An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Afr J Emerg Med

- v.7(3); 2017 Sep

A hands-on guide to doing content analysis

Christen erlingsson.

a Department of Health and Caring Sciences, Linnaeus University, Kalmar 391 82, Sweden

Petra Brysiewicz

b School of Nursing & Public Health, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban 4041, South Africa

Associated Data

There is a growing recognition for the important role played by qualitative research and its usefulness in many fields, including the emergency care context in Africa. Novice qualitative researchers are often daunted by the prospect of qualitative data analysis and thus may experience much difficulty in the data analysis process. Our objective with this manuscript is to provide a practical hands-on example of qualitative content analysis to aid novice qualitative researchers in their task.

African relevance

- • Qualitative research is useful to deepen the understanding of the human experience.

- • Novice qualitative researchers may benefit from this hands-on guide to content analysis.

- • Practical tips and data analysis templates are provided to assist in the analysis process.

Introduction

There is a growing recognition for the important role played by qualitative research and its usefulness in many fields, including emergency care research. An increasing number of health researchers are currently opting to use various qualitative research approaches in exploring and describing complex phenomena, providing textual accounts of individuals’ “life worlds”, and giving voice to vulnerable populations our patients so often represent. Many articles and books are available that describe qualitative research methods and provide overviews of content analysis procedures [1] , [2] , [3] , [4] , [5] , [6] , [7] , [8] , [9] , [10] . Some articles include step-by-step directions intended to clarify content analysis methodology. What we have found in our teaching experience is that these directions are indeed very useful. However, qualitative researchers, especially novice researchers, often struggle to understand what is happening on and between steps, i.e., how the steps are taken.

As research supervisors of postgraduate health professionals, we often meet students who present brilliant ideas for qualitative studies that have potential to fill current gaps in the literature. Typically, the suggested studies aim to explore human experience. Research questions exploring human experience are expediently studied through analysing textual data e.g., collected in individual interviews, focus groups, documents, or documented participant observation. When reflecting on the proposed study aim together with the student, we often suggest content analysis methodology as the best fit for the study and the student, especially the novice researcher. The interview data are collected and the content analysis adventure begins. Students soon realise that data based on human experiences are complex, multifaceted and often carry meaning on multiple levels.

For many novice researchers, analysing qualitative data is found to be unexpectedly challenging and time-consuming. As they soon discover, there is no step-wise analysis process that can be applied to the data like a pattern cutter at a textile factory. They may become extremely annoyed and frustrated during the hands-on enterprise of qualitative content analysis.

The novice researcher may lament, “I’ve read all the methodology but don’t really know how to start and exactly what to do with my data!” They grapple with qualitative research terms and concepts, for example; differences between meaning units, codes, categories and themes, and regarding increasing levels of abstraction from raw data to categories or themes. The content analysis adventure may now seem to be a chaotic undertaking. But, life is messy, complex and utterly fascinating. Experiencing chaos during analysis is normal. Good advice for the qualitative researcher is to be open to the complexity in the data and utilise one’s flow of creativity.

Inspired primarily by descriptions of “conventional content analysis” in Hsieh and Shannon [3] , “inductive content analysis” in Elo and Kyngäs [5] and “qualitative content analysis of an interview text” in Graneheim and Lundman [1] , we have written this paper to help the novice qualitative researcher navigate the uncertainty in-between the steps of qualitative content analysis. We will provide advice and practical tips, as well as data analysis templates, to attempt to ease frustration and hopefully, inspire readers to discover how this exciting methodology contributes to developing a deeper understanding of human experience and our professional contexts.

Overview of qualitative content analysis

Synopsis of content analysis.

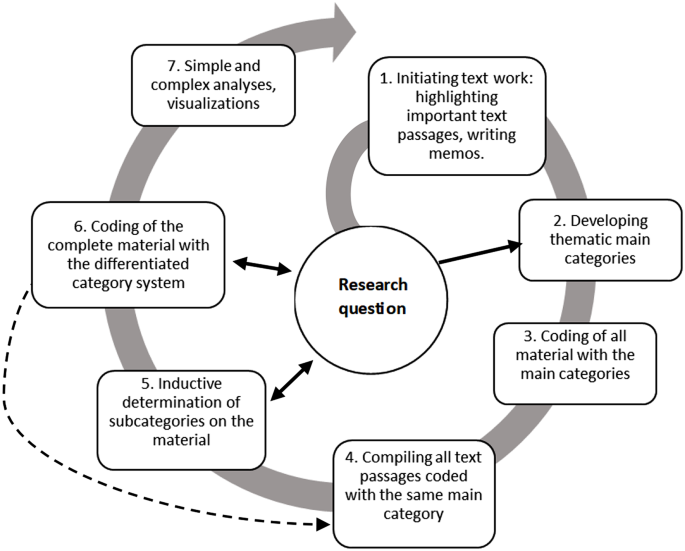

A common starting point for qualitative content analysis is often transcribed interview texts. The objective in qualitative content analysis is to systematically transform a large amount of text into a highly organised and concise summary of key results. Analysis of the raw data from verbatim transcribed interviews to form categories or themes is a process of further abstraction of data at each step of the analysis; from the manifest and literal content to latent meanings ( Fig. 1 and Table 1 ).

Example of analysis leading to higher levels of abstraction; from manifest to latent content.

Glossary of terms as used in this hands-on guide to doing content analysis. *

The initial step is to read and re-read the interviews to get a sense of the whole, i.e., to gain a general understanding of what your participants are talking about. At this point you may already start to get ideas of what the main points or ideas are that your participants are expressing. Then one needs to start dividing up the text into smaller parts, namely, into meaning units. One then condenses these meaning units further. While doing this, you need to ensure that the core meaning is still retained. The next step is to label condensed meaning units by formulating codes and then grouping these codes into categories. Depending on the study’s aim and quality of the collected data, one may choose categories as the highest level of abstraction for reporting results or you can go further and create themes [1] , [2] , [3] , [5] , [8] .

Content analysis as a reflective process

You must mould the clay of the data , tapping into your intuition while maintaining a reflective understanding of how your own previous knowledge is influencing your analysis, i.e., your pre-understanding. In qualitative methodology, it is imperative to vigilantly maintain an awareness of one’s pre-understanding so that this does not influence analysis and/or results. This is the difficult balancing task of keeping a firm grip on one’s assumptions, opinions, and personal beliefs, and not letting them unconsciously steer your analysis process while simultaneously, and knowingly, utilising one’s pre-understanding to facilitate a deeper understanding of the data.

Content analysis, as in all qualitative analysis, is a reflective process. There is no “step 1, 2, 3, done!” linear progression in the analysis. This means that identifying and condensing meaning units, coding, and categorising are not one-time events. It is a continuous process of coding and categorising then returning to the raw data to reflect on your initial analysis. Are you still satisfied with the length of meaning units? Do the condensed meaning units and codes still “fit” with each other? Do the codes still fit into this particular category? Typically, a fair amount of adjusting is needed after the first analysis endeavour. For example: a meaning unit might need to be split into two meaning units in order to capture an additional core meaning; a code modified to more closely match the core meaning of the condensed meaning unit; or a category name tweaked to most accurately describe the included codes. In other words, analysis is a flexible reflective process of working and re-working your data that reveals connections and relationships. Once condensed meaning units are coded it is easier to get a bigger picture and see patterns in your codes and organise codes in categories.

Content analysis exercise

The synopsis above is representative of analysis descriptions in many content analysis articles. Although correct, such method descriptions still do not provide much support for the novice researcher during the actual analysis process. Aspiring to provide guidance and direction to support the novice, a practical example of doing the actual work of content analysis is provided in the following sections. This practical example is based on a transcribed interview excerpt that was part of a study that aimed to explore patients’ experiences of being admitted into the emergency centre ( Fig. 2 ).

Excerpt from interview text exploring “Patient’s experience of being admitted into the emergency centre”

This content analysis exercise provides instructions, tips, and advice to support the content analysis novice in a) familiarising oneself with the data and the hermeneutic spiral, b) dividing up the text into meaning units and subsequently condensing these meaning units, c) formulating codes, and d) developing categories and themes.

Familiarising oneself with the data and the hermeneutic spiral

An important initial phase in the data analysis process is to read and re-read the transcribed interview while keeping your aim in focus. Write down your initial impressions. Embrace your intuition. What is the text talking about? What stands out? How did you react while reading the text? What message did the text leave you with? In this analysis phase, you are gaining a sense of the text as a whole.

You may ask why this is important. During analysis, you will be breaking down the whole text into smaller parts. Returning to your notes with your initial impressions will help you see if your “parts” analysis is matching up with your first impressions of the “whole” text. Are your initial impressions visible in your analysis of the parts? Perhaps you need to go back and check for different perspectives. This is what is referred to as the hermeneutic spiral or hermeneutic circle. It is the process of comparing the parts to the whole to determine whether impressions of the whole verify the analysis of the parts in all phases of analysis. Each part should reflect the whole and the whole should be reflected in each part. This concept will become clearer as you start working with your data.

Dividing up the text into meaning units and condensing meaning units

You have now read the interview a number of times. Keeping your research aim and question clearly in focus, divide up the text into meaning units. Located meaning units are then condensed further while keeping the central meaning intact ( Table 2 ). The condensation should be a shortened version of the same text that still conveys the essential message of the meaning unit. Sometimes the meaning unit is already so compact that no further condensation is required. Some content analysis sources warn researchers against short meaning units, claiming that this can lead to fragmentation [1] . However, our personal experience as research supervisors has shown us that a greater problem for the novice is basing analysis on meaning units that are too large and include many meanings which are then lost in the condensation process.

Suggestion for how the exemplar interview text can be divided into meaning units and condensed meaning units ( condensations are in parentheses ).

Formulating codes

The next step is to develop codes that are descriptive labels for the condensed meaning units ( Table 3 ). Codes concisely describe the condensed meaning unit and are tools to help researchers reflect on the data in new ways. Codes make it easier to identify connections between meaning units. At this stage of analysis you are still keeping very close to your data with very limited interpretation of content. You may adjust, re-do, re-think, and re-code until you get to the point where you are satisfied that your choices are reasonable. Just as in the initial phase of getting to know your data as a whole, it is also good to write notes during coding on your impressions and reactions to the text.

Suggestions for coding of condensed meaning units.

Developing categories and themes

The next step is to sort codes into categories that answer the questions who , what , when or where? One does this by comparing codes and appraising them to determine which codes seem to belong together, thereby forming a category. In other words, a category consists of codes that appear to deal with the same issue, i.e., manifest content visible in the data with limited interpretation on the part of the researcher. Category names are most often short and factual sounding.

In data that is rich with latent meaning, analysis can be carried on to create themes. In our practical example, we have continued the process of abstracting data to a higher level, from category to theme level, and developed three themes as well as an overarching theme ( Table 4 ). Themes express underlying meaning, i.e., latent content, and are formed by grouping two or more categories together. Themes are answering questions such as why , how , in what way or by what means? Therefore, theme names include verbs, adverbs and adjectives and are very descriptive or even poetic.

Suggestion for organisation of coded meaning units into categories and themes.

Some reflections and helpful tips

Understand your pre-understandings.

While conducting qualitative research, it is paramount that the researcher maintains a vigilance of non-bias during analysis. In other words, did you remain aware of your pre-understandings, i.e., your own personal assumptions, professional background, and previous experiences and knowledge? For example, did you zero in on particular aspects of the interview on account of your profession (as an emergency doctor, emergency nurse, pre-hospital professional, etc.)? Did you assume the patient’s gender? Did your assumptions affect your analysis? How about aspects of culpability; did you assume that this patient was at fault or that this patient was a victim in the crash? Did this affect how you analysed the text?

Staying aware of one’s pre-understandings is exactly as difficult as it sounds. But, it is possible and it is requisite. Focus on putting yourself and your pre-understandings in a holding pattern while you approach your data with an openness and expectation of finding new perspectives. That is the key: expect the new and be prepared to be surprised. If something in your data feels unusual, is different from what you know, atypical, or even odd – don’t by-pass it as “wrong”. Your reactions and intuitive responses are letting you know that here is something to pay extra attention to, besides the more comfortable condensing and coding of more easily recognisable meaning units.

Use your intuition

Intuition is a great asset in qualitative analysis and not to be dismissed as “unscientific”. Intuition results from tacit knowledge. Just as tacit knowledge is a hallmark of great clinicians [11] , [12] ; it is also an invaluable tool in analysis work [13] . Literally, take note of your gut reactions and intuitive guidance and remember to write these down! These notes often form a framework of possible avenues for further analysis and are especially helpful as you lift the analysis to higher levels of abstraction; from meaning units to condensed meaning units, to codes, to categories and then to the highest level of abstraction in content analysis, themes.

Aspects of coding and categorising hard to place data

All too often, the novice gets overwhelmed by interview material that deals with the general subject matter of the interview, but doesn’t seem to answer the research question. Don’t be too quick to consider such text as off topic or dross [6] . There is often data that, although not seeming to match the study aim precisely, is still important for illuminating the problem area. This can be seen in our practical example about exploring patients’ experiences of being admitted into the emergency centre. Initially the participant is describing the accident itself. While not directly answering the research question, the description is important for understanding the context of the experience of being admitted into the emergency centre. It is very common that participants will “begin at the beginning” and prologue their narratives in order to create a context that sets the scene. This type of contextual data is vital for gaining a deepened understanding of participants’ experiences.

In our practical example, the participant begins by describing the crash and the rescue, i.e., experiences leading up to and prior to admission to the emergency centre. That is why we have chosen in our analysis to code the condensed meaning unit “Ambulance staff looked worried about all the blood” as “In the ambulance” and place it in the category “Reliving the rescue”. We did not choose to include this meaning unit in the categories specifically about admission to the emergency centre itself. Do you agree with our coding choice? Would you have chosen differently?

Another common problem for the novice is deciding how to code condensed meaning units when the unit can be labelled in several different ways. At this point researchers usually groan and wish they had thought to ask one of those classic follow-up questions like “Can you tell me a little bit more about that?” We have examples of two such coding conundrums in the exemplar, as can be seen in Table 3 (codes we conferred on) and Table 4 (codes we reached consensus on). Do you agree with our choices or would you have chosen different codes? Our best advice is to go back to your impressions of the whole and lean into your intuition when choosing codes that are most reasonable and best fit your data.

A typical problem area during categorisation, especially for the novice researcher, is overlap between content in more than one initial category, i.e., codes included in one category also seem to be a fit for another category. Overlap between initial categories is very likely an indication that the jump from code to category was too big, a problem not uncommon when the data is voluminous and/or very complex. In such cases, it can be helpful to first sort codes into narrower categories, so-called subcategories. Subcategories can then be reviewed for possibilities of further aggregation into categories. In the case of a problematic coding, it is advantageous to return to the meaning unit and check if the meaning unit itself fits the category or if you need to reconsider your preliminary coding.

It is not uncommon to be faced by thorny problems such as these during coding and categorisation. Here we would like to reiterate how valuable it is to have fellow researchers with whom you can discuss and reflect together with, in order to reach consensus on the best way forward in your data analysis. It is really advantageous to compare your analysis with meaning units, condensations, coding and categorisations done by another researcher on the same text. Have you identified the same meaning units? Do you agree on coding? See similar patterns in the data? Concur on categories? Sometimes referred to as “researcher triangulation,” this is actually a key element in qualitative analysis and an important component when striving to ensure trustworthiness in your study [14] . Qualitative research is about seeking out variations and not controlling variables, as in quantitative research. Collaborating with others during analysis lets you tap into multiple perspectives and often makes it easier to see variations in the data, thereby enhancing the quality of your results as well as contributing to the rigor of your study. It is important to note that it is not necessary to force consensus in the findings but one can embrace these variations in interpretation and use that to capture the richness in the data.

Yet there are times when neither openness, pre-understanding, intuition, nor researcher triangulation does the job; for example, when analysing an interview and one is simply confused on how to code certain meaning units. At such times, there are a variety of options. A good starting place is to re-read all the interviews through the lens of this specific issue and actively search for other similar types of meaning units you might have missed. Another way to handle this is to conduct further interviews with specific queries that hopefully shed light on the issue. A third option is to have a follow-up interview with the same person and ask them to explain.

Additional tips

It is important to remember that in a typical project there are several interviews to analyse. Codes found in a single interview serve as a starting point as you then work through the remaining interviews coding all material. Form your categories and themes when all project interviews have been coded.

When submitting an article with your study results, it is a good idea to create a table or figure providing a few key examples of how you progressed from the raw data of meaning units, to condensed meaning units, coding, categorisation, and, if included, themes. Providing such a table or figure supports the rigor of your study [1] and is an element greatly appreciated by reviewers and research consumers.

During the analysis process, it can be advantageous to write down your research aim and questions on a sheet of paper that you keep nearby as you work. Frequently referring to your aim can help you keep focused and on track during analysis. Many find it helpful to colour code their transcriptions and write notes in the margins.

Having access to qualitative analysis software can be greatly helpful in organising and retrieving analysed data. Just remember, a computer does not analyse the data. As Jennings [15] has stated, “… it is ‘peopleware,’ not software, that analyses.” A major drawback is that qualitative analysis software can be prohibitively expensive. One way forward is to use table templates such as we have used in this article. (Three analysis templates, Templates A, B, and C, are provided as supplementary online material ). Additionally, the “find” function in word processing programmes such as Microsoft Word (Redmond, WA USA) facilitates locating key words, e.g., in transcribed interviews, meaning units, and codes.

Lessons learnt/key points

From our experience with content analysis we have learnt a number of important lessons that may be useful for the novice researcher. They are:

- • A method description is a guideline supporting analysis and trustworthiness. Don’t get caught up too rigidly following steps. Reflexivity and flexibility are just as important. Remember that a method description is a tool helping you in the process of making sense of your data by reducing a large amount of text to distil key results.

- • It is important to maintain a vigilant awareness of one’s own pre-understandings in order to avoid bias during analysis and in results.

- • Use and trust your own intuition during the analysis process.

- • If possible, discuss and reflect together with other researchers who have analysed the same data. Be open and receptive to new perspectives.

- • Understand that it is going to take time. Even if you are quite experienced, each set of data is different and all require time to analyse. Don’t expect to have all the data analysis done over a weekend. It may take weeks. You need time to think, reflect and then review your analysis.

- • Keep reminding yourself how excited you have felt about this area of research and how interesting it is. Embrace it with enthusiasm!

- • Let it be chaotic – have faith that some sense will start to surface. Don’t be afraid and think you will never get to the end – you will… eventually!

Peer review under responsibility of African Federation for Emergency Medicine.

Appendix A Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.afjem.2017.08.001 .

Appendix A. Supplementary data

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

19 Content Analysis

Lindsay Prior, School of Sociology, Social Policy, and Social Work, Queen's University

- Published: 02 September 2020

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In this chapter, the focus is on ways in which content analysis can be used to investigate and describe interview and textual data. The chapter opens with a contextualization of the method and then proceeds to an examination of the role of content analysis in relation to both quantitative and qualitative modes of social research. Following the introductory sections, four kinds of data are subjected to content analysis. These include data derived from a sample of qualitative interviews ( N = 54), textual data derived from a sample of health policy documents ( N = 6), data derived from a single interview relating to a “case” of traumatic brain injury, and data gathered from fifty-four abstracts of academic papers on the topic of “well-being.” Using a distinctive and somewhat novel style of content analysis that calls on the notion of semantic networks, the chapter shows how the method can be used either independently or in conjunction with other forms of inquiry (including various styles of discourse analysis) to analyze data and also how it can be used to verify and underpin claims that arise from analysis. The chapter ends with an overview of the different ways in which the study of “content”—especially the study of document content—can be positioned in social scientific research projects.

What Is Content Analysis?

In his 1952 text on the subject of content analysis, Bernard Berelson traced the origins of the method to communication research and then listed what he called six distinguishing features of the approach. As one might expect, the six defining features reflect the concerns of social science as taught in the 1950s, an age in which the calls for an “objective,” “systematic,” and “quantitative” approach to the study of communication data were first heard. The reference to the field of “communication” was nothing less than a reflection of a substantive social scientific interest over the previous decades in what was called public opinion and specifically attempts to understand why and how a potential source of critical, rational judgment on political leaders (i.e., the views of the public) could be turned into something to be manipulated by dictators and demagogues. In such a context, it is perhaps not so surprising that in one of the more popular research methods texts of the decade, the terms content analysis and communication analysis are used interchangeably (see Goode & Hatt, 1952 , p. 325).

Academic fashions and interests naturally change with available technology, and these days we are more likely to focus on the individualization of communications through Twitter and the like, rather than of mass newspaper readership or mass radio audiences, yet the prevailing discourse on content analysis has remained much the same as it was in Berleson’s day. Thus, Neuendorf ( 2002 ), for example, continued to define content analysis as “the systematic, objective, quantitative analysis of message characteristics” (p. 1). Clearly, the centrality of communication as a basis for understanding and using content analysis continues to hold, but in this chapter I will try to show that, rather than locate the use of content analysis in disembodied “messages” and distantiated “media,” we would do better to focus on the fact that communication is a building block of social life itself and not merely a system of messages that are transmitted—in whatever form—from sender to receiver. To put that statement in another guise, we must note that communicative action (to use the phraseology of Habermas, 1987 ) rests at the very base of the lifeworld, and one very important way of coming to grips with that world is to study the content of what people say and write in the course of their everyday lives.

My aim is to demonstrate various ways in which content analysis (henceforth CTA) can be used and developed to analyze social scientific data as derived from interviews and documents. It is not my intention to cover the history of CTA or to venture into forms of literary analysis or to demonstrate each and every technique that has ever been deployed by content analysts. (Many of the standard textbooks deal with those kinds of issues much more fully than is possible here. See, for example, Babbie, 2013 ; Berelson, 1952 ; Bryman, 2008 , Krippendorf, 2004 ; Neuendorf, 2002 ; and Weber, 1990 ). Instead, I seek to recontextualize the use of the method in a framework of network thinking and to link the use of CTA to specific problems of data analysis. As will become evident, my exposition of the method is grounded in real-world problems. Those problems are drawn from my own research projects and tend to reflect my academic interests—which are almost entirely related to the analysis of the ways in which people talk and write about aspects of health, illness, and disease. However, lest the reader be deterred from going any further, I should emphasize that the substantive issues that I elect to examine are secondary if not tertiary to my main objective—which is to demonstrate how CTA can be integrated into a range of research designs and add depth and rigor to the analysis of interview and inscription data. To that end, in the next section I aim to clear our path to analysis by dealing with some issues that touch on the general position of CTA in the research armory, especially its location in the schism that has developed between quantitative and qualitative modes of inquiry.

The Methodological Context of Content Analysis

Content analysis is usually associated with the study of inscription contained in published reports, newspapers, adverts, books, web pages, journals, and other forms of documentation. Hence, nearly all of Berelson’s ( 1952 ) illustrations and references to the method relate to the analysis of written records of some kind, and where speech is mentioned, it is almost always in the form of broadcast and published political speeches (such as State of the Union addresses). This association of content analysis with text and documentation is further underlined in modern textbook discussions of the method. Thus, Bryman ( 2008 ), for example, defined CTA as “an approach to the analysis of documents and texts , that seek to quantify content in terms of pre-determined categories” (2008, p. 274, emphasis in original), while Babbie ( 2013 ) stated that CTA is “the study of recorded human communications” (2013, p. 295), and Weber referred to it as a method to make “valid inferences from text” (1990, p. 9). It is clear then that CTA is viewed as a text-based method of analysis, though extensions of the method to other forms of inscriptional material are also referred to in some discussions. Thus, Neuendorf ( 2002 ), for example, rightly referred to analyses of film and television images as legitimate fields for the deployment of CTA and by implication analyses of still—as well as moving—images such as photographs and billboard adverts. Oddly, in the traditional or standard paradigm of CTA, the method is solely used to capture the “message” of a text or speech; it is not used for the analysis of a recipient’s response to or understanding of the message (which is normally accessed via interview data and analyzed in other and often less rigorous ways; see, e.g., Merton, 1968 ). So, in this chapter I suggest that we can take things at least one small step further by using CTA to analyze speech (especially interview data) as well as text.

Standard textbook discussions of CTA usually refer to it as a “nonreactive” or “unobtrusive” method of investigation (see, e.g., Babbie, 2013 , p. 294), and a large part of the reason for that designation is because of its focus on already existing text (i.e., text gathered without intrusion into a research setting). More important, however (and to underline the obvious), CTA is primarily a method of analysis rather than of data collection. Its use, therefore, must be integrated into wider frames of research design that embrace systematic forms of data collection as well as forms of data analysis. Thus, routine strategies for sampling data are often required in designs that call on CTA as a method of analysis. These latter can be built around random sampling methods or even techniques of “theoretical sampling” (Glaser & Strauss, 1967 ) so as to identify a suitable range of materials for CTA. Content analysis can also be linked to styles of ethnographic inquiry and to the use of various purposive or nonrandom sampling techniques. For an example, see Altheide ( 1987 ).

The use of CTA in a research design does not preclude the use of other forms of analysis in the same study, because it is a technique that can be deployed in parallel with other methods or with other methods sequentially. For example, and as I will demonstrate in the following sections, one might use CTA as a preliminary analytical strategy to get a grip on the available data before moving into specific forms of discourse analysis. In this respect, it can be as well to think of using CTA in, say, the frame of a priority/sequence model of research design as described by Morgan ( 1998 ).

As I shall explain, there is a sense in which CTA rests at the base of all forms of qualitative data analysis, yet the paradox is that the analysis of content is usually considered a quantitative (numerically based) method. In terms of the qualitative/quantitative divide, however, it is probably best to think of CTA as a hybrid method, and some writers have in the past argued that it is necessarily so (Kracauer, 1952 ). That was probably easier to do in an age when many recognized the strictly drawn boundaries between qualitative and quantitative styles of research to be inappropriate. Thus, in their widely used text Methods in Social Research , Goode and Hatt ( 1952 ), for example, asserted that “modern research must reject as a false dichotomy the separation between ‘qualitative’ and ‘quantitative’ studies, or between the ‘statistical’ and the ‘non-statistical’ approach” (p. 313). This position was advanced on the grounds that all good research must meet adequate standards of validity and reliability, whatever its style, and the message is well worth preserving. However, there is a more fundamental reason why it is nonsensical to draw a division between the qualitative and the quantitative. It is simply this: All acts of social observation depend on the deployment of qualitative categories—whether gender, class, race, or even age; there is no descriptive category in use in the social sciences that connects to a world of “natural kinds.” In short, all categories are made, and therefore when we seek to count “things” in the world, we are dependent on the existence of socially constructed divisions. How the categories take the shape that they do—how definitions are arrived at, how inclusion and exclusion criteria are decided on, and how taxonomic principles are deployed—constitute interesting research questions in themselves. From our starting point, however, we need only note that “sorting things out” (to use a phrase from Bowker & Star, 1999 ) and acts of “counting”—whether it be of chromosomes or people (Martin & Lynch, 2009 )—are activities that connect to the social world of organized interaction rather than to unsullied observation of the external world.

Some writers deny the strict division between the qualitative and quantitative on grounds of empirical practice rather than of ontological reasoning. For example, Bryman ( 2008 ) argued that qualitative researchers also call on quantitative thinking, but tend to use somewhat vague, imprecise terms rather than numbers and percentages—referring to frequencies via the use of phrases such as “more than” and “less than.” Kracauer ( 1952 ) advanced various arguments against the view that CTA was strictly a quantitative method, suggesting that very often we wished to assess content as being negative or positive with respect to some political, social, or economic thesis and that such evaluations could never be merely statistical. He further argued that we often wished to study “underlying” messages or latent content of documentation and that, in consequence, we needed to interpret content as well as count items of content. Morgan ( 1993 ) argued that, given the emphasis that is placed on “coding” in almost all forms of qualitative data analysis, the deployment of counting techniques is essential and we ought therefore to think in terms of what he calls qualitative as well as quantitative content analysis. Naturally, some of these positions create more problems than they seemingly solve (as is the case with considerations of “latent content”), but given the 21st-century predilection for mixed methods research (Creswell, 2007 ), it is clear that CTA has a role to play in integrating quantitative and qualitative modes of analysis in a systematic rather than merely ad hoc and piecemeal fashion. In the sections that follow, I will provide some examples of the ways in which “qualitative” analysis can be combined with systematic modes of counting. First, however, we must focus on what is analyzed in CTA.

Units of Analysis

So, what is the unit of analysis in CTA? A brief answer is that analysis can be focused on words, sentences, grammatical structures, tenses, clauses, ratios (of, say, nouns to verbs), or even “themes.” Berelson ( 1952 ) gave examples of all of the above and also recommended a form of thematic analysis (cf., Braun & Clarke, 2006 ) as a viable option. Other possibilities include counting column length (of speeches and newspaper articles), amounts of (advertising) space, or frequency of images. For our purposes, however, it might be useful to consider a specific (and somewhat traditional) example. Here it is. It is an extract from what has turned out to be one of the most important political speeches of the current century.

Iraq continues to flaunt its hostility toward America and to support terror. The Iraqi regime has plotted to develop anthrax and nerve gas and nuclear weapons for over a decade. This is a regime that has already used poison gas to murder thousands of its own citizens, leaving the bodies of mothers huddled over their dead children. This is a regime that agreed to international inspections then kicked out the inspectors. This is a regime that has something to hide from the civilized world. States like these, and their terrorist allies, constitute an axis of evil, arming to threaten the peace of the world. By seeking weapons of mass destruction, these regimes pose a grave and growing danger. They could provide these arms to terrorists, giving them the means to match their hatred. They could attack our allies or attempt to blackmail the United States. In any of these cases, the price of indifference would be catastrophic. (George W. Bush, State of the Union address, January 29, 2002)

A number of possibilities arise for analyzing the content of a speech such as the one above. Clearly, words and sentences must play a part in any such analysis, but in addition to words, there are structural features of the speech that could also figure. For example, the extract takes the form of a simple narrative—pointing to a past, a present, and an ominous future (catastrophe)—and could therefore be analyzed as such. There are, in addition, several interesting oppositions in the speech (such as those between “regimes” and the “civilized” world), as well as a set of interconnected present participles such as “plotting,” “hiding,” “arming,” and “threatening” that are associated both with Iraq and with other states that “constitute an axis of evil.” Evidently, simple word counts would fail to capture the intricacies of a speech of this kind. Indeed, our example serves another purpose—to highlight the difficulty that often arises in dissociating CTA from discourse analysis (of which narrative analysis and the analysis of rhetoric and trope are subspecies). So how might we deal with these problems?

One approach that can be adopted is to focus on what is referenced in text and speech, that is, to concentrate on the characters or elements that are recruited into the text and to examine the ways in which they are connected or co-associated. I shall provide some examples of this form of analysis shortly. Let us merely note for the time being that in the previous example we have a speech in which various “characters”—including weapons in general, specific weapons (such as nerve gas), threats, plots, hatred, evil, and mass destruction—play a role. Be aware that we need not be concerned with the veracity of what is being said—whether it is true or false—but simply with what is in the speech and how what is in there is associated. (We may leave the task of assessing truth and falsity to the jurists). Be equally aware that it is a text that is before us and not an insight into the ex-president’s mind, or his thinking, or his beliefs, or any other subjective property that he may have possessed.

In the introductory paragraph, I made brief reference to some ideas of the German philosopher Jürgen Habermas ( 1987 ). It is not my intention here to expand on the detailed twists and turns of his claims with respect to the role of language in the “lifeworld” at this point. However, I do intend to borrow what I regard as some particularly useful ideas from his work. The first is his claim—influenced by a strong line of 20th-century philosophical thinking—that language and culture are constitutive of the lifeworld (Habermas, 1987 , p. 125), and in that sense we might say that things (including individuals and societies) are made in language. That is a simple justification for focusing on what people say rather than what they “think” or “believe” or “feel” or “mean” (all of which have been suggested at one time or another as points of focus for social inquiry and especially qualitative forms of inquiry). Second, Habermas argued that speakers and therefore hearers (and, one might add, writers and therefore readers), in what he calls their speech acts, necessarily adopt a pragmatic relation to one of three worlds: entities in the objective world, things in the social world, and elements of a subjective world. In practice, Habermas ( 1987 , p. 120) suggested all three worlds are implicated in any speech act, but that there will be a predominant orientation to one of them. To rephrase this in a crude form, when speakers engage in communication, they refer to things and facts and observations relating to external nature, to aspects of interpersonal relations, and to aspects of private inner subjective worlds (thoughts, feelings, beliefs, etc.). One of the problems with locating CTA in “communication research” has been that the communications referred to are but a special and limited form of action (often what Habermas called strategic acts). In other words, television, newspaper, video, and Internet communications are just particular forms (with particular features) of action in general. Again, we might note in passing that the adoption of the Habermassian perspective on speech acts implies that much of qualitative analysis in particular has tended to focus only on one dimension of communicative action—the subjective and private. In this respect, I would argue that it is much better to look at speeches such as George W Bush’s 2002 State of the Union address as an “account” and to examine what has been recruited into the account, and how what has been recruited is connected or co-associated, rather than use the data to form insights into his (or his adviser’s) thoughts, feelings, and beliefs.

In the sections that follow, and with an emphasis on the ideas that I have just expounded, I intend to demonstrate how CTA can be deployed to advantage in almost all forms of inquiry that call on either interview (or speech-based) data or textual data. In my first example, I will show how CTA can be used to analyze a group of interviews. In the second example, I will show how it can be used to analyze a group of policy documents. In the third, I shall focus on a single interview (a “case”), and in the fourth and final example, I will show how CTA can be used to track the biography of a concept. In each instance, I shall briefly introduce the context of the “problem” on which the research was based, outline the methods of data collection, discuss how the data were analyzed and presented, and underline the ways in which CTA has sharpened the analytical strategy.

Analyzing a Sample of Interviews: Looking at Concepts and Their Co-associations in a Semantic Network

My first example of using CTA is based on a research study that was initially undertaken in the early 2000s. It was a project aimed at understanding why older people might reject the offer to be immunized against influenza (at no cost to them). The ultimate objective was to improve rates of immunization in the study area. The first phase of the research was based on interviews with 54 older people in South Wales. The sample included people who had never been immunized, some who had refused immunization, and some who had accepted immunization. Within each category, respondents were randomly selected from primary care physician patient lists, and the data were initially analyzed “thematically” and published accordingly (Evans, Prout, Prior, Tapper-Jones, & Butler, 2007 ). A few years later, however, I returned to the same data set to look at a different question—how (older) lay people talked about colds and flu, especially how they distinguished between the two illnesses and how they understood the causes of the two illnesses (see Prior, Evans, & Prout, 2011 ). Fortunately, in the original interview schedule, we had asked people about how they saw the “differences between cold and flu” and what caused flu, so it was possible to reanalyze the data with such questions in mind. In that frame, the example that follows demonstrates not only how CTA might be used on interview data, but also how it might be used to undertake a secondary analysis of a preexisting data set (Bryman, 2008 ).

As with all talk about illness, talk about colds and flu is routinely set within a mesh of concerns—about causes, symptoms, and consequences. Such talk comprises the base elements of what has at times been referred to as the “explanatory model” of an illness (Kleinman, Eisenberg, & Good, 1978 ). In what follows, I shall focus almost entirely on issues of causation as understood from the viewpoint of older people; the analysis is based on the answers that respondents made in response to the question, “How do you think people catch flu?”

Semistructured interviews of the kind undertaken for a study such as this are widely used and are often characterized as akin to “a conversation with a purpose” (Kahn & Cannell, 1957 , p. 97). One of the problems of analyzing the consequent data is that, although the interviewer holds to a planned schedule, the respondents often reflect in a somewhat unstructured way about the topic of investigation, so it is not always easy to unravel the web of talk about, say, “causes” that occurs in the interview data. In this example, causal agents of flu, inhibiting agents, and means of transmission were often conflated by the respondents. Nevertheless, in their talk people did answer the questions that were posed, and in the study referred to here, that talk made reference to things such as “bugs” (and “germs”) as well as viruses, but the most commonly referred to causes were “the air” and the “atmosphere.” The interview data also pointed toward means of transmission as “cause”—so coughs and sneezes and mixing in crowds figured in the causal mix. Most interesting, perhaps, was the fact that lay people made a nascent distinction between facilitating factors (such as bugs and viruses) and inhibiting factors (such as being resistant, immune, or healthy), so that in the presence of the latter, the former are seen to have very little effect. Here are some shorter examples of typical question–response pairs from the original interview data.

(R:32): “How do you catch it [the flu]? Well, I take it its through ingesting and inhaling bugs from the atmosphere. Not from sort of contact or touching things. Sort of airborne bugs. Is that right?” (R:3): “I suppose it’s [the cause of flu] in the air. I think I get more diseases going to the surgery than if I stayed home. Sometimes the waiting room is packed and you’ve got little kids coughing and spluttering and people sneezing, and air conditioning I think is a killer by and large I think air conditioning in lots of these offices.” (R:46): “I think you catch flu from other people. You know in enclosed environments in air conditioning which in my opinion is the biggest cause of transferring diseases is air conditioning. Worse thing that was ever invented that was. I think so, you know. It happens on aircraft exactly the same you know.”

Alternatively, it was clear that for some people being cold, wet, or damp could also serve as a direct cause of flu; thus: Interviewer: “OK, good. How do you think you catch the flu?”

(R:39): “Ah. The 65 dollar question. Well, I would catch it if I was out in the rain and I got soaked through. Then I would get the flu. I mean my neighbour up here was soaked through and he got pneumonia and he died. He was younger than me: well, 70. And he stayed in his wet clothes and that’s fatal. Got pneumonia and died, but like I said, if I get wet, especially if I get my head wet, then I can get a nasty head cold and it could develop into flu later.”

As I suggested earlier, despite the presence of bugs and germs, viruses, the air, and wetness or dampness, “catching” the flu is not a matter of simple exposure to causative agents. Thus, some people hypothesized that within each person there is a measure of immunity or resistance or healthiness that comes into play and that is capable of counteracting the effects of external agents. For example, being “hardened” to germs and harsh weather can prevent a person getting colds and flu. Being “healthy” can itself negate the effects of any causative agents, and healthiness is often linked to aspects of “good” nutrition and diet and not smoking cigarettes. These mitigating and inhibiting factors can either mollify the effects of infection or prevent a person “catching” the flu entirely. Thus, (R:45) argued that it was almost impossible for him to catch flu or cold “cos I got all this resistance.” Interestingly, respondents often used possessive pronouns in their discussion of immunity and resistance (“my immunity” and “my resistance”)—and tended to view them as personal assets (or capital) that might be compromised by mixing with crowds.

By implication, having a weak immune system can heighten the risk of contracting colds and flu and might therefore spur one to take preventive measures, such as accepting a flu shot. Some people believe that the flu shot can cause the flu and other illnesses. An example of what might be called lay “epidemiology” (Davison, Davey-Smith, & Frankel, 1991 ) is evident in the following extract.

(R:4): “Well, now it’s coincidental you know that [my brother] died after the jab, but another friend of mine, about 8 years ago, the same happened to her. She had the jab and about six months later, she died, so I know they’re both coincidental, but to me there’s a pattern.”

Normally, results from studies such as this are presented in exactly the same way as has just been set out. Thus, the researcher highlights given themes that are said to have emerged from the data and then provides appropriate extracts from the interviews to illustrate and substantiate the relevant themes. However, one reasonable question that any critic might ask about the selected data extracts concerns the extent to which they are “representative” of the material in the data set as a whole. Maybe, for example, the author has been unduly selective in his or her use of both themes and quotations. Perhaps, as a consequence, the author has ignored or left out talk that does not fit the arguments or extracts that might be considered dull and uninteresting compared to more exotic material. And these kinds of issues and problems are certainly common to the reporting of almost all forms of qualitative research. However, the adoption of CTA techniques can help to mollify such problems. This is so because, by using CTA, we can indicate the extent to which we have used all or just some of the data, and we can provide a view of the content of the entire sample of interviews rather than just the content and flavor of merely one or two interviews. In this light, we must consider Figure 19.1 , which is based on counting the number of references in the 54 interviews to the various “causes” of the flu, though references to the flu shot (i.e., inoculation) as a cause of flu have been ignored for the purpose of this discussion. The node sizes reflect the relative importance of each cause as determined by the concept count (frequency of occurrence). The links between nodes reflect the degree to which causes are co-associated in interview talk and are calculated according to a co-occurrence index (see, e.g., SPSS, 2007 , p. 183).

What causes flu? A lay perspective. Factors listed as causes of colds and flu in 54 interviews. Node size is proportional to number of references “as causes.” Line thickness is proportional to co-occurrence of any two “causes” in the set of interviews.

Given this representation, we can immediately assess the relative importance of the different causes as referred to in the interview data. Thus, we can see that such things as (poor) “hygiene” and “foreigners” were mentioned as a potential cause of flu—but mention of hygiene and foreigners was nowhere near as important as references to “the air” or to “crowds” or to “coughs and sneezes.” In addition, we can also determine the strength of the connections that interviewees made between one cause and another. Thus, there are relatively strong links between “resistance” and “coughs and sneezes,” for example.