5–10 variables. As discussed above, this is in line with the thought that there is some redundancy when it comes to the variables included, with depression and anxiety during pregnancy being highly correlated with some background and medical history variables, and possibly mediating their association with PPD. It is thus intriguing to observe that only among non-previously depressed, variables such as breastfeeding, BMI, traumatic interpersonal events in childhood, mode of delivery, infant hypoxia and age are emerging as important for prediction, along with resilience and personality variables, which are otherwise more prominent among those earlier depressed. This is important to have in mind when developing screening strategies; the variables used might need to be adjusted for the group of women with previous depression. Anxiety during pregnancy continues to be very predictive in both groups. The stability of the performance measures however, indicates that an abbreviated survey can be used to screen without significantly affecting predictive power.

Among possible explanations for the somewhat lower accuracy in both the depressed group (earlier or during pregnancy) (n = 971, accuracy = 69%) and never-depressed subgroups (n = 1414, accuracy = 64%) are the lower sample sizes as well as a relatively decreased variability in the data (the algorithms did not have a big number of examples of alternatives to learn from). Sensitivity is the same in the earlier depressed group, but drops to 52% in the never depressed group, underlining the difficulty in identifying women at high risk for having their first ever depressive episode after childbirth. In general, the high NPV figure in the never earlier depressed group means that women with a negative screening in that group do not need tighter follow-up; NPV nonetheless drops to 86% in the earlier depressed group, suggesting that further screening in the postpartum period might still benefit this high-risk group of women.

Our study showed a slightly higher AUC than most earlier studies’ best prediction models (79% by Wang et al. and 78% by Zhang et al.), though our accuracy of 73% is lower than the 84% reported by Tortajada et al. 34 , 36 , 38 . However, in the latter study, the main outcome was depression at 32 weeks and not at 6 weeks postpartum, genetic data was included and the study sample was more homogeneous since it consisted of SSRI-free Caucasian women. Moreover, a lower EPDS cut-off was used followed by clinical interviews, possibly reducing the risk of misclassification of study cases and controls. Nevertheless, in our study, a clinical evaluation was not possible for practical reasons, due to the much larger study population. Finally, in addition to clinical and environmental variables, information on related gene polymorphisms was also utilized in that study.

Furthermore, Wang et al. identified race, obesity, anxiety, depression, different types of pain, and antidepressant and anti-inflammatory drug use during pregnancy as the most important variables for their prediction models 34 . These variables differed somewhat from the ones we identified as being most important with the caveat that our model also indicated that anxiety during pregnancy and depression history or depressive symptoms during pregnancy were overwhelmingly the most significant predictors for PPD. It has to be noted that we included many psychometric measures, which followed in importance, e.g. the question 19 on the SOC scale “Do you have very mixed up feelings and ideas?” and question 4 on RS, which measures self-regard (“I am friends with myself”). The population in the BASIC study is quite homogeneous, most participants having a high education, are quite healthy and born in the Nordic countries. Further, the BASIC dataset has no information on race. BMI was also identified in our study as an important variable, both in the BP dataset analysis and the sub-analysis among women without previous depression. Rates of antidepressant use are low. Differences in the analytical approach might also account for some differences in the results.

These findings further illuminate the difficulties in predicting which women will go on to develop postpartum depressive symptoms after childbirth. From the variable importance plots, the most predictive variables for postpartum depressive symptoms, available at the time of discharge from the delivery ward, is to either have anxiety or depressive symptoms during pregnancy. In fact, these two variables are by far the most predictive, along nevertheless with distinct variables related to resilience, sense of coherence and personality. The predictive algorithms reach an accuracy for the whole group of 73% and AUC of 81%, which is at the limit for possible use in clinical settings. The algorithms might need to be different according to whether women had experience depression before in life. Further studies, possibly using more advanced methods and bigger samples, are warranted.

Very recently, Zhang et al. also proposed a machine learning based framework for PPD risk prediction using electronic health record (EHR) data 39 . While the techniques employed are comparable to our study with similar processing pipeline, they report higher AUC. This increment can be attributed majorly to the substantially larger cohort used in their study. Several ML studies have demonstrated that large datasets lead to lower estimation variance and hence provide better predictive performance. Furthermore, the top predictors also differ between our study due to differences in data sources. Additionally, a PPV higher than that reported in our study would significantly increase the clinical utility of our proposed framework. However, PPV is directly related to the prevalence of PPD in the population studied, which is only about 12%. While the classification threshold of the model can be adjusted to improve PPV, it does not ensure the expected benefit as other evaluation metrics, like sensitivity, specificity and NPV, would be adversely affected. Even Zhang et al. that reported higher AUC values, only report a PPV of ~ 27% for the validation site with prevalence of 6.5%, highlighting the issue 39 .

The lack of effective ways that would allow for early prediction of women at risk for depressive symptoms in the postpartum period has been addressed in the Introduction. In fact, the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale is nowadays used as a screening tool for current depression 41 . National guidelines in several countries recommend screening for PPD at 6 to 8 weeks postpartum; however, the suggested target groups of women to be screened vary between countries 42 , 43 , 44 . Also, the use of the EPDS at this time is used to screen for concurrent depression. In contrast, the role of EPDS in pregnancy, in combination with other variables, for early identification of women at risk for development of depressive symptoms later in the postpartum period has not been studied. In our study we do show that high EPDS scores in pregnancy are highly predictive of postpartum depression.

This study had numerous strengths. First, it addresses a novel field, as there are very few studies in the area, none from the Nordic countries, and none of earlier algorithms is being widely used in clinical practice. The large sample size allowed us to train a robust range of different ML algorithms. The richness of the BASIC dataset provided us with the opportunity to investigate the predictive power of a large number of background, medical history, pregnancy and delivery related variables, as well as psychometric questionnaires; the last ones both as total scores but also at individual item level. A key novelty feature of the study in the inclusion of many resilience and personality-related variables, that have been identified in the literature but not included in previous models. We also explore the importance of variables in terms of their predictive power of PPD, an effort directed towards to designing a compact survey to screen for PPD. Finally, the analysis of clinically relevant sub-groups such as women with previous depression or depression during pregnancy gave clinically useful insights.

Some limitations of the study include the non-representative sample in that women born in Scandinavia, with a high education and cohabitating with the child’s father were over-represented in the cohort, which makes the findings difficult to generalize to the background population. Sources of selection bias are the exclusion of non-Swedish speaking women as the questionnaires were only offered in the Swedish language, and the fact that more healthy women are more prone to participate in studies of this kind. Not all women self-reported on all variables, but we addressed this problem of missing values with exclusions and imputations where appropriate. Class imbalance in the outcome made the training stages of the algorithms challenging but were also addressed appropriately. Lastly, theoretically, some items from the scales on personality (SSP), and attachment (ASQ) might have had a more prominent role in prediction if they would have been available for a larger proportion of the women in this study. The study by Zhang et al., published after our study was conducted, reported higher AUC and included some predictors lacking in our study 39 . Future studies should make sure to include these important predictive variables for further evaluation.

Depressive symptoms and anxiety during pregnancy are highly predictive factors for women who go on and develop postpartum depressive symptoms, while variables relating to resilience, sense of coherence and personality also play a modest role. The predictive algorithms have relatively good accuracy and AUC, with XRT performing best.

Data sources

Data for the development of the prediction models were obtained from the “Biology, Affect, Stress, Imaging and Cognition during Pregnancy and the Puerperium” (BASIC) study. BASIC is a population-based prospective cohort study at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Uppsala University Hospital, Uppsala, Sweden 7 . Between September 2009 and November 2018 all pregnant women who were 18 years of age or older, did not have their identities concealed, had sufficient ability to read and understand Swedish and did not have known bloodborne infections and/or non-viable pregnancy as diagnosed by routine ultrasound were invited to participate in the study 45 . Data acquisition in the BASIC study was mainly based on online surveys and questionnaires that the women were asked to fill out during pregnancy at the 17th and 32nd gestational week and at 6 weeks, 6 months and 12 months postpartum. The surveys included questions about background characteristics, such as sociodemographic variables, psychological measures, medical information, information on reproductive history, lifestyle and sleep. All questionnaires were self-reported and web-based. Data are also retrieved from the medical journals. The participation rate for the study was 20% but the cohort had a relatively low attrition rate, with 71% of the participants remaining in the study at 12 months follow-up 45 .

This study focuses on two subsets of variables from the BASIC study: and (i) background, medical history and pregnancy/delivery variables (BP) and (ii) further psychometric questionnaires (information on exact assessment methods and coding is provided in Table 1 for the background variables and Supplementary Table 1 for the exact questions in the different questionnaires). The BP variables consisted of sociodemographic and lifestyle information, self-reported health, medical history and variables relating to pregnancy and childbirth. This dataset included even information on depression and anxiety symptoms during pregnancy. Depression symptoms were assessed by a score of 12 or more on the Edinburg Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in pregnancy weeks 17, 32 or 38, while anxiety during pregnancy was defined as ratings in the highest quartile on either the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) 46 , the Beck Anxiety Inventory or the anxiety subscale of the EPDS (EPDS-3A). These variables were available for the majority of the BASIC participants. The total number of interpersonal and non-interpersonal events in the Lifetime Instances of Traumatic Events Scale (LITE) 47 was also included among BP variables. The BP variables consisted of continuous, discrete, nominal and ordinal categorical variables, measured at various time points during the study.

The extra psychometric scales used were the Attachment Style Questionnaire (ASQ) 48 , the Resilience-14 scale (RS) 49 , 50 , the Sense of Coherence Scale-29 (SOC) 51 , the Vulnerable Personality Style Questionnaire (VPSQ) 52 , 53 , and the Swedish Scale of Personalities (SSP) 54 . ASQ, RS, SOC, VPSQ, and SSP were filled out at gestational week 17 or 32, VPSQ and LITE assessments were conducted at 12 months postpartum. All variables were assessed on a Likert scale and coded as ordinal variables. These scales were used for only specific period of time during the course of the BASIC project, different for each scale, and are thus available for different number of women (Table 1 ) 45 .

Additionally, the participants of BASIC study were also asked to fill out the EPDS at different time-points during and after pregnancy. The outcome in this study was EPDS score at 6 weeks postpartum, assessing the degree of self-reported depressive symptoms in the early postpartum period. The discrete scores for this timepoint were then aggregated and a cut-off of a score of 12 or higher was used to indicate women with depressive symptoms, in accordance to validation studies for the Swedish population 55 . The number of women in the BASIC study who had completed the EPDS at 6 weeks postpartum and were thus included was 4313.

Ethics declarations

The study has been approved by the Research Ethics Board in Uppsala (Dnr 2009/171, with amendments). All participating women gave written informed consent before being included in the study. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Data pre-processing

The pre-processing consisted of splitting the original BASIC dataset into different subsets. Two subsets were retained for our study, i.e. background & pregnancy (BP) data and psychometric questionnaire data. Data for twins and women with multiple pregnancies were removed from the dataset, as these are relatively rare, are followed very closely during and after childbirth, and are associated with higher risk for PPD 56 , 57 . Explorative data analyses were conducted on individual variables to check their distributions and to identify and remove outliers that were assessed to be non-informative. Psychometric questionnaires and BP variables that contained information about the women after the time point of the outcome, namely 6 weeks postpartum, were also excluded to avoid inadvertent biases of the results.

SSP was omitted from the analysis due to large number of missing observations, as this survey was used only for few years during recruitment for the BASIC study 45 . Its inclusion would have resulted in a much smaller sample size for the final analysis.

The dataset consists of continuous, nominal and ordinal variables. As continuous variables in the dataset have varying scales, normalization is performed to transform all the variables to a common range from 0 to 1. Furthermore, nominal and ordinal variables that represent non-numerical values are encoded using binary numerical representations for improving the performance of the ML algorithms.

Data imputation

As missing values can drastically impact the performance of ML models, a conservative approach was adopted to handle them. Firstly, samples (rows, corresponding to one pregnancy) with more than 50% missing values in the included variables were eliminated, and the final number of pregnancies in the ML analyses was 4277. Next, variables (columns, corresponding to a distinct variable) with more than 25% missing data were also eliminated. Finally, the remaining missing values were imputed from the available data. While continuous variables were imputed using multivariate imputation by chained equations (MICE) 58 , categorical and ordinal variables were imputed with K nearest neighbors’ imputation 59 .

Classification techniques

With ML algorithms, there is no one-size-fits-all solution, making it imperative to try multiple alternatives. Consequently, this study explored different ML algorithms for supervised classification that modeled data in different ways. In order to present a comprehensive comparison, the following algorithms were implemented: Ridge Regression, LASSO Regression, Gradient Boosting Machines, Distributed Radom Forests, Extreme Randomized Forest, Naïve Bayes, and Stacked Ensembles. Ridge Regression specializes in analysing multiple regression data with multicollinearity, while LASSO Regression is a type of linear regression that shrinks data values towards a central point, and results in simple, sparse models (i.e. models with fewer parameters). Gradient Boosting Machines (GBM) and Random Forests are ensemble learners. In Distributed Radom Forests (DRF), a subset of features is used to determine the most discriminative thresholds to split the trees on. However, unlike DRF, where one builds an ensemble of deep independent trees, in GBM, we specify an ensemble of weak, shallow successive trees, where each tree is learning and improving on the previous tree. In Extremely Randomized Trees (XRT), instead of using the most discriminative thresholds for the splits, thresholds are drawn at random for each feature and the best of these random thresholds are used as the splitting rule, resulting in lower variance but more bias. XRT are similar to DRF with the caveat of more randomness. Naïve Bayes (NB) is a probabilistic classifier based on Bayes’ Theorem. The NB works under the assumption that the presence of any particular feature for a certain outcome is unrelated to the presence of any other feature for that outcome. Thus, despite if the features depend on each other or upon the existence of other features, the NB assumes that all of the features independently contribute to the outcome probability. Stacked Ensemble learns a new model by combining predictions of existing models. Stacked Ensembles are a class of supervised learning algorithms that work by training a meta-learner to find the optimal combination of base learners. Unlike bagging and boosting were the goal is to stack a number of weak learners together, the goal is to stack a number of diverse and strong learners together to optimize learning 60 .

For all the classification algorithms, the outcome measure was the participants’ EPDS score at 6 weeks postpartum represented as a binary variable with 12 as cut-off, while predictor variables included the BP variables and psychometric data described above.

Class imbalance

The BASIC dataset, as a population-based sample and in accordance to clinical situations, is predominantly composed of data from women who did not experience PPD at 6 weeks postpartum (less than 10% of the women representing PPD cases), consequently leading to extreme data class imbalance. ML classifiers trained on such imbalanced datasets usually generate biased results. To mitigate this imbalance, the minority class consisting of women with PPD was oversampled during ML training. Unlike under sampling of majority class consisting of women without PPD, this approach avoids loss of information and leverages all the samples from both classes.

Evaluation metrics

The performance of model prediction of the ML classification algorithms was evaluated using a variety of performance metrics. The performance of each classification model was captured by the Confusion Matrix that formed the basis for other metrics. In addition to the most commonly used classification accuracy, sensitivity (true positive rate) and specificity (false positive rate) are also reported. The positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) are also reported. Additionally, a Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve was specified for each classification to show the relation between the true positive rate and false positive rate. The performance of the classifiers was then summarized by the total area under the ROC curve (AUC), with the higher the AUC (between 0 and 1) indicating a better performance of the classification.

Variable (feature) importance/selection

The success of a ML algorithm does not only depend on good predictive performance but also on generalizability and easy interpretability. Identifying variables that have significant impact on the outcome is valuable, especially in the medical domain. Variable importance using Random Forests models can be calculated using Gini Importance or Mean Decrease in Impurity (MDI) 61 . The MDI relevance of a variable is obtained by calculating how effective the variable is at reducing the uncertainty when creating decision trees. The variable that is most effective and used the most will be ranked as most important.

Analytic strategy

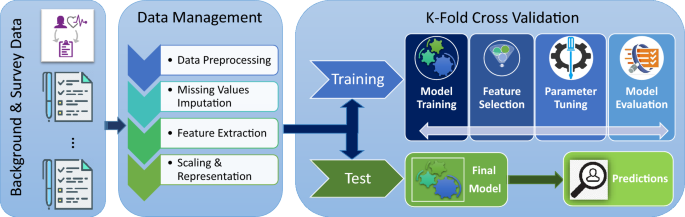

The analytical strategy consisted of breaking the analysis down into steps and iteratively building towards a final classification model, all the while being cognizant of any potential biases introduced by the approach. The workflow is presented in Fig. 7 . First, the raw data was split into the BP and the different psychometric questionnaires datasets in order to build predictive models independently on each psychometric questionnaire and to identify the ones with the highest accuracy for classification of PPD. Second, the psychometric questionnaires that yielded the highest accuracies were combined with the BP dataset. Predictions were then performed with the aggregate data (combined dataset). Additional models were trained with reduced datasets resulting from variable selection. Top 50% and top 25% variables with MDI were used to train separate classification models to determine the relative contribution of those variables to the prediction. Additionally, stratified analyses were performed, where participants were stratified by a previous history of depression (defined as earlier depression, earlier contact with psychiatrist/psychologist, or depression during pregnancy).

Study workflow and analytical strategy. Data were obtained from the “Biology, Affect, Stress, Imaging and Cognition during Pregnancy and the Puerperium” (BASIC) study, a population-based prospective cohort study in Uppsala, Sweden. Data included in our study comprised (i) background, medical history and pregnancy-related variables (BP) from women, and (ii) further psychometric questionnaires, available at discharge from the delivery ward. The data were processed and either were used to test models or train the machine learning algorithms, to predict depressive symptoms at 6 weeks postpartum.

Based on preliminary analyses, SSP and ASQ did not provide any information gain relative to BP data. Hence, only RS, SOC and VPSQ variables that provided predictive performances comparable to BP variables were included in the aggregate analysis.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request and after data transfer agreements are in place, according to current regulations.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5 5th edn. (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Book Google Scholar

Fitelson, E., Kim, S., Baker, A. S. & Leight, K. Treatment of postpartum depression: clinical, psychological and pharmacological options. Int. J. Womens Health 3 , 1–14. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S6938 (2010).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Patel, M. et al. Postpartum depression: a review. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 23 , 534–542. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2012.0037 (2012).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Yim, I. S., Tanner Stapleton, L. R., Guardino, C. M., Hahn-Holbrook, J. & Dunkel Schetter, C. Biological and psychosocial predictors of postpartum depression: systematic review and call for integration. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 11 , 99–137. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-101414-020426 (2015).

Bloch, M., Daly, R. C. & Rubinow, D. R. Endocrine factors in the etiology of postpartum depression. Compr. Psychiatry 44 , 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00034-8 (2003).

Asif, S. et al. Severe obstetric lacerations associated with postpartum depression among women with low resilience—a Swedish birth cohort study. BJOG https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.16271 (2020).

Iliadis, S. I. et al. Personality and risk for postpartum depressive symptoms. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 18 , 539–546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0478-8 (2015).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Committee on Obstetric Practice. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee opinion no. 630: screening for perinatal depression. Obstet. Gynecol. 125 , 1268–1271 (2015).

Article Google Scholar

Ko, J. Y., Rockhill, K. M., Tong, V. T., Morrow, B. & Farr, S. L. Trends in postpartum depressive symptoms—27 States, 2004, 2008, and 2012. MMWR Morb. Mortal Wkly. Rep. 66 , 153–158. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6606a1 (2017).

Dennis, C. L. & McQueen, K. The relationship between infant-feeding outcomes and postpartum depression: a qualitative systematic review. Pediatrics 123 , e736–e751. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-1629 (2009).

Slomian, J., Honvo, G., Emonts, P., Reginster, J.-Y. & Bruyère, O. Consequences of maternal postpartum depression: a systematic review of maternal and infant outcomes. Womens Health 15 , 174550651984404. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745506519844044 (2019).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Moore Simas, T. A. et al. Matched cohort study of healthcare resource utilization and costs in young children of mothers with postpartum depression in the United States. J. Med. Econ. 23 , 174–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/13696998.2019.1679157 (2020).

Murray, L., Woolgar, M., Cooper, P. & Hipwell, A. Cognitive vulnerability to depression in 5-year-old children of depressed mothers. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 42 , 891–899. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00785 (2001).

Nguyen, J. A literature review of alternative therapies for postpartum depression. Nurs. Womens Health 21 , 348–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nwh.2017.07.003 (2017).

The Management of Depression During Pregnancy. A report from the American Psychiatric Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet. Gynecol. 114 , 703–713. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181ba0632 (2009).

Dennis, C.-L. & Hodnett, E. D. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for treating postpartum depression. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006116.pub2 (2007).

Righetti-Veltema, M., Conne-Perréard, E., Bousquet, A. & Manzano, J. Risk factors and predictive signs of postpartum depression. J. Affect. Disord. 49 , 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-0327(97)00110-9 (1998).

Lee, Y. et al. Applications of machine learning algorithms to predict therapeutic outcomes in depression: a meta-analysis and systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 241 , 519–532. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.08.073 (2018).

Bzdok, D. & Meyer-Lindenberg, A. Machine learning for precision psychiatry: opportunities and challenges. Biol. Psychiatry Cognit. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 3 , 223–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2017.11.007 (2018).

Friston, K. J., Redish, A. D. & Gordon, J. A. Computational nosology and precision psychiatry. Comput. Psychiatry 1 , 2–23. https://doi.org/10.1162/CPSY_a_00001 (2017).

Rohart, F., Gautier, B., Singh, A. & Lê Cao, K.-A. mixOmics: an R package for ‘omics feature selection and multiple data integration. PLOS Comput. Biol. 13 , e1005752. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005752 (2017).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central ADS Google Scholar

Ahmed, F. E. Artificial neural networks for diagnosis and survival prediction in colon cancer. Mol. Cancer 4 , 29 (2005).

Anagnostou, T., Remzi, M., Lykourinas, M. & Djavan, B. Artificial neural networks for decision-making in urologic oncology. Eur. Urol. 43 , 596–603 (2003).

Jerez, J. et al. Improvement of breast cancer relapse prediction in high risk intervals using artificial neural networks. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 94 , 265–272 (2005).

Suzuki, K., Li, F., Sone, S. & Doi, K. Computer-aided diagnostic scheme for distinction between benign and malignant nodules in thoracic low-dose CT by use of massive training artificial neural network. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 24 , 1138–1150 (2005).

Baxt, W. G., Shofer, F. S., Sites, F. D. & Hollander, J. E. A neural computational aid to the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. Ann. Emerg. Med. 39 , 366–373 (2002).

Zini, G. Artificial intelligence in hematology. Hematology 10 , 393–400 (2005).

Bent, P. et al. Early and intensive continuous hemofiltration for severe renal failure after cardiac surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 71 , 832–837 (2001).

Huang, L., Yu, P., Ju, F. & Cheng, J. Prediction of response to incision using the mutual information of electroencephalograms during anaesthesia. Med. Eng. Phys. 25 , 321–327 (2003).

Choi, J., Choi, J. & Jung, H.-T. Applying machine-learning techniques to build self-reported depression prediction models. CIN Comput. Inform. Nurs. 36 , 317–321. https://doi.org/10.1097/CIN.0000000000000463 (2018).

Gao, S., Calhoun, V. D. & Sui, J. Machine learning in major depression: from classification to treatment outcome prediction. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 24 , 1037–1052. https://doi.org/10.1111/cns.13048 (2018).

Graham, S. et al. Artificial intelligence for mental health and mental illnesses: an overview. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 21 , 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-019-1094-0 (2019).

Helbich, M., Hagenauer, J. & Roberts, H. Relative importance of perceived physical and social neighborhood characteristics for depression: a machine learning approach. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01808-5 (2019).

Wang, S., Pathak, J. & Zhang, Y. Using electronic health records and machine learning to predict postpartum depression. Stud. Health Technol. Inform. 264 , 888–892. https://doi.org/10.3233/SHTI190351 (2019).

Tai, A. M. Y. et al. Machine learning and big data: implications for disease modeling and therapeutic discovery in psychiatry. Artif. Intell. Med. 99 , 101704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.artmed.2019.101704 (2019).

Tortajada, S. et al. Prediction of postpartum depression using multilayer perceptrons and pruning. Methods Inf. Med. 48 , 291–298. https://doi.org/10.3414/ME0562 (2009).

Jiménez-Serrano, S., Tortajada, S. & García-Gómez, J. M. A mobile health application to predict postpartum depression based on machine learning. Telemed. e-Health 21 , 567–574. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2014.0113 (2015).

Zhang, W., Liu, H., Silenzio, V. M. B., Qiu, P. & Gong, W. Machine learning models for the prediction of postpartum depression: application and comparison based on a cohort study. JMIR Med. Inform. 8 , e15516. https://doi.org/10.2196/15516 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Wang, S., Hermann, A., Joly, R. & Pathak, J. Development and validation of a machine learning algorithm for predicting the risk of postpartum depression among pregnant women. J. Affect. Disord. 279 , 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.09.113 (2021).

Luca, D. L., Garlow, N., Staatz, C., Margiotta, C. & Zivin, K. Societal Costs of Untreated Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders in the United States (Mathematica Policy Research, 2019).

Google Scholar

Levis, B., Negeri, Z., Sun, Y., Benedetti, A. & Thombs, B. D. Accuracy of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) for screening to detect major depression among pregnant and postpartum women: systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data. BMJ 371 , m4022. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m4022 (2020).

Siu, A. L. & Force, A. T. U. P. S. T. Screening for depression in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA 315 , 380–387. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.18392 (2016).

National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (UK). Antenatal and Postnatal Mental Health: Clinical Management and Service Guidance: Updated Edition (NICE Clinical Guidelines, No. 192. 5, CASE IDENTIFICATION AND ASSESSMENT, British Psychological Society, 2014).

Austin, M. P., Highet, N. & Group, E. W. Mental Health Care in the Perinatal Period: Australian Clinical Practice Guideline (Centre of Perinatal Excellence, 2017).

Axfors, C. et al. Cohort profile: the Biology, Affect, Stress, Imaging and Cognition (BASIC) study on perinatal depression in a population-based Swedish cohort. BMJ Open 9 , e031514. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031514 (2019).

Spielberger, C. D. State‐trait anxiety inventory. In The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology , 1. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0943 (2010).

Greenwald, R. & Rubin, A. Assessment of posttraumatic symptoms in children: development and preliminary validation of parent and child scales. Res. Soc. Work Pract. 9 , 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973159900900105 (1999).

Feeney, J., Noller, P. & Hanrahan, M. Assessing adult attachment. In Attachment in Adults: Clinical and Developmental Perspectives (eds Sperling, M. B. & Berman, W. H.) 128–151 (The Guilford Press, New York, 1994).

Aiena, B. J., Baczwaski, B. J., Schulenberg, S. E. & Buchanan, E. M. Measuring resilience with the RS–14: a tale of two samples. J. Pers. Assess. 97 , 291–300 (2015).

Wagnild, G. M. & Young, H. M. Development and psychometric evaluation of the resilience scale. J. Nurs. Meas. 1 , 165–178 (1993).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Antonovsky, A. The structure and properties of the sense of coherence scale. Soc. Sci. Med. 36 , 725–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(93)90033-Z (1993).

Boyce, P., Hickey, A., Gilchrist, J. & Talley, N. J. The development of a brief personality scale to measure vulnerability to postnatal depression. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 3 , 147–153. https://doi.org/10.1007/s007370170012 (2001).

Gelabert, E. et al. The vulnerable personality style questionnaire: psychometric properties in Spanish postpartum women. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 14 , 115–124 (2011).

Gustavsson, J. P. et al. Swedish universities Scales of Personality (SSP): construction, internal consistency and normative data. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 102 , 217–225. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102003217.x (2000).

Wickberg, B. & Hwang, C. P. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: validation on a Swedish community sample. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 94 , 181–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09845.x (1996).

Vilska, S. et al. Mental health of mothers and fathers of twins conceived via assisted reproduction treatment: a 1-year prospective study. Hum. Reprod. 24 , 367–377. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/den427 (2009).

Wenze, S. J., Battle, C. L. & Tezanos, K. M. Raising multiples: mental health of mothers and fathers in early parenthood. Arch. Womens Ment. Health 18 , 163–176. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-014-0484-x (2015).

Azur, M. J., Stuart, E. A., Frangakis, C. & Leaf, P. J. Multiple imputation by chained equations: what is it and how does it work?: Multiple imputation by chained equations. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 20 , 40–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.329 (2011).

Beretta, L. & Santaniello, A. Nearest neighbor imputation algorithms: a critical evaluation. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Mak. 16 (Suppl 3), 74. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-016-0318-z (2016).

van der Laan, M. J., Polley, E. C. & Hubbard, A. E. Super learner. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. https://doi.org/10.2202/1544-6115.1309 (2007).

Article MathSciNet PubMed PubMed Central MATH Google Scholar

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R. & Friedman, J. H. The Elements of Statistical Learning: Data Mining, Inference, and Prediction 2nd edn. (Springer, 2009).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Anastasia Kollia, Hanna Henriksson and Emma Bränn for valuable insights and help with data collection and management in the BASIC study. Marina Krylova, Nils Kroemer, and Hamidreza Jamalabadi for valuable insights and assistance in the initial phase of the analyses planning. Dr. Narayanan Chatapuram Krishnan for his excellent machine learning course. Subhranil Bagchi for time spent aiding in coding and students at IIT Ropar for their insights and help with coding and theoretical discussions. Prof. Inger Sundström Poromaa, Ass. Prof. Fotios Papadopoulos and all colleagues working in the BASIC research group for their contribution with critical comments and discussions. Finally, the authors would like to sincerely thank Dr. Diem Nguyen for language editing and comments.

Open access funding provided by Uppsala University. This study has been supported by the municipality of Uppsala and Akademiska University Hospital in Sweden, the Swedish Research foundation (523-2014-2342 and 523-2014-07605), Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg foundation and the Swedish Medical Association.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Women’s and Children’s Health, Uppsala University, 751 85, Uppsala, Sweden

Sam Andersson, Stavros I. Iliadis & Alkistis Skalkidou

Department of Computer Science and Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Ropar, Rupnagar, Punjab, 140001, India

Deepti R. Bathula

Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University Hospital Jena, Jena, Germany

Martin Walter

Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Eberhardt Karls University, Tübingen, Germany

Department of Behavioral Neurology, Leibniz Institute for Neurobiology, Magdeburg, Germany

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

A.S. conceived and designed the study. The analysis plan was decided on with the contribution of all authors. Analyses were performed by D.R.B., S.A., and S.I.I. S.A., D.R.B., and S.I.I. prepared the figures and tables. All authors made substantial contributions to the interpretation of results. S.A. wrote the first draft and all authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Alkistis Skalkidou .

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary informations., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Andersson, S., Bathula, D.R., Iliadis, S.I. et al. Predicting women with depressive symptoms postpartum with machine learning methods. Sci Rep 11 , 7877 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86368-y

Download citation

Received : 16 September 2020

Accepted : 15 March 2021

Published : 12 April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-86368-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Enhancing explainability in predicting mental health disorders using human–machine interaction.

- Inderpreet Kaur

- Umesh Gupta

Multimedia Tools and Applications (2024)

Unveiling the prevalence and risk factors of early stage postpartum depression: a hybrid deep learning approach

- Umesh Kumar Lilhore

- Surjeet Dalal

- Arshad Hashmi

Wife-Mother Role Conflict at the Critical Child-Rearing Stage: A Machine-Learning Approach to Identify What and How Matters in Maternal Depression Symptoms in China

- Liuzhi Hong

Prevention Science (2023)

Prenatal and Childbirth Risk Factors of Postpartum Pain and Depression: A Machine Learning Approach

- McClain Sampson

Maternal and Child Health Journal (2023)

- Trine Munk-Olsen

- Xiaoqin Liu

- Merete L. Maegbaek

Translational Psychiatry (2022)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Kujawa leads study to predict postpartum depression by examining brain function throughout pregnancy

Media Inquiries

- 615-322-6397 Email

Latest Stories

- Limited Submission Opportunity: 2024 Creating Equitable Pathways to STEM Graduate Education Program

- Vanderbilt Law announces launch of Undergraduate Minor in Legal Studies

- Two A&S psychology faculty receive prestigious awards in vision sciences

Jan 30, 2024, 12:02 PM

By Jenna Somers

A five-year, nearly $3.6 million grant from the National Institute of Mental Health will support Autumn Kujawa , associate professor of psychology and human development at Vanderbilt Peabody College of education and human development , and her team in examining changes in brain processes throughout pregnancy to understand whether and to what extent these changes predict postpartum depression. Establishing an understanding of the early predictors for postpartum depression could support the development of timely and targeted treatments for high-risk patients during pregnancy to address symptoms before they develop or when they begin to appear.

Postpartum depression has profound negative effects on mothers, their children, and the mother-child relationship, creating an urgent need to better understand risk and to help to inform prevention efforts. Previous research by Kujawa and others demonstrates that, outside of pregnancy, low activation of positive emotions systems and reward responsiveness in the brain predict future depressive symptoms. When functioning normally, these systems also support social motivation in mother-infant relationships. However, pregnancy can greatly affect the function of positive emotions systems and reward responsiveness due to rapid hormonal fluctuations and increased stress associated with dramatic changes in roles, expectations, and relationships. With this understanding, Kujawa theorizes that low positive emotions systems functioning during pregnancy could predict increased risk for postpartum depression.

“If we can better understand some of these mechanisms of peripartum depression, we might be able to adapt interventions from our study with mothers and older children for pregnant and postpartum people to focus on increasing positive emotions, particularly in the context of caregiving and establishing a relationship with a new baby,” Kujawa said. “We’re also interested in the timing for predicting risk—how early in pregnancy can we observe markers of risk for later symptoms? That could help to determine when to administer assessments and intervene.”

Kujawa and her team will conduct longitudinal assessments with 300 pregnant participants across the peripartum period (15 weeks gestation to five weeks postpartum) to examine trajectories of positive emotions systems function, whether it influences mother-infant interactions, and explore biological and social processes shaping risk for postpartum depression. At 15 weeks postpartum, mothers and infants will participate in an observed free play interaction to assess mutual enjoyment. Depressive symptoms and diagnoses will be assessed from 15 weeks gestation through 25 weeks postpartum.